1. Introduction

The human microbiome, comprising trillions of microorganisms distributed across various body sites, plays a crucial role in development, immune regulation, and maintaining physiological balance. The gut hosts the most abundant and diverse microbial population, which is shaped by diet, lifestyle, and environment [

1,

2]. Dysbiosis, marked by reduced microbial richness and diversity, can impair systemic homeostasis and has been linked to diseases affecting distant organs, including the eyes [

1,

2]. The concept of a “gut–eye axis” has emerged, implicating gut microbial imbalances in ocular inflammatory and autoimmune disorders, such as Sjögren’s disease (SjD), dry eye disease (DED), uveitis, and diabetic retinopathy [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and SjD are systemic autoimmune diseases with severe ocular manifestations, including persistent dry eye, that are often refractory to conventional therapies. SJS is a rare condition, with an annual prevalence of 1.2 to 6 cases per million, characterized by acute mucocutaneous inflammation and chronic cicatricial sequelae, which lead to irreversible damage to the ocular surface and eyelids, severely impairing vision [

7,

8]. Genetic and immune-mediated mechanisms, particularly T cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reactions and activation of Toll-like receptor 3, play a critical role in the recurrent mucocutaneous inflammation and severe ocular complications observed in SJS [

8,

9]. SjD, in contrast, primarily affects exocrine glands, contributing to dryness of the eyes and mouth, as well as systemic inflammatory manifestations. It is more prevalent, affecting 100 to 900 per million annually, with a strong female predominance [

10,

11,

12]. Both diseases share clinical features, including severe dry eye, chronic conjunctival inflammation, and reduced salivary flow [

7,

10].

DED, common in both conditions, is characterized by tear film instability, hyperosmolarity, inflammation, and neurosensory abnormalities, creating a self-perpetuating inflammatory cycle [

13,

14]. Recent studies suggest that gut microbiota modulate T-cell responses and contribute to ocular surface homeostasis. Animal and human models have demonstrated that alterations in the gut microbiota can exacerbate dry eye severity via immune dysregulation [

15,

16,

17].

While gut microbiome alterations have been explored in SjD [

15,

18,

19], and ocular surface dysbiosis has been reported in SJS [

20,

21,

22], no study has examined the intestinal microbiome in SJS to date. This study is the first to characterize gut microbiome in SJS patients and compare it with those of individuals with SjD and healthy controls while also assessing correlations with dry eye severity. We hypothesize that SJS is associated with intestinal dysbiosis, which may contribute to ocular surface inflammation and the clinical severity of dry eye disease.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

This prospective case-control study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (approval number: 6.003.698) and conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent before participation.

A total of 32 participants were recruited from the Corneal and External Diseases Clinic at the Federal University of São Paulo between March 2023 and February 2024. Ten patients with chronic SJS, ten with primary SjD, and twelve with healthy controls were included. Participants were aged eighteen years or older, had no other ocular diseases (other than those related to SJS or dry eye), and had no history of gastrointestinal disorders. Exclusion criteria included trauma, infection, or surgery in the last three months, as well as antibiotic, probiotic, or prebiotic use during that period.

The SJS group included patients with chronic disease following a history of mucocutaneous inflammation induced by medications or infections, involving at least two mucous membranes. The classification into mild, moderate, and severe ocular involvement was based on the presence and extent of ocular surface sequelae, following the simplified criteria proposed initially by Sotozono et al. [

23] and later adopted by Kittipibul et al. [

21] (

Table 1). These included eyelash abnormalities, lid margin keratinization, conjunctival inflammation, conjunctival fibrosis, limbal stem cell deficiency, corneal epitheliopathy and corneal opacity. Patients presenting fewer or milder findings were classified as mild, those with moderate structural involvement as moderate, and those with multiple and severe complications as severe. One patient from this group was excluded from microbiome analyses after discovering a pregnancy following sample collection and completion of microbiome analysis.

The SjD group consisted of patients with confirmed primary SjD, diagnosed according to the American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism criteria [

24] with no associated autoimmune comorbidities. All SjD patients reported systemic involvement, dry eye and mouth symptoms, and were under oral hydroxychloroquine treatment. The SJS and SjD patient groups differed in age and sex distribution. Therefore, a distinct healthy control group was established for each disease cohort. Ten healthy control subjects were age- and sex-matched to the SJS group, and another set of ten controls was matched to the SjD group. Eight control subjects overlapped between the two disease groups, while two additional individuals were included to achieve optimal demographic matching. All statistical comparisons were conducted between each disease group and its corresponding control group.

Healthy control subjects had no eye irritation, a tear break-up time (TBUT) ≥ 7 s, Schirmer I ≥ 10 mm, corneal fluorescein score ≤2, conjunctival lissamine score ≤ 2, and no meibomian gland disease. Subjects were excluded if they had prior laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis or corneal transplantation surgery, cataract surgery in the past year, punctual occlusion with plugs or cautery, a history of contact lens wear, use of topical medications other than preservative-free artificial tears, or chronic use of systemic medications known to reduce tear production.

2.2. Clinical Assessment

All participants underwent a comprehensive ophthalmologic evaluation performed by the same examiner (LF). Ocular disease involvement was assessed according to the guidelines established by the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS) [

25]. The examination was conducted in a standardized sequence: initially, the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire was administered, followed by the Schirmer I test, tear break-up time (TBUT), and finally, corneal fluorescein and conjunctival lissamine green staining, graded according to the National Eye Institute (NEI) scoring system. Dry eye severity was classified using the DED DEWS system [

25] which ranges from 0 to 4 and is based on the cumulative assessment of clinical parameters, including OSDI, Schirmer I test, TBUT, NEI score, and subjective symptoms. Accordingly, more advanced stages of dry eye are characterized by higher DED DEWS, OSDI, and NEI scores and lower TBUT and Schirmer I values. All SJS and SjD patients had a Dry eye disease score of DED DEWS score ≥ 3, and healthy control groups had a score = 0.

The Schirmer I test assessed basal and reflex tear secretion over a five-minute period without the use of anesthetic eye drops [

26]. TBUT was measured three times in each eye using fluorescein strips, and the average was recorded. Corneal fluorescein staining was scored across five regions (0–3 per region), with a maximum score of 15. Conjunctival staining with lissamine green was assessed over six areas, with scores from 0 to 18. The NEI score was the sum of both corneal and conjunctival staining [

27].

2.3. Sample Collection

All participants received standardized stool microbiome collection kits with detailed instructions for at-home sampling. They were advised to collect the fecal sample within 48 hours before the clinical visit, store it at ambient temperature, and return it on the day of the clinical examination. All samples were collected using standardized fecal microbiome collection kits (DNA/RNA ShieldTM Zymo Research Corp, Irvine, California, USA), which contain a preservation medium capable of maintaining microbial integrity at ambient temperature for up to 30 days. After clinical examination, samples were stored at ambient temperature and shipped to the laboratory (Inside Diagnósticos, São Paulo, SP, Brazil) within 48 hours. Upon arrival, all samples were processed for sequencing within 2 days.

2.4. Fecal Microbiome Analysis

DNA extraction was performed using the ZymoBIOMICS™ DNA Kit (Zymo Research Corp., Irvine, CA, USA), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Amplicon sequencing of the 16S rRNA V3–V4 region was subsequently carried out using the QIAseq 16S/ITS Screening Panel (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers 515F (5’-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3’) and 806R (5’-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3’) were employed for amplification. Sequencing was carried out on the Illumina MiSeq platform using the MiSeq v2 kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Raw sequencing reads were processed using QIIME 2 version 2024.5 (

https://qiime2.org) [

28] Default parameters were applied for trimming and joining paired-end reads. The DADA2 plugin was used to denoise reads and generate amplicon sequence variants (ASVs), which were subsequently clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 99% similarity using the VSEARCH plugin. Taxonomic assignment was performed based on the SILVA database (release 138.2), with taxonomic filtering to exclude mitochondria, chloroplasts, and Eukaryotic taxa [

29].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 20.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) for general statistical tests and RStudio (version 4.3.1) for microbiome-specific analyses. Mean comparisons between the two groups were evaluated using the Student’s t-test, Fisher’s exact test, and the Mann-Whitney test. Comparison among more than two groups, analysis of Variance (ANOVA), and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used. Spearman’s correlation was applied to assess linear associations between variables due to non-normal distributions. In the genus-level analysis, only genera with an average relative abundance of at least 1% were included. Statistical significance was set at p = 0.05.

Microbiome data analysis and visualization were performed using the phyloseq, vegan, ggplot2, and microbiome packages in RStudio. The alpha diversity, Chao1, and Shannon indices were calculated, and statistical significance was assessed using the Mann-Whitney test with Dunn’s adjustment for multiple comparisons. Beta diversity was computed using both unweighted and weighted UniFrac distances and visualized through Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) plots. Statistical significance for beta diversity was determined using permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with the adonis and pairwise functions.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Data

Age and sex distribution showed no significant differences between the SJS group and the respective healthy control group and between the SjD group and the respective healthy control group (

Table 2). The clinical examination and dry eye parameters of the SJS group and its control group, as well as the SjD group and its control group, are described in

Table 3. Patients with SJS and SjD exhibited significantly worse clinical indicators, including higher OSDI and NEI scores and lower Schirmer I test and TBUT values, compared to their respective healthy controls. The composite DED DEWS score, which integrates all these parameters, was also markedly higher in both disease groups (3-4), reflecting greater ocular surface involvement. All comparisons between the disease group and its control group showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.005) in dry eye parameters (

Table 3).

3.2. Intestinal Microbiome Measures

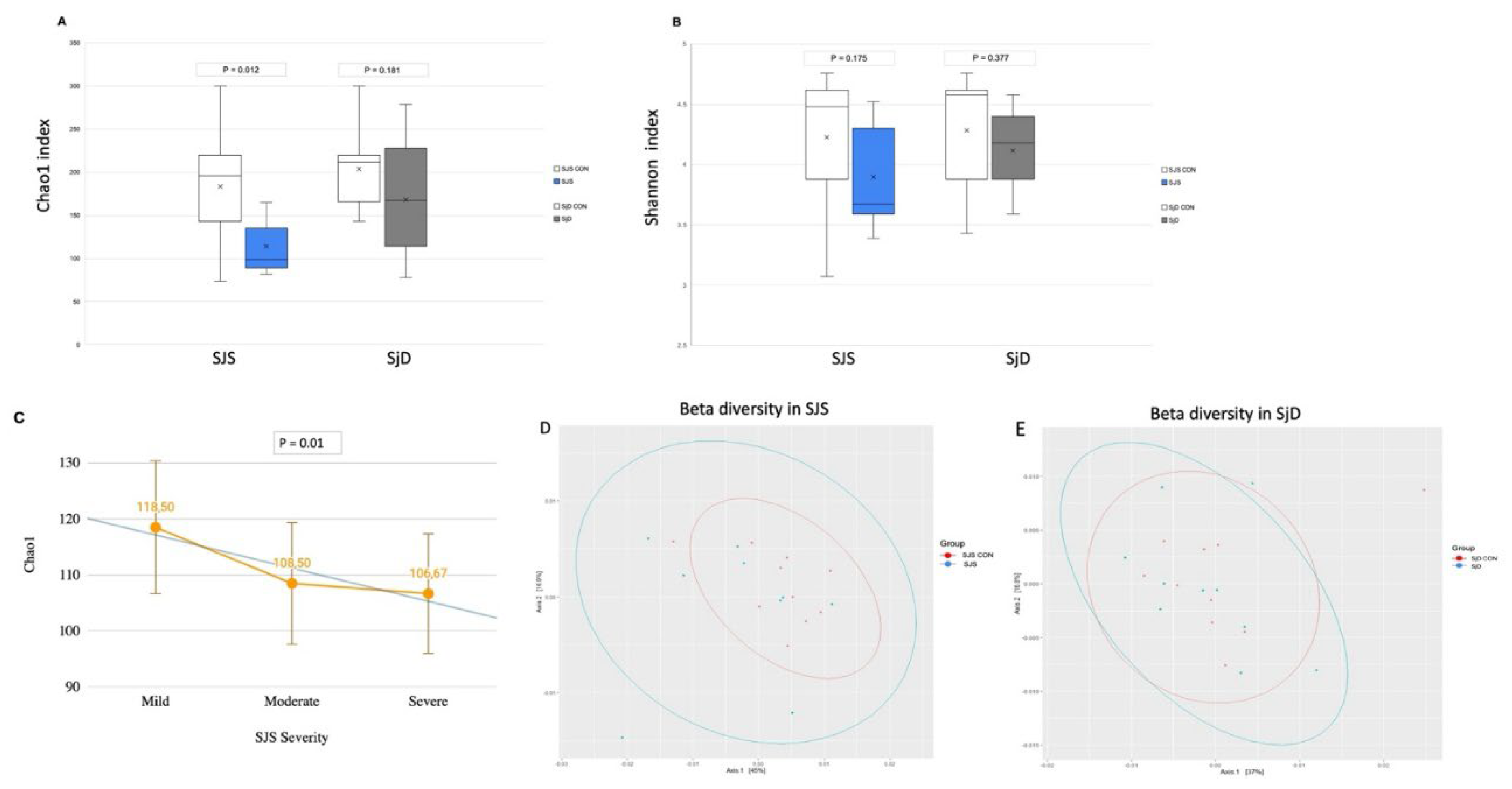

Concerning alpha diversity, the Chao1 index, which represents species richness, was significantly lower in the SJS group compared to the respective healthy control group (p = 0.012) and demonstrated a progressive decline correlating with increased ocular surface severity (p = 0.01) (

Figure 1A,C). In contrast, the Shannon diversity index, did not show a significant difference between groups (p = 0.175) (

Figure 1B). On the other hand, alpha diversity comparisons between the SjD group and the respective healthy control group indicated numerical differences in Chao 1 and Shannon diversity index, however, not statistically significant (p = 0.181 and p = 0.377, respectively) (

Figure 1 A,B). Beta diversity analysis using weighted and unweighted UniFrac distances revealed no significant differences between the SJS group and its respective healthy control group (p = 0.192) and between the SjD group and its respective healthy control group (p = 0.757) (

Figure 1D,E).

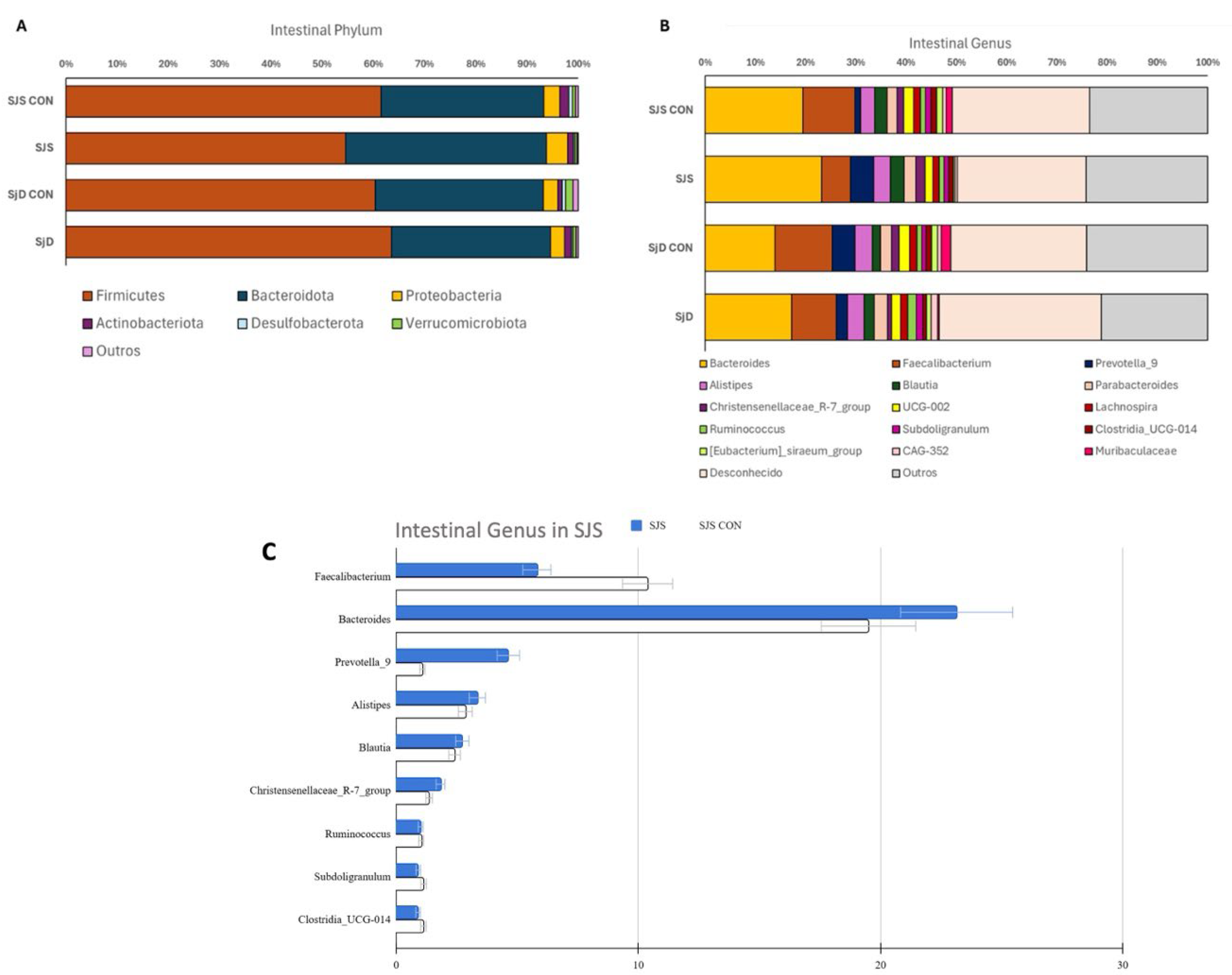

Table 4 describes the phylum and genus abundance of the SJS group and the respective healthy control group, and

Figure 2 illustrates the phylum and genus abundance of both SJS and SjD and their respective healthy control groups. Among phyla, no statistically significant differences were observed between SJS and SjD when compared to their respective healthy control groups (

Figure 2A). Regarding genus,

Faecalibacterium was significantly less abundant in the SJS group compared to the respective healthy control group (p = 0.048) (

Figure 2B,2C,

Table 4). No significant differences in genus levels were found between the SjD group and the respective healthy control group (

Figure 2B). Raw sequencing data and OTU tables have been deposited in the NCBI public repository and can be accessed at:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/1280506.

3.3. Dry Eye Correlations

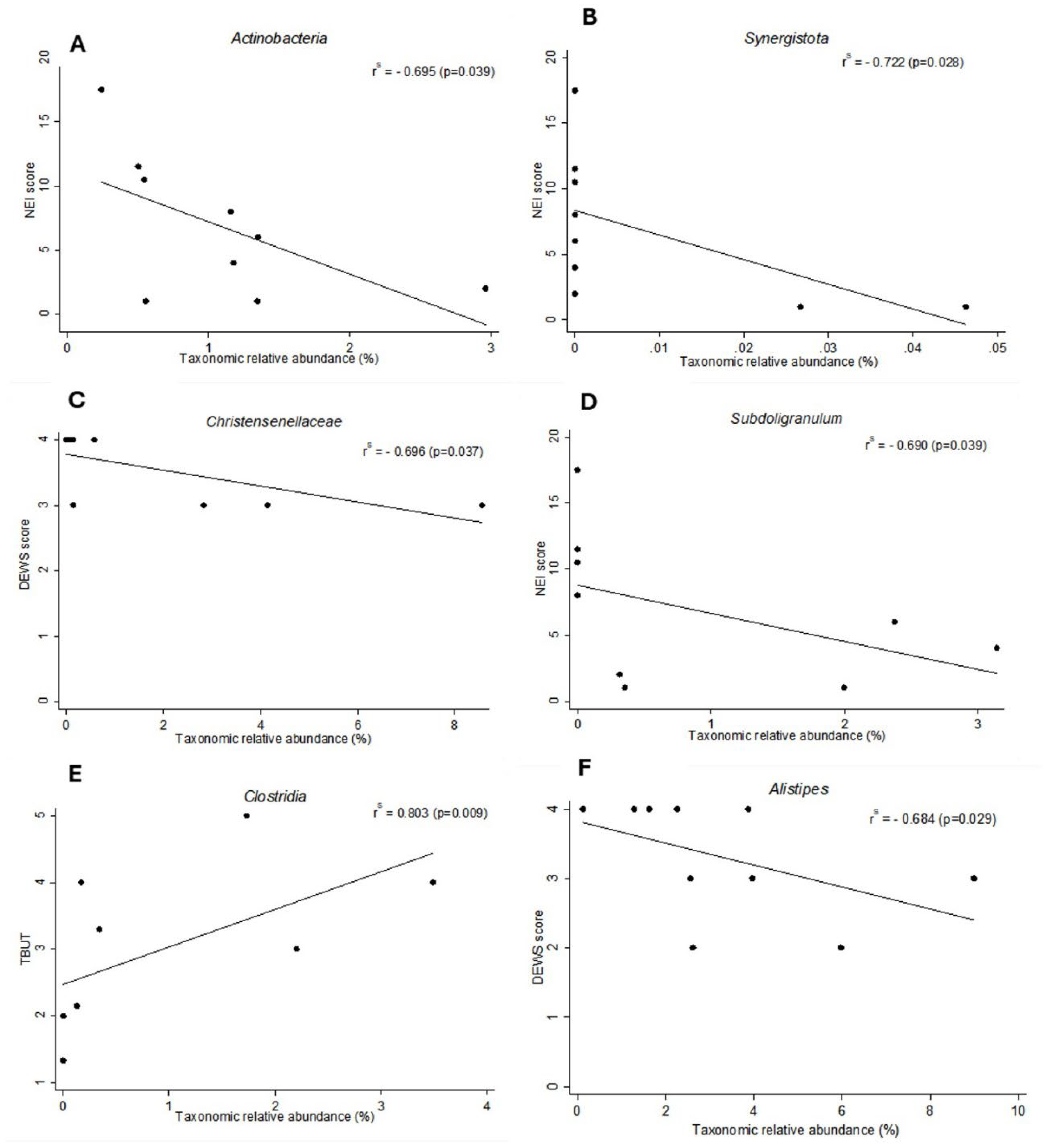

Comparing Phyla data with dry eye indices in the SJS group, Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed significant negative correlations between the NEI Score and Actinobacteria (r = -0.695, p = 0.039,) as well as Synergistota (r = -0.722, p = 0.028,) (

Figure 3A,B). These findings suggest that higher abundances of Actinobacteria and Synergistota were associated with less severe dry eye signs, such as reduced corneal and conjunctival staining in the SJS group. In the SjD group, no statistically significant correlations were observed at the phylum level and dry eye indices.

In correlations between bacterial genera and dry eye indices in the SJS group, Spearman’s correlation revealed a moderate negative correlation between

Christensenellaceae abundance and the DED DEWS Score (r = -0.696, p = 0.037), as well as between

Subdoligranulum abundance and the NEI Score (r = -0.690, p = 0.039) (

Figure 3C,D). A positive correlation was also observed between

Clostridia abundance and TBUT (r = 0.803, p = 0.009) (

Figure 3E). These results indicate that higher abundances of

Christensenellaceae,

Subdoligranulum, and

Clostridia are associated with less severe dry eye parameters in the SJS group. In the SjD group, a moderate negative correlation was found between

Alistipes abundance and the DED DEWS Score (r = -0.684, p = 0.029), suggesting that a higher abundance of

Alistipes was associated with less severe dry eye disease (

Figure 3F).

Regarding the ocular SJS group severity (mild, moderate, and severe ocular severity grades), Spearman’s correlation analysis revealed a moderate positive correlation between disease severity and the abundance of Cyanobacteria (p = 0.050, r = 0.659) and Fusobacteria (p = 0.050, r = 0.659) at the phylum level. No statistically significant correlations were observed at the genus level.

Taken together, SJS patients exhibited reduced gut microbial richness, as indicated by a lower Chao1 index and decreased abundance of Faecalibacterium, with specific bacterial taxa correlating with increased dry eye severity.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that patients with SJS exhibit significantly reduced gut microbial richness, including marked depletion of Faecalibacterium, compared to healthy controls. Moreover, distinct alterations in microbial composition were associated with more severe dry eye parameters. To our knowledge, this is the first investigation to characterize the gut microbiome in SJS while simultaneously comparing it with patients diagnosed with primary SjD and healthy individuals.

Alpha diversity, particularly the Chao1 index, was significantly decreased in SJS patients and showed a progressive decline correlating with the severity of ocular surface inflammation. These results are consistent with prior findings in mucous membrane pemphigoid [

30] a mucosal autoimmune disease that shares clinical features with SJS, including cicatrizing conjunctivitis and T-cell-mediated inflammation. Similar patterns of reduced alpha diversity have been documented in uveitis [

31], Behçet’s disease [

32] , Sjögren’s disease [

15,

33,

34] and diabetic retinopathy [

35], reinforcing the hypothesis that gut dysbiosis may play a role in immune-driven ocular pathology via systemic pathways. Reduced microbial diversity is commonly associated with increased systemic inflammation and compromised intestinal barrier function, promoting the expansion of pathogenic taxa and chronic immune activation. [

12,

15].

A prominent finding in our cohort of SJS patients was the depletion of

Faecalibacterium, a key butyrate-producing genus with well-documented anti-inflammatory properties [

6] . This is consistent with reductions reported in uveitis [

31] SjD [

15,

19], Behçet's disease [

32], and mucous membrane pemphigoid [

30].

Faecalibacterium contributes to intestinal homeostasis by supporting epithelial barrier integrity, inducing tolerogenic dendritic cells and FOXP3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs), and regulating cytokine profiles. Its primary metabolite, butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced via microbial fermentation of dietary fiber, plays an essential immunomodulatory role [

6] Schaefer et al.[

16,

36] demonstrated that intestinal commensals, such as

Faecalibacterium, can promote ocular immune tolerance by inducing Tregs in draining lymph nodes.

Consistent with clinical expectations, SJS patients exhibited worse dry eye outcomes, with DED DEWS scores ranging from 3 to 4 and microbial diversity inversely associated with ocular surface damage. Correlations between microbiome composition and specific dry eye parameters have previously been identified in SjD [

15,

18]. Our study further correlated microbial composition at the phylum and genus levels with specific dry eye parameters. At the phylum level, an increased abundance of

Actinobacteria and

Synergistota was associated with lower NEI scores, reflecting less ocular surface damage. Moon et al. [

18] reported similar findings, linking

Actinobacteria with improved TBUT and reduced dry eye severity, and Wang et al. [

37] found an association between

Actinobacteria and reduced dry eye severity.

At the genus level,

Subdoligranulum abundance was negatively correlated with NEI scores, consistent with reports by Cao et al. [

38] and Moon et al. [

18]

, where this genus was depleted in both SjD and non-Sjögren dry eye groups. We also observed an increased abundance of

Christensenellaceae correlated with lower DED DEWS scores, and

Clostridia was positively associated with TBUT, suggesting a potential protective role of these taxa on the ocular surface.

In our study, alpha and beta diversity in SjD group did not differ significantly from those of healthy controls, in agreement with findings reported by Mendez et al. [

19], Moon et al. [

18], and Zhang et al. [

39], but in contrast to the decreased microbial diversity described by Schaefer et al. [

17], de Paiva et al. [

15], and Cano-Ortiz et al. [

34]. Similarly, microbial composition at both the phylum and genus levels showed no statistically significant differences in our cohort. However, a recent study by Jia et al. [

40] using shotgun metagenomic sequencing in treatment-naïve primary SjD revealed marked compositional and functional aberrations in the gut microbiota, characterized by reduced microbial richness along with enrichment of potentially pro-inflammatory taxa such as

Lactobacillus salivarius,

Bacteroides fragilis,

Ruminococcus gnavus,

Clostridium bartlettii, and

Veillonella parvula.

L. salivarius was identified as the most discriminating species. These inconsistencies may reflect the small sample size, geographic and demographic variability, methodological differences or differences in disease phenotype and disease severity.

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. It is a cross-sectional and observational study with a relatively small cohort, particularly for a rare condition such as SJS, and lacks longitudinal data. The 16S rRNA sequencing used provides genus-level resolution but does not allow for species or functional gene-level analysis [

41]. Future studies using shotgun metagenomics, strain-resolved profiling, and integration of host immune and metabolomic data, including assessment of SCFA synthesis pathways and immunomodulatory gene content, are warranted to enhance mechanistic insights.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our findings indicate that patients with SJS exhibit reduced gut microbial richness, including a marked depletion of anti-inflammatory taxa such as Faecalibacterium. Moreover, specific taxonomic groups were correlated with more severe dry eye parameters. These results provide preliminary evidence supporting the potential role of the gut microbiome in ocular surface inflammation. Although these associations should be interpreted with caution given the cross-sectional design, small sample size, and interindividual variability, this study contributes novel data to the growing body of literature on the role of the microbiome in ocular immunopathology and dry eye in SJS. These findings underscore the need for larger, longitudinal investigations incorporating functional metagenomics and immunological profiling to confirm these associations and explore microbiome-based therapeutic strategies in SJS-associated dry eye disease.

Author Contributions

LF wrote the original draft and made subsequent revisions; TTR contributed to the methodology and writing of the original draft, reviewing and editing the final manuscript; AF contributed to the writing, reviewing, and editing the final manuscript; RJAA contributed to the methodology, reviewing, and editing the final manuscript, CSP contributed to the analysis, reviewing, and editing the final manuscript; JAPG contributed to the design of the study, reviewing, and editing the final manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. CSdP receives salary support from the Caroline Elles Professorship.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study adhered to the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of São Paulo (approval number: 6.003.698). An informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrolment.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects before enrolment.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Humberto Bezerra de Araújo Filho for his valuable contribution to the bioinformatic analyses and scientific discussion.

Conflicts of Interest

Outside any subjects treated in the present work, José Álvaro Pereira Gomes has the following financial interests or relationships to disclose: Alcon Laboratories, Inc.: Consultant/Advisor, Lecture Fees/Speakers Bureau, Grant Support; Allergan Medical Affairs/Abbvie: Consultant/Advisor, Lecture Fees/Speakers Bureau; Bausch + Lomb: Consultant/Advisor, Lecture Fees/Speakers Bureau; CAPES: Grant Support; Celebrim: Consultant/Advisor, Lecture Fees/Speakers Bureau; Cnpq: Grant Support; EMS: Consultant/Advisor; Fapesp: Grant Support; Genon: Lecture Fees/Speakers Bureau; Johnson & Johnson: Consultant/Advisor, Lecture Fees/Speakers Bureau; Latinofarma/Cristália: Consultant/Advisor, Lecture Fees/Speakers Bureau, Grant Support; Mediphacos: Consultant/Advisor; Novartis: Consultant/Advisor; Ofta: Consultant/Advisor, Lecture Fees/Speakers Bureau, Grant Support. Cintia S. de Paiva has the following financial interests or relationships to disclose: HannAll: research grant. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Human Microbiome Project Consortium. A framework for human microbiome research. Nature 2012, 486, 215–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aagaard, K.; Petrosino, J.; Keitel, W.; Watson, M.; Katancik, J.; Garcia, N.; et al. The Human Microbiome Project strategy for comprehensive sampling of the human microbiome and why it matters. FASEB J. 2013, 27, 1012–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zárate-Bladés, C.R.; Horai, R.; Mattapallil, M.J.; Ajami, N.J.; Wong, M.; Petrosino, J.F.; et al. Gut microbiota as a source of a surrogate antigen that triggers autoimmunity in an immune-privileged site. Gut Microbes. 2017, 8, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, C.; Schaefer, L.; Bian, F.; Yu, Z.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; et al. Dysbiosis Modulates Ocular Surface Inflammatory Response to Liposaccharide. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019, 60, 4224–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Campagnoli, L.I.M.; Varesi, A.; Barbieri, A.; Marchesi, N.; Pascale, A. Targeting the Gut-Eye Axis: An Emerging Strategy to Face Ocular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 13338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Trujillo-Vargas, C.M.; Schaefer, L.; Alam, J.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; de Paiva, C.S. The gut-eye-lacrimal gland-microbiome axis in Sjögren Syndrome. Ocul Surf. 2020, 18, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kohanim, S.; Palioura, S.; Saeed, H.N.; Akpek, E.K.; Amescua, G.; Basu, S.; et al. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis--A Comprehensive Review and Guide to Therapy. I. Systemic Disease. Ocul Surf. 2016, 14, 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueta, M. Pathogenesis of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis With Severe Ocular Complications. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021, 8, 651247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ueta, M.; Sotozono, C.; Inatomi, T.; Kojima, K.; Tashiro, K.; Hamuro, J.; et al. Toll-like receptor 3 gene polymorphisms in Japanese patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007, 91, 962–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mariette, X.; Criswell, L.A. Primary Sjögren's Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2018, 378, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Casals, M.; Baer, A.N.; Brito-Zerón, M.d.P.; et al. International Rome consensus for the nomenclature of Sjögren disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2023, 21, 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paiva, C.S.; Pflugfelder, S.C. Mechanisms of Disease in Sjögren Syndrome-New Developments and Directions. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Craig, J.P.; Nichols, K.K.; Akpek, E.K.; Caffery, B.; Dua, H.S.; Joo, C.K.; et al. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf. 2017, 15, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pflugfelder, S.C.; de Paiva, C.S. The Pathophysiology of Dry Eye Disease: What We Know and Future Directions for Research. Ophthalmology. 2017, 124, S4–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Paiva, C.S.; Jones, D.B.; Stern, M.E.; Bian, F.; Moore, Q.L.; Corbiere, S.; et al. Altered Mucosal Microbiome Diversity and Disease Severity in Sjögren Syndrome. Sci Rep. 2016, 6, 23561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zaheer, M.; Wang, C.; Bian, F.; Yu, Z.; Hernandez, H.; de Souza, R.G.; Simmons, K.T.; Schady, D.; Swennes, A.G.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; de Paiva, C.S. Protective role of commensal bacteria in Sjögren Syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2018, 93, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schaefer, L.; Trujillo-Vargas, C.M.; Midani, F.S.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; de Paiva, C.S. Gut Microbiota From Sjögren syndrome Patients Decreased T Regulatory Cells in the Lymphoid Organs and Desiccation-Induced Corneal Barrier Disruption in Mice. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022, 9, 852918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moon, J.; Choi, S.H.; Yoon, C.H.; Kim, M.K. Gut dysbiosis is prevailing in Sjögren's syndrome and is related to dry eye severity. PLoS One. 2020, 15, e0229029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mendez, R.; Watane, A.; Farhangi, M.; Cavuoto, K.M.; Leith, T.; Budree, S.; et al. Gut microbial dysbiosis in individuals with Sjögren's syndrome. Microb Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frizon, L.; Araújo, M.C.; Andrade, L.; Yu, M.C.; Wakamatsu, T.H.; Höfling-Lima, A.L.; Gomes, J.Á. Evaluation of conjunctival bacterial flora in patients with Stevens-Johnson Syndrome. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2014, 69, 168–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kittipibul, T.; Puangsricharern, V.; Chatsuwan, T. Comparison of the ocular microbiome between chronic Stevens-Johnson syndrome patients and healthy subjects. Sci Rep. 2020, 10, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Singh, S.; Maity, M.; Shanbhag, S.; Arunasri, K.; Basu, S. Lid Margin Microbiome in Stevens-Johnson Syndrome Patients With Lid Margin Keratinization and Severe Dry Eye Disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2024, 65, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sotozono, C.; Ang, L.P.; Koizumi, N.; Higashihara, H.; Ueta, M.; Inatomi, T.; et al. New grading system for the evaluation of chronic ocular manifestations in patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2007, 114, 1294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiboski, C.H.; Shiboski, S.C.; Seror, R.; Criswell, L.A.; Labetoulle, M.; Lietman, T.M.; et al. International Sjögren's Syndrome Criteria Working Group. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Classification Criteria for Primary Sjögren's Syndrome: A Consensus and Data-Driven Methodology Involving Three International Patient Cohorts. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017, 69, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007, 5, 75–92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, L.T. The lacrimal secretory system and its treatment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1966, 62, 47–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bron, A.J.; Evans, V.E.; Smith, J.A. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003, 22, 640–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolyen, E.; Rideout, J.R.; Dillon, M.R.; Bokulich, N.A.; Abnet, C.C.; Al-Ghalith, G.A.; et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 852–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Low, L.; Suleiman, K.; Shamdas, M.; Bassilious, K.; Poonit, N.; Rossiter, A.E.; et al. Gut Dysbiosis in Ocular Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022, 12, 780354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kalyana Chakravarthy, S.; Jayasudha, R.; Sai Prashanthi, G.; Ali, M.H.; Sharma, S.; Tyagi, M.; et al. Dysbiosis in the Gut Bacterial Microbiome of Patients with Uveitis, an Inflammatory Disease of the Eye. Indian J Microbiol. 2018, 58, 457–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ye, Z.; Zhang, N.; Wu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Q.; Huang, X.; et al. A metagenomic study of the gut microbiome in Behcet's disease. Microbiome. 2018, 6, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- van der Meulen, T.A.; Harmsen, H.J.M.; Vila, A.V.; Kurilshikov, A.; Liefers, S.C.; Zhernakova, A.; et al. Shared gut, but distinct oral microbiota composition in primary Sjögren's syndrome and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2019, 97, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano-Ortiz, A.; Laborda-Illanes, A.; Plaza-Andrades, I.; Membrillo Del Pozo, A.; Villarrubia Cuadrado, A.; Rodríguez Calvo de Mora, M.; et al. Connection between the Gut Microbiome, Systemic Inflammation, Gut Permeability and FOXP3 Expression in Patients with Primary Sjögren's Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 8733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, H.; Ji, S.; Chen, Z.; Cui, Z.; et al. Dysbiosis and Implication of the Gut Microbiota in Diabetic Retinopathy. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021, 11, 646348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schaefer, L.; Hernandez, H.; Coats, R.A.; Yu, Z.; Pflugfelder, S.C.; Britton, R.A.; de Paiva, C.S. Gut-derived butyrate suppresses ocular surface inflammation. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Y.; Wei, J.; Zhang, W.; Doherty, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xie, H.; et al. Gut dysbiosis in rheumatic diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 92 observational studies. EBioMedicine. 2022, 80, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cao, Y.; Lu, H.; Xu, W.; Zhong, M. Gut microbiota and Sjögren's syndrome: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1187906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Lu, Y. Gut microbiota and derived metabolomic profiling in glaucoma with progressive neurodegeneration. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022, 12, 968992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jia, X.M.; Wu, B.X.; Chen, B.D.; Li, K.T.; Liu, Y.D.; Xu, Y.; et, a. Compositional and functional aberrance of the gut microbiota in treatment-naïve patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome. J Autoimmun. 2023, 141, 103050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labetoulle, M.; Baudouin, C.; Benitez Del Castillo, J.M.; Rolando, M.; Rescigno, M.; Messmer, E.M.; et al. How gut microbiota may impact ocular surface homeostasis and related disorders. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2024, 100, 101250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).