Introduction

Sleep disorders are a prevalent and serious comorbidity in dry eye [

1]. While insomnia severity is positively correlated with dry eye disease (DED) severity [

2,

3], results are not that straightforward for the hypersomnia situation. Only limited studies have investigated this association. Results of National Claim Data in South Korea demonstrated that sleep disorders were positively associated with DES diagnosis. Positive trends were more common in younger patients, males, lower economic levels, and those with higher levels of comorbid in South Koreans [

4]. Also, data from an Integrated Health Care Network in China showed that sleep disorder was associated with a three-fold increase in risk of DED [

5]. However these two studies had not categorized their data by sleep disorder classifications [

4,

5]. Therefore, there is still uncertainty about the direction of this association, if there is any association at all.

These results are pertinent regarding the issue of whether there is a connection among (i) insomnia/hypersomnia, (ii) ocular conditions such as DED, and (iii) gut microbiota composition. Contemporary investigations infer the existence of a gut-eye microbiota axis [

6,

7]. There are even more interesting facts to observe. We recently reported that gut microbiota transmission change the sleep pattern in healthy spouses married to insomniac or hypersomniac spouses (ref). Furthermore, poor sleep has an important role in the development of DED and vice versa [

8,

9,

10]. In addition to this, excessive yawning in many cases could be attributed to hypersomnia[

11,

12,

13], while paradoxically, yawning frequently occurs in insomniac people mainly due to disturbed sleep [

14]. On the other hand, yawning may facilitate lacrimation [

15] and consequently may relieve eye dryness. Finally, from the perspective of microbiota studies, recent sophisticated studies using Metagenomics shows that there is substantial difference in terms of ocular microbiota between healthy eyes and those with DED [

16].

Based on all these interconnected premises, we hypothesized that ocular microbiota alterations in newly married couples, possibly through person-to-person contact, may change the severity and/or occurrence of DED through ocular microbiota changes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (IT. 24001670) and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written and signed informed consents were obtained for all volunteer couples who were recruited from two private sleep clinics in Tehran, Iran. A total of 870 couples who had married during the past six months and were in a cohabiting relationship were invited to participate in this study together with their official spouses.

Exclusion criteria were as marriage below 18 years of age, antibiotic uses in the past month, ongoing, and active ocular infection, including conjunctivitis, and eyelid disorders affecting blinking. Couples were also required to not have any prior history with DED, a history of ophthalmic surgery, any systemic disease including autoimmune disease and diabetes, or use of systemic, photosensitizing, or ocular medications except unpreserved lubricants one month before and during the study. Those taking sleep medications or antidepressants, and contact lens use within three months of or during the study were excluded.

Overall, twelve couples were excluded because the women were taking medicines known to affect ocular microbiota composition. Thirteen couples were excluded due for personal reasons. The remaining 815 couples were all living with their spouses in a same house.

Assessment of Sleep Quality and DED

The participants voluntarily completed the validated Persian versions of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Inventory (PSQI) [

17]. Insomnia was defined as coexistence of both daytime dysfunction and difficulty resuming sleep [

18]. Hypersomnia was defined by a bed-rest total sleep time ≥19 hour during the 32-hour recording [

19]. Participants were categorized as healthy spouses, insomniac spouses and hypersomniac spouses.

Ocular surface variables were assessed at Day 1 and Day 180. Participants were asked to fill out the validated Persian version of Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) which is used to evaluate the DED severity, as recommended by the accepted guidelines [

20]. According to the OSDI score, DED is classified as mild (13–22 points), moderate (23–32 points), or severe (33–100 points). We combined mild and moderate-to-severe DED. Schirmer’s test without anesthesia was performed on both eyes and the mean was calculated for all participants who had DED for use in the study. Finally, tear osmolarity was measured once from each eye using the TearLab Osmolarity System (TearLab Corporation, Inc, San Diego, CA) [

21]. DED results are reported as the average of the two eyes of each participant ± SD.

Ocular Microbiora Sample Collection and Culture

The detailed procedure for sample collection and bacterial culture is describe elsewhere [

16]. Briefly, culture of the lower conjunctival sac was collected by two qualified ophthalmologists using sterile nylon swabs (FloqSwabs, Copan, Italy), without any topical anesthetic. Tear samples were taken from both eyes. Then, a Floq swab was applied to both eyes and was used for culture analysis. Conjunctiva and tear samples were collected in a standard way by the same qualified ophthalmologist. Swabs were sealed in containers without any medium and placed on ice instantly after the collection and during transportation to the laboratory. Then, swabs from all participants were used to inoculate agar growth medium immediately upon arrival at the laboratory (about 4-6 h). For susceptibility testing of Staphylococcus sp. and Enterococcus sp. we applied a product protocol [

22] using GPALL1F plates (Sensititre; Thermo Scientific).

Data analyses of clinical samples and statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS version 24.0.0.2. The chi-square test was used to compare the frequency of DED among the groups. For normally distributed data, we used ANOVA to compare the means of the groups. For non-normally distributed data, we used the Kruskal–Wallis test and post hoc analyses were performed using the Tukey-Kramer protected least significant difference test. Alpha and Beta diversity was evaluated using Shannon’s diversity index and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity, respectively. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were used to assess the correlation between ocular microbiota and DED. Age and sex differences were analyzed to discard any existing statistical influence. Statistical analyses of date related to ocular microbiota were done using microbiome R packages [

23]. P< 0.05 represents statistical significance.

Results

This is an interim result and the detailed results will be published in full in a peer-reviewed journal. Men had an average age of 36.40 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 7.20. 81.7% had attained a college degree. Women had an average age of 30.30 years (SD = 8.70), and 87.2% had attained a college degree. The couples had been married and living together for an average of 6.10 months (SD = 0.90).

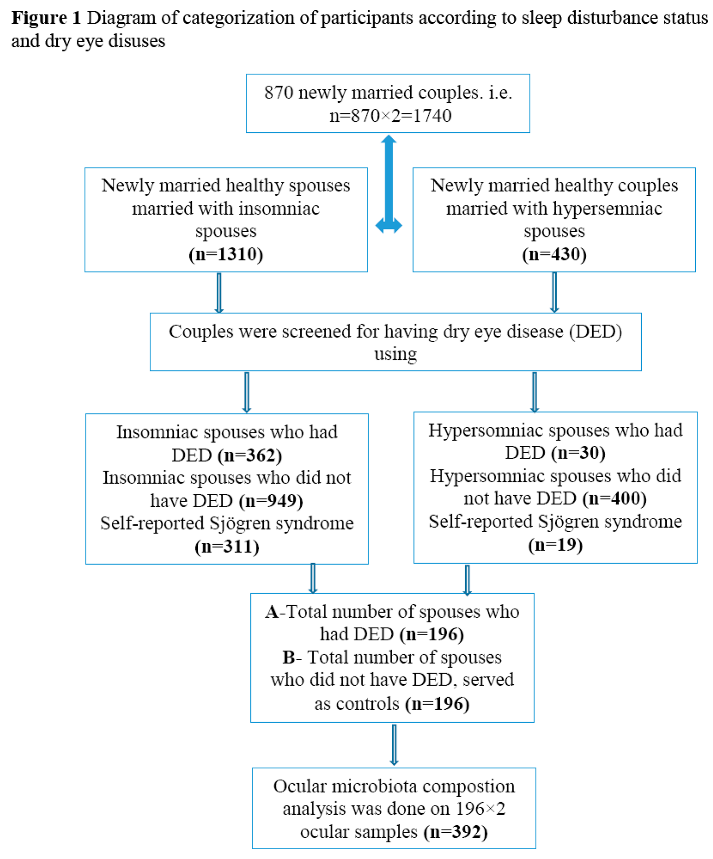

The diagram of categorization and enrollment of participants is shown in Figure 1.

Overall, data drawn from 870 couples were analyzed for general characteristics (see Figure 1), however, as for ocular microbiota composition, we only analyzed the 392 participants who had definite DED.

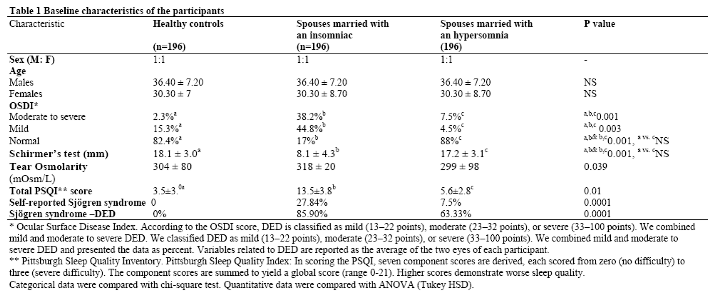

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the participants. As can be seen from this table, the frequency of severe DED in spouses who had married with an insomniac person was significantly higher than healthy controls at baseline. Self-reported Sjögren's Syndrome-related DED in spouses who had married to an insomniac and a hypersomniac person was 85.9% (311 out of 326) and 63.33 (19 out of 30) (63.33%), respectively.

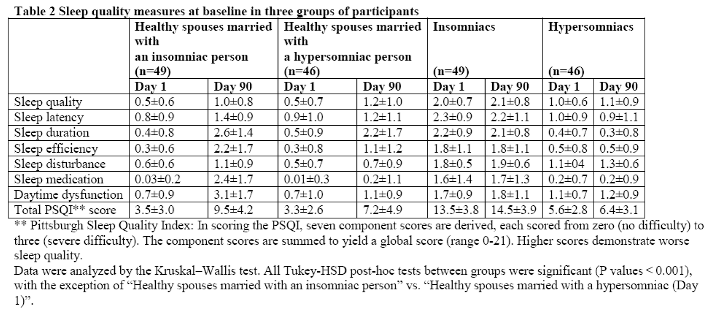

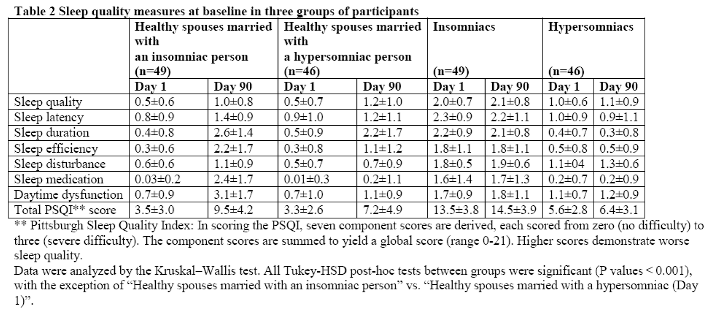

As can be seen from Table 2, mean total PSQI score in a subsample of spouses who had married an insomniac person was significantly higher than that of the two other groups. In general, healthy controls, and spouses who had married a hypersomniac person were more similar to one another than were spouses who had married an insomniac person (Table 2).

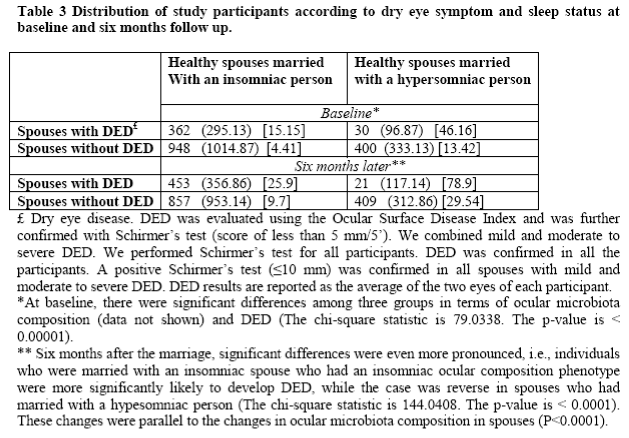

Distribution of DED among Participants

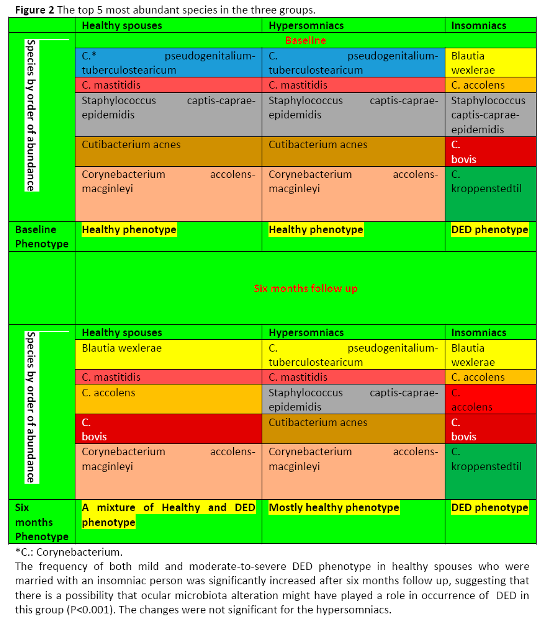

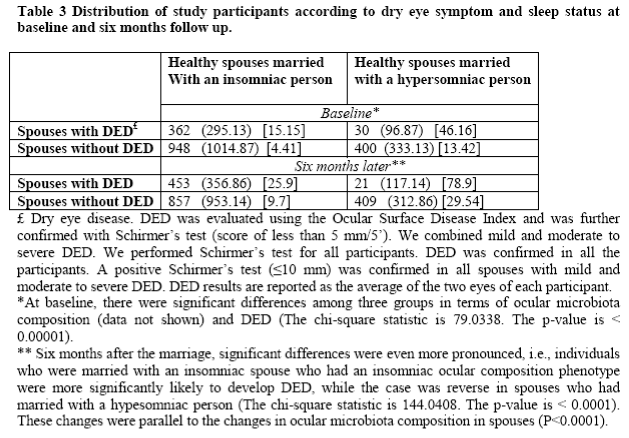

Table 3 demonstrates the distribution of study participants according to dry eye symptoms and sleep status at baseline and six months follow up. At baseline, there were significant differences among the three groups in terms of ocular microbiota composition (see below) and DED frequency. However, six months after marriage, these significant differences were even more pronounced, i.e., individuals who were married with an insomniac spouse having DED phenotype (see Figure 2), were more significantly likely to develop DED after six months follow up. Interestingly, the case was reverse in spouses who had married with a hypersomniac person. In support of our initial hypothesis, these changes occurred in parallel to the changes in ocular microbiota composition (see below, P <0.0001). After six months, ocular microbiota composition in healthy spouses who did not have DED and had a normal sleep pattern were significantly changed and became similar to that of participant's insomniac spouse. If the spouse was insomniac, then ocular microbiota composition became similar to his/her insomniac spouse (P < 0.001).

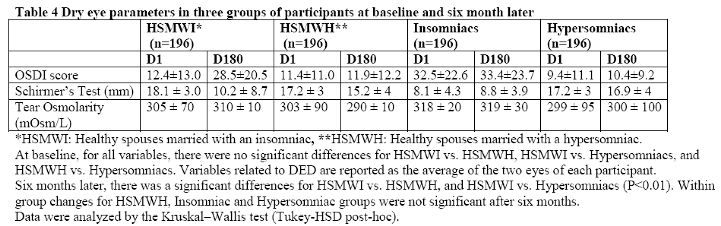

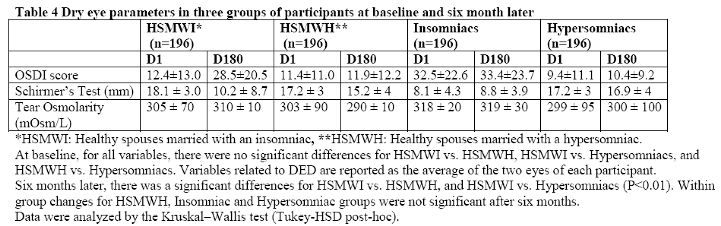

Table 4 shows dry eye parameters in the three groups of participants at baseline and six months later. Notably, after six months follow-up, tear osmolality and OSDI scores in healthy spouses married with an insomniac spouse were significantly changed and becomes similar to that of participant's spouse (all P values <0.001), while the reverse was true in case of Schirmer’s test (P <0.01). Interestingly, eye parameters were better for hypersomniac group and healthy spouses who had married with hypersomniacs. In these two groups, OSCDI score, Schirmer’s and tear osmolality were close to normal values. Hypersominacs and healthy spouses who had married a hypersomniac had the best values both at baseline and after six months follow-up. Mean Schirmer's test values were significantly lower in spouses who had married an insomniac person. Mean tear osmolality in healthy controls and in spouses who had married a hypersomiac were similar. However mean tear osmolality values in spouses who had married an insomniac person were significantly higher than that of the two other groups (P<0.01).

Alpha and Beta Diversity among Participants

There were significant differences in alpha diversity among the three groups of newly married couples who had married with an insomniac or hypersomniac spouse: the healthy control group with healthy sleep pattern, had the highest similarity (Chao1, Faith's phylogenetic diversity), while the mild DED group demonstrated the highest diversity (Shannon, Simpson), and the moderate-to-severe DED group had the lowest similarity for the above-mentioned indices.

Interestingly, reduction in beta diversity of the ocular microbial community was positively associated with DED severity, with the moderate-to-severe DED group exhibiting the lowest beta diversity. Linear discriminant analysis effect size showed marked dominant taxa that were significantly different among each group. In addition, random forest analysis showed that exacerbation of DED corresponds with the enrichment of certain pathogenic bacteria.

Identification of Species Differences and Marker Species

At baseline, the vast majority of the 392 analyzed ocular samples from healthy spouses and healthy hypersomniacs were highly enriched with Staphylococcus, whereas only in a few of them, other genera such as Corynebacterium, Bacillus and Pseudomonas predominated.

C. pseudogenitalium-tuberculostearicum and C. mastitidis were also abundant in these two groups.

On the other hand, in the group of insomniacs, Blautia wexlerae was found to be most associated with DED followed by different Corynebacterium species, namely C. accolens, C. bovis and C. kroppenstedtil. Figure 2 shows the top 5 most abundant species in the three groups.

Correlation of DES with Ocular Microbiota

The DED phenotype was positively significantly correlated with species differences in each of the three groups (P value <0.001). At baseline, the frequency of both mild and moderate-to-severe DED phenotype was significantly highest in insomniacs. Interestingly, in support of our hypothesis, the frequency of both mild and moderate-to-severe DED phenotype in healthy spouses was significantly increased after six months of marriage with an insomniac person (but not with a hypersomniac person), suggesting that there is a possibility that ocular microbiota alteration might have played a role in the occurrence of DED in this group.

Discussion

We found that the frequency of DED in spouses who married insomniac spouses with DED phenotype significantly increased over time, as compared to baseline values. In line with our initial hypothesis, the occurrence of DED in healthy spouses corresponded with the enrichment of certain pathogenic bacteria which was quite similar to the abundance pattern of ocular microbuta in their corresponding spouses. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to provide preliminary empirical evidence suggesting that ocular microbiota transmission between two people may play a role in the development of DED, particularly over such a short term, about 6 months follow-up.

Ocular microbiota composition in DED participants in our study was similar to the results of other reports [

16,

24,

25,

26], with highest resemblance to [

16]. The reason may partly be that we applied the same methodology [

16]. We noticed that as DED occurrence increases, microbial community diversity tends to decrease. This is in agreement with Zou et al

[26]. DED frequency corresponds with alterations in microbial constituents, primarily characterized by diminished microbial diversity and a more uniform species composition.

We found that Blautia wexlerae was the most associated with DED followed by different Corynebacterium species, namely C. accolens, C. bovis and C. kroppenstedtil. Despite Staphylococcus captis-caprae-epidemidis [

27], Corynebacterium bovis [

28] and Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii [

29] which are generally regarded as opportunistic pathogens, both C. accolens and Blautia wexlerae are generally considered as commensal bacteria [

30,

31]. Blautia wexlerae is an anaerobic and gram-positive bacteria that lives in the human intestine [

31] and C. accolens is a lipophilic species which is commonly found in the oropharynx, nose, ears, and eyes [

30]. These two species are not pathogenic per se. For instance, a recent comprehensive metagenomics study found that in Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients, Blautia wexlerae was decreased by fivefold compared to neurologically healthy controls [

32].

Self-reported Sjögren's Syndrome-related DED in spouses who had married to an insomniac and a hypersomniac person was 85.9%, which is relatively high compared to other studies [

33] and might be partially related to severity of insomnia in participants of current study. Also, higher frequency of insomnia was found in insomniacs with symptomatic DED, and insomnia correlated significantly with DED symptoms, which is in agreement with other studies [

34].

Sjögren's Syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disorder that affects exocrine glands, typically the lacrimal and salivary glands, leading to dry mouth and dry eye [

35]. On the other hand, SS may lead to decreased diversity of the ocular surface microbial community [

36], which can be potentially casually related to the pathophysiology of DED, particularly in patients with SS, as results of some Mendelian randomization studies suggest [

37,

38,

39].

Regarding the possible role of gut microbiota in DED, our previous study [

40] revealed that three months after the marriage, spouses with healthy sleep patterns were significantly more likely to resemble their insomniac or hypersomniac couples. Gut microbiota composition in participants with normal sleep patterns was significantly changed and becomes similar to that of the participant’s spouse, i.e., if the spouse was insomniac or hypersomniac, then gut composition becomes similar to his/her insomniac or hypersomniac spouse, respectively. The results of mediation analysis confirmed the association between the changes in the sleep pattern and changes in the gut microbiota. This novel study provides indirect evidence suggesting that closeness between couples may potentially have a role in DED through changes in gut microbiota composition.

Goodman et al [

41] in a case-control study, examined the composition of the gut microbiota in individuals with and without immune-mediated DED. They found clear differences in gut microbita composition in individuals with mostly early markers of SS compared with controls. There are other studies confirming that gut dysbiosis is prevailing in SS patients and is related to DED severity [

42].

According to a review article by Moon et al [

43], recent clinical studies have typically discovered an association between clinical manifestations of SS such as DED and gut dysbiosis, whereas environmental DED displays characteristics between normal and autoimmune. Furthermore, a decrease in both the genus Faecalibacterium and Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio have most typically been seen in patients with SS. Interested readers may refer to a review article by Moon et al [

43].

This paper is obviously not intended to provide a detailed discussion on mechanistic and metagenomic analysis. However, if it proves that the association between these species and increased frequency of DED in healthy spouses married to insomniac individuals is a cause-and-effect relationship, then, one possible mechanism is that following marriage and spouse-to-spouse contact, some species might competitively displace other native species, as

Figure 2 suggests. In support of this argument, in animal models of SS, it is shown that commensal bacteria protect lacrimal glands through immunoregulatory properties [

44]. Indeed, one of the authors has elsewhere [

45] discussed how closeness may facilitate bacterial transmission and consequently, change gut and ocular microbiota in people who are in close contact with one another such, as the couples in the present study. The animal models can provide platforms for further investigation of the underlying mechanism of DED and its association with gut and ocular microbiota.

The frequency of both mild and moderate-to-severe DED in hypersomniacs was similar to the healthy group. This might be related to higher yawning frequency in hypersomniacs, which in turn relates to higher ocular lacrimation [

15,

46]. However, we did not measure yawning in our study. We also did not take into account higher rates of yawning frequency in hypesomniac and their spouses, because these were all self-reported and we were not sure how reliable these self-reports were. Future studies may consider assessing yawning frequency quantitatively.

We could not find any study assessing ocular microbiota composition in insomniac and hypersomniac people. Therefore, our report contributes to the literature regarding the profile of ocular microbiota composition in sleep-related disorders. We suggest that within the framework of diagnostic, predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine, the practical and theoretical implications of this study may add to the understanding of broad areas of microbiota-host research.

Strengths

To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting parallel changes in ocular microbiota and DED frequency and severity. Also, we used a large sample size with minimum dropout rate. Finally, we propose a paradigm-changing hypothesis that DED can be partially a transmitted disease.

Limitations

Many other confounding factors, such as screen viewing, face mask use, occupation, personal hygiene, and contact lens use are involved in DED and sleep status. Future research could gather data on a larger sample size. We did not measure noninvasive Keratograph tear break-up time, tear meniscus height and many other relevant ocular parameters due to budget constraints. Another limitation of this study is that, due to the obligation to deliver the required treatment to the participants with DED, we could not observe long-term impact. We used a culture- based method. Future studies may use sequencing methods. Finally, our findings are cross sectional in nature and do not infer causality. Mechanistic studies in animal models are necessary.

Conclusions

In summary, most contemporary strategies are focused on increasing ocular surface

humidity and decreasing inflammation and osmolarity. Future medications and supplements may

improve ocular microbiota composition and tear osmolarity at the ocular surface. This novel strategy should be considered in future investigations and clinical trials. Furthermore, within the framework of diagnostic, predictive and preventive personalized medicine (and family medicine as well), the practical and theoretical implications of this study cover many areas of medicine, including host-microbiota research and sleep studies.

Future Directions

Recent studies suggest that gut microbiota profiles in myopes and nonmyopes may be different [

47,

48]. Other studies show an association with intraocular inflammation [

49], corneal neovascularization [

50], fungal micobiota [

51] and other ocular surface pathophysiology and disorders [

52]. This creates a unique opportunity for future microbiota and host research using animal models.

Author Contributions

R. R. and F.M. analyzed the literature and drafted the manuscript. B. V., A. S. and C. G. I. participated in project design, concept development, and manuscript revision. Y. A. and S. S. conceived the paper concept and did ophthalmological examinations and critically revised the manuscript. R. R conceived the concept, designed the project, coordinated the preparation of the manuscript, critically revised the manuscript, and was responsible for the financial support. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgement

Authors extend their sincere gratitude to Dr. Michael W Gaynon (Byers Eye Institute at Stanford University, Palo Alto, California) for review of the current article. We would like to thank the couples who participated in the pilot study. We also wish to especially thank Dr. Javid Azizi very much for his generous financial support of this project, and for his careful involvement in each stage of the work.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- M. Ayaki, K. Tsubota, M. Kawashima, T. Kishimoto, M. Mimura, K. Negishi, Sleep Disorders are a Prevalent and Serious Comorbidity in Dry Eye, Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 59(14) (2018) DES143-DES150.

- A. Galor, B.E. Seiden, J.J. Park, W.J. Feuer, A.L. McClellan, E.R. Felix, R.C. Levitt, C.D. Sarantopoulos, D.M. Wallace, The Association of Dry Eye Symptom Severity and Comorbid Insomnia in US Veterans, Eye Contact Lens 44 Suppl 1(Suppl 1) (2018) S118-S124.

- G. Qin, X. Luan, J. Chen, L. Li, W. He, E. Eric Pazo, X. He, S. Yu, Effects of insomnia on symptomatic dry eye during COVID-19 in China: An online survey, Medicine (Baltimore) 102(46) (2023) e35877.

- K.T. Han, J.H. Nam, E.C. Park, Do Sleep Disorders Positively Correlate with Dry Eye Syndrome? Results of National Claim Data, Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(5) (2019).

- Q. Zheng, S. Li, F. Wen, Z. Lin, K. Feng, Y. Sun, J. Bao, H. Weng, P. Shen, H. Lin, W. Chen, The Association Between Sleep Disorders and Incidence of Dry Eye Disease in Ningbo: Data From an Integrated Health Care Network, Front Med (Lausanne) 9 (2022) 832851.

- J.L. Floyd, M.B. Grant, The gut–eye axis: lessons learned from murine models, Ophthalmology and therapy 9(3) (2020) 499-513.

- W. Xue, J.J. Li, Y. Zou, B. Zou, L. Wei, Microbiota and ocular diseases, Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 11 (2021) 759333.

- J.A. Gomes, R.M. Santo, The impact of dry eye disease treatment on patient satisfaction and quality of life: A review, The ocular surface 17(1) (2019) 9-19.

- W. Lee, S.-S. Lim, J.-U. Won, J. Roh, J.-H. Lee, H. Seok, J.-H. Yoon, The association between sleep duration and dry eye syndrome among Korean adults, Sleep medicine 16(11) (2015) 1327-1331.

- M. Wu, X. Liu, J. Han, T. Shao, Y. Wang, Association between sleep quality, mood status, and ocular surface characteristics in patients with dry eye disease, Cornea 38(3) (2019) 311-317.

- Y. Dauvilliers, A. Buguet, Hypersomnia, Dialogues in clinical neuroscience 7(4) (2005) 347-356.

- A.G. Guggisberg, J. Mathis, U.S. Herrmann, C.W. Hess, The functional relationship between yawning and vigilance, Behavioural brain research 179(1) (2007) 159-166.

- M.A. Lana-Peixoto, D. Callegaro, N. Talim, L.E. Talim, S.A. Pereira, G.B. Campos, Pathologic yawning in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders, Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders 3(4) (2014) 527-532.

- V. Guidetti, C. Dosi, O. Bruni, The relationship between sleep and headache in children: implications for treatment, Cephalalgia 34(10) (2014) 767-76.

- R. Rastmanesh, How Mandibular Movement Intersects with Ocular Lacrimation: A Literature Synthesis, Ophthalmology and Vision Care 2(1) (2022).

- M. Naqvi, F. Fineide, T.P. Utheim, C. Charnock, Culture-and non-culture-based approaches reveal unique features of the ocular microbiome in dry eye patients, The Ocular Surface 32 (2024) 123-129.

- A. Chehri, N. Goldaste, S. Ahmadi, H. Khazaie, A. Jalali, Psychometric properties of insomnia severity index in Iranian adolescents, Sleep Science 14(2) (2021) 101.

- Kaneita, T. Munezawa, K. Mishima, M. Jike, S. Nakagome, M. Tokiya, T. Ohida, Nationwide epidemiological study of insomnia in Japan, Sleep Medicine 25 (2016) 130-138.

- E. Evangelista, R. Lopez, L. Barateau, S. Chenini, A. Bosco, I. Jaussent, Y. Dauvilliers, Alternative diagnostic criteria for idiopathic hypersomnia: a 32-hour protocol, Annals of neurology 83(2) (2018) 235-247.

- J.R. Grubbs Jr, S. Tolleson-Rinehart, K. Huynh, R.M. Davis, A review of quality of life measures in dry eye questionnaires, Cornea 33(2) (2014) 215-218.

- J.S. Wolffsohn, R. Arita, R. Chalmers, A. Djalilian, M. Dogru, K. Dumbleton, P.K. Gupta, P. Karpecki, S. Lazreg, H. Pult, TFOS DEWS II diagnostic methodology report, The ocular surface 15(3) (2017) 539-574.

- R. Humphries, A.M. Bobenchik, J.A. Hindler, A.N. Schuetz, Overview of changes to the clinical and laboratory standards institute performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, M100, Journal of clinical microbiology 59(12) (2021) 10.1128/jcm. 00213-21.

- S.A. Shetty, L. Lahti, Microbiome data science, Journal of biosciences 44 (2019) 1-6.

- J. Andersson, J.K. Vogt, M.D. Dalgaard, O. Pedersen, K. Holmgaard, S. Heegaard, Ocular surface microbiota in patients with aqueous tear-deficient dry eye, The ocular surface 19 (2021) 210-217.

- Z. Zhang, X. Zou, W. Xue, P. Zhang, S. Wang, H. Zou, Ocular surface microbiota in diabetic patients with dry eye disease, Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 62(12) (2021) 13-13.

- X.-R. Zou, P. Zhang, Y. Zhou, Y. Yin, Ocular surface microbiota in patients with varying degrees of dry eye severity, International Journal of Ophthalmology 16(12) (2023) 1986.

- C.E. Chong, R.J. Bengtsson, M.J. Horsburgh, Comparative genomics of Staphylococcus capitis reveals species determinants, Frontiers in microbiology 13 (2022) 1005949.

- J. Vale, G. Scott, Corynebacterium bovis as a cause of human disease, The Lancet 310(8040) (1977) 682-684.

- N. Saraiya, M. Corpuz, Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii: a challenging culprit in breast abscesses and granulomatous mastitis, Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 31(5) (2019) 325-332.

- L.M. Ang, H. Brown, Corynebacterium accolens isolated from breast abscess: possible association with granulomatous mastitis, Journal of clinical microbiology 45(5) (2007) 1666-1668.

- C. Liu, S.M. Finegold, Y. Song, P.A. Lawson, Reclassification of Clostridium coccoides, Ruminococcus hansenii, Ruminococcus hydrogenotrophicus, Ruminococcus luti, Ruminococcus productus and Ruminococcus schinkii as Blautia coccoides gen. nov., comb. nov., Blautia hansenii comb. nov., Blautia hydrogenotrophica comb. nov., Blautia luti comb. nov., Blautia producta comb. nov., Blautia schinkii comb. nov. and description of Blautia wexlerae sp. nov., isolated from human faeces, International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology 58(8) (2008) 1896-1902.

- Z.D. Wallen, A. Demirkan, G. Twa, G. Cohen, M.N. Dean, D.G. Standaert, T.R. Sampson, H. Payami, Metagenomics of Parkinson’s disease implicates the gut microbiome in multiple disease mechanisms, Nature communications 13(1) (2022) 6958.

- M. Rolando, D. Arnaldi, A. Minervino, P. Aragona, S. Barabino, Dry eye in mind: Exploring the relationship between sleep and ocular surface diseases, European Journal of Ophthalmology 34(4) (2024) 1128-1134.

- M. Kawashima, M. Yamada, C. Shigeyasu, K. Suwaki, M. Uchino, Y. Hiratsuka, N. Yokoi, K. Tsubota, D.-J.S. Group, Association of systemic comorbidities with dry eye disease, Journal of Clinical Medicine 9(7) (2020) 2040.

- G.N. Foulks, S.L. Forstot, P.C. Donshik, J.Z. Forstot, M.H. Goldstein, M.A. Lemp, J.D. Nelson, K.K. Nichols, S.C. Pflugfelder, J.M. Tanzer, Clinical guidelines for management of dry eye associated with Sjögren disease, The ocular surface 13(2) (2015) 118-132.

- Y.C. Kim, B. Ham, K.D. Kang, J.M. Yun, M.J. Kwon, H.S. Kim, H.B. Hwang, Bacterial distribution on the ocular surface of patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome, Scientific reports 12(1) (2022) 1715.

- Y. Cao, H. Lu, W. Xu, M. Zhong, Gut microbiota and Sjögren’s syndrome: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study, Frontiers in Immunology 14 (2023) 1187906.

- K. Liu, Y. Cai, K. Song, R. Yuan, J. Zou, Clarifying the effect of gut microbiota on allergic conjunctivitis risk is instrumental for predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine: a Mendelian randomization analysis, EPMA Journal 14(2) (2023) 235-248.

- W. Zhang, X. Gu, Q. Zhao, C. Wang, X. Liu, Y. Chen, X. Zhao, Causal effects of gut microbiota on chalazion: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study, Frontiers in Medicine 11 (2024) 1411271.

- R. Rastmanesh, F. Marotta, Person-to-Person Bacterial Transmission Can Change the Sleep Pattern in Newly Married Couples, (2024).

- C.F. Goodman, T. Doan, D. Mehra, J. Betz, E. Locatelli, S. Mangwani-Mordani, K. Kalahasty, M. Hernandez, J. Hwang, A. Galor, Case–Control Study Examining the Composition of the Gut Microbiome in Individuals With and Without Immune-Mediated Dry Eye, Cornea 42(11) (2023) 1340-1348.

- X. Bai, Q. Xu, W. Zhang, C. Wang, The Gut–Eye Axis: Correlation Between the Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Dry Eye in Individuals With Sjögren Syndrome, Eye & Contact Lens 49(1) (2023) 1-7.

- J. Moon, C.H. Yoon, S.H. Choi, M.K. Kim, Can gut microbiota affect dry eye syndrome?, International journal of molecular sciences 21(22) (2020) 8443.

- M. Zaheer, C. Wang, F. Bian, Z. Yu, H. Hernandez, R.G. de Souza, K.T. Simmons, D. Schady, A.G. Swennes, S.C. Pflugfelder, Protective role of commensal bacteria in Sjögren Syndrome, Journal of autoimmunity 93 (2018) 45-56.

- R. Rastmanesh, Does person-to-person contact confound microbiota research? An important consideration in the randomization of study arms, Exploratory Research and Hypothesis in Medicine accepted and in press (2024).

- M. Romano, R. Di Leo, D. Mascarella, G. Pierangeli, A. Rufa, Pupillary and Lacrimation Alterations, Autonomic Disorders in Clinical Practice, Springer2023, pp. 353-385.

- H. Li, Y. Du, K. Cheng, Y. Chen, L. Wei, Y. Pei, X. Wang, L. Wang, Y. Zhang, X. Hu, Gut microbiota-derived indole-3-acetic acid suppresses high myopia progression by promoting type I collagen synthesis, Cell Discovery 10(1) (2024) 89.

- W.E. Omar, G. Singh, A.J. McBain, F. Cruickshank, H. Radhakrishnan, Gut Microbiota Profiles in Myopes and Nonmyopes, Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 65(5) (2024) 2-2.

- J.J. Li, S. Yi, L. Wei, Ocular microbiota and intraocular inflammation, Frontiers in Immunology 11 (2020) 609765.

- H.J. Lee, C.H. Yoon, H.J. Kim, J.H. Ko, J.S. Ryu, D.H. Jo, J.H. Kim, D. Kim, J.Y. Oh, Ocular microbiota promotes pathological angiogenesis and inflammation in sterile injury-driven corneal neovascularization, Mucosal Immunology 15(6) (2022) 1350-1362.

- Y. Wang, H. Chen, T. Xia, Y. Huang, Characterization of fungal microbiota on normal ocular surface of humans, Clinical Microbiology and Infection 26(1) (2020) 123. e9-123. e13.

- P. Aragona, C. Baudouin, J.M.B. Del Castillo, E. Messmer, S. Barabino, J. Merayo-Lloves, F. Brignole-Baudouin, L. Inferrera, M. Rolando, R. Mencucci, The ocular microbiome and microbiota and their effects on ocular surface pathophysiology and disorders, Survey of ophthalmology 66(6) (2021) 907-925.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).