1. Introduction

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disorder characterized by lymphocytic infiltration and progressive dysfunction of exocrine glands, most notably the lacrimal and salivary glands. This immune-mediated glandular destruction leads to the hallmark sicca symptoms—keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eye disease, DED) and xerostomia (dry mouth)—which significantly impair patients’ quality of life [

1,

2]. The disease predominantly affects middle-aged women, with an estimated global prevalence ranging from 0.1% to 0.6%, varying by classification criteria and geographic region [

2].

Although exocrine involvement is the most prominent feature, pSS is a systemic disease that may also present with arthralgia, interstitial lung disease, renal tubular acidosis, peripheral neuropathy, and vasculitis, reflecting widespread immune dysregulation [

3]. Among these manifestations, ocular involvement—primarily in the form of aqueous-deficient dry eye disease—is particularly burdensome due to its chronicity, symptom fluctuation, and suboptimal therapeutic response [

4,

5]. The pathophysiology of DED in pSS involves both diminished lacrimal gland secretion and inflammatory damage to the ocular surface, resulting in tear film instability, epithelial apoptosis, goblet cell loss, and increased oxidative stress [

4,

5,

6].

These changes reflect a complex immunopathogenic process marked by the activation of both innate and adaptive immune pathways. Histopathological findings reveal infiltration of T and B lymphocytes, upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), and IL-17, and impaired immune tolerance, particularly involving Th17/Treg imbalance [

6,

7]. In addition, oxidative stress—manifested through mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, and reduced antioxidant defenses—further exacerbates inflammation and epithelial injury [

8].

Current therapeutic strategies for managing ocular symptoms in pSS remain largely palliative and often fail to address the underlying immunoinflammatory mechanisms. Common treatments include artificial tears, punctal occlusion, topical cyclosporine A, and short-term corticosteroids; however, these offer only transient relief and are often limited by tolerability issues, local irritation, or systemic side effects [

5,

9]. This has led to a growing interest in adjunctive treatments that not only alleviate symptoms but also modulate immune responses and oxidative stress.

Melatonin, an endogenous indoleamine primarily produced in the pineal gland, has garnered attention due to its multifaceted anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, and antioxidant properties [

10]. Although best known for its role in circadian rhythm regulation, melatonin has demonstrated the ability to suppress nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation, inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome assembly, reduce Th17-mediated cytokine production (e.g., IL-17, IL-6), and promote regulatory T-cell differentiation, thereby restoring immune balance in various inflammatory settings [

10,

11,

12]. Additionally, melatonin enhances mitochondrial function and upregulates key antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase, contributing to cellular protection in oxidative stress-mediated conditions [

13].

In the context of autoimmune and ocular diseases, preclinical evidence has shown that melatonin improves lacrimal secretion, stabilizes the tear film, and mitigates corneal epithelial inflammation. Animal models of DED treated with melatonin demonstrated increased goblet cell density and decreased levels of IL-6 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) at the ocular surface [

12,

14]. Furthermore, melatonin’s capacity to reduce epithelial cell apoptosis and protect against ROS-induced damage reinforces its therapeutic potential in chronic inflammatory ocular diseases [

13].

Despite compelling mechanistic data, clinical research on melatonin use in pSS—especially for its ocular manifestations—remains limited. Most existing studies are either preclinical or focus on non-autoimmune forms of DED, highlighting a significant gap in translational evidence. [

15]. Current therapeutic approaches in autoimmune DED tend to prioritize either symptom control or broad immunosuppression, often neglecting localized immune imbalances and epithelial dysfunction at the ocular surface.

To address this unmet need, the present pilot study aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral melatonin supplementation in patients with pSS and associated dry eye symptoms. Specifically, we assess its effects on objective tear function parameters, ocular surface integrity, and patient-reported symptom burden. Additionally, systemic inflammatory markers are analyzed to explore potential immunological correlates of therapeutic response. By integrating clinical and mechanistic insights, this study seeks to contribute to the development of low-risk, immunomodulatory strategies for managing autoimmune ocular surface disease in pSS.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Ethical Approval

This was a prospective, single-arm, interventional pilot study conducted at the University Department of Ophthalmology, University Hospital Center Sestre milosrdnice in Zagreb, Croatia, from March to August 2024. The primary aim was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of oral melatonin supplementation in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) and associated dry eye symptoms.

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to initiation, the protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of University Hospital Center Sestre milosrdnice (approval number: 251-29-11/3-25-02). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

2.2. Participants

A total of 12 adult patients with a confirmed diagnosis of primary Sjögren’s syndrome were enrolled consecutively from the outpatient registry of the Department of Rheumatology. Diagnosis was established based on the 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) classification criteria, including objective evidence of sicca symptoms, seropositivity for anti-SSA/Ro antibodies, and/or histopathological confirmation where applicable.

Inclusion criteria were as follows:

Age between 18 and 70 years;

Schirmer I test result ≤10 mm in 5 minutes;

Tear Break-Up Time (TBUT) ≤10 seconds;

Moderate to severe dry eye symptoms as indicated by an Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score ≥25;

Absence of active ocular infection or other significant ocular surface pathology.

Exclusion criteria included:

Secondary Sjögren’s syndrome;

Current use of systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppressive therapy, or topical anti-inflammatory eye drops;

Ocular surgery or trauma within the previous 6 months;

Contact lens wear;

Pregnancy or lactation;

Known hypersensitivity to melatonin.

2.3. Intervention

Participants received 5 mg of oral melatonin (Melatonin PharmaS®, Zagreb, Croatia) once daily, taken 60 minutes before bedtime for a continuous period of 8 weeks. All patients were allowed to continue using previously prescribed preservative-free artificial tears, provided that the specific formulation and dosing frequency remained unchanged throughout the study period. Initiation of new topical or systemic therapies targeting dry eye or autoimmune activity was not permitted during the study. Treatment compliance was monitored using a self-reported intake diary.

2.4. Ophthalmological Assessments

Ophthalmological examinations were conducted at baseline and after 8 weeks by the same masked examiner using standardized procedures and instruments. The following objective assessments were performed:

Schirmer I test (without anesthesia): Standardized tear test strips (Tear Touch®, Madhu Instruments, India) were placed in the lower conjunctival fornix for 5 minutes. Wetting length (in mm) was recorded.

Tear Break-Up Time (TBUT): After instillation of fluorescein, the stability of the tear film was evaluated using cobalt blue illumination. The average of three consecutive measurements was recorded.

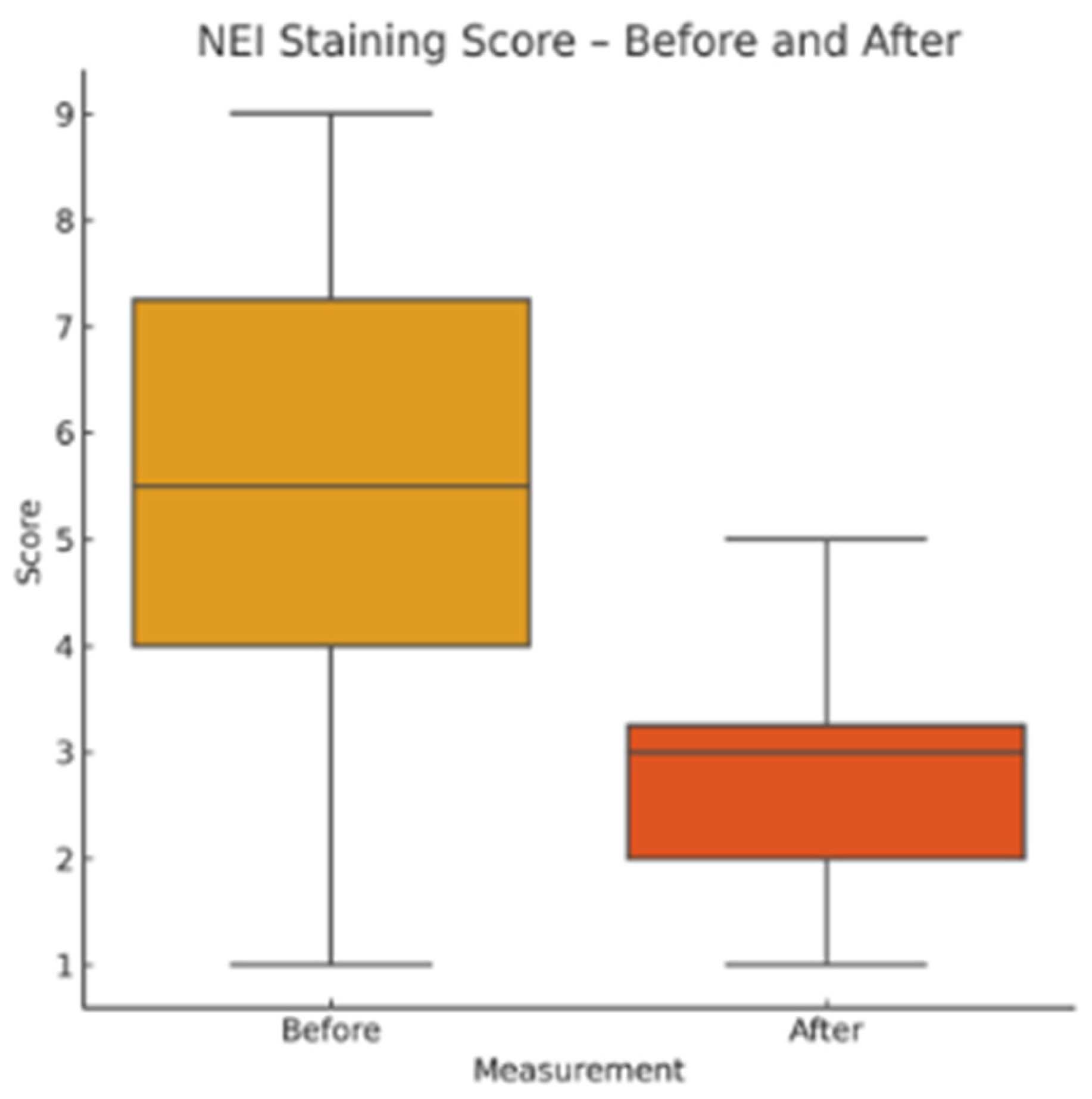

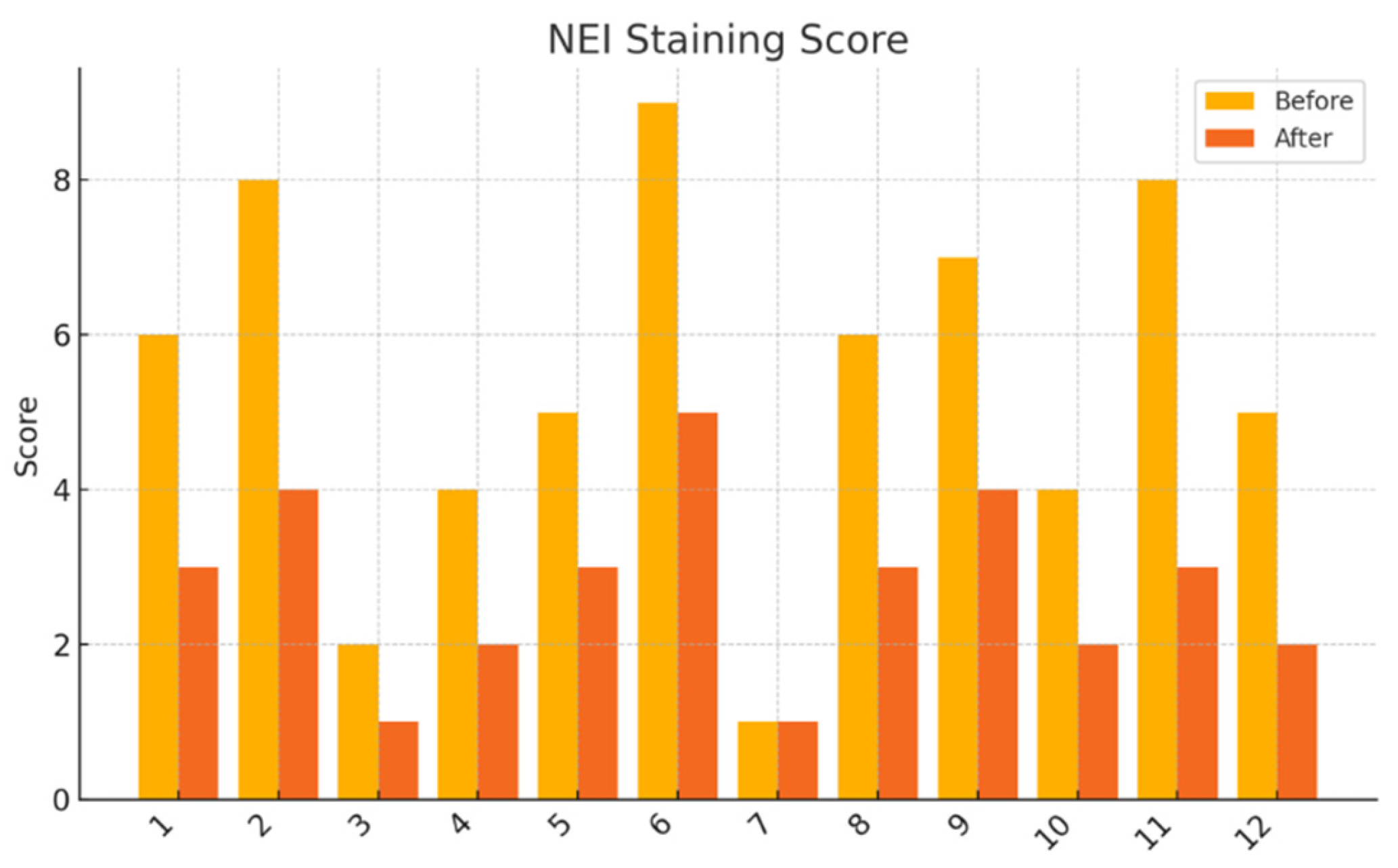

NEI Corneal Staining Score: Fluorescein staining was assessed in five predefined corneal zones (central, superior, inferior, nasal, temporal), each scored from 0 to 3. The total score ranged from 0 to 15.

Corneal Sensitivity: Assessed by gently touching the central cornea with a sterile cotton-tipped applicator and observing the presence or absence of a blink reflex.

2.5. Patient-Reported Outcome Measures

Two validated questionnaires were administered at both study visits to evaluate the subjective burden of disease:

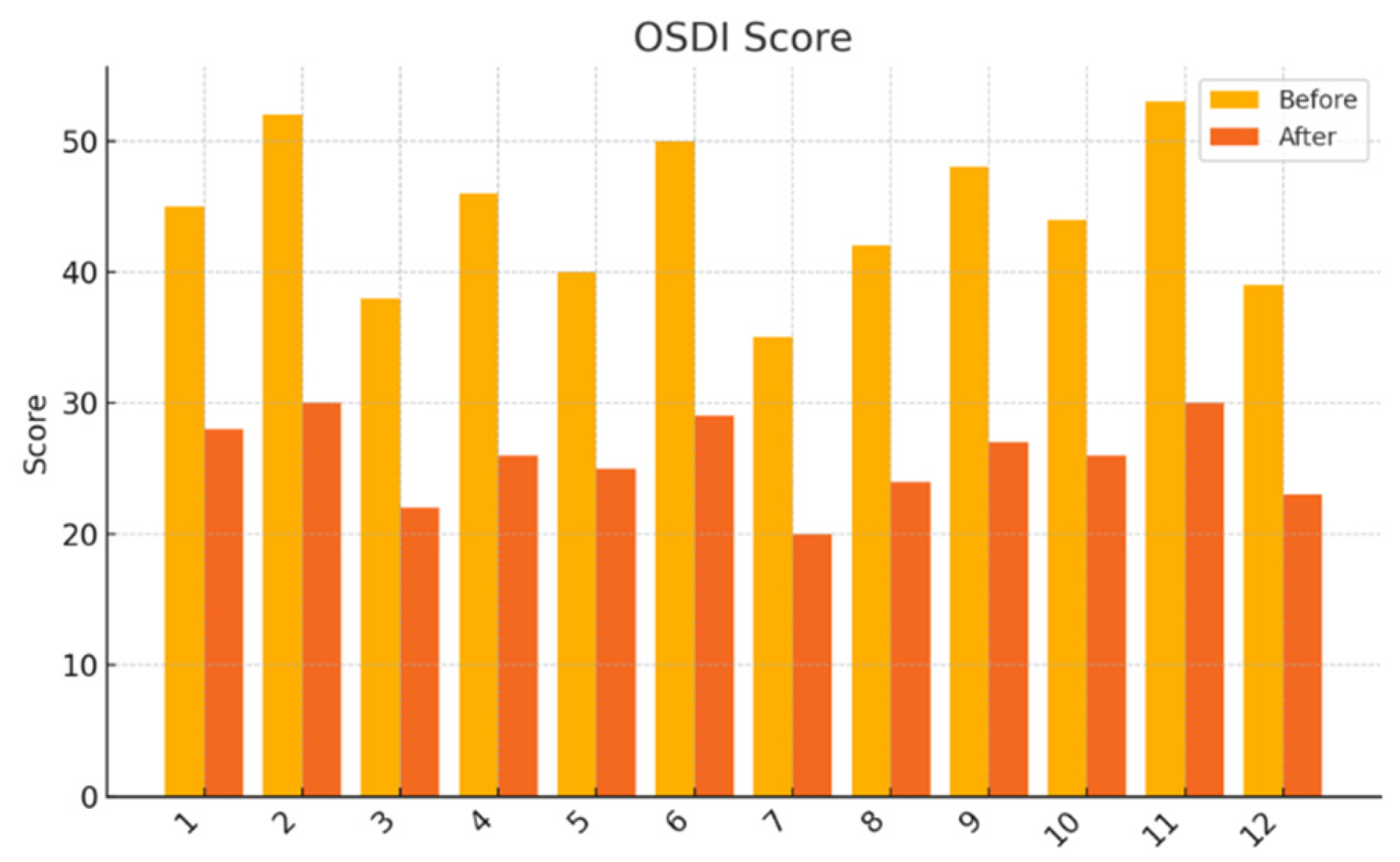

Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI): A 12-item instrument assessing symptom severity, visual function, and environmental triggers over the preceding week. Total scores range from 0 (no symptoms) to 100 (severe symptoms). The validated Croatian translation was used.

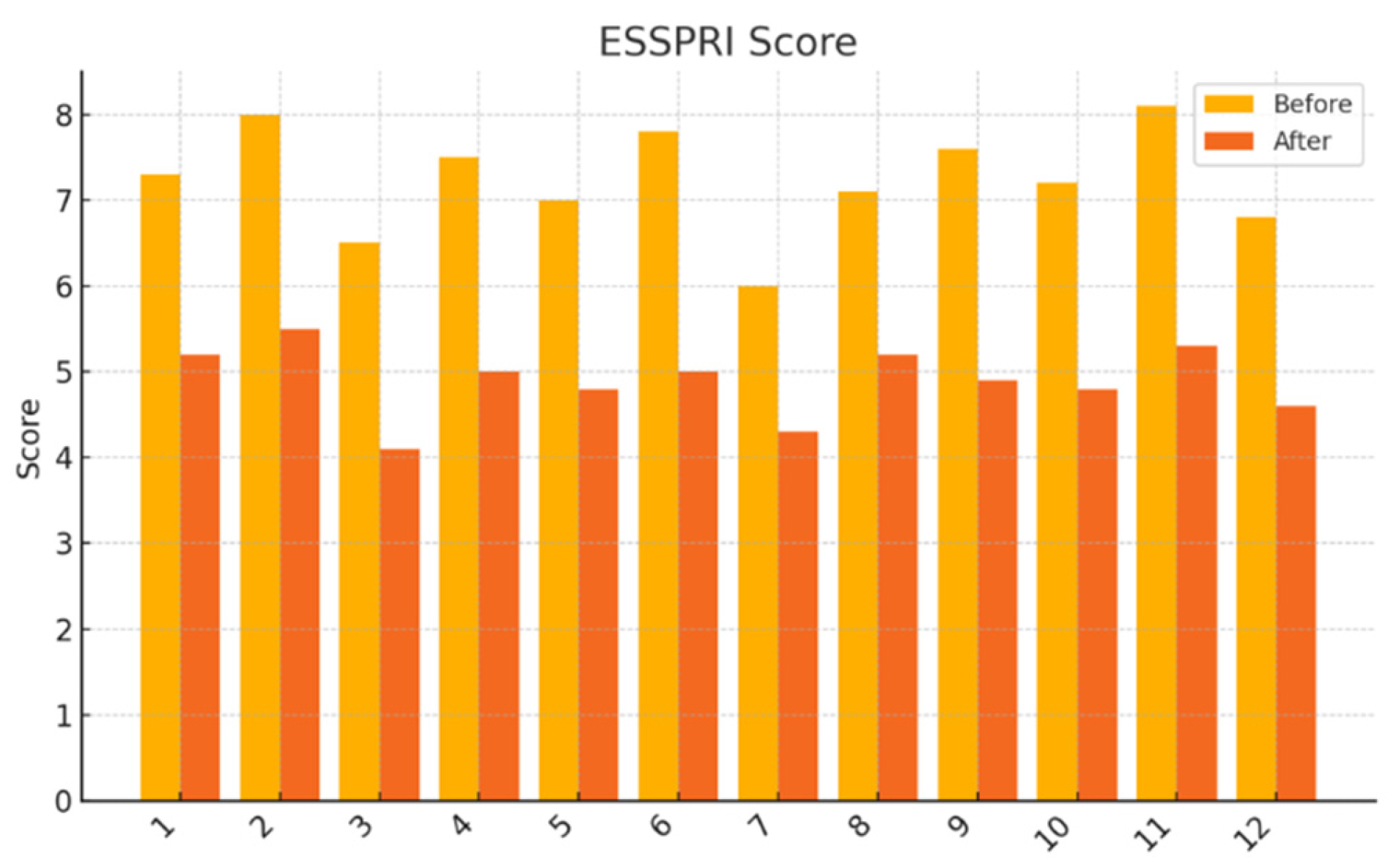

EULAR Sjögren’s Syndrome Patient Reported Index (ESSPRI): Participants rated the severity of dryness, fatigue, and pain on a 0–10 numeric scale. Individual domain scores and mean composite scores were analyzed.

2.6. Laboratory Parameters

Venous blood samples were obtained between 8:00 and 9:30 AM following an overnight fast, at both baseline and week 8. Blood was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 10 minutes, and serum aliquots were stored at −80°C until analysis. The following laboratory markers were evaluated:

Inflammatory markers: C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Cytokine analysis: Serum concentrations of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were quantified using commercially available high-sensitivity enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (R&D Systems®, Minneapolis, MN, USA), with detection limits of 0.156 pg/mL for IL-6 and 0.5 pg/mL for TNF-α.

Immunoglobulin profile: Serum levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM were measured via nephelometry using the Siemens BN II system.

Complement factors C3 and C4: Quantified by immunoturbidimetric assay.

Serum protein electrophoresis: Performed to assess global protein distribution and potential monoclonal or polyclonal gammopathies.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For normally distributed data, comparisons between baseline and post-treatment values were made using paired-sample t-tests. For non-normally distributed data, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed. Categorical variables were analyzed using McNemar’s test.

A two-tailed p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. For primary ophthalmologic endpoints, effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d, and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported where appropriate.

4. Discussion

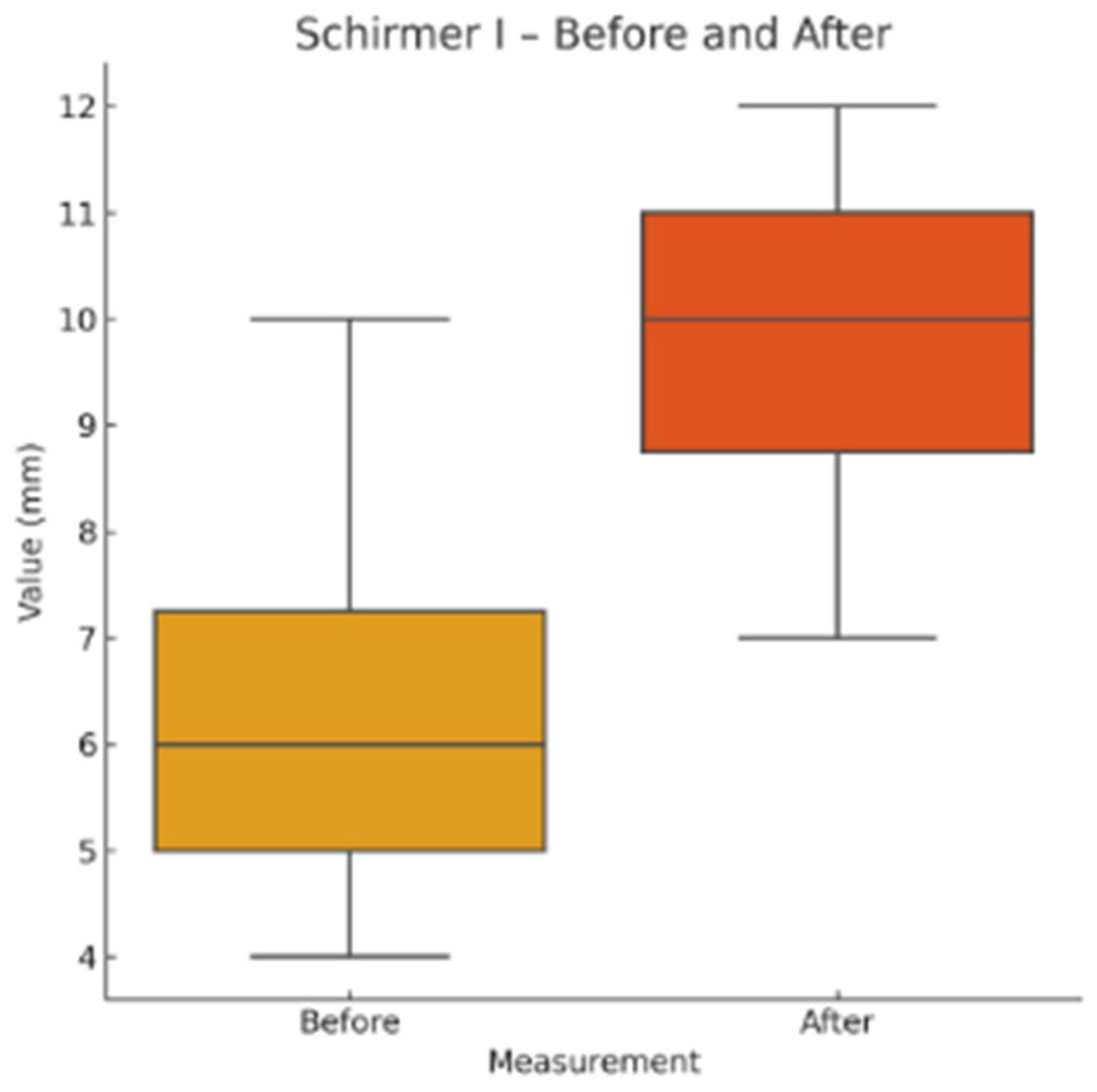

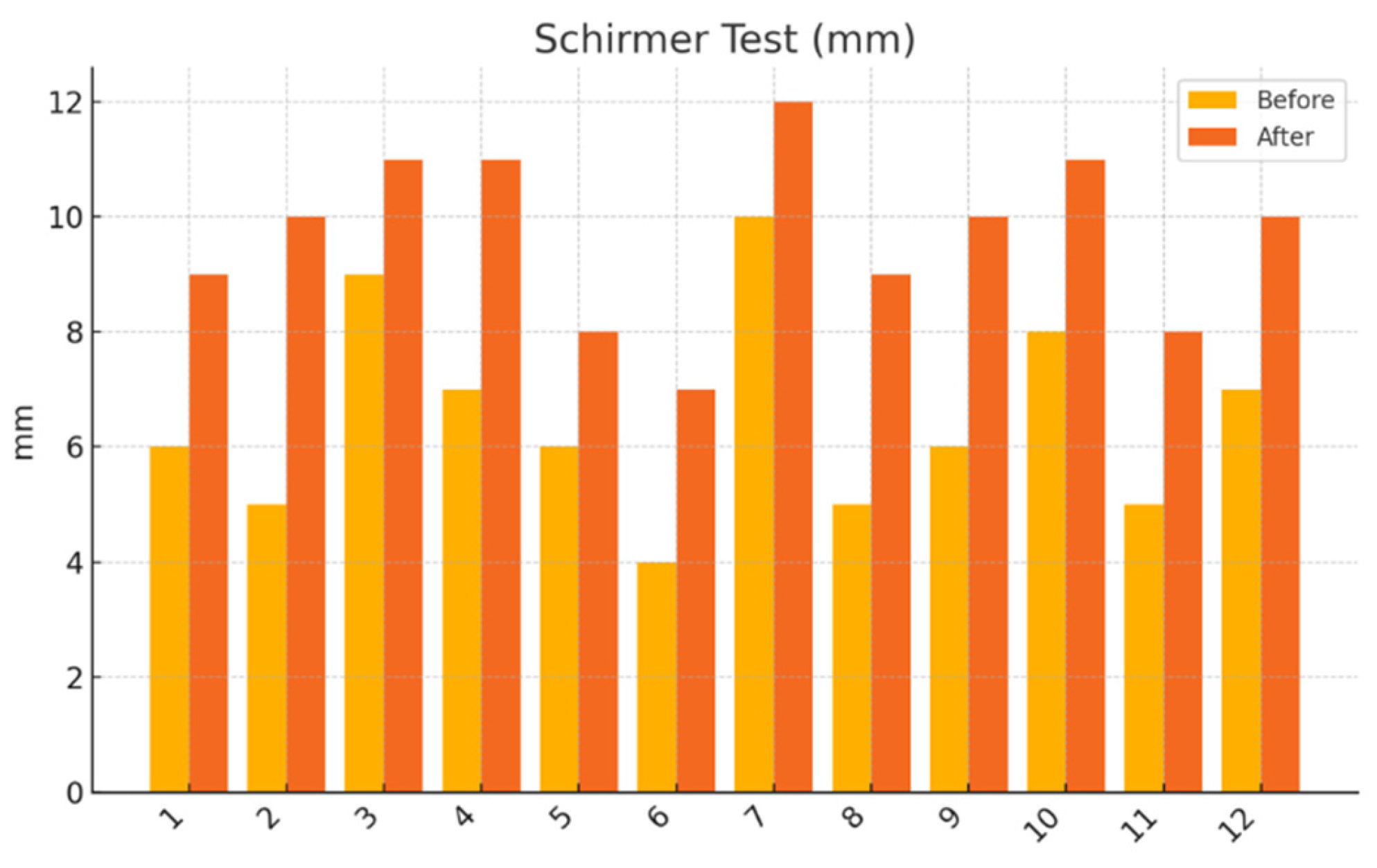

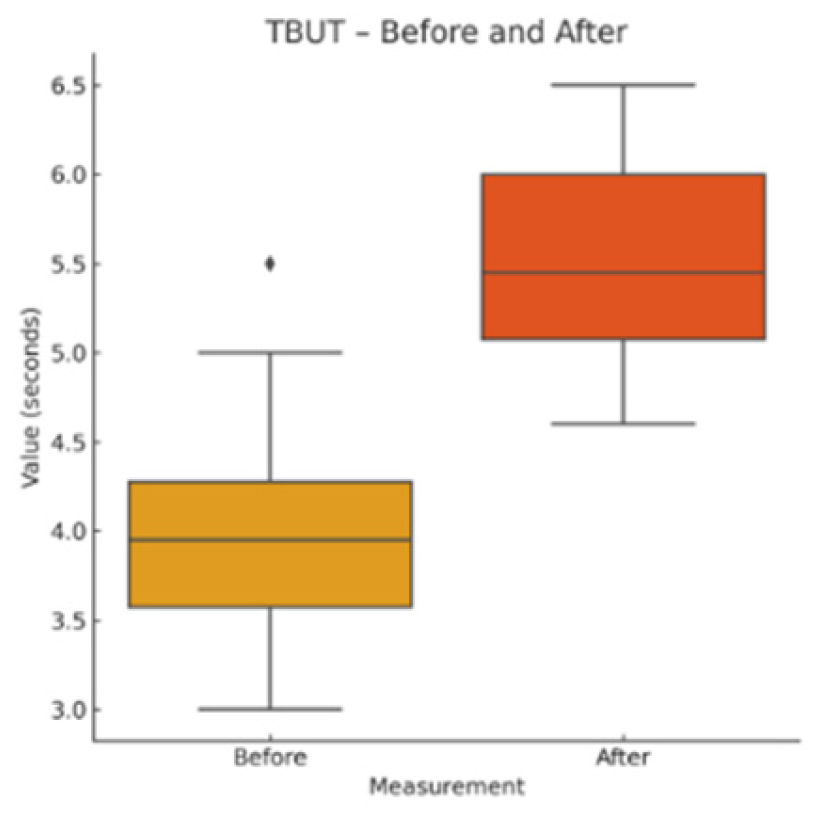

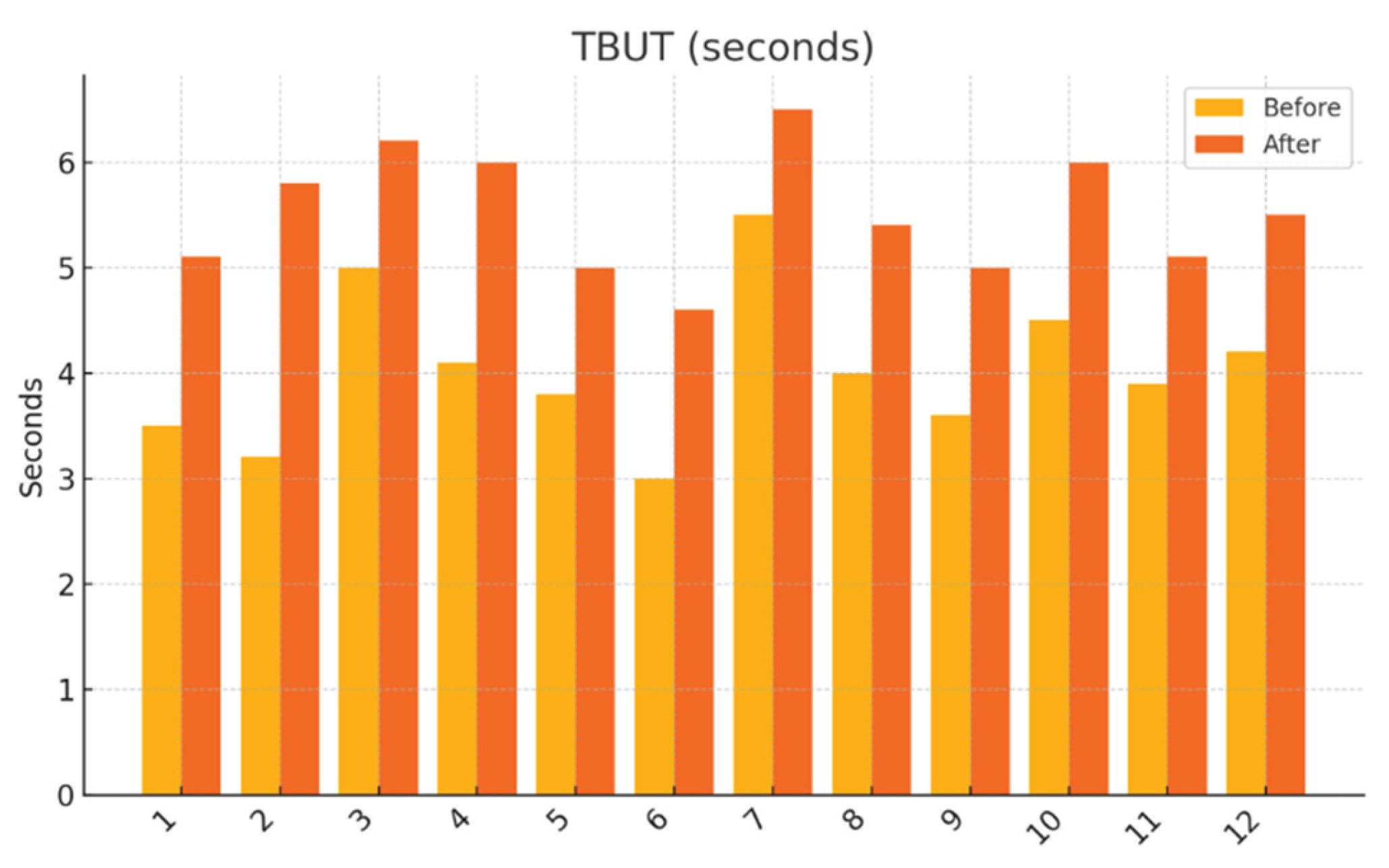

This pilot study represents the first clinical investigation, to our knowledge, assessing the therapeutic potential of oral melatonin supplementation in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) suffering from dry eye disease (DED). Over an 8-week intervention period, melatonin demonstrated significant and clinically relevant improvements across multiple objective and subjective outcome domains, including tear secretion (Schirmer I test), tear film stability (TBUT), ocular surface integrity (NEI staining score), and patient-reported symptom burden (OSDI, ESSPRI dryness). Additionally, a significant reduction in circulating interleukin-6 (IL-6) was observed, supporting a systemic anti-inflammatory effect.

DED is among the most frequent and debilitating manifestations of pSS, with a complex pathophysiology involving lacrimal gland dysfunction, epithelial barrier disruption, goblet cell loss, and persistent ocular surface inflammation [

1,

2,

3]. Despite the availability of topical lubricants, immunomodulators, and corticosteroids, therapeutic responses remain suboptimal, with many patients reporting continued discomfort, visual disturbance, and impaired quality of life [

4,

16,

17]. Therefore, there is an unmet need for safe, affordable, and biologically targeted adjunctive treatments.

Melatonin, classically known for its role in circadian rhythm regulation, has emerged as a multifunctional molecule with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties [

5,

6]. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that melatonin modulates innate and adaptive immune responses by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, IL-17), inhibiting nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), and suppressing the NLRP3 inflammasome [

6,

7,

8]. Moreover, melatonin promotes regulatory T cell (Treg) activity and preserves epithelial integrity, particularly in mucosal and exocrine tissues. In models of DED, melatonin has been shown to enhance lacrimal secretion, increase goblet cell density, and reduce ocular surface inflammation through decreased expression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) [

9,

10,

11].

Our results extend these findings to a clinical setting. The improvement in Schirmer and TBUT values suggests that melatonin may enhance both tear volume and film stability—likely through its cytoprotective effects on lacrimal epithelial cells and its capacity to preserve ocular surface homeostasis. The significant reduction in NEI corneal staining further supports the hypothesis that melatonin reinforces epithelial barrier function and reduces desiccation-induced damage.

Notably, the observed reduction in serum IL-6 aligns with melatonin’s established anti-inflammatory mechanisms. IL-6 plays a central role in the pathogenesis of pSS, where it contributes to B-cell hyperactivity, autoantibody production, epithelial cell apoptosis, and inhibition of tissue regeneration [

12,

13,

14]. The fact that IL-6 decreased significantly, while other systemic markers (TNF-α, CRP, ESR, immunoglobulins) remained stable, suggests that melatonin acts selectively, modulating pathogenic cytokine circuits without inducing global immunosuppression. This profile is particularly desirable in autoimmune diseases, where broad immunosuppression can carry substantial risks.

However, the absence of significant changes in TNF-α, CRP, and ESR may be explained by several factors. First, systemic cytokine levels are subject to diurnal and inter-individual variability [

17]. Second, our relatively short study duration and modest baseline inflammatory burden may have limited the ability to detect broader immunologic shifts. Third, melatonin may exert more pronounced effects at local tissue sites—such as the ocular surface—rather than in systemic circulation. These observations are consistent with melatonin’s reported action at mucosal-epithelial interfaces, where it modulates barrier immunity and dampens localized inflammatory signaling [

18].

Interestingly, the improvement in patient-reported symptoms (OSDI and ESSPRI dryness scores) exceeded the magnitude of change in systemic biomarkers. This discrepancy suggests that melatonin’s benefits may extend beyond traditional immunological endpoints. In addition to its anti-inflammatory effects, melatonin influences neurosensory pathways, sleep regulation, and central pain processing—all of which are relevant in pSS, a disease often associated with fatigue, depression, and sleep disturbances [

6,

19]. Although these dimensions were not specifically measured in our study, their potential contribution to the observed symptom improvement should be explored in future research.

The safety profile observed in this study is consistent with prior data. All participants tolerated the supplement well, with no adverse events reported. [

11]. Melatonin has previously demonstrated good tolerability in both short- and long-term use across a range of autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders, including multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis [

20]. Given its low cost, ease of administration, and wide accessibility, melatonin may serve as a particularly attractive adjunctive treatment in the long-term management of autoimmune DED [

15].

That said, our study has several limitations. First, the small sample size and lack of a placebo control group limit the generalizability and strength of causal inference. Second, the open-label design introduces potential bias, especially in subjective outcomes. Third, while compliance was monitored via intake diaries, biochemical verification was not performed. Finally, the absence of tear cytokine analysis, ocular surface impression cytology, or lacrimal gland imaging limits mechanistic interpretation.

To build on these findings, future studies should incorporate randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled designs with larger cohorts and extended follow-up periods. Detailed mechanistic investigations—including tear proteomics, impression cytology, and gene expression profiling of conjunctival or lacrimal tissues—are warranted to better understand melatonin’s local immunopharmacology. Additionally, the potential of topical melatonin formulations (e.g., eye drops or gels) should be explored as a targeted therapeutic alternative that may maximize ocular benefits while minimizing systemic exposure. Quality-of-life measures, sleep quality, fatigue scales, and neurocognitive assessments should also be integrated to capture the full spectrum of melatonin’s impact in this patient population