1. Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, multisystemic autoimmune disorder characterized by widespread inflammation and tissue damage. It exerts a deleterious effect on connective tissue and affects numerous organ systems, including the visual system, leading to distinct ophthalmologic manifestations [

1,

2].

In addition to systemic symptoms such as fever, arthralgia, fatigue, and general malaise, the clinical presentation encompasses a highly variable combination of dermatologic, renal, musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, and hematologic abnormalities. Less frequently, cardiovascular, pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and ophthalmic complications may also arise. The symptomatology demonstrates high interindividual variability and may fluctuate in intensity over time in the same patient, resulting in a heterogeneous clinical course that ranges from indolent progression to fulminant systemic involvement.

The etiology of SLE remains incompletely elucidated; however, it is believed to result from a complex interplay of genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and immune dysregulation. This interaction promotes multiorgan dysfunction, contributing significantly to both morbidity and mortality. The systemic nature of SLE necessitates a holistic diagnostic and therapeutic approach, rather than an organ-specific focus. Damage to internal organs results in a broad spectrum of functional impairments, which adversely affect overall health status and contribute to a marked decline in health-related quality of life [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9].

SLE occurs worldwide and exhibits a marked female predominance, with women accounting for 85–93% of cases. The median age of onset typically ranges from adolescence to early middle age. In females, disease incidence peaks between the third and fifth decades of life, whereas in males it occurs later, most commonly between the ages of 50 and 70. This sex-based difference in epidemiology is believed to be influenced by hormonal factors, particularly estrogen. Prevalence among women increases sharply at puberty and declines post menopause, while in men, the incidence increases gradually with age. The overall reported prevalence of SLE ranges from 20 to 150 cases per 100,000 individuals, with an annual incidence of 0.3–3.8 per 100,000 [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

According to recent evidence, approximately 30% of SLE patients develop ophthalmic symptoms. These are frequently mild and self-limiting but may, in some instances, evolve into severe, sight-threatening complications. Ocular involvement typically reflects systemic disease activity and may precede or predict the involvement of other critical organ systems such as the cardiovascular, pulmonary, or renal systems [

16,

17].

Ocular manifestations may affect virtually any component of the eye, including the protective adnexa (eyelids), orbit, lacrimal apparatus, and intraocular structures such as the iris, ciliary body, vitreous body, retina, and optic nerve. The most reported condition is keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), or dry eye disease (DED), affecting 25–35% of patients.

The primary objective of this study was to assess the impact of dry eye symptoms on vision-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, using the validated Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire. Additional aims included evaluating correlations between OSDI scores and clinical ophthalmologic findings, as well as determining the prevalence of disorders affecting specific ocular structures in this patient population. [

18,

19]

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

Patients diagnosed and treated at the Department of Internal Diseases, Rheumatology and Clinical Immunology of the Upper Silesian Medical Center in Katowice, Poland, who had a confirmed diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) based on American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria, underwent both basic and extended ophthalmological examinations. These examinations were conducted in the Cornea Unit of the Ophthalmology Department of the University Clinical Center, Prof. K. Gibiński in Katowice.

The study included 35 patients (70 eyes), consisting of 33 women and 2 men. Their ages ranged from 24 to 65 years, with a mean age of 46 (SD = 10.75). A retrospective analysis of the collected data was performed. Ophthalmological examinations were carried out in these patients suffering from SLE from June 2016 to December 2021.

2.2. Ethical Approval

The study was approved by Bioethical Commitee of Medical University of Silesia.

2.3. Ophthalmological Examination Procedures

Standard tests were performed in accordance with tenets and guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. From June 2016 to December 2021, ophthalmological examinations were carried out in patients suffering from systemic lupus erythematosus.

The analyzed group included 35 patients (70 eyes), including 33 women and 2 men aged 24 to 65 (M = 46, SD = 10.75). A retrospective analysis of the obtained results was carried out.

Each of the examined patients underwent a thorough ophthalmological analysis, which included:

Distant and near visual acuity test on Snellen charts with the best spectacle correction (BCDVA and BCNVA) in the same light conditions

Evaluation of the anterior and posterior segment of the eyeball in a slit biomicroscope (Haag-Streit, Switzerland) with a 90D lens (Haag-Streit, Switzerland)

Examination of retina using Optical Coherence Tomography (Zeiss, Germany)

Evaluation of the eyeball using an ultrasonographic device (ultrasound of the eye with a 10MHz probe).

Evaluation of the refractive error with the RM-8100 autorefractometer (Topcon, Japan)

Intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement with Goldmann applanation tonometer (Haag-Streit, Switzerland)

Evaluation of tear film stability using the Tear Film Break-Up Time Test (T-BUT).

Fluorescein staining test and anterior segment assessment using both the Oxford and Bijsterveld scale

Evaluation of tear secretion using the Schirmer test I without anesthesia

Evaluation of ocular surface dysfunction parameters using Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire

2.4. Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) Questionnaire

The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire [

43,

44,

45] was employed to quantitatively assess the impact of dry eye symptoms on vision-related quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. This validated, disease-specific tool comprises 12 items subdivided into three domains: (1) ocular discomfort, capturing symptoms such as eye pain or irritation; (2) visual function, evaluating limitations in performing routine visual tasks, including reading, driving, or computer use; and (3) environmental triggers, assessing the exacerbating effects of external factors such as wind, air conditioning, or smoke on dry eye symptoms.

Participants were instructed to respond based on a 7-day recall period, rating the frequency of symptoms using a 5-point Likert scale: "none of the time", "some of the time", "half of the time", "most of the time", or "all of the time."

The overall OSDI score was computed using the standardized formula:

Subscale scores for each domain were derived using the same formula, applied separately to the specific questions related to that subscale. Thus, both overall and domain-specific scores ranged from 0 to 100, where higher values indicated more severe symptoms and greater functional impairment.

Scoring interpretation was performed in accordance with established guidelines, classifying symptom severity as follows:

0–12: Normal

13–22: Mild DED

23–32: Moderate DED

33–100: Severe DED

This instrument was selected for its widespread clinical use, high sensitivity in detecting dry eye symptoms, and robust psychometric properties.

2.5. Tear Film Break-Up Time (T-BUT) Test

The tear film break-up time (T-BUT) test was performed to assess the stability of the pre-corneal tear film, serving as an indicator of ocular surface health and tear film integrity. A single drop of 2% sodium fluorescein solution was instilled into the lower conjunctival fornix of each patient. Using slit-lamp biomicroscopy equipped with a cobalt blue filter, the time interval between a complete blink and the appearance of the first dry spot or discontinuity in the tear film was recorded.

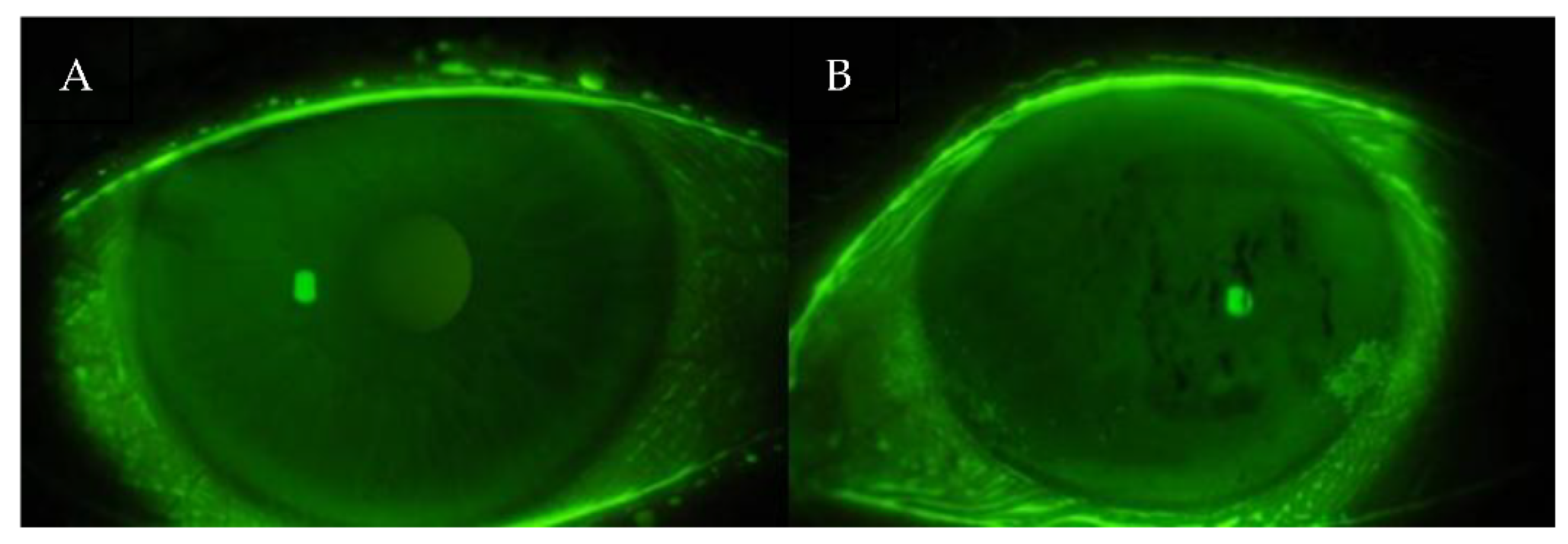

This moment is visualized as dark lines or spots appearing on the otherwise uniform greenish-yellow fluorescein background (

Figure 1). The test was repeated three times per eye, and the mean value was used for analysis to minimize intra-examiner variability.

The following interpretation criteria were applied in accordance with current ophthalmologic standards [

46]:

T-BUT >10 seconds was considered normal tear film stability;

T-BUT <10 seconds indicated decreased tear film stability, often associated with lipid layer dysfunction;

T-BUT <5 seconds was interpreted as indicative of significant ocular surface lubrication deficiency and marked tear film instability, typically resulting from meibomian gland dysfunction or lipid layer insufficiency.

This test is non-invasive, reproducible, and widely used in both clinical and research settings to diagnose dry eye disease (DED) and assess treatment efficacy.

2.6. Schirmer I Test

A conventional Schirmer I test without topical anesthesia was performed to evaluate the basal and reflex secretion of the aqueous component of the tear film. The test involved the placement of a standardized filter paper strip (Whatman no. 41) folded at the notch and inserted into the lateral third of the lower conjunctival fornix. The patients were instructed to gently close their eyelids during the 5-minute test duration.

After the elapsed time, the extent of wetting on the strip was measured in millimeters from the fold. This value reflects the secretory function of the lacrimal glands.

Interpretation of results was based on established clinical criteria [

47]

Wetting >15 mm: Normal aqueous tear secretion

Wetting of 10–15 mm: Early or borderline aqueous deficiency

Wetting of 5–10 mm: Moderate aqueous tear deficiency, suggestive of evolving dry eye

Wetting <5 mm: Severe aqueous-deficient dry eye, indicating advanced lacrimal hyposecretion and significant tear film insufficiency

This test provides a quantitative assessment of tear production and is particularly useful in diagnosing aqueous-deficient dry eye subtypes, such as those associated with Sjögren’s syndrome or systemic autoimmune diseases like SLE.

2.7. Ocular Surface Staining Assessment

Assessment of ocular surface damage was conducted using vital dye staining techniques, specifically rose Bengal and fluorescein dyes, which are widely accepted in the evaluation of dry eye disease (DED).

To assess conjunctival damage, a rose Bengal-impregnated strip was gently applied to the inferotemporal bulbar conjunctiva. The resulting staining pattern was evaluated using the van Bijsterveld scoring system, which assesses three ocular surface zones: the nasal and temporal conjunctiva and the cornea. Each zone is scored from 0 to 3, with a maximum possible score of 9. Higher scores indicate more extensive epithelial damage and greater severity of ocular surface disease.

Corneal epithelial damage was further graded using the Oxford grading scheme, a standardized tool for quantifying fluorescein staining of the corneal and conjunctival epithelium. This semi-quantitative scale classifies staining into six categories, ranging from grade 0 (no staining) to grade 5 (severe punctate epithelial damage). Evaluation was based on a reference chart comprising panels A through E, where staining is illustrated with colored dots. The intensity and extent of staining in patient eyes were compared directly to the reference images.

In this system, each panel represents a progressive increase in staining intensity: staining increases by approximately one logarithmic unit between panels A and B and by 0.5 logarithmic units between panels B through E.

Following dye instillation, ocular surface staining was examined under a slit-lamp biomicroscope (Haag-Streit) at standardized settings (×16 magnification) and with appropriate light filters to optimize visualization.

2.8. Diagnostic Criteria for Dry Eye Disease

In this study, abnormal values in ocular surface tests were defined as follows:

Schirmer I test: ≤5 mm wetting after 5 minutes

Tear Break-Up Time (T-BUT): <10 seconds

van Bijsterveld score: >3

A diagnosis of dry eye disease (DED) was established when at least two of the above parameters met these defined abnormality criteria, in accordance with previously validated diagnostic protocols in autoimmune populations [

40,

48].

This multimodal assessment approach enabled a comprehensive evaluation of tear quantity, tear film stability, and epithelial integrity, providing reliable criteria for the diagnosis of DED in systemic lupus erythematosus patients.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using validated statistical software. A significance level of α = 0.05 was adopted for all statistical tests. Where appropriate, adjustments for multiple comparisons were applied using the Bonferroni correction or its non-parametric equivalents. The distribution of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test to determine the assumption of normality. Homogeneity of variances was evaluated with Levene’s test.

In cases where the data met the assumptions of parametric testing, statistical comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Bonferroni post hoc testing when applicable. For comparisons between two groups, the independent samples Student’s t-test was applied.

When assumptions for parametric analysis were not met, non-parametric alternatives were used: the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s post hoc correction for multiple group comparisons, and the Mann-Whitney U test for two-group comparisons.

The strength and direction of linear associations between continuous variables were evaluated using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) for normally distributed data or Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (rho) for non-normally distributed variables.

Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared (χ²) test of independence. In cases where expected cell counts were below 5, the Fisher’s exact test was used instead.

Results were presented with corresponding p-values and confidence intervals where applicable.

3. Results

The study group consisted of 35 patients diagnosed with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), including 33 women (94.3%) and 2 men (5.7%). The mean age was 51 years, with a range from 22 to 77 years.

Based on the diagnostic criteria established in this study, dry eye disease (DED) was confirmed in 13 patients (37.1%), while 22 patients (62.9%) did not meet the criteria for DED, constituting the non-DED subgroup.

Additional ophthalmological abnormalities identified in the cohort included:

Lens opacification in 8 patients (22.9%)

Hyaloid degeneration in 12 patients (34.3%)

Retinal degenerations, including dry (atrophic) changes in 4 patients (11.4%) and wet (exudative) changes in 1 patient (2.9%)

Hypertensive or microangiopathic retinal angiopathy in 8 patients (22.9%)

Episcleritis in 1 patient (2.9%)

These findings are summarized in

Table 1.

Among the 35 patients, refractive errors were common, with astigmatism >0.50 diopters (D cyl) identified in 21 patients (60.0%). Notably, patients diagnosed with DED demonstrated significantly higher degrees of astigmatism.

Furthermore, 22 patients (62.8%) reported subjective symptoms suggestive of ocular surface dysfunction, including sensations of itching, burning, foreign body presence, dryness, and ocular redness.

These symptoms were more prevalent in the DED group, supporting the correlation between clinical signs and patient-reported symptoms.

Table 2 presents a comparative analysis of the study population, stratified into two groups: patients diagnosed with dry eye disease (DED) and those without DED, based on clinical examination and OSDI scores—both total and subscale-specific.

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups regarding demographic variables. The mean age did not differ significantly between DED and non-DED patients (p = 0.111), and no association with sex distribution was observed (p = 0.600).

The best-corrected distance visual acuity (BCDVA) measured using Snellen decimal scale was on average 0.896 and 0.905 for the right and left eye, respectively, for all patients studied (n=35). In isolated cases (4.3%), BCDVA was less than 0.5. There were no statistically significant differences in BCDVA between individual groups of patients (p=0.700).

The median of the best corrected near visual acuity (BCNVA) was in Snellen scale 0.50 (SD=0.26) for both the right and left eye in all examined patients (n=35). No statistically significant differences were noted in BCNVA between individual patient groups (p=0.76).

The mean intraocular pressure (IOP) was 16.4 mmHg (right eye) and 16.1 mmHg (left eye), with no statistically significant differences found between the DED and non-DED groups (p = 0.520).

In contrast, statistically significant differences were observed in the diagnostic tests assessing the quantity and stability of the tear film.

Patients with DED exhibited significantly lower values in Schirmer I test (p = 0.0003)

And significantly reduced tear break-up time (T-BUT) (p = 0.0002), compared to non-DED counterparts.

These findings confirm impaired tear production and instability of the tear film in DED patients, reflecting greater anterior segment pathology.

In addition, ocular surface staining assessments revealed notable abnormalities in the DED group:

van Bijsterveld scores were significantly higher among DED patients (p = 0.0000),

While the Oxford grading scale demonstrated a trend toward statistical significance (p = 0.080), indicating a possible association.

These results underscore the relevance of ocular surface staining techniques in identifying subclinical inflammation and epithelial damage in SLE patients with DED.

Based on these findings, topical therapeutic intervention with lubricants and/or anti-inflammatory agents appears warranted in most DED cases, aiming to restore ocular surface integrity and improve quality of life.

The following mean test values were recorded across the entire cohort:

Schirmer I Test: 10.5 mm (SD = 4.17)

Tear Break-Up Time (T-BUT): 8.5 seconds (range: 6.5–11.5 s)

van Bijsterveld score: Median of 3 (range: 1–4)

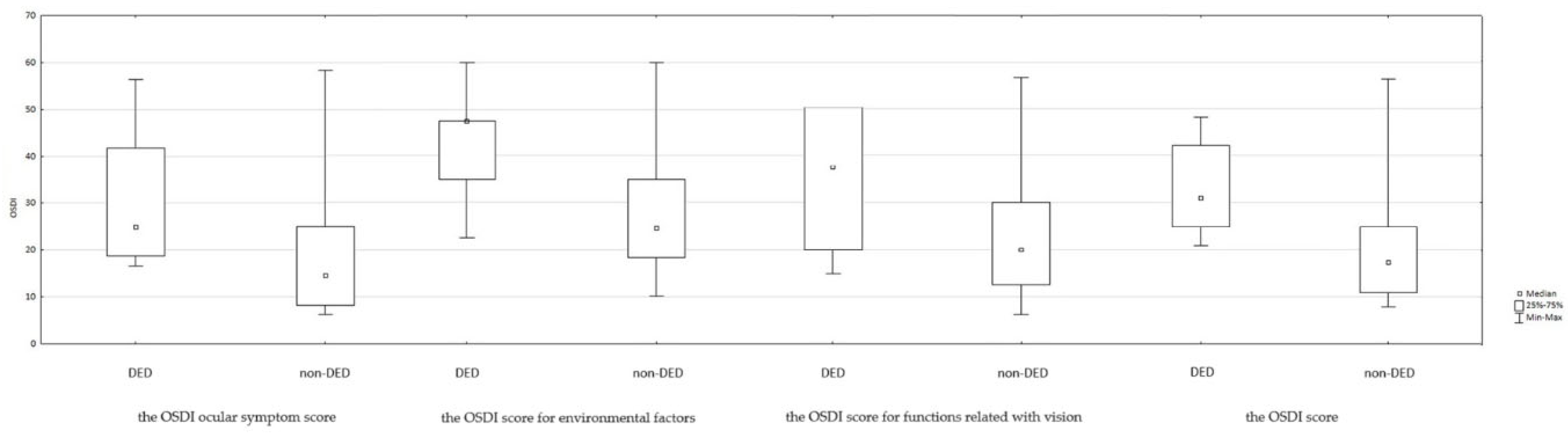

The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) total and subscale scores are summarized in

Table 2 and

Figure 2. Statistically significant differences were observed between the DED and non-DED groups for the overall OSDI score as well as each subscale, indicating a greater subjective burden of disease among DED patients.

Specifically, 18 patients (51.4%) scored >22 points in the OSDI questionnaire, suggesting moderate to severe ocular surface dysfunction. Most of these patients (61.1%) belonged to the DED group. Detailed group-wise OSDI results are shown in

Table 3.

Correlation analyses between OSDI (total and subscale scores) and objective clinical parameters—T-BUT, Schirmer I, and ocular surface staining scores (van Bijsterveld and Oxford)—are presented in

Table 4.

Statistically significant and clinically meaningful correlations were observed in nearly all comparisons, confirming strong associations between subjective symptom severity and objective diagnostic test results.

In this study, statistically significant correlations were identified between the total OSDI score and the results of the T-BUT test, Schirmer I test, and ocular surface staining scores using both the van Bijsterveld and Oxford grading systems.

The relationships between ocular surface dysfunction parameters and tear secretion measures with the OSDI total and subscale scores were predominantly moderate in strength and reached statistical significance in most instances. These correlations confirm the clinical relevance of combining subjective symptom evaluation with objective diagnostic testing.

The results collectively underscore the negative impact of ocular surface abnormalities on visual function and daily activities of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Specifically, patients with poorer tear film stability and reduced aqueous secretion reported significantly greater limitations in activities involving reading, screen use, and exposure to environmental triggers.

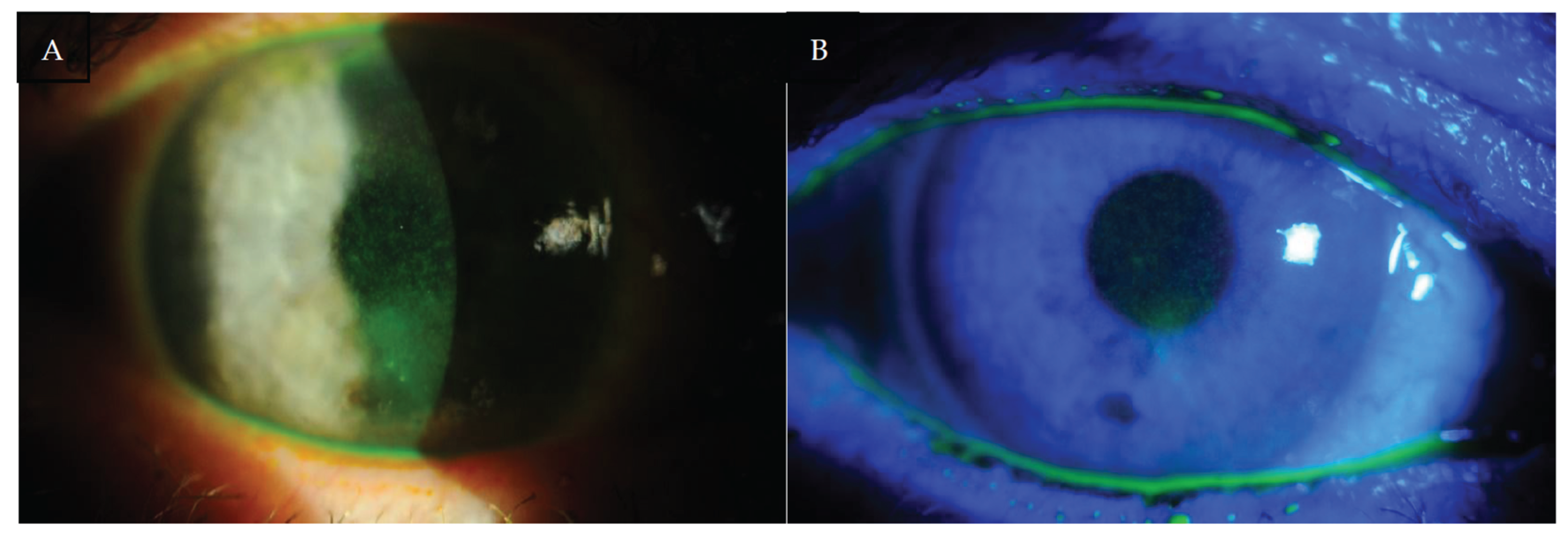

According to the statistical analysis, ocular surface damage had the most pronounced effect on the OSDI subscale related to visual symptoms, reflecting discomfort and degradation in the quality of vision during everyday tasks (see

Figure 3).

These findings highlight the multidimensional burden of dry eye disease in SLE and provide evidence for the importance of routine ophthalmological evaluation and early therapeutic intervention in this patient population.

4. Discussion

Dry eye syndrome, also known as dry eye disease (DED) or keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS), is one of the most frequent causes of ophthalmologic consultations in the general population. According to the Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop II (TFOS DEWS II), DED is defined as:

"A multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles." [

20]

This definition underscores the complex pathophysiology of DED, involving both structural and neuroimmunological components.

The prevalence of DED in this study was 37.1%, aligning with previously reported rates ranging from 15% to 35% [

21,

22,

23,

24]. In our cohort, 22 out of 35 patients (62.8%) reported dry eye symptoms, most commonly itching, burning, foreign body sensation, dryness, and redness of the conjunctiva. This is consistent with the literature, where 18–60% of SLE patients present with similar ocular complaints [

25].

The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) is a well-validated instrument designed to evaluate the frequency and severity of dry eye symptoms and their impact on daily activities and work productivity. Although systemic disease may affect overall quality of life, the OSDI remains relatively specific to ocular surface symptoms. It has proven valuable in discriminating between healthy individuals and those with varying severity of DED and is widely used in both clinical trials and epidemiological research [

26]. In this study, higher OSDI scores were clearly associated with objective indicators of ocular surface damage, reinforcing its utility in SLE-related DED assessment.

In the study by Jensen et al., 60% of SLE patients (n=20) reported at least one symptom of DED, including mild irritation, foreign body sensation, grittiness, conjunctival redness, and dryness [

27]. These symptoms are consistent with the subjective complaints recorded in our study. Furthermore, a subset of patients with SLE and DED develop secondary Sjögren’s syndrome (sSS). Manoussakis et al. identified sSS in 9.2% of a cohort of 283 SLE patients, highlighting the need to consider overlapping autoimmune syndromes when assessing ocular surface pathology [

21].

It has been shown in the medical literature that patients with SLE have an increased incidence and rate of developing acute conjunctivitis, which is a disease most often caused by a bacterial or viral infection of the conjunctiva. It also seems to be related to DED due to the generalized impairment of the body's immune responses in patients with SLE [

22].

The pathogenesis of KCS in SLE is believed to involve fibrosis of the conjunctiva and lacrimal glands, leading to aqueous tear deficiency and secondary ocular surface damage [

28,

29]. Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators, including IL-17, have been identified in the tear film of affected individuals. These are the same markers present in autoimmune diseases that cause inflammation process leading to scarring such as Steven Johnson's syndrome [

30,

31].

Clinical signs of ocular surface damage in SLE may include symblepharon formation and exposure keratopathy. Histopathological examination of conjunctival biopsy specimens often reveals goblet cell loss, epithelial keratinization, mononuclear cell infiltration, and granuloma formation. Immunopathologic findings include immune complex deposition along the epithelial basement membrane, along with increased infiltration by CD4⁺ and CD8⁺ T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, and macrophages [

32,

33]. Although DED rarely leads to complete visual loss, its chronic course and recurrent symptoms significantly impair visual function and reduce patient well-being in daily and social activities [

34,

35].

Moreover, DED exerts a profound impact on multiple dimensions of patients’ quality of life (QoL), including physical, social, emotional, and occupational domains [

36,

37]. Emerging evidence suggests that DED may be conceptualized as a chronic pain syndrome, wherein persistent ocular discomfort contributes to psychological burden and functional disability [

35,

37,

38].

A notable limitation of this study is that the analyzed patient population consisted of individuals receiving chronic immunosuppressive therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus, including glucocorticosteroids and antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine (HCQ). Yavuz et al. have shown that HCQ may contribute to ocular surface damage in patients with autoimmune disorders [

39]. Thus, the potential iatrogenic effects of long-term systemic therapies must be considered when interpreting the prevalence and severity of DED in this population.

In a study by Wang et al. (2019), parameters such as T-BUT, tear meniscus height, and OSDI score were found to correlate significantly, albeit weakly, with SLE activity [

25]. Similarly, Bartlett et al. reported that the strength of correlations between DED diagnostic tests and subjective symptoms typically ranged from –0.4 to 0.4, indicating low to moderate concordance [

26]. However, in the present study, we observed stronger correlations between subjective (OSDI) and objective (Schirmer I, T-BUT, Bijsterveld, and Oxford) indicators, suggesting a more direct relationship between clinical signs and symptomatology in this SLE population.

The diagnostic approach in this study was based on three primary clinical tools: T-BUT, Schirmer I, and the van Bijsterveld scoring system-all widely accepted in the ophthalmologic assessment of DED [

40,

41]. Nonetheless, there is growing recognition that additional diagnostic methods, such as tear film osmolarity testing, may offer enhanced sensitivity and specificity. Jacobi et al. demonstrated that osmolarity measurement is among the most sensitive markers of tear film dysfunction [

42]. Future research should incorporate these objective modalities to refine DED diagnostics in autoimmune populations.

Given the close association between ocular surface impairment and functional limitations, the primary therapeutic goal in managing DED should be the improvement of patient quality of life, beyond the mere correction of clinical signs. This patient-centered approach underscores the broader significance of DED-both individually and societally.

There is a clear need to enhance public awareness regarding the prevalence and consequences of dry eye, particularly in individuals with chronic autoimmune conditions. Educational campaigns and interdisciplinary care models may facilitate earlier recognition and timely intervention.

Ophthalmologists and other healthcare providers should maintain a high index of suspicion for DED in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases such as SLE and proactively assess its impact on visual function and daily living, integrating both subjective and objective evaluation tools in clinical practice.

5. Conclusions

Dry eye disease (DED) is a prevalent and increasingly recognized condition that leads to a multifactorial decline in visual performance and quality of life (QoL). This study summarizes the burden of DED in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), with a specific focus on its functional impact on daily visual tasks and patient-reported outcomes.

The findings are consistent with prior research, demonstrating that DED significantly affects multiple dimensions of QoL, particularly the ability to engage in visually demanding activities, such as reading and driving, as well as workplace productivity, especially when screen exposure is prolonged. These effects may translate into broader socioeconomic consequences, emphasizing the public health relevance of recognizing and managing DED effectively.

In our study, patients with SLE and DED showed statistically significantly lower vision-related quality of life, as reflected by elevated scores in the Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) questionnaire, compared to those without DED. Furthermore, the OSDI scores observed in this cohort aligned with those reported in previous studies of SLE patients with moderate DED and were lower than those reported for patients with more severe forms of ocular surface disease, such as advanced Sjögren’s syndrome (both primary and secondary) or systemic sclerosis [

40,

49].

Our findings underscore the critical need for proactive screening and comprehensive management of DED in SLE patients to mitigate its substantial impact on their daily lives and overall well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: W.L. Formal analysis: W.L., A.A.-L. and A.S. Investigation: W.L. Resources: W.L. and E.M.-K. Data curation: W.L. and A.S. Writing—original draft preparation: W.L. Writing—review and editing: W.L., A.A.-L., A.S. and D.W.-P. Visualization: W.L., A.A.-L. and A.S. Supervision: E.M.-K. and D.W.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge dr Joanna Wasiak for help with the initial examination of patient.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ACR |

American College of Rheumatology |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| BCDVA |

Best-Corrected Distant Visual Acuity |

| BCNVA |

Best-Corrected Near Visual Acuity |

| DED |

Dry Eye Disease |

| HCQ |

Hydroxychloroquine |

| IOP |

Intraocular Pressure |

| KCS |

Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca |

| OSDI |

Ocular Surface Disease Index |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| SLE |

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

| T-BUT |

Tear Break-up Time |

| TFOS DEWS II |

Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society Dry Eye Workshop II |

References

- Shaikh MF, Jordan N, D'Cruz DP. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Med (Lond). 2017 Feb;17(1):78-83. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Narváez, J. Systemic lupus erythematosus 2020. Med Clin (Barc). 2020 Dec 11;155(11):494-501. English, Spanish. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dörner T, Furie R. Novel paradigms in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2019 Jun 8;393(10188):2344-2358. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiriakidou M, Ching CL. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jun 2;172(11):ITC81-ITC96. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanouriakis A, Tziolos N, Bertsias G, Boumpas DT. Update οn the diagnosis and management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jan;80(1):14-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesińska M, Saletra A. Quality of life in systemic lupus erythematosus and its measurement. Reumatologia. 2018;56(1):45-54. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aringer, M. Inflammatory markers in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Autoimmun. 2020 Jun;110:102374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gergianaki I, Bortoluzzi A, Bertsias G. Update on the epidemiology, risk factors, and disease outcomes of systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Apr;32(2):188-205. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu JL, Woo JMP, Parks CG, Costenbader KH, Jacobsen S, Bernatsky S. Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Risk: The Role of Environmental Factors. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2022 Nov;48(4):827-843. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber MRW, Drenkard C, Falasinnu T, Hoi A, Mak A, Kow NY, Svenungsson E, Peterson J, Clarke AE, Ramsey-Goldman R. Global epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021 Sep;17(9):515-532. Erratum in: Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021 Sep 1. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Stojan G, Petri M. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018 Mar;30(2):144-150. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ocampo-Piraquive V, Nieto-Aristizábal I, Cañas CA, Tobón GJ. Mortality in systemic lupus erythematosus: causes, predictors and interventions. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018 Dec;14(12):1043-1053. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo JMP, Parks CG, Jacobsen S, Costenbader KH, Bernatsky S. The role of environmental exposures and gene-environment interactions in the etiology of systemic lupus erythematous. J Intern Med. 2022 Jun;291(6):755-778. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karvonen-Gutierrez CA, Leis A. Impact of menopause on women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Maturitas. 2021 Dec;154:25-30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guéry, JC. Why Is Systemic Lupus Erythematosus More Common in Women? Joint Bone Spine. 2019 May;86(3):297-299. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luboń W, Luboń M, Kotyla P, Mrukwa-Kominek E. Understanding Ocular Findings and Manifestations of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Update Review of the Literature. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Oct 14;23(20):12264. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arevalo JF, Lowder CY, Muci-Mendoza R. Ocular manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002 Dec;13(6):404-10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen A, Stone DU, Kaufman CE, Hefner KS, Fram NR, Siatkowski RL, Huang AJW, Chodosh J, Rasmussen PT, Fife DA, Pezant N, Grundahl K, Radfar L, Lewis DM, Weisman MH, Venuturupalli S, Wallace DJ, Rhodus NL, Brennan MT, Montgomery CG, Lessard CJ, Scofield RH, Sivils KL. Reproducibility of Ocular Surface Staining in the Assessment of Sjögren Syndrome-Related Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca: Implications on Disease Classification. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2019 Jul;1(5):292-302. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Whitcher JP, Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Heidenreich AM, Kitagawa K, Zhang S, Hamann S, Larkin G, McNamara NA, Greenspan JS, Daniels TE; Sjögren's International Collaborative Clinical Alliance Research Groups. A simplified quantitative method for assessing keratoconjunctivitis sicca from the Sjögren's Syndrome International Registry. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010 Mar;149(3):405-15. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, Liu Z, Nelson JD, Nichols JJ, Tsubota K, Stapleton F. TFOS DEWS II Definition and Classification Report. Ocul Surf. 2017 Jul;15(3):276-283.

- M. N. Manoussakis, C. Georgopoulou, E. Zintzaras et al., “Sj¨ogren’s syndrome associated with systemic lupus erythe- matosus: clinical and laboratory profiles and comparison with primary sj¨ogren’s syndrome,” Arthritis and Rheumatism, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 882–891, 2004.

- Hsu, CS., Hsu, CW., Lu, MC. et al. Risks of ophthalmic disorders in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus – a secondary cohort analysis of population-based claims data.BMC Ophthalmol 20, 96 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Dias-Santos A, Tavares Ferreira J, Pinheiro S, Cunha JP, Alves M, Papoila AL, et al. Ocular involvement in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a paradigm shift based on the experience of a tertiary referral center. Lupus. 2020 Mar;29(3):283-289. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen A, Chen HT, Hwang YH, Chen YT, Hsiao CH, Chen HC. Severity of dry eye syndrome is related to anti-dsDNA autoantibody in systemic lupus erythematosus patients without secondary Sjogren syndrome: A cross-sectional analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jul;95(28):e4218. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, Zhengyu Gu, Rongfeng Liao, Zongwen Shuai, "Dry Eye Indexes Estimated by Keratograph 5M of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients without Secondary Sjögren’s Syndrome Correlate with Lupus Activity", Journal of Ophthalmology, vol. 2019, Article ID 8509089, 8 pages, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Bartlett, M. Keith, L. Sudharshan, and S. Snedecor, “Associations between signs and symptoms of dry eye disease: a systematic review,” Clinical Ophthalmology, vol. 9, pp. 1719–1730, 2015.

- Jensen JL, Bergem HO, Gilboe IM, Husby G, Axéll T. Oral and ocular sicca symptoms and findings are prevalent in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1999 Aug;28(7):317-22. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dammacco R, Procaccio P, Racanelli V, Vacca A, Dammacco F. Ocular Involvement in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: The Experience of Two Tertiary Referral Centers. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26(8):1154-1165. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu Z, Lu Q, Zhang A, Shuai ZW, Liao R. Analysis of Ocular Surface Characteristics and Incidence of Dry Eye Disease in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients Without Secondary Sjögren's Syndrome. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022 Mar 7;9:833995. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tankunakorn J, Sawatwarakul S, Vachiramon V, Chanprapaph K. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis-Like Lupus Erythematosus. J Clin Rheumatol. 2019 Aug;25(5):224-231. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker MG, Cresce ND, Ameri M, Martin AA, Patterson JW, Kimpel DL. Systemic lupus erythematosus presenting as Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Clin Rheumatol 2014;20(3): 167–71.

- Sullivan DA, Dana R, Sullivan RM, Krenzer KL, Sahin A, Arica B, Liu Y, Kam WR, Papas AS, Cermak JM. Meibomian Gland Dysfunction in Primary and Secondary Sjögren Syndrome. Ophthalmic Res. 2018;59(4):193-205. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao S, Xiao Y, Zhang S, Liu L, Chen K. Elevated Rheumatoid Factor Associates with Dry Eye in Patients with Common Autoimmune Diseases. J Inflamm Res. 2022 ;15:2789-2794. 3 May. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang L, Xie Y, Deng Y. Prevalence of dry eye in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021 Sep 29;11(9):e047081. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sayegh RR, Yu Y, Farrar JT, Kuklinski EJ, Shtein RM, Asbell PA, Maguire MG; Dry Eye Assessment and Management (DREAM) Study Research Group. Ocular Discomfort and Quality of Life Among Patients in the Dry Eye Assessment and Management Study. Cornea. 2021 Jul 1;40(7):869-876. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu M, Liu X, Han J, Shao T, Wang Y. Association Between Sleep Quality, Mood Status, and Ocular Surface Characteristics in Patients With Dry Eye Disease. Cornea. 2019 Mar;38(3):311-317. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo OD LW, Akpek E. The negative effects of dry eye disease on quality of life and visual function. Turk J Med Sci. 2020 Nov 3;50(SI-2):1611-1615. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gomes JAP, Santo RM. The impact of dry eye disease treatment on patient satisfaction and quality of life: A review. Ocul Surf. 2019 Jan;17(1):9-19. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yavuz S, Asfuroğlu E, Bicakcigil M, Toker E. Hydroxychloroquine improves dry eye symptoms of patients with primary Sjogren's syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2011 Aug;31(8):1045-9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de A F Gomes B, Santhiago MR, de Azevedo MN, Moraes HV Jr. Evaluation of dry eye signs and symptoms in patients with systemic sclerosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012 Jul;250(7):1051-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vehof J, Utheim TP, Bootsma H, Hammond CJ. Advances, limitations and future perspectives in the diagnosis and management of dry eye in Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020 Jul-Aug;38 Suppl 126(4):301-309. [PubMed]

- Jacobi C, Jacobi A, Kruse FE, Cursiefen C (2011) Tear film osmolarity measurements in dry eye disease using electricalimpe- dance technology. Cornea 30:1289–1292.

- Yu K, Bunya V, Maguire M, Asbell P, Ying GS; Dry Eye Assessment and Management Study Research Group. Systemic Conditions Associated with Severity of Dry Eye Signs and Symptoms in the Dry Eye Assessment and Management Study. Ophthalmology. 2021 Oct;128(10):1384-1392. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schiffman RM, Christianson MD, Jacobsen G, Hirsch JD, Reis BL. Reliability and validity of the Ocular Surface Disease Index. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000 May;118(5):615-21. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumura Y, Inomata T, Iwata N, Sung J, Fujimoto K, Fujio K, Midorikawa-Inomata A, Miura M, Akasaki Y, Murakami A. A Review of Dry Eye Questionnaires: Measuring Patient-Reported Outcomes and Health-Related Quality of Life. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 Aug 5;10(8):559. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ozulken K, Aksoy Aydemir G, Tekin K, Mumcuoğlu T. Correlation of Non-invasive Tear Break-Up Time with Tear Osmolarity and Other Invasive Tear Function Tests. Semin Ophthalmol. 2020 Jan 2;35(1):78-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brott NR, Ronquillo Y. Schirmer Test. 2022 . In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan–. 8 May. [PubMed]

- Bjordal O, Norheim KB, Rødahl E, Jonsson R, Omdal R. Primary Sjögren's syndrome and the eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 2020 Mar-Apr;65(2):119-132. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozikowska M, Luboń W, Kucharz EJ, Mrukwa-Kominek E. Ocular manifestations in patients with systemic sclerosis. Reumatologia. 2020;58(6):401-406. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).