1. Introduction

Chronic spontaneous urticaria (CSU) is characterized by the appearance of hives often accompanied by angioedema, lasting longer than six weeks, with an intense itching sensation and often consequently poor quality of life (QoL) [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In CSU patients sleep disorders and psychological disorders (depression, anxiety) are common. Their sleep disturbed sleep primarily involves difficulties in falling asleep, early awakening, and a feeling of fatigue, which disrupts daily activities and consequently leads to difficulties in the individual’s professional and social life.

When considering factors related to a person’s sleep (including patients with dermatoses), it is vital to highlight the role of melatonin, a hormone which plays a central role in the sleep cycle. Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is predominantly produced in the pineal gland, and enters the bloodstream and cerebrospinal fluid [

5,

6]. It initiates and maintains the sleep cycle, which is the basis for its using as a treatment for specific conditions. The process of melatonin synthesis is complex. It begins with the amino acid tryptophan, which (with the help of the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase) is transformed into 5-hydroxytryptophan, which is then converted into serotonin, which undergoes acetylation to N-acetylserotonin, which is then converted into melatonin [

5]. The hypothalamic suprachiasmatic paraventricular nuclei control the synthesis of melatonin in the pinealocytes of the pineal gland, and according to the circadian rhythm, melatonin is produced daily in synchronization with the light-dark cycle. Melatonin is a lipophilic molecule, and during the night, it easily diffuses into the cerebrospinal fluid of the central nervous system, as well as into the bloodstream (where it is mainly bound to albumin, about 70% of total melatonin), with a smaller portion found in an accessible form [

7]. In the liver, melatonin is metabolized into 6-hydroxymelatonin (by cytochrome P450) and conjugated into 6-sulfatoxymelatonin, which is subsequently excreted in the urine [

8]. For the measurement of melatonin, the values of 6-sulfatoxymelatonin created in the urine must reflect plasma melatonin levels (this is a less invasive method reliable for assessing pineal gland function and melatonin production). In addition to urine, melatonin can also be measured/excreted in saliva (as a free form that is not bound to albumin) [

8]. The concentration of salivary melatonin depends on the time of day it is measured, with values in saliva ranging from daytime levels (between 1-5 pg/mL) to nighttime levels (which range from 10-50 pg/mL) [

9].

In CSU pathogenesis, various factors may be involved and may trigger pathogenetic pathways, including autoimmune processes and autoantibodies (e.g., IgG, Toll-like receptors, neuropeptides, cytokines), infections, allergens, physical factors, stress, intestinal dysbiosis, vitamin D deficiency, and other triggers which, through various molecular pathways, may lead to mast cell degranulation [

4]. When mast cells are activated, this results in degranulation of their preformed granule contents by exocytosis, as well as the synthesis and secretion of lipid mediators and cytokines. In CSU, mast cell and basophil activation and degranulation are mediated by autoantibodies, including IgE targeting its high-affinity receptor (FcεRI), or IgG antibodies directed against the IgE/FcεRI complex. Additionally, in CSU patients, autoantigens (e.g., TPO, IL-4) induce B cells to produce IgE/IgG antibodies, which bind to the FcεRI-α of mast cells, basophils, and other target cells (at the Fc segment). Upon repeated contact with the same antigen, the antigen cross-links two or more IgE molecules bound to these cells. Other mechanisms also trigger mast cell degranulation; for instance, the combination of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) with IL-25 and IL-33 activates type 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), which release cytokines IL-5 and IL-13 that further promote mast cell degranulation. T cells and eosinophils are also important, engaging in complex bidirectional crosstalk with mast cells [

4]. Finally, mast cells release a wide array of mediators such as histamine, leukotriene C4 (LTC4), prostaglandin D2 (PGD2), proteases (e.g., chymase and tryptase), platelet-activating factor (PAF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-1, IL-2, IL-4, Il-6, IL -8 IL-13 , C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1/2 (CXCL1/2), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), serotonine and others that collectively contribute to the development of hives and angioedema. As a result, vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and firing of sensory nerves finally cause hives and itching, which are manifestations of CSU [

3]. (Kaplan A, 2023).

Wheal sites are therefore characterized by infiltration of mast cells, basophils, eosinophils, monocytes, T cells, and neutrophils, resembling a late-phase cutaneous reaction following allergen exposure, with a cytokine profile predominantly reflecting a Th2 response. This infiltrate also includes components of Th1 and Th17 inflammation, with their associated cytokines. In CSU, biopsies of lesional and non-lesional skin show infiltration of large numbers of IL-17A-expressing CD4+ T cells, often located near mast cells that also express IL-17A. In the stage of active CSU, increased cutaneous levels of inflammatory molecules such as C-reactive protein, IL-6, and prothrombin fragment 1+2 (reflecting coagulation enzyme turnover) are observed, while these levels decrease during remission. Also, CSU patient skin shows elevated expression of IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP compared to healthy controls [

3]. Chemokines derived from mast cells and activated endothelial cells promote the recruitment of immune cells (lymphocytes, eosinophils, basophils, and neutrophils) into the dense infiltrate at wheal sites. Mast cells and eosinophils act together in various immune responses, including those triggered by environmental allergens. These reactions typically begin with IgE-mediated mast cell activation, followed by eosinophil involvement. The recruitment of eosinophils from the bloodstream into the skin is mediated by chemokines such as eotaxins 1–3, monocyte chemoattractant proteins MCP-1, MCP-3, and MCP-4, RANTES (Regulated upon Activation, Normal T Cell Expressed and Presumably Secreted), and PGD2. Additionally, eosinophils express CRTh2, the receptor for PGD2 (secreted by mast cells and monocytes), which participates in the eosinophil recruitment to the site of hives and represents a potential therapeutic target.

Melatonin is crucial in various physiological activities (regulating circadian rhythms, immune responses, oxidative processes, apoptosis, or mitochondrial homeostasis), which most commonly change during inflammatory processes [

10]. In addition to its role as a sleep hormone, melatonin is also one of the most potent natural antioxidants, which, in addition to its direct action on free radicals, also affects the intracellular antioxidant enzyme system [

5,

6].

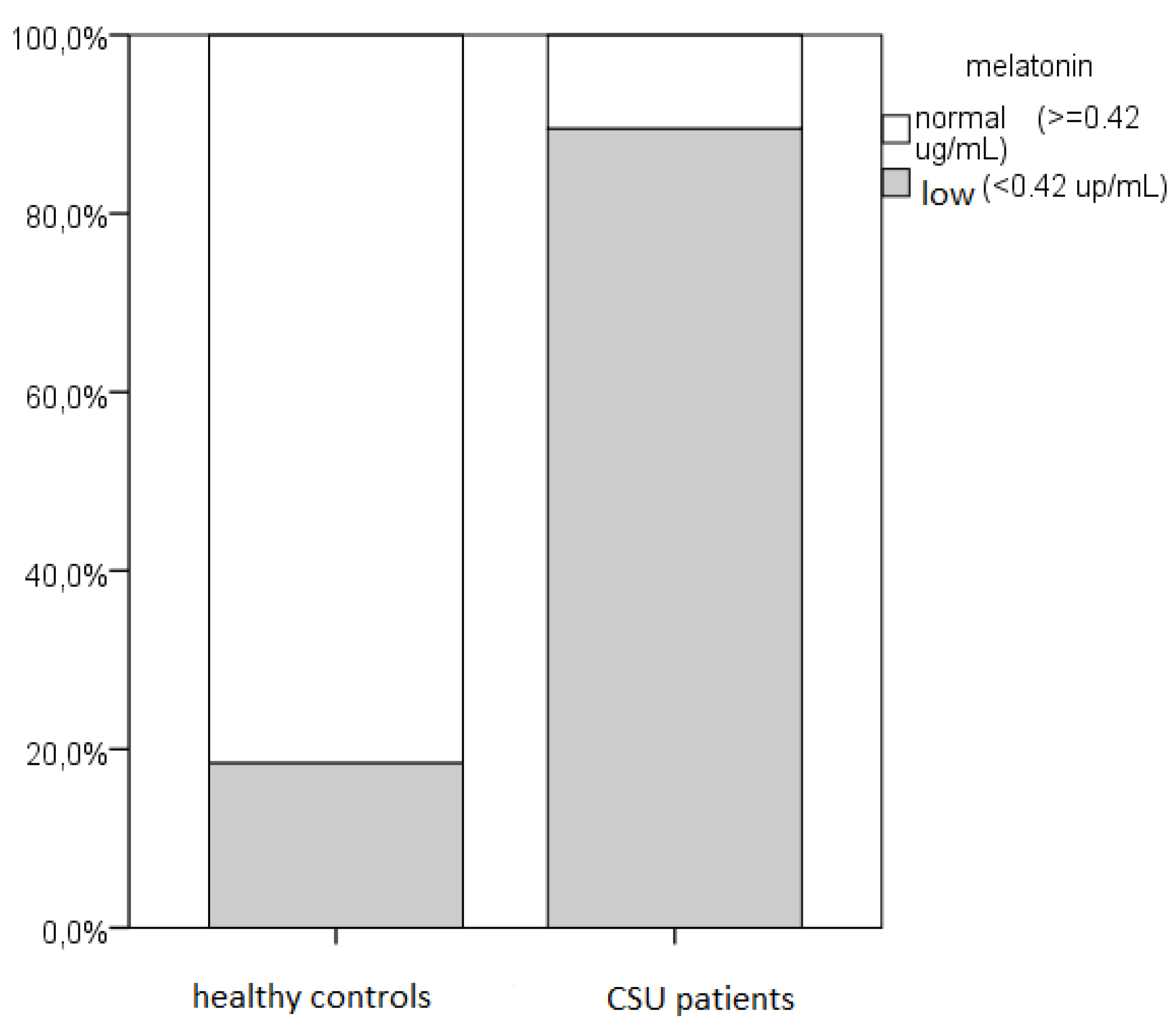

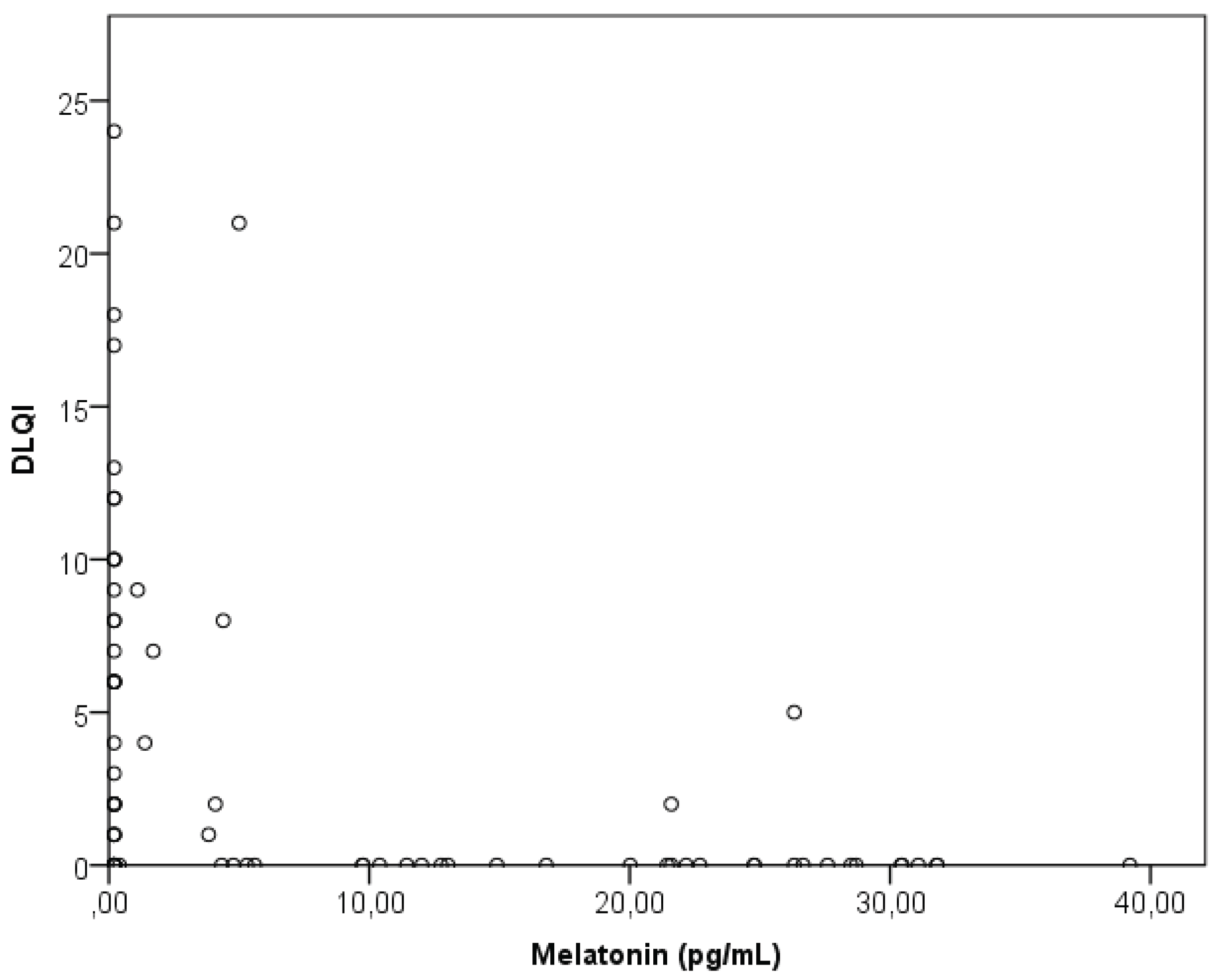

According to our recent pilot study results, in majority of CSU patients decreased salivary melatonin levels were found (86%), with significant correlation between their lower salivary melatonin values and reduced QoL [

6]. Since melatonin levels have not yet been widely studied in CSU, the aim of this study was to determine melatonin concentrations in CSU patients in relation to other clinical indicators of the disease

4. Discussion

According to research results, compared to healthy individuals, CSU patients generally had lower melatonin levels, as was fou indicating impaired sleep quality [

6,

19]. This sleep disturbance particularly reflects the negative impact of itching, the most common subjective symptom of urticaria, which disrupts their QoL

[20]. In CSU patients, itching is one of the most significant factors that, in addition to its negative impact on QoL, adversely affects their sleep quality and interferes with their daily activities [

20,

21]. Our CSU patients usually find itching more difficult to tolerate than the appearance of wheals, with itching having a significantly more significant impact on their QoL than the wheals. Itching also significantly affects their sleep quality, even though melatonin levels did not correlate with the CSU activity (UAS7), nor with itching or wheals. This discrepancy can partly be explained by the fact that the diseaase activity index (UAS) covered a 7-day period, while melatonin was measured only on the previous night, suggesting that more data and participants are needed for a broader understanding of this issue.

Sleep disturbances are frequent in patients with chronic dermatoses, particularly those accompanied by itching or pain, such as atopic dermatitis (AD), CSU, prurigo, psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa, acne vulgaris, lichen planus, etc. [

22]. Recurrent/chronic nocturnal itching (chronic) is a significant problem in these patients, often leading to disrupted sleep. According to one study, sleep disturbances are twice as common in CSU patients compared to healthy individuals and are associated with the CSU activity (UAS7 scores) [

23]. Their common sleep disturbances (on average, three nights per week) are often inadequately managed/resolved (in 48% of patients) [

24]. Compared to other skin diseases (such as psoriasis), more CSU patients reported sleep difficulties (in the last 12 months) than psoriasis patients) [

25]. Thus, CSU affects multiple aspects of psychophysiological functioning, including sleep, key physiological process that occupies one third of each life and is regulated by two processes: the sleep-wake homeostatic cycle and the circadian system ) [

22]. These sleep disturbances in CSU patients are likely due to difficulties in falling asleep and staying asleep throughout the night caused by intense itching, the occurrence of angioedema (often accompanied by pain), wakefulness triggered by histamine release from mast cells, and the presence of comorbidities (e.g., sleep apnea). However, the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of nocturnal itching is still not fully understood, and may include the circadian rhythm (the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulates corticosteroid levels in the body, with levels being lowest during the evening and night, which reflects a reduced anti-inflammatory response), decreased production of melatonin (the primary regulatory hormone of the sleep cycle and circadian rhythm), disrupted secretion of endogenous molecules involved in the physiological circadian rhythm (such as PGD2, PGE2, opioids and opioid receptors, nerve growth factor, interleukins, and cytokines: IL-2, IL-8, IL-31, IFN-γ), as well as changed epidermal barrier function (with increased transepidermal water loss at night), and adjustments in thermoregulation (the body’s highest temperature occurs in the early evening, and the lowest in the early morning hours) [

22]. Additionally, in proper sleep activity, the skin plays a vital role in regulating thermoregulation, central body temperature, and the onset of sleep and waking.

The sleep quality of our CSU patients significantly correlated with the intensity of itching, although not with the presence of hives. Also, these patients had lower melatonin levels and poorer sleep quality (along with lower QoL) than healthy individuals. Melatonin inversely correlated with their sleep quality and QoL, meaning that lower melatonin levels were associated with more impaired sleep quality and QoL. As aspected, CSU activity also impacted sleep, as patients with more severe CSU had poorer sleep quality and lower QoL. In our patients, a more substantial impairment in sleep quality and dermatological QoL was linked to lower melatonin levels, indicating that better QoL and sleep were associated with higher melatonin levels. Among various factors analyzed in our CSU patients, only sleep quality emerged as a significant predictor of melatonin levels (multiple linear regression), while, melatonin concentration did not correlate with age, dermatological QoL, sleep quality, disease duration, CSU severity (hives, itching), or disease control. In our patients CSU activity was linearly and proportionally related to impaired sleep quality and QoL, where it weakly correlated with impaired sleep quality, but strongly correlated with impaired QoL. This suggests that as the CSU severity/activity increases, the impairment of sleep quality and QoL increases, confirming the impact of CSU on sleep disturbances. According to one study in CSU patients which examined the QoL, sleep disturbances, and sleep quality ⦏using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI), and polysomnography], CSU patients had higher sleepiness (higher ESS scores) and a greater tendency toward daytime sleepiness) [

23]. Additionally, it observed an increased severity of sleep apnea (apnea-hypopnea index, AHI, which represents the number of apnea and hypopnea events per hour of sleep), indicating a mild sleep disorder. Also, their QoL positively correlated with sleep latency and sleep quality (PSQI) and negatively correlated with the urticaria duration, apnea-hypopnea index, apnea duration, total number of respiratory events, and the number of apneas) [

23]. Ultimately, sleep deprivation and loss of sleep negatively impact work performance and daily functioning, significantly affecting patients’ social life and is associated with a shorter lifespan) [

24].

In CSU patients, the disease significantly impacts their QoL due to the frequent hives/itching, the chronic disease nature, the frequency of relapses, and resistance to existing therapies. Our CSU patients have poorer QoL and sleep quality and were 3.2 times more likely to have poor sleep quality than healthy individuals. As CSU activity (UAS7) increases, there is a corresponding increase in impaired sleep and QoL. Since the QoL of our CSU patients correlated more significantly with the intensity of itching than with hives, itching disrupts their QoL more than hives, which aligns with data from the literature. In our patients, CSU most often moderately impacted QoL (36.8% experienced a moderate impact; 21% experienced a very significant or highly significant impact), which corresponds with literature data. The only significant predictor of their QoL was the activity of the clinical presentation (mostly itch). So, CSU activity (UAS7) strongly and positively correlates with impaired QoL and weakly and positively correlates with impaired sleep quality (as CSU activity increases, both QoL and sleep quality worsen). On the other hand, since the overall CSU duration did not linearly correlate with other examined factors (QoL, sleep quality, or melatonin concentration), nor with their QoL and sleep disturbances, sleep disturbances exist independently of the overall CSU duration) [

26]. Also, for CSU patients’ QoL very important is the level of disease control, as measured by the UCT score. As expected, according to our results, the greater the CSU activity, the poorer the disease control. In our patients, disease control was a significant predictor of QoL, so better urticaria control was associated with better QoL in these patients. We also observed the impact of age on CSU control, i.e., our patients who had well-controlled CSU were older than those with poor disease control. This suggests that older individuals are more attentive to disease management and avoiding triggering factors (if they exist).

According to our findings, the control of CSU (UCT) weakly and negatively correlates with impaired QoL, meaning that as CSU control improves, the impairment in QoL decreases. Although disease control (UCT) inversely correlates with disease activity (UAS7), it does not correlate with disease duration or age. According to one Japanese study, the CSU activity (UAS7) strongly positively correlates with their impaired QoL (DLQI), while disease control (UCT) strongly inversely correlated with impaired QoL (DLQI)) [

27]. Additionally, CSU activity (UAS7) significantly (inversely) correlated with CSU control (UCT), so after CSU treatment, a decrease in UAS7 scores, an increase in UCT scores, and an improvement in QoL were observed, i.e., treatment reduced the CSU activity, improved CSU control, and enhanced QoL) [

27]. So, use of the UCT questionnaire/indicator of CU control is recommended (for assessing CSU patients’ disease state and QoL) due to its practicality in everyday clinical practice and its sensitivity to treatment outcomes [

27]. This was confirmed in our study, as evidenced by the observed/confirmed correlations between UAS, UCT, and DLQI scores. Concerning the UCT index for CSU patients, the literature notes that longer disease duration is associated with poorer disease control, but our study did not observe a connection with overall disease duration) [

28]. According to the results of one study, disease control (UCT) weakly and negatively correlates with QoL but does not correlate with CSU duration or age suggesting that as disease control improves, the impairment in QoL decreases) [

27]. Additionally, CSU control (UCT) inversely correlated with CSU activity (UAS7) (itch and hives), i.e., as disease control improves, the CSU activity decreases) [

28]

. Considering the relationship between disease control, QoL, and sleep quality in our CSU patients, disease control (UCT) negatively correlates with QoL but not with sleep quality. This suggests that multiple factors influence sleep quality, highlighting the importance of considering repeated/extended measurement periods.

Research results on the QoL of CSU patients vary somewhat among authors and studies. According to the literature, their poorer QoL does not depend on age, gender, or disease duration, which aligns with our findings) [

29]. However, another study on QoL in CSU patients found that men with CSU had significantly worse QoL than women, while in our study QoL did not correlate with gender) [

30]. Additionally, one study on CSU patients found a significant correlation between QoL and fatigue [measured by the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)] and QoL. In analyzing factors influencing fatigue in CSU patients, statistical/regression analyses identified female gender and the presence of sleep disturbances as significant predictors of fatigue) [

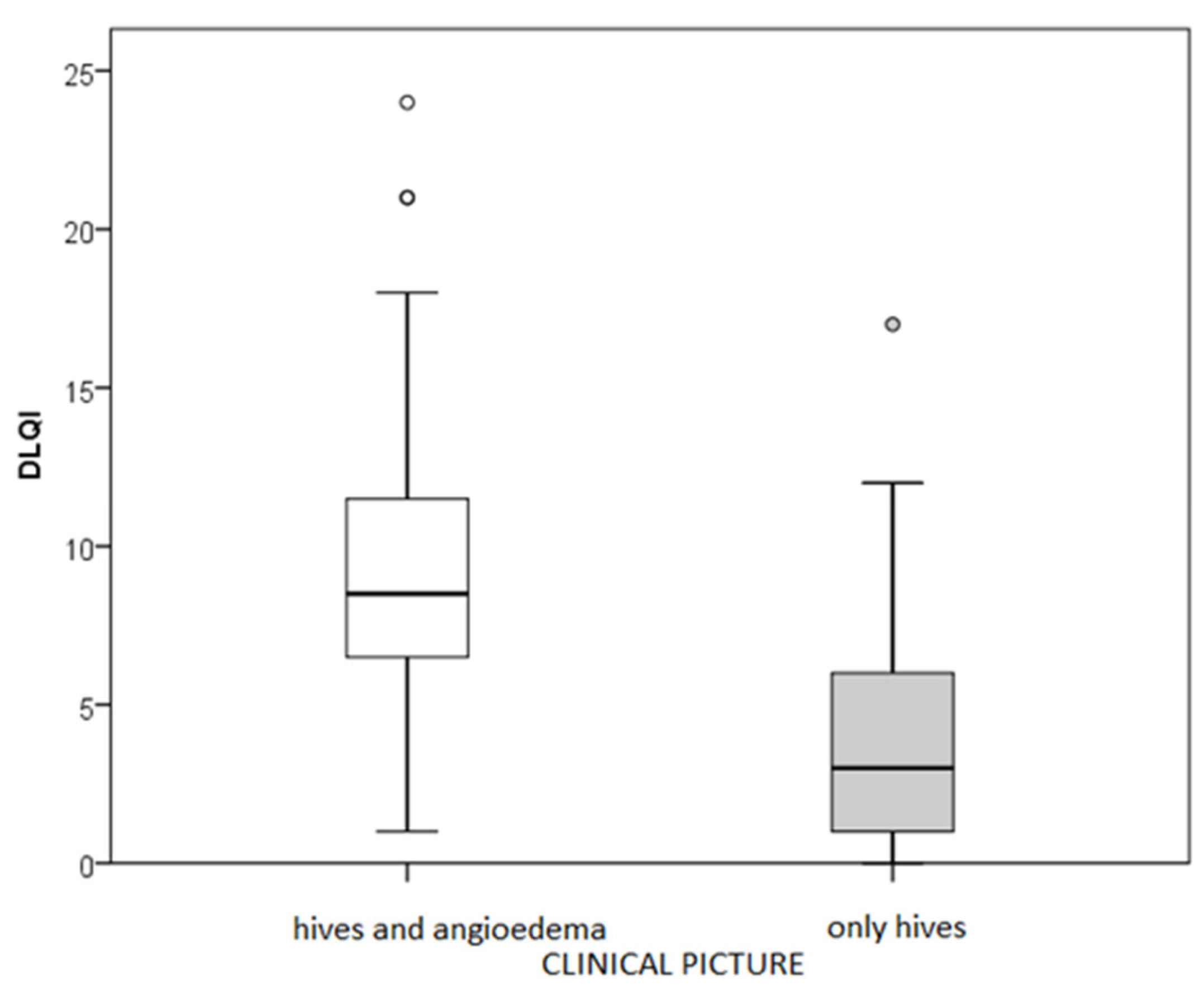

31]. Therefore, as a consequence of poor sleep quality, the most evident outcome is the feeling of fatigue that subsequently arises in these patients. The presence of accompanying angioedema is also significant, as our CSU patients with concurrent angioedema experienced impaired QoL, poorer disease control, and a more severe CSU form compared to those with wheals alone, without angioedema. Therefore, angioedema is a crucial factor that contributes to impaired QoL, reduced disease control, and increased itch intensity in these patients. According to the results of a broader study examining the relationship between CSU activity (UAS7) and QoL, the angioedema (during the previous 12 months) appeared in 66% of patients. It significantly impacted their QoL, which aligns with our findings supporting the influence of accompanying angioedema on the QoL of CSU patients) [

32]. Particularly noteworthy are the results of the extensive international prospective AWARE study, which tracked CSU patients (analyzing UAS7, DLQI, and the angioedema occurrence, etc) over two years with nine scheduled follow-ups, where angioedema was observed in 45.4% of CSU patients, similarly to our research where was found in 53% ) [

33]. According to the AWARE study results, the factors most affecting their QoL were the frequent occurrence of wheals and angioedema (visible manifestations!), intense itching, disrupted sleep, fatigue, and reduced concentration) [

33].

Reccurent hives, itch and impaired sleep often lead to psychological disturbances such as irritability, nervousness, anxiety, or heightened stress perception. The chronic nature of CSU, the inability to identify the cause or trigger for skin changes, and the frequent lack of response to treatment further contribute to these issues [

33,

34,

35]. However, the impact of the CSU on their QoL is highly subjective, for instance, patients with a mild clinical presentation may experience significantly impaired QoL, while those with a more severe CSU may not necessarily have a significantly impaired QoL [

33]. During patient treatment and follow-up, a decreased DLQI (increased QoL) and disease activity (UAS7) was observed [

33]. In the real life of CSU patients, intense itching and the unpredictable wheals/angioedema appearance are responsible for sleep disturbances and limitations in daily life, work, and sports activities. They disrupt life within the family and society and affect patients’ performance in school and work, sexual dysfunction, etc. [

29,

36]. The disease interferes with their daily routines and sleep and consequently affects their psychological state. So, urticaria is among the dermatological diseases with the highest prevalence of associated psychiatric disorders [

36]. Overall, CSU has a profound impact on patients’ QoL, particularly in those with wheals accompanied by angioedema, where psychological or psychiatric disorders often co-occur. If anxiety disorders or depressive episodes are present (which occur in 30% of CSU patients), they further contribute to the impaired QoL of these patients [

37].

Melatonin participates in various processes, with most of its effects mediated through binding to two high-affinity G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), MT1 and MT2. These receptors are predominantly expressed in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN), but are also present in several other brain regions and peripheral tissues, exhibiting tissue-specific distribution [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47]. MT1 receptors, which are highly expressed in the SCN, play a central role in regulating circadian rhythms and the sleep-wake cycle. MT2 receptors, expressed in lower amounts, are mainly located at axon terminals. In addition, melatonin also binds to other receptors such as quinone reductase 2, and interacts with many intracellular targets like calmodulin, and the retinoic acid-related orphan receptor. Also, melatonin possesses strong antioxidant properties due to its chemical structure, acting independently of receptor binding [

47]. Melatonin also acts as an immunomodulator. Human lymphocytes express melatonin receptors and are capable of synthesizing, releasing, and responding to melatonin [

48]. Also, in the skin, melatonin is expressed in both epidermal and dermal cells, which also contain its receptors. It influences T cell differentiation and activation, enhancing the production of IFN-γ and IL-2 via both membrane-bound and nuclear receptors, thereby promoting Th1 responses. Furthermore, melatonin influences Th1, Th2, Th17, and Treg responses variously depending on the immune status. During immunosuppression, it inhibits Th1, Th17, and Treg responses, whereas in immune stimulation, it supports Treg pathways. As an immunomodulatory molecule, melatonin contributes to the production of cytokines such as IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, and IL-10, and enhances T cell function while regulating cell proliferation, thereby indirectly increasing antibody production. Elevated levels of IFN-γ and IL-2 further stimulate melatonin and IL-12 synthesis, contributing to enhanced natural killer (NK) cell activity [

48]. Considering mast cell-melatonin link, melatonin appears to act in a calcium-independent manner by stabilizing microtubules and preventing granule exocytosis. According to literature data, melatonin preserves mast cell integrity by reducing exo-endocytosis following activation, thereby mitigating excessive inflammatory responses.

In lesional skin of CSU patients, the predominant cytokine profile reflects a Th2-skewed immune response, with elevated levels of IL-4, IL-5, IL-33, IL-25, and (TSLP), all of which represent potential therapeutic targets. IL-5, secreted by Th2 cells, mobilizes eosinophils from the bone marrow, enhances their responsiveness to chemotactic signals through upregulation of chemokine receptors, and acts anti-apoptotic. Thus, targeting IL-5 could provide addittional therapy options for CSU, as supported by some clinical reports showing efficacy of monoclonal antibodies such as mepolizumab and benralizumab. Also, important is the crosstalk between activated eosinophils and mast cells. Eosinophils release proteins that regulate mast cells, like eosinophil cationic protein (ECP), eosinophil peroxidase, and major basic protein. Autoantibodies (auto-IgE) directed against eosinophil protein X/eosinophil derived neurotoxin and ECP contribute to chronic disease progression. Furthermore, external eosinophil proteins can activate mast cells via the MAS-related G protein-coupled receptor X2 (MRGPRX2), promoting degranulation and initiating pruritus-related signaling. Blocking the C5a receptor axis represents another promising therapeutic approach, as it may interfere with classical complement pathway activation via IgG–FcεRI complexes and inhibit C5 cleavage by enzymes such as thrombin, Factor Xa, and plasmin. Additionally, targeting cell surface receptors such as Siglec-8, which is expressed on mast cells and eosinophils, may offer further therapeutic potential. Lirentelimab, a monoclonal antibody against Siglec-8, is currently under clinical investigation for this purpose.

Regarding the influence of melatonin on sleep, from a therapeutic perspective, melatonin plays an important role in sleep initiation, consolidation, and sleep stage architecture through MT1 and MT2 receptors. Therefore, selective targeting of MT1 or MT2 receptors offers promising therapeutic opportunities for improving sleep quality and treating sleep disorders .+ When examining sleep disorders generally and the potential therapeutic use of melatonin for patients generally (e.g., those with sleep disorders), experimental studies have shown the successful therapeutic use not only for sleep disorders but also for inflammatory neurological diseases and gastrointestinal conditions, such as Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Huntington’s disease, and ulcerative colitis [

38]. Clinically, melatonin is recommended for patients with sleep disorders and psychiatric conditions as a potential pharmacotherapeutic option [

39,

40]. Furthermore, international expert opinions and recommendations suggest the possible treatment of insomnia through the systematic melatonin use in doses ranging from 2 to 10 mg (taken one to two hours before sleep) to mimic the physiological melatonin secretion cycle [

40]. Numerous studies have reported positive outcomes from the systematic use of melatonin [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. In dermatological diseases, melatonin counteracts environmental and endogenous stressors by regulating immune responses, reducing oxidative stress, and positively influencing overall skin integrity, which makes melatonin a promising adjunct in managing dermatological conditions often associated with or exacerbated by sleep disturbances and psychological stress [

6,

45]

.

Current treatment of CU (according to global guidelines) includes: 1st line: second-generation H1 antihistamines (up to 4 tablets per day), if necessary short courses of systemic corticosteroids; 2nd line: add omalizumab to antihistamines; 3rd line: add cyclosporine to antihistamines and omalizumab. Drugs recently tested or currently in clinical trials target multiple molecules, including: ligelizumab (a humanized IgG1 anti-IgE antibody)); drugs that act on intracellular signaling molecules (Syk inhibitors and Btk inhibitors); drugs that act on receptors that regulate inflammatory cell chemotaxis (CRTH2 antagonists); monoclonal antibodies to Siglec-8 that promote eosinophil apoptosis and block the influence of mediators on mast cells, and others [

1,

49]. According to recent literature, melatonin could stabilize mast cell membranes and inhibit degranulation, which could be a useful tool for treating diseases characterized by acute or chronic inflammatory processes involving mast cells, through a calcium-independent mechanis. Since pathological activation of mast cells is a key event in mast cell-related and -mediated diseases, such as allergic diseases (e.g., chronic urticaria) and irritable bowel syndrome, there is a clear need for further studies exploring potential therapeutic strategies to inhibit mast cell activation [

46].