Introduction

Obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) affects approximately fifty percent of autistic youth and, when present, frequently resists conventional treatment, exacerbates depressive episodes, incites aggression, and intensifies social withdrawal [

1,

2]. Current pathophysiological frameworks identify the issue within cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) circuits, where recurrent “thought-ritual” associations enhance synapses that monoaminergic drugs or antipsychotics rarely diminish [

3,

4].

Glutamatergic strategies have changed the conversation. A single intravenous dose of ketamine can loosen CSTC rigidity within hours by briefly blocking N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, driving an α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) glutamate surge, and launching a brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)–mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) cascade that rebuilds dendritic spines [

5,

6]. Practical limits—infusions, cost, dissociation—keep ketamine out of routine care, leading clinicians to explore oral substitutes. One low-cost option couples dextromethorphan (an NMDA antagonist) with a strong CYP2D6 inhibitor such as fluoxetine to extend exposure; piracetam can then amplify downstream AMPA signalling [

7,

8].

Adolescence might be the most suitable time for this approach. Imaging and post-mortem data reveal that autistic brains undergo a period of accelerated, and occasionally excessive, synaptic pruning during adolescence [

9,

10]. Reduced synaptic density in autistic adults on ^11C-UCB-J PET corroborates that trajectory [

11]. Interventions that can direct plasticity during active pruning may have a significant impact.

We describe the course of a 15-year-old boy with high-functioning autism, ADHD, and severe, refractory OCD marked by violent outbursts, referential ideas, and command-like hallucinations. Rapid and lasting remission followed the bedtime addition of fluoxetine-potentiated dextromethorphan and low-dose piracetam to an otherwise stable mood-stabiliser/antipsychotic regimen.

Methods

Care was delivered in a private outpatient clinic in Hong Kong between August and December 2025. The author provided all treatment. Parents gave written consent for anonymised publication; the adolescent gave written assent.

At each visit the clinician conducted an open clinical interview with the patient and parents and collected:

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)

The Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale was not part of routine practice; obsessional severity was tracked clinically. Adverse events were sought through open questioning and spontaneous report.

Primary clinical targets were obsessions, compulsions, aggression, referential thinking, hallucinations, social avoidance, and overall functioning, as rated by the treating psychiatrist and parents. Secondary endpoints were PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores and tolerability signals (e.g., tachycardia, tremor).

Case Presentation

A 15-year-old boy was brought to clinic on 12 August 2025 by his parents because of rapidly worsening behaviour and severe obsessive-compulsive symptoms. His developmental history was notable for autism spectrum disorder and combined-type attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. During the preceding months he had withdrawn from social situations, refused to eat in restaurants, and insisted that strangers stared at him or spoke about him. At home he was volatile; on one occasion he threw a chair at school and frequently directed anger toward his parents, whom he blamed for his height and appearance.

Psychiatric review uncovered several additional problems. He described derogatory auditory hallucinations that criticised him whenever he made mistakes, and he ruminated for hours about the size and shape of his “head bone.” Episodes of low mood alternated with periods of high energy, inappropriate giggling, minimal need for sleep, and disinhibited sexual talk. Obsessive-compulsive rituals were pronounced: he pushed his toothbrush so far into his mouth that his gums bled, feared contamination, and engaged in lengthy mental checking. Screening scores supported the clinical picture (CAST 27; Vanderbilt inattentive 9, hyperactive-impulsive 3).

At the first visit risperidone 1 mg nightly and sodium valproate 500 mg nightly were prescribed for irritability and mood lability. Alprazolam 0.25 mg was provided on a “pro re nata” basis but was seldom required. No medication specifically targeted obsessive-compulsive symptoms at that stage.

Six days later, on 18 August, little improvement was evident. The boy remained preoccupied with body image and continued to hear voices. An evening regimen aimed at glutamatergic modulation was therefore introduced: fluoxetine 10 mg and dextromethorphan 30 mg (two 15 mg tablets) were added while risperidone and valproate were maintained.

Within eight days parents reported a striking change. Violent outbursts ceased, appetite improved, and both hallucinations and referential ideas disappeared. Tooth-brushing remained ritualised but less injurious. The patient declared he felt “much better” and prepared to return to his music studies in mainland China. His full bedtime prescription—fluoxetine, dextromethorphan, risperidone, and valproate—was continued without adjustment.

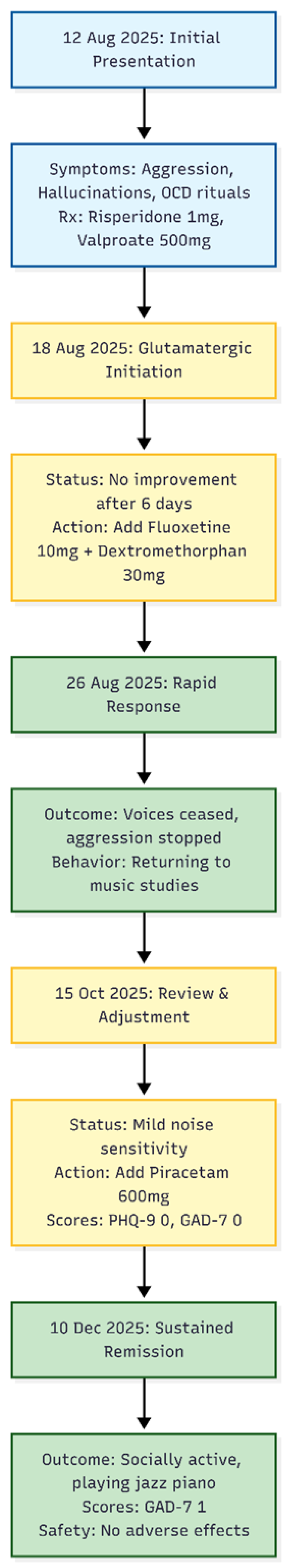

Figure 1.

Timeline of Clinical Course. The diagram illustrates the rapid stabilization of severe behavioral and obsessive-compulsive symptoms following the addition of the Fluoxetine-Dextromethorphan combination on August 18, followed by further refinement with Piracetam in October.

Figure 1.

Timeline of Clinical Course. The diagram illustrates the rapid stabilization of severe behavioral and obsessive-compulsive symptoms following the addition of the Fluoxetine-Dextromethorphan combination on August 18, followed by further refinement with Piracetam in October.

On 15 October, seven weeks later, he returned for review after time away. Stability had persisted, though he noted sensitivity to noise with associated irritability on coming back to Hong Kong. To address this residual symptom, piracetam 600 mg nightly was added. Depression and anxiety scales were both zero (PHQ-9 = 0, GAD-7 = 0).

A further assessment on 10 December confirmed sustained remission. The teenager now dined out without fear, spoke freely in an English conversation class, played jazz piano daily, and demonstrated only minimal anxiety (GAD-7 = 1). His father remarked that the boy was “much less anxious and much less irritable than I have ever seen him.” No adverse effects—such as dissociation, tachycardia, tremor, or serotonin toxicity—were observed.

Medication Course (all doses at bedtime)

12 Aug 2025: risperidone 1 mg, valproate 500 mg

18 Aug 2025: fluoxetine 10 mg, dextromethorphan 30 mg added

15 Oct 2025: piracetam 600 mg added

10 Dec 2025: regimen unchanged

Four months after the first glutamatergic augmentation, the patient remained free of obsessive ruminations, hallucinations, aggression, and mood instability. The low-dose evening combination of fluoxetine and dextromethorphan, later complemented by piracetam, produced a rapid and durable remission of treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive symptoms without side-effects. This case suggests that targeted, bedtime-only glutamatergic strategies may benefit adolescents with complex neurodevelopmental comorbidities and severe OCD that has not responded to standard care.

Discussion

Modern models view obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) as a problem of faulty learning in the cortico-striato-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) network, where repeated “obsession-relief” cycles hard-wire maladaptive synapses [

3,

4]. The present adolescent, who also lives with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and ADHD, showed how quickly that wiring can be softened. When low-dose fluoxetine-potentiated dextromethorphan (DXM) was started, and later piracetam was added, his PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores fell from severe to zero and have stayed there for four months. No changes were made to risperidone 1 mg or valproate 500 mg, and no dissociative or psychotomimetic effects appeared. The timeline strongly suggests that targeted glutamatergic modulation—not sedation or extra serotonin—drove the change.

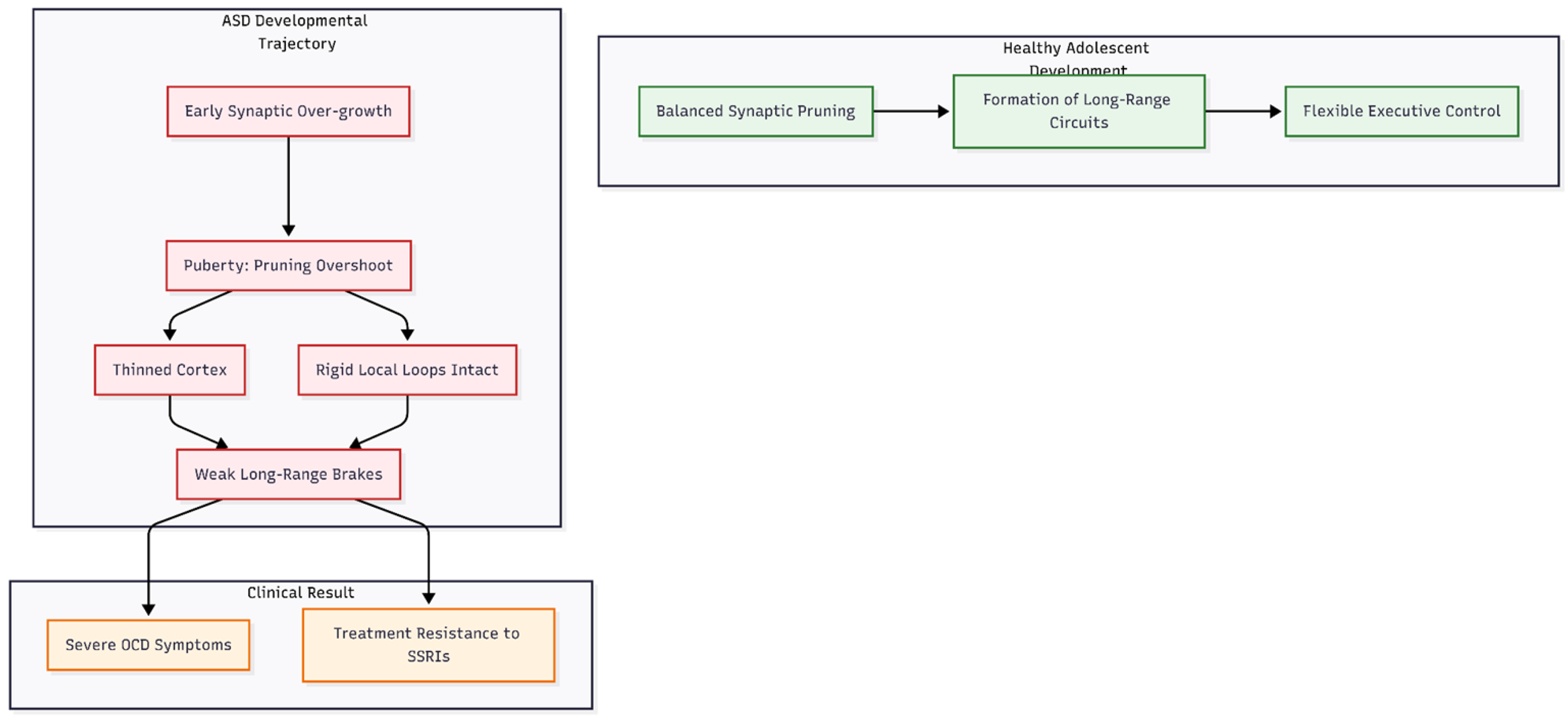

Why might an adolescent with ASD respond so sharply (

Figure 2)? Work in brains and animal models shows that ASD features early synaptic over-growth followed by late, uneven pruning [

9,

10]. Around puberty the pruning can overshoot, thinning cortex yet leaving “rigid” local loops intact [

11,

12]. Too many short-range loops and too few long-range brakes set the stage for severe OCD [

13]. Standard serotonin or dopamine drugs do little to correct that balance.

Figure 2.

Developmental Mismatch in Adolescent ASD. The diagram illustrates the “Pruning Overshoot” hypothesis. While healthy development balances pruning with circuit formation, the ASD trajectory involves early overgrowth followed by excessive pruning during puberty. This leaves the brain with too many rigid short-range loops and insufficient long-range inhibitory “brakes,” creating a structural basis for severe, treatment-resistant OCD.

Figure 2.

Developmental Mismatch in Adolescent ASD. The diagram illustrates the “Pruning Overshoot” hypothesis. While healthy development balances pruning with circuit formation, the ASD trajectory involves early overgrowth followed by excessive pruning during puberty. This leaves the brain with too many rigid short-range loops and insufficient long-range inhibitory “brakes,” creating a structural basis for severe, treatment-resistant OCD.

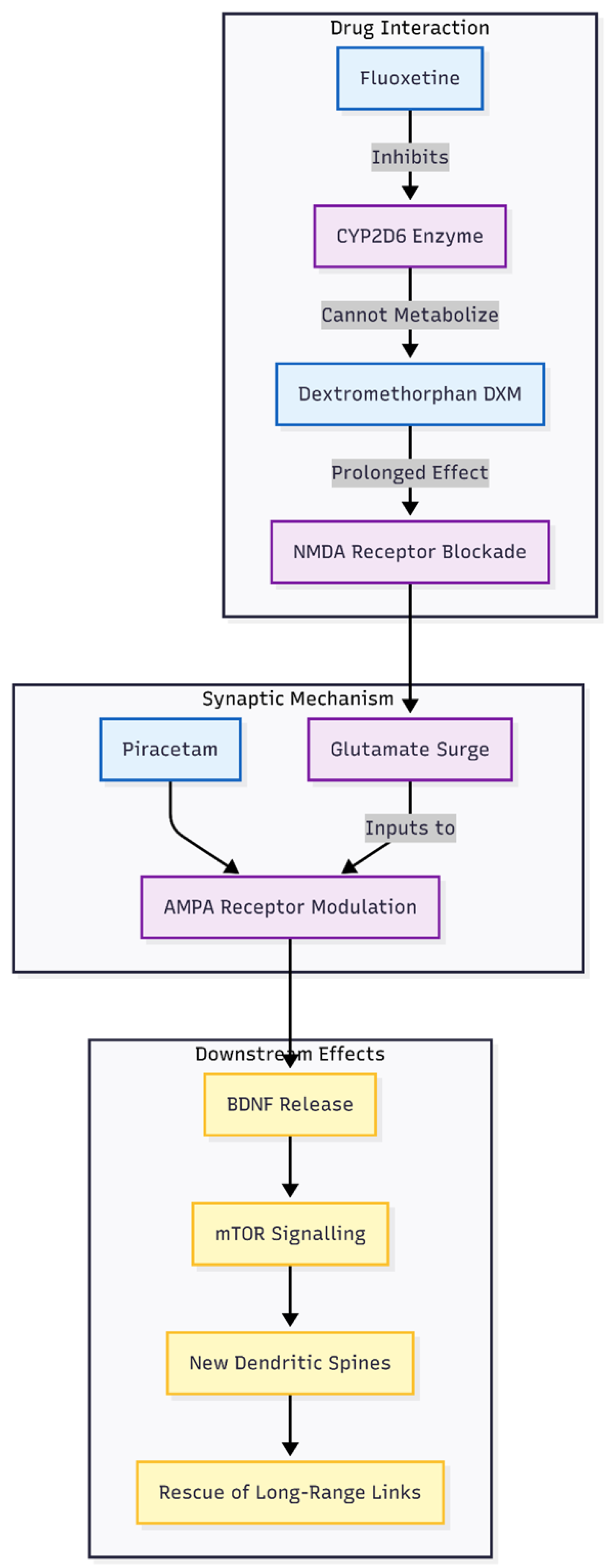

Figure 3.

Mechanism of Glutamatergic Augmentation. The flowchart demonstrates the synergistic action of the regimen. Fluoxetine inhibits CYP2D6, prolonging Dextromethorphan’s bioavailability. This leads to sustained NMDA blockade and a subsequent glutamate surge. Piracetam modulates AMPA receptors to ensure this surge triggers BDNF release and mTOR signaling, resulting in new dendritic spine formation that repairs faulty CSTC network connections.

Figure 3.

Mechanism of Glutamatergic Augmentation. The flowchart demonstrates the synergistic action of the regimen. Fluoxetine inhibits CYP2D6, prolonging Dextromethorphan’s bioavailability. This leads to sustained NMDA blockade and a subsequent glutamate surge. Piracetam modulates AMPA receptors to ensure this surge triggers BDNF release and mTOR signaling, resulting in new dendritic spine formation that repairs faulty CSTC network connections.

The evening glutamatergic regimen seems to fit this developmental window. Brief NMDA blockade by DXM—prolonged because fluoxetine blocks CYP2D6—lets glutamate surge, much like intravenous ketamine [

6,

14]. Piracetam then nudges AMPA receptors so the surge translates into brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) release, mTOR signalling, and new spines [

5,

15,

16]. In an adolescent who is pruning too fast, that extra spine formation may rescue the long-range prefrontal–striatal links that curb compulsions. Clinically, the boy stopped ruminating about his appearance, ate in restaurants, and resumed jazz piano—behaviours that rely on flexible executive control [

17].

Giving all glutamatergic doses at bedtime may help. NMDA receptor density and glutamate turnover peak during sleep, when slow-wave activity locks in new connections. Aligning drug action with this plasticity window could increase benefit while avoiding daytime overstimulation.

This single case has limits. Formal Y-BOCS scores were not collected, and concomitant medicines could confound the picture. Genetic data (for example CYP2D6 status) and imaging would add certainty. Still, the scale and speed of improvement mirror published DXM–piracetam series [

8] and early ketamine trials [

6]. Controlled studies that pair Y-BOCS with glutamate-sensitive MRI or ¹¹C-UCB-J PET are now warranted.

In summary, adolescence may offer a short-lived chance to guide pruning toward healthy circuits. Low-dose, bedtime NMDA–AMPA modulation provided a safe, inexpensive way to seize that chance in a neurodivergent teenager whose OCD had resisted standard care [

18].

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

References

- Ivanović, I. Psychiatric comorbidities in children with ASD: Autism centre experience. Front Psychiatry 2021, 12, 673169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, S.M.; Petersen, L.; Schendel, D.E.; et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder and autism spectrum disorders: longitudinal and offspring risk. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0141703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal, B.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Sahakian, B.J. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: etiology, neuropathology, and cognitive dysfunction. Brain Behav 2023, 13, e3000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Xiao, S.; Su, T.; et al. A multimodal meta-analysis of regional functional and structural brain abnormalities in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2024, 274, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, N.; Lee, B.; Liu, R.J.; et al. mTOR-dependent synapse formation underlies the rapid antidepressant effects of NMDA antagonists. Science 2010, 329, 959–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, C.I.; Kegeles, L.S.; Levinson, A.; et al. Randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: proof-of-concept. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 2475–2483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. DXM, CYP2D6-inhibiting antidepressants, piracetam, and glutamine: proposing a ketamine-class antidepressant regimen with existing drugs. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, N. Case series: marked improvement in treatment-resistant obsessive–compulsive symptoms with over-the-counter glutamatergic augmentation in routine clinical practice. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Gudsnuk, K.; Kuo, S.H.; et al. Loss of mTOR-dependent macroautophagy causes autistic-like synaptic pruning deficits. Neuron 2014, 83, 1131–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zielinski, B.A.; Prigge, M.B.D.; Nielsen, J.A.; et al. Longitudinal changes in cortical thickness in autism and typical development. Brain 2014, 137, 1799–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matuskey, D.; Yang, Y.; Naganawa, M.; et al. 11C-UCB-J PET imaging is consistent with lower synaptic density in autistic adults. Mol Psychiatry 2025, 30, 1610–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khundrakpam, B.S.; Lewis, J.D.; Kostopoulos, P.; et al. Cortical thickness abnormalities in autism spectrum disorders through late childhood, adolescence, and adulthood: a large-scale MRI study. Cereb Cortex 2017, 27, 1721–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faust, T.E.; Gunner, G.; Schafer, D.P. Mechanisms governing activity-dependent synaptic pruning in the developing mammalian CNS. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021, 22, 657–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, R.S.; Aghajanian, G.K. Synaptic dysfunction in depression: potential therapeutic targets. Science 2016, 338, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koike, H.; Iijima, M.; Chaki, S. Involvement of AMPA receptor in both the rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects of ketamine in animal models. Behav Brain Res 2011, 224, 107–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeng, S.; Zarate, CAJr; Du, J.; et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: role of AMPA receptors. Biol Psychiatry 2008, 63, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, H.C.; Beltz, A.M.; Himle, J.A.; et al. Changes in brain network connections after exposure and response prevention therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder in adolescents and adults. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging 2024, 9, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, N. Timing is everything: why the Cheung glutamatergic regimen is contraindicated in young children with autism but promising after puberty. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).