Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Finding the Symmetries of the Fisher’s Equation

2.1. Commutator of the Symmetries

- The order in which the symmetries are applied does not matter.

- The symmetry algebra generated by and is Abelian.

- These symmetries may be used independently to reduce the PDE, or in combination (e.g., as a linear combination for a travelling–wave variable ).

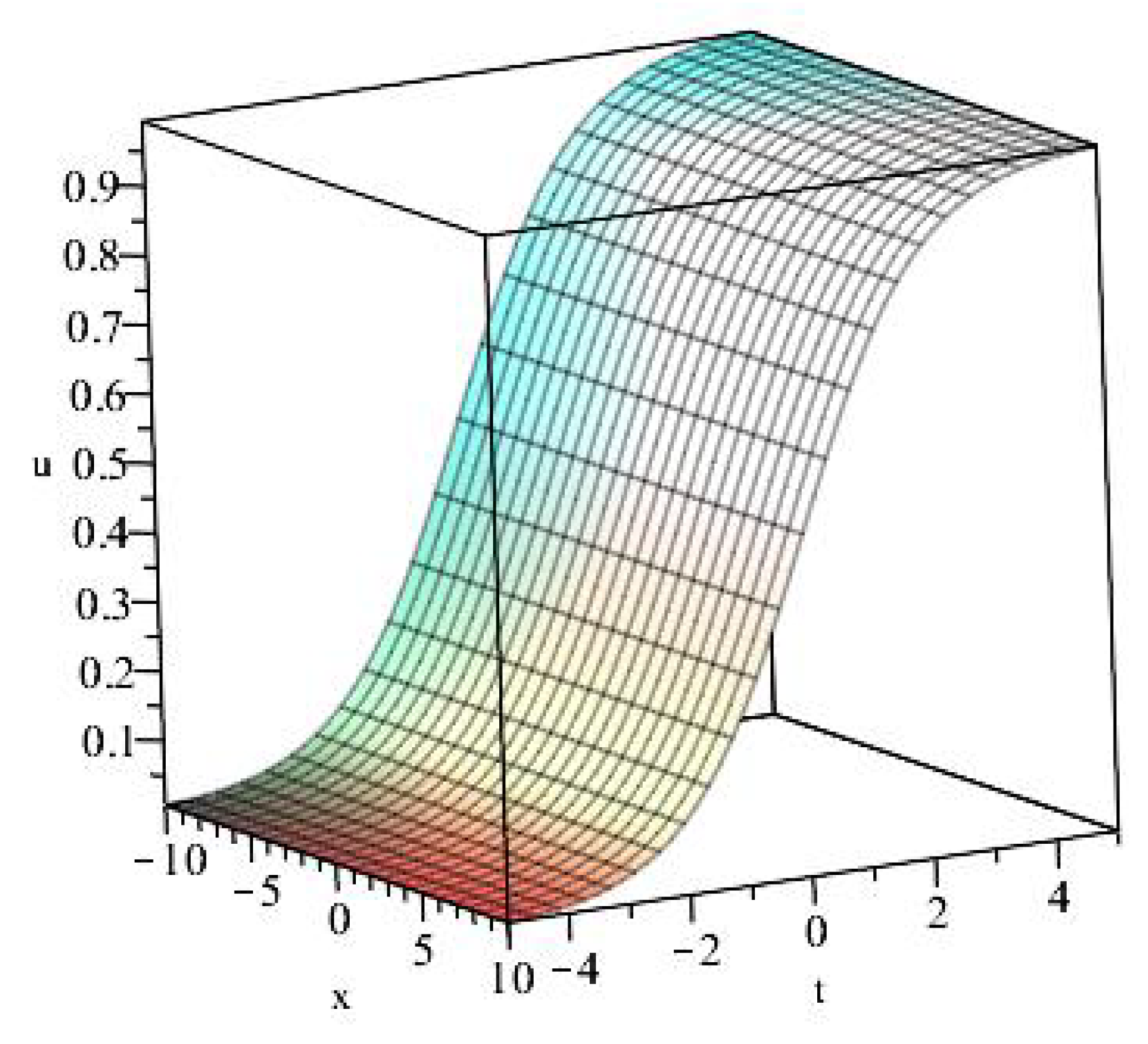

2.2. Invariant Solution Using

2.3. Invariant Solution Using

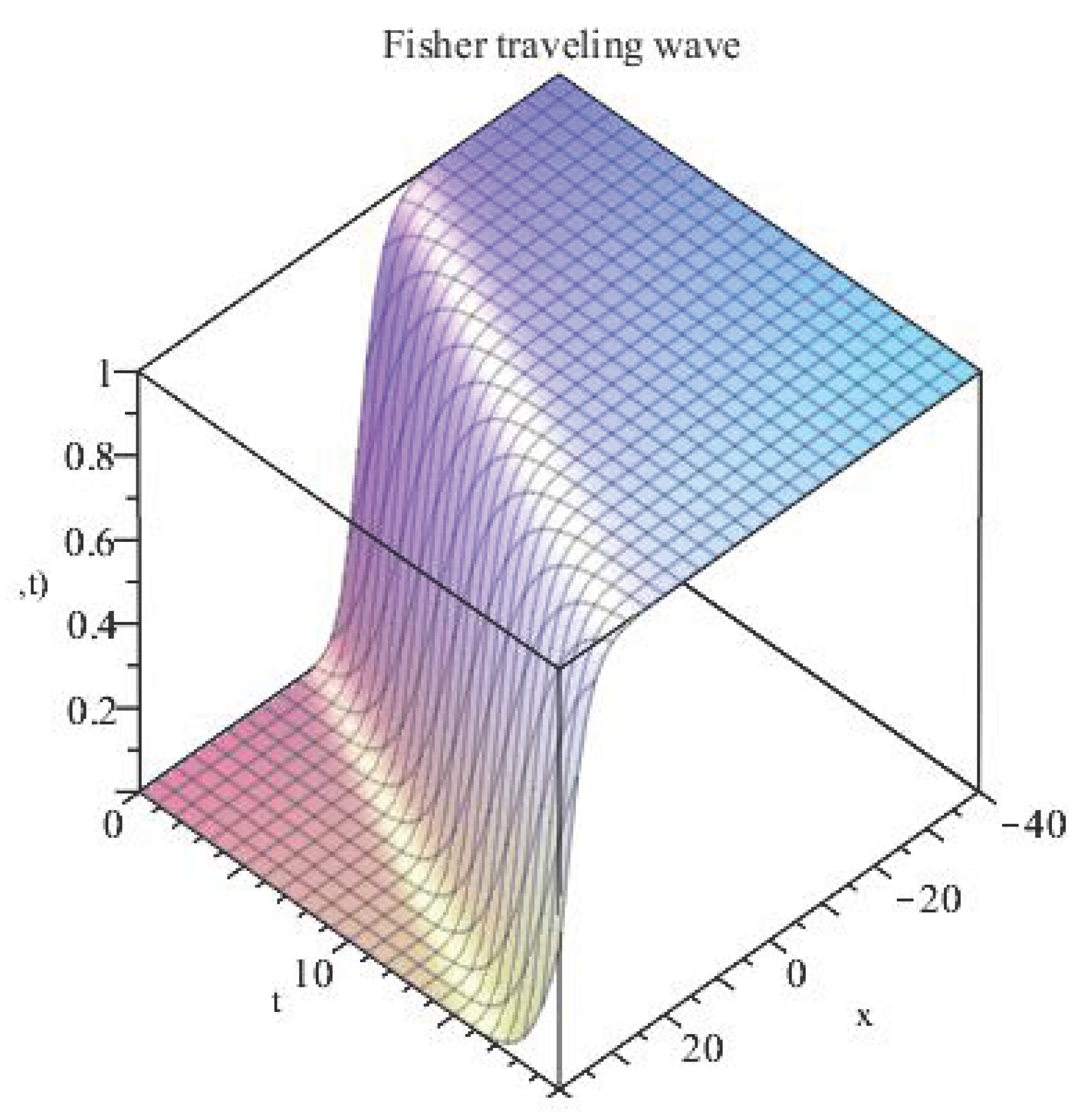

2.4. Invariant Solution Using The Travelling-Wave Symmetry

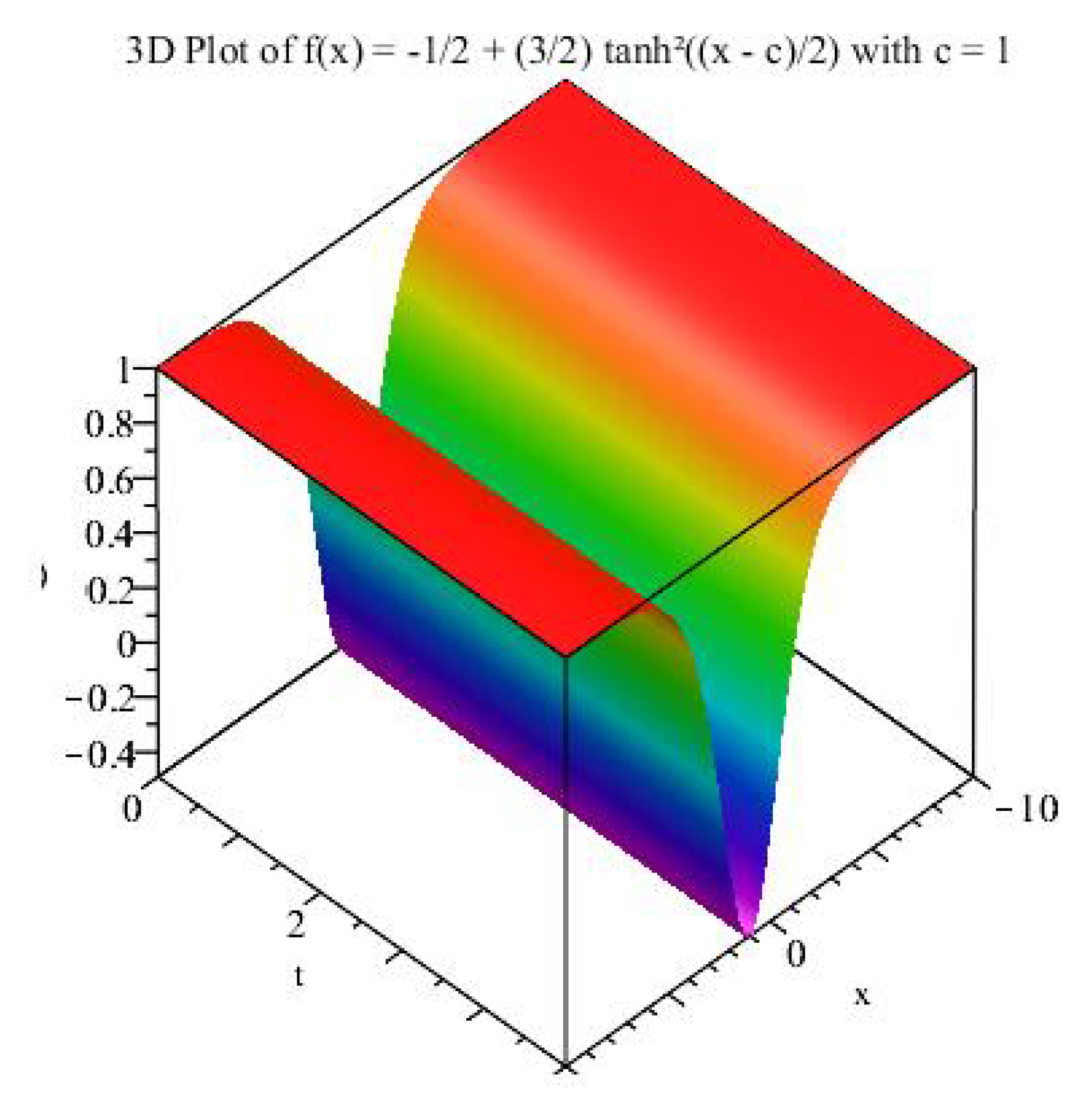

Case 1:

Case 2:

3. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turing, A.M. The chemical basis of morphogenesis. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 1952, 237, 37–72. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, J.D. Mathematical Biology I: An Introduction, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cosner, C. Reaction–diffusion equations and ecological modeling. In Tutorials in Mathematical Biosciences IV: Evolution and Ecology; Springer, 2008; pp. 77–115. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R.A. The wave of advance of advantageous genes. Annals of Eugenics 1937, 7(4), 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.; Petrovsky, I.; Piskunov, N. Étude de l’équation de la diffusion avec croissance de la quantité de matière et son application à un problème biologique. Moscou Univ. Math. Bull. 1937, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ablowitz, M.J.; Zeppetella, A. Explicit solutions of Fisher’s equation for a special wave speed. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 1979, 41(6), 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, D.G.; Weinberger, H.F. Nonlinear diffusion in population genetics, combustion, and nerve pulse propagation. In Partial Differential Equations and Related Topics; Springer, 1975; pp. 5–49. [Google Scholar]

- Feroe, J.A. Travelling wave solutions of the Nagumo equation. SIAM Journal on Applied Mathematics 1982, 42(2), 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinner, B. Existence of traveling wavefront solutions for the discrete Nagumo equation. Journal of Differential Equations 1992, 96(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loyinmi, A.C.; Akinfe, T.K. Exact solutions to the family of Fisher’s reaction–diffusion equation using Elzaki homotopy transformation perturbation method. Engineering Reports 2020, 2(2), e12084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, R.C.; Jain, R.K. Numerical solutions of nonlinear Fisher’s reaction–diffusion equation with modified cubic B–spline collocation method. Mathematical Sciences 2013, 7(1), 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, G.; Kannan, K. Review of wavelet methods for the solution of reaction–diffusion problems in science and engineering. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2014, 38(3), 799–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, A.H.; Martínez, L.J.; Fernández, O. Reaction–diffusion equations: a chemical application. Scientia et Technica 2010, 3(46), 134–137. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Pan, H. New solitary wave solutions of the Fisher equation. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics 2022, 10(11), 3356–3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, D.J. Symmetry Analysis of Differential Equations: An Introduction; John Wiley & Sons, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bluman, G.; Anco, S. Symmetry and Integration Methods for Differential Equations; Springer Science & Business Media, 2008; volume 154. [Google Scholar]

- Bluman, G.W.; Kumei, S. Symmetries and Differential Equations; Springer Science & Business Media, 2013; volume 81. [Google Scholar]

- Hydon, P.E. Symmetry Methods for Differential Equations: A Beginner’s Guide; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- CRC Handbook of Lie Group Analysis of Differential Equations; Ibragimov, N.H., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 1996; Vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ovsiannikov, L.V. Group Analysis of Differential Equations; Academic Press: New York, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hereman, W.; Malfliet, W. The tanh method: a tool to solve nonlinear partial differential equations with symbolic software. In Proceedings of the 9th World Multi-Conference on Systemics, Cybernetics and Informatics, Orlando, FL, 2005; pp. 165–168. [Google Scholar]

- Hendi, A. The extended tanh method and its applications for solving nonlinear physical models. IJRRAS 2010, 3(1), 83–91. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).