Submitted:

02 December 2024

Posted:

02 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- The full classical symmetry classification of the class of nonlinear reaction-diffusion equations was carried out by Basarab-Horwath et al. [4];

-

Full classical symmetry classifications of sub-classes of (1) have been performed using equivalence groups.

- −

- −

2. Non-Classical Symmetry Analysis

- ;

- ;

- , with , and , 1;

- , with ;

- , with .

3. Non-Lie Non-Classical Symmetry Solutions

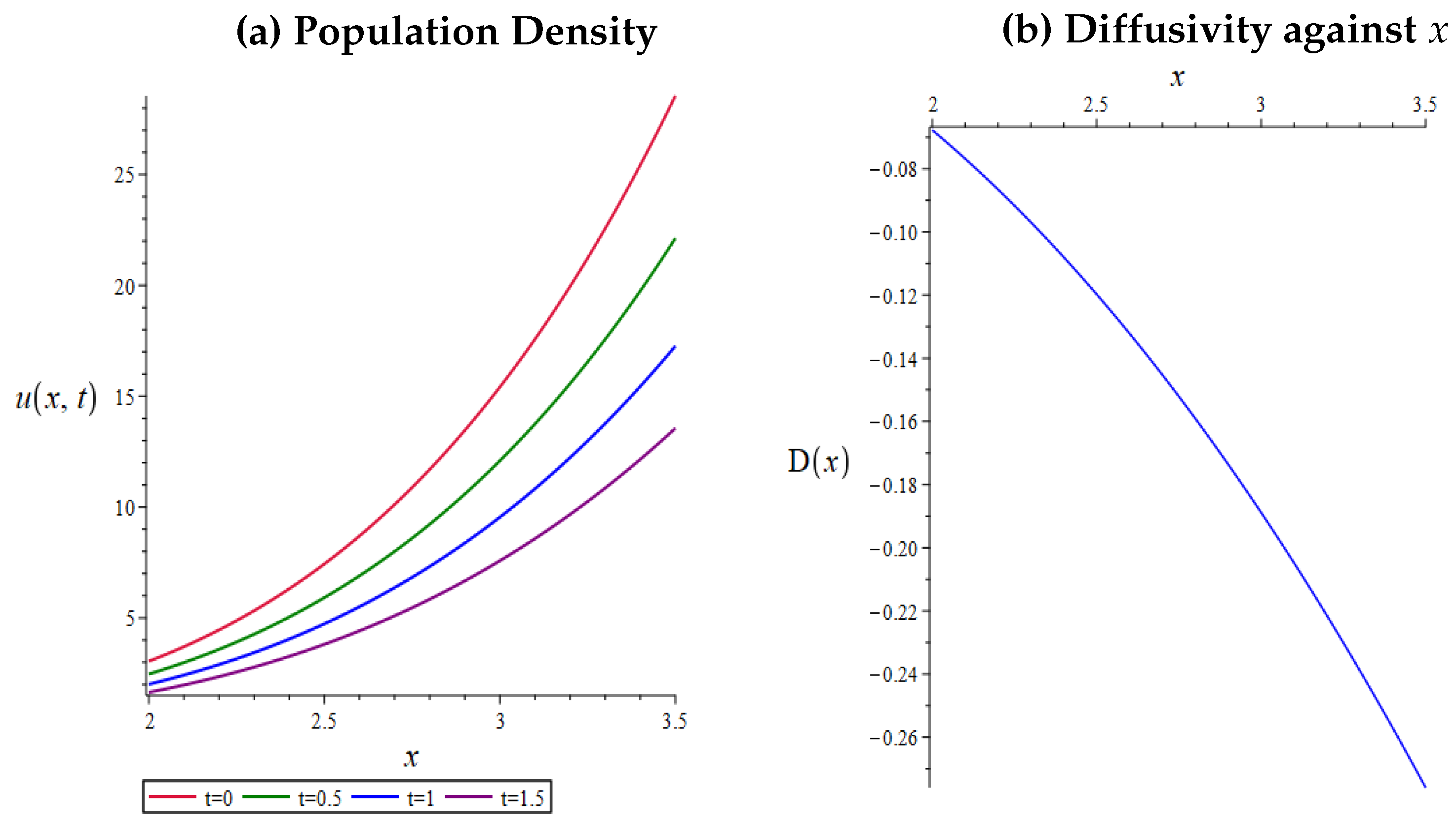

- the inhabitants aggregate to the boundary at , since the population density increases at an increasing rate while the diffusivity is negative and decreases at a decreasing rate;

- the population density is bounded by ;

- as t increases, the inhabitants continue to aggregate but are dying, since the density decreases.

4. Discussion and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PDE | Partial differential equation |

| ISC | Invariant surface condition |

| ODE | Ordinary differential equation |

| WLOG | Without loss of generality |

References

- Bakhvalov, P. ColESo: Collection of exact solutions for verification of numerical algorithms for simulation of compressible flows. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2023, 282, 108542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelmsson, H. Explosive instabilities of reaction-diffusion equations. Phys. Rev. A 1987, 36, 965–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw-Hajek, B.H.; Broadbridge, P. Analytic solutions for calcium ion fertilisation waves on the surface of eggs. Mathematical Medicine and Biology: A Journal of the IMA 2019, 36, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basarab-Horwath, P.; Lahno, V.; Zhdanov, R. The structure of Lie algebras and the classification problem for partial differential equations. Acta Appl. Math. 2001, 69, 43–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaneeva, O.O.; Johnpillai, A.G.; Popovych, R.O.; Sophocleous, C. Enhanced group analysis and conservation laws of variable coefficient reaction-diffusion equations with power nonlinearities. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2007, 330, 1363–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaneeva, O.O.; Popovych, R.O.; Sophocleous, C. Enhanced group analysis and exact solutions of variable coefficient semilinear diffusion equations with a power source. Acta Appl. Math. 2009, 106, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaneeva, O.O.; Popovych, R.O.; Sophocleous, C. Extended group analysis of variable coefficient reaction-diffusion equations with exponential nonlinearities. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2012, 396, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaneeva, O. Group classification via mapping between classes: an example of semilinear reaction-diffusion equations with exponential nonlinearity. 2008, ArXiv: Nonlinear Sciences: Exactly Solvable and Integrable Systems 0811.2587. ArXiv.org e-Print archive. https://arxiv.org/abs/0811.2587.

- Vaneeva, O.O.; Popovych, R.O.; Sophocleous, C. Reduction operators of variable coefficient semilinear diffusion equations with a power source. 2009, ArXiv: Nonlinear Sciences: Exactly Solvable and Integrable Systems 0904.3424. ArXiv.org e-Print archive. https://arxiv.org/abs/0904.3424.

- Vaneeva, O.O.; Popovych, R.O.; Sophocleous, C. Reduction operators of variable coefficient semilinear diffusion equations with an exponential source. 2010, ArXiv: Nonlinear Sciences: Exactly Solvable and Integrable Systems 1010.2046. ArXiv.org e-Print archive. https://arxiv.org/abs/1010.2046.

- Broadbridge, P.; Bradshaw, B.H.; Fulford, G.R.; Aldis, G.K. Huxley and Fisher equations for gene propagation: an exact solution. ANZIAM J. 2002, 44, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Roux, M.N.; Wilhelmsson, H. External boundary effects on simultaneous diffusion and reaction processes. Phys. Scr. 1989, 40, 674–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moitsheki, R.J.; Bradshaw-Hajek, B.H. Symmetry analysis of a heat conduction model for heat transfer in a longitudinal rectangular fin of a heterogeneous material. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2013, 18, 2374–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman, E.; Braverman, L. Optimal harvesting of diffusive models in a nonhomogeneous environment. Nonlinear Anal. Theor. 2009, 71, e2173–e2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw-Hajek, B.H.; Moitsheki, R.J. Symmetry solutions for reaction-diffusion equations with spatially dependent diffusivity. Appl. Math. Comput. 2015, 254, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw-Hajek, B.H. Nonclassical symmetry solutions for non-autonomous reaction-diffusion equations. Symmetry 2019, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyanin, A.D.; Zhurov, A.I. Separation of Variables and Exact Solutions to Nonlinear PDEs, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-0-367-48689-1. [Google Scholar]

- Polyanin, A.D. Functional separable solutions of nonlinear reaction–diffusion equations with variable coefficients. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 347, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.A.; Kruskal, M.D. New similarity reductions of the Boussinesq equation. J. Math. Phys. 1989, 30, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyanin, A.D. Construction of exact solutions in implicit form for PDEs: new functional separable solutions of non-linear reaction–diffusion equations with variable coefficients. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 2019, 111, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, E.M.; Rodrigues, M.M. Exact and Approximate Solutions of Reaction-Diffusion-Convection Equations. Conference on Boundary Value Problems: Mathematical Models in Engineering, Biology and Medicine;, 2008; Vol. 1142, pp. 304–313. [CrossRef]

- Lie, S. Über die integration durch bestimmte integrale von einer classe linearer partieller differentialgleichungen. Archiv der Mathematik 1881, 6, 328–368. (in German). [Google Scholar]

- Lie, S. Allgemeine untersuchungen über differentialgleichungen, die eine continuirliche, endliche gruppe gestatten. Mathematische Annalen 1885, 25, 71–151. (in German). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, D. Symmetry Analysis of Differential Equations, 1st ed.; John Wiley & Sons Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1118721407. [Google Scholar]

- Sherring, J. Dimsym Users Manual. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, 1993.

- Hearn, T. REDUCE; A Portable General-Purpose Computer Algebra System, SourceForge, 2022. Available online at https://sourceforge.net/projects/reduce-algebra/.

- Cheviakov, A.F. GeM software package for computation of symmetries and conservation laws of differential equations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2007, 176, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maple (2021), Maplesoft, a Division of Waterloo Maple Incorporated; Waterloo, Ontario, 2021.

- Olver, P.J. Applications of Lie Groups to Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 9781461243502. [Google Scholar]

- Ovsiannikov, L.V. Group Analysis of Differential Equations: Ames, W.F. Eds.; Academic Press Incorporated: New York, NY, USA, 1982; ISBN 978-0-12-531680-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bluman, G.W. Construction of Solutions to Partial Differential Equations by the Use of Transformation Groups. Ph.D. Dissertation, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA, November 14 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bluman, G.W.; Cole, J.D. The general similarity solution of the heat equation. J. Math. Mech. 1969, 18, 1025–1042. [Google Scholar]

- Fushchych, W.I. On symmetry and particular solutions of some multidimensional physics equations. Algebraic-Theoretical Methods in Mathematical Physics Problems, Institute of Mathematics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

- Fushchych, W.I.; Serov, M.I.; Chopyk, V.I. Conditional invariance and nonlinear heat equations. Proceedings of the Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 1988, 9, 17–21. [Google Scholar]

- Popovych, R. No-go theorem on reduction operators of linear second-order parabolic equations. Proceedings of the Institute of Mathematics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2006, 3, 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bluman, G.W.; Anco, S.C. Symmetry and Integration Methods for Differential Equations, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-0-387-98654-8. [Google Scholar]

- Burde, G.I. Partially nonclassical method and conformal invariance in the context of the Lie group method. Symmetry 2024, 16, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, D.J.; Goard, J.M.; Broadbridge, P. Nonclassical solutions are non-existent for the heat equation and rare for nonlinear diffusion. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1996, 202, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniha, R.M. New non-Lie ansätze and exact solutions of nonlinear reaction-diffusion-convection equations. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1998, 31, 8179–8198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherniha, R.; Serov, M.; Pliukhin, O. Lie and Q-Conditional symmetries of reaction-diffusion-convection equations with exponential nonlinearities and their application for finding exact solutions. Symmetry 2018, 10, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.A.; Mansfield, E.L. Symmetry reductions and exact solutions of a class of nonlinear heat equations. Phys. D 1994, 70, 250–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, D.J.; Hill, J.M. Nonclassical symmetries for nonlinear diffusion and absorption. Stud. Appl. Math. 1995, 94, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, D.J.; Hill, J.M.; Broadbridge, P. Nonclassical symmetry reductions of the linear diffusion equation with a nonlinear source. IMA J. Appl. Math. 1994, 52, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibragimov, N.H. CRC Handbook of Lie Group Analysis of Differential Equations, Volume 1: Symmetries, Exact Solutions, and Conservation Laws; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. ISBN 978100341 9808.

- Zhdanov, R.Z.; Lahno, V.I. Conditional symmetry of a porous medium equation. Phys. D 1998, 122, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw-Hajek, B.H.; Edwards, M.P.; Broadbridge, P.; Williams, G.H. Nonclassical symmetry solutions for reaction-diffusion equations with explicit spatial dependence. Nonlinear Anal. 2007, 67, 2541–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.A.; Petrovskii, S.V.; Potts, J.R. The Mathematics Behind Biological Invasions, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-32042-7. [Google Scholar]

- Fick, A. Ueber diffusion. Ann. Phys. 1855, 170, 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünbaum, D.; Okubo, A. , Germany, 1994; Vol. 100, pp. 296–325. ISBN 978-3-642-50124-1.Aggregations. In Frontiers in Mathematical Biology. Lecture Notes in Biomathematics; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; ISBN 978-3-642-50124-1. [Google Scholar]

- Muskox: Circle Defense. Available online: https://home.nps.gov/gaar/learn/nature/muskox-circle-defense.htm#:~:text=When%20they%20see%20danger%20approaching,phalanx%20of%20heads%20and%20horns. (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Gompertz, B. On the nature of the function expressive of the law of human mortality, and on a new mode of determining the value of life contingencies. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. 1825, 115, 513–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw-Hajek, B.H.; Broadbridge, P. An analytic solution for a Gompertz-like reaction-diffusion model for tumour growth. Adv. Stud. Pure Math. 2020, 85, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | Maple is a trademark of Waterloo Maple Incorporated. The computations in this paper were performed using Maple™. |

| 2 | Please see our GitHub repository at Plenty and Edwards [34] for access to our Maple code. |

| Entry and | Designation as EN | |

|---|---|---|

| EN | ||

| EN if |

| Entry | Designation |

|---|---|

| 1 | n-L and ★ |

| 2 | n-L iff ★ if |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).