1. Introduction

Weight reduction in automotive design is a key strategy to reduce fuel consumption and CO2 emissions. Advanced High Strength Steels (AHSS), particularly press-hardened steels (PHS), play a critical role due to their exceptional strength-to-weight ratio. PHS grades, standardly microalloyed with Ti and B, undergo hot forming followed by rapid quenching to produce a martensitic microstructure.

Hydrogen-induced delayed fracture (HIDF) poses a significant reliability concern in PHS applications. This phenomenon, driven by hydrogen ingress and localized stress accumulation, is governed by mechanisms such as hydrogen-enhanced decohesion (HEDE), hydrogen-enhanced localized plasticity (HELP), and hydrogen-stabilized strain-induced vacancies (HESIV). Microalloying with Nb and V introduces fine precipitates that serve as irreversible hydrogen traps, potentially mitigating HIDF.

This study compares a commercially produced Ti-Nb-V microalloyed PHS with a standard Ti-microalloyed 22MnB5 steel. Hydrogen transport properties, trapping energetics, and mechanical degradation under hydrogen exposure were evaluated to elucidate the role of complex carbide dispersions in enhancing embrittlement resistance.

Environmental impact has become a critical consideration across many sectors, particularly in passenger car engineering. In this context, reducing fossil fuel consumption and CO₂ emissions is closely linked to decreasing vehicle weight. Lightweighting can be achieved by reducing the thickness of sheet metal components, which in turn requires the use of advanced materials capable of meeting increasingly stringent safety and durability standards.

Advanced High Strength Steels (AHSS) represent a promising solution to these demands, offering enhanced strength combined with good formability. AHSS is a new generation of steels that includes Dual Phase, Complex Phase, Ferritic-Bainitic, Martensitic, Transformation-Induced Plasticity (TRIP), Hot-Formed, Twinning-Induced Plasticity (TWIP), and Press Hardened Steels (PHS).

PHS, in particular, are standardly microalloyed with

manganese, boron, and titanium. Thereby solute boron provides hardenability by suppressing ferrite nucleation at the austenite grain boundary while titanium protects boron from reacting with residual nitrogen contained in the steel. PHS steels achieve ultra-high strength by quenching immediately after hot forming with a cooling rate of around 50 K/s resulting in a fully martensitic microstructure. They are commonly used for structural components such as A- and B-pillars or cross members. In this class of steels, nano-sized precipitates of microalloy carbides can play a crucial role in enhancing performance by optimizing the martensitic microstructure [

1]. These particles are known to refine grain structure, improve microstructural uniformity, and serve as hydrogen traps, potentially increasing resistance to delayed cracking [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Delayed fracture, associated with hydrogen embrittlement, results from the combined effects of hydrogen presence in the steel and applied or residual stresses. Because hydrogen requires time to diffuse and accumulate locally within the metal lattice, failure may occur after a delay following hydrogen absorption. Three principal mechanisms have been proposed to explain delayed fracture: hydrogen-enhanced grain boundary decohesion (HEDE), hydrogen-enhanced local plasticity (HELP), and hydrogen-enhanced strain-induced vacancy (HESIV) formation.

The HEDE mechanism suggests that hydrogen weakens grain boundary cohesion by segregating at these boundaries, leading to intergranular fracture. This mechanism may also extend to interfaces between the matrix and inclusions—features that typically serve as dimple nucleation sites—thus producing fractures with both ductile and brittle characteristics. The HELP mechanism, on the other hand, posits that dislocation mobility is enhanced due to the interaction between the elastic stress fields of dislocations and those generated by dissolved hydrogen atoms. This interaction facilitates microcrack propagation and leads to intense localized plasticity, often observed beneath quasi-cleavage transgranular fractures. Lastly, the HESIV mechanism proposes that hydrogen stabilizes supersaturated vacancies, promoting void nucleation and crack growth [

7].

This study investigates the susceptibility to hydrogen-induced delayed fracture in a commercially available Ti-Nb-V microalloyed PHS, compared to a reference steel microalloyed only with Ti. Both materials are designated as PHS 1500 grades. The study specifically examines the influence of niobium-based precipitates on hydrogen absorption, as well as the potential effects of vanadium and its associated particles. Dedicated laboratory tests were employed to evaluate hydrogen diffusivity within the lattice and to determine the activation energies of present trapping sites. Mechanical tests assessed material performance under various exposure conditions. Finally, an accelerated corrosion test using a salt spray chamber was conducted to simulate potential hydrogen absorption during the vehicle’s service life. Results indicate that increased microstructural refinement and the presence of precipitates can enhance resistance to hydrogen embrittlement. However, no evidence of hydrogen uptake during the accelerated corrosion test was detected with the measurement methods available.

2. Materials and Methods

Two 22MnB5 steels with different microalloying strategies—one using the standard B-Ti concept and the other using a multiple microalloy concept with B-Ti-Nb-V (

Table 1)—were evaluated in this study. Both steels, with a thickness of 1.2 mm, originated from industrial production and were AlSi-coated (AS40). Sheets were cut from the coils and heat treated in a laboratory furnace. A standard thermal cycle, representative of automotive hot stamping processes, was applied by austenitizing at 915 °C for 8 minutes. Part of the samples also underwent a paint baking heat treatment, simulating industrial conditions, by holding the as-quenched steel at 170 °C for 20 minutes.

In both steels, the Ti:N ratio is approximately 10:1, significantly exceeding the stoichiometric ratio of 3.4:1. This promotes the primary precipitation of coarse TiN particles. Microstructural characterization confirmed the presence of such coarse TiN precipitates [

8]. However, a significant amount of Ti (estimated at ~0.02 wt%) remains available for the precipitation of fine TiC particles. Most Nb and V form carbides, which were identified as mixed TiNbV carbides as detailed in [

8].

The following sections describe the experimental methodologies used in this study. These methods enabled the evaluation of differences in hydrogen diffusivity, hydrogen trapping activation energy, and mechanical performance between the two alloy designs. Samples for mechanical testing were laser cut before heat treatment using geometries defined in the relevant standards. An additional series of hydrogen measurements was carried out to evaluate hydrogen content before and after heat treatment.

2.1. Hydrogen Diffusivity

Electrochemical permeation tests were performed to determine the effective hydrogen diffusion coefficient, following the procedure outlined in [

9], using HELIOS 2 equipment [

10]. Tests were conducted at various temperatures after standard heat treatment, both with and without coating on the exit (detection) side, for both the Ti-only and Ti-Nb-V steels. The effective hydrogen diffusion coefficient was calculated using the 63% method, defined by Equation (1):

where:

D is the effective hydrogen diffusion coefficient,

L is the specimen thickness,

t₆₃ is the time required for the hydrogen flux at the exit surface to reach 63% of the steady-state value.

2.2. Activation Energies of Hydrogen Trapping Sites

The diffusion coefficients measured at different temperatures were used to estimate the binding energies of low-energy hydrogen traps. A linear regression fitting on logarithmic coordinates was applied, based on the Arrhenius-type Equation (2) [

11]:

where:

A is a pre-exponential factor,

B is the apparent activation energy (in J/mol),

R is the universal gas constant,

T is the absolute temperature.

The parameters

A and

B can be expressed as:

where:

D₀ is the pre-exponential diffusion coefficient,

Nₗ is the density of lattice sites per unit volume,

Nᵣ is the density of trap sites per unit volume,

E_b is the binding energy of traps,

E_l is the activation energy for hydrogen movement between lattice sites.

Alternatively, Temperature Programmed Desorption (TPD) tests were used to study the physical desorption behavior as a function of temperature. Sheet specimens (12 × 30 mm²) were hydrogen-charged during heat treatment in a laboratory furnace under controlled humidity conditions. These were subsequently heated from room temperature to 500 °C at rates ranging from 1 to 7 °C/min. TPD curves were analyzed using Gaussian peak deconvolution to identify trap energies [

12].

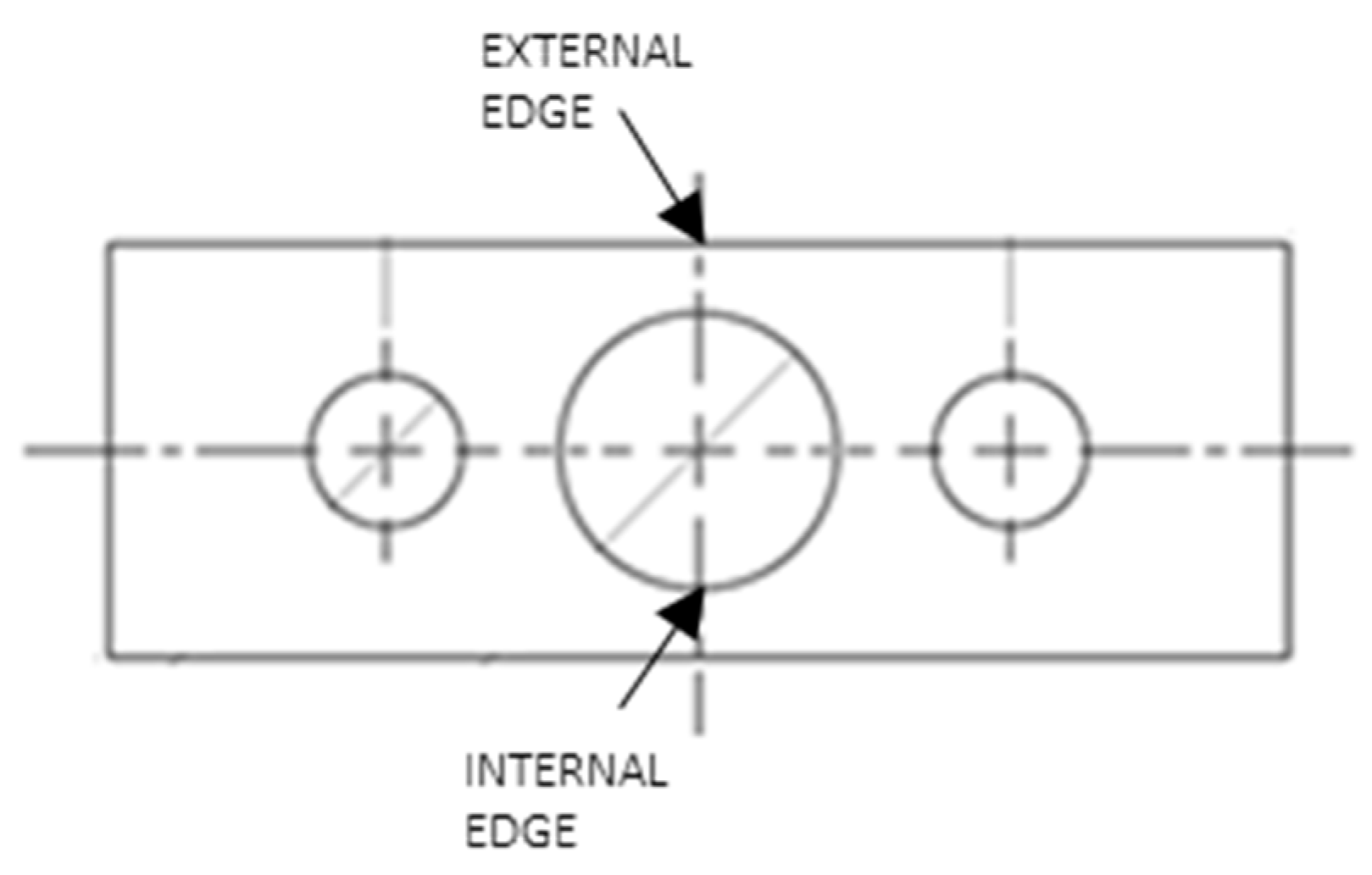

2.3. Mechanical Behavior

Slow Strain Rate Tests (SSRTs) were conducted according to [

13] to correlate hydrogen absorption with mechanical degradation, specifically reductions in strength and elongation at break. The test specimen geometry followed the guidelines in [

14] and is shown in

Figure 5 (

ensure the figure is included).

Tests were conducted on hydrogen-precharged specimens. Some samples were charged via hot furnace charging with varied furnace dew points, while others underwent standard heat treatment (915 °C for 8 minutes) followed by cathodic charging. Cathodic charging parameters—such as electrolyte composition and current density—were varied to evaluate their effects. All samples underwent a paint baking simulation (170 °C for 20 minutes) prior to testing. This treatment is known to reduce diffusible hydrogen content, as the AlSi coating acts as a diffusion barrier up to approximately 75 °C; at higher temperatures, hydrogen effusion begins [

15].

This reduction in hydrogen content was considered when designing charging conditions for mechanical tests. A constant strain rate of 10⁻³ mm/s was applied. After testing, the diffusible hydrogen content was measured via hot gas extraction at 265 °C—a temperature selected to minimize the influence of coating decomposition, as suggested in [

15].

The experimental data were fitted using a regression model based on Equation (5):

where:

A is a property related to mechanical performance (e.g., elongation or strength),

C_H is the diffusible hydrogen content,

m₁–m₄ are fitting parameters.

3. Results

3.1. Hydrogen Diffusivity

Before heat treatment, the hydrogen diffusion coefficients of 22MnB5 and NbV steels are nearly identical and lower than historical reference values—likely due to higher titanium content and finer prior austenite grain size. After heat treatment, however, the diffusion coefficient of the NbV steel is significantly lower, indicating the influence of niobium addition.

Table 2 summarizes the hydrogen diffusion coefficients at 30 °C after heat treatment (915 °C × 8 min + 170 °C × 20 min), comparing values for bare steel and steel with AS40 coating on the exit side to assess the coating’s barrier effect.

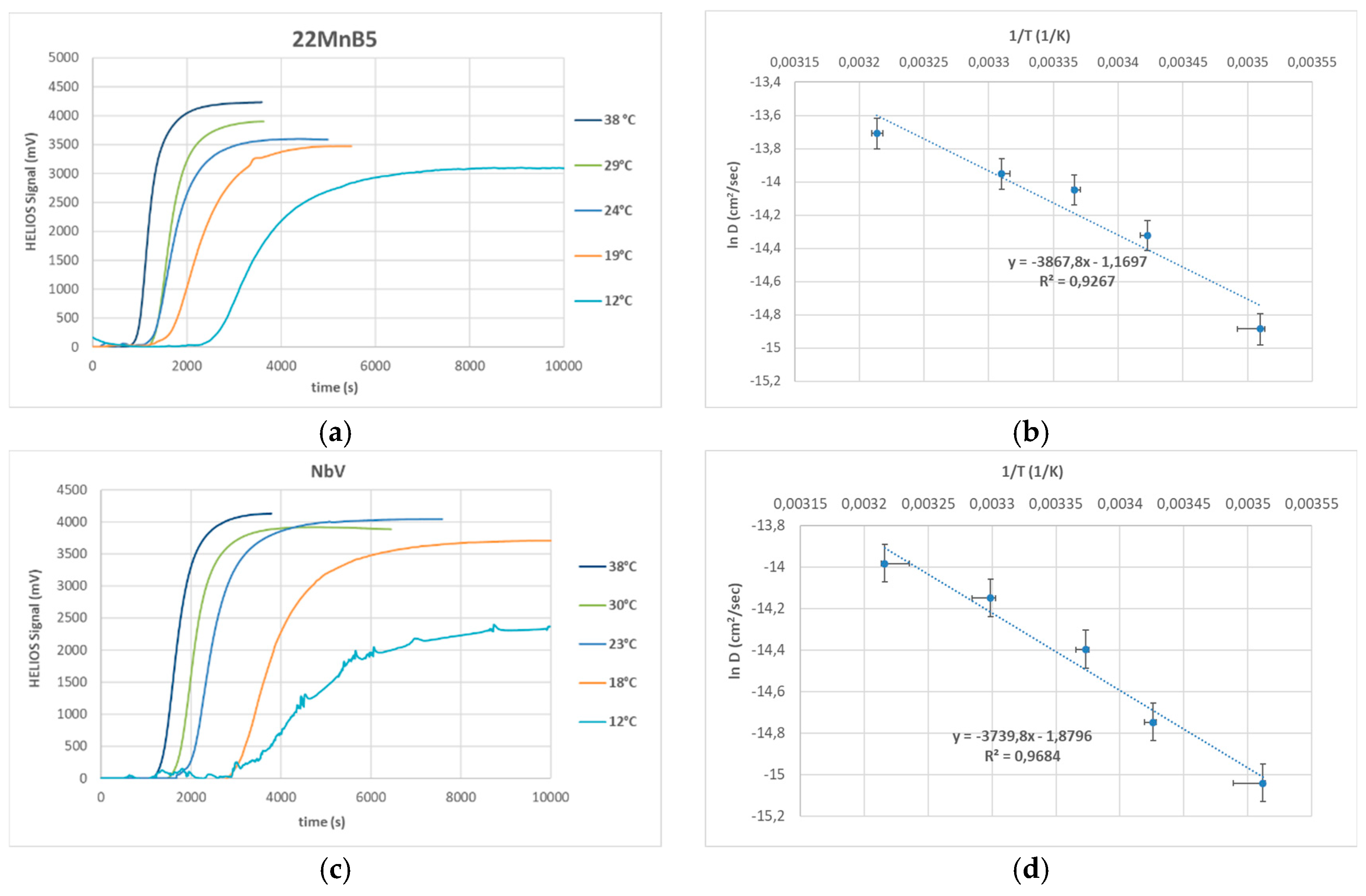

3.2. Activation Energies of Hydrogen Trapping Sites

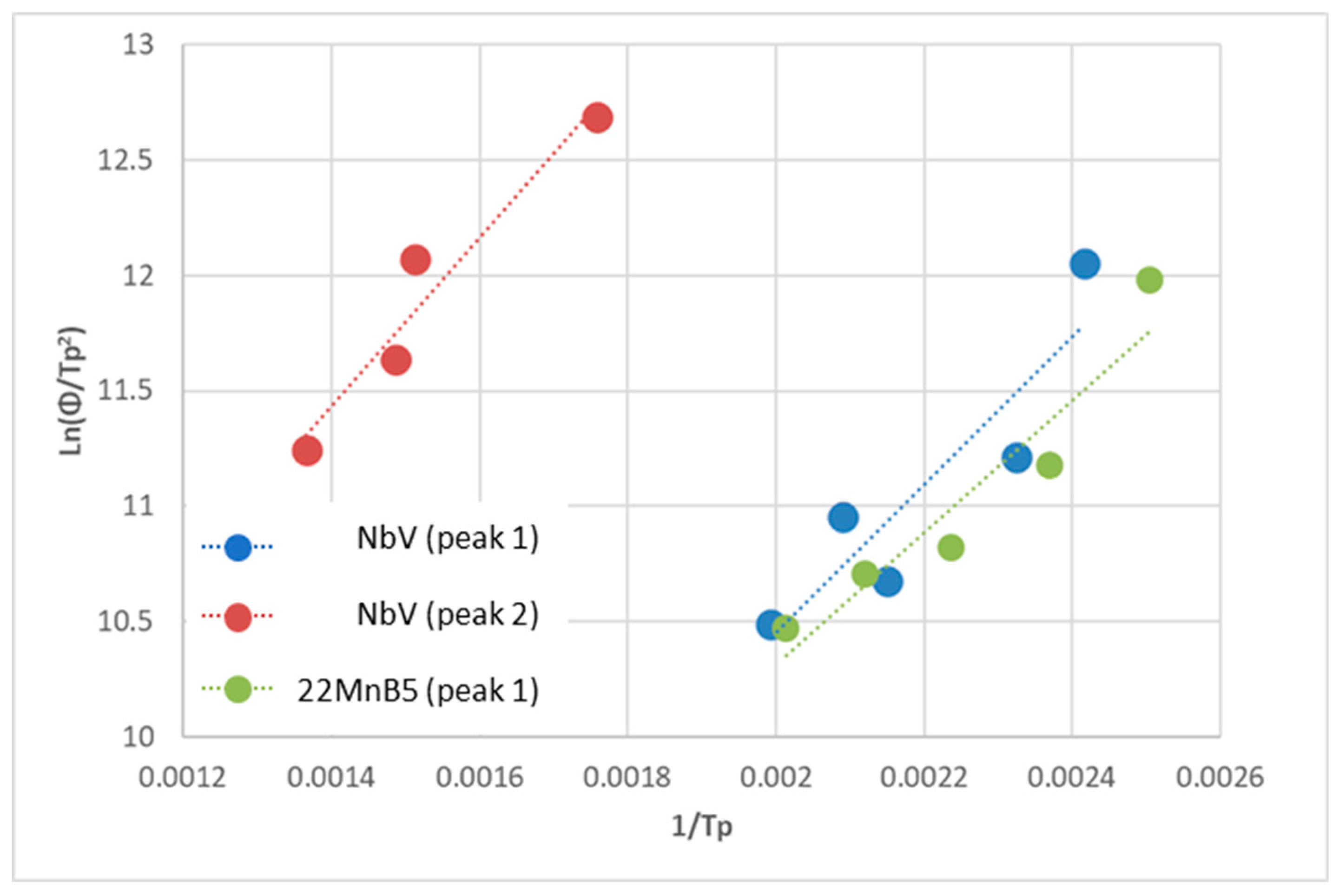

Electrochemical permeation tests were repeated at various temperatures on heat-treated (quenched + paint baked) steels. The AS40 coating was removed prior to testing. Activation energies for low-energy, reversible hydrogen traps were determined following the method described in

Section 2.2. Results are illustrated in

Figure 1. Error bars on the x-axis reflect temperature variation; those on the y-axis represent instrument error during thickness measurement. The estimated activation energies were 26.5 kJ/mol for 22MnB5 and 25.4 kJ/mol for the NbV variant.

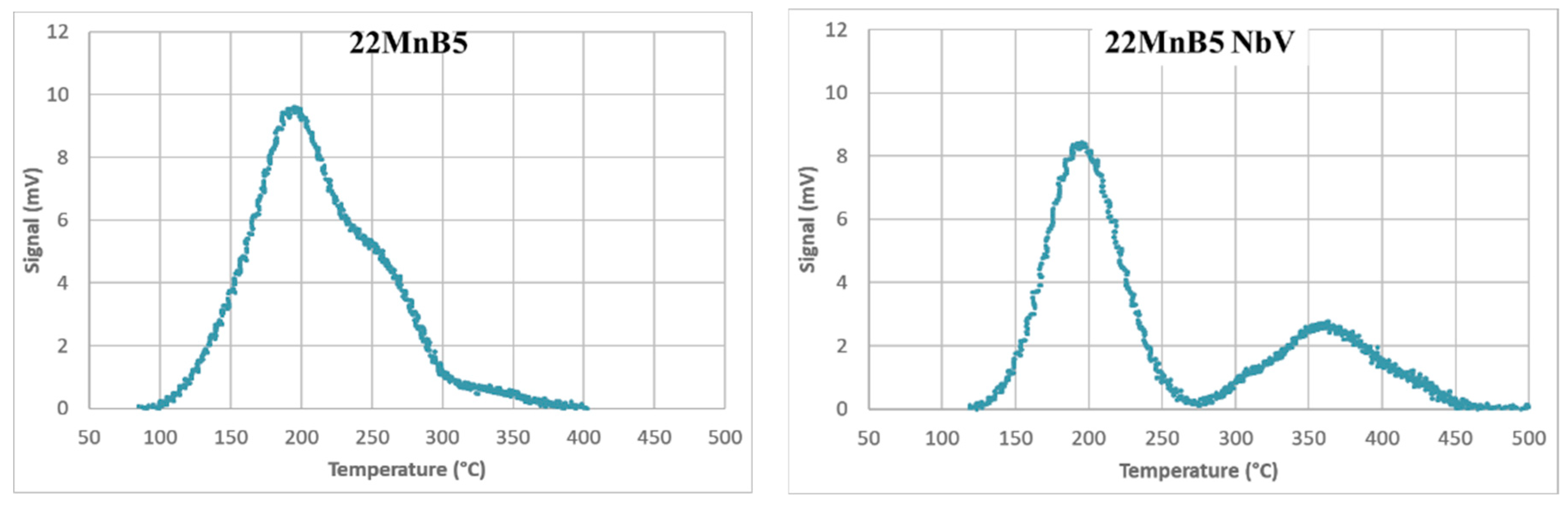

Temperature Programmed Desorption (TPD) was then used to characterize hydrogen traps. After hot furnace hydrogen charging, AS40 coating was removed. Specimens were subjected to heating rates (Φ) from 1–7 °C/min. The hydrogen desorption signal was analyzed to determine peak temperatures via Gaussian deconvolution (

Figure 2).

TPD regression analysis is shown in

Figure 3.

Table 3 lists the extracted activation energies. The first peak is observed in both steels and corresponds to traps at grain boundaries and dislocations. A second, higher-energy peak is visible only in the NbV steel and is attributed to hydrogen trapping at microalloy precipitates.

3.3. Mechanical Behavior

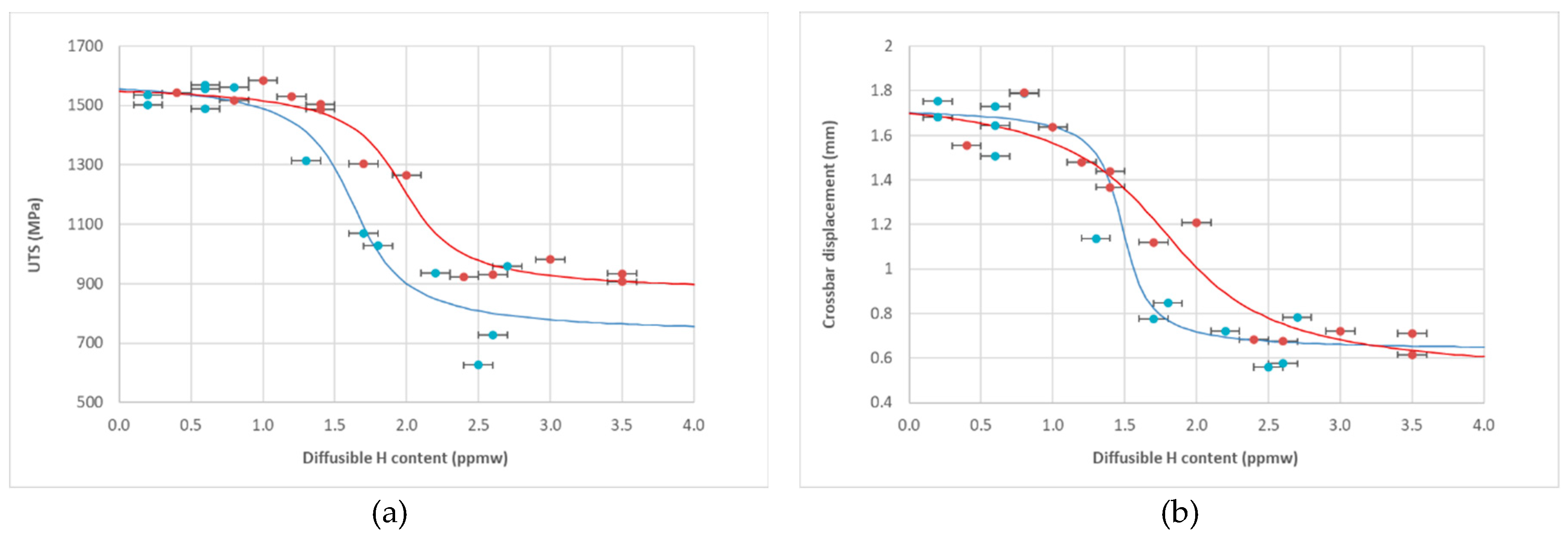

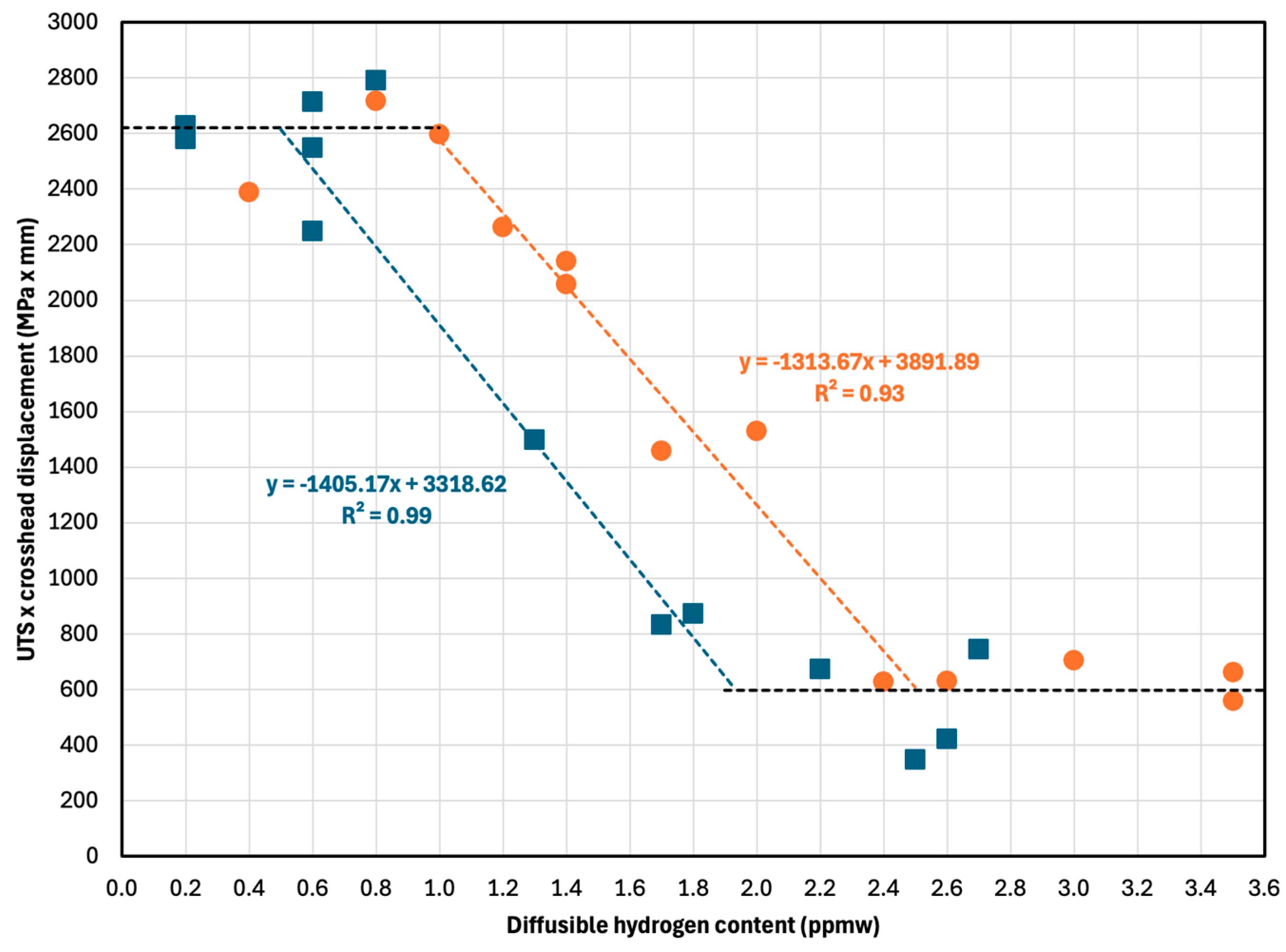

Figure 4 displays the ultimate tensile strength (a) and crosshead displacement at break (b) versus diffusible hydrogen content. Due to sample geometry (SEP 1970:2011), an extensometer could not be used.

Two performance plateaus are evident. Up to ~1.0 ppmw hydrogen, both steels retain full ductility and strength. Above ~2.5 ppmw, full embrittlement occurs. The NbV steel exhibits a more gradual transition and a higher critical hydrogen content, as fitted using Equation (5) (see

Section 2.3). The critical hydrogen content (corresponding to a 30% drop in mechanical performance) was:

22MnB5: 1.7 ppmw

NbV: 2.2 ppmw

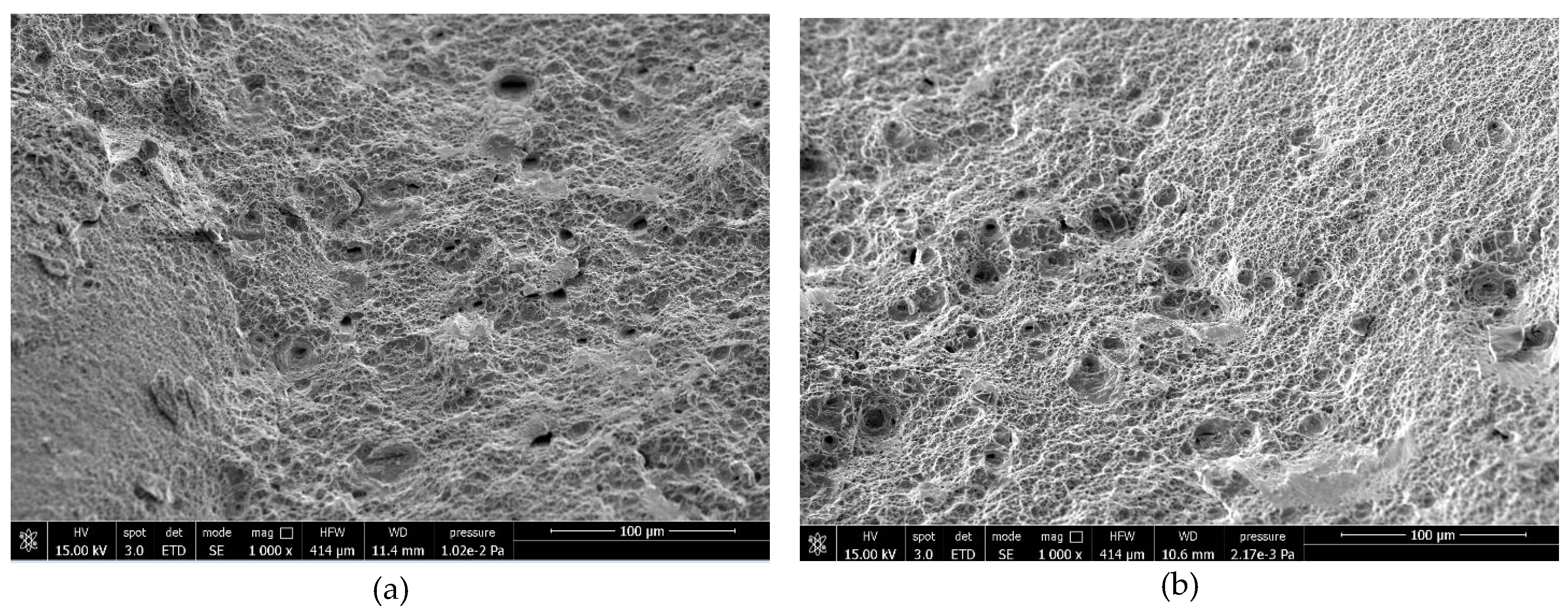

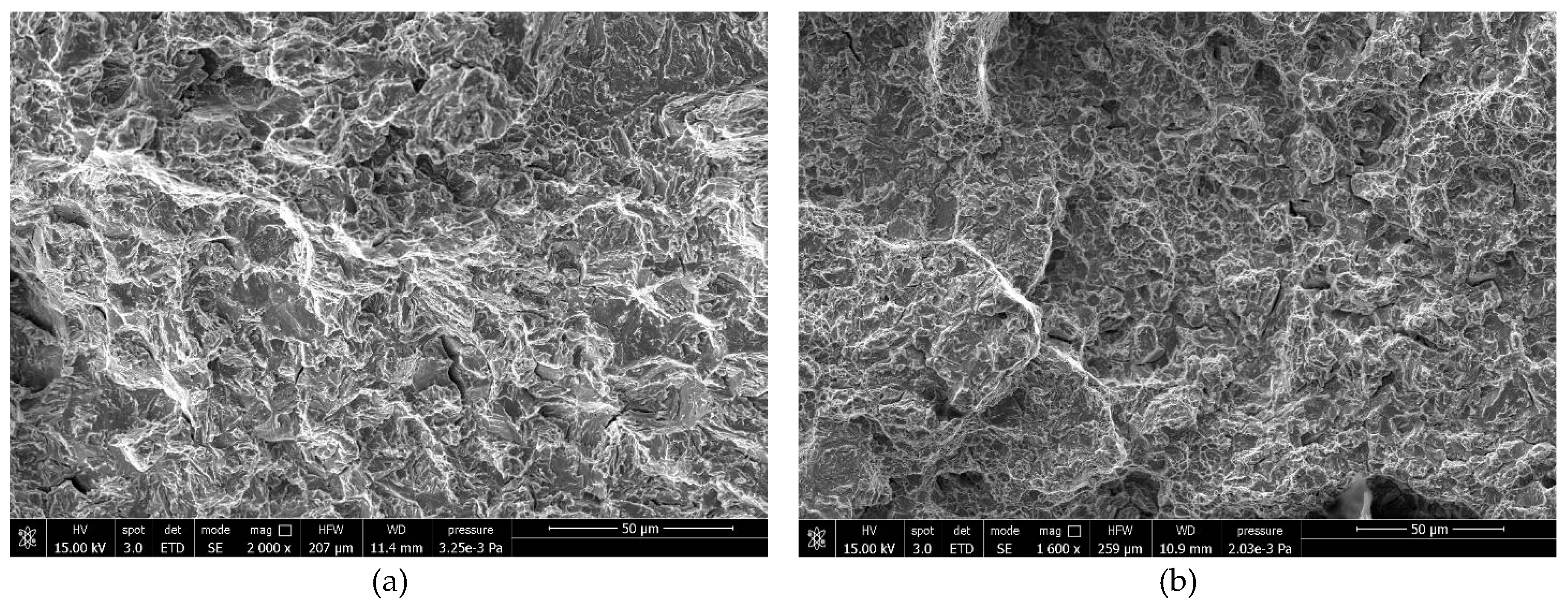

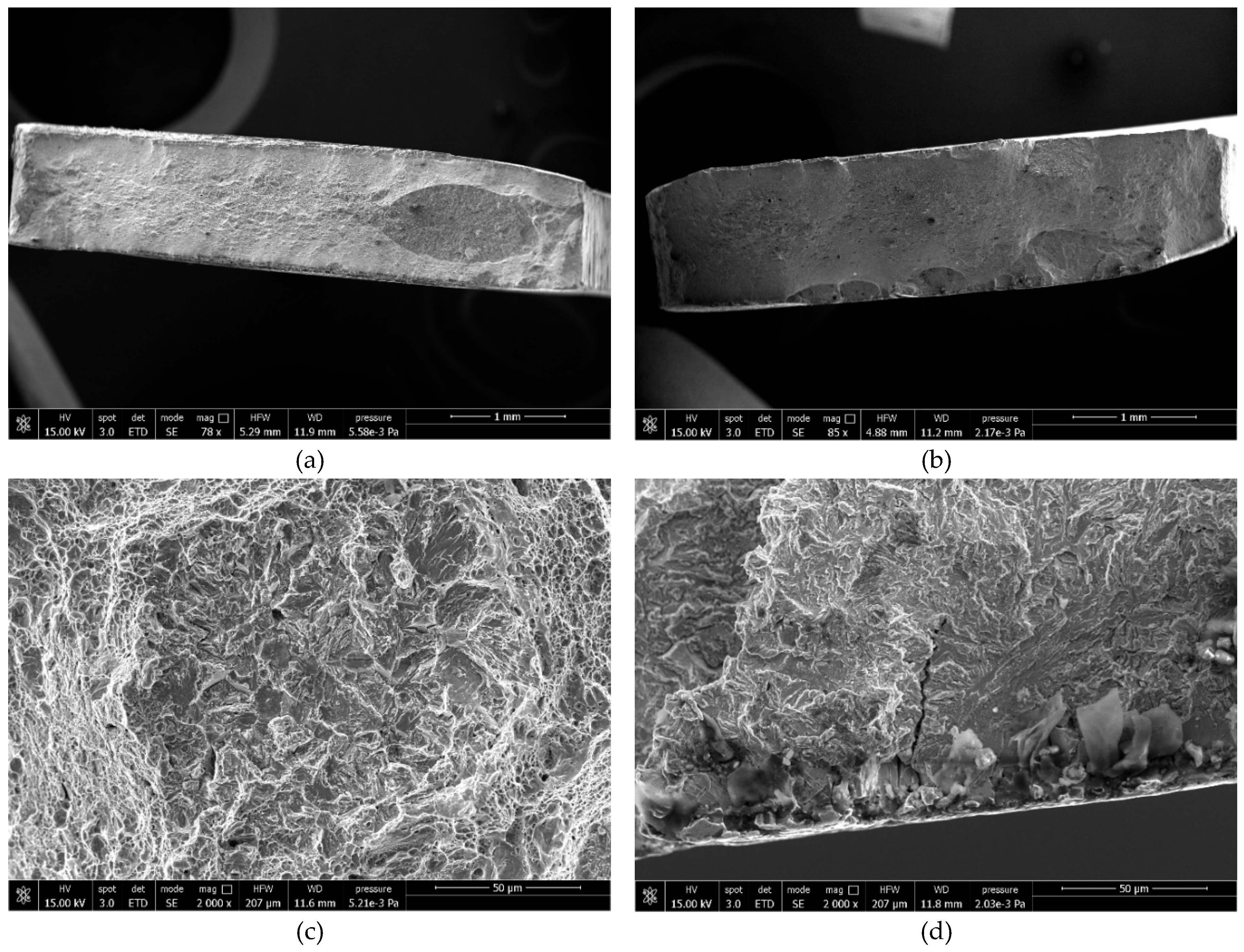

Fractographic SEM analysis was performed on fracture surfaces at various hydrogen levels. For low hydrogen content, both steels show predominantly ductile (dimpled) fracture (

Figure 6), while high hydrogen content results in quasi-cleavage and intergranular fracture (

Figure 7).

Figure 5.

Edges identification for fractographic analysis.

Figure 5.

Edges identification for fractographic analysis.

Figure 6.

Fracture surfaces of samples with low hydrogen level, (a) 22MnB5 external edge and (b) NbV internal edge.

Figure 6.

Fracture surfaces of samples with low hydrogen level, (a) 22MnB5 external edge and (b) NbV internal edge.

Figure 7.

Fracture surfaces of samples with high hydrogen level, (a) 22MnB5 external edge and (b) NbV at the core.

Figure 7.

Fracture surfaces of samples with high hydrogen level, (a) 22MnB5 external edge and (b) NbV at the core.

At ~1.7 ppmw hydrogen (critical range), mixed fracture was observed in both steels (

Figure 8). In the NbV steel, brittle regions were localized near the AlSi interdiffusion layer, with the midsection remaining ductile.

4. Discussion

Hydrogen has a detrimental effect on both tensile strength and ductility. This is particularly important for automotive applications, where energy absorption (UTS × displacement) is critical.

Figure 9 shows that post-embrittlement performance drops to ~22% of the original. The transition region is linear for both steels, but the NbV variant tolerates ~0.5 ppmw more hydrogen.

Strain rate effects, as shown by Momotani et al. [

26], suggest hydrogen accumulation at prior austenite grain boundaries (PAGBs) during low strain rate testing. With lower hydrogen diffusivity (as in NbV steel), embrittlement of PAGBs is delayed. Under constant load (delayed fracture) conditions, grain size becomes decisive [

1]. Niobium microalloying, as previously shown [27], promotes finer grain size by pinning effects of nano-carbide precipitates.

In the ductile range, hydrogen enhances dislocation mobility (HELP mechanism), suppressing work hardening. At higher concentrations, brittle fracture dominates due to HELP and HEDE mechanisms acting locally in areas of stress concentration (e.g., at the circular notch in SEP samples). PAGBs, saturated with hydrogen, become preferential fracture paths. Grain refinement dilutes hydrogen across more boundaries, delaying embrittlement [

1].

The nearly constant 0.5 ppmw offset between steels implies effective trapping in the NbV steel, attributed to nano-sized carbides. These particles (spherical, 8 nm average, mixed Nb-Ti-V) number ~3000–3500/µm³ and trap ~0.6 ppmw hydrogen, aligning with the measured difference.

The observed trapping energy (30.5 kJ/mol) matches literature for incoherent precipitate interfaces [

17,

21]. Since press hardening conditions produce incoherent interfaces, short-range trapping dominates [29].

Additionally, most vanadium remains dissolved during press hardening but may form VC particles during post-processing (e.g., welding). VC precipitates can trap hydrogen [34], but their effect here is minimal due to bake treatment. Ferrous carbides from bake treatment do not measurably trap hydrogen, consistent with [35].

5. Conclusions

Additional microalloying with Nb and V in Ti-based PHS promotes the formation of ultrafine, mixed NbTiV carbides.

These particles refine prior austenite grain size, contributing to geometric dilution of hydrogen and improved crack resistance.

The NbV microalloyed steel tolerates ~0.5 ppmw more diffusible hydrogen than the Ti-only variant, a difference attributed to effective hydrogen trapping by nano-sized carbides.

The hydrogen trapping potential was validated by estimating particle number density and applying known hydrogen surface coverage values.

This added hydrogen tolerance could allow automotive manufacturers to forgo dry-air systems in hot press forming, reducing natural gas use and CO₂ emissions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A. and R.V.; methodology, L.B., S.C., M.T.; validation, L.B., H.M., and M.T.; formal analysis, L.B., S.C.; writing—original draft, L.B.; writing—review & editing, L.B., S.C., R.V., H.M.; project administration, F.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mohrbacher, H. Property Optimization in As-Quenched Martensitic Steel by Molybdenum and Niobium Alloying. Metals (Basel) 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Gui, L.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, Y.; Ma, M.; Lu, H.; Tan, K.; Chiu, P.-H.; Guo, A.; Bian, J.; Yang, J.-R.; et al. Study on the Improving Effect of Nb-V Microalloying on the Hydrogen Induced Delayed Fracture Property of 22MnB5 Press Hardened Steel. Mater Des 2023, 227, 111763. [CrossRef]

- Cho, L.; Seo, E.J.; Sulistiyo, D.H.; Jo, K.R.; Kim, S.W.; Oh, J.K.; Cho, Y.R.; de Cooman, B.C. Influence of Vanadium on the Hydrogen Embrittlement of Aluminized Ultra-High Strength Press Hardening Steel. Materials Science and Engineering A 2018, 735, 448–455. [CrossRef]

- Mohrbacher, H. Martensitic Automotive Steel Sheet - Fundamentals and Metallurgical Optimization Strategies. Adv Mat Res 2014, 1063, 130–142. [CrossRef]

- Jian, B.; Wang, L.; Mohrbacher, H.; Lu, H.Z.; Wang, W.J. Development of Niobium Alloyed Press Hardening Steel with Improved Properties for Crash Performance. Adv Mat Res 2014, 1063, 7–20. [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, D.; Gerber, T.; Castro Müller, C.; Stille, S.; Banik, J. Process Stability and Application of 1900 MPa Grade Press Hardening Steel with Reduced Hydrogen Susceptibility. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng 2022, 1238, 012013. [CrossRef]

- Mohrbacher, H.; Senuma, T. Alloy Optimization for Reducing Delayed Fracture Sensitivity of 2000 MPa Press Hardening Steel. Metals 2020, 10, 853;. [CrossRef]

- Mohrbacher, H.; Bacchi, L.; Ischia, G.; Gialanella, S.; Tedesco, M.; D’Aiuto, F.; Valentini, R. Characterization of Nanosized Carbide Precipitates in Multiple Microalloyed Press Hardening Steels. Metals 2023, 13(5), 894. [CrossRef]

- ISO 17081:2014.

- PATENT HELIOS.

- Skjellerudsveen, M.; Akselen, O.M.; Olden, V.; Johnsen, R.; Smirnova, A. Effect of Microstructure and Temperature on Hydrogen Diffusion and Trapping in X70 grade Pipeline Steel and its Weldments. Mat. Science, Engineering 2010, Corpus ID: 55117489.

- J.Y.Lee W.Y.Choo. Thermal analysis of trapped hydrogen in pure iron. Metallurgical Transaction, 13A, 1982. [CrossRef]

- ASTM G129.

- SEP 1970:2011.

- Georges, C; Mataigne, J.M. Absorption/Desorption of Diffusible Hydrogen in Aluminized Boron Steel. ISIJ International 2013. [CrossRef]

- Kissinger, H.E. Reaction kinetics in Differential Thermal Analysis. Analytical Chemistry 1957, pp. 1702-1706.

- Wallaert, E.; Depover, T.; Arafin, M.; Verbeken, K. Thermal Desorption Spectroscopy Evaluation of the Hydrogen-Trapping Capacity of NbC and NbN Precipitates. The Minerals, Metals & Materials Society and ASM International 2014. [CrossRef]

- S.S. Hansen, J.B. Vander Sande, M. Cohen. s.l. Niobium Carbonitride Precipitation and Austenite Recrystallization in Hot-Rolled Microalloyed Steels. Metallurgical Transaction A, 1980, Vol. 11, pp. 387-402.

- Wasim M, Djukic MB, Ngo TD. Influence of hydrogen-enhanced plasticity and decohesion mechanisms of hydrogen embrittlement on the fracture resistance of steel. Engineering Failure Analysis, vol. 123, 2021, 105312. ISSN 1350-6307. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Wan, J.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, J.; Huang, F.; Huang, Y.; Li, X. Dual role of nanosized NbC precipitates in hydrogen embrittlement susceptibility of lath martensitic steel. corrosion science 2019. [CrossRef]

- Schwedler, O. Consideration of hydrogen transport in press-hardened 22MnB5. Materialprufung 2015. [CrossRef]

- Shi, R.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Gao, L.; Yang, X.; Qiao, L., Pang, X. Atomic-scale investigation of deep hydrogen trapping in NbC/α-Fe semi-coherent interfaces. Acta Materialia 2020. [CrossRef]

- Cuddy L and Raley J, Austenite grain coarsening in microalloyed steels. Met. Trans., A14 No. 10 1983:1989”.

- Correa de Souza, J.H.; Tolotti de Almeida, D.; Mohrbacher, H.; Suikkanen, P. Development of Process Techniques for Press hardening of Thick Plates. Conference paper 2018. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325741784.

- Lin, L.; Li, B.; Zhu, G.; Kang, Y.; Liu, R. Effect of niobium precipitation behavior on microstructure and hydrogen induced cracking of press hardening steel 22MnB5. Mat. Science & Eng. A 2018. [CrossRef]

- Yuji Momotani, Akinobu Shibata, Daisuke Terada, Nobuhiro Tsuji, Effect of strain rate on hydrogen embrittlement in low-carbon martensitic steel, International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, Volume 42, Issue 5, 2017, Pages 3371-3379. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).