Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

10 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

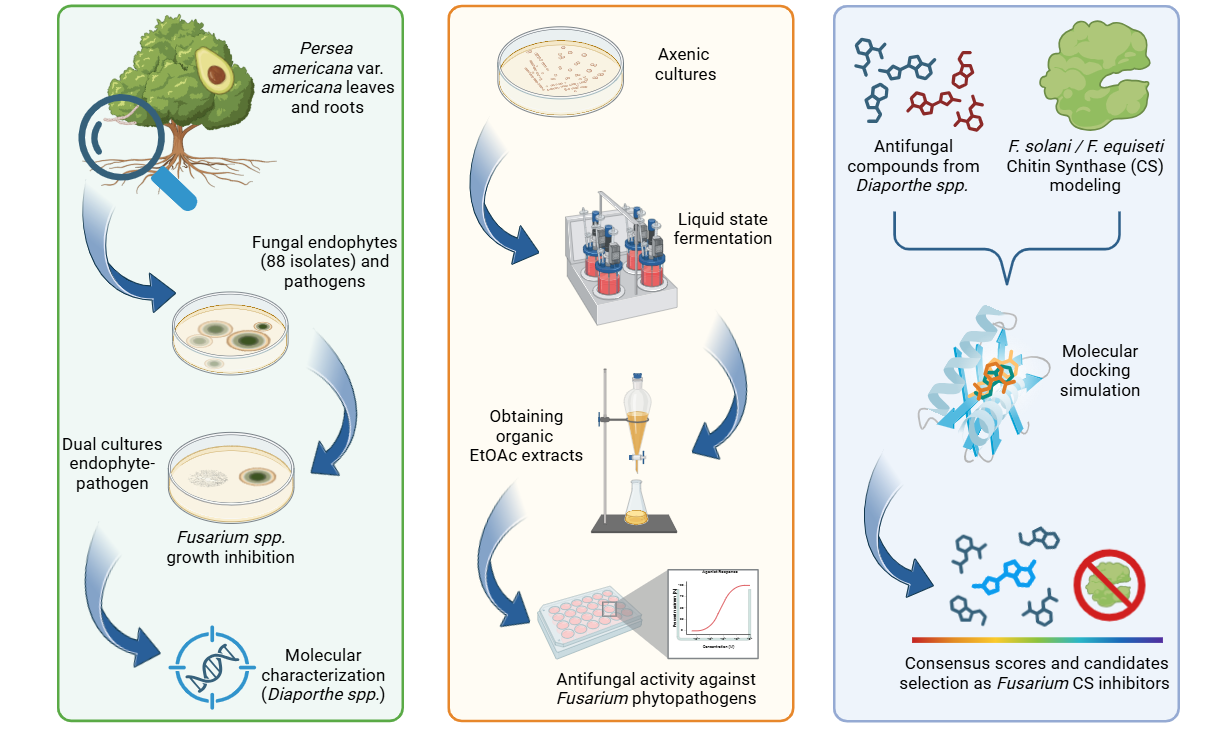

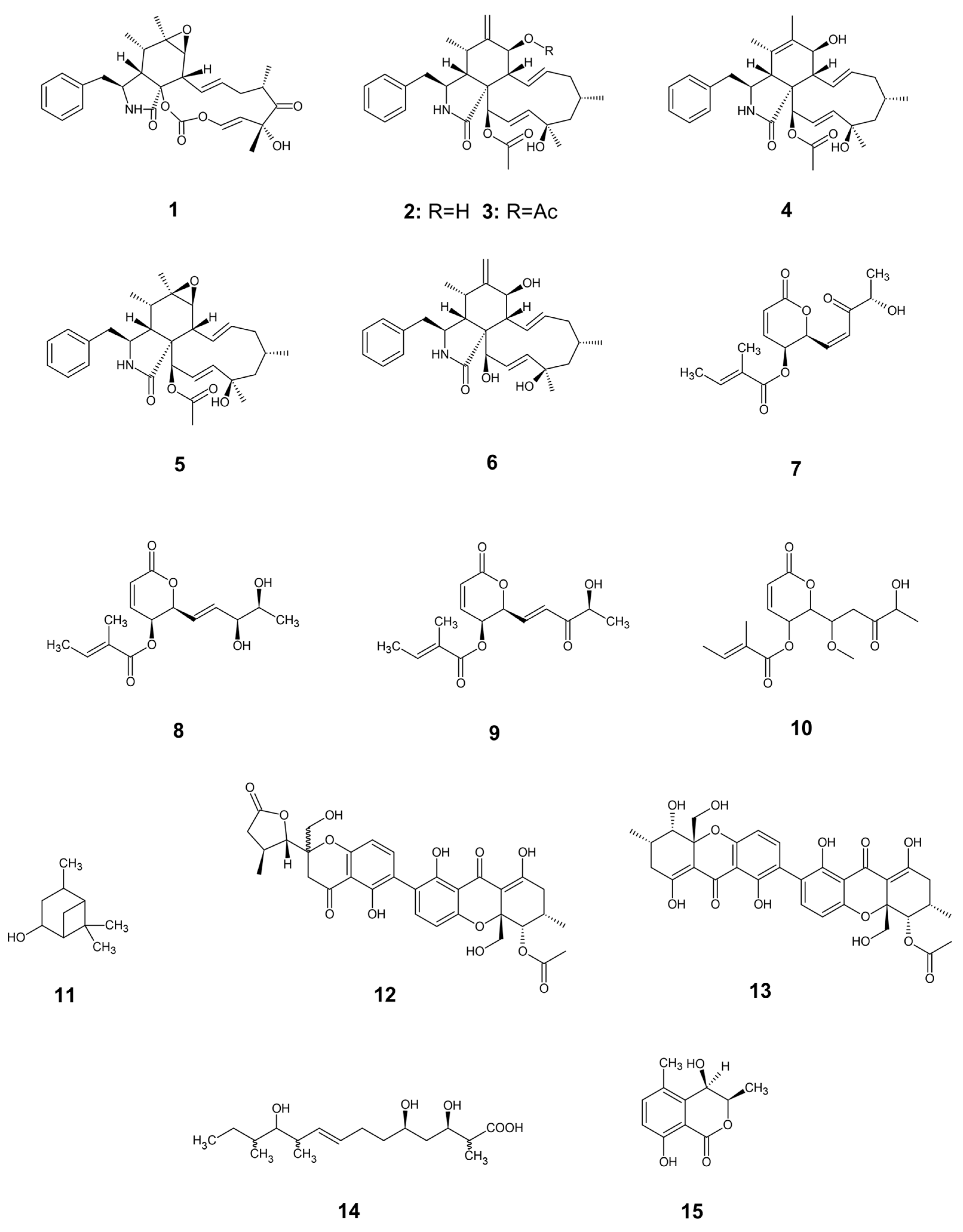

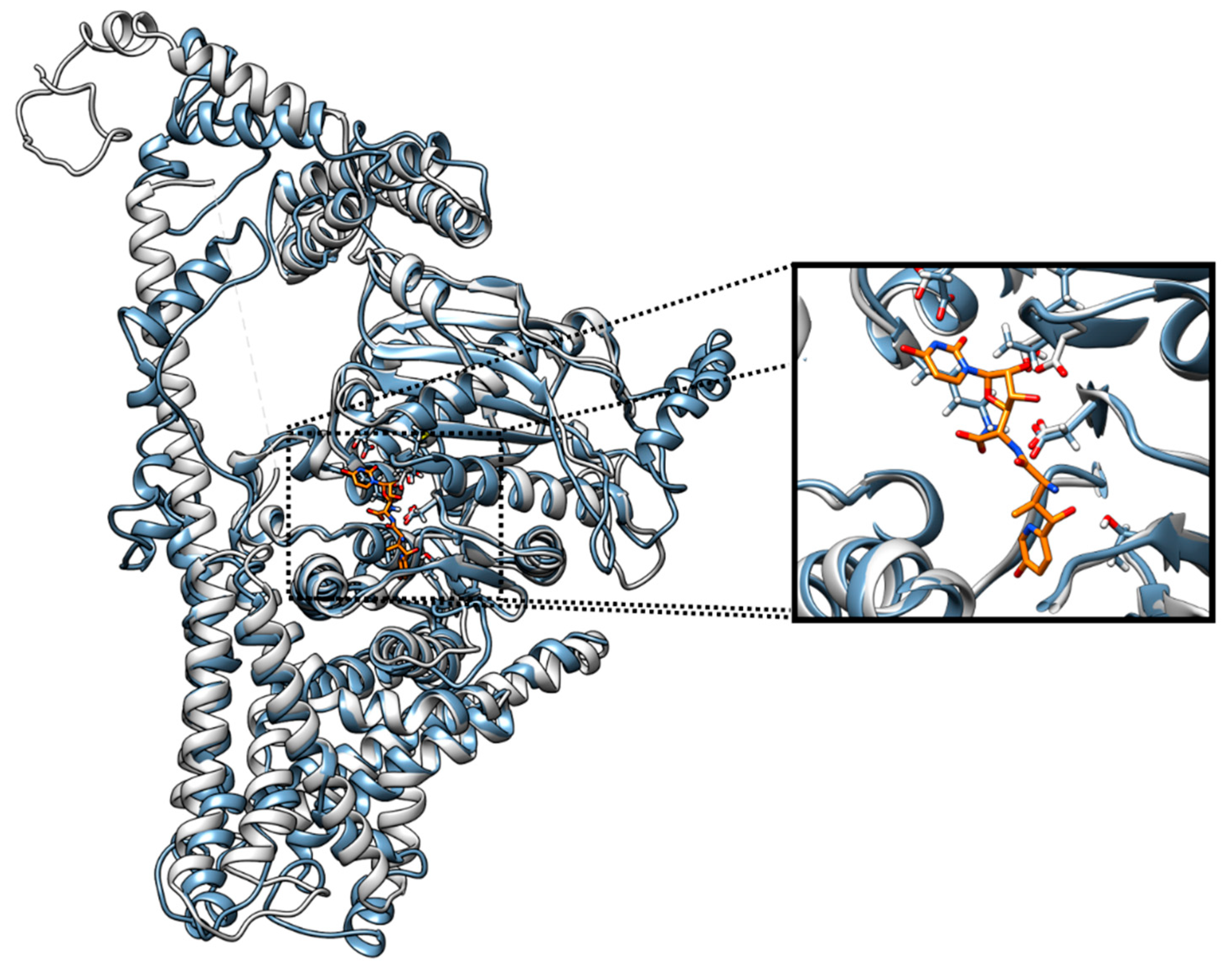

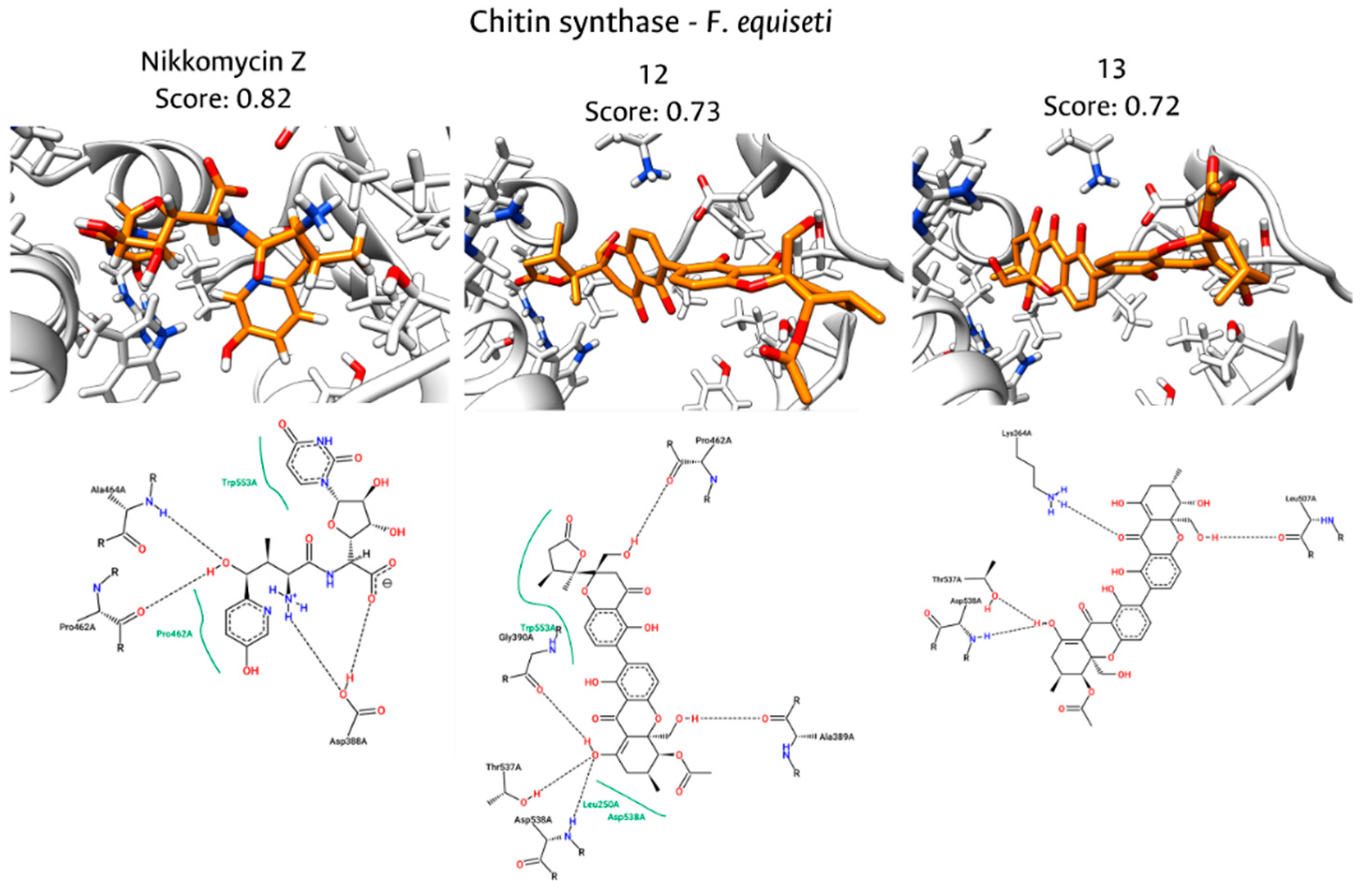

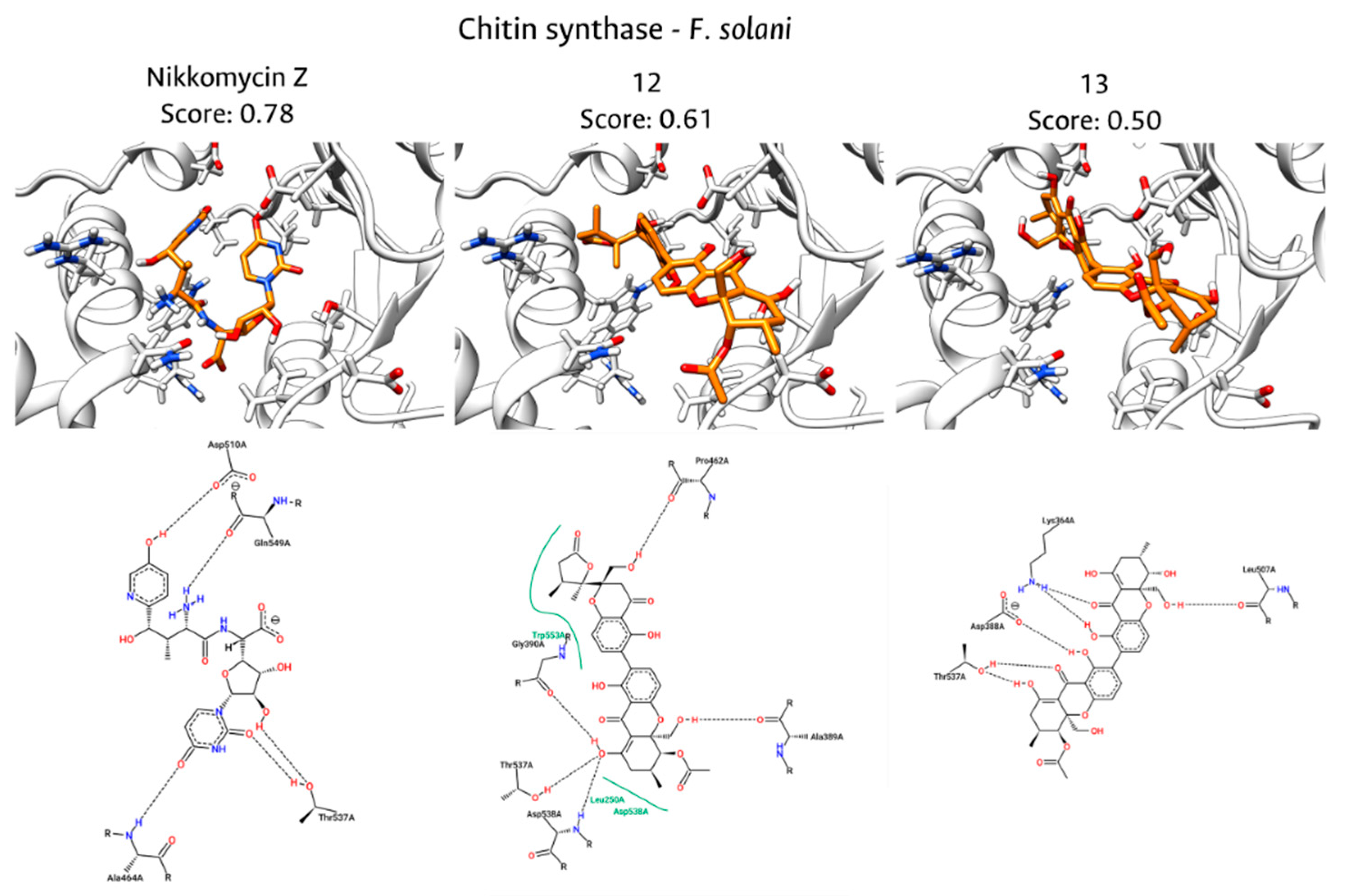

Fungal endophytes have emerged as a promising source of bioactive compounds with potent antifungal properties for plant disease management. This study aimed to isolate and characterize fungal endophytes from Antillean avocado (Persea americana var. americana) trees in the Colombian Caribbean, capable of producing bio-fungicide metabolites against Fusarium solani and Fusarium equiseti. For this, dual-culture assays, liquid-state fermentation of endophytic isolates, and metabolite extractions were conducted. From 88 isolates recovered from leaves and roots, those classified within the Diaporthe genus exhibited the most significant antifungal activity. Their organic extracts displayed median inhibitory concentrations (IC₅₀) approaching 200 μg/mL. To investigate the mechanism of action, in silico studies targeting Chitin Synthase (CS) were performed, including homology models of the pathogens' CS generated using Robetta, followed by molecular docking with Vina, and interaction fingerprint similarity analysis of 15 antifungal metabolites produced by Diaporthe species using PROLIF. A consensus scoring strategy identified diaporxanthone A (12) and diaporxanthone B (13) as the most promising candidates, achieving scores up to 0.73 against F. equiseti, comparable to the control Nikkomycin Z (0.82). These results suggest that Antillean avocado endophytes produce bioactive metabolites that may inhibit fungal cell wall synthesis, offering a sustainable alternative for disease management.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Plant Material

2.2. Avocado Phytopathogens Isolation

2.3. Fungal Endophytes Isolation

2.4. Inhibitory Activity of Fungal Endophytes and Their Organic Extracts

2.5. Morphological and Molecular Characterizations of Endophytes

2.6. Homology Modeling and Structural Selection

2.7. Molecular Docking and Interaction Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

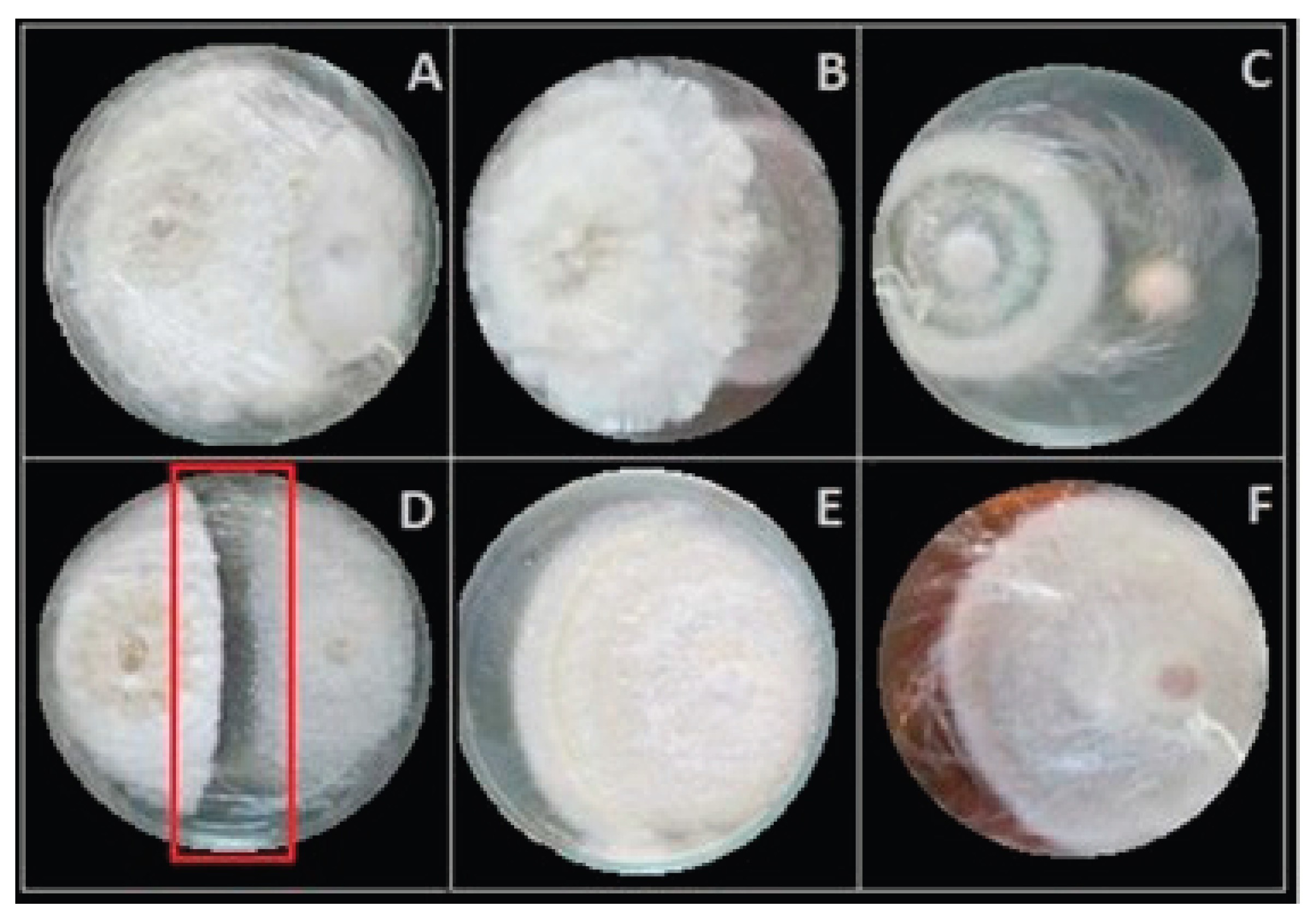

3.1. Avocado Phytopathogens Isolation

3.2. Avocado Fungal Endophytes Isolation

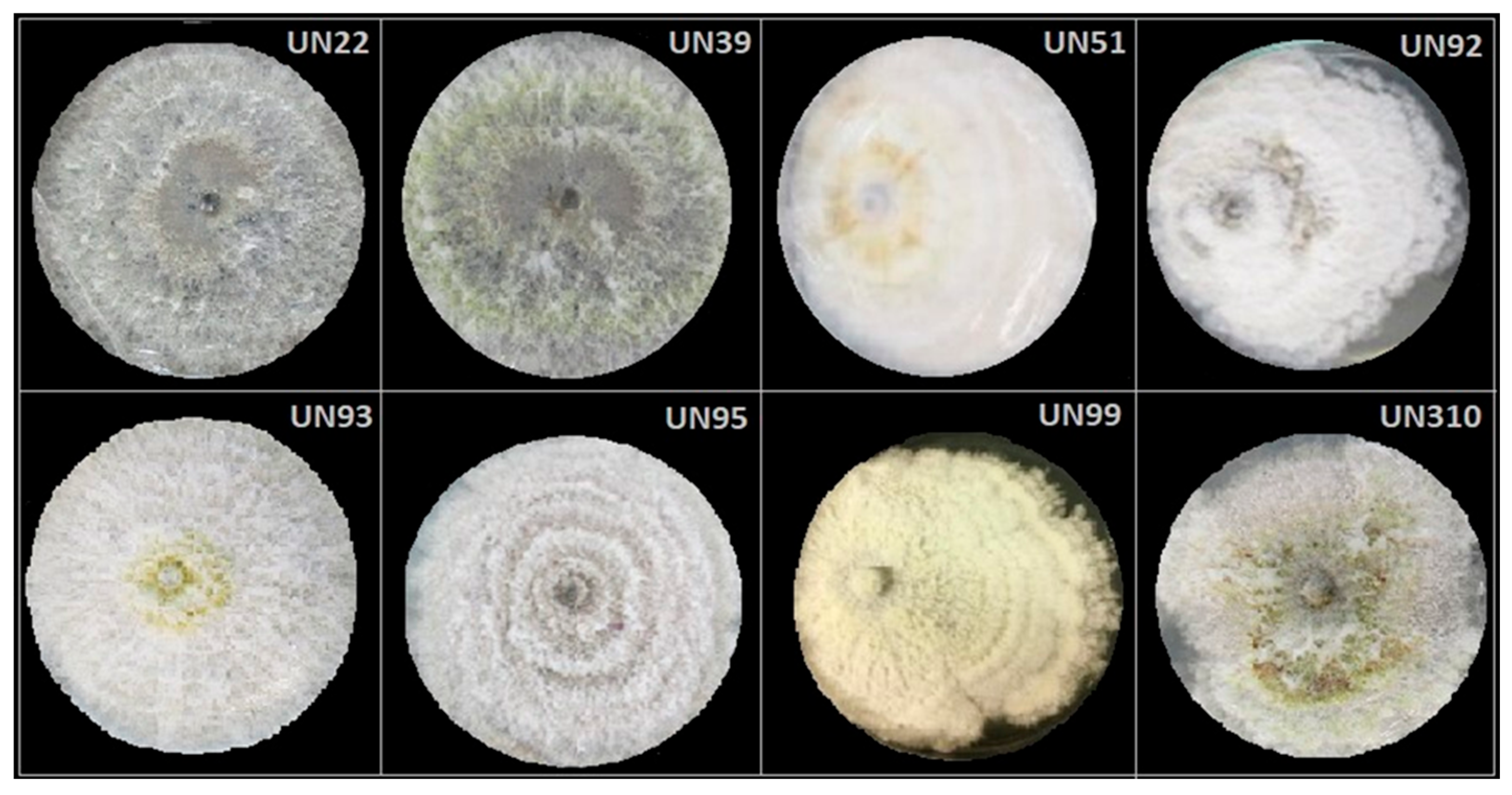

3.3. Morphological and Molecular Characterizations of the Most Promising Endophytes

3.4. Some Antifungal Compounds from Endophytic Diaporthe sp.

3.5. Molecular Docking of Diaporthe Antifungals with Chitin Synthase

3.6. Concluding Remarks

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AWC | Avocado Wilt Complex |

| CS | Chitin Synthase |

| DMSO | Dimethyl Sulfoxide |

| EtOAc | Ethyl Acetate |

| IC₅₀ | Median Inhibitory Concentration |

| MGI | Mycelial Growth Inhibition |

| MIC | Minimal Inhibitory Concentration |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

References

- Hafez, M.; Telfer, M.; Chatterton, S.; Aboukhaddour, R. Specific Detection and Quantification of Major Fusarium spp. Associated with Cereal and Pulse Crops. In Plant-Pathogen Interactions; Springer US: New York: New York, NY, 2023; Volume 2659, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, L. Fusarium Species Associated with Diseases of Major Tropical Fruit Crops. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwomadu, T.I.; Akinola, S.A.; Mwanza, M. Fusarium Mycotoxins, Their Metabolites (Free, Emerging, and Masked), Food Safety Concerns, and Health Impacts. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Cui, L.; Sajid, A.; Zainab, F.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Z. The epigenetic mechanisms in Fusarium mycotoxins induced toxicities. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 123, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D.P.; Bihn, E.A. “Safety and Practice for Organic Food,” in Safety and Practice for Organic Food; Elsevier Inc., 2019; Volume ch. The Impact, pp. 321–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tör, M.; Woods-Tör, A. Genetic Modification of Disease Resistance : Fungal and Oomycete Pathogens. Encyclopedia of Applied Plant Sciences 2017, 3, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koli, P.; Bhardwaj, N.R.; Mahawer, S.K. “Climate Change and Agricultural Ecosystems,” in Climate Change and Agricultural Ecosystems; Elsevier Inc., 2019; Volume ch. Agrochemic, pp. 65–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilário, S.; Gonçalves, M.F.M. Endophytic Diaporthe as Promising Leads for the Development of Biopesticides and Biofertilizers for a Sustainable Agriculture. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kaushik, N.; Sharma, A.; Marzouk, T.; Djébali, N. Exploring the potential of endophytes and their metabolites for bio-control activity. 3 Biotech 2022, 12, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Priyanka; Sharma, S. Metabolomic Insights Into Endophyte-Derived Bioactive Compounds. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 835931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, J.G.; Griffin, E.A. The diversity and distribution of endophytes across biomes, plant phylogeny and host tissues: how far have we come and where do we go from here? Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 2107–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strobel, G.; Daisy, B. Bioprospecting for Microbial Endophytes and Their Natural Products. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2003, 67, 491–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burbano-Figueroa, O. University of Bonn West Indian avocado agroforestry systems in Montes de María (Colombia): a conceptual model of the production system. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 2019, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega, J.Y. El aguacate en Colombia : Estudio de caso de los Montes de María, en el Caribe colombiano. Banco de la República de Colombia. Centro de estudios económicos regionales. 2012, 171, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puello, A. La transformación de la estructura productiva de los Montes de María: de despensa agrícola a distrito minero-energético. In Revista Digital de Historia y Arqueología desde el Caribe; 2016; vol. 29, pp. 52–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, J.G.R. Avocado wilt complex disease, implications and management in Colombia. 2018, 71, 8525–8541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Wei, Y.; Jiang, S.; Xu, F.; Wang, H.; Zhan, P.; Shao, X. ROS Stress and Cell Membrane Disruption are the Main Antifungal Mechanisms of 2-Phenylethanol against Botrytis cinerea. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022, 70, 14468–14479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oiki, S.; Nasuno, R.; Urayama, S.-I.; Takagi, H.; Hagiwara, D. Intracellular production of reactive oxygen species and a DAF-FM-related compound in Aspergillus fumigatus in response to antifungal agent exposure. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasim, S.; Coleman, J.J. Targeting the Fungal Cell Wall: Current Therapies and Implications for Development of Alternative Antifungal Agents. Futur. Med. Chem. 2019, 11, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.L.; Colombo, A.L.; Junior, J.N.d.A. Fungal Cell Wall: Emerging Antifungals and Drug Resistance. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, S.M.; Free, S.J. The structure and synthesis of the fungal cell wall. BioEssays 2006, 28, 799–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Ding, X.; Yang, P.; Huang, K.; Hu, X.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X.; Yu, H. Structures and mechanism of chitin synthase and its inhibition by antifungal drug Nikkomycin Z. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Qiu, S.; Bao, Y.; Chen, H.; Lu, Y.; Chen, X. Screening and Application of Chitin Synthase Inhibitors. Processes 2020, 8, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheeda, K.; Shyam, K. Formulation of Novel Surface Sterilization Method and Culture Media for the Isolation of Endophytic Actinomycetes from Medicinal Plants and its Antibacterial Activity. J Plant Pathol Microbiol 2017, 8(no. 02), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Shen, G.; Teng, H.; Yang, C.; Song, C.; Xiang, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Identification, Pathogenicity, and Genetic Diversity of Fusarium spp. Associated with Maize Sheath Rot in Heilongjiang Province, China. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson, L.E.; Shivas, R.G.; Dann, E.K. Pathogenicity of Nectriaceous Fungi on Avocado in Australia. Phytopathology® 2017, 107, 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamboa, M.A.; Laureano, S.; Bayman, P. Measuring diversity of endophytic fungi in leaf fragments: Does size matter? Mycopathologia 2003, 156, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner-Mendoza, C.; Navarro-Barranco, H.; Ayala-zermeño, M. A.; Mellín-Rosas, M.; Toriello, C. Obtención y caracterización de cultivos monospóricos de Metarhizium anisopliae (Hypocreales: Clavicipitaceae) para genotipificación. Memorias del XXXVI Congreso Nacional de Control Biológico, Oaxaca de Juárez, 2013; pp. 52–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Webster, G.; Xie, L.; Yu, C.; Li, Y.; Liao, X. A new method for the preservation of axenic fungal cultures. J. Microbiol. Methods 2014, 99, 81–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhonen, E.; Sipari, N.; Asiegbu, F.O. Inhibition of phytopathogens by fungal root endophytes of Norway spruce. Biol. Control. 2016, 99, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, J.E.P.; Cuca, L.E.; González-Coloma, A. Antifungal and phytotoxic activity of benzoic acid derivatives from inflorescences of Piper cumanense. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 35, 2763–2771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnold, A.E. Understanding the diversity of foliar endophytic fungi: progress, challenges, and frontiers. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2007, 21, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgulis, A.; Coulouris, G.; Raytselis, Y.; Madden, T.L.; Agarwala, R.; Schäffer, A.A. Database indexing for production MegaBLAST searches. Bioinformatics 2008, 24, 1757–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UniProt Consortium. UniProt: A worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D506–D515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovchinnikov, S.; Park, H.; Kim, D.E.; DiMaio, F.; Baker, D. Protein structure prediction using Rosetta in CASP12. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2017, 86, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Wuyun, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, X.; Peng, C.; Zhu, Y.; Freddolino, L.; Zhang, Y. Deep-learning-based single-domain and multidomain protein structure prediction with D-I-TASSER. Nat. Biotechnol. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurrus, E.; Engel, D.; Star, K.; Monson, K.; Brandi, J.; Felberg, L.E.; Brookes, D.H.; Wilson, L.; Chen, J.; Liles, K.; et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein Sci. 2017, 27, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrum, G. Release 2016_09_4 (Q3 2016) Release · rdkit/rdkit · GitHub. 02 Dec 2025. Available online: https://github.com/rdkit/rdkit/releases/tag/Release_2016_09_4.

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open babel: An open chemical toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Cao, P.; Liu, Y.; Yu, A.; Wang, D.; Chen, L.; Sundarraj, R.; Yuchi, Z.; Gong, Y.; Merzendorfer, H.; et al. Structural basis for directional chitin biosynthesis. Nature 2022, 610, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meli, R.; Biggin, P.C. spyrmsd: symmetry-corrected RMSD calculations in Python. J. Chemin- 2020, 12, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouysset, C.; Fiorucci, S. ProLIF: a library to encode molecular interactions as fingerprints. J. Chemin- 2021, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajmal, M.; Hussain, A.; Ali, A.; Chen, H.; Lin, H. Strategies for Controlling the Sporulation in Fusarium spp. J. Fungi 2022, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olalde-Lira, G. G.; Lara-Chávez, B. N. Characterization of Fusarium spp., a Phytopathogen of avocado (Persea americana Miller var. drymifolia (Schltdl. and Cham.) in Michoacán, México. Rev. FCA UNCUYO 2020, 52(no. 2), 301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Wanjiku, E.K.; Waceke, J.W.; Wanjala, B.W.; Mbaka, J.N. Identification and Pathogenicity of Fungal Pathogens Associated with Stem End Rots of Avocado Fruits in Kenya. Int. J. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 4063697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, M. Guerrero; Portilla, A. Ramos. Prevenga y maneje la pudrición radical del aguacate causada por el Oomycete Phytophthora cinnamomi Rands; Oficina Asesora de Comunicaciones ICA: Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Corchuelo, D. Orjuela; Murillo, M. Avila. Microorganismos endófitos como alternativa para el control de hongos patógenos asociados al cultivo del aguacate en Colombia. Tesis de Maestria en Ciencias-Química, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá D.C., Colombia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Gil, J.G.; Ramelli, E.G.; Osorio, J.G.M. Economic impact of the avocado (cv. Hass) wilt disease complex in Antioquia, Colombia, crops under different technological management levels. Crop. Prot. 2017, 101, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios Joya, L. Caracterización de microorganismos asociados a la pudrición de raíces de aguacate Persea americana Mill en viveros del Valle del Cauca, Colombia; Palmira, Colombia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Novoa-Yánez, R. S. Manual de producción de semilla de aguacate criollo en vivero en los Montes de María, Primera Edición; AGROSAVIA: Mosquera, Cundinamarca, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shahzad, R.; Khan, A.L.; Bilal, S.; Asaf, S.; Lee, I.-J. What Is There in Seeds? Vertically Transmitted Endophytic Resources for Sustainable Improvement in Plant Growth. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Agri, U.; Chaudhary, A.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, G. Endophytes and their potential in biotic stress management and crop production. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 933017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.K.; Kingsley, K.L.; Bergen, M.S.; Kowalski, K.P.; White, J.F. Fungal Disease Prevention in Seedlings of Rice (Oryza sativa) and Other Grasses by Growth-Promoting Seed-Associated Endophytic Bacteria from Invasive Phragmites australis. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, G. Analysis of Secondary Metabolites from Plant Endophytic Fungi. Plant Pathogenic Fungi and Oomycetes: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology 2018, 1848, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, J.; Sharma, V.K.; Singh, D.K.; Kumari, P.; Nishad, J.H.; Gautam, V.S.; Kharwar, R.N. Phytochemical analysis and antimicrobial activity of an endophytic Fusarium proliferatum (ACQR8), isolated from a folk medicinal plant Cissus quadrangularis L. South Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 140, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Liu, Z.-Q.; Chen, Q.; Xu, Y.-W.; Hou, K.; Wu, W. Endophytic fungus strain 28 isolated from Houttuynia cordata possesses wide-spectrum antifungal activity. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2016, 47, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, V.C.; Gange, A.C. Advances in Endophytic Research. Adv. Endophytic Res. 2014, 1–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.-C.; Lu, Y.-H.; Wang, J.-F.; Song, Z.-Q.; Hou, Y.-G.; Liu, S.-S.; Liu, C.-S.; Wu, S.-H. Bioactive Secondary Metabolites of the Genus Diaporthe and Anamorph Phomopsis from Terrestrial and Marine Habitats and Endophytes: 2010–2019. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretz, R.; Wendt, L.; Wongkanoun, S.; Luangsa-Ard, J.J.; Surup, F.; Helaly, S.E.; Noumeur, S.R.; Stadler, M.; Stradal, T.E. The Effect of Cytochalasans on the Actin Cytoskeleton of Eukaryotic Cells and Preliminary Structure–Activity Relationships. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Ruan, Q.; Jiang, S.; Qu, Y.; Chen, J.; Zhao, M.; Yang, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Cui, H. Cytochalasins and polyketides from the fungus Diaporthe sp. GZU-1021 and their anti-inflammatory activity. Fitoterapia 2019, 137, 104187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, M.; Patil, R.; Mohammad, S.; Maheshwari, V. Bioactivities of phenolics-rich fraction from Diaporthe arengae TATW2, an endophytic fungus from Terminalia arjuna (Roxb.). Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2017, 10, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Yu, J.; Chen, S.; Ding, M.; Huang, X.; Yuan, J.; She, Z. Alkaloids from the mangrove endophytic fungus Diaporthe phaseolorum SKS019. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 803–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, A.R.C.; Baldoni, D.B.; Lima, J.; Porto, V.; Marcuz, C.; Ferraz, R.C.; Kuhn, R.C.; Jacques, R.J.; Guedes, J.V.; Mazutti, M.A. Bioherbicide production by Diaporthe sp. isolated from the Brazilian Pampa biome. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2015, 4, 575–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Reis, C.M.; da Rosa, B.V.; da Rosa, G.P.; Carmo, G.D.; Morandini, L.M.B.; Ugalde, G.A.; Kuhn, K.R.; Morel, A.F.; Jahn, S.L.; Kuhn, R.C. Antifungal and antibacterial activity of extracts produced from Diaporthe schini. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 294, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, C.; Tong, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Ye, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhang, Y. Progress in the Chemistry of Cytochalasans. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod 2021, 114, 1–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhou, D.; Liang, Y.; Liu, X.; Cao, F.; Qin, Y.; Mo, T.; Xu, Z.; Li, J.; Yang, R. Cytochalasins from endophytic Diaporthe sp. GDG-118. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019, 35, 3396–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Yang, Z.; Feng, L.H.; Hao, Y.Y.; Hua, G.J. Antifungal metabolites from Phomopsis sp. By254, an endophytic fungus in Gossypium hirsutum. Afr. J. Microbiol. Res. 2011, 5, 1231–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, C.R.; Ferreira-D'Silva, A.; Wedge, D.E.; Cantrell, C.L.; Rosa, L.H. Antifungal activities of cytochalasins produced by Diaporthe miriciae, an endophytic fungus associated with tropical medicinal plants. Can. J. Microbiol. 2018, 64, 835–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanney, J.B.; McMullin, D.R.; Green, B.D.; Miller, J.D.; Seifert, K.A. Production of antifungal and antiinsectan metabolites by the Picea endophyte Diaporthe maritima sp. nov. Fungal Biol. 2016, 120, 1448–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Yang, Z.; Zhao, F.; Tian, Y. Antimicrobial Potential of Endophytic Fungi From Artemisia argyi and Bioactive Metabolites From Diaporthe sp. AC1. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 908836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonial, F.; Maia, B.H.L.N.S.; Sobottka, A.M.; Savi, D.C.; Vicente, V.A.; Gomes, R.R.; Glienke, C. Biological activity of Diaporthe terebinthifolii extracts against Phyllosticta citricarpa. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Sun, F.; Li, G.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, C.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; et al. New Xanthones with Antiagricultural Fungal Pathogen Activities from the Endophytic Fungus Diaporthe goulteri L17. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 11216–11224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.-Q.; Du, S.-T.; Xiao, J.; Wang, D.-C.; Han, W.-B.; Zhang, Q.; Gao, J.-M. Isolation and Characterization of Antifungal Metabolites from the Melia azedarach-Associated Fungus Diaporthe eucalyptorum. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 2418–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savi, D.C.; Noriler, S.A.; Ponomareva, L.V.; Thorson, J.S.; Rohr, J.; Glienke, C.; Shaaban, K.A. Dihydroisocoumarins produced by Diaporthe cf. heveae LGMF1631 inhibiting citrus pathogens. Folia Microbiol. 2019, 65, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, A.; Hochkoeppler, A. The catalytic action of enzymes exposed to charged substrates outperforms the activity exerted on their neutral counterparts. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 751, 151436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkakoti, N.; Ribeiro, A.J.; Thornton, J.M. A structural perspective on enzymes and their catalytic mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2025, 92, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfmueller, H.C.; Ferenbach, A.T.; Borodkin, V.S.; van Aalten, D.M.F. A Structural and Biochemical Model of Processive Chitin Synthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 23020–23028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, M.Á.; Butassi, E.; Ribas, J.C.; Svetaz, L.A.; Cortés, J.C. Natural products targeting the synthesis of β(1,3)-D-glucan and chitin of the fungal cell wall. Existing drugs and recent findings. Phytomedicine 2021, 88, 153556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belmonte, L.; Mansy, S.S. Patterns of Ligands Coordinated to Metallocofactors Extracted from the Protein Data Bank. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2017, 57, 3162–3171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Fungal isolate | Accession number | Closest related species | Similarity (%) |

| UN02 | PP052962 | OQ673588.1 Epicoccum sp. | 100.00 |

| UN23 | PP052963 | MG980304.1 Colletotrichum sp. | 100.00 |

| UN29 | OQ271226.1 | MN989030.1 Fusarium solani | 100.00 |

| UN31 | PP052964 | NR_130690.1 Fusarium sp. | 100.00 |

| UN36 | PP052965 | LC406903.1 Colletotrichum sp. | 99.65 |

| UN37 | OQ344629.1 | OP006756.1 Fusarium equiseti | 100.00 |

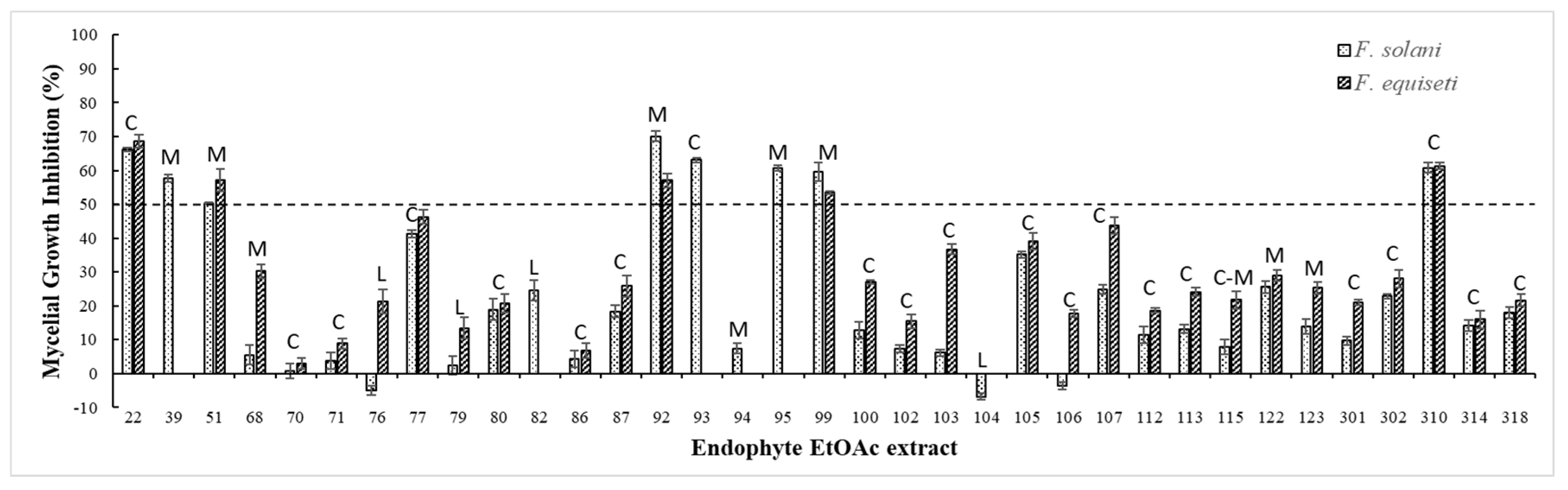

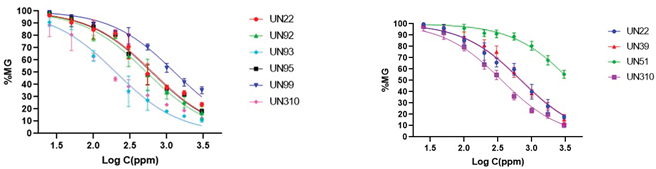

| Endophytic EtOAc extract N. |

% MGI | Endophytic EtOAc extract N. |

% MGI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F. solani | F. equiseti | F. solani | F. equiseti | ||

| UN22 | 66,2 ± 0,5h,A | 68,6 ± 2,0a,A | UN100 | 12,8 ± 2,5e | 27,1 ± 0,6h |

| UN39 | 57,7 ± 1,2i | 70,9 ± 3,2a | UN102 | 7,3 ± 1,1a,d | 15,5 ± 2,1j |

| UN51 | 50,2 ± 0,3 | 57,1 ± 3,3b | UN103 | 6,2 ± 0,9a,d | 36,7 ± 1,6f |

| UN68 | 5,6 ± 2,9a | 30,3 ± 2,1g | UN104 | -6,8 ± 1,0c | N/E |

| UN70 | 0,9 ± 2,2b,B | 3,0 ± 1,7B | UN105 | 35,1 ± 1,0 | 39,1 ± 2,5d,e |

| UN71 | 3,8 ± 2,5a,b | 8,9 ± 1,5k | UN106 | -3,6 ± 1,0c | 17,7 ± 1,1i,j |

| UN76 | -5,1 ± 1,4c | 21,3 ± 3,4i | UN107 | 24,9 ± 1,3g | 43,8 ± 2,5e |

| UN77 | 41,2 ± 1,2k | 46,2 ± 2,0d | UN112 | 11,5 ± 2,3e | 18,7 ± 0,7i,j |

| UN79 | 2,4 ± 2,7a,b | 13,5 ± 3,1j | UN113 | 13,2 ± 1,2e | 24,1 ± 1,2h |

| UN80 | 18,9 ± 3,2f,C | 20,8 ± 2,7i,C | UN115 | 8,0 ± 2,2a,d,e | 21,7 ± 2,6i |

| UN82 | 24,5 ± 3,1g | N/E | UN122 | 25,6 ± 1,8g | 29,0 ± 1,6g,h |

| UN86 | 4,3 ± 2,4a,D | 6,7 ± 2,2k,D | UN123 | 14,0 ± 2,2e | 25,3 ± 1,7h |

| UN87 | 18,3 ± 1,8f | 25,9 ± 3,1h | UN301 | 9,7 ± 1,3d,e | 21,0 ± 0,8i |

| UN92 | 70,1 ± 1,6j | 57,1 ± 2,0b | UN302 | 22,8 ± 0,7g | 28,0 ± 2,7g |

| UN93 | 63,1 ± 0,7h | 19,9 ± 1,67 | UN310 | 60,8 ± 1,6h,i,E | 61,3 ± 1,0b,c,E |

| UN94 | 7,4 ± 1,5a,d | N/E | UN314 | 14,3 ± 1,6e,f,F | 16,0 ± 2,6j,F |

| UN95 | 60,7 ± 0,9h,i | 51,1 ± 3,7e | UN318 | 18,0 ± 1,6f | 21,6 ± 1,8i |

| UN99 | 59,6 ± 2,9h,i | 53,4 ± 0,5e | --- | --- | --- |

|

|||||||

|

Endophytic EtOAc N. |

F. solani | F. equiseti | |||||

| IC50 (µg/mL) | IC50 (µg/mL) | ||||||

| UN22 | 650 ± 69b,B | 688 ± 50a,B | |||||

| UN39 | N/D | 710 ± 43a | |||||

| UN51 | N/D | ˃3000 | |||||

| UN92 | 531 ± 51b | N/D | |||||

| UN93 | 199 ± 29c | N/D | |||||

| UN95 | 550 ± 40b | N/D | |||||

| UN99 | 1281 ± 78a | N/D | |||||

| UN310 | 204 ± 25c,D | 362 ± 27b,D | |||||

| Fungal isolate | Accession number | Closest related species | Similarity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UN22 | OQ914368 | MW566594.1 Diaporthe ueckeri | 99 |

| UN39 | OQ914369 | MW380843.1 Diaporthe phaseolorum | 100 |

| UN51 | OQ914370 | EF694672.1 Nodulisporium sp. | 96 |

| UN92 | OQ914371 | MW380843.1 Diaporthe phaseolorum | 100 |

| UN93 | OQ914372 | KF498865.1 Diaporthe phaseolorum | 100 |

| UN95 | OQ914373 | KX631735.1 Diaporthe longicolla | 100 |

| UN99 | OQ914374 | AY577815.1 Diaporthe phaseolorum | 100 |

| UN310 | OQ914375 | KF498865.1 Diaporthe phaseolorum | 99 |

| F. solani | F. equiseti | |||||

| id | Vina score | PROLIF similarity | Consensus score | Vina score | PROLIF similarity | Consensus score |

| Nikkomycin Z | 0,57 | 1,00 | 0,78 | 0,65 | 1,00 | 0,82 |

| Cytochalasin E (1) | 0,27 | 0,63 | 0,45 | 0,37 | 0,48 | 0,42 |

| Cytochalasin H (2) | 0,16 | 0,49 | 0,32 | 0,30 | 0,38 | 0,34 |

| 7-acetoxy-cytochalasin (3) | 0,22 | 0,75 | 0,49 | 0,26 | 0,85 | 0,56 |

| Cytochalasin N (4) | 0,24 | 0,44 | 0,34 | 0,38 | 0,75 | 0,57 |

| Epoxy-cytochalasin H (5) | 0,26 | 0,67 | 0,46 | 0,29 | 0,57 | 0,43 |

| Cytochalasin J (6) | 0,23 | 0,69 | 0,46 | 0,38 | 0,59 | 0,48 |

| Phomompsolide A (7) | 0,31 | 0,42 | 0,37 | 0,37 | 0,55 | 0,46 |

| Phomompsolide B (8) | 0,40 | 0,56 | 0,48 | 0,24 | 0,55 | 0,39 |

| Phomompsolide C (9) | 0,34 | 0,51 | 0,43 | 0,25 | 0,49 | 0,37 |

| Phomompsolide G (10) | 0,16 | 0,19 | 0,17 | 0,33 | 0,45 | 0,39 |

| Verbanol (11) | 0,00 | 0,28 | 0,14 | 0,00 | 0,51 | 0,26 |

| Diaporxanthone A (12) | 1,00 | 0,22 | 0,61 | 0,96 | 0,50 | 0,73 |

| Diaporxanthone B (13) | 0,71 | 0,29 | 0,50 | 1,00 | 0,45 | 0,72 |

| Eucalyptacid A (14) | 0,04 | 0,00 | 0,02 | 0,41 | 0,00 | 0,20 |

| Dihydroisocoumarin (−)-(3R,4R)-cis-4-hydroxy-5-methylmellein (15) | 0,18 | 0,14 | 0,16 | 0,18 | 0,46 | 0,32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).