1. Introduction

Silica-based materials have attracted considerable attention due to their tunable porosity, high specific surface area and versatile applications in thermal insulation, optics, and biomedicine [

1,

2,

3]. The incorporation of biopolymers such as chitosan into silica matrices has been proposed to enhance mechanical strength, biocompatibility, and optical functionality [

4]. Despite numerous studies on silica–chitosan composites, the combined effect of chitosan incorporation on textural, optical, and thermal conductivity properties remains insufficiently explored, and hypotheses regarding its influence on pore structure, heat transfer, and potential luminescent behavior have been suggested [

5,

6]. Some physicochemical questions, concerning the preparation and properties of low chitosan doped silica gels, however, remain unexplained. The preparation of sol–gel silica strongly depends on several parameters, such as the pH of the hydrolysis, the temperature and conditions of gelation, the volume of the system, and the type and amount of the dopant added. In the preparation of hybrid composites, an additional challenge is associated with the changes occurring in the organic molecule (dopant) during the sol–gel process. An example of this is silicа doped with coumarin, benzoic acid, or phenanthroline [

7,

8]. In the sol-gel preparation of such hybrid composites, it is necessary to identify a preparative “window” in which the viscosity of the system allows homogeneous distribution of the dopant at the molecular level, while preserving its chemical and physical properties. Similar issues are relevant for the silica–chitosan system, in which a correlation and a synergistic effect between the matrix and the doping organic compound are expected [

3]. Taking into account the unique properties of chitosan as a dopant, tuning the sol–gel parameters enables the synthesis of composites and compact gels with potential applications in catalysis, optical materials, water adsorption, biomedicine, sensors, and thermal or mechanical protection [

9,

10,

11].

In this work, low doped silica–chitosan composites were synthesized via a novel and simple sol–gel method by varying the chitosan content from 0.2 to 3.3 % in the initial sol to investigate the relationships between microstructure, optical and thermal properties, and doping level. A sol–gel procedure was developed to ensure a homogeneous distribution of the chitosan additive. The synthesis conditions were carefully adjusted to produce reproducible, transparent, homogeneous sols and gel materials with long-term stability.

2. Results and Discussion

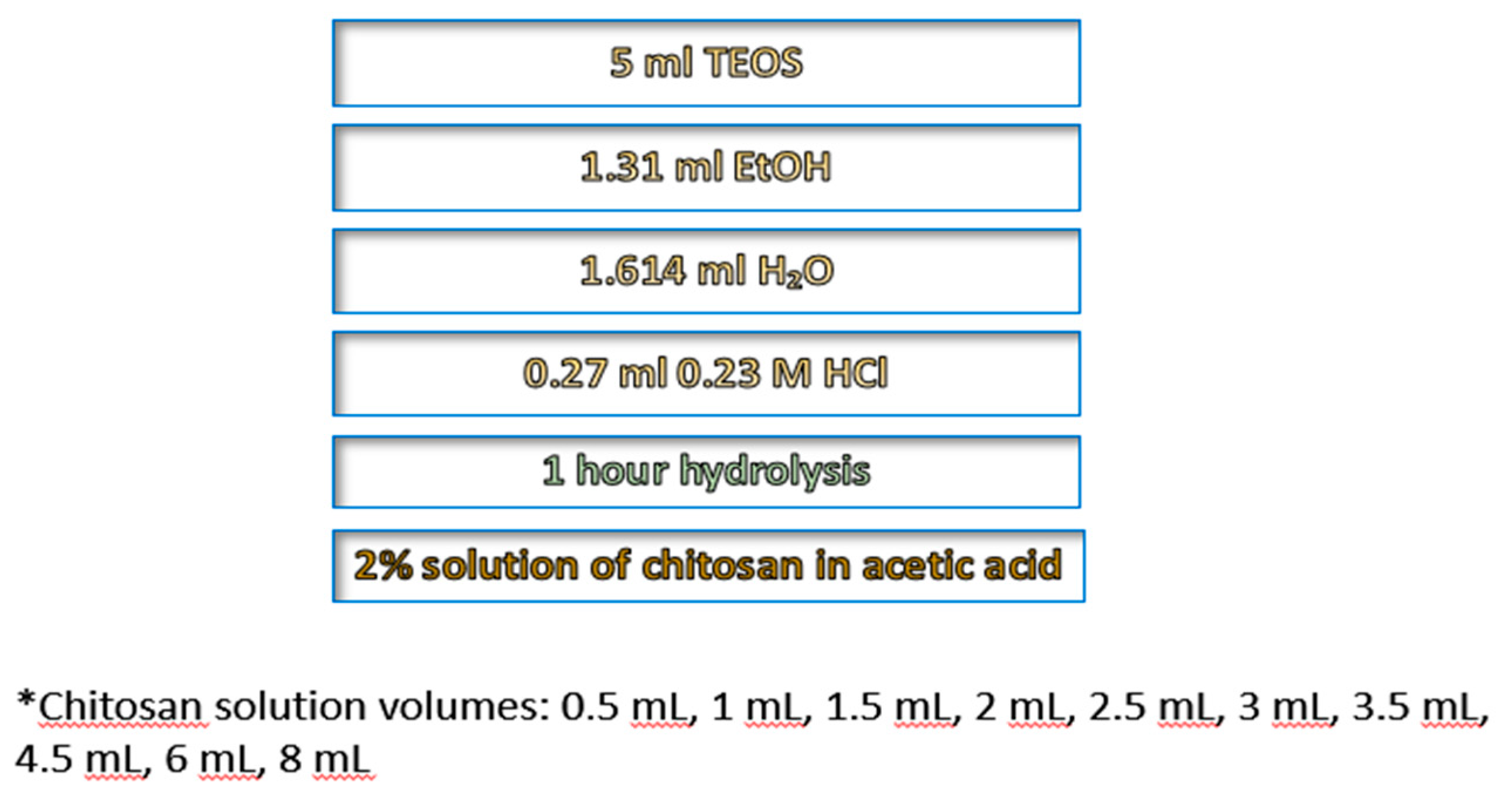

2.1. Preparation Strategy of Silica Doped with Chitosan Gels

The samples were dried at ambient pressure, yielding compact and homogeneous cylindrical xerogels. Samples containing 0.5 and 1 mL of chitosan required mild heating in a water bath at 50 °C to induce gelation, whereas all other samples formed homogeneous sols that gelled spontaneously at room temperature. In other words, at low chitosan concentrations, gelation required mild heating, while at higher concentrations, the sols underwent spontaneous gelation at room temperature. This behavior indicates that chitosan acts as a structure-directing and gel-promoting component, influencing both the kinetics of network formation and the final textural properties of the composites. The resulting xerogels exhibited uniform, monolithic structures without visible cracking, suggesting good compatibility between the silica and biopolymer phases. The preparation scheme is shown in

Figure 1.

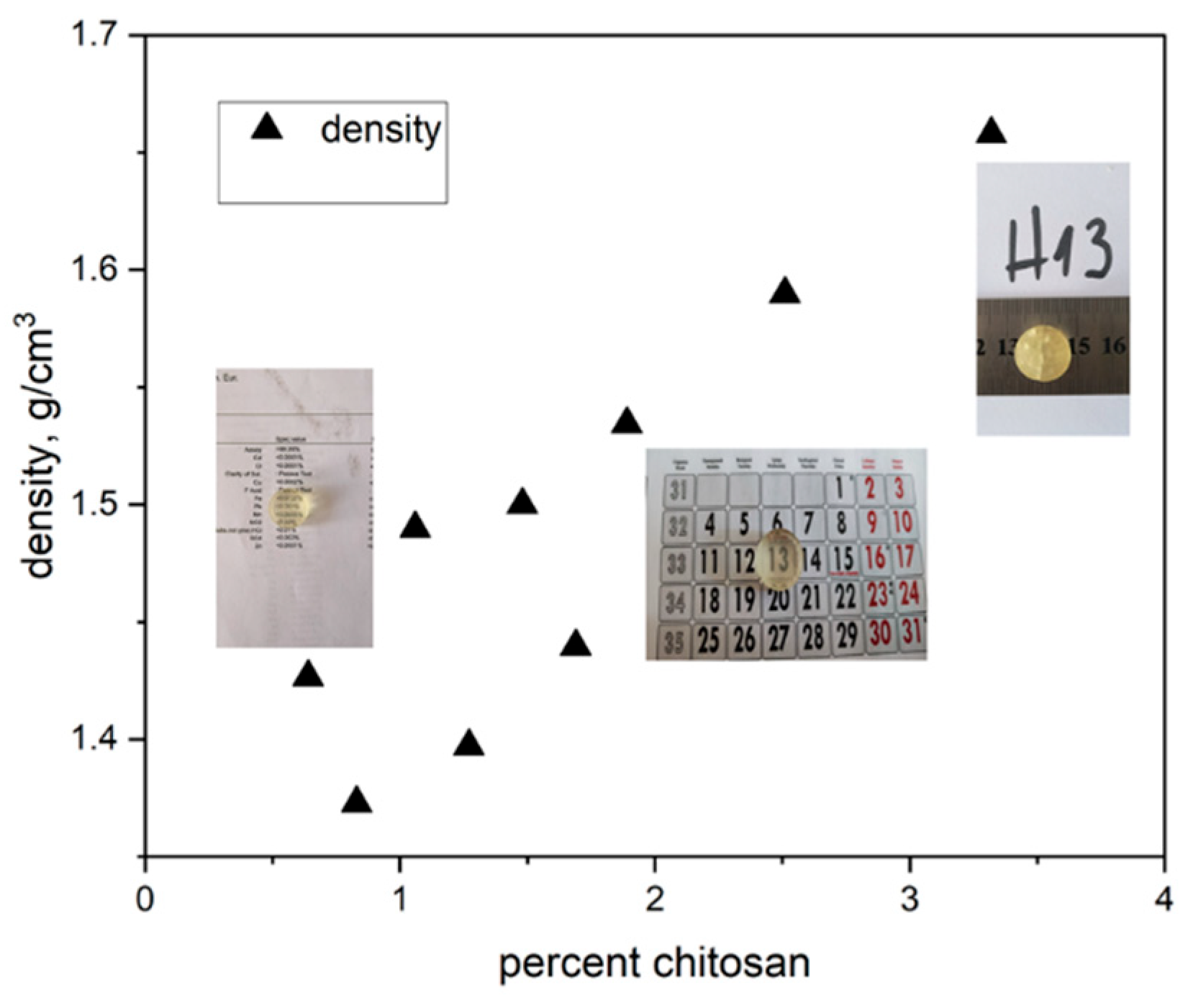

The prepared gels exhibit high density and well-defined cylindrical shapes with uniform size distribution: diameter 1.65–1.80 cm and height 0.5–0.6 cm. The gel densities range from 1.40 to 1.66 g·cm⁻³, increasing with the amount of chitosan added (

Figure 2). Low-doped samples are transparent, whereas gels with higher chitosan content become increasingly opaque, while all retain high density and well-defined shapes.

The chitosan-doped silica composites (0.2–3.3 % chitosan) prepared via the sol–gel method in this study exhibit a high degree of homogeneity and reproducible structural integrity, demonstrating the robustness of the materials. The resulting materials combine a unique set of properties: the mechanical stability of SiO₂ is complemented by the biocompatibility and functional groups of chitosan. This synergy broadens the potential application range of the composites, including pollutant adsorption, controlled drug delivery, catalytic supports, antibacterial coatings, and chemical or biosensing platforms.

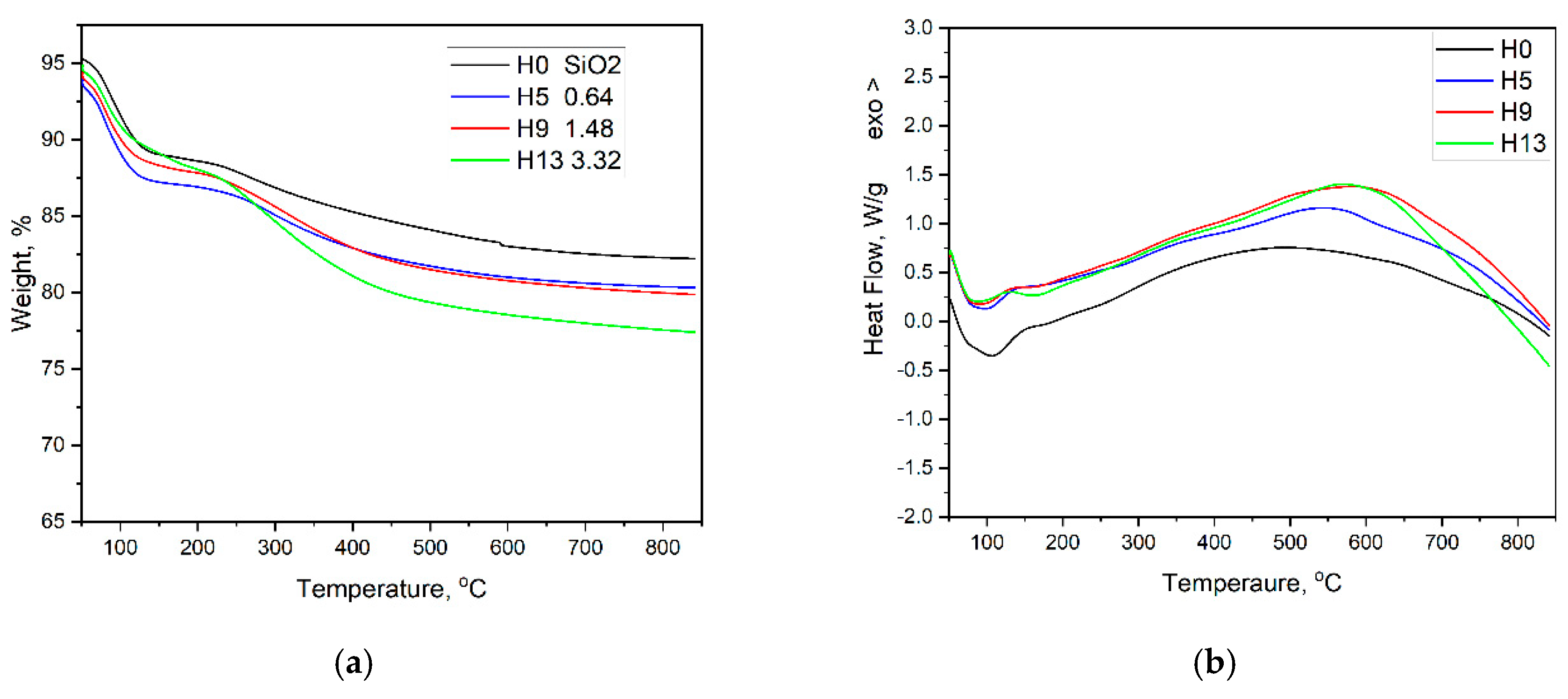

2.2. Thermal Analysis

The thermal behavior of a series of chitosan-doped silica composites with different chitosan contents are also investigated. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) shows that chitosan decomposition occurs between 200 °C and 300 °C, which is confirmed by differential thermal analysis (DTA). In the pure SiO₂ gel, an endothermic peak appears at 100–150 °C, corresponding to the loss of physically adsorbed water (about 15% mass release), followed by a small endothermic peak at 200–300 °C, associated with the decomposition of chitosan in doped samples. Between 500 °C and 700 °C, the already degraded chitosan undergoes further decomposition and carbonization, (

Figure 3). The broad DTA peak observed in this temperature range is most likely due to the gradual nature of this process, including partial oxidation of the residual organic material and the formation of carbonaceous char [

12,

13].

The thermal analysis results presented in this paper are consistent with our previous data concerning sol–gel silica-based nanocomposites [

1,

21]. While the mass loss at low temperatures is associated with dehydration processes of the matrix, it is clearly evident that the thermal effects observed at elevated temperatures are related to structural transformations and decomposition of the dopant—chitosan—and depend on the doping level. The conducted studies indicate that the obtained composites are suitable for applications at low temperatures, T < 50 °C. This low thermal stability could be improved in future work through the use of hydrophobizing additives, as in the case of optical composites based on hydrophobic aerogels. Such a preparative strategy, however, would lead to interactions between the dopant and the hydrophobizing agent.

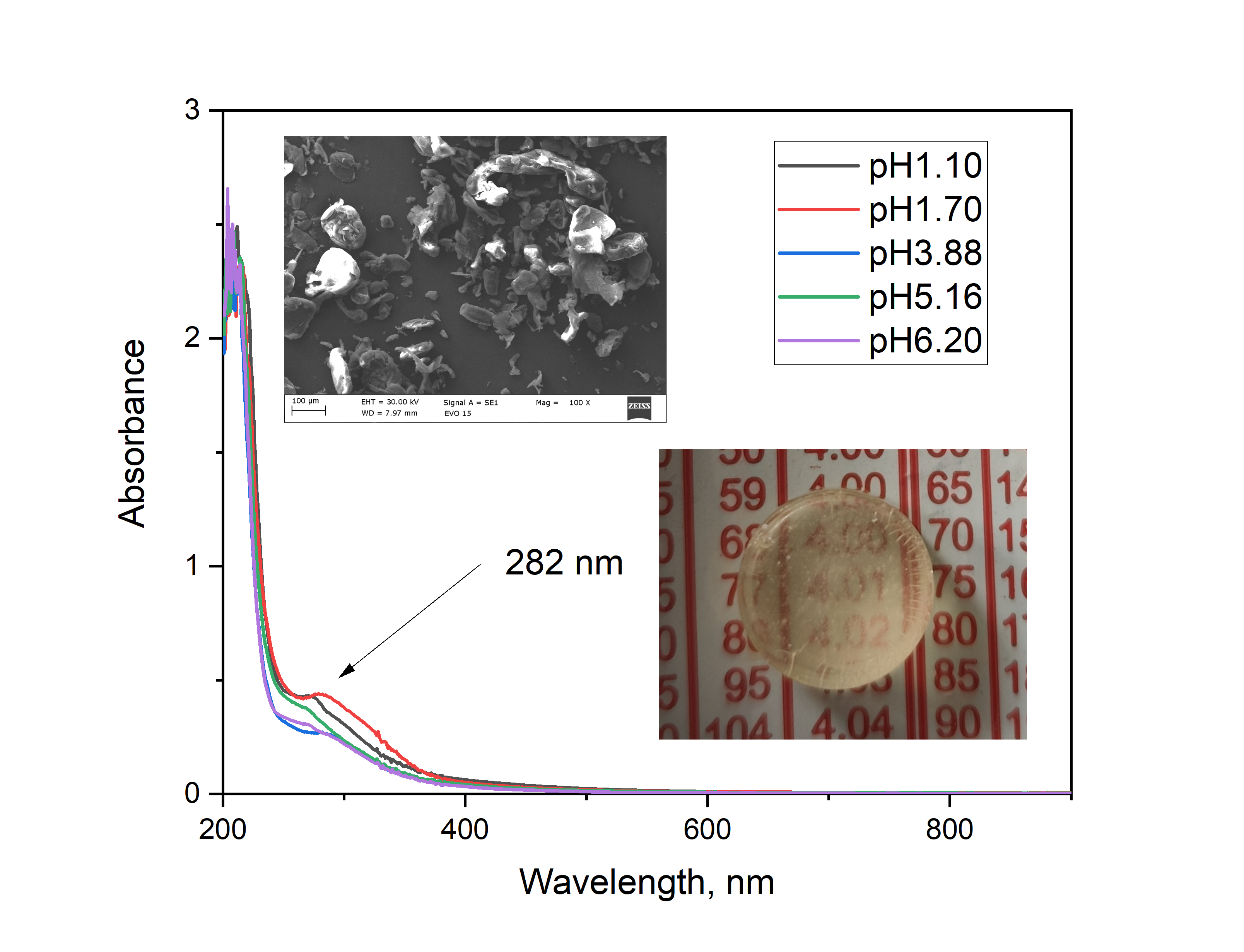

2.3. Optical Properties of Chitosan Solutions and Chitosan-Doped Materials

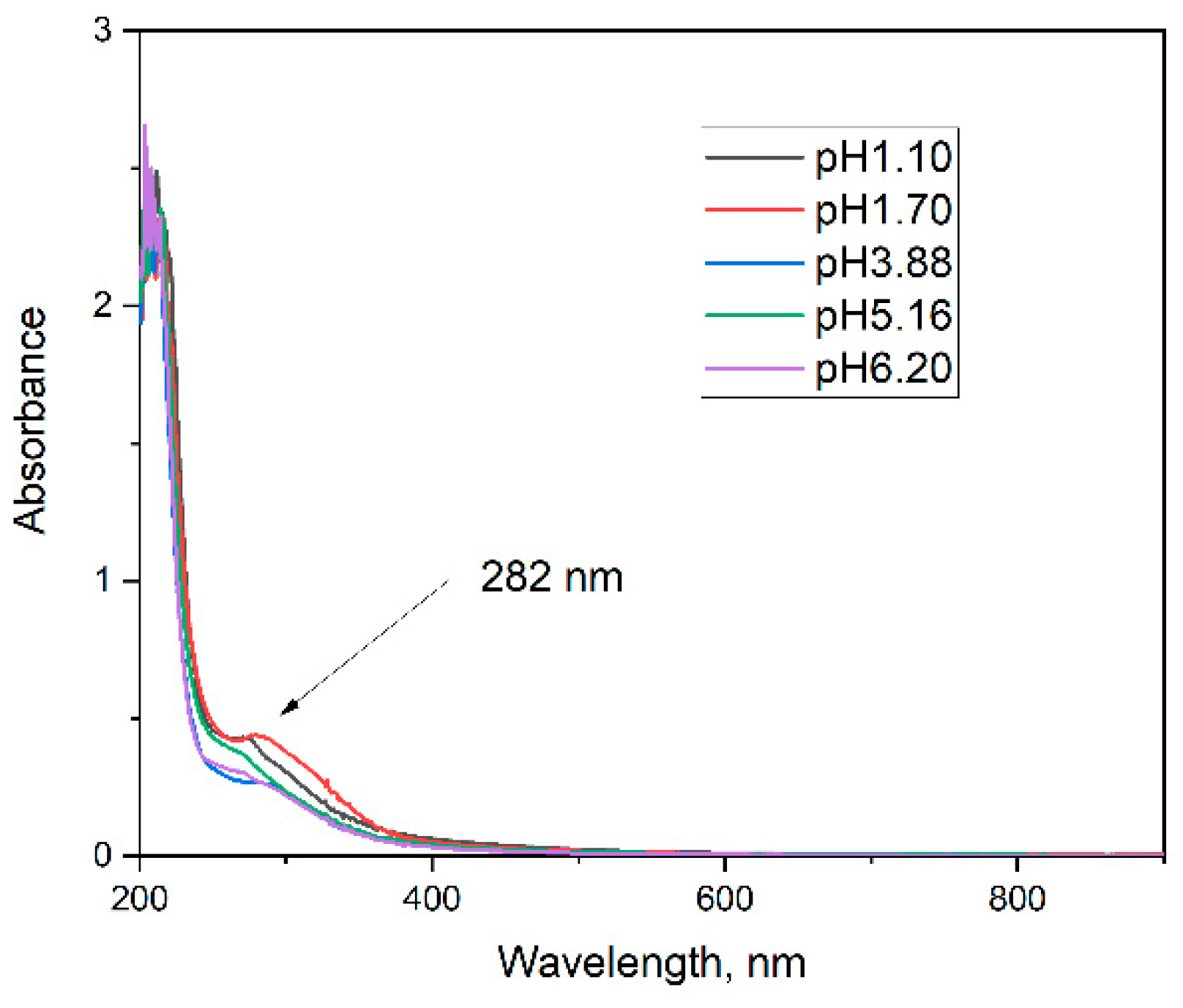

Chitosan solutions exhibit characteristic optical properties related to their polysaccharide nature, as well as to the degree of deacetylation, molecular weight, and pH of the medium. In aqueous or mildly acidic solutions, chitosan is optically transparent in the visible light range (400–800 nm), showing absorption in the UV region below 300 nm, which is primarily attributed to the n→π* transitions of the amine groups. Increasing the polymer concentration enhances light scattering, particularly in the presence of aggregation or pH-induced partial precipitation (

Figure 4). Such changes in optical behavior can provide useful insights into polymer–solvent interactions, conformational changes, and the stability of chitosan solutions. According to Ghazy, [

14] the optical properties of chitosan films extracted from shrimp depend on the degree of deacetylation and the molecular structure of the biopolymer.

The optical properties of chitosan solutions here strongly depend on the pH of the medium (

Figure 4) and correlates well with data about the pK

b of the amino group of the chitosan. Above pH 6.5 the chitosan molecules become deprotonated and non-charged and the solutions turns cloudy because chitosan precipitates. Below pH 6.5 the amino groups are mostly protonated and the molecule is soluble. Two characteristic absorption bands are typically observed — a main peak around 280 nm and a shoulder near 300 nm — with the relative intensity of the 300 nm peak increasing as the pH decreases in agreement with theoretical explanations and measurements in [

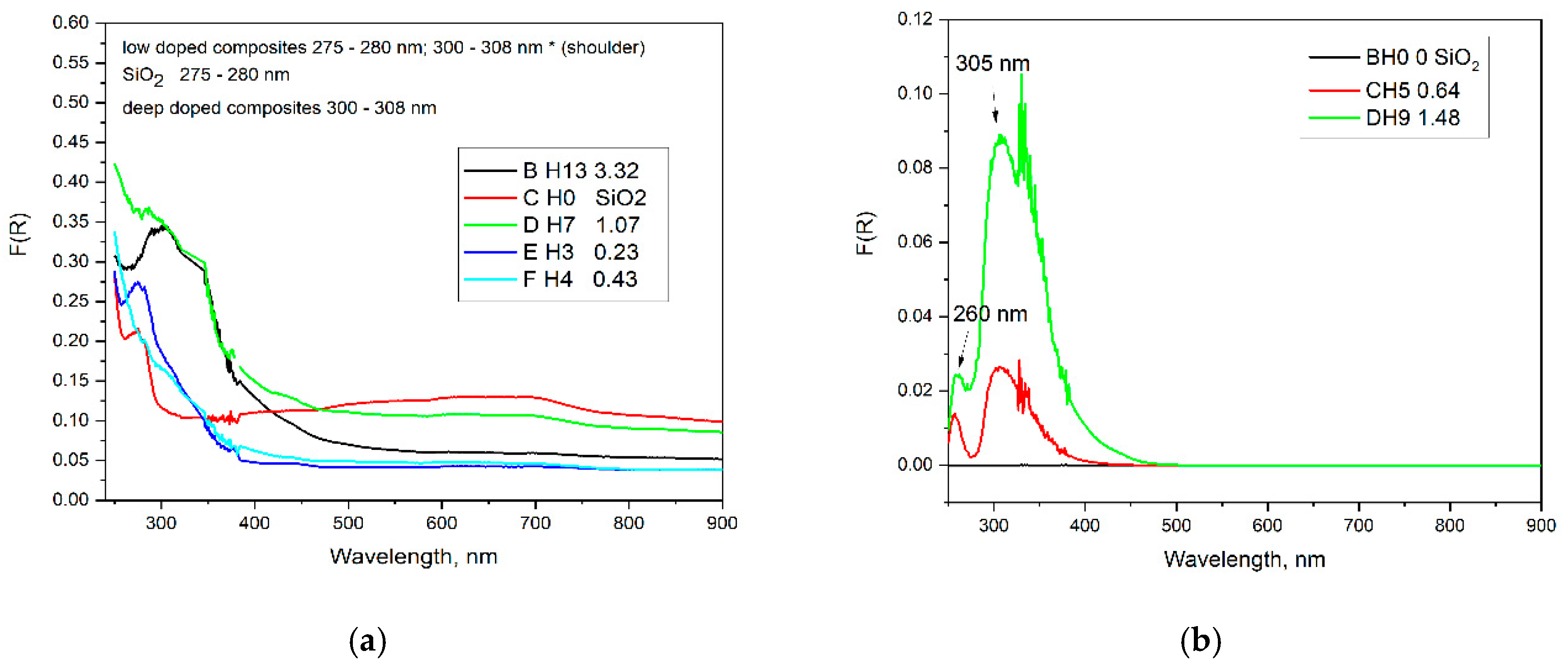

14]. This behavior was confirmed by diffuse reflectance spectra and differential spectra, where the same absorption features are visible but with varying relative intensities. In the spectra of highly doped silica gels, the relative intensity of the 300 nm peak further increases with the doping level, as clearly seen in the differential spectra (

Figure 5b).

From a general spectroscopic perspective, the electronic transitions in chitosan can be classified as follows: transitions observed at 214–228 nm are assigned to π–π* or n–π* transitions associated with amine linkages and/or residual acetylated groups [

14]. Several studies report peaks or shoulders in the 250–283 nm region, sometimes depending on the molecular weight of the polymer or the formation of nanoparticles [

15]. Optical transitions in the 305–310 nm region are possibly related to π–π* transitions of conjugated groups or chitosan acetate particles [

16,

17,

18]. Additionally, chemical bonding between the amino groups of chitosan and the silanol groups of silica leads to changes in local electron density, which may induce slight shifts in the UV–Vis spectra within the 250–300 nm region (

Figure 5).

Owing to its absorption behavior in the near-UV region and high transparency in the visible range, chitosan shows potential as a natural, biocompatible optical UV filter. When incorporated into a silica sol–gel matrix, small but significant changes in the optical properties are observed, arising from interactions between the organic biopolymer and the inorganic network. The resulting silica–chitosan composites generally maintain good optical transparency, particularly at low chitosan content and when the polymer is homogeneously distributed within the matrix. Following the preparation scheme used here (

Figure 1), the most probable reasons for the observed changes in the optical spectra are protonation of chitosan due to the low pH of the solution and the formation of chitosan acetate.

The optical transparency of the composite gels is commonly evaluated through the transmittance coefficient and the refractive index, which depend on the SiO₂/chitosan ratio, the drying method, and the degree of condensation of the silica network. At low chitosan content (up to ~1 %), the materials maintain high transparency, whereas higher contents lead to increased light scattering due to the formation of microphases or polymer agglomerates. Furthermore, incorporation of chitosan into the inorganic network may influence the fluorescence characteristics of the system. As demonstrated in a recent study, chemical modification of chitosan with heterocyclic aromatic dyes resulted in composites with pronounced fluorescence even at low substitution levels, indicating that functionalization of chitosan can effectively impart strong fluorescent properties [

19]. Although chitosan itself exhibits only weak intrinsic fluorescence, the presence of functional groups with donor–acceptor character can facilitate local energy transfer within the composite network, potentially influencing the optical behavior of incorporated species. Thus, silica–chitosan gels provide a suitable platform for the incorporation of optically active species or nanoparticles, which can be stabilized within the matrix without significant loss of transparency and potentially enhance its luminescent properties [

18]. The composite samples obtained in this work, however, do not exhibit visible luminescence under UV excitation.

The diffuse reflectance spectra of the silica–chitosan composites, along with their differential spectra relative to pure silica, reveal characteristic features associated with the chitosan component. The spectral maxima are similar to those observed in chitosan solutions at different pH values but display distinct variations in relative intensity. These differences indicate structural modifications of the chitosan chains upon incorporation and immobilization within the silicate matrix, suggesting changes in the local electronic environment and interaction between the organic and inorganic phases. Overall, the optical behavior of chitosan and silica–chitosan composites reflects a delicate balance between molecular structure, pH-dependent structural conformation, and polymer–matrix interactions. Their high transparency and UV absorption capability render these hybrid systems promising candidates for optical UV filters, photonic coatings, and sensing applications, particularly for environmentally friendly and biocompatible materials.

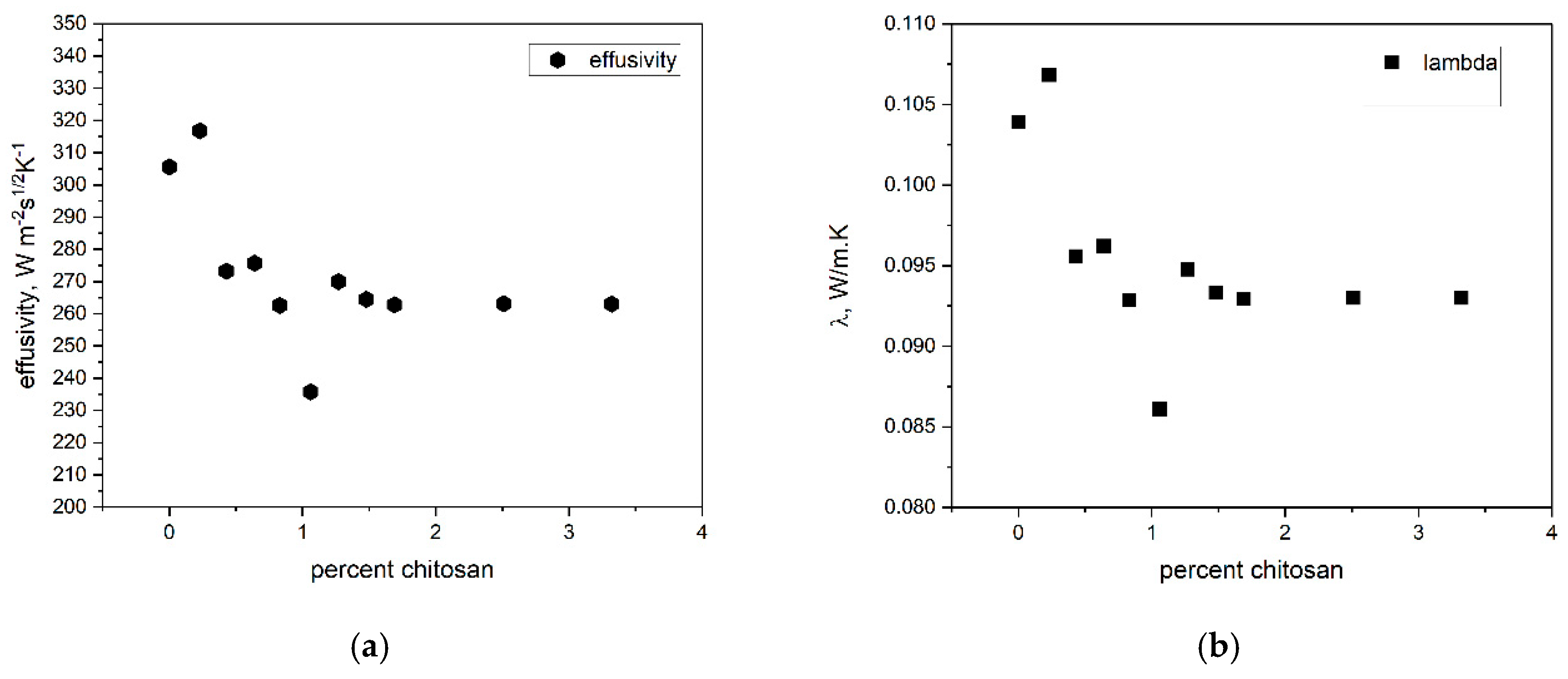

2.4. Thermal Conductivity Measurements

The obtained data provide insight into how chitosan incorporation affects the heat transfer characteristics of the silica gel network, reflecting the interplay between polymer content, water retention, and microstructural organization within the hybrid gels. The obtained values of the thermal conductivity and thermal effusivity of the investigated composites are presented in

Table 1. From the data in (

Table 1) a mean specific heat capacities at constant pressure C

p = 510.47

58.6 J/kg·K for a mean powder density of 1.52

0.1 g / cm

3 is calculated. The deviation from the mean values is most probable connected with variations of the density and contact area in the doped composites. As a reference, the thermal conductivity and effusivity of pure chitosan powders are 0.067 W/m·K and 164.9 Wm

−2s

1/2K

−1, respectively [

20].

Based on the obtained measurements, a quantitative relationship was established between the thermal conductivity and thermal effusivity as a function of the chitosan content in the sol,

Figure 6a,b.

At low chitosan doping levels, a noticeable increase in thermal conductivity and effusivity is observed, most likely associated with a local increase in the density of the composite matrix (

Figure 2). As a reference, the thermal conductivity and effusivity of pure chitosan powders are 0.067 W/m·K and 164.9 W·m⁻²·s¹

/²·K⁻¹, respectively. The addition of chitosan to silica results in a moderate decrease in both thermal conductivity and effusivity with increasing polymer content. Consequently, the lower specific heat capacity (C

p) of the composites compared to pure silica (700–750 J/kg·K) can be explained. Similar observations, as the detected here changes in C

p of silica–chitosan composites relative to pure silica have been discussed in the literature and are attributed to chemical or structural modifications of the matrix [

21,

22]. It is visible, that chitosan addition decreases the thermal capacity, thermal conductivity and effusivity of silica. Variations in the thermal properties of these composites may indicate chemical or structural changes within the material [

23]. As expected, the thermal conductivity of the composites increases slightly with their density (

Table 1).

The thermal properties of the composites are found to depend on the chitosan content, resulting in a moderate decrease in thermal conductivity and effusivity compared to pure silica gels. Thermogravimetric (TGA) and differential thermal analyses (DTA) reveal that the thermal stability and decomposition behavior of the composites are strongly influenced by the amount of chitosan. In particular, the presence of chitosan introduces additional mass-loss steps between 200–300 °C, corresponding to biopolymer decomposition, while higher temperatures (500–700 °C) lead to further degradation and carbonization of residual organic components. These results indicate that chitosan not only modulates the mechanical and optical properties of the silica network but also plays a key role in defining its thermal response.

2.5. SEM Investigations and X-Ray Diffraction

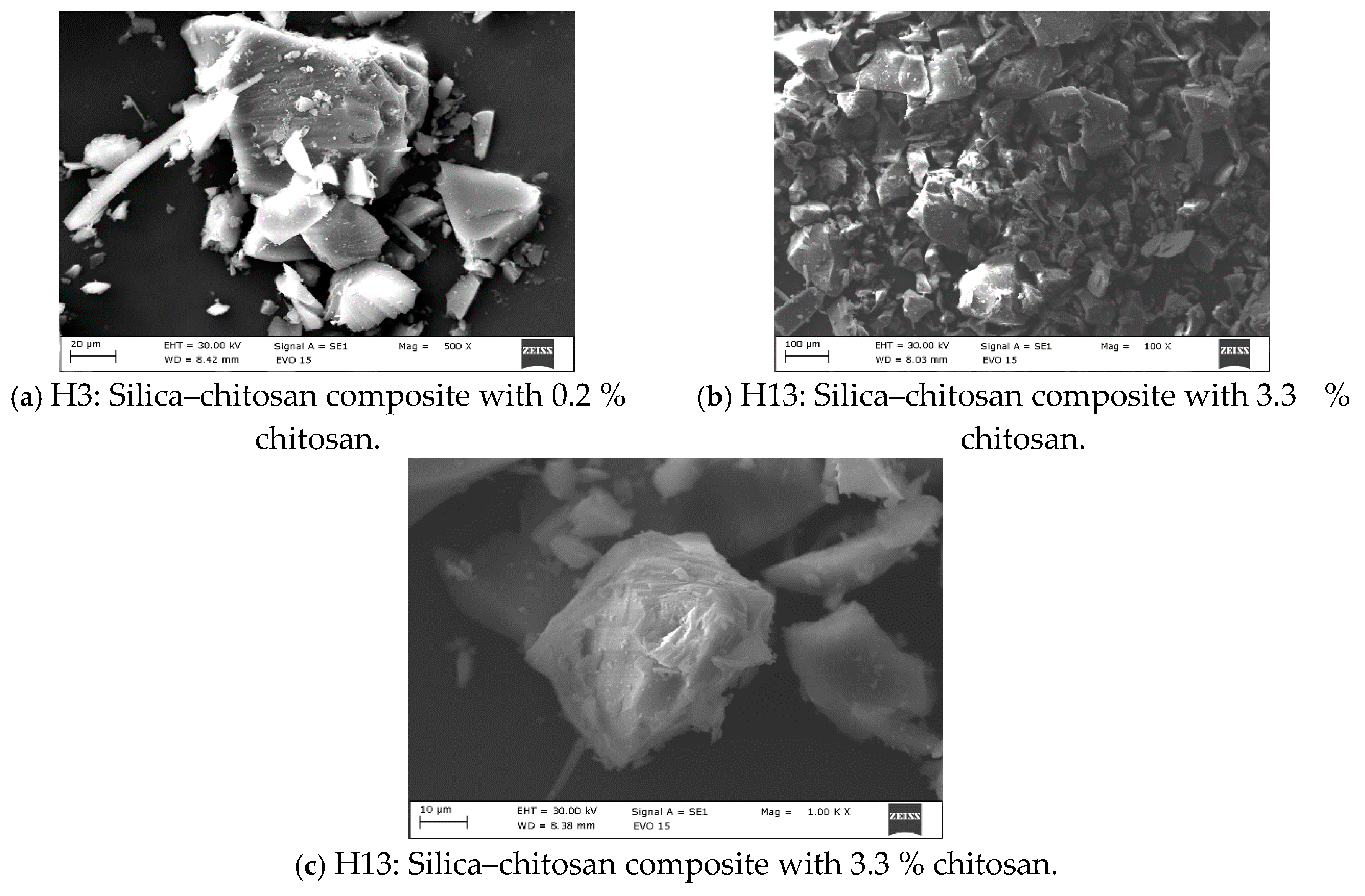

SEM micrographs (

Figure 7) show the characteristic morphology of amorphous silicate gels. The presence of chitosan is not clearly discernible due to its low concentration. The images reveal a porous three-dimensional network formed by interconnected particles, with some regions exhibiting variations in density, most probable responsible for variations of the thermal effusivity of the composites. These observations are consistent with the typical gelation behavior of sol-gel-derived silica composites and corroborate the morphological modifications induced by chitosan incorporation.

An influence of chitosan included in the silicate matrix on its morphology was also observed. The incorporation of chitosan leads to a noticeable modification of the morphology, manifested as densification of the gel network (

Figure 1). These effects are most likely associated with hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions between the amino groups of chitosan and the silanol groups of SiO₂. Such structural rearrangements are expected to enhance the mechanical stability and overall integrity of the composites.

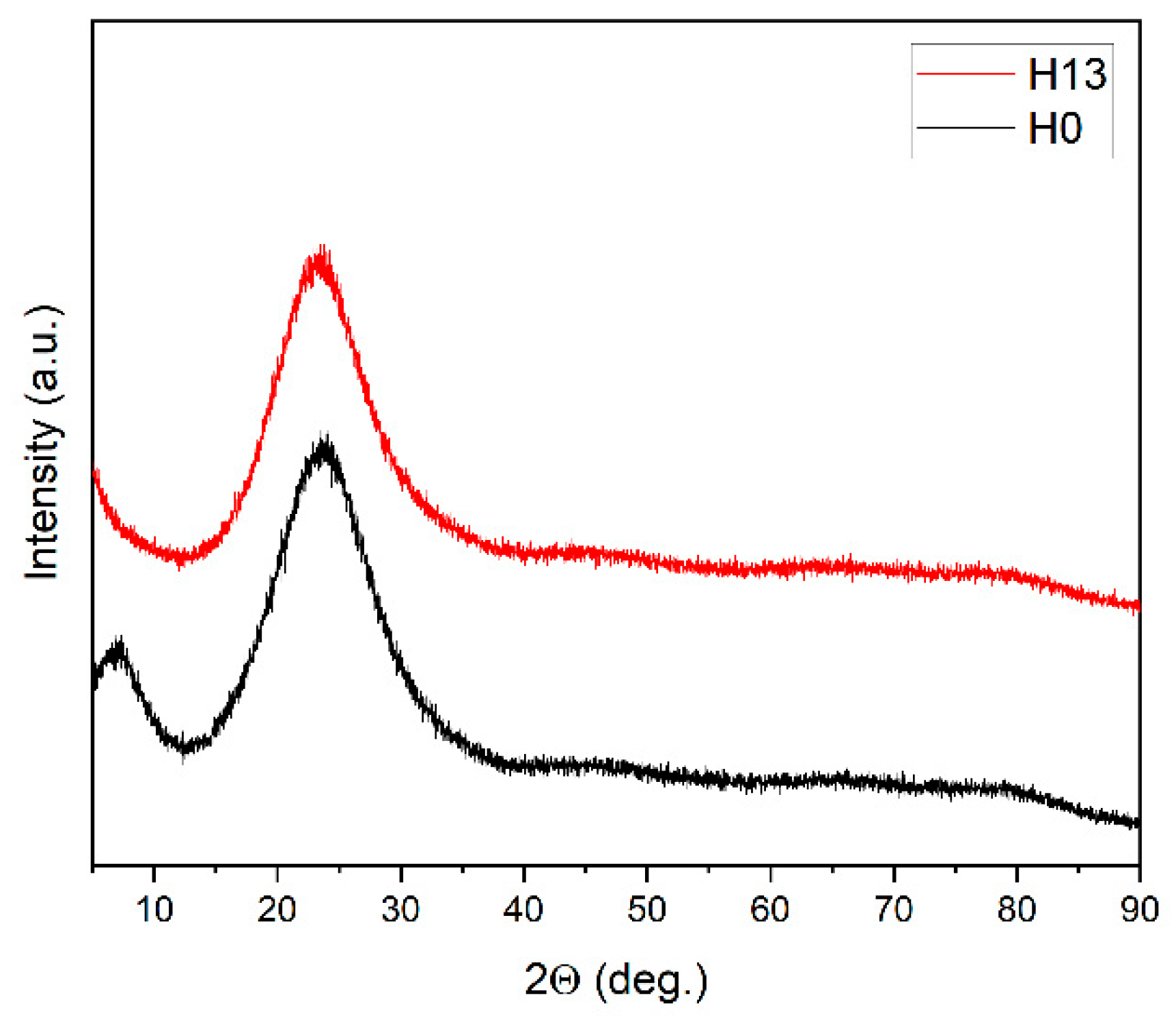

The SEM observations are supported by powder X-ray diffractograms, which demonstrated the amorphous state of the investigated composites (S1). Peaks corresponding to crystalline chitosan are not detected [

24]. Both SEM and X-ray analyses confirmed that the chitosan dopant is homogeneously distributed within the silica matrix.

Representative X-ray diffraction data of composites with a different doping level are shown on

Figure 8.

The figure shows that the amorphous character of the composites is preserved even at relatively high doping levels. For comparison [

7], in silica nanocomposites doped with 1% Eu(phen)₂(NO₃)₃ or Tb(phen)₂(NO₃)₃, the nanocrystalline nature of the dopant is clearly visible, and the appearance of a defective crystal structure associated with the interaction between the dopant and the silicate matrix has been discussed.

The reason for the observed amorphous structure in the present study is the easy amorphization of chitosan, evident from its low glass-transition temperature, Tg = 130–150 °C [

25]. Changes in the conditions of the sol–gel synthesis—such as composition, temperature, and water content—can further facilitate the amorphization of chitosan and thus affect the homogeneity of the resulting composites without altering their functionality. More about the glass-transition temperature of chitosan-related systems, depending on doping and chemical composition can be found in [

26,

27,

28], while in [

29] a review of the thermodynamics and kinetics of glass crystallization is given.

3. Materials and Methods

Chitosan-doped silica gels were prepared via a reproducible sol–gel method at room temperature. A series of silica–chitosan gel composites were synthesized with gradually increasing chitosan concentrations, ranging from 0.2 to 3.3 % concerning the initial sol. The samples were prepared via the sol–gel method, with chitosan introduced as a solution (2% by weight) in acetic acid, during the sol stage. Initially, TEOS was mixed with ethanol in a plastic container, followed by the addition of water and HCl to catalyze the hydrolysis of TEOS. The chemicals were of analytical grade. The mixture was stirred gently at room temperature for 1 hour, allowing the formation of silanol groups (Si–OH). After hydrolysis, chitosan solution was added in varying volumes (0.5–8 mL) to achieve different levels of doping. The mixture was stirred carefully to ensure homogeneity and to prevent air bubble formation. Condensation then occurred, forming a three-dimensional silica network in which chitosan is incorporated via hydrogen bonding and partial chemical interaction with the silanol groups, according to [

30]. The gels were aged at room temperature for 24–48 hours to stabilize the network structure, followed by washing with ethanol or water to remove unreacted precursors. Using this procedure, a series of chitosan-doped aerogels, designated as H2 to H13, were prepared with varying chitosan content. A non-doped gel (H0, table 1) was prodiced in the same way. The densities of the powdered samples H1–H3 were determined using a pycnometer, following a standard procedure with distilled water.

The thermal conductivity and effusivity of the silica–chitosan composite gel monoliths were measured directly using a C-Therm TCi thermal conductivity analyzer, which operates on the Modified Transient Plane Source (MTPS) principle, using a sample holder for liquids, gels and powders. This technique allows rapid and non-destructive evaluation of the thermal transport properties of soft or hydrated materials, such as gels, under ambient conditions and allows the calculation of the specific thermal capacity C

p of the samples. The samples were tested at room temperature immediately. For accuracy, at least five measurements were performed on different areas of each sample, and the results are reported as the mean values with corresponding standard deviations within ±1%. The effusivity and thermal conductivity were obtained experimentally and after that Cp was calculated, using the experimentally obtained density data,

Table 1. The effusivity e

[Ws

1/2m

−2K

−1] is defined by the following equation:

here λ is the thermal conductivity (W·m⁻¹·K⁻¹), ρ is the density (kg·m⁻³) and Cp is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure (J·kg⁻¹·K⁻¹).

The morphology of the synthesized silicon-based gel composites doped with chitosan were examined by a standard scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (Zeiss Evo 15).

Diffuse reflectance measurements were carried out using a PE Lambda 35 spectrometer (PerkinElmer LLC, 940 Winter St Waltham, MA, USA) equipped with a Spectralon® - coated integrating sphere. For all samples, the Kubelka–Munk function F(R) was calculated based on the diffuse reflectance R [

31,

32]. Labsphere Spectralon™ white and black diffuse reflection standards SRS-99–010, SRS-02–010 [54] and a Ho

2O

3 powder were used as a reference. Differential spectra were measured using silica sol-gel powders (H0 sample) as a reference. All spectra are measured at equal spectroscopic conditions (solid state sample holder). The spectra are mathematically treated as overlapping Gaussian curves to find out peak maxima, halfwidths and relative peak intensities.

To study the thermal stability of the gels and gain additional information on their structure, thermogravimetric analysis (TA SDT 650) was applied under a nitrogen atmosphere (200 mL/min) at a 10 C/min scanning rate in the temperature range of 50–1200 oC.

Powder X-Ray studies were performed with Cu-Kα (1.5418 Å) radiation (Empyrean, Malvern Panalytical X-ray diffractometer) at a step of 2θ = 0.05° and counting time of 4 s/step.

4. Conclusions

In this work, silica–chitosan composites are synthesized via a simple, reproducible sol–gel method by varying the chitosan content from 0.2 to 3.3 % relative to silica in the sol. It has been demonstrated that the addition of chitosan influences both the network formation and the final texture of the composites. The materials are comprehensively characterized using UV–Vis spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), TG/DTA analysis, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and thermal conductivity measurements. Increasing the chitosan content lead to an increase in density, accompanied by changes in optical spectra, thermal conductivity, and heat transfer behavior. The observed increase in density is likely correlated with chitosan doping of nanopores within the silica matrix. These findings highlight the potential of silica–chitosan composites not only for thermal insulation, optical, and biocompatible applications, but also as a promising platform for functional optical modifications.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, N.D and S.G. and T.S.; methodology, N.D. and D.S.; software, D.S.; validation, S.G.; investigation, N.D., D.S., S.G. and T.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.D; D.S. and S.G.; writing—review and editing, S.G.; visualization, D.S. and N.D.; supervision, S.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Samples are available.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by European Regional Development Fund under “Research Innovation and Digitization for Smart Transformation” program 2021–2027 under the Project BG16RFPR002-1.014-0006 “National Centre of Excellence Mechatronics and Clean Technologies”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gutzov, S.; Danchova, N.; Karakashev, S. I.; Khristov, M.; Ivanova, J.; Ulbikas, J. Preparation and Thermal Properties of Chemically Prepared Nanoporous Silica Aerogels. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2014, 70, 511–516. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Li, W.; Ling, H.; Zhang, H. A Review of High-Temperature Resistant Silica Aerogels: Structural Evolution and Thermal Stability Optimization. Gels 2025, 11, 357. [CrossRef]

- Butts, D. M.; McNeil, P. E.; Marszewski, M.; Lan, E.; Galy, T.; Li, M.; Kang, J. S.; Ashby, D.; King, S.; Tolbert, S. H.; Hu, Y.; Pilon, L.; Dunn, B. S. Engineering Mesoporous Silica for Superior Optical and Thermal Properties. MRS Energy & Sustainability 2020, 7, E39. [CrossRef]

- Adamski, R.; Siuta, D. Mechanical, Structural, and Biological Properties of Chitosan/Hydroxyapatite/Silica Composites for Bone Tissue Engineering. Molecules 2021, 26, 1976. [CrossRef]

- Apriyanti, E.; Hadiyanto; Wijayanto, W. Preparation and Characterization of Volcanic Ash–Chitosan Composite Ceramic Membrane for Clean Water Production. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 11, 112–118. [CrossRef]

- Apriyanti, E.; Hadiyanto; Wijayanto, W. Preparation and Characterization of Volcanic Ash–Chitosan Composite Ceramic Membrane for Clean Water Production. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 11, 112–118. [CrossRef]

- Danchova, N.; Gutzov, S. Functionalization of Sol–Gel Zirconia Composites with Europium Complexes. Z. Naturforsch., 2014, 69b, 224–230.

- Zhong, T.; Xia, M.; Yao, Z.; Han, C. Chitosan/Silica Nanocomposite Preparation from Shrimp Shell and Its Adsorption Performance for Methylene Blue. Sustainability 2023, 15, 47. [CrossRef]

- Maroulas, K. N.; Goulis, P.; Terzopoulou, Z.; Bikiaris, D. N.; Kyzas, G. Z. Super-Hydrophobic Chitosan/Graphene-Based Aerogels for Oil Absorption. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 390, 123071. [CrossRef]

- Veena, M.; Keerthana, S.; Ponpandian, N. Spectroscopic and microscopic characterizations of chitosan nanoparticles. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomaterials; 2025; pp 95–138. [CrossRef]

- Butts, D. M.; McNeil, P. E.; Marszewski, M.; et al. Engineering Mesoporous Silica for Superior Optical and Thermal Properties. MRS Energy Sustain. 2020, 7, E39. [CrossRef]

- Spassov, T.; Dudev, T. Inclusion Complexes between β-Cyclodextrin and Gaseous Substances—N₂O, CO₂, HCN, NO₂, SO₂, CH₄ and CH₃CH₂CH₃: Role of the Host’s Cavity Hydration. Inorganics 2024, 12, 110. [CrossRef]

- Mei, X.; Li, S.; Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; Cao, Y.; Guro, V. P.; Li, Y. Silica–Chitosan Composite Aerogels for Thermal Insulation and Adsorption. Crystals 2023, 13 (5), 755. [CrossRef]

- Ghazy, A. R. Investigating the differences in the optical properties and laser photoluminescence for chitosan films extracted from two different origins. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2025, 140, 82. [CrossRef]

- Rinaudo, M. Chitin and Chitosan: Properties and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2006, 31, 603–632. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, N. M.; Johan, M. R. Synthesis and Ultraviolet Visible Spectroscopy Studies of Chitosan-Capped Gold Nanoparticles and Their Reactions with Analytes. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 184604. [CrossRef]

- Veena, M.; Keerthana, S.; Ponpandian, N. 3 - Spectroscopic and Microscopic Characterizations of Chitosan Nanoparticles. In Fundamentals and Biomedical Applications of Chitosan Nanoparticles; Deshmukh, K., Dodda, J. M., El-Sherbiny, I. M., Sadiku, E. R., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, 2025; pp. 95–138.

- Thamilarasan, V.; Sethuraman, V.; Gopinath, K.; Balalakshmi, C.; Govindarajan, M.; Mothana, R.; Siddiqui, N.; Khaled, J.; Benelli, G. Single Step Fabrication of Chitosan Nanocrystals Using Penaeus semisulcatus: Potential as New Insecticides, Antimicrobials and Plant Growth Promoters. J. Cluster Sci. 2018, 29. [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, H.; Tafelska-Kaczmarek, A.; Roszek, K.; Czarnecka, J.; Jędrzejewska, B.; Zblewska, K. Fluorescent Chitosan Modified with Heterocyclic Aromatic Dyes. Materials 2021, 14 (21), 6429. [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, B. C. American Mineralogist 1987, 72, 273–279.

- Gutzov, S.; Shandurkov, D.; Danchova, N.; Petrov, V.; Spassov, T. Hybrid Composites Based on Aerogels: Preparation, Structure and Tunable Luminescence. J. Lumin. 2022, 251, 119171. [CrossRef]

- Koh, C. H.; Schollbach, K.; Gauvin, F.; Brouwers, H. J. H. Aerogel composite for cavity wall rehabilitation in the Netherlands: Material characterization and thermal comfort assessment. Build. Environ. 2022, 224, 109535. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, K.; Radoev, B.; Tsekov, R. Transport Coefficients in Composites. Ann. Univ. Sofia, Fac. Chem. 1992, 82, 209–218.

- Naito, P.-K.; Ogawa, Y.; Sawada, D.; Nishiyama, Y.; Iwata, T.; Wada, M. X-Ray Crystal Structure of Anhydrous Chitosan at Atomic Resolution. Biopolymers 2016, 105 (7), 361–368. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Bi, D. Studies on Glass Transition Temperature of Chitosan with Four Techniques. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2004, 93 (4), 1553–1558. [CrossRef]

- Catalán, K. N.; Corrales, T. P.; Forero, J. C.; Romero, C. P.; Acevedo, C. A. Glass Transition in Crosslinked Nano-composite Scaffolds of Gelatin/Chitosan/Hydroxyapatite. Polymers 2019, 11 (4), 642. [CrossRef]

- Glass Transition and Crystallization of Chitosan Investigated by Broadband Dielectric Spectroscopy. Polymers 2022, 17 (20), 2758. [CrossRef]

- Al-Hobaib, A. S.; Saleel, C. A.; Al-Majed, A.; MubarakAli, D.; Varadavenkatesan, T. PVA/Chitosan/Silver Nanoparticles Electrospun Nanocomposites: Molecular Relaxations Investigated by Broadband Dielectric Spectroscopy. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 516. [CrossRef]

- Gutzow, I.; Schmelzer, J. The Vitreous State; Springer Verlag: Berlin, 1995; pp 219–273. ISBN 3-540-59087-0. [CrossRef]

- Budnyak, T. M.; Pylypchuk, I. V.; Tertykh, V. A.; Yanovska, E. S.; Kolodynska, D. Synthesis and adsorption properties of chitosan-silica nanocomposite prepared by sol-gel method. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 87. [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.F.; Huffman, D.R.; Clothiaux, E.E. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles; Willey-VCH: Weinheim,Germany, 2010.

- Labsphere Spectralon®. Diffuse Reflectance Standards Available online: https://www.labsphere.com/product/spectralondiffuse-reflectance-standards/ (accessed on 27 May 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).