1. Introduction

Intercrops, main crops and weeds share the same limited resources, which leads to competition among them. Weeds compete with crops for nutrients, light, water and space [

1]. Due to their suppressive effect, 40% [

2] or even 85% of the yield is lost [

3]. Yield loss depends on the weed species, time of emergence, abundance and crop type [

4]. The spread of weeds results in adverse economic and environmental consequences [

5]. Therefore, weed management throughout the crop growing season remains very important [

6].

Maize is a multifunctional crop that provides food for humans and animal feed [

7,

8]. However, the large part of arable land devoted to maize cultivation poses environmental challenges [

9], as it initiates soil erosion, nitrate leaching and increases phytosanitary risks [

10]. In addition, maize is particularly sensitive to weed competition at the beginning of the growing season [

11]. During this stage, it is necessary to ensure effective weed control to avoid yield losses [

12].

Weed abundance can be safely controlled by applying Integrated Pest Management (IPM) methods: mulching, tillage technologies, mechanical weeding, innovative sowing methods and timing [

13]. Weed population density and biomass can be significantly reduced by applying crop rotation and simple or multiple intercropping systems [

14,

15]. These systems are characterized by higher overall productivity and its stability [

16,

17], because plants use available growth resources – nutrients, water and light – more efficiently [

18,

19].

Legumes are often intercropped with maize [

20] because they provide nitrogen, which is much needed by the main crop [

21]. Maize-legume mixed crops produce more biomass [

22,

23] and higher maize grain yields [

24,

25]. Unfortunately, these intercropping systems cannot completely prevent the spread of weeds [

26] in both conventional and organic farms [

27]. The understanding about specific impacts of intercrops by various botanical families on weed suppression and maize development rate is still not complete. There is also a lack of research on how to combine maize and intercrop botanical families and species with each other in short rotation.

The objectives of our investigations were to: (i) evaluate the effect of different intercrops families and species on weed-suppression capacity and maize development, (ii) assess the strength and direction of the relationships among intercrops, weeds, and maize, and (iii) evaluate the complex effect of short-term intercrop (endogenous) rotations, and identify the most effective schemes for recommendation. The research results will contribute to the development of more diverse and effective IPM strategies in maize crop.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site and Design

A stationary field experiment was carried out at the Experimental Station of Vytautas Magnus University (54°53′N, 23°50′E) during 2023–2025. The soil of experimental field is a light loam (

Endohypogleyic-Eutric) Planosol [

28]. The soil has a pH

HCl ranging from 7.3 to 7.8, a total nitrogen content – 0.08–0.13%, and a humus content – 1.5–1.7%, available phosphorus – 189–280 mg kg⁻¹; available potassium – 97–118 mg kg⁻¹; available sulphur – 1.2–2.6 mg kg⁻¹; and magnesium – 436–790 mg kg⁻¹. The water regime is controlled by subsurface (tile) drainage, and the micro-relief was levelled. The topsoil layer is 27–30 cm thick.

In 2023, maize

(Zea mays L.) was grown in combination with plant species from the

Fabaceae family: faba beans (

Vicia faba L.), crimson clover (

Trifolium incarnatum L.), Persian clover (

Triffolium resupinatum L.), and blue-flowered alfalfa (

Medicago sativa L.) (

Table 1). In 2024, maize was intercropped with species from the

Poaceae family: winter rye (

Secale cereale L.), spring barley (

Hordeum vulgare L.), annual ryegrass (

Lolium multiflorum L.), and common oats (

Avena sativa L.). In 2025, maize was grown with

Brassicaceae family intercrops: white mustard (

Sinapsis alba L.), spring oilseed rape (

Brassica napus L.), oilseed radish (

Raphanus sativus L.) and spring Camelina (

Camelina sativa L.).

The field experiment was conducted in four replicates using a randomized design. The initial plot size was 18.4 m², with a reference area of 18.0 m². A total of 24 plots were established. The experiment was established in a field following a period of bare fallow. In each year of the trial, maize was re-sown, and different companion crops were intercropped between the maize rows.

2.2. Agronomy Practices in the Experiment

In autumn, before the beginning of experimentation, the soil was ploughed by a plough with semi-screw ‘Kverneland’ shares. In spring, when the soil reached physical maturity, it was cultivated with a compound cultivator KLG– 4. Depth 3-4 cm. Maize was sown with a pneumo-mechanical drill ‘Kverneland Accord Optima’ in 45 cm wide rows, distance between seeds – 21 cm. Before loosening the rows, starting doze of mineral fertilizers NPK 5:15:29 were scattered. Fertilizer rate - 300 kg ha

-1. After the maize sprouted, the rows were loosened and the intercrops were sown with a hand seeder for greenhouses, which sows 6 rows. Maize and intercrops were sown according to the planned sowing rates (

Table 1). Maize interrows were loosened; intercrops and weeds were cut one to two times during the maize vegetative season until the maize reached a height of 50 – 70 cm. In 2023 and 2025, the operation was carried out two times, and in 2024 it was performed only once due to the slow development of intercrops under drought conditions. The intercrops were cut with a manual brush cutter "Stihl" FS-550, using a trolley with a protective cover that reduces the operator's load, which evenly spreads the biomass in the interrows and protects the maize crop from mechanical damage. The intercrops were cut when they reached a height of approx. 20-25 cm. No pesticides were used in the agrotechnological system.

2.3. Meteorological Conditions

In terms of precipitation, the territory of Lithuania is in a zone of surplus moisture. On average, 600-650 mm of precipitation falls per year, and about 500 mm evaporates. The warm period lasts 230-260 days.

In 2023 and 2025, the spring was cold and arid, and in 2024 it was warmer and more humid (

Table 2). Unlike in 2023 and 2025, the summer months of 2024 were exceptionally warmer than average. In 2023, only August was wetter than average, while in 2024 and 2025, July experienced above-average rainfall. Precipitation during the maize vegetative period totalled 250 mm in 2023, approximately 280 mm in 2024, and nearly 300 mm in 2025. Although 250 mm of precipitation is sufficient for maize, intercrops growing in our climate exhibit poor growth and produce limited biomass.

The length of the maize growing season was 135 days in 2023, 122 days in 2024 and 156 days in 2025 (from germination at BBCH 09-10 to harvest at BBCH 86-88), due to the dry and excessively warm weather in 2024.

2.4. Methods and Analysis

Coverage of maize interrows. The projected area of maize interrow components (intercrops, weeds and ground) was determined in percentage before each interrow loosening/mulching in at least 4 spots of each plot. A 20×30 cm metal frame was used for the test.

Determination of maize crop development indicators and weediness. It was determined before each interrow loosening or mulching - at least two times during the vegetative season. The maize development stages were assessed according to the BBCH scale [

29], height, fresh and dried biomass of the intercrops and weeds, chlorophyll concentration, etc. For the studies, 5 pcs. of maize plants were cut in each experimental plot. The development stage was assessed visually in at least 10 different spots per plot. The height of the maize plants was measured, they were weighed, thus determining their fresh biomass. Biomass samples were dried in a thermostat at 105° C to determine the dry biomass weight of the plants.

In each experimental plot, biomass samples of the intercrops and weeds were collected from at least four 20x30 cm areas using a metal frame was used to take biomass. Species composition and fresh biomass were assessed in the laboratory. Later, the biomass was dried in the laboratory conditions, and the air-dried biomass was estimated. In the same samples, weed abundance and biomass were evaluated.

Chlorophyll concentration of maize leaves was measured using a chlorophyll content meter MC-100 (‘Apogee Instruments’). It measures the chlorophyll concentration from red (653 nm) to short infrared (931 nm) waves. At least 10 leaves of each plant species were measured.

2.5. Statistical Analysis and Calculations

The research data were statistically evaluated using the one-factor analysis of variance method, correlation and regression methods. The mutual relation of the studied indices was assessed using the correlation analysis method using the STAT ENG program. Correlation coefficients marked ‘*’ mean data significance at a 95% probability level (p ≤ 0.05, ‘**’ mean data significance at a 99% probability level (p ≤ 0.01). The computer program ANOVA was used to determine the limits of the significant difference for the 95 and 99% probability levels according to the F criterion. The differences in the means of treatments marked with a different letter (a, b, c,...) are significant at p≤ 0.05. Calculations were performed at the Agriculture Academy of Vytautas Magnus University.

The complex effect of intercropped plant rotations on weed infestation and maize crop was conducted following the methodologies proposed by G. Lohmann [

30] and K. U. Heyland [

31]. The evaluation involved the following steps: (1) determination of the values for various indicators; (2) transformation of the actual values of each indicator onto a unified nine-point scale, where 1 corresponds to the minimum value and 9 to the maximum value. Intermediate values were assigned scores according to the following formula:

where VBi is the score for a given indicator value, Xi is the expression for a given value, Xmin is the minimum value, Xmax is the maximum value for a given indicator. (3) The indicators converted into scores are presented in grid diagrams with a radius from 1 to 9; (4) the scale also displays the average value of the individual indicators - the score threshold - which is equal to five points, and which distinguishes between the high and the low score. The efficiency of a measurement is indicated by the area bounded by the scores of all its indicators. (5) The calculation of the complex (comprehensive) evaluation index (CEI), which consists of the mean of the scores, the standard deviation of the scores and the standard deviation of the mean of the scores below the cut-off point, has been carried out.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interrow Surface Covering

In our experiment, coverage of maize interrows was established twice during the growing season. In 2023, maize interrows were inter-sown by the leguminous crops. Before the first interrow cutting, the maize interrows were mostly occupied by weeds, and the uncovered area ranged from 41 to 55% because of arid conditions and slow germination rate of intercrops (

Table 3). Intercrops covered 5–11% of the interrow area only. At later stages, the intercrops covered 30 to 54% of maize interrow area and weeds – from 33 to 47%. The maize interrows were most extensively covered by Persian clover – about 54% of the interrow area. Correlation between interrow coverage proportion of intercrops and weeds was weak and mostly related with ground percentage (Supplementary material,

Tables S1-S2).

In 2024, in maize interrows, according to the principles of crop rotation,

Poaceae intercrops were sown, which developed faster than

Fabaceae. Before the first interrow cutting, the intercrops covered up to 52% of the ground surface, but the differences were not significant (

Table 3). A moderate negative correlation was found between interrow coverage and weeds (r=-0.797; p >0.05) (Supplementary material,

Table S1). According to other scientists, intercrops are considered a key weed-management strategy [

32], as they effectively suppress weed growth through competition [

33].

A significant part of the interrows did not regrow after the first cut, except for annual ryegrass, which occupied the largest interrow area - up to 55%. A significant number of oats also sprouted. The correlations between intercrop and weed cover were weak (Supplementary material,

Table S2).

In 2025, plants from another distant family,

Brassicaceae, were sown in the maize interrows. Before the first intercrops cutting, white mustard was particularly abundant, covering up to 74% of the surface area, while weeds occupied only 12%, and 14%of the unoccupied ground remained. A large area of the interrows was also occupied by spring Camelina. The differences were significant (

Table 3). A strong negative correlation was found between the proportions of the area covered by intercrops and weeds (r=-0.965; p ≤ 0.01) (Supplementary material,

Table S1). Before the second harvest (second test), weeds in the C1 plots decreased to 25%, because they were intensively loosened. Mustard showed the greatest decline, dropping to only 3.5%. Radish remained in sufficient quantity - it occupied as much as 53% of the maize interrows (

Table 3). Despite this, the correlations between the proportional areas of the intercrops and weeds became weak.

3.2. The Air-Dried Biomass of Weeds and Intercrops

In 2023,

Fabaceae intercrops developed slowly, resulting in low biomass (

Table 4). Without competition, weeds developed rapidly, reaching a total biomass of 182 g m

-2. After the first interrow cut, when the space between the rows was opened, the intercrops grew up to 37 g m

-2 biomass, but this did not reduce the weed abundance and the correlation between the intercrop and weed biomass was weak (Supplementary material, (

Tables S1-S2). Unlike the findings of our experiment, Bilalis et al. [

34] found that when maize was grown together with leguminous plants, weed density and weed air–dried biomass decreased significantly.

In 2024, the

Poaceae intercrops started quickly and effectively competed with weeds already in the first stages of vegetation, and the biomass of annual ryegrass was even higher than that of weeds (

Table 4). Similarly, Simić et al. [

35] found that in a maize–ryegrass cultivation, weed air–dried biomass decreased by as 12 times compared to the biomass in a single maize crop.

After the first cut, the biomass of winter rye and spring barley significantly decreased two- to fivefold, while ryegrass and oats remained at the similar level. We did not find strong correlations between intercrop biomass, weed biomass, and the percentage of intercrops cover.

In 2025, the air-dry biomass of weeds was lower than in previous years, as

Brassicaceae intercrops effectively covered the maize rows and produced competitive biomass (

Table 4). For example, white mustard and spring Camelina produced about threefold greater biomass than the weeds. As the percentage of row coverage with intercrops and the biomass of intercrops increased, the weed biomass decreased significantly (r=-0.916 and r=-0.839; p ≤ 0.05) (Supplementary material,

Table S1). Before the second interrows cutting, the air-dry biomass of mustard and Camelina decreased by thirteen and two times, respectively, while that of radish even increased by about 33%, so the correlations between the analysed indicators were weak.

3.3. Chlorophyll Concentration in Maize Leaves

Chlorophyll is the main photosynthetic pigment of plants [

36]. The concentration of chlorophyll in leaves has a decisive influence on the photosynthesis process of a plant and plays a key role in determining the physiological state of the plant, biotic and nutritional stress [

37].

In the first year of the experiment (2023), after sowing intercrops of the

Fabaceae family in the maize rows, at the beginning of the vegetation period, maize leaves contained 31-36 µmol m

-2 of chlorophyll and did not differ significantly (

Table 5). Similar results reported Tuure et el. [

38] in experiment with cowpea intercrop. However, Pierre et al. [

39] reported that when maize was grown together with peas, chlorophyl concentration in maize leaves increased by up to 13%. In our experiment, due to the slow development of intercrops, maize experienced less competition. Only the weeds slightly decreased the concentration of chlorophyll in maize leaves (r=-0.426;

p>

0.05) (Supplementary material,

Table S1).

Warm and sunny conditions persisted throughout most of the growing season, resulting in a 0.5- to 2-fold increase in chlorophyll content in maize leaves. The highest chlorophyll content was found in maize without companions (

Table 5). Chlorophyll concentrations were up to 29% lower in crops with legume intercrops. On the contrary, in Nasar et al.'s [

40] studies with alfalfa intercrop, concentration increase was about 37% at the silking stage of maize. In all other maize development stages that differences were weak. Wang et al. [

41] found an increase of just about 5% in maize crops with mung beans. In contrast, Pandey et al. [

42] reported that the lowest chlorophyll concentrations were recorded in single maize crops, and weeds were not controlled at the plots. Correlation analysis of our results revealed a strong negative relationship between the biomass of intercrops and weeds, and the chlorophyll content in maize leaves (r=-0.710, p ≤ 0.05 and r=-0.840, p<0.05) (Supplementary material,

Table S2).

In the second experimental year (2024), after the sowing of

Poaceae intercrops, significantly the highest chlorophyll concentration in maize leaves was found in the control C1 plots without intercrops and weeds, because at other experimental plots companion plants competed with maize (

Table 5), especially weeds (r=-0.959, p<0.01) (Supplementary material,

Table S1). Similarly, in Gou et al. [

43] experiment, competition with wheat reduced chlorophyll content in maize leaves. In the second half of the vegetation, chlorophyll in maize leaves increased and the differences between treatments were no longer pronounced. Nevertheless, similar trends remained, and companion species did not act as major competitors of maize (r=-0.864, p<0.05) (Supplementary material,

Table S2).

Unlike previous years, in the third year of the experiment (2025) at the beginning of the vegetation period, the chlorophyll concentration in maize leaves significantly differed between the treatments with

Brassicaceae intercrops. The highest chlorophyll content was found in maize with radish, rapeseed and mustard companions (

Table 5). Correlations between maize, intercrops and weed biomass were weak (Supplementary material,

Table S1). At later stages, intercrops and weeds competed more strongly with maize (r=-0.758 and r=-0.806; p>0.05), resulting in significantly lower chlorophyll concentration in maize with intercrops, especially in plots with rapeseed, radish and Camelina intercrops.

3.4. Maize Development

Maize is sensitive to environmental conditions, and the most common variable is its height. Our investigations have shown that without companions, maize grew taller, but not always significantly (

Table 6). Similarly, Üstündağ et al. [

44] found that the highest maize height occurred in single crops (224.3 cm), whereas maize grown together with soybean and pea reached a lower height. However, according to Zhang et al. [

45], maize grown together with blue-flowered alfalfa promoted each other's growth. In our experiment, legumes reduced maize height more significantly than plants from other families, but in the maize x companion interaction, weeds exerted a greater effect than intercrops. We found a strong negative relationship between weed air-dried biomass and maize height (r

2023=-0.909, r

2024=-0.864, r

2025=-0.971, p<0.05) (Supplementary material,

Table S2). We also found a strong correlation between maize height and its fresh biomass (r

2023=0.934, r

2024=0.898, r

2025=0.951; p<0.01). During the early flowering stage, the correlation with maize dry biomass was low and statistically weak.

Regardless of the botanical family of the intercrop, all intercrops slowed maize development and reduced average biomass per plant, but the reductions were not consistently significantly. According to Zhang et al. [

46], barley and wheat intercrops slowed maize growth due to increased competition for resources during the early developmental stages. In our experiment, crimson clover, most of

Poaceae family intercrops, and white mustard competed less with maize in this respect (

Table 6). Similar trends were observed for total maize dry biomass. A strong negative interaction was found between air-dried biomass of intercrops of the

Fabaceae family and fresh biomass of maize (r=-0.828; p<0.05), while interactions between intercrops of other families and maize biomass were weak (Supplementary materials,

Table S2). Strong correlations were found between air-dried biomass of weeds (especially annuals) and fresh biomass of maize in all years of the study (r

2023=-0.831, r

2024=-0.946, r

2025=-0.936; p<0.01).

A moderate to strong correlation was found between the chlorophyll concentration in maize leaves and their green biomass (r

2023=0.917, r

2024=0.649, r

2025=0.946) (Supplementary materials,

Table S2).

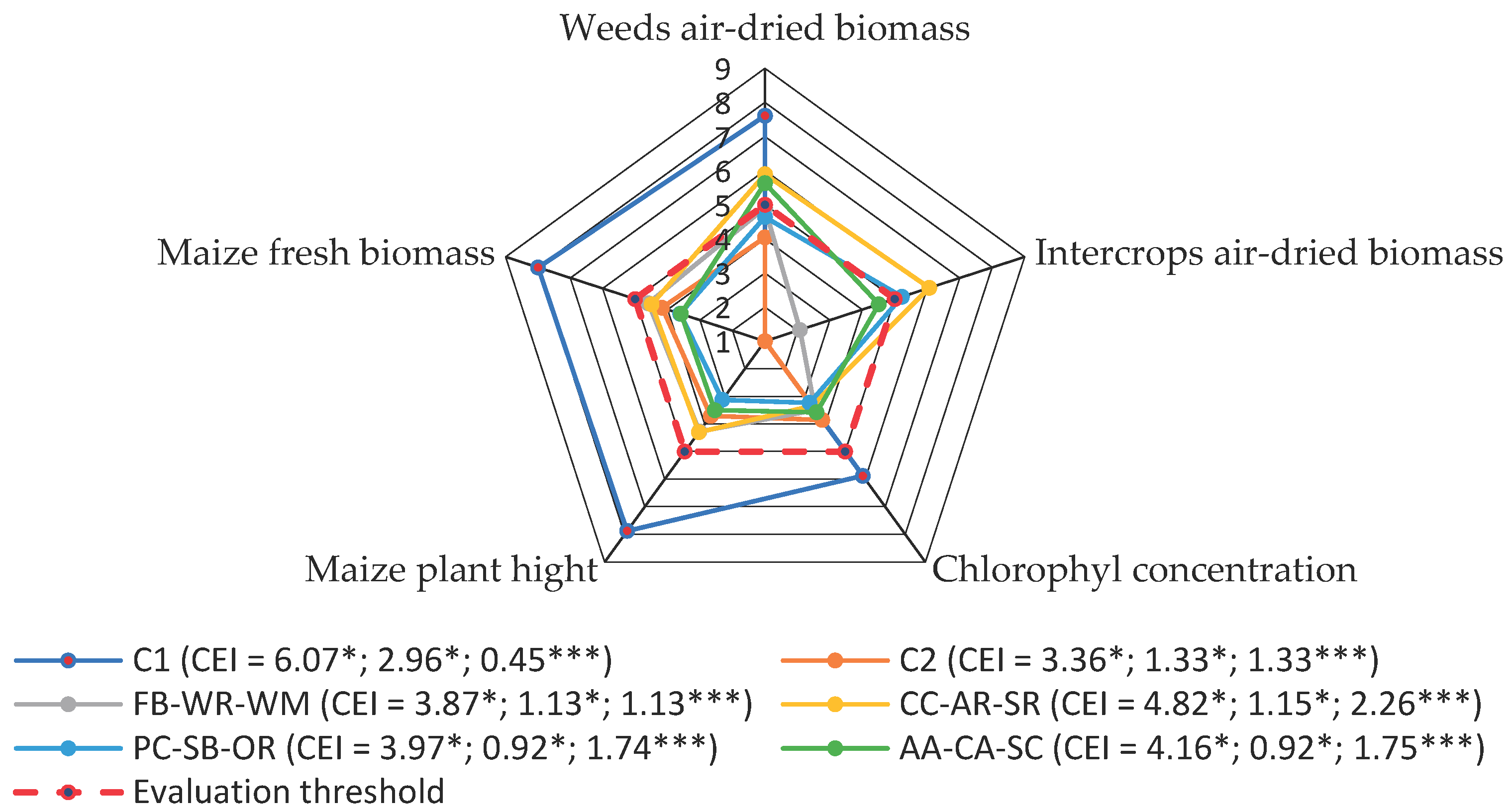

3.5. The Complex Effect of 3-Year Intercrop Rotations

Evaluation of the complex impact of intercrop rotations on crop weediness and maize productivity showed that the traditional technology without competitors (C1) outperformed the other treatments in this respect, due to the absence of intercrops and mechanical weed control (

Figure 1). It should be mentioned that this traditional weed control technology negatively affected soil fertility during the three years of continuous experimentation (data are not presented).

Weed mulching in maize interrows (C2, permacultural treatment) was the least effective for weed control (CEI 3.36), therefore it had negative consequences for maize. The lowest complex evaluation index was also given to the FB-WR-WM and PC-SB-OR intercrop short-term rotations.

The CC-AR-SR intercrop rotation was the most productive, more effective in suppressing weeds and less competitive with maize. The CEI of this rotation was also the highest of all intercrop rotations (4.82). The AA-CA-SC rotation was also quite effective (CEI 4.16), but the final biomass production of the maize crop was reduced due to the negative allelopathy of blue-flowered alfalfa (AA) (data are not shown).

4. Conclusions

Fabaceae intercrops germinated and developed slowly, providing poor coverage of the maize interrows and weak competition with weeds, which covered about 40-50% of maize interrow area. Poaceae intercrops germinated faster and effectively competed with weeds from the early vegetative stage, especially winter rye and spring oats, with ryegrass emerging following the first cut. Brassicaceae intercrops germinated and developed rapidly, especially white mustard, Camelina and oilseed rape. Among Fabaceae plants, the highest dry biomass was produced by Persian and crimson clover (about 86 g m-2) likely because certain seedlings did not survive following harvest. Within the Poaceae intercrops, annual ryegrass produced 200 g m-2 of dry biomass, while among Brassicaceae intercrops, oilseed radishes reached 206 g m-2 of dry biomass. Competition with weeds and intercrops led to a significant reduction in maize growth and chlorophyll concentration, compared to the control C1 plots without both intercrops and weeds. There was found a strong negative correlation between weed air-dried biomass and maize dried biomass (r2023=-0.831, r2024=-0.946, r2025=-0.936; p<0.01). The CC-AR-SR short-term endogenous intercrop rotation was the most productive, more effective in suppressing weeds and less competitive with maize (CEI 4.82). Endogenous crop rotations may serve as a complementary strategy to the IPM Guidelines in the future. It is important to investigate a wider range of intercrop rotations that would develop faster, enhance weed suppression without major losses of the main crop. Consideration of their effects on soil health and the environment should be also considered.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.R.; methodology, K.R. and A.Š.; software, A.S., U.G., J.B. and A.Š.; validation, A.Š., U.G.; formal analysis, U.G., J.B., A.S. and A.Š..; investigation, A.Š., J.B., A.S. K.R., R.K. and U.G.; resources, U.G., A.Š., J.B., R.K., and L.J.; data curation, A.Š., K.R. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Š., L.J., K.R., R.K. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, L.J., K.R., J.B., and A.Š.; visualization, K.R., A.S. and A.Š.; supervision, K.R.; project administration, K.R. and R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Republic of Lithuania, grant “Application of the allelopathic effect in crop agrotechnologies for the implementation of environmental protection and climate change goals”, No. MTE-23-3.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in the

present article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Naeem, M.; Farooq, M.; Farooq, S.; Ul–Allah, S.; Alfarraj, S.; Hussain, M. The impact of different crop sequences on weed infestation and productivity of barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) under different tillage systems. Crop Prot. 2021, 149, 105759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Farooq, S.; Hussain, M. The impact of different weed management systems on weed flora and dry biomass production of barley grown under various barley–based cropping systems. Plants. 2022, 11(6), 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.M. Biological significance of low weed population densities on sweet corn. Agron. J. 2010, 102, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, B.S. Grand challenges in weed management. Front. Agron. 2020, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Thierfelder, C. Weed control under conservation agriculture in dryland smallholder farming systems of southern Africa. A review. Agron Sustain Dev. 2017, 37, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, J.; Ring, H.; Bernhardt, H. Combined Mechanical–Chemical Weed Control Methods in Post-Emergence Strategy Result in High Weed Control Efficacy in Sugar Beet. Agron 2025, 15, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balehegn, M.; Duncan, A.; Tolera, A; Ayantunde, A. A.; Issa, S.; Karimou, M.; Zampaligre, N.; Andre, K.; Gnanda, I.; Varijakshapanicker, P.; Kebreab, E.; Dubeux, J.; Boote, K.; Minta, M.; Feyissa, F.; Adesogan, A. T. Improving adoption of technologies and interventions for increasing supply of quality livestock feed in low-and middle-income countries. Glob. food Secur. 2020, 26, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović, V.; Vasileva, V.; Ljubičić, N.; Rakašćan, N.; Ikanović, J. Environment, soil, and digestate interaction of maize silage and biogas production. Agr. 2024, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, T.W.; Waddington, S.R.; Anderson, C.L.; Chew, A.; True, Z.; Cullen, A. Environmental impacts and constraints associated with the production of major food crops in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia. Food Sec. 2015, 7, 795–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoate, C.; Boatman, N.D.; Borralho, R.J.; Carvalho, C.R.; Snoo, G.R.; de Eden, P. Ecological impacts of arable intensification in Europe. J. Environ. Manag. 2001, 63, 337–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, R. The structure and yield level of sweet corn depending on the type of winter catch crops and weed control method. J. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A.; Iqbal, M. A.; Zafar, M.; Gulzar, A. Appraising economic dimension of maize production under coherent fertilization in Azad Kashmir, Pakistan. Custos e Agronegocio 2019, 15.2, 243–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bogužas, V.; Marcinkevičienė, A.; Pupalienė, R. Weed response to soil tillage, catch crops and farmyard manure in sustainable and organic agriculture. Žemdirbystė–Agri 2010, 97, 43–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bibi, S.; Khan, I. A.; Hussain, Z. A. H. I. D.; Zaheer, S. A. J. J. A. D.; Shah, S. M. A. Effect of herbicides and intercropping on weeds and yields of maize and the associated intercrops. Pak. J. Bot. 2019, 51, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, E. S.; Carlsson, G.; Hauggaard–Nielsen, H. Intercropping of grain legumes and cereals improves the use of soil N resources and reduces the requirement for synthetic fertilizer N: A global– scale analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 1, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eure, P.M.; Culpepper, A.S.; Merchant, R.M.; Roberts, P.M.; Collins, G.C. Weed Control, Crop Response, and Profitability When Intercropping Cantaloupe and Cotton. Weed Technol. 2015, 29, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verret, V.; Gardarin, A.; Pelzer, E.; Médiène, S.; Makowski, D.; Valantin-Morison, M. Can legume companion plants control weeds without decreasing crop yield? A meta-analysis. Field Crops Res. 2017, 204, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betencourt, E.; Duputel, M.; Colomb, B.; Desclaux, D.; Hinsinger, P. Intercropping promotes the ability of durum wheat and chickpea to increase rhizosphere phosphorus availability in a low P soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 46, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C. R.; Longkumer, L. T. Effect of maize (Zea mays L.) and legume intercropping systems on weed dynamics. Int. J. of Bio-resour. stress manag. 2021, 12(5), 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosebi, P.; Ntakatsane, M.; Nkheloane; Loke, T.P. The role of intercropping selected maize cultivars and forage legumes on yield, weed dynamics, and soil chemical properties. Inter. J. of Agr. 2025, 1, 9989566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebede, E. Contribution, utilization, and improvement of legumes–driven biological nitrogen fixation in agricultural. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maitra, S.; Shankar, T.; Banerjee, P. Potential and advantages of maize– legume intercropping system. Maize– production and use 2020, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Schwerdtner, U.; Spohn, M. Interspecific root interactions increase maize yields in intercropping with different companion crops. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2021, 184(5), 596–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uwah, D. F.; Iwo, G. A. Effectiveness of organic mulch on the productivity of maize (Zea mays L.) and weed growth. J Anim Plant Sci. 2011, 21, 525–530. [Google Scholar]

- Begam, A.; Pramanick, M.; Dutta, S.; Paramanik, B.; Dutta, G.; Patra, P. S.; Kundu, A.; Biswas, A. Inter-cropping patterns and nutrient management effects on maize growth, yield and quality. Field Crops Research 2024, 310, 109363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, M. R.; Behera, S. K.; Bastia, D. K.; Behera, B. Impact of organic management practices on productivity, soil quality and weed dynamics in maize and vegetable intercropping systems under rainfed conditions. Biol. Agric. Hortic 2025, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andert, S. The method and timing of weed control affect the productivity of intercropped maize (Zea mays L.) and bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Agri 2021, 11, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUSS Working Group WRB. World Reference Base for Soil Resources. In ternational soil classification system for naming soils and creating legends for soil maps, 4th edition; International Union of Soil Sciences (IUSS): Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, U. Growth Stages of Mono- and Dicotyledonous Plants: BBCH Monograph; Julius Kühn-Institut: Quedlinburg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lohmann, G. Entwicklung Eines Bewertungsverfahrens für Anbausysteme mit Differenzierten Aufwandmengen Ertragssteigernder und Ertragssichernder Betriebsmittel. In Dissertation; (In German). Institut für Pflanzenbau der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn: Bonn, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Heyland, K.U. Zur methodik einer integrierten darstellung und bewertung der produktionsverfahren im pflanzenbau. Pflanzenbauwissenschaften (In German). 1998, 2, 145–159. [Google Scholar]

- Gallandt, E. Weed management in organic farming. Recent Adv. Weed Manag. 2014, 63–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miglécz, T.; Valko, O.; Török, P.; Deak, B.; Kelemen, A.; Donko, A.; Tóthmérész, B. Establishment of three cover crop mixtures in vineyards. Sci. Hortic. 2015, 197, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilalis, D.; Papastylianou, P.; Konstantas, A.; Patsiali, S.; Karkanis, A.; Efthimiadou, A. Weed-suppressive effects of maize–legume intercropping in organic farming. Int. J. Pest Manag. 2010, 56, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, M.; Dragicevic, V.; Chachalis, D.; Željko, D.; Brankov, M. Integrated weed management in long-term maize cultivation. Agric. 2020, 107, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Han, J.; Chen, X.; Shi, L.; Zhang, L. Nondestructive detection of rape leaf chlorophyll level based on Vis-NIR spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2019, 222, 117202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Křížová, K..; Kadeřábek, J.; Novák, V.; Linda, R.; Kurešová, G.; Šařec, P. Using a single-board computer as a low-cost instrument for SPAD value estimation through colour images and chlorophyll-related spectral indices. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 67, 101496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuure, J.; Mganga, K. Z.; Mäkelä, P. S.; Räsänen, M.; Pellikka, P.; Wachiye, S.; Alakukku, L. Maize (Zea mays L.) yields and water productivity as affected by cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp. intercropping over five consecutive growing seasons in a semi-arid environment in Kenya. Agric. Water Manag. 2025, 319, 109779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierre, J. F.; Latournerie-Moreno, L.; Garruna, R.; Jacobsen, K. L.; Labosci, C. A. M.; Us-Santamaria, R.; Ruiz-Sanchez, E. Effect of Maize–Legume Intercropping on Maize Physio-Agronomic Parameters and Beneficial Insect Abundance. Sustain. 2022, 14, 12385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasar, J.; Shao, Z.; Arshad, A.; Jones, F. G.; Liu, S.; Li, C.; Gao, Q. The effect of maize–alfalfa intercropping on the physiological characteristics, nitrogen uptake and yield of maize. Pl. Biol. 2020, 22, 1140–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, H. Optimization of water and fertilizer management on the intercropping system between maize and mung bean to improve photosynthetic characteristics & water use and to increase plant yield. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1597198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, P.; Bajpai, A.; Bhambari, M. C.; Bajpai, R. K. Effect of intercropping on chlorophyll content in maize (Zea Mays L.) and Soybean (Glycine max L.). Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci 2020, 9, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, F.; K van Ittersum, M.; Couedel, A.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; L Van der Putten, P. E.; Zhang, L.; Werf, W. Intercropping with wheat lowers nutrient uptake and biomass accumulation of maize but increases photosynthetic rate of the ear leaf. AoB Plants 2018, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Üstündağ, İ.; Ünay, A. Effect of maize/legume intercropping on crop productivity and soil compaction. Anadolu J. Agr. Sci. 2016, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, G.; Zhao, Q. Differences in maize physiological characteristics, nitrogen accumulation, and yield under different cropping patterns and nitrogen levels. Chil. J. Agr. Res. 2014, 74, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W. P.; Liu, G. C.; sun, J. H.; Zhang, L. Z.; Weiner, J.; Li, L. Growth trajectories and interspecific competitive dynamics in wheat/maize and barley/maize intercropping. Plant Soil. 2015, 397, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).