1. Introduction

Expression of recombinant proteins in

E. coli is one of the most prominent methods in modern biotechnology, widely used in both fundamental studies and practical applications. After expression, recombinant proteins are typically isolated by various approaches, most commonly by chromatography. Despite several decades of protocol optimization, recombinant protein expression is still complicated by issues such as low yield and low solubility. Insufficient protein production often results in its inadequate amount for downstream studies or applications. Low protein solubility frequently necessitates denaturation followed by refolding, which not only complicates purification and increases its cost but also can lead to a loss of specific activity. Among the solutions proposed to overcome these challenges, protein tags remain among the most effective. These tags are small- or medium-sized proteins or protein domains fused to the protein of interest, such as maltose-binding protein (MBP) [

1], glutathione S-transferase (GST) [

2], SUMO [

3], thioredoxin [

4], NusA [

5] and many others. During purification, tags can be removed by proteolytic cleavage to obtain native recombinant proteins. Protein tags are multifunctional, not only directly increasing yield and solubility but also directing recombinant proteins to the periplasm or culture medium (e.g., pelB) [

6], facilitating purification through affinity interactions (e.g., MBP, GST), or even enhancing the functionality of fused proteins, as demonstrated for Sso7d-fused DNA polymerases [

7]. Nevertheless, identifying the optimal protein tag remains largely empirical and must be determined individually for each recombinant protein.

Among available protein tags, CusF was recently proposed as a bifunctional metal-binding protein that increases solubility of fused proteins and binds Cu-charged IMAC resin. CusF is a small periplasmic

E. coli protein (12.3 kDa, 110 aa) that binds Ag⁺ and Cu⁺ ions (K

d 38.5 ± 6.0 nM and 495 ± 260 nM, respectively) and transfers them to the CusCBA efflux pump for export across the outer membrane [

8,

9]. Together with the other proteins of the CusCFBA system, CusF protects

E. coli cells from Cu and Ag toxicity. CusF was reported to be an efficient solubility tag for GFP expression in

E. coli, outperforming MBP and GST, and to bind Cu²⁺-charged IMAC resin [

10]. An enhanced CusF mutant, CusF3H, was later developed to bind His-charged IMAC through the addition of three N-terminal His residues [

11]. However, data on the applicability of CusF for recombinant protein expression and purification remain limited to only a few examples [

11,

12], leaving room for further investigation.

Polyadenylation is an RNA modification involved in RNA decay in prokaryotes. Poly(A) tails serve as recognition signals for nucleases—PNPase, RNase II, and RNase R—which initiate RNA degradation from these tails. Poly(A) polymerase (PAP) [

8] is primarily responsible for polyadenylation in

E. coli [

13]. Only a few PAPs have been characterized from other bacteria, including

Geobacter sulfurreducens [

14],

Pseudomonas putida [

15], and

Bacillus subtilis [

16]. However, only the PAP from

G. sulfurreducens has been cloned, while the other two were purified directly from native hosts. Thus, the diversity of bacterial PAPs remains greatly understudied, even as these enzymes gain increasing interest due to their use in manufacturing mRNA therapeutics. It should also be noted that

E. coli PAP is prone to aggregation and instability in low-salt buffers, making it a difficult target for purification [

13,

17].

Fluorescent proteins are indispensable for numerous applications, including studies of in vivo protein localization and dynamics, cell imaging, and reporting cellular processes. A broad palette of fluorescent proteins has been developed with varying quantum yields and emission wavelengths. They also serve as convenient tools for optimizing protein purification protocols, allowing rapid and visually detectable readouts. One of often used fluorescent proteins, mCherry is a far-red monomeric fluorescent protein engineered from DsRed and widely used for deep-tissue imaging . mCherry is mostly soluble in and expressed in high amounts in

E. coli cells, but has low homology with GFP, being a good alternative to the latter for monitoring the purification efficacy.[

18]

Here, we applied the small metal-binding E. coli protein CusF as a solubility tag for purification of a putative novel poly(A) polymerase from Enterococcus faecalis, a commensal bacterium of the human gastrointestinal tract, as well as for purification of the fluorescent protein mCherry. After cloning the fusion constructs, we expressed them in two E. coli strains and assessed their solubility and ability to bind Cu- and Ni-charged IMAC resins.

2. Results

2.1. Expression of a Putative Efa PAP and Its Fusion with CusF

To identify new bacterial PAPs, we aligned the amino acid sequence of

E. coli PAP-1 using Protein BLAST against proteins from

Bacilli. The search criteria included a length of 400–600 amino acids and the presence of the characteristic bacterial PAP signature motif: [LIV][LIV]G[R/K][R/K]Fx[LIV]h[HQL][LIV]. Candidate proteins containing additional domains were excluded to avoid the presence of unrelated enzymatic activities. The retrieved putative PAPs were ranked based on their similarity to

E. coli PAP-1, and from 223 candidates, we selected a putative PAP from

Enterococcus faecalis (GenBank: EOE33521.1), taking into account the ecological niche of the host.

Enterococcus faecalis is a non-motile, facultatively anaerobic coccus that resides as a commensal organism in the human gastrointestinal tract and is an opportunistic pathogen causing urinary tract infections, endocarditis, and bacteremia. It grows optimally at 6.5% NaCl, 37 °C, and in the presence of 40% bile [

19]. Thus, genomic DNA from this species is relatively easy to obtain. The putative

E. faecalis PAP (Efa PAP) is a 48.5 kDa protein (424 amino acids) with a low isoelectric point (pI 5.29), a strongly negative charge at pH 7.0 (–13.1) and low sequence similarity to

E. coli PAP-1 (35.41%). The coding sequence of Efa PAP was cloned into the pET23a vector; however, recombinant Efa PAP was insoluble after expression in

E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS and Rosetta 2 (DE3) strains at both 25 °C and 37 °C (

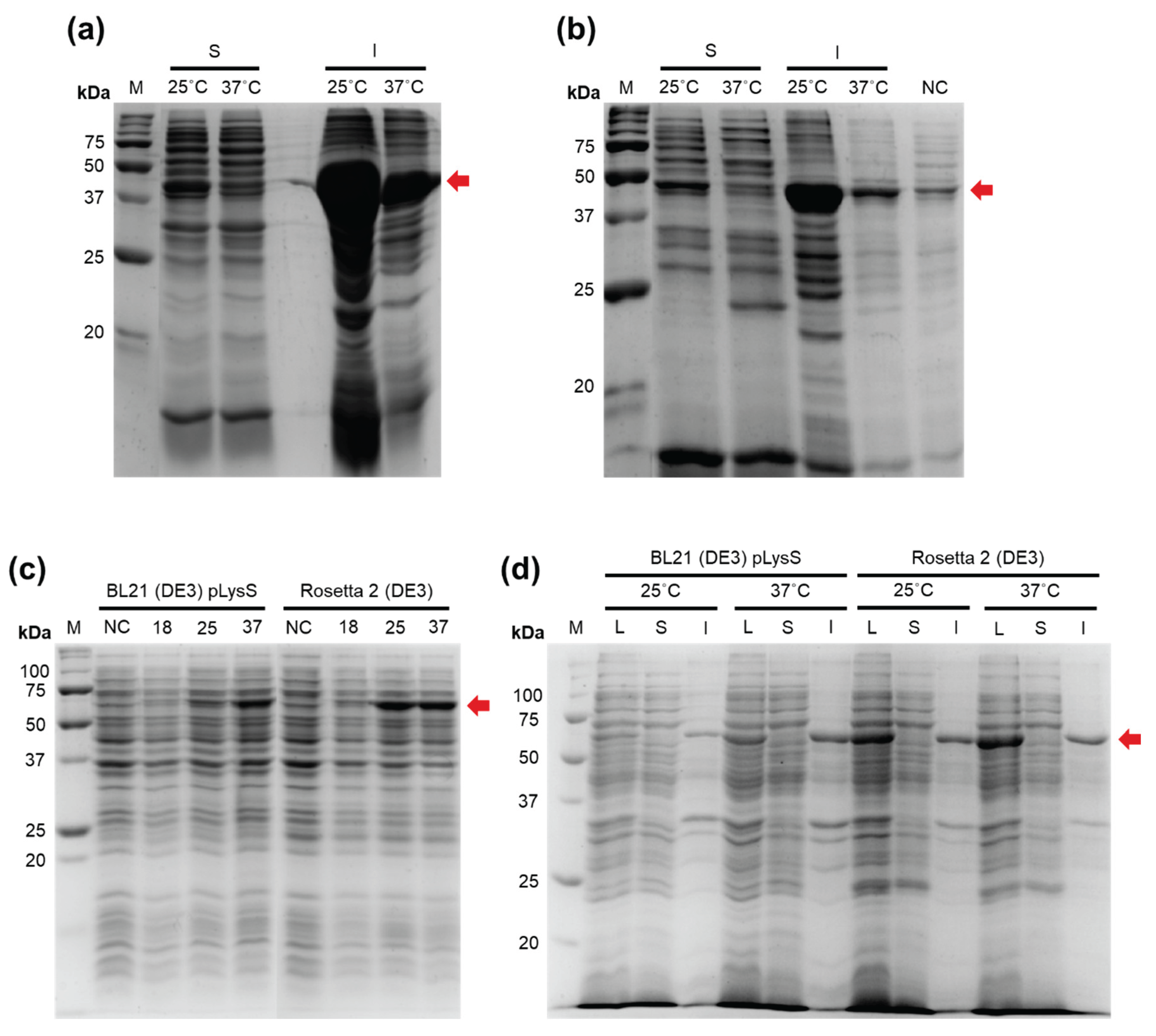

Figure 1a,b).

To increase the solubility of Efa PAP, we fused the protein with CusF, a Cu-binding protein previously reported as a solubility tag capable of binding Cu-charged IMAC resin, thereby potentially improving both solubility and suitability for metal-chelate chromatography. The fusion construct was cloned into the pET36b vector and expressed in the same

E. coli strains used for Efa PAP (

Figure 1c,d). However, the CusF–Efa PAP fusion protein was also completely insoluble, regardless of the strain or induction temperature. It should be noted that we did not detect poly(A) polymerase activity under conditions similar to those used for

E. coli PAP-1, either in lysates with Efa PAP or in lysates with the CusF–Efa PAP fusion protein (data not shown). Therefore, the possible impact of CusF on the specific activity of Efa PAP remains unknown.

2.2. Expression and Binding with IMAC of a CusF-mCherry Fusion

After the unsuccessful attempts to obtain soluble Efa PAP, we fused CusF to mCherry, a DsRed-derived fluorescent protein, as a model substrate similar to GFP—the protein originally used to demonstrate the applicability of CusF as a solubility tag. The CusF–mCherry fusion protein was expressed in

E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS and Rosetta 2 (DE3) strains, and the resulting lysates were incubated with either Cu²⁺-charged or Ni²⁺-charged IMAC resin (

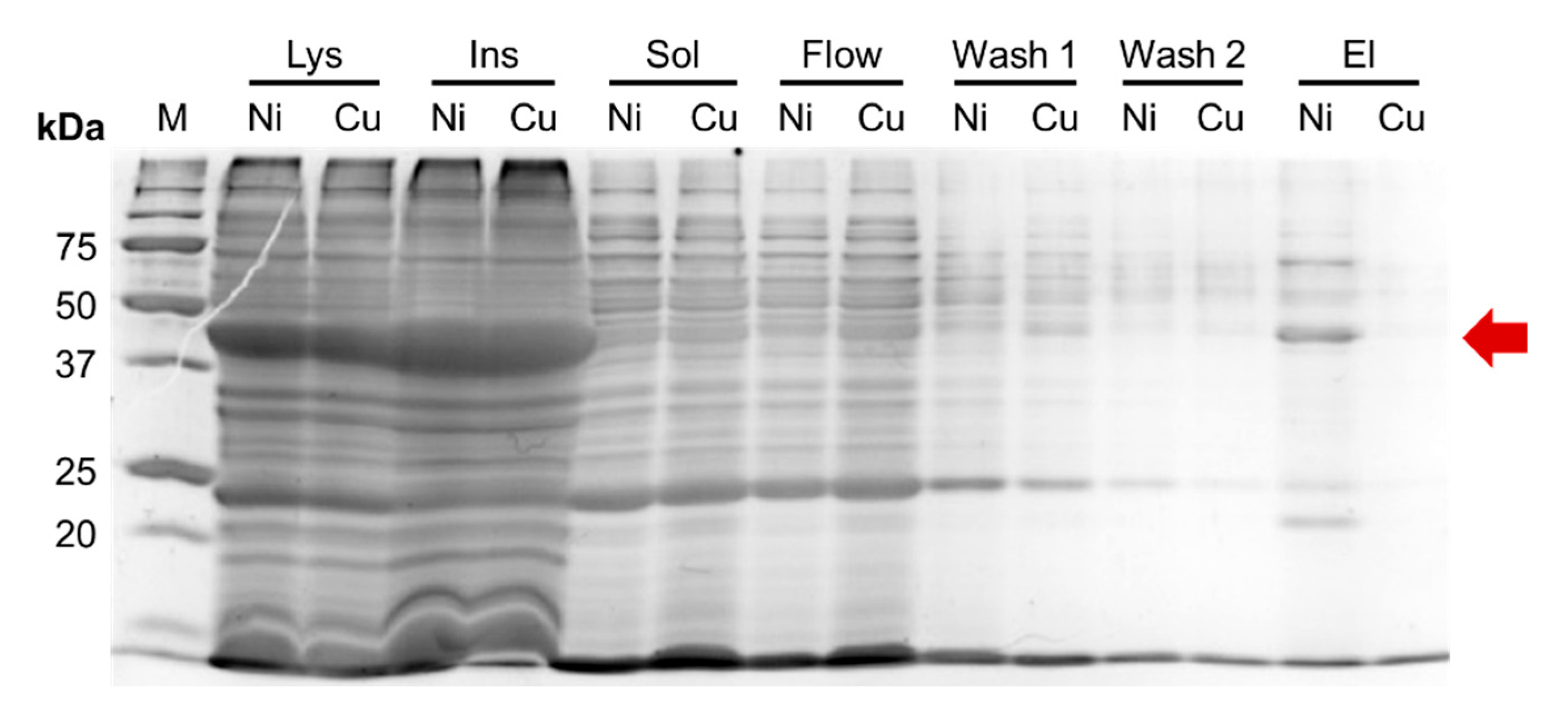

Figure 2).

As observed for CusF–Efa PAP, the CusF–mCherry fusion protein was largely insoluble after expression and was nearly undetectable in the soluble protein fraction. However, the soluble fractions showed a faint red coloration, indicating the presence of small amounts of CusF–mCherry. We therefore proceeded to test the binding of the soluble material to IMAC resins charged with different metal ions. No CusF–mCherry was eluted from Cu²⁺-charged IMAC resin, as confirmed by SDS–PAGE, and the corresponding elution sample showed no visible red coloration. In contrast, a moderate band at the expected molecular weight of CusF–mCherry (approximately 40 kDa) was detected after elution from Ni²⁺-charged IMAC resin, and this sample exhibited a clear red hue. Since the CusF–mCherry construct includes a C-terminal His-tag originating from the pET36b vector, this tag is likely responsible for the observed binding to Ni²⁺-charged IMAC. Thus, the CusF–mCherry fusion protein remained almost completely insoluble and did not bind to Cu²⁺-charged IMAC resin, while retaining the ability to bind Ni²⁺-charged IMAC via its C-terminal His-tag.

3. Discussion

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins are essential components of modern life sciences and biotechnology. High-yield production of soluble recombinant proteins facilitates purification as well as subsequent functional studies and practical applications. Although a broad range of strategies has been proposed for optimizing recombinant protein production, no universal solution has yet been found for consistently obtaining proteins in the desired soluble form. Protein solubility tags are no exception; they also possess limitations, such as large size (e.g., 42 kDa MBP or 55 kDa GST), thermal instability of mesophilic tags, interference with the activity of fused proteins, and challenges with tag removal due to incomplete proteolytic cleavage (e.g., by TEV protease). Among these limitations, unpredictable solubilization efficacy and variable expression yields remain particularly difficult to address, as the performance of a given tag cannot be reliably predicted for a new protein. In this context, parallel testing of multiple tags for a single protein is often the most effective strategy, underlining the need for empirical data on the performance of different tags.

We first employed CusF as a solubility tag for a putative poly(A) polymerase

from E. faecalis. Its cognate proteins,

E. coli PAP-1 and tRNA nucleotidyltransferase, are known to be aggregation-prone and unstable when stored in low-salt buffers [

13,

17,

20]. Our previous attempts to solubilize Efa PAP using either MBP or GST fusions were unsuccessful, prompting us to use CusF, which had been reported as a promising solubility tag and was expected to facilitate purification via metal-chelate chromatography. However, the CusF–Efa PAP fusion protein remained almost completely insoluble, similar to unfused Efa PAP. The reason for this failure is unclear, as the molecular weight and pI of Efa PAP are comparable to those of GFP—the protein originally used in the proof-of-concept study demonstrating successful solubilization by CusF [

10] (48.5 kDa and pI 5.29 vs 27 kDa and pI 5.9, respectively). Strain-specific effects are also unlikely, as we used the same BL21 (DE3) strain reported in earlier work, and the pLysS plasmid typically does not reduce recombinant protein solubility.

To further assess the solubilization potential of CusF, we used mCherry as a fusion partner. mCherry, a DsRed-derived fluorescent protein from

Discosoma sp., shares the β-barrel fold of GFP despite having low sequence identity (22%). It is generally expressed in

E. coli as a highly soluble protein, making it a suitable model. Surprisingly, the CusF–mCherry fusion was also nearly completely insoluble. Moreover, the chimeric protein did not bind to Cu²⁺-charged IMAC resin, contrary to previous reports. A plausible explanation is that CusF has relatively weak affinity for Cu(II) ions and preferentially binds Ag(I); for Cu(I), the K

d is approximately tenfold higher, and the reported K

d for Cu(II) is about fivefold lower than for Cu(I) [

8]. The Cu²⁺ concentration on our IMAC resin may therefore have been insufficient for efficient CusF binding, unlike the conditions used by Cantu-Bustos et al. Regarding solubility, one might attribute poor solubility to insufficient ionic strength of the lysis buffer; however, mCherry is typically purified in 150–300 mM NaCl, and we used 300 mM NaCl in our experiments.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. First, we evaluated only two proteins as fusion partners for CusF, and both—Efa PAP and mCherry—are moderately sized proteins with acidic pI values (5–6). Other proteins, particularly basic proteins, might exhibit improved solubility when fused to CusF. Second, we did not systematically optimize lysis conditions (e.g., pH, ionic strength, detergents), which can strongly influence solubility; higher ionic strength may improve the solubility of CusF fusions. Third, we did not extensively test CusF–mCherry binding to Cu²⁺-charged IMAC under varied conditions. Adjustments such as pH optimization or the use of chaotropic agents might yield improved results. Nonetheless, despite these limitations, we believe the presented findings are valuable. Proof-of-concept studies typically emphasize successful cases, whereas negative or unsuccessful outcomes—such as failed solubilization attempts—are underreported. Thus, we decided to publish our unsuccessful attempts to use CusF as a solubility tag in order to share limitations of this approach which can be helpful to other scientists in planning their experiments. It should be also noted that in the context of rapid advances in AI-driven protein design, lack of empirical negative data may hinder the development and training of computational models, as the models will have only positive results.

In summary, we provide insights into the performance of CusF as a solubility tag using two model proteins—a putative poly(A) polymerase from E. faecalis and the fluorescent protein mCherry. In both cases, fusion with CusF did not improve solubility, and CusF–mCherry did not bind to Cu²⁺-charged IMAC resin. These results demonstrate that, similar to MBP, GST, and other protein tags, CusF does not guarantee soluble expression of its fusion partner, highlighting the importance of testing multiple tags to achieve optimal protein yields.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Search and Selection of E. faecalis PAP Coding Sequence

Amino acid sequence of

E. coli PAP-1 was used as a reference for search of potential bacterial PAPs using Protein BLAST against proteins from

Bacilli. Criteria for cloning were length 400-600 a.a., the presence of all PAP structural domains (head, neck, body and leg), conservative positions corresponding to D69, D71, E108 involved in catalysis in PAP I

E. coli [

21], characteristic signature of bacterial PAPs [LIV][LIV]G[R/K][R/K]Fx-[LIV]h[HQL][LIV] [

22].

4.2. Cloning of E. faecalis polyA Polymerase, mCherry, CusF and Chimeric Proteins

The coding sequence of

E. faecalis PAP-1 (GenBank: EOE33521.1) was amplified using pcnB-Efe-F/pcnB-Efe-R primers (

Table 1) with NdeI and NotI restriction sites, allowing the in-frame ligation into the pET23a vector (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA). PCR was carried out using genomic DNA of

E. faecalis as a template. The resultant 1.3-kbp DNA fragment and pET23a vector were digested with NdeI and NotI (SibEnzyme, Novosibirsk, Russia), ligated, and transformed into

E. coli XL1-Blue cells according to the standard protocols [

23]. The fidelity of the resulting recombinant plasmid named pPAP-Efa was confirmed by sequence analysis using primers pET-F and pET-R (

Table 1) using the Big Dye Terminator kit 3.1 (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) and ABI 3730 genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) in the laboratory of antimicrobial drugs at ICBFM SB RAS according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The coding sequences of mCherry and CusF were amplified (mCherry-F/mCherry-R and CusF-F/CusF-R (

Table 1), respectively) and cloned using the same procedure into pET23a (NdeI and NotI) and pET36b (NdeI and KpnI), respectively, resulting in plasmids pmCherry and pCusF.

For construction of the fusion proteins CusF-mCherry and CusF-Efa-PAP, the coding sequences of mCherry and Efa PAP were amplified (CusF-mCherryOr-F1/CusF-mCherryOr-R1 and CusF-Efa-PAP-F/mCherry-R (

Table 1), respectively) and cloned into pCusF HindIII/XhoI and NcoI/NotI, respectively, resulting in plasmids pCusF-mCherry and pCusF-PAP-Efa.

4.3. Expression of a Putative Efa PAP, CusF-Efa PAP, CusF-mCherry

A starter culture of E. coli BL21 (DE3) pLysS and (Promega, WI, Madison, USA) Rosetta 2 (DE3) (Novagen, WI, Madison, USA) strains harboring the plasmids pPAP-Efa, pCusF-mCherry, pCusF-PAP-Efa were grown to OD600 = 0.8 in LB medium with 100 μg/mL ampicillin (pPAP-Efa) or 50 μM kanamycin (pCusF-mCherry, pCusF-PAP-Efa) at 37 °C. In 4 1L flasks, 1 L of LB with 100 μg/mL ampicillin or 50 μM kanamycin was inoculated with 4 ml of the starter culture, and the cells were grown to OD600 = 0.6 at 37 °C. The expression of recombinant proteins was induced by adding IPTG up to 1 mM concentration. After induction for 12 h at 37 °C, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g and stored at −70 °C.

4.4. Solubility Test

To evaluate solubility of the fusion proteins in different E. coli strains, cell pellets after expression in 1 mL night cultures were lysed in 200 μl of a lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, 5% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-Mercaptoethanol). The cell pellets were resuspended in the lysis buffer following addition of lysozyme to a 1.0 mg/ml and incubation for 1 hour at 37 °C. The incubated probes were sonicated and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min. Soluble fractions were transferred into new tubes, and insoluble pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of the lysis buffer. Both soluble and insoluble fractions were analyzed using SDS-PAGE.

4.5. Binding of CusF-mCherry with Ni2+- and Cu2+-Charged IMAC Resin

For protein purification, the cell pellet was resuspended in 10 mL of the lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF, 5% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM imidazole, 5 mM β-Mercaptoethanol) supplied by 1 mg/ml lysozyme, incubated for 30 min on ice followed by sonication. After lysis, the soluble fraction was separated by two consequent centrifugation steps at 20,000×g for 30 min following binding with Ni2+- or Cu2+-charged IMAC resin (Bio-Rad, CA, Hercules, USA) pre-equilibrated with the lysis buffer. The resins were washed twice by the lysis buffer following elution of bound proteins were eluted by an elution buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5 M imidazole, 5 mM β-Mercaptoethanol). All the fractions from each step were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

5. Conclusions

To sum up, CusF did not improve the solubility of either a putative E. faecalis poly(A)-polymerase or mCherry, and CusF-mCherry did not bind Cu²⁺-charged IMAC resin under the used conditions. These results demonstrate that CusF is not a universally effective solubility tag as other previously suggested to the same purpose proteins like MBP, GST, thioredoxin, etc. The presented results underline the importance of empirical testing multiple tags as being essential for achieving optimal recombinant protein yield.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.F. and I.P.O.; methodology, I.P.O., M.S.K. and M.A.S.; validation, I.P.O.; formal analysis, I.P.O. and M.A.S.; investigation, M.S.K. and M.A.S.; resources, M.L.F.; data curation, I.P.O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.P.O.; writing—review and editing, M.L.F.; visualization, M.S.K. and M.A.S.; supervision, I.P.O.; project administration, M.L.F.; funding acquisition, I.P.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research and the APC were funded by Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-24-00389, https://www.rscf.ru/project/24-24-00389.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request due to the restrictions (e.g., privacy, legal or ethical reasons).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| Efa |

Enterococcus faecalis |

| PAP |

poly(A)-polymerase |

References

- Kapust, R.B.; Waugh, D.S. Escherichia Coli Maltose-Binding Protein Is Uncommonly Effective at Promoting the Solubility of Polypeptides to Which It Is Fused. Protein Sci. 1999, 8, 1668–1674. [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.B.; Johnson, K.S. Single-Step Purification of Polypeptides Expressed in Escherichia Coli as Fusions with Glutathione S-Transferase. Gene 1988, 67, 31–40. [CrossRef]

- Butt, T.R.; Edavettal, S.C.; Hall, J.P.; Mattern, M.R. SUMO Fusion Technology for Difficult-to-Express Proteins. Protein Expr. Purif. 2005, 43, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- LaVallie, E.R.; Lu, Z.; Diblasio-Smith, E.A.; Collins-Racie, L.A.; McCoy, J.M. Thioredoxin as a Fusion Partner for Production of Soluble Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia Coli. Methods Enzymol. 2000, 326, 322–340. [CrossRef]

- Davis, G.D.; Elisee, C.; Newham, D.M.; Harrison, R.G. New Fusion Protein Systems Designed to Give Soluble Expression in Escherichia Coli. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1999, 65, 382–388.

- Power, B.E.; Ivancic, N.; Harley, V.R.; Webster, R.G.; Kortt, A.A.; Irving, R.A.; Hudson, P.J. High-Level Temperature-Induced Synthesis of an Antibody VH-Domain in Escherichia Coli Using the PelB Secretion Signal. Gene 1992, 113, 95–99. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Prosen, D.E.; Mei, L.; Sullivan, J.C.; Finney, M.; Vander Horn, P.B. A Novel Strategy to Engineer DNA Polymerases for Enhanced Processivity and Improved Performance in Vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32, 1197–1207. [CrossRef]

- Kittleson, J.T.; Loftin, I.R.; Hausrath, A.C.; Engelhardt, K.P.; Rensing, C.; McEvoy, M.M. Periplasmic Metal-Resistance Protein CusF Exhibits High Affinity and Specificity for Both Cu I and Ag I. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 11096–11102. [CrossRef]

- Franke, S.; Grass, G.; Rensing, C.; Nies, D.H. Molecular Analysis of the Copper-Transporting Efflux System CusCFBA of Escherichia Coli. J. Bacteriol. 2003, 185, 3804–3812. [CrossRef]

- Cantu-Bustos, J.E.; Vargas-Cortez, T.; Morones-Ramirez, J.R.; Balderas-Renteria, I.; Galbraith, D.W.; McEvoy, M.M.; Zarate, X. Expression and Purification of Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia Coli Tagged with the Metal-Binding Protein CusF. Protein Expr. Purif. 2016, 121, 61–65. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Cortez, T.; Morones-Ramirez, J.R.; Balderas-Renteria, I.; Zarate, X. Production of Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia Coli Tagged with the Fusion Protein CusF3H. Protein Expr. Purif. 2017, 132, 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Kramberger-Kaplan, L.; Austerlitz, T.; Bohlmann, H. Positive Selection of Specific Antibodies Produced against Fusion Proteins. Methods Protoc. 2020, 3. [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.J.; Sarkar, N. Identification of the Gene for an Escherichia Coli Poly(A) Polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992, 89, 10380–10384. [CrossRef]

- Bralley, P.; Cozad, M.; Jones, G.H. Geobacter Sulfurreducens Contains Separate C- and A-Adding TRNA Nucleotidyltransferases and a Poly(A) Polymerase. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 109–114. [CrossRef]

- Payne, K.J.; Boezi, J.A. The Purification and Characterization of Adenosine Triphosphate Ribonucleic Acid Adenyltransferase from Pseudomonas Putida. J. Biol. Chem. 1970, 245, 1378–1387.

- Sarkar, B.; Cao, G.; Sarkar, N. Identification of Two Poly (A) Polymerases in Bacillus Subtilis. IUBMB Life 1997, 41, 1045–1050. [CrossRef]

- Sippel, A.E. Purification and Characterization of Adenosine Triphosphate: Ribonucleic Acid Adenyltransferase from Escherichia Coli. Eur. J. Biochem. 1973, 37, 31–40. [CrossRef]

- Shaner, N.C.; Campbell, R.E.; Steinbach, P.A.; Giepmans, B.N.G.; Palmer, A.E.; Tsien, R.Y. Improved Monomeric Red, Orange and Yellow Fluorescent Proteins Derived from Discosoma Sp. Red Fluorescent Protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004, 22, 1567–1572. [CrossRef]

- García-Solache, M.; Rice, L.B. The Enterococcus: A Model of Adaptability to Its Environment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 32. [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.Y.; Maizels, N.; Weiner, A.M. Recovery of Soluble, Active Recombinant Protein from Inclusion Bodies. Biotechniques 1997, 23, 1036–1038. [CrossRef]

- Jones, G.H. Acquisition of PcnB [Poly(A) Polymerase I] Genes via Horizontal Transfer from the β, γ-Proteobacteria. Microb. Genomics 2021, 7. [CrossRef]

- Martin, G.; Keller, W. Sequence Motifs That Distinguish ATP(CTP):TRNA Nucleotidyl Transferases from Eubacterial Poly(A) Polymerases. RNA 2004, 10, 899–906. [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.A. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Second Edition. Volumes 1, 2, and 3. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Volumes 1 and 2; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: New York, 1990; Vol. 61; ISBN 13: 978-0879693091.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).