Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

10 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection

2.2. Cell Isolation

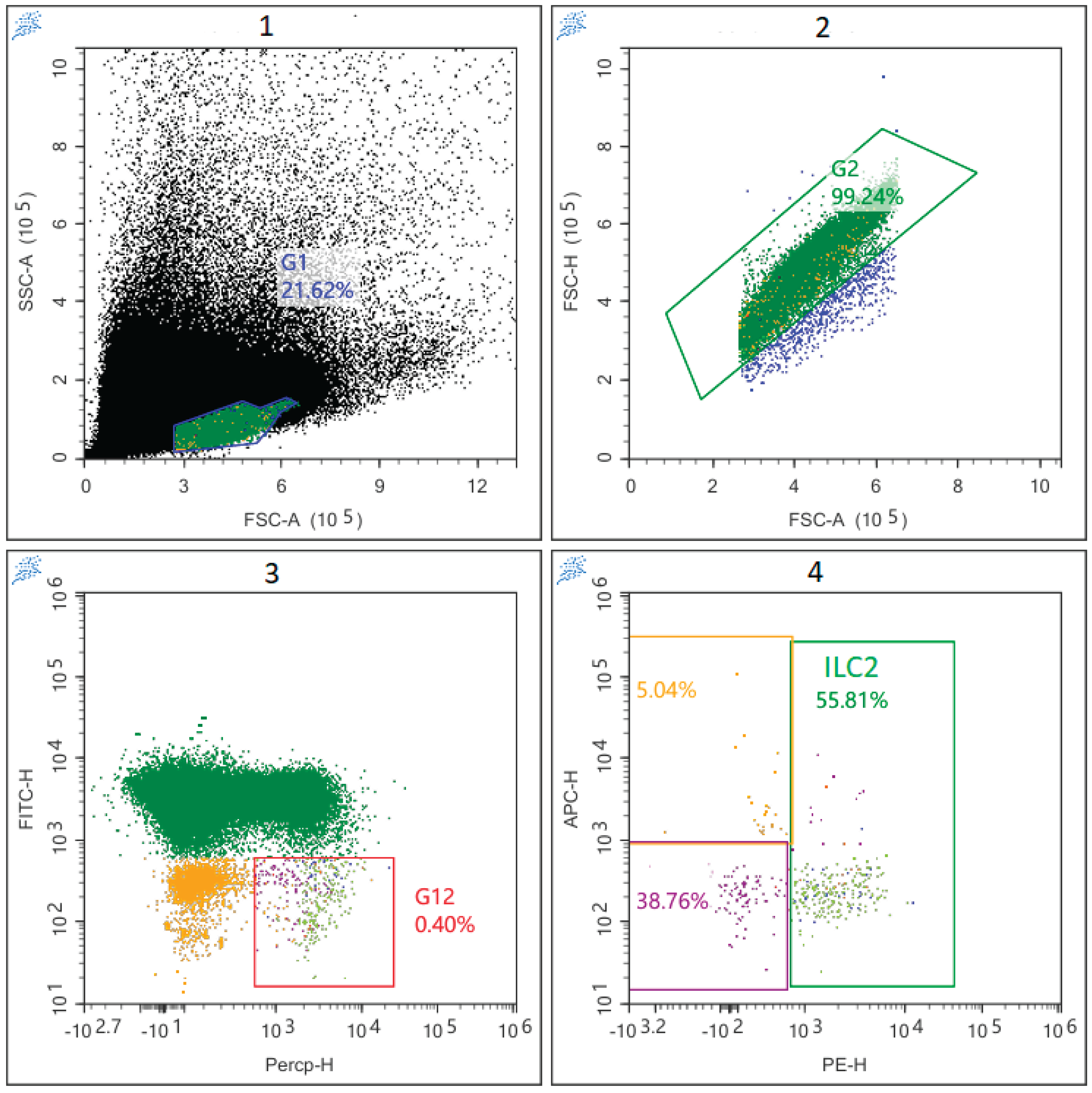

2.3. Cell Staining and Flow Cytometry

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

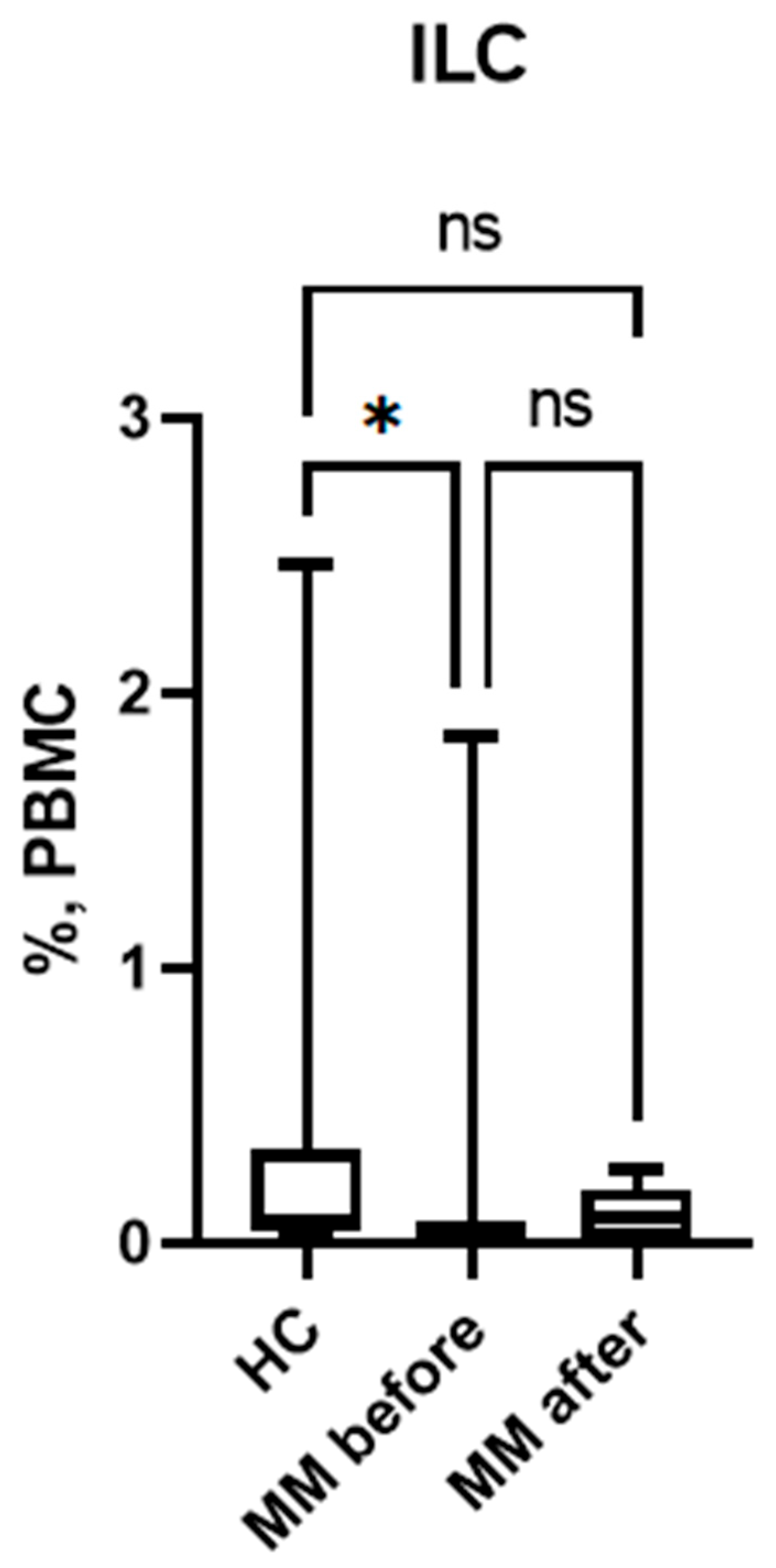

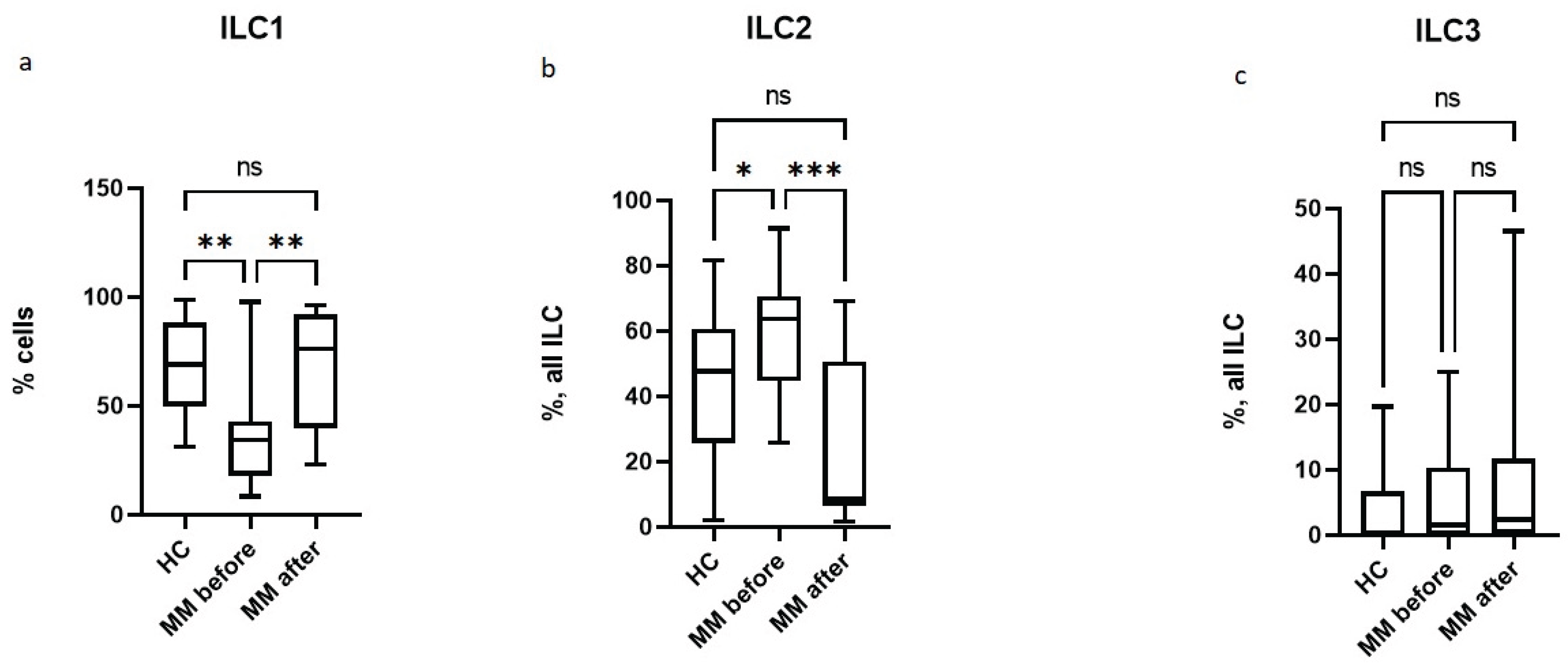

3.1. Subpopulation Composition of ILC Before and After Auto-HSCT.

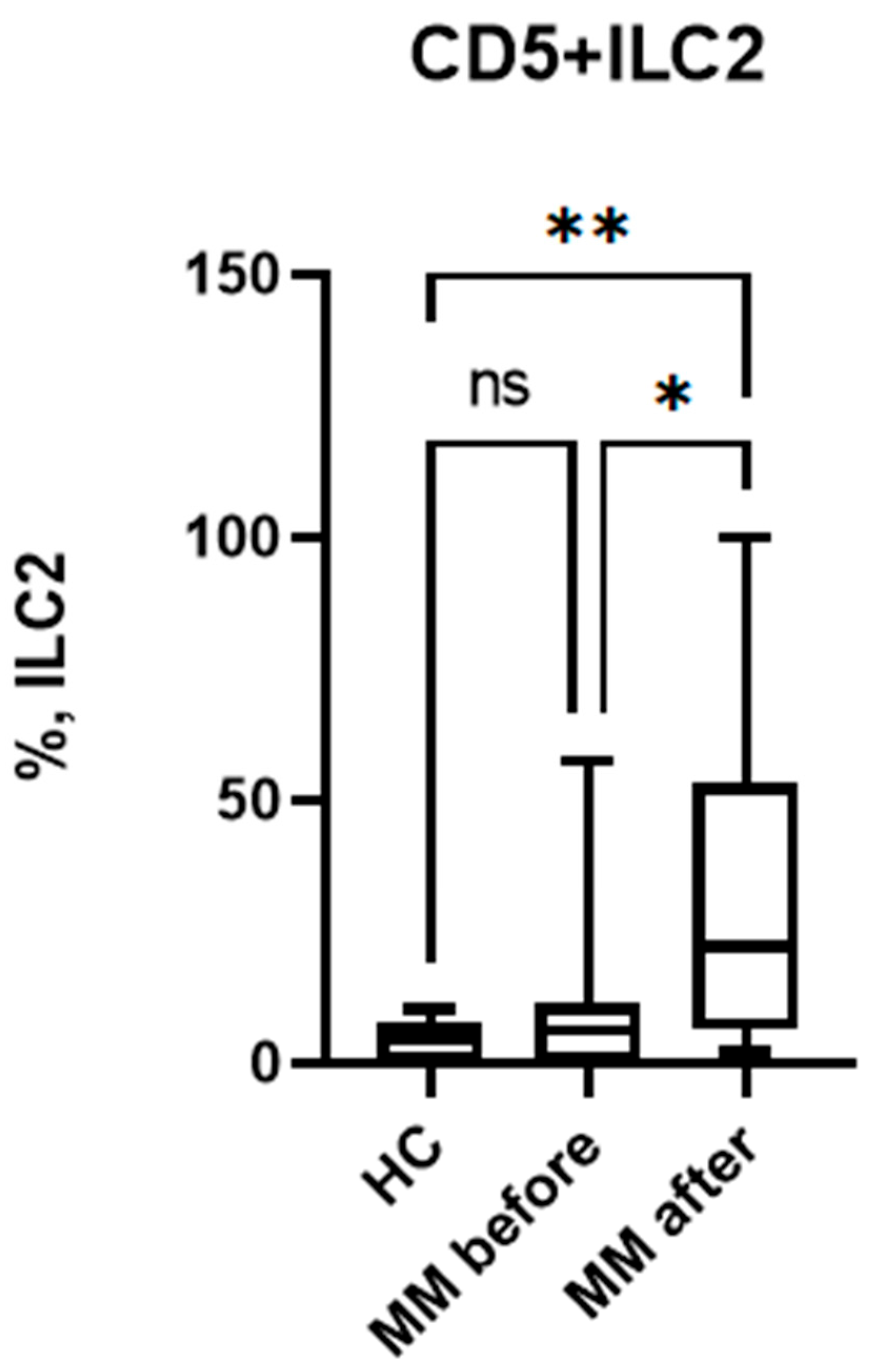

3.2. Relative Number of CD5+ILC2 Before and After Auto-HSCT.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satoh-TakayamaN, VosshenrichCA, Lesjean-Pottier S, Sawa S, Lochner M, Rattis F. et al. Microbial flora drives interleukin 22 production in intestinal NKp46 +cells that provide innate mucosal immune defense. Immunity 2008; 29:958–70 . [CrossRef]

- Luci C, Reynders A, Ivanov II, Cognet C, Chiche L, Chasson L. et al. Influence of the transcription factor RORgammat on the development of NKp46(+) cell populations in gut and skin. Nat Immunol 2009; 10:75–82. [CrossRef]

- Moro K, Yamada T, Tanabe M, Takeuchi T, Ikawa T, Kawamoto H, et al. Innate production of T(H)2 cytokines by adipose tissue-associated c-Kit(+)Sca-1(+) lymphoid cells. Nature 2010; 463:540–4. [CrossRef]

- Neill DR, Wong SH, Bellosi A, Flynn RJ, Daly M, Langford TK, et al. Nuocytes represent a new innate effector leukocyte that mediates type-2 immunity. Nature 2010; 464:1367–70. [CrossRef]

- Ji X., Bie Q., Liu Y., Chen J., Su Z., Wu Y., Ying X., Yang H., Wang S., Xu H. Increased frequencies of nuocytes in peripheral blood from patients with Graves' hyperthyroidism. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014 Oct 15; 7(11):7554-62.

- Liu J, Wu J, Qi F, Zeng S, Xu L, Hu H, Wang D, Liu B. Natural helper cells contribute to pulmonary eosinophilia by producing IL-13 via IL-33/ST2 pathway in a murine model of respiratory syncytial virus infection. Int Immunopharmacol. 2015 Sep; 28(1):337-43. [CrossRef]

- Spits H, Artis D, Colonna M, Diefenbach A, Di Santo JP, Eberl G. et al. Innate lymphoid cells--a proposal for uniform nomenclature. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013 Feb; 13(2):145-9. [CrossRef]

- Mehrani Y, Morovati S, Keivan F, Tajik T, Forouzanpour D, Shojaei S, Bridle BW, Karimi K. Dendritic Cells and Their Crucial Role in Modulating Innate Lymphoid Cells for Treating and Preventing Infectious Diseases. Pathogens. 2025 Aug 8;14(8):794. [CrossRef]

- Jan-Abu SC, Kabil A, McNagny KM. Parallel origins and functions of T cells and ILCs. Clin Exp Immunol. 2023 Jul 5;213(1):76-86. [CrossRef]

- Palumbo A, Bruno B, Boccadoro M, Pileri A. Interferon-gamma in multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995 Jul;18(3-4):215-9. PMID: 8535185. [CrossRef]

- Kellermayer Z, Tahri S, de Jong MME, Papazian N, Fokkema C, Stoetman ECG, Hoogenboezem R, van Beek G, Sanders MA, Boon L, Den Hollander C, Broijl A, Sonneveld P, Cupedo T. Interferon gamma-mediated prevention of tumor progression in a mouse model of multiple myeloma. Hemasphere. 2024 Dec 2;8(12):e70047. [CrossRef]

- Herrmann F, Andreeff M, Gruss HJ, Brach MA, Lübbert M, Mertelsmann R. Interleukin-4 inhibits growth of multiple myelomas by suppressing interleukin-6 expression. Blood. 1991 Oct 15;78(8):2070-4.

- Hernández JM, Gutiérrez NC, Almeida J, García JL, Sánchez MA, Mateo G, Ríos A, San Miguel JF. IL-4 improves the detection of cytogenetic abnormalities in multiple myeloma and increases the proportion of clonally abnormal metaphases. Br J Haematol. 1998 Oct;103(1):163-7. [CrossRef]

- Sawamura M, Murakami H, Tamura J, Matsushima T, Sato S, Naruse T, Tsuchiya J. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin 4 promote the differentiation of myeloma cell precursors in multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 1994 Sep;88(1):17-23. [CrossRef]

- Sugimura R, Wang CY. The Role of Innate Lymphoid Cells in Cancer Development and Immunotherapy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Apr 26;10:803563. [CrossRef]

- Blom B, van Hoeven V, Hazenberg MD. ILCs in hematologic malignancies: Tumor cell killers and tissue healers. Semin Immunol. 2019 Feb;41:101279. [CrossRef]

- Vély F, Barlogis V, Vallentin B, Neven B, Piperoglou C, Ebbo M, Perchet T, Petit M, Yessaad N, Touzot F, Bruneau J, Mahlaoui N, Zucchini N, Farnarier C, Michel G, Moshous D, Blanche S, Dujardin A, Spits H, Distler JH, Ramming A, Picard C, Golub R, Fischer A, Vivier E. Evidence of innate lymphoid cell redundancy in humans. Nat Immunol. 2016 Nov;17(11):1291-1299. [CrossRef]

- Laurie, S.J., Foster, J.P., Bruce, D.W. et al. Type II innate lymphoid cell plasticity contributes to impaired reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat Commun 15, 6000 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Guillerey C, Stannard K, Chen J, Krumeich S, Miles K, Nakamura K, Smith J, Yu Y, Ng S, Harjunpää H, Teng MW, Engwerda C, Belz GT, Smyth MJ. Systemic administration of IL-33 induces a population of circulating KLRG1hi type 2 innate lymphoid cells and inhibits type 1 innate immunity against multiple myeloma. Immunol Cell Biol. 2021 Jan;99(1):65-83. [CrossRef]

- Szudy-Szczyrek A, Ahern S, Kozioł M, Majowicz D, Szczyrek M, Krawczyk J, Hus M. Therapeutic Potential of Innate Lymphoid Cells for Multiple Myeloma Therapy. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Sep 26;13(19):4806. [CrossRef]

- Kini Bailur J, Mehta S, Zhang L, Neparidze N, Parker T, Bar N, et al. Changes in bone marrow innate lymphoid cell subsets in monoclonal gammopathy: target for IMiD therapy. Blood Adv. 2017; 1 (25): 2343–7. [CrossRef]

- Drommi F, Calabr– A, Pezzino G, Vento G, Freni J, Costa G, et al. Multiple Myeloma Cells Shift the Fate of Cytolytic ILC2s Towards TIGIT-Mediated Cell Death. Cancers. 2025; 17 (2): 263. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Pashkina EA, Boeva OS, Borisevich VI, Abbasova VS, Skachkov IP, Lazarev YA, et al. Assessment of the features of innate lymphoid cells in patients with multiple myeloma. Bulletin of RSMU. 2025; (1): 42–6. [CrossRef]

- Hughes CFM, Shah GL, Paul BA. Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma in the age of CAR T cell therapy. Front Oncol. 2024 Mar 27;14:1373548. [CrossRef]

- Rocchi S, Zannetti BA, Marconi G, Lanza F. Multiple Myeloma: The Role of Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation in the Era of Immunotherapy. Cells. 2024 May 16;13(10):853. [CrossRef]

- Alisjahbana A, Gao Y, Sleiers N, Evren E, Brownlie D, von Kries A, Jorns C, Marquardt N, Michaëlsson J, Willinger T. CD5 Surface Expression Marks Intravascular Human Innate Lymphoid Cells That Have a Distinct Ontogeny and Migrate to the Lung. Front Immunol. 2021 Nov 18;12:752104. [CrossRef]

- Voisinne G, Gonzalez de Peredo A, Roncagalli R. CD5, an Undercover Regulator of TCR Signaling. Front Immunol (2018) 9:2900. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02900.

- Burgueno-Bucio E, Mier-Aguilar CA, Soldevila G. The Multiple Faces of CD5. J Leukoc Biol (2019) 105(5):891–904. [CrossRef]

- Simoni Y, Fehlings M, Kløverpris HN, McGovern N, Koo SL, Loh CY, Lim S, Kurioka A, Fergusson JR, Tang CL, Kam MH, Dennis K, Lim TKH, Fui ACY, Hoong CW, Chan JKY, Curotto de Lafaille M, Narayanan S, Baig S, Shabeer M, Toh SES, Tan HKK, Anicete R, Tan EH, Takano A, Klenerman P, Leslie A, Tan DSW, Tan IB, Ginhoux F, Newell EW. Human Innate Lymphoid Cell Subsets Possess Tissue-Type Based Heterogeneity in Phenotype and Frequency. Immunity. 2017 Jan 17;46(1):148-161. Epub 2016 Dec 13. Erratum in: Immunity. 2018 May 15;48(5):1060. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.04.028. [CrossRef]

- Yudanin NA, Schmitz F, Flamar AL, Thome JJC, Tait Wojno E, Moeller JB, Schirmer M, Latorre IJ, Xavier RJ, Farber DL, Monticelli LA, Artis D. Spatial and Temporal Mapping of Human Innate Lymphoid Cells Reveals Elements of Tissue Specificity. Immunity. 2019 Feb 19;50(2):505-519.e4. [CrossRef]

- hen L, Youssef Y, Robinson C, Ernst GF, Carson MY, Young KA, Scoville SD, Zhang X, Harris R, Sekhri P, Mansour AG, Chan WK, Nalin AP, Mao HC, Hughes T, Mace EM, Pan Y, Rustagi N, Chatterjee SS, Gunaratne PH, Behbehani GK, Mundy-Bosse BL, Caligiuri MA, Freud AG. CD56 Expression Marks Human Group 2 Innate Lymphoid Cell Divergence from a Shared NK Cell and Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cell Developmental Pathway. Immunity. 2018 Sep 18;49(3):464-476.e4. [CrossRef]

- Björklund ÅK, Forkel M, Picelli S, Konya V, Theorell J, Friberg D, Sandberg R, Mjösberg J. The heterogeneity of human CD127(+) innate lymphoid cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Immunol. 2016 Apr;17(4):451-60. [CrossRef]

- Nagasawa M, Germar K, Blom B, Spits H. Human CD5+ Innate Lymphoid Cells Are Functionally Immature and Their Development from CD34+ Progenitor Cells Is Regulated by Id2. Front Immunol. 2017 Aug 31;8:1047. [CrossRef]

- Shin SB, McNagny KM. ILC-You in the Thymus: A Fresh Look at Innate Lymphoid Cell Development. Front Immunol. 2021 May 6;12:681110. [CrossRef]

- Cupedo T. ILC2: at home in the thymus. Eur J Immunol. 2018 Sep; 48(9):1441-1444. [CrossRef]

- Alisjahbana A, Gao Y, Sleiers N, Evren E, Brownlie D, von Kries A, Jorns C, Marquardt N, Michaëlsson J, Willinger T. CD5 Surface Expression Marks Intravascular Human Innate Lymphoid Cells That Have a Distinct Ontogeny and Migrate to the Lung. Front Immunol. 2021 Nov 18;12:752104. [CrossRef]

- Annunziato F, Romagnani C, Romagnani S. The 3 major types of innate and adaptive cell-mediated effector immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Mar;135(3):626-35. [CrossRef]

- Feng B, Tang L. A new paradigm for cancer immunotherapy: Orchestrating type 1 and type 2 immunity for curative response. Clin Transl Med. 2025 Jan;15(1):e70154. [CrossRef]

- Wagner M, Nishikawa H, Koyasu S. Reinventing type 2 immunity in cancer. Nature. 2025 Jan;637(8045):296-303. Epub 2025 Jan 8. PMID: 39780006. [CrossRef]

- Kyrstsonis M.-C., Dedou S.G., Bax E.C., Stamate Lou M., Maniatis A. Serum Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Interleukin-4 (IL-4) in Patients with Multiple Myeloma (MM) Br. J. Haematol. 1996;92:420–422. [CrossRef]

- Mikulski D, Robak P, Perdas E, Węgłowska E, Łosiewicz A, Dróżdż I, Jarych D, Misiewicz M, Szemraj J, Fendler W, Robak T. Pretreatment Serum Levels of IL-1 Receptor Antagonist and IL-4 Are Predictors of Overall Survival in Multiple Myeloma Patients Treated with Bortezomib. J Clin Med. 2021 Dec 26;11(1):112. [CrossRef]

- Traynor AE, Schroeder J, Rosa RM, Cheng D, Stefka J, Mujais S, et al. Treatment of severe systemic lupus erythematosus with high-dose chemotherapy and haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation: a phase I study. Lancet. 2000;356:701–707. [CrossRef]

- Leung PSC, Shuai Z, Liu B, Shu SA, Sun L. Stem Cell Therapy in the Treatment of Rheumatic Diseases and Application in the Treatment of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Next-Generation Therapies and Technologies for Immune-Mediated Inflammatory Diseases. 2016 Sep 19:167–98. [CrossRef]

- Fagoaga, Omar & Nehlsen-Cannarella, Sandra & Ratanatharatorn, Voravit & Martinelli, Christine & Lum, Lawrence & Uberti, Joseph. (2007). Sequential Serum Cytokine Levels after Autologous, Related and Unrelated Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation: Reflection of Immune Reactivity and Reconstitution.. Blood. 110. 3885-3885. 10.1182/blood.V110.11.3885.3885.

- Laurie SJ, Foster JP 2nd, Bruce DW, Bommiasamy H, Kolupaev OV, Yazdimamaghani M, Pattenden SG, Chao NJ, Sarantopoulos S, Parker JS, Davis IJ, Serody JS. Type II innate lymphoid cell plasticity contributes to impaired reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat Commun. 2024 Jul 17;15(1):6000. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Wang X, Wang Y, Chang X. What happens to regulatory T cells in multiple myeloma. Cell Death Discov. 2023 Dec 21; 9(1):468. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).