Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

10 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pediatric Tuberculosis

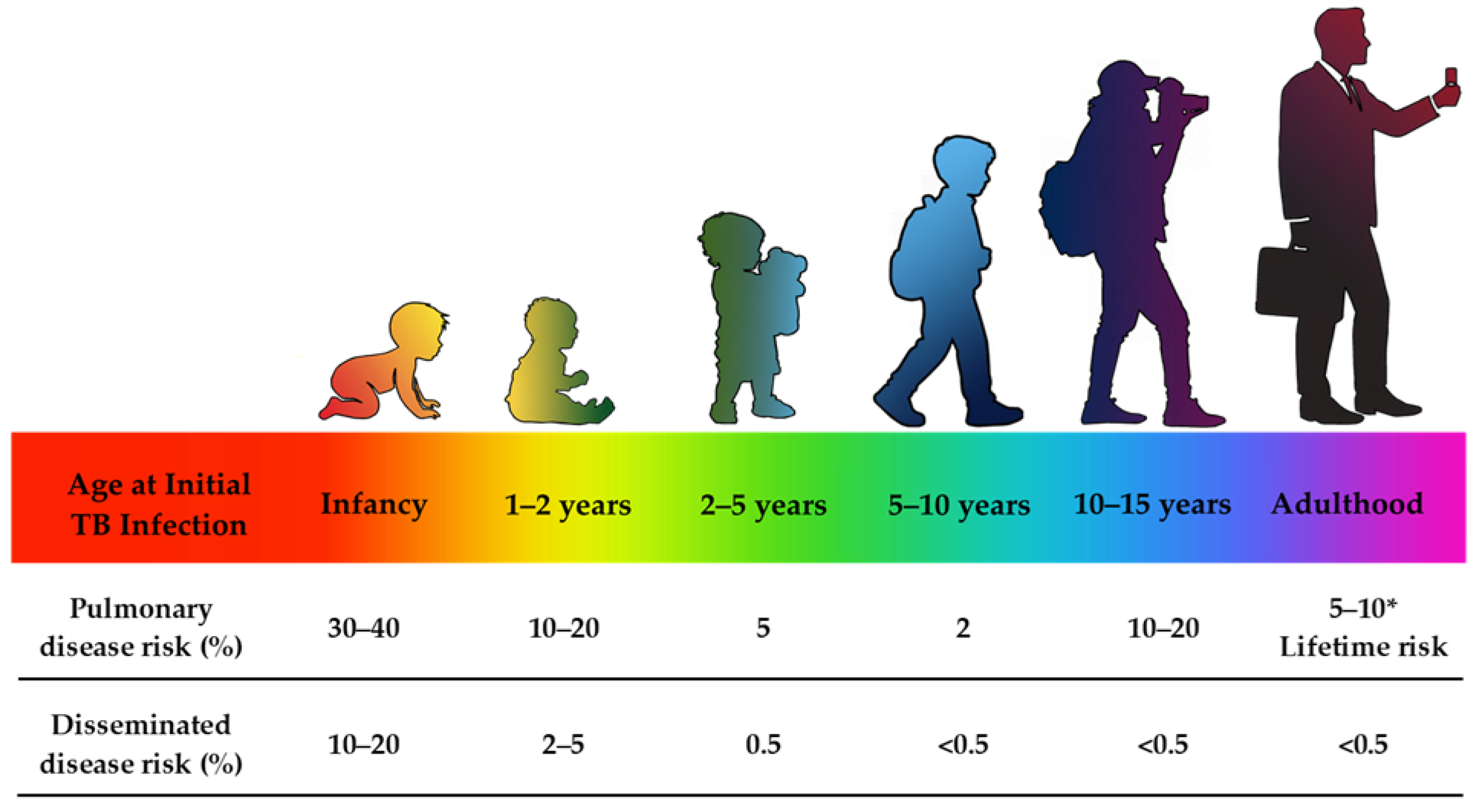

2.1. Pediatric Tuberculosis Transmission and Disease Progression

2.2. Clinical Manifestation of Pediatric Tuberculosis

2.2.1. Indications of Pediatric Extrapulmonary Tuberculosis Infection

3. Therapeutic Management of Pediatric Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis

3.1. Current Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Pediatric Tuberculosis

3.2. General Classification of First-line Antitubercular Drugs

4. Rifampicin: Characteristics and Challenges

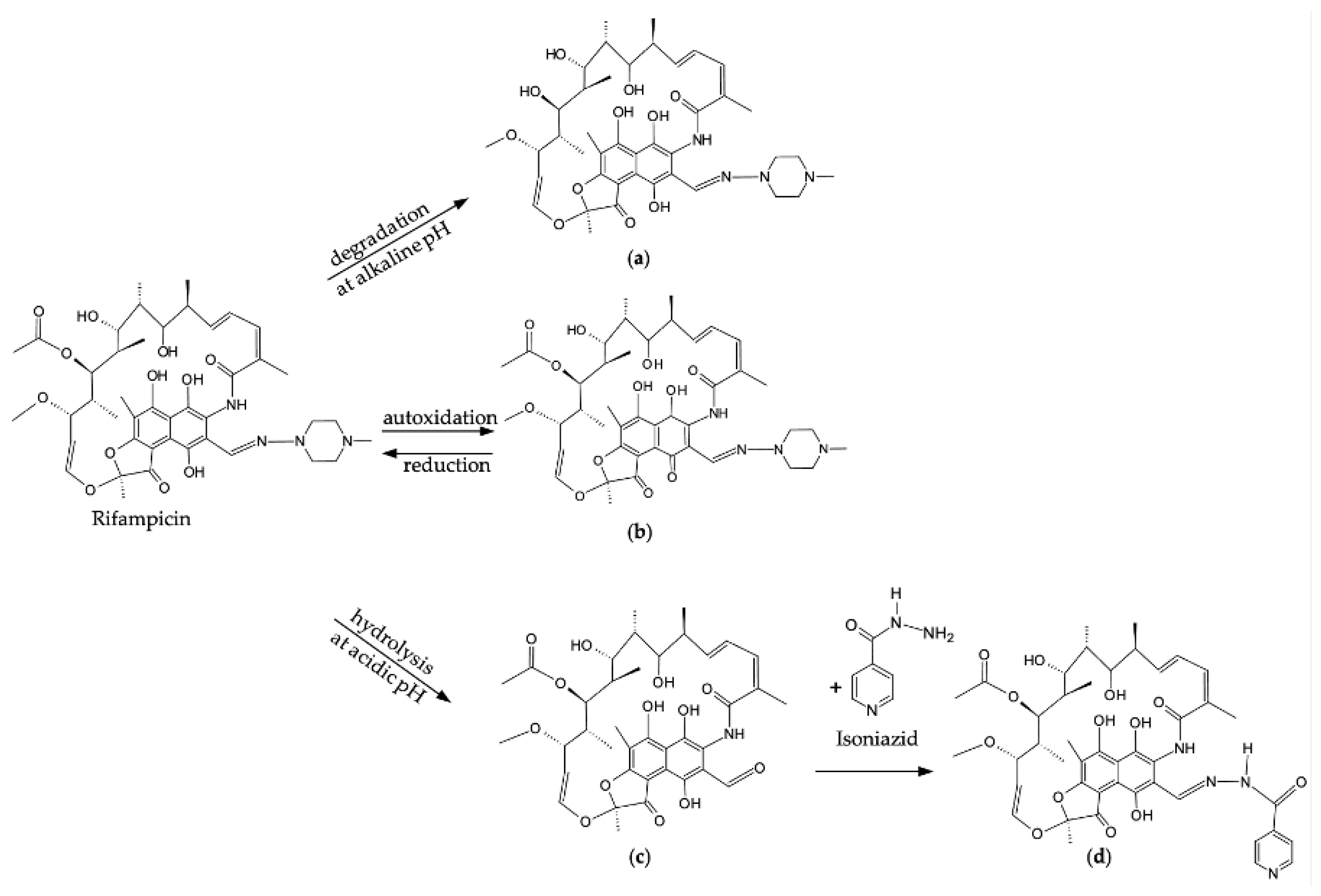

4.1. Physicochemical Properties and Rifampicin Instabilities

4.2. Available Child-Friendly Rifampicin Dosage Forms

4.3. General Requirements and Considerations for Child-Friendly Dosage Forms

5. Can the Therapeutic Efficacy of Rifampicin Liquid Formulations be Improved?

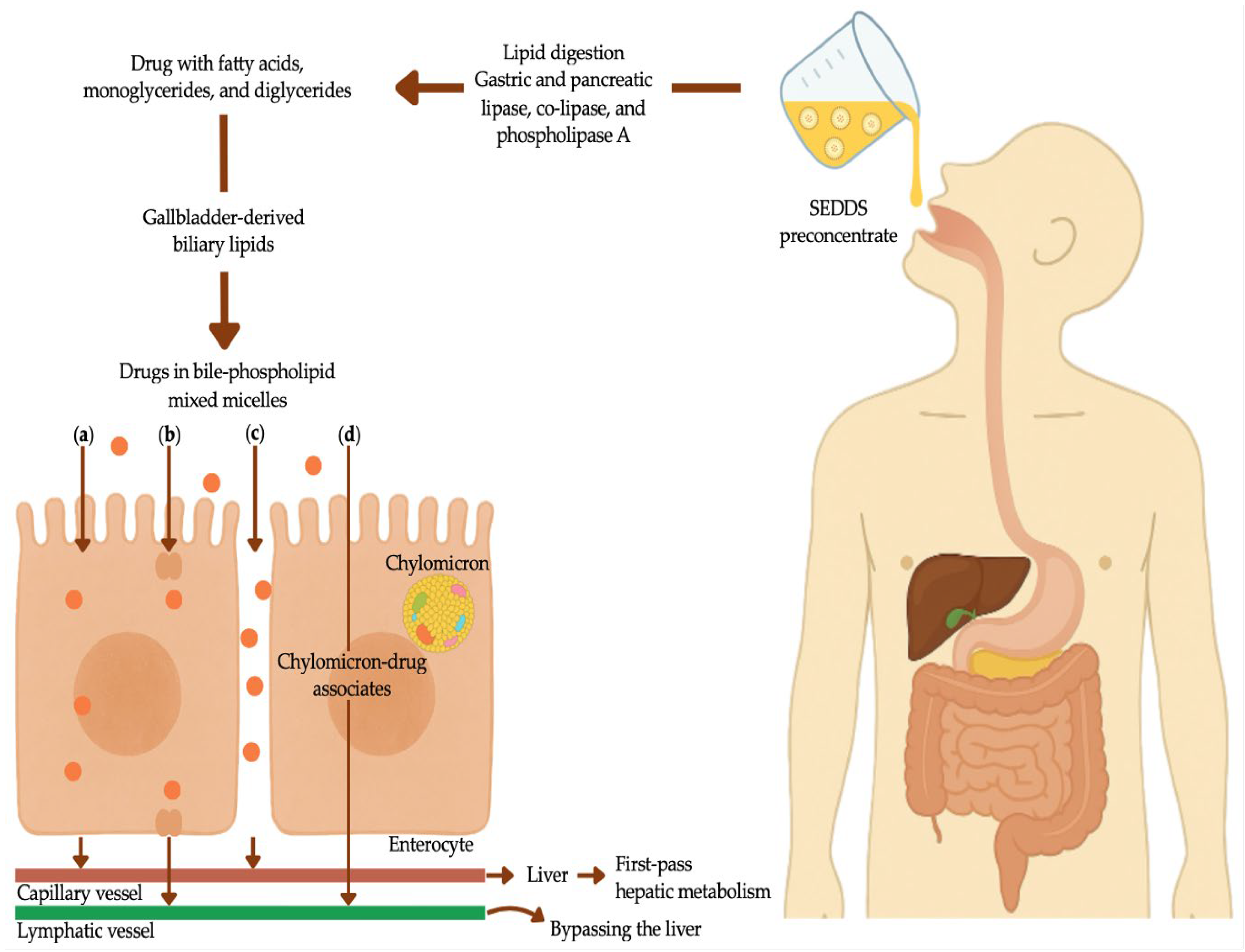

5.1. Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems

5.1.1. Composition of Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems

5.2. Optimizing Pediatric Oral Bioavailability of Lipophilic Drugs

6. Liquid Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems as a Novel Approach to Enhance Oral Rifampicin Delivery

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zumla, A.; Sahu, S.; Ditiu, L.; Singh, U.; Park, Y.-J.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Osei-Wusu, S.; Asogun, D.; Nyasulu, P.; Tembo, J.; et al. Inequities Underlie the Alarming Resurgence of Tuberculosis as the World's Top Cause of Death From an Infectious Disease - Breaking the Silence and Addressing the Underlying Root Causes. IJID Regions 2025, 14, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulumbe, B.H.; Abdulrahim, A.; Danlami, M.B. The United Nations' Ambitious Roadmap Against Tuberculosis: Opportunities, Challenges and the Imperative of Equity. Future Science OA 2024, 10, 2418787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, A.; Bhargava, M.; Pai, M. Tuberculosis: A Biosocial Problem That Requires Biosocial Solutions. Lancet 2024, 403, 2467–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tristram, D.; Tobin, E.H. Tuberculosis in Children. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK610681/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis Resurges as Top Infectious Disease Killer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/29-10-2024-tuberculosis-resurges-as-top-infectious-disease-killer (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Chakaya, J.; Khan, M.; Ntoumi, F.; Aklillu, E.; Fatima, R.; Mwaba, P.; Kapata, N.; Mfinanga, S.; Hasnain, S.E.; Katoto, P.D.M.C.; et al. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020 - Reflections on the Global TB Burden, Treatment and Prevention Efforts. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 113, S7–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grange, J.M.; Zumla, A. The Global Emergency of Tuberculosis: What Is the Cause? Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 2002, 122, 78–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2023; Geneva, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lönnroth, K.; Migliori, G.B.; Abubakar, I.; D'Ambrosio, L.; de Vries, G.; Diel, R.; Douglas, P.; Falzon, D.; Gaudreau, M.-A.; Goletti, D.; et al. Towards Tuberculosis Elimination: An Action Framework for Low-Incidence Countries. European Respiratory Journal 2015, 45, 928–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tobin, E.H.; Tristram, D. Tuberculosis Overview. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441916/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Frutos, D.M.; Hidalgo, I.M.; Negre, J.S. Tuberculosis Treatment in Paediatrics: Liquid Pharmaceutical Forms. Rev Enf Emerg 2020, 19, 169–176. [Google Scholar]

- Borrell, S.; Trauner, A.; Brites, D.; Rigouts, L.; Loiseau, C.; Coscolla, M.; Niemann, S.; De Jong, B.; Yeboah-Manu, D.; Kato-Maeda, M.; et al. Reference Set of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Clinical Strains: A Tool for Research and Product Development. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumla, A.; Nahid, P.; Cole, S.T. Advances in the Development of New Tuberculosis Drugs and Treatment Regimens. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2013, 12, 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvvari, T.K. The Persistent Threat of Tuberculosis - Why Ending TB Remains Elusive? Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases 2025, 38, 100510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mane, S.S.; Shrotriya, P. Current Epidemiology of Pediatric Tuberculosis. Indian Journal of Pediatrics 2024, 91, 711–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphalle, L.N.F.; Michniak-Kohn, B.B.; Ogunrombi, M.O.; Adeleke, O.A. Pediatric Tuberculosis Management: A Global Challenge or Breakthrough? Children 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, J.; Abo, Y.-N.; Triasih, R.; Singh, V.; Pukai, G.; Masta, P.; Tsogt, B.; Luu, B.K.; Felisia, F.; Pank, N.; et al. Emerging Evidence to Reduce the Burden of Tuberculosis in Children and Young People. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2025, 155, N.PAG–N.PAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Getahun, H.; Matteelli, A.; Chaisson, R.E.; Raviglione, M. Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. New England Journal of Medicine 2015, 372, 2127–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comstock, G.W.; Livesay, V.T.; Woolpert, S.F. The Prognosis of a Positive Tuberculin Reaction in Childhood and Adolescence. American Journal of Epidemiology 1974, 99, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Zalm, M.M.; Jongen, V.W.; Swanepoel, R.; Zimri, K.; Allwood, B.; Palmer, M.; Dunbar, R.; Goussard, P.; Schaaf, H.S.; Hesseling, A.C.; et al. Impaired Lung Function in Adolescents with Pulmonary Tuberculosis During Treatment and Following Treatment Completion. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, L.; Gray, D.M.; Botha, M.; Nel, M.; Chaya, S.; Jacobs, C.; Workman, L.; Nicol, M.P.; Zar, H.J. The Long-Term Impact of Early-Life Tuberculosis Disease on Child Health: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2023, 207, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkereuwem, E.; Agbla, S.; Sallahdeen, A.; Owolabi, O.; Sillah, A.K.; Genekah, M.; Tunkara, A.; Kandeh, S.; Jawara, M.; Saidy, L.; et al. Reduced Lung Function and Health-Related Quality of Life After Treatment for Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Gambian Children: A Cross-Sectional Comparative Study. Thorax 2022, 78, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkereuwem, E.; Ageiwaa Owusu, S.; Fabian Edem, V.; Kampmann, B.; Togun, T. Post-Tuberculosis Lung Disease in Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review of Definitions, Measuring Tools, and Research Gaps. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2025, 53, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomberg, B.; Spinaci, S. The Rationale for Recommending Fixed-Dose Combination Tablets for Treatment of Tuberculosis. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2001, 79, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Seneadza, N.A.H.; Antwi, S.; Yang, H.; Enimil, A.; Dompreh, A.; Wiesner, L.; Peloquin, C.A.; Lartey, M.; Lauzardo, M.; Kwara, A. Effect of Malnutrition on the Pharmacokinetics of Anti-TB drugs in Ghanaian Children. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2021, 25, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singla, R.; Mallick, M.; Mrigpuri, P.; Singla, N.; Gupta, A. Sequelae of Pulmonary Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis at the Completion of Treatment. Lung India 2018, 35, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, S.; Heimo, L.; Carter, D.; Closa, M.R.; Vanleeuw, L.; Chenciner, L.; Wambi, P.; Sidney-Annerstedt, K.; Egere, U.; Verkuijl, S.; et al. The Socioeconomic Impact of Tuberculosis on Children and Adolescents: A Scoping Review and Conceptual Framework. BMC Public Health 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buya, A.B.; Witika, B.A.; Bapolisi, A.M.; Mwila, C.; Mukubwa, G.K.; Memvanga, P.B.; Makoni, P.A.; Nkanga, C.I. Application of Lipid-Based Nanocarriers for Antitubercular Drug Delivery: A Review. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .

- Sadaphal, P.; Chakraborty, K.; Jassim-AlMossawi, H.; Pillay, Y.; Roscigno, G.; Kaul, A.; Kak, N.; Matji, R.; Mvusi, L.; DeStefano, A. Rifampicin Bioavailability in Fixed-Dose Combinations for Tuberculosis Treatment: Evidence and Policy Actions. Journal of Lung Health and Diseases 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angiolini, L.; Agnes, M.; Cohen, B.; Yannakopoulou, K.; Douhal, A. Formation, Characterization and pH Dependence of Rifampicin: Heptakis(2,6-di-O-methyl)-β-Cyclodextrin Complexes. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2017, 531, 668–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mereškevičienė, R.; Danila, E. The Adverse Effects of Tuberculosis Treatment: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Medicina 2025, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, A. Advancements in Tuberculosis Treatment: From Epidemiology to Innovative Therapies. International Journal of Science and Research (IJSR) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshney, K.; Patel, H.; Kamal, S. Trends in Tuberculosis Mortality Across India: Improvements Despite the COVID-19 Pandemic. Cureus 2023, 15, e38313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemu, A.; Bitew, Z.W.; Diriba, G.; Gumi, B. Risk Factors Associated with Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 2022, 69, 2559–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wademan, D.T.; Busakwe, L.; Nicholson, T.J.; van der Zalm, M.; Palmer, M.; Workman, J.; Turkova, A.; Crook, A.M.; Thomason, M.J.; Gibb, D.M.; et al. Acceptability of a First-Line Anti-Tuberculosis Formulation for Children: Qualitative Data from the SHINE Trial. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2019, 23, 1263–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

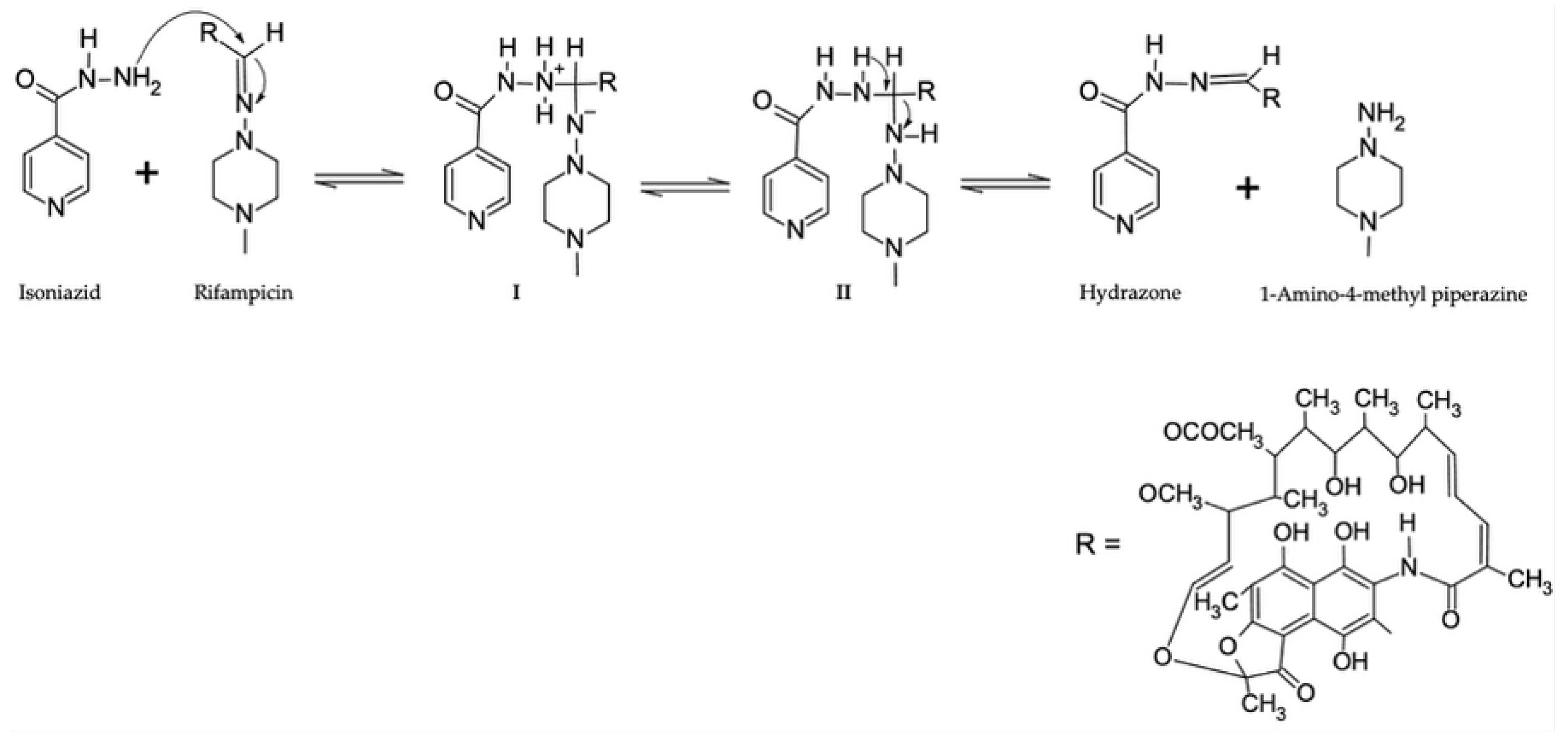

- Bhutani, H.; Singh, S.; Jindal, K.C.; Chakraborti, A.K. Mechanistic Explanation to the Catalysis by Pyrazinamide and Ethambutol of Reaction Between Rifampicin and Isoniazid in Anti-TB FDCs. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2005, 39, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Deventer, M.; Haynes, R.K.; Brits, M.; Viljoen, J.M. Formulation of Topical Drug Delivery Systems Containing a Fixed-Dose Isoniazid–Rifampicin Combination Using the Self-Emulsification Mechanism. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, S.; Sarwar, M.R. Potential Disadvantages Associated with Treatment of Active Tuberculosis Using Fixed-Dose Combination: A Review of Literature. Journal of Basic and Clinical Pharmacy 2017, 8, S131–136. [Google Scholar]

- Mariappan, T.T.; Singh, S. Regional Gastrointestinal Permeability of Rifampicin and Isoniazid (Alone and Their Combination) in the Rat. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2003, 7, 797–803. [Google Scholar]

- Denti, P.; Wasmann, R.E.; van Rie, A.; Winckler, J.; Bekker, A.; Rabie, H.; Hesseling, A.C.; van der Laan, L.E.; Gonzalez-Martinez, C.; Zar, H.J.; et al. Optimizing Dosing and Fixed-Dose Combinations of Rifampicin, Isoniazid, and Pyrazinamide in Pediatric Patients with Tuberculosis: A Prospective Population Pharmacokinetic Study. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 75, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsiligiannis, A.; Sfouni, M.; Nalda-Molina, R.; Dokoumetzidis, A. Optimization of a Paediatric Fixed Dose Combination Mini-tablet and Dosing Regimen for the First Line Treatment of Tuberculosis. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2019, 138, 105016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.; Behr, M.A.; Dowdy, D.; Dheda, K.; Divangahi, M.; Boehme, C.C.; Ginsberg, A.; Swaminathan, S.; Spigelman, M.; Getahun, H.; et al. Tuberculosis. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matawo, N.; Adeleke, O.A.; Wesley-Smith, J. Optimal Design, Characterization and Preliminary Safety Evaluation of an Edible Orodispersible Formulation for Pediatric Tuberculosis Pharmacotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 5714–5714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeleke, O.A.; Hayeshi, R.K.; Davids, H. Development and Evaluation of a Reconstitutable Dry Suspension Containing Isoniazid for Flexible Pediatric Dosing. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnik, A.; Seremeta, K.P.; Imperiale, J.C.; Chiappetta, D.A. Novel Formulation and Drug Delivery Strategies for the Treatment of Pediatric Poverty-Related Diseases. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2012, 9, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, S.R.; Adams, L.V.; Spielberg, S.P.; Campbell, B. Pediatric Therapeutics and Medicine Administration in Resource-Poor Settings: A Review of Barriers and an Agenda for Interdisciplinary Approaches to Improving Outcomes. Social Science and Medicine 2009, 69, 1681–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahata, M.C. Safety of “Inert" Additives or Excipients in Paediatric Medicines. Archives of Disease in Childhood Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2009, 94, F392–F393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- South African Health Products Regulatory Authority. Registered Health Products Database. Available online: https://medapps.sahpra.org.za:6006 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Salim, S.; Murshid, M.; Gazzali, A. Stability of Extemporaneous Rifampicin Prepared with X-temp® Oral Suspension System. Journal of Pharmacy 2021, 1, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riet-Nales, D.A.; Schobben, A.F.A.M.; Vromans, H.; Egberts, T.C.G.; Rademaker, C.M.A. Safe and Effective Pharmacotherapy in Infants and Preschool Children: Importance of Formulation Aspects. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2016, 101, 662–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Pharmaceutical Development of Medicines for Paediatric Use. Available online: https://www.tga.gov.au/sites/default/files/2024-07/Guidelineonpharmaceuticaldevelopmentofmedicinesforpaediatric%20use%20.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Mahtab, S.; Blau, D.M.; Madewell, Z.J.; Ogbuanu, I.; Ojulong, J.; Lako, S.; Legesse, H.; Bangura, J.S.; Bassat, Q.; Mandomando, I.; et al. Post-Mortem Investigation of Deaths Due to Pneumonia in Children Aged 1-59 Months in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia From 2016 to 2022: An Observational Study. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health 2024, 8, 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, T.A. Tuberculosis in Children. Pediatric Clinics of North America 2017, 64, 893–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, D.O.; Jimenez, A.L.L.; Diniz, L.M.O.; Cardoso, C.A. Missed Opportunities in the Prevention and Diagnosis of Pediatric Tuberculosis: A Scoping Review. Jornal de Pediatria 2024, 100, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plata-Casas, L.; González-Támara, L.; Cala-Vitery, F. Tuberculosis Mortality in Children under Fifteen Years of Age: Epidemiological Situation in Colombia, 2010-2018. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2022, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S.; Chakraborty, S. A Comprehensive Review of the Diagnostics for Pediatric Tuberculosis Based on Assay Time, Ease of Operation, and Performance. Microorganisms 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, P.J.; Yuen, C.M.; Sismanidis, C.; Seddon, J.A.; Jenkins, H.E. The Global Burden of Tuberculosis Mortality in Children: A Mathematical Modelling Study. Lancet Global Health 2017, 5, e898–e906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelosi, U.; Pintus, R.; Savasta, S.; Fanos, V. Pulmonary Tuberculosis in Children: A Forgotten Disease? Microorganisms 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennelly, K.P.; Martyny, J.W.; Fulton, K.E.; Orme, I.M.; Cave, D.M.; Heifets, L.B. Cough-Generated Aerosols of Mycobacterium Tuberculosis: A New Method to Study Infectiousness. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2004, 169, 604–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Driessche, K.; Persson, A.; Marais, B.J.; Fink, P.J.; Urdahl, K.B. Immune Vulnerability of Infants to Tuberculosis. Clinical and Developmental Immunology 2013, 2013, 781320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, D.P.; Schaaf, H.S.; Nuttall, J.; Marais, B.J.; Brink, A. Childhood Tuberculosis Guidelines of the Southern African Society for Paediatric Infectious Diseases. In Proceedings of the Southern African Journal of Epidemiology and Infection, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2009/01/01/2009, 2009; pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Marais, B.J.; Gie, R.P.; Schaaf, H.S.; Hesseling, A.C.; Obihara, C.C.; Nelson, L.J.; Enarson, D.A.; Donald, P.R.; Beyers, N. The Clinical Epidemiology of Childhood Pulmonary Tuberculosis: A Critical Review of Literature from the Pre-Chemotherapy Era. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2004, 8, 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, S.M.; Brent, A.J.; Anderson, S.; Whittaker, E.; Kampmann, B. Paediatric Tuberculosis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2008, 8, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Reflection Paper: Formulations of Choice for the Paediatric Population. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientific-guideline/reflection-paper-formulations-choice-paediatric-population_en.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Lamb, G.S.; Starke, J.R. Tuberculosis in Infants and Children. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laycock, K.M.; Enane, L.A.; Steenhoff, A.P. Tuberculosis in Adolescents and Young Adults: Emerging Data on TB Transmission and Prevention among Vulnerable Young People. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2021, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolt, D.; Starke, J.R. Tuberculosis Infection in Children and Adolescents: Testing and Treatment. Pediatrics 2021, 148, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddalingaiah, N.; Chawla, K.; Nagaraja, S.B.; Hazra, D. Risk Factors for the Development of Tuberculosis among the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. European Journal of Pediatrics 2023, 182, 3007–3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancella, L.; Vecchio, A.L.; Chiappini, E.; Tadolini, M.; Cirillo, D.; Tortoli, E.; de Martino, M.; Guarino, A.; Principi, N.; Villani, A.; et al. How to Manage Children Who Have Come into Contact with Patients Affected by Tuberculosis. Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases 2015, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Barrientos, H.d.; Centeno-Luque, G.; Untiveros-Tello, A.; Simms, B.; Lecca, L.; Nelson, A.K.; Lastimoso, C.; Shin, S. Clinical Presentation of Children with Pulmonary Tuberculosis: 25 Years of Experience in Lima, Peru. International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2014, 18, 1066–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Roadmap for Childhood Tuberculosis: Towards Zero Deaths; Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, S.M.; Oliwa, J.N. Diagnosis and Management of Tuberculosis in Children and Adolescents: A Desk Guide for Primary Health Care Workers; Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, S.; Tagliabue, C.; Bosis, S. Tuberculosis in Children. Mediterranean Journal of Hematology and Infectious Diseases 2013, 5, e2013064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartoris, G.; Seddon, J.A.; Rabie, H.; Nel, E.D.; Schaaf, H.S. Abdominal Tuberculosis in Children: Challenges, Uncertainty, and Confusion. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2020, 9, 218–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsa, F.; Essaddam, L.; Fitouri, Z.; Brini, I.; Douira, W.; Ben Becher, S.; Boussetta, K.; Bousnina, S. Abdominal Tuberculosis in Children. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition 2010, 50, 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, A. Paediatric Osteoarticular Tuberculosis: A Review. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 2020, 11, 202–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.K.; Somvanshi, D.S. Spinal Tuberculosis: A Review. The Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 2011, 34, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, H.E.L.; Peh, W.C.G. Skeletal Tuberculosis in Children. Pediatric Radiology 2004, 34, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattamapaspong, N.; Muttarak, M.; Sivasomboon, C. Tuberculosis Arthritis and Tenosynovitis. Seminars in Musculoskeletal Radiology 2011, 15, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imazio, M.; Gaita, F.; LeWinter, M. Evaluation and Treatment of Pericarditis: A Systematic Review. JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 2015, 314, 1498–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Lapausa, M.; Menéndez-Saldaña, A.; Noguerado-Asensio, A. [Extrapulmonary tuberculosis]. Revista Espanola De Sanidad Penitenciaria 2015, 17, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K.; Mohan, A. Miliary Tuberculosis. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, S.M. Treatment of Paediatric TB: Revised WHO Guidelines. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews 2011, 12, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Consolidated Guidelines on Tuberculosis Module 5: Management of Tuberculosis in Children and Adolescents. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/352522/9789240046764-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Nahid, P.; Mase, S.R.; Migliori, G.B.; Sotgiu, G.; Bothamley, G.H.; Brozek, J.L.; Cattamanchi, A.; Cegielski, J.P.; Chen, L.; Daley, C.L.; et al. Treatment of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. An Official ATS/CDC/ERS/IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2019, 200, e93–e142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaaf, H.S.; Garcia-Prats, A.J.; Donald, P.R. Antituberculosis Drugs in Children. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2015, 98, 252–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsayed, S.S.R.; Gunosewoyo, H. Tuberculosis: Pathogenesis, Current Treatment Regimens and New Drug Targets. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 5202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tuberculosis in Children. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/tb/about/children.html (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Bhanu, M.L.S.; Manasa P Kumari; Begum, T.M. Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs and Mechanisms of Action: Review. International Journal of Infectious Diseases and Research 2023, 4, 1-7.

- Chauhan, A.; Kumar, M.; Kumar, A.; Kanchan, K. Comprehensive Review on Mechanism of Action, Resistance and Evolution of Antimycobacterial Drugs. Life Sciences 2021, 274, N.PAG-N.PAG. [CrossRef]

- Omoteso, O.A.; Fadaka, A.O.; Walker, R.B.; Khamanga, S.M. Innovative Strategies for Combating Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Advances in Drug Delivery Systems and Treatment. Microorganisms 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Britton, P.; Perez-Velez, C.M.; Marais, B.J. Diagnosis, Treatment and Prevention of Tuberculosis in Children. New South Wales Public Health Bulletin 2013, 24, 15-21. [CrossRef]

- Schellack, N.; Yotsombut, K.; Sabet, A.; Nafach, J.; Hiew, F.L.; Kulkantrakorn, K. Expert Consensus on Vitamin B6 Therapeutic Use for Patients: Guidance on Safe Dosage, Duration and Clinical Management. Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety 2025, 17, 97-108. [CrossRef]

- Tostmann, A.; Boeree, M.J.; Aarnoutse, R.E.; de Lange, W.C.M.; van der Ven, A.J.A.M.; Dekhuijzen, R. Antituberculosis Drug-Induced Hepatotoxicity: Concise Up-To-Date Review. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2008, 23, 192-202. [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.A.; Leon, G.; Miller, N.M.; Reyes, S.P.; Thantrong, C.H.; Thokkadam, A.M.; Lemma, A.S.; Sivaloganathan, D.M.; Wan, X.; Brynildsen, M.P. Rifamycin Antibiotics and the Mechanisms of Their Failure. The Journal of Antibiotics 2021, 74, 786-798. [CrossRef]

- Brucoli, F.; D McHugh, T. Rifamycins: Do Not Throw the Baby Out With the Bathwater. Is Rifampicin Still an Effective Anti-Tuberculosis Drug? Future Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 13, 2129-2131. [CrossRef]

- Hoagland, D.; Zhao, Y.; Lee, R.E. Advances in Drug Discovery and Development for Pediatric Tuberculosis. Mini Rev Med Chem 2016, 16, 481-497. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Savic, R.M.; Boeree, M.J.; Peloquin, C.A.; Weiner, M.; Heinrich, N.; Bliven-Sizemore, E.; Phillips, P.P.J.; Hoelscher, M.; Whitworth, W.; et al. Optimising Pyrazinamide for The Treatment of Tuberculosis. European Respiratory Journal 2021, 58. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, L.; Lihua, H.; Min, Y.; Zheng-Guo, H. Molecular Mechanism of The Synergistic Activity of Ethambutol and Isoniazid Against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293, 16741-16750. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Musuka, S.; Sherman, C.; Meek, C.; Leff, R.; Gumbo, T. Efflux-Pump-Derived Multiple Drug Resistance to Ethambutol Monotherapy in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of Ethambutol. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010, 201, 1225-1231. [CrossRef]

- Jnawali, H.N.; Ryoo, S. First– and Second–Line Drugs and Drug Resistance. In Tuberculosis - Current Issues in Diagnosis and Management; InTech: 2013.

- Castro, N.D.; Mechaï, F.; Bachelet, D.; Canestri, A.; Joly, V.; Vandenhende, M.; Boutoille, D.; Kerjouan, M.; Veziris, N.; Molina, J.M.; et al. Treatment With a Three-Drug Regimen for Pulmonary Tuberculosis Based on Rapid Molecular Detection of Isoniazid Resistance: A Noninferiority Randomized Trial (FAST-TB). Open Forum Infectious Diseases 2022, 9, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Levy, M.; Rigaudière, F.; de Lauzanne, A.; Koehl, B.; Melki, I.; Lorrot, M.; Faye, A. Ethambutol-related Impaired Visual Function in Childrens Less than 5 Years of Age Treated for a Mycobacterial Infection. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2015, 34, 346-350. [CrossRef]

- Noor, H.; David, I.G.; Jinga, M.L.; Popa, D.E.; Buleandra, M.; Iorgulescu, E.E.; Ciobanu, A.M. State of the Art on Developments of (Bio)Sensors and Analytical Methods for Rifamycin Antibiotics Determination. Sensors 2023, 23, 976. [CrossRef]

- De Pinho Pessoa Nogueira, L.; De Oliveira, Y.S.; De C. Fonseca, J.; Costa, W.S.; Raffin, F.N.; Ellena, J.; Ayala, A.P. Crystalline Structure of the Marketed Form of Rifampicin: A Case of Conformational and Charge Transfer Polymorphism. Journal of Molecular Structure 2018, 1155, 260-266. [CrossRef]

- Zaborniak, I.; Macior, A.; Chmielarz, P. Stimuli-Responsive Rifampicin-Based Macromolecules. Materials (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- British Pharmacopoeia. Rifampicin. Available online: https://www.pharmacopoeia.com/bp-2025/monographs/rifampicin.html?date=2025-04-01&text=Rifampicin (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Hussain, A.; Shakeel, F.; Singh, S.K.; Alsarra, I.A.; Faruk, A.; Alanazi, F.K.; Peter Christoper, G.V. Solidified SNEDDS for the Oral Delivery of Rifampicin: Evaluation, Proof of Concept, In Vivo Kinetics, and In Silico GastroPlusTM Simulation. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2019, 566, 203-217. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.H.; Taha, D.N. Determination of Rifampicin in Pure form and Pharmaceutical Preparations by Using Merging Zone-Continuous Flow Injection Analysis. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Quality Assurance 2019, 10, 303–310. [CrossRef]

- Karaźniewicz-Łada, M. A Review on Recent Advances in the Stability Study of Anti-Mycobacterial Drugs. Polimery W Medycynie 2024, 54, 135-142. [CrossRef]

- Henwood, S.Q.; Liebenberg, W.; Tiedt, L.R.; Lötter, A.P.; de Villiers, M.M. Characterization of the Solubility and Dissolution Properties of Several New Rifampicin Polymorphs, Solvates, and Hydrates. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy 2001, 27, 1017-1030. [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Ashokraj, Y.; Bharatam, P.V.; Pillai, O.; Panchagnula, R. Solid-State Characterization of Rifampicin Samples and Its Biopharmaceutic Relevance. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2004, 22, 127-144. [CrossRef]

- Arca, H.Ç.; Mosquera-Giraldo, L.I.; Pereira, J.M.; Sriranganathan, N.; Taylor, L.S.; Edgar, K.J. Rifampin Stability and Solution Concentration Enhancement Through Amorphous Solid Dispersion in Cellulose ω-Carboxyalkanoate Matrices. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2018, 107, 127-138. [CrossRef]

- Piccaro, G.; Poce, G.; Biava, M.; Giannoni, F.; Fattorini, L. Activity of Lipophilic and Hydrophilic Drugs Against Dormant and Replicating Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Journal of Antibiotics 2015, 68, 711-714.

- O’Neil, M.J. The Merck Index - An Encyclopedia of Chemicals, Drugs, and Biologicals. 2001, 1474.

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Kassem, A.A.; Attia, I.A.; Mohamed, S.I. Studies on Some Factors Affecting the Stability of Rifampicin in Solution. Bulletin of Pharmaceutical Sciences Assiut University 1979, 2, 11-25. [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Deng, P.; Yang, L.; Tan, Q.; Liu, J.; Yang, M.; Zhang, J. Molecular Encapsulation of Rifampicin as an Inclusion Complex of Hydroxypropyl-β-Cyclodextrin: Design; Characterization and In Vitro Dissolution. Colloids and Surfaces B: Biointerfaces 2013, 103, 580-585. [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.; Reis, T.V.d.S.; Silva, L.C.C.d.; Storpírtis, S.; Mercuri, L.P.; Matos, J.d.R. Thermal Behavior and Decomposition Kinetics of Rifampicin Polymorphs Under Isothermal and Non-Isothermal Conditions. Brazilian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2010, 46, 343-351.

- Mariappan, T.T.; Singh, S. Positioning of Rifampicin in the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS). Clinical Research and Regulatory Affairs 2006, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vander Schaaf, M.; Luth, K.; Townsend, D.M.; Chessman, K.H.; Mills, C.M.; Garner, S.S.; Peterson, Y.K. CYP3A4 Drug Metabolism Considerations in Pediatric Pharmacotherapy. Medicinal Chemistry Research 2024, 33, 2221–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloor Suresh, A.; Rosani, A.; Wadhwa, R. Rifampin. Available online: https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=ac1553a5-ec8b-30e2-9a43-8cc3ed3110f5 (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Kearns, G.L.; Abdel-Rahman, S.M.; Alander, S.W.; Blowey, D.L.; Leeder, J.S.; Kauffman, R.E. Developmental Pharmacology – Drug Disposition, Action, and Therapy in Infants and Children. New England Journal of Medicine 2003, 349, 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.B.; Cotten, C.M.; Hudak, M.L.; Sullivan, J.E.; Poindexter, B.B.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M.; Boakye-Agyeman, F.; Lewandowski, A.; Anand, R.; Benjamin, D.K., Jr.; et al. Rifampin Pharmacokinetics and Safety in Preterm and Term Infants. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen-Wolkowiez, M.; Benjamin, D.K., Jr.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Wade, K.C.; Alexander, B.D.; Worley, G.; Goldstein, R.F.; Smith, P.B. Mortality and Neurodevelopmental Outcome after Staphylococcus Aureus Bacteremia in Infants. The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2007, 26, 1159–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, J.; Stolk, L.M.L.; Degraeuwe, P.L.J.; van Tiel, F.H.; Neef, C.; Zimmermann, L.J.I. Pharmacokinetics of Intravenous Rifampicin (Rifampin) in Neonates. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 2006, 28, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nahata, M.C.; Fan-Havard, P.; Barson, W.J.; Bartkowski, H.M.; Kosnik, E.J. Pharmacokinetics, Cerebrospinal Fluid Concentration, and Safety of Intravenous Rifampin in Pediatric Patients Undergoing Shunt Placements. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1990, 38, 515–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassr, N.; Huennemeyer, A.; Herzog, R.; von Richter, O.; Hermann, R.; Koch, M.; Duffy, K.; Zech, K.; Lahu, G. Effects of Rifampicin on the Pharmacokinetics of Roflumilast and Roflumilast N-Oxide in Healthy Subjects. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2009, 68, 580–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Raymond, K. Roles of Rifampicin in Drug-Drug Interactions: Underlying Molecular Mechanisms Involving the Nuclear Pregnane X Receptor. Annals of Clinical Microbiology and Antimicrobials 2006, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutradhar, I.; Zaman, M.H. Evaluation of the Effect of Temperature on the Stability and Antimicrobial Activity of Rifampicin Quinone. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2021, 197, N.PAG–N.PAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaźniewicz-Łada, M.; Kosicka-Noworzyń, K.; Rao, P.; Modi, N.; Xie, Y.L.; Heysell, S.K.; Kagan, L. New Approach to Rifampicin Stability and First-Line Anti-Tubercular Drug Pharmacokinetics by UPLC-MS/MS. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2023, 235, N.PAG–N.PAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivari-Moshfegh, F.; Javanmardi, F.; Nematollahi, D. A Comprehensive Electrochemical Study on Anti-Tuberculosis Drug Rifampicin. Investigating Reactions of Rifampicin-Quinone with Other Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs, Isoniazid, Pyrazinamide and Ethambutol. Electrochimica Acta 2023, 457, N.PAG–N.PAG. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuna, L.; Corbalán, N.S.; Raisman-Vozari, R. Rifampicin Quinone Pretreatment Improves Neuronal Survival by Modulating Microglia Inflammation Induced by α-Synuclein. Neural Regeneration Research 2020, 15, 1473–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, Z.B.; Zaman, M.H. Evolution of Rifampin Resistance in Escherichia coli and Mycobacterium smegmatis Due to Substandard Drugs. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2018, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mariappan, T.T.; Sharda, N.; Kumar, S.; Chakraborti, A. The Reason for an Increase in Decomposition of Rifampicin in the Presence of Isoniazid under Acid Conditions. Pharmacy and Pharmacology Communications 2010, 6, 405–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Bhandari, R.; Kaur, I.P. Encapsulation of Rifampicin in a Solid Lipid Nanoparticulate System to Limit Its Degradation and Interaction with Isoniazid at Acidic pH. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2013, 446, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pund, S.; Joshi, A.; Vasu, K.; Nivsarkar, M.; Shishoo, C. Gastroretentive Delivery of Rifampicin: In Vitro Mucoadhesion and In Vivo Gamma Scintigraphy. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2011, 411, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohel, M.; Sarvaiya, K. A Novel Solid Dosage Form of Rifampicin and Isoniazid with Improved Functionality. AAPS PharmSciTech 2007, 8, E133–E139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhise, S.B.; More, A.B.; Malayandi, R. Formulation and In Vitro Evaluation of Rifampicin Loaded Porous Microspheres. Scientia Pharmaceutica 2010, 78, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anita, G.S.; Lata, S.M.; Tejraj, M.A. Novel pH-Sensitive Hydrogels Prepared from the Blends of Poly(vinyl alcohol) with Acrylic Acid-graft-Guar Gum Matrixes for Isoniazid Delivery. Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research 2010, 49, 7323–7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, H.K.; Marriott, J.F. Formulations for Children: Problems and Solutions. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2015, 79, 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.E.; Millar, B.C. Readability of Patient-Facing Information of Antibiotics Used in the WHO Short 6-Month and 9-Month All Oral Treatment for Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Lung (0341-2040) 2024, 202, 741–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orubua, E.S.F.; Tuleua, C. Medicines for Children: Flexible Solid Oral Formulations. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2017, 95, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stop TB Partnership Global Drug Facility. Global Drug Facility September 2025 Medicines Catalog. Available online: https://www.stoptb.org/sites/default/files/documents/2025.09.02_gdf_medicines_catalog.pdf (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Schaaf, H.S.; Wademan, D.T.; van der Laan, L.E. Global Child-Friendly Anti-TB Medicines - Where Do We Stand? IJTLD Open 2025, 2, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Principi, N.; Galli, L.; Lancella, L.; Tadolini, M.; Migliori, G.; Villani, A.; Esposito, S. Recommendations Concerning the First-Line Treatment of Children with Tuberculosis. Pediatric Drugs 2016, 18, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIlleron, H.; Hundt, H.; Smythe, W.; Bekker, A.; Winckler, J.; van der Laan, L.; Smith, P.; Zar, H.J.; Hesseling, A.C.; Maartens, G.; et al. Bioavailability of Two Licensed Paediatric Rifampicin Suspensions: Implications for Quality Control Programmes. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2016, 20, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandrini, E.; Brako, F.; Scarpa, M.; Lupo, M.; Bonifazi, D.; Pignataro, V.; Cavallo, M.; Cullufe, O.; Enache, C.; Nafria, B.; et al. Children's Preferences for Oral Dosage Forms and Their Involvement in Formulation Research via EPTRI (European Paediatric Translational Research Infrastructure). Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, C.; Jarak, I.; Veiga, F.; Dourado, M.; Figueiras, A. Pediatric Drug Development: Reviewing Challenges and Opportunities by Tracking Innovative Therapies. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keating, A.V.; Soto, J.; Forbes, C.; Zhao, M.; Craig, D.Q.M.; Tuleu, C. Multi-Methodological Quantitative Taste Assessment of Anti-Tuberculosis Drugs to Support the Development of Palatable Paediatric Dosage Forms. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 369–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolakakis, I.; Partheniadis, I. Self-Emulsifying Granules and Pellets: Composition and Formation Mechanisms for Instant or Controlled Release. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peltonen, L.; Hirvonen, J. Drug Nanocrystals – Versatile Option for Formulation of Poorly Soluble Materials. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2018, 537, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunke, S.; O'Brien, F.; Cheng Thiam Tan, D.; Harris, D.; Math, M.; Ariën, T.; Klein, S.; Timpe, C. Oral Drug Delivery Strategies for Development of Poorly Water Soluble Drugs in Paediatric Patient Population. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2022, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, R.; Kuentz, M.; Ilie-Spiridon, A.-R.; Griffin, B.T. Lipid Based Formulations as Supersaturating Oral Delivery Systems: From Current to Future Industrial Applications. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2023, 189, 106556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurram, A.K.; Deshpande, P.B.; Kar, S.S.; Nayak, U.Y.; Udupa, N.; Reddy, M.S. Role of Components in the Formation of Self-microemulsifying Drug Delivery Systems. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 77, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouton, C.W. Lipid Formulations for Oral Administration of Drugs: Non-Emulsifying, Self-Emulsifying and ‘Self-Microemulsifying' Drug Delivery Systems. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2000, 11 Suppl 2, S93–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, M.; Virmani, T.; Kumar, G.; Deshmukh, R.; Sharma, A.; Duarte, S.; Brandão, P.; Fonte, P. Nanocarriers in Tuberculosis Treatment: Challenges and Delivery Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, H.; Bala, R.; Arora, S. Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems. Journal of Pharmaceutics 2014, 801820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Holm, R.; Müllertz, A. Lipid-Based Formulations for Oral Administration of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2013, 453, 215–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, E.R.; Radha, G.V. Insights into Novel Excipients of Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems and Their Significance: An Updated Review. Critical Reviews in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems 2021, 38, 27–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uttreja, P.; Karnik, I.; Adel Ali Youssef, A.; Narala, N.; Elkanayati, R.M.; Baisa, S.; Alshammari, N.D.; Banda, S.; Vemula, S.K.; Repka, M.A. Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SEDDS): Transition from Liquid to Solid-A Comprehensive Review of Formulation, Characterization, Applications, and Future Trends. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalepu, S.; Manthina, M.; Padavala, V. Oral Lipid-Based Drug Delivery Systems – An Overview. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B 2013, 3, 361–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Michalowski, C.B.; Beloqui, A. Advances in Lipid Carriers for Drug Delivery to the Gastrointestinal Tract. Current Opinion in Colloid and Interface Science 2021, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, E.B.; du Plessis, L.H.; Viljoen, J.M. Solidification of Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems as a Novel Approach to the Management of Uncomplicated Malaria. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salawi, A. Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems: A Novel Approach to Deliver Drugs. Drug Delivery 2022, 29, 1811–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouton, C.W. Formulation of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs for Oral Administration: Physicochemical and Physiological Issues and the Lipid Formulation Classification System. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2006, 29, 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerpnjak, K.; Zvonar, A.; Gašperlin, M.; Vrečer, F. Lipid-Based Systems as a Promising Approach for Enhancing the Bioavailability of Poorly Water-Soluble Drugs. Acta Pharmaceutica 2013, 63, 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azman, M.; Sabri, A.H.; Anjani, Q.K.; Mustaffa, M.F.; Hamid, K.A. Intestinal Absorption Study: Challenges and Absorption Enhancement Strategies in Improving Oral Drug Delivery. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 975–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohli, K.; Chopra, S.; Dhar, D.; Arora, S.; Khar, R.K. Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems: An Approach to Enhance Oral Bioavailability. Drug Discovery Today 2010, 15, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S.; Rana, R.; Saraogi, G.K.; Kumar, V.; Gupta, U. Self-Emulsifying Oral Lipid Drug Delivery Systems: Advances and Challenges. AAPS PharmSciTech 2019, 20, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, O.M.; Crum, M.F.; McEvoy, C.L.; Trevaskis, N.L.; Williams, H.D.; Pouton, C.W.; Charman, W.N.; Bergström, C.A.S.; Porter, C.J.H. 50 Years of Oral Lipid-Based Formulations: Provenance, Progress and Future Perspectives. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2016, 101, 167–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, C.J.H.; Trevaskis, N.L.; Charman, W.N. Lipids and Lipid-Based Formulations: Optimizing the Oral Delivery of Lipophilic Drugs. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2007, 6, 231–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramod, K.; Peeyush, K.; Rajeev, K.; Nitish, K.; Rakesh, K. An Overview on Lipid Based Formulation for Oral Drug Delivery. Drug Invention Today 2010, 2, 390–395. [Google Scholar]

- Kossena, G.A.; Charman, W.N.; Wilson, C.G.; O'Mahony, B.; Lindsay, B.; Hempenstall, J.M.; Davison, C.L.; Crowley, P.J.; Porter, C.J.H. Low Dose Lipid Formulations: Effects on Gastric Emptying and Biliary Secretion. Pharmaceutical Research 2007, 24, 2084–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charman, W.N.; Stella, V.J. Estimating the Maximal Potential for Intestinal Lymphatic Transport of Lipophilic Drug Molecules. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 1986, 34, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, I.; Swami, R.; Khan, W.; Sistla, R. Delivery Systems for Lymphatic Targetting. Focal Controlled Drug. Delivery 2013, 429–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimurni, D. Optimization of Self-Nano Emulsifying Drug Delivery System of Rifampicin for Nebulization Using Cinnamon Oil as Oil Phase. Pharmaciana 2024, 14, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of TB | Regimen | Drugs | Duration (months) | Recommended Regimen | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tuberculosis Infection | 3HR | Isoniazid (H) Rifampicin (R) |

3 | All pediatric patients. Preferred for HIV-negative children <25 kg. | Use dispersible fixed dose combinations if available. Vitamin B6 supplements for selected patients.* |

| 4R | Rifampicin (R) | 4 | All pediatric patients. | No pediatric-friendly formulation is readily available: In adolescents and older children, a rifampicin tablet may be used; compounding or tablet crushing may be necessary for younger children. Use if suspected or resistance to isoniazid. | |

| 6H or 9H | Isoniazid (H) | 6 or 9 | All pediatric patients. Preferred for HIV-positive children on anti-retroviral therapy. | Use if rifampicin is contraindicated or not available. Vitamin B6 supplements for selected patients.* | |

| 3HP | Isoniazid (H) Rifapentine (P) |

3 | ≥2 years. This regimen is not recommended for HIV-positive children. | Administer with fatty food. Vitamin B6 supplements for selected patients.* | |

| Non-severe drug- susceptible TB |

2HRZE/2HR | Isoniazid (H) Rifampicin (R) Pyrazinamide (P) ±Ethambutol (E) |

4 | Pediatric patients ≥3 months to <16 years with non-severe peripheral lymph node or pulmonary TB. | Meets WHO non-severe TB criteria (uncomplicated pleural effusion; non-cavitary, paucibacillary disease. Confined to one lung lobe without miliary pattern; intrathoracic lymph node TB without airway obstruction). Ethambutol optional. Exclude rifampicin resistance. Child-friendly formulations available. |

| Severe drug-susceptible TB | 2HRZE/4HR | Isoniazid (H) Rifampicin (R) Pyrazinamide (P) ±Ethambutol (E) |

6 | All pediatric patients with severe TB. | Include severe pulmonary TB (cavitary, extensive, and miliary TB) and all forms of extrapulmonary TB, except osteoarticular TB and TB meningitis. Ethambutol should always be included in the intensive phase. Child-friendly dispersible formulations available. |

| Osteoarticular TB and TB meningitis | 2HRZE/10HR | Isoniazid (H) Rifampicin (R) Pyrazinamide (P) ±Ethambutol (E) |

12 | All pediatric patients with osteoarticular TB or TB meningitis. | For osteoarticular TB, consider surgical intervention if needed and focus on adherence. For TB meningitis, consider high rifampicin dosages to achieve optimal central nervous system penetration. Add corticosteroids. Initiate treatment in hospital. Monitor for neurological and hepatotoxicity changes. Child-friendly formulations available |

| Property | SEDDSs | SMEDDSs | SNEDDSs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average droplet size | >300 nm | 100–200 nm | <100 nm |

| Appearance | Cloudy/turbid | Clear to translucent | Optically clear |

| Bioavailability | Moderate | Enhanced | Superior |

| Classification as per LFCS | Type II | Type IIIA/IIIB | Type IIIB |

| Concentration of oil | 40–80% | 40–80%/<20% | <20% |

| Concentration of surfactant |

30–40% | 40–80% | 40–80% |

| HBL of surfactants | <10 | 10–12 | >12 |

| Oil types | Long-chain triglycerides |

Medium-chain triglycerides |

Medium- and short-chain triglycerides |

| Solubilizing capacity | High | High | High |

| Stability | Thermodynamically unstable | Thermodynamically stable | Kinetically stable |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).