1. Introduction

Sport is widely acknowledged as a beneficial pathway for youth development; however, its developmental effects are not consistently accessible. A significant portion of the current research is situated within Western or middle-class frameworks, where structural stability, parental engagement, and well-resourced communities influence youth experiences in sport [

1,

2]. Conversely, numerous Malaysian youths from low socioeconomic backgrounds are raised in unstable household environments, inconsistent routines, and restricted access to developmental support networks [

3,

4]. For these youths, participation in sports is an accomplishment, and the quality of adult relationships within sports is a crucial determinant of whether participation fosters significant personal development [

5]. Coaches in these situations often do much more than just teach technical skills. The idea of social fathering describes this broader relational responsibility. In this case, adults who are not part of the biological family offer emotional support, moral guidance, stability, and help with life navigation [

6,

7]. In collectivist Asian cultures, where fatherhood is culturally linked to discipline, responsibility, and moral guidance, this relational shift is particularly consequential for youths whose paternal figures are absent, inconsistent, or overwhelmed by economic pressures [

8]. Social fathering, therefore, is not a voluntary augmentation of coaching but a functional response to deficiencies in youths' developmental contexts [

9].

Structured adversity has concurrently been acknowledged as a relational pedagogy in skill-based sports, including powerlifting. The sport's natural challenges come from its cycle of failure, technical difficulty, and gradual progress [

10]. When a coach carefully chooses these challenges, they can be used as teaching tools to help kids develop grit, resilience, and self-confidence, which are important traits in Positive Youth Development PYD frameworks [

2]. Structured adversity is effective solely when young athletes have the psychological safety to perceive challenges as opportunities for growth rather than threats, a state that is significantly influenced by relational trust and emotional security [

1,

11].

This trust is especially weak for young people from low-SES backgrounds. Numerous individuals experience enduring instability, erratic adult involvement, food insecurity, academic disruption, and familial stress [

4,

12]. These kinds of experiences make it harder for the brain to process information, make people more likely to react to stress, and make them think negatively about failure [

4]. Given these limitations, coaches emerge as one of the scarce reliable adults who can convert challenges into a developmental opportunity. Studies in youth sports indicate that relational warmth, consistent boundaries, and moral modelling are essential for helping disadvantaged youth derive meaning from adversity [

1,

9].

Even though coaching in low-income settings is complicated by relationships and the environment, there are still gaps in the research. First, research on youth sports is still mostly focused on middle-class Western settings and not much has been done on Southeast Asian or economically disadvantaged settings [

18]. Second, the parental and relational labour of coaches—especially their roles as father figures—has not been thoroughly conceptualised within sport studies, particularly in Asian communities where cultural norms of authority and care diverge from Western paradigms [

8]. Third, there is a scarcity of studies employing narrative or autoethnographic methodologies that reveal the lived, emotional, and sociocultural complexities of how structured adversity is perceived by youth undergoing hardship [

13,

14].

This study fills these gaps by looking at two very different cases from an autoethnographic dataset: Derrick, a young athlete from a lower socioeconomic community that is always changing, and Chong, an athlete from a more stable socioeconomic background. Employing Nasheeda et al.’s (2019) three-layered narrative framework, the analysis examines the evolution of the coach–athlete relationship into manifestations of social fathering, the role of structured adversity as relational pedagogy, and the differential co-construction of grit across socioeconomic contexts.

The objective of this article is to analyse developmental trajectories and to elucidate the sociocultural mechanisms by which coaching can mitigate structural disadvantage. This study enhances the comprehension of youth development in marginalised environments by analysing the interplay of relational labour, emotional containment, and structured adversity within unequal contexts, while emphasising the significance of culturally rooted relational ethics in coaching practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed an analytical autoethnographic approach, which integrates first-person experience with systematic sociological analysis [

13]. Autoethnography is particularly suited for examining relational, emotional, and sociocultural dynamics that are often obscured in traditional sport psychology methods. Scholars argue that narrative and autoethnographic approaches are essential for understanding youth development in unequal or marginalised contexts, because they capture lived experience, relational meaning-making, and the cultural embeddedness of coaching [

1,

14].

Analytical autoethnography was selected specifically because:

it allows full reflexive transparency of the coach-researcher role [

13].

it is appropriate for examining power dynamics in relationships such as coach–athlete, mentor–youth, and adult–child [

5,

9].

it aligns with ecological perspectives on youth development where relational processes shape developmental outcomes [

16] and

it enables deep interpretation of sociocultural factors—such as poverty, fatherhood norms, and collectivist values—that cannot be captured through quantitative methods [

6,

8].

Thus, autoethnography provided the methodological rigour and cultural sensitivity necessary to examine structured adversity, social fathering, and grit development.

2.2. Participants and Context

Participants included four youth powerlifters aged 15–19 from Malaysian B40 low-income communities. B40 youth often grow up amid family instability, limited academic resources, food insecurity, and inconsistent paternal [

3,

4]. Such environments influence emotional regulation, resilience, and engagement with sport. The coaching sessions took place in an urban community gym, which functioned as a stable relational environment for youths whose daily lives contained unpredictability. Research shows that stable adult-led programmes are essential developmental anchors for youth experiencing socioeconomic strain [

1,

9].

2.3. Data Collection

Data were collected over 20 weeks using multiple qualitative sources:

Reflective coaching journals, written immediately after sessions

Fieldnotes capturing emotional responses, crises, and relationship dynamics

Informal conversational transcripts documenting youth disclosures

Training logs and performance observations

Using multiple forms of data enhanced depth, triangulation, and analytic reliability, consistent with best practices in qualitative and narrative inquiry [

1,

14].

This multimodal approach is commonly used in youth sport research to capture the micro-dynamics of learning, resilience, and emotional development [

1].

2.4. Analytical Framework

Analysis followed Nasheeda et al.’s (2019) three-layered narrative synthesis:

1 Personal Narrative Layer

Episodic accounts of key coaching moments, recorded immediately after sessions. This captures emotional truth and temporal sequencing, which are foundational to narrative validity [

14].

2 Thematic Interpretation Layer

Coding across narratives identified themes such as:

Theme coding aligns with experiential learning theory [

15] mentoring frameworks [

9], and youth sport development literature [

1].

3 Sociocultural Discourse Layer

Themes were interpreted against broader:

Malaysian cultural fatherhood norms [

8].

structural poverty literature [

12].

ecological development models [

16].

youth resilience theory [

3].

This discourse-level interpretation provides analytical depth and situates individual narratives within systemic and cultural structures—an essential feature of analytical autoethnography [

13].

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical approval from xxx (removed for peer review). All participants and guardians for minors provided written informed consent. Ethical considerations included:

use of pseudonyms

protection of youth disclosures

management of dual relational roles coach + researcher

ongoing reflexive monitoring of power dynamics

Throughout, we remained mindful of the coach–athlete power dynamic [20] participation was voluntary, with athletes reminded they could withdraw at any time, and all shared reflections were treated confidentially. In narrative excerpts, care was taken to present context e.g., community background without attributing blame; structural factors opportunity gaps, resources were highlighted instead of attributing personal failings to athletes. The dual role was addressed using recommended reflexive practices from qualitative mentorship research [

9]. Generative AI ChatGPT was used only for language refinement, data organisation, article structuring and organisational clarity, in accordance with MDPI policy. All interpretation, narrative content, coding, meaning-making, and theoretical analysis were produced solely by the authors.

3. Results

This section presents the findings through a combined narrative–analytic format consistent with analytical autoethnography [

13] and Nasheeda et al.’s (2019) three-layered narrative method. Personal vignettes are interwoven with thematic interpretation and sociocultural discourse. The two embedded cases: Derrick Low-SES context and Chia middle-class context illustrate how structured adversity functions differently depending on youths’ ecological starting points.

3.1. Becoming a Social Father in a Low-SES Context

Derrick entered the programme exhibiting behavioural patterns consistent with youths growing up amid socioeconomic instability—hesitation, hypervigilance, and a heightened sensitivity to adult reactions. Such patterns are well documented among young people navigating inconsistent caregiving, financial hardship, and relational unpredictability [

3,

4]. His early interactions were marked by cautious body language: double-checking equipment setup, repeatedly seeking reassurance, and watching my reactions closely before attempting lifts. This mirrored relational hypervigilance described in mentoring research, where adolescents exposed to inconsistent adult behaviour develop heightened scanning for cues of approval or disappointment [

9].

A defining episode occurred when Derrick collapsed after a squat session and disclosed that he had skipped meals to avoid burdening his mother. This moment revealed more than fatigue—it exposed the cognitive and emotional toll of poverty. Research shows that food insecurity and chronic scarcity significantly impair cognitive bandwidth, attentional control, and the capacity to manage stress [

12]. For Derrick, hunger was not an isolated incident but a structural condition shaping how he approached training, decision-making, and resilience.

Through ongoing reflexive engagement, the coaching relationship expanded into what literature identifies as

social fathering—a form of relational mentorship in which caring adults assume stabilising, protective, and morally guiding roles typically associated with fatherhood [

6,

7]. Derrick sought support for school decisions, identity concerns, family conflicts, and emotional turmoil. These were not incidental conversations; they were developmental interactions shaped by cultural expectations. In collectivist Malaysian settings, paternal authority is associated with moral guidance, structured discipline, emotional containment, and interpersonal responsibility [

8]. Derrick’s quick alignment with firm boundaries and moral dialogue—such as punctuality rules, behavioural expectations, and goal-setting—reflects research showing that Asian youths interpret authoritative instruction as care rather than coercion due to cultural scripts surrounding fatherhood and hierarchy [

8].

Thus, becoming a social father was not a self-designated identity but an emergent relational necessity arising from Derrick’s structural environment and cultural background. Narrative analysis reflected how Derrick’s developmental needs—stability, moral guidance, emotional containment—aligned with the relational functions described in youth mentoring and resilience literature [

1,

9]. The coaching environment became a predictable relational “anchor,” compensating for gaps common in low-SES developmental ecologies [

3].

3.2. Structured Adversity as Relational Pedagogy

Powerlifting poses significant challenges for athletes due to gradual improvement, recurrent setbacks, technical complexities, and physical discomfort. Nevertheless, hardship by itself does not foster resilience or strength. Research on challenge-based coaching emphasises that adversity contributes to growth only when it is adequately supported by emotional safety, reflective discourse, and facilitated meaning-making [

10,

15]. Derrick perceived failure as a significant obstacle throughout the initial stages of his training. When an individual misses a lift, they frequently utter apologies such as "Coach, I failed you," akin to the shame-driven reactions exhibited by adolescents confronting tumultuous familial circumstances [

4]. In the absence of relational reframing, hardship could have reinforced entrenched perceptions of inadequacy.

Consequently, structured adversity was intentionally adjusted. Training cycles were designed to induce tolerable pain followed by reflective discussion—a challenge-support framework consistent with Positive Youth Development [

1] and experiential learning theory [

15]. For instance, when Derrick repeatedly struggled to lift a heavy bench, the debriefing focused on technique, respiration, and maintaining composure under pressure, rather than the outcome. This aligns with research indicating that adolescent athletes perform better when they perceive their setbacks as chances for learning rather than as determinants of their identity [

2].

As trust developed, Derrick began to perceive challenges as chances for advancement rather than as threats to his well-being. This trajectory corresponds with Collins and MacNamara’s 2017 notion of “appropriate challenge with support,” emphasising that resilience is cultivated through a synthesis of adversity and relational direction. In this environment, organised adversity functioned as relational pedagogy: a teaching method in which discomfort is imbued with meaning through a trusting, father connection that provides emotional stability and constructive critique [

1].

3.3. Co-Construction of Grit Under Socioeconomic Hardship

Derrick's growth put individualistic ideas about grit to the test. Initially, his perseverance was externally regulated, stemming not from intrinsic passion but from relational accountability and the intention to avoid disappointing a trusted adult. This is in line with Self-Determination Theory, which says that behaviours that are controlled by outside forces come before the process of internalisation, which is when motivation becomes independent [

11]. For adolescents without stable adult influences, early resilience frequently develops through co-regulation within a nurturing relationship rather than through intrinsic motivation [

9].

As the relationship grew stronger, Derrick started to understand what disciplined training meant. He went from "I don't want to fail you" to "Give me two minutes, I'll hit it," which shows a change from introjected regulation to identified regulation. This is in line with SDT's motivational continuum [

11]. Learning by watching others was also very important. Derrick often talked about my own workload, which included coaching, writing my dissertation, and doing things for the community. Bandura 1997 underscores that adolescents internalise perseverance by observing influential adults demonstrating consistent effort amidst challenges.

This collaboratively developed pathway addresses recent criticisms of grit, positing that perseverance in structurally disadvantaged environments is not an inherent characteristic but rather arises from relational modelling, external frameworks, and contextual support [

18]. Derrick's journey shows how grit develops from the outside in, starting with relational anchoring and slowly becoming something that comes from within.

3.4. Sociocultural Mechanisms Shaping the Relationship

Derrick's growth trajectory was intrinsically connected to cultural and social influences. Research on poverty demonstrates that persistent stress, food scarcity, and insecure surroundings impede executive performance and emotional control [

12]. Derrick's immediate response to mistakes and his difficulties in maintaining concentrate throughout prolonged sessions highlighted these limits.

Derrick's comprehension of coaching practices was influenced by Malaysian cultural norms of parenting, rooted on collectivist principles of duty, discipline, and relational accountability. Strict limitations, constructive feedback, and ethical discussions were perceived not as punitive measures but as indicators of concern, aligning with culture studies on Asian paternal expectations [

8]. Researchers in youth development contend that culturally aligned relational authority cultivates trust and accelerates resilience in adolescents [

1,

9].

This indicates that the coaching relationship integrated into broader ecological systems, consistent with Bronfenbrenner's (2005) bioecological paradigm. This concept posits that growth is influenced by continuous interactions between an individual and their structural, social, and cultural contexts.

3.5. Comparative Case: Chong’s Development in a Stable SES Ecology

Chong's growth trajectory markedly diverged from Derrick's due to differing ecological and social roots. Chong sprang from a stable middle-class home, indicating his proficiency in emotional regulation, adherence to structured routines, and the active involvement of his parents in his life—characteristics emblematic of intentional nurturing [

19]. In the face of challenges, he addressed them with critical thinking: modifying his technique, altering his breathing, and perceiving failure as constructive feedback. This aligns with studies on experiential learning, which indicates that adolescents in stable contexts are more inclined to perceive mistakes as opportunities for learning rather than threats to their identity [

15].

Structured adversity functioned as a performance catalyst for Chong, as his essential physiological and emotional requirements were fulfilled. He could immediately begin training blocks characterised by substantial volume or significant difficulty, indicating that his mental capacity was elevated [

12]. His resilience evolved rapidly and autonomously due to internalised competence, perceived autonomy, and supporting social frameworks—conditions aligned with the requirements for intrinsic motivation outlined in Self-Determination Theory [

11].

The disparity between Derrick and Chong illustrates the impact of ecological inequality on the development of youth. Derrick need emotional support, a paternal figure, and a secure environment, whereas Chong sought technical enhancement and an appropriate level of challenge. These differences exemplify Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) claim that growth is structurally controlled and Thomas et al.’s (2020) argument that grit is influenced by socioecological conditions rather than being evenly distributed across kids.

The contrast in

Table 1 demonstrates that

grit is not merely an individual trait, but a

relational and socio-structural outcome. Derrick’s grit had to be built through co-regulation and father-like coaching labor, while Chia’s grit emerged through structured challenge embedded within a stable developmental ecology.

4. Discussion

This analytical autoethnography examined the coach–athlete relationship as a form of social fathering among Malaysian low SES young powerlifters, and how controlled adversity functioned as relational pedagogy to cultivate grit, resilience, and Positive young Development PYD. Examining the results using Nasheeda et al.’s (2019) narrative layering and Anderson’s (2006) analytical autoethnography clarifies the substantial impact of socioeconomic disparity, cultural norms, and the relational efforts of coaches on developmental pathways. The contrasting paths of Derrick who has a low socioeconomic status and Chong middle-class illustrate that adversity does not uniformly impact all adolescents; its relevance and developmental potential are shaped by relationship safety, emotional capability, and sociocultural context.

4.1. Social Fathering as Relational Labor in Disadvantaged Contexts

Derrick's case exemplifies how coaches in economically disadvantaged settings often undertake relational and caregiving responsibilities that transcend mere technical sport instruction. This is in line with research on development that shows that teens who live in unstable, food-insecure, and inconsistent adult presence environments depend on non-parental adults for emotional regulation and life navigation support [

3,

4]. Mentoring literature underscores that relational proximity, stability, and trust are essential for youth encountering adversity [

9]. These dynamics align with social fathering, wherein adult mentors adopt protective, guiding, and stabilising roles conventionally attributed to fathers [

6,

7].

In Malaysian collectivist contexts, fatherhood is socially constructed around responsibility, moral leadership, boundary-setting, and disciplined care [

8]. Derrick's willingness to perceive firm guidance and corrective feedback as expressions of care rather than criticism aligns with these cultural norms. This cultural resonance enhances the relational influence of coaching behaviours, solidifying the developmental role of the coach as a paternal figure. The relationship served as a stabilising microsystem that mitigated structural stressors, aligning with Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) ecological model, which highlights the developmental impact of proximal relationships in the context of environmental stress.

4.2. Structured Adversity as Relationally Mediated Pedagogy

The findings underscore that adversity alone does not produce growth; it must be structured and relationally mediated to yield developmental outcomes. Research demonstrates that challenge becomes pedagogical when paired with emotional safety, guided reflection, and consistent adult support [

10,

15]. For Derrick, early experiences of failure activated shame and fear of disappointing a significant adult—patterns historically linked to youths who grow up amid inconsistent caregiving or high-stress environments [

4]. Without intervention, adversity can exacerbate insecurity rather than build resilience.

Through relational scaffolding, structured adversity became a guided learning process. Positive Youth Development literature emphasises that safe, supported engagement with difficulty strengthens competence, character, and resilience [

1,

2]. By reframing failures as learning opportunities, providing emotional containment, and calibrating training difficulty based on Derrick’s psychological readiness, structured adversity aligned with evidence-based challenge–support models [

10].

Importantly, Derrick’s ability to reinterpret adversity depended on relational trust—echoing mentoring research showing that psychological safety is essential for youths to reinterpret hardship constructively [

9]. Meanwhile, Chong—whose home environment provided emotional stability and cognitive bandwidth—was able to treat adversity analytically and productively from the outset [

12]. This difference reinforces that adversity must be tailored to each youth’s ecological capacity.

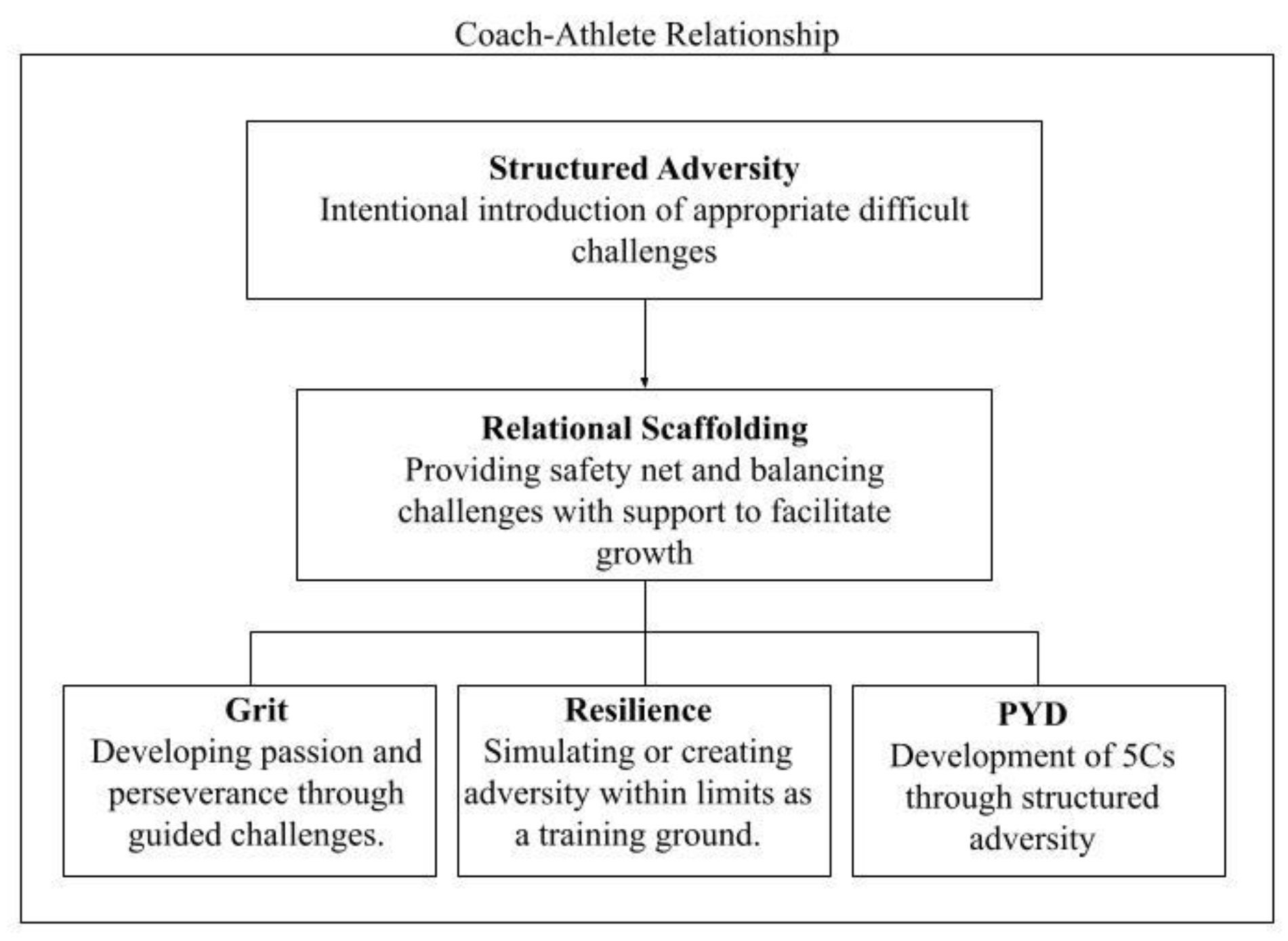

Figure 1 shows the Theory of Structured Adversity Framework. The framework that was developed to mediate youth athletes to developmental outcomes out of adversity.

Theory of Structured Adversity Framework

According to TSA, youth development accelerates when adversity is carefully structured within a strong, trust-based coach–athlete relationship. Here, adversity is not an uncontrolled variable but a deliberately crafted opportunity for growth, contingent on emotional safety and relational scaffolding.

Coach–Athlete Relationship as Container: This relationship provides the emotional trust, empathy, and respect needed to create psychological safety. As SDT suggests, when autonomy, competence, and relatedness needs are supported, youth are more likely to internalize motivation and embrace growth-oriented challenges.

Relational Scaffolding: Coaches adjust the difficulty and timing of challenges based on each athlete’s emotional and cognitive readiness – following Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development and Kolb’s experiential learning cycle. Challenges are introduced alongside guided reflection and support, which enables learning and gradual confidence-building.

Key Developmental Outcomes: Guided perseverance-built grit. Controlled stress-and-recovery cycles developed resilience. Emotionally intelligent coaching fostered the 5Cs of PYD: Competence, Confidence, Character, Connection, and Caring.

Table 2.

4 Phases of Theory of Structured Adversity.

Table 2.

4 Phases of Theory of Structured Adversity.

| Phase |

Condition/Trigger |

Mechanism (Coach Action) |

Athlete Response/Outcome |

| Challenge Introduction |

Emotional safety and trust present |

Coach introduces structured adversity (e.g., competition, high-load training) |

Initial struggle; reliance on coach support |

| Structured Scaffolding |

Motivation-skill mismatch |

Coach adjusts, mentors, reflects with athlete |

Improved effort, emerging confidence |

| Relational Reflexivity |

Ongoing athlete development |

Coach shifts strategy to empower athlete |

Ownership of process; autonomy begins |

| Internalisation |

Sustained adversity + trust |

Athlete leads effort, reframes failure |

Internalised grit; identity and resilience strengthen |

4.3. Grit as a Socioecologically Constructed Capacity

The study challenges trait-based explanations of grit by clarifying its social, contextual, and socioecological foundations. Derrick's endurance first emerged through co-regulation, driven by relational accountability rather than intrinsic motivation. This corresponds with the framework of Self-Determination Theory, which progresses from external to introjected, identifiable, and integrated motivation [

11]. Studies on youth mentoring demonstrate that resilience in underprivileged teenagers often arises from supportive connections rather than own initiative [

9].

As relationship trust grew, Derrick transitioned from externalised perseverance "I do not wish to disappoint you" to internalised commitment "Allow me two minutes; I will accomplish it". This modification aligns with the Self-Determination Theory SDT road to autonomous motivation [

11] and with research on experiential learning, which indicates that deriving meaning transforms effort from coercion to self-direction [

15]. Bandura’s 1997 social modelling theory elucidates how Derrick’s observation of my sustained effort shaped his understanding of perseverance.

In contrast, Chong demonstrated internalised grit earlier, owing to basic frameworks of emotional control and parental support—conditions associated with middle-class "concerted cultivation" that foster adaptive interpretations of failure [

19]. This gap supports Thomas et al.’s (2020) claim that grit is affected by social status, environmental stability, and the presence of relationship support.

Thus, grit is not a uniformly distributed psychological trait; instead, it is a capability that varies across socioeconomic settings, shaped by relationship support, environmental stability, and cultural significance.

4.4. Socioeconomic and Cultural Mechanisms Shaping Development

The divergent developmental trajectories of Derrick and Chong reflect broader ecological systems. Poverty restricts cognitive bandwidth, heightens stress reactivity, and diminishes problem-solving capacity [

12], which can impair youths’ ability to interpret or endure adversity. B40 youths often lack the stable relational scaffolds needed to contextualise difficulty constructively, making the coach’s role as a consistent, trustworthy adult particularly impactful [

3,

9].

Cultural expectations also shaped relational dynamics. In Malaysian collectivist communities, respect

hormat, hierarchy, and paternal authority structure interpersonal communication. Youth often interpret firm guidance, discipline, and moral correction as expressions of care rather than coercion [

8]. Derrick’s receptivity to boundaries, discipline, and relational firmness is consistent with this cultural framework, enabling social fathering to function as a culturally meaningful developmental mechanism.

Chong’s responses, however, were influenced by stable routines, family support, and the emotional resources typical of middle-class households [

19]. His interpretation of adversity as iterative learning reflects the cognitive and emotional surplus afforded by his environment [

12].

Together, these findings illustrate that youth development is deeply embedded in structural and cultural systems—supporting Bronfenbrenner’s (2005) assertion that developmental outcomes emerge from interactions between individual, relational, and ecological contexts.

4.5. Implications for Coaching, Youth Development, and Policy

Findings highlight several implications:

1 Coaching in low-income settings is relational labour

Coaches must provide emotional containment, predictability, and moral guidance in ways that compensate for structural gaps, reflecting social fathering roles [

6,

7].

2 Structured adversity must be calibrated

Unsupported adversity harms vulnerable youth; growth emerges only when challenge is paired with relational safety and cultural resonance [

1,

10].

3 Coach education should integrate SES and cultural training

Understanding poverty’s cognitive effects [

12], Malaysian fatherhood norms [

8], and collectivist relational ethics is essential.

4 Grit should be reframed as relational and contextual

Perseverance emerges through structure, modelling, and relational trust—not individual willpower alone [

11,

18].

5 Youth sport policy must recognise relational labour

Policy frameworks should treat coaching as a developmental intervention, not merely a technical one [

1,

9].

5. Conclusions

This analytical autoethnography demonstrates that coaching in low-income Malaysian contexts extends beyond technical aspects, representing a type of relational labour shaped by social, cultural, and developmental inequalities. Derrick's and Chia's trajectories illustrate that teenagers' responses to problems are significantly shaped by their ecological environments [

16]. Derrick's experiences of instability, food insecurity, and an unreliable paternal presence reduced cognitive capacity and positioned adversity as a threat instead of a learning opportunity—patterns thoroughly documented in adolescents facing chronic socioeconomic stress [

4,

12]. Under these conditions, structured adversity promoted development solely when combined with trust, emotional support, and social mentorship, emphasising mentoring and positive youth development studies that underscore the significance of relational safety in youth development [

1,

2,

9].

Conversely, Chia's findings indicated that stability, routine, and parental support provide adolescents with the psychological capacity to evaluate and constructively interpret adversity, consistent with studies on middle-class developmental environments [

19]. His swift shift to internally driven grit exemplifies Self-Determination Theory's assertion that autonomous motivation arises most effectively when fundamental needs are satisfied and experiences that enhance competence are consistently provided [

11].

The study demonstrates that organised adversity does not function consistently across different socioeconomic environments. Adversity for at-risk adolescents must be perceived differently; otherwise, it exacerbates their fears. Grit is not a fixed trait; instead, it is an ability influenced by social and ecological factors, emerging from relational modelling, scaffolding, and environmental predictability [

18]. These findings challenge universalist narratives of endurance and highlight the need for locally relevant techniques in young sports instruction.

The study affirms the significance of paternal mentoring within Malaysian collectivist cultures, where moral advice, boundary setting, and disciplined care are regarded as expressions of duty [

8]. Social fathering arose not from intention but from structural necessity, highlighting the crucial role of coaches as stabilising figures in the lives of youth facing adversity [

6,

7].

The findings contribute to the understanding of sports coaching by demonstrating that youth development must be comprehended at the intersection of relationships, adversity, and socioeconomic background. Structured adversity may cultivate resilience and determination, if it is adapted to the youth's ecological setting and delivered within a trustworthy, culturally pertinent relationship. This underscores the imperative for practitioners and policymakers to integrate relational ethics, contextual awareness, and SES-sensitive coaching methodologies into youth sport systems, ensuring that sport transforms into a conduit for meaningful human development rather than solely a medium for performance.

Author Contributions

Removed for peer review.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Removed for peer review.

Informed Consent Statement

Removed for peer review.

Data Availability Statement

Removed for peer review.

Acknowledgments

Removed for peer review.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5Cs |

Competence, Confidence, Character, Connection, and Contribution |

| PYD |

Positive Youth Development |

| SDT |

Self-Determination Theory |

| SES |

Socioeconomic Status |

References

- Holt, N.L.; Neely, K.C.; Slater, L.; Camiré, M.; Côté, J.; Fraser-Thomas, J.; MacDonald, D.J.; Strachan, L.; Tamminen, K. Positive youth development through sport: A review. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2017, 10, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lerner, R.M.; Almerigi, J.; Theokas, C.; Lerner, J.V. Positive youth development: A developmental systems view. J. Early Adolesc. 2005, 25, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, E.P.; Geldhof, G.J.; Johnson, S.K.; Hilliard, L.J.; Hershberg, R.M.; Lerner, J.V.; Lerner, R.M. Promoting positive youth development: Lessons from the 4-H study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 978–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Davies, P.T. Poverty and child development. Child Dev. Perspect. 2010, 4, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Cockerill, I.M. Olympic medalists’ perspective of the athlete–coach relationship. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M. ‘My father, my coach’: Exploring social fathering in sport. Sport Educ. Soc. 2012, 17, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garza, R.; Dodge, T. Adult mentors as father figures in youth development. J. Adolesc. Res. 2020, 35, 187–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.; Yusof, M.R. Fatherhood in Malay Muslim families: Roles, expectations, and cultural scripts. Malays. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2021, 6, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, R.; Basualdo-Delmonico, A.; Walsh, J.; Drew, A.L. Youth mentoring and relational resilience. Adolesc. Res. Rev. 2021, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, D.; MacNamara, Á. The rocky road to the top: Why talent needs trauma. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 1335–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, A.; Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E.; Zhao, J. Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 2013, 341, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, L. Analytic autoethnography. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 2006, 35, 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasheeda, A.; Abdullah, H.; Krauss, S.E.; Ahmed, N.B. Transforming transcripts into stories: A multimethod approach to narrative analysis. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2019, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development, 2nd ed.; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The bioecological theory of human development. In Making Human Beings Human; Bronfenbrenner, U., Ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2005; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, E.L.; Dineen, J.; Allen, K.A. Rethinking grit in youth development: A socioecological perspective. Youth Soc. 2020, 52, 1053–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lareau, A. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, 2nd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).