1. Introduction

Grit, defined as the combination of passion and perseverance for long-term goals, is widely recognized as a key factor in achievement and success (Duckworth, 2007). Duckworth et al. (2016) conceptualize grit as sustained effort and interest over years despite setbacks. In traditional accounts, grit is often portrayed as an internal trait, maintained by an individual largely on their own. However, recent perspectives suggest that grit can also develop through external influences. For example, sustained involvement in organized sports has been linked to greater grit: one longitudinal study found that adults who persevered in youth sports scored higher on grit measures later in life than those who quit early (Albert, 2016). Such findings imply that grit development may be dynamic and context-influenced, with external structures (training, mentorship, social support) eventually internalizing into personal motivation. In youth sport contexts, grit is often hailed as a desirable trait that can predict long-term performance and retention, sometimes more than talent alone.

Sports like powerlifting demand extraordinary commitment: progress is often slow, and training routines are rigorous, which can easily demotivate less persistent youths. At the same time, a coach’s influence can significantly shape a young athlete’s tenacity. Coaches set challenges, frame failures as learning experiences, and model persistence potentially “seeding” grit in their athletes. (Tiwari & Verma, 2023) Larson’s (2000) theory of “structured voluntary activities” that structured sports activities often produce positive youth outcomes.

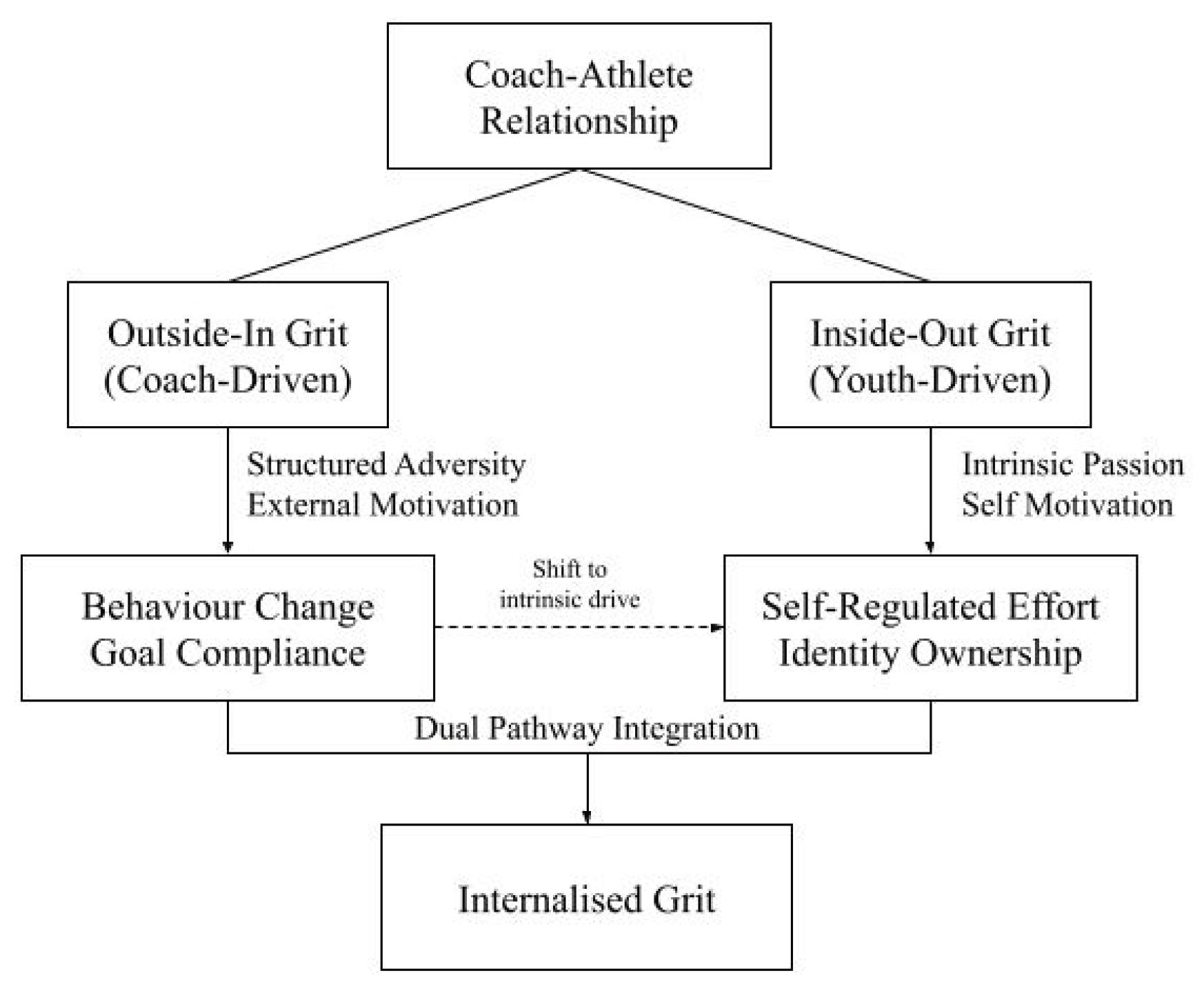

In this article, we introduce a dual-pathway model of grit development in youth sport. In the Outside-In pathway, external influences (coaching, structured programs, support) spark and build an athlete’s perseverance (Menéndez Blanco, 2021). In the Inside-Out pathway, the athlete’s own emerging passion and autonomy drive their long-term commitment. These pathways are not mutually exclusive: an athlete might begin with outside-in grit (following coach-driven goals and structure) but eventually internalize that perseverance as their own. Conversely, some may enter sport with high inside-out drive and then benefit from external guidance and structure along the way.

Our study illustrates this model through a qualitative case study of a youth powerlifting program. The focal case is “Dane” a 15-year-old boy from an underserved community who initially lacked direction and confidence. Dane’s journey exemplifies an Outside-In to Inside-Out transformation: he started as a disengaged teen motivated by the coach’s support and structure and evolved into a self-driven national-calibre athlete with his own passion and purpose. We contrast Dane’s story with those of three other lifters to highlight different pathways “Chan”, a 19-year-old Chinese male from an affluent, highly supportive family, initially had trouble with independent motivation despite plentiful external support. In fact, Chan admitted he had “nothing to worry about at home” where his parents “took care of everything for him”—so he was unaccustomed to making his own decisions or sustaining motivation without direction. “Hailey” and “May”, both 16-year-old girls from stable middle-class families, joined the program with strong intrinsic enthusiasm. Quiet and self-motivated, they needed minimal external prodding and largely drove their own training from the start. Their grit was already high upon arrival and primarily required encouragement and technical support from the coach.

All four athletes trained together in the same gym under the coach’s supervision, typically 3–4 times per week. The program emphasized both physical development and character growth (aligned with the “5 Cs” of Positive Youth Development—competence, confidence, connection, character, caring) (Lerner, 2005). Competitions during this period included a national qualifying meet (January 2025) for which Dane, Hailey, and May prepared, and a state youth meet (October 2024) where Chan had his first competition.

Specifically, we investigated how the two pathways play out in a real program: Do structured challenges and coaching support activate grit, and how is that grit later internalized by the youth? What personal and contextual factors influence each athlete’s pathway? We address these questions by analysing our case data in depth. Our study uses an analytic autoethnographic case-study approach: the first author was both coach and researcher. This insider perspective provided rich insight into coaching decisions, athlete interactions, and personal reflections over the 20-week training period. The coach kept a reflexive journal and collected data on athlete experiences throughout. We triangulated multiple sources including the coach’s journal, informal interviews and conversations, and the athletes’ written reflections and preserved participants’ authentic voices through direct quotations.

By grounding our analysis in lived experience, we aim to deepen Duckworth’s grit theory in the sports context: demonstrating how grit can be cultivated through outside-in coaching strategies (e.g., structured adversity, encouragement, mentorship) and how, over time, this grit must be claimed inside-out by the youth themselves (through intrinsic commitment and self-regulation). This relational-developmental perspective aligns with positive youth development frameworks and offers practical insights for coaches and mentors. Ultimately, we suggest that grit is not strictly a personal trait one “born with,” but often a flame lit by others that young athletes eventually take ownership of.

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design and Approach

This study employed analytical autoethnography within a qualitative case study framework. As Anderson (2006) proposed, analytical autoethnography emphasizes both the researcher’s active role and theoretical engagement, allowing for deep reflection while remaining analytically rigorous. The first author functioned as both coach and researcher, offering an insider’s view into youth athlete development. Such dual positioning is increasingly recognized as valuable in sport research, enabling a deeper understanding of lived experiences in dynamic, social environments (Gearity, 2024).

Autoethnographic methods are especially appropriate for exploring personal and contextual influences on identity and motivation in sports, as they facilitate the integration of subjective insight with sociocultural analysis (Carter, 2016). Ethical standards were upheld through university Institutional Review Board approval and informed consent processes, including parental consent for minors. All identifying information has been pseudonymized for participant protection.

2.2. Participants and Context

Four adolescent powerlifters participated over ~20 weeks of preparation for competitions. These cases reflected a range of socioeconomic backgrounds and motivational profiles, offering diverse insights into grit development. Such purposive sampling aligns with case study norms, aiming for information-rich participants relevant to the research focus (Gebhardt, 2023).

Dane, central case: A 15-year-old male from a low-income urban community. Initially shy and disengaged, he had low confidence and no clear future goals. He described himself as having “never imagined a life beyond Angsana…struggling to make ends” (a local neighborhood school). He joined powerlifting in 2021 with no prior experience and assumed he would simply work after school.

Chan, contrast case 1: A 19-year-old male from an upper-middle-class family. His parents were highly involved and affluent, so Chan admitted having “nothing to worry about” at home—others “took care of everything for him”. He enthusiastically joined powerlifting, but he had rarely had to motivate himself independently. He often doubted himself in training and felt anxious about competition, needing direction on what goals to set. His situation highlighted a contrast: despite many outside advantages, he lacked internal drive.

Hailey, contrast case 2: A 16-year-old female from a middle-upper-income, educated family. Quiet and introspective, Hailey joined in mid-2024 with a disciplined history in other activities and supportive parents. She approached powerlifting with self-driven dedication: punctual, diligent, and motivated by personal challenge rather than external rewards. Her perseverance was intrinsic from the start, exemplifying the Inside-Out pathway.

May, contrast case 3: A 16-year-old female training alongside Hailey. Like Hailey, May came from a stable middle-class background with involved parents and prior structured activities. Gentle and cheerful, she nonetheless had high intrinsic motivation for powerlifting. Both girls “knew what they wanted” and committed to training largely from personal enjoyment. They rarely needed external prompting to persist.

All four athletes trained together in the same community gym under the coach’s guidance, typically 3–4 times per week. The program emphasized not only physical training (strength and technique) but also character development (aligned with positive youth development principles). Each session often included goal setting, mental skills discussion, and reflection on effort and sportsmanship. As noted, competitions during this period were a national qualifier (January 2025) and a state meet (October 2024).

2.3. Data Collection

We triangulated multiple qualitative sources to capture the grit-development process:

Coach’s Autoethnographic Journal: The coach kept a detailed reflexive journal throughout the 20-week program. After each session or event (often writing 1–2 pages immediately afterward), he recorded both external observations (e.g., athletes’ behaviors, dialogue, lift results) and internal reflections on his coaching decisions and emotions. This journal provided a rich, real-time account of the evolving coach–athlete relationships and the coach’s mindset. (Rahayuni, 2022).

Interviews and Conversations: Many informal interviews and conversations occurred organically during training, car rides, and breaks. The researcher also conducted a few semi-structured interviews at key milestones (mid-season and post-competition) to elicit each athlete’s perspective on motivation, challenges, and the coach’s role. These were audio-recorded or noted with permission. We later used direct quotations from these interviews to present the youths’ voices verbatim in the Results.

Athlete Journals and Writings: Athletes were invited to write brief reflections during the program. For instance, Chan kept a personal training journal where he recorded his goals and struggles. In it, he wrote motivational goals like “I hope to hit a 100-kg bench and a 160-kg squat… I don’t want to go down without a fight… even if I lose, I want to at least make it close”. Such writings gave insight into the athletes’ self-talk and goal setting. (Jung & Kwon, 2023)

Field Observations: As coach, the researcher noted significant moments during training and competitions. He made brief mental notes during practice and formally recorded observations during competitions, including each athlete’s emotional state under pressure. These field notes added contextual richness beyond interviews and journals.

All data were organized by participant and chronology. The prolonged engagement (five months of training together) and multiple sources provided depth and credibility to our analysis.

2.4. Data Analysis

We followed a thematic narrative approach. The researcher immersed himself in the data (journals, transcripts, and notes) and engaged in coding, mixing theory-driven and data-driven codes. All data were coded and managed using qualitative analysis software (NVivo) and LLM such as ChatGPT-4o to support the coding process and identification of repeated codes and keywords.. In initial coding, we applied theory-informed codes (e.g., “perseverance,” “coach support,” “autonomy”) alongside emerging phrases (e.g., “finding his own fire,” “structured adversity”). Key themes identified included: Structured Adversity (the coach’s deliberate use of challenges to build resilience), Coach–Athlete Bond (the mentor-like relationship fostering trust and motivation), and Outside-In vs. Inside-Out Growth (the shift from external drive to internal drive over time).

We constructed detailed case narratives for each athlete (with emphasis on Dane) and conducted cross-case comparisons. This iterative process refined our dual-pathway model and revealed how contextual factors (e.g., socioeconomic background, gender) influenced each journey. For rigor, we used member checking and peer debriefing. For example, Dane reviewed the description of his transformation and affirmed it “felt right”. A coaching colleague reviewed our interpretations (anonymized) and confirmed they resonated with his observations. Throughout analysis, the researcher maintained reflexivity, questioning his potential biases (e.g., writing in his journal, “Am I empowering them or creating dependency?”). These practices added credibility to our analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Outside-In: Building Grit through External Structure and Support

Early in the program, grit in these youth was largely an outside-in phenomenon, sparked and shaped by external forces, especially the coach–athlete relationship and structured challenges. Most athletes did not start with an innate passion for powerlifting; rather, their perseverance was cultivated by the environment. Aligns with Braun et al. (2024) says that coaching behaviors significantly influence an athlete’s motivation, persistence, and grit, particularly during formative stages of development. This was most striking in Dane’s case. When Dane first entered the gym, he was a shy 15-year-old lacking confidence and direction.

“I used to not even care about doing my homework,”

Dane admitted,

“and now I do. And now I am on time. More punctual.”

This change had not come from within at first, but from the new structure around him. This pattern reflects what Longakit et al. (2024) describe: strong coach–athlete relationships fulfill adolescents’ psychological needs (autonomy, competence, relatedness), enhancing extrinsic motivation that may later evolve into intrinsic commitment (Longakit et al., 2024).

As Dane’s coach, I deliberately created a challenging but supportive training regimen to build his grit. Dane “needed a structured adversity to push him beyond his limited belief system.” His first major challenge was agreeing to compete in a powerlifting meet. Initially, Dane was apprehensive: competition was far outside his comfort zone, and his low self-esteem made him fear failure. Our decision to enter him in a meet was the first structured adversity which is an intentional, difficult goal set by coaches. Such structured adversity, intentionally designed to challenge limits, is a recognized method for fostering grit and resilience which supported study done by Weight et al. (2024): adversity and grit in U.S. college athletes found that athletes who faced structured challenges demonstrated greater perseverance, confidence, and identity transformation over time.

Dane eventually agreed to compete “due to our coach–athlete relationship that is built on trust.” He did not want to let his coach down. He was motivated extrinsically by our expectations and encouragement where coach leadership style significantly correlates with athletes’ grit and satisfaction in training environments (Sumarsono et al., 2023). Through consistent feedback, structure, and trust, coaches can “seed” grit before it is internalized.

As he later said,

“Coach, you taught me to be mature and independent… to make decisions even when friends pressure me”.

In these early stages, Dane’s grit was coach-driven: I set the goals, and he worked hard to meet them, developing good habits along the way. This structured environment with a fixed schedule, clear targets, and accountability—gave Dane a framework within which to persist.

We can see Dane’s transformation even before his own internal fire fully ignited. His attendance and punctuality improved dramatically. He went from an indifferent student to someone who “now does” his homework and manages his time, as he proudly noted. These behavioral changes were driven in part by the discipline of sport. Showing up to training consistently became non-negotiable, and that discipline “spilled over” into other areas of his life. For example, his teacher observed that within two years he had transformed from a shy, disengaged boy into an active student with leadership qualities. Such cross-domain improvements were seeded by the outside-in cultivation of character through sport which aligns with resiliency theory which posits that skills developed in structured adversity can generalize to broader life domains (Weight et al., 2024). In Dane’s early months, the coach effectively served as a grit provider. I often wore multiple hats; a cheerleader, taskmaster, and mentor which reinforced habits linked to grit and long-term success. (Erickson et al., 2011).

Dane later reflected,

“I never envisioned becoming a national athlete, but Coach, you taught me to be mature and independent”

underscoring that values of dedication and persistence were being taught and reinforced externally. He did not initially see himself as capable of great things, but through consistent training and affirmation, his worldview expanded. The gym and coaching became a “protective factor” in his life, steering him away from negative options and giving him purpose.

Other participants exhibited similar outside-in beginnings, albeit in different forms. Chan, for example, had plenty of external support—perhaps too much. His parents and family created a comfortable cushion around him, which led to a kind of complacency. When he joined powerlifting, Chan was enthusiastic but easily demoralized by difficulties. He often “struggled with self-doubt and anxiety,” finding it hard to push himself without external direction. This contrast highlights that too much support can sometimes inhibit an adolescent’s initiative. In Chan’s early training, the coach also had to play the role of motivator and mentor, guiding him through self-confidence issues.

In summary, during the early stage, each youth’s grit was largely built from the outside-in. The coach’s structured programs, the challenges of competition, and the supportive relationship provided the spark of perseverance. Each athlete responded by meeting the coach’s expectations and sticking with the regimen, even before a fully internal passion had developed.

3.2. Inside-Out: Internalizing Passion and Ownership of Grit

As the season progressed, it became evident that long-term success would require a shift from external to internal motivation. According to SDT, for motivation to be self-sustaining, individuals must experience autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Lozano-Jiménez et al., 2021). The ultimate goal was for each athlete to own their grit, to persevere because they wanted to, not just because others wanted them to (Sullivan, 2019). If a young athlete never develops that internal desire, their commitment remains fragile. For example, many of Dane’s peers quit the sport once the coach’s constant pressure lifted;

“they never developed that internal desire for the sport… we coaches wanted it more for them than they wanted for themselves”.

We observed that athletes who failed to claim the goal as their own tended not to persist. Thus, facilitating a move from outside-in to inside-out became a central coaching task.

Dane’s Turning Point

Dane reached a pivotal moment during a candid conversation after practice. Sensing that I had been driving his goals,

I bluntly asked him:

“Who do you think wants success more—you or me?”.

This question hit home. Dane realized that I could not carry his motivation indefinitely. Reflecting on his quitting friends, he said,

“They just didn’t want it even a little bit… I’m not like that; I do want it.”

I gently challenged him to want it with all his heart. The breakthrough came when Dane declared his own dream out loud:

“I want to carry Malaysia’s name to the world stage.”

He said this with genuine conviction. I could see that his perspective had changed—it was now his dream, not mine. This shift from compliance to internal conviction signals the move toward autonomous motivation, shown to enhance persistence and well-being in athletes (Banack et al., 2011).

That evening I wrote in my journal that I felt both joy and anxiety:

joy that Dane had “finally said it’s his dream,”

and concern because I knew I now needed to step back. In the next training session, I consciously ceded control. Instead of dictating Dane’s warm-up and accessory lifts, I asked him to plan the warm-up himself and choose which additional exercises to do. Dane structured an excellent warm-up (essentially implementing what he had learned on his own) and identified that his lower back was a weakness to address. This was a subtle but significant shift—Dane began to trust his own judgment. Over subsequent weeks, he started to set new personal goals (aiming for regional and Asian championships) and began monitoring aspects like nutrition and recovery without being prompted.

This transition aligns with self-determination theory: as Dane’s autonomy increased, so did his intrinsic motivation. He was no longer lifting for me; he was lifting for himself and what he believed in. (Hollembeak & Amorose, 2005). A telling quote from Dane at this time captures the change:

“I still feel like I am failing sometimes… I have a lot of homework… I keep on pushing… I do feel like mentally breaking down sometimes, but I keep on going… I want to carry Malaysia’s name… This is my dream and ambition.”

In this statement we hear his internal struggle and resolve. He acknowledges stress and weakness, but frames his decision to “keep on pushing” as his own choice, driven by his dream. Dane was now articulating a personal reason to be gritty—the essence of inside-out grit.

May and Hailey: Inside-Out from the Start

In contrast to Dane and Chan, May and Hailey largely exemplified the inside-out pathway from the beginning. They joined with strong internal passion for the sport and needed almost no external prodding (Sullivan, 2019). For instance, in one training session I mentioned, “If you keep going in this direction, you both would definitely break national records in January.” I only had to say it once—they immediately asked for the exact record figures and then “kept their heads in the training,” mentally rehearsing to achieve those targets. Unlike the boys, the girls didn’t need frequent reminders or threats of missing goals—they enjoyed the training process itself. As I noted in my journal, “the competition and records were all secondary to them; they enjoyed being in the gym and that was satisfying already”. Their intrinsic enjoyment is a hallmark of inside-out grit: their passion made perseverance almost automatic.

Of course, they still faced challenges. When Hailey encountered a mishap in competition (a disqualified lift on a technicality), we deliberately withheld the bad news until after her final attempt to protect her confidence. Hailey stayed focused and succeeded on her next attempt, then calmly expressed gratitude upon learning of the earlier failure. As observed, she had “confidence and courage to continue to pursue the national record without any fear”—a resilience and mental toughness clearly coming from within. (Lozano-Jiménez et al., 2021) Similarly, May handled tough training with a quiet determination that suggested a growth mindset.

Coaching May and Hailey required mostly support and refinement rather than driving motivation. They responded best to encouragement and collaborative problem-solving rather than authoritative commands. I often thought that:

“a coach can afford to step back a bit when an athlete is fully invested”.

Indeed, I gave them autonomy and voice in their training, and they thrived. They even self-corrected before I could point out errors, and they set ambitious goals on their own. This aligns with the self-determination perspective: with high autonomy and competence, their intrinsic motivation remained strong.

Chan’s Inside-Out Shift

Chan’s case was interesting because he started with less obvious internal passion and more anxiety than the girls. But by the end of the season, he had undergone a significant shift. Through consistent reinforcement of positive self-talk and gradually increased responsibility, Chan began to show initiative. He started, for instance, to research nutrition on his own and proudly shared a diet plan he created. He even volunteered to assist me in coaching newcomers after his competition. He said he “wanted to help others find their confidence like he did”. That statement shows Chan had internalized what he gained enough to want to give back. His motivation locus had moved inward: he was no longer training just because a coach told him or his parents watched; he had personal reasons (overcoming self-doubt and helping others).

At one point, Chan recorded in his journal a self-challenge:

“I hope to hit a 100-kg bench and a 160-kg squat… I don’t want to go down without a fight… even if I lose, I want to at least make it close”.

This indicates a growing internal determination to set and meet his own standards, an emerging self-determined motivation, which SDT links to grit and performance sustainability (Hollembeak & Amorose, 2005). It’s worth noting that the inside-out transition for all athletes was facilitated by gradually increasing their autonomy and decision-making. For each athlete we tailored this process through SDT-driven coaching model according to Review of SDT (2023): with Dane, we handed over training planning piece by piece; with Chan, we provided emotional tools and choices gradually; with the girls, we mostly got out of their way while continuing to provide support.

I would frequently ask Hailey and May reflective questions (“What went well and what will you do differently next time?”) to reinforce self-coaching. With Dane and Chan, I started asking, (“How would you adjust the plan if I weren’t here?”) Initially, Dane was unsure, but over time he began to tentatively offer ideas. He gradually learned to reflect on his performance and make choices—core skills of inside-out grit.

3.3. Dual Pathways in Perspective: Integrating Outside-In and Inside-Out

Our case comparisons suggest that outside-in and inside-out are useful conceptual pathways but deeply interconnected in practice. We observed a general progression from outside-in motivation toward inside-out over time, yet personal and contextual factors shaped each athlete’s journey. For example, socioeconomic and family context influenced the balance: Dane (low SES, little prior support) responded strongly to outside-in structure, whereas Chan (high SES, over-supportive parents) had to peel back external dependence to find his own drive. These patterns align with Harwood et al. (2024), who emphasize that athlete development is deeply context-dependent, influenced by support structures, cultural norms, and personal background. The girls (May, Hailey), by contrast, entered with substantial inside-out drive from the start, which the coach’s support further nourished. (Vella et al., 2013).

We also identified a triadic mechanism that underpinned grit development:

A strong coach–athlete relationship (providing emotional safety and accountability).

Effective coaching strategies (goal-setting, feedback, mental skills).

Structured adversity. (intentional challenging but manageable goals).

Early in the process, these functioned as outside-in supports: the relationship offered emotional backing and accountability; the coach’s strategies provided guidance and tools; and adversity introduced challenges to overcome. The successful interplay of these elements resulted in internal outcomes: the athletes gained confidence, improved skills, and an intrinsic resolve that could sustain them beyond the structured environment. In practical terms, this reflects a known “challenge-and-support” model of youth development, where progress occurs when challenges are paired with support (Vella et al., 2011).

Ultimately, all four athletes experienced growth beyond physical outcomes. They showed increases in the “5 Cs” of youth development: Competence, Confidence, Character, Connection, and Contribution alongside their enhanced grit. (Haritha & Bilquis, 2022). For example, Dane’s evolving confidence and leadership, Chan’s emerging empathy and initiative with peers, and Hailey’s and May’s growing self-efficacy (including working to inspire other girls) all illustrate holistic development.

When Dane said,

“This is my dream and ambition,”

He was articulating a broader purpose beyond his lifts. He had indeed “carried” this goal beyond the gym. These integrative themes illustrate how outside-in and inside-out pathways coalesce in practice.

3.4. Conceptual Framework and Key Outcomes

The findings reveal two distinct but occasionally intersecting pathways through which grit was cultivated among youth powerlifters—namely, the Outside-In and Inside-Out trajectories. As outlined in

Table 1, each athlete’s developmental path was shaped by their socioeconomic background, motivational starting point, and the nature of coach interventions. Those with lower autonomy or fewer structural advantages (e.g., Dane, Chan) initially relied on coach-driven discipline, progressing through adversity via scaffolded support and eventually internalizing grit. In contrast, athletes such as Hailey and May exhibited more self-determined motivations from the outset, with coaching focused on refinement rather than direction.

Figure 1 presents the Dual Pathway Model of Grit Development in Youth Coaching. Rooted in the coach–athlete relationship, this framework illustrates two primary developmental trajectories: Outside-In Grit, which is coach-driven and shaped by structured adversity and external motivation, and Inside-Out Grit, which is youth-driven and fueled by intrinsic passion and self-motivation. Youth who begin with external compliance and behavior change often experience a shift toward self-regulated effort and identity ownership, marking the transition from Outside-In to Inside-Out grit. This internalization process is depicted by the dashed arrow labeled “Shift to intrinsic drive.” Ultimately, both pathways converge in the “Dual Pathway Integration” phase, culminating in Internalised Grit—a sustained, autonomous perseverance that reflects a mature developmental outcome. This framework integrates findings from this study and aligns with both Self-Determination Theory and Positive Youth Development principles.

In closing this Results section, we note that each youth not only developed deeper grit but turned it outward in positive ways. Dane became an independent athlete and even aspired to mentor others from his hometown. Chan overcame personal barriers and sought to help peers build confidence. May and Hailey challenged gender stereotypes and encouraged other girls to try strength sports. When youth develop grit through the coming together of external support and internal commitment, they often “turn outward and uplift others,” as the final coach note observed. This ripple effect hints at a broader social value of cultivating grit—a phenomenon echoed in recent findings on Positive Youth Development’s ripple effects (Vierimaa et al., 2018).

4. Discussion

Our findings contribute to a reconceptualization of grit not as a fixed individual trait, but as a dynamic capacity nurtured through relationships and context. In particular, our relational-developmental model shows how external guidance and structured experiences can teach grit, which the youth then internalize over time (Major, 2013). This complements Duckworth’s emphasis on individual passion by highlighting coaches and environments as “grit catalysts” that can instill perseverance even in initially unmotivated youth. For example, Robertson-Kraft and Duckworth (2014) found that supportive conditions in schools were linked to greater persistence in challenging settings; our study provides a mechanism for this effect in sport, showing how mentors can actively transfer a gritty mindset.

This perspective aligns with recent literature suggesting grit is malleable. Park and Jun (2024) reported that parental or coach support during challenges can develop grit in adolescents, and Davidson and Foster (2024) argue that strong relationships combined with difficult experiences foster perseverance. Our qualitative evidence provides a narrative account of how these factors operate together: coaches and mentors can effectively transfer a “gritty” attitude to youth through scaffolding and structured adversity.

One useful theoretical lens is Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD). In that framework, the coach initially carries much of the motivational load, enabling the youth to perform beyond their current capability. Over time, as the youth’s perseverance grows, the coach gradually removes this scaffold—a process mirrored in our cases as athletes progressed from heavily supported beginnings to independent self-drive. This suggests grit development can be viewed as skill acquisition: the coach temporarily provides the drive beyond the athlete’s unaided level, then withdraws support as the athlete internalizes the drive (O’Heaney, 2018).

Our observations also resonate with transformational coaching theory. A transformational coach inspires and motivates athletes beyond immediate goals, often by providing vision, intellectual stimulation, and personalized mentorship. In Dane’s case, the coach’s role embodied transformational leadership: he offered a vision (Dane could be a champion), provided challenges, and gave individualized consideration (Toni et al., 2025). The result was a kind of “grit contagion,” where the coach’s own drive transferred to the athlete. In a way, the coach was performing a “grit transfer” of values and habits, which the youth then needed to undergo a “grit transformation” by internalizing those inputs. This aligns with Duckworth’s own later discussions of teachers cultivating grit, but highlights that the final step is to let students take ownership of that grit.

Our cases further illustrate the intersection of grit with positive youth development (PYD). As grit grew in these athletes, we also saw gains in the 5 Cs (competence, confidence, character, connection, caring). For instance, as Dane’s perseverance increased, so did his confidence and character (taking on leadership roles and responsibility in school) and our coach–athlete bond deepened his sense of connection. In line with Holt et al. (2017), who found that PYD conditions foster grit, we saw grit both resulting from and contributing to positive development (Haritha & Bilquis, 2022).

Importantly, fostering grit also built resilience in our athletes. The outside-in phase created a safety net: failures and setbacks were reframed with coach support. For example, a missed lift was treated as “data” for improvement and was met with encouragement rather than punishment. Over time, athletes adopted this resilient mindset themselves. Hailey’s calm response to a near-disqualification, and the girls’ willingness to train through discomfort, both reflect an internalized coping skill set. In this way, grit (sustained effort) and resilience (bouncing back) grew together via adversity plus support. Coaches should therefore address both together, teaching youths that persistence is worthwhile and that setbacks are overcomeable with effort and support (Major, 2013).

Finally, our work reinforces the foundational role of the coach–athlete relationship in youth development. We saw how closeness and trust were leveraged to instill grit. The emotional bond and mutual commitment anchored the athletes in the program and gave them confidence to strive. This reflects Jowett’s (2007) model of coach–athlete closeness and commitment. Our findings underscore that coaches can be critical social capital for youth: by caring deeply and holding high expectations, they can support positive change in the athlete through genuine relational investment (Toni et al., 2025).

Practical Implications

From a practical standpoint, our study offers a model for coaches and youth programs. To cultivate gritty, resilient youth, mentors should actively provide initial support and structure, then gradually transfer responsibility.

In practice, this means:

Provide Grit: At the outset, set clear schedules, goals, and challenges, and serve as a steadfast source of belief. For example, we entered beginners in age-appropriate competitions to create structured adversity under supervision. Teach mental skills like positive self-talk and goal setting so that youth learn to endure hardship (Camiré et al., 2011).

Develop Grit: As athletes engage, continue supporting them but also encourage their input. Provide feedback and allow athletes to make some decisions. Invite them to set personal targets and reflect on progress (as we did with Hailey and May by asking, “What can you improve next time?”). Maintain mentorship but cede some control. (Hwang & Nam, 2021).

Transfer Ownership: Finally, step back and let the youth steer their own journey. Gradually hand over tasks like planning workouts, tracking nutrition, or leading warm-ups (as with Dane and Chan). Continue to encourage and guide, but resist over-coaching. This nurtures the athlete’s autonomy and intrinsic motivation. (Santos & Martinek, 2018)

The timing of this transition is crucial. For example, we initially took a structured approach with all newcomers, but we quickly realized that Hailey and May could handle more independence sooner, whereas Dane and Chan benefited from extended guidance. Coaches should continually assess each athlete’s drive and readiness for autonomy rather than applying a one-size-fits-all approach. This phased approach is much like educational scaffolding aligns with best practices in teaching and coaching.

Consistent with recent arguments, we also caution against treating grit as a fixed trait to screen for. Instead, programs should intentionally cultivate grit by focusing on supportive relationships and positive youth development practices. In other words, rather than selecting only “gritty” youth, coaches and educators can foster grit in many youths through intentional design of their environments and mentorship.

Summary

In summary, the narratives of Dane, Chan, Hailey, and May illustrate that individual differences (background, personality, gender) shape how grit pathways unfold, but the developmental pattern holds: when properly supported, youth can transform their initial motivations into enduring grit. All four demonstrated remarkable growth in both perseverance and passion over the 20-week period. Each overcame initial hurdles: Dane overcame apathy and became passionately ambitious; Chan overcame self-doubt and found motivation; Hailey and May confirmed that intrinsic zeal, when supported, leads to achievement and leadership.

One of the most compelling illustrations of this shift is embodied in Dane’s words:

“I want to carry Malaysia’s name into the international arena and make Malaysia proud. This is my dream and ambition.”

This statement—from a boy who once “never imagined a life beyond Angsana” epitomizes the move from outside-in to inside-out.

We acknowledge that our analytic autoethnographic approach, while offering deep insight, has limitations (e.g., potential researcher bias). Future research could incorporate independent interviews or quantitative measures to see if athletes articulate their development similarly. Nevertheless, the consistency of multiple data sources, member checks, and colleague reviews supports the credibility of our findings.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that grit in youth sport is not solely an internal trait to be discovered, but a quality that can be actively developed through the dynamic interplay of external guidance and internal growth (Major, 2013). The Outside-In and Inside-Out dual pathways provide a framework for understanding how passion and perseverance co-evolve. We introduced these concepts through a detailed autoethnographic case study, finding that the pathways often operate sequentially. In the outside-in phase, athletes relied on external discipline, vision, and encouragement; in the inside-out phase, they cultivated personal commitment and autonomy (Buenconsejo et al., 2024). For example, Dane initially trained for his coach’s goals and later pursued his own dream, while May and Hailey started with strong intrinsic motivation and further flourished under guidance.

Our findings challenge the original portrayal of grit as an individual disposition. We show that grit can be “grown” via relational scaffolding. A caring coach–athlete relationship incubated grit: training sessions and setbacks were reframed as lessons in perseverance. Grit, in this view, is context-sensitive and emerges from social interactions over time.

In practice, coaches and educators can adopt a phased approach: first provide grit (structured challenges and strong support) and then transfer ownership to the youth (gradually increasing autonomy and encouraging their own goals). This approach aligns with scaffolding and gradual-release methods in teaching. If consistently applied, it not only leads to high performance in sport but also contributes to holistic youth development (Nothnagle & Knoester, 2022).

Ultimately, grit in youth is best understood as the outcome of a developmental journey. One that often begins outside-in and ultimately flourishes inside-out. Coaches, mentors, parents, and educators all play vital roles in igniting and guiding this journey. They provide the sparks and the fuel, creating a safe environment in which the flame of grit can catch fire and burn on its own. Each athlete’s transformation shows that perseverance and passion can indeed be cultivated, carried outward, and become a lasting part of a young person’s life.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participant(s) and parents (for minors) involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the participant(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement:

The data supporting this study consists of personal autoethnographic reflections, coaching journals, and interview transcripts involving identifiable youth participants sometimes being vulnerable and sensitive. In line with ethical considerations and participant confidentiality, these data are not publicly available. De-identified excerpts used in the article are included within the text to illustrate key findings. Further inquiries may be directed to the corresponding author, subject to ethical review and approval.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5Cs |

Competence, Confidence, Character, Connection, and Contribution |

| PYD |

Positive Youth Development |

| SDT |

Self-Determination Theory |

| SES |

Socioeconomic Status |

References

- Anderson, L. Analytical autoethnography. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 2006, 35(4), 373–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arthur, C. A.; Hardy, L.; Woodman, T. Realising the Olympic dream: Vision, support and challenge. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 2015, 10(2-3), 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Banack, H. R.; Sabiston, C. M.; Bloom, G. A. Coach autonomy support, basic need satisfaction, and intrinsic motivation of Paralympic athletes. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 2011, 82(4), 722–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, L.; Ross-Stewart, L.; Meyer, B. B. The relationship between athlete perceptions of coaching leadership behaviors and athlete grit. International Journal of Exercise Science 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Buenconsejo, J. U.; Datu, J. A. D.; Liu, D. Does grit predict thriving or is it the other way around? A latent cross-lagged panel model on the triarchic model of grit and the 5Cs of positive youth development. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2024, 34(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camiré, M.; Forneris, T.; Trudel, P.; Bernard, D. Strategies for helping coaches facilitate positive youth development through sport. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action 2011, 2(2), 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M. J. An autoethnographic analysis of sports identity change. Sport in Society 2016, 19(6), 767–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D. L.; Jørgensen, H.; Ferguson, L. J.; Gyurcsik, N. C.; Briere, J. L.; Kowalski, K. C. Constructing a grounded theory of grit in sport: Understanding the development and outcomes of long-term passion and perseverance in competitive athletes. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 2025, 17(2), 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, W.; Foster, C. [Details not provided—presumed qualitative grit and adolescent support research]. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L.; Ryan, R. M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry 2000, 11(4), 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duckworth, A. Grit: The power of passion and perseverance; New York, NY; Scribner, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, A. L.; Peterson, C.; Matthews, M. D.; Kelly, D. R. Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2007, 92(6), 1087–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erickson, K.; Côté, J.; Hollenstein, T.; Deakin, J. Examining coach–athlete interactions using state space grids: An observational analysis in competitive youth sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2011, 12(6), 645–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gearity, B. Autoethnography. In Handbook of Research in Sports Coaching; 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt, B. Reflections on talent development: Roles, philosophies and conflicts. Doctoral dissertation, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Haritha, Y.; Bilquis, B. Positive youth development: Levels of positivity in youth development. Asian Journal of Agricultural Extension, Economics & Sociology 2022, 40(12). Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/positive-youth-development-levels-of-positivity-in-youth-3pj4pf41.

- Harwood, C.; Johnston, J.; Wachsmuth, S. Positive youth development and talent development. In Routledge Handbook of Youth Sport; 2024; Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/positive-youth-development-and-talent-development-3a1cic7pfz.

- Hollembeak, J.; Amorose, A. J. Perceived coaching behaviors and college athletes’ intrinsic motivation: A test of Self-Determination Theory. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 2005, 17(1), 20–36. Available online: https://scispace.com/papers/perceived-coaching-behaviors-and-college-athletes-intrinsic-kutn0wzzvr. [CrossRef]

- Holt, N. L. (Ed.) Positive youth development through sport; London; Routledge, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Holt, N. L.; Neely, K. C.; Slater, L. G.; Camiré, M.; Côté, J.; Fraser-Thomas, J.; MacDonald, D. J.; Strachan, L.; Tamminen, K. A. A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2017, 10(1), 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowett, S.; Cockerill, I. M. Olympic medallists’ perspective of the athlete–coach relationship. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2003, 4(4), 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.-H.; Kwon, S.-H. The impact of physical self-concept and mindset on the grit of youth participants in sports activities. Korean Journal of Security Convergence Management 2023, 12(12), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, R. W. Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist 2000, 55(1), 170–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longakit, J.; Toring-Aque, L.; Aque, F. M.; Sayson, M.; Lobo, J. The role of coach-athlete relationship on motivation and sports engagement. Physical Education of Students 2024, 28(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Jiménez, J. E.; Huéscar, E.; Moreno-Murcia, J. A. From autonomy support and grit to satisfaction with life through self-determined motivation and group cohesion. Frontiers in Psychology 11 2021, 579492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mageau, G. A.; Vallerand, R. J. The coach–athlete relationship: A motivational model. Journal of Sports Sciences 2003, 21(11), 883–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, C. Youth Mentoring Partnership’s Friend Fitness Program: Theoretical foundations and promising preliminary findings. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist 2001, 56(3), 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nothnagle, E. A.; Knoester, C. Sport participation and the development of grit. Leisure Sciences 2022, 44(4), 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Heaney, E. Developing grit: A case study of a summer camp which empowers students with learning disabilities through the use of social-emotional learning. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Jun, M. Details not provided—presumed study on support and grit in adolescents. 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rahayuni, K. Autoethnography as writing representation in cultural sport psychology. KnE Social Sciences 2022, 7(19), 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J. B. Beyond the playing field: Coaches as social capital for inner-city adolescent African-American males. Journal of African American Studies 2012, 16(2), 171–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson-Kraft, C.; Duckworth, A. L. True grit: Trait-level perseverance and passion for long-term goals predicts effectiveness and retention among novice teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology 2014, 106(3), 730–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandbakk, Ø.; Hendriksen, I. J.; Sperlich, B. The rise and development of grit in sports. Current Opinion in Psychology 44 2022, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, F.; Martinek, T. J. Facilitating positive youth development through competitive youth sport: Opportunities and strategies. Journal of Sport Behavior 2018, 41(4), 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, M.; Hilton, N. K. Resilience in sport: Developments in research and practice. International Journal of Sport Psychology 2020, 51(2), 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sumarsono, R. N.; Setiawan, E.; Ryanto, A. K. Y.; Mahardhika, D. B.; Németh, Z. Investigate relationship between grit, coach leadership style with sports motivation and athlete satisfaction while training after COVID-19. Studia Sportiva 2023, 17(1), 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G. S. SDT in Athletics. In The Psychology of Coaching and Mentoring; Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Toni, M.; Mehta, A. K.; Mohit, G. S.; Chandel, P. S.; Kamalakkannan, M. K.; Selvakumar, P. Mentoring and coaching in staff development. Advances in Higher Education and Professional Development 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Vella, S. A.; Oades, L. G.; Crowe, T. P. The role of the coach in facilitating positive youth development: Moving from theory to practice. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 2011, 23(1), 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, S. A.; Oades, L. G.; Crowe, T. P. The relationship between coach leadership, the coach–athlete relationship, team success, and positive developmental experiences of adolescent soccer players. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 2013, 18(5), 549–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierimaa, M.; Bruner, M. W.; Côté, J. Positive youth development and observed athlete behavior in recreational sport. PLOS ONE 2018, 13(1), e0191936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weight, E. A.; Haroldson, J. M.; Harry, M.; Rudd, E. Adversity and resiliency: Athlete experiences within U.S. college sport. Journal of Intercollegiate Sport 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Cao, M.; Ma, Y. Influencing factors of women’s sports participation based on self-determination theory: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 17 2024, 1301–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulham, Z.; Candra, O.; Hermanto, H.; Riyanto, P. Building confidence and well-being: The power of coach communication and personal connections in college basketball. Asian Journal of Engineering Social and Health 2024, 3(12), 2701–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).