1. Introduction

Cancer is a disease characterized by disrupted intercellular communication, where cells employ various mechanisms to manipulate their surrounding environment for survival, thereby promoting growth and metastasis [

1,

2].

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes and microvesicles, as well as non-vesicle nanoparticles such as exomeres and supermeres, have emerged as key mediators of this aberrant communication [

3,

4]. These entities transport a diverse array of biomolecules, including lipids, proteins, glycans, and nucleic acids, into other cells, which influence various aspects of cancer progression, such as proliferation, angiogenesis, immune evasion, and metastasis [

5,

6].

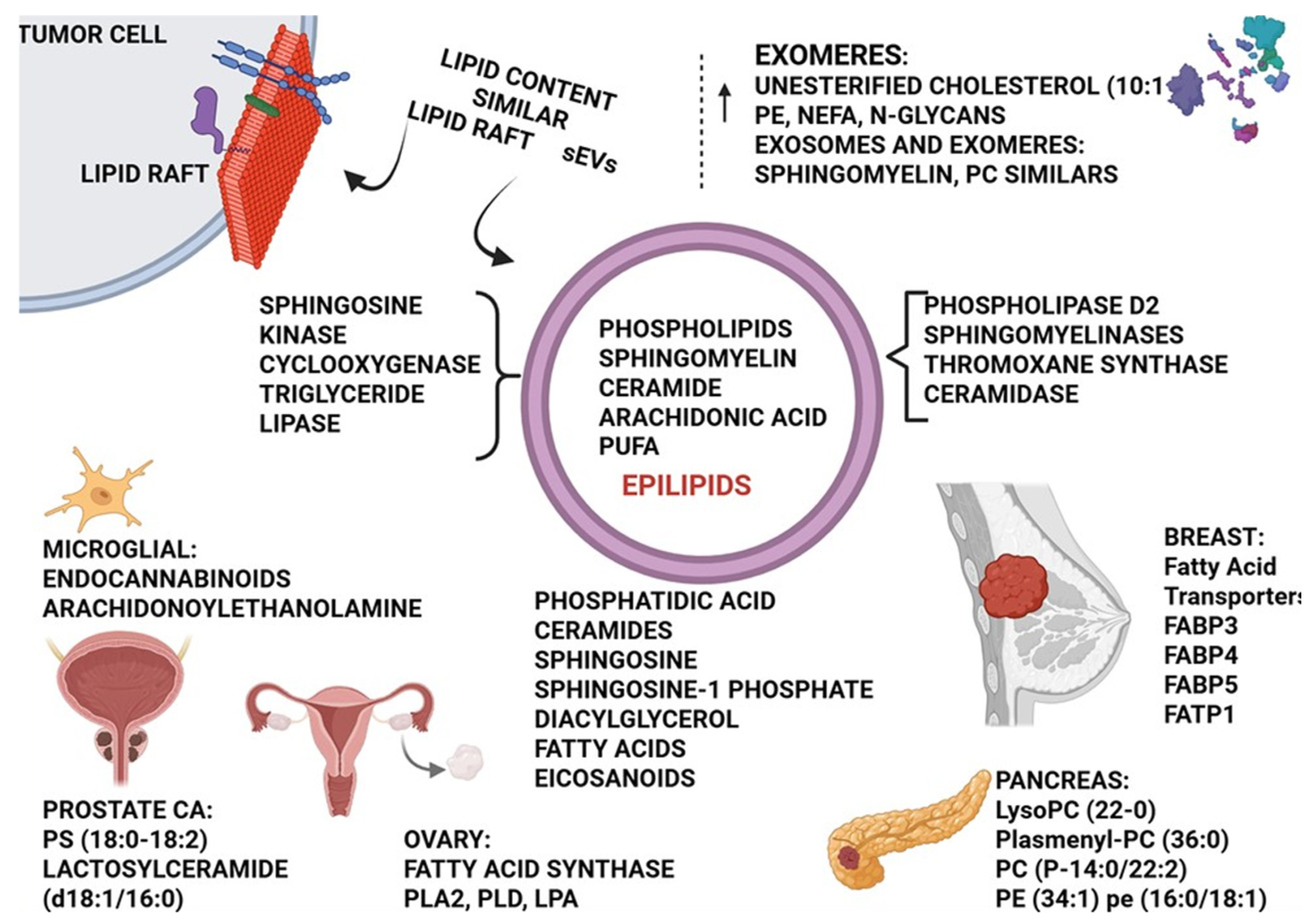

Reports indicate that lipid metabolism and lipid-mediated cell signaling are altered in cancer cells, which ultimately regulate the generation and release of EVs and lipid nanoparticles. For example, the lipids of EVs in pancreatic cancer patients are derived from the serum, including lyso-PC (22:0), plasmenyl-PC (36:0), and PC (P-14:0/22:2). These lipids are also associated with regulating tumor stage, size, and the number of lymphocytes [

7,

8].

These lipid-rich entities can modulate the behavior of recipient cells, affecting signaling pathways, metabolic processes, and gene expression. EVs from highly metastatic breast cancer accumulated unsaturated diacylglycerols (DGs). The EVs enriched with DGs can activate the protein kinase D signaling pathway in endothelial cells, thereby stimulating angiogenesis [

9].

Lipidomic profiling of EVs derived from non-malignant prostate and prostate cancer cell lines reported fatty acids, glycerolipids, and prenyl lipids, which are highly abundant in EVs from non-tumorigenic cells. In contrast, sterol lipids, sphingolipids, and glycerophospholipids are highly abundant in EVs from tumorigenic or metastatic cells [

10].

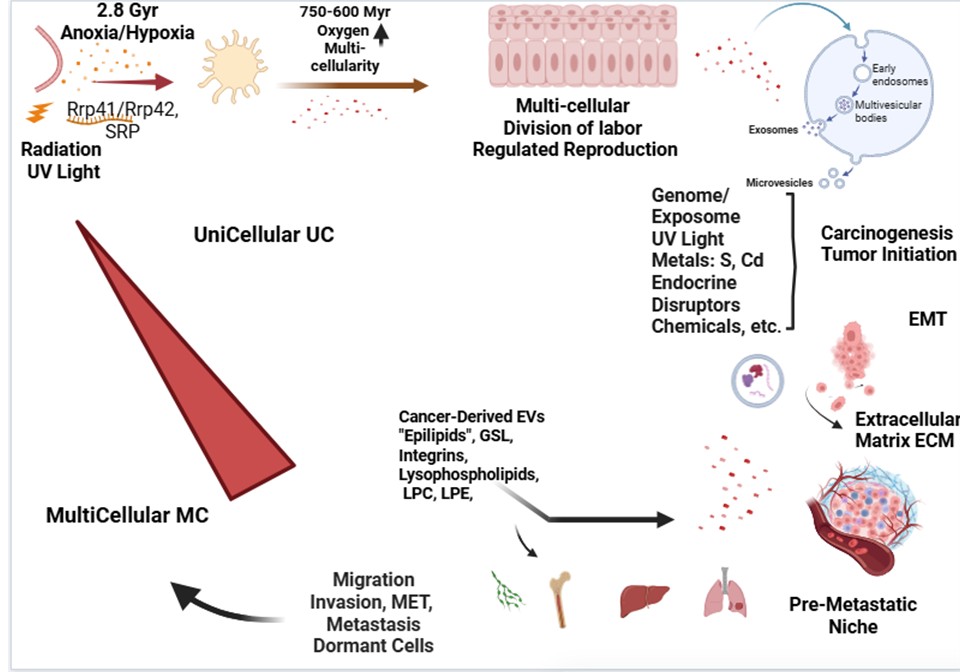

The atavistic or ancestral theory of cancer posits that cancer cells revert to more primitive, unicellular-like states, enabling them to survive and proliferate under challenging conditions [

11,

12,

13]. In this context, the exchange of lipids and other biomolecules via EVs and nanoparticles is evident as a mechanism by which cancer cells regain ancestral traits, facilitating their adaptation and metastasis.

2. The Evolutionary Context of EVs and Lipid Signaling

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) and lipid signaling pathways have ancient origins, predating the evolution of multicellular organisms. Prokaryotic cells utilize membrane vesicles for communication and horizontal gene transfer, while lipid-based signaling is essential for coordinating cellular responses to environmental cues. In eukaryotes, these mechanisms have been adapted and refined to facilitate complex cell-cell interactions and maintain tissue homeostasis. Cancer cells exploit these evolutionarily conserved pathways to promote their survival and spreading, effectively rewiring intercellular communication networks to their advantage. Extant unicellular holozoans share genes homologous to those critical for multicellularity-related functions in animals, primarily involved in cell adhesion, signaling pathways, and transcriptional regulation. These include Notch, Delta, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK), and homologs of the Toll-like receptor genes. Spatial signaling pathways, such as Hedgehog, WNT, transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), JAK–STAT, and Notch, are highly conserved [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Lipid biology is likely a key driver of the Cambrian Explosion, because it alone provides for compartmentalization and specialization within cells [

20].

The lipid composition of EVs and nanoparticles varies depending on the cell of origin, the surrounding microenvironment, and the specific vesicle type [

21]. Cancer-derived EVs and nanoparticles often exhibit distinct lipid profiles compared to those from normal cells, reflecting the altered metabolic state of cancer cells. In the metastatic prostate cancer cell line PC-3, exosomes are highly enriched in glycosphingolipids, sphingomyelin, cholesterol, and phosphatidylserine. Approximately 8.4-fold enrichment of lipids per mg of protein in exosomes was reported [

22,

23]. Key lipid species enriched in cancer-derived EVs and nanoparticles are:

2.1. Cholesterol

Elevated cholesterol levels in EVs can promote membrane rigidity, increase EV stability, and enhance their uptake by recipient cells. The lipid composition of EV membranes depends on the process of EV biogenesis. The recruitment of cytosolic lipids, including triacylglycerols and cholesterol esters, into exosomal membranes accompanies multivesicular bodies (MVBs), which serve as precursors of exosomes. Enrichment with cholesterol and sphingolipids makes them similar to the detergent-resistant domains of lipid rafts [

24].

2.2. Sphingolipids

Sphingolipids, such as ceramides and sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), are involved in various cellular processes, including apoptosis, proliferation, and inflammation. Sphingomyelins hydrolysis to ceramides during exosome biogenesis is enhanced in cancer patients. Cancer-derived EVs enriched in sphingolipids can modulate these processes in recipient cells, contributing to tumor progression [

25,

26].

2.3. Phospholipids

Phospholipids, such as phosphatidylserine (PS) and phosphatidic acid (PA), play critical roles in cell signaling and membrane dynamics. Cancer-derived EVs can alter phospholipid composition in recipient cells, affecting signaling pathways and promoting cell survival [

27,

28].

2.4. Glycerolipids

Increased levels of diacylglycerols (DGs) in cancer-derived EVs can activate protein kinase D (PKD) signaling in endothelial cells, stimulating angiogenesis. Dysregulation in the activity or abundance of DAG effectors has been widely associated with tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis. DAG is also a key orchestrator of T cell function and thus plays a significant role in tumor immune surveillance. Protein Kinase D1 (PKD1) modulates the functions of β-catenin to suppress colon cancer growth. Analysis of normal and colon cancer tissues reveals downregulation of PKD1 expression in advanced stages of colon cancer. In highly invasive breast cancer, the loss of PKD1 is thought to promote invasion and metastasis, while PKD2 and upregulated PKD3 are positive regulators of proliferation, chemoresistance, and metastasis [

29,

30,

31].

2.5. Fatty Acids

Small extracellular vesicles (exosomes) primarily contain unesterified (free) cholesterol, with a ratio of approximately 10:1 unesterified/esterified cholesterol. In contrast, exomeres (also referred to as distinct nanoparticles DNPs) are enriched with esterified cholesterol (4:1 esterified/unesterified) [

32].

3. Mechanisms of Lipid-Mediated Communications

Lipid-mediated communication via EVs and nanoparticles occurs through several mechanisms, as stated below:

3.1. Direct Transfer of Lipids

EVs and nanoparticles can deliver lipids directly to recipient cells, altering their membrane composition and affecting lipid-dependent signaling pathways. EVs are taken up by the recipient cells either by direct fusion of EVs’ membrane with the plasma membrane of recipient cells or by a variety of endocytic pathways, including clathrin-dependent endocytosis, and clathrin-independent pathways such as caveolin-mediated uptake, macropinocytosis, phagocytosis, and lipid raft-mediated internalization [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38].

3.2. Activation of Lipid Receptors

Lipids within EVs and nanoparticles can bind to and activate lipid receptors on recipient cells, triggering intracellular signaling cascades. Exosomes derived from adipocytes supply two enzymes of the β-oxidation pathway to melanoma cells, namely enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECHA) and hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase (HCDH). Adipocyte exosome internalization into melanoma cells increased fatty acid oxidation and promoted melanoma cell migration. Adipocyte EVs remodel Fatty Acid FA metabolism, resulting in FAO, which fuels cell invasion. EV-associated FABP5 is involved in prostate cancer aggressiveness. Mitochondrial transfer via EVs plays an important role in metabolic switching, facilitating cell division and tumor growth in glioblastoma multiforme and breast cancer, among others. [

39,

40,

41,

42].

3.3. Epilipids

Oxidative modifications of lipids are a part of regulatory and adaptive events, highly specific for cell types, tissues, and conditions. The equilibrium between lipid chemical diversity required for dynamic lipid remodeling, and response and adaptability of cellular membranes, pre-existing lipids can be modified through oxidation, nitration, sulphation, and halogenation processes. Oxidized lipids regulate fundamental events such as innate immune responses, ferroptotic cell death, inflammatory response, and metabolic pathways. Oxidized fatty acyl chains projects away from the surface of the membrane into aqueous medium (whiskers). These “whiskers” mark the membrane for cell recognition and, either induce apoptosis, or elicit membrane recycling. However, analytical and functional studies remain challenging. [

8,

43,

44,

45].

4. Lipid-Mediated Communication in Cancer Progression and Metastasis

Lipid-medi ated communication via EVs and nanoparticles plays a critical role in various aspects of cancer progression and metastasis, influencing cancer cell homing, organotropism, and dormancy. The metastatic process is preceded by EVs produced early, and accordingly, with specific integrins related to each organ target.

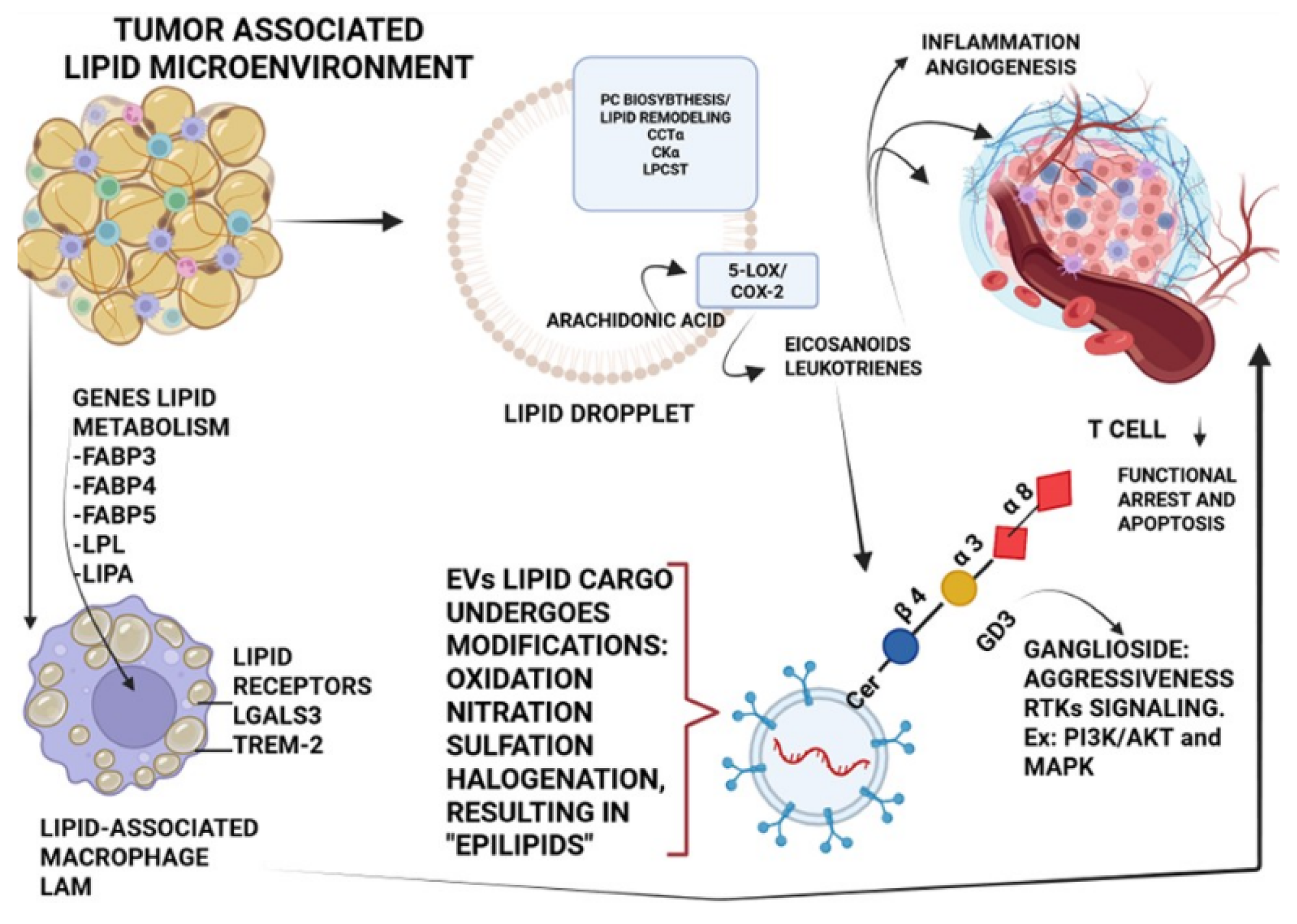

4.1. Tumor Microenvironment Modulation

Lipid constituents of MVs provide an additional mechanism for tumors to create an immune-privileged microenvironment. Glycosphingolipids (GSLs), one subtype of glycolipids, are also present in sEVs. EVs secreted from gangliosides GD3/GD2-positive gliomas enhance the malignant properties of glioma cells, leading to total aggravation of heterogeneous cancer tissues, and in the regulation of tumor microenvironments. [

46,

47]. A prominent feature of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) is that lipids within EVs can also influence the recruitment and polarization of macrophages toward the M2 phenotype, which is characterized by increased lipid synthesis, fatty acid oxidation, and mitochondrial respiration of immune cells, creating an immunosuppressive environment that favors tumor growth and metastasis. Repolarization of the pro-tumor M2 phenotype to the antitumor M1 phenotype can be achieved by inhibiting liver X receptors (LXRs) and ATP-binding cassette subfamily G member 1 (ABCG1). Liver X receptors (LXRs), binding to LXR response elements (LXREs) within the promoter of responsive genes, like ABCA1 (ATP-binding cassette A1), LXR/ABCA1 is responsible for cholesterol homeostasis and M2 polarization. As a result, TAM2 reprogramming reduces TGF-β secretion, thereby suppressing TGF-β-driven EMT [

48,

49].

Figure 1.

Tumor-Associated Lipid Microenvironment. Epilipids: Lipids can undergo a range of enzymatic and nonenzymatic reactions (e.g., oxidation, nitration, sulphation, and halogenation). Influence their biogenesis and cargo, as well as their interactions with target cells. PC: Phosphatidyl Choline. CCTα: phosphate cytidylyltransferase 1 choline alpha. CKα: choline kinase α. LPCAT: Lysophosphatidylcholine Acyltransferase. 5-LOX: 5-lipoxygenase. COX-2: Cyclooxygenase-2. FABP 3/4/5: Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 3/4/5. LPL: Lipoprotein lipase. LGALS3: lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble 3. RTKs: Receptors Tyrosine Kinases. PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase. AKT: Protein Kinase B (PKB). MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinases.

Adapted from Fyfe et al.

(2023, ref. 8). Created in BioRender. Adel, L. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/ixjfoj6.

Figure 1.

Tumor-Associated Lipid Microenvironment. Epilipids: Lipids can undergo a range of enzymatic and nonenzymatic reactions (e.g., oxidation, nitration, sulphation, and halogenation). Influence their biogenesis and cargo, as well as their interactions with target cells. PC: Phosphatidyl Choline. CCTα: phosphate cytidylyltransferase 1 choline alpha. CKα: choline kinase α. LPCAT: Lysophosphatidylcholine Acyltransferase. 5-LOX: 5-lipoxygenase. COX-2: Cyclooxygenase-2. FABP 3/4/5: Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 3/4/5. LPL: Lipoprotein lipase. LGALS3: lectin, galactoside-binding, soluble 3. RTKs: Receptors Tyrosine Kinases. PI3K: Phosphoinositide 3-kinase. AKT: Protein Kinase B (PKB). MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinases.

Adapted from Fyfe et al.

(2023, ref. 8). Created in BioRender. Adel, L. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/ixjfoj6.

4.2. Metastatic Niche Formation and Organotropism

EVs and nanoparticles can deliver lipids to distant organs, preparing the pre-metastatic niche and facilitating the colonization of cancer cells. Critically, the lipid composition of EVs can dictate their tropism for specific organs, contributing to the organ-specific patterns of metastasis observed in different cancers (organotropism). This is achieved through the interaction with integrins such as α

6β

4 and α

6β

1 intended to a pre-metastatic niche in lungs, or exosomal integrins α

6β

4 and α

6β

1 targeting liver [

50].

4.3. Lipid Rafts and Integrins

Lipid rafts, enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids, are hubs for the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) system, and the PI3K/AKT, Fas/CD95, VEGF/VEGFR2, and CD44 signaling pathways. Lipid rafts are involved in the clustering and signaling of integrins. Lipid rafts regulate the clustering of adhesion molecules, such as β1 and β3 integrins, at the leading edge of migrating cells. Integrins on the surface of EVs can mediate their adhesion to specific extracellular matrix components in target organs, thereby directing the homing of cancer cells to these sites. They participate in the formation of pre-metastatic niches (PMNs) and modulate angiogenesis. [

51,

52].

4.4. Signaling Molecules

EVs enriched with lipids can transfer pro-tumorigenic signals and generate a pre-metastatic niche. Isoform secreted PLA2-X (sPLA2-X)-driven hydrolysis of tumor-derived EVs from Epstein-Barr (EBV)-induced B cell lymphoma in humanized mice, increased the production of fatty acids (C20 PUFAs including AA, DPA, and DHA); as well as various lysophospholipid species including lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), lysophosphatidylethanolamine (LPE), their plasmalogen forms (pLPC and pLPE), lysophosphatidylserine (lyso-PS), and lysophosphatidylinositol (LPI) with saturated or monounsaturated fatty acids. This increased vesicle aggregation, produced immunoregulatory lipid mediators, and facilitated EV uptake by recipient macrophages, thereby exacerbating lymphomagenesis. Cell-generated bioactive lipids operate within the local environment and have relatively short half-lives due to their rapid degradation by circulating metabolizing enzymes. EVs can provide protective structures to transport these lipids, allowing for long-range intercellular communication and interaction. This feature should be considered in events as crucial as homing, the pre-metastatic niche, and the dormancy state. With this knowledge, developing new and improved methods to investigate intravesicular lipid cargoes could provide the information needed to clarify the role of EVs as signaling machinery in health and disease [

8,

53,

54].

4.5. Cancer Cell Homing

EVs and nanoparticles facilitate cancer cell homing to secondary sites through different mechanisms, such as:

4.5.1. Chemokine Signaling

EVs can carry chemokines and chemokine receptors, guiding cancer cells towards specific microenvironments. Chemokines comprise a group of approximately 50 small (8–14 kDa) secreted proteins, structurally like cytokines, that regulate cell trafficking. These proteins interact with a family of about 20 seven-transmembrane G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Chemokines are divided into CC-chemokines, the CXC chemokines, C-chemokines, and CX3C-chemokines. In malignancy, chemokines and their receptors play a crucial role in supporting tumor development and metastatic spread. Several complementary mechanisms, such as attracting cancer cells to sites of metastatic spread, mobilization of bone marrow-derived cells (BMDC) from the bone marrow to the blood, followed by their colonization at the tumor site, directing the biological function of these BMDC at the tumor site, and supporting tumor growth through an autocrine pathway. Other roles of chemokines and extracellular vesicles (EVs) include:

Tumor progression: metastasis, proliferation, and cancer cell-induced angiogenesis

Survival and resistance: anti-apoptotic effects on monocytes, cell survival, drug resistance

Signaling pathways: AKT kinase activation, oncogenic signaling

Immune system modulation: immune modulation, macrophage recruitment [

55,

56,

57].

4.5.2. Adhesion Molecules

EVs can express adhesion molecules like selectins and integrins, mediating their attachment to endothelial cells in target organs. Selectins are carbohydrate-binding molecules that bind to sialylated, fucosylated glycan structures and are found on the surfaces of endothelial cells, platelets, and leukocytes. Selectin family: P-selectin is expressed on activated platelets and endothelial cells, L-selectin is present on leukocytes, and E-selectin is expressed on activated endothelial cells. Hypersialylation of cancer cells is primarily the result of overexpression of sialyltransferases (STs). Differentially, humans express twenty different STs in a tissue-specific manner to interact with tumors and selectin ligands, such as exosomes. Functional selectin ligands require post-translational modification of scaffold proteins by glycosyltransferases and sulfotransferases. The minimal recognition motif for all selectins is the sialyl-Lewis

x (sLe

x) and its isomer sialyl-Lewis

a (sLe

a) tetrasaccharide that is synthesized by α1,3-fucosyltransferases IV or VII, α2,3-sialyltransferases, β1,4-galactosyltranferases, and N-acetyl-glucosaminyltransferases. Sialylated integrin β1 on sEV affects its entrance into recipient cells. Sialylation on sEV may alter its biological function and has the potential to serve as a new indicator for bladder cancer diagnosis. [

58,

59,

60,

61]. Adhesion events of cancer cells facilitated by selectins result in activation of integrins, release of chemokines, and are possibly associated with the formation of a permissive metastatic microenvironment. Integrins (ITGs) are important regulatory molecules on exosomes that interact with extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, playing a decisive role in organ tropism. Expression of the integrins αvβ3, αvβ5, α5β1, α6β4, α4β1, and αvβ6 is correlated with disease progression in various types of tumors. Integrins αvβ3, α5β1, and αvβ6 have been found in lung cancer lymph node metastasis. Exosomal α6 and β4 are present in pancreatic and colorectal cancer cells. Fibronectin-integrin-dependent exosome adherence was determined in endothelial cells. Integrin β1 and talin-1 accumulate in recipient cell plasma membranes beneath all sEV subtypes. Paracrine, but not autocrine, sEV binding triggers Ca

2+ mobilization induced by the activation of Src family kinases and phospholipase Cγ. Prostate cancer-derived exosomes have been shown to express β4, vinculin, αvβ6, and αvβ3 [

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70]. Tumor cell homing depends on an adhesive interaction between tumor cells and organ-specific endothelial markers [

71].

5.5.2. Immune Modulation

Tumor-derived EVs are involved in the four stages relevant for the pre-metastatic niche: tumor-derived secreted factors (TDSFs), bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs), suppressive immune cells, and host stromal cells. EVs can modulate the immune response in distant organs, creating a permissive environment for cancer cell colonization. EVs, which are nanoscale vesicles secreted by cells, play a dual role in tumor immune regulation: facilitate immune evasion by tumor cells, thereby promoting tumor growth and metastasis (inducing apoptosis of CD8+ T cells, facilitating generation of Tregs (T regulatory cells), suppressing NK cells cytotoxicity, inhibiting maturation and differentiation of monocyte, and enhancing suppressive function of MDSCs). EVs exosomes also carry and deliver immune-regulating factors that activate and modulate the immune response, thereby increasing defense against malignant diseases [

72,

73].

5.6. Drug Resistance

Cancer-derived EVs can transfer lipids and drug efflux pumps to sensitive cells, conferring resistance to chemotherapy. These vesicles may promote resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapy in cancer, including multidrug resistance (MDR). Members of the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family, namely breast cancer resistance protein (BRCP/ABCG2), ABCA3, multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1/ABCC1), and P-glycoprotein (P-gp/MDR1/ABCB1), were transferred by EVs from drug-resistant cells to drug-sensitive cells. Non-genetic acquisition of P-gp mediating drug resistance or enrichment on this drug efflux pump in EVs shed by drug-resistant cells in several cancers. In malignant melanoma, acidic vesicles can play a fundamental role in resistance to cytotoxic drugs through both sequestration and neutralization of alkaline drugs (e.g., cisplatin) and elimination of these molecules via vesicular transport. EVs derived from cancer stem cells (CSCs) carry a variety of biologically active molecules, including miRNA and lncRNA. These EVs could be taken up by neighboring non-CSCs, which further activate specific drug resistance-related signaling pathways, enabling non-CSCs to acquire a drug resistance phenotype. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) stem cell-derived EVs contained miR-21-5p, which activated the OSCC cells’ PI3K/mTOR/STAT3 signaling pathway, leading to resistance to cisplatin in non-OSCC stem cells [

74,

75,

76,

77,

78].

5.7. Immune Evasion

EVs and nanoparticles can modulate immune cell function by delivering immunosuppressive lipids or altering lipid metabolism in immune cells. These lipids belong to one of several lipid classes, including sphingolipids, phospholipids, glycolipids, and fatty acids. Such lipids are likely to contribute to diverse EV-mediated immunomodulatory functions, including structural preservation/destruction of EVs, metabolic remodeling, and modulation of immune cell signaling. Sphingosine can both mediate structural EV changes and facilitate oncogenic signaling through the release of free lipids with functional activity. SPHK1-packaged EVs contribute to the progression of ovarian cancer. EV-associated glycolipids, such as GD3 ganglioside, have also been linked to T cell suppression in ovarian cancer. Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) α responds to the fatty acids delivered by tumor-derived exosomes (TDEs), resulting in an excess of lipid droplet biogenesis and enhanced fatty acid oxidation (FAO), which culminates in a metabolic shift toward mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, driving dendritic cells DC immune dysfunction. [

79,

80,

81,

82].

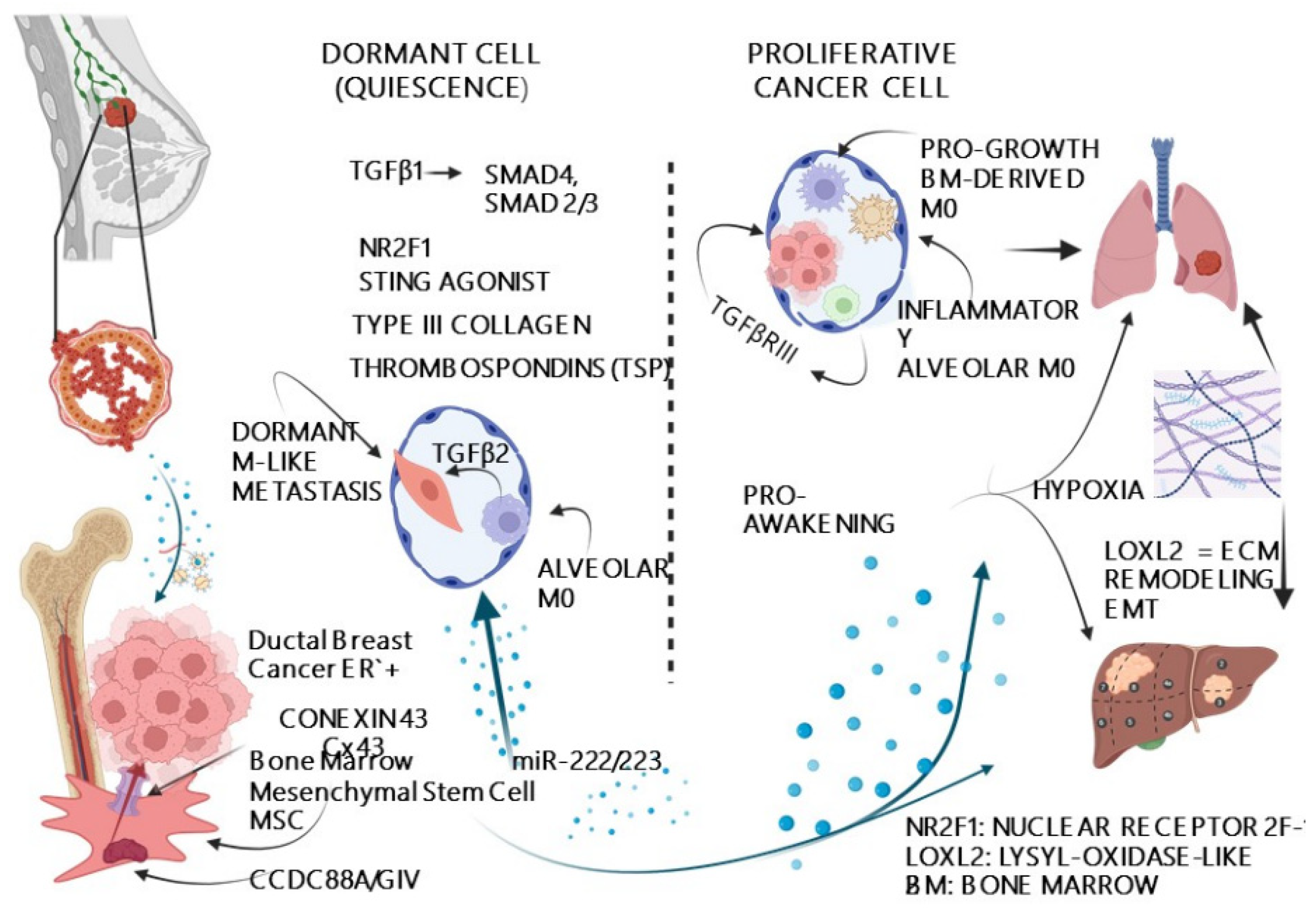

5.8. Cell Dormancy

Lipids transported via EVs can promote cancer cell dormancy, a state of quiescence that allows cancer cells to evade therapy and initiate relapse years later. Tumor dormancy is a reversible state of reduced cell division and metabolic arrest. This event has been reported in colon cancer, kidney cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, melanoma, multiple myeloma, and leukemia. In contrast to active metastasis (high cell proliferation, cell migration, tissue invasion, and chemosensitivity), dormant metastasis exhibits quiescence, proliferation arrest, decreased migration, and chemoresistance. This condition is supported by mechanisms such as the balance between apoptosis and proliferation, as well as limitations in nutrient supply. The angiogenic switch releases tumors from dormancy, triggering rapid growth of malignant cells and the formation of new blood vessels. [

83,

84] (

Figure 2).

5.9. Signaling Pathway Modulation

Lipids can activate or inhibit signaling pathways that regulate cell cycle progression and dormancy. Immunosuppressive M2 macrophages promote B-CSC quiescence through gap junctional intercellular communication. The lipopolysaccharide stimulation of TLR 4 on MSCs leads to the recruitment and reprogramming of M2 macrophages. M2 macrophages are then converted from an anti-inflammatory to a proinflammatory M1 phenotype. Once transformed into M1 macrophages, they have been shown to secrete exosomes, which drive B-CSC migration and enhance cell cycling via NF-κB activation [

85,

86].

5.10. Metabolic Alterations

Lipid metabolism in dormant cancer cells is often altered, with increased lipid storage and utilization. Lipid-related pathways were upregulated in dormant cancer cells. For example, Nakayama et Al (2021) in a human prostate cancer cell line PC-3, found that dormant cancer cells exhibited greater cholesterol synthesis than non-dormant cancer cells. In addition, the lipid metabolism-related genes acyl-CoA synthetase (ACS) medium chain family member three and acyl-CoA synthetase short-chain family member were dramatically upregulated in a dormancy-dependent manner. Lipid metabolism, including ACS expression, was positively associated with Protoporphyrin IX (PpIX) accumulation. This enhancement of lipid metabolism in cancer cells induces PpIX accumulation and increases sensitivity to 5-aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy (ALA-PDT). This is the first evidence of a therapeutic alternative in a highly resistant dormant cell condition [

87].

5.11. Niche Interactions

EVs can facilitate interactions between dormant cancer cells and their microenvironment, providing survival signals that maintain the cells in a dormant state. Timely controlled crosstalk between the cancer cells and the hepatic niche (HepN) exosomes resulted in the increased expression of E-cadherin, a marker of a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition in these cells. This altered secretion promotes the seeding of metastatic breast cancer cells within the hepatic niche, while inhibiting their proliferation and driving a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition that leads to cellular dormancy [

88].

6. Post-Secretion Processes and Modification of Extracellular Vesicles (PSPMs)

Many key features of EVs remain unclear, including biogenesis, cargo regulation, and donor-recipient interactions. Ten et al. (2025) [

89] reviewed additional processes that modify secreted EVs. The surface of EVs may be altered at different stages of intracellular biogenesis and during their interactions with the extracellular matrix. Corporal fluids like blood contribute to the formation of a complex and soft biomolecular corona (ApoA1, ApoB, ApoC3, ApoE, complement factors 3 and 4B, fibrinogen α-chain, immunoglobulin heavy constant γ2 and γ4 chains) that modifies cell-cell interaction [

90]. —inter-exosome interactions: Repulsion, Adhesion, Fusion. The ubiquitously expressed SNARE proteins, such as SNAP-23, VAMP-3, and YKT6, serve general functions in membrane trafficking. In contrast, several others exhibit a clear tissue or cell-type enrichment [

91,

92]. Volumetric changes and deformation play a critical role in the distribution of EVs in tissues, with two fusion modes associated with size changes: shrink fusion and enlarging fusion [

93,

94]. This influences the volume and speed of delivered cargo from donor to receptor space—attachment of EVs to extracellular surface (ECS) components. EVs participate in the ECM architecture and remodeling. Involved in tissue regeneration, inflammation, and heparinase, which cleaves heparan sulfate; this enhances the secretion of EVs that promote tumor progression [

95,

96]. Extracellular destruction: Phospholipases may catalyze micro-vesicle (MV) membrane breakdown necessary for the release of mineral deposits into the extracellular matrix (ECM) [

97].

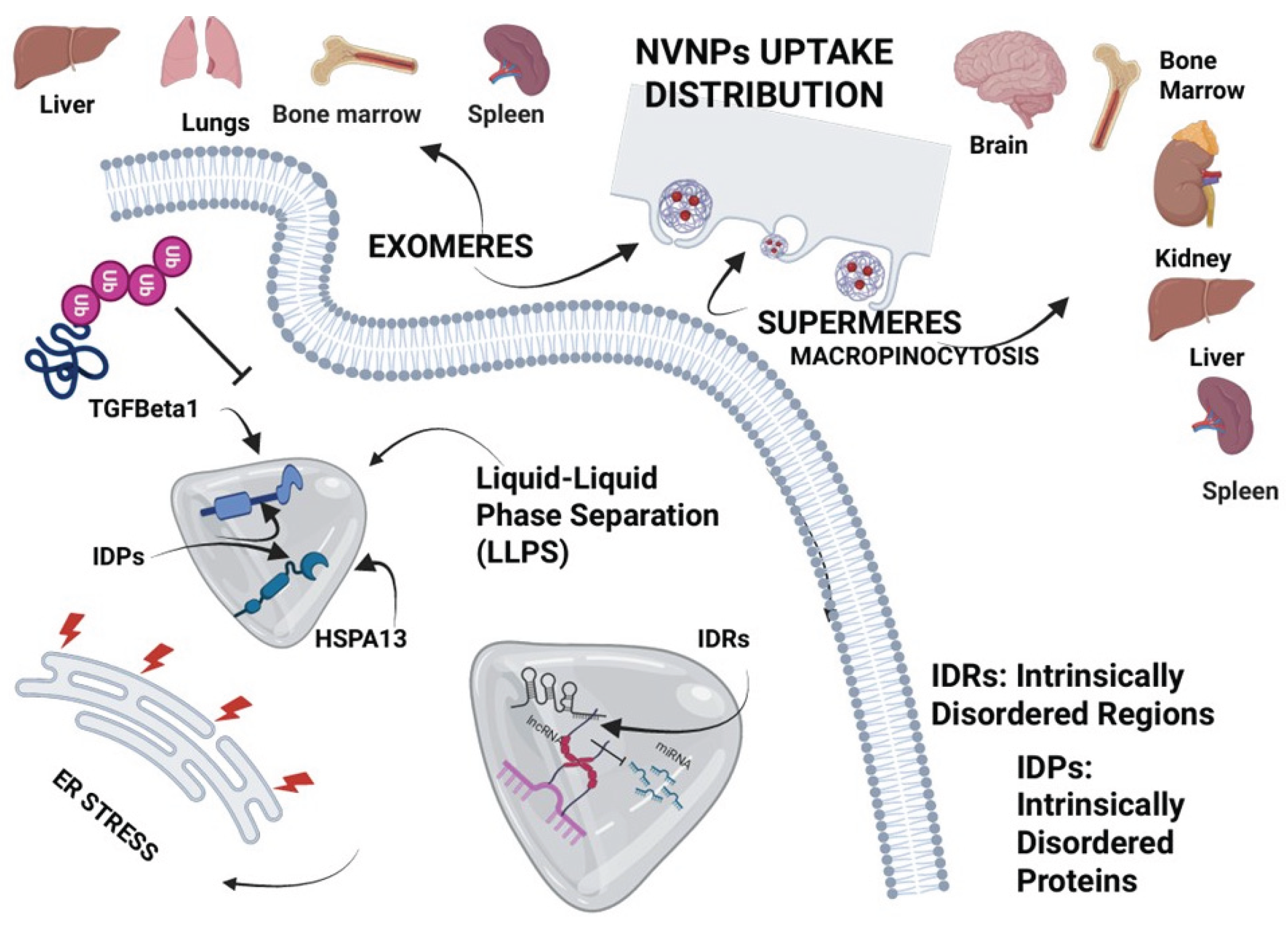

6.1. Exomeres and Supermeres

While non-vesicular nanoparticles called exomeres (50-150 nm) may overlap the same size as sEVs, only differing in the absence of a membrane vesicle, supermeres are smaller than any other EVs, or NVNP (30 nm), are morphologically distinct from exomeres and display a markedly greater uptake, probably by macropinocytosis. Supermeres are highly enriched with cargo involved in multiple cancers (glycolytic enzymes, TGFBI, miR-1246, MET, GPC1, and AGO2), Alzheimer’s disease (APP), and cardiovascular disease (ACE2, ACE, and PCSK9). Most of the extracellular RNA is associated with supermeres rather than small extracellular vesicles and exomeres. Cancer-derived supermeres increase lactate secretion, transfer cetuximab resistance, and decrease hepatic lipids and glycogen in vivo. Transforming Growth Factor-Beta Induced protein (TGFBI), Enolase 1 enzyme (ENO1), and Glypican-1 (GPC1) may be useful markers for extracellular nanoparticles (exomeres and supermeres), whereas Heat Shock Protein Family A (Hsp70) Member 13 (HSPA13) and Enolase 2 (ENO2) are more associated explicitly with supermeres; these are preferentially taken up by the brain, indicating they can traverse the blood–brain barrier. The most abundant and most differentially expressed miRNA in supermeres is miR-1246, with a 1,024-fold change in expression levels compared with cells [

32,

98,

99] (

Figure 3).

7. Reverse Microevolutionary Process and Ancestral Nature of EVs

Neoplastic growth and many of the hallmarks of cancer are driven by the disruption of molecular networks that emerged during the evolution of multicellularity. Gene regulatory networks (GRNs) that emerged during the evolution of metazoans are frequently altered in cancer, leading to the overexpression of genes typically found in unicellular organisms [

13,

100,

101]. The “atavistic theory” of cancer suggests that cancer cells revert to more primitive, unicellular-like states, enabling them to survive and proliferate under challenging conditions [

102]. Some authors do not concur with what they interpret as an evolution-centered byproduct of the somatic mutation theory of cancer (SMT) [

103]. However, cancer evolution towards progression and invasiveness is influenced by both genetic and non-genetic factors, as well as the tumor microenvironment, in promoting intra-tumoral heterogeneity (ITH). Sustained signals for cell proliferation, evasion of programmed cell death, and unlimited replicative potential are other characteristics of cancer promotion and progression that are similar to unicellular organisms. Cancer cell plasticity can be triggered by factors such as heterogeneity at the transcriptomic, epigenomic, or both levels, resulting in changes in survival, stemness potential, and proliferative capacity [

104,

105,

106]. All these events occur within the context of cell-to-cell communication, and EVs and NVNPs act as mediators of such interactions. These particles, as reported by Askenase [

107], are related to ancient universal particles of life that preceded eukaryotic and even prokaryotic cells. Alternatively, the EVs could be related to ancestral primordial vesicles, having arisen again via convergent evolution. The universality of exosomes and their likely ancient origin are compelling reasons to prefer using these vesicles for therapies rather than the current production of human-conceived artificial nanoparticles as therapeutic carriers in cancer and other diseases [

108,

109].

8. Discussion

Lipid-mediated communication via EVs and nanoparticles plays a central role in cancer progression and metastasis (

Figure 1). Understanding the mechanisms underlying this process, as well as the specific lipid species and associated cargo/corona that drive cancer phenotypes, has the potential to inform the development of novel therapeutic strategies. Among many theragnostic developments relying on artificial nanoparticles as carriers, which are still in early phases, a particularly compelling field is the reprogramming/reversion of malignant phenotypes in cancer cells through exposure to embryonic microenvironmental factors.

Since 1974, encouraging results have been reported in reversing the malignant phenotype in mouse testicular teratocarcinoma, as well as interesting findings in MDA-MB-231 cells, an invasive breast cancer cell line, and the potential use of EVs in reprogramming therapy and epigenetic mechanisms [

110,

111,

112,

113].

The central role of vesicles is to regulate the cellular network that maintains the proteomic homeostasis (proteostasis) of a cell. Proteostasis is related to vacuolar protein sorting 35 (VPS35), 29 (VPS29), and 26A (VPS26A). Dysfunction of the VPS complex, which mutations can originate, has been related to neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. VPS35 regulates autophagy, mitophagy, mitochondrial homeostasis, and various other biological processes, including epidermal regeneration, neuronal iron homeostasis, and synaptic function. Dysfunction of these processes is reported in neoplasms such as those of the liver and breast [

114], stomach [

115], and melanoma [

116]. Extracellular vesicle and particle biomarkers are present in multiple human cancers, including lung and pancreatic cancers. Their sensitivity and specificity may aid in differentiating early proteomic signatures associated with distant metastasis from those related to primary tumor activity. Extracellular vesicles are critical mediators of intercellular communication in the tumor microenvironment (TME), profoundly influencing cancer progression [

50,

117].

The discovery of non-vesicular nanoparticles (NVNPs), such as exomeres and supermeres, has opened a new area of research related to biogenesis and cargo transport. Unlike EVs, exomeres and supermeres follow non-canonical biosynthetic pathways, in which cells release specific cytoplasmic contents directly into the extracellular space rather than packaging them into vesicles (

Figure 4). Exomeres may represent a mixture of non-vesicular particles from multiple sources, rather than having an established biological generation path. There are a few publications on biogenesis and its complementary role in normal and abnormal conditions. Zhang et al. [

118] reported that exomeres are enriched in proteins involved in metabolism, such as MAT1A, IDH1, GMPPB, UGP2, EXT1, and PFKL. The sialoglycoprotein galectin-3-binding protein (LGALS3BP) and key proteins controlling glycan-mediated protein folding control (CALR) and glycan processing (MAN2A1, HEXB, GANAB) are also enriched in exomeres, suggesting exomere cargo may mediate the targeting of recipient cells through specific glycan recognition and modulate glycosylation in recipient cells.

Supermeres, on the other hand, are the smallest particles with <35 nm, possess a notably negative charge (approximately –50 mV), attributable to the presence of RNA and an array of surface accessible proteins—including ENO1, ENO2, HSPA13, DDR1, CEACAM5 (CEA), and TGFB induced (TGFBI), while classical tetraspanins are undetectable. Importantly, markers such as HSPA13, ENO2, and DDR1 have demonstrated enhanced specificity for supermeres. Supermeres are enriched with glycolytic enzymes, AGO2, shed MET, and GPC1, as well as miR-1246 cargoes, which are present in multiple cancers. Cancer-derived supermeres increase lactate secretion and decrease hepatic lipids and glycogen production in recipient cells. It is possible that supermeres could be more clinically relevant than EVs in cancer diagnosis [

119,

120]. Overall, the nature, composition, differential cargo, and specific biomarkers indicate that exomeres and supermeres are unique entities released by cells rather than exosome debris or fragments [

121]; however, it remains unclear why these conjugates are not enveloped in vesicles.

Future work will focus on understanding the origin of non-vesicular nanoparticles. In addition, why do exomeres and supermeres not encapsulate in multi-layered membrane vesicles such as exosomes and micro-vesicles? Finally, it is essential to address why exomeres/supermeres are naturally occurring nanoparticles, rather than artifacts produced by high-speed ultracentrifugation during their isolation from cellular components.

Author Contributions

LAA and SD conceptualized this review. LAA and JHR collected information. The drafts were prepared by LAA, revised by JHR, BG, BP and SD.

Funding

The research in the author’s laboratory was supported by a grant U54 MD007592/MD/NIMHD from the National Institutes of Health (United States).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the help of Mr. Angel Torres during the preparation of this article.

Figures were created in BioRender. Adel, L. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/mf80mci

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Baghban, R.; Roshangar, L.; Jahanban-Esfahlan, R.; Seidi, K.; Ebrahimi-Kalan, A.; Jaymand, M.; Kolahian, S.; Javaheri, T.; Zare, P. Tumor Microenvironment Complexity and Therapeutic Implications at a Glance. Cell Commun Signal 2020, 18, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tanani, M.; Rabbani, S.A.; Babiker, R.; Rangraze, I.; Kapre, S.; Palakurthi, S.S.; Alnuqaydan, A.M.; Aljabali, A.A.; Rizzo, M.; El-Tanani, Y.; et al. Unraveling the Tumor Microenvironment: Insights into Cancer Metastasis and Therapeutic Strategies. Cancer Letters 2024, 591, 216894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R.; McAndrews, K.M. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer. Cell 2023, 186, 1610–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clancy, J.W.; Boomgarden, A.C.; D’Souza-Schorey, C. Profiling and Promise of Supermeres. Nat Cell Biol 2021, 23, 1217–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortzel, I.; Dror, S.; Kenific, C.M.; Lyden, D. Exosome-Mediated Metastasis: Communication from a Distance. Developmental Cell 2019, 49, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirani, N.; Abdi, N.; Chehelgerdi, M.; Yaghoobi, H.; Chehelgerdi, M. Investigating the Role of Exosomal Long Non-Coding RNAs in Drug Resistance within Female Reproductive System Cancers. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1485422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, S. Extracellular Vesicle-Mediated Crosstalk between Pancreatic Cancer and Stromal Cells in the Tumor Microenvironment. J Nanobiotechnol 2022, 20, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fyfe, J.; Casari, I.; Manfredi, M.; Falasca, M. Role of Lipid Signalling in Extracellular Vesicles-Mediated Cell-to-Cell Communication. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2023, 73, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida-Aoki, N.; Izumi, Y.; Takeda, H.; Takahashi, M.; Ochiya, T.; Bamba, T. Lipidomic Analysis of Cells and Extracellular Vesicles from High- and Low-Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Metabolites 2020, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzozowski, J.S.; Jankowski, H.; Bond, D.R.; McCague, S.B.; Munro, B.R.; Predebon, M.J.; Scarlett, C.J.; Skelding, K.A.; Weidenhofer, J. Lipidomic Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles Derived from Prostate and Prostate Cancer Cell Lines—Lipids Health Dis. 2018, 17, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos, A.S.; Pearson, R.B.; Papenfuss, A.T.; Goode, D.L. How the Evolution of Multicellularity Set the Stage for Cancer. Br J Cancer 2018, 118, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussey, K.J.; Cisneros, L.H.; Lineweaver, C.H.; Davies, P.C.W. Ancestral Gene Regulatory Networks Drive Cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2017, 114, 6160–6162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigos, A.S.; Bongiovanni, F.; Zhang, Y.; Zethoven, M.; Tothill, R.; Pearson, R.; Papenfuss, A.T.; Goode, D.L. Disruption of Metazoan Gene Regulatory Networks in Cancer Alters the Balance of Co-Expression between Genes of Unicellular and Multicellular Origins. Genome Biol 2024, 25, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.F.; Nee, E.; Lane, N. Isoprenoids Enhance the Stability of Fatty Acid Membranes at the Emergence of Life Potentially Leading to an Early Lipid Divide. Interface Focus. 2019, 9, 20190067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albani, A.E.; Bengtson, S.; Canfield, D.E.; Bekker, A.; Macchiarelli, R.; Mazurier, A.; Hammarlund, E.U.; Boulvais, P.; Dupuy, J.-J.; Fontaine, C.; et al. Large Colonial Organisms with Coordinated Growth in Oxygenated Environments 2.1 Gyr Ago. Nature 2010, 466, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller, S.M. Early Beginnings - the Emergence of Complex Signaling Systems and Cell-to-Cell Communication. Cell Commun Signal 2010, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ros-Rocher, N.; Pérez-Posada, A.; Leger, M.M.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. The Origin of Animals: An Ancestral Reconstruction of the Unicellular-to-Multicellular Transition. Open Biol. 2021, 11, 200359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunet, T.; King, N. The Origin of Animal Multicellularity and Cell Differentiation. Developmental Cell 2017, 43, 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebé-Pedrós, A.; Degnan, B.M.; Ruiz-Trillo, I. The Origin of Metazoa: A Unicellular Perspective. Nat Rev Genet 2017, 18, 498–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, M.A.; Schmidt, W.F.; Broadhurst, C.L.; Wang, Y. Lipids in the Origin of Intracellular Detail and Speciation in the Cambrian Epoch and the Significance of the Last Double Bond of Docosahexaenoic Acid in Cell Signaling. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2021, 166, 102230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.; Brigger, F.; Leroux, J.-C. Extracellular Vesicles versus Lipid Nanoparticles for the Delivery of Nucleic Acids. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2024, 215, 115461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espiau-Romera, P.; Gordo-Ortiz, A.; Ortiz-de-Solórzano, I.; Sancho, P. Metabolic Features of Tumor-Derived Extracellular Vesicles: Challenges and Opportunities. Extracell Vesicles Circ Nucleic Acids 2024, 5, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoto, T.; Saini, S. Role of Exosomes in Prostate Cancer Metastasis. IJMS 2021, 22, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfrieger, F.W.; Vitale, N. Thematic Review Series: Exosomes and Microvesicles: Lipids as Key Components of Their Biogenesis and Functions, Cholesterol and the Journey of Extracellular Vesicles. Journal of Lipid Research 2018, 59, 2255–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Larrauri, A.; Larrea-Sebal, A.; Martín, C.; Gomez-Muñoz, A. The Critical Roles of Bioactive Sphingolipids in Inflammation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2025, 301, 110475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Fu, W.; Deng, M.; Li, X.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y. The Sphingolipids Change in Exosomes from Cancer Patients and Association between Exosome Release and Sphingolipids Level Based on a Pseudotargeted Lipidomics Method. Analytica Chimica Acta 2024, 1305, 342527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stace, C.; Ktistakis, N. Phosphatidic Acid- and Phosphatidylserine-Binding Proteins. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2006, 1761, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, S.; Ikeda, Y. Regulation of Membrane Phospholipid Biosynthesis in Mammalian Cells. Biochemical Pharmacology 2022, 206, 115296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, M.; Kazanietz, M.G. Overarching Roles of Diacylglycerol Signaling in Cancer Development and Antitumor Immunity. Sci. Signal. 2022, 15, eabo0264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundram, V.; Chauhan, S.C.; Jaggi, M. Emerging Roles of Protein Kinase D1 in Cancer. Molecular Cancer Research 2011, 9, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durand, N.; Borges, S.; Storz, P. Functional and Therapeutic Significance of Protein Kinase D Enzymes in Invasive Breast Cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 4369–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Jeppesen, D.K.; Yang, Y.-P.; Li, W.; McKinley, E.T.; Graves-Deal, R.; Ping, J.; Britain, C.M.; Dorsett, K.A.; et al. Transfer of Functional Cargo in Exomeres. Cell Reports 2019, 27, 940–954.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Record, M.; Silvente-Poirot, S.; Poirot, M.; Wakelam, MichaelJ.O. Extracellular Vesicles: Lipids as Key Components of Their Biogenesis and Functions. Journal of Lipid Research 2018, 59, 1316–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadami, S.; Dellinger, K. The Lipid Composition of Extracellular Vesicles: Applications in Diagnostics and Therapeutic Delivery. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023, 10, 1198044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribovski, L.; Joshi, B.S.; Gao, J.; Zuhorn, I.S. Breaking Free: Endocytosis and Endosomal Escape of Extracellular Vesicles. Extracell Vesicles Circ Nucleic Acids 2023, 4, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Brocchini, S.; Williams, G.R. Extracellular Vesicle-Embedded Materials. Journal of Controlled Release 2023, 361, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, Z.H.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y. Extracellular Vesicle Transportation and Uptake by Recipient Cells: A Critical Process to Regulate Human Diseases. Processes 2021, 9, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragni, E. Extracellular Vesicles: Recent Advances and Perspectives. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed) 2025, 30, 36405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, E.; Lazar, I.; Attané, C.; Carrié, L.; Dauvillier, S.; Ducoux--Petit, M.; Esteve, D.; Menneteau, T.; Moutahir, M.; Le Gonidec, S.; et al. Adipocyte Extracellular Vesicles Carry Enzymes and Fatty Acids That Stimulate Mitochondrial Metabolism and Remodeling in Tumor Cells. The EMBO Journal 2020, 39, e102525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, D.; Wang, Z.; Xia, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X. Research Progress on the Role of Adipocyte Exosomes in Cancer Progression. OR 2024, 32, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazar, I.; Clement, E.; Attane, C.; Muller, C.; Nieto, L. A New Role for Extracellular Vesicles: How Small Vesicles Can Feed Tumors’ Big Appetite. Journal of Lipid Research 2018, 59, 1793–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, W.; Chopp, M.; Zhang, Z.G.; Zhang, Y. Therapeutic and Diagnostic Potential of Extracellular Vesicle (EV)-Mediated Intercellular Transfer of Mitochondria and Mitochondrial Components. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2025, 0271678X251338971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penkov, S.; Fedorova, M. Membrane Epilipidome—Lipid Modifications, Their Dynamics, and Functional Significance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2024, 16, a041417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wölk, M.; Prabutzki, P.; Fedorova, M. Analytical Toolbox to Unlock the Diversity of Oxidized Lipids. Acc. Chem. Res. 2023, 56, 835–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duché, G.; Sanderson, J.M. The Chemical Reactivity of Membrane Lipids. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 3284–3330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Peng, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z. The Dual Role of Exosomes in the Tumor Microenvironment: From Pro--Tumorigenic Signaling to Immune Modulation. Med Research 2025, 1, 257–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnat, M.A.; Ohmi, Y.; Yesmin, F.; Kaneko, K.; Kambe, M.; Kitaura, Y.; Ito, T.; Imao, Y.; Kano, K.; Mishiro-Sato, E.; et al. Action Mechanisms of Exosomes Derived from GD3/GD2-Positive Glioma Cells in the Regulation of Phenotypes and Intracellular Signaling: Roles of Integrins. IJMS 2024, 25, 12752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, N.; Qiu, H.; Liu, J.; Xiao, D.; Zhao, J.; Chen, C.; Wan, J.; Guo, M.; Liang, G.; Zhao, X.; et al. Targeting Lipid Metabolism of Macrophages: A New Strategy for Tumor Therapy. Journal of Advanced Research 2025, 68, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; He, Y.; Zhao, P.; Hu, Y.; Tao, J.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y. Targeting Lipid Metabolism to Overcome EMT-Associated Drug Resistance via Integrin Β3/FAK Pathway and Tumor-Associated Macrophage Repolarization Using Legumain-Activatable Delivery. Theranostics 2019, 9, 265–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.-L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Tesic Mark, M.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.; Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour Exosome Integrins Determine Organotropic Metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Qin, Y.; Yu, X.; Xu, X.; Yu, W. Lipid Raft Involvement in Signal Transduction in Cancer Cell Survival, Cell Death and Metastasis. Cell Proliferation 2022, 55, e13167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lietha, D.; Izard, T. Roles of Membrane Domains in Integrin-Mediated Cell Adhesion. IJMS 2020, 21, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, K.; Miki, Y.; Carreras, J.; Nakayama, S.; Nakamoto, Y.; Ito, M.; Nagashima, E.; Yamamoto, K.; Higuchi, H.; Morita, S.; et al. Secreted Phospholipase A2 Modifies Extracellular Vesicles and Accelerates B Cell Lymphoma. Cell Metabolism 2022, 34, 615–633.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraszti, R.A.; Didiot, M.; Sapp, E.; Leszyk, J.; Shaffer, S.A.; Rockwell, H.E.; Gao, F.; Narain, N.R.; DiFiglia, M.; Kiebish, M.A.; et al. High--resolution Proteomic and Lipidomic Analysis of Exosomes and Microvesicles from Different Cell Sources. J of Extracellular Vesicle 2016, 5, 32570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvaiya, P.J.; Guo, D.; Ulasov, I.; Gabikian, P.; Lesniak, M.S. Chemokines in Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Oncotarget 2013, 4, 2171–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Qu, C.; Xiao, P.; Liu, S.; Sun, J.-P.; Ping, Y.-Q. Progress in Structure-Based Drug Development Targeting Chemokine Receptors. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1603950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuzzi, E.; Angioni, R.; Molon, B.; Calì, B. Chemokines and Chemokine Receptors: Orchestrating Tumor Metastasization. IJMS 2018, 20, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tvaroška, I.; Selvaraj, C.; Koča, J. Selectins—The Two Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Faces of Adhesion Molecules—A Review. Molecules 2020, 25, 2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugonnet, M.; Singh, P.; Haas, Q.; Von Gunten, S. The Distinct Roles of Sialyltransferases in Cancer Biology and Onco-Immunology. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 799861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrobono, S.; Stecca, B. Aberrant Sialylation in Cancer: Biomarker and Potential Target for Therapeutic Intervention? Cancers 2021, 13, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.; Xu, X.; Zhou, X.; Feng, H.; Wang, R.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.; Fan, N.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; et al. Sialylation on Vesicular Integrin Β1 Determined Endocytic Entry of Small Extracellular Vesicles into Recipient Cells. Cell Mol Biol Lett 2024, 29, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burčík, D.; Macko, J.; Podrojková, N.; Demeterová, J.; Stano, M.; Oriňak, A. Role of Cell Adhesion in Cancer Metastasis Formation: A Review. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 5193–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Ma, X.; Yu, J. Exosomes and Organ-Specific Metastasis. Molecular Therapy - Methods & Clinical Development 2021, 22, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, F.; Tao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. The Biological Functions and Clinical Applications of Integrins in Cancers. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 579068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, F.; Huang, J.; Wu, C.; Zhong, H.; Qiu, G.; Luo, T.; Tang, W. Integrin A6 and Integrin Β4 in Exosomes Promote Lung Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer. Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics 2024, 20, 2082–2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannan, L.; Oudart, J.-B.; Monboisse, J.C.; Ramont, L.; Brassart-Pasco, S.; Brassart, B. Extracellular Vesicle-Dependent Cross-Talk in Cancer—Focus on Pancreatic Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, B.H.; Emmanuel, M.; Gari, M.K.; Guerrero, J.F.; Virumbrales-Muñoz, M.; Inman, D.; Krystofiak, E.; Rapraeger, A.C.; Ponik, S.M.; Weaver, A.M. Exosomes Are Specialized Vehicles to Induce Fibronectin Assembly 2025.

- Hirosawa, K.M.; Sato, Y.; Kasai, R.S.; Yamaguchi, E.; Komura, N.; Ando, H.; Hoshino, A.; Yokota, Y.; Suzuki, K.G.N. Uptake of Small Extracellular Vesicles by Recipient Cells Is Facilitated by Paracrine Adhesion Signaling. Nat Commun 2025, 16, 2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanasu, C.; Le Clainche, C. Integrins from Extracellular Vesicles as Players in Tumor Microenvironment and Metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2025, 44, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.-Q.; Sun, L.; Wang, S.-M.; Zheng, X.-Y.; Xu, R. Exosomal Integrins in Tumor Progression, Treatment and Clinical Prediction (Review). Int J Oncol 2024, 65, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burčík, D.; Macko, J.; Podrojková, N.; Demeterová, J.; Stano, M.; Oriňak, A. Role of Cell Adhesion in Cancer Metastasis Formation: A Review. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 5193–5213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nidhi, G.; Yadav, V.; Singh, T.; Sharma, D.; Bohot, M.; Satapathy, S.R. Beyond Boundaries: Exploring the Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Organ-Specific Metastasis in Solid Tumors. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1593834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, L.; Wu, L.; Li, Y. Extracellular Vesicles in Tumor Immunity: Mechanisms and Novel Insights. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurj, A.; Paul, D.; Calin, G.A. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: From Isolation and Characterization to Metastasis, Drug Resistance, and Clinical Applications. BMC Cancer 2025, 25, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucci-Muñoz, M.; Gola, A.M.; Rigalli, J.P.; Ceballos, M.P.; Ruiz, M.L. Extracellular Vesicles and Cancer Multidrug Resistance: Undesirable Intercellular Messengers? Life 2023, 13, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, C.P.R.; Belisario, D.C.; Rebelo, R.; Assaraf, Y.G.; Giovannetti, E.; Kopecka, J.; Vasconcelos, M.H. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in the Transfer of Drug Resistance Competences to Cancer Cells. Drug Resistance Updates 2022, 62, 100833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musi, A.; Bongiovanni, L. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer Drug Resistance: Implications on Melanoma Therapy. Cancers 2023, 15, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Liu, S.; Yu, L.; Liu, S.; Li, M.; Jin, F. Extracellular Vesicles in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Current Progress and Future Prospect. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1149662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Iannotta, D.; O’Mara, M.L.; Goncalves, J.P.; Wolfram, J. Extracellular Vesicle Lipids in Cancer Immunoevasion. Trends in Cancer 2023, 9, 883–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Kadamberi, I.P.; Mittal, S.; Tsaih, S.; George, J.; Kumar, S.; Vijayan, D.K.; Geethadevi, A.; Parashar, D.; Topchyan, P.; et al. Tumor Derived Extracellular Vesicles Drive T Cell Exhaustion in Tumor Microenvironment through Sphingosine Mediated Signaling and Impacting Immunotherapy Outcomes in Ovarian Cancer. Advanced Science 2022, 9, 2104452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, G.N.; Loyall, J.; Berenson, C.S.; Kelleher, R.J.; Iyer, V.; Balu-Iyer, S.V.; Odunsi, K.; Bankert, R.B. Sialic Acid–Dependent Inhibition of T Cells by Exosomal Ganglioside GD3 in Ovarian Tumor Microenvironments. The Journal of Immunology 2018, 201, 3750–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Zeng, W.; Wu, B.; Wang, L.; Wang, Z.; Tian, H.; Wang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Clay, R.; Wei, X.; et al. PPARα Inhibition Overcomes Tumor-Derived Exosomal Lipid-Induced Dendritic Cell Dysfunction. Cell Reports 2020, 33, 108278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrollahzadeh, E.; Rezaei, N. Time to Sleep: Immunologic Niche Switches Tumor Dormancy at Metastatic Sites. In Cancerous Cells; Rezaei, N., Ed.; Handbook of Cancer and Immunology; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2025; Vol. 2, pp. 635–661. ISBN 978-3-032-00758-2. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, A.; Pal, A.K.; Roy, S.; Nandave, M.; Jain, K. Role of Angiogenesis and Its Biomarkers in Development of Targeted Tumor Therapies. Stem Cells International 2024, 2024, 9077926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.-H.; Li, N. Tumor Dormancy and Relapse: Understanding the Molecular Mechanisms of Cancer Recurrence. Military Med Res 2025, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.D.; Elias, M.; Guiro, K.; Bhatia, R.; Greco, S.J.; Bryan, M.; Gergues, M.; Sandiford, O.A.; Ponzio, N.M.; Leibovich, S.J.; et al. Exosomes from Differentially Activated Macrophages Influence Dormancy or Resurgence of Breast Cancer Cells within Bone Marrow Stroma. Cell Death Dis 2019, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakayama, T.; Sano, T.; Oshimo, Y.; Kawada, C.; Kasai, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Fukuhara, H.; Inoue, K.; Ogura, S. Enhanced Lipid Metabolism Induces the Sensitivity of Dormant Cancer Cells to 5-Aminolevulinic Acid-Based Photodynamic Therapy. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 7290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dioufa, N.; Clark, A.M.; Ma, B.; Beckwitt, C.H.; Wells, A. Bi-Directional Exosome-Driven Intercommunication between the Hepatic Niche and Cancer Cells. Mol Cancer 2017, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ten, A.; Yudintceva, N.; Samochernykh, K.; Combs, S.E.; Jha, H.C.; Gao, H.; Shevtsov, M. Post-Secretion Processes and Modification of Extracellular Vesicles. Cells 2025, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, E.Á.; Turiák, L.; Visnovitz, T.; Cserép, C.; Mázló, A.; Sódar, B.W.; Försönits, A.I.; Petővári, G.; Sebestyén, A.; Komlósi, Z.; et al. Formation of a Protein Corona on the Surface of Extracellular Vesicles in Blood Plasma. J of Extracellular Vesicle 2021, 10, e12140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beit--Yannai, E.; Tabak, S.; Stamer, W.D. Physical Exosome:Exosome Interactions. J Cellular Molecular Medi 2018, 22, 2001–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogungbemi, D.; Shorter, S.; Asadollahi, R.; Boussios, S.; Ovsepian, S.V. Molecular Engines Driving Biogenesis, Trafficking and Release of Exosomes: SNARE Proteins. Extracellular Vesicle 2025, 6, 100089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.; Arpino, G.; Thiyagarajan, S.; Su, R.; Ge, L.; McDargh, Z.; Guo, X.; Wei, L.; Shupliakov, O.; Jin, A.; et al. Vesicle Shrinking and Enlargement Play Opposing Roles in the Release of Exocytotic Contents. Cell Reports 2020, 30, 421–431.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W.; Papoutsakis, E.T. The Role of Biomechanical Stress in Extracellular Vesicle Formation, Composition and Activity. Biotechnology Advances 2023, 66, 108158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, D.; Ye, Z.; Xu, J. Engineering Extracellular Vesicles as Delivery Systems in Therapeutic Applications. Advanced Science 2023, 10, 2300552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuzaka, Y.; Yashiro, R. Classification and Molecular Functions of Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans and Their Molecular Mechanisms with the Receptor. Biologics 2024, 4, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, M. Extracellular Vesicles as a Hydrolytic Platform of Secreted Phospholipase A2. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2024, 1869, 159536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Zhang, Q.; Franklin, J.L.; Coffey, R.J. Extracellular Vesicles and Nanoparticles: Emerging Complexities. Trends in Cell Biology 2023, 33, 667–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Jeppesen, D.K.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Graves-Deal, R.; Trinh, V.Q.; Ramirez, M.A.; Sohn, Y.; Neininger, A.C.; Taneja, N.; McKinley, E.T.; et al. Supermeres Are Functional Extracellular Nanoparticles Replete with Disease Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets. Nat Cell Biol 2021, 23, 1240–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domazet-Lošo, T.; Tautz, D. Phylostratigraphic Tracking of Cancer Genes Suggests a Link to the Emergence of Multicellularity in Metazoa. BMC Biol 2010, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bussey, K.J.; Davies, P.C.W. Reverting to Single-Cell Biology: The Predictions of the Atavism Theory of Cancer. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology 2021, 165, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, J. Evidence for the Atavistic Reversal to a Unicellular--like State as a Central Hallmark of Cancer. Intl Journal of Cancer 2025, 156, 1671–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daignan--Fornier, B.; Pradeu, T. Critically Assessing Atavism, an Evolution--centered and Deterministic Hypothesis on Cancer. BioEssays 2024, 46, 2300221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proietto, M.; Crippa, M.; Damiani, C.; Pasquale, V.; Sacco, E.; Vanoni, M.; Gilardi, M. Tumor Heterogeneity: Preclinical Models, Emerging Technologies, and Future Applications. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1164535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Lawati, Z.; Al Lawati, A. Short Communication | Hallmarks of Cancer; A Summarized Overview of Sustained Proliferative Signalling Component. Gulf J Oncolog 2025, 1, 36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bhat, G.R.; Sethi, I.; Sadida, H.Q.; Rah, B.; Mir, R.; Algehainy, N.; Albalawi, I.A.; Masoodi, T.; Subbaraj, G.K.; Jamal, F.; et al. Cancer Cell Plasticity: From Cellular, Molecular, and Genetic Mechanisms to Tumor Heterogeneity and Drug Resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2024, 43, 197–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askenase, P.W. Ancient Evolutionary Origin and Properties of Universally Produced Natural Exosomes Contribute to Their Therapeutic Superiority Compared to Artificial Nanoparticles. IJMS 2021, 22, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashouri, A.; Zhang, C.; Gaiti, F. Decoding Cancer Evolution: Integrating Genetic and Non-Genetic Insights. Genes 2023, 14, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperski, A. Life Entrapped in a Network of Atavistic Attractors: How to Find a Rescue. IJMS 2022, 23, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinster, R.L. The effect of cells transferred into the mouse blastocyst on subsequent development. J Exp Med 1974, 140, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proietti, S.; Cucina, A.; Pensotti, A.; Biava, P.M.; Minini, M.; Monti, N.; Catizone, A.; Ricci, G.; Leonetti, E.; Harrath, A.H.; et al. Active Fraction from Embryo Fish Extracts Induces Reversion of the Malignant Invasive Phenotype in Breast Cancer through Down-Regulation of TCTP and Modulation of E-Cadherin/β-Catenin Pathway. IJMS 2019, 20, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, M.J.; Kweh, M.F.; Biava, P.M.; Olalde, J.; Toro, A.P.; Goldschmidt-Clermont, P.J.; White, I.A. Evaluation of Exosome Derivatives as Bio-Informational Reprogramming Therapy for Cancer. J Transl Med 2021, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensotti, A.; Bizzarri, M.; Bertolaso, M. The Phenotypic Reversion of Cancer: Experimental Evidences on Cancer Reversibility through Epigenetic Mechanisms (Review). Oncol Rep 2024, 51, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Xie, Y.; Cao, S.; Zhu, L.; Wang, X. VPS35-Retromer: Multifunctional Roles in Various Biological Processes – A Focus on Neurodegenerative Diseases and Cancer. JIR 2025, 18, 4665–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Feng, H.; Sang, Q.; Li, F.; Chen, M.; Yu, B.; Xu, Z.; Pan, T.; Wu, X.; Hou, J.; et al. VPS35 Promotes Cell Proliferation via EGFR Recycling and Enhances EGFR Inhibitors Response in Gastric Cancer. eBioMedicine 2023, 89, 104451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Q.; Bai, Y.; Guan, R.; Dong, R.; Bai, W.; Hamdy, H.; Wang, L.; Meng, M.; Sun, Y.; Shen, J.; et al. VPS35/Retromer-Dependent MT1-MMP Regulation Confers Melanoma Metastasis. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 1996–2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeradtova, A.; Liegertova, M.; Herma, R.; Capkova, M.; Brignole, C.; Del Zotto, G. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer’s Communication: Messages We Can Read and How to Answer. Mol Cancer 2025, 24, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Freitas, D.; Kim, H.S.; Fabijanic, K.; Li, Z.; Chen, H.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.; Martin, A.B.; Bojmar, L.; et al. Identification of Distinct Nanoparticles and Subsets of Extracellular Vesicles by Asymmetric Flow Field-Flow Fractionation. Nat Cell Biol 2018, 20, 332–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Sinclair, J.A.; Shi, T.; Kim, G.; Zhu, R.; Gasper, G.; Wang, Y.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Jeppesen, D.K.; et al. Surface Markers on Supermeres Outperform Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer Diagnosis 2025.

- Yu, L.; Shi, H.; Gao, T.; Xu, W.; Qian, H.; Jiang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, X. Exomeres and Supermeres: Current Advances and Perspectives. Bioactive Materials 2025, 50, 322–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Zhang, Q.; Franklin, J.L.; Coffey, R.J. Are Supermeres a Distinct Nanoparticle? J of Extracellular Bio 2022, 1, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).