Submitted:

01 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Case Report

3. Results

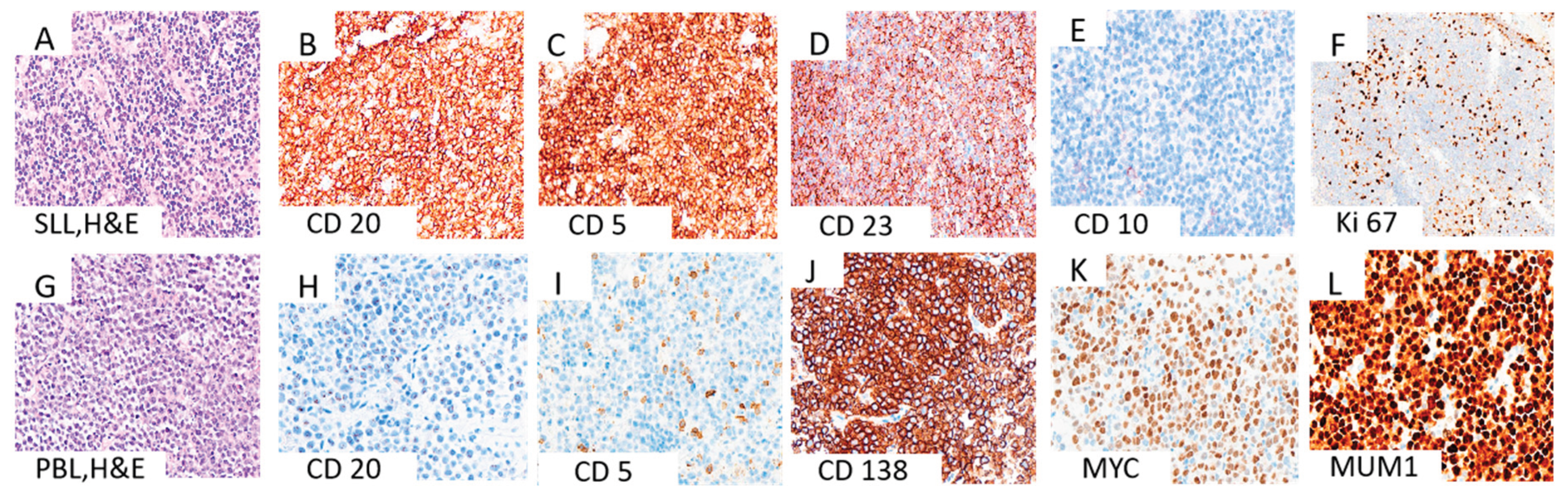

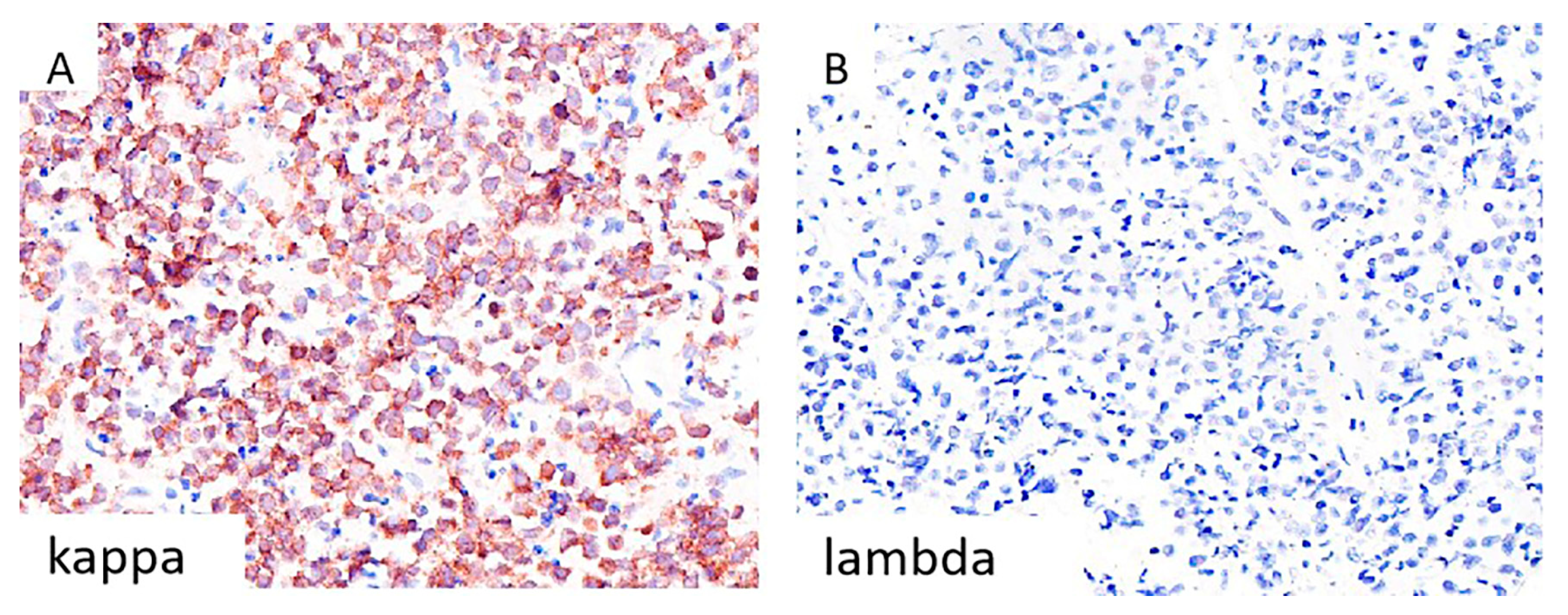

3.1. Morphological and Immunohistochemical Evaluation

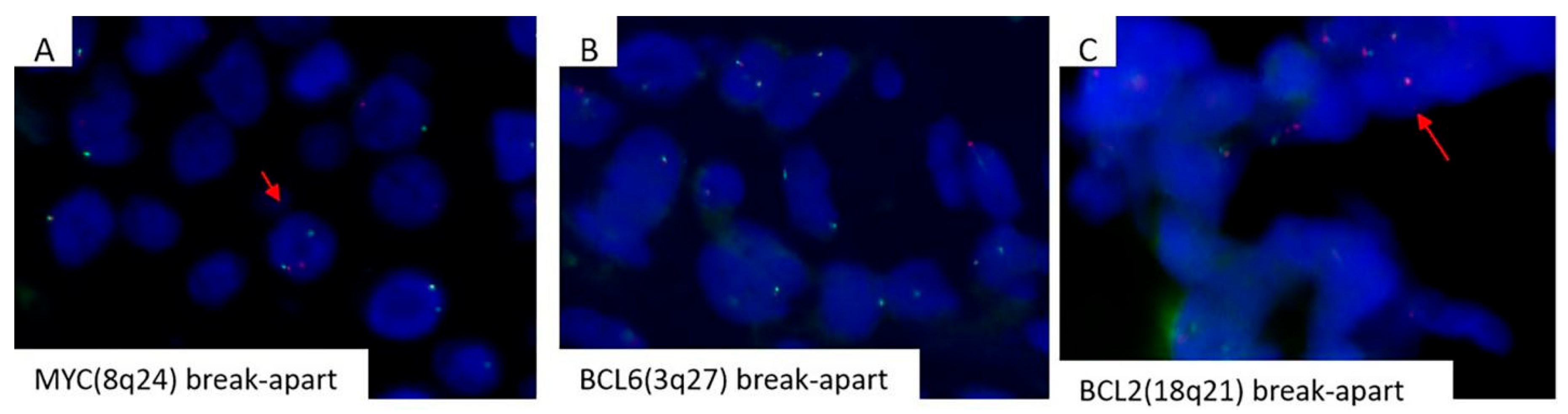

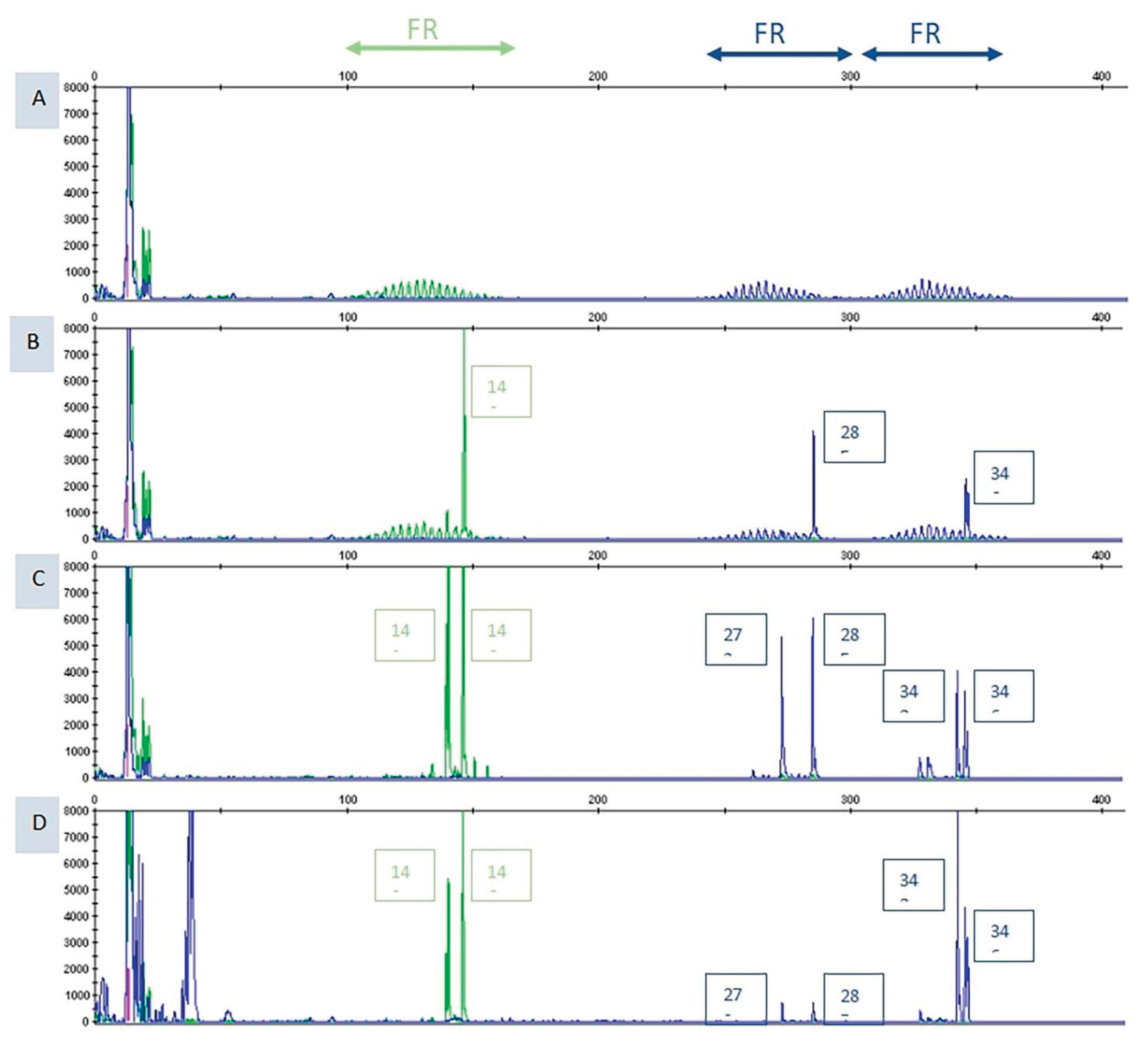

3.2. Mollecular Analysis

3.3. Therapy

3.4. Brief review of Synchronous Versus Metachronous Transformations Reported in the Literature

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Petrackova, A; Turcsanyi, P; Papajik, T; Kriegova, E. Revisiting Richter transformation in the era of novel CLL agents. Blood Rev. 2021, 49, 100824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, A; Drumheller, BR; Deeb, G; Tolbert, EW; Asakrah, S. Plasmablastic transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a review of literature and report on 2 cases. Lab Med. 2023, 54(6), e177-85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, J; Jenkins, N; Chetty, D; Mohamed, Z; Verburgh, ER; Opie, JJ. Plasmablastic lymphoma: An update [published correction appears in Int J Lab Hematol. 2022 Dec; 44(6):1121. (doi: 10.1111/ijlh.13981)]. Int J Lab Hematol. 2022, 44 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teruya-Feldstein, J. Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphomas with Plasmablastic Differentiation. Curr Oncol Rep. 2005, 7, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt R, Naha K, Desai DS. Plasmablastic Lymphoma. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; February 17, 2024.

- Delecluse, HJ; Anagnostopoulos, I; Dallenbach, F; Hummel, M; Marafioti, T; Schneider, U; et al. Plasmablastic lymphomas of the oral cavity: a new entity associated with the human immunodeficiency virus infection. Blood 1997, 89(4), 1413–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, BJ; Chuang, SS. Lymphoid Neoplasms With Plasmablastic Differentiation: A Comprehensive Review and Diagnostic Approaches. Adv Anat Pathol. 2020, 27(2), 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatzimichael, E; Papathanasiou, K; Zerdes, I; Flindris, S; Papoudou-Bai, A; Kapsali, E. Plasmablastic Lymphoma with Coexistence of Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in an Immunocompetent Patient: A Case Report and Mini-Review. Case Rep Hematol. 2017, 2017, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z; Xie, Q; Repertinger, S; Richendollar, BG; Chan, WC; Huang, Q. Plasmablastic transformation of low-grade CD5+ B-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with MYC gene rearrangements. Hum Pathol. 2013, 44(10), 2139–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robak, T; Urbańska-Ryś, H; Strzelecka, B; Krykowski, E; Bartkowiak, J; Bĺoński, JZ; et al. Plasmablastic lymphoma in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia heavily pretreated with cladribine (2-CdA): an unusual variant of Richter’s syndrome. Eur J Haematol. 2001, 67(5-6), 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasljevic, G; Grat, M; Kloboves Prevodnik, V; Grcar Kuzmanov, B; Gazic, B; Lovrecic, L; et al. Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia with Divergent Richter’s Transformation into a Clonally Related Classical Hodgkin’s and Plasmablastic Lymphoma: A Case Report. Case Rep Oncol. 2020, 13(1), 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D; Valera, A; Perez, NS; Villegas, LFS; Gonzalez-Farre, B; Sole, C; et al. Plasmablastic transformation of low-grade B-cell lymphomas: report on 6 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013, 37(2), 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loghavi, S; Alayed, K; Aladily, TN; Zuo, Z; Ng, SB; Tang, G; et al. Stage, age, and EBV status impact outcomes of plasmablastic lymphoma patients: a clinicopathologic analysis of 61 patients. J Hematol Oncol. 2015, 8(1), 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo, JJ; Guerrero--Garcia, T; Baldini, F; Tchernonog, E; Cartron, G; Ninkovic, S; et al. Bortezomib plus EPOCH is effective as frontline treatment in patients with plasmablastic lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2019, 184(4), 679–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimm, KE; O’Malley, DP. Aggressive B cell lymphomas in the 2017 revised WHO classification of tumors of hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2019, 38, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronchi, A; Marra, L; Frigeri, F; Botti, G; Franco, R; De Chiara, A. Richter Syndrome With Plasmablastic Lymphoma at Primary Diagnosis: A Case Report With a Review of the Literature. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol 2017, 25(6), e40-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, MC; Sabatini, PJB; Smith, AC; Sakhdari, A. Molecular characterization and clonal evolution in Richter transformation: Insights from a case of plasmablastic lymphoma (RT--PBL) arising from chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and review of the literature. EJHaem 2023, 4(4), 1203–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, KL; Blombery, P; Jones, K; et al. Plasmablastic Richter transformation as a resistance mechanism for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia treated with BCR signalling inhibitors. Br J Haematol. 2017, 177(2), 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Reyero, J; Martinez Magunacelaya, N; Gonzalez de Villambrosia, S; Loghavi, S; Gomez Mediavilla, A; Tonda, R; et al. Genetic lesions in MYC and STAT3 drive oncogenic transcription factor overexpression in plasmablastic lymphoma. Haematologica 2021, 106(4), 1120–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Brand, M; Möbs, M; Otto, F; Kroeze, LI; Gonzalez de Castro, D; Stamatopoulos, K; et al. EuroClonality-NGS Recommendations for Evaluation of B-Cell Clonality Analysis by Next-Generation Sequencing. J Mol Diagnostics 2023, 25(10), 729–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumder, S; Jinkala, S; Gochhait, D; Manivannan, P; Amalnath, D. Concomitant diagnosis of plasmablastic lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A rare phenomenon. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2021, 11(3), 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holderness, BM; Malhotra, S; Levy, NB; Danilov, A V. Brentuximab vedotin demonstrates activity in a patient with plasmablastic lymphoma arising from a background of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2013, 31(12), e197-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramalingam, P; Nayak-Kapoor, A; Reid-Nicholson, M; Jones-Crawford, J; Ustun, C. Plasmablastic lymphoma with small lymphocytic lymphoma: clinico-pathologic features, and review of the literature. Leuk Lymphoma 2008, 49(10), 1999–2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marvyin, K; Tjønnfjord, EB; Breland, UM; Tjønnfjord, GE. Transformation to plasmablastic lymphoma in CLL upon ibrutinib treatment. BMJ Case Rep. 2020, 13(9), e235816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Gender and age | HIV, EBV, HHV-8 | Diagnostic methods | Bone marrow involvement | FISH analysis (MYC rearrangements, bcl-2 and bcl-6) | Primary localisation | Therapy and outcome |

| Our case | Female, 46 yrs | Negative | PET, LN biopsy (HE, IHC), flow cytometry, ISH, FISH, NGS | N/A | MYC rearrangements | Concurrent diagnosis of CLL/SLL and PBL in same axillary LN | Dara-CHOP (6x), autologous bone marrow transplantation, Dara-CHOP (4x), daratumumab, ibrutinib |

| (Khanna et al., 2023) : 2 cases |

Case 1: Female, elderly patient |

Case 1: HIV others N/A | Case 1: BM biopsy (HE, IHC), flow cytometry, cytogenetic studies, FISH, transcriptome sequencing, PET | Consistent with CLL/SLL | Case 1: t (2;3) in CLL and PBL, MYC-IGH fusion t (8;14) and t (1;6) in PBL |

Case 1: 1 month, pleural fluid |

Case 1: daratumumab, R-CHOP -patient died, survilance N/A |

| (Ronchi et al., 2016) | Male, 61 yrs | Negative | Ultrasonography, axillary LN biopsy (HE, IHC), CT, PET, FISH | Both CLL/SLL and PBL | MYC gene rearrangement and translocation not documented | Concurrent diagnosis of CLL/SLL and PBL in same left supraclavicular LN | Hyper-C-PAD -patient died several months after initial diagnosis |

| (Martinez et al., 2012): 3 cases | Case 1: Male, 70 yrs | Negative | Biopsies (HE, IHC), ISH, cytogenetic analysis, FISH | Case 1: Yes | N/A |

Case 1: simultaneously, mesenteric LN | Case 1: R-CHOP (2x) -patient died 4 months after diagnosis |

| (Ramalingam et al., 2008) | Male, 42 yrs | HHV-8 positive | CT scan, MRI, mediastinal biopsy and BM (HE, IHC), flow cytometry, cytogenetic analysis | Yes | N/A | Concurrent diagnosis of CLL/SLL and PBL in bone marrow | High dose steroids, radiation of mediastinal mass, CHOP, hyper-CVAD, intrathecal cytarabine -patient died in 3 months |

| Reference | Gender and age | HIV, EBV, HHV-8 | Diagnostic methods | Bone marrow involvement | FISH analysis (MYC rearrangements, bcl-2 and bcl-6) | Time and localisation | Therapy and outcome |

| (Khanna et al., 2023): 2 cases | Case 2: elderly patient |

Case 2: EBV positive Others N/A |

Case 2: BM biopsy (HE, IHC), flow cytometry, PCR, CT scan | Consistent with CLL/SLL | Case 2: N/A | Case 2: Five years, pleural fluid |

Case 2: R-CHOP (1x), DA-R-Velcade EPOCH* patient died, survilance N/A |

| (Ramsey et al., 2023) | Male, 71 yrs | HIV N/A Others N/A |

BM biopsy, CT scan, LN biopsy, FISH, NGS | CLL/SLL | MYC rearrangement | 14 months, LN | CHOP (2x) -patient died after 4 months |

| (Marvyn et al., 2020) | Male, 53 yrs | HHV-8 Others N/A | LN and BM biopsies, genetic analysis, CT scan | Yes first CLL, later PBL | N/A | 7 years, bone marrow | COP regimen with added daratumumab from second cycle ** -patient died, survilance N/A |

| (Gasljevic et al., 2020) | Female, 74 yrs | HIV N/A, HHV-8 N/A | BM biopsy (HE, IHC), FISH, PCR, comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) | Yes CLL/SLL and later PBL |

No MYC rearrangements | 7 years cHL withmixed cellularity in inguinal LN but PBL in bone marrow | No therapy*** -patient died 2-3 weeks after LN biopsy |

| (Chan et al., 2017): 2 cases | Case 1: Male, 63 yrs Case 2: Male, 67 yrs |

Both cases: HIV N/A | BM and mass biopsy, FISH, NGS | Yes | N/A |

Case 1: 8 years, anal mass Case 2: 7 years, retroperitoneal LN |

Salvage chemotherapy -Case 1: patient died 2 weeks after PBL diagnosis -Case 2: patient died 12 weeks after PBL diagnosis |

| (Pan et al., 2013): 2 cases | Case 1: Male, 58 yrs Case 2: Male, 7 yrs |

Case 1: Negative Case 2: Negative |

LN and BM biopsy (HE, IHC), flow cytometry, cytogenetic studies, FISH, genetic studies | Case 1: Yes Case 2: Yes |

Case 1: CLL negative and PBL positive for MYC rearrangement Case 2: MYC rearrangement |

Case 1: 2 years, ulcerated mass at the gastroesophageal junction and bone marrow. Case 2: Diagnosed with low grade CD5+ LPD, after five years PBL left humerus |

Case 1: N/A -patient died after 3 months Case 2: localized radiotherapy and chemotherapy -patient stable |

| (Martinez et al., 2012) : 3 cases | Case 2: Male, 52 yrs Case 3: Female, 57 yrs |

EBV positive in case 2 | Biopsies (HE, IHC), ISH, cytogenetic analysis, FISH | Both cases: Yes | Case 2: N/A Case 3: N/A |

Case 2: 85 months, subcutaneous tissue Case 3:47 months, mandibula |

Case 2: R-CHOP (6x) -patient died 24 months after diagnosis of transformation Case 3: VAD (1x) and CHOP (3x) -patient died 6 months after diagnosis of transformation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).