1. Introduction

As space exploration advances from the near-Earth atmosphere into deep space, extreme conditions such as low pressure or vacuum, high temperature, and intense radiation impose stringent and quantitatively defined requirements on process control and equipment safety [

1,

2,

3]. Environmental humidity is particularly critical because it directly affects engineering risks including insulation failure, corrosion and aging, optical contamination, and thermal control malfunction. It therefore acts as a major disturbance that governs process consistency, material stability, and overall system reliability. Accurate monitoring of environmental humidity under extreme conditions is thus essential [

4]. However, variations in mass transfer and thermal convection, thermochemical degradation of devices and interface structures at elevated temperatures, and radiation induced disturbances to intrinsic material defects and electronic structures collectively intensify the hysteresis, drift, and aging observed in conventional humidity sensors. Achieving high sensitivity, fast response, long term stability, and strong repeatability in humidity detection under such extreme environments has consequently become a central scientific and engineering challenge [

5,

6,

7].

Chemical humidity sensors are the most widely used instruments for humidity detection. They operate by sensing variations in physical parameters resulting from the adsorption or absorption of water vapor molecules by a sensitive medium. Their performance is primarily determined by the properties and stability of the hygroscopic materials employed [

8,

9,

10]. However, under extreme environmental conditions such as low temperature, low pressure, and intense radiation, these sensors often suffer from major limitations, including sluggish response, elevated detection limits, increased signal drift, and reduced operational lifespan [

11,

12,

13]. Such drawbacks severely constrain their long-term stability in applications involving near-space missions, polar research, and deep space exploration. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop new chemical sensing materials capable of enhancing water vapor adsorption, transport, and signal conversion, thereby overcoming the performance bottlenecks of conventional devices under extreme conditions [

14,

15,

16].

In response to the degradation and failure mechanisms of humidity sensing performance under extreme environmental conditions, research since 2016 has proposed a range of adaptability-enhancement strategies at multiple levels, including material modification, structural design, and packaging processes [

8,

17,

18]. The number of related publications has shown a steady upward trend, and by 2025 nearly 479 studies had been reported in this field. To further illustrate this growing research activity,

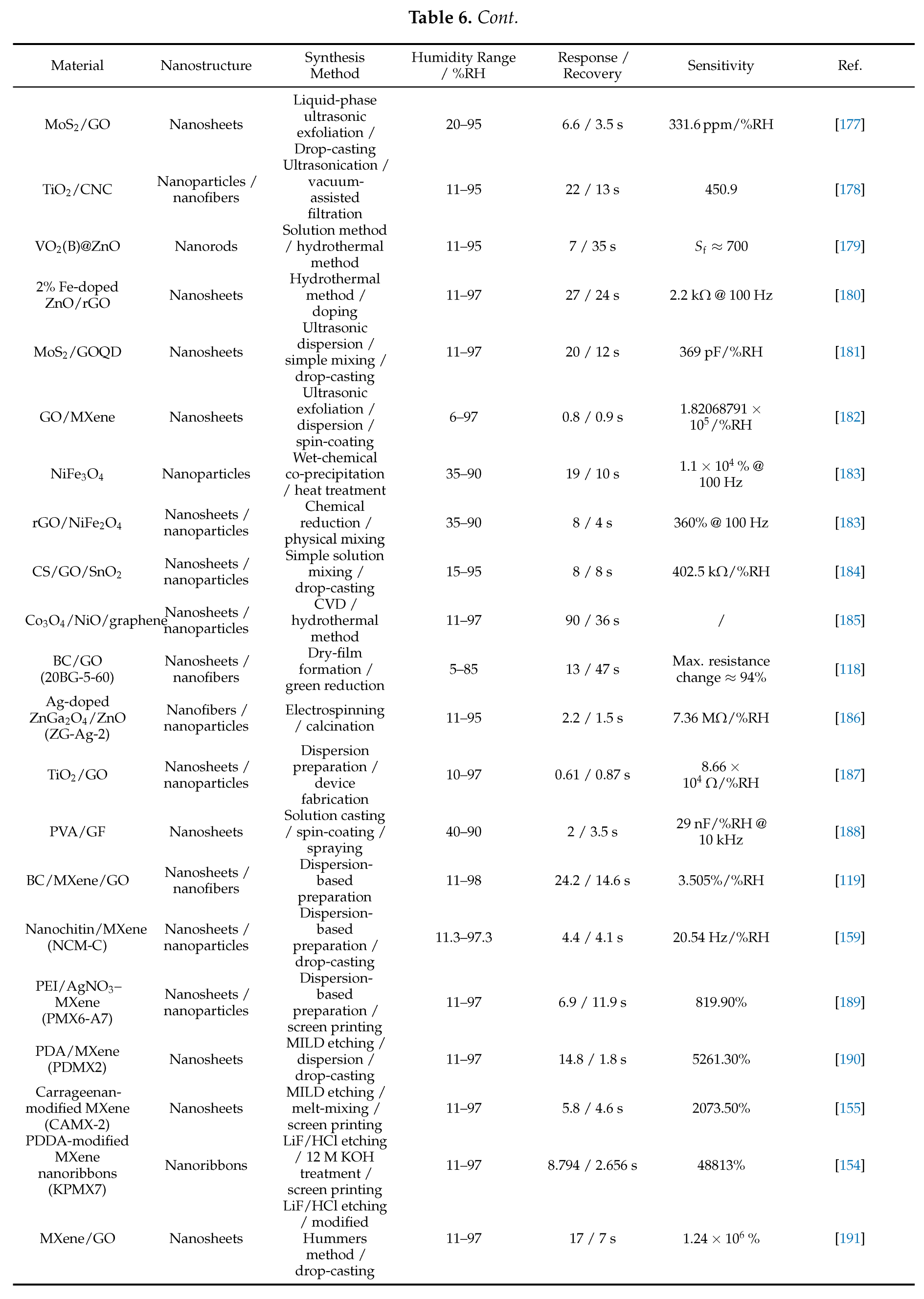

Figure 1 presents a bibliometric overview of publications from 2016 to 2025. As shown, the annual number of studies on extreme-environment humidity detection has increased continuously, while the distribution across major Research Areas, including Chemistry, Computer Science, Crystallography, Electrochemistry, and Energy & Fuels, highlights the interdisciplinary nature of current efforts. Notably, publications in the Chemistry category consistently represent the largest proportion, reflecting the material-oriented focus of most investigations. However, most existing studies focus on specific material types or individual sensing mechanisms, whereas systematic analyses addressing the combined impacts of extreme environmental factors remain relatively limited.

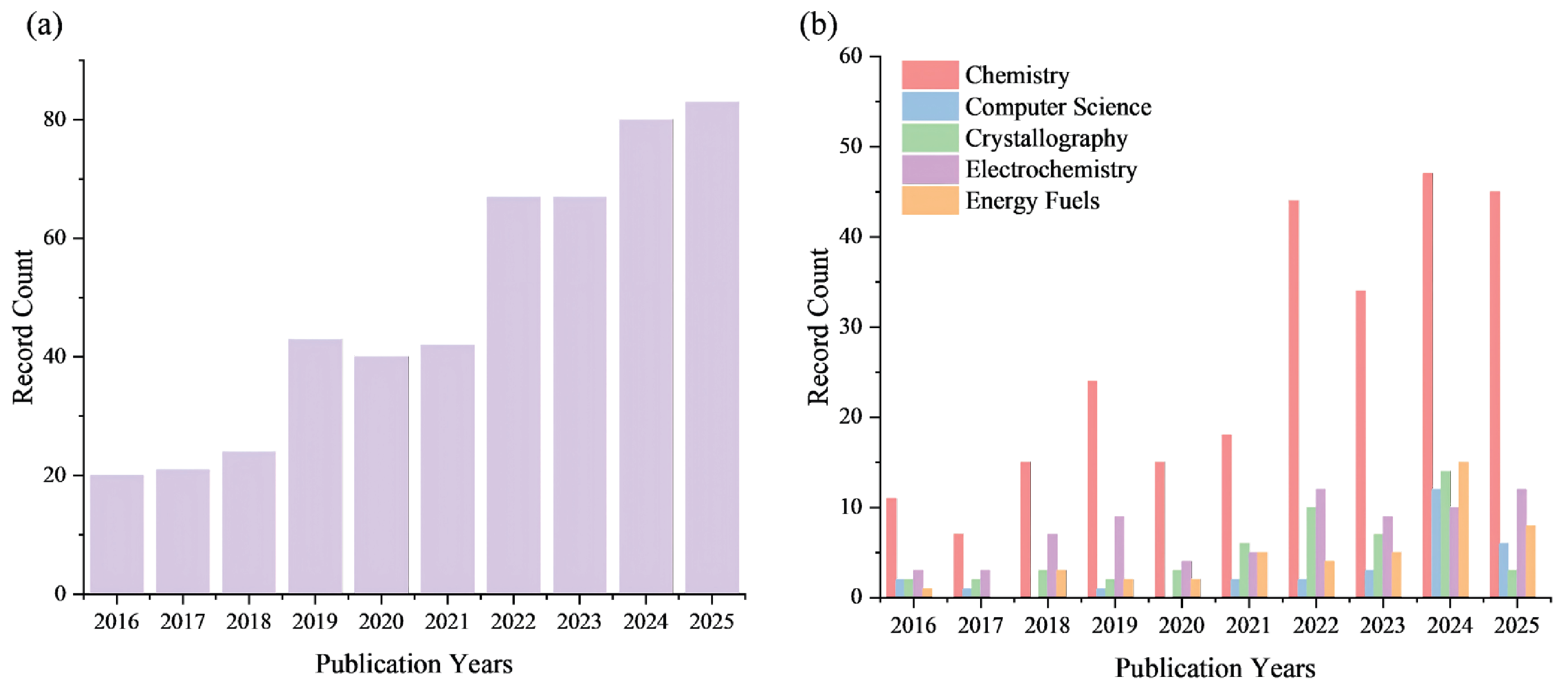

Against this background, the present paper reorganizes the current research landscape and mechanistic understanding of humidity sensing materials and devices, using environmental conditions as the central theme.

Figure 2 illustrates the overall framework adopted in this review, which encompasses three dimensions: humidity sensing mechanisms, classification of material types, and application environments. In contrast to traditional reviews organized by material category or sensing principle [

8,

10,

18,

19,

20], this paper systematically examines the response behaviors, failure characteristics, and adaptation mechanisms of various chemical humidity sensitive materials operating under extreme conditions. It also compares the advantages, limitations, and applicable ranges of different material systems.

The final section synthesizes the common patterns, key bottlenecks, and emerging trends associated with advanced humidity sensitive materials exposed to extreme environments. This provides a unified evaluation perspective and aims to establish a systematic and scalable reference paradigm for the design, performance assessment, and application expansion of humidity sensors in extreme settings. In doing so, it lays the groundwork for a paradigm shift in the field from material driven to system driven development.

2. Fundamentals and Performance of Chemical Sensing Materials

Given the stringent challenges that extreme conditions pose to humidity detection, this section describes the performance characteristics and adaptability of various humidity sensitive materials according to their material type. Based on differences in composition and structure, common humidity sensing materials can be classified into six primary categories: carbon-based materials, metal oxides, conductive polymers, insulating polymers, two-dimensional (2D) materials, and composite nanomaterials. Each material system exhibits distinct advantages and limitations when operating in low pressure or vacuum environments, high temperature conditions, and strong irradiation fields. This section introduces the materials whose electrical properties vary with humidity and illustrates these characteristics through representative examples.

2.1. Carbon-Based Materials: A High-Performance System Featuring Rapid Response and Tunable Microstructures

Carbon-based materials, characterized by their high specific surface area, hierarchical porosity, and tunable surface functional groups, rank among the fastest responding humidity sensitive materials within the low to medium humidity range. Their sensing mechanism primarily depends on the physical adsorption of water molecules at surface active sites and the resulting modulation of electrical conductivity [

21,

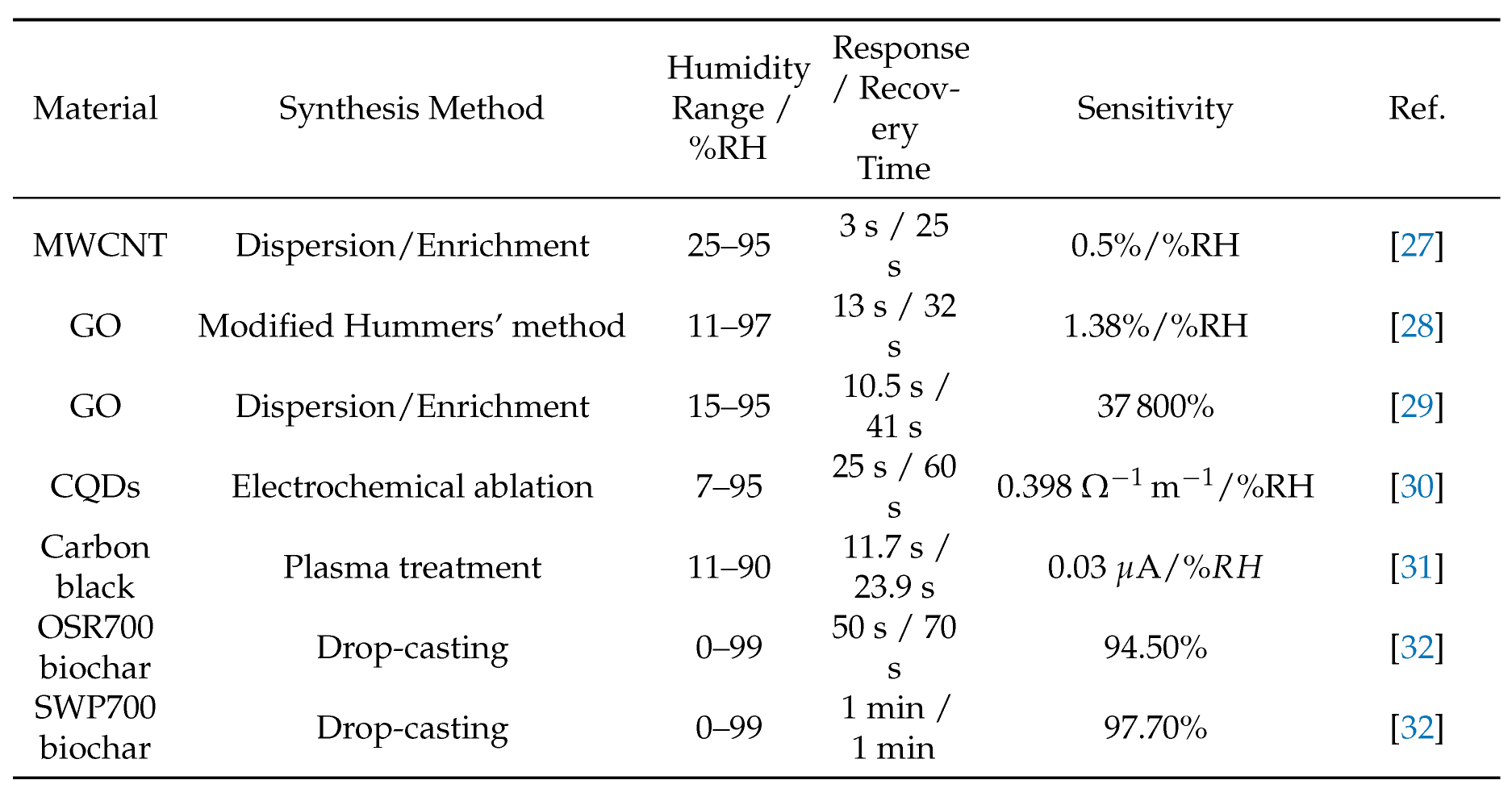

22]. However, challenges such as response hysteresis and reduced stability remain under extreme conditions, including high temperature and intense radiation. As summarized in

Table 1, single-component carbon-based materials exhibit notable limitations in sensitivity, stability, and response linearity under extreme humidity conditions, which restricts their applicability in harsh environments. Common carbon-based humidity sensitive materials include carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [

23], graphene oxide (GO) [

24], carbon black [

21], carbon quantum dots (CQDs) [

25], and biochar [

26]. Studies indicate that the conductive networks constructed from these materials retain strong stability even when exposed to high temperatures and ultraviolet radiation.

2.1.1. CNTs

CNTs have emerged as important humidity sensitive materials because of their high electrical conductivity, excellent chemical stability, and tunable surface structures. Numerous studies have enhanced their performance under low pressure, high temperature, and strong radiation conditions through diverse composite and surface modification strategies. CNTs have emerged as important humidity-sensitive materials because of their high electrical conductivity, excellent chemical stability, and tunable surface structures. In addition to their intrinsic advantages, the fabrication and sensing behavior of CNT–cellulose hybrid structures have also been systematically demonstrated by Oya et al. [

33], who developed a CNT composite paper prepared by mixing CNT and pulp dispersions, filtering the slurry through a fine mesh, and heat-pressing the resulting sheet. As shown in

Figure 3, the humidity response of this composite originates from moisture-induced swelling of cellulose fibers, which perturbs the CNT percolation network and leads to measurable resistance changes. Both the static and dynamic humidity-sensing characteristics of this paper-based CNT system further highlight the versatility of CNTs when incorporated into deformable or porous substrates.

Beyond CNT–cellulose architectures, numerous studies have enhanced CNT-based humidity sensing performance under low pressure, high temperature, and radiation-intensive conditions through diverse composite and surface modification strategies. For example, Al Hamry et al. [

34] fabricated a humidity sensing film by combining GO with multiwalled nanotubes (MWNTs) and applying laser writing to the composite. The incorporation of MWNTs improved both the conductive pathways and structural robustness, allowing the sensor to maintain long term repeatability with response/recovery times of 10.7 s and 9.3 s under high humidity and high pressure, while exhibiting reduced hysteresis and aging relative to pure GO films. Wang et al. [

35] developed a ternary composite film composed of hydroxylated MWCNTs, GO, and nafion. The sulfonic acid groups in nafion and the hydroxyl groups on the nanotubes acted synergistically to enhance water adsorption, which significantly increased capacitance sensitivity, reaching 547 kHz/%relative humidity (RH), and improved long term stability for use in sealed or wireless systems. Hu et al. [

36] designed a layer-by-layer self-assembled MXene/SWCNTs composite film in which carboxyl-functionalized SWCNTs act as interlayer spacers to expand the MXene lamellar structure and introduce additional hydrophilic sites. This structural modulation effectively accelerates both the adsorption and desorption of water molecules, enabling a rapid response and recovery of 2 s and 1.75 s, respectively, even under high-humidity and fluctuating-temperature conditions. Chen et al. [

37] enhanced the performance of a flexible non-contact humidity sensor by constructing a graphene nanoflakes (GNPs) and MWCNTs conductive network. This design enabled rapid recovery within 0.5 s during periodic respiration and low-pressure airflow, supporting its feasibility in rarefied and vacuum conditions. Al-Kadhim et al. [

38] proposed a three-electrode ion humidity sensor with CNTs that utilizes high field ionization to detect trace water vapor in low pressure and vacuum environments. The device achieved a sensitivity of 11.83%RH to the power of negative one and response/recovery times of 11 s and 5 s, offering a promising approach for aerospace vacuum monitoring. Furthermore, Suman et al. [

39] evaluated the radiation stability of functionalized and Cu-plated SWCNTs and poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) thin films. The devices retained normal sensing capability after exposure to 1000 krad X ray irradiation, highlighting the radiation resistance of nanotube-based networks. A GO, hydroxylated CNT, and Nafion sensor integrated with a wireless inductive coupling method also maintained stable readout under electromagnetic interference and temperature fluctuations.

2.1.2. GO

GO offer distinct advantages for humidity sensing under extreme conditions because of its high specific surface area and abundant, tunable oxygen containing functional groups. Recent research has focused on enhancing its humidity sensing performance through chemical modification and composite engineering. For example, mild alkaline treatment of GO improves electrical conductivity while preserving hydrophilic groups [

40]. The resulting flexible sensing membrane exhibits very high sensitivity from dry conditions to high humidity near 80% RH, with impedance decreasing by several orders of magnitude as humidity increases, and demonstrates rapid and reversible response behavior. However, some hysteresis and slow recovery persist in low humidity environments. Another study functionalized reduced graphene oxide (rGO) with 1,3,5-phenyltricarboxylic acid (H3BTC-rGO) and incorporated Ag (H3BTC-rGO) nanoclusters through in situ reduction to produce a highly sensitive and low hysteresis flexible humidity sensor [

41]. This composite provides abundant hydrophilic active sites together with an efficient conductive network, enabling excellent performance across the entire range of 0 to 100% RH. The sensor maintains high sensitivity in both extremely dry conditions and high humidity regions, exhibits a low hysteresis of plus or minus 5% RH, and features second level response and recovery along with strong long-term stability and repeatability. In addition, an ultrathin, wearable sensing membrane produced through layer-by-layer assembly and thermal reduction of rGO and silk fibroin (SF) offers simultaneous humidity and temperature detection [

42]. The incorporation of SF substantially enhances the mechanical flexibility of the rGO film, more than doubling its elastic modulus, which allows stable operation under repeated bending and combined temperature and humidity cycling. This highly sensitive device can capture minute fluctuations in temperature and humidity generated by skin contact or respiration in real time, providing a reliable platform for monitoring physiological signals in dynamic and extreme environments.

2.1.3. Carbon Black

Carbon black is a low-cost conductive filler widely employed in humidity sensors to establish conductive networks. However, it readily saturates under medium to high humidity conditions, which limits its sensitivity and dynamic response. To overcome this limitation, researchers have developed energy self-supply designs and composite material strategies. In one study, a low cost and flexible humidity sensor was fabricated by screen printing a graphene-polypyrrole (PPy) -carbon black ink onto a paper substrate [

43]. The device achieved a resistive sensitivity of approximately 12.2

/% RH within the range of 23 to 92.7% RH and demonstrated strong flexibility and stability, with no significant degradation after fifty humidity cycles. Its response/recovery times were about 5 s and 7 s, respectively, which is sufficient for respiratory monitoring. The sensor also showed high repeatability, with deviations between devices limited to plus or minus 1 ohm/% RH. In addition to wearable applications, this paper-based sensor is suitable for environmental and soil moisture monitoring. Another study combined water-soluble gelatin with carbon black nanoparticles to deposit a nanoscale thin film onto interdigitated electrodes, forming a humidity sensitive composite layer [

44]. This gelatin and carbon black film effectively detected humidity in the range of 20.3 to 83.2% RH and exhibited a linear response between 20 and 65.2% RH with a sensitivity of about 0.35 millivolts/% RH and good repeatability. The response and recovery times were both under 10 s.

A further advancement involved the development of a self-powered humidity sensor based on a porous carbon black film loaded with lithium bromide (LiBr) electrolyte [

31]. Flame processed porous carbon black served as the substrate, providing a three-dimensional (3D) pore structure for the orderly adsorption and desorption of water vapor by the electrolyte. When paired with Cu and Al electrodes, the system enabled humidity detection without the need for external power. The sensor exhibited a rapid response time of approximately 11.7 s and a recovery time of about 23.9 s. Air plasma treatment generated an ultrathin hydrophilic layer on the carbon black surface, which further enhanced humidity sensing performance. The flexible device generated electrical signals through humidity induced electrolyte ionization and redox reactions at the electrodes, enabling entirely self-powered operation. These sensors have been demonstrated in applications such as respiratory monitoring, contactless switching, silent speech recognition, and diaper wetness detection, highlighting their versatility for wearable technologies and extreme environment sensing.

2.1.4. CQDs

In recent years, carbon-based nanomaterials have demonstrated significant potential for humidity sensing under extreme environmental conditions. Among them, sensing strategies employing CQDs as active materials have attracted considerable attention. Huang et al. [

45] developed a flexible, self-powered humidity sensor based on porous P(VDF–HFP) films modified with hydrophilic CQDs. The CDs not only introduced abundant -OH/-COOH/-NH

2 surface groups that promoted water adsorption, but also induced a significant increase in the

-phase content of the polymer matrix, thereby enhancing both humidity sensitivity and piezoelectric output. The incorporation of CDs transformed the originally hydrophobic P(VDF–HFP) film (PC0) into a more hydrophilic surface (PC1/PC2), reducing the water contact angle from 126.3° to as low as 65.1° and suppressing humidity hysteresis. Furthermore, the schematic humidity–interaction model illustrates how moderate hydrophilicity enables reversible adsorption/desorption of water molecules, leading to an almost linear and highly sensitive voltage response across fluctuating humidity conditions. This design strategy demonstrates a promising route toward self-powered humidity sensing under extreme environmental variations. Qin et al. [

25] fabricated a CQDs-based humidity sensor for self-powered respiration monitoring. Owing to the abundance of hydrophilic groups in pure CQDs films, water molecules can be efficiently adsorbed and form conductive water chains, leading to a substantial decrease in resistance. The relative electrical signal response reaches 5318% at 94% RH and remains stable across a wide humidity range of 11 to 94% RH. The sensing mechanism involves water vapor molecules being captured by surface functional groups on the CQDs and transported via a proton-hopping (Grotthuss) mechanism, thereby greatly enhancing humidity sensitivity. When integrated with a respiration-driven triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG), the sensor enables real-time respiration monitoring without the need for an external power source, making it particularly suitable for harsh environments lacking conventional energy supplies. Morsy et al. [

46] proposed a graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4)/GQD composite humidity sensor. The layered structure of g-C3N4 effectively prevents GQDs-agglomeration and increases the specific surface area, providing abundant active sites for water vapor adsorption. Adsorbed water molecules dissociate under the influence of hydroxyl groups on the GQDs surface, generating hydrated hydrogen ions that migrate via chain proton hopping. The device exhibits a rapid, linear, and reversible humidity response over the range of 7 to 97% RH. Owing to the excellent thermal stability of g-C3N4 and the anti-interference characteristics of the composite, the sensor maintains reliable performance under extreme conditions such as high temperature and irradiation.

2.1.5. Biochar

Biochar, a sustainable, low-cost, and porous carbon-based material, has demonstrated substantial potential for humidity sensing in recent years. Numerous studies have enhanced the performance of biochar-based sensors in extreme environments through material modification and composite design strategies. For example, Fiori et al. [

47] produced black liquor-derived biochar (BH) from paper industry waste and dispersed it into a stable nanofilm using ultrasonic exfoliation. This nanofilm was directly coated onto a recycled paper substrate to create a fully biodegradable humidity sensor. The resulting device not only aligns with the principles of the circular economy but also exhibits excellent flexibility and humidity responsiveness, demonstrating strong adaptability in compact or complex environments. In another study, researchers incorporated 10 wt.% activated kitchen-waste-derived biochar into an Fe-BDC metal–organic framework (MOF) to synthesize an Fe-BDC@BC composite [

48]. This composite improved the material’s specific surface area, crystallinity, and thermal stability while simultaneously optimizing its electronic properties by reducing the band gap and enhancing electrical conductivity. Humidity response tests revealed rapid sensing capability across a wide relative humidity range (10-95% RH), with a signal change of up to 96% and response and recovery times of 10 s and 50 s, respectively, indicating excellent dynamic performance and sensitivity. More importantly, the MOF–-biochar composite structure remains stable at elevated temperatures [

32], significantly enhancing sensor reliability in extreme environments such as high thermal loads and radiation exposure. Furthermore, Ziegler et al. employed a PVP polymer binder to fabricate humidity-sensing films using two commercial biochar materials (SWP700 and OSR700), forming an n-p heterojunction structure. At low humidity levels (5% RH), the composite films exhibit a pronounced increase in impedance. Compared with pure biochar films, which are prone to peeling, the incorporation of PVP markedly improves film adhesion and structural integrity. The material provides rapid response across a broad humidity range (5-100% RH) at room temperature, with a response time of approximately 1 min and a reasonable recovery time. In addition, it demonstrates strong resistance to interference from gases such as ozone, methane, and carbon dioxide.

2.2. Metal Oxides: A Core Material System for Extreme Environments

Metal oxides, owing to their outstanding chemical inertness, thermal stability, and radiation resistance, are among the most widely used humidity-sensing materials for extreme environments [

17,

49,

50]. In high-temperature or corrosive conditions, they retain stable crystal structures and surface-active sites, thereby ensuring consistent water adsorption behavior. Their fundamental humidity-sensing mechanism arises from reversible changes in electrical properties during water adsorption and desorption. As relative humidity increases, a chemisorbed monolayer first forms on the surface, which gradually transitions into a physisorbed multilayer and ultimately develops into a continuous water film [

51]. Throughout this process, n-type semiconductors exhibit decreased resistance due to an increase in electron concentration, whereas p-type semiconductors display increased resistance as hole concentration decreases.

For dielectric insulating oxides, the incorporation of water molecules with high dielectric constants leads to an enhanced equivalent dielectric constant and, consequently, increased capacitance. These evolutionary processes are clearly reflected in impedance spectroscopy and frequency-domain responses [

52,

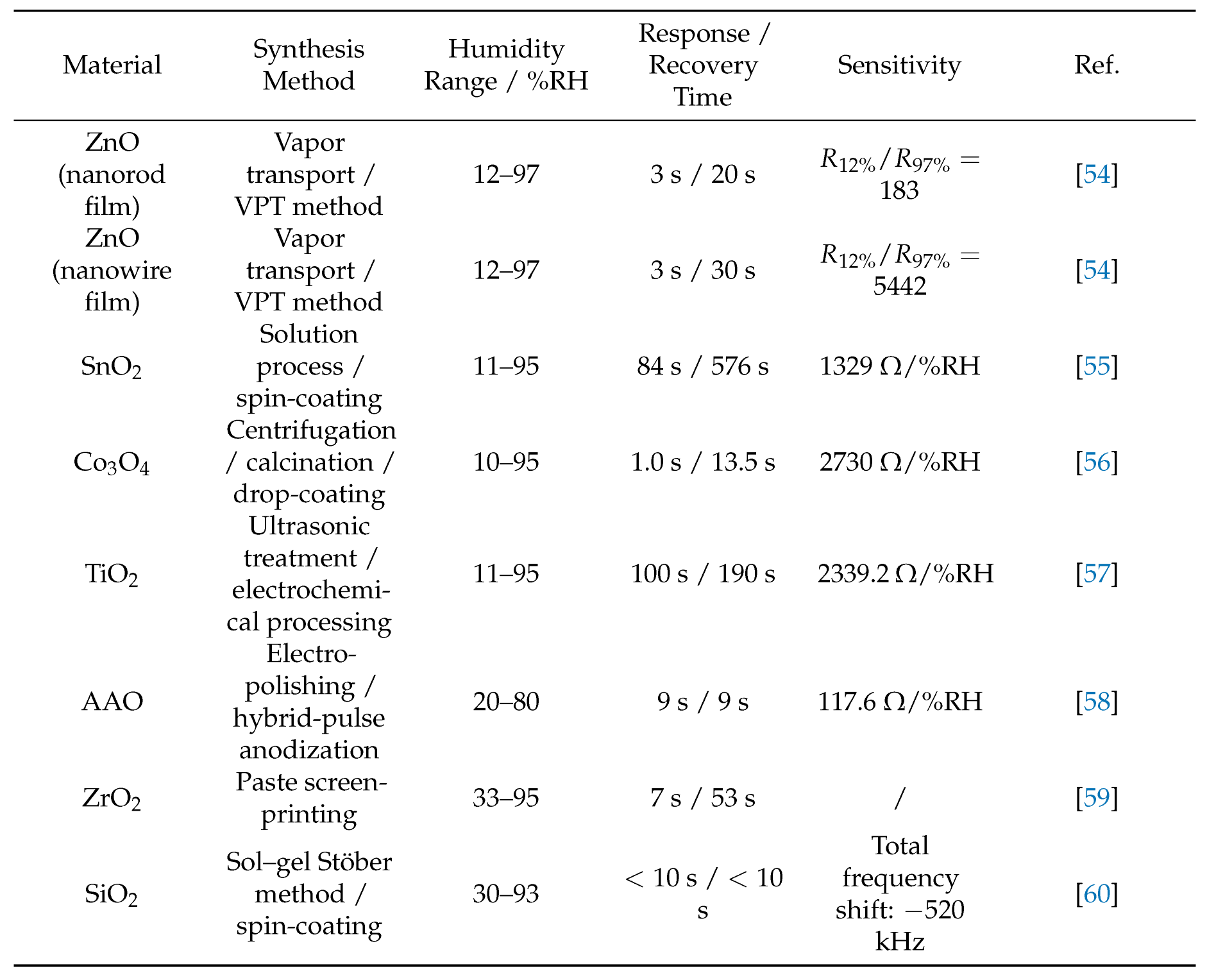

53]. However, as summarized in

Table 2, most single-component metal oxides still exhibit limited sensitivity or slow recovery under extreme humidity conditions, reflecting the intrinsic constraints of non-composite systems. Therefore, optimizing electronic and ionic conduction through precise control of surface defects, ion doping, and micro/nanostructures is essential for improving the overall sensing performance.

2.2.1. ZnO

Among n-type metal oxides,

is widely used for humidity sensing owing to its wide bandgap (3.3–3.4 eV), wurtzite structure, and excellent thermal and chemical stability. However, conventional dense

thin films often show limited sensitivity and slow response under extreme conditions. To address this, Park et al. [

61] developed a self-bridging ZnO nanowire array through simple thermal annealing, enabling a deposited Zn layer to convert into a highly crystalline, interconnected nanowire network. The resulting sensor demonstrated high resistive sensitivity down to 1.73% RH and rapid, reversible switching (35.3 s response; 32.6 s recovery). Rare-earth ion doping has also proven effective in increasing defect-rich adsorption sites and enhancing responsiveness. Zhang et al. [

62] synthesized oxygen-vacancy–rich black ZnO doped with 3%

, achieving resistance changes of over three orders of magnitude across 11–95% RH with minimal hysteresis and response/recovery times of 32.3 s and 39.6 s. Similarly, Akççay et al. [

63] introduced low concentrations of

into ZnO films via a sol–gel method, generating nanoporous hexagonal structures that promoted water adsorption. The optimized 3 mol%

-doped sensor exhibited a nearly 245-fold sensitivity enhancement and ultrafast response/recovery times of 1.0 s and 5.5 s at low humidity. Collectively, these studies demonstrate that nanostructuring and rare-earth doping substantially improve sensitivity, defect-mediated adsorption, and dynamic performance in ZnO-based humidity sensors.

To further highlight the advantages of composite nanostructures, Priyadharshini et al. [

64] presents representative data for a GO–Mn-doped ZnO (GOZnMnO) humidity sensor. The incorporation of Mn-modified ZnO domains into GO sheets creates abundant oxygen-rich active sites and defect-assisted pathways, enabling fast, repeatable capacitance responses and significantly shorter response/recovery times compared with pristine GO or undoped ZnMnO. Moreover, the resistance-based sensitivity profile shows excellent linearity and a markedly steeper slope, demonstrating how nanocomposite engineering and optimized electrode geometry synergistically enhance humidity-sensing performance (

Figure 4).

2.2.2.

has also attracted substantial attention in recent years. As a typical wide-bandgap n-type semiconductor with strong redox surface activity and excellent high-temperature stability,

is widely employed in gas and humidity sensing, particularly in high-temperature, low-pressure, and radiation-intensive environments. Traditional

sensing mechanisms rely on oxidative adsorption, which leads to performance degradation under vacuum conditions [

65]. Introducing nanoscale defect structures offers an effective solution to this limitation. Recent studies have demonstrated that impedance-type humidity sensors based on

quantum dots can operate stably at pressures as low as 5 mbar [

66]. Their high specific surface area (

60 m

2/g) and abundant oxygen vacancies enable sustained moisture adsorption even in vacuum, highlighting the potential of

for humidity monitoring in aerospace and semiconductor vacuum environments. In addition, constructing p–n heterojunctions or forming composites with conductive polymers can significantly enhance the sensitivity and stability of

. For example, integrating

with PEDOT:PSS to form a p–n heterojunction improves charge separation and transport efficiency, yielding a device sensitivity of 85.7% and rapid response/recovery times of 14 s and 7 s [

67], respectively. Moreover, doping with Ag, Al, or rare-earth elements can further shorten the response time to the 5–10 s range, an effect particularly beneficial in low-humidity or high-temperature conditions. Other studies have revealed that

exhibits strong stability under ultraviolet and gamma irradiation. Kajal et al. [

68] found that gamma irradiation (75–200 kGy) introduces oxygen vacancies, enhancing the conductivity of

films and reducing the bandgap from 3.8 eV to 3.4 eV. These changes improve sensitivity under irradiation and promote surface charge migration, thereby accelerating response in high-humidity environments and enabling

sensors to maintain stable performance under intense radiation or in outer space.

2.2.3.

is a representative p-type spinel oxide characterized by high chemical stability and strong electrochemical activity. Its excellent thermal stability and reversible redox behavior make it a promising candidate for high-reliability humidity sensing in extreme environments. In conditions such as high-temperature flue gas or intense solar radiation, the ceramic-like thermal resistance of

reaching up to 800 °C enables long-term stable operation. Nanostructuring further mitigates thermal strain and suppresses crack formation, thereby preserving a linear sensing response. In addition, the p-type conduction mechanism of

behaves oppositely to radiation-induced carrier variations, facilitating signal discrimination under irradiation and enhancing anti-interference performance. Despite these advantages, the high thermal stability of

also imposes limitations: conventional

-based sensors typically require operating temperatures above 200°C to achieve adequate humidity sensitivity. To address this challenge, recent studies have explored composite conductive materials and ionomer integration strategies to enable high-sensitivity detection at room temperature. Seekaew et al. [

69] fabricated flexible humidity-sensitive films based on p-type

/p-type

heterojunction nanoparticles, achieving a positive humidity response of approximately 456% over the 10–95% RH range, with excellent linearity, low hysteresis (<5% RH), and good cycling stability. Through composite engineering and interface functionalization,

-based systems have been transformed from temperature-dependent oxide sensors into robust room-temperature humidity detectors. Andre et al. [

70] demonstrated that

–

heterostructured nanofibers modified with

exhibited markedly enhanced humidity-sensing performance, including a large and nearly linear resistance variation across 25–75% RH, rapid response within 5 s, and excellent cycling repeatability.

2.2.4.

The diverse phase structures and tunable morphologies of

have opened new avenues for advanced humidity sensing.

, one of the most widely utilized metal oxides, possesses a bandgap of 3.2 eV along with excellent chemical and thermal stability. Its high mechanical strength and strong chemical inertness make it a highly suitable candidate for humidity sensing in high-temperature or corrosive environments [

71]. Previous studies have demonstrated that

ceramic capacitive sensors can operate stably from room temperature to 320°C [

72]. Impedance analysis further reveals that the

surface undergoes a transition from dielectric to conductive behavior at elevated temperatures, enabling sensitive detection even under low-humidity, high-temperature conditions. These features give

notable advantages in applications such as drying ovens, combustion engines, and geothermal systems. In addition, nanoscale engineering has been employed to enhance the surface activity of

. For example, Ghadiry et al. [

73] developed an optical waveguide humidity sensor using nano-anatase

, achieving a substantial light-intensity variation of 14 dB over the 35–98% RH range with an ultrafast response time of 0.7 s. The sensor also demonstrated excellent tolerance and reversibility under UV exposure, indicating strong suitability for real-time monitoring in radiation-intense environments such as nuclear energy and aerospace systems. Tong et al. [

74] further improved the performance of

by integrating

nanoparticles with cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) to fabricate a flexible thin-film sensor. The device offered a wide detection range of 11–97% RH, response and recovery times of approximately 34 s and 18 s, respectively, and stable operation for more than 30 days under repeated bending. This composite system effectively combines the inherent stability of

with the strong hygroscopicity of CNC, making it well suited for extreme environments involving high temperatures, mechanical vibrations, or wearable applications.

2.2.5. Insulating Metal Oxides

Insulating metal oxides (e.g.,

,

, and

) are widely employed in capacitive humidity sensors. Although they lack free charge carriers, their exceptional thermochemical stability and strong water-adsorption capacity provide irreplaceable advantages under high-temperature, highly corrosive, and high-radiation environments [

75]. Recent studies further show that the response and recovery times of anodic-aluminum-oxide (AAO) sensors can be reduced to the order of seconds under high-frequency operation [

76], while maintaining excellent linearity in the ranges of 40-70% RH and 60-90% RH. Chung et al. [

77] fabricated low-cost AAO thin films via one-step anodic oxidation, achieving a sensor with a response exceeding 5000% over a 16

area and response/recovery times of only 9 s. The thin oxide layer shortens the diffusion pathway, markedly enhancing the response rate. This material also exhibits long-term stability under elevated temperatures and vacuum conditions.

2.3. Conducting Polymers: Advantages of Structural Order and Conduction Coupling

Conducting polymers (CPs) have long been central to humidity-sensing research owing to their intrinsic conductivity, mechanical flexibility, and excellent processability [

78]. Their sensing behavior is mainly governed by two mechanisms: (i) water adsorption alters the doping level and carrier concentration, modulating electrical conductivity [

10,

79]; and (ii) moisture absorption induces polymer swelling or network reconstruction, changing conductive pathways or interfacial barriers [

80,

81]. These attributes provide semiconductor-like tunability while enabling seamless integration into flexible and wearable systems [

82]. However, CP-based humidity sensors face notable limitations under extreme conditions: high temperatures may cause dopant loss and chain scission [

83], low temperatures can result in water freezing and suppressed ion transport [

84], ionizing radiation may induce chain breakage or cross-linking [

85], and vacuum environments can destabilize polymer structures [

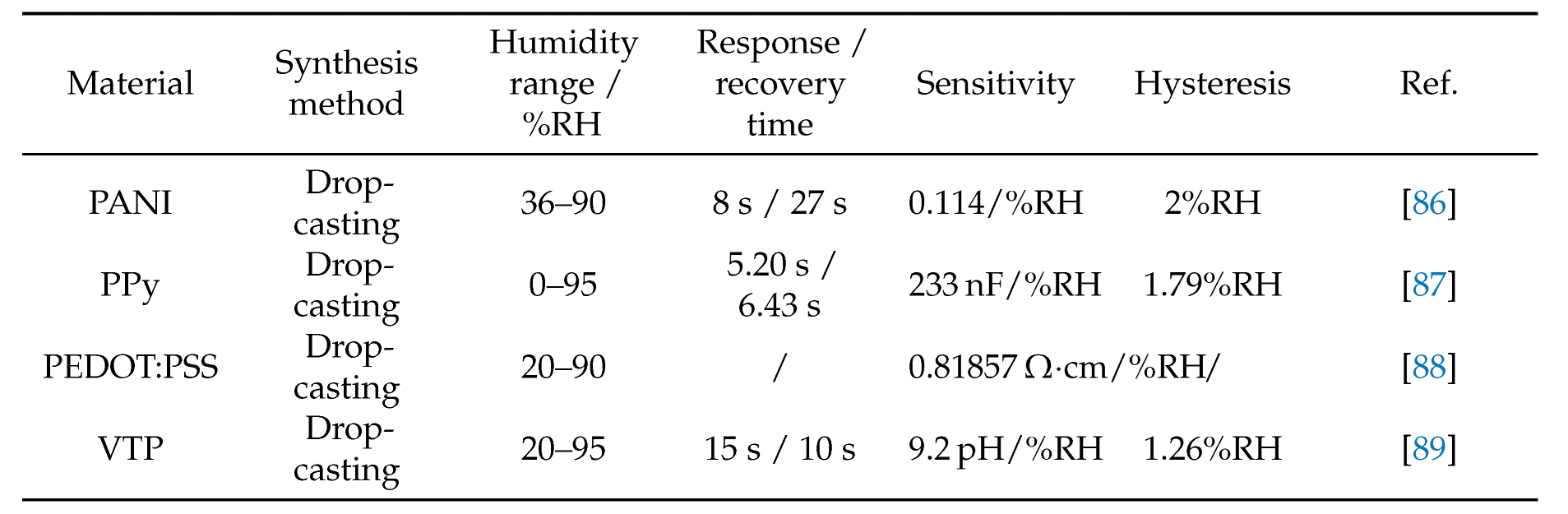

66]. As reflected in

Table 3, single-component CPs often exhibit hysteresis, limited stability, and reduced sensitivity at very low or high relative humidity. Recent advances in composite engineering, surface functionalization, and structural optimization have significantly improved the robustness and usability of CP-based humidity sensors for extreme-environment applications.

2.3.1. PANI

PANI, a representative conducting polymer, has received extensive attention in humidity-sensing research owing to its simple synthesis, environmental stability, and reversible proton doping/dedoping behavior. Unlike conventional inorganic humidity-sensing materials that typically require elevated operating temperatures, PANI-based sensors function efficiently at room temperature with low power consumption, making them suitable for humidity monitoring in specialized or constrained environments. In extreme conditions, PANI and its modified derivatives exhibit remarkable adaptability and performance advantages. Experiments conducted at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) demonstrated that a polymer humidity sensor placed in a cryogenic chamber at -20°C and near 0% RH [

13], and exposed to high-flux proton irradiation (approximately

protons

accumulated over 33 days), was still able to generate reliable humidity alarm signals, confirming its survivability under intense irradiation. Although the study employed commercial polymer-based capacitive elements, the findings suggest that well-encapsulated conductive-polymer sensors are promising candidates for use in the harsh radiation environments encountered in space. Moreover, the long-term stability and anti-interference capability of PANI-based sensors have been widely documented. Nanocomposite-enhanced PANI sensors often demonstrate excellent cyclic repeatability and low hysteresis. For instance, the response curves of a PANI/1% Cu-ZnS porous microsphere sensor nearly overlapped during cyclic testing [

90], indicating outstanding repeatability. In terms of cross-sensitivity, pure PANI may respond to polar species such as ammonia, but appropriate composite design can significantly improve selectivity. Studies on a GO/PANI sensing film reported minor responses to interfering gases such as methane, ethanol, and benzene under high humidity, while showing negligible sensitivity to common impurities including

, formaldehyde, and acetone [

91,

92,

93]. These results indicate that PANI-based sensors possess inherent anti-interference capability in complex real-world atmospheres, especially when material composition and interfacial structures are optimized.

2.3.2. PPy

PPy is a versatile conducting polymer with advantages comparable to PANI, including simple synthesis, low cost, light weight, flexibility, and good electrochemical reversibility. Its rapid humidity response, minimal hysteresis, and strong environmental stability make it suitable for demanding applications. Under complex or harsh conditions, PPy-based sensors can operate across wide temperature and pressure ranges, enabling humidity monitoring in confined or low-pressure environments such as spacecraft and deep-space probes. PPy films can even detect trace water vapor under vacuum. The thermal stability of PPy composites is further enhanced by incorporating inorganic components [

94]; for instance,

, with its high melting point (1870°C) and chemical inertness [

95], provides partial thermal protection and structural reinforcement, allowing PPy/

films to outperform pure PPy at elevated temperatures. Such robustness is essential for applications in mines, blast furnaces, and other high-temperature industrial environments. PPy-based sensors also show potential resistance to radiation: the conjugated polymer backbone offers tolerance to radiation-induced chain scission [

13], while inorganic phases such as

remain unaffected by ionizing radiation and may dissipate part of the energy. Consequently, PPy/metal oxide composites are expected to exhibit higher radiation stability than fully organic sensing materials.

Although pristine PPy films inherently suffer from limited moisture uptake and thus require structural or compositional modification, a variety of PPy-based hybrid architectures have been developed to overcome these limitations. As an illustrative example, Ni et al. [

96] reported a PPy@lignocellulosic slurry/CMC composite that significantly enhances environmental stability and humidity-responsive conductivity (

Figure 5). The schematic in

Figure 5(a) shows the integration of PPy with a DES-derived lignocellulosic scaffold and CMC binder, while

Figure 5(c)–(f) demonstrate improved conductivity switching between dry and wet states and enhanced antioxidant stability, confirming the effectiveness of structural modification in elevating PPy-based humidity sensing performance.

2.3.3. PEDOT:PSS

As a humidity-sensitive material, PEDOT:PSS is prone to degradation under high humidity because the acidic and strongly hygroscopic PSS component can corrode electrodes, swell, and generate interfacial defects that introduce carrier-trapping sites. Near saturation, excessive water uptake leads to signal saturation and slow recovery, highlighting the need for material and interfacial engineering. Two primary strategies have been widely adopted: (i) chemical treatments or cross-linkers that partially remove or neutralize PSS, and (ii) composite engineering with nanomaterials to improve sensitivity and environmental stability [

97].

Despite these limitations, PEDOT:PSS-based sensors offer important advantages for extreme environments, including mechanical flexibility, scalable processing, and strong structural robustness. Devices printed on PET substrates—such as PEDOT:PSS/PEO and PEDOT:PSS/MXene, exhibit negligible performance loss after repeated bending and extended aging [

98]. Cross-linked films also maintain stable operation over broad RH and temperature ranges, remaining functional after long exposure to 80% RH at 40°C [

99]. For harsher conditions, including temperatures above 100°C or high radiation flux, PSS-free PEDOT structures or encapsulation layers can provide improved durability. Although radiation data for PEDOT:PSS remain limited, polymer-based humidity sensors operating under fluences up to

suggest that appropriately protected PEDOT:PSS devices may be suitable for space or nuclear applications. In addition, PEDOT:PSS offers good selectivity, as its humidity response, such as in PEDOT:PSS/MXene composites, arises mainly from water adsorption and is minimally affected by

,

, or VOCs [

100].

2.4. Insulating Polymers: Interfacial Modification and Moisture Regulation Mechanisms

Compared with conducting polymers, insulating or low-conductivity polymers also play a significant role in humidity sensing. These materials typically serve as dielectric or electrolyte layers in capacitive and impedance sensors, where variations in dielectric constant, ionic conductivity, or structural dimensions arise from the adsorption and desorption of water vapor [

10,

82]. Representative examples include polyimide (PI), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), cellulose and its derivatives, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), and polyamides (PA) [

101,

102,

103,

104,

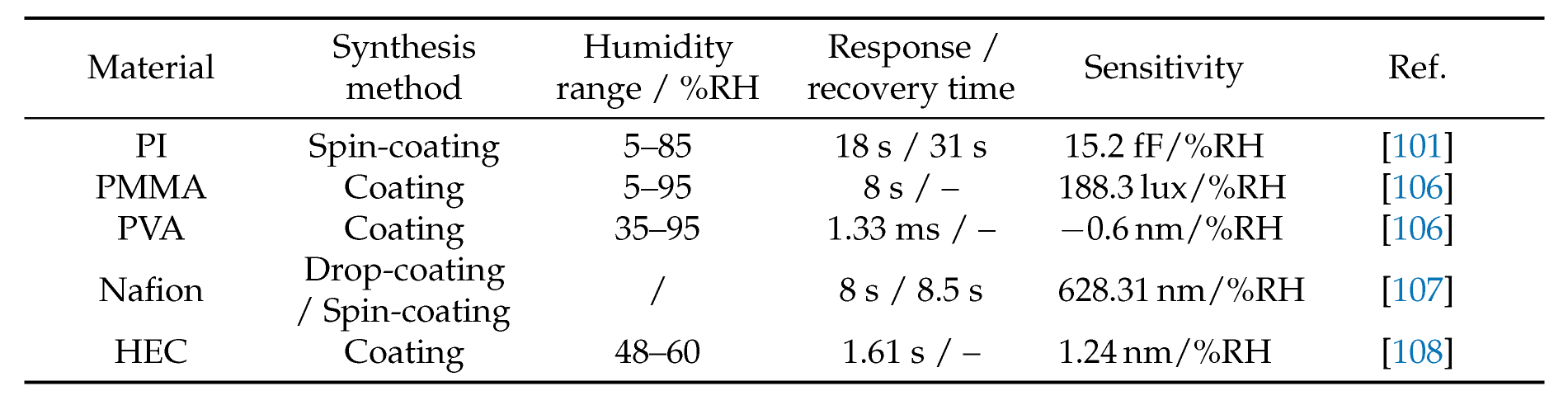

105] Owing to their excellent film-forming ability, tunable hydrophilic functional groups, and high environmental stability, these polymers have garnered increasing attention for humidity detection under extreme environmental conditions in recent years. An overview of their representative sensing performances is presented in

Table 4, providing a clearer picture of how single-component insulating polymers behave across different humidity regimes.

2.4.1. PI

PI is widely regarded as an ideal material for humidity sensing owing to its outstanding thermal stability, chemical resistance, and ability to retain performance under extreme conditions [

109,

110]. To further enhance its sensitivity and response speed, various innovative modification strategies have been explored. For example, one study employed a partially fluorinated ultrathin PI sensing film (approximately 100 nm thick) sandwiched between top and bottom electrodes, with MWCNTs serving as a gas-permeable top electrode [

111]. This design reduced the sensor’s response time to the millisecond scale (

). In addition, integrating PI with inorganic nanomaterials has proven to be an effective route for performance improvement. In a MEMS-based humidity sensor, halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) functionalized with amino groups were incorporated into the PI layer to form a nanotube/polymer composite. Owing to the high specific surface area of HNTs and the additional adsorption sites provided by hydrophilic hydroxyl groups, the composite exhibited substantially enhanced water-vapor adsorption. As a result, the sensor’s sensitivity increased to 0.87 pF/% RH while maintaining low hysteresis (

) and good linearity (

) across the 10–90% RH range. The PI-based sensor also demonstrated excellent long-term stability under high-temperature and high-humidity conditions, consistent with the fact that PI maintains its physical and electrical properties across a wide temperature range from -269°C to 400°C [

112].

2.4.2. PVA

PVA, owing to the abundance of hydroxyl groups along its polymer backbone, exhibits strong water adsorption at room temperature and is therefore widely used to enhance humidity sensitivity [

113]. However, pristine PVA films tend to absorb water excessively, leading to swelling or even dissolution under high-humidity conditions. To address this limitation, various modification strategies have been developed to improve their stability in extreme humidity environments. One effective approach is crosslinking PVA or introducing copolymers to construct interpenetrating network structures. For example, Chen et al. [

114] developed a semi-interpenetrating polymer network comprising polydiallyl ammonium chloride (PDDA) and PVA, in which PVA was crosslinked in situ using glutaraldehyde. The resulting PDDA/crosslinked-PVA composite film, combined with graphene-oxide-derived electrodes, enabled a resistive humidity sensor that showed an impedance variation of nearly three orders of magnitude over the 10–90% RH range, along with a linear response and low hysteresis (4.4% RH). For instance, blending 10 wt% glycerol (Gly) with PVA produces a flexible film with significantly improved moisture absorption and reduced hysteresis. Gassab et al. [

115] reported that PVA/Gly composite film exhibited strong capacitive response and extremely low hysteresis within the 20–90% RH range, achieving a humidity sensitivity of up to 0.08 nF/%RH at 100 Hz and a hysteresis error of only 1.5% RH at 70% RH. To illustrate how nanocarbon–polymer composition governs humidity-responsive behavior,

Figure 6 summarizes the representative performance of CNO–PVA-based resistive humidity sensors. As shown in

Figure 6(a–d), adjusting the CNO:PVA ratio significantly influences resistance stability, hysteresis, and sensitivity across 5–95% RH, with the 1:1 composite yielding superior reproducibility and a more linear response at moderate humidity.

2.4.3. Cellulose

Cellulose and its derivatives, derived from renewable natural resources, are considered promising materials for green humidity sensing and flexible devices owing to their biodegradability, porous architectures, and excellent hygroscopic properties. Cellulose-based materials typically appear as porous membranes, paper substrates, or hydrogels, where abundant hydrophilic groups and interconnected micropores enable rapid adsorption and desorption of water vapor. For example, hydroxyethyl cellulose (HEC) has been used to fabricate hydrogel films coated onto the end facets of optical fibers, forming Fabry-Perot (F-P) interferometer cavities capable of dual-parameter temperature and humidity sensing, with sensitive and linear optical humidity detection across the 48–60% RH range [

108]. The incorporation of cellulose nanomaterials has become an emerging research hotspot. Cellulose nanofibers (CNFs), characterized by their small diameter and high specific surface area, can be processed into uniform and dense humidity-sensitive films. Introducing ionic liquids into CNF networks further enhances low-humidity dielectric response. Paper-based cellulose sensors have also attracted significant interest due to their low cost, flexibility, and suitability for wearable applications. Using laser direct writing to pattern conductive electrodes directly onto 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidinyl-1-oxyl (TEMPO)-oxidized cellulose paper enables the fabrication of fully cellulose-based humidity sensors with rapid response and disposable functionality [

117]. Furthermore, porous bacterial cellulose (BC) membranes produced by microbial fermentation, when combined with two-dimensional MXene or GO, provide both high conductivity and strong hygroscopicity [

118,

119]. These hybrid structures have been reported to yield humidity sensors with high sensitivity, fast response, and excellent mechanical flexibility.

2.4.4. PMMA

PMMA, owing to its intrinsic hydrophobicity and structural stability, exhibits excellent repeatability and low drift in optical and high-precision environmental monitoring. In pristine PMMA, water molecules are adsorbed only through weak physical interactions, resulting in minor changes in refractive index and volume, approximately 0.4% volumetric expansion per 1% RH increase [

120]. Although this limits its humidity response, it also provides exceptional linearity and extremely low hysteresis. Comparative studies of PMMA-, PVA-, and PEG-based F-P fiber-optic humidity sensors have shown that PMMA-coated sensors possess the lowest sensitivity but demonstrate the highest linearity in wavelength drift during wet-dry cycling (PMMA > PVA > PEG) [

106]. In addition, PMMA shows no performance degradation after repeated high-humidity cycling, confirming its superior repeatability and stability. To enhance the humidity sensitivity of PMMA, several modification strategies have been explored. One approach involves fabricating porous or micro/nanostructured PMMA films to increase water-vapor contact area and penetration depth. For example, porous PMMA coatings deposited on fiber Bragg gratings (FBG) can significantly extend the sensor’s humidity response range. Another strategy is to construct PMMA microsphere resonant cavities. Li et al. [

121] integrated PMMA microspheres, tens of micrometers in diameter, with fiber Bragg gratings, utilizing refractive-index variations and thermo-optic effects induced by humidity changes to achieve simultaneous humidity and temperature sensing. The F-P cavity formed between a PMMA microsphere and the fiber facet exhibited a humidity sensitivity of approximately 127 pm/% RH over the 35–85% RH range while remaining temperature-independent.

2.4.5. PA

The amide groups along the PA backbone readily form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, imparting moderate hygroscopicity. At the same time, PA exhibits strong mechanical strength and excellent abrasion resistance. In the field of flexible and wearable humidity sensors, thermoplastic polyamide elastomers (TPAEs) have gained considerable attention because they combine the elasticity of rubber with the strength of plastics. For example, the TPAE-based respiratory monitoring device developed by Chen et al. [

105] displays characteristic negative humidity sensitivity: the resistance of the sensing membrane decreases as ambient relative humidity increases, with an approximately linear response across 11-91 % RH and a coefficient of determination exceeding 0.99. PA also demonstrates strong stability under extreme environmental conditions. Nylon generally retains its mechanical integrity below 150°C and resists repeated bending and impact stresses [

122]. In vacuum or low-pressure environments, it gradually releases adsorbed moisture without structural degradation. However, exposure above the glass transition temperature or prolonged irradiation can lead to polyamide chain degradation. Therefore, when operating in harsh environments such as high temperatures or nuclear radiation, protective shielding or material modification strategies should be considered for polyamide-based sensors.

2.5. 2D Materials: Highly Responsive and Tunable Platforms for Extreme-Condition Humidity Sensing

Emerging 2D materials, characterized by their layered structures, exceptionally large specific surface areas, and tunable surface functional groups, exhibit unprecedented sensitivity and rapid dynamic response behaviors [

15]. These materials possess atomic-scale thickness and extend laterally in two dimensions, encompassing graphene and its derivatives, transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs), MXenes, layered metal phosphorous sulfides (e.g.,

), and black phosphorus [

123,

124,

125,

126]. Their extensive surface exposure, high density of active sites, and, in some cases, intrinsic hydrophilic functional groups endow 2D materials with significant potential for high-sensitivity and fast-response humidity sensing applications. As shown in

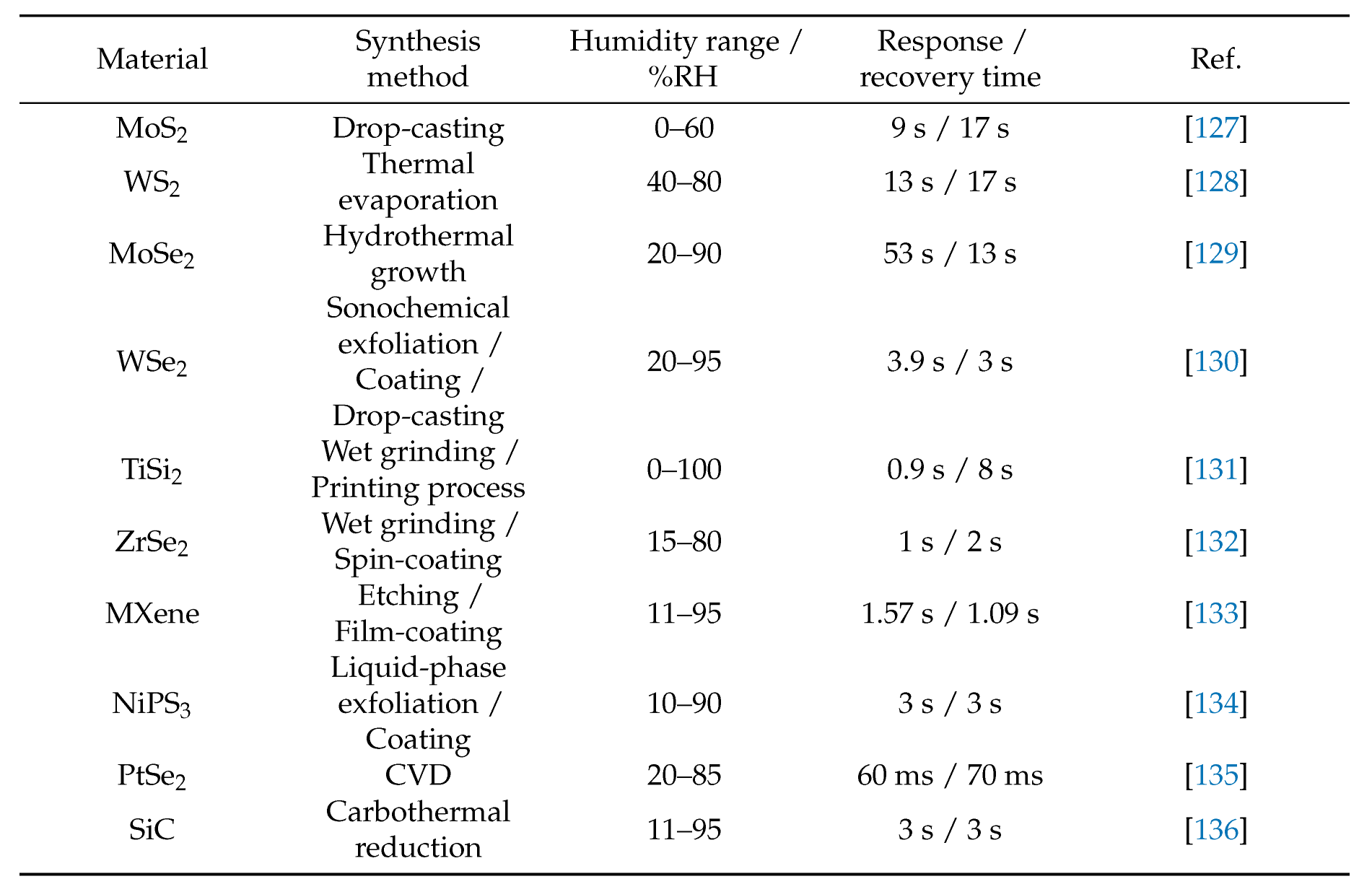

Table 5, typical single-component 2D materials already demonstrate outstanding response speeds and broad humidity operating ranges, underscoring their intrinsic suitability for high-performance humidity sensing.

Graphene-based materials were discussed in the preceding section on carbon-based systems; therefore, this section focuses on non-carbon 2D materials.

2.5.1. TMDs Materials

TMDs with their layered structures, tunable bandgaps, and high specific surface areas, offer distinct advantages for humidity sensing. These properties have led to their increasing use in both material design and device-level architectures intended for operation under extreme or harsh environmental conditions.

In MoS

2-based systems, recent research has focused on mitigating zero drift and hysteresis arising from temperature–humidity coupling through temperature compensation and surface/defect engineering, while simultaneously achieving low-humidity activation and wide-range linearity. For example, dense yet active-site-rich MoS

2 resistive films prepared via molten salt-assisted chemical vapor deposition allow the introduction of electrical temperature compensation, stabilizing sensitivity across varying temperatures [

137]. These devices exhibit sub-second to multi-second response times at room temperature while maintaining low hysteresis, making them suitable for outdoor applications or environments with abrupt temperature fluctuations. The representative sensing characteristics of these temperature-compensated MoS

2 devices are summarized in

Figure 7, including their linearity, hysteresis behavior, dynamic response, and long-term stability, all of which underscore the effectiveness of integrating compensation circuitry with defect-engineered MoS

2 films.

To meet the requirements of large-area fabrication, flexible integration, and low-temperature processing, printable and transferable MoS

2 inks have emerged as another major focus [

138]. Conductive films produced through atomized inkjet printing demonstrate conductivity changes spanning several orders of magnitude over the 10-95% RH range, with response/recovery times on the order of seconds. Such inks can be patterned directly onto flexible polymer substrates, enabling low-power wearable humidity sensors. In environments characterized by strong electromagnetic interference or high-voltage discharge, optical readout offers a natural advantage by avoiding the risks associated with wiring and electromagnetic coupling. When MoS

2 is coated onto microfiber, evanescent-field, or interferometric structures, the overall response/recovery time decreases to 0.09 s and 0.13 s, and the optical interrogation path becomes insensitive to electromagnetic noise, making these devices suitable for detecting rapid humidity disturbances near plasma, microwave, or high-voltage systems [

139].

To balance low-humidity activation with high-humidity saturation behavior, MoSe

2 and its MoS

2 heterostructures leverage a synergistic mechanism of interface polarization, defect modulation, and short mass-transfer pathways. 3D MoSe

2@MoS

2 composites deliver enhanced response amplitude and shorter response/recovery times across 11-95% RH by constructing continuous adsorption-desorption pathways along basal planes and edge sites [

140]. The MM3 heterostructure exhibits the largest sensitivity enhancement, the fastest response/recovery times (30 s/33 s), excellent cyclic reversibility, and clear concentration-dependent step responses from 12.5 to over 20 000 ppm H

2O far outperforming single phase MoSe

2 or MoS

2. These composites also maintain reversible output under cyclic and mechanical perturbations, making them promising for environments with rapid fluctuations in temperature and humidity or mechanical stress. Composites of MoSe

2 with porous templates or wide-bandgap oxides further exhibit low hysteresis and strong linearity even under near-saturated humidity. Their processability and tunable pore structures support translation into array-based and large-area manufacturing.

Work on WS

2 emphasizes flexibility and low power consumption. By coupling

with graphene quantum dots or 2D conductive frameworks, continuous electron/ion transport networks can be established at low temperatures while simultaneously suppressing moisture-induced hysteresis. GOQD/

flexible composite films achieve high responsiveness and rapid dynamics across wide humidity ranges, retaining performance after repeated bending and adapting well to wearable applications such as sweat monitoring or large-deformation conditions [

141]. Meanwhile, fully printed

/MXene composite sensors exhibit broad humidity sensitivity, low hysteresis, and good array uniformity, offering practical advantages for low-temperature fabrication and large-area adhesion [

142].

Beyond flexibility-oriented design strategies, recent WS

2-based devices have also explored structural actuation to enhance dynamic performance. In particular, Li et al. [

143] integrated a piezoelectric actuator beneath a WS

2 capacitive sensor, demonstrating that high-frequency PZT vibration can significantly accelerate moisture adsorption and desorption without compromising sensitivity or stability. The representative device architecture and sensing characteristics are summarized in

Figure 8, highlighting fast response/recovery, reduced hysteresis, and robust long-term operation under repeated humidity cycling.

Research on

has extended 2D humidity sensing to textile platforms to meet the challenges of strong deformation and long-term wear. Incorporating a 2H-

conductive coating into cotton fabrics yields stable and reversible resistive responses across 30–90% RH while maintaining breathability, washability, and cyclic durability which features essential for wearable real-time monitoring and high–water-vapor-flux environments within clothing layers [

144]. Additionally, CVD-grown

impedance sensors achieve minimal hysteresis (

) under low-humidity conditions and controllable hysteresis (

) under high humidity, providing valuable benchmarks for low-humidity detection and reproducibility evaluation [

145].

Recent research has expanded the material palette to include “quasi–two-dimensional” and emerging 2D semiconductors such as , , and , enabling the development of humidity sensors with high sensitivity, broad measurement ranges, and stable operation even under near-saturated humidity conditions.

, a metal silicide, provides abundant adsorption and active sites while maintaining high intrinsic conductivity due to its layered structure. It has been employed for the first time in resistive humidity sensors, fabricated on interdigitated electrodes using low-cost printing processes, yielding highly linear resistance variations across a wide humidity range. Such devices have shown strong applicability in human–machine interaction scenarios under high-humidity and rapidly fluctuating environments, including respiratory monitoring and non-contact skin-moisture detection [

131].

, a typical TMDC, features a tunable bandgap of approximately 1 eV and a layered van der Waals structure. 2D

nanosheets produced via wet milling and liquid-phase exfoliation can be spin-coated onto flexible interdigitated electrodes to form large-area, continuous conductive networks. Sensors based on this architecture exhibit resistive sensitivity as high as 68 k

% RH, excellent linearity, and rapid response/recovery times on the order of 1–2 s within the 15-80% RH range [

132]. The device maintains stable capacitive behavior under various bending angles and demonstrates reliable non-contact humidity detection when a moist or dry fingertip is placed several millimeters above the surface. The transient response to humidity bursts, whether from exhaled moisture, skin evaporation, or sprayed water, remains fast and reproducible, confirming the practical suitability of ZrSe

2 flakes for wearable, high-humidity, and dynamically varying environments.

Furthermore, constructing a 0D/2D Au/GeS heterostructure using gold nanoparticles significantly enhances interfacial polarization and accelerates water adsorption/desorption kinetics in the IV–VI semiconductor GeS. The resulting flexible humidity sensor exhibits extremely high response and sub-second response/recovery times even at 90% RH. Its successful integration into an IoT platform for real-time wireless respiratory monitoring indicates that GeS and its heterostructures are well suited for humidity sensing under near-saturated humidity conditions and even in condensation-prone environments [

146].

As a 2D magnetic semiconductor,

possesses an interlayer P–S framework that provides abundant polar sites, enabling selective adsorption of water molecules and substantial charge-transfer interactions. A first-principles study published in 2025 quantitatively demonstrated the preferential adsorption of

and its pronounced modulation of the electronic conductivity of

[

147]. The results showed that water molecules induce significantly stronger charge redistribution than common interfering gases, suggesting that

can maintain stable humidity sensitivity even under temperature fluctuations and mixed-gas environments. In addition, surface-defect engineering and strain modulation further reduce response times, establishing a tunable parameter window suitable for rapid transitions between low and high humidity and for detecting fast RH step changes.

2.5.2.

For readout strategies that require strong electromagnetic immunity, optical interrogation is preferred, especially in environments involving strong electromagnetic fields or high-voltage discharge. Coating 2D semiconductors onto microfibers or evanescent-field waveguides can inherently avoid failures caused by wiring or electromagnetic coupling. Although such demonstrations have been predominantly reported for

, the fabrication process and device architecture are directly transferrable to

[

148].

In the context of multi-parameter sensing, recent materials science studies have revealed tunable excitonic and magnetic ordering in

, providing a foundation for integrating optical or magneto-optical readout schemes into humidity sensors designed for irradiated or high-magnetic-field environments [

149]. As an experimental reference, early flexible

-based humidity sensors have already demonstrated second-scale response times, mechanical bendability, and strong selectivity [

150]. These device-level insights, including electrode design, impedance-spectroscopy mechanisms, and in-situ Raman tracking, offer valuable guidance for the structural design and packaging requirements of

sensors intended for extreme operating conditions.

2.5.3. MXene Materials

MXene materials, owing to their metallic conductivity, abundant surface −OH and =O functional groups, and tunable 2D layered structures, have recently emerged as promising candidates for next-generation humidity sensors. Their humidity-sensing mechanism involves a coupled process of ionic conduction and interlayer expansion. Under low to moderate humidity, surface-adsorbed water molecules enhance ionic transport and interfacial polarization, markedly increasing sensitivity. At high humidity levels, water penetrates the interlayer galleries, inducing layer expansion and suppressing interlayer electron transport, which in turn causes a counterintuitive increase in resistance. Although this unique mechanism confers exceptionally high sensitivity, it also leads to challenges in stability under extreme conditions [

151,

152].

To address oxidation and long-term degradation, Yang et al. [

153] stabilized

MXene ink using sodium ascorbate and fabricated a flexible capacitive humidity sensor on paper substrates via screen printing. The device exhibited a capacitance change of 131.4% across 11-97% RH, with response/recovery times of 9.4 s and 12.9 s, respectively. This anti-oxidation strategy effectively mitigates performance decay under high humidity and enables a low-cost, large-area, and robust platform suitable for harsh environments such as high humidity and elevated temperature. Surface functionalization further enhances MXene performance, particularly in high-humidity regions. Huang et al. [

154] modified

with the cationic polyelectrolyte PDDA to create a fully printed flexible thin-film sensor capable of non-contact humidity detection. The device demonstrated high sensitivity and excellent cycling stability even under severe electromagnetic interference and in confined spaces. Wang et al. [

155] incorporated carrageenan into MXene films to form a disposable, low-cost, and fast-responding paper-based sensor suitable for distributed deployment in extreme environments. Similarly, sodium-alginate (SA)/MXene composite sensors remain stable under saturated humidity and long-term humidity cycling [

156].

In strong electromagnetic or high-voltage discharge environments, optical readout offers a promising strategy to avoid electrode failure and wiring-related issues. Li et al. [

157] developed an all-optical humidity-sensing platform by coating

onto optical fibers, achieving rapid and stable responses, including in applications such as respiratory monitoring, while maintaining immunity to external electromagnetic interference. Porous aerogel architectures have proven highly effective for reducing hysteresis and enhancing dynamic performance. Xiao et al. [

158] reported a

aerogel-based wearable sensor with near-linear humidity response (

) and extremely low hysteresis (

), making it suitable for environments characterized by frequent humidity steps and rapid fluctuations. To provide a representative example of MXene–polyelectrolyte systems capable of operating in extreme humidity,

Figure 9 presents the structural design and humidity-sensing performance of a cross-linked SA/MXene device, including its stability at saturated humidity and repeated cycling durability [

156].

2.6. Composite Materials: Multimodal Mechanisms for Humidity Detection

Modern humidity-sensing technology places strong emphasis on the use of nanomaterials and multicomponent composites. Many of the materials discussed above exhibit markedly enhanced performance when engineered at the nanoscale. Size effects impart nanomaterials with properties not present in their bulk counterparts, such as quantum-confinement–induced modulation of carrier transport and surface-energy dominated adsorption behavior. Nanofibers, nanowires, and quantum dots, for example, offer exceptionally high specific surface areas and short diffusion pathways, enabling faster and more efficient humidity adsorption and desorption. Incorporating nanostructures into various humidity-sensitive material systems allows for synergistic optimization, effectively combining the inherent advantages of each component to achieve improved overall sensing performance.

Structural parameters such as porosity, particle size, and film thickness have a profound influence on the humidity-sensing characteristics of materials. Increasing porosity can substantially enhance the effective surface area available for moisture adsorption, accelerate the adsorption–desorption process, improve sensitivity, and shorten response times. However, excessive porosity may compromise the mechanical integrity of the film, necessitating a balance between sensitivity and structural stability [

58]. Achieving uniform and well-ordered surface morphology further contributes to improved sensor consistency and repeatability. Film thickness also plays a critical role in sensing dynamics: overly thick films extend the diffusion path of water molecules, resulting in slower responses, whereas ultrathin films—despite their rapid response—may suffer from weak signal output or reduced stability due to limited water uptake. Therefore, selecting appropriate nanostructures and geometries according to specific application requirements is essential. Moreover, combining two or more materials enables the integration of complementary advantages and compensation for individual limitations, representing an important direction in the development of next-generation humidity-sensing materials.

1D nanowires and nanotubes, owing to their small diameters and high specific surface areas, can adsorb larger quantities of water molecules and provide direct electron and ion transport pathways, thereby enhancing both response speed and signal strength. A representative example is the

@ZnO core–shell nanorod system: the ZnO shell offers a hydrophilic surface and ionic conduction channels, while the

core improves electronic transport and mechanical robustness, enabling the sensor to achieve high sensitivity with low hysteresis. Similarly, self-supported ZnO nanowire humidity-sensitive membranes exhibit significantly faster dynamic responses than particulate membranes, largely because the nanowire network minimizes the blocking effects of grain boundaries and pores. 2D nanosheet assemblies can form interlayer diffusion channels that allow water molecules to migrate rapidly along the stacking interfaces. Dual-sided adsorption increases the total water uptake capacity; however, excessively dense stacking can hinder penetration, necessitating interlayer spacing control or the introduction of supporting structures to maintain porosity. 0D nanoparticles and hollow spheres further highlight the importance of mesoporous and macroporous architectures. Nanoparticle-assembled mesopores regulate capillary condensation, hollow spheres provide internal cavities for water storage, and thin-shell structures facilitate rapid water ingress and egress [

159,

160].These structural advantages across 0D, 1D, and 2D nanoarchitectures are summarized in

Figure 10, which schematically illustrates representative humidity-sensitive morphologies.

Recent studies further validate the critical role of nanostructures in enhancing humidity sensitivity. Jin et al. [

161] fabricated a honeycomb-like CNF/CNT aerogel membrane using an ice-templating method, achieving a relative resistivity change of 71.5% over the 0–75% RH range, with response and recovery times of 18 s and 47 s, respectively. Chen et al. [

162] developed a “PI nanoforest” structure that significantly increased surface area and adsorption sites, resulting in a device sensitivity 15 times higher than that of planar PI across 10–90% RH. Musa et al. [

163] synthesized a V-doped

three-dimensional array via solution impregnation, improving sensitivity from 196 (pure

) to 314. This enhancement was attributed to the increased adsorption/desorption capability associated with defect sites introduced by V doping and the densely packed nanostructure.

In the field of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), Wu et al. [

164] prepared a highly porous polyelectrolyte membrane by in situ crosslinking UIO-66 with a sulfonated polymer. The resulting film exhibited rapid respiratory humidity detection, with a response time of 3.1 s and a recovery time of only 1.5 s. Polymer/MOF composites have similarly attracted attention: MOFs possess ultrahigh surface areas and tunable functional groups that provide exceptional humidity sensitivity, yet their inherently low conductivity limits direct sensing applications. Embedding MOFs within conductive polymer matrices yields dielectric or impedance-type composite films capable of detecting trace water vapor. Sapsanis et al. [

165] demonstrated that capacitive electrodes coated with the copper-based MOF HKUST-1 produced humidity responses several times higher than those of traditional polymer dielectrics. Zhang et al. [

166] reported that an amino-functionalized titanium-based MOF (

-MIL-125(Ti)) resistive thin-film sensor exhibited resistance changes of up to three orders of magnitude within 30–90% RH. These results indicate that polymers supply mechanical support and electrical pathways for MOF particles, while MOFs contribute exceptional hygroscopic capacity and selectivity together enabling synergistic performance enhancement. Composite functional coatings can also improve selectivity under extreme conditions. For instance, coating ZnO with a hydrophobic MOF (ZIF-8) effectively suppresses humidity interference in acetone detection at 260°C, enabling humidity-insensitive gas sensing. Similarly, applying a ZIF-8 layer onto

gas-sensitive films acts as a “molecular sieve” to block water molecules, allowing accurate

detection even under high humidity [

160]. These examples clearly demonstrate that composite surface functionalization can significantly enhance sensor selectivity and reduce cross-sensitivity in harsh environments.

It is important to recognize that the behavior of materials incorporating nanostructures must be re-evaluated when operating in extreme environments. On the one hand, nanomaterials with high specific surface areas are more susceptible to accumulating radiation-induced damage or adsorbing particulate contaminants, necessitating appropriate shielding strategies. On the other hand, certain nanostructures possess limited mechanical robustness and may collapse or aggregate under thermal cycling or vibrational shock. For example, applying a hydrophobic and breathable protective film to the surface of a humidity sensor can prevent liquid-water condensation from damaging the sensing layer and reduce interference from adhered volatile contaminants. For space and near-space applications, humidity sensors typically require encapsulation layers capable of withstanding high-energy particle radiation and abrupt temperature fluctuations. These protective layers, together with the sensing material, form a composite system that must balance environmental protection with minimal obstruction to water-vapor transport.

In the Typhoon Near-Space Sounder developed by the BIT team, researchers evaluated several shell materials and ultimately selected rigid foam as a structural carrier to balance insulation performance and overall device weight. This design effectively adds a composite protective structure to the sensing unit, enabling reliable operation at temperatures as low as -60°C and under extremely low-pressure conditions. Meanwhile, the device’s integrated micro-heating and temperature-control system can also be regarded as a functional composite component, ensuring that the sensing membrane remains within an appropriate temperature–humidity window and thereby enhancing reliability in harsh environments. Consequently, humidity-sensitive composite materials intended for extreme-condition applications must prioritize stable interfacial bonding and undergo rigorous environmental simulation testing [

167].

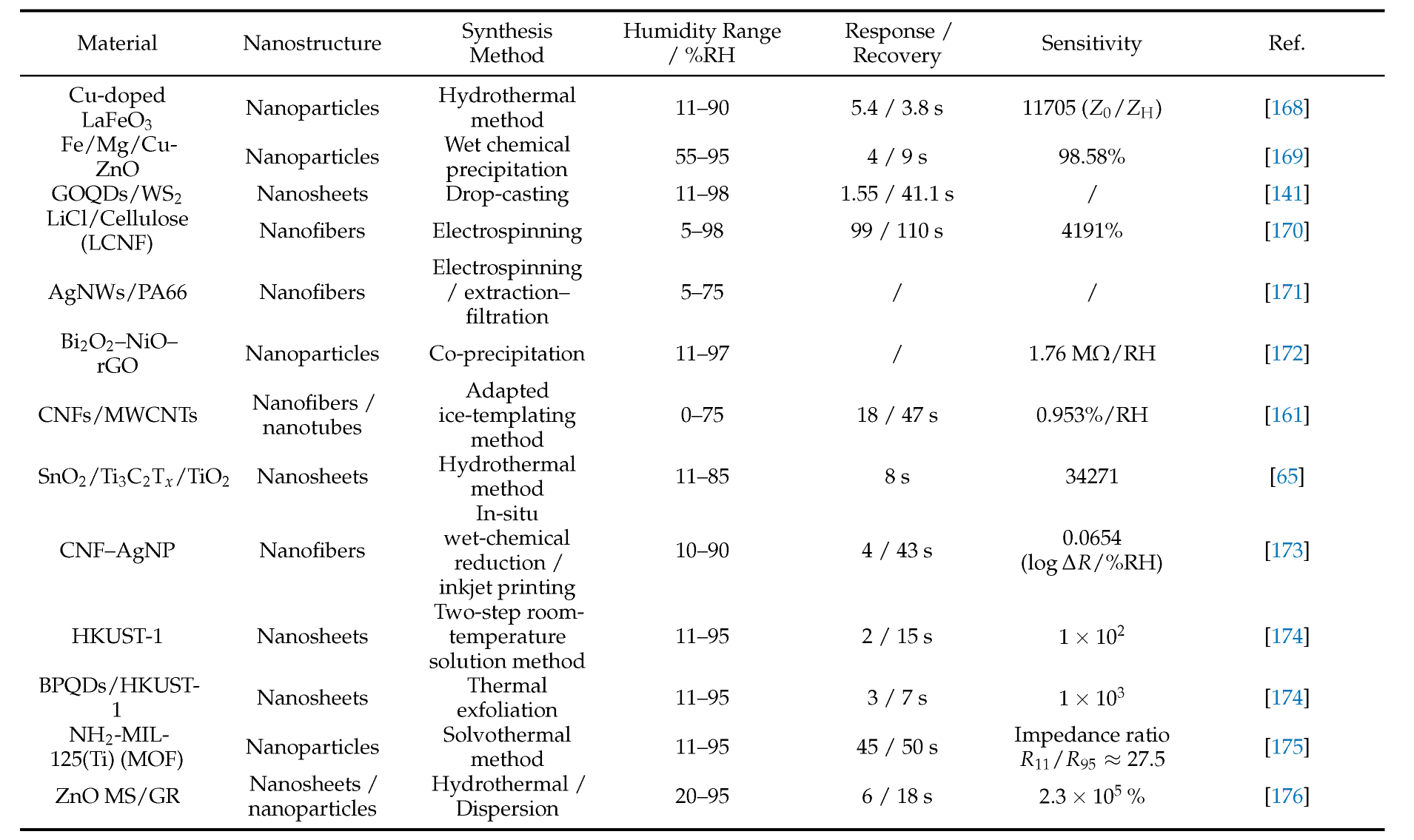

Table 6.

Performance summary of single-component polymer materials for humidity sensing.

Table 6.

Performance summary of single-component polymer materials for humidity sensing.

3. Discussion

In summary, different humidity-sensitive material systems exhibit distinct structure–performance relationships and environmental adaptability when used for humidity detection under extreme conditions. Porous carbon materials, with their hierarchical micro/meso/macroporous architectures, provide exceptional rapid response in low-humidity environments, making them one of the most effective material systems for dry and arid extreme settings. Metal oxides, benefiting from their robust lattice frameworks and tunable surface oxygen vacancies, offer outstanding chemical and structural stability under harsh conditions such as high temperature and corrosive atmospheres. Polymers and hydrogels, through the formation of dynamic water networks, deliver ultrahigh sensitivity and fast proton conduction in high-humidity or saturated environments. 2D materials and MXenes, leveraging their adjustable interlayer spacing, abundant defect states, and high charge-carrier mobility, achieve a unique combination of high sensitivity and mechanical flexibility, rendering them particularly suitable for flexible, wearable, and deformable humidity-sensing applications in extreme environments.

Despite the unique advantages offered by each material system, all of them exhibit inherent limitations when exposed to extreme humidity environments involving multiphysics coupling. For instance, metal oxides are prone to surface water–film–dominated effects under ultrahigh humidity, which can lead to pronounced hysteresis and increased nonlinearity. Polymers and hydrogels may undergo swelling fatigue, structural relaxation, or even irreversible network rearrangement during repeated humidity cycling. 2D materials and MXenes can suffer from interlayer degradation, oxidation, or terminal-group instability when subjected to high humidity or elevated temperatures. Porous carbon materials, meanwhile, often display notable hysteresis and saturation effects in high-humidity regions due to water retention within the pores and insufficient intrinsic hydrophilicity.

In contrast, composite material systems and multimodal humidity-sensing strategies can partially overcome the limitations of single-material sensors through material synergy and signal complementarity. For example, inorganic–polymer composites can achieve both high-temperature stability and strong responsiveness under high humidity. Hybrid structures combining two-dimensional materials with carbon materials, or MXenes with polymers, enhance environmental tolerance while preserving high sensitivity. Multimodal sensing approaches further improve reliability by integrating multiple signal channels, hereby enabling redundant recognition and error suppression in complex or extreme environments. Together, these strategies offer system-level pathways toward robust and accurate humidity detection under harsh operating conditions.

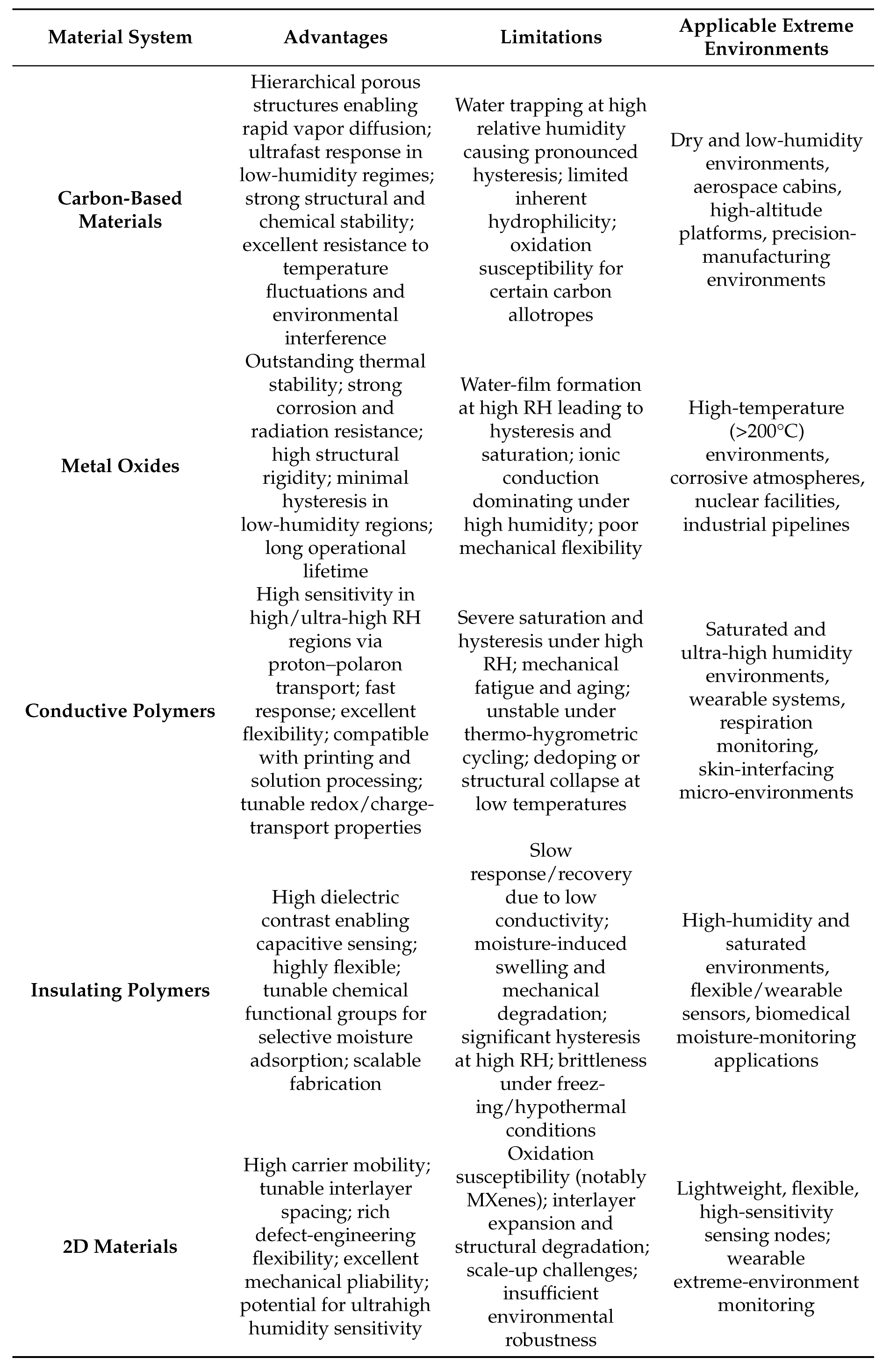

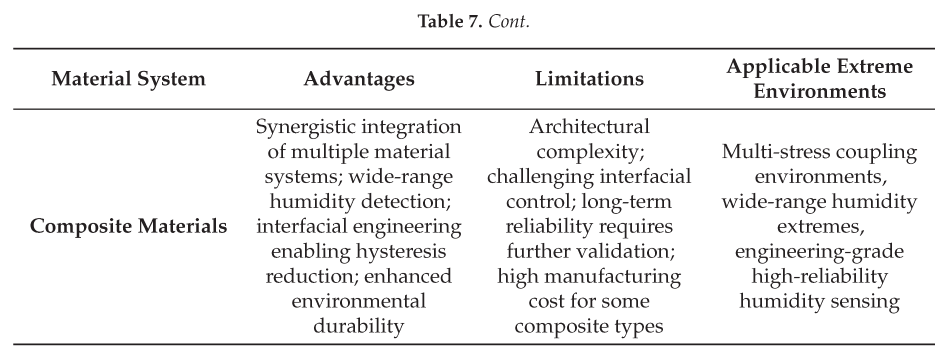

Table 7 summarizes the advantages, limitations, and suitable operating environments of various material systems. It is evident that the performance of humidity-sensitive materials under extreme conditions is no longer dictated solely by their intrinsic chemical properties, but is governed by a combination of factors, including interfacial water structuring, adsorption–desorption energy barriers, carrier migration mechanisms, and the evolution of material microstructures. Consequently, achieving high reliability, low hysteresis, a wide dynamic response range, and long-term stability in extreme-environment humidity detection requires coordinated optimization across multiple dimensions, including materials chemistry, interface engineering, multiscale structural design, and system-level integration.

The forthcoming Future Prospects section will expand on these findings through a cross-system examination of materials, addressing fundamental issues relevant to extreme-humidity applications, including interfacial adsorption behavior, saturation and hysteresis mechanisms, stability evolution, and methodologies for multimodal detection and composite-material development. It will also outline potential pathways for overcoming current performance bottlenecks and advancing humidity-sensing technologies for operation under extreme conditions.

4. Future Prospect