Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Liver Fibrosis: Pathophysiology and Clinical Relevance

3.1. Stages

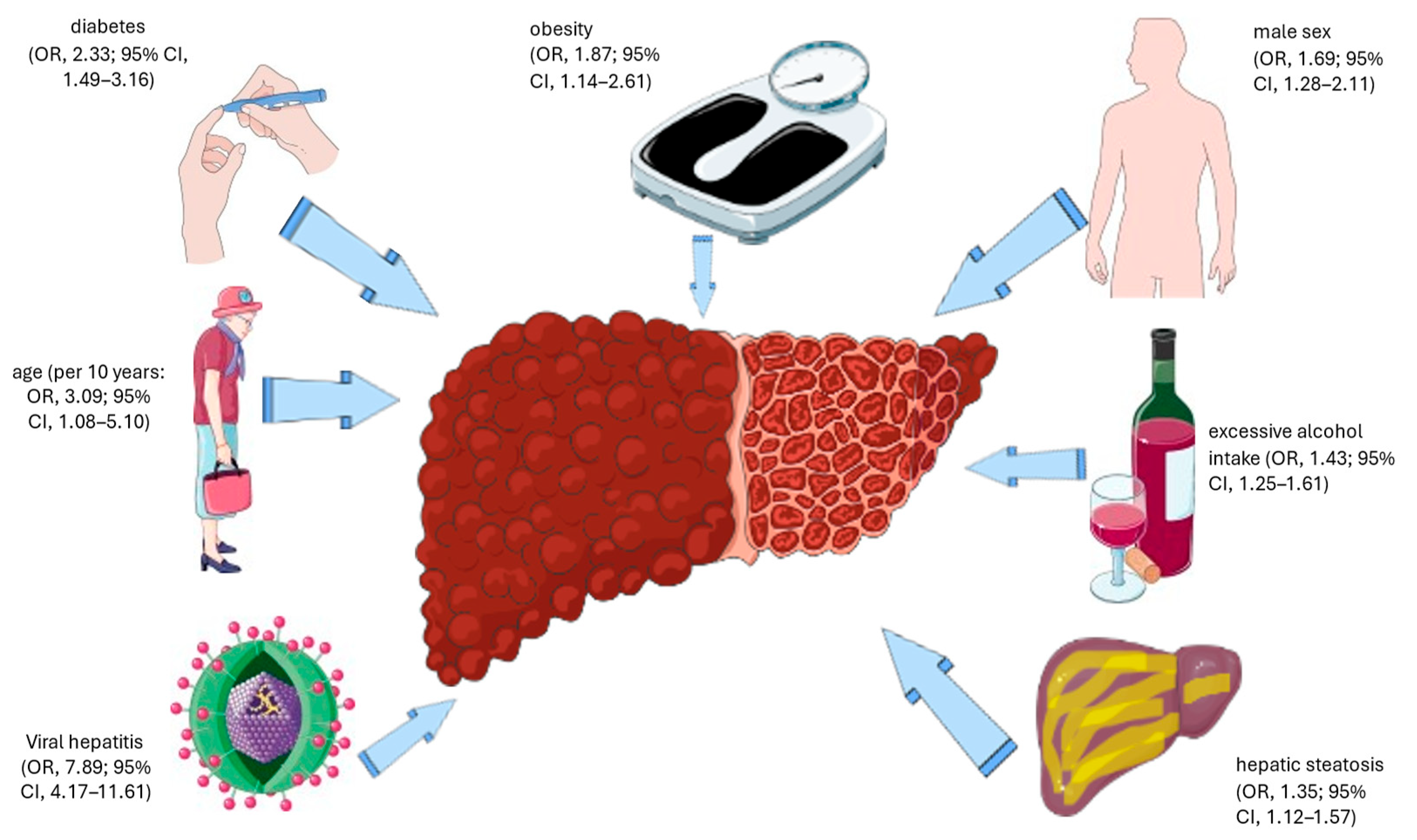

3.2. Prevalence and Risk Factors

3.3. Pathomechanisms of Liver Fibrosis

3.4. Liver Fibrosis and Extrahepatic Outcomes

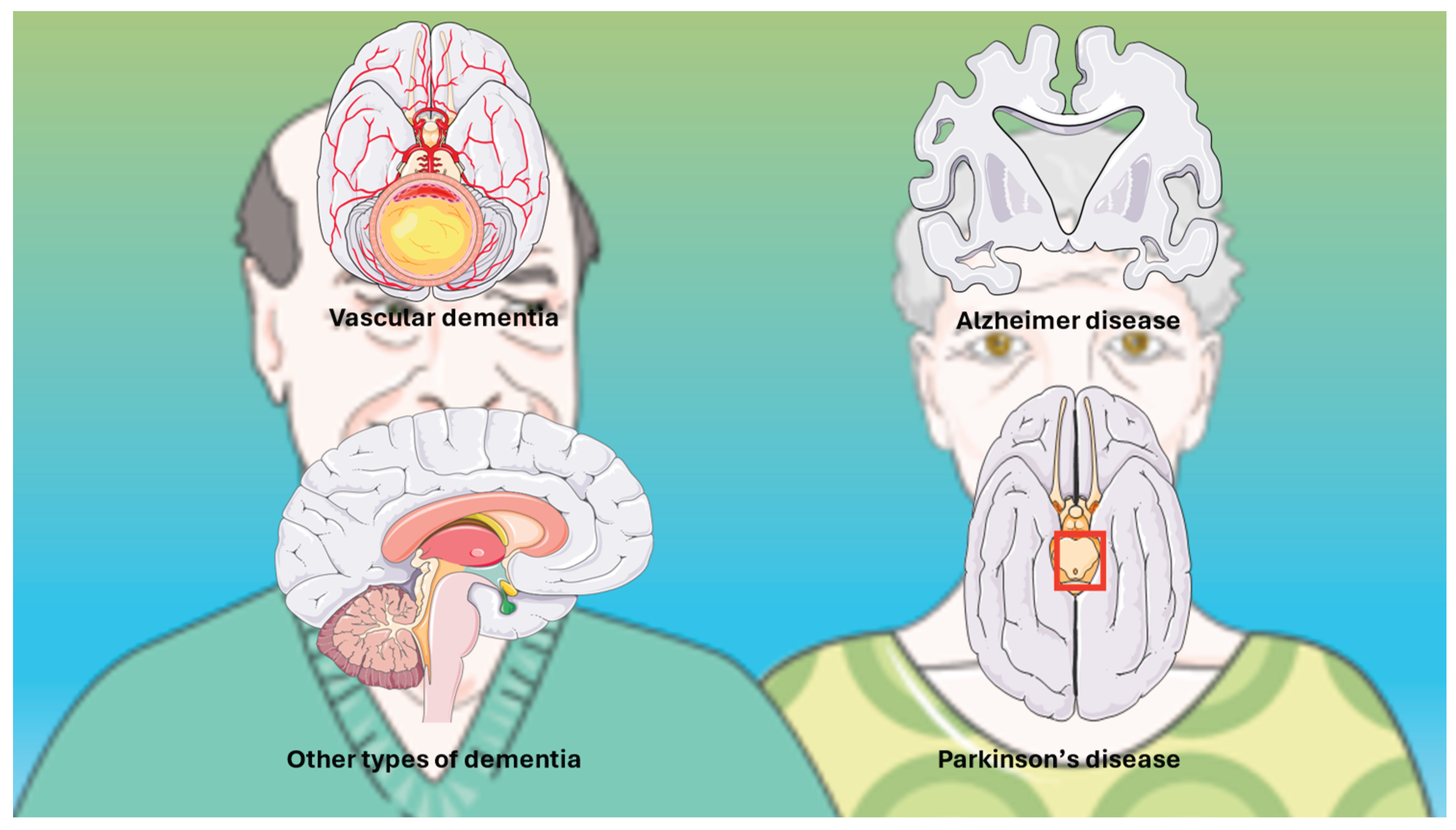

4. Dementia: Overview

4.1. Definitions and Spectrum

4.2. Pathophysiology and Risk Factors

5. Evidence Linking Liver Fibrosis and Dementia

5.1. Epidemiological Evidence

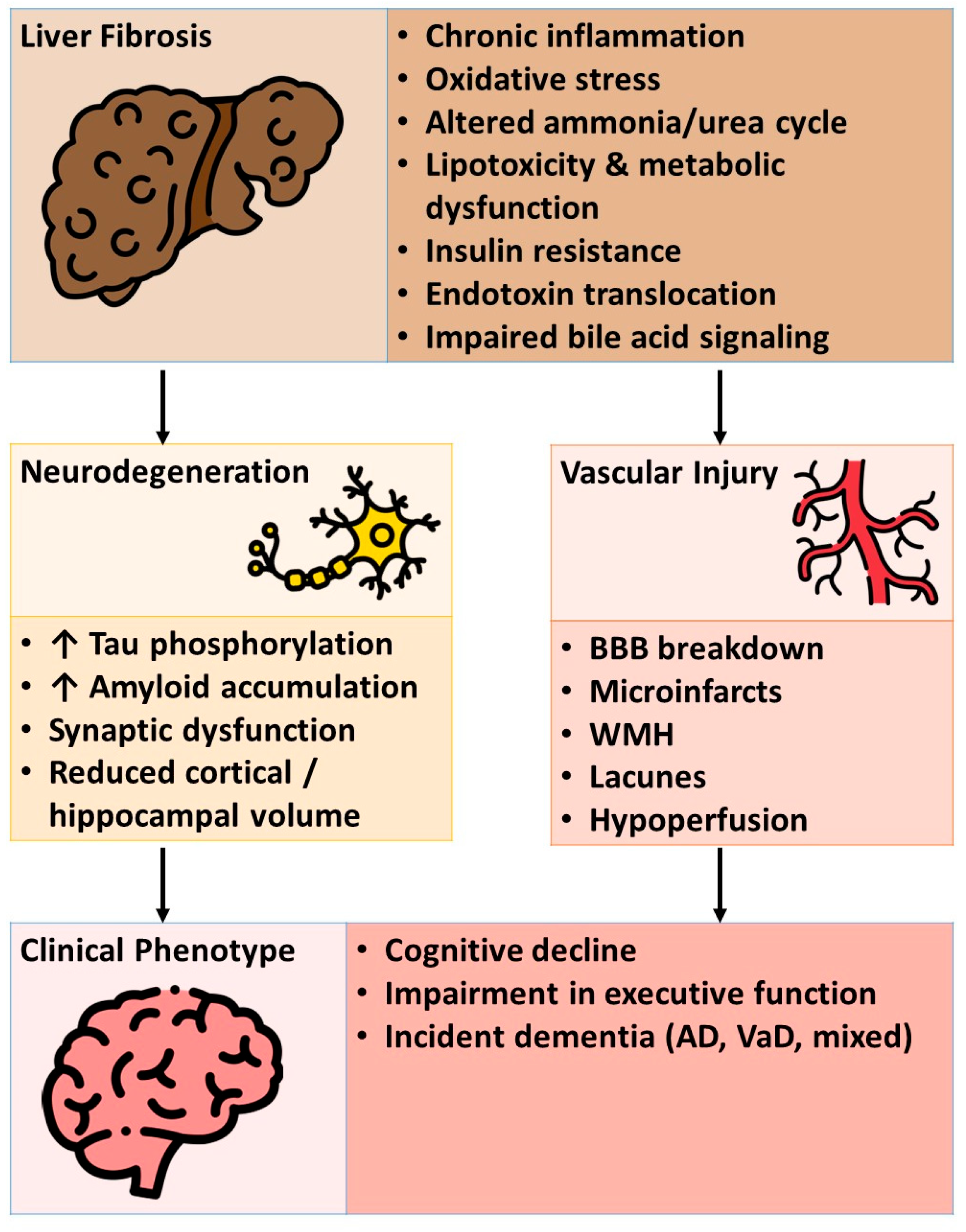

5.2. Mechanistic Insights

5.2.1. Liver-Brain Axis: Neuroinflammation, Insulin Resistance, and Vascular Dysfunction

5.2.2. Metabolic Dysregulation and Oxidative Stress

5.2.3. Gut-Liver-Brain Axis: Intestinal Microbiota, Endotoxins, and Ammonia

5.3. Sex and Age Differences

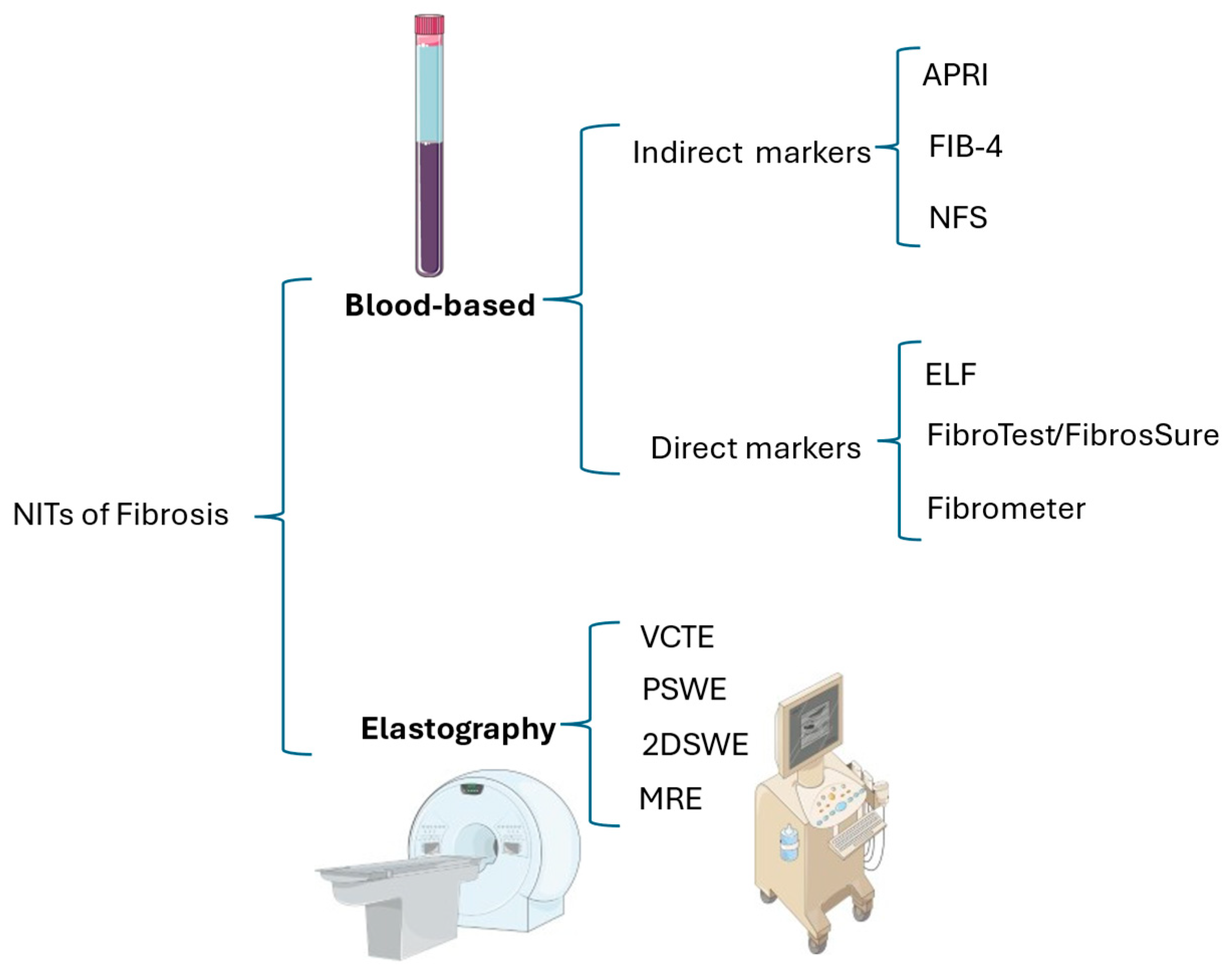

6. Diagnostic Considerations

6.1. Fibrosis Assessment

6.1.1. Blood-Based Non-Invasive Tests

6.1.2. Elastometry

6.1.3. Sequential Non-Invasive Assessment of Liver Fibrosis

7. Cognitive Assessment and Biomarkers

7.1. Mini-Mental State Examination and Montreal Cognitive Assessment

7.2. Additional Diagnostic Techniques

7.3. Risk Prediction Models

8. Therapeutic and Preventive Implications

8.1. Liver-Directed Interventions: Lifestyle, Pharmacological, and Bariatric Approaches

8.2. Neuroprotective Potential of Liver-Focused Therapies

8.3. Multidisciplinary Care: Integrating Hepatology and Cognitive Medicine

9. Gaps in Knowledge and Future Directions

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| β | Regression coefficient |

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| AF | Atrial fibrillation |

| ALD | Alcohol-related liver disease |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E |

| APRI | aminotransferase–platelet ratio index |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| AST/ALT | Aspartate aminotransferase / alanine aminotransferase ratio |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| CLD | Chronic liver disease |

| DBil | Direct bilirubin |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| FHS | Framingham Heart Study |

| ELF | enhanced liver fibrosis score |

| FA | Fractional anisotropy |

| FIB-4 | Fibrosis-4 index |

| GGT | Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase |

| GLP-1 RAs | glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists |

| HOMA | Homeostatic model assessment |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| HSC | Hepatic stellate cell |

| MASH | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease |

| MD | Mean diffusivity |

| MetALD | Metabolic dysfunction and ALD |

| MMSE | Mini-Mental State Examination |

| MoCA | Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MRE | Magnetic Resonance Elastography |

| MRI | Magnetic resonance imaging |

| MRI-PDFF | Magnetic resonance imaging–proton density fat fraction |

| NFS | NAFLD fibrosis score |

| PDD | Parkinson’s Disease Dementia |

| PET | Positron emission tomography |

| PFDR | False discovery rate–adjusted p-value |

| PNPLA3 | Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3 |

| RS | Rotterdam Study |

| SHIP | Study of Health in Pomerania |

| TBil | Total bilirubin |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| TMAO | trimethylamine-N-oxide |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| VaD | Vascular dementia |

| VCTE | Vibration-controlled transient elastography |

| WMH | White matter hyperintensity |

Appendix A

| Database | Syntax |

| PubMed | (("liver"[Mesh] AND ("Elasticity Imaging Techniques"[Mesh] OR "biopsy"[Mesh] OR "fibrosis"[Mesh])) OR “Liver Cirrhosis”[Mesh] OR (("liver"[tiab] OR "hepatic"[tiab]) AND ("biops*"[tiab] OR "fibros*"[tiab] OR "cirrhos*"[tiab] OR "stiffness*"[tiab] OR "puncture"[tiab] OR "elastogra*"[tiab] OR "elasticit*"[tiab] OR "acoustography"[tiab] OR "vibroacoustography"[tiab] OR "vibro-acoustography"[tiab] OR "sonoelastograph*"[tiab] OR "fibroscan"[tiab] OR "acoustic radiation force impulse imaging"[tiab] OR "arfi imaging*"[tiab]))) AND ("Dementia"[Mesh] OR "Dementia*"[tiab] OR "Alzheimer*"[tiab] OR "Binswanger encephalopathy"[tiab] OR "CADASIL"[tiab] OR "Lewy body disease"[tiab] OR "Neurofibrillary tangles with calcification"[tiab] OR "Primary progressive aphasia"[tiab] OR "Progressive nonfluent aphasia"[tiab] OR "Hereditary diffuse leukoencephalopathy with spheroids"[tiab] OR "Huntington chorea"[tiab] OR "Kluver-Bucy syndrome"[tiab] OR "Mental deterioration"[tiab] OR "Nasu-Hakola disease"[tiab] OR "Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis"[tiab] OR "Prion disease"[tiab] OR "Bovine spongiform encephalopathy"[tiab] OR "Chronic wasting disease"[tiab] OR "Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease"[tiab] OR "Feline spongiform encephalopathy"[tiab] OR "Fatal familial insomnia"[tiab] OR "Gerstmann-Straussler-Scheinker syndrome"[tiab] OR "Kuru"[tiab] OR "Scrapie"[tiab] OR "Transmissible mink encephalopathy"[tiab] OR "Variably protease-sensitive prionopathy"[tiab] OR "Pseudodementia"[tiab] OR "Rett syndrome"[tiab] OR "Senility"[tiab] OR "Tauopathy"[tiab] OR "Creutzfeldt-Jakob syndrome"[tiab] OR "Diffuse neurofibrillary tangles with calcification"[tiab] OR "Frontotemporal lobar degeneration"[tiab] OR "Huntington disease"[tiab] OR "Amentia*"[tiab]) AND ("1900/01/01"[Date - Publication] : "2025/11/30"[Date - Publication]) AND (humans[Filter]) AND(english[Filter]) AND (alladult[Filter]) |

References

- Zamani, M.; Alizadeh-Tabari, S.; Ajmera, V.; Singh, S.; Murad, M.H.; Loomba, R. Global Prevalence of Advanced Liver Fibrosis and Cirrhosis in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025, 23, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C.D.; Tilg, H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut 2024, 73, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsomidis, I.; Voumvouraki, A.; Kouroumalis, E. Immune Checkpoints and the Immunology of Liver Fibrosis. Livers 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalinia, M.; Zare, F.; Lonardo, A. Liver Fibrosis and Risk of Incident Dementia in the General Population: Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Health Sci Rep 2025, 8, e71530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, E.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Vollset, S.E.; Fukutaki, K.; Chalek, J.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdoli, A.; Abualhasan, A.; Abu-Gharbieh, E.; Akram, T.T.; et al. Estimation of the global prevalence of dementia in 2019 and forecasted prevalence in 2050: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, e105–e125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Q.; Wang, X. Alzheimer’s disease: insights into pathology, molecular mechanisms, and therapy. Protein & Cell 2024, 16, 83–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, A.C.D.; Kjærgaard, K.; Schapira, A.H.V.; Mookerjee, R.P.; Thomsen, K.L. The liver-brain axis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025, 10, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, V.; Fontdevila, L.; Rico-Rios, S.; Povedano, M.; Andrés-Benito, P.; Torres, P.; Serrano, J.C.E.; Pamplona, R.; Portero-Otin, M. Microbial Influences on Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: The Gut–Brain Axis and Therapeutic Potential of Microbiota Modulation. Sclerosis 2025, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, G.; Schonmann, Y.; Yeshua, H.; Zelber-Sagi, S. The association between liver fibrosis score and incident dementia: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 5385–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikh, N.S.; Kamel, H.; Zhang, C.; Kumar, S.; Rosenblatt, R.; Spincemaille, P.; Gupta, A.; Cohen, D.E.; de Leon, M.J.; Gottesman, R.F.; et al. Association between liver fibrosis and incident dementia in the UK Biobank study. Eur J Neurol 2022, 29, 2622–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bataller, R.; Brenner, D.A. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2005, 115, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, M.; Islam, M.A.; Khairnar, R.; Kumar, S. A guide to pathophysiology, signaling pathways, and preclinical models of liver fibrosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2025, 598, 112448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, D.E.; Brunt, E.M.; Van Natta, M.; Behling, C.; Contos, M.J.; Cummings, O.W.; Ferrell, L.D.; Liu, Y.C.; Torbenson, M.S.; Unalp-Arida, A.; et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology 2005, 41, 1313–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brol, M.J.; Drebber, U.; Luetkens, J.A.; Odenthal, M.; Trebicka, J. “The pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis: basic facts and clinical challenges”—assessment of liver fibrosis: a narrative review. Digestive Medicine Research 2022, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Yuan, Y.; Shen, H.; Go, J.; Kong, X.; Che, Z.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, E.; Xiao, J. Liver diseases: epidemiology, causes, trends and predictions. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2025, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballestri, S.; Nascimbeni, F.; Romagnoli, D.; Lonardo, A. The independent predictors of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and its individual histological features.: Insulin resistance, serum uric acid, metabolic syndrome, alanine aminotransferase and serum total cholesterol are a clue to pathogenesis and candidate targets for treatment. Hepatol Res 2016, 46, 1074–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, R.; Lin, J.; Chen, S.; Lu, Z.; Gong, Y.; Tan, S.; Liu, X.; He, W. Communication initiated by hepatocytes: The driver of HSC activation and liver fibrosis. Hepatol Commun 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonardo, A.; Weiskirchen, R. Liver and obesity: a narrative review. Exploration of Medicine 2025, 6, 1001334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, K.; Paluch, M.; Cudzik, M.; Syska, K.; Gawlikowska, W.; Janczura, J. From steatosis to cirrhosis: the role of obesity in the progression of liver disease. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2025, 24, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Zhang, X.; Kuang, M.; Yu, J. The gut-liver axis in immune remodeling of hepatic cirrhosis. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 946628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maslennikov, R.; Poluektova, E.; Zolnikova, O.; Sedova, A.; Kurbatova, A.; Shulpekova, Y.; Dzhakhaya, N.; Kardasheva, S.; Nadinskaia, M.; Bueverova, E.; et al. Gut Microbiota and Bacterial Translocation in the Pathogenesis of Liver Fibrosis. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, D.; Huang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Jin, W.; Zhang, X.; Yu, F. Interactions between hepatic stellate cells and immune cells: Implications for liver fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2026, 1872, 168062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Zawadzki, A.; Leeming, D.J.; Sanyal, A.J.; Anstee, Q.M.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Friedman, S.L.; Schuppan, D.; Karsdal, M.A. Hot and cold fibrosis: The role of serum biomarkers to assess immune mechanisms and ECM-cell interactions in human fibrosis. J Hepatol 2025, 83, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, R.; Lonardo, A. PNPLA3 as a driver of steatotic liver disease: navigating from pathobiology to the clinics via epidemiology. J Transl Genetics Genomics 2024, 8, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanquier, Z.; Misra, J.; Baxter, R.; Maiers, J.L. Stress and Liver Fibrogenesis: Understanding the Role and Regulation of Stress Response Pathways in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Am J Pathol 2023, 193, 1363–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugari, S.; Baldelli, E.; Lonardo, A. Metabolic primary liver cancer in adults: risk factors and pathogenic mechanisms. Metabolism and Target Organ Damage 2023, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A.; Ballestri, S.; Baffy, G.; Weiskirchen, R. Liver fibrosis as a barometer of systemic health by gauging the risk of extrahepatic disease. Metabolism and Target Organ Damage 2024, 4, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.G.; Polyzos, S.A.; Park, K.H.; Mantzoros, C.S. Fibrosis-4 Index Predicts Long-Term All-Cause, Cardiovascular and Liver-Related Mortality in the Adult Korean Population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 21, 3322–3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampuero, J.; Aller, R.; Gallego-Durán, R.; Crespo, J.; Calleja, J.L.; García-Monzón, C.; Gómez-Camarero, J.; Caballería, J.; Lo Iacono, O.; Ibañez, L.; et al. Significant fibrosis predicts new-onset diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension in patients with NASH. J Hepatol 2020, 73, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampuero, J.; Aller, R.; Gallego-Durán, R.; Crespo, J.; Calleja, J.L.; García-Monzón, C.; Gómez-Camarero, J.; Caballería, J.; Lo Iacono, O.; Ibañez, L.; et al. Erratum to: "Significant fibrosis predicts new-onset diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension in patients with NASH (J Hepatol 2020; 73: 17-25). J Hepatol 2020, 73, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Lin, L.; Wu, Y.; Hu, L.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, D.; Fu, T.; Zhao, H.; Yin, X.; et al. Prognostic value of FIB-4 and NFS for cardiovascular events in patients with and without NAFLD. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A. Extra-hepatic cancers in metabolic fatty liver syndromes. Exploration of Digestive Diseases 2023, 2, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L. Hepatic Fibrosis and Cancer: The Silent Threats of Metabolic Syndrome. Diabetes Metab J 2024, 48, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Lonardo, A.; Stefan, N.; Targher, G. Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease and extrahepatic gastrointestinal cancers. Metabolism 2024, 160, 156014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lonardo, A. Association of NAFLD/NASH, and MAFLD/MASLD with chronic kidney disease: an updated narrative review. Metabolism and Target Organ Damage 2024, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipriani, G.; Danti, S.; Picchi, L.; Nuti, A.; Fiorino, M.D. Daily functioning and dementia. Dement Neuropsychol 2020, 14, 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgueño-García, I.; López-Martínez, M.J.; Uceda-Heras, A.; García-Carracedo, L.; Zea-Sevilla, M.A.; Rodrigo-Lara, H.; Rego-García, I.; Saiz-Aúz, L.; Ruiz-Valderrey, P.; López-González, F.J.; et al. Neuropathological Heterogeneity of Dementia Due to Combined Pathology in Aged Patients: Clinicopathological Findings in the Vallecas Alzheimer’s Reina Sofía Cohort. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2024, 13, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kong, G.; Yang, J.; Pang, L.; Li, X. Pathological mechanisms and treatment progression of Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Med Res 2025, 30, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Shue, F.; Bu, G.; Kanekiyo, T. Pathophysiology and probable etiology of cerebral small vessel disease in vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2023, 18, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donnelly, P.S.; Sweeney, A.; Passmore, A.P.; McCorry, N.K.; Kane, J.P.M. Research on the perspectives of people affected by dementia with Lewy bodies: a scoping review. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy 2025, 17, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattola, S.; Ielo, A.; Varone, G.; Cacciola, A.; Quartarone, A.; Bonanno, L. Frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review of artificial intelligence approaches in differential diagnosis. Front Aging Neurosci 2025, 17, 1547727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custodio, N.; Montesinos, R.; Lira, D.; Herrera-Pérez, E.; Bardales, Y.; Valeriano-Lorenzo, L. Mixed dementia: A review of the evidence. Dement Neuropsychol 2017, 11, 364–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeto, J.Y.Y.; Walton, C.C.; Rizos, A.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Halliday, G.M.; Naismith, S.L.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Lewis, S.J.G. Dementia in long-term Parkinson's disease patients: a multicentre retrospective study. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2020, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.L.; Weintraub, D.; Lemmen, R.; Perera, G.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Svenningsson, P.; Aarsland, D. Risk of Dementia in Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mov Disord 2024, 39, 1697–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzinal, D.; Elgey, C.; Bailey, D.X.; Yang, J.; Lehn, A.; Tinson, H.; Liddle, J.; Brooks, D.; Naismith, S.L.; Shrubsole, K. Diagnosis, evaluation & management of cognitive disorders in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review 10.1016/j.inpsyc.2025.100081. Int Psychogeriatr 2025, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, D.; Socodato, R. Beyond Amyloid and Tau: The Critical Role of Microglia in Alzheimer’s Disease Therapeutics. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, R.; Bordbar, S.; Azad, G.; Davoody, S.; Mahmoudi, M.; Esmaeilpour, K. Beyond Neuroinflammation: Microglia at the Crossroads of Amyloid, Tau, and Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurological Sciences 2025, 46, 5591–5605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Yu, Q.; Cheng, Q.; Lu, Z.; Zong, S. The roles of microglia and astrocytes in neuroinflammation of Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurosci 2025, 19–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafi, A.; Akmal, M.; Sethi, A.; Chauhdary, Z. A mechanistic insight of neuro-inflammation signaling pathways and implication in neurodegenerative disorders. Inflammopharmacology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alaqel, S.I.; Imran, M.; Khan, A.; Nayeem, N. Aging, vascular dysfunction, and the blood–brain barrier: unveiling the pathophysiology of stroke in older adults. Biogerontology 2025, 26, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preis, L.; Villringer, K.; Brosseron, F.; Düzel, E.; Jessen, F.; Petzold, G.C.; Ramirez, A.; Spottke, A.; Fiebach, J.B.; Peters, O. Assessing blood-brain barrier dysfunction and its association with Alzheimer’s pathology, cognitive impairment and neuroinflammation. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy 2024, 16, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar A, Sidhu J, Lui F, al. e. Alzheimer Disease. 2025 [cited 1 December 2025]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL). (updated 2024 Feb 12). [cited 1 December 2025]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499922/.

- Huang, X.-T.; Huang, L.-Y.; Tan, C.-C.; Wei, J.-M.; Zhang, X.-H.; Tan, L.; Xu, W. The role of APOE ε4 in modulating the relationship between non-genetic risk factors and dementia: a system review and meta-analysis. Journal of Neurology 2025, 272, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Guan, Z.; Guan, Q.; Guan, H.; Che, H. Association between apolipoprotein E ε4 status and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis. BMC Neuroscience 2025, 26, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.R.; Pike, J.R.; Gottesman, R.F.; Knopman, D.S.; Lutsey, P.L.; Palta, P.; Windham, B.G.; Selvin, E.; Szklo, M.; Bandeen-Roche, K.J.; et al. Contribution of Modifiable Midlife and Late-Life Vascular Risk Factors to Incident Dementia. JAMA Neurology 2025, 82, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekonnen, T.; Skirbekk, V.; Håberg, A.K.; Engdahl, B.; Zotcheva, E.; Jugessur, A.; Bowen, C.; Selbaek, G.; Kohler, H.-P.; Harris, J.R.; et al. Mediators of educational differences in dementia risk later in life: evidence from the HUNT study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.-L.; Luo, Y.-X.; Yao, X.-Q. Bridging systemic metabolic dysfunction and Alzheimer’s disease: the liver interface. Molecular Neurodegeneration 2025, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yang, R.; Miao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Paillard-Borg, S.; Fang, Z.; Xu, W. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease Is Associated With Accelerated Brain Ageing: A Population-Based Study. Liver Int 2025, 45, e70109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, P.Y.; Ou, Y.N.; Wang, H.F.; Wang, Z.B.; Fu, Y.; He, X.Y.; Ma, Y.H.; Feng, J.F.; Cheng, W.; Tan, L.; et al. Associations of liver dysfunction with incident dementia, cognition, and brain structure: A prospective cohort study of 431 699 adults. J Neurochem 2024, 168, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, G.; O'Donnell, A.; Frenzel, S.; Xiao, T.; Yaqub, A.; Yilmaz, P.; de Knegt, R.J.; Maestre, G.E.; Melo van Lent, D.; Long, M.; et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, liver fibrosis, and structural brain imaging: The Cross-Cohort Collaboration. Eur J Neurol 2024, 31, e16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, G.; O'Donnell, A.; Davis-Plourde, K.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Ghosh, S.; DeCarli, C.S.; Thibault, E.G.; Sperling, R.A.; Johnson, K.A.; Beiser, A.S.; et al. Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Liver Fibrosis, and Regional Amyloid-β and Tau Pathology in Middle-Aged Adults: The Framingham Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2022, 86, 1371–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Yang, S.; Wei, Y.; Tian, M.; Liu, Q.; Li, X.; Ding, J.; Li, X.; Mao, M.; Han, X.; et al. Characterization of brain morphology associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease in the UK Biobank. Diabetes Obes Metab 2025, 27, 3419–3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Pike, J.R.; Hoogeveen, R.C.; Walker, K.A.; Raffield, L.M.; Selvin, E.; Avery, C.L.; Engel, S.M.; Mielke, M.M.; Garcia, T.; et al. Liver integrity and the risk of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Alzheimers Dement 2024, 20, 1913–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.H.; Gordon, S.C.; Wu, T.; Trudeau, S.; Rupp, L.B.; Gonzalez, H.C.; Daida, Y.G.; Schmidt, M.A.; Lu, M. Antiviral Treatment and Response are Associated With Lower Risk of Dementia Among Hepatitis C Virus-Infected Patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2024, 32, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Nasr, P.; Ekstedt, M.; Widman, L.; Stål, P.; Hultcrantz, R.; Kechagias, S.; Hagström, H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease does not increase dementia risk although histology data might improve risk prediction. JHEP Rep 2021, 3, 100218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solfrizzi, V.; Scafato, E.; Custodero, C.; Loparco, F.; Ciavarella, A.; Panza, F.; Seripa, D.; Imbimbo, B.P.; Lozupone, M.; Napoli, N.; et al. Liver fibrosis score, physical frailty, and the risk of dementia in older adults: The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2020, 6, e12065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, T.; van Kleef, L.A.; Ikram, M.K.; de Knegt, R.J.; Ikram, M.A. Association of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Fibrosis With Incident Dementia and Cognition: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology 2022, 99, e565–e573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taru, V.; Szabo, G.; Mehal, W.; Reiberger, T. Inflammasomes in chronic liver disease: Hepatic injury, fibrosis progression and systemic inflammation. J Hepatol 2024, 81, 895–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, R.; Wu, J.; Rosenblatt, M.; Dai, W.; Rodriguez, R.X.; Sui, J.; Qi, S.; Liang, Q.; Xu, B.; Meng, Q.; et al. Elevated C-reactive protein mediates the liver-brain axis: a preliminary study. EBioMedicine 2023, 93, 104679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Tang, D.; Chen, R. Neuroimmune modulation in liver pathophysiology. J Neuroinflammation 2024, 21, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn, P.; Tacke, F. Metabolic reprogramming in liver fibrosis. Cell Metab 2024, 36, 1439–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Duggan, M.R.; Dark, H.E.; Daya, G.N.; An, Y.; Davatzikos, C.; Erus, G.; Lewis, A.; Moghekar, A.R.; Walker, K.A. Association of liver disease with brain volume loss, cognitive decline, and plasma neurodegenerative disease biomarkers. Neurobiol Aging 2022, 120, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lei, K.; Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Wei, K.; Guo, J.; Su, Z. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: From a Very Low-Density Lipoprotein Perspective. Biomolecules 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoebinger, C.; Rajcic, D.; Hendrikx, T. Oxidized Lipids: Common Immunogenic Drivers of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Atherosclerosis. Front Cardiovasc Med 2021, 8, 824481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, M.; Robino, G. Oxidative stress-related molecules and liver fibrosis. J Hepatol 2001, 35, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Lee, G.; Heo, S.Y.; Roh, Y.S. Oxidative Stress Is a Key Modulator in the Development of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delli Bovi, A.P.; Marciano, F.; Mandato, C.; Siano, M.A.; Savoia, M.; Vajro, P. Oxidative Stress in Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. An Updated Mini Review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 595371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houldsworth, A. Role of oxidative stress in neurodegenerative disorders: a review of reactive oxygen species and prevention by antioxidants. Brain Commun 2024, 6, fcad356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trofin, D.M.; Sardaru, D.P.; Trofin, D.; Onu, I.; Tutu, A.; Onu, A.; Onită, C.; Galaction, A.I.; Matei, D.V. Oxidative Stress in Brain Function. Antioxidants (Basel) 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Pu, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, B.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J. The pathogenesis of liver fibrosis in Wilson's disease: hepatocyte injury and regulation mediated by copper metabolism dysregulation. Biometals 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albillos, A.; de Gottardi, A.; Rescigno, M. The gut-liver axis in liver disease: Pathophysiological basis for therapy. J Hepatol 2020, 72, 558–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, W.A.; Gray, A.M.; Erickson, M.A.; Salameh, T.S.; Damodarasamy, M.; Sheibani, N.; Meabon, J.S.; Wing, E.E.; Morofuji, Y.; Cook, D.G.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide-induced blood-brain barrier disruption: roles of cyclooxygenase, oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and elements of the neurovascular unit. J Neuroinflammation 2015, 12, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, A.; Sgamato, C.; Compare, D.; Coccoli, P.; Nardone, O.M.; Nardone, G. Gut Microbes and Hepatic Encephalopathy: From the Old Concepts to New Perspectives. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9, 748253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Buffa, J.A.; Gupta, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Mehrabian, M.; et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.P.; Bernardi, A.; Frozza, R.L. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalile, B.; Van Oudenhove, L.; Vervliet, B.; Verbeke, K. The role of short-chain fatty acids in microbiota-gut-brain communication. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019, 16, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamalinia, M.; Lonardo, A.; Weiskirchen, R. Sex and Gender Differences in Liver Fibrosis: Pathomechanisms and Clinical Outcomes. Fibrosis 2024, 2, 10006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabelli, C.; Codemo, A. Gender differences in cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease. The Italian Journal of Gender-Specific Medicine 2015, 1, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.N.; Ding, W.X. The impact of aging on liver health and the development of liver diseases. Hepatol Commun 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagetti, B.; Puig-Domingo, M. Age-Related Hormones Changes and Its Impact on Health Status and Lifespan. Aging Dis 2023, 14, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, B.B.; Flicker, L. Testosterone, cognitive decline and dementia in ageing men. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 2022, 23, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A.; Jamalinia, M.; Weiskirchen, R. Sex differences in MASLD. SciErixiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonardo, A.; Suzuki, A. Sex differences in alcohol-related liver disease, viral hepatitis, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Exploration of Digestive Diseases 2025, 4, 1005101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.H.; Kisseleva, T.; Brenner, D.A. Aging and liver disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2015, 31, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Dan, X.; Babbar, M.; Wei, Y.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2019, 15, 565–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, R.; Lonardo, A. The Ovary-Liver Axis: Molecular Science and Epidemiology. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, R.; Lonardo, A. Sex Hormones and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saelzler, U.G.; Sundermann, E.E.; Foret, J.T.; Gatz, M.; Karlsson, I.K.; Pederson, N.L.; Panizzon, M.S. Age of menopause and dementia risk in 10,832 women from the Swedish Twin Registry. Alzheimers Dement 2025, 21, e70541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, D.; Desai, V.; Janardhan, S. Con: Liver Biopsy Remains the Gold Standard to Evaluate Fibrosis in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken) 2019, 13, 114–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josh, B.; Daniel, J.C.; Christopher, D.B. Evolving models of care in patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, recognising its population burden and the impact of metabolic dysfunction on incident rates of hepatic and extrahepatic outcomes. Artificial Intelligence Surgery 2025, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castera, L.; Rinella, M.E.; Tsochatzis, E.A. Noninvasive Assessment of Liver Fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2025, 393, 1715–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anania, F.A.; Hager, R.; Higgins, K.; Makar, G.A.; Siegel, J.; Tran, T.T. Non-invasive tests: Establishing efficacy for metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis beyond the biopsy-Current perspectives from the Division of Hepatology and Nutrition, US Food and Drug Administration. Hepatology 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPherson, S.; Hardy, T.; Dufour, J.F.; Petta, S.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Allison, M.; Oliveira, C.P.; Francque, S.; Van Gaal, L.; Schattenberg, J.M.; et al. Age as a Confounding Factor for the Accurate Non-Invasive Diagnosis of Advanced NAFLD Fibrosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2017, 112, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boursier, J.; Canivet, C.M.; Costentin, C.; Lannes, A.; Delamarre, A.; Sturm, N.; Le Bail, B.; Michalak, S.; Oberti, F.; Hilleret, M.N.; et al. Impact of Type 2 Diabetes on the Accuracy of Noninvasive Tests of Liver Fibrosis With Resulting Clinical Implications. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023, 21, 1243–1251.e1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, W.; Li, Y.; Geng, J.; Wang, P.; Zhang, L. Aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio can reduce the need for transient elastography in Chinese patients with chronic hepatitis B. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e18038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, A.A.; Myers, R.P. Diagnostic accuracy of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: a systematic review. Hepatology 2007, 46, 912–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.L.; Jiang, L.S.; Wu, C.S.; Pan, L.Y.; Lou, Z.Q.; Peng, C.T.; Dong, Y.; Ruan, B. The role of fibrosis index FIB-4 in predicting liver fibrosis stage and clinical prognosis: A diagnostic or screening tool? J Formos Med Assoc 2022, 121, 454–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Schuch, A.; Longo, L.; Valentini, B.B.; Galvão, G.S.; Luchese, E.; Pinzon, C.; Bartels, R.; Álvares-da-Silva, M.R. New FIB-4 and NFS cutoffs to guide sequential non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis by magnetic resonance elastography in NAFLD. Ann Hepatol 2023, 28, 100774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, M.; Venkatesh, S.K. Ultrasound or MR elastography of liver: which one shall I use? Abdom Radiol (NY) 2018, 43, 1546–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilenberg, M.; Munda, P.; Stift, J.; Langer, F.B.; Prager, G.; Trauner, M.; Staufer, K. Accuracy of non-invasive liver stiffness measurement and steatosis quantification in patients with severe and morbid obesity. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2021, 10, 610–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpton, S.R.; Tamaki, N.; Bettencourt, R.; Madamba, E.; Jung, J.; Liu, A.; Behling, C.; Valasek, M.A.; Loomba, R. Diagnostic accuracy of two-dimensional shear wave elastography and transient elastography in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2021, 14, 17562848211050436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, J.V.; Castera, L.; Mark, H.E.; Allen, A.M.; Adams, L.A.; Anstee, Q.M.; Arrese, M.; Alqahtani, S.A.; Bugianesi, E.; Colombo, M.; et al. Real-world evidence on non-invasive tests and associated cut-offs used to assess fibrosis in routine clinical practice. JHEP Rep 2023, 5, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erratum Regarding Previously Published Articles. JHEP Rep 2024, 6, 101097. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mózes, F.E.; Lee, J.A.; Selvaraj, E.A.; Jayaswal, A.N.A.; Trauner, M.; Boursier, J.; Fournier, C.; Staufer, K.; Stauber, R.E.; Bugianesi, E.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-invasive tests for advanced fibrosis in patients with NAFLD: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Gut 2022, 71, 1006–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, H.; Salehi, A.M.; Ghamarchehreh, M.E.; Khanlarzadeh, E.; Sohrabi, M.R. Diagnostic Accuracy of Vibration Controlled Transient Elastography as Non-invasive Assessment of Liver Fibrosis in Patients with Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Middle East J Dig Dis 2023, 15, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasnacht, J.S.; Wueest, A.S.; Berres, M.; Thomann, A.E.; Krumm, S.; Gutbrod, K.; Steiner, L.A.; Goettel, N.; Monsch, A.U. Conversion between the Montreal Cognitive Assessment and the Mini-Mental Status Examination. J Am Geriatr Soc 2023, 71, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Estrella, A.; Hakim, O.; Milazzo, P.; Patel, S.; Pintagro, C.; Li, D.; Zhao, R.; Vance, D.E.; Li, W. Mini-Mental State Examination and Montreal Cognitive Assessment as Tools for Following Cognitive Changes in Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Participants. J Alzheimers Dis 2022, 90, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitakis, Z.; Shah, R.C.; Bennett, D.A. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. Jama 2019, 322, 1589–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Rivet, L.; Mah, E.; Bawa, K.K.; Gallagher, D.; Herrmann, N.; Lanctôt, K.L. Novel fluid biomarkers for mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res Rev 2023, 91, 102046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; Yang, T.; He, X.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.; Han, L. Blood biomarkers for post-stroke cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2024, 33, 107632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.D.; Deng, C.F.; Chen, P.F.; Li, A.; Wu, H.Z.; Ouyang, F.; Hu, X.G.; Liu, J.X.; Wang, S.M.; Tang, D. Non-invasive metabolic biomarkers in initial cognitive impairment in patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab 2024, 26, 5519–5536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.; Liao, L.; Liu, Q.; Ma, R.; He, X.; Du, X.; Sha, D. Blood biomarkers for vascular cognitive impairment based on neuronal function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol 2025, 16, 1496711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivipelto, M.; Ngandu, T.; Laatikainen, T.; Winblad, B.; Soininen, H.; Tuomilehto, J. Risk score for the prediction of dementia risk in 20 years among middle aged people: a longitudinal, population-based study. Lancet Neurol 2006, 5, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farkas, K.; Lazar, T.; Becske, M.; Zsuffa, J.A.; Rosenfeld, V.; Berente, D.B.; Bolla, G.; Negyesi, J.; Horvath, A.A. The CAIDE dementia risk score indicates elevated cognitive risk in late adulthood: a structural and functional neuroimaging study. GeroScience 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anstey, K.J.; Cherbuin, N.; Herath, P.M. Development of a new method for assessing global risk of Alzheimer's disease for use in population health approaches to prevention. Prev Sci 2013, 14, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anatürk, M.; Patel, R.; Ebmeier, K.P.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Newby, D.; Topiwala, A.; de Lange, A.G.; Cole, J.H.; Jansen, M.G.; Singh-Manoux, A.; et al. Development and validation of a dementia risk score in the UK Biobank and Whitehall II cohorts. BMJ Ment Health 2023, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anstey, K.J.; Kootar, S.; Huque, M.H.; Eramudugolla, R.; Peters, R. Development of the CogDrisk tool to assess risk factors for dementia. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2022, 14, e12336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erratum. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 2022, 14, e12387. [CrossRef]

- Rosenau, C.; Köhler, S.; van Boxtel, M.; Tange, H.; Deckers, K. Validation of the Updated "LIfestyle for BRAin health" (LIBRA) Index in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing and Maastricht Aging Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2024, 101, 1237–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schon, H.T.; Weiskirchen, R. Exercise-Induced Release of Pharmacologically Active Substances and Their Relevance for Therapy of Hepatic Injury. Front Pharmacol 2016, 7, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arita, V.A.; Cabezas, M.C.; Hernández Vargas, J.A.; Trujillo-Cáceres, S.J.; Mendez Pernicone, N.; Bridge, L.A.; Raeisi-Dehkordi, H.; Dietvorst, C.A.W.; Dekker, R.; Uriza-Pinzón, J.P.; et al. Effects of Mediterranean diet, exercise, and their combination on body composition and liver outcomes in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med 2025, 23, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Yang, B.; Liu, Q.; Gao, M.; Luo, M. The long-term neuroprotective effect of MIND and Mediterranean diet on patients with Alzheimer's disease. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 32725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, R.; Lonardo, A. How 'miracle' weight-loss semaglutide promises to change medicine but can we afford the expense? Br J Pharmacol 2025, 182, 1651–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorucci, S.; Urbani, G.; Distrutti, E.; Biagioli, M. Obeticholic Acid and Other Farnesoid-X-Receptor (FXR) Agonists in the Treatment of Liver Disorders. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2025, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanyal, A.J.; Ratziu, V.; Loomba, R.; Anstee, Q.M.; Kowdley, K.V.; Rinella, M.E.; Sheikh, M.Y.; Trotter, J.F.; Knapple, W.; Lawitz, E.J.; et al. Results from a new efficacy and safety analysis of the REGENERATE trial of obeticholic acid for treatment of pre-cirrhotic fibrosis due to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol 2023, 79, 1110–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, S.A.; Abdelmalek, M.F.; Neff, G.; Gunn, N.; Guy, C.D.; Alkhouri, N.; Bashir, M.R.; Freilich, B.; Kohli, A.; Khazanchi, A.; et al. Aldafermin in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (ALPINE 2/3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 7, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro Delgado, L.; Fabretina de Souza, V.; Fontel Pompeu, B.; de Moraes Ogawa, T.; Pereira Oliveira, H.; Sacksida Valladão, V.D.C.; Lima Castelo Branco Marques, F.I. Long-Term Outcomes in Sleeve Gastrectomy versus Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Obes Surg 2025, 35, 3246–3257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Custers, E.; Vreeken, D.; Kleemann, R.; Kessels, R.P.C.; Duering, M.; Brouwer, J.; Aufenacker, T.J.; Witteman, B.P.L.; Snabel, J.; Gart, E.; et al. Long-Term Brain Structure and Cognition Following Bariatric Surgery. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7, e2355380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasmi, A.; Bjørklund, G.; Mujawdiya, P.K.; Semenova, Y.; Peana, M.; Dosa, A.; Piscopo, S.; Gasmi Benahmed, A.; Costea, D.O. Micronutrients deficiences in patients after bariatric surgery. Eur J Nutr 2022, 61, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Mansoori, A.; Shakoor, H.; Ali, H.I.; Feehan, J.; Al Dhaheri, A.S.; Cheikh Ismail, L.; Bosevski, M.; Apostolopoulos, V.; Stojanovska, L. The Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Vitamin B Status and Mental Health. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Li, Y.; Yang, L.L.; Luo, Y.X.; Yao, X.Q. Bridging systemic metabolic dysfunction and Alzheimer's disease: the liver interface. Mol Neurodegener 2025, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moaket, O.S.; Obaid, S.E.; Obaid, F.E.; Shakeeb, Y.A.; Elsharief, S.M.; Tania, A.; Darwish, R.; Butler, A.E.; Moin, A.S.M. GLP-1 and the Degenerating Brain: Exploring Mechanistic Insights and Therapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiskirchen, R. Hepatoprotective and Anti-fibrotic Agents: It's Time to Take the Next Step. Front Pharmacol 2015, 6, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galicia-Moreno, M.; Monroy-Ramirez, H.C.; Caloca-Camarena, F.; Arceo-Orozco, S.; Muriel, P.; Sandoval-Rodriguez, A.; García-Bañuelos, J.; García-González, A.; Navarro-Partida, J.; Armendariz-Borunda, J. A new opportunity for N-acetylcysteine. An outline of its classic antioxidant effects and its pharmacological potential as an epigenetic modulator in liver diseases treatment. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2025, 398, 2365–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, Y.; Cao, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, H. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Donor and Dietary Fiber Intervention Collectively Contribute to Gut Health in a Mouse Model. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 842669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quaranta, G.; Guarnaccia, A.; Fancello, G.; Agrillo, C.; Iannarelli, F.; Sanguinetti, M.; Masucci, L. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation and Other Gut Microbiota Manipulation Strategies. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujol, A.; Sanchis, P.; Tamayo, M.I.; Godoy, S.; Calvó, P.; Olmos, A.; Andrés, P.; Speranskaya, A.; Espino, A.; Estremera, A.; et al. Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease and Cognitive Performance in Type 2 Diabetes: Basal Data from the Phytate, Neurodegeneration and Diabetes (PHYND) Study. Biomedicines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignot, V.; Chirica, C.; Tron, L.; Borowik, A.; Borel, A.L.; Rostaing, L.; Bouillet, L.; Decaens, T.; Guergour, D.; Costentin, C.E. Early screening for chronic liver disease: impact of a FIB-4 first integrated care pathway to identify patients with significant fibrosis. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 20720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.J.; Chen, Y.; Lin, J.Q.; Hu, R.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.Y.; Li, K.; Jiang, X.Y. Evidence summary of lifestyle interventions in adults with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1421386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Younossi, Z.M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Lazarus, J.V.; Wong, V.W.; Yilmaz, Y.; Duseja, A.; Eguchi, Y.; Castera, L.; Pessoa, M.G.; Oliveira, C.P.; et al. Global Consensus Recommendations for Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2025, 169, 1017–1032.e1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preshy, A.; Brown, J. A Bidirectional Association Between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2023, 52, 509–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iruzubieta, P.; Terán, Á.; Crespo, J.; Fábrega, E. Vitamin D deficiency in chronic liver disease. World J Hepatol 2014, 6, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Department for HIV T, Hepatitis and Sexually Transmitted Infections. Global Health Sector Strategies 2022–2030 Geneva: World Health Organization; 2022 [cited 2025 21 November]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-hiv-hepatitis-and-stis-programmes/strategies/global-health-sector-strategies.

- Rehm, J.; Shield, K.D. Global Burden of Alcohol Use Disorders and Alcohol Liver Disease. Biomedicines 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Zibaoui, R.; Díaz, L.A.; Idalsoaga, F.; Arab, J.P. Public Health Policies and Strategies to Prevent Alcohol-Related Morbidity and Mortality. Current Hepatology Reports 2025, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, V.D.; Alings, M.; Bruha, R.; Cortez-Pinto, H.; Dedoussis, G.V.; Doukas, M.; Francque, S.; Fournier-Poizat, C.; Gastaldelli, A.; Hankemeier, T.; et al. Global research initiative for patient screening on MASH (GRIPonMASH) protocol: rationale and design of a prospective multicentre study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e092731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Kleef, L.A.; Strandberg, R.; Pustjens, J.; Hammar, N.; Janssen, H.L.A.; Hagström, H.; Brouwer, W.P. FIB-4-based Referral Pathways Have Suboptimal Accuracy to identify Increased Liver Stiffness and Incident Advanced Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, E.A.; Mózes, F.E.; Jayaswal, A.N.A.; Zafarmand, M.H.; Vali, Y.; Lee, J.A.; Levick, C.K.; Young, L.A.J.; Palaniyappan, N.; Liu, C.-H.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of elastography and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with NAFLD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hepatology 2021, 75, 770–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikkelsen, A.C.D.; Kjærgaard, K.; Schapira, A.H.V.; Mookerjee, R.P.; Thomsen, K.L. The liver–brain axis in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2025, 10, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Xie, L.; Yang, W.; Feng, S.; Mao, W.; Ye, L.; Cheng, H.; Wu, X.; Mao, X. The role of brain–liver–gut Axis in neurological disorders. Burns & Trauma 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.C.; Tsan, Y.T.; Tsai, S.L.; Chang, C.J.; Wang, J.D.; Chen, P.C. Hepatitis C viral infection and the risk of dementia. Eur J Neurol 2014, 21, 1068–e1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Kang, L.; Yin, S.; Engström, G.; Wang, L.; Xu, W.; Xu, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, X. Association of MAFLD and MASLD with all-cause and cause-specific dementia: a prospective cohort study. Alzheimer's Research & Therapy 2024, 16, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javeed, A.; Dallora, A.L.; Berglund, J.S.; Ali, A.; Ali, L.; Anderberg, P. Machine Learning for Dementia Prediction: A Systematic Review and Future Research Directions. Journal of Medical Systems 2023, 47, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Exarchos, T.P.; Dimakopoulos, G.A.; Lazaros, K.; Krokidis, M.; Vrahatis, A.; Grammenos, G.; Avramouli, A.; Skolariki, K.; Adams, R.; Mahairaki, V.; et al. Five-year dementia prediction and decision support system based on real-world data. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience 2025, 17–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemulapalli, B.; Ghattu, M.; Atluri, K.; Lee, J.; Rustgi, V. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Applications in Liver Disease. Clinics in Liver Disease 2025, 29, 755–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, M. Treatment of liver fibrosis: Past, current, and future. World J Hepatol 2023, 15, 755–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Global Prevalence of Advanced Fibrosis |

Global Prevalence of Cirrhosis |

|

| Overall | 3.3% (95% CI, 2.4–4.2) | 1.3% (95% CI, 0.9–1.7) |

| In men | 3.5% (95% CI, 2.6–4.5) | 2.5% (95% CI, 1.0–4.0) |

| In women | 2.2% (95% CI, 1.3–3.1) | 0.9% (95% CI, 0.0–1.8) |

| Author, [Ref] | Method | Findings | Comment |

| Gao et al. [59] | Prospective cohort study of 431,699 UK Biobank participants with a mean follow-up of 8.65 ± 2.61 years. Cox proportional hazards analysis was used to assess associations of liver markers (ALT, AST, AST/ALT ratio, GGT), alcoholic liver disease, fibrosis, and cirrhosis with incident dementia. Additionally, linear regression was used to evaluate cognition and brain structure. | Each SD decrease in ALT is associated with a lower risk of all-cause dementia (HR 0.917, PFDR<0.001). Conversely, each SD increase in AST (HR 1.048, PFDR=0.010), AST/ALT ratio (HR 1.195, PFDR<0.001), GGT (HR 1.066, PFDR<0.001), alcoholic liver disease (HR 2.872, PFDR<0.001), and fibrosis/cirrhosis (HR 2.285, PFDR=0.002) increases the risk of dementia. Cognition shows a positive correlation with AST, AST/ALT, DBil, and GGT, and a negative correlation with ALT, albumin, and TBil. ALT, GGT, AST/ALT, and ALD are linked to cortical/subcortical changes in regions such as the hippocampus, amygdala, thalamus, pallidum, and fusiform (PFDR<0.05). | Large-scale evidence indicates that liver dysfunction predicts dementia and cognitive impairment, and is associated with cortical/subcortical changes |

| Weinstein et al. [60] | A cross-sectional meta-analysis was conducted on 5660 individuals with NAFLD and 3022 individuals with fibrosis, who were free of dementia and stroke, from the FHS, RS, and SHIP cohorts. NAFLD was assessed using abdominal imaging, while fibrosis was assessed using FibroScan. Linear regression was used to analyze total brain volume, gray matter volume, hippocampal volumes, and WMH. | NAFLD is associated with smaller total brain volume (β=-3.5, 95% CI -5.4 to -1.7), gray matter volume (β=-1.9, 95% CI -3.4 to -0.3), and cortical gray matter volume (β=-1.9, 95% CI -3.7 to -0.01). Fibrosis (liver stiffness ≥8.2 kPa) is linked to smaller total brain volume (β=-7.3, 95% CI -11.1 to -3.5). There is low heterogeneity. | This suggests that NAFLD and fibrosis may play a role in brain aging. |

| Weinstein et al. [61] | Participants from the Framingham Offspring and Third Generation cohorts underwent amyloid (11C-PiB) and tau (18F-Flortaucipir) PET scans, as well as abdominal CT scans or had FIB-4 data. Linear regression was used to assess associations of NAFLD and FIB-4 with regional tau and amyloid-β levels, adjusting for confounders. | FIB-4 is associated with increased rhinal tau levels (β=1.03±0.33, p=0.002). In NAFLD participants, higher FIB-4 levels are correlated with increased tau in regions such as the inferior temporal (β=2.01±0.47, p<0.001), parahippocampal (β=1.60±0.53, p=0.007), entorhinal (β=1.59±0.47, p=0.003), and rhinal cortex (β=1.60±0.42, p=0.001), as well as increased overall amyloid-β (β=1.93±0.47, p<0.001) and in regions like inferior temporal/parahippocampal. | Liver fibrosis, as opposed to NAFLD alone, could drive early Alzheimer’s pathology, including tau accumulation in certain brain regions. |

| Fan et al. [62] | A cross-sectional study was conducted on 29,195 UK Biobank participants aged 45–82 who underwent T1, T2 FLAIR, and DTI MRI scans. MASLD was defined as MRI-PDFF ≥5% plus ≥1 cardiometabolic criterion. Multiple linear regression was used to assess total and subcortical gray matter, AD-signature cortical thickness, WMH, FA, and MD. | MASLD is associated with smaller total/subcortical gray matter (p<0.05) and reduced cortical thickness in AD signature/regions (β=-0.04, 95% CI -0.07, -0.01). Higher total WMH volume (β=0.12, 95% CI 0.10, 0.15), increased global FA (β=0.05, 95% CI 0.03, 0.08), and reduced global MD (β=-0.04, 95% CI -0.07, -0.01). | MASLD affects gray and white matter integrity, further supporting a connection between liver metabolic dysfunction and brain structure. |

|

Test (calculation) |

Condition | Cutoff | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity/NPV% | Reference |

| APRI (AST level ÷ ULN ÷ platelet count) |

Significant fibrosis due to HBV Cirrhosis due to HCV |

> 0.35 >1.0 |

78 76 |

63 71 |

Yue et al. [105] Shaheen et al. [106] |

| FIB-4 (age × AST level) ÷ (platelet count × √ALT level) |

Significant fibrosis due to HCV | <1.45 >3.25 |

60-92 11-54 |

52-95 91-98 |

Xu et al. [107] |

| NFS (−1.675 + (0.037 × age) + (0.094 × BMI) + (1.13 × IR or diabetes [yes = 1, no = 0]) + (0.99 × AST:ALT ratio) − (0.013 × platelet count) − (0.66 × albumin) |

Identification of individuals with MASLD at risk of developing fibrosis | -0.835 | 100 | 70 | Torres et al. [108] |

| Author, year [Ref] | Method | Findings | Conclusion |

| Gaur, 2023[119] | Meta-analysis of 10 studies | In CSF, concentrations of NfL (SMD=0.69 [0.56, 0.83]), GFAP (SMD=0.41 [0.07, 0.75]), and HFABP (SMD=0.57 [0.26, 0.89]) were elevated in individuals with MCI. In blood, increased concentrations of T-tau (SMD=0.19 [0.09, 0.29]), NfL (SMD=0.41 [0.32, 0.49]), and GFAP (SMD=0.39 [0.23, 0.55]) were found in MCI. |

Levels of NfL and GFAP can be measured in both CSF and blood. Monitoring these biomarkers may provide valuable information about neurodegeneration in individuals with MCI. |

| Ma, 2024[120] | Meta-analysis of 63 studies | The following biomarkers were significantly higher in patients with PSCI compared to the non-PSCI group: Hcy (p<0.00001), CRP (p=0.0008), UA (p=0.02), IL-6 (p=0.005), Cys-C (p=0.0001), creatinine (p<0.00001) and TNF-α (p=0.02). | Integrating of neuroimaging and neuropsychological assessments with blood biomarker levels is crucial for evaluating the risk of PSCI. |

| Chen, 2024[121] | Meta-analysis of 13 studies | A notable elevation in MI concentration was found, along with reductions in Glu, Glx, and NAA/Cr ratios in DCI. | These biomarkers are highly sensitive metabolic indicators for assessing the progression of DCI. |

| Huang, 2025[122] | Meta-analysis of 30 studies | Peripheral Aβ42 levels, the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, NfL, and S100B show significant differences between VCI and non-VCI groups. | Peripheral Aβ42, the Aβ42/Aβ40 ratio, NfL, and S100B are potential blood biomarkers for VCI. |

| Risk Prediction Model | Parameters Included | Comment | References |

| CAIDE Dementia Risk Score | Age, sex, Education Level, Physical Inactivity, SBP, TChol, BMI. | Originally developed to predict the 20-year dementia risk among middle-aged Finnish individuals, this is the most established and frequently used mid-life risk score for predicting future dementia risk. | Kivipelto et al. [123] Farkas et al. [124] |

| ANU-ADRI | Age, sex, education level, BMI, diabetes, depression, TChol, traumatic brain injury, smoking, alcohol intake, social engagement, physical activity, cognitive activity, fish intake, and pesticide exposure. | In contrast to constructing risk indices using individual cohort studies, this methodology enables the inclusion of a broader range of risk factors, enhances the generalizability of outcomes, and facilitates the integration of interactions informed by research conducted across various stages of the life course. | Anstey et al. [125] |

| UKBDRS | Age, education, parental history of dementia, material deprivation, a history of diabetes, stroke, depression, hypertension, high cholesterol, household occupancy, and sex | This is an easy-to-use tool to identify individuals at risk of dementia in the UK. Further research is required to determine the validity of this score in other populations. | Anaturk et al. [126] |

| CogDrisk tool | Age, sex, education, HTN, midlife obesity, midlife high cholesterol, diabetes, insufficient physical activity, depression, TBI, AF, smoking, social engagement, cognitive engagement, fish consumption, stroke, and insomnia. | A comprehensive risk assessment tool for AD, VaD, and any other type of dementia, which will be applicable in high and low-resource settings. | Anstey et al. [127,128] |

| LIBRA and LIBRA2 | LIBRA focuses on 12 modifiable lifestyle and vascular risk factors, while the updated LIBRA2 version adds three more: hearing impairment, social contact, and sleep. | LIBRA2 demonstrates improved capability in identifying individuals at elevated risk for dementia and serves as an effective tool for public health initiatives focused on reducing dementia risk. | Rosenau et al. [129] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).