Submitted:

06 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Detection of Stenotrophomonas Isolates

2.2. Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) and Analysis

2.3. Growth Kinetics at 37 °C

2.4. Assessment of Biofilm Production Through Crystal Violet Assay

2.5. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.6. Genetic Characterization by Whole Genome Sequencing

2.7. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

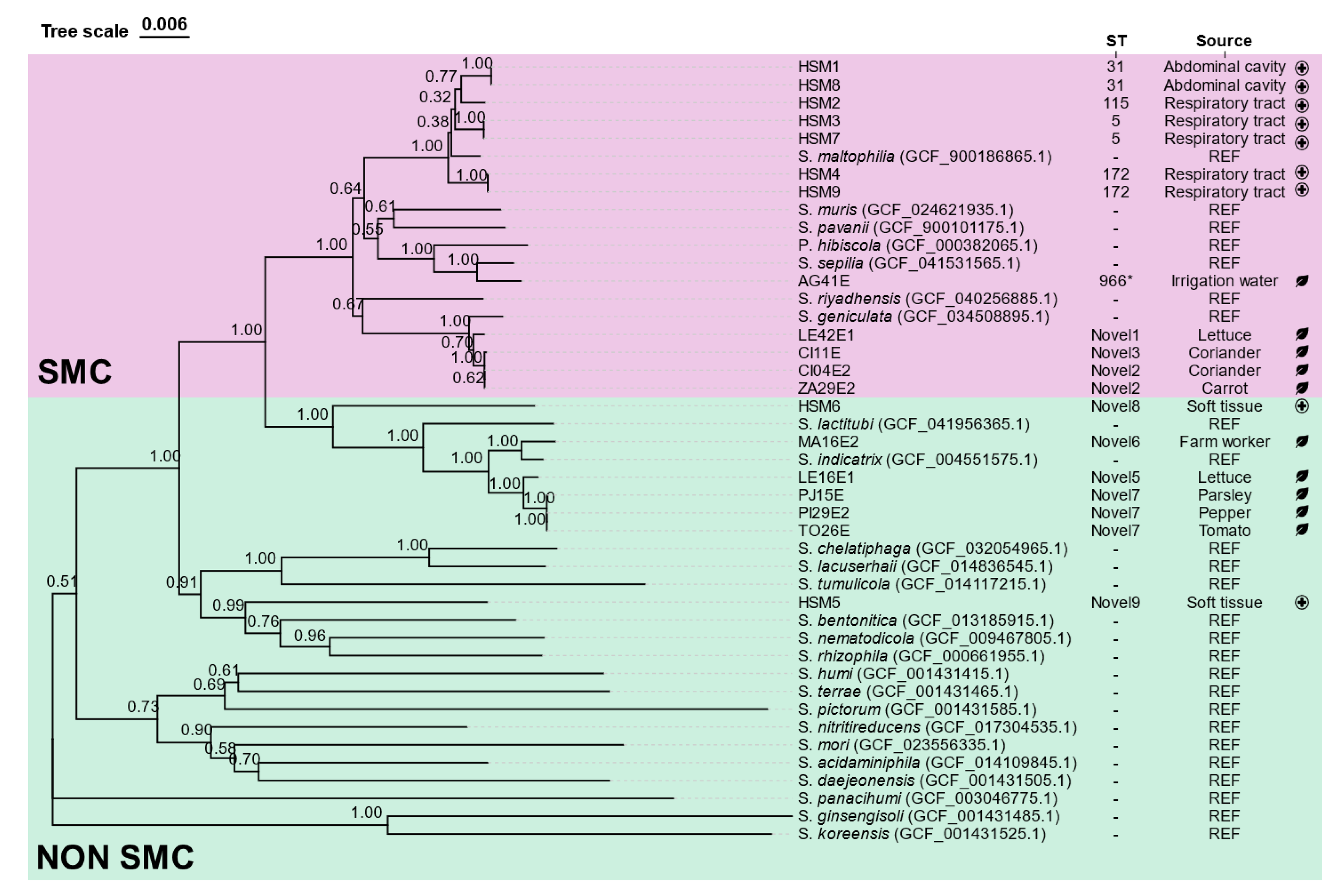

3.1. Isolation and Taxonomic Classification of Stenotrophomonas spp. Isolates

3.2. MLST Analysis

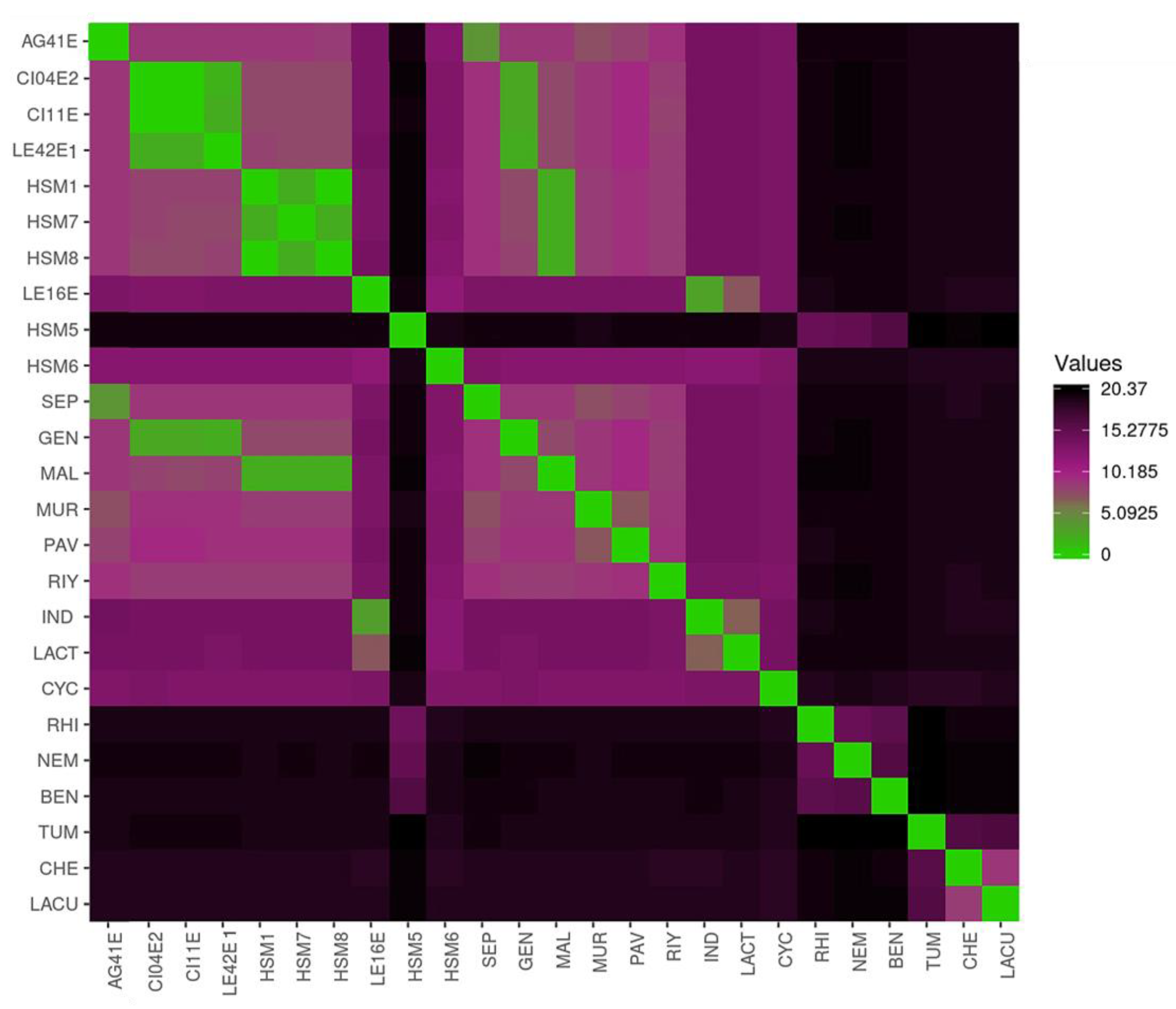

3.3. Average Nucleotide Identity (ANIb) Analysis

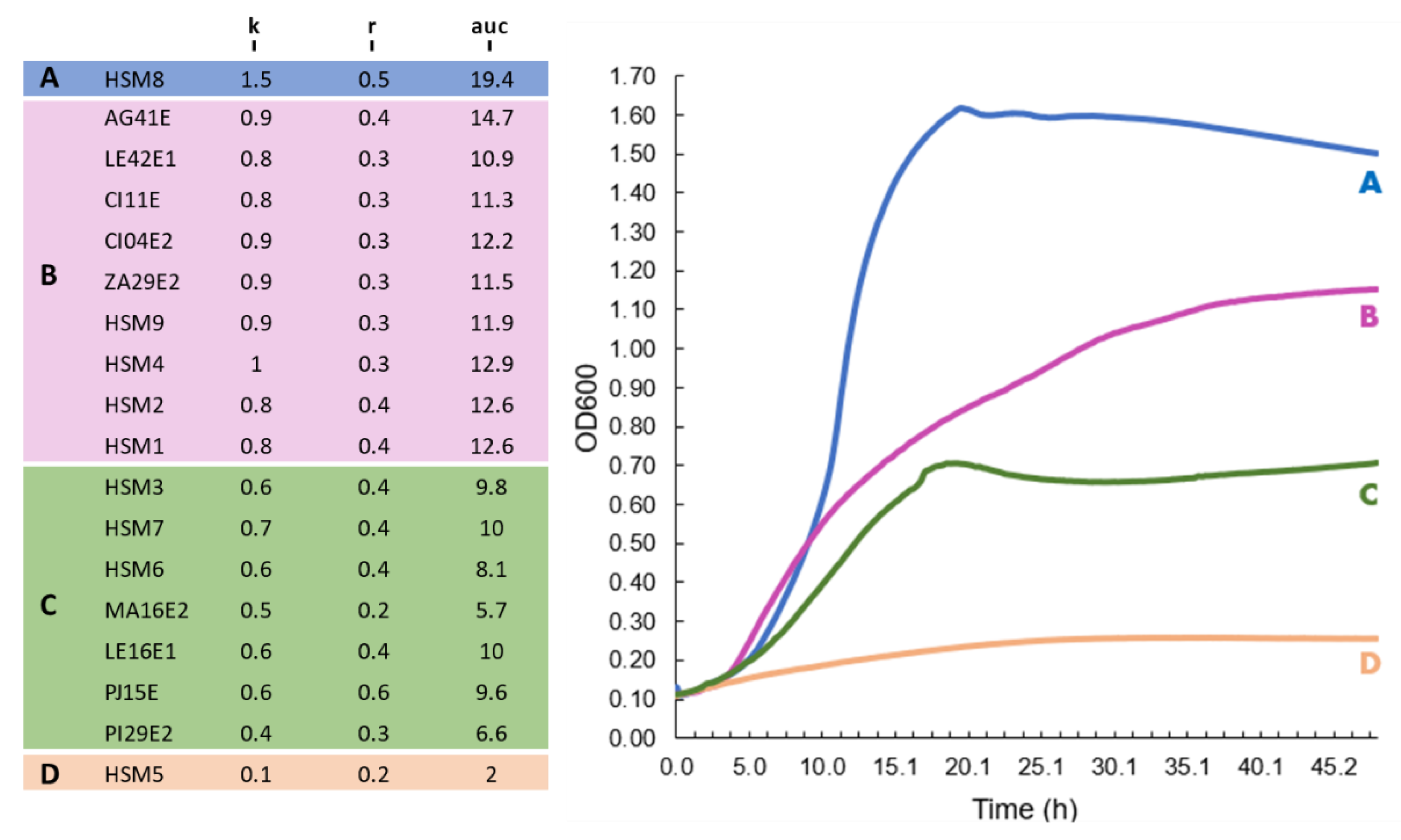

3.4. Growth Kinetics at 37 °C

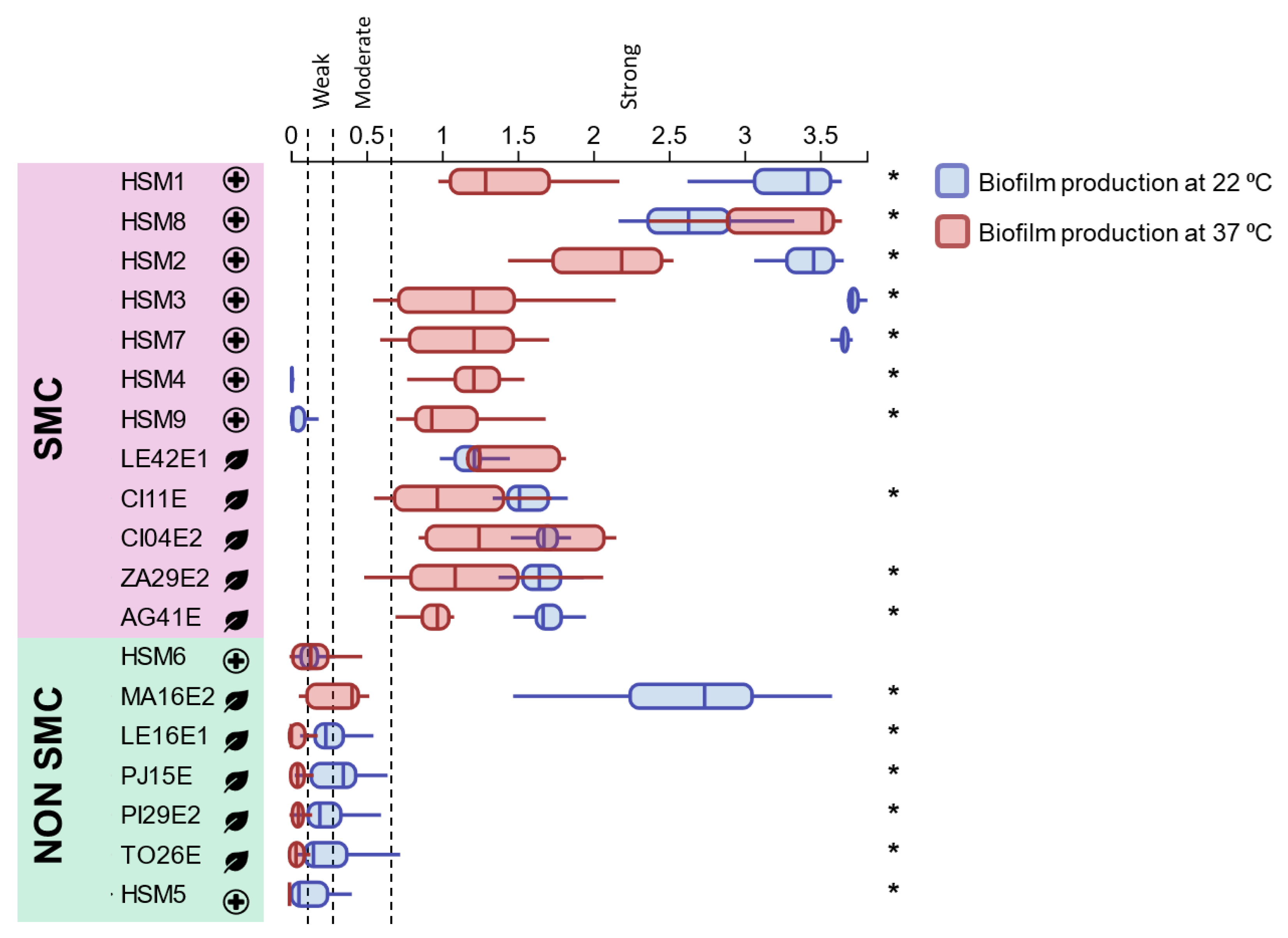

3.5. Biofilm-Forming Ability

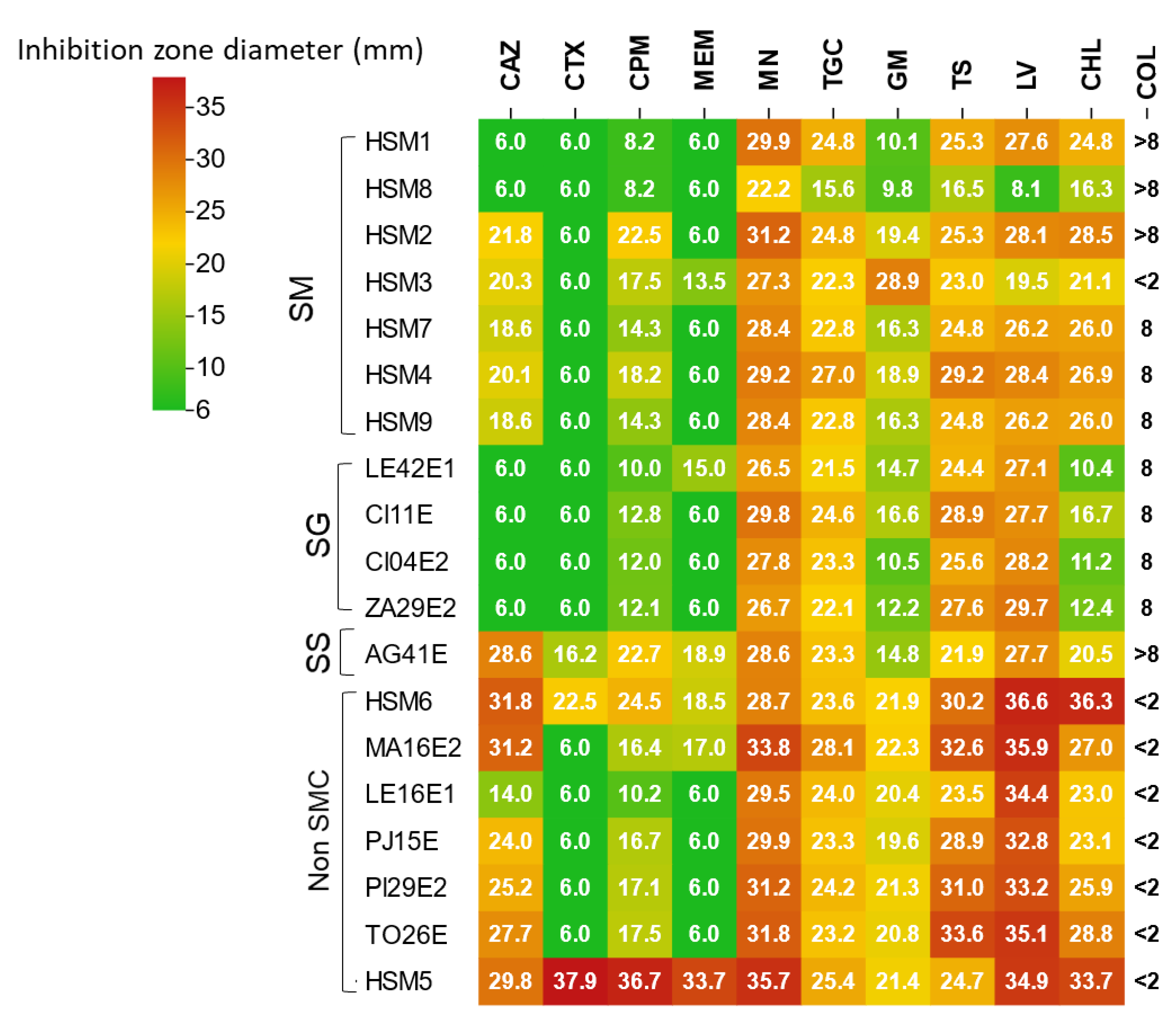

3.6. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

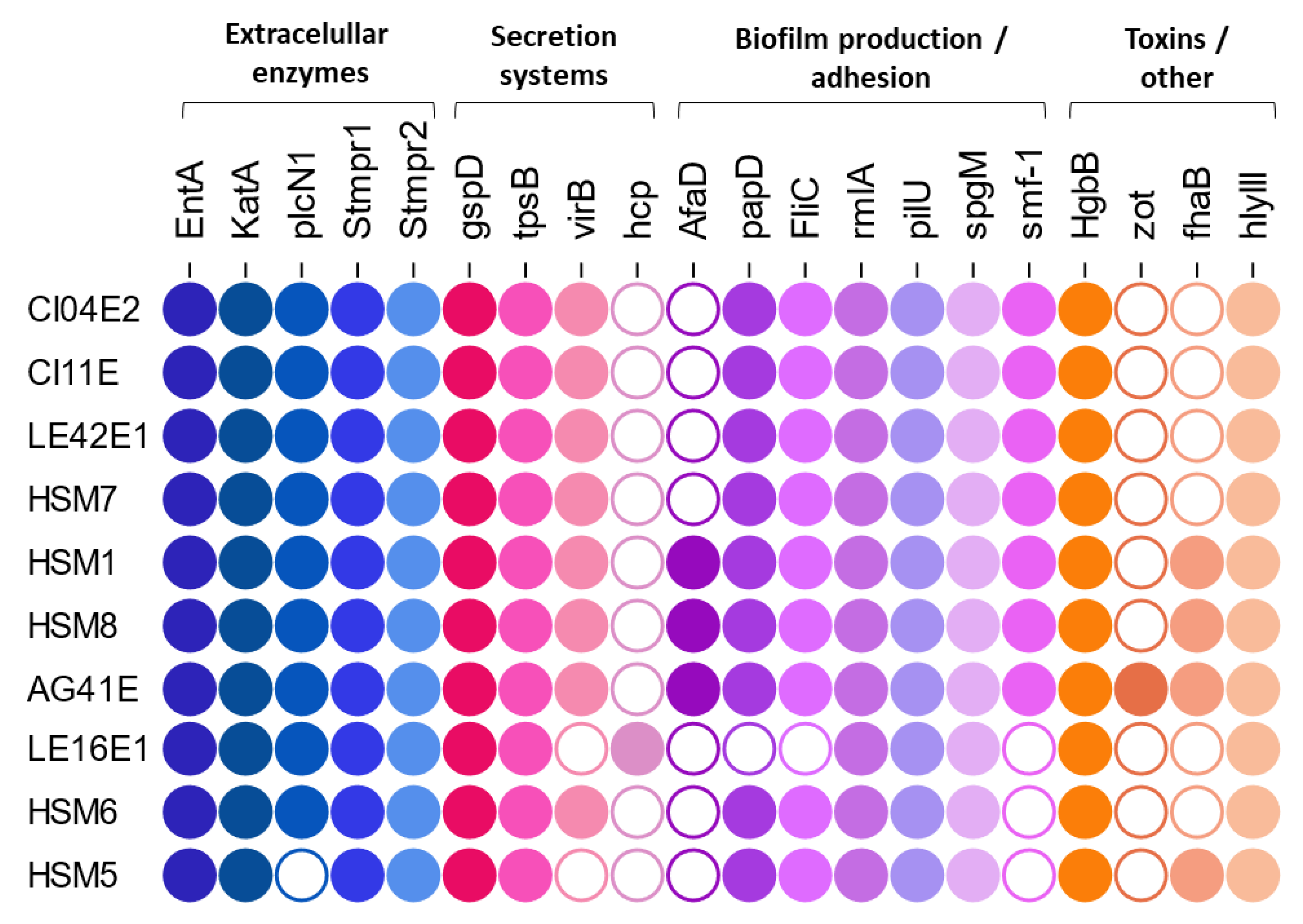

3.7. Detection of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SMC | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia complex |

| ANI | Average nucleotide identity |

| MLST | Multilocus sequence typing |

| ST | Sequence type |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| T2SS | Type II Secretion System |

| T4SS | Type IV Secretion System |

References

- Gales, A.C.; Seifert, H.; Gur, D.; Castanheira, M.; Jones, R.N.; Sader, H.S. Antimicrobial Susceptibility of Acinetobacter Calcoaceticus–Acinetobacter Baumannii Complex and Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Clinical Isolates: Results From the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (1997–2016). Open Forum Infect Dis 2019, 6, S34–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifonova, A.; Strateva, T. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia – a Low-Grade Pathogen with Numerous Virulence Factors. Infect Dis 2019, 51, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V.; Patil, P.P.; Bansal, K.; Kumar, S.; Kaur, A.; Singh, A.; Korpole, S.; Singhal, L.; Patil, P.B. Description of Stenotrophomonas Sepilia Sp. Nov., Isolated from Blood Culture of a Hospitalized Patient as a New Member of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Complex. New Microbes New Infect 2021, 43, 100920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailovich, V.; Heydarov, R.; Zimenkov, D.; Chebotar, I. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Virulence: A Current View. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1385631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Alvarez, L.J.; Martínez-Flores, I.; Bustos, P.; Gómez-García, A.; Gutiérrez-Castellanos, S.; Poot-Hernández, A.C.; Arredondo-Santoyo, M. Sequencing and Description of the Genome of a Strain of Stenotrophomonas Geniculata Isolated from a Patient Infected with COVID-19 at Hospital Regional No.1 de Charo, Michoacán, México. MicroPubl Biol 2024, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez, J.I.G.; Costa, S.F. Risk Factors Associated with Mortality of Infections Caused by Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia: A Systematic Review. Journal of Hospital Infection 2008, 70, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Lin, L.; Kuo, S. Risk Factors for Mortality in Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Bacteremia–a Meta-Analysis. Infect Dis 2024, 56, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajdács, M.; Urbán, E. Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia in Respiratory Tract Samples: A 10-Year Epidemiological Snapshot. Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol 2019, 6, 233339281987077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoletti, M.; Iacobino, A.; Prosseda, G.; Fiscarelli, E.; Zarrilli, R.; De Carolis, E.; Petrucca, A.; Nencioni, L.; Colonna, B.; Casalino, M. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Strains from Cystic Fibrosis Patients: Genomic Variability and Molecular Characterization of Some Virulence Determinants. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2011, 301, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.P.; Monchy, S.; Cardinale, M.; Taghavi, S.; Crossman, L.; Avison, M.B.; Berg, G.; van der Lelie, D.; Dow, J.M. The Versatility and Adaptation of Bacteria from the Genus Stenotrophomonas. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2009, 7, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deredjian, A.; Alliot, N.; Blanchard, L.; Brothier, E.; Anane, M.; Cambier, P.; Jolivet, C.; Khelil, M.N.; Nazaret, S.; Saby, N.; et al. Occurrence of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia in Agricultural Soils and Antibiotic Resistance Properties. Res Microbiol 2016, 167, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S. V.; Edwards, D.; Vaughn, E.L.; Escobar, V.; Ali, S.; Doss, J.H.; Steyer, J.T.; Scott, S.; Bchara, W.; Bruns, N.; et al. Expanding the Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Complex: Phylogenomic Insights, Proposal of Stenotrophomonas Forensis Sp. Nov. and Reclassification of Two Pseudomonas Species. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2024, 74, 006602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yu, K.; Huang, Z.; Liu, X.; Mei, L.; Ren, X.; Bai, X.; Gao, H.; Sun, Z.; Liu, X.; et al. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Complex: Insights into Evolutionary Relationships, Global Distribution and Pathogenicity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.L.; Wang, R.B. Revised Taxonomic Classification of the Stenotrophomonas Genomes, Providing New Insights into the Genus Stenotrophomonas. Front Microbiol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monardo, R.; Mojica, M.F.; Ripa, M.; Aitken, S.L.; Bonomo, R.A.; van Duin, D. How Do I Manage a Patient with Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Infection? Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostanghadiri, N.; Sholeh, M.; Navidifar, T.; Dadgar-Zankbar, L.; Elahi, Z.; van Belkum, A.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Global Mapping of Antibiotic Resistance Rates among Clinical Isolates of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2024, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamek, M.; Linke, B.; Schwartz, T. Virulence Genes in Clinical and Environmental Stenotrophonas Maltophilia Isolates: A Genome Sequencing and Gene Expression Approach. Microb Pathog 2014, 67–68, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, A.; Aslanimehr, M.; Yaseri, M.; Shadkam, M.; Douraghi, M. Distribution of smf-1, rmlA, spgM and rpfF Genes among Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates in Relation to Biofilm-Forming Capacity. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2020, 23, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.; Girón, J.A.; Yañez, J.A.; Cedillo, M.L. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia and Its Ability to Form Biofilms. Microbiol Res 2022, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, L.; Kaur, P.; Gautam, V. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia: From Trivial to Grievous. Indian J Med Microbiol 2017, 35, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, J.P.R.; Sanchez, D.G.; Gallo, I.F.L.; Stehling, E.G. Characterization of Acquired Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in Environmental Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates from Brazil. Microbial Drug Resistance 2019, 25, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimkaitė, L.; Armalytė, J.; Skerniškytė, J.; Sužiedėlienė, E. The Toxin-Antitoxin Systems of the Opportunistic Pathogen Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia of Environmental and Clinical Origin. Toxins (Basel) 2020, 12, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, G.; Martinez, J.L. Friends or Foes: Can We Make a Distinction between Beneficial and Harmful Strains of the Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Complex? Front Microbiol 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, S.; Biehler, K.; Jonas, D. A Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Multilocus Sequence Typing Scheme for Inferring Population Structure. J Bacteriol 2009, 191, 2934–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolley, K.A.; Bray, J.E.; Maiden, M.C.J. Open-Access Bacterial Population Genomics: BIGSdb Software, the PubMLST.Org Website and Their Applications. Wellcome Open Res 2018, 3, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Mol Biol Evol 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepanović, S.; Vuković, D.; Hola, V.; Di Bonaventura, G.; Djukić, S.; Ćirković, I.; Ruzicka, F. Quantification of Biofilm in Microtiter Plates: Overview of Testing Conditions and Practical Recommendations for Assessment of Biofilm Production by Staphylococci. APMIS 2007, 115, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, M.; Rosselló-Móra, R.; Oliver Glöckner, F.; Peplies, J. JSpeciesWS: A Web Server for Prokaryotic Species Circumscription Based on Pairwise Genome Comparison. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, K.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Ye, L.Y.; Yang, J. Molecular Epidemiology, Genetic Diversity, Antibiotic Resistance and Pathogenicity of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Complex from Bacteremia Patients in a Tertiary Hospital in China for Nine Years. Front Microbiol 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babicki, S.; Arndt, D.; Marcu, A.; Liang, Y.; Grant, J.R.; Maciejewski, A.; Wishart, D.S. Heatmapper: Web-Enabled Heat Mapping for All. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, W147–W153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, G.; Cai, R.; Hu, Z.; Wang, H. Tree Visualization By One Table (TvBOT): A Web Application for Visualizing, Modifying and Annotating Phylogenetic Trees. Nucleic Acids Res 2023, 51, W587–W592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, M.; Hasse, D.; Berg, G. Detection of a Phage Genome Carrying a Zonula Occludens like Toxin Gene (Zot) in Clinical Isolates of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia. Arch Microbiol 2006, 185, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Aitken, S.L.; Bonomo, R.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Van Duin, D.; Clancy, C.J. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidance on the Treatment of AmpC β-Lactamase–Producing Enterobacterales, Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter Baumannii, and Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2022, 74, 2089–2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, P.P.; Kumar, S.; Midha, S.; Gautam, V.; Patil, P.B. Taxonogenomics Reveal Multiple Novel Genomospecies Associated with Clinical Isolates of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia. Microb Genom 2018, 4, e000207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauviat, A.; Abrouk, D.; Brothier, E.; Muller, D.; Meyer, T.; Favre-Bonté, S. Genomic and Phylogenetic Re-Assessment of the Genus Stenotrophomonas: Description of Stenotrophomonas Thermophila Sp. Nov., and the Proposal of Parastenotrophomonas Gen. Nov., Pseudostenotrophomonas Gen. Nov., Pedostenotrophomonas Gen. Nov., and Allostenotrophomonas Gen. Nov. Syst Appl Microbiol 2025, 48, 126630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Sánchez, L.E.; Vinuesa, P. Evolutionary Genetic Analysis Uncovers Multiple Species with Distinct Habitat Preferences and Antibiotic Resistance Phenotypes in the Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Complex. Front Microbiol 2017, 8, 245563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamek, M.; Overhage, J.; Bathe, S.; Winter, J.; Fischer, R.; Schwartz, T. Genotyping of Environmental and Clinical Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates and Their Pathogenic Potential. PLoS One 2011, 6, e27615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröschel, M.I.; Meehan, C.J.; Barilar, I.; Diricks, M.; Gonzaga, A.; Steglich, M.; Conchillo-Solé, O.; Scherer, I.C.; Mamat, U.; Luz, C.F.; et al. The Phylogenetic Landscape and Nosocomial Spread of the Multidrug-Resistant Opportunist Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia. Nature Communications 2020, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, V.; Sharma, M.; Singhal, L.; Kumar, S.; Kaur, P.; Tiwari, R.; Ray, P. MALDI-TOF Mass Spectrometry: An Emerging Tool for Unequivocal Identification of Non-Fermenting Gram-Negative Bacilli. Indian J Med Res 2017, 145, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahnoor; Noor-Ul-Ain; Arshad, F.; Ahsan, T.; Alharbi, S.A.; Ansari, M.J.; Khan, I.; Alshiekheid, M.; Sabour, A.A.A. Whole Genome Analysis of Stenotrophomonas Geniculata MK2 and Antagonism against Botrytis Cinerea in Strawberry. International Microbiology 2024, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercole, T.G.; Kava, V.M.; Petters-Vandresen, D.A.L.; Ribeiro, R.A.; Hungria, M.; Galli, L.V. Unveiling Agricultural Biotechnological Prospects: The Draft Genome Sequence of Stenotrophomonas Geniculata LGMB417. Curr Microbiol 2024, 81, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Ding, W.J.; Xu, L.; Sun, J.Q. A Comprehensive Comparative Genomic Analysis Revealed That Plant Growth Promoting Traits Are Ubiquitous in Strains of Stenotrophomonas. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1395477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omomowo, O.I.; Babalola, O.O. Genomic Insights into Two Endophytic Strains: Stenotrophomonas Geniculata NWUBe21 and Pseudomonas Carnis NWUBe30 from Cowpea with Plant Growth-Stimulating Attributes. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 12953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, N.T.; Nguyen, T.T.A.; Vu, T.H.N.; Le, T.T.X.; Nguyen, T.T.L.; Chu, H.H.; Phi, Q.T. Phenotypic and Genomic Analysis Deciphering Plant Growth Promotion and Oxidative Stress Alleviation of Stenotrophomonas Sepilia ZH16 Isolated from Rice. Microbiology (Russian Federation) 2025, 94, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Shekhar, N.; Singhal, L.; Rawat, R.S.; Duseja, A.; Verma, R.K.; Bansal, K.; Kour, I.; Biswas, S.; Rajni, E.; et al. Susceptibility of Clinical Isolates of Novel Pathogen Stenotrophomonas Sepilia to Novel Benzoquinolizine Fluoroquinolone Levonadifloxacin. JAC Antimicrob Resist 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, O.O.; Adeleke, B.S.; Ayangbenro, A.S.; Baltrus, D.A. Draft Genome Sequencing of Stenotrophomonas Indicatrix BOVIS40 and Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia JVB5, Two Strains with Identifiable Genes Involved in Plant Growth Promotion. Microbiol Resour Announc 2021, 10, e00482-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeleke, B.S.; Ayangbenro, A.S.; Babalola, O.O. Genomic Assessment of Stenotrophomonas Indicatrix for Improved Sunflower Plant. Curr Genet 2021, 67, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Schünemann, W.; Fuß, J.; Kämpfer, P.; Lipski, A. Stenotrophomonas Lactitubi Sp. Nov. and Stenotrophomonas Indicatrix Sp. Nov., Isolated from Surfaces with Food Contact. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2018, 68, 1830–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmann, J.; Mamat, U.; Abda, E.M.; Kirchhoff, L.; Streit, W.R.; Schaible, U.E.; Niemann, S.; Kohl, T.A. Analysis of Phylogenetic Variation of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Reveals Human-Specific Branches. Front Microbiol 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinski, A.; Zur, J.; Hasterok, R.; Hupert-Kocurek, K. Comparative Genomics of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia and Stenotrophomonas Rhizophila Revealed Characteristic Features of Both Species. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020, 21, 4922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wu, H.; Ma, C.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, S.; Shi, D.; Chen, T.; Yang, D.; et al. Emergence of Colistin-Resistant Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia with High Virulence in Natural Aquatic Environments. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Qin, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Ying, C. Molecular Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Infections in a Chinese Teaching Hospital. BMC Microbiol 2020, 20, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Shen, X.; Wang, H.; Guo, R.; Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Comparative Genomics Analysis of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Strains from a Community. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1266295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mojica, M.F.; Rutter, J.D.; Taracila, M.; Abriata, L.A.; Fouts, D.E.; Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Walsh, T.J.; Lipuma, J.J.; Vila, A.J.; Bonomo, R.A. Population Structure, Molecular Epidemiology, and β-Lactamase Diversity among Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates in the United States. mBio 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corlouer, C.; Lamy, B.; Desroches, M.; Ramos-Vivas, J.; Mehiri-Zghal, E.; Lemenand, O.; Delarbre, J.M.; Decousser, J.W.; Aberanne, S.; Belmonte, O.; et al. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Healthcare-Associated Infections: Identification of Two Main Pathogenic Genetic Backgrounds. Journal of Hospital Infection 2017, 96, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.H.; Sung, J.Y.; Kwon, K.C.; Koo, S.H. Expression of Sme Efflux Pumps and Multilocus Sequence Typing in Clinical Isolates of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia. Ann Lab Med 2011, 32, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, P.; Starcher, M.R.; Thallinger, G.G.; Zachow, C.; Müller, H.; Berg, G. Stenotrophomonas Comparative Genomics Reveals Genes and Functions That Differentiate Beneficial and Pathogenic Bacteria. BMC Genomics 2014, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompilio, A.; Ranalli, M.; Piccirilli, A.; Perilli, M.; Vukovic, D.; Savic, B.; Krutova, M.; Drevinek, P.; Jonas, D.; Fiscarelli, E. V.; et al. Biofilm Formation among Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates Has Clinical Relevance: The ANSELM Prospective Multicenter Study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimkaitė, L.; Drevinskaitė, R.; Krinickis, K.; Sužiedėlienė, E.; Armalytė, J. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia of Clinical Origin Display Higher Temperature Tolerance Comparing with Environmental Isolates. Virulence 2025, 16, 2498669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahid, I.K.; Ha, S. Do A Review of Microbial Biofilms of Produce: Future Challenge to Food Safety. Food Science and Biotechnology 2012, 21, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, E.; García, C.; Friedman, L.; De Rossi, B.P. The Rpf/DSF Signalling System of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Positively Regulates Biofilm Formation, Production of Virulence-Associated Factors and β-Lactamase Induction. FEMS Microbiol Lett 2019, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Córdova, A.; Mancilla-Rojano, J.; Luna-Pineda, V.M.; Escalona-Venegas, G.; Cázares-Domínguez, V.; Ormsby, C.; Franco-Hernández, I.; Zavala-Vega, S.; Hernández, M.A.; Medina-Pelcastre, M.; et al. Molecular Epidemiology, Antibiotic Resistance, and Virulence Traits of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Strains Associated With an Outbreak in a Mexican Tertiary Care Hospital. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, F.; De Gregorio, E.; Colonna, B.; Di Nocera, P.P. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Genomes: A Start-up Comparison. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 2009, 299, 535–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, R.; Beard, A.; Harrigan, O.; Ramos-Hegazy, L.; Mattoo, S.; Anderson, G.G. Role of SMF-1 and Cbl Pili in Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Biofilm Formation. Biofilm 2025, 9, 100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, S.W.; Figueiredo, T.P.; Bessa, M.C.; Pagnussatti, V.E.; Ferreira, C.A.S.; Oliveira, S.D. Isolation and Characterization of. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates from a Brazilian Hospital 2016, 22, 688–695. Available online: https://home.liebertpub.com/mdr. [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.L.; Kulasekara, B.; Rietsch, A.; Boyd, D.; Smith, R.S.; Lory, S. A Signaling Network Reciprocally Regulates Genes Associated with Acute Infection and Chronic Persistence in Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Dev Cell 2004, 7, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, S.; Kuchma, S.L.; O’Toole, G.A. Keeping Their Options Open: Acute versus Persistent Infections. J Bacteriol 2006, 188, 1211–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bonaventura, G.; Prosseda, G.; Del Chierico, F.; Cannavacciuolo, S.; Cipriani, P.; Petrucca, A.; Superti, F.; Ammendolia, M.G.; Concato, C.; Fiscarelli, E.; et al. Molecular Characterization of Virulence Determinants of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Strains Isolated from Patients Affected by Cystic Fibrosis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2007, 20, 529–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, R.; Aungkur, N.Z.; Anderson, G.G. A Guide to Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Virulence Capabilities, as We Currently Understand Them. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2023, 13, 1322853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzzau, S.; Cappuccinelli, P.; Fasano, A. Expression of Vibrio Cholerae Zonula Occludens Toxin and Analysis of Its Subcellular Localization. Microb Pathog 1999, 27, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrova, M.; Shcherbatova, N.; Kurakov, A.; Mindlin, S. Genomic Characterization and Integrative Properties of PhiSMA6 and PhiSMA7, Two Novel Filamentous Bacteriophages of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia. Arch Virol 2014, 159, 1293–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, J.J.; Phan, I.Q.H.; Scheib, H.; Subramanian, S.; Edwards, T.E.; Lehman, S.S.; Piitulainen, H.; Rahman, M.S.; Rennoll-Bankert, K.E.; Staker, B.L.; et al. Structural Insight into How Bacteria Prevent Interference between Multiple Divergent Type IV Secretion Systems. mBio 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nas, M.Y.; White, R.C.; DuMont, A.L.; Lopez, A.E.; Cianciottoa, N.P. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Encodes a VirB/VirD4 Type IV Secretion System That Modulates Apoptosis in Human Cells and Promotes Competition against Heterologous Bacteria, Including Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Infect Immun 2019, 87, e00457-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nas, M.Y.; Gabell, J.; Cianciotto, N.P. Effectors of the Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Type IV Secretion System Mediate Killing of Clinical Isolates of Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. mBio 2021, 12, e01502-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.C.; Lee, B.; Miller, S.; Yan, J.; Maeusli, M.; She, R.; Luna, B.M.; Spellberg, B. 1113. Ceftazidime Retains in Vivo Efficacy against Strains of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia for Which Traditional Testing Predicts Resistance. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Treviño, S.; Bocanegra-Ibarias, P.; Camacho-Ortiz, A.; Morfín-Otero, R.; Salazar-Sesatty, H.A.; Garza-González, E. Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Biofilm: Its Role in Infectious Diseases. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2019, 17, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, J.; Wong, D.W. Antimicrobial Treatment Strategies for Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia: A Focus on Novel Therapies. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Valkimadi, P.E.; Huang, Y.T.; Matthaiou, D.K.; Hsueh, P.R. Therapeutic Options for Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Infections beyond Co-Trimoxazole: A Systematic Review. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2008, 62, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadashi, M.; Hajikhani, B.; Nazarinejad, N.; Noorisepehr, N.; Yazdani, S.; Hashemi, A.; Hashemizadeh, Z.; Goudarzi, M.; Fatemeh, S. Global Prevalence and Distribution of Antibiotic Resistance among Clinical Isolates of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Glob Antimicrob Resist 2023, 34, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgarm Shams-Abadi, A.; Mohammadian-Hafshejani, A.; Paterson, D.L.; Arash, R.; Asadi Farsani, E.; Taji, A.; Heidari, H.; Shahini Shams Abadi, M. The Prevalence of Colistin Resistance in Clinical Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Isolates Worldwide: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Microbiol 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Ni, W.; Wang, R.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B. Frequency and Genetic Determinants of Tigecycline Resistance in Clinically Isolated Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia in Beijing, China. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 337267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gil, T.; Martínez, J.L.; Blanco, P. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia : A Review of Current Knowledge. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2020, 18, 335–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.F.; Chang, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, Z.X.; Shao, Y.B.; Shi, W.; Li, X.; Li, J. Bin Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Resistance to Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole Mediated by Acquisition of Sul and DfrA Genes in a Plasmid-Mediated Class 1 Integron. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2011, 37, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.T.; Huang, Y.W.; Chen, S.J.; Chang, C.W.; Yang, T.C. The SmeYZ Efflux Pump of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia Contributes to Drug Resistance, Virulence-Related Characteristics, and Virulence in Mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2015, 59, 4067–4073. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.X.; Yu, C.M.; Hsu, S.T.; Wang, C.H. Emergence of Concurrent Levofloxacin- and Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole-Resistant Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia: Risk Factors and Antimicrobial Sensitivity Pattern Analysis from a Single Medical Center in Taiwan. Journal of Microbiology, Immunology and Infection 2022, 55, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauviat, A.; Meyer, T.; Favre-Bonté, S. Versatility of Stenotrophomonas Maltophilia: Ecological Roles of RND Efflux Pumps. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerezer, V.G.; Bando, S.Y.; Pasternak, J.; Franzolin, M.R.; Moreira-Filho, C.A. Phylogenetic Analysis of Stenotrophomonas Spp. Isolates Contributes to the Identification of Nosocomial and Community-Acquired Infections. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 151405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Isolate | MALDI-TOF | MLSA/AniB | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG41E | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas sepilia | Irrigation Water | Environmental / Fresh produce |

| CI04E2 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas geniculata | Coriander | |

| CI11E | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas geniculata | Coriander | |

| LE16E1 | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Stenotrophomonas indicatrix | Lettuce | |

| LE42E1 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas geniculata | Lettuce | |

| MA16E2 | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Stenotrophomonas indicatrix | Farm Worker | |

| PI29E2 | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Stenotrophomonas indicatrix | Pepper | |

| PJ15E | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Stenotrophomonas indicatrix | Parsley | |

| TO26E | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Stenotrophomonas indicatrix | Tomato | |

| ZA29E2 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas geniculata | Carrot | |

| HSM1 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Abdominal cavity | Clinical |

| HSM2 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Respiratory tract | |

| HSM3 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Respiratory tract | |

| HSM4 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Respiratory tract | |

| HSM5 | Stenotrophomonas rhizophila | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Soft tissue | |

| HSM6 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas sp. | Soft tissue | |

| HSM7 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Respiratory | |

| HSM8 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Abdominal cavity | |

| HSM9 | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | Sputum | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).