Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

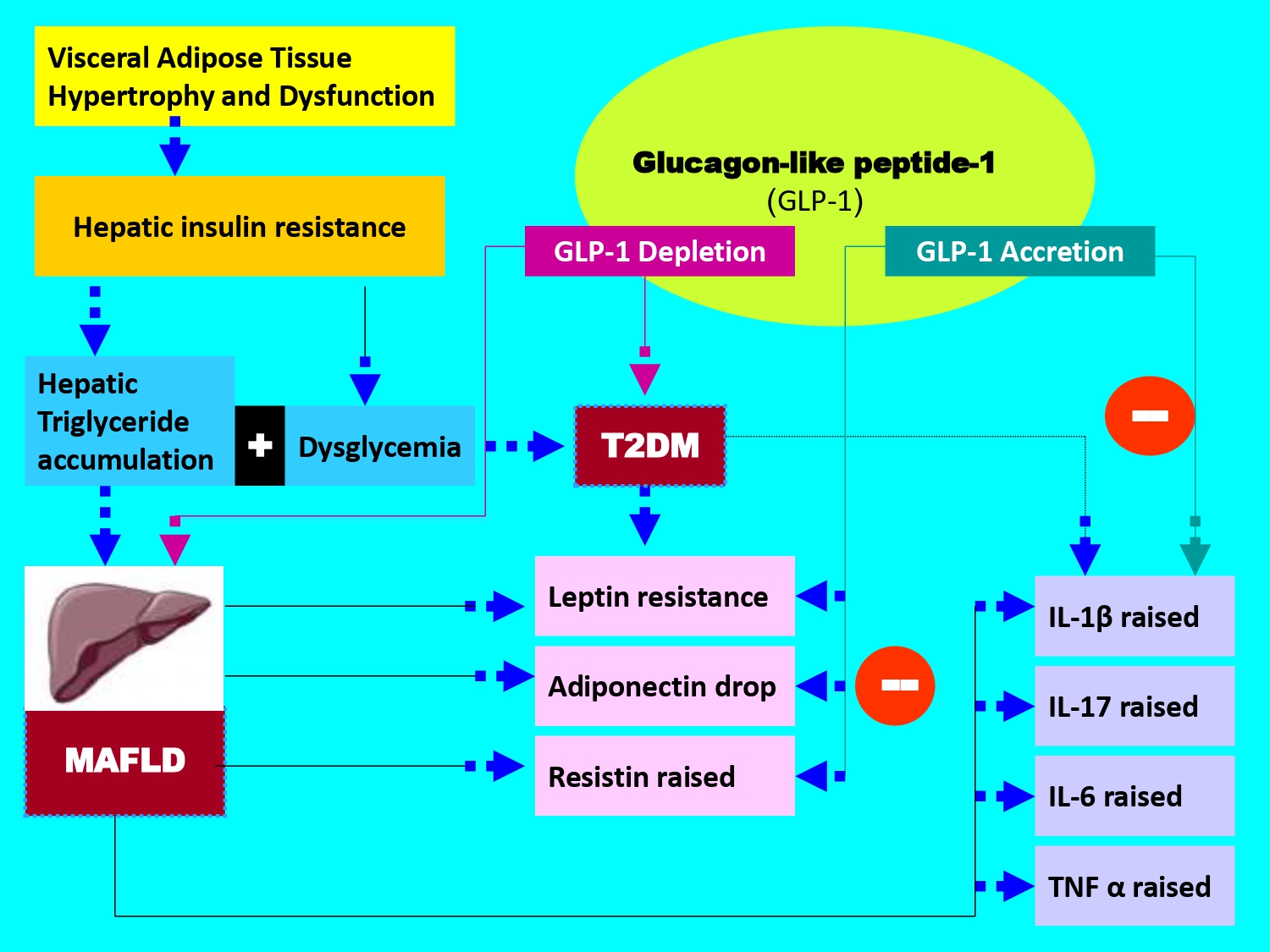

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Cohort Participant’s Characterization According Clinical Metabolic Syndrome

2.2. Plasma Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 (GLP-1) Profile

2.3. Plasma Adipokines Profile

2.3.1. Plasma Leptin Levels

2.3.2. Plasma Adiponectin Levels

2.3.3. Plasma Leptin/Adiponectin Ratio

2.3.4. Plasma Resistin Levels

2.4. Plasma Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines Profile

2.4.1. Plasma TNFα (Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha) Levels

2.4.2. Plasma IL-6 (Interleukin-6) Levels

2.4.3. Plasma IL-1 β (Interleukin-1β) Levels

2.4.4. Plasma IL-17 (Interleukin-17) Levels

3. Discussion

4. Patients and Methods

4.1. Informed Consent Statement and Ethical Considerations

4.2. Participants and Clinical Protocol Design

- -

- 100 Healthy participants, non-alcohol consumers and non-smokers (Group I)

- -

- 94 MAFLD participants without T2DM (Group III)

- -

- 222 MAFLD participants without T2DM (Group II)

- -

- 174 MAFLD participants with T2DM comorbidity (Group IV)

4.3. Radiological MAFLD Diagnosis

4.4. Histopathological MAFLD Diagnosis

4.5. Metabolic Syndrome (MetS) Screening

4.4. Plasma Samples and Biochemical Analysis

4.5. Plasma Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 (GLP-1) Assessment

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- He, KJ.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Gong, G.; Liu, X.; Guan, H. Global burden of type 2 diabetes mellitus from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2044: a systematic analysis across SDI levels for the global burden of disease study 2021. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024, 8, 1501690. [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; He, T.; Zhang, Y.; Long, Y.; Gao, C.; Xu, Y. Analysis of the global burden of diabetes and attributable risk factor in children and adolescents across 204 countries and regions from 1990 to 2021. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025, 8, 1587055. [CrossRef]

- Djeagou, A.; Gunukula, K.; Sermani, A.; Vaspari, SK. Emerging Perspectives in the Diagnosis and Management of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025, 24, e95288. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Sanyal, AJ.; George, J. International Consensus Panel. MAFLD: A consensus-driven proposed nomenclature for metabolic associated fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 1999-2014.e1. [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Huang, J.; Wang, M.; Kumar, R.; Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Y. Comparison of MAFLD and NAFLD diagnostic criteria in real world. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 2082-2089. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Yin, Y.; Wu, Q.; Chai, L.; Guo, Y.; Tong, Z.; Méndez-Sánchez, N.; Qi, X. Efficacy and safety of statins for nonalcoholic/metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2025, 4. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Scorletti, E.; Mosca, A.; Alisi, A.; Byrne, CD.; Targher, G. Complications, morbidity and mortality of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 2020, 111S, 154170. [CrossRef]

- Miller, DM.; McCauley, KF.; Dunham-Snary, KJ. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): Mechanisms, Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Advances. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2025, 8, e70132. [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, J.; Viggiano, TR.; McGill, DB.; Oh, BJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Mayo clinic experiences with a hitherto unnamed disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 1980,55, 434–8.

- Jaawan, S.; Krämer, A.; Masri, R.; Neesse, A.; Ellenrieder, V.; Amanzada, A.; Ströbel, P.; Bremmer, F.; Petzold, G. Diagnostic Utility of Liver Biopsy in Persistent Unexplained Liver Enzyme Elevation: A Retrospective Cohort Study. JGH Open 2025, 9, e70310. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, FM.; Zhao, HD.; Qi, ZM.; Chen, R.; Liao, ZX.; Xie, LF.; Zheng, C. The association between the hs-CRP/HDL-C ratio and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: The mediating role of insulin resistance in a cross-sectional study using NHANES 2017-2020. Medicine (Baltimore) 2025, 104, e46085. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, H.; Kawada, N. Japan Study Group of NAFLD. The role of insulin resistance and diabetes in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 3863. [CrossRef]

- Jonas, W.; Schürmann, A. Genetic and epigenetic factors determining NAFLD risk. Mol Metab. 2021,50, 101111. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Tian, R.; She, Z.; Cai, J.; Li, H. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020, 152, 116–41. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Vitetta, L. Gut microbiota metabolites in NAFLD pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 21, 5214. [CrossRef]

- Eslam, M.; Newsome, PN.; Sarin, SK.; Anstee, QM.; Targher, G.; Romero-Gomez, M.; Zelber-Sagi, S.; Wai-Sun Wong, V.; Dufour, JF.; Schattenberg, JM.; et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol, 2020, 73, 202–09. [CrossRef]

- Badmus, OO.; Hillhouse, SA.; Anderson, CD.; Hinds, TD.; Stec, DE. Molecular mechanisms of metabolic associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD): functional analysis of lipid metabolism pathways. Clin Sci (Lond). 2022, 136, 1347-1366. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Wu, D.; Mao, R.; Yao, Z.; Wu, Q.; Lv, W. Global burden of MAFLD, MAFLD related cirrhosis and MASH related liver cancer from 1990 to 2021. SciRep. 2025, 15, 7083. [CrossRef]

- Gofton, C.; Upendran, Y.; Zheng, MH.; George, J. MAFLD: How is it different from NAFLD? Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023, 29, S17-S31. [CrossRef]

- Chia, CW.; Egan, JM. Incretins in obesity and diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2020, 1461, 104-126.

- Elangovan, H.; Gunton, JE.; Zheng, MH.; Fan, JG.; Goh, GBB.; Gronbaek, H.; George, J. The promise of incretin-based pharmacotherapies for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int. 2025, 19, 337-348. [CrossRef]

- Barrett, KE. Endogenous and exogenous control of gastrointestinal epithelial function: building on the legacy of Bayliss and Starling. J Physiol. 2017, 595, 423-432. [CrossRef]

- Nauck, MA.; Meier, JJ. The incretin effect in healthy individuals and those with type 2 diabetes: physiology, pathophysiology, and response to therapeutic interventions. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 525-36. [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Kamalumpundi, V.; Codipilly, DC. GLP1 and GIP Receptor Agonists: Effects on the Gastrointestinal Tract and Management Strategies for Primary Care Physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2025, S0025-6196(25)00551-8. [CrossRef]

- Purcell, AR.; Zhen, XM.; Wong, J.; Glastras, SJ. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist treatment reduces body weight and improves glycaemic outcomes in patients with concurrent overweight/obesity and type 1 diabetes: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2026, 28, 296-305. [CrossRef]

- Drucker, DJ. Efficacy and Safety of GLP-1 Medicines for Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 1873-1888. [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, FS. New developments in GLP-1 agonist therapy for gestational diabetes: Systematic review on liraglutide, semaglutide, and exenatide from Clinical Trials.gov. Medicine (Baltimore) 2025, 104, e44917. [CrossRef]

- Zacharia, GS.; Gongati, SR.; Kharel, A.; Jacob, A. Semaglutide in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis: A Narrative Review. Cureus 2025, 17, e95632. [CrossRef]

- Kong, W.; Fang, B.; Xing, W. Efficacy and safety of liraglutide in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with or without type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Müller, TD.; Finan, B.; Bloom, SR.; D'Alessio, D.; Drucker, DJ.; Flatt, PR.; Fritsche, A.; Gribble, F.; Grill, HJ.; Habener, JF.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1). Mol Metab. 2019, 30, 72-130.

- Liu, QK. Mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications of GLP-1 and dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonists. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1431292. [CrossRef]

- Clark L. GLP-1 receptor agonists: A review of glycemic benefits and beyond. JAAPA 2024, 37, 1-4.

- van Ruiten, CC.; Ten Kulve, JS.; van Bloemendaal, L.; Nieuwdorp, M.; Veltman, DJ.; IJzerman, RG. Eating behavior modulates the sensitivity to the central effects of GLP-1 receptor agonist treatment: a secondary analysis of a randomized trial. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 137, 105667. [CrossRef]

- Huber, H.; Schieren, A.; Holst, JJ.; Simon, MC. Dietary impact on fasting and stimulated GLP-1 secretion in different metabolic conditions - a narrative review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024, 119, 599-627. [CrossRef]

- Smith, NK.; Hackett, TA.; Galli, A.; Flynn, CR. GLP-1: Molecular mechanisms and outcomes of a complex signaling system. Neurochem Int. 2019, 128, 94-105. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Liu, B. Global epidemiology of T2DM in patients with NAFLD or MAFLD: the real situation may be even more serious. BMC Med. 2024, 22, 476. [CrossRef]

- Ghosal, S.; Ghosal, A. Optimizing GLP-1RA Efficacy: A Meta-Analysis of Baseline Age and HbA1c as Predictors of MACE Reduction in T2DM. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2025, 18, 4347-4358. [CrossRef]

- Moon, JS.; Hong, JH.; Jung, YJ.; Ferrannini, E.; Nauck, MA.; Lim, S. SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists in metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2022, 33, 424-442. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; An, X.; Yang, C.; Sun, W.; Ji, H.; Lian, F. The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023,14, 1149239. [CrossRef]

- Pezzoli, A.; Abenavoli, L.; Scarcella, M.; Rasetti, C.; Svegliati Baroni, G.; Tack, J.; Scarpellini, E. The Management of Cardiometabolic Risk in MAFLD: Therapeutic Strategies to Modulate Deranged Metabolism and Cholesterol Levels. Medicine (Kaunas) 2025, 61, 387. [CrossRef]

- Rusu, E.; Jinga, M.; Cursaru, R.; Enache, G.; Costache, A.; Verde, I.; Nica, A.; Alionescu, A.; Rusu, F.; Radulian, G. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction and Hepatic Steatosis in New-Onset Diabetes. Diabetology 2025, 6, 70. [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Liang, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y. The effects of GLP-1 receptor agonists on visceral fat and liver ectopic fat in an adult population with or without diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0289616. [CrossRef]

- Rochoń, J.; Kalinowski, P.; Szymanek-Majchrzak, K.; Grąt, M. Role of gut-liver axis and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists in the treatment of metabolic dysfunction- associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 2964-2980. [CrossRef]

- Guney-Coskun, M.; Basaranoglu, M. Interplay of gut microbiota, glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists, and nutrition: New frontiers in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2024, 30, 4682-4688. [CrossRef]

- McLean, BA.; Wong, CK.; Campbell, JE.; Hodson, DJ.; Trapp, S.; Drucker, DJ. Revisiting the Complexity of GLP-1 Action from Sites of Synthesis to Receptor Activation. Endocr Rev. 2021, 42, 101-132. [CrossRef]

- Ranganath, LR. The entero-insular axis: implications for human metabolism. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2008, 46, 43-56. [CrossRef]

- Visschers, RG.; Luyer, MD.; Schaap, FG.; Olde Damink, SW.; Soeters, PB. The gut- liver axis. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013, 16, 576-81.

- Musso, G.; Gambino, R.; Pacini, G.; De Michieli, F.; Cassader, M. Prolonged saturated fat-induced, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide elevation is associated with adipokine imbalance and liver injury in non alcoholic steatohepatitis: dysregulated entero- adipocyte axis as a novel feature of fatty liver. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 89, 558-67.

- Khan, MT.; Zohair, M.; Khan, A.; Kashif, A.; Mumtaz, S.; Muskan, F. From Gut to Brain: The roles of intestinal microbiota, immune system, and hormones in intestinal physiology and gut-brain-axis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2025, 607, 112599. [CrossRef]

- Ronveaux, CC.; Tomé, D.; Raybould, HE. Glucagon-like peptide 1 interacts with ghrelin and leptin to regulate glucose metabolism and food intake through vagal afferent neuron signaling. J Nutr. 2015, 145, 672-80. [CrossRef]

- Francisco, V.; Sanz, MJ.; Real, JT.; Marques, P.; Capuozzo, M.; Ait Eldjoudi, D.; Gualillo, O. Adipokines in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Are We on the Road toward New Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets? Biology (Basel) 2022, 11, 1237. [CrossRef]

- Yaribeygi, H.; Maleki, M.; Atkin, SL.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Impact of Incretin-Based Therapies on Adipokines and Adiponectin. J Diabetes Res. 2021, 2021, 3331865. [CrossRef]

- Park, JS.; Kim, KS.; Choi, HJ. Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 and Hypothalamic Regulation of Satiation: Cognitive and Neural Insights from Human and Animal Studies. Diabetes Metab J. 2025, 49, 333-347. [CrossRef]

- Polex-Wolf, J.; Deibler, K.; Hogendorf, WFJ.; Bau, S.; Glendorf, T.; Stidsen, CE.;

- Tornøe, CW.; Tiantang, D.; Lundh, S.; Pyke C.; et al. Glp1r-Lepr coexpressing neurons modulate the suppression of food intake and body weight by a GLP-1/leptin dual agonist. Sci Transl Med. 2024, 16, eadk4908. [CrossRef]

- Simental-Mendía, LE.; Sánchez-García, A.; Linden-Torres, E.; Simental-Mendía, M. Impact of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists on adiponectin concentrations: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 4140- 4149. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ye, L.; Lee, KO.; Ma, J. Liraglutide treatment causes upregulation of adiponectin and downregulation of resistin in Chinese type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015, 110, 224-8. [CrossRef]

- Li, SL.; Wang, ZM.; Xu, C.; Che, FH.; Hu, XF.; Cao, R.; Xie, YN.; Qiu, Y.; Shi, HB.; Liu, B.; et al. Liraglutide Attenuates Hepatic Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury by Modulating Macrophage Polarization. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 869050. [CrossRef]

- Vachliotis, ID.; Polyzos, SA. The Intriguing Roles of Cytokines in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Narrative Review. Curr Obes Rep. 2025, 14, 65. [CrossRef]

- Coste, SC.; Orășan, OH.; Cozma, A.; Negrean, V.; Sitar-Tăut, AV.; Filip, GA.; Hangan, AC.; Lucaciu, RL.; Iancu, M.; Procopciuc, LM. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: The Associations between Inflammatory Markers, TLR4, and Cytokines IL-17A/F, and Their Connections to the Degree of Steatosis and the Risk of Fibrosis. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2144. [CrossRef]

- Dabbaghizadeh, A.; Dion, J.; Maali, Y.; Fouda, A.; Bédard, N.; Evaristo, G.; Hassan, GS.; Tchervenkov, J.; Shoukry, NH. Novel RORgammat inverse agonists limit IL-17- mediated liver inflammation and fibrosis. J Immunol. 2025, 214, 1321-1331. [CrossRef]

- Negrin, KA.; Roth Flach, RJ.; DiStefano, MT.; Matevossian, A.; Friedline, RH.; Jung, D.; Kim, JK., Czech, MP. IL-1 signaling in obesity-induced hepatic lipogenesis and steatosis. PLoS One 2014, 9, e107265. [CrossRef]

- Praktiknjo, M.; Schierwagen, R.; Monteiro, S.; Ortiz, C.; Uschner, FE.; Jansen, C.; Claria, J.; Trebicka, J. Hepatic inflammasome activation as origin of Interleukin-1α and Interleukin-1β in liver cirrhosis. Gut 2021, 70, 1799-1800. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wei, W.; Chen, M.; Qin, X.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Q.; Ying, Z. TNF Signaling Impacts Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Expression and Secretion. J Mol Endocrinol. 2018, 61, 153-161. [CrossRef]

- Lehrskov-Schmidt, L.; Lehrskov-Schmidt, L.; Nielsen, ST.; Holst, JJ.; Møller, K.; Solomon, TP. The effects of TNF-α on GLP-1-stimulated plasma glucose kinetics. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015, 100, E616-22. [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Buey, G.; Nú˜nez-Córdoba, JM.; Llavero-Valero, M.; Gargallo, J.; Salvador, J.; Escalada, J. Is HOMA-IR a potential screening test for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adults with type 2 diabetes ? Eur J Intern Med. 2017, 41, 74-8.

- Fattahi, MR.; Niknam, R.; Safarpour, A.; Sepehrimanesh, M.; Lotfi, M. The Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome In Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease; A Population-Based Study. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2016, 8, 131-7. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, T. J. Excess Triglycerides in Very Low-Density Lipoprotein (VLDL) Estimated from VLDL-Cholesterol could be a Useful Biomarker of Metabolic Dysfunction Associated Steatotic Liver Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Atheroscler Thromb. 2025, 32, 253-264. [CrossRef]

- Truong, XT.; Lee, DH. Hepatic Insulin Resistance and Steatosis in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: New Insights into Mechanisms and Clinical Implications. Diabetes Metab J. 2025, 49, 964-986. [CrossRef]

- Samuel, VT.; Petersen, MC.; Gassaway, BM.; Vatner, DF.; Rinehart, J.; Shulman, GI. Considering the Links Between Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Insulin Resistance: Revisiting the Role of Protein Kinase C epsilon. Hepatology 2019, 70, 2217-2220. [CrossRef]

- Lajeunesse-Trempe, F.; Dugas, S.; Maltais-Payette, I.; Tremblay, ÈJ. ; Piché, ME. ; Dimitriadis, GK. ; Lafortune, A.; Marceau, S.; Biertho, L.; Tchernof, A. Anthropometric Indices and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease in Males and Females Living With Severe Obesity. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025, 2025, 5545227. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, GC. Plasma Free Fatty Acid Concentration as a Modifiable Risk Factor for Metabolic Disease. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2590. [CrossRef]

- Oikawa, R.; Nakanishi, Y.; Fujimoto, K.; Wakasa, A.; Iwadare, M.; Iwao, HK.; Ishida, R.; Iwai, K. Elevated glucagon and postprandial hyperglycemia in fatty liver indicate early glucose intolerance in metabolic dysfunction associated steatotic liver disease. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 29916. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Zhang, H.; Mu, S.; Shi, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, K. Advances in Incretin-Based Therapies for MAFLD: Mechanisms and Clinical Evidence. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Jepsen, SL.; Albrechtsen, NJW.; Windeløv, JA.; Galsgaard, KD.; Hunt, JE.; Farb, TB.; Kissow, H.; Pedersen, J.; Deacon, CF.; Martin, RE.; et al. Antagonizing somatostatin receptor subtype 2 and 5 reduces blood glucose in a gut- and GLP-1R- dependent manner. JCI Insight. 2021, 6, e143228. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Su, Y.; Peng, Y.; Xu, F.; Yao, B.; Liang, H.; Lin, B.; Xu, W. GLP-1 receptor agonist protects glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic beta-cells against lipotoxicity via PPARdelta/UCP2 pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2025, 82, 375. 76. Liu, L.; Xia, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhang, Y. J. Efficacy of Incretin-Based Therapies in Patients With Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025, 40, 2659-2673. [CrossRef]

- Ghobar, F.; Tarhini, A.; Osman, Z.; Sbeih, S.; Ghayda, RA.; Matar, P.; Haddad, G.; Kanaan, A.; Eid, A.; Azar, S.; Ghadieh, HE.; Harb, F. GLP1 receptor agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors for the prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus onset: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025, 16, 1627909. [CrossRef]

- Conley, JM.; Jochim, A.; Evans-Molina, C.; Watts, VJ.; Ren, H. G Protein-Coupled Receptor 17 Inhibits Glucagon-like Peptide-1 Secretion via a Gi/o-Dependent Mechanism in Enteroendocrine Cells. Biomolecules 2024, 15, 9. [CrossRef]

- Wang, JL.; Xiao, Y.; Li, ML.; Chen, GL.; Cui, MH.; Liu, JL. Research Progress on Leptin in Metabolic Dysfunction-associated Fatty Liver Disease. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2025, 13, 964-975. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghurayr, NK.; Al-Mowalad, AM.; Omar, UM.; Ashi, HM.; Al-Shehri, SS.; AlShaikh, AA.; AlHarbi, SM.; Alsufiani, HM. Salivary Hormones Leptin, Ghrelin, Glucagon, and Glucagon-Like Peptide 1 and Their Relation to Sweet Taste Perception in Diabetic Patients. J Diabetes Res. 2023, 2023, 7559078. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Gao, Y.; Lieu, L.; Afrin, S.; Cao, J.; Michael, NJ.; Dong, Y.; Sun, J.; Guo, H.; Williams, KW. Direct and indirect effects of liraglutide on hypothalamic POMC and NPY/AgRP neurons - Implications for energy balance and glucose control. Mol Metab. 2019, 28,120-134. [CrossRef]

- Porniece Kumar, M.; Cremer, AL.; Klemm, P.; Steuernagel, L.; Sundaram, S.; Jais, A.; Hausen, AC.; Tao, J.; Secher, A.; Pedersen, TÅ., et al. Insulin signalling in tanycytes gates hypothalamic insulin uptake and regulation of AgRP neuron activity. Nat Metab. 2021, 3, 1662-1679. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, J.; Chávez-Castillo, M.; Rojas, J.; Ortega, A.; Nava, M.; Pérez, J.; Rojas, M.; Espinoza, C.; Chacin, M.; Herazo, Y.; et al. Is "Leptin Resistance" Another Key Resistance to Manage Type 2 Diabetes?. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2020,16, 733-749.

- Contreras, PH.; Falhammar, H. CRF1 and ACTH inhibitors are a promising approach to treat obesity and leptin and insulin resistance. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025, 16, 1647028. [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, MK.; Badran, DI.; Keshawy, MM.; Makary, S.; Abdo, M. Alternate-day fat diet and exenatide modulate the brain leptin JAK2/STAT3/SOCS3 pathway in a fat diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance mouse model. Arch Med Sci. 2023, 19, 1508-1519. [CrossRef]

- Al Refaie, A.; Baldassini, L.; Mondillo, C.; Ceccarelli, E.; Tarquini, R.; Gennari, L.; Gonnelli, S.; Caffarelli, C. Adiponectin may play a crucial role in the metabolic effects of GLP-1RAs treatment in patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: a preliminary longitudinal study. Endocrine 2025, 87, 951-958. [CrossRef]

- Prakash, S.; Rai, U.; Kosuru, R.; Tiwari, V.; Singh, S. Amelioration of diet-induced metabolic syndrome and fatty liver with sitagliptin via regulation of adipose tissue inflammation and hepatic Adiponectin/AMPK levels in mice. Biochimie 2020, 168, 198-209. [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Xu, S.; Chen, Y.; Luo, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Q. Adiponectin attenuates atherosclerosis via macrophage polarization-mediated T Cell exhaustion by modulating the NF-kappaB p65/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Tissue Cell. 2025, 98,103150. [CrossRef]

- Al-Dallal, R.; Thomas, K.; Lee, M.; Chaudhri, A.; Davis, E.; Vaidya, P.; Lee, M.; McCormick, JB.; Fisher-Hoch, SP.; Gutierrez, AD. The Association of Resistin with Metabolic Health and Obesity in a Mexican-American Population. Int J Mol Sci. 2025, 26, 4443. [CrossRef]

- Risum, K.; Olarescu, NC.; Godang, K.; Marstein, HS.; Bollerslev, J.; Sanner, H. Visceral adipose tissue is associated with interleukin 6 and resistin in juvenile idiopathic arthritis - a case-control study. Rheumatol Int. 2025, 45, 63. [CrossRef]

- Qi, MM.; Guan, XQ.; Zhu, LR.; Wang, LJ.; Liu, L.; Yang, YP. The effect of resistin on nuclear factor-kB and tumor necrosis factor-alpha expression in hepatic steatosis. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2012, 20, 40-4. [CrossRef]

- Tabaeian, SP.; Mahmoudi, T.; Rezamand, G.; Nobakht, H.; Dabiri, R.; Farahani, H.; Asadi, A.; Zali, MR. Resistin gene polymorphism and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease risk. Arq Gastroenterol. 2022, 59, 483-487. [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ye, L.; Lee, KO.; Ma. J. Liraglutide treatment causes upregulation of adiponectin and downregulation of resistin in Chinese type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015, 110, 224-8. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yin, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, Y. The Role of IL-6 in Fibrotic Diseases: Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms. Int J Biol Sci. 2022, 18, 5405-5414. [CrossRef]

- Kagan, P.; Sultan, M.; Tachlytski, I.; Safran, M.; Ben-Ari, Z. Both MAPK and STAT3 signal transduction pathways are necessary for IL-6-dependent hepatic stellate cells activation. PloS One 2017, 12, e0176173. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zheng, W.; Kong, W.; Liao, Y.;, Zhang, J.; Wang, M.; Zeng, T. The effect of GLP-1 receptor agonists on circulating inflammatory markers in type 2 diabetes patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2025, 27, 3607-3626. [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Shen, B. Immunomodulatory effects of anti-diabetic therapies: Cytokine and chemokine modulation by metformin, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (2013-2025). Eur J Med Chem. 2025, 299, 118065. [CrossRef]

- Daousi, C.; Pinkney, JH.; Cleator, J.; Wilding, JP.; Ranganath, LR. Acute peripheral administration of synthetic human GLP-1 (7–36 amide) decreases circulating IL-6 in obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A potential role for GLP-1 in modulation of the diabetic pro-inflammatory state? Regulatory Peptides 2013, 183, 54–61. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, ZM.; Golabi, P.; Price, JK.; Owrangi, S.; Gundu-Rao, N.; Satchi, R.; Paik, JM. The Global Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024, 22, 1999-2010.e8. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Niu, Q.; Tao, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, Z.; Dong, H. The role of the interleukin family in liver fibrosis. Front Immunol. 2025, 16, 1497095. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, H.; Chen, R.; Chen, W.; Qi, H.; Gao, W. Dioscin Attenuates Interleukin 1β (IL-1β)-Induced Catabolism and Apoptosis via Modulating the Toll- Like Receptor 4 (TLR4)/Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-κB) Signaling in Human Nucleus Pulposus Cells. Med Sci Monit. 2020, 26, e923386. [CrossRef]

- Ćurčić, IB.; Kizivat, T.; Petrović, A.; Smolić, R.; Tabll, A.; Wu, GY.; Smolić, M. Therapeutic Perspectives of IL1 Family Members in Liver Diseases: An Update. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2022, 10, 1186-1193. [CrossRef]

- Olivier, A.; Augustin, S.; Benlloch, S.; Ampuero, J.; Suárez-Pérez, JA.; Armesto, S.; Vilarrasa, E.; Belinchón-Romero, I.; Herranz, P.; Crespo, J.; et al. The Essential Role of IL-17 as the Pathogenetic Link between Psoriasis and Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Life (Basel) 2023, 13, 419. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. The role of transforming growth factor β in T helper 17 differentiation. Immunology 2018, 155, 24-35. [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.; Wang, K.; Aoyama, T.; Grivennikov, SI.; Paik, Y.; Scholten, D.; Cong, M.; Iwaisako, K.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; et al. Interleukin-17 signaling in inflammatory, Kupffer cells, and hepatic stellate cells exacerbates liver fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology 2012, 143,765–776.e3. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, SF.; Pusapati, S.; Anwar, MS.; Lohana, D.; Kumar, P.; Nandula, SA.; Nawaz, FK.; Tracey, K.; Yang, H.; LeRoith, D.; et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1: a multi-faceted anti-inflammatory agent. Front Immunol. 2023, 14, 1148209. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Moneim, A.; Bakery, HH.; Allam, G. The potential pathogenic role of IL- 17/Th17 cells in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018,101, 287–92. [CrossRef]

- Bozzetto, L.; Annuzzi, G.; Ragucci, M.; Di Donato, O.; Della Pepa, G.; Della Corte, G.; Griffo, E.; Anniballi, G.; Giacco, A.; Mancini, M.; et al. Insulin resistance, postprandial GLP-1 and adaptive immunity are the main predictors of NAFLD in a homogeneous population at high cardiovascular risk. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016, 26, 623-629. [CrossRef]

- Fouad, Y.; Alboraie, M.; Shiha, G. Epidemiology and diagnosis of metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int. 2024, 18(Suppl 2), 827-833. [CrossRef]

- Chan, WK.; Wong, VW.; Adams, LA.; Nguyen, MH. MAFLD in adults: non- invasive tests for diagnosis and monitoring of MAFLD. Hepatol Int. 2024, 18(Suppl 2), 909-921. [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Lee, HW.; Yip, TC.; Tsochatzis, E.; Petta, S.; Bugianesi, E.; Yoneda, M.; Zheng, MH.; Hagström, H.; Boursier, J.; et al. Vibration-Controlled Transient Elastography Scores to Predict Liver-Related Events in Steatotic Liver Disease. JAMA 2024, 331,1287-1297. [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, AB.; Mehta, KJ. Liver biopsy for assessment of chronic liver diseases: a synopsis. Clin Exp Med. 2023, 23, 273-285. [CrossRef]

- Expert panel on detection evaluation treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults. Executive summary of the third report of the National cholesterol education program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA 2001, 285, 2486-97.

- Bonora, E.; Targher, G.; Alberiche, M.; Bonadonna, R.C.; Saggiani, F.; Zenere, M.B.; Monauni, T.; Muggeo, M. Homeostasis model assessment closely mirrors the glucose clamp technique in the assessment of insulin sensitivity: Studies in subjects with various degrees of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 2000, 23, 57–63. [CrossRef]

- Deurenberg, P.; Westrate, J.A.; Seidell, J.C. Body mass index as a measure of body fatness: Age- and sex-specific prediction formulas. Br. J. Nutr. 1991, 65, 105–111. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, E.; Mee, F.; Atkins, N.; Thomas, M. Evaluation of three devices for self measurement of blood pressure according to the revised British Hypertension Society Protocol: The Omron HEM-705CP, Philips HP5332, and Nissei DS-175. Blood Press. Monit. 1996, 1, 55-61.

| P/G |

Group I (N=100) |

Group II (N=94) |

Group III (N=222) |

Group IV (N=174) |

| Δ GLP-1 (pmole/L) | 11.7 ± 1.71(Fs) | 9.50 ± 2.52(Fs)* | 8.80 ± 1.52(Fs)*** | 6.62 ± 1.6(Fs)*** |

| 34.5 ± 3.81(PP) | 20.7 ± 4.18(PP)* | 14.6 ± 2.25(PP)*** | 10.9 ± 2.70(PP) *** | |

| Glycemia (mmol/L) | 4.67 ± 0.39 | 6.27 ± 0.09** | 8.71 ± 0.33*** | 9.21 ± 0.42*** |

| HbA1C (%) | 5.53 ± 0.80 | 5.62 ± 0.70*** | 6.17 ± 0.18*** | 6.39 ± 0.11*** |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 37 ± 5.35 | 38 ± 4.05*** | 44.1 ± 3.80*** | 46.1 ± 1.46*** |

| Insulinemia (pmol/L) | 63 ± 3.47 | 165 ± 5.62*** | 299 ± 21*** | 510 ± 38*** |

| Homa-IR Index | 1.98 ± 0.10 | 6.65 ± 0.26*** | 17.06 ± 1.54*** | 30.6 ± 2.48*** |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0.72 ± 0.04 | 1.50 ± 0.19*** | 1.76 ± 0.10*** | 2.22 ± 0.14*** |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.98 ± 0.22 | 5.05 ± 0.40*** | 4.89 ± 0.57*** | 5.54 ± 0.93*** |

| HDL- Chol (mmol/L) | 1.24 ± 0.04(M) 1.57 ± 0.08 (W) |

1.10 ± 0.05(M) 1.23 ± 0.05 (W) |

1.05 ± 0.03 (M) 1.14 ± 0.06 (W) |

1.00 ± 0.04(M) 1.06 ± 0.02(W) |

| LDL- Chol (mmol/L) | 2.49 ± 0.02 | 3.21 ± 0.15 | 3.49 ± 0.12*** | 4.29 ± 0.06*** |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 125 ± 15 | 126 ± 16 | 129 ± 13 | 135 ± 17 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 80.3 ± 3.81 | 79.8 ± 5.7 | 80.7 ± 6.3 | 81.3 ± 7.4 |

| Total bilirubin (µmol/L) | 9.91 ± 0.68 | 11.4 ± 0.17 | 11.2 ± 0.68 | 12.1 ± 0.34 |

| AST (IU/l) | 21.7 ± 1.20 | 30.6 ± 2.61 | 26.4 ± 1.82 | 41.0 ± 4.68*** |

| ALT (IU/l) | 26.8 ± 1.09 | 76.3 ± 5.90*** | 29.1 ± 1.58 | 82.1 ± 5.98*** |

| AST/ALT Ratio | 0.81 ± 0.06 | 0.66 ± 0.04*** | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.63 ± 0.08*** |

| GGT (IU/l) | 21.9 ± 2.20 | 70.4 ± 4.42*** | 52.4 ± 3.66*** | 83.7 ± 5.24*** |

| AP (UI/L) | 79.3 ± 3.37 | 91.4 ± 5.11 | 86.5 ± 4.64 | 98.0 ± 6.92*** |

| Iron (g/L) | 1.28 ± 0.05 | 1.33 ± 0.02 | 1.55 ± 0.07* | 1.95 ± 0.07* |

| Ferritin (pmol/L) | 147 ± 11 | 204 ± 3*** | 172 ± 5 | 309 ± 4*** |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 7.70 ± 0.6*** | 5.61 ± 0.1** | 9.44 ± 0.8*** |

| NEFA (µmol/L) | 290 ± 36 | 510 ± 51** | 689 ± 123*** | 897 ± 78*** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).