Introduction

The agriculture industry is a cornerstone of global economies, serving as a primary source of food, raw materials, and employment for billions of people worldwide. It plays a pivotal role in ensuring food security, reducing poverty, and driving economic growth, particularly in developing nations where a significant portion of the population relies on farming for their livelihoods (Syahputri et al. 2024). Beyond its direct contributions, agriculture supports related industries such as food processing, manufacturing, and trade, creating a ripple effect that strengthens national economies. In many countries, agricultural exports are a major source of foreign exchange earnings, further underscoring its importance to economic stability and growth. However, the agriculture industry faces numerous challenges, including climate change, resource depletion, and the need to feed a growing global population, making sustainable practices essential for its future (Dönmez et al. 2024). Sustainability in agriculture involves adopting practices that balance productivity with environmental stewardship, economic viability, and social equity. One key approach is the use of precision agriculture, which leverages technologies like GPS, drones, and sensors to optimize resource use, reduce waste, and increase yields (Getahun et al. 2024). Another sustainable practice is crop rotation and diversification, which improve soil health, reduce pest outbreaks, and enhance resilience to climate change. Organic farming, which avoids synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, is also gaining traction as a way to reduce environmental impact and meet consumer demand for healthier food options (Panday et al. 2024). Additionally, water management strategies, such as drip irrigation and rainwater harvesting, are critical for conserving water resources in water-scarce regions. These approaches not only enhance agricultural productivity but also contribute to long-term environmental sustainability.

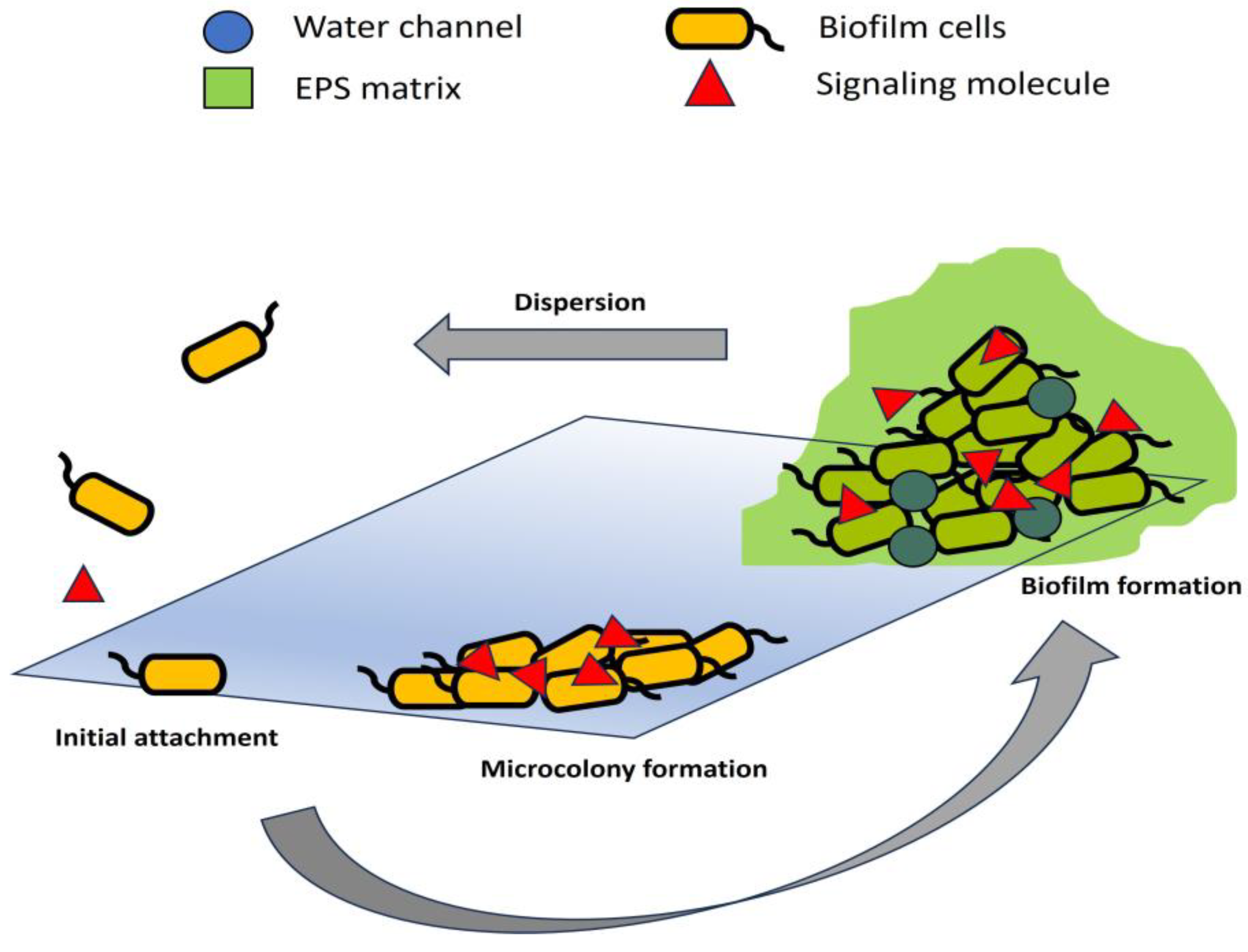

Biofilm management is an emerging sustainable practice that addresses the challenges posed by biofilm-forming pathogens in agriculture. Biofilms, which are structured communities of microorganisms encased in a protective extracellular matrix, can cause significant crop losses by promoting plant diseases and contaminating irrigation systems (Carezzano et al., 2023; Kanarek et al. 2024). Traditional methods of controlling these pathogens, such as chemical pesticides, are often ineffective against biofilms and can harm the environment. Sustainable biofilm management practices include the use of biological control agents, such as beneficial microbes that outcompete or inhibit pathogenic biofilms (Ghiasian et al. 2020). Other strategies include using enzymes, phages, and antimicrobial molecules like quorum sensing inhibitors to disrupt biofilms (Sharma & Karnwal, 2020). By integrating these innovative strategies, farmers can reduce crop losses, improve yields, and promote sustainable agricultural practices.

Biofilm-forming pathogens pose significant challenges to crop health, soil quality, and water systems. These biofilms protect pathogens from environmental stresses, such as drought, UV radiation, and chemical treatments, making them highly resilient and difficult to eradicate. The persistence of biofilm-forming pathogens in agricultural systems can lead to reduced crop yields, increased use of chemical pesticides, and economic losses (Rather et al. 2021). Understanding the role of biofilms in agricultural sustainability is critical for developing effective strategies to mitigate their impact. This review explores the mechanisms of biofilm formation, their effects on agricultural systems, and innovative approaches to manage biofilm-associated phytopathogens.

Type III Secretion System

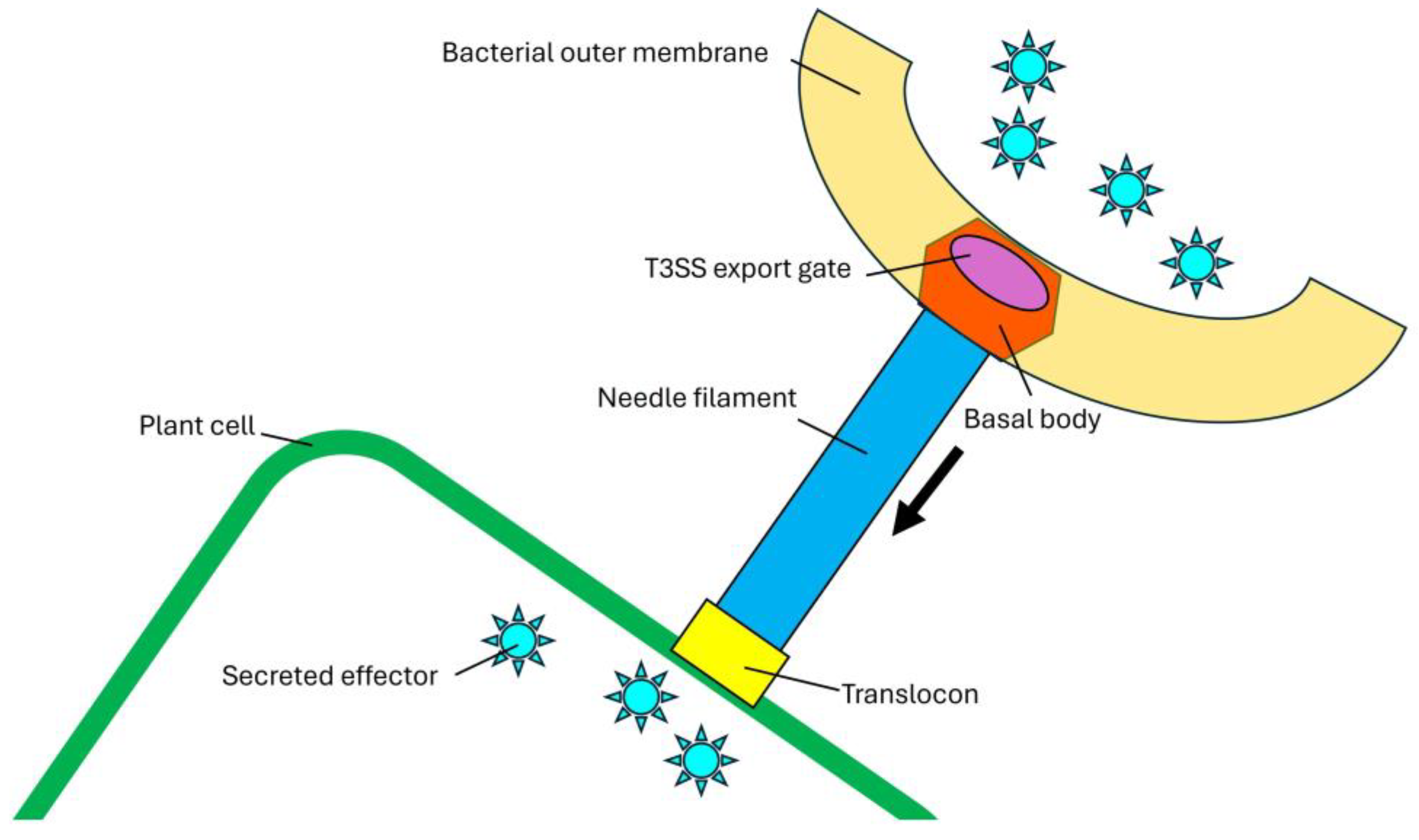

The Type III Secretion System (T3SS) is a sophisticated molecular syringe-like apparatus employed by many Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria to inject effector proteins directly into the cytoplasm of host cells (

Figure 2). T3SS acts as a molecular syringe, injecting effector proteins into host cells to manipulate cellular processes and enhance bacterial survival (Horna & Ruiz, 2021). The T3SS needle complex consists of a basal body spanning bacterial membranes, connected to a needle-like structure protruding from the bacterial surface (Miletic et al., 2019). The basal body is composed of oligomerized membrane-embedded proteins forming concentric rings (Bergeron et al., 2013). Upon host cell contact, a translocon forms, creating a pore for effector protein translocation (Chatterjee et al., 2013). advancements in cryo-EM and cryo-ET have provided near-atomic resolution structures of isolated complexes and the entire T3SS in its native cellular environment (Hu et al., 2019). The T3SS is often upregulated, enabling bacteria to efficiently deliver effector proteins into plant cells. These effector proteins manipulate host cellular processes, such as suppressing plant immune responses, altering host signaling pathways, and inducing nutrient leakage from plant tissues (De Jonge et al. 2011). XopB, a T3SS effector from

Xanthomonas campestris, inhibits reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and salicylic acid (SA) accumulation, leading to reduced expression of defense-related genes (Priller et al., 2016). By subverting these defenses, the bacteria can establish a successful infection and proliferate within the host. In Xanthomonas sp, T3SS contributes to biofilm formation by modulating metabolic processes, energy generation, and exopolysaccharide production (Zimaro et al., 2014).

Effector proteins secreted via the T3SS can modulate the expression of genes involved in biofilm formation, such as those encoding extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that form the biofilm matrix (Zimaro et al., 2014). This matrix not only protects the bacteria from environmental stresses but also facilitates the localized delivery of effectors to plant cells at the infection site (Carezzano et al., 2023. As a result, the biofilm becomes a reservoir of pathogenic bacteria that continuously release effectors, exacerbating plant damages over time. Zimaro et al. (2014) compared the capacity of biofilm formation between different T3SS mutants of phytopathogen Xanthomonas citri. They observed that the T3SS was necessary for biofilm formation. The lack of the T3SS caused changes in the expression of proteins involved in metabolic processes, energy generation, exopolysaccharide (EPS) production and bacterial motility as well as outer membrane proteins. Hu et al. (2022) evaluated the effects of salicylic acid (SA), p-hydroxybenzoic acid (PHBA), cinnamyl alcohol (CA), p-coumaric acid (PCA), and hydrocinnamic acid (HA) on the T3SS in Dickeya zeae, a plant soft-rot pathogen. They showed that all those compounds downregulated the expression of T3SS and significantly lessened the soft-rot symptoms on potato, taro, rice, and banana seedlings. Kan et al. (2023) investigated how plant cells respond to T3SS and T6SS in Acidovorax citrulli and whether there is any cross talk between them during infection. They demonstrated that the T3SS-mediated differentially expressed genes were enriched in the pathways of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, plant-pathogen interaction, MAPK signaling pathway, and glutathione metabolism, while the T6SS uniquely affected genes were related to photosynthesis. The T3SS-mediated virulence was independent of the T6SS, and the inactivation of the T3SS did not affect the T6SS-mediated competition against a diverse set of bacterial pathogens that commonly contaminate edible plants or directly infect plants. Collectively, the T3SS is a critical, multi-functional virulence determinant, not only for direct effector delivery but also for establishing protective biofilms; its targeted inhibition presents a promising strategy for disease control.

Impact of Biofilm-Forming Phytopathogens on Crop Health

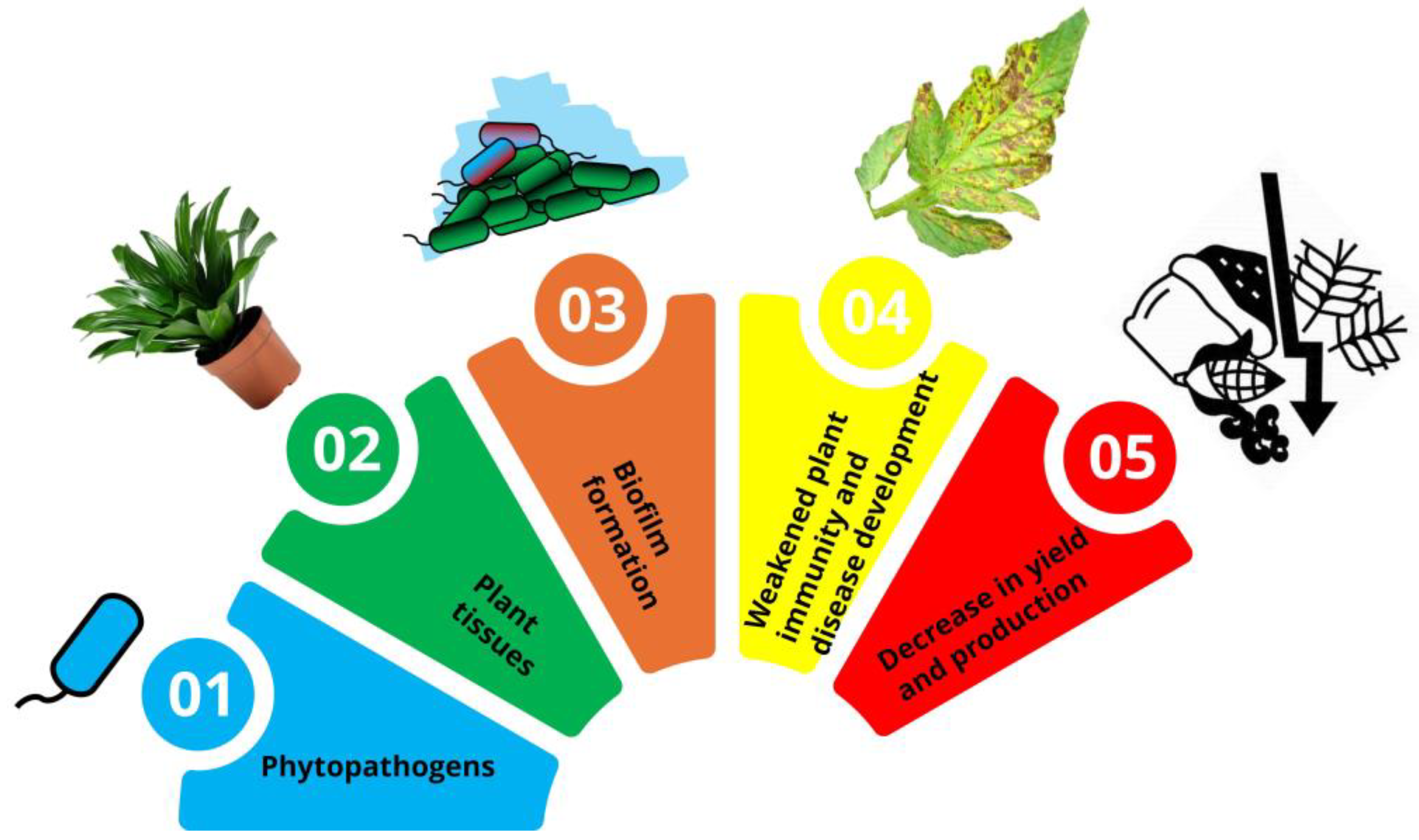

Biofilm formation by phytopathogenic bacteria and fungi poses significant challenges to crop health and food security (

Figure 3). These microbial communities offer protection against environmental stresses and enhance colonization of plant tissues, leading to various disease symptoms (Carezzano et al., 2023). While biofilms are often associated with negative impacts, recent research has explored their potential benefits through plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB), which can improve crop stress tolerance and yield under harsh conditions (Li et al., 2023). However, biofilms formed by enteric pathogens like Salmonella enterica and Escherichia coli on plants can persist and resist disinfection, causing foodborne outbreaks (Yaron & Römling, 2014). The impact of phytopathogenic biofilms on agriculture cannot be understated. Formed on leaves (mesophyll, parenchyma), in the rhizosphere, and/or in vascular bundles, they reduce crop yield and quality and affect the safety of agricultural products intended for human consumption and animal feeding (Castiblanco & Sundin 2016). In addition, the EPSs secreted by phytopathogenic bacteria interfere with the proper functioning of plant tissues and organs.

The causative agent of fire blight disease, Erwinia amylovora, colonizes rosaceous plants by regulating their immune responses and physiology through a T3SS. E. amylovora induces T3SS-dependent cell death and defense mechanisms in Arabidopsis thaliana, including callose deposition, salicylic acid pathway activation, and reactive oxygen species accumulation (Degrave et al. 2008). In addition, it produces two EPS, amylovoran and levan, to form a biofilm within the vascular tissue. Amylovoran is essential for biofilm formation and pathogenicity, while levan contributes to both processes (Koczan et al., 2009). The synthesis of these polymers and that of cellulose, another component of the biofilm matrix, are positively regulated by an increase in intracellular c-di-GMP.

Xanthomonas campestris pv. Campestris (Xcc), the causal agent of black rot in crucifers, colonizes the xylem after gaining access to the plant through wounds or hydathodes (Cerutti et al. 2017). It synthesizes xanthan gum to form biofilm and degrading exoenzymes that promote virulence. Its aggregation is regulated by c-di-GMP and a two-component RpfC/RpfG system, in which RpfC is the histidine kinase sensor and RpfG is the response-regulating protein (Slater et al. 2000). Plant defense mechanisms, including post-invasive immunity, attempt to limit bacterial growth but are suppressed by Xcc’s T3SS (Cerutti et al., 2017).

Sweet corn and maize may suffer from Stewart’s wilt, a disease transmitted by the corn flea beetle and caused by P. stewartii subsp. stewartii. Through the intervention of an hrp-encoded Hrp T3SS and the effector WtsE, the bacterium infects the apoplast and the xylem (Frederick et al. 2001). There, its population density grows, and dense biofilms are formed, encapsulated in a slime exopolysaccharide called stewartan (Carlier et al. 2009). The water flow is blocked, and symptoms appear, ranging from chlorotic lesions on leaves that eventually become necrotic and delay growth to rapid wilting and death in more susceptible plants. Stewartan also facilitates the pathogen’s movement through the vessels or intercellular spaces, which increases virulence.

Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis (Cmm), a Gram-positive bacterial pathogen, is the causal agent of bacterial wilt and canker in tomatoes (Sen et al. 2015). Dehydration and death ensue when C. michiganensis multiplies and produces EPS and glycoproteins to create large biofilms that decrease the water flow. Unlike gram-negative pathogens, Cmm lacks a T3SS for effector translocation. Instead, its virulence factors are encoded on plasmids and a chromosomal pathogenicity island (Chalupowicz et al., 2012).

Phytopathogenic Biofilms in Soil and Water Systems

Pathogenic biofilms in soil and water systems represent a significant and often overlooked threat to agricultural industries. In soil, pathogenic biofilms can form on plant roots, organic matter, or soil particles, creating reservoirs of infection that are difficult to eradicate (Rinaudi & Giordano 2010). Similarly, in water systems, such as irrigation channels or storage tanks, biofilms can colonize surfaces and contaminate water supplies (Flemming et al. 2002). The resilience of biofilms, which are highly resistant to environmental stresses and chemical treatments, allows these pathogens to persist and spread, leading to recurrent infections and significant crop losses. The presence of pathogenic biofilms in soil systems can severely impact plant health and agricultural productivity. For example, Fusarium species, which form biofilms in soil, are responsible for root rot and other diseases that affect a wide range of crops (Foroud et al. 2014). These biofilms protect pathogens from host plant defenses and chemical treatments, making infections difficult to control. Furthermore, biofilms can alter soil microbial communities, disrupting beneficial interactions and reducing soil fertility.

In water systems, phytopathogenic biofilms pose an equally serious threat to agriculture. Irrigation water contaminated with biofilm-forming pathogens, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa or Xanthomonas species, can serve as a vector for spreading diseases across large agricultural areas. Biofilms in irrigation equipment, such as pipes and sprinklers, can release planktonic cells that infect crops during watering (Yao & Habimana 2014). This not only leads to direct crop losses but also necessitates costly cleaning and disinfection procedures to prevent further contamination. Additionally, biofilms in water systems can accumulate rapidly, leading to clogged irrigation equipment, reducing efficiency and increasing maintenance costs (Yan et al. 2010). The persistence of phytopathogenic biofilms in water systems complicates efforts to maintain water quality, which is critical for sustainable agriculture. The presence of biofilms in soil and water systems can undermine consumer confidence in food safety, particularly for fresh produce that is consumed raw. Outbreaks of foodborne illnesses linked to biofilm-contaminated water or soil can result in costly recalls, legal liabilities, and damage to brand reputation.

Challenges in Managing Biofilm-Forming Phytopathogens

Managing biofilm-forming pathogens in the agriculture industry presents a complex and multifaceted challenge due to the unique characteristics of biofilms and the diverse environments in which they thrive. Biofilms are structured communities of microorganisms encased in a self-produced EPS matrix, which provides protection against environmental stresses, chemical treatments, and host immune responses (Zimaro et al., 2014). This resilience makes biofilm-forming pathogens particularly difficult to control in agricultural settings, where they can colonize soil, water systems, and plant surfaces. The persistence of these pathogens leads to recurrent infections, reduced crop yields, and significant economic losses, necessitating innovative and sustainable management strategies.

One of the primary challenges in managing biofilm-forming pathogens is their resistance to conventional control methods. Chemical pesticides and antibiotics, which are commonly used to combat microbial infections, often fail to penetrate the EPS matrix effectively (Pinto et al. 2020). This allows biofilm-embedded pathogens to survive and regrow even after treatment. Moreover, the overuse of these chemicals can lead to the development of resistant strains, further complicating disease management. In addition to resistance, chemical treatments can have detrimental effects on non-target organisms, soil health, and water quality, undermining the sustainability of agricultural practices. These limitations highlight the need for alternative approaches that specifically target biofilm vulnerabilities without causing collateral damage to the environment.

Another significant challenge is the complexity of biofilm ecosystems in agricultural environments. Biofilms are not homogeneous; they often consist of diverse microbial communities that interact in ways that enhance their survival and virulence. For example, some bacteria within a biofilm may produce enzymes that degrade plant cell walls, while others may protect the community from host defenses or chemical treatments (Wei et al. 2009). This synergy makes it difficult to develop one-size-fits-all solutions for biofilm management. Additionally, biofilms can form on a wide range of surfaces, including plant roots, irrigation equipment, and soil particles, requiring tailored strategies for each context. Understanding the ecological dynamics of biofilms and their interactions with crops and soil microbiota is essential for developing effective interventions.

Economic and logistical constraints also pose challenges to managing biofilm-forming pathogens in agriculture. Developing and implementing innovative solutions, such as biological control agents and nanotechnology-based treatments, often require significant investment in research, infrastructure, and education (Acharya & Pal 2020). Smallholder farmers, who constitute a large proportion of the agricultural workforce in developing countries, may lack the resources to adopt these advanced technologies. Due to high initial production investments, industry experts are also reluctant to invest significantly in these innovation solutions. Balancing the costs and benefits of these interventions is critical for ensuring their widespread adoption and long-term sustainability.

Innovative Strategies for Controlling Biofilm-Forming Phytopathogens

Controlling biofilm-forming pathogens in the agriculture industry requires innovative strategies that address the unique challenges posed by these resilient microbial communities. Traditional methods, such as chemical pesticides and antibiotics, are often ineffective against biofilms due to their protective extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix and the risk of promoting resistance. As a result, researchers and industry stakeholders are exploring alternative approaches that leverage advances in biotechnology, nanotechnology, and ecological principles to disrupt biofilms and prevent their formation. These innovative strategies not only enhance the efficacy of pathogen control but also align with the growing demand for sustainable and environmentally friendly agricultural practices.

One promising approach is the use of biological control agents, which involve the application of beneficial microorganisms to outcompete or inhibit biofilm-forming pathogens. For example, certain strains of Bacillus and Pseudomonas bacteria produce antimicrobial compounds that can disrupt biofilm formation or degrade the EPS matrix. Exopolysaccharides secreted by Bacillus velezensis strains have shown significant anti-biofilm activity against Staphylococcus aureus, reducing biofilm formation by up to 83% (Sabino et al., 2023). Small molecules that repress pel gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa have demonstrated antibiofilm and antivirulence effects, enhancing antibiotic efficacy (Van Tilburg Bernardes et al., 2017). These biological control agents offer a sustainable alternative to chemical treatments, as they are often specific to target pathogens and have minimal impact on non-target organisms and the environment. Additionally, they can be integrated into existing agricultural practices, such as seed treatments or soil amendments, to provide long-term protection against biofilm-associated diseases.

Another innovative strategy is the use of quorum sensing inhibitors (QSIs), which disrupt the communication systems that biofilm-forming pathogens use to coordinate their behavior. Quorum sensing is a process by which bacteria produce and detect signaling molecules to regulate biofilm formation, virulence, and other group behaviors. By blocking these signals, QSIs can prevent biofilm formation and reduce the virulence of pathogens without killing them, thereby minimizing the risk of resistance development. Yang et al. (2024) evaluated the triple-action (broad-spectrum antibacterial, anti-biofilm, and anti-QS sensing activities) of melittin. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics analysis showed that melittin interacts with LasR receptors through hydrogen bonds, confirming its potential as antibacterial agent and QSI.

Nanotechnology is also emerging as a powerful tool for controlling biofilm-forming pathogens in agriculture. Nanoparticles, such as those made from silver, zinc oxide, or chitosan, can penetrate the EPS matrix and deliver antimicrobial agents directly to biofilm-embedded pathogens (Yakup et al. 2024; Yusri et al. 2024). These nanoparticles can be engineered to release their payload in response to specific environmental triggers, such as pH or temperature changes, ensuring targeted and efficient delivery. Additionally, nanomaterials can be incorporated into packaging, coatings, or irrigation systems to prevent biofilm formation and contamination. Hsu et al. (2020) demonstrated excellent antibiofilm activity of PEDOT/PSS and PEDOT/GO nanohybrid coatings. Only 0.1% of bacteria can be adhered on the surface due to the lower surface roughness and negative charge surface by PEDOT/PSS and PEDOT/GO modification.

Edible antibiofilm coatings represent another innovative approach to controlling biofilm-forming pathogens (

Figure 4). These coatings can be applied to seeds, plant surfaces, or irrigation equipment to release antimicrobial agents in a controlled manner, preventing biofilm formation and pathogen colonization. Valliammai et al. (2021) developed a polymeric antibiofilm coating using citral (CIT) and thymol (THY) as active components. This coating was applied to a titanium surface using the spin coating method. This antibiofilm coating exhibited a controlled release of CIT and THY over a period of 60 d. It successfully prevented MRSA adherence under laboratory conditions. Yahya et al. (2024) highlighted that edible antibiofilm coatings hold considerable promise for mitigating biofilm-mediated problems in the food industry.

Genetic engineering also offers a cutting-edge strategy for controlling biofilm-forming pathogens by enhancing the natural resistance of crops. Advances in genetic engineering have enabled the development of crops that produce antimicrobial peptides or enzymes capable of disrupting biofilms. For example, CRISPR-based technologies can be used to edit the genomes of crops or beneficial microbes, enhancing their ability to combat biofilm-forming pathogens (Angel et al. 2021). Alshammari et al. (2023) knocked out genes involved in quorum sensing (QS) (luxS) and adhesion (fimH and bolA) using the CRISPR/Cas9-HDR approach. They found that those mutants reduced EPS matrix production in Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 biofilm. While the adoption of genetically engineered crops faces regulatory and public acceptance challenges, their potential to provide durable and sustainable solutions to biofilm-related problems is significant.

Future Directions

The future of the agriculture industry is poised for transformative changes as it addresses the dual challenges of feeding a growing global population and ensuring environmental sustainability. With the increasing pressures of biofilm-forming phytopathogens, climate change, resource depletion, and the need for food security, the industry must embrace innovative technologies, sustainable practices, and interdisciplinary collaboration to secure its future.

One of the most promising future directions is the adoption of precision agriculture, which leverages advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning, drones, and Internet of Things (IoT) devices to optimize farming practices (Hussein et al. 2024). These technologies enable farmers to monitor crop health, soil conditions, and weather patterns in real-time, allowing for precise application of water, fertilizers, and pesticides. By minimizing waste and maximizing efficiency, precision agriculture can significantly increase yields while reducing the environmental footprint of farming. For example, Schumann et al. (2020) reported that smartphone applications employing deep learning neural networks have shown promising results in identifying pest, disease, and nutrient deficiency symptoms on leaves, with one prototype achieving 89% accuracy for citrus crops. As these technologies become more accessible and affordable, they have the potential to revolutionize farming practices worldwide, particularly in developing regions where resource constraints are most acute.

Addressing the challenges posed by climate change will be a central focus of future agricultural innovation. Climate-smart agriculture (CSA) practices, which aim to increase productivity, enhance resilience, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions, will play a crucial role in adapting to changing climatic conditions (Zheng et al. 2024). For instance, the development of climate-resilient crop varieties, improved water management systems, and agroecological practices can help farmers cope with extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods. Specific CSA technologies, such as using leaf color charts for nitrogen application, soil test kits for fertilizer management, organic matter amendments, and intermittent irrigation, have demonstrated potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 7-23% and increase economic benefits by 42-129% compared to conventional farming practices (Ariani et al. 2018).

Conclusion

The mechanisms of biofilm formation, particularly the role of the bacterial Type III secretion system (T3SS) is important in enhancing pathogenicity and biofilm development in crops. Biofilms, structured microbial communities within a protective matrix, increase pathogen survival and resistance to conventional treatments. Their impact on crop health, including weakened plant immunity and yield reduction, and addresses industry challenges such as ineffective chemical treatments and resistant strains are also explored. Promising solutions, including biocontrol agents, quorum sensing inhibitors, nanotechnology, and edible coatings, are highlighted. There is a need for further research into biofilm dynamics, sustainable management practices, and advanced technologies to mitigate their agricultural impact, offering valuable insights for researchers and stakeholders.

Author Contributions

The authors agree that this research was conducted in the absence of any self-benefits, commercial or financial conflicts and declare the absence of conflicting interests with the funders.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of faculty of applied sciences, universiti teknologi mara, shah alam, selangor, malaysia for providing the research facilities.

Conflicts of Interest statement

The authors agree that this research was conducted in the absence of any self-benefits, commercial or financial conflicts and declare the absence of conflicting interests with the funders.

References

- Acharya, A.; Pal, P. K. Agriculture nanotechnology: Translating research outcome to field applications by influencing environmental sustainability. NanoImpact 2020, 19, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, M.; Ahmad, A.; AlKhulaifi, M.; Al Farraj, D.; Alsudir, S.; Alarawi, M.; Alyamani, E. Reduction of biofilm formation of Escherichia coli by targeting quorum sensing and adhesion genes using the CRISPR/Cas9-HDR approach, and its clinical application on urinary catheter. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2023, 16(8), 1174–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, P. A. S. R. Y.; Raghul, M.; Gowsalya, S.; Paulkumar, K.; Murugan, K. CRISPR interference system: a potential strategy to inhibit pathogenic biofilm in the agri-food sector. In CRISPR and RNAi Systems; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 387–403. [Google Scholar]

- Ariani, M.; Hervani, A.; Setyanto, P. Climate smart agriculture to increase productivity and reduce greenhouse gas emission–a preliminary study. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing, November 2018; Vol. 200, No. 1, p. 012024. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron, J. R.; Worrall, L. J.; Sgourakis, N. G.; DiMaio, F.; Pfuetzner, R. A.; Felise, H. B.; Strynadka, N. C. A refined model of the prototypical Salmonella SPI-1 T3SS basal body reveals the molecular basis for its assembly. PLoS pathogens 2013, 9(4), e1003307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carezzano, M. E.; Paletti Rovey, M. F.; Cappellari, L. D. R.; Gallarato, L. A.; Bogino, P.; Oliva, M. D. L. M.; Giordano, W. Biofilm-forming ability of phytopathogenic bacteria: a review of its involvement in plant stress. Plants 2023, 12(11), 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlier, A.; Burbank, L.; Von Bodman, S. B. Identification and characterization of three novel EsaI/EsaR quorum-sensing controlled stewartan exopolysaccharide biosynthetic genes in Pantoea stewartii ssp. stewartii. Molecular microbiology 2009, 74(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castiblanco, L. F.; Sundin, G. W. New insights on molecular regulation of biofilm formation in plant-associated bacteria. Journal of integrative plant biology 2016, 58(4), 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerutti, A.; Jauneau, A.; Auriac, M. C.; Lauber, E.; Martinez, Y.; Chiarenza, S.; Noël, L. D. Immunity at cauliflower hydathodes controls systemic infection by Xanthomonas campestris pv campestris. Plant Physiology 2017, 174(2), 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalupowicz, L.; Zellermann, E. M.; Fluegel, M.; Dror, O.; Eichenlaub, R.; Gartemann, K. H.; Manulis-Sasson, S. Colonization and movement of GFP-labeled Clavibacter michiganensis subsp. michiganensis during tomato infection. Phytopathology 2012, 102(1), 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Chaudhury, S.; McShan, A. C.; Kaur, K.; De Guzman, R. N. Structure and biophysics of type III secretion in bacteria. Biochemistry 2013, 52(15), 2508–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, N. S.; Valls, M. Current knowledge on the R alstonia solanacearum type III secretion system. Microbial biotechnology 2013, 6(6), 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danhorn, T.; Fuqua, C. Biofilm formation by plant-associated bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2007, 61(1), 401–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, R.; Bolton, M. D.; Thomma, B. P. How filamentous pathogens co-opt plants: the ins and outs of fungal effectors. Current opinion in plant biology 2011, 14(4), 400–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, D.; Isak, M. A.; İzgü, T.; Şimşek, Ö. Green Horizons: Navigating the future of agriculture through sustainable practices. Sustainability 2024, 16(8), 3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemming, H. C.; Percival, S. L.; Walker, J. T. Contamination potential of biofilms in water distribution systems. Water science and technology: water supply 2002, 2(1), 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroud, N. A.; Chatterton, S.; Reid, L. M.; Turkington, T. K.; Tittlemier, S. A.; Gräfenhan, T. Fusarium diseases of Canadian grain crops: impact and disease management strategies. In Future challenges in crop protection against fungal pathogens; New York, NY; Springer New York, 2014; pp. 267–316. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick, R. D.; Ahmad, M.; Majerczak, D. R.; Arroyo-Rodríguez, A. S.; Manulis, S.; Coplin, D. L. Genetic organization of the Pantoea stewartii subsp. stewartii hrp gene cluster and sequence analysis of the hrpA, hrpC, hrpN, and wtsE operons. Molecular plant-microbe interactions 2001, 14(10), 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getahun, S.; Kefale, H.; Gelaye, Y. Application of precision agriculture technologies for sustainable crop production and environmental sustainability: A systematic review. The Scientific World Journal 2024, 2024(1), 2126734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghiasian, M. Microbial biofilms: Beneficial applications for sustainable agriculture. In New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering; Elsevier, 2020; pp. 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Hamdan, H. F.; Ross, E. E. R.; Jalil, M. T. M.; Hashim, M. A.; Yahya, M. F. Z. R. Antibiofilm efficacy and mode of action of Etlingera elatior extracts against Staphylococcus aureus. Malaysian Applied Biology 2024, 53(1), 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horna, G.; Ruiz, J. Type 3 secretion system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiological Research 2021, 246, 126719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Worrall, L. J.; Strynadka, N. C. Towards capture of dynamic assembly and action of the T3SS at near atomic resolution. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2020, 61, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, A. H. A.; Jabbar, K. A.; Mohammed, A.; Al-Jawahry, H. M. AI and IoT in farming: A sustainable approach. In E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences, 2024; Vol. 491, p. 01020. [Google Scholar]

- Johari, N. A.; Aazmi, M. S.; Yahya, M. F. Z. R. FTIR spectroscopic study of inhibition of chloroxylenol-based disinfectant against Salmonella enterica serovar Thyphimurium biofilm. Malaysian Applied Biology 2023, 52(2), 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lin, W.; Dong, T. Differential plant cell responses to Acidovorax citrulli T3SS and T6SS reveal an effective strategy for controlling plant-associated pathogens. MBio 2023, 14(4), e00459-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanarek, P.; Breza-Boruta, B.; Rolbiecki, R. Microbial composition and formation of biofilms in agricultural irrigation systems-a review. Ecohydrology & Hydrobiology 2024, 24(3), 583–590. [Google Scholar]

- Kamaruzzaman, A.N.A.; Mulok, T.E.T.Z.; Nor, N.H.M.; Yahya, M.F.Z.R. FTIR spectral changes in Candida albicans biofilm following exposure to antifungals. Malaysian Applied Biology 2022, 51(4), 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koczan, J. M.; McGrath, M. J.; Zhao, Y.; Sundin, G. W. Contribution of Erwinia amylovora exopolysaccharides amylovoran and levan to biofilm formation: implications in pathogenicity. Phytopathology 2009, 99(11), 1237–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Narayanan, M.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; Li, Z.; Ma, Y. Biofilms formation in plant growth-promoting bacteria for alleviating agro-environmental stress. Science of the total environment 2024, 907, 167774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhedbi-Hajri, N.; Jacques, M. A.; Koebnik, R. Adhesion mechanisms of plant-pathogenic Xanthomonadaceae. In Bacterial adhesion: Chemistry, biology and physics; 2011; pp. 71–89. [Google Scholar]

- Miletic, S.; Goessweiner-Mohr, N.; Marlovits, T. C. The structure of the type III secretion system needle complex. Bacterial Type III Protein Secretion Systems 2020, 67–90. [Google Scholar]

- Panday, D.; Bhusal, N.; Das, S.; Ghalehgolabbehbahani, A. Rooted in nature: the rise, challenges, and potential of organic farming and fertilizers in agroecosystems. Sustainability 2024, 16(4), 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, R. M.; Soares, F. A.; Reis, S.; Nunes, C.; Van Dijck, P. Innovative strategies toward the disassembly of the EPS matrix in bacterial biofilms. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priller, J. P. R.; Reid, S.; Konein, P.; Dietrich, P.; Sonnewald, S. The Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria type-3 effector XopB inhibits plant defence responses by interfering with ROS production. PLoS One 2016, 11(7), e0159107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, K.; Hou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Peterson, B. W.; Flemming, H. C.; van der Mei, H. C. Water in bacterial biofilms: pores and channels, storage and transport functions. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 2021, 48(3), 283–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaudi, L. V.; Giordano, W. An integrated view of biofilm formation in rhizobia. FEMS microbiology letters 2010, 304(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rather, M. A.; Gupta, K.; Mandal, M. Impact of microbial biofilm on crop productivity and agricultural sustainability. In Microbes in land use change management; Elsevier, 2021; pp. 451–469. [Google Scholar]

- Sabino, Y. N. V.; de Araújo Domingues, K. C.; Mathur, H.; Gómez-Mascaraque, L. G.; Drouin, G.; Martínez-Abad, A.; Mantovani, H. C. Exopolysaccharides produced by Bacillus spp. inhibit biofilm formation by Staphylococcus aureus strains associated with bovine mastitis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2023, 253, 126689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, A.; Mungofa, P.; Waldo, L.; Oswalt, C. Smartphone App Under Development for Diagnosing Citrus Leaf Symptoms. In EDIS; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, Y.; van der Wolf, J.; Visser, R. G.; van Heusden, S. Bacterial canker of tomato: current knowledge of detection, management, resistance, and interactions. Plant Disease 2015, 99(1), 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Karnwal, A. Biological strategies against biofilms. In Microbial Biotechnology: Basic Research and Applications; 2020; pp. 205–232. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, H.; Alvarez-Morales, A.; Barber, C. E.; Daniels, M. J.; Dow, J. M. A two-component system involving an HD-GYP domain protein links cell–cell signalling to pathogenicity gene expression in Xanthomonas campestris. Molecular microbiology 2000, 38(5), 986–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syahputri, D.; Lubis, S.; Anggraini, B. Analisis Peran Sektor Pertanian Dalam Pengurangan Kemiskinan dan Peningkatan Kesejahteraan di Negara-Negara Berkembang. Jurnal Ekonomi, Bisnis Dan Manajemen 2024, 3(1), 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tilburg Bernardes, E.; Charron-Mazenod, L.; Reading, D. J.; Reckseidler-Zenteno, S. L.; Lewenza, S. Exopolysaccharide-repressing small molecules with antibiofilm and antivirulence activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 2017, 61(5), 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Xu, Q.; Taylor, L. E., II; Baker, J. O.; Tucker, M. P.; Ding, S. Y. Natural paradigms of plant cell wall degradation. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2009, 20(3), 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaacob, M. F.; Murata, A.; Nor, N. H. M.; Jesse, F. F. A.; Yahya, M. F. Z. R. Biochemical composition, morphology and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis biofilm. Journal of King Saud University-Science 2021, 33(1), 101225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, M. F. Z. R.; Alias, Z.; Karsani, S. A. Subtractive protein profiling of Salmonella typhimurium biofilm treated with DMSO. The Protein Journal 36 2017, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahya, M. F. Z. R.; Nor, N. H. M.; Mahat, M. M.; Siburian, R. Edible coating, food-contact surface coating, and nanosensor for biofilm mitigation plans in food industry. Food Materials Research 2024, 4(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakup, N. F.; Nor, N. H. M.; Mahat, M. M.; Siburian, R.; Yahya, M. F. Z. R. Unveiling the Antibiofilm Arsenal: A Mini Review on Nanoparticles’ Mechanisms and Efficacy in Biofilm Inhibition. International Conference on Science Technology and Social Sciences–Physics, Material and Industrial Technology (ICONSTAS-PMIT 2023); Atlantis Press, 2024; pp. 177–185. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, D.; Yang, P.; Rowan, M.; Ren, S.; Pitts, D. Biofilm accumulation and structure in the flow path of drip emitters using reclaimed wastewater. Transactions of the ASABE 2010, 53(3), 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Ma, R.; Chen, J.; Xie, Q.; Luo, W.; Sun, P.; Guo, J. Discovery of melittin as triple-action agent: broad-spectrum antibacterial, anti-biofilm, and potential anti-quorum sensing activities. Molecules 2024, 29(3), 558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Habimana, O. Biofilm research within irrigation water distribution systems: Trends, knowledge gaps, and future perspectives. Science of the total environment 2019, 673, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaron, S.; Römling, U. Biofilm formation by enteric pathogens and its role in plant colonization and persistence. Microbial biotechnology 2014, 7(6), 496–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusri, M. H.; Nor, N. H. M.; Mahat, M. M.; Siburian, R.; Yahya, M. F. Z. R. Insights into Antibiofilm Mode of Actions of Natural and Synthetic Polymers: A Mini Review. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Science Technology and Social Sciences-Physics, Material and Industrial Technology (ICONSTAS-PMIT 2023). Springer Nature, 2024; p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Ma, W.; He, Q. Climate-smart agricultural practices for enhanced farm productivity, income, resilience, and greenhouse gas mitigation: a comprehensive review. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 2024, 29(4), 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimaro, T.; Thomas, L.; Marondedze, C.; Sgro, G. G.; Garofalo, C. G.; Ficarra, F. A.; Gottig, N. The type III protein secretion system contributes to Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri biofilm formation. Bmc Microbiology 2014, 14, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).