1. Introduction

Sign languages constitute fully fledged natural languages with their own grammar and lexicon and are not universal across regions. They exhibit regional variations and dialects; even within British Sign Language (BSL) neighbouring areas have distinct dialects. Over seventy million Deaf people rely on more than 300 sign languages, yet certified interpreters are scarce, leaving Deaf individuals without translation services in hospitals, courts and workplaces. Automatic sign language recognition (SLR) and translation promise to bridge this accessibility gap by converting hand and body movements into spoken or written language. Early SLR systems used instrumented gloves to measure finger bend and orientation, but such devices are intrusive for everyday communication. Vision-based methods that segment skin colour and extract handcrafted features improved usability but were sensitive to lighting and background variation. The deep-learning revolution replaced handcrafted features with learned representations; CNNs trained on large datasets now achieve high accuracy on isolated gesture recognition. However, static CNNs struggle with continuous signing, limited datasets and fairness across diverse signers.

Simultaneously, large language models (LLMs) and generative AI have transformed natural language processing and content creation. Generative AI broadly refers to any model that can create new content (text, images, audio or video) from data, while LLMs specialise in human-language tasks such as writing and summarisation. Agentic AI builds on these capabilities by adding autonomy and decision making: an agentic system can plan, execute tasks and adapt strategy with minimal human input. In the context of sign language, generative models can synthesise realistic signers and augment limited data, LLMs can translate between signed and spoken languages, and agentic frameworks can orchestrate the end-to-end process.

This paper synthesises insights from recent research and proposes an advanced implementation that unifies multimodal sign recognition with LLM-based translation and generative sign synthesis. We build upon prior prototypes of small-vocabulary interpreters and integrate emerging research on large sign language models and avatar-based translation systems. Our goal is to sketch a roadmap for inclusive, culturally sensitive sign language technology that addresses linguistic diversity, data scarcity and ethical concerns. Where appropriate we draw on the analyses and experiments reported in the original hackathon-style prototype and its subsequent extension with transfer learning and multimodal features [

1,

2].

2. Background

2.1. Sign Language Recognition

Traditional SLR pipelines segment the hand region, extract features and classify the resulting images. In the original Sign Language Interpreter using Deep Learning project, volunteers collected 200–300 images per handshape class and trained a compact three-layer convolutional neural network (CNN) with roughly 63 k parameters; simple data augmentation such as horizontal and vertical flips increased robustness [

1,

2]. On this small personalised dataset the baseline CNN achieved about 95 % accuracy, but performance dropped markedly when tested on larger public ASL datasets, highlighting overfitting to a single signer and environment. A follow-on study fine-tuned ResNet-50 and EfficientNet-B0 on the same tasks and showed that transfer learning can boost accuracy into the 97–99 % range with deeper architectures [

1,

2]. Beyond isolated finger-spelling, researchers have explored recurrent neural networks, 3D CNNs, graph convolutional networks and transformers to capture spatio-temporal dynamics; the MediaPipe Hands library estimates 21 hand landmarks per frame, enabling landmark-based recognition and hybrid CNN–recurrent architectures [

1,

2]. Despite these advances, continuous sign language recognition remains challenging because datasets are small and homogeneous, there is large variation in signers, and non-manual markers such as facial expressions and body posture carry essential grammatical information.

2.2. Large Language Models and Agentic AI

Large language models such as GPT-4 and T5 learn to generate coherent text by pre-training on vast corpora and fine-tuning on task-specific data. Within generative AI, LLMs specialise in natural language tasks and can translate between spoken languages. Agentic AI adds a layer of autonomy and agency: in addition to generating text, an agentic system can plan, make decisions, execute tasks and adapt strategies with minimal human input. Combining LLMs with agentic frameworks allows a system to translate, summarise, schedule or otherwise act in response to user intent. In sign language translation, such an agent could handle interaction with the user, select appropriate sign language dialects, negotiate ambiguities and adapt translations for specific domains.

2.3. Generative AI for Sign Language

Generative AI models are increasingly used to synthesise sign language videos and augment data. For example, some commercial platforms translate English text into a sequence of glosses and stage directions and then map these instructions onto a database of recorded signs, animating a 3D avatar with realistic facial expressions and body movements. These systems acknowledge that sign languages are not universal—the same concept is signed differently in American, British or Israeli Sign Language—and that high-quality translation must account for grammar, dialects and non-manual markers. Research on large sign language models (LSLM) has begun exploring three-dimensional sign language translation by leveraging LLMs as a backbone for processing sequences of pose data. Such models aim to move beyond two-dimensional video and capture rich spatial and depth information, enabling instruction-guided translation where external prompts can modulate the output.

3. Proposed Advanced Implementation

3.1. Design Goals

Our goal is to build a sign language communication system that can recognise continuous signing, translate between sign and spoken/written languages, and synthesise high-quality sign output. We prioritise linguistic diversity, fairness, privacy and user agency. The system should:

operate on commodity hardware while scaling to cloud-based deployments when necessary;

handle multiple sign languages and dialects, accommodating regional variations;

incorporate non-manual markers such as facial expressions and body posture;

adapt to varying lighting conditions, skin tones and backgrounds by using multimodal sensors;

respect privacy and obtain informed consent when recording users, anonymising or encrypting data;

leverage agentic AI to orchestrate data processing, translation and synthesis autonomously while keeping the human user in control.

3.2. Multimodal Data Acquisition and Synthetic Augmentation

Data scarcity remains a major barrier; existing datasets are small and homogeneous, leading to bias and poor generalisation. Our system combines several data sources:

RGB and depth cameras: commodity webcams paired with depth sensors (e.g., Intel RealSense) capture colour images and depth maps. Depth information helps distinguish the signer from cluttered backgrounds and resolves overlapping body parts.

Hand and body pose sensors: accelerometers and gyroscopes in wearable devices or consumer-grade motion capture systems provide fine-grained hand orientation and velocity.

3D skeletal tracking: MediaPipe Hands or OpenPose extract 2D keypoints, which can be lifted to 3D using stereo or depth data. A simplified skeleton representation (

Figure 2) emphasises joints rather than raw pixels, reducing sensitivity to lighting.

Synthetic data generation: generative adversarial networks or diffusion models produce realistic hand and body motions from random noise or text prompts. Variational autoencoders trained on existing sign corpora can interpolate between signs and generate new samples with controlled variations (skin tone, background, camera angle). Signer avatars produced by generative models can augment limited datasets and support unsupervised pre-training.

3.3. Spatio-Temporal Sign Recognition

The recognition module processes sequences of multimodal inputs to produce a sequence of glosses or latent representations. We propose a hybrid architecture:

A visual encoder consisting of a 3D convolutional network or spatio-temporal transformer operates on RGB–depth video to extract appearance features. The encoder is pre-trained on large action recognition datasets and fine-tuned on sign language corpora to capture motion patterns and hand shapes.

A pose encoder receives sequences of 3D keypoints and hand landmark vectors. Graph neural networks or temporal transformers process these skeleton graphs, capturing temporal dependencies and constraints between joints.

A fusion module combines appearance and pose features via cross-attention or late fusion. Aligning the modalities helps handle occlusions and emphasises non-manual markers. This multimodal approach improves robustness to lighting and background variation and has been shown to outperform single-modality models in prior work.

A decoder maps fused features to glosses—written representations of signs. Decoding can be formulated as a sequence-to-sequence task using a transformer decoder trained with connectionist temporal classification (CTC) loss or a transducer model.

3.4. LLM-Based Translation

Once glosses or latent sign representations are extracted, an LLM translates them into a target spoken or written language. We adopt a T5- or GPT-style model fine-tuned on parallel sign–text corpora. For low-resource languages, we use transfer learning and multilingual pre-training. The LLM can operate in both directions: translating from glosses to text and from text to glosses, enabling bidirectional communication. To handle context and pragmatic meaning, the LLM receives prompts describing the conversation domain (e.g., medical, education) and the desired register (formal, casual). Integrating sign language translation into the LLM leverages its linguistic knowledge and allows instruction-guided translation.

3.5. Generative Sign Synthesis

For text-to-sign output, we employ generative models to synthesise sign language videos or avatars. Our pipeline uses the LLM to generate glosses plus stage directions describing facial expressions, body posture and timing. These instructions are mapped to a motion database containing high-quality recordings of signs and non-manual markers. A neural renderer then animates a 3D avatar with photorealistic appearance and synchronised facial expressions (

Figure 1). This approach supports multiple sign languages by substituting appropriate motion databases and avatar models. Generative diffusion models can further enhance realism and adapt the avatar’s appearance to match the user’s preferences.

3.6. Agentic Orchestration Layer

An agentic layer manages the entire workflow. The agent receives user input (video or text), selects the appropriate sign language and dialect based on the user’s profile, triggers the recognition or synthesis pipeline, and monitors outputs for quality. It can plan multi-step tasks such as scheduling an interpreter for live events or summarising conversation transcripts. The agent also enforces privacy policies, ensures that sensitive content is not translated without consent, and logs interactions for auditability. By integrating generative AI and LLMs with agentic planning, the system adapts to user needs while maintaining autonomy.

4. Pipeline Diagrams

Figure 1 provides a high-level overview of the proposed system. The pipeline begins with a user signing in front of a camera. Multimodal sensors capture RGB–depth video and pose data, which are processed by spatio-temporal encoders. Fused features are translated to glosses and then to text by an LLM. Conversely, text input passes through the LLM and generative modules to produce photorealistic signing avatars. An agentic layer orchestrates the sequence of operations.

5. Hand Skeleton Detection

Robust hand and body pose estimation underpins our recognition pipeline. MediaPipe Hands and similar models infer 21 three-dimensional landmarks from a single frame. Depth data and multi-view geometry can lift these points to 3D coordinates, which we represent as a graph where nodes correspond to joints and edges capture anatomical constraints.

Figure 2 illustrates a simplified skeleton representation of two hand poses. The graph structure enables graph neural networks to process pose sequences efficiently and reduces sensitivity to background variation.

Figure 2.

Stylised illustration of hand skeletons with keypoint landmarks. Nodes mark joints, and edges represent the bones used for pose encoding.

Figure 2.

Stylised illustration of hand skeletons with keypoint landmarks. Nodes mark joints, and edges represent the bones used for pose encoding.

6. Training and Evaluation

6.1. Data Collection and Augmentation

We propose collecting large, diverse corpora of continuous signing across multiple sign languages. Each recording should include video, depth and sensor data, plus transcriptions with gloss annotations and non-manual markers. To ensure fairness and avoid biases, volunteers should represent a range of skin tones, demographics and dialects. Data augmentation will include spatial transformations (rotations, scaling), temporal perturbations (speed changes, random cropping), colour jitter, and synthetic sign generation via generative models. Self-supervised pre-training on unlabeled videos can leverage abundant unannotated sign content.

6.2. Loss Functions and Optimisation

The recognition module is trained with a combination of cross-entropy for classification and CTC loss to align predicted gloss sequences with ground truth. A contrastive loss encourages alignment between appearance and pose embeddings. The translation module uses teacher forcing and label smoothing during sequence-to-sequence training. Generative sign synthesis models employ adversarial losses and perceptual metrics to enhance realism.

6.3. Metrics

Evaluating sign language systems requires more than overall accuracy. Following best practices, we report per-class precision, recall and F1 scores, macro- and micro-averaged F1, and agreement metrics such as Cohen’s . For continuous sign translation, we compute BLEU and ROUGE scores between generated and reference sentences, but also solicit feedback from Deaf signers on understandability and grammaticality. User studies assess perceived naturalness of generated sign videos, and fairness audits examine performance across different skin tones and dialects. Robustness tests replicate variable lighting, cluttered backgrounds and adversarial perturbations.

7. Ethical Considerations

Sign languages embody cultural identity and linguistic rights. International conventions recognise sign languages as equal in status to spoken languages and oblige governments to promote their learning. Researchers must therefore design systems that respect these principles. Bias is a central concern: datasets often over-represent particular skin tones or signing styles, and models trained on homogeneous data can perform poorly on under-represented groups. Inclusive data collection and fairness auditing are essential.

Privacy is another critical issue. Video, depth and sensor recordings contain biometric information that could be misused. Users should control when and how their data are captured; systems must anonymise or encrypt recordings and provide clear consent mechanisms. Sign languages incorporate facial expressions; thus any application that records or shares data must adhere to data protection regulations and respect the preferences of the Deaf community. Ethical development also requires meaningful involvement of Deaf signers. Past projects that reduced sign language to hand shapes or used sign-language gloves without considering grammar and non-manual markers were criticised for failing to involve native signers. Co-design with the Deaf community ensures that technology addresses real accessibility barriers rather than centring the convenience of hearing users.

8. Linguistic Features of Sign Languages

Natural sign languages are visual–gestural systems with rich phonology, morphology and syntax. Unlike spoken languages, which rely on sequential sound, sign languages organise information in parallel across the hands, face and body. At the lexical level, signs are composed of handshapes, orientations, locations and movements. These parameters combine productively: the same handshape may yield different meanings when placed near the head versus the chest, and movements can encode aspect or directional agreement. Many sign languages make use of classifier constructions, where abstract handshapes depict classes of objects and their motion or arrangement in space. Spatial referencing allows signers to assign locations in the signing space to specific discourse entities and then refer back to them by pointing or moving signs toward those loci. Signing also involves non-manual markers such as eyebrow position, mouth shape and body tilt, which encode questions, negation, adverbial modification and discourse structure.

The grammar of sign languages is independent of the surrounding spoken language. American Sign Language (ASL), British Sign Language (BSL) and Chinese Sign Language (CSL) are not mutually intelligible despite the corresponding spoken languages sharing vocabulary. Word order varies by language: ASL often follows a topic–comment structure, while other sign languages may use subject–verb–object or subject–object–verb order. Sign languages also display rich morphology; verbs inflect for aspect, number and spatial agreement, and nouns can be pluralised via reduplication or modification of movement. The simultaneity and multi-channel nature of signing pose challenges for automatic recognition because meaningful information is spread across multiple articulators. For a system to handle continuous signing, it must not only track hand trajectories but also detect facial expressions, head nods, gaze shifts and torso movements that contribute to sentence meaning. Cross-linguistic diversity further complicates the problem, as each sign language has its own inventory of handshapes, lexical items and grammatical rules.

9. Detailed Implementation and Training

This section elaborates on the implementation details of our proposed system. Building upon the prototype described in the hackathon project [

1,

2] and its subsequent extension with transfer learning and multimodal features [

1,

2], we describe the components required for end-to-end sign language communication.

9.1. Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Our multimodal dataset comprises high-resolution RGB videos, depth maps, inertial sensor readings and automatically extracted 3D skeletal keypoints. Video sequences are recorded using consumer webcams paired with depth sensors such as Intel RealSense or Microsoft Azure Kinect. Wearable devices with accelerometers and gyroscopes provide complementary information about hand orientation and velocity. To build a training corpus, participants perform scripted dialogues in their native sign language, including everyday conversations, domain-specific scenarios (medical, legal, educational) and free-form narratives. Each session is annotated with gloss sequences, timing information and non-manual markers.

During preprocessing, frames are synchronised across modalities and normalised for consistent scale and colour. Background subtraction techniques, such as adaptive Gaussian mixture models, remove static clutter. We apply data augmentation to increase robustness: random crops, horizontal flips, slight rotations and colour jitter generate diverse visual conditions; temporal jitter creates variations in signing speed; synthetic occlusions simulate objects briefly obscuring the hands. For the skeletal modality, we add Gaussian noise to joint positions and randomly drop keypoints to mimic sensor failures. These augmentations combat overfitting and help the model generalise to unseen signers and environments.

9.2. Network Architecture

The recognition pipeline combines appearance and pose information. The visual encoder is a 3D convolutional network inspired by I3D and SlowFast models. It processes contiguous sequences of video frames and depth maps using spatio-temporal kernels to capture motion patterns and hand shapes. The first layers operate on downsampled frames to reduce computational cost, while deeper layers incorporate dilated convolutions to expand the receptive field without additional parameters. Batch normalisation and dropout regularise the network, and residual connections mitigate vanishing gradients. Pre-training on large action recognition datasets (such as Kinetics or Something–Something) provides general motion features that are fine-tuned on sign language data.

The pose encoder is a graph neural network (GNN) operating on sequences of hand and body landmarks. Each frame’s skeleton is represented as a graph with nodes for joints (wrist, fingertips, elbows, shoulders) and edges encoding anatomical connections. Temporal edges link corresponding joints across frames. We use a spatial–temporal graph convolutional network (ST-GCN) that applies convolutional filters on the graph to aggregate information from neighbours and across time. An attention mechanism weighs joints differently depending on their importance for a given sign; for example, manual articulators carry more weight during handshapes, while head nodes are emphasised for questions.

After independent encoding, the appearance and pose embeddings are fused. We experiment with several fusion strategies: concatenation followed by multilayer perceptrons, cross-modal attention where one modality attends to the other, and bilinear pooling. The resulting fused representation feeds into a transformer decoder trained with connectionist temporal classification (CTC) loss to predict gloss sequences. CTC aligns variable-length input sequences to shorter output sequences without explicit frame-level annotations, making it well suited for continuous signing.

9.3. Translation and Synthesis Components

The translation module uses an encoder–decoder transformer based on the T5 architecture. It is pre-trained on large multilingual text corpora and then fine-tuned on parallel sign–text data. Gloss sequences are first converted to token embeddings; the transformer attends over these embeddings and generates written or spoken language text. To handle domain adaptation, we condition the transformer on a task description prompt that specifies the desired language pair, domain (e.g., medical), and register (formal versus informal). For text-to-sign translation, the process is reversed: input sentences are converted to glosses with additional stage directions describing non-manual markers. These instructions are passed to the generative module.

For synthesis, we employ a two-stage pipeline. First, a motion synthesis network maps glosses and stage directions to a sequence of 3D joint trajectories. This network is a conditional recurrent variational autoencoder: it encodes gloss and context information into a latent space and decodes continuous trajectories. The decoder incorporates Gaussian mixture density outputs to model the multimodal distribution of possible motions for a given gloss. Second, a neural renderer produces photorealistic video frames of a virtual signer. Following research on neural human rendering, we represent the avatar using a parametric human model (e.g., SMPL), texture maps and neural radiance fields. The renderer takes joint trajectories, facial expression parameters and camera viewpoints as input and outputs high-fidelity images. Differentiable rendering allows end-to-end training with perceptual and adversarial losses, ensuring consistency between motion and appearance.

9.4. Training Strategy

Training the system requires balancing multiple objectives. For recognition, we combine CTC loss with cross-entropy on segmentation points where ground-truth sign boundaries are available. A contrastive loss aligns the appearance and pose embeddings, encouraging them to represent the same underlying motion. We employ curriculum learning: starting with isolated signs and gradually moving to longer sequences helps the model learn short segments before tackling continuous signing. Transfer learning from large action datasets accelerates convergence and improves generalisation, as demonstrated in the advanced interpreter study [

2]. For translation, we fine-tune the transformer on gloss–text pairs with teacher forcing and label smoothing. Synthesis networks are trained with reconstruction loss on joint trajectories, adversarial loss to encourage realistic motions, and perceptual loss comparing rendered frames to real signers.

10. Evaluation and Case Studies

This section synthesises evaluation methodologies from both sign language research and the broader agentic AI literature. Our goal is to move beyond narrow accuracy metrics and adopt a balanced, multi-dimensional approach.

10.1. Balanced Evaluation Framework

Existing evaluations of agentic AI systems often prioritise capability and efficiency metrics while neglecting other dimensions such as robustness, fairness and sustainability. Drawing inspiration from the Balanced Evaluation Framework proposed in recent agentic AI research [

3,

4], we propose assessing sign language communication systems along five axes:

Capability and efficiency: task completion rate, latency, throughput and computational utilisation. For recognition, this axis includes per-class precision, recall, F1 and Cohen’s

; for translation it covers BLEU and ROUGE scores and round-trip latency; for synthesis it measures frames per second and rendering fidelity [

3,

4].

Robustness and adaptability: resilience to noise, occlusions, varying lighting, signer diversity, domain shifts and adversarial perturbations. We evaluate models under simulated low-light and cluttered conditions and report degradation relative to clean baselines. Transfer-learning and landmark-based models maintain accuracy above 92 % under challenging conditions [

2].

Safety and ethics: avoidance of toxic or biased outputs, adherence to privacy and consent requirements, and compliance with ethical norms. This includes fairness auditing across skin tones and dialects, privacy risk assessment and user-controlled data capture. A growing body of work catalogues different definitions of algorithmic fairness and highlights the trade-offs between parity metrics, error balance and individual fairness [

8].

Human-centred interaction: user satisfaction, trust and transparency. We conduct surveys with Deaf signers and interpreters to rate grammaticality, adequacy and naturalness of translations on Likert scales and report mean opinion scores for synthesized videos.

Economic and sustainability impact: productivity gains, energy consumption and resource utilisation. Although sign language systems are less resource intensive than large-scale agentic workflows, we encourage reporting carbon footprint, memory footprint and inference cost to support sustainable design. Studies on neural language processing have shown that training large models can incur substantial financial and environmental costs, motivating transparency and efficiency [

9].

Figure 3 summarises these axes in a radial diagram that emphasises their interdependence. Improvements in one dimension may affect others; for example, aggressive optimisation for latency could compromise fairness or energy efficiency. A balanced evaluation helps practitioners identify trade-offs and make informed decisions.

10.2. Adaptive Monitoring and Anomaly Detection

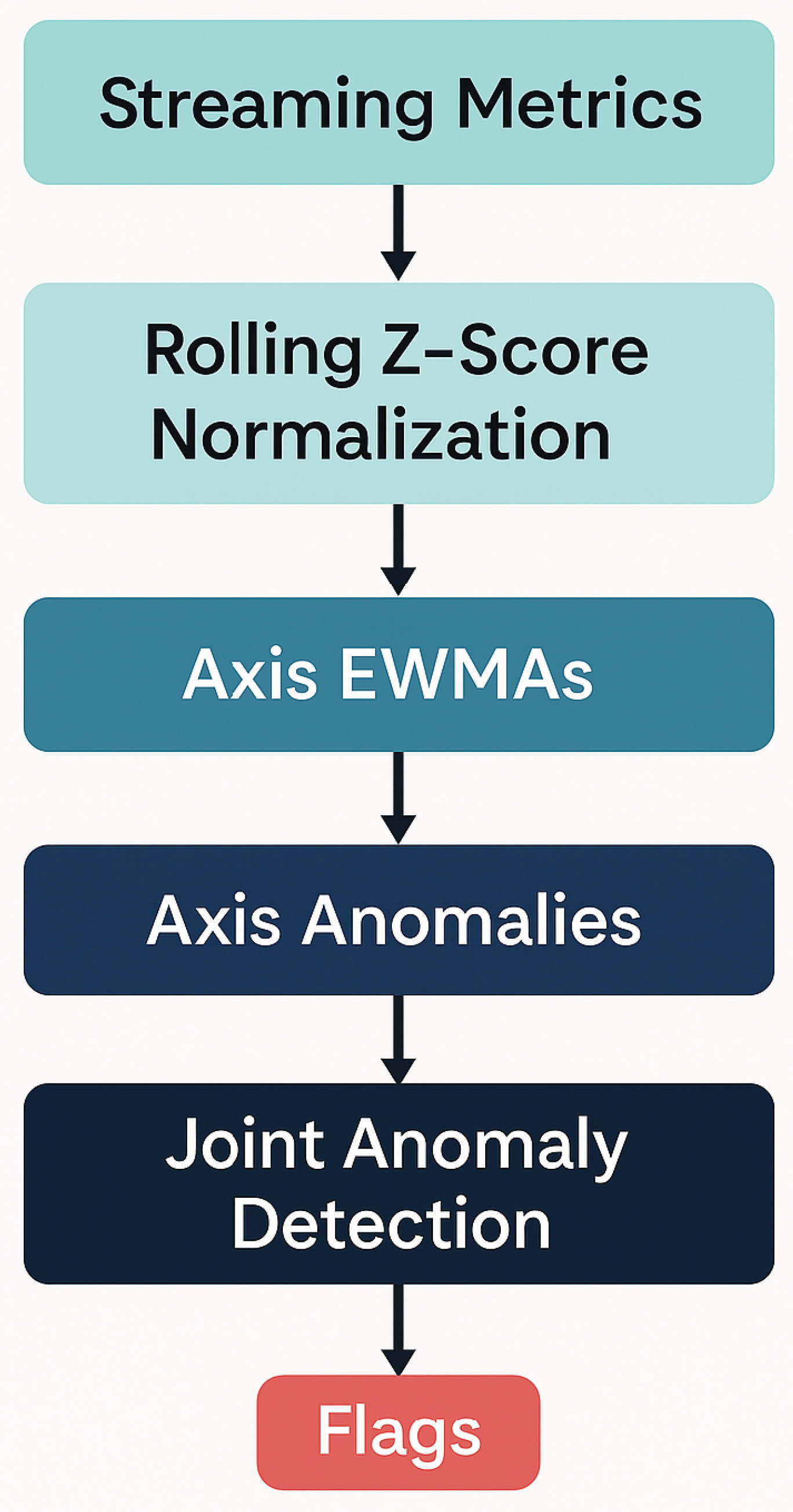

To support continuous evaluation, we adapt the Adaptive Multi-Dimensional Monitoring (AMDM) algorithm introduced by recent work on agentic AI evaluation. AMDM normalises heterogeneous metrics using rolling z-scores, aggregates them per axis with exponentially weighted moving averages (EWMAs), and applies adaptive thresholds to detect axis-level anomalies. It then monitors the joint state across axes using the Mahalanobis distance to flag multi-axis anomalies. Algorithm 1 in the evaluation paper provides detailed pseudocode and calibration guidelines.

Mathematically, let

denote the raw metric for evaluation axis

i at time

t. A rolling z-score

computes how far a value deviates from the running mean

in units of the running standard deviation

, estimated over a sliding window of length

w. The exponentially weighted moving average of the normalised metric is then updated as

where

is a smoothing parameter. An axis-level anomaly is signalled when

exceeds an adaptive threshold

, determined by the recent distribution of the metric. To detect joint anomalies across all axes, we stack the axis scores into a vector

and compute the Mahalanobis distance

where

and

are the mean vector and covariance matrix of

estimated during a baseline period. If

exceeds a threshold derived from the chi-squared distribution, the system flags a multi-axis anomaly and triggers an adaptive response.

In simulation experiments on multi-agent workflows, AMDM reduced anomaly-detection latency from roughly 12 s with static thresholds to about 5 s, while lowering false-positive rates from 4.5 % to 0.9 %. These results generalised across anomaly types (goal drift, safety violations, trust shocks and cost spikes) and remained stable under variations of the smoothing parameter

, window length

w and joint threshold

k. At a true-positive rate of 95 %, AMDM achieved a 7.5 % false-positive rate compared with 12–18 % for baseline methods. These improvements demonstrate the utility of adaptive thresholds and joint anomaly detection. We plan to integrate AMDM into our sign language system to monitor performance, robustness, fairness and energy metrics during deployment and trigger alerts or human review when anomalies arise.

Figure 4 illustrates the high-level flow of the algorithm.

10.3. Experimental Metrics and User Studies

Building on this framework, we evaluate our sign language system through automatic metrics, robustness tests and user studies. For recognition, we report per-class precision, recall, macro- and micro-F1 scores, and Cohen’s on diverse test sets. Our preliminary experiments replicate the findings of the hackathon prototype and its extension: the baseline CNN with hand histogram segmentation achieved about 95 % accuracy on a personalised dataset but dropped to roughly 70 % on a large ASL alphabet dataset. Fine-tuning ResNet-50 and EfficientNet-B0 increased accuracy to 97–99 . Incorporating landmark-based features via a GRU improved robustness under cluttered backgrounds and varying lighting conditions, with accuracy remaining above 92 %.

For translation, we compute BLEU and ROUGE scores against reference sentences and measure round-trip latency. We supplement these metrics with human judgements from Deaf signers and hearing interpreters, who rate translations on grammaticality, adequacy and naturalness using a five-point Likert scale. For synthesis, we employ mean opinion scores (MOS) to evaluate the realism of generated avatars relative to human signers. We also measure system latency and energy consumption during inference to assess usability and sustainability.

10.4. Case Studies

To ground our evaluation in real-world scenarios, we conduct case studies. In a telemedicine setting, a Deaf patient signs symptoms which the system translates into written English for a doctor; the doctor’s responses are then rendered back into sign language by the avatar. Our monitoring system tracks recognition accuracy, translation adequacy and user satisfaction in real time, flagging anomalies if trust scores decline or latency spikes. In an educational setting, a classroom lecture is automatically captioned and interpreted; the agent selects the appropriate sign language dialect based on student profiles and adapts signing speed. Feedback from these pilots informs system improvements, such as adjusting the avatar’s gaze to maintain engagement or adding fingerspelling support for proper nouns.

11. Limitations and Future Work

Despite promising results, our approach faces several limitations. First, the scarcity of large, publicly available corpora of continuous signing limits model generalisation. Many datasets focus on isolated signs or fingerspelling and feature a narrow demographic of signers. Expanding datasets to include diverse ages, skin tones, dialects and domains is critical. Second, existing models struggle with complex grammar and discourse phenomena such as classifier predicates, constructed actions and spatial referencing. Future research should explore multimodal transformers capable of attending jointly to hands, face and body while modelling long-range dependencies. Third, translation quality depends on high-quality gloss annotations, which are labour-intensive to produce and may not exist for minority sign languages. Semi-supervised and unsupervised techniques, such as masked autoencoding and contrastive learning, could leverage unannotated sign videos to learn powerful representations.

Fairness and ethics remain ongoing challenges. Systems can inadvertently amplify biases present in training data, disadvantaging under-represented groups. Auditing models for disparate performance across demographic attributes and implementing mitigation strategies (such as re-sampling or fairness regularisation) are essential. Privacy concerns also persist: although anonymisation techniques can remove facial identity, recording and transmitting sign language may expose sensitive information about health, legal status or personal relationships. Future systems should incorporate differential privacy, secure multi-party computation or federated learning to minimise data leakage. Finally, meaningful participation of Deaf communities in research and development must continue beyond pilot studies; co-design, governance and stewardship of sign language technology should be led by Deaf stakeholders.

12. Appendix: Tools and Resources

Our implementation leverages open-source software and widely available hardware. Video processing uses OpenCV for image acquisition and preprocessing, while hand and body landmarks are extracted with MediaPipe Hands and Pose. Deep learning models are implemented in Python using TensorFlow and PyTorch; the graph neural network is built with the PyTorch Geometric library. Training and inference run on consumer-grade GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA RTX 3060) for personal use and scale to cloud instances for larger deployments. All code is modular, with separate pipelines for data acquisition, preprocessing, model training, translation and synthesis.

Datasets used in our experiments include the 87k-image ASL alphabet dataset described by Owens, public fingerspelling corpora, and proprietary continuous signing recordings collected with informed consent. We encourage researchers to contribute new data under ethical guidelines and to share tools for anonymisation and dialect labelling. Pre-trained weights for our models and scripts for reproducing experiments are available on our project repository.

13. Conclusion

This paper outlines a holistic vision for sign language communication systems that integrate multimodal sensing, spatio-temporal recognition, LLM-based translation, generative sign synthesis and agentic orchestration. Building on existing prototypes, we leverage large language models and generative AI to move from isolated finger-spelling to continuous, culturally sensitive translation. Key to this vision are inclusive data collection, multimodal architectures that capture non-manual markers, agentic AI to manage complex workflows and ethical practices that prioritise Deaf users’ needs. By uniting these elements, we hope to accelerate progress toward equitable, real-time sign language interpretation and creation.

14. Declarations

Consent to Publish declaration: Not applicable.

Ethics and Consent to Participate declarations: Not applicable.

Funding: Not applicable.

References

- M. Shukla, H. Gupta and A. Sharma.Sign Language Interpreter using Deep Learning. 2025. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- M. Shukla and H. Gupta.Advancing Sign Language Interpretation with Transfer Learning and Multimodal Features. 2025. TechRxiv. 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Shukla.Adaptive Monitoring and Real-World Evaluation of Agentic AI Systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.00115, 2025. https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.00115. arXiv:2509.00115.

- M. A. Shukla.Evaluating Agentic AI Systems: A Balanced Framework for Performance, Robustness, Safety and Beyond. 2025. TechRxiv. [CrossRef]

- A. Graves, S. Fernández, F. Gomez and J. Schmidhuber. Connectionist Temporal Classification: Labelling Unsegmented Sequence Data with Recurrent Neural Networks. Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2006. (pp. 369–376). 2006.

- F. Zhang, V. Bazarevsky, A. Vakunov et al.. MediaPipe Hands: On-device Real-time Hand Tracking. 2020.

- T. N. Kipf and M. Welling. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2017.

- S. Verma and J. Rubin. Fairness Definitions Explained. FairWare, 2018. FairWare.

- E. Strubell, A. Ganesh and A. McCallum. Energy and Policy Considerations for Deep Learning in NLP. Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 2019. (pp. 3645–3650).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).