Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. State of Art

1.2. Cohesiveness in Swarm Organization

- An adaptable cohesion-based flocking approach using APFs to achieve coordinated swarm robotic motion in agricultural fields, incorporating dynamic adjustments in robot formation patterns.

- maintenance of the swarm’s target inter-robot distances, as a measure of cohesiveness, which is ensured through an attraction-repulsion balance during both aggregation and flocking phases.

- Coordination of the swarm’s orientation, as a key aspect of cohesiveness, is achieved via an alignment factor during the transition from aggregation to flocking.

- The model demonstrates adaptability across different formation configurations, and swarm performance is evaluated based on the evolution of cohesion metrics during collective motion.

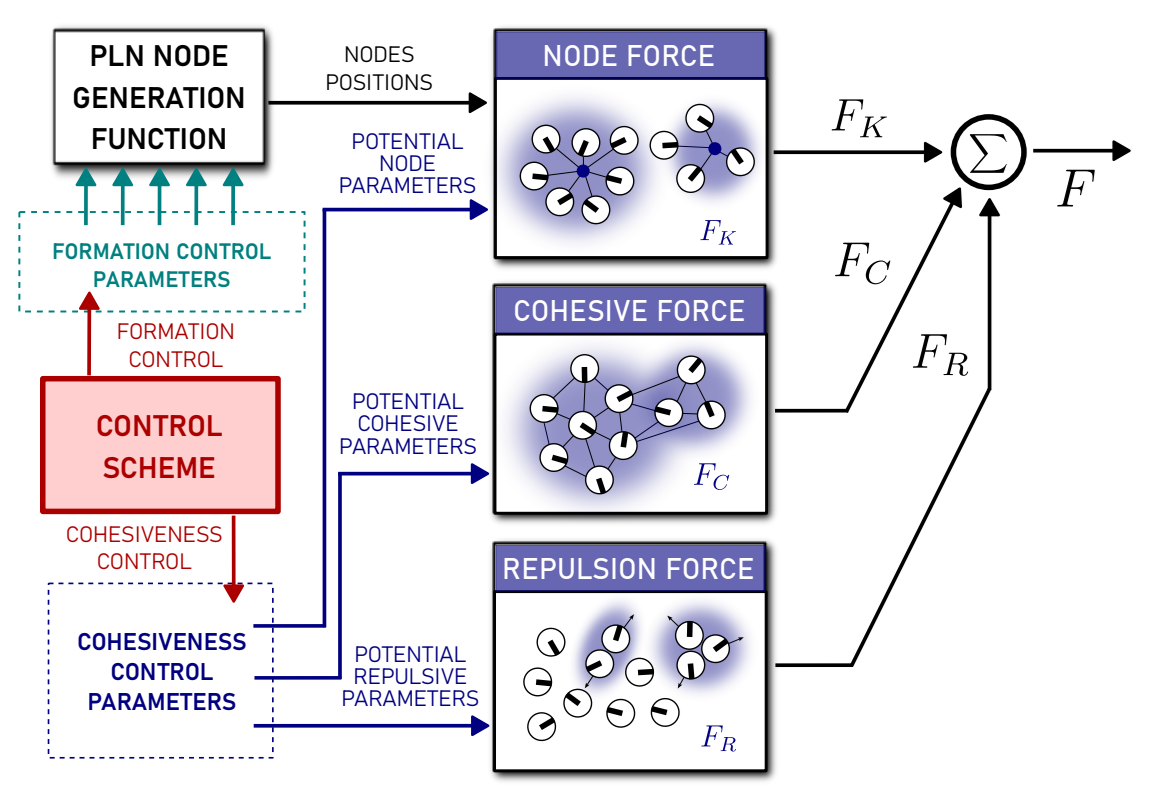

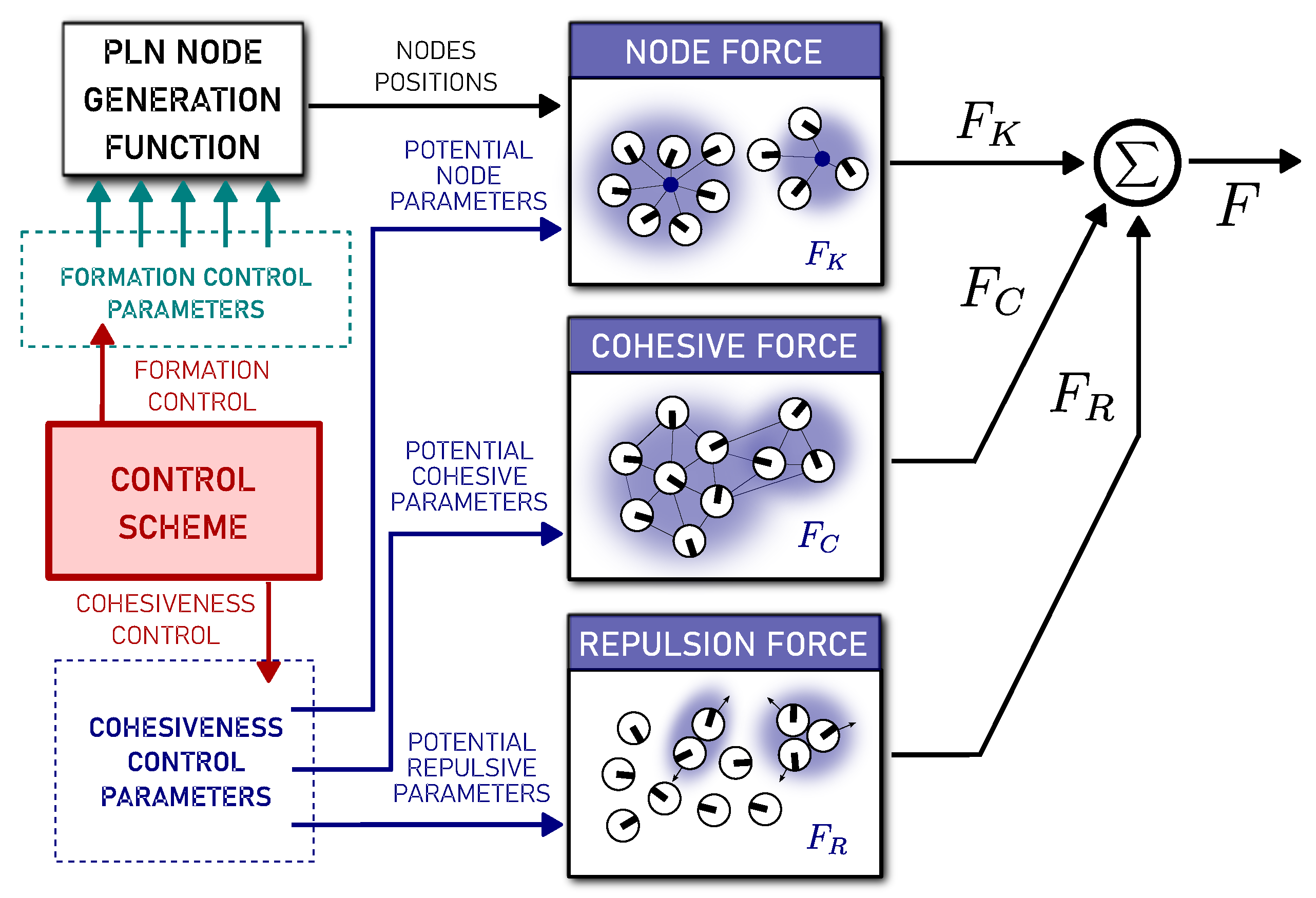

2. Cohesion-Based Potential Linked Nodes

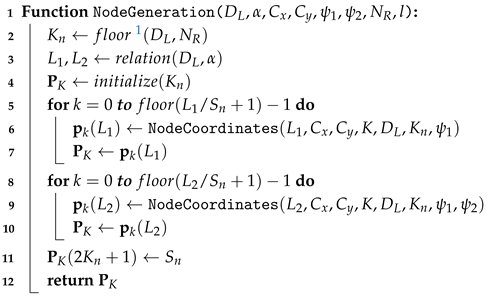

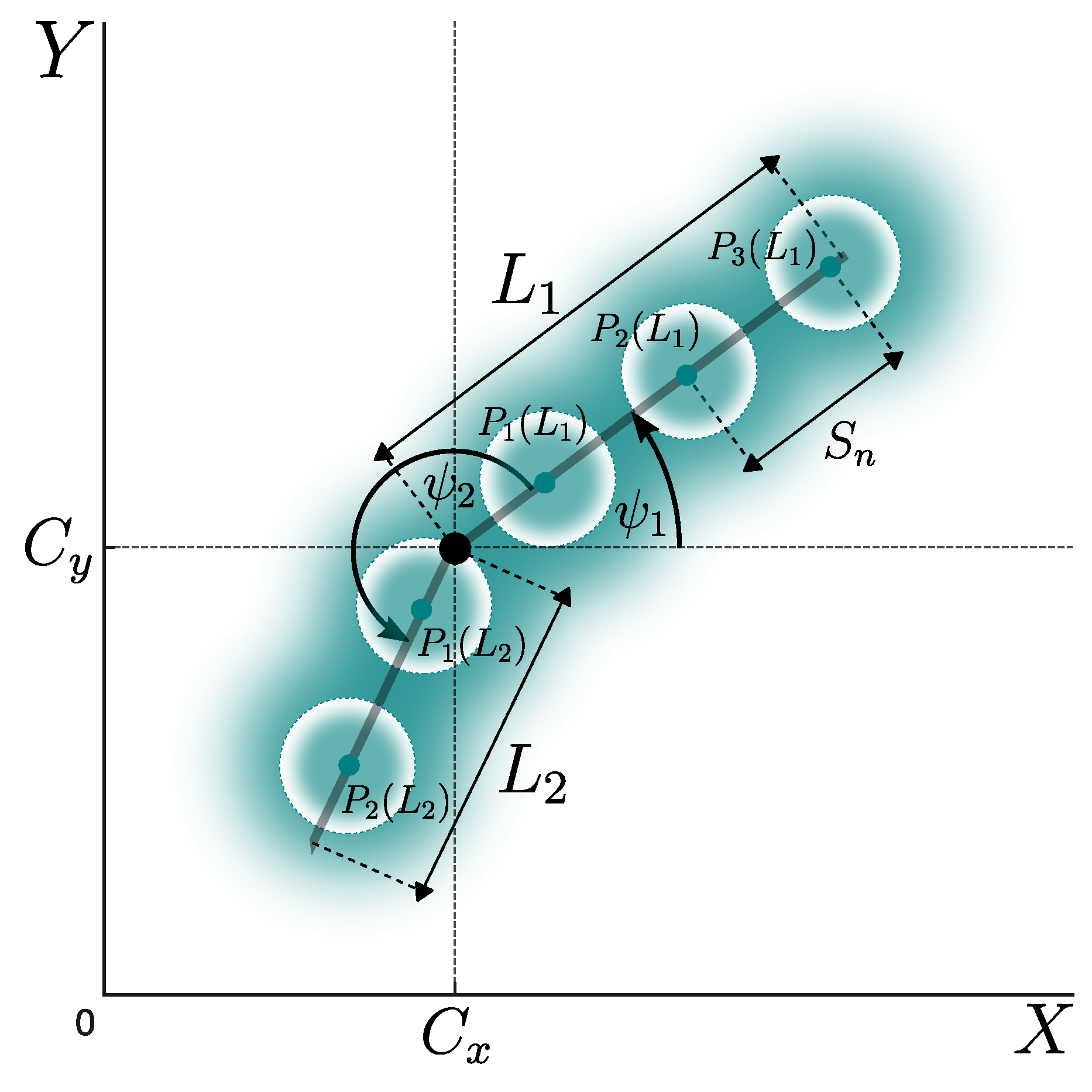

2.1. Nodes Generation

| Algorithm 1: Node Generation Function |

|

Input: Parameters , l. Variables , , , , , .

Output: Set of node coordinates .

|

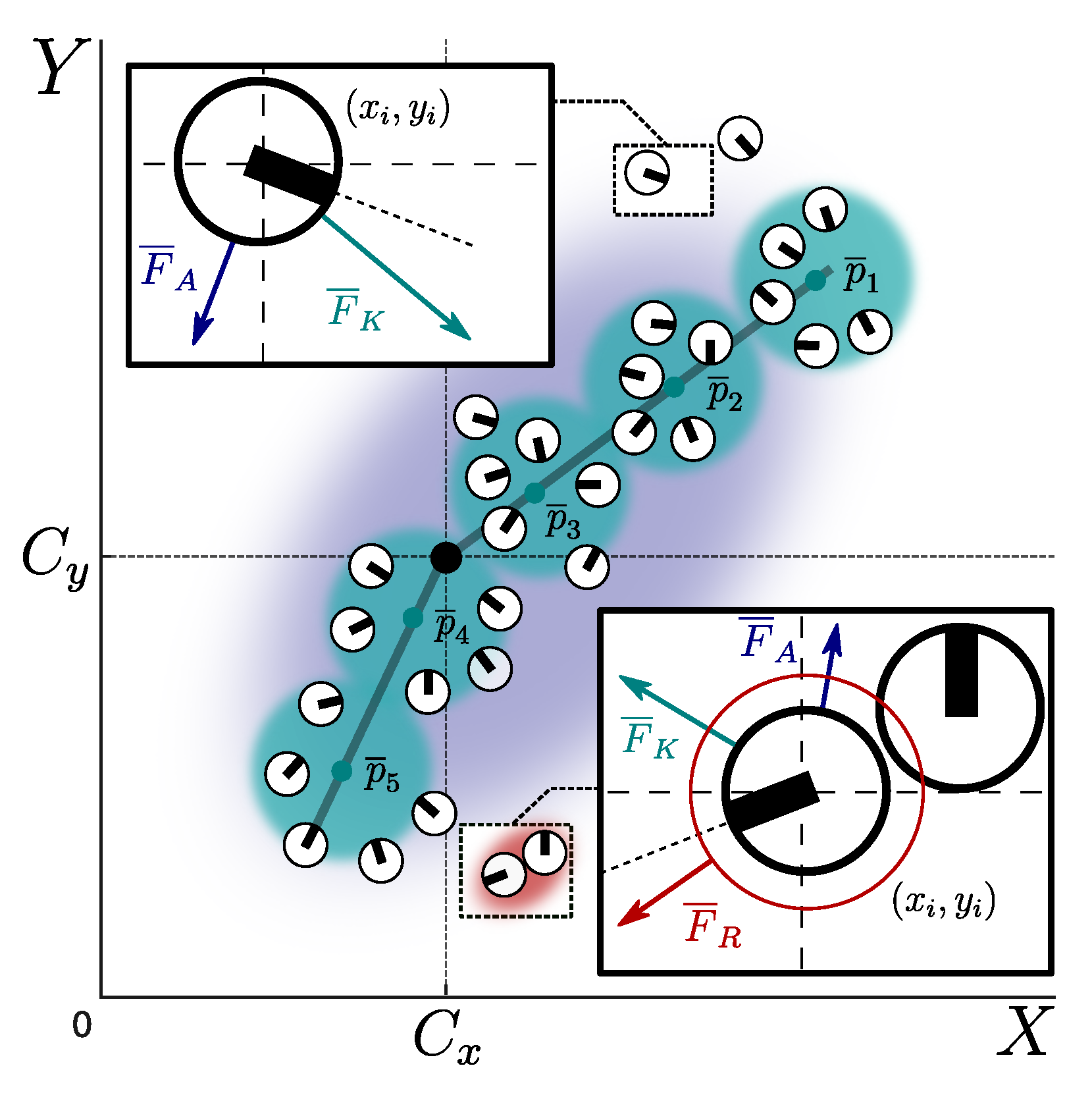

2.2. Swarm Node Cohesion

| Algorithm 2: Node Assignment Procedure |

|

Input: Parameters , , . Variables , .

Output: Set of force vectors under node’s influence .

|

2.3. Attractive and Repulsive Artificial Potential Fields for Cohesiveness

2.4. Attractive and Repulsive Stability

3. Differential Motion Transformation

| Control Category | Parameter | Description | Influence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cohesiveness | Node’s attractive coefficient | APF’s for nodes | |

| Node equilibrium distance | APF’s for nodes | ||

| Cohesive-attractive coefficient | APF’s for attraction | ||

| Attractive equilibrium distance | APF’s for attraction | ||

| Cohesive-repulsive coefficient | APF’s for repulsion | ||

| Repulsive minimum distance | APF’s for repulsion | ||

| Formation | Total structure length | PLN kinematics | |

| Length factor | PLN kinematics | ||

| First link direction | PLN kinematics | ||

| Second link direction | PLN kinematics | ||

| Swarm lineal velocity | PLN dynamics | ||

| Swarm angular velocity | PLN dynamics |

4. Simplified Collective Dynamics

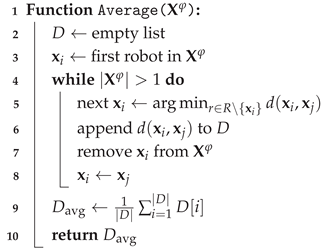

5. Cohesiveness Evaluation

| Algorithm 3: Average distance function |

|

Input: Parameters .

Output: Group’s average distance .

|

6. Experimental Setup and Results

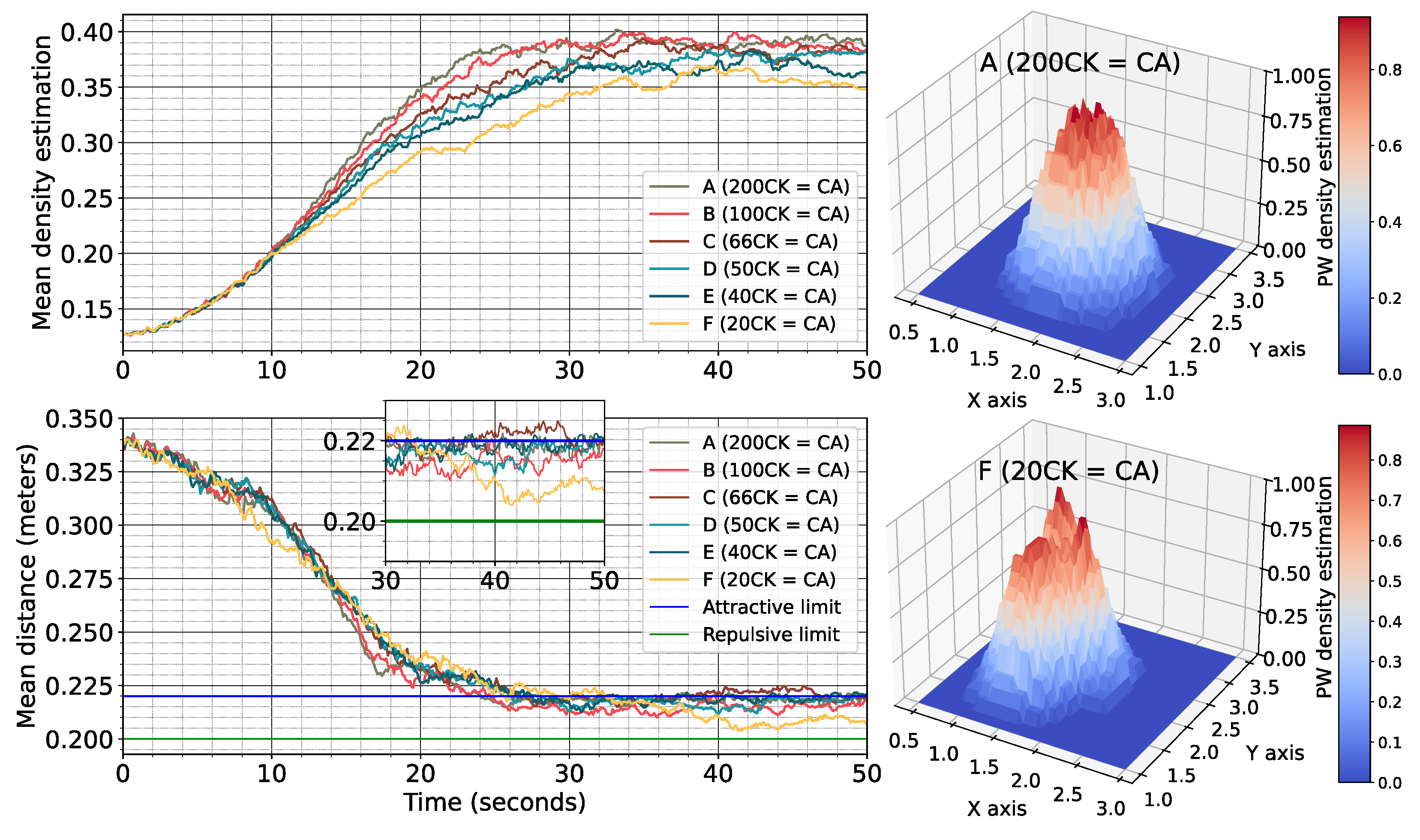

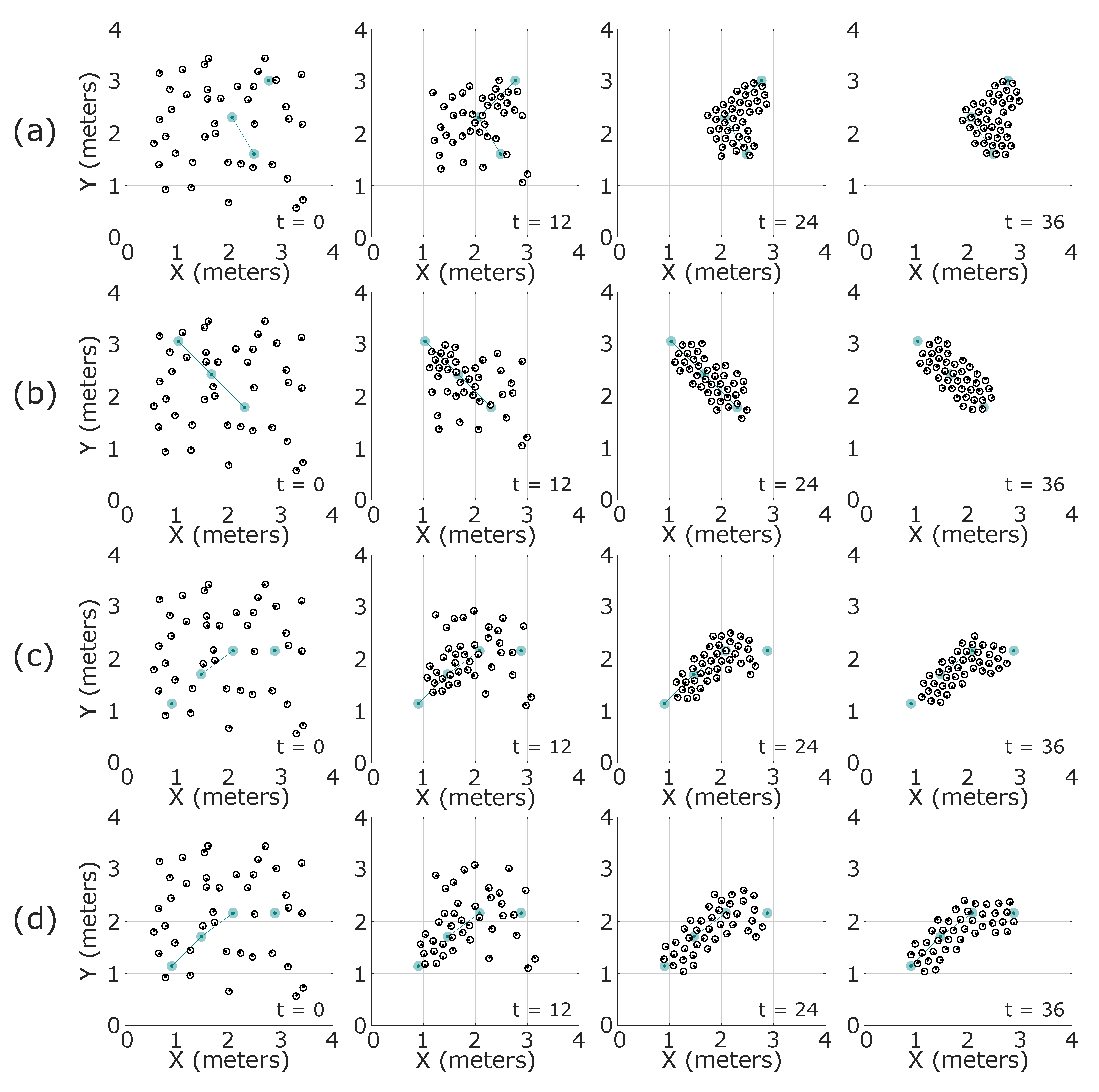

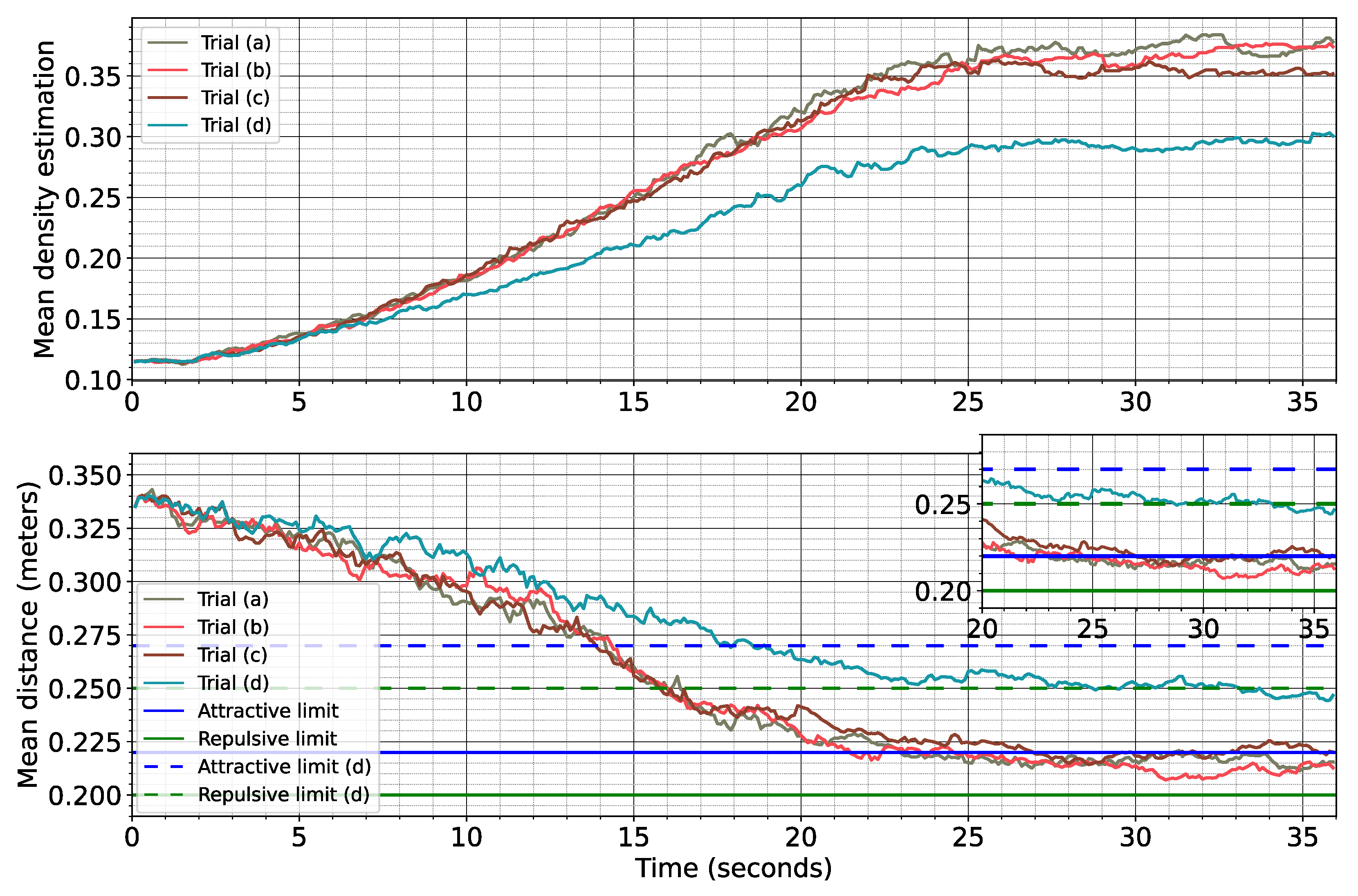

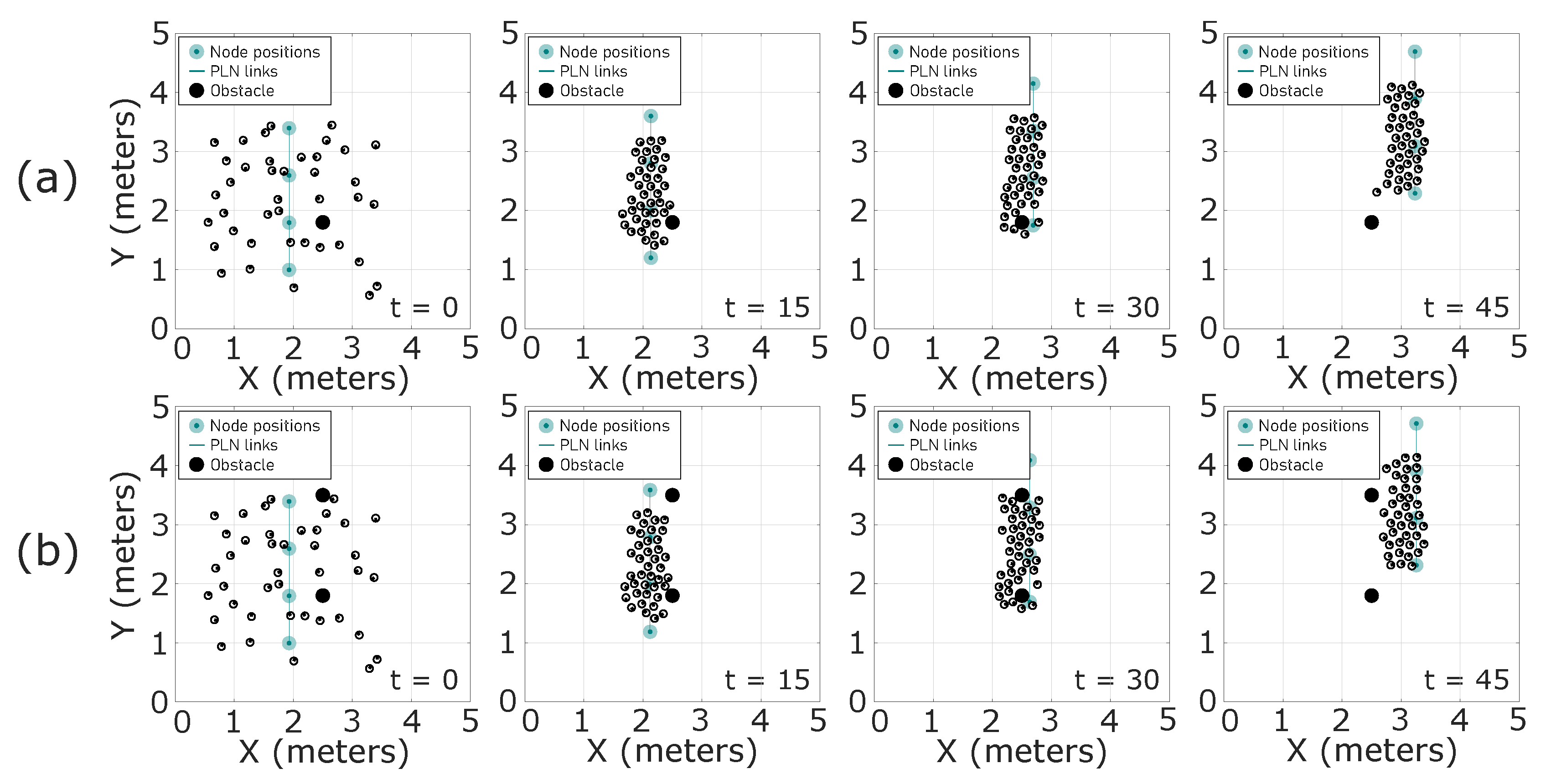

6.1. Performance Assessment for Aggregation Behavior

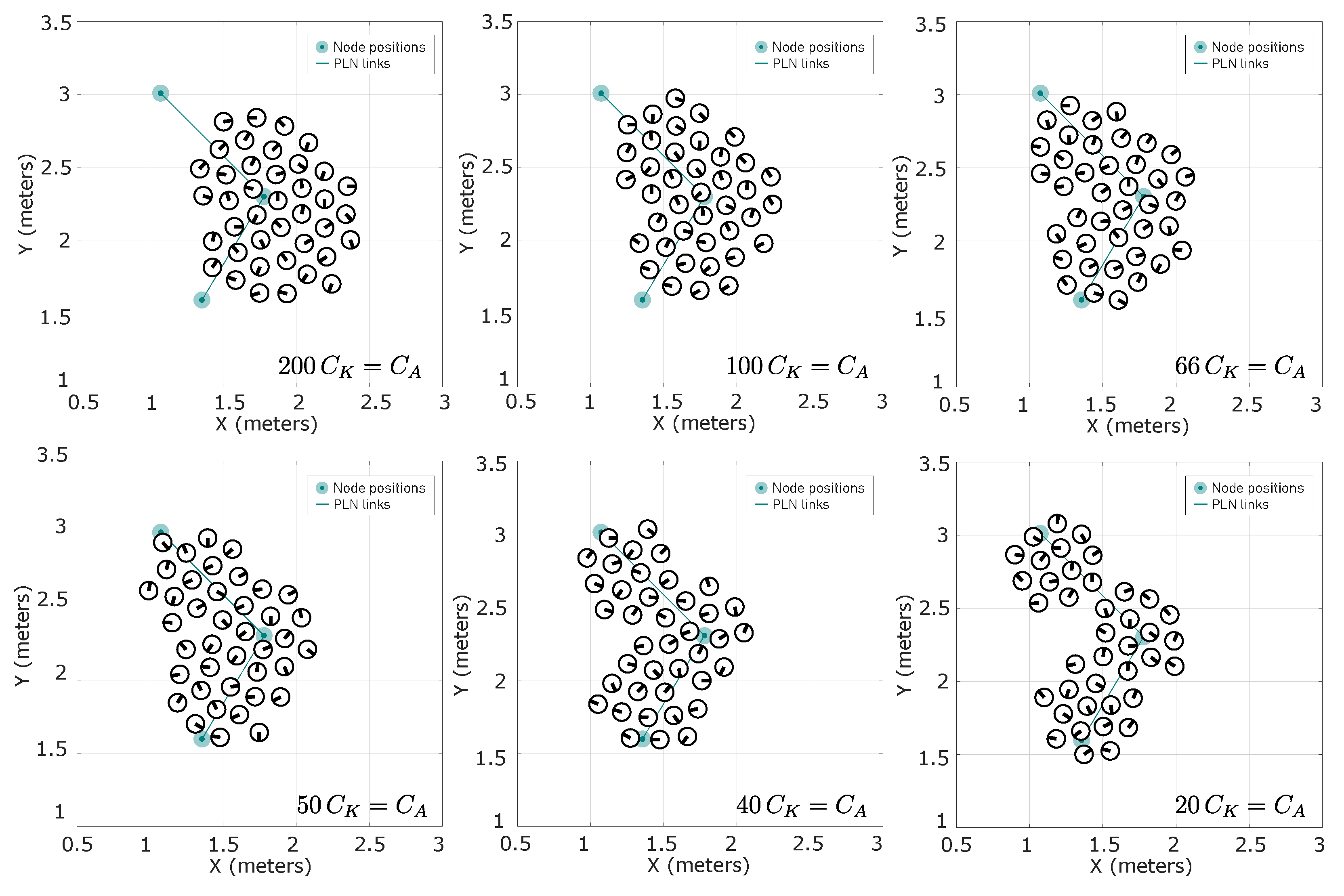

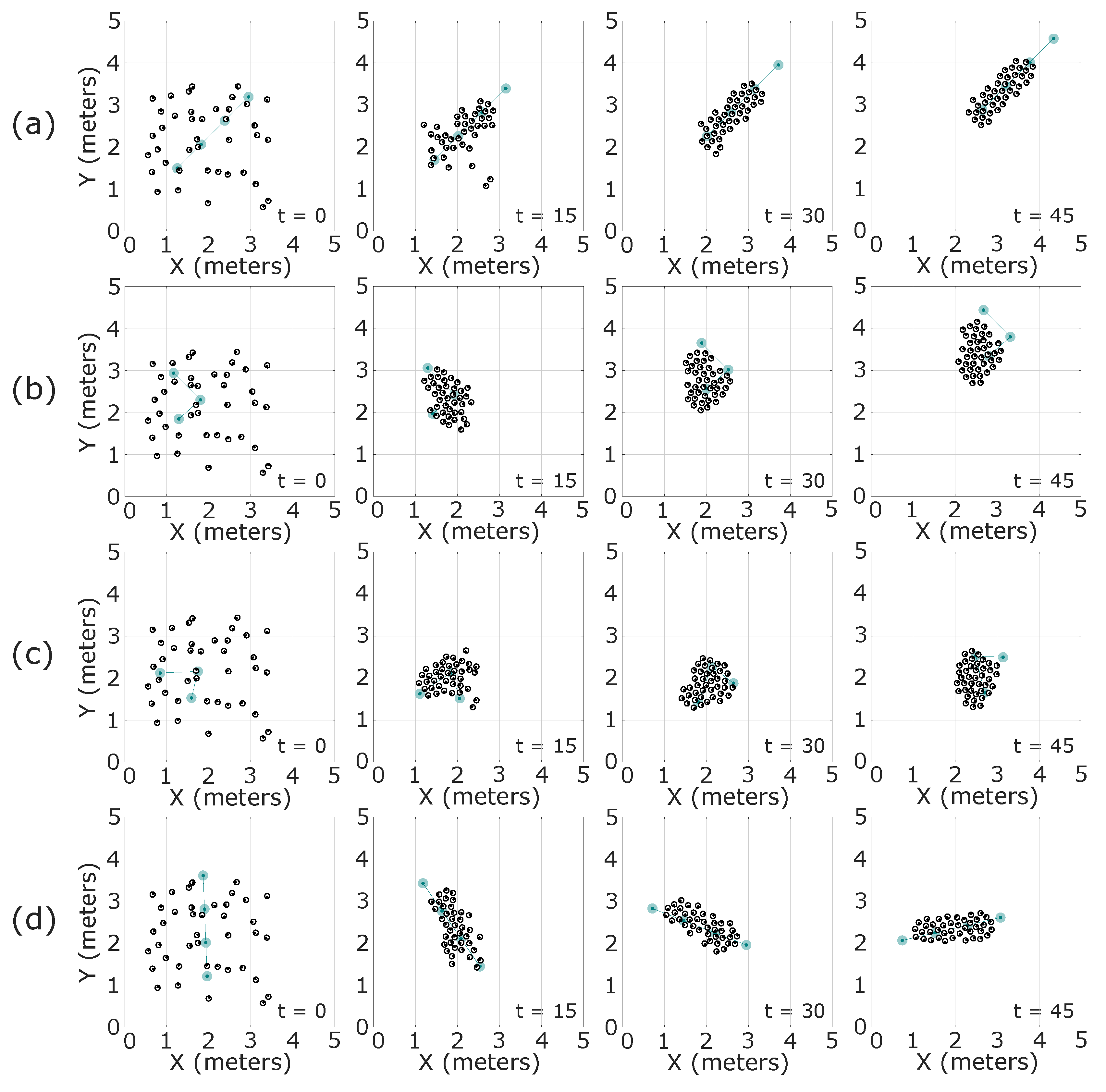

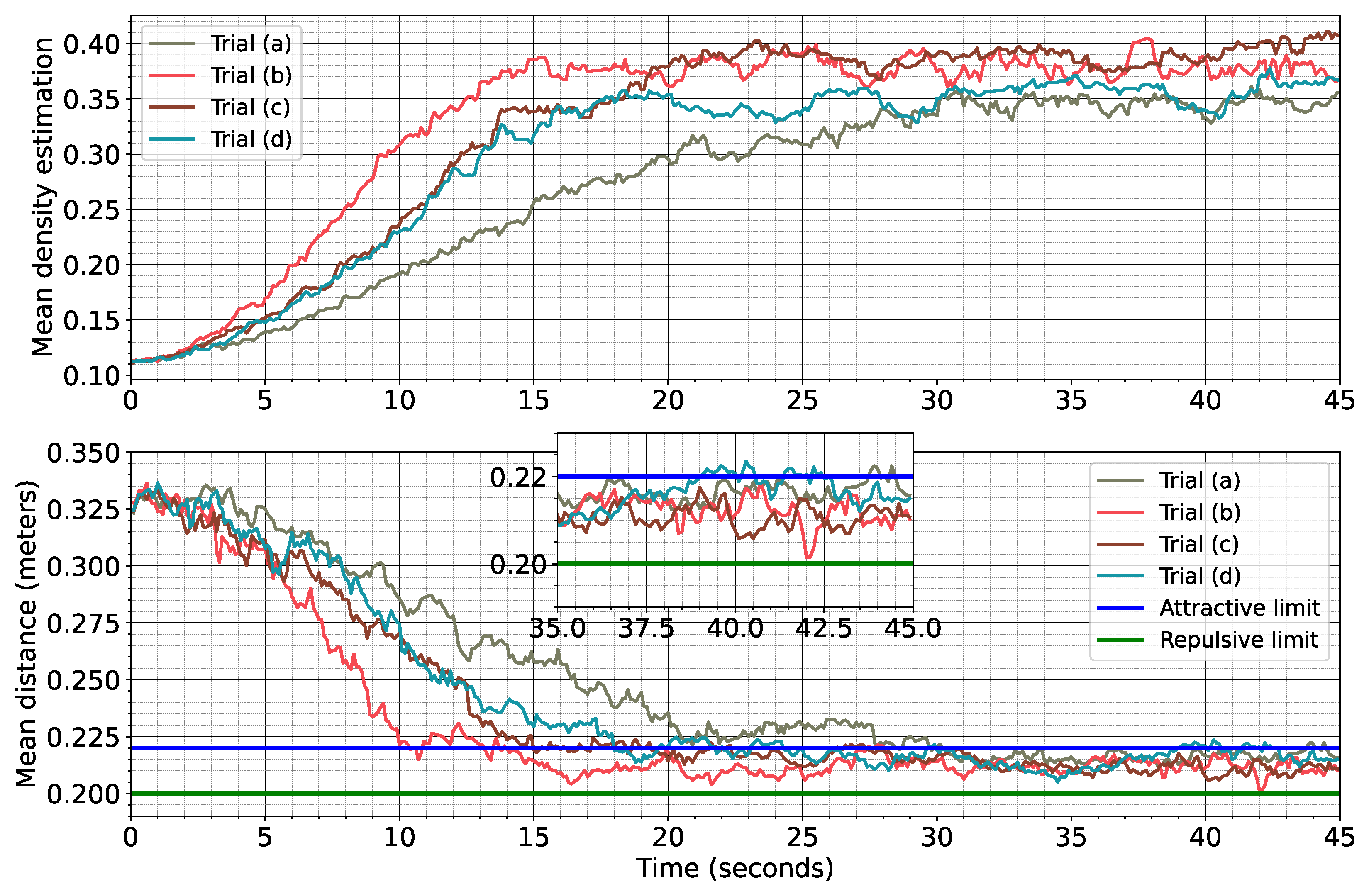

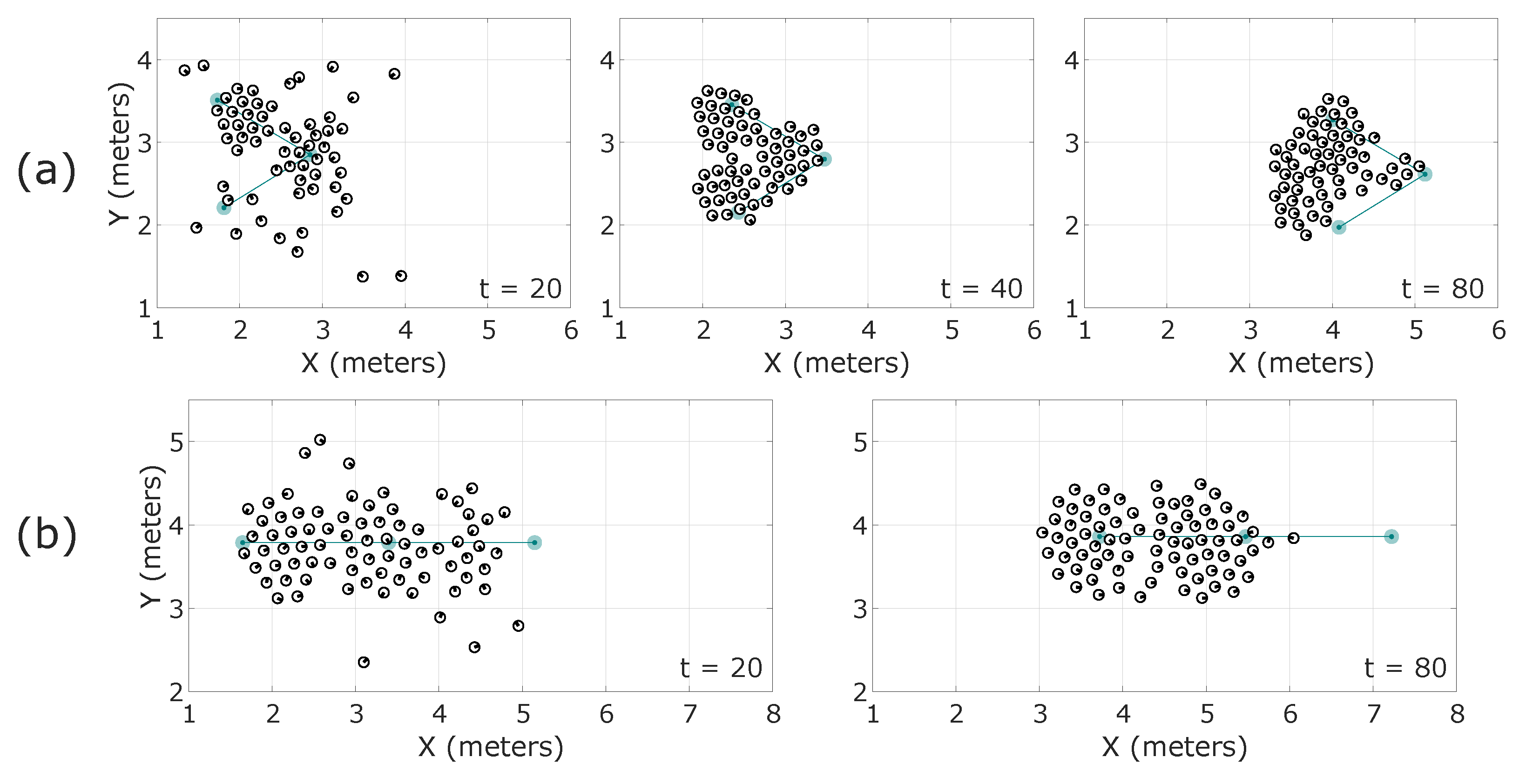

6.2. Performance Assessment for Flocking Formation

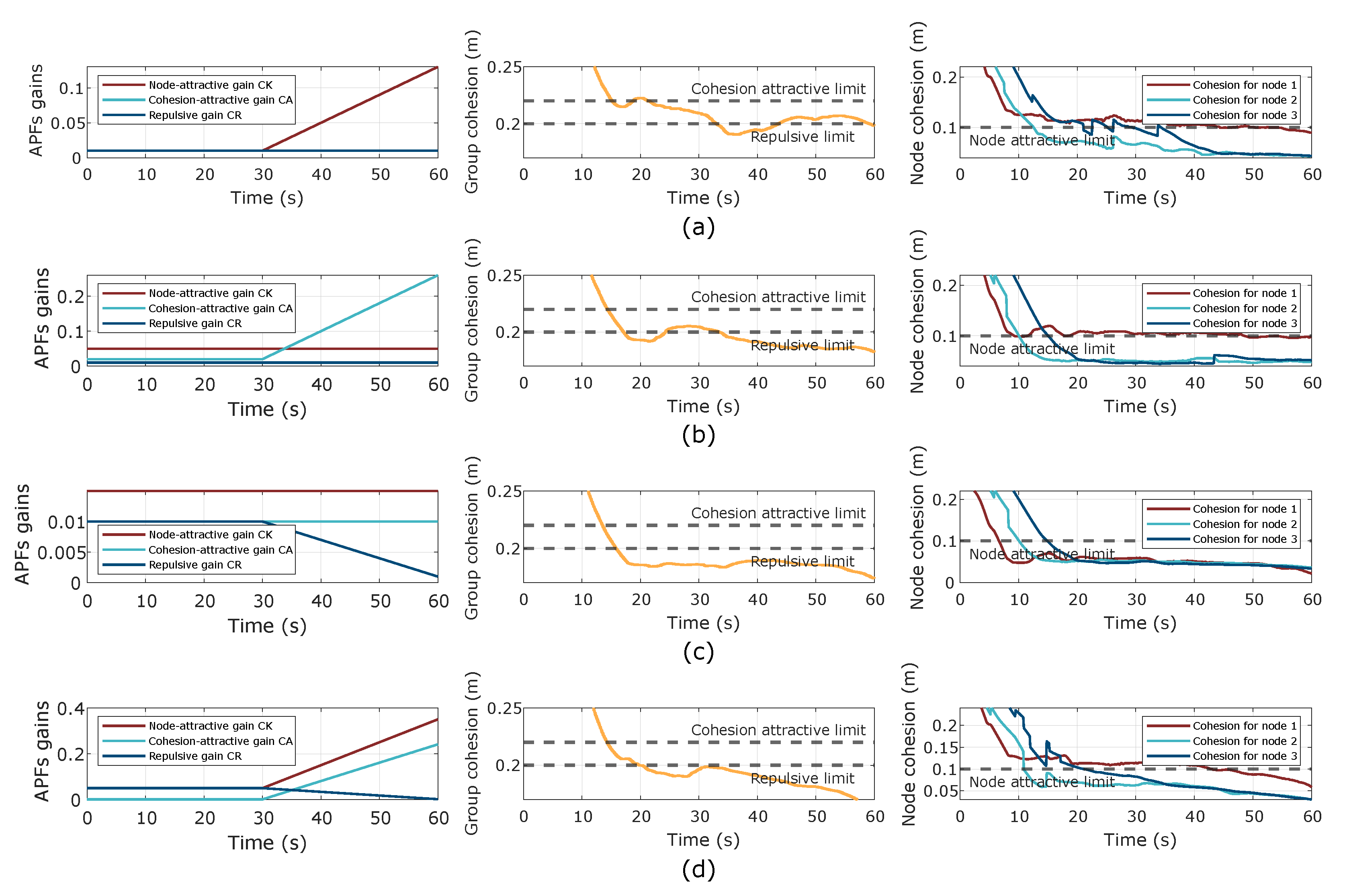

6.3. Tuning-Based Performance

7. Agriculture Tests

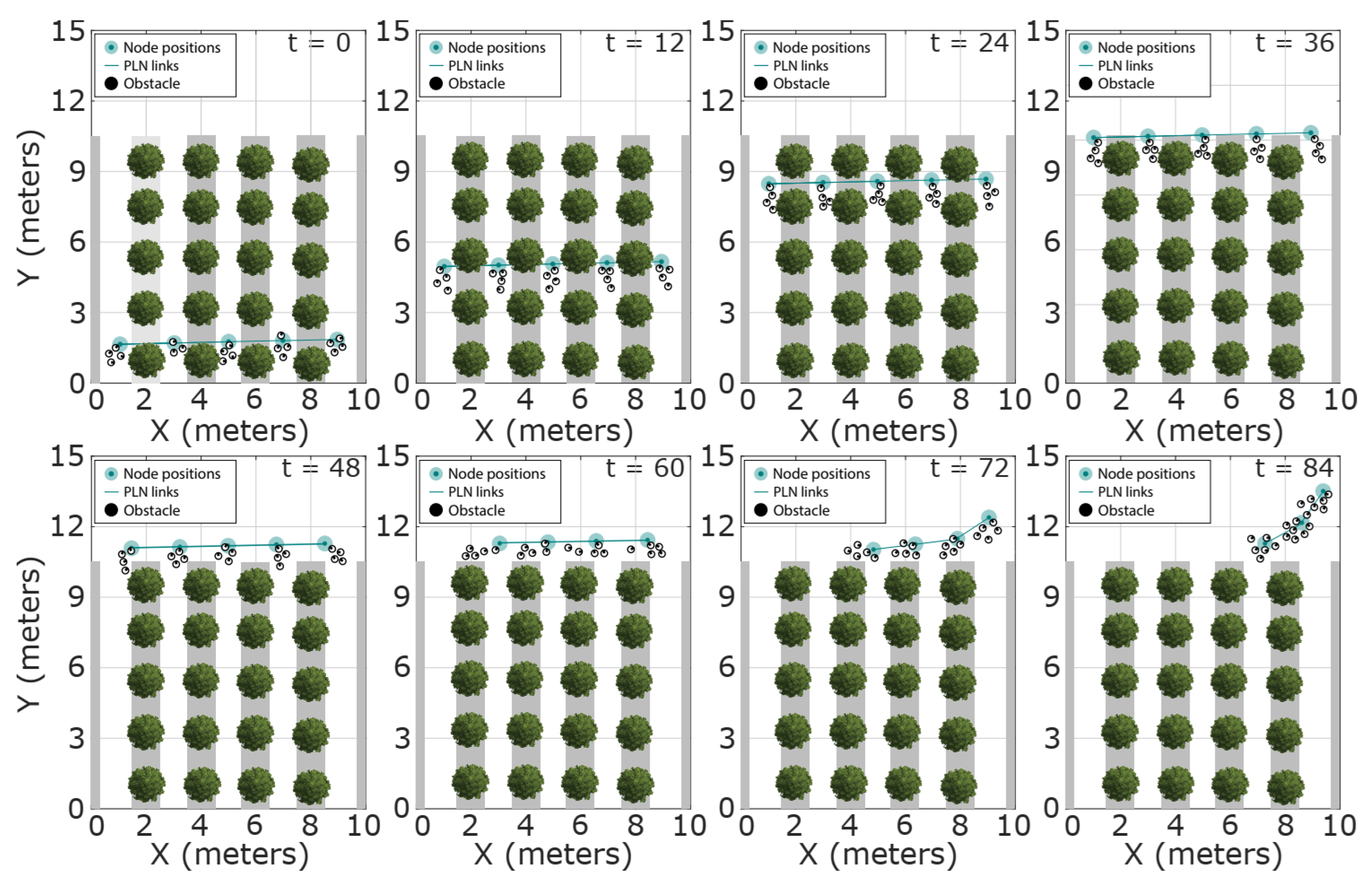

7.1. Swarm Formation Test in Crop Aisles

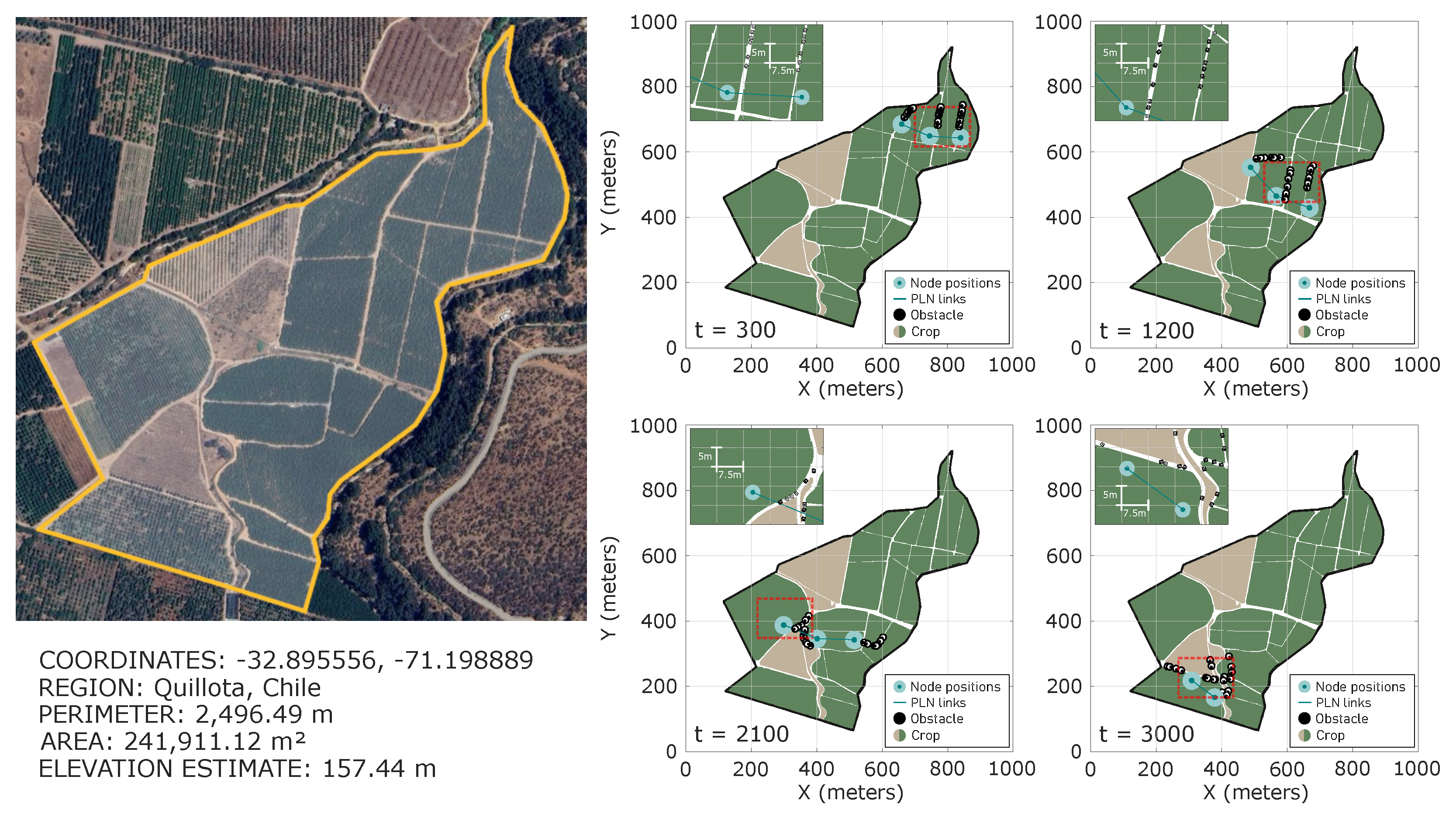

7.2. Swarm Formation Test in Crop Fields

8. Discussion

8.1. Theoretical Methodology Analysis

8.2. Agriculture Application Analysis

9. Conclusions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tan, Y.; yang Zheng, Z. Research Advance in Swarm Robotics. Defence Technology 2013, 9, 18–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Fu, Q.; Hong, M.; Tang, W.; Su, L.; Zhu, D.; Wang, Q. Optimization of Cotton Field Irrigation Scheduling Using the AquaCrop Model Assimilated with UAV Remote Sensing and Particle Swarm Optimization. Agriculture 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaeva, V.V. Self-organization in biological systems. 39, 110–118. [CrossRef]

- Vittori, K.; Talbot, G.; Gautrais, J.; Fourcassié, V.; Araújo, A.F.R.; Theraulaz, G. Path efficiency of ant foraging trails in an artificial network. 239, 507–515. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beshers, S.N.; Fewell, J.H. MODELS OF DIVISION OF LABOR IN SOCIAL INSECTS. Annual Review of Entomology 2001, 46, 413–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czirók, A.; Vicsek, T. Collective motion. In Proceedings of the Statistical Mechanics of Biocomplexity; Reguera, D., Vilar, J., RubÃ, J., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg; pp. 152–164.

- Deutsch, A.; Theraulaz, G.; Vicsek, T. Collective motion in biological systems. 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, E.; Turgut, A.E.; Dorigo, M.; Huepe, C. Collective motion dynamics of active solids and active crystals. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 095011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoufi, M.; Turgut, A.E.; Arvin, F. Self-organized Collective Motion with a Simulated Real Robot Swarm. In Proceedings of the Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems; Althoefer, K., Konstantinova, J., Zhang, K., Eds.; Cham; 2019; pp. 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Schranz, M.; Umlauft, M.; Sende, M.; Elmenreich, W. Swarm Robotic Behaviors and Current Applications. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, R.; Carey, K.; Abruzzo, B.; Korpela, C. What is A Robot Swarm: A Definition for Swarming Robotics. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 10th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics and Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON), 2019; pp. 0074–0081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.M.; Saeed, Z.; Akhtar, A.; Munawar, H.; Yousaf, M.H.; Baloach, N.K.; Hussain, F. A Review of Swarm Robotics in a NutShell. Drones 2023, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonyshyn, L.; Silveira, J.; Givigi, S.; Marshall, J. Multiple Mobile Robot Task and Motion Planning: A Survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, L.E.; Rus, D.; Sukhatme, G.S. Multiple Mobile Robot Systems. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Siciliano, B., Khatib, O., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 1335–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, A.E.; Çelikkanat, H.; Gökçe, F.; Åžahin, E. Self-organized flocking in mobile robot swarms; 2, 97–120. [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, E.; Turgut, A.E.; Huepe, C.; Stranieri, A.; Pinciroli, C.; Dorigo, M. Self-organized flocking with a mobile robot swarm: a novel motion control method. Adaptive Behavior 2012, 20, 460–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelikkanat, H.; Åžahin, E. Steering self-organized robot flocks through externally guided individuals. 19, 849–865. [CrossRef]

- Khaldi, B.; Cherif, F. A Virtual Viscoelastic Based Aggregation Model for Self-organization of Swarm Robots System. In Proceedings of the Towards Autonomous Robotic Systems; Alboul, L., Damian, D., Aitken, J.M., Eds.; Cham; 2016; pp. 202–213. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, V.G.; Pires, A.G.; Alitappeh, R.J.; Rezeck, P.A.F.; Pimenta, L.C.A.; Macharet, D.G.; Chaimowicz, L. Spatial segregative behaviors in robotic swarms using differential potentials. 14, 259–284. [CrossRef]

- Misir, O.; Gökrem, L. Flocking-Based Self-Organized Aggregation Behavior Method for Swarm Robotics. 45, 1427–1444. [CrossRef]

- Soza Mamani, K.M.; Richard Díaz Palacios, F. Flocking Model for Self-Organized Swarms. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Electronics, Communications and Computers (CONIELECOMP), 2019; pp. 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkilany, B.G.; Abouelsoud, A.A.; Fathelbab, A.M.R.; Ishii, H. A proposed decentralized formation control algorithm for robot swarm based on an optimized potential field method. 33, 487–499. [CrossRef]

- Soza Mamani, K.M.; Saavedra Alcoba, M. Low-Computational-Load Real-time Path Planning and Trajectory Control based on Artificial Potential Fields. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Colombian Caribbean Conference (C3), 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Artificial potential field algorithm for path control of unmanned ground vehicles formation in highway. Electronics Letters 2018, 54, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani, K.M.S.; Ordoñez, J. MIMC-VADOC Model for Autonomous Multi-robot Formation Control Applied to Differential Robots. In Proceedings of the 2022 8th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications (ICARA), 2022; pp. 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.M.J.A.; Lima, G.V.; Morais, A.S.; Oliveira-Lopes, L.C.; Ramos, D.C.; Tofoli, F.L. Modified Artificial Potential Field for the Path Planning of Aircraft Swarms in Three-Dimensional Environments. Sensors 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raibail, M.; Rahman, A.H.A.; AL-Anizy, G.J.; Nasrudin, M.F.; Nadzir, M.S.M.; Noraini, N.M.R.; Yee, T.S. Decentralized Multi-Robot Collision Avoidance: A Systematic Review from 2015 to 2021. Symmetry 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, H.; Abdollahi, F. Mobile robots cooperative control and obstacle avoidance using potential field. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE/ASME International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Mechatronics (AIM), 2011; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, H.; Abdollahi, F. A Decentralized Cooperative Control Scheme With Obstacle Avoidance for a Team of Mobile Robots. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2014, 61, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Fang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, K.; Liu, C.; Han, T. Obstacle Avoidance of Multi-Sensor Intelligent Robot Based on Road Sign Detection. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Cao, Z.; Pang, L.; Ren, L.; Zhou, C. A laser-based multi-robot collision avoidance approach in unknown environments. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2018, 15, 1729881418759107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Amin, A.A.; Lowenberg-DeBoer, J.; Franklin, K.; Dickin, E.; Monaghan, J.M.; Behrendt, K. Autonomous regenerative agriculture: Swarm robotics to change farm economics. Smart Agricultural Technology 2025, 11, 101005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkwocha, C.L.; Adewumi, A.; Folorunsho, S.O.; Eze, C.; Jjagwe, P.; Kemeshi, J.; Wang, N. A Comprehensive Review of Sensing, Control, and Networking in Agricultural Robots: From Perception to Coordination. Robotics 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrani, A.; Allouhi, A.; Bouarab, F.Z.; Jayachandran, K. AI and Robotics in Agriculture: A Systematic and Quantitative Review of Research Trends (2015–2025). Crops 2025, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albiero, D.; Pontin Garcia, A.; Kiyoshi Umezu, C.; Leme de Paulo, R. Swarm robots in mechanized agricultural operations: A review about challenges for research. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture 2022, 193, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.; Bai, Z.; Yi, K.; Qiu, B.; Dong, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, C.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X. Vision and 2D LiDAR Fusion-Based Navigation Line Extraction for Autonomous Agricultural Robots in Dense Pomegranate Orchards. Sensors 2025, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrea, C. Hybrid Fault-Tolerant Control in Cooperative Robotics: Advances in Resilience and Scalability. Actuators 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Xu, B.; Husnain, N.; Wang, Q. Overview of Agricultural Machinery Automation Technology for Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasouli, S.; Dautenhahn, K.; Nehaniv, C.L. Simulation of a Bio-Inspired Flocking-Based Aggregation Behaviour in Swarm Robotics. Biomimetics 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarapore, D.; Groß, R.; Zauner, K.P. Sparse Robot Swarms: Moving Swarms to Real-World Applications. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2020, 7–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botteghi, N.; Kamilaris, A.; Sinai, L.; Sirmacek, B. MULTI-AGENT PATH PLANNING OF ROBOTIC SWARMS IN AGRICULTURAL FIELDS. ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2020, V-1-2020, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, C.N.A.; Yumol, J.V.; Garcia, R.G.; Ballado, A.H. Swarm Robotics Application for Gathering Soil Samples. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 13th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management (HNICEM), 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postmes, J.; Botteghi, N.; Sirmacek, B.; Kamilaris, A. A System for Efficient Path Planning and Target Assignment for Robotic Swarms in Agriculture. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on the Internet of Things, New York, NY, USA, 2022; IoT ’21, pp. 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziomin, U.; Kabysh, A.; Golovko, V.; Stetter, R. A multi-agent reinforcement learning approach for the efficient control of mobile robot. Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE 7th International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems (IDAACS) 2013, Vol. 02, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blais, M.A.; Akhloufi, M.A. Reinforcement learning for swarm robotics: An overview of applications, algorithms and simulators. Cognitive Robotics 2023, 3, 226–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamani, K.M.S.; Camacho, O.; Prado, A. Deep Reinforcement Learning Via Nonlinear Model Predictive Control for Thermal Process with Variable Longtime Delay. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE ANDESCON 2024, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekhar, N.; Radhakrishnan, T.K.; Mohamed, S.N. Reinforcement learning based temperature control of a fermentation bioreactor for ethanol production. Place: United States 121, 3114–3127. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, P.; Bai, C.; Zheng, H.; Guo, J. Flocking Control of UAV Swarms with Deep Reinforcement Leaming Approach. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Unmanned Systems (ICUS), 2020; pp. 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Ni, K.; Jiang, X.; Kuroiwa, T.; Zhang, H.; Kawaguchi, T.; Hashimoto, S.; Jiang, W. Path following for Autonomous Ground Vehicle Using DDPG Algorithm: A Reinforcement Learning Approach. Applied Sciences 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, H.; Hua, M.; Wang, F.; Yi, J. P-DRL: A Framework for Multi-UAVs Dynamic Formation Control under Operational Uncertainty and Unknown Environment. Drones 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Tan, F.; Yu, M.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Z. A Bio-Inspired Sliding Mode Method for Autonomous Cooperative Formation Control of Underactuated USVs with Ocean Environment Disturbances. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzel, O.; Fleming, C.; Marcon, G.H. Learning Flocking Control in an Artificial Swarm. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, F.; Montiel, H.; Wanumen, L. A deep reinforcement learning strategy for autonomous robot flocking. International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering (IJECE) 2023, 13, 5707–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezcioglu, M.B.; Lennox, B.; Arvin, F. Self-Organised Swarm Flocking with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 7th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications (ICARA), 2021; pp. 226–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Zheng, B. Non-Communication Decentralized Multi-Robot Collision Avoidance in Grid Map Workspace with Double Deep Q-Network. Sensors 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.; Niu, H.; Lennox, B.; Arvin, F. Bio-Inspired Collision Avoidance in Swarm Systems via Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2022, 71, 2511–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Chen, H.; Liu, B. Path Planning of Agricultural Information Collection Robot Integrating Ant Colony Algorithm and Particle Swarm Algorithm. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 50821–50833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Oğuz, S.; Wang, S.; Garone, E.; Wang, X.; Dorigo, M.; Heinrich, M.K. Self-Reconfigurable Hierarchical Frameworks for Formation Control of Robot Swarms. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2024, 54, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Oğuz, S.; Heinrich, M.K.; Allwright, M.; Wahby, M.; Christensen, A.L.; Garone, E.; Dorigo, M. Self-organizing nervous systems for robot swarms. Science Robotics 2024, 9, eadl5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Qi, L.; Yuan, H.; Guo, X.; Zhao, M.; Liu, Z.; Yang, T. Path Planning Method With Improved Artificial Potential Field—A Reinforcement Learning Perspective. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 135513–135523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wu, D.; Huang, Y.; Yuan, Z.M. A path planning strategy unified with a COLREGS collision avoidance function based on deep reinforcement learning and artificial potential field. Applied Ocean Research 2021, 113, 102759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouyan, S.; Campo, A.; Dorigo, M. Path formation in a robot swarm. 2, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Bautista, J.; de Marina, H.G. Behavioral-based circular formation control for robot swarms. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2024; pp. 8989–8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.; Chong, N.Y.; Christensen, H. Adaptive triangular mesh generation of self-configuring robot swarms. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2009; pp. 2737–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, A.R.; Jin, Y. A Strategy for Self-Organized Coordinated Motion of a Swarm of Minimalist Robots. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2017, 1, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, V.; Guttal, V.; Masila, D.R. Randomness in the choice of neighbours promotes cohesion in mobile animal groups. Royal Society Open Science 2022, 9, 220124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.K. Distributed cohesive configuration controller for a swarm with low-cost platforms. Journal of Field Robotics 2023, 40, 30–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yigit, B.; Alapan, Y.; Sitti, M. Cohesive self-organization of mobile microrobotic swarms. Soft Matter 2020, 16, 1996–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatib, O. Real-time obstacle avoidance for manipulators and mobile robots. In Proceedings of the Proceedings. 1985 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation 1985, Vol. 2, 500–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, M.H.; McInnes, C.R. Wall following to escape local minima for swarms of agents using internal states and emergent behaviour. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Intelligent Systems, ICCIIS 08, 2008; International Association of Engineers; pp. 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Park, S.; Lee, W.; Kim, W.; Choi, H.; Doh, N.; Nam, C. Escaping Local Minima: Hybrid Artificial Potential Field with Wall-Follower for Decentralized Multi-Robot Navigation. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2025; pp. 6616–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singletary, A.; Klingebiel, K.; Bourne, J.; Browning, A.; Tokumaru, P.; Ames, A. Comparative Analysis of Control Barrier Functions and Artificial Potential Fields for Obstacle Avoidance. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2021; pp. 8129–8136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchiorre, M.; Salamina, L.; Scimmi, L.S.; Mauro, S.; Pastorelli, S. Experiments on the Artificial Potential Field with Local Attractors for Mobile Robot Navigation. Robotics 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, R.O.; Hart, P.E.; et al. Pattern classification; John Wiley & Sons, 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Parameter | Aggregation test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | ||

| Cohesiveness | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.008 | |

| [meters] | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| [meters] | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.27 | |

| 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| [meters] | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.25 | |

| Formation | [meters] | 2 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.4 |

| 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||

| [radians] | 0.78 | 2.35 | 3.92 | 3.92 | |

| [radians] | 4.71 | 3.14 | 2.35 | 2.35 | |

| [meters/second] | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| [radians/second] | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Category | Parameter | Flocking test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | (b) | (c) | (d) | ||

| Cohesiveness | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | |

| [meters] | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |

| 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | ||

| [meters] | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.22 | |

| 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | ||

| [meters] | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| Formation | [meters] | 2.4 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.4 |

| 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | ||

| [radians] | 0.78 | 2.35 | |||

| [radians] | 3.14 | 1.25 | 1.04 | 3.14 | |

| [meters/second] | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.02 | |

| [radians/second] | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0005 | 0.0002 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).