1. Introduction

Disaster Management (DM) and Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) are cases of complex System of Systems (SoS), which consist of many elements (sub-systems) and are affected by numerous external and internal factors. For this reason, their development needs to be planned with strong consideration for the synchronisation of their components’ development and long-term perspective, including guiding social, economic, and environmental factors. This is the reason why strategic foresight is going to be utilised as the research method in this paper. It allows for structured exploration of different possible development scenarios, alongside the opportunities and challenges they might tackle, and with that to assist in decision and policy making [

1]. Strategic foresight is a highly flexible format which is able to capture as many challenges and opportunities as possible, which in turn enables interdisciplinary solution creation and development. This is ideal for the topic of this paper, as DM and AAM are highly interdisciplinary – involving various social and engineering sciences.

DM is the discipline for the organisation, planning, development, and application of measures for the preparation, response, and recovery from disasters which vary in characteristics [

2]. The variety of disasters impacting Europe and neighbouring regions, including natural (e.g., earthquakes, volcanoes, hurricanes, floods, wildfires), and human-made (e.g., wars, terrorist attacks, pollution, nuclear explosions and radiation, fires, hazardous materials exposures, explosions, transportation accidents, industrial accidents) [

3], necessitates sophisticated DM frameworks. Each disaster type requires a unique set of technologies and protocols to ensure a timely, coordinated response. Thus, DM is a complex SoS, which involves emergency response services (first responders), their operators and vehicles, hospitals, communication and coordination systems, monitoring systems, weather forecasting, policy and decision making entities, etc. In addition to DM, the term of Public Protection and Disaster Relief (PPDR) is also used in public circulation, including in documents of international organisations. The former should be interpreted as a framework for a strategic and systematic approach, while the latter is the on-the-ground execution of some public safety and disaster-related strategies defined by the former, carried out by law enforcement, fire, and other emergency services, including routine activities, handling planned events, and response to disaster situations.

Heritage preservation is also a crucial aspect of DM by safeguarding cultural continuity, social identity, and historical knowledge, thus enabling communities to retain resilience and collective memory during and after catastrophic events, from tangible heritage, e.g., historic buildings, monuments, entire historic and protected architectural landscapes, etc. Unmanned Aircraft System (UAS) and respectively AAM represent decisive technological enablers of sustainable heritage protection: Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) facilitate rapid, high-resolution, and safe documentation of fragile or inaccessible heritage sites, enabling accurate mapping, condition assessment, and 3D modelling even under hazardous conditions [

4]. AAM – including electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing aircrafts (eVTOLs) and other next generation aerial platforms – extends this capability by offering scalable, efficient, and potentially routine operations that can deliver supplies, personnel, or sensors to and from heritage areas quickly and with greater flexibility [

5]. However, the effectiveness of both UAS and respectively AAM relies fundamentally on Advanced Communication System (ACS): resilient aerial-based networks, e.g., UAV-enabled Flying Ad-Hoc Networks or even High Altitude Platforms (HAPs), can provide ultra-reliable, low-latency connectivity essential for coordinating real-time data transmission, drone swarming, and control – all critical for time-sensitive heritage protection [

6]. In sum, combining heritage preservation with UAS/AAM technologies and robust communication infrastructures offers a powerful, sustainable solution for proactive and reactive DM strategies, and specifically the cultural heritage preservation.

To combine DM, AAM, and ACS in a cohesive way, a SoS approach is needed for the development, implementation, and utilisation of sustainable methods and operations, based on these disciplines. By definition, a SoS is a collection of independent systems, integrated into a larger system that delivers unique capabilities, and these systems collaborate to produce a global behaviour which they cannot produce by themselves [

7]. For DM, there are: the separate emergency services, the sensing stations for various natural forces, the various decision-making agencies, volunteers, hospitals, logistical and transportation networks, air traffic control, critical infrastructure sites, military units, etc. Alongside, there are the AAM and ACS domains and their systems: operators, UASs, logistical hubs, data centres, communication systems, etc.

AAM describes aerial systems that provide services in novel ways and in underutilised sectors or in fields that can benefit tremendously from the usage of aircraft for the achievement of their objectives. When talking about AAM this usually refers to the usage of smaller air vehicles or UAS compared to traditional aircraft such as aeroplanes and helicopters. In addition to that, UAVs are built with autonomy in mind or simply without the need of a human to be present on board. The reason behind this is the fact that AAM is aimed towards servicing stakeholders and places, for example: in DM that require vast fleets of aircraft which need to be small, light and safe in order to fulfil their role and obligations towards the communities they serve. Naturally, depending on the use case, the parameters and characteristics of an UAS can vary drastically, however, this paints a simple picture of what AAM is. On top of that, depending on the type of the aircraft and its mission, such systems can serve both stakeholders in the same region or in vastly different regions that are hundreds of kilometres apart. In short, the benefits of AAM and UAS can be summed up in their flexibility, the amount and type of needed infrastructure, logistics, sustainability, decentralisation, new markets and jobs, efficiency coupled with renewable energy, and a vast array of possible use cases.

The goal of this foresight paper is to present a clear path towards sustainable disaster and emergency situations management, including situational awareness and urgent high added value goods deliveries, greatly enabled by AAM, which finally is to be enabled to operate in the most sustainable and safe form by ACS. This includes the definition of the possible necessities, development paths, and education needed to achieve such a cohesive SoS. The main focus is on ACS, since efficient communication and coordination, enabled by novel digital technologies, will unlock new valuable capabilities and will allow for the efficient and effective use of all available resources at any given moment. For example, bottlenecks caused by inefficient or distorted communication along the decision making chain, could allow for faster reaction times in critical situations and moments, resulting in better outcomes.

Thus, this paper will investigate the opportunities for ACS, including different novel technologies, operational and communication architectures, and expected benefits. The foresight will also present the identified challenges for the establishment of such a SoS in the context of DM and expected challenges during operation. Lastly, the paper will present what the next steps should be to overcome the identified challenges and will outline the foreseen development paths and future work in a clear manner.

The main sources of information for this paper are the results from several relevant projects where the authors were involved. These are: SUDEM, REGUAS, 5G!Drones, and ETHER. These projects are all relevant for the domains of DM, AAM (enabling a significant part of DM), and ACS (a crucial enabler for safe AAM operations), and their goals and results are presented in the Materials and Methods section. Of course, multiple external relevant references and studies have been considered. The Results section outlines the key takeaways, which are relevant for achieving the goals of this strategic foresight and presents the ACS development prospects relevant for AAM-supported DM. In the Discussion section, the authors outline the challenges for implementation of the presented vision – so far observed obstacles and possible approaches to enhance the process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Evaluation and Principles of the DM Framework

To evaluate efficiency and effectiveness in DM, it is essential to establish criteria for qualifying, comparing, and selecting the best-performing alternatives. In the literature, Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) are widely used as metrics to assess an organisation’s progress toward defined goals and for the improvement of operational quality. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of substantial work on the definition and application of KPIs specifically for emergency and DM.

In [

8], 14 KPIs are proposed, grouped into three main categories: throughput, time performance, and supply and demand performance. The first one, Throughput, measures the number of elements that are processed by the system per unit of time. The kind of the element depends on the process and throughput can be calculated for various kinds. Next, Time Performance, refers to the processing of emergency conditions and is considered important since delays may lead to increased damages and casualties. It relates to the timeliness of handling emergency conditions. Lastly, Supply and Demand Performance, where supply refers to the set of resources which are necessary for the execution and completion of DM tasks. For example, if supply is sufficient for the demand then emergency conditions can be handled without unnecessary delays.

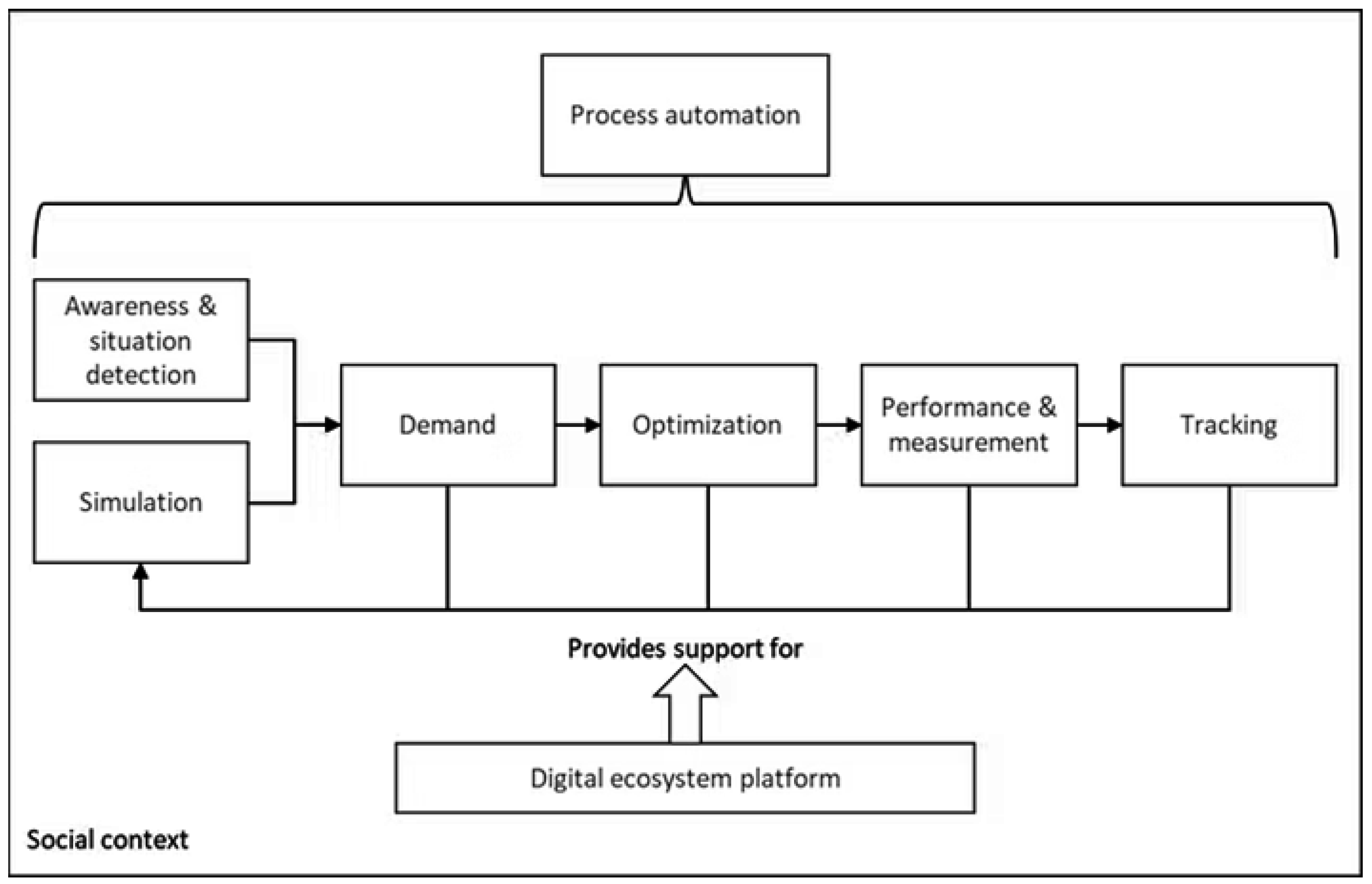

DM operations supported by digital technologies (including Artificial Intelligence (AI), UAVs etc.) could be structured according to the ADOPT principles, which encapsulate six interrelated functions, as presented in

Figure 1:

Awareness and Situation Detection: Focuses on the timely and accurate detection of disaster effects, including infrastructure damage, environmental hazards, and the condition of humans and other living beings.

Demand Generation: Based on real-time assessments of damage and environmental conditions, demand lists for required resources are automatically generated. These may include rescue teams, firefighting units, ambulances, security personnel, repair crews, temporary shelters, evacuation vehicles, heating and cooking equipment, food, water, and other essentials.

Optimisation of Resource Allocation: Available resources are allocated to identified demands in an optimal and timely manner. When resources are insufficient, prioritisation, trade-off analysis, and dynamic selection techniques are employed to ensure the best possible outcomes under constraints.

Performance and Measurement: With the help of a digital twin architecture, KPIs are formally defined to specify and evaluate operational objectives. Real-time monitoring allows for the detection of performance deviations, enabling corrective actions to be taken promptly.

Tracking and Task Forces: With the help of a digital twin architecture, the continuous monitoring, evaluation, and control of ongoing activities, as well as the coordination among diverse aid operations to maintain coherence and avoid resource conflicts are handled.

Simulation: Simulation environments are essential for assessing the effectiveness and efficiency of the disaster and emergency ecosystem across a wide range of hypothetical disaster scenarios. These simulations support the estimation of required resource quantities, optimisation of logistics centre locations, and overall preparedness. Even in the absence of real disasters, the ecosystem platform should remain operational, driven by synthetic scenarios to facilitate continuous improvement via online machine learning techniques.

For effective and efficient DM operations, during and after a disaster, emergency decision making entities must determine the effect of disasters precisely and in a timely manner. Different kinds of techniques and technologies, including different sources, can be used to collect data from disaster areas, such as sensors, cameras, and UAVs, in order to enhance situational awareness. For this purpose, AAM and ACS developments can provide new opportunities. However, due to the challenges related to the topological complexities of affected disaster areas, and the number and variability of available data sources – a model-based analysis and synthesis framework has been used in paper [

10] to determine the optimal data fusion set, before expensive implementation and installation activities are carried out.

For resource-efficient DM, the following work steps and domains are crucial, respectively these shall be optimally covered by digital tools for their optimisation, and all of these need AAM as their crucial pillar:

Monitoring;

Irregular events detection;

Preparedness assurance;

Alert;

Reaction plan preparation;

Decision making support;

Emergency preparation and planning;

Emergency coordination;

Post-disaster recovery;

Preparedness assurance after the event, based on the lessons learnt.

2.2. International Standardisation of ACS

The ACS subsystem is a key enabler of AAM SoS. While in the past (especially before the proliferation of UAS) aviation used separate and specific dedicated communication systems, the industry is currently evolving towards the use of communication systems using universal information and communication technologies, derived from the Internet technology. The mobile network based on 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) specifications, which is widely used in everyday life and in various professional industries worldwide, is seen as an attractive universal wireless communication platform providing a unified technology of Radio Access Network (RAN) and a multitude of functionalities that are able to meet the specific needs and requirements of various industries, including AAM. The evolution of mobile networks has been ongoing for decades. Its development has seen milestones, including digitalisation (1990s), the gradual introduction of packet data transmission services with increasingly high transmission speeds (2000s), and finally the implementation of the “All IP” principle, i.e., the concept of a network providing a universal access in IP technology, on the basis of which all other services are implemented (2010s). However, with the achievement of 5th Generation (5G), the mobile network is based on several paradigms of groundbreaking importance for its support of unmanned aviation and AAM:

Softwarisation – moving away from implementing network elements in dedicated function-specific hardware towards implementing network architecture using software running on commodity generic Information Technology (IT) hardware (decoupling of function and hardware); in this way, network mechanisms and features can be flexibly adapted to changing needs.

Virtualisation – instead of hardware dedicated to specific software instances, the softwarised network is running on virtualised hardware, which provides seamless scaling of resources and migration of running software between underlying resources, and maintenance/extension of resources imperceptible to the software [

11]. The communications industry moves towards “telco cloud” – a mesh of microservices that can work across different cloud environments (private, public, and hybrid) [

12].

Network slicing – moving away from the hitherto approach of unified network architecture (both for control mechanisms and user data processing) for all application scenarios and related services with sometimes extremely different requirements towards providing virtually isolated networks having architectures and behaviours tailored to the individual specificity of the supported use cases and their tenants.

Network capabilities exposure – the network Control Plane (CP) exposes the mechanisms and functionalities of mobile network control and the data available there to higher-layer systems, e.g., IT ecosystems of “vertical industries” (e.g., manufacturing, automotive, aviation, healthcare, public safety, etc.). In this way, the vertical industry ecosystem can interact with the mobile network, e.g., acquire data on the location of the user device, request a higher priority for its service, increase quality parameters or specific processing of a certain fraction of its traffic, etc.

The general vision of the 5G System (5GS), i.e., IMT-2020 – the mobile system for 2020s, has been defined by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) [

13,

14] and includes three usage scenarios: Enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB) – emphasis on transmission speed, Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communication (URLLC) – emphasis on reliability and Massive Machine Type Communications (MMTC) – emphasis on high density of connected network devices. The performance requirements include:

peak data rate 20 Gb/s and

user-experienced data rate 100 Mb/s both in urban and sub-urban areas, at the

latency (in RAN) 1 ms; connection density 10

6 devices per km

2 and area traffic capacity 10 Mb/s per m

2;

mobility of users up to 500 km/h;

reliability for urban URLLC 99,999%. The vision also acknowledges the demand for location-based service applications, e.g., emergency rescue services, precise ground-based navigation service for unmanned vehicles or drones.

The technical design of 5GS is developed and standardised by 3GPP in the approach that starts from the definition of service requirements: general ones (e.g., network slicing, capacity exposure, or positioning) [

15] and unmanned aviation-specific ones, including recognition of non-payload, i.e., Command and Control (C2) and UAV to Unmanned Aircraft Systems Traffic Management (UTM) communication, in addition to payload (UAV flight purpose-oriented) one, integration with UTM and its assistance by the mobile network, identification and tracking of UAV network devices, UAV safety, flight path and zone restriction management [

16]. In the next step, 3GPP defines the architecture and system procedures of 5G that provide the several features with premium importance for support of UAS [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22], which are discussed below:

Network slice selection, admission control, and slice-specific authentication/authorisation are mechanisms crucial for isolation of connectivity dedicated for UAVs with Quality of Service (QoS) guarantee and joint authorisation of UAV network devices by mobile network and UTM. 5GS supports simultaneous connection of network device to multiple different network slices. In addition to the 3 above mentioned basic usage scenarios defined by ITU (eMBB, URLLC, and MMTC), 5GS currently distinguishes also 4 additional slice service types: Vehicle to Everything (V2X), High-Performance Machine-Type Communications (HMTC), High Data rate and Low Latency Communications (HDLLC), and Guaranteed Bit Rate Streaming Service (GBRSS) that emphasise various sets of QoS parameters. The User Plane (UP) traffic processing chain design of a network slice can be freely adapted to specific payload and non-payload communication requirements.

QoS model based on QoS Flows, which guarantee differentiated End-to-End (E2E) traffic fractions’ parameters within the individual, per network slice, network terminal session. Both Guaranteed Bit Rate (GBR) flows and Non-GBR ones are supported; for the former ones, guaranteed/maximum bitrates and maximum packet loss rates can be defined separately for uplink and downlink. 3GPP has defined more than 30 default classes of flows relevant to requirements of various types of communication applications, both for Non-GBR, GBR, delay-critical GBR flow types, providing their priority levels, packet delay budgets and error rates, etc. In order to enable high-demand real-time URLLC applications, 5GS provides specific mechanisms supporting such concepts like Time-Sensitive Networking (TSN), time-sensitive communications, time synchronisation and deterministic networking.

Network CP exposure includes mechanisms of Network Exposure Function (NEF) – a generic interface for CP integration with external systems, e.g., those of vertical industries – and Application Function (AF) – an agent or “embassy” of the external system embedded within the mobile network CP; these are further extended with the specifications of Common Application Programming Interface (API) Framework for 3GPP Northbound APIs (CAPIF) [

23] and Service Enabler Architecture Layer for Verticals (SEAL) [

24].

Location Services framework supports aerial network device localisation mechanisms independent from Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), which can, e.g., be used for validation of position reported by UAVs to UTM.

Dual connectivity (simultaneous connection of network device to different RAN nodes) and redundant UP path are crucial for high reliability of services required by air traffic safety. These support redundancy of traffic, while virtualisaton, hardware, and transport network layers can provide their redundancy and reliability mechanisms.

Proximity-based services, ranging-based services and sidelink positioning are based on direct connection between network devices (also those registered in different mobile networks) at distances of hundred meters [

25] for connectivity sharing, mutual distance determination, and positioning.

Specific support for UAS includes joint authentication and authorisation of a UAV with UTM for mobile network/services access; UAV tracking, presence monitoring and listing of aerial devices in a geographic area; direct controller-UAV C2 communication; support for geofencing/geocaging, detect and avoid mechanism, UAV pre-mission flight planning and in-mission flight monitoring, including early warning of communication loss risk.

Support of integration with edge computing, e.g., commonly recognised European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) framework [

26] serves for implementation at the edge of applications demanding very low latency, e.g., UAV controller, First Person View First Person View (FPV) for the remote pilot, or situational awareness processing of video stream from UAV, etc.

The 3GPP’s efforts are complemented by activities of other industry associations. Global System for Mobile Communications Alliance (GSMA)develops Generic Network Slice Template specification including definition of various slice template attributes reflecting possible requirements in potential service use scenarios and standardised sets of attributes for defined service use scenarios [

27] – this way, interoperability will be provided in both national and international roaming scenarios (for entire national coverage provided jointly by multiple mobile networks and for cross-border aerial operations or operations outside of country of registration). Within the framework of The Linux Foundation, CAMARA project [

28] aims at common definition of service enablement platform, specifies service APIs, transforming exposed low-level network capabilities into high-level abstraction for defined types of services. ETSI runs industry specification groups on Zero-touch network & Service Management [

29] and Experiential Network Intelligence [

30] to support full E2E network and services management automation facing expected explosion of future networks complexity and number of coexisting networks, including cognitive, context- and situation aware approach to changes in user needs. A common project of unmanned aviation and mobile telecommunications industries, Aerial Connectivity Joint Activity group published several reports concerning mobile network mechanisms, network coverage data exchange, and method of C2 link performance assessment to facilitate cooperation of UTM and mobile network ecosystems [

31].

2.3. Research Projects

2.3.1. SUDEM

The ERASMUS+ KA220 project, SUDEM (Sustainable Disaster and Emergency Management Processes Digitalisation), is establishing and validating a novel interdisciplinary higher education knowledge transfer model and curriculum, with focus on the digitalisation of the overall disaster and emergency handling lifecycle. The international team embeds principles of practice and education from all relevant domains, including risk and disaster monitoring and management, decision making support, disaster handling management, AI, Internet of Things (IoT), Data Science, remote sensing (satellites and drones), data fusion, and data management.

SUDEM seeks to prepare students with the skills required to address the efficient management of relevant extreme events’ and disasters’ consequences, and improve the emergency processes. The overarching goal is Europe to create a pool of DM experts with an adequately intensive focus on digital tools, through which the disaster-caused life and infrastructure losses to significantly decrease in the long-term perspective.

The project unites a consortium of leading European Higher Education and Research organisations, leveraging international collaboration to align academic programs with the demands of the optimal DM, including the decision making support. SUDEM emphasises creating adaptable and accessible educational modules that can be implemented across diverse Higher Education and Life-Long Learning organisations.

A crucial component of SUDEM is the developed Foresight study – a core project methodology element, which presents identified demands, challenges, and solutions. It enables the elaboration and delivery of a relevant system architecture, and an optimal future development scenario, including a higher education framework on DM process management, policy recommendations, and finally – a unique knowledge and training package – all as core results of the SUDEM project.

2.3.2. REGUAS

The aim of the REGUAS joint project was to investigate how the supply of rural areas with high added value (and urgent) goods could be optimised in a regional context using UASs. The North-East Hesse region, and more specifically the Bebra municipality, was selected for the project. The aim was to define and test the extent to which individualised goods deliveries can be mapped in such a way that emission reduction and delivery time targets, the expectations of citizens with regard to supply security and speed, and fail-safe transport alternatives are taken into account.

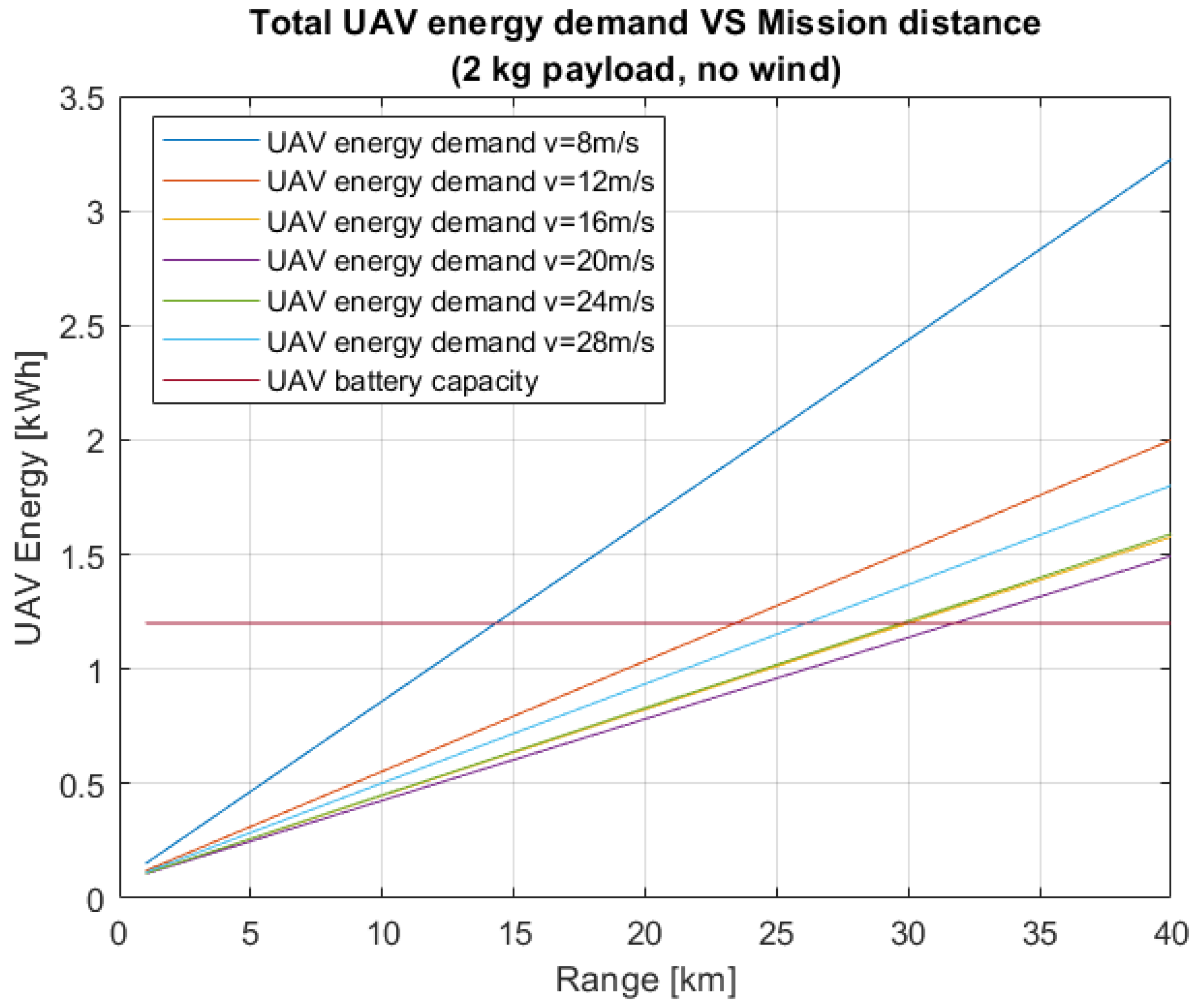

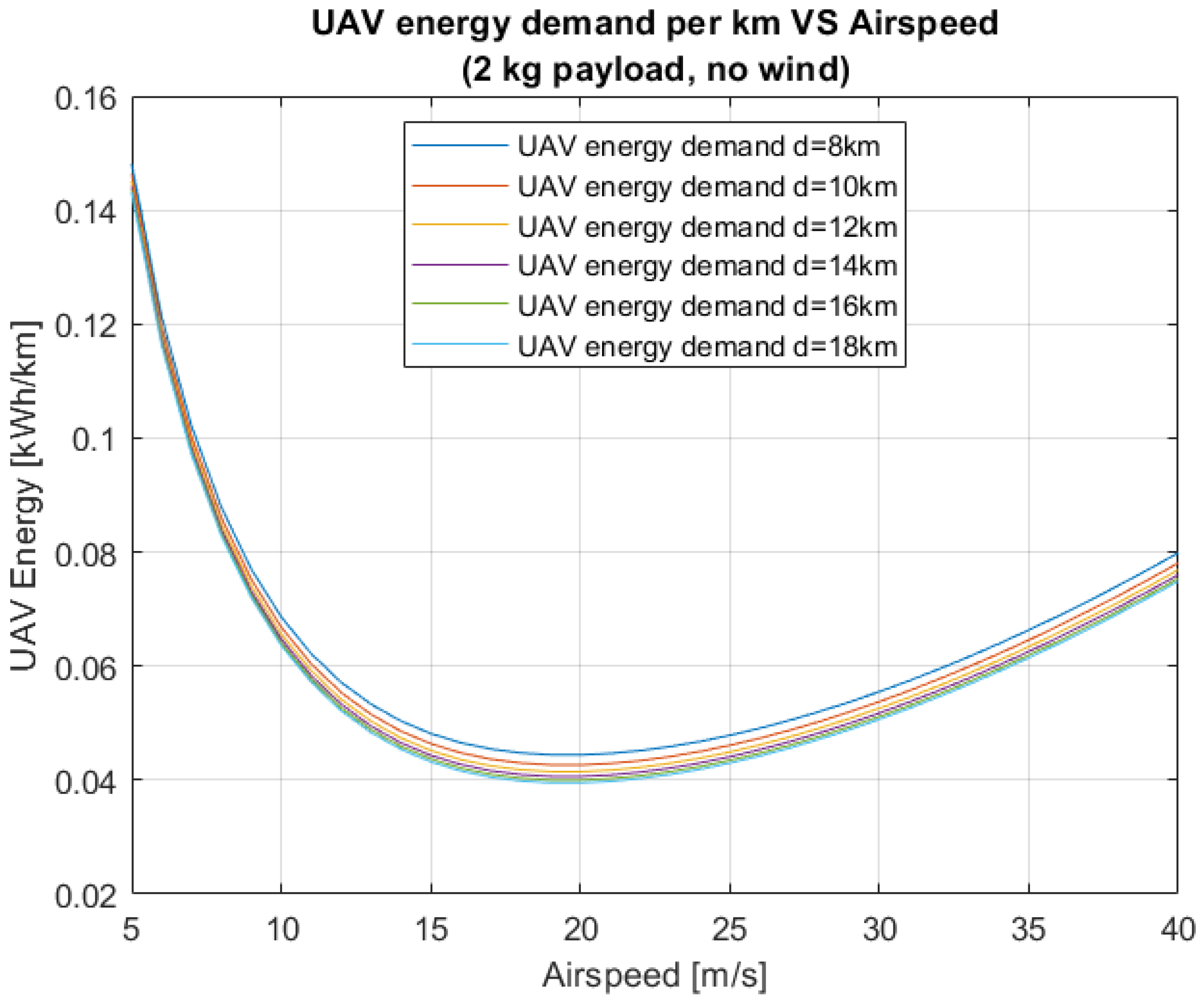

Focus was placed on the goal to assess the feasibility of rural UAS logistics for high added value goods, with emphasis on multirotor UAS. The used method was through simple flight simulation and then practical validation tests. The simulation was conducted by creating an energy model for multirotor drones in MATLAB. The calculated characteristics were: the optimal flight speeds, the energy required for different scenarios, and the operational sustainability in terms of CO2 emissions produced by the generation of energy required for charging of the batteries. The required energy and optimal flight speed were calculated by the developed MATLAB estimation tool, which provided valuable information for the expected multirotor energy performance.

Considering a round trip between Bebra and Solz (a village in the municipality) of approximately 16 km, the airborne part of the proposed REGUAS UAS delivery system was concluded to be technically feasible with enough operational flexibility due to the amount of estimated energy required, especially at the optimal velocity. It appeared that medium-sized multirotor UAVs can perform reasonably well at medium ranges and in remote areas with the added benefit of being able to carry payloads of useful sizes and weights. Results from the energy calculation model for the REGUAS project can be viewed on

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

If single high value added packages are to be considered, especially in more remote regions, then UAS provide considerable value compared to road vehicles. However, this is valid only for high added value goods, single packages, remote regions, if the roads have many turns, and if the package needs to be delivered quickly.

2.3.3. 5G!Drones and ALADIN – UAS with 5G Connectivity

The issue of mobile network support for the UAS ecosystem is an important element of numerous research projects, including the Horizon programme projects sponsored by the European Commission. Among them, the 5G!Drones [

32] project is worth mentioning, which had the goal of trialling several UAV use-cases covering various 5G services. The project’s main focus was running UAV vertical use cases on top of 5G facilities. The objectives were: (i) to validate 5G KPIs; and (ii) to evaluate and validate the performance of different UAV vertical applications. The project demonstrated the integration of the mobile network management and orchestration layer with UTM and C2 systems as well as the payload communication in various AAM-relevant use cases concerning goods delivery, public safety/saving lives (e.g., wildfires, search and rescue operations), situational awareness (including: remote inspection, location services without satellite-based positioning – indoors, in tunnels, etc.), and UAV as an occasional Base Station (BS) in extraordinary cases. During its life cycle, the 5G!Drones project actively contributed to the activities of the ITU, 3GPP and ACJA, as well as associations and standards developing bodies of the UAS industry. The project results have been further developed and commercialised in the form of 5G cellular drones teleoperated at a distance of up to 100 km or performing autonomous logistics tasks, as well as tethered drones acting as occasional 5G BSs or broadcasting/jamming nodes [

33].

The national German project ALADIN dedicated to advanced low altitude data information system for disaster relief has showcased how a nomadic local 5G network installed in a van can be used in forest firefighting, providing connectivity for unmanned firefighting vehicles control and for reconnaissance drones used to giving a situational awareness to the operations centre and individual terminals of firefighters. In this way, it is possible not only to ensure communication in forest areas where the quality of mobile services is usually low but also enable disaster relief in areas restricted to enter or drive through (e.g., burning toxic or explosive materials or areas contaminated with unexploded shells and ammunition parts lying in the ground) [

34].

2.3.4. ETHER and Other Projects on Satellite-Based Connectivity for UAS Provided by 5G and Beyond 5G Technologies

Extending 5G network coverage beyond metropolitan areas is key to “urbanising” rural and remote areas, which are currently “white spots” for AAM. Given the economic impossibility of achieving this using a Terrestrial Network (TN), plans are underway to integrate access via Non-Terrestrial Network (NTN) with TN to secure ubiquitous connectivity – using Low Earth Orbit (LEO), Medium Earth Orbit (MEO), or Geostationary Earth Orbit (GEO) satellites and Low Altitude Platforms (LAPs)/HAPs. In the case of LAP, especially in disaster relief circumstances, the carriers may be UAVs creating a communication mesh using direct connections or, in tethered mode, supplied from the ground with the connectivity to the IP data network, e.g., the Internet. Two current active Horizon Europe research projects discussed below will soon present demonstrations in this application area.

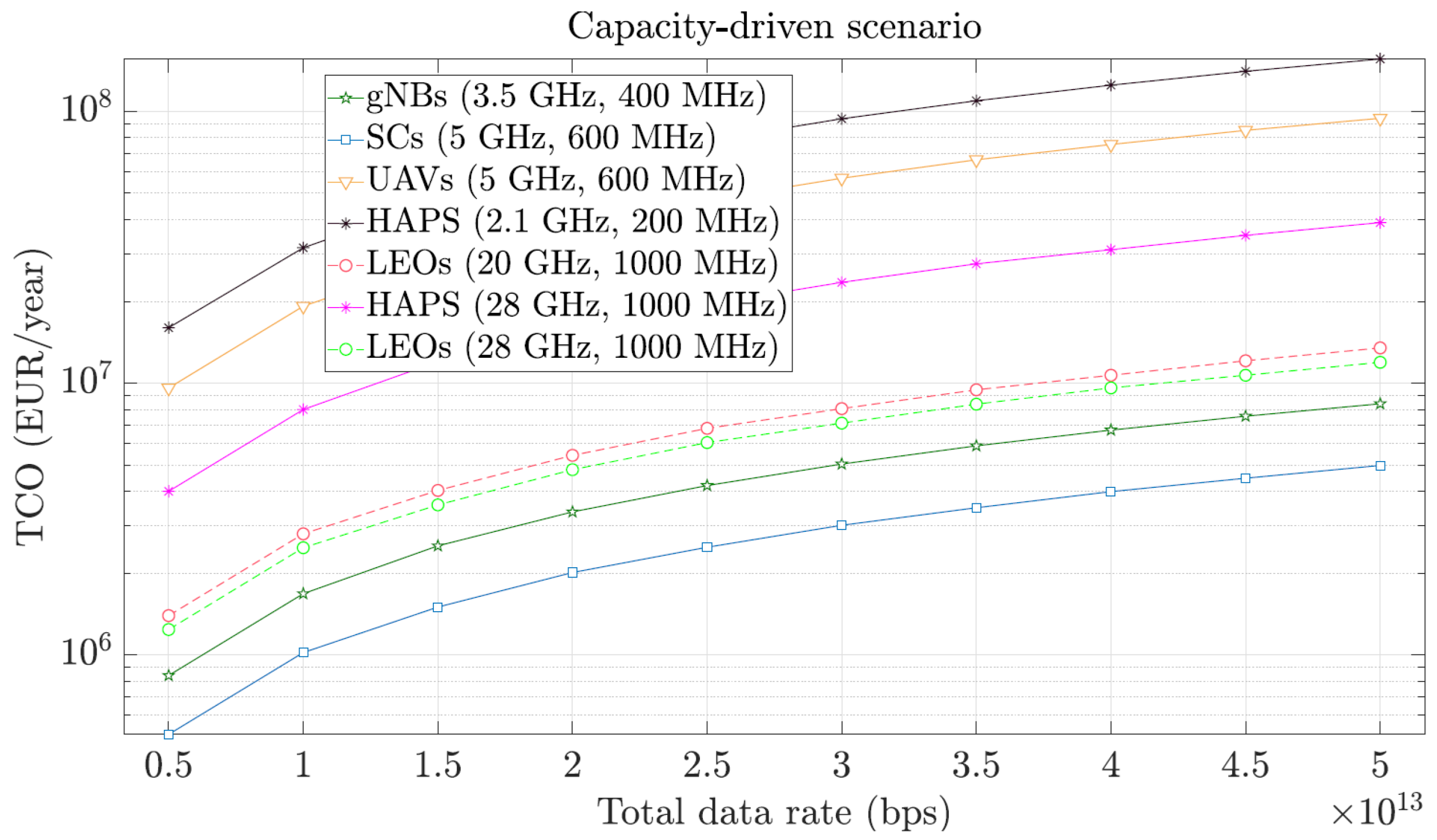

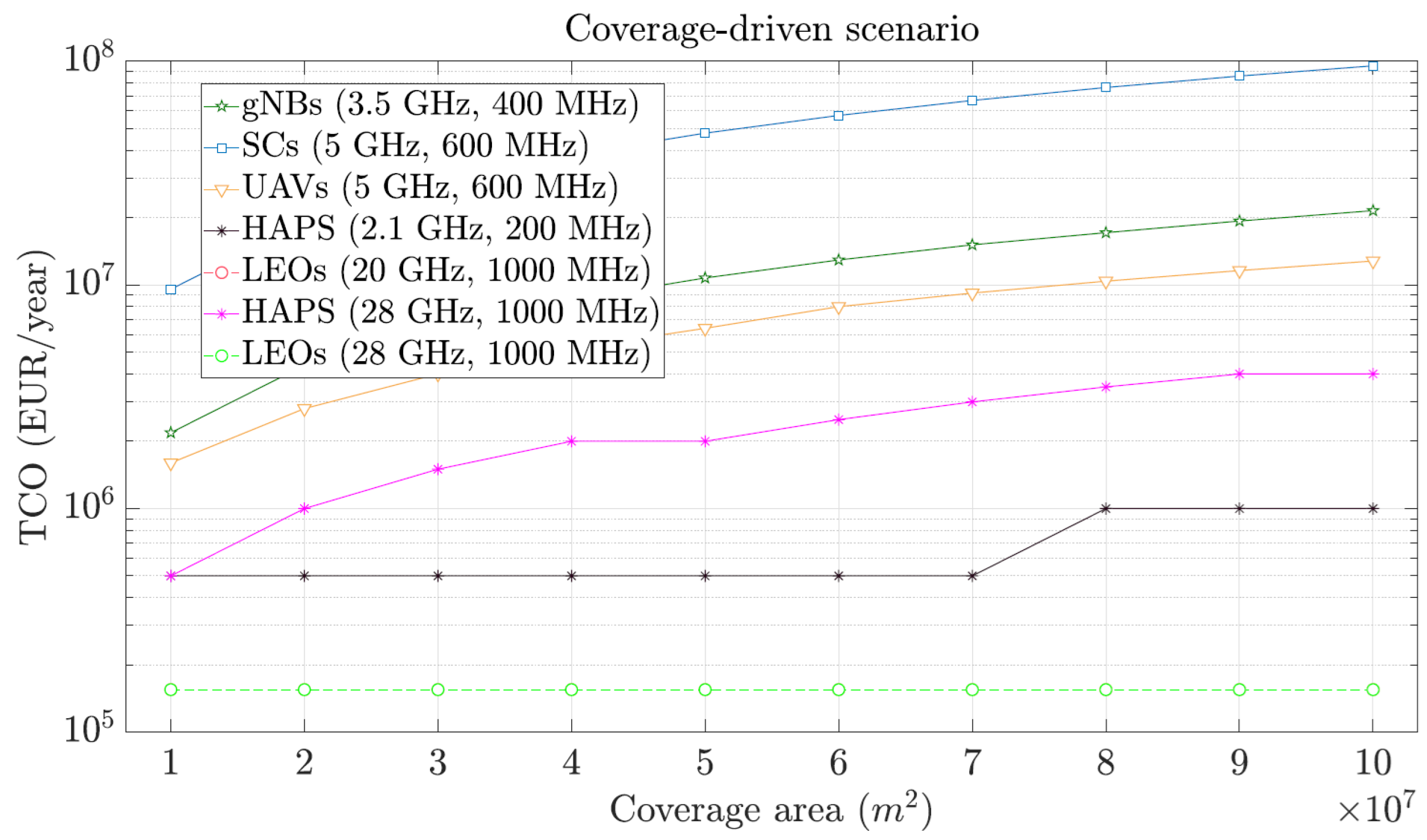

The ETHER project [

35] addresses the issue of vertical handovers TN-NTN to guarantee QoS and service availability, LEO satellite swarms acting as a distributed antenna system to boost the energy balance of the radio link enabling use of a low-dimensions integrated antenna in both TN and NTN connectivity, and uninterrupted connectivity for air-space safety-critical operations during flight lifecycle. The project also conducted a techno-economic analysis of various mobile network implementation options for capacity-driven and coverage-driven scenarios [

36]. For the former, associated with highly urbanised areas, the best option providing the lowest Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) is based on terrestrial BSs in 3.5 GHz band, having high capacity, with further densification of densely populated areas with small cells (cf.

Figure 4). For the latter, typical for remote areas, the lowest TCO is achieved with satellite BSs in 28 GHz band, and the next option is utilisation of BSs in 2.1 GHz band on board of on HAPs (cf.

Figure 5).

The 6G-NTN project [

37] takes up, among others, the topic of UAS support by mobile NTN, demonstrating capabilities for Urban Air Mobility (UAM) – on-demand creation of aerial corridors for last-mile delivery (pre-flight service), anti-collision/autonomous deconfliction and emergency situation management (both in-flight services) as well as a selected UAS use case on situational awareness (long-range infrastructure inspection, both routine autonomous and manual ones).

The CELTIC-NEXT project 6G-SKY [

38] aims at the idea of “connected sky” – NTN support for both manned and unmanned aviation, including, i.a., UAM use cases (flying taxis/buses/cars and smart city/industry/logistics services) and integration with both manned and unmanned air traffic management systems.

2.3.5. UAS for Cultural Heritage Preservation

Preserving cultural heritage is another domain where UAS have great potential. The project titled “An integral approach in creating digital twins of archaeological immovable monuments using innovative technologies” was funded by The Bulgarian National Science Fund under the BNSF Fundamental Research Competition 2024 (KP-06-H82/1 from 6. December 2024). It explores innovative coded markers, advanced photogrammetric techniques, and precise 3D reconstruction workflows for documenting archaeological and architectural heritage using terrestrial, aerial and underwater imaging modalities. The research demonstrates how the combination of UAS-based photogrammetry, pattern-recognition algorithms, and cross-platform marker identification significantly enhance the accuracy, automation and reliability of field data acquisition. These methodologies follow the ADOPT principles, especially Awareness and Situation Detection. The project demonstrates operations with high-fidelity spatial information, multi-sensor data fusion, scaling, georeferencing challenges, and workflow optimisation in heterogeneous operational environments. It also shows how UAS-enabled mapping can provide accurate 3D digital twins and objective spatial metrics, which can be useful in various domains.

2.3.6. Public Trials and Commercial Implementations of 5GS and UAS Integration

An example of the usefulness of UAS as mobile communication stations has also been showcased by Deutsche Telekom, which used a fixed wing drone to provide mobile network coverage to customers on a live commercial network. From an altitude of 2.3 km a drone with an integrated mobile BS provided coverage on the slopes at the Jizerská 50 race. Deutsche Telekom teamed up with Primoco UAV SE to jointly develop and test the unique solution for temporary mobile coverage. During its first deployment, the drone provided continuous coverage under favourable weather conditions for 4 hours over an uncovered six kilometre stretch of the race’s route. Without interfering with the nature reserve, T-Mobile Czech Republic could ensure that the 4,460 participants in the 50-kilometre main race were always connected – reaching download speeds of up to 95 Mbps and an uplink of up to 34 Mbps [

39].

Moreover, there is currently a project in Germany testing out the feasibility of using multirotor drone swarms for firefighting purposes. Due to the significant increase of forest and vegetation fires worldwide in the recent decades, the project’s mission is to develop a firefighting drone system together with experts from the fire department that will revolutionise firefighting and provide an efficient supplement to conventional extinguishing methods. The proposed solution of the PEELIKAN project is a swarm of drones that will fly from a mobile supply station to a fire site up to 5 kilometres away. The drones will be controlled via satellite technology, their batteries and extinguishing agent will be automatically swapped and refuelled, respectively. The swarm is 100% electrically driven with capabilities of 24 hour non-stop operations [

40].

For drones used for long-duration missions, where the payload is also characterised by significant both mass and electrical power consumption, the efficiency of the power supply system becomes paramount. In the case of stationary operation (hovering at a specific point), e.g., carrying occasional mobile network BS equipped with an antenna system in disaster recovery or special event circumstances, tethering is possible – power and connectivity for the drone can be supplied from the ground via an integrated electrical-fibre optic cable. While the cable mass, related to the power consumption of both UAV and payload, will contribute to the total payload mass, influencing, e.g., the maximum achievable altitude and therefore the coverage radius, ensuring uninterrupted operation in these circumstances will be a key advantage of tethering. For comparison, the power consumption of a terrestrial 3-sector 5G macrocell providing coverage within a radius of several kms is approximately 1 kW, while for a terrestrial 1-sector microcell with a radius of maximum 500 m, the power consumption is around 100 W [

41]. With high voltage powering, and thus limiting the supply current, hence the required cross-section of the power supply cables, it is even possible to limit the weight of the integrated power supply (electric) and transmission (fibre optic) tethering cable to 400 g per 100 m providing the maximum UAV operation altitude of 500 m AGL [

33].

3. Results

This section presents the optimal development path. The emphasised SoS is yet an ideal vision, and the current foresight aims to explain why it needs to be developed in its optimal form, and how crucial for its operations the AAM, supported by ACS, is. The monitoring and reliable fast high added value goods delivery can be assured only by implementing AAM, which to be constantly backed by ACS.

3.1. SUDEM SoS

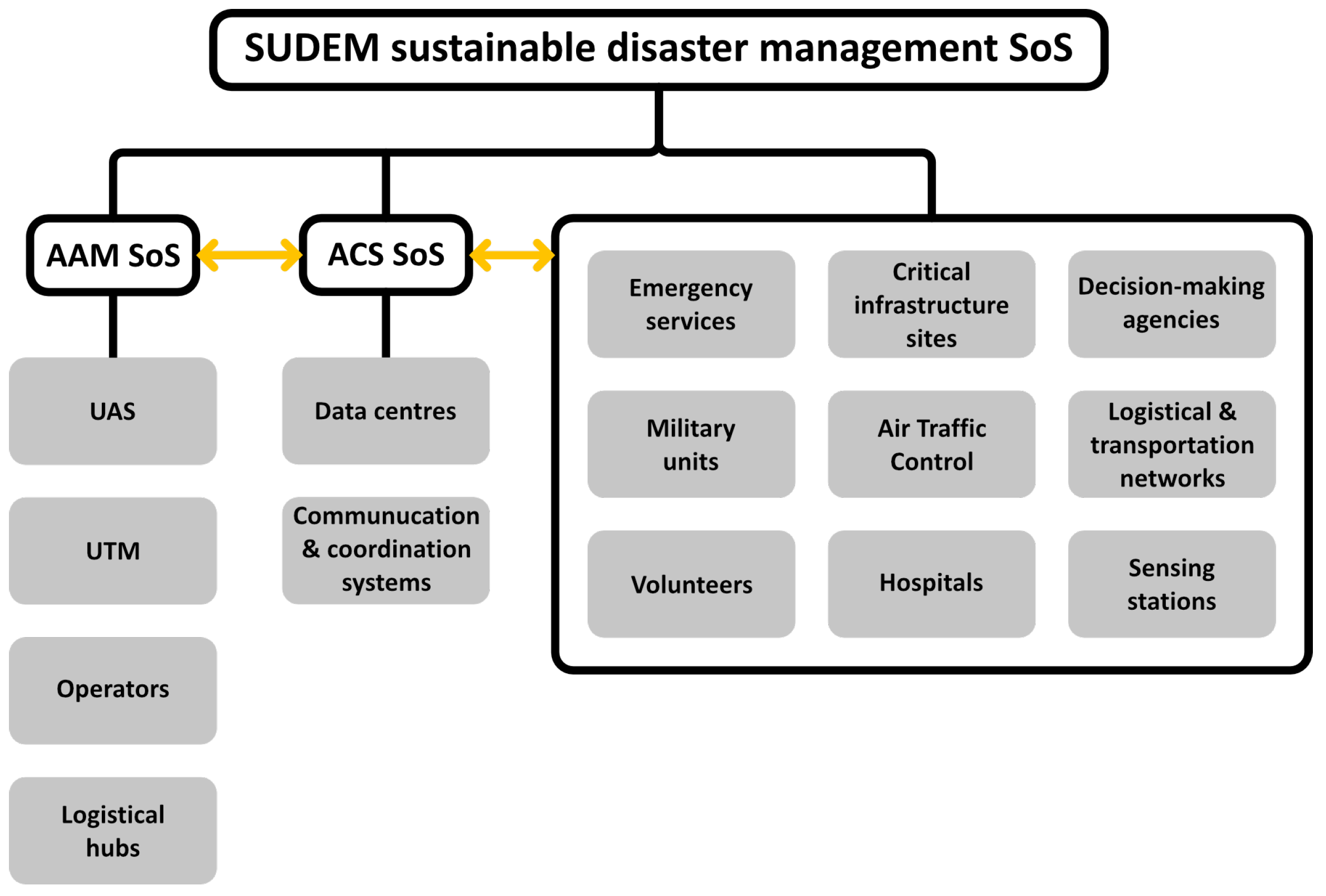

The SUDEM SoS approach, as presented in

Figure 6 consists of the already established DM systems and stakeholders, as well as the novel AAM SoS and the ACS SoS, with the ACS envisioned as the key enablers of sustainable and efficient operations.

Part of the SUDEM Foresight investigation revealed that while many countries have established foundational digital infrastructures for DM, there is significant variability in the maturity and integration of these systems. For example, Germany and the Netherlands possess well-developed flood monitoring and predictive systems powered by IoT and AI, while Turkey has a robust network for seismic monitoring and early warning systems. However, each country faces specific challenges that hinder full digitisation, such as cybersecurity threats, data integration issues, and protocol inconsistencies across administrative regions.

To summarise, a SoS approach is needed for the DM domain together with AAM and ACS, in order to improve processes efficiency and decision making support. These improvements will be achieved by combining data from various sensors (land and water sensors, aerial sensors, weather sensors, satellite constellations, etc.), which will be used to plan adequate and effective resource allocation for optimal response and prevention of tragic outcomes.

3.2. REGUAS – AAM-Supported DM

Considering the findings of the REGUAS project, it should be noted that in the context of DM, the usefulness of UAS could be increased further, due to the presence of extreme emergency conditions. Rubble from buildings or landslides, collapsed infrastructure, or simply geographic inaccessibility could prevent land vehicles from being able to deliver much needed supplies. In such cases, the need for adequate public service outweighs the need for better energy efficiency, since drones can bypass obstacles and treacherous terrain to deliver emergency goods and also to perform much needed monitoring of the given disaster situation. UAS , equipped with imaging technology and sensors, can play a crucial role in situational assessment, especially in disaster zones that are inaccessible by traditional means.

REGUAS shows that deliveries of high added value goods in the DM and emergency context can be operationally sustainable and efficient. However, for this to happen there need to be ready, resilient, and redundant ACSs. For example, for UAS DM and emergency operations, such as situational awareness and goods delivery, UTM would be required for efficiency, safety and reliability, which would be enabled by various ACS. Additionally, the efficiency of AAM operations in this context will be enhanced further by utilising digital planning and routing tools, similar to the one used in the REGUAS project.

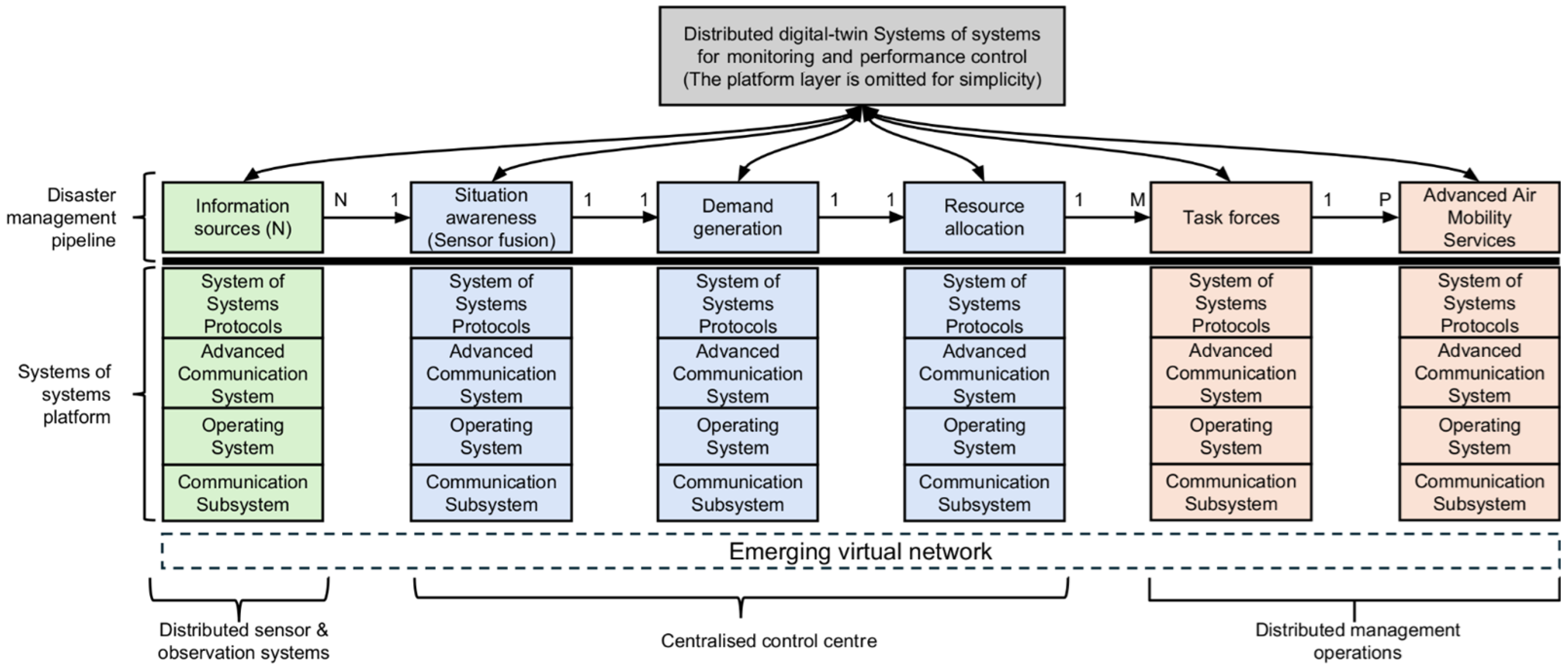

Figure 7 illustrates the AAM-supported SoS architecture for DM, based on a SoS control centre approach. This reference architecture encapsulates the foundational concepts presented in this article. The architecture is organised into three horizontal system layers:

Emerging Virtual Network (bottom layer): Formed through the complex interaction patterns among constituent systems, enabling adaptive and decentralised connectivity.

SoS Platform (middle layer): Provides a dynamically configurable execution environment that supports the orchestration and coordination of higher-level DM components. Each system in this layer consists of four layers. The bottom two layers are also adopted in conventional systems which provide the basic distributed computation services. The top two layers provide generic systems of systems protocols for coordination and advanced management services for dynamic communication.

DM Pipeline (top layer): Responsible for executing E2E DM tasks, including detection, demand generation, resource allocation, activating tasks forces that utilise Advanced Mobility Services.

At the top of the

Figure 7, the systems of the DM pipeline are monitored and evaluated by the distributed digital twin SoSs according to the predefined KPIs. If necessary, corrective actions are executed on the pipeline. The architecture can also be viewed in terms of three groups of cooperating vertical systems:

Distributed Information Sources (N): A set of N distributed data sources that provide critical input for sensor fusion, enabling accurate and timely situational awareness.

Control Centre Systems: A set of interoperable subsystems within one or more control centres, causally interconnected to perform the core functions of DM. Multiple control centres can operate concurrently, ensuring robustness and scalability.

Task Forces (M): A collection of M operational units, such as firefighting teams, search-and-rescue squads, medical emergency responders, and security forces. These task forces leverage P different AAM services tailored to the specific requirements of their missions.

3.3. Sensor Data Fusion Including AI

IoT-enabled sensors can provide continuous environmental data that can enhance situational awareness and enable rapid responses to emergent conditions. Machine learning and AI applications in DM, including predictive modelling and automated resource allocation, can allow emergency management teams to anticipate disaster impacts and deploy resources proactively.

The integration of heterogeneous information sources is a key enabler of effective DM. In line with the framework proposed by Akşit et al. [

10], this foresight confirms that model-based analysis and synthesis of data fusion alternatives can substantially improve the accuracy and timeliness of situational awareness. In disaster response operations, information collected from IoT-enabled ground sensors, aerial drones, and satellite imagery often differs in granularity, reliability, and cost. The model-based approach allows for selecting the most efficient fusion configuration by balancing detection precision, coverage requirements, budget constraints, and processing deadlines. Within the SUDEM SoS context, this ensures that emergency control centres can prioritise data sources dynamically, achieving robust monitoring while optimising limited computational and communication resources. Such a structured fusion strategy enhances the ability to detect disaster effects rapidly, locate survivors, and coordinate task forces effectively under varying operational conditions.

The future development directions, identified in the SUDEM Foresight, to address the full digitalisation challenges, are focused on the need for standardised protocols, enhanced cybersecurity measures, and advanced predictive capabilities. The optimal future envisioned in this report involves a fully integrated DM framework where real-time data sharing, predictive analytics, and autonomous decision making systems operate seamlessly across borders. This would enable a cohesive and rapid response to a wide range of disaster types, including floods, earthquakes, wildfires, and industrial accidents, leveraging technologies to automate and enhance resilience in disaster response.

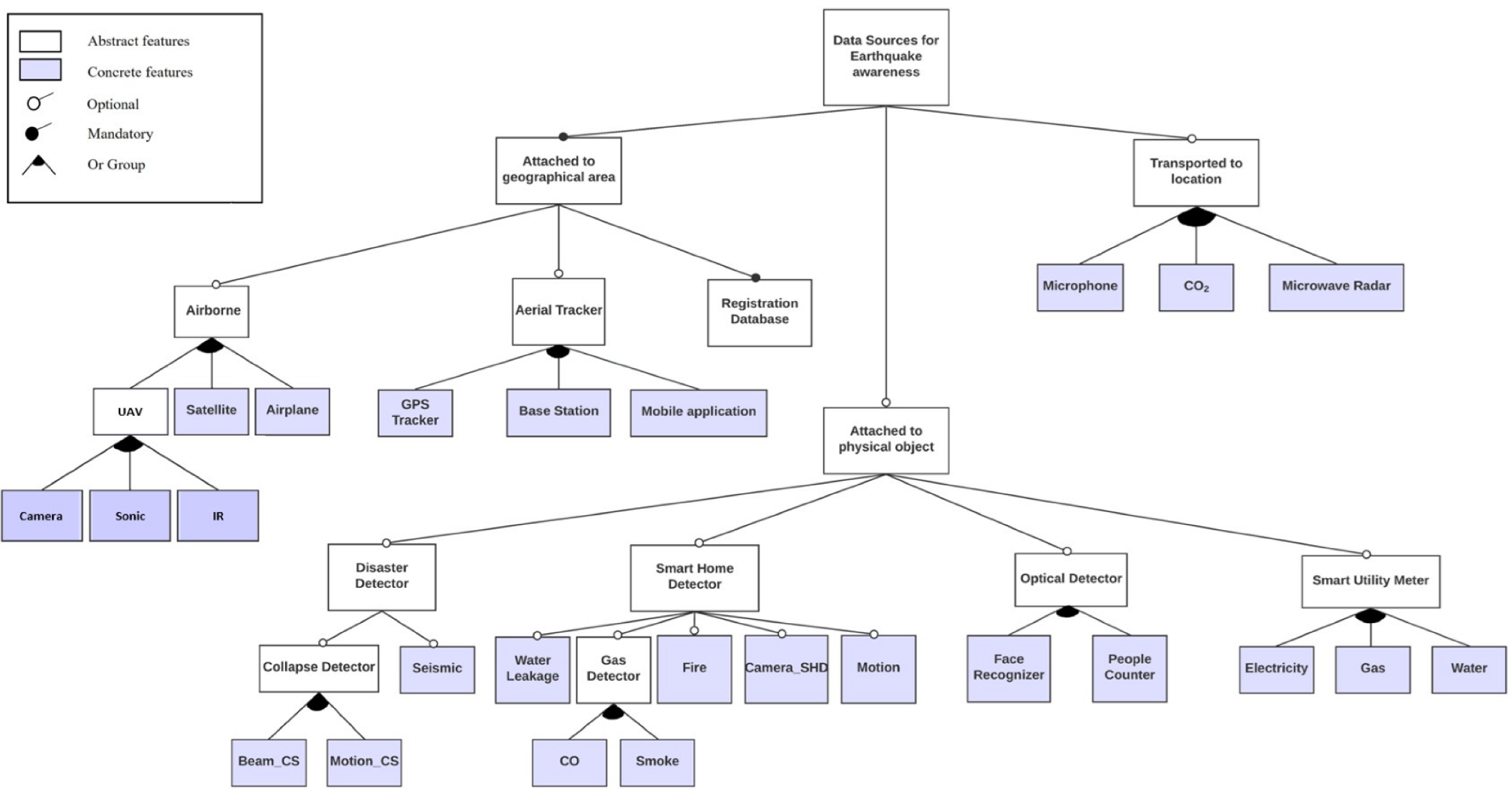

As illustrated in

Figure 8, the information sources are organised as a SoS, enabling mutual communication as well as interaction with the central control centre to support efficient and effective information fusion. Such architecture is critical for conducting timely and accurate post-disaster aid operations. For instance, following an earthquake, emergency control centres must rapidly assess the scale and severity of the impact to initiate appropriate response actions.

Information sources encompass a diverse set of data-gathering technologies – such as sensors, cameras, and UAVs – which can be deployed to collect data from affected areas. To enhance situational awareness, advanced data fusion techniques are applied to integrate information from these heterogeneous and distributed sources.

In [

10], a design environment is introduced for computing the optimal composition of information sources, subject to the following four constraints:

The disaster impact must be assessed with a defined level of precision.

The locations of surviving individuals must be determined within acceptable accuracy.

The overall cost of data fusion must remain within a predefined budget.

The fusion process must be completed within a specified detection deadline.

Another topic and a recurring theme, across the countries analysed in the SUDEM Foresight, is the need for standardised protocols to enable interoperability, particularly in cross-border disaster scenarios. Standardisation would address one of the primary challenges – disparate data collection and processing practices – which currently limit the effectiveness of real-time data sharing and cross-agency coordination. The European Union could play a pivotal role in facilitating these efforts by establishing region-wide data and protocol standards, drawing on the Modular Warning System (MoWaS) [

42] in Germany and the AYDES platform [

43] in Turkey, as models for integrated, standardised DM systems.

Additionally, the SUDEM Foresight report highlighted the need for advanced cybersecurity measures, including encryption, multi-factor authentication, and continuous threat monitoring. These security measures must be reinforced across all digital platforms, particularly in countries like the Netherlands and Germany, where critical infrastructure is heavily reliant on digital networks. A comprehensive cybersecurity strategy is essential to ensure the integrity of DM systems and to maintain public trust in these systems’ ability to operate reliably during crises.

3.4. ACS Development Roadmap

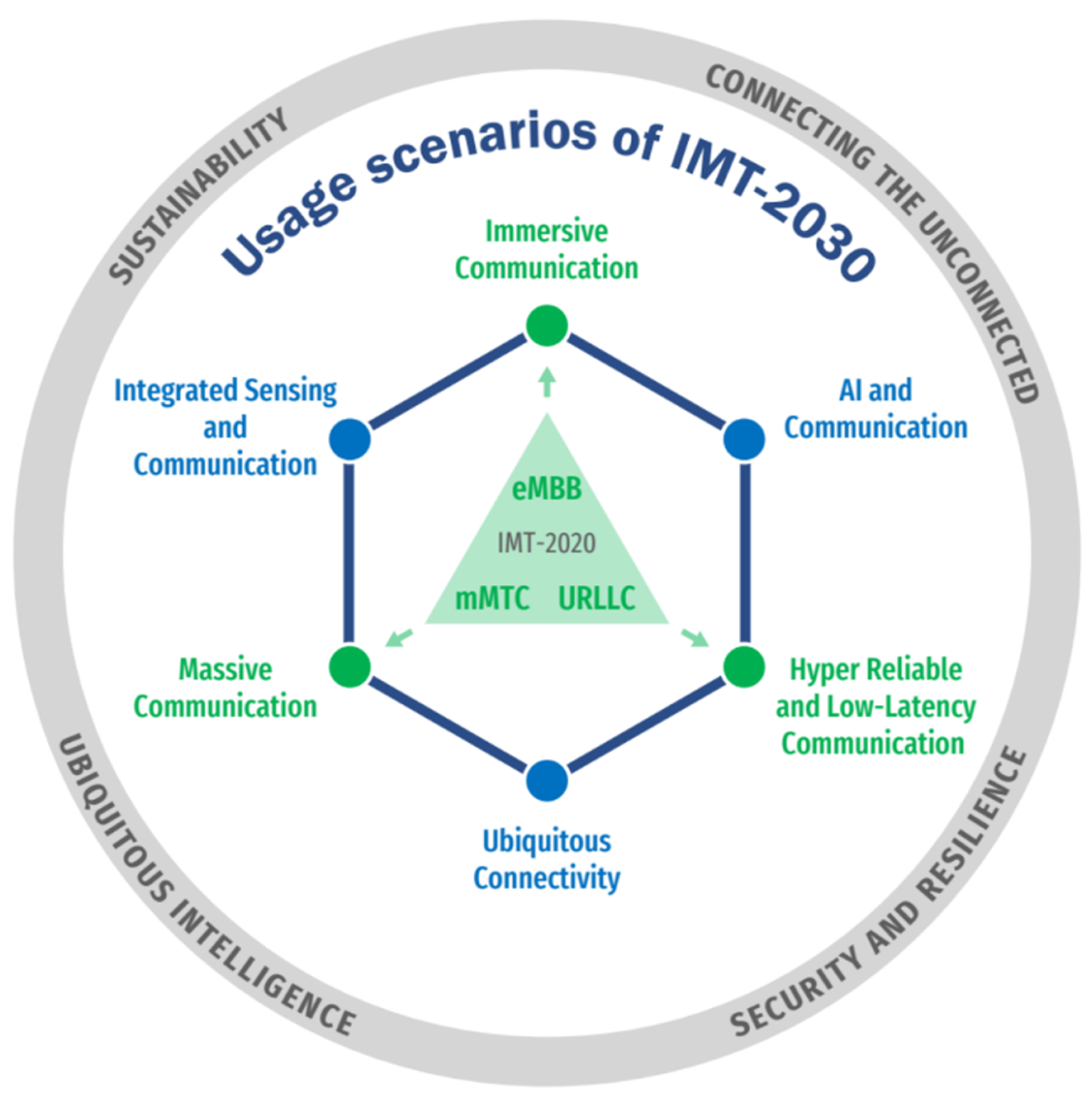

Future development roadmap in the ACS field will impact the future of AAM SoS. While the development of 5G standardisation continues until the end of 2020s, the directional vision of a 6G System (6GS) framework (IMT-2030) has been published by ITU [

44]. Following the civilizational and industrial trends (sustainability, connecting the unconnected, security and resilience, and ubiquitous intelligence), the further proliferation of deeper fused communication, application computing, and AI is foreseen. Three usage scenarios of IMT-2020 are renamed and upgraded through increase of their QoS targets. New scenarios will emerge (cf.

Figure 9), namely Integrated Sensing and Communication (ISAC), AI and Communication, and Ubiquitous Connectivity.

Table 1 presents the evolution of performance targets from 4

th Generation (4G) to 6

th Generation (6G). According to the ITU timeline [

45], the current phase of detailed minimum RAN technical performance requirements building (analogous to existing for IMT-2020 [

14]) followed by defining the evaluation criteria and methodology is going to be concluded at the end of 2026. Next, the phase of technology proposal for IMT-2030, evaluation, consensus, and IMT-2030 specifications publishing is scheduled to be finished at the end of 2029.

The 3GPP roadmap for 6G development is only partially known, but unlike the ITU, 3GPP working documents are publicly available. Release 20, which was launched at the beginning of 2025 and the freeze of the entire set of its document is scheduled at the middle of 2027, is dedicated – in addition to the further development of 5G-Advanced – to 6G studies. The 3GPP Release 21 will be the first to provide normative documents on the 6GS (architecture, procedures, protocols specification) but its timeline is expected no later than in June 2026, and its freeze no earlier than in March 2029, thus able to deliver the first 3GPP normative 6GS specifications for IMT-2030 submission within the ITU schedule [

46]. Currently, the study on 6G use cases and service requirements is progressing; the early stage but quite abundant document [

47] provides already a list of 110 foreseen 6G use cases among which the following are related to AAM and DM:

AI-agents communication – AI agents, also those on board of UAVs, to cooperate on collective accomplishment of tasks, by the means of mutual communication and sharing of locally available information.

Collaborative AI agents hosted by the network – off-loading of UAV’s computing and power resources.

Intelligent UAV swarms – mutual sharing of on-board cameras, sensors, and lightweight computing resources.

Smart housekeeping – coordinated AI-driven actions with involvement of aerial visual monitoring provided by nearby UAVs in the air.

High-resolution topographical maps/environment object reconstruction – support of building and continuously updating the environmental model – landscape, structures, forestation, dynamic objects – by ISAC capabilities.

Low-altitude UAV traffic supervision – UAV flight assistance service, including illegal UAV intrusion detection, UAV flight trajectory tracing, UAV collision prediction by RAN sensing capabilities.

Advanced modern city transportation system – support of a metropolitan multi-modal Intelligent Transport System (ITS) with sensing-based tracking of transport means by RAN.

Multi-sensor fusion-based sensing for UAV take-off and landing – enhancing the accuracy and reliability of navigation in highly urbanised areas, detection of obstacles, e.g., sudden swarms of birds or rainfalls, assessment of the landing area, and adjustment of path in real time.

Safe & economic UAV transport – ISAC support for real-time airspace management of massive-scale Beyond Visual Line of Sight (BVLOS) flights for parcels, groceries, or rapid medicines delivery in both high-urbanised and remote areas, e.g., islands.

Network-assisted smart transportation – sensing, navigating and positioning of autonomous UAVs for dynamic trajectory management and collision avoidance, off-loading of on-board resources.

Ubiquitous and resilient network – omnipresent connectivity for UAVs.

Resilient positioning in satellite networks – satellite access to support location services of mobile network; 1 m vertical and horizontal accuracy for UAVs with maximum speed of 160 km/h.

Disaster relief – extraordinary connectivity for UAVs used in disaster relief activities.

Low-altitude logistics supported by NTN – supplementing the white spots of TNs with LEO/HAP-based connectivity.

Hybrid TN and NTN positioning – support of UAV flights at speeds of up to 160 km/s with location service latency of tenths of a second.

Ubiquitous emergency rescue via UAVs – support of emergency response actions with application of drones equipped with intelligent rescue planning system, high-resolution cameras, thermal imaging, and environmental sensors.

Communication on board of UAM aircrafts – support of UAV passengers’ flight safety using external sensing information delivered by mobile network for on-board detect and avoid mechanisms, and providing direct connectivity for passengers.

Immersive media services for AAM enabled by 6G NTN – on-board relays for AAM passengers.

Service robots in smart communities – support of UAV patrol robots in crime prevention and medical assistance missions.

Remote and automatic construction – support of UAVs in pre-construction surveying and construction management activities.

Unlike previous ones, the 6GS will be designed to natively use access through both TNs and NTNs. The latter ones will be based on satellites and LAPs/HAPs.

Table 2 provides basic characteristics of communication properties of satellites’ applications. LEO satellites provide the most attractive characteristics in terms of transmission delay and throughput (associated with their capacity to be shared over the lower footprint on the globe compared to MEO and GEO satellites). It should be noted, however, that LEO satellites visibility windows are of the order of minutes, and their very high tangential velocity (e.g., 7.5 km/s) requires special measures to compensate for the Doppler frequency shift. The necessity of frequent handovers increases the intensity of signalling exchange between the user device and the network related to mobility management. HAPs and LAPs provide lower delays than LEO satellites and are usually stationary – with the former located at altitudes beyond the cruising altitude of passenger aircraft (up to 50 km, typically 18-22 km), and the latter – in the airspace below the cruising altitude of passenger aircraft, respectively [

48].

Although, as mentioned above, the 6GS will be defined during the future 3GPP Release 21, new mechanisms and concepts for its architecture are postulated by the research society that may impact AAM support [

49]:

Dynamic beamforming with Multiple Input Multiple Output (MIMO) antennas – individual signal beam to the UAV device to avoid momentary dominance of the signal from a distant BS due to antenna systems radiation patterns imperfections causing unnecessary handovers.

Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces (RISs) – steerable beam reflectors (e.g., installed on facades of buildings) used for “brightening up the black spots” with poor coverage in areas with radio propagation obstacles.

Cell-free RAN – instead of traditional cellular approach, i.e., BS responsibility for coverage in some area, forming a joint signal beam by multiple BSs individually for the specific user device (e.g., on board of UAV).

User-centric RAN – location of processing of the individual user traffic in softwarised RAN tailored to the demand type: various fractions of user traffic can be processed separately to optimise QoS parameters in focus.

Individual mobile networks per user device – instantiation of individual isolated E2E “micro-network” per user – gain on higher network reliability and agility, impact of failure and restoration by a simple restart without time-consuming root cause analysis limited to a single user.

Intent-based interfaces for integration of communications platforms within multi-layer systems – interfacing of subsystems using Large Language Models (LLMs) to convert high-level requests of clients to low-level technology descriptions needed by the requested server [

50,

51].

The ITU and 3GPP visions of future 6GS address the needs of the PPDR use cases class with enhanced support (in comparison with 5GS) of mission-critical management and operation control through low-latency and extremely reliable (possibly, with deterministic guarantees) services heterogeneously combining the individual eMBB, URRLC, and mMTC traffic categories with mission-critical guarantees and omnipresent coverage provided by a unified TN- and NTN-based access. PPDR equipment, in the case of AAM field – UAVs, set very high energy efficiency requirements, which are in focus of 6GS for its network terminals. Combining enhanced localisation capabilities with sensing capability, in line with the ISAC paradigm, will not only enable increased positioning precision, but will also create the ability to scan and map the disaster site (especially one that has been dramatically changed by a natural cataclysm) in order to build its digital model for use in managing both PPDR operations and, in particular, AAM operations during disaster response. Additionally, this digital environment model can provide environmental awareness for RAN control mechanisms to actively improve coverage. Beamforming capabilities will be used to both scan the environment and track the network terminal being served. The software-based network’s reconfigurability will enable continuous response to changing conditions to maintain the required QoS. Native integration with AI (e.g., for network control and management, anomaly or intrusion detection) and enhanced security mechanisms will enable achieving a level of resilience that guarantees robustness to disturbances and thus safety of AAM and, more generally, PPDR operations. In these ways, the future 6GS addresses key societal values of DM/PPDR/AAM that will enable migration of PPDR services from heterogeneous wireless and land mobile systems (e.g., trunked radio) to a unified mobile network [

52].

3.5. Decision Making Support Including AI

Based on the monitoring input data delivered by on-board sensors on drones, and after processing the data, decision making support will be provided in form of modular reaction and/or preparedness and/or emergency and/or recovery scenarios, being generated by AI, based on historic and synthetic data. AAM, supported by a solid ACS, will be a crucial provider of historic data, enabling a rapid self-optimisation of the emphasised SoS.

3.6. Education

Based on the SUDEM project, the main educational domains which should be the focus of future DM developments are:

DM fundamentals: Workflow and risk mitigation, Disaster monitoring, Multi-Agent Decision making processes, System resilience, Nuclear safety, and DM;

Digitalisation: Data-driven decision making support, IoT, AI, Edge Computing;

Train-the-Trainers: Towards long-term sustainable increase of the pool of highly capable experts and trainers in the Disaster Management (DM) domain.

4. Discussion

The integration of IoT, AI, advanced data management technologies, and UAS technologies offers transformative potential to manage floods, wildfires, earthquakes, and human-made accidents more effectively. However, these technologies present challenges, including the need for robust data integration frameworks to combine information from diverse sources and the necessity of cybersecurity measures to protect against data breaches and system vulnerabilities.

In order to achieve such a high level of digital integration, sustained investment in digital infrastructure, robust policy support, and a commitment to continuous innovation are required. As climate change intensifies and new threats emerge, the pressure to adopt agile, technology-driven DM practices will only increase.

A core element to achieve an effective DM SoS is the ACS architecture which will connect various systems, agencies, volunteers, emergency response units, decision making bodies, and AAM operators. An effective response to any disaster or emergency situation is strongly correlated to how efficient and straightforward the communication is between these systems. Additionally, disasters are highly complex scenarios requiring vast coordination efforts from numerous actors. Due to this, ACS should be the cornerstone for an effective DM SoS. This, however, includes the software, hardware, and operational architecture in order to achieve the desired increase in effectiveness.

ACS software should be based on common standards that can be easily understood by national and international operators, as well as efficiently interpreted by various hardware suppliers. ACS hardware should also be based on common standards in order to assure reliability, fair acquisition and operational costs, and ease of operation by relevant DM actors. Naturally, in order for the ACS to work and create an efficient and effective DM SoS, there needs to be a clear and straightforward operational communications architecture. It will allow for everyone in the SoS to know who is responsible for what; how, when, and with whom to communicate; and thus, to know where available resources should be allocated.

While current 3GPP ACSs, paired with AAM, provide strong potential for substantial improvement of DM responses, there are several important challenges to be considered:

Based on the outputs of 3GPP and other standardisation bodies, as well as activities conducted by various research projects, it can be stated that the 5GS’s standardisation has reached functional maturity for modern applications in AAM, and work is currently underway on technologies that will enable economically feasible ubiquitous service coverage. The latter is envisioned as the native feature of the future 6GS to come in the 2030s. 6GS standardisation has not yet started in 3GPP, but it can be already estimated that about 20% of the proposed new use cases may be relevant to AAM. 6G standardisation has not yet started in 3GPP, but it can already be estimated that about 20% of the proposed new use cases may be relevant to AAM, and new 6G network mechanisms and functionalities will enable its even tighter integration with vertical environments, e.g., AAM SoS. However, inter-industry working groups such as ACJA should be reactivated to ensure continued synchronisation of ACS development with AAM.

In the ACS domain, visions, research and standardisation must then be transformed into commercial reality and legal conditions defining feasibility of foresights and prospective plans. Therefore, based on the hitherto experience of mobile systems development, non-technical factors related to ACS have to be included to the AAM foresighting.

3GPP follows the principle of parallel and partially overlapping releases (1,5-2 years duration). The gradual development of the system capabilities results from the agreed 3GPP roadmap based on the prioritisation of needs. 5G standardisation development started in 2014 (first use case and requirement studies in 3GPP Release 13), first specification delivered in Release 15 in the middle of 2019 (commercially deployed in 2020), and 5G/5G-Advanced standardisation development is commonly expected at least until Release 22 (estimated completion year 2030). Similarly, 6G may be anticipated to mature in the half of the 2030s.

Implementation of the 3GPP specification by telco vendors follows 3GPP standardisation according to their separate roadmaps resulting from demand adjusted in time. Implementation of full specification from the beginning is unrealistic, there must be a market pull by operators resulting from customer demand.

Deployment of a new mobile system involves huge investment costs. The 5G Stand-Alone (SA) architecture required by network slicing is currently deployed or in the process of being deployed by only 25% of operators worldwide, and less than half of them (around 11% globally) have launched or soft-launched services requiring 5G SA [

53]. The rest still have the hybrid 4G/5G Non-Stand-Alone (NSA) variant, which is essentially a 4G network with a “boosted” radio (faster throughput).

The implementation of services in mobile networks is additionally hampered by regulatory and legal barriers – spectrum availability, as well as general policies, e.g., “network neutrality”, which makes it difficult or legally impossible to use network slicing due to the prohibition of QoS and resource prioritisation that could degrade pre-existing QoS for the mass client, despite the obvious differences in the social and civilisational importance of services for e-Healthcare (connected ambulance), public safety, AAM (air transportation of basic necessities, e.g., medicines) compared to the consumption of YouTube or Instagram entertainment [

54].

Mobile network operators operate in a highly competitive commercial regime – costs of spectrum licenses and network deployment/operation must be surpassed by the revenue stream; mobile operators cannot afford to invest in “spare” – idle network resources potentially for AAM, without their use being guaranteed, therefore the implementation of a mobile network for AAM SoS must be part of a larger coordinated and sustainable development program agreed by all its actors and even initiated and supported by public authorities also at the legislative and financial levels.

5. Conclusions

The present foresight study results into the following strategic roadmap and action plan. The proposed SoS for sustainable DM is a significant contribution to the intensive work in Europe, and in particular the involved SUDEM project countries. AFAD – a supporter of the SUDEM project – has performed significant steps and developments in bringing first and solid elements of this SoS into practice. Now the automation of all sustainable DM SoS elements and steps has to be introduced and optimised.

Due to the regionally varying climate, socio-economic and technical readiness realms, this process has to be performed with different intensity and following regionally specific approaches. Only if this happens as common efforts of the interested stakeholders and countries, it can provide a maximal benefit to the relevant countries. A shared understanding, knowledge and actions collaboration and transfer can enable an optimal result for the crucial beneficiaries – the society of these regions and countries.

Moreover, following the quadruple helix [

55] logic of the European Commission, automating the SUDEM-relevant processes, in alignment with the learnings from all mentioned and studied applied research and practice projects, and involving their results into the development of the desired SoS, the approach can have a maximal positive impact for our societies. The core impact will be provided by the automated execution and coordination of the proposed processes – elements of the SoS – when a shared and dynamically evolving pool of experts in this highly interdisciplinary field becomes available.

It has become evident that the digitalisation of this entire SoS, as its core element, and the particular sustainable primary introduction and integration of ACS, as enabler of the AAM as a leading element of an efficient automated DM and decision making support, based on relevant novel policies and business models, is the key for success. A success defined by the direct benefit, in all three dimensions of the classical understanding for sustainability – social, economic and environmental.

A quantifiable potential benefit for national and European economy and societies: currently up to four thousand Euros are the costs for emergency preparedness per capita in Europe, in the context of all relevant gradually frequented disasters, many of which resulting from extreme weather events, and these costs can be significantly reduced if the elements of the emphasised SoS become developed and integrated. The envisaged significant monetary costs reduction amounts of the emphasised societal costs, by introducing the SoS, can be invested into the education, research, development, and integration for further developing and integrating the SoS including ACS and AAM. A benefit and innovation cycle that will bring our societies to the next level – knowledge-based economy and societies with a significant level of public safety and preparedness in the context of disaster events.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.G., M.A. and D.Z.; methodology, G.G. and M.A.; validation, all; investigation, all; resources, all; data curation, M.A. and P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, all; writing—review and editing, all; visualisation, all; supervision, G.G.; project administration, G.G. and L.T.; funding acquisition, G.G. and L.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The ERASMUS+ KA220 SUDEM project with a project number 2023-1-BG01-KA220-HED-000159479 mainly contributes to the idea of this study. It deals with elaborating a framework and curriculum for disaster management training in higher education. It is coordinated by the first author and some of the co-authors are involved through the partner organisations they are affiliated to. The REGUAS (REGuliertes REGionales UAS-basiertes Versorgungskonzept) project under grant agreement 45ILM1015E has provided important learnings and results for this study, including the regional high-added value goods delivery concept in detail, as well as the energy efficiency optimisation model for UAS. 5G!Drones was a Horizon 2020 project funded by the European Commission under grant agreement 857031) and has provided significant learnings on enabling safe UAV operations by implementing ACSs solutions integrated with UTM. The ETHER project has received funding from the Smart Networks and Services Joint Undertaking (SNS JU) under the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement 101096526.

Acknowledgments

AFAD is an associated partner of the SUDEM project and has significantly supported its implementation, as well as developed inputs for this paper, in accordance with prof. Mehmet Akşit.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 3GPP |

3rd Generation Partnership Project |

| 4G |

4th Generation |

| 5G |

5th Generation |

| 5GS |

5G System |

| 5QI |

5G QoS Identifier |

| 6G |

6th Generation |

| 6GS |

6G System |

| AAM |

Advanced Air Mobility |

| ACS |

Advanced Communication System |

| AF |

Application Function |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| API |

Application Programming Interface |

| BS |

Base Station |

| BVLOS |

Beyond Visual Line of Sight |

| BWC |

Bandwidth Calendaring |

| C2 |

Command and Control |

| CN |

Core Network |

| CP |

Control Plane |

| DM |

Disaster Management |

| E2E |

End-to-End |

| eMBB |

Enhanced Mobile Broadband |

| ETSI |

European Telecommunications Standards Institute |

| eVTOL |

electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing aircraft |

| FPV |

First Person View |

| GBR |

Guaranteed Bit Rate |

| GBRSS |

Guaranteed Bit Rate Streaming Service |

| GEO |

Geostationary Earth Orbit |

| GNSS |

Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GSMA |

Global System for Mobile Communications Alliance |

| HAP |

High Altitude Platform |

| HDLLC |

High Data rate and Low Latency Communications |

| HMTC |

High-Performance Machine-Type Communications |

| IoT |

Internet of Things |

| IP |

Internet Protocol |

| ISAC |

Integrated Sensing and Communication |

| ISL |

Inter-Satellite Link |

| IT |

Information Technology |

| ITS |

Intelligent Transport System |

| ITU |

International Telecommunication Union |

| KPI |

Key Performance Indicator |

| LAP |

Low Altitude Platform |

| LEO |

Low Earth Orbit |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| LoS |

Line of Sight |

| LTE |

Long Term Evolution |

| MADRL |

Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| MANO |

Management and Orchestration |

| MC |

Metrics Calculator |

| MEC |

Multi-access Edge Computing |

| MEO |

Medium Earth Orbit |

| MIMO |

Multiple Input Multiple Output |

| ML |

Machine Learning |

| MMTC |

Massive Machine Type Communications |

| MNO |

Mobile Network Operator |

| MS |

Monitoring System |

| NBI |

NorthBound Interface |

| NE |

Network Element |

| NEF |

Network Exposure Function |

| NEST |

NEtwork Slice Template |

| NF |

Network Function |

| NS |

Network Slicing |

| NSA |

Non-Stand-Alone |

| NTN |

Non-Terrestrial Network |

| OF |

OpenFlow |

| PPDR |

Public Protection and Disaster Relief |

| QF |

QoS Factor |

| QL |

Q-Learning |

| QoS |

Quality of Service |

| RA |

Resource Allocation |

| RAN |

Radio Access Network |

| RC |

Rerouting Cost |

| RCCE |

Resource Consumption Curve Estimation |

| RIS |

Reconfigurable Intelligent Surface |

| RL |

Reinforcement Learning |

| RM |

Regret Matching |

| RSIR |

Reinforcement learning and Software-defined networking Intelligent Routing |

| SA |

Stand-Alone |

| SLA |

Service Level Agreement |

| SoS |

System of Systems |

| SotA |

State of the Art |

| SP |

Shortest Path |

| SR |

Source Routing |

| SST |

Slice/Service Type |

| TCO |

Total Cost of Ownership |

| TN |

Terrestrial Network |

| TSN |

Time-Sensitive Networking |

| UAM |

Urban Air Mobility |

| UAS |

Unmanned Aircraft System |

| UAV |

Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| UDP |

User Datagram Protocol |

| UP |

User Plane |

| URLLC |

Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communication |

| UTM |

Unmanned Aircraft Systems Traffic Management |

| V2X |

Vehicle to Everything |

References

- European Commission. Strategic foresight. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/strategic-foresight_en.

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). The Sendai Framework Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction. “Disaster management”. https://www.undrr.org/terminology/disaster-management.

- Zibulewsky, J. Defining Disaster: The Emergency Department Perspective. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 2001, 14, 144–149. [CrossRef]

- Bakirman, T.; Bayram, B.; Akpinar, B.; Karabulut, M.F.; Bayrak, O.C.; Yigitoglu, A.; Seker, D.Z. Implementation of ultra-light UAV systems for cultural heritage documentation. Journal of Cultural Heritage 2020, 44, 174–184. [CrossRef]

- Andreeva-Mori, A.; Sziroczák, D.; Schwoch, G.; Murça, M.C.R.; Dziugiel, B.; Homola, J.; Kramar, V. Enhancing public good missions and disaster response with advanced aerial technology: opportunities and challenges. In Proceedings of the ICAS Proceedings. ICAS Press, 2024, p. 1259.

- Shahen Shah, A.F.M. Architecture of Emergency Communication Systems in Disasters through UAVs in 5G and Beyond. Drones 2023, 7. [CrossRef]

- International Council on Systems Engineering (INCOSE). Systems of Systems Primer. https://www.incose.org/publications/technical-product-catalog/sos-primer.

- Akşit, M.; Eren, M.A.; Say, H.; Yazar, U.T. Chapter 5 – Key performance indicators of emergency management systems. In Management and Engineering of Critical Infrastructures; Tekinerdogan, B.; Akşit, M.; Catal, C.; Hurst, W.; Alskaif, T., Eds.; Academic Press, 2024; pp. 107–124. [CrossRef]

- World Alliance on Digitalization for Disaster & Emergency Management. https://www.waddem.com/.

- Akşit, M.; Say, H.; Eren, M.A.; de Camargo, V.V. Data Fusion Analysis and Synthesis Framework for Improving Disaster Situation Awareness. Drones 2023, 7. [CrossRef]

- ETSI. Network Functions Virtualisation (NFV). https://www.etsi.org/technologies/nfv.

- Sylva – The Linux Foundation Projects Site. https://sylvaproject.org/.

- ITU-R. IMT Vision – Framework and overall objectives of the future development of IMT for 2020 and beyond. Recommendation M.2083, International Telecommunication Union – Radiocommunication Sector, Sep. 2015. https://www.itu.int/rec/r-rec-m.2083.

- ITU-R. Minimum requirements related to technical performance for IMT-2020 radio interface(s). Report M.2410, International Telecommunication Union – Radiocommunication Sector, Nov. 2017. https://www.itu.int/pub/R-REP-M.2410.

- 3GPP. Service requirements for the 5G system. Technical Standard TS 22.261, ver. 20.3.0, 3rd Generation Partnership Project, Jun. 2025. https://www.3gpp.org/dynareport/22261.htm.

- 3GPP. Unmanned Aerial System (UAS) support in 3GPP. Technical Standard TS 22.125, ver. 19.2.0, 3rd Generation Partnership Project, Jun. 2024. https://www.3gpp.org/dynareport/22125.htm.