Submitted:

07 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Why Data Integrity is Crucial in Life Science Research

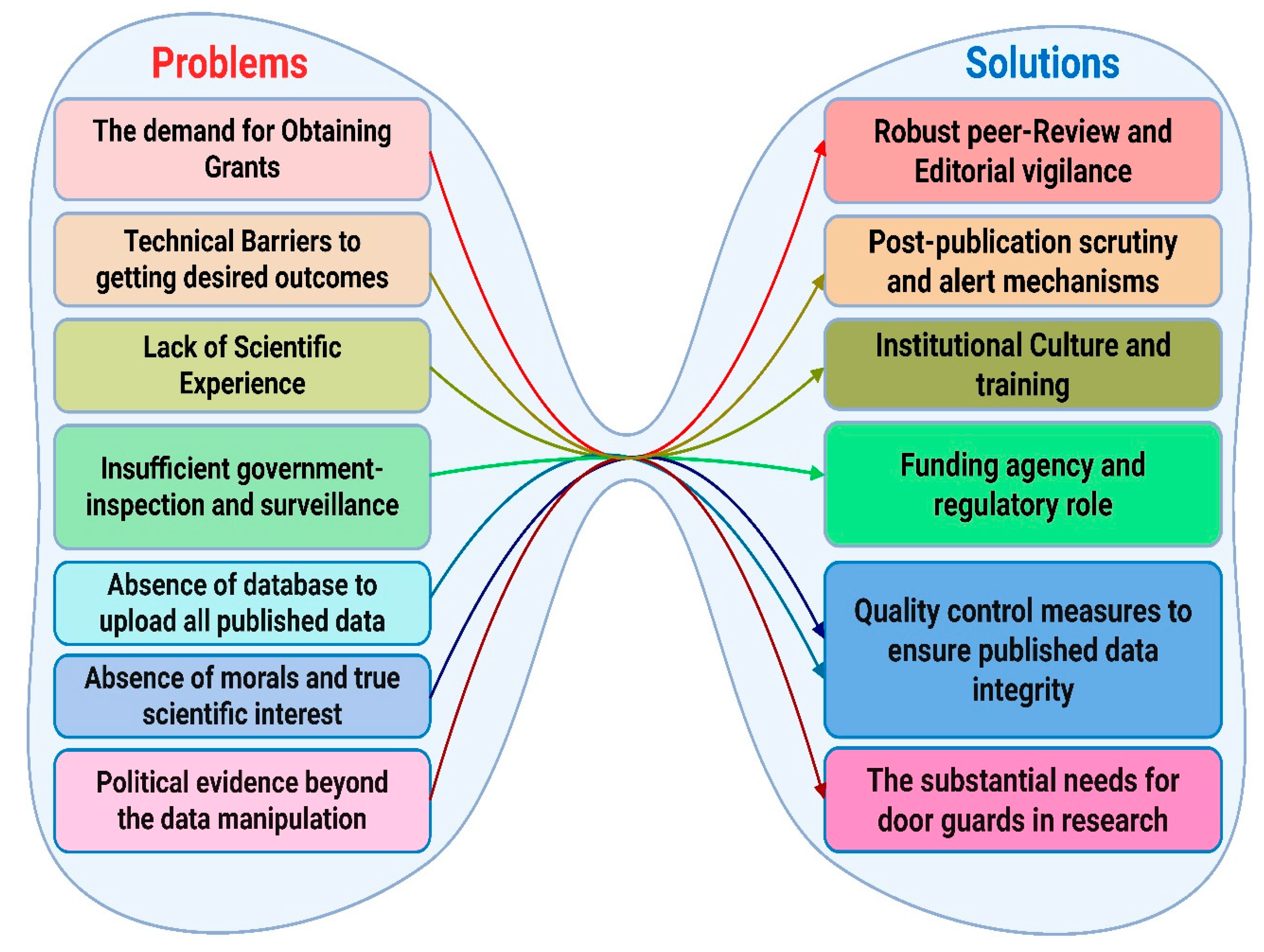

3. Reasons Beyond Data Manipulation

3.1. The Demand for Obtaining Grants

3.2. Technical Barriers for Getting Desired Outcomes

3.3. Lack of Real Scientific Experience

3.4. Insufficient Governmental Inspection and Surveillance

3.5. Absence of Database to Upload All Data to the Public

3.6. Absence of Morals and True Scientific Interest

3.7. Political Evidence Beyond the Data Manipulation

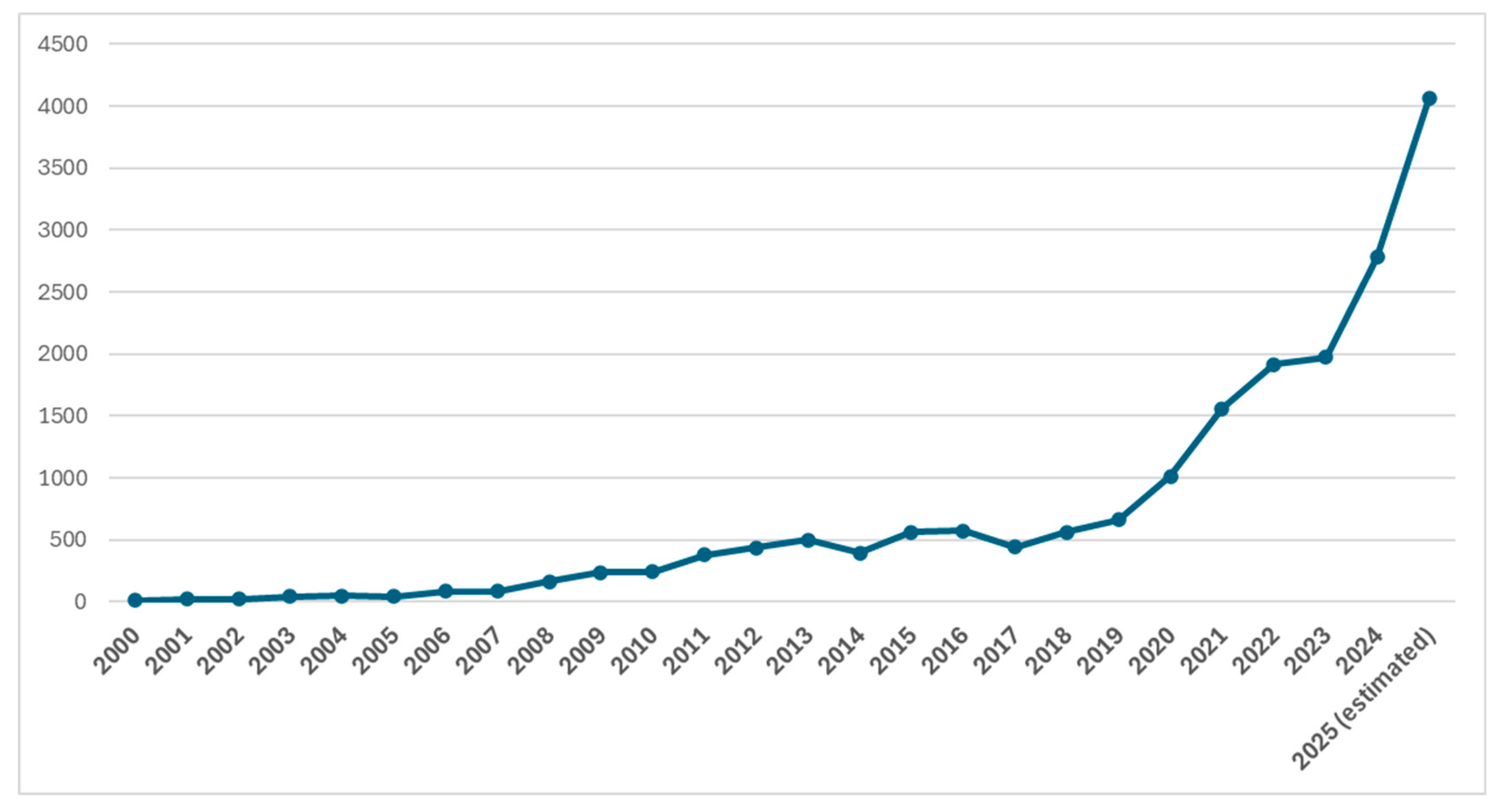

4. Life Sciences Retraction Trends: Scope and Growth

4.1. Overall Increase in Retractions

4.2. Misconduct vs. Error

4.3. Discipline, Geography, and Team Patterns

5. The Risks and Ramifications of Data Fabrication in Life Sciences

5.1. Ripple Effects Across Research

5.2. Institutional and Career Consequences

5.3. Paper Mills and Fake Peer Review

6. Upholding Data Integrity: Strategies and Obligations (The Solutions)

6.1. Robust Peer Review and Editorial Vigilance

6.2. Post-Publication Scrutiny and Alert Mechanisms

6.3. Institutional Culture and Training

6.4. Funding Agency and Regulatory Role

6.5. Quality Control Measures to Ensure Published Data Integrity

6.6. The Substantial Need for Door Guards in Research

7. Conclusion: Facing the Threat of Fabrication, Strengthening the Future

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cogan, E. Preventing fraud in biomedical research. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 932138. [CrossRef]

- Thiese, M.S.; Walker, S.; Lindsey, J. Truths, lies, and statistics. J Thorac Dis 2017, 9, 4117-4124. [CrossRef]

- Phogat, R.; Manjunath, B.C.; Sabbarwal, B.; Bhatnagar, A.; Reena; Anand, D. Misconduct in Biomedical Research: A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent 2023, 13, 185-193. [CrossRef]

- Rao, K.N.; Mair, M.; Arora, R.D.; Dange, P.; Nagarkar, N.M. Misconducts in research and methods to uphold research integrity. Indian J Cancer 2024, 61, 354-359. [CrossRef]

- Deaton, A.; Cartwright, N. Understanding and misunderstanding randomized controlled trials. Soc Sci Med 2018, 210, 2-21. [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine; Policy and Global Affairs; Committee on Science, Engineering, Medicine, and Public Policy; Board on Research Data and Information; Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences; Committee on Applied and Theoretical Statistics; Board on Mathematical Sciences and Analytics; Division on Earth and Life Studies; Nuclear and Radiation Studies Board; Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education; Committee on National Statistics; Board on Behavioral, Cognitive, and Sensory Sciences; Committee on Reproducibility and Replicability in Science. In Reproducibility and Replicability in Science; National Academies Press (US); 2019 May 7. 5, Replicability.: Washington (DC), 2019.

- Kemp, P.L.; Alexander, T.R.; Wahlheim, C.N. Recalling fake news during real news corrections can impair or enhance memory updating: the role of recollection-based retrieval. Cogn Res Princ Implic 2022, 7, 85. [CrossRef]

- Gautret, P.; Lagier, J.C.; Parola, P.; Hoang, V.T.; Meddeb, L.; Mailhe, M.; Doudier, B.; Courjon, J.; Giordanengo, V.; Vieira, V.E.; et al. RETRACTED: Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020, 56, 105949. [CrossRef]

- Bricker-Anthony, R.; Herzog, R.W. Large-scale falsification of research papers risks public trust in biomedical sciences. Mol Ther 2024, 32, 865-866. [CrossRef]

- Rao, T.S.; Andrade, C. The MMR vaccine and autism: Sensation, refutation, retraction, and fraud. Indian J Psychiatry 2011, 53, 95-96. [CrossRef]

- Desai, A.N.; Ruidera, D.; Steinbrink, J.M.; Granwehr, B.; Lee, D.H. Misinformation and Disinformation: The Potential Disadvantages of Social Media in Infectious Disease and How to Combat Them. Clin Infect Dis 2022, 74, e34-e39. [CrossRef]

- Kretser, A.; Murphy, D.; Bertuzzi, S.; Abraham, T.; Allison, D.B.; Boor, K.J.; Dwyer, J.; Grantham, A.; Harris, L.J.; Hollander, R.; et al. Scientific Integrity Principles and Best Practices: Recommendations from a Scientific Integrity Consortium. Sci Eng Ethics 2019, 25, 327-355. [CrossRef]

- Khadilkar, S.S. Scientific Misconduct: A Global Concern. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2018, 68, 331-335. [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.L.; Schnell, S.; Ettinger, A.S.; Omary, M.B. Trends in NIH-supported career development funding: implications for institutions, trainees, and the future research workforce. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [CrossRef]

- Meirmans, S. How Competition for Funding Impacts Scientific Practice: Building Pre-fab Houses but no Cathedrals. Sci Eng Ethics 2024, 30, 6. [CrossRef]

- Efimov, I.R.; Flier, J.S.; George, R.P.; Krylov, A.I.; Maroja, L.S.; Schaletzky, J.; Tanzman, J.; Thompson, A. Politicizing science funding undermines public trust in science, academic freedom, and the unbiased generation of knowledge. Front Res Metr Anal 2024, 9, 1418065. [CrossRef]

- Kannan, S.; Gowri, S. Contradicting/negative results in clinical research: Why (do we get these)? Why not (get these published)? Where (to publish)? Perspect Clin Res 2014, 5, 151-153. [CrossRef]

- Zhaksylyk, A.; Zimba, O.; Yessirkepov, M.; Kocyigit, B.F. Research Integrity: Where We Are and Where We Are Heading. J Korean Med Sci 2023, 38, e405. [CrossRef]

- Resnik, D.B.; Stewart, C.N., Jr. Misconduct versus honest error and scientific disagreement. Account Res 2012, 19, 56-63. [CrossRef]

- Morgan, J. Wrongful convictions and claims of false or misleading forensic evidence. J Forensic Sci 2023, 68, 908-961. [CrossRef]

- Kruk, M.E.; Gage, A.D.; Arsenault, C.; Jordan, K.; Leslie, H.H.; Roder-DeWan, S.; Adeyi, O.; Barker, P.; Daelmans, B.; Doubova, S.V.; et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health 2018, 6, e1196-e1252. [CrossRef]

- Bullock, T.N.J. Fundamentals of Cancer Immunology and Their Application to Cancer Vaccines. Clin Transl Sci 2021, 14, 120-131. [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarek, M.; Poznanska, J.; Fechner, F.; Michalska, N.; Paszkowska, S.; Napierala, A.; Mackiewicz, A. Cancer Vaccine Therapeutics: Limitations and Effectiveness-A Literature Review. Cells 2023, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hunt, D.F.; Dunn, M.; Harrison, G.; Bailey, J. Ethical considerations in quality improvement: key questions and a practical guide. BMJ Open Qual 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Schrag, M.; Patrick, K.; Bik, E. Academic Research Integrity Investigations Must be Independent, Fair, and Timely. J Law Med Ethics 2025, 1-4. [CrossRef]

- Bavli, I. When Public Health Goes Wrong: Toward a New Concept of Public Health Error. J Law Med Ethics 2023, 51, 385-402. [CrossRef]

- Lvovs, D.; Creason, A.L.; Levine, S.S.; Noble, M.; Mahurkar, A.; White, O.; Fertig, E.J. Balancing ethical data sharing and open science for reproducible research in biomedical data science. Cell Rep Med 2025, 6, 102080. [CrossRef]

- Foster, N.D.; Benjamin, K.; Parwani, P.; Perehudoff, K. Universal Health Coverage and Social Protection: Evolution and Future Opportunities for Global Health Law and Equity. J Law Med Ethics 2025, 53, 35-39. [CrossRef]

- Nosek, B.A.; Spies, J.R.; Motyl, M. Scientific Utopia: II. Restructuring Incentives and Practices to Promote Truth Over Publishability. Perspect Psychol Sci 2012, 7, 615-631. [CrossRef]

- Miteu, G.D. Ethics in scientific research: a lens into its importance, history, and future. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2024, 86, 2395-2398. [CrossRef]

- Resnik, D.B. Is it time to revise the definition of research misconduct? Account Res 2019, 26, 123-137. [CrossRef]

- Armond, A.C.V.; Cobey, K.D.; Moher, D. Research Integrity definitions and challenges. J Clin Epidemiol 2024, 171, 111367. [CrossRef]

- Rekker, R. The nature and origins of political polarization over science. Public Underst Sci 2021, 30, 352-368. [CrossRef]

- Simundic, A.M. Bias in research. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2013, 23, 12-15. [CrossRef]

- Kaptchuk, T.J. Effect of interpretive bias on research evidence. BMJ 2003, 326, 1453-1455. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.; Chatterjee, N.; Ramanathan, A. Understanding the patterns and magnitude of life science publication Retractions in the last four decades. International Journal for Educational Integrity 2025, 21, 17. [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.; Lin, S.C. Retracted articles in scientific literature: A bibliometric analysis from 2003 to 2022 using the Web of Science. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38620. [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Pezzullo, A.M.; Cristiano, A.; Boccia, S.; Baas, J. Linking citation and retraction data reveals the demographics of scientific retractions among highly cited authors. PLoS Biol 2025, 23, e3002999. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, H.; Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Retractions, Fake Peer Reviews, and Paper Mills. J Korean Med Sci 2021, 36, e165. [CrossRef]

- Galbraith, D.W. Redrawing the frontiers in the age of post-publication review. Front Genet 2015, 6, 198. [CrossRef]

- Caron, M.M.; Lye, C.T.; Bierer, B.E.; Barnes, M. The PubPeer conundrum: Administrative challenges in research misconduct proceedings. Account Res 2024, 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Wittau, J.; Seifert, R. How to fight fake papers: a review on important information sources and steps towards solution of the problem. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2024, 397, 9281-9294. [CrossRef]

- Else, H. Biomedical paper retractions have quadrupled in 20 years - why? Nature 2024, 630, 280-281. [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.C.; Steen, R.G.; Casadevall, A. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 17028-17033. [CrossRef]

- Stretton, S.; Bramich, N.J.; Keys, J.R.; Monk, J.A.; Ely, J.A.; Haley, C.; Woolley, M.J.; Woolley, K.L. Publication misconduct and plagiarism retractions: a systematic, retrospective study. Curr Med Res Opin 2012, 28, 1575-1583. [CrossRef]

- Freijedo-Farinas, F.; Ruano-Ravina, A.; Pérez-Ríos, M.; Ross, J.; Candal-Pedreira, C. Biomedical retractions due to misconduct in Europe: characterization and trends in the last 20 years. Scientometrics 2024, 129, 2867-2882. [CrossRef]

- Godskesen, T. Fraudulent Research Falsely Attributed to Credible Researchers—An Emerging Challenge for Journals? Learned Publishing 2025, 38, e2009. [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.A.; Farouk, O. Increasing publications count by falsifying, fabricating, and misconducting research data. Is it worth it? The Egyptian Orthopaedic Journal 2024, 59, 317-319. [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, X.; Ma, X.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; He, S. Mapping retracted articles and exploring regional differences in China, 2012-2023. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0314622. [CrossRef]

- Maddi, A.; Monneau, E.; Guaspare-Cartron, C.; Gargiulo, F.; Dubois, M. The retraction gender gap: Are mixed teams more vulnerable? Quantitative Science Studies 2025, 6, 351-374. [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Makovi, K.; AlShebli, B. Characterizing the effect of retractions on publishing careers. Nat Hum Behav 2025, 9, 1134-1146. [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.C.; Casadevall, A. Retracted science and the retraction index. Infect Immun 2011, 79, 3855-3859. [CrossRef]

- van der Heyden, M.A.; van de Ven, T.; Opthof, T. Fraud and misconduct in science: the stem cell seduction: Implications for the peer-review process. Neth Heart J 2009, 17, 25-29. [CrossRef]

- Tham, W.Y. Science, interrupted: Funding delays reduce research activity but having more grants helps. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0280576. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.E. Addressing researcher fraud: retrospective, real-time, and preventive strategies-including legal points and data management that prevents fraud. Front Res Metr Anal 2024, 9, 1397649. [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.P., 3rd. Replication and Reproducibility and the Self-Correction of Science: What Can JID Innovations Do? JID Innov 2023, 3, 100188. [CrossRef]

- Reich, E.S. Former MIT biologist penalized for falsifying data. Nature 2009. [CrossRef]

- Findings of Research Misconduct. Fed Regist 2012, 77, 76041-76042.

- Bauchner, H.; Steinbrook, R.; Redberg, R.F. Research Misconduct and Medical Journals. J Law Med Ethics 2025, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Teixeira da Silva, J.A. Paper mills and on-demand publishing: Risks to the integrity of journal indexing and metrics. Med J Armed Forces India 2021, 77, 119-120. [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.Y.; Yon, D.K.; Lee, S.W.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Smith, L.; Koyanagi, A.; Solmi, M.; Carvalho, A.F.; Kim, E.; et al. Causes for Retraction in the Biomedical Literature: A Systematic Review of Studies of Retraction Notices. J Korean Med Sci 2023, 38, e333. [CrossRef]

- Elango, B. Retracted articles in the biomedical literature from Indian authors. Scientometrics 2021, 126, 3965-3981. [CrossRef]

- Hill, R.A.; Lin, S.; Grape, E.S.; Zhang, Y.; Schilling, O.S.; Voiry, D. Stories of data sharing. Nature Water 2025, 3, 7-10. [CrossRef]

- Mayo-Wilson, E.; Grant, S.; Supplee, L.; Kianersi, S.; Amin, A.; DeHaven, A.; Mellor, D. Evaluating implementation of the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) guidelines: the TRUST process for rating journal policies, procedures, and practices. Res Integr Peer Rev 2021, 6, 9. [CrossRef]

- Gierasch, L.M.; Davidson, N.O.; Rye, K.A.; Burlingame, A.L. The data must be accessible to all. J Biol Chem 2020, 295, 4371. [CrossRef]

- Resnik, D.B.; Wager, E.; Kissling, G.E. Retraction policies of top scientific journals ranked by impact factor. J Med Libr Assoc 2015, 103, 136-139. [CrossRef]

- Cromey, D.W. Avoiding twisted pixels: ethical guidelines for the appropriate use and manipulation of scientific digital images. Sci Eng Ethics 2010, 16, 639-667. [CrossRef]

- Alter, G.; Gonzalez, R. Responsible practices for data sharing. Am Psychol 2018, 73, 146-156. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.B.; Evans, N.; Hu, G.; Bouter, L. What do Retraction Notices Reveal About Institutional Investigations into Allegations Underlying Retractions? Sci Eng Ethics 2023, 29, 25. [CrossRef]

- Manca, A.; Moher, D.; Cugusi, L.; Dvir, Z.; Deriu, F. How predatory journals leak into PubMed. CMAJ 2018, 190, E1042-E1045. [CrossRef]

- Godlee, F. Dealing with editorial misconduct. BMJ 2004, 329, 1301-1302. [CrossRef]

- Thorp, H.H. Genuine images in 2024. Science 2024, 383, 7. [CrossRef]

- Jones, N. How journals are fighting back against a wave of questionable images. Nature 2024, 626, 697-698. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, J.; Woods, N.D.; Proescholdt, R.; Team, R. Reducing the Inadvertent Spread of Retracted Science: recommendations from the RISRS report. Res Integr Peer Rev 2022, 7, 6. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, C.; Boughton, S.; Faggion, C.M.; Fanelli, D.; Kaiser, K.; Schneider, J. Reducing the residue of retractions in evidence synthesis: ways to minimise inappropriate citation and use of retracted data. BMJ Evid Based Med 2024, 29, 121-126. [CrossRef]

- Briskin, J.L.; Gunsalus, C.K. Fostering Accountability: How Institutions Can Promote Research Integrity with Practical Tools and Knowledge. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 2025, 53, 67-73. [CrossRef]

- Bukusi, E.A.; Manabe, Y.C.; Zunt, J.R. Mentorship and Ethics in Global Health: Fostering Scientific Integrity and Responsible Conduct of Research. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2019, 100, 42-47. [CrossRef]

- In Clinical Data as the Basic Staple of Health Learning: Creating and Protecting a Public Good: Workshop Summary; The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health; Washington (DC), 2010.

- Gokulakrishnan, D.; Venkataraman, S. Ensuring data integrity: Best practices and strategies in pharmaceutical industry. Intelligent Pharmacy 2024. [CrossRef]

- Trueblood, J.S.; Allison, D.B.; Field, S.M.; Fishbach, A.; Gaillard, S.D.M.; Gigerenzer, G.; Holmes, W.R.; Lewandowsky, S.; Matzke, D.; Murphy, M.C.; et al. The misalignment of incentives in academic publishing and implications for journal reform. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2025, 122, e2401231121. [CrossRef]

- Lahusen, C.; Maggetti, M.; Slavkovik, M. Trust, trustworthiness and AI governance. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 20752. [CrossRef]

- Kulal, A.; Rahiman, H.U.; Suvarna, H.; Abhishek, N.; Dinesh, S. Enhancing public service delivery efficiency: Exploring the impact of AI. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 2024, 10, 100329. [CrossRef]

- Capraro, V.; Lentsch, A.; Acemoglu, D.; Akgun, S.; Akhmedova, A.; Bilancini, E.; Bonnefon, J.F.; Branas-Garza, P.; Butera, L.; Douglas, K.M.; et al. The impact of generative artificial intelligence on socioeconomic inequalities and policy making. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgae191. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, C.S.; Muntean, E.A.; Mallen, C.D.; Borovac, J.A. Data Collection Theory in Healthcare Research: The Minimum Dataset in Quantitative Studies. Clin Pract 2022, 12, 832-844. [CrossRef]

- Tarazona, S.; Arzalluz-Luque, A.; Conesa, A. Undisclosed, unmet and neglected challenges in multi-omics studies. Nat Comput Sci 2021, 1, 395-402. [CrossRef]

- Simera, I.; Moher, D.; Hirst, A.; Hoey, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med 2010, 8, 24. [CrossRef]

- Mousa, A.; Flanagan, M.; Tay, C.T.; Norman, R.J.; Costello, M.; Li, W.; Wang, R.; Teede, H.; Mol, B.W. Research Integrity in Guidelines and evIDence synthesis (RIGID): a framework for assessing research integrity in guideline development and evidence synthesis. EClinicalMedicine 2024, 74, 102717. [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Huggett, J.F. Reproducibility of biomedical research - The importance of editorial vigilance. Biomol Detect Quantif 2017, 11, 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Marusic, A.; Wager, E.; Utrobicic, A.; Rothstein, H.R.; Sambunjak, D. Interventions to prevent misconduct and promote integrity in research and publication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 4, MR000038. [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.; Spiegel, E. Guidelines for Research Data Integrity (GRDI). Sci Data 2025, 12, 95. [CrossRef]

| Year | Number of Retractions | Progress |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 11 | Beginning of digital indexing; low detection/reporting |

| 2001 | 19 | |

| 2002 | 22 | |

| 2003 | 45 | |

| 2004 | 46 | |

| 2005 | 42 | Increased awareness, more journals adopting retraction policies |

| 2006 | 86 | |

| 2007 | 83 | |

| 2008 | 165 | |

| 2009 | 235 | |

| 2010 | 241 | Surge due to misconduct cases (e.g., Stapel, Boldt) |

| 2011 | 379 | |

| 2012 | 437 | |

| 2013 | 497 | |

| 2014 | 396 | |

| 2015 | 561 | Retraction Watch gains visibility; journal standards improving |

| 2016 | 571 | |

| 2017 | 442 | |

| 2018 | 564 | |

| 2019 | 661 | More active journal corrections and scrutiny |

| 2020 | 1015 | COVID-19 pandemic led to rapid publications and scrutiny |

| 2021 | 1556 | Highest yearly retraction rate, many COVID-19 related |

| 2022 | 1916 | Continued rise, automation and AI tools detecting fraud |

| 2023 | 1974 | Predatory journals, fake peer review, and data fabrication flagged |

| 2024 | 2778 | |

| 2025 (estimated) | 4058 | The rise of artificial intelligence |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).