1. Introduction

Single-cell analysis can reveal the molecular characteristics and functional properties of individual cells, providing crucial insights for studying cellular heterogeneity[

1], cell-cell interactions[

2], and disease response mechanisms[

3]. Multiple analytical methods have emerged in this field, including flow cytometry[

4,

5], single-cell sequencing and multi-omics technologies[

6], and single-cell imaging analysis. Single-cell imaging, with a particular emphasis on mass spectrometry imaging (MSI), establishes a connection between molecular characteristics and cellular functions by visually mapping the distribution and dynamics of molecules. In contrast to conventional imaging techniques that rely on probes or labels, mass spectrometry imaging utilizes a laser or ion beam to ionize biomolecules, which are subsequently identified by a mass spectrometer based on their mass-to-charge ratio. This technique, through scanning imaging of samples[

7], maintains the cell's natural state by eliminating the need for exogenous labeling, thereby preventing cytotoxicity and signal interference[

8]. Furthermore, it facilitates the direct detection of endogenous molecules such as lipids and metabolites, enabling precise capture of molecular alterations in both physiological and pathological processes, and thereby providing robust evidence for the elucidation of cellular functions[

9].

Among the MSI techniques, ToF-SIMS is a widely utilized technique for the study of single cells, as it can simultaneously acquire comprehensive mass spectrometry data and corresponding two-dimensional molecular distribution images at the single-cell level[

10]. Compared to other techniques, ToF-SIMS enables direct, label-free detection of endogenous metabolites, lipids, inorganic ions, and other molecules distributed on and within individual cells in situ. Furthermore, ToF-SIMS offers broad molecular coverage and rapid data acquisition, capable of detecting thousands of ion signals simultaneously. Leveraging these advantages, ToF-SIMS can reveal minute molecular changes in individual cells during metabolic pathways, drug responses, or pathological states. This makes it a crucial research tool for exploring disease mechanisms[

11], drug action modes[

12], and cellular functional states. However, current ToF-SIMS single-cell analysis methods still have certain limitations. The data collection process involves large volumes and complex analytical workflows[

11]; every step of the experimental procedure—from sample preparation to mass spectrometry imaging acquisition, followed by data preprocessing and analysis—can significantly impact the accuracy and reproducibility of analytical results. For instance, cells cultured on the same silicon wafer may exhibit substantial variations in metabolomic data between those located in the central region and those at the periphery. Furthermore, when cells are cultured in different batches, the discrepancies observed across different silicon wafers may be even more pronounced. In addition, differences in ion yield can also lead to non-biological variations in inter-cell metabolic information, thereby reducing data reliability[

13]. Therefore, performing effective calibration analysis on ToF-SIMS single-cell metabolomics data is a critical step in enhancing analytical stability and result comparability.

In large-scale untargeted metabolomics studies, several established correction methods have been proposed and successfully applied, primarily categorized into three types: correction based on quality control samples, correction based on internal standard compounds, and statistical correction[

14]. In large-scale, multi-batch liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)-based untargeted metabolomics studies involving diverse populations, these methods significantly enhance data comparability and stability by addressing systematic biases caused by signal drift, instrument variability, and batch effects[

15]. For instance, the recently proposed Norm-ISW-SVR method combines internal standard compounds with a support vector regression (Norm-SVR) algorithm[

16], demonstrating exceptional efficacy by maintaining high data reproducibility even at extremely low quality control (QC) frequencies. This strategy is not only applicable to traditional LC-MS platforms but also provides innovative insights for data correction in other mass spectrometry technologies.

Therefore, this study introduces a Norm-SVR-corrected approach for single-cell metabolomics analysis in ToF-SIMS. By implementing Norm-SVR correction on single-cell metabolomics data across various acquisition regions and batches, we demonstrate that, in comparison to the traditional ToF-SIMS correction method utilizing total area/pixel points, Norm-SVR correction significantly mitigates batch effects and inter-cell variability. This enhances the reliability of ToF-SIMS for single-cell metabolomics and offers a dependable correction approach for future mass spectrometry imaging techniques in single-cell analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

Prior to the experiment, polished silicon wafers (cut with a diamond saw to approximately 1 cm × 1 cm) were ultrasonically cleaned for 10 minutes each in methanol, acetone, and anhydrous ethanol, followed by two rinses in each solvent. The wafers were then air-dried at room temperature and stored in sealed test tubes for later use.

Human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells were provided by the Cell Resource Center of the Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences & Peking Union Medical College. A549 cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (SIGMA) and 1% double antibiotics at 37℃ and 5% CO2. When cell density reached approximately 80%, cells were washed twice with PBS buffer, treated with 0.25% trypsin for 2 minutes to digest, then digested with DMEM complete medium to terminate digestion. Cells were resuspended by pipetting to form a cell suspension. A549 cells were seeded onto Si-coated culture dishes and allowed to adhere overnight for 12 hours before undergoing fixation and drying.

2.2. Sample Preparation

Remove the silicon wafer from the culture medium and vertically immerse it in PBS for approximately 2 seconds. Rinse three times. Subsequently, immerse the wafer vertically into 0.15 M ammonium formate solution (AF) for approximately 30 s. Remove vertically and blot excess AF with absorbent paper. Under nitrogen atmosphere, manually immerse the wafer into the cryogenic agent isopentane (pre-cooled with liquid nitrogen) for rapid freezing. Remove steadily and transfer to a pre-cooled container under nitrogen atmosphere[

17]. Place the sample-containing container in a freeze-dryer overnight for 12 hours at -55℃ and 10E-3 mbar pressure. Subsequently, gradually heat the sample until it reaches room temperature to further volatilize residual isopentane solvent. Immediately transfer the dried sample to the ToF-SIMS for scanning.

2.3. ToF-SIMS Data Acquisition

ToF-SIMS measurements were carried out on a ToF-SIMS V instrument (ION-TOF GmbH, Münster, Germany). The cells were analyzed in an analysis-sputtering mode, employing a 30 KeV Bi3+ primary ion beam for the generation of mass spectrometry images, and a 10 KeV Ar1700+ sputtering beam to eliminate any contamination or chemical damage induced by the Bi3+ beam on the sample surface. In a spatial resolution of approximately 300 nm, the beam current for Bi3+ ions is 0.17 pA and for Ar1700+ ions is 8.5 nA. Cycle time 100 us. The sputtering area was 500 × 500 µm2,with the Bi3+ analysis beam scanned 350 × 350 µm2 with 256 × 256 pixels within the central area of the sputtering region. Non-interlaced mode was applied and the parameters are as follows: analysis with 2 scans, sputtering with 1 scan, and a pause of 0.8 s. This cycle was iteratively repeated until the complete removal of all cells by sputtering. The accumulated data were subsequently compiled and presented as a final image. To mitigate the charge accumulation on the sample surface, a low-energy electron gun is employed.

2.4. Data Analysis

The mass spectra were processed using IONTOF SurfaceLab 7.0. The peak calibration was performed by C−、O−、OH−、C2H−、PO3− and C16H31O2− in negative ion mode, and C+, CH+, CH3+, C2H3+, C3H5+, C5H12N+ and C5H15PNO4+ in positive ion mode. A selection of mass spectrum peaks with signal exceeding 1,000 counts and SNR greater than 3.0 and the mass range is 0-824 Da. Regions of interest (ROIs) were identified by applying a threshold based on the phospholipid fragment at m/z 184 in the positive ion mode and the phosphate group at m/z 79 in the negative ion mode. The relative signal intensity of individual cells was quantified by normalizing the total ion count across all pixels within each cell. Statistical processing and analysis of the data obtained from single-cell mass spectrometry were performed using R version 4.3.2.

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of a Norm-SVR Data Correction Method for ToF-SIMS Single-Cell Mass Spectrometry Imaging.

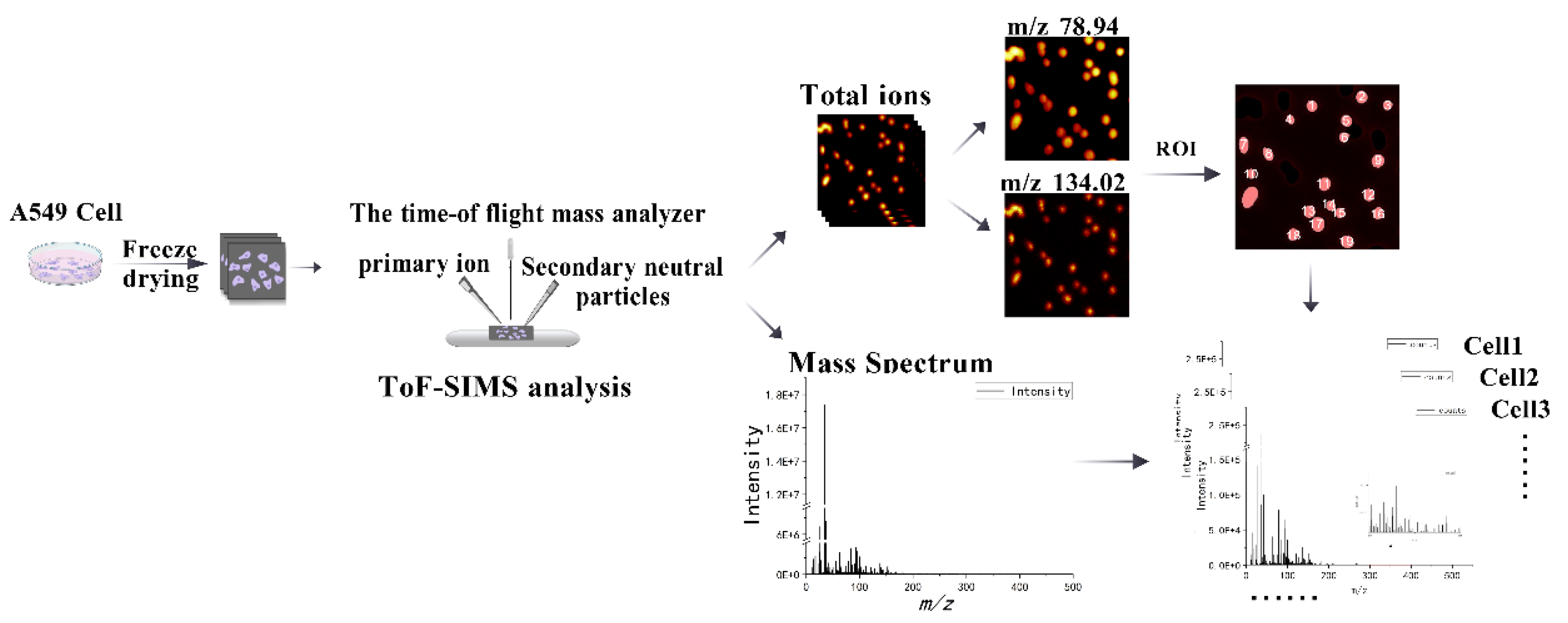

Using our previously established single-cell sampling methodology for ToF-SIMS[

17], we cultured A549 cells to an appropriate density and prepared single-cell samples via freeze-drying. Following data acquisition using the ToF-SIMS ablation-analysis mode, we obtained ion images and mass spectrometry data. Subsequently, regions of interest (ROIs) and mass spectrometry data were extracted from individual cells within these ion images, as shown in

Figure 1. Utilizing imaging spectra of phosphate ions (

m/z 78.94) and adenine ion fragments (

m/z 134.02) as reference markers[

17,

18], we defined cell dimensions and delineated cell boundaries. The ROIs for individual cells in the total ion image were sequentially analyzed from left to right and top to bottom. This sequence was employed to organize the single-cell mass spectral data, which was then extracted and compiled for further analysis. Preliminary examination of the total ion data indicated that even single cells originating from the same sample and silicon chip exhibited significant separation in principal component analysis (PCA) space, attributable to variations in collection areas. This observed spatial clustering did not stem from genuine biological differences but rather suggested that the collection location might introduce systematic bias, potentially obscuring biological variations among cells. Therefore, we employed the Support Vector Regression (Norm-SVR) method, a widely recognized technique for large-scale data correction in the domain of non-targeted metabolomics. Drawing upon prior research[

19,

20] that utilized "cell-sized blank regions of interest" in data analysis, we selected cells of similar size and consistent collection sequence intervals as QC samples throughout the analytical process. The ratio of single-cell samples to QC samples was maintained at approximately 4:1. This methodology facilitates the concurrent execution of background subtraction, quality calibration, and instrument monitoring within a single acquisition, obviating the need for internal standards or additional substrates.

3.2. Norm-SVR Correction on Single-Cell Metabolomics Data Across Various Acquisition Regions

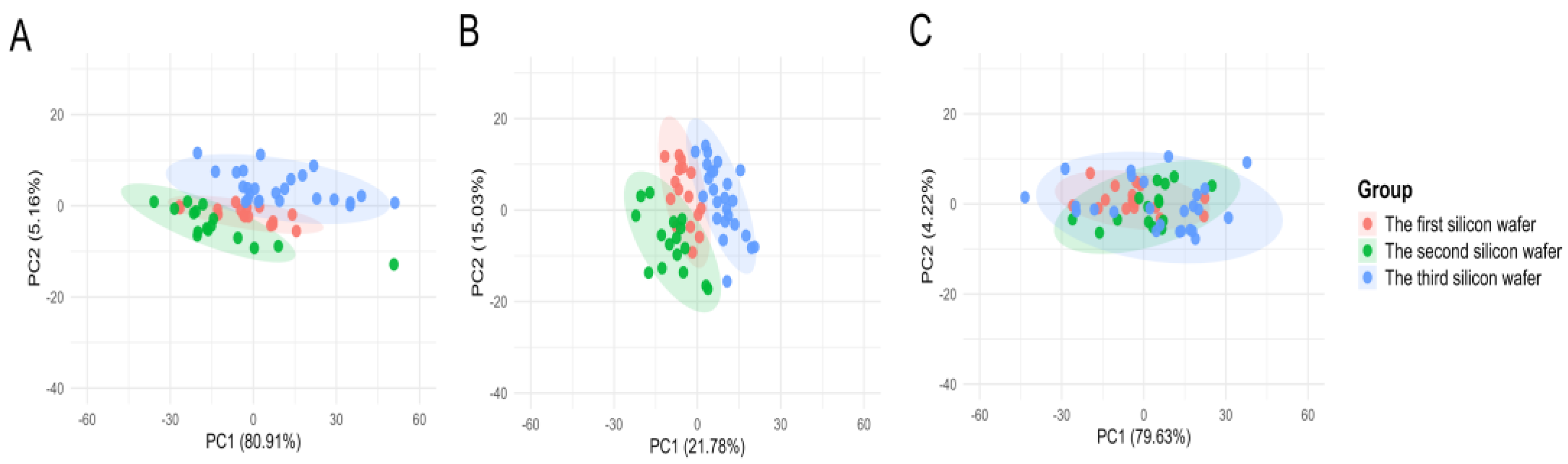

To assess the suitability of the commonly employed data correction method, Norm-SVR, in the context of ToF-SIMS single-cell mass spectrometry imaging analysis within the field of metabolomics, this study initially validated the approach using single-cell data obtained from three distinct collection points on a single silicon wafer sample, encompassing a total of 56 single cells.

Figure S1 illustrates the spatial distribution of the three sampling points on the same silicon wafer, along with the corresponding ion imaging maps and single-cell region of interest (ROI) results. During analysis, 457 characteristic ion peaks were identified and filtered according to unified screening criteria. During the analysis, 457 feature ion peaks were identified and screened according to uniform selection criteria. To evaluate the efficacy of Norm-SVR correction, the study utilized the widely adopted data processing technique of total ion intensity normalization as a benchmark for method performance. Preliminary comparative analysis was conducted using Principal PCA on raw single-cell and QC data, total ion intensity normalized data, and Norm-SVR-corrected data, as depicted in

Figure 2. The PCA results demonstrate clear distinctions: under both raw data conditions and Total Area/Pixels normalization, cell samples were grouped into three distinct clusters corresponding to their respective sampling locations. In the unprocessed raw data, non-biological variation associated with sampling sites constituted 80.91% (

Figure 2A), significantly surpassing the biological variation, which was 5.16%. This discrepancy obscured genuine metabolic differences among the cells. In contrast, the Total Ion Count normalized data showed that non-biological variation was comparable to biological variation, yet it remained spatially distributed according to the sampling locations. Following Support Vector Regression (Norm-SVR) correction, cell samples from the three sampling sites were thoroughly intermingled across groups within the PCA space.

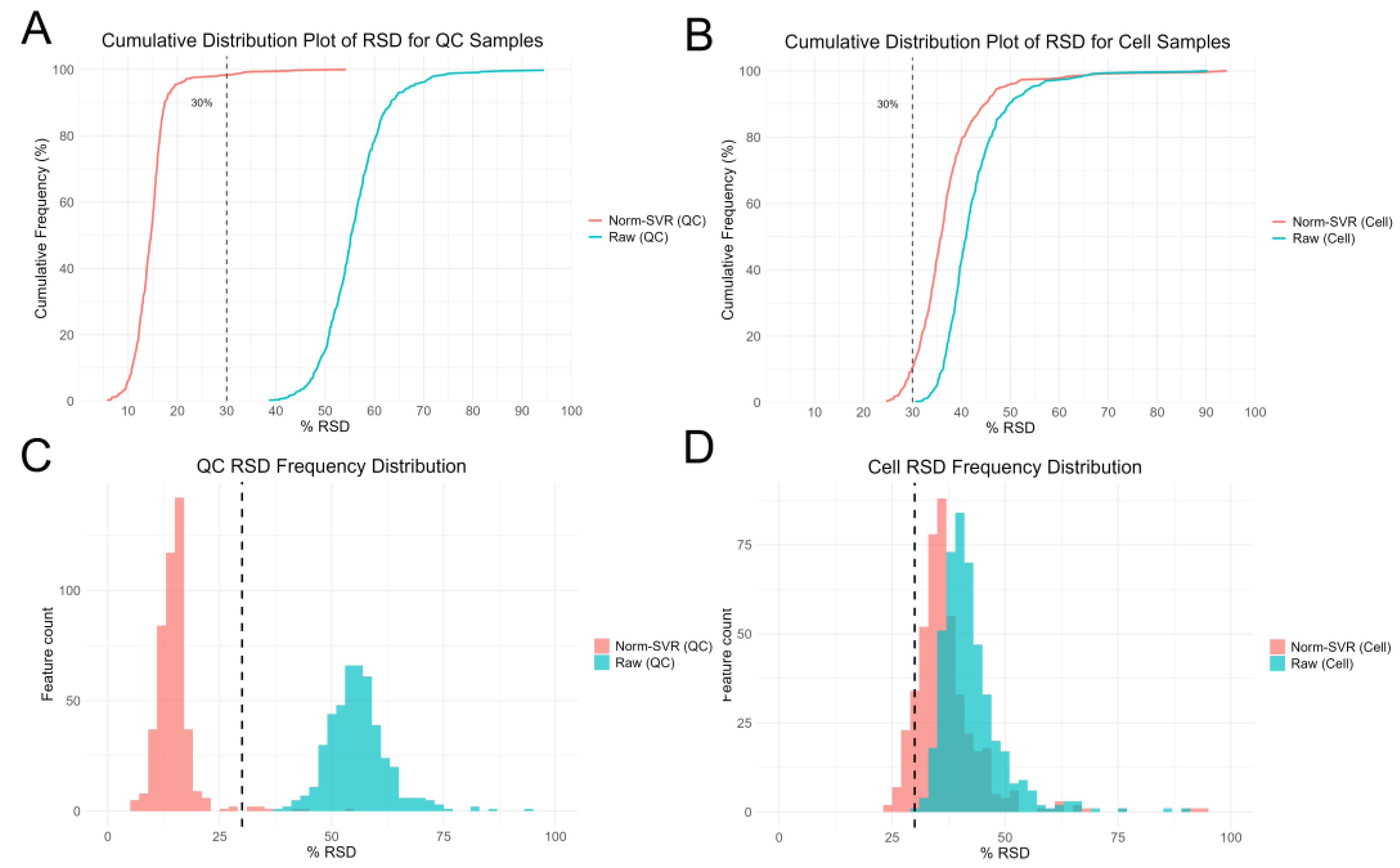

To further evaluate the impact of SVR processing on ToF-SIMS single-cell metabolomics data, we performed RSD analysis on both raw and Norm-SVRcorrected data (

Figure 3). The results reveal that the RSD distribution of raw data exhibits high dispersion in both QC and cell samples, indicating substantial inter-cell variability in uncorrected data. Specifically, the RSD values for most ion signals exceeded 50%, indicating significant non-biological variability in the data, potentially stemming from differences in sample collection locations. In contrast, after SVR correction, the RSD distribution of QC sample feature ions changed markedly: 86% of feature ions had RSD < 30%, demonstrating excellent Norm-SVR correction efficacy for QC samples and significantly reducing data variability. Similarly, compared to raw data, the RSD distribution in the Norm-SVR corrected cell samples exhibited a flatter profile. This indicates more uniform RSD values in processed data, with a concentration of feature ions in the lower RSD range (approximately 0-30%). The frequency rapidly decreased as RSD values increased, revealing a distribution bias toward smaller RSD values. Overall, the proportion of ion signals with RSD values below 30% markedly increased, while those exceeding 50% substantially decreased. This demonstrates that SVR correction effectively mitigates systematic errors arising from varying acquisition locations, substantially enhancing data stability and reliability. Through this approach, Norm-SVR homogenizes the RSD distribution across individual cells, enabling subsequent data comparisons and analyses to accurately reflect genuine biological differences between cells while eliminating non-biological variability stemming from sampling location differences. In summary, the Norm-SVR data correction method is applicable for processing ToF-SIMS single-cell data and effectively mitigates the impact of non-biological factors on measurement errors.

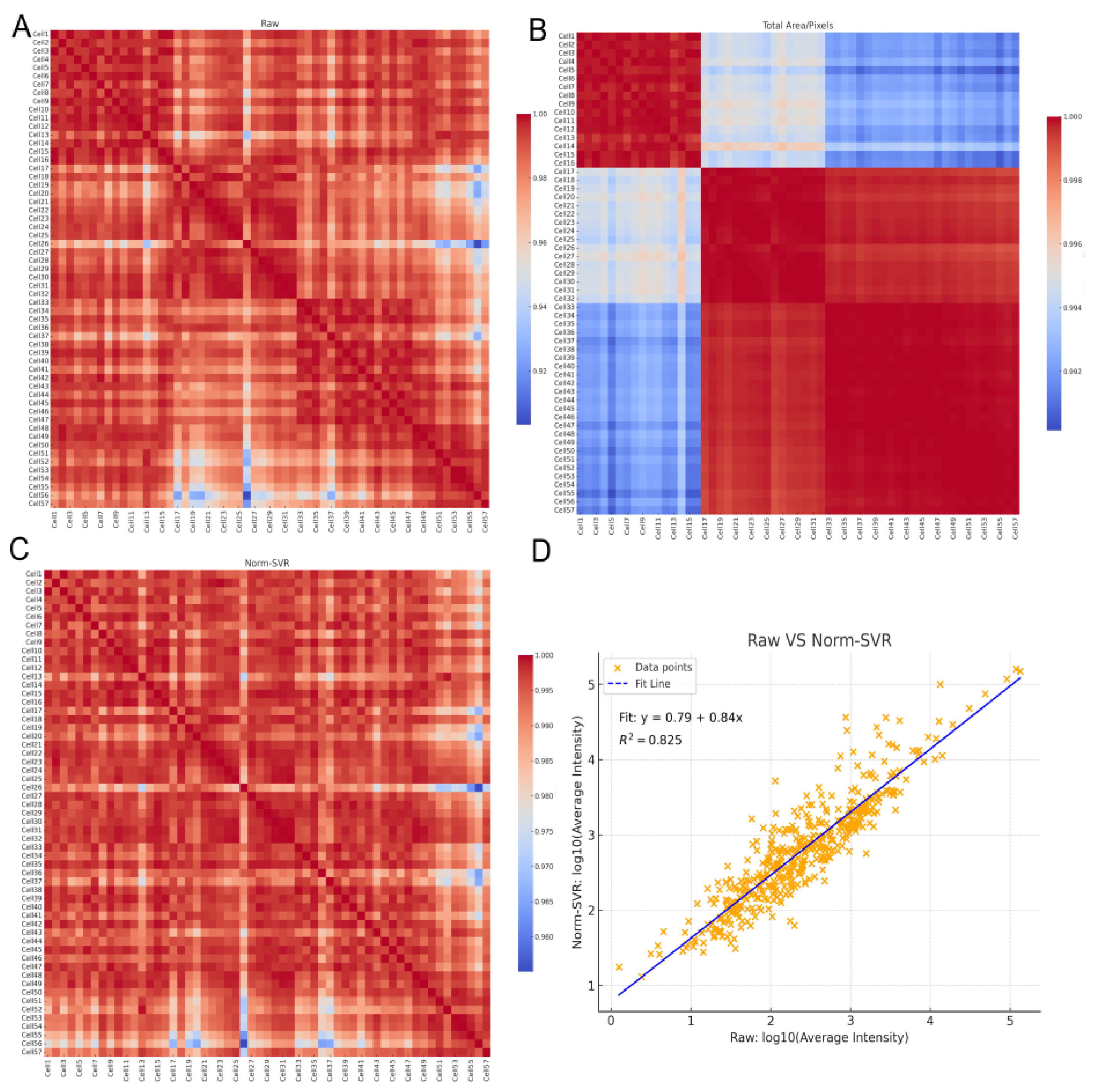

To further quantify the impact of various processing methods on inter-sample consistency, we computed the Pearson correlation coefficients for each sample pair using the Raw, Total Area/Pixels, and Norm-SVR datasets, subsequently visualizing these correlations as heatmaps. Additionally, we generated a scatter plot of the log₁₀-transformed average intensities (comparing Raw data with Norm-SVR data) to assess linear consistency at the sample level. In the Raw dataset, the correlation structure was predominantly influenced by acquisition points, with samples collected from identical locations exhibiting high correlation, whereas correlations between samples from different acquisition points were significantly diminished, resulting in a distinct "blocky" pattern. This pattern corroborated previous PCA findings, indicating that non-biological variations were still predominant. Following normalization by Total Area/Pixels, there was a slight improvement in overall correlations; however, pronounced acquisition-dependent boundaries persisted, suggesting that systematic biases were only partially mitigated.

Figure 4.

Comparison of sample correlations and signal consistency before and after normalization. (A–C) Pearson correlation heatmaps (sample × sample) of single-cell ToF-SIMS data under three processing modes: (A) Raw, (B) Total Area/Pixels, and (C)Norm-SVR. Samples are ordered by cell index, with higher uniformity (yellow color) indicating improved signal consistency among samples. (D) Linear relationships between log₁₀ mean intensities of Raw versus Norm-SVR in cell samples. The strong correlation (R² = 0.825) between Raw and Norm-SVR demonstrates that normalization effectively preserves true biological intensity relationships while reducing non-biological variability.

Figure 4.

Comparison of sample correlations and signal consistency before and after normalization. (A–C) Pearson correlation heatmaps (sample × sample) of single-cell ToF-SIMS data under three processing modes: (A) Raw, (B) Total Area/Pixels, and (C)Norm-SVR. Samples are ordered by cell index, with higher uniformity (yellow color) indicating improved signal consistency among samples. (D) Linear relationships between log₁₀ mean intensities of Raw versus Norm-SVR in cell samples. The strong correlation (R² = 0.825) between Raw and Norm-SVR demonstrates that normalization effectively preserves true biological intensity relationships while reducing non-biological variability.

Following the application of Norm-SVR correction, the overall correlation experienced a significant increase and exhibited a spatially heterogeneous distribution across acquisition points. The heatmap revealed a more uniform and elevated correlation distribution, with samples no longer clustering according to acquisition position. Furthermore, an analysis of the sample mean intensities for both Raw and Norm-SVR data revealed a stable linear relationship, with the majority of sample points aligning closely with the regression line. This indicates that Norm-SVR effectively reduced non-biological variations, such as those related to acquisition location or batch, while largely preserving the relative intensity order among samples. As a result, this establishes a more dependable basis for future comparisons of biological differences. In summary, the correlation heatmaps and method consistency analysis validate the findings of the preceding PCA results. Notably, when contrasted with Total Area/Pixels, Norm-SVR exhibits a superior capacity to improve consistency across acquisition points. This method effectively reduces non-biological variations while maintaining the comparability of biological signals, thus providing a solid data foundation for subsequent differential ion screening and pathway interpretation.

3.3. Evaluation of Norm-SVR for Batch-Effect Correction.

In large-scale ToF-SIMS single-cell experiments, systematic errors can easily arise due to batch differences, such as variations in sample preparation time, instrument fluctuations, and subtle temperature changes during freeze-drying. To address this issue, our study utilized A549 single-cell data from three distinct experimental batches, each separated by a 7-day interval to allow for natural fluctuations in instrument status. This approach was designed to assess the cross-batch correction capability of the Norm-SVR method. Each batch was prepared and data were collected using identical procedures, ensuring that all experimental conditions were consistent except for the batch itself. Across the three batches, we obtained a total of 156 single-cell samples and 45 QC samples, with each batch contributing 50-70 single-cell samples and 15 QC samples. In

Figure S2 of the

Supplementary Materials, we present ion imaging maps and single-cell ROI results at nine sampling points across three silicon wafers.

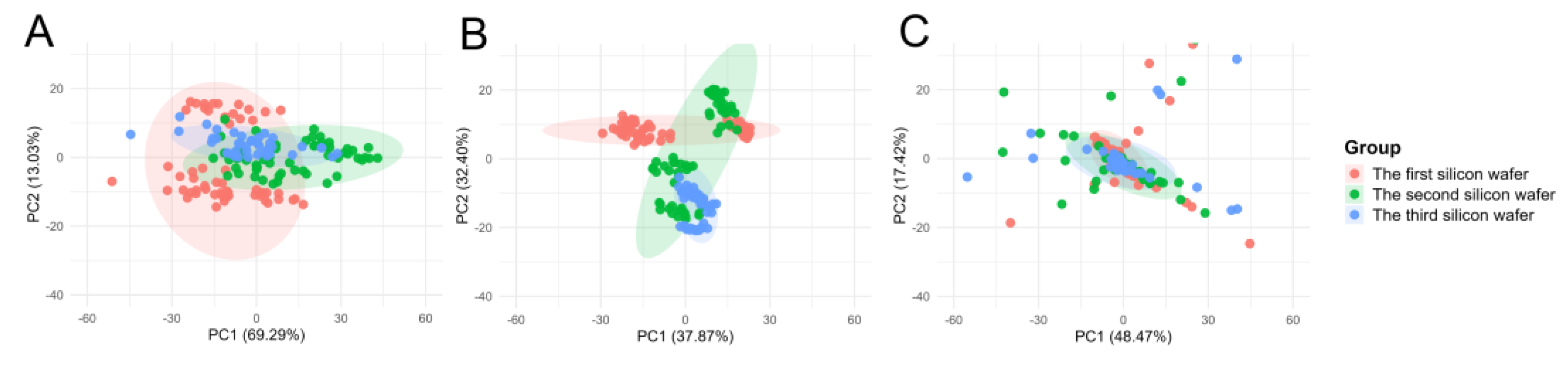

The results of the PCA indicated that, in the uncorrected raw data, the cell samples from the three batches formed distinct clusters, with inter-batch distances significantly exceeding the intra-batch dispersion of cells. Following normalization using Total Area/Pixels, the degree of separation between batches was only marginally reduced, with the first principal component (PC1) still accounting for over 70.4% of the batch differences (

Figure 5B). However, after correction using Norm-SVR, the cell samples from the three batches exhibited substantial overlap within the PCA space, resulting in the complete disappearance of batch boundaries (

Figure 5C). This outcome indicates that the batch effect was effectively eliminated.

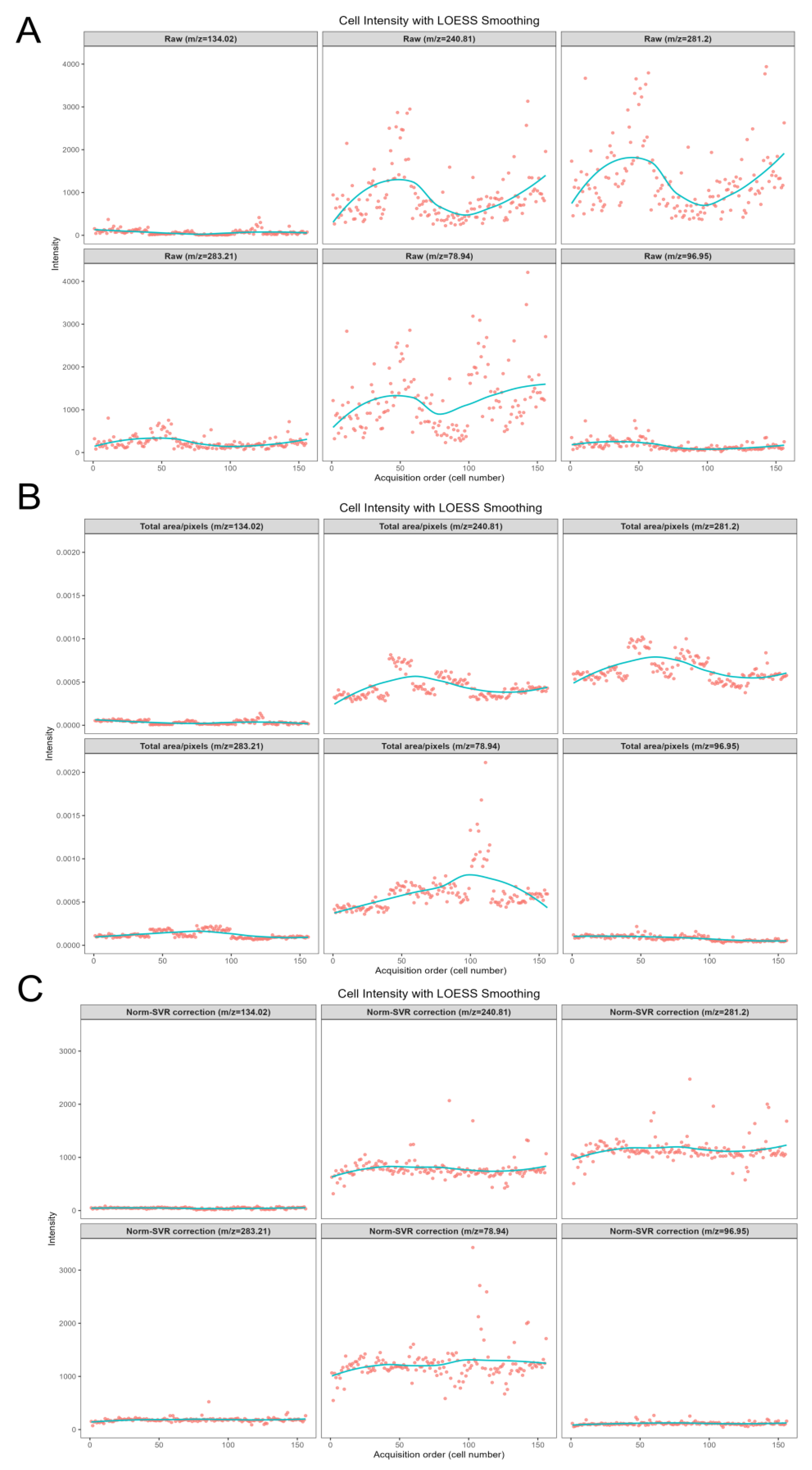

To further examine the correction scenarios associated with various characteristic ions of metabolites,

Figure 6 concentrates on the analysis of five representative negative ions (

m/z 78.944, 96.948, 240.814, 281.197, 283.214) within the negative ion mode. This figure systematically compares the impact of three data processing methods—namely Raw (original data), Total Area/Pixels, and Norm-SVR—on the stability of ion signal intensity. Concurrently, it investigates the correlation between the types of characteristic ions and the effectiveness of the correction.

Regarding signal stability, the raw data exhibited significant deficiencies. The signal intensity of all target ions demonstrated irregular fluctuations. For instance, the signal intensity of m/z 78.944, presumed to be a characteristic ion of phosphate groups, was notably influenced by non-biological factors such as ion beam stability and sample surface charge accumulation. Additionally, the raw signal distribution of m/z 281.197 (C18H33O2-, an ion characteristic of unsaturated fatty acids) was dispersed, with substantial signal intensity variations observed between adjacent cells. The Total Area/Pixels normalization process not only failed to enhance stability but also potentially increased the RSD of the target ions. The scatter trend line of m/z 240.814 (C14H27O4-, a lipid metabolite ion) exhibited a "zigzag" fluctuation pattern. Merely scaling the signal intensity by total ion count did not eliminate ion yield discrepancies and resulted in some distortion of ion signals. However, following Norm-SVR correction, the signal fluctuations of all target ions were effectively mitigated.

When examining the correlation between characteristic ion types and calibration effectiveness, significant corrections were observed for phosphate ions and other small-molecule inorganic ions (m/z 78.944, 96.948). This marked reduction is attributed to their heightened sensitivity to fluctuations in instrument parameters. Norm-SVR technology effectively compensates for real-time variations in instrument status by modeling systematic errors in quality control samples. In contrast, the RSD variation trend for lipid macromolecular ions (m/z 240.814, 281.197, 283.214) was more pronounced than that of small-molecule ions, significantly outperforming traditional total ion intensity normalization methods. This discrepancy relates to the spatial distribution characteristics of lipid molecules, which are unevenly distributed across cell membranes and thus more susceptible to variations in ion beam sputtering efficiency. The nonlinear correction capability of Norm-SVR partially mitigates signal bias caused by spatial heterogeneity, whereas linear methods cannot effectively address this complexity.

As illustrated in

Figure 5, the Norm-SVR method effectively transforms the sample structure across batches from a "batch aggregation" to an "overall mixture" configuration. This transformation is evidenced by the centralization and compactness of QC samples, indicating a suppression of non-biological fluctuations. Furthermore,

Figure 6 highlights an enhancement in stability at the ionic level, particularly for small molecule inorganic and phosphate-based ions, which are more susceptible to variations in surface and instrument conditions. Additionally, lipid ions exhibit continuous improvement. These findings provide a robust foundation for subsequent analyses of characteristic ion changes within the metabolic profiles of large batches of single cells.

4. Conclusions

This study introduces and validates a Norm-SVR data correction method specifically designed for ToF-SIMS single-cell mass spectrometry imaging. The method addresses non-biological systematic biases, such as spatial location and batch effects, which can obscure genuine metabolic heterogeneity in single-cell samples. By employing phosphate and adenine fragment ions as spatial references and incorporating cell-sized quality control samples for multi-functional calibration, Norm-SVR demonstrated superior performance compared to TIC normalization across various validation experiments. The method effectively eliminated location-based clustering in PCA, reduced signal RSD for the majority of ions, concentrated signals within low-RSD ranges, and preserved intrinsic biological intensity correlations. In tests for batch effects, Norm-SVR successfully eradicated batch-dependent grouping and enhanced signal stability for both small-molecule inorganic ions and lipid metabolites. Overall, Norm-SVR offers a robust, standard-free approach to improve data comparability across different locations and batches while maintaining authentic biological variation, thereby establishing a critical foundation for reliable downstream single-cell metabolomics analysis through ToF-SIMS imaging.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, MingRu Liu; Conceptualization, Hongzhe Ma; Software, Mingru Liu; Validation, Xiang Fang; Visualization, Yanhua Chen; Writing – Review & Editing, Zhaoying Wang, Xiaoxiao Ma; Supervision, Zhaoying Wang; Project Administration, Zhaoying Wang.

Funding

We are thankful for the financial support from the National Key Research and Development (Grant No. 2022YFC3401900), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22104160).

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting this study are original experimental data from the first author’s Master’s thesis at Minzu University of China (MUC), currently not publicly archived. Temporary restricted access follows MUC’s regulations on postgraduate thesis data management and the need for subsequent extended research. The complete dataset, including raw data (e.g., mass spectrometry imaging files, sample pretreatment records) and processed data, is standardized and preserved by the corresponding author. After the first author completes thesis defense and complies with MUC’s data release rules, qualified researchers may request the data from the corresponding author, Zhaoying Wang (E-mail:

zhaoying.wang@muc.edu.cn). Customized data processing codes are also available upon request to ensure research reproducibility.

Acknowledgments

Gratitude is extended to the Key Laboratory of Mass Spectrometry Imaging and Metabolomics (MUC) for providing experimental platforms and technical support, ensuring smooth progress of core experiments.Special thanks go to the Department of Precision Instrument, Tsinghua University, for their support in instrument debugging and technical consultation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Tang, L.; Zhang, J.; Shao, Y.; Wei, Y.; Li, Y.; Tian, K.; Yan, X.; Feng, C.; Zhang, Q.C. Joint analysis of chromatin accessibility and gene expression in the same single cells reveals cancer-specific regulatory programs. Cell Systems 2025, 16, 101266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Shi, M.; Li, M.; Qin, S.; Miao, D.; Bai, Y. Dynamic single-cell metabolomics reveals cell-cell interaction between tumor cells and macrophages. Nature communications 2025, 16, 4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bubis, J.A.; Arrey, T.N.; Damoc, E.; Delanghe, B.; Slovakova, J.; Sommer, T.M.; Kagawa, H.; Pichler, P.; Rivron, N.; Mechtler, K.; et al. Challenging the Astral mass analyzer to quantify up to 5,300 proteins per single cell at unseen accuracy to uncover cellular heterogeneity. Nat Methods 2025, 22, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roebroek, T.; Van Roy, W.; Roth, S.; Chacon Orellana, L.; Luo, Z.; El Jerrari, Y.; Arnett, C.; Claes, K.; Ha, S.; Jans, K.; et al. Continuous, Label-Free Phenotyping of Single Cells Based on Antibody Interaction Profiling in Microfluidic Channels. Anal Chem 2025, 97, 8975–8983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Yang, P.; Gao, W.; Dai, Y.; Gao, J.; Jin, Q. Label-free and simultaneous mechanical and electrical characterization of single hybridoma cell using microfluidic impedance cytometry measurement system. Measurement 2025, 253, 117462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Huang, Z.; Xu, L.; Fan, Y.; Ping, J.; Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Yu, C.; Wang, Q.; Song, T.; et al. UDA-seq: Universal droplet microfluidics-based combinatorial indexing for massive-scale multimodal single-cell sequencing. Affiliations Department of Bioengineering, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA. Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, USA. Department of Molecular 2025, 22, 1199–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Shi, X.; Lu, H.; Li, L. Delineation of Subcellular Molecular Heterogeneity in Single Cells via Ultralow-Flow-Rate Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry Imaging. Department of Chemistry, Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania 16802, United States;Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States;Ce 2025, 97, 9985–9991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Geng, H.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Wang, X.; Sun, C. Integrating spatial omics and single-cell mass spectrometry imaging reveals tumor-host metabolic interplay in hepatocellular carcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2025, 122, e2505789122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Ge, S.; Liao, T.; Yuan, M.; Qian, W.; Chen, Q.; Liang, W.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, Q.; Ju, Z.; et al. Integrative single-cell metabolomics and phenotypic profiling reveals metabolic heterogeneity of cellular oxidation and senescence. Nature communications 2025, 16, 2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Abliz, Z. Dual mass spectrometry imaging and spatial metabolomics to investigate the metabolism and nephrotoxicity of nitidine chloride. Journal of Pharmaceutical Analysis 2024, 14, 100944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, T.; Allam, M.; Cai, S.; Henderson, W.; Yueh, B.; Garipcan, A.; Ievlev, A.V.; Afkarian, M.; Beyaz, S.; Coskun, A.F. Single-cell spatial metabolomics with cell-type specific protein profiling for tissue systems biology. Nature communications 2023, 14, 8260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jungnickel, H.; Laux, P.; Luch, A. Time-of-Flight Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry (ToF-SIMS): A New Tool for the Analysis of Toxicological Effects on Single Cell Level. Toxics 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.A.; Graham, D.J.; Castner, D.G. ToF-SIMS depth profiling of cells: Z-correction, 3D imaging, and sputter rate of individual NIH/3T3 fibroblasts. Anal Chem 2012, 84, 4880–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terlier, T.; Lee, J.; Lee, K.; Lee, Y. Improvement of the Correlative AFM and ToF-SIMS Approach Using an Empirical Sputter Model for 3D Chemical Characterization. Department of Chemistry, Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania 16802, United States;Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States;Ce 2018, 90, 1701–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belu, A.M.; Graham, D.J.; Castner, D.G. Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry: Techniques and applications for the characterization of biomaterial surfaces. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3635–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Yang, F.; Chen, Y.; Xu, J.; He, J.; Zhang, R.; Abliz, Z. Norm ISWSVR: A Data Integration and Normalization Approach for Large-Scale Metabolomics. Department of Chemistry, Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania 16802, United States;Department of Environmental and Occupational Health, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260, United States;Ce 2022, 94, 7500–7509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Liu, M.; Qi, Y.; Ma, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Abliz, Z. A laboratory-friendly protocol for freeze-drying sample preparation in ToF-SIMS single-cell imaging. Front. Chem. 2025, 13–1523712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-Y.; Harbers, G.M.; Grainger, D.W.; Gamble, L.J.; Castner, D.G. Fluorescence, XPS, and TOF-SIMS Surface Chemical State Image Analysis of DNA Microarrays. Affiliation Ministry of Education (MOE) Key Laboratory of Spectrochemical Analysis and Instrumentation, College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, China 2007, 129, 9429–9438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passarelli, M.K.; Winograd, N. Lipid imaging with time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids 2011, 1811, 976–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amos, M.; Young, P.J.; Hosking, J.S.; Lamarque, J.F.; Abraham, N.L.; Akiyoshi, H.; Archibald, A.T.; Bekki, S.; Deushi, M.; Jöckel, P.; et al. Projecting ozone hole recovery using an ensemble of chemistryΓÇôclimate models weighted by model performance and independence. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020, 20, 9961–9977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).