Submitted:

25 November 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Prevent metastasis

- Sensitize circulating cancer cells to apoptosis

- Improve outcomes in advanced cancers

2. Historical Background

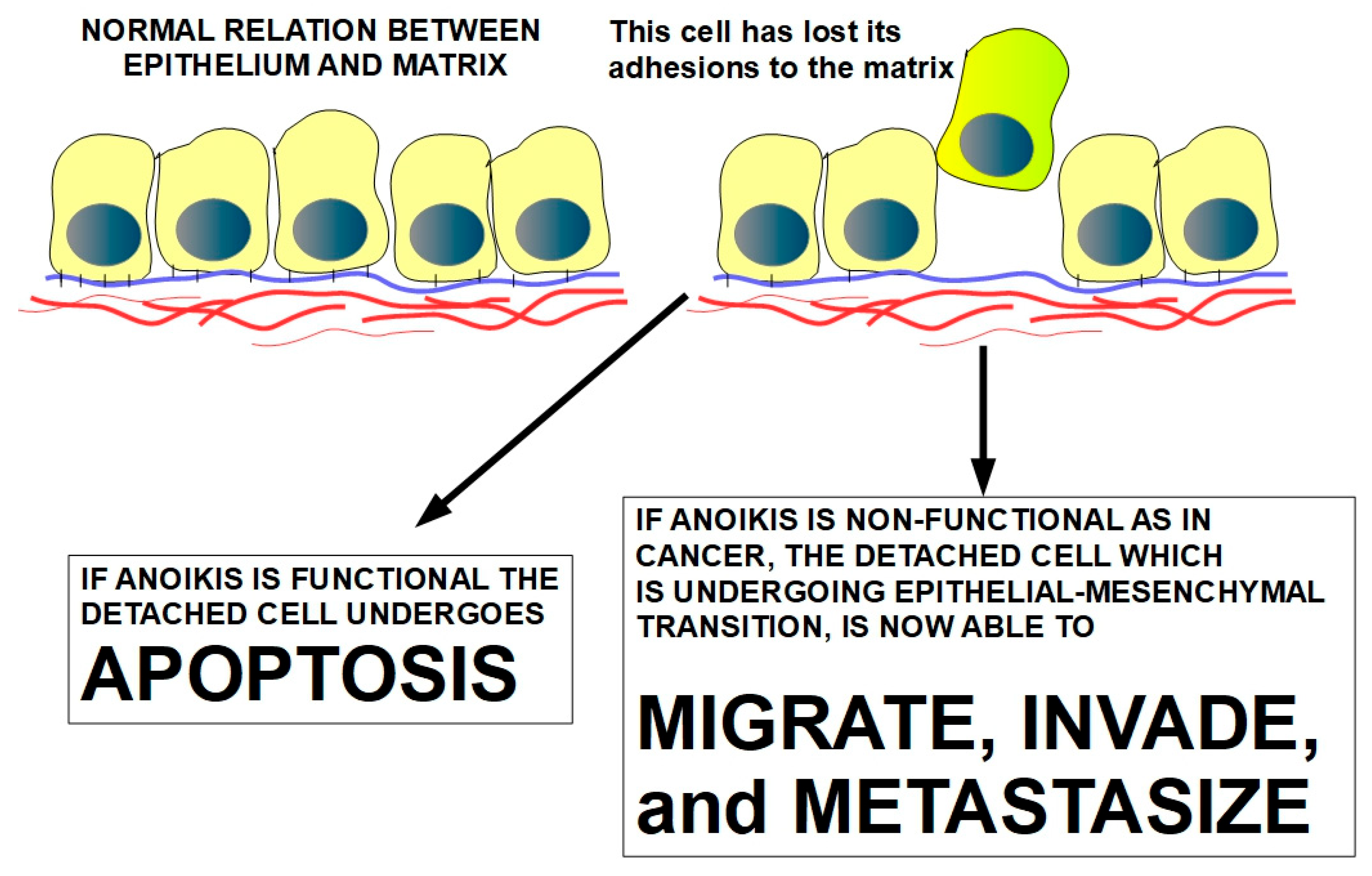

3. Anoikis Concept

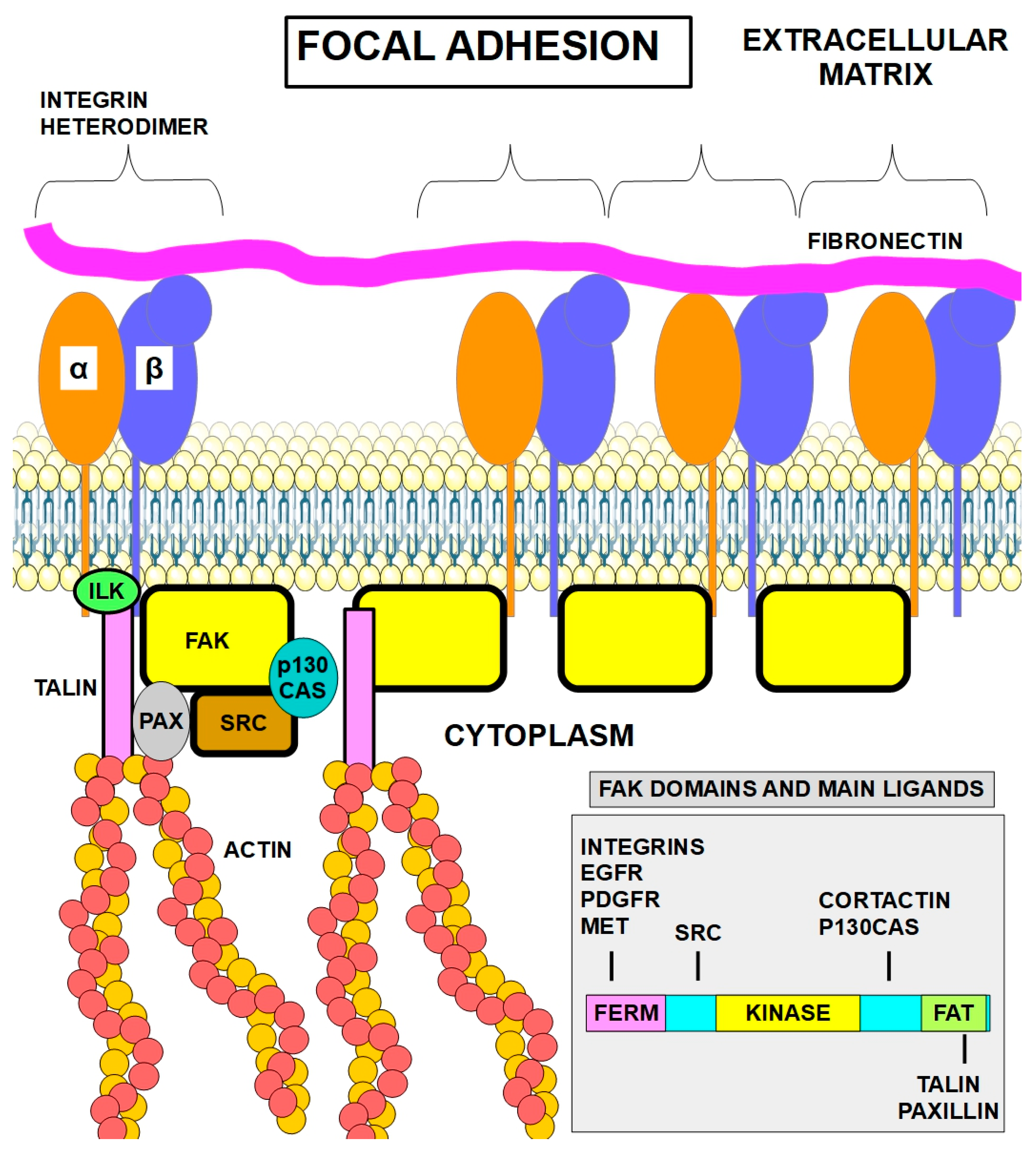

4. Focal Adhesions (FAs)

4.1. Focal Adhesions in Cancer

4.2. Key Molecules Involved in Focal Adhesions

5. The Main Players in Anoikis

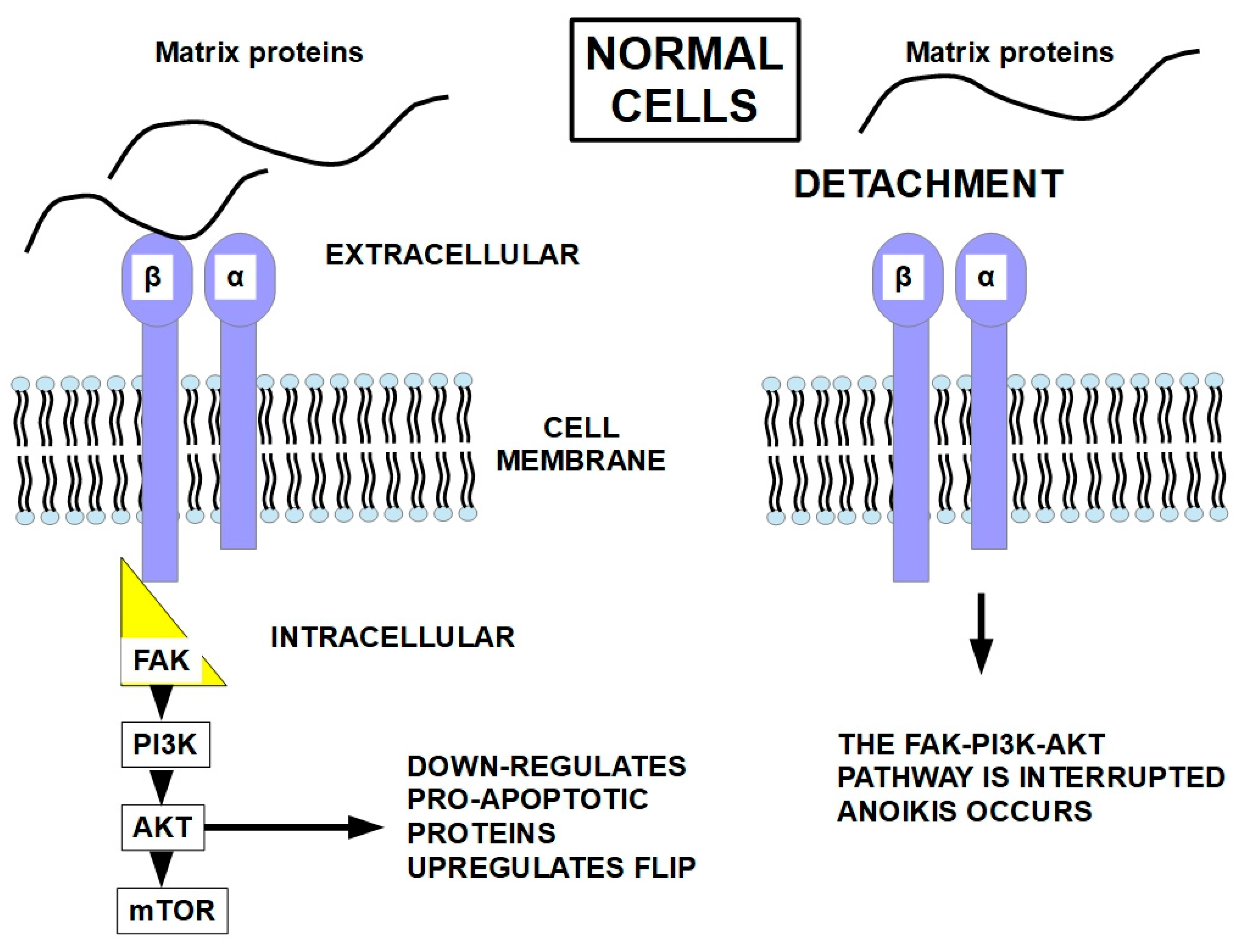

5.1. Integrins

- RGD-binding integrins: RGD receptors (Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) attachment site), constitute a major recognition system for cell adhesion [39,40]. Several integrins recognize and bind to the RGD motif, a key tripeptide sequence found in many extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins like fibronectin, vitronectin, and fibrinogen. These RGD-binding integrins play crucial roles in cell adhesion, migration, and signaling. Importantly, RGD-binding integrins like αvβ3 and αvβ5 are over-expressed in tumors and promote angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis [41];

-

leukocyte-specific receptors are a specialized subset of integrins that mediate immune cell adhesion, migration, and signaling. They are essential for immune surveillance, inflammation, and host defense [44]. These integrins are primarily expressed on white blood cells and are often referred to as β2 integrins or CD18 family;∙ collagen receptors that regulate proliferation, migration and adhesion [45].

5.1.1 Integrins as Sensors

Biochemical Sensing

Biomechanical Sensing [51]

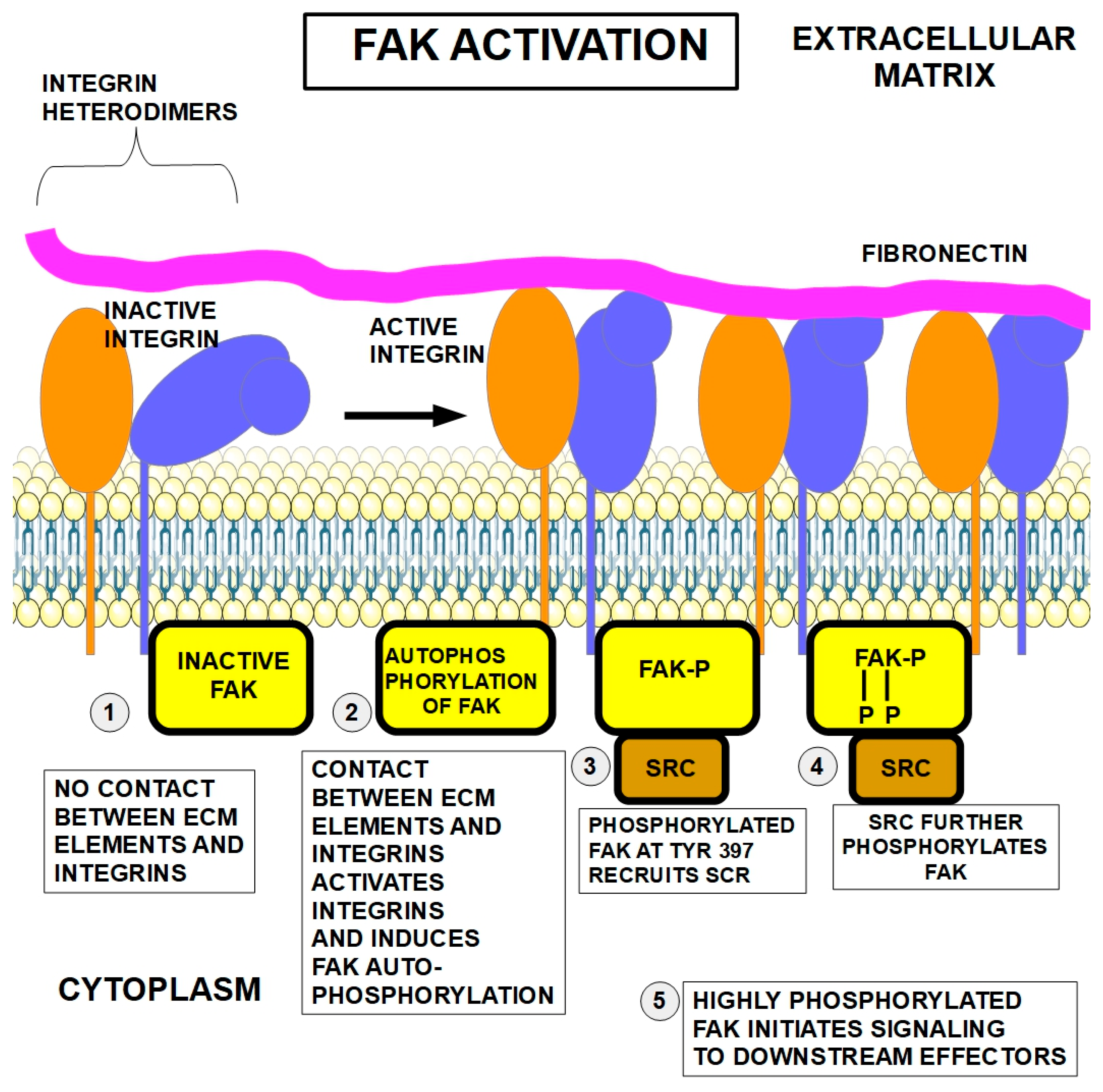

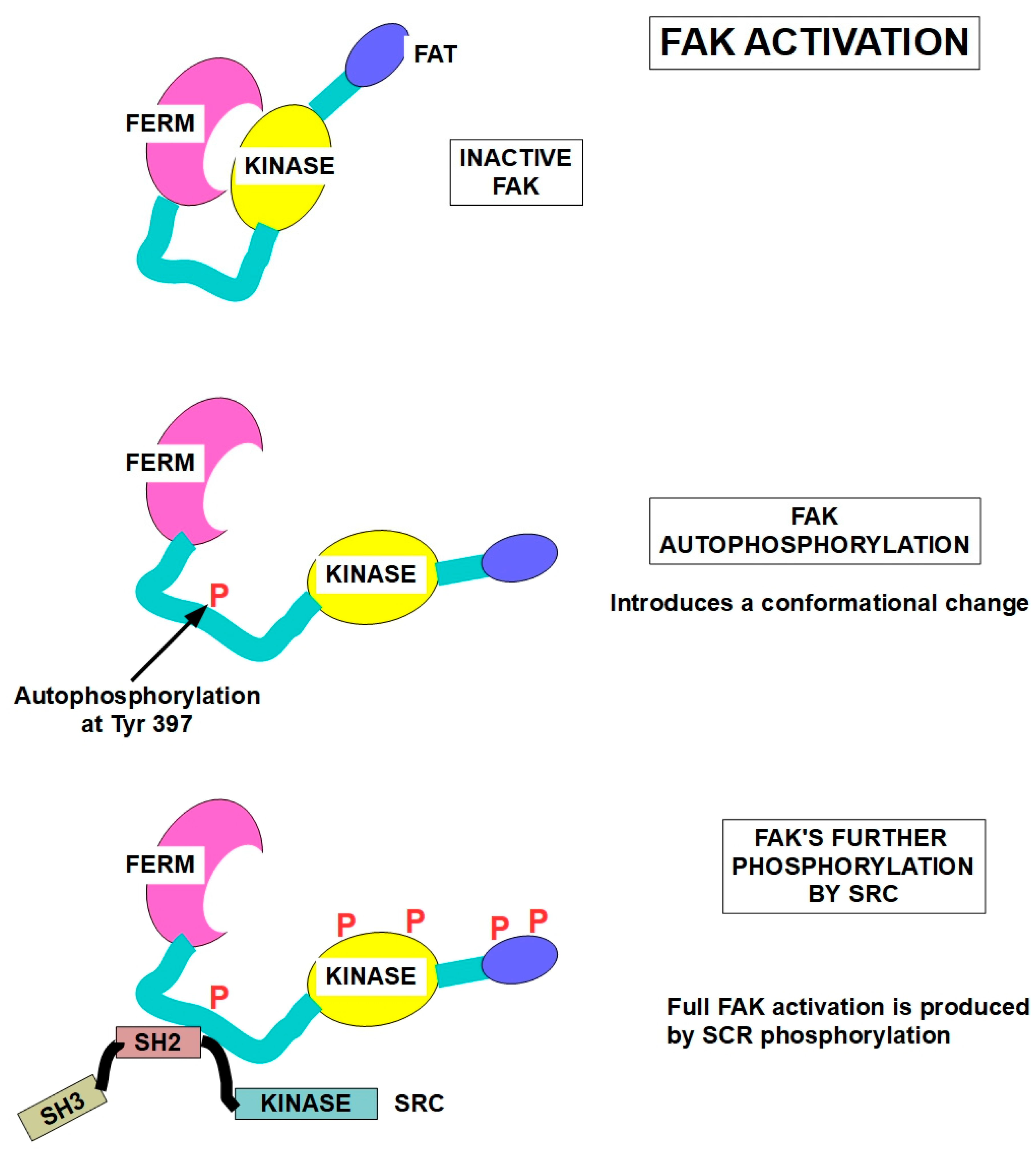

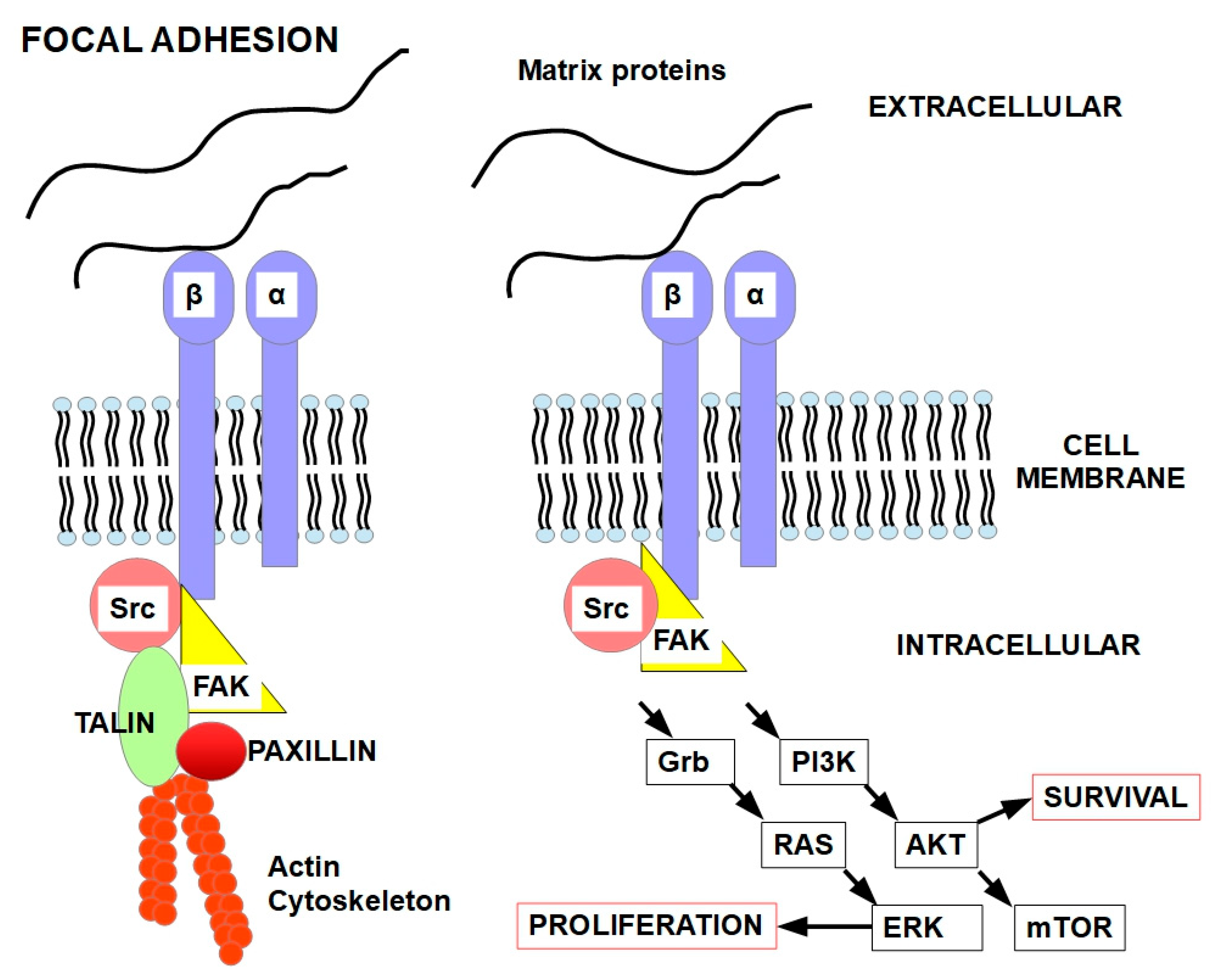

5.2. FAK

5.3. Integrin Linked Kinase (ILK)

5.4. SRC

5.5. p130Cas

5.6. Paxillin

6. Molecular Mechanisms of Anoikis

7. Specificity of the Surface to Which the Cell Is Attached

8. Specificity of Integrins

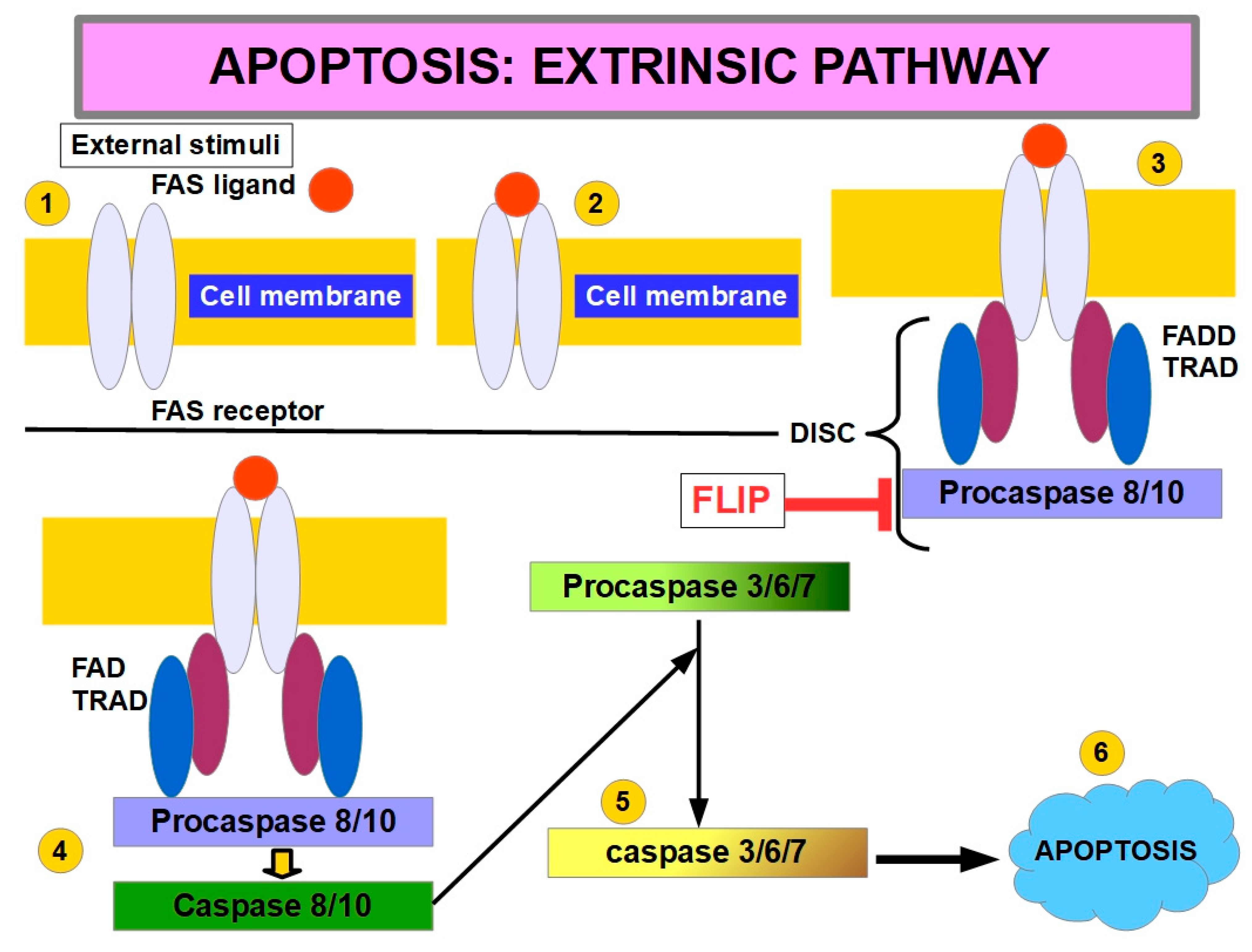

9. Relationship Between Cell Detachment and the Apoptosis Pathway

10. Resistance to Anoikis

11. Drivers of Anoikis Resistance

11.1. Major Drivers of Anoikis Resistance

11.1.1. Altered Integrins Expression

11.1.2. Activation of survival pathways such as:

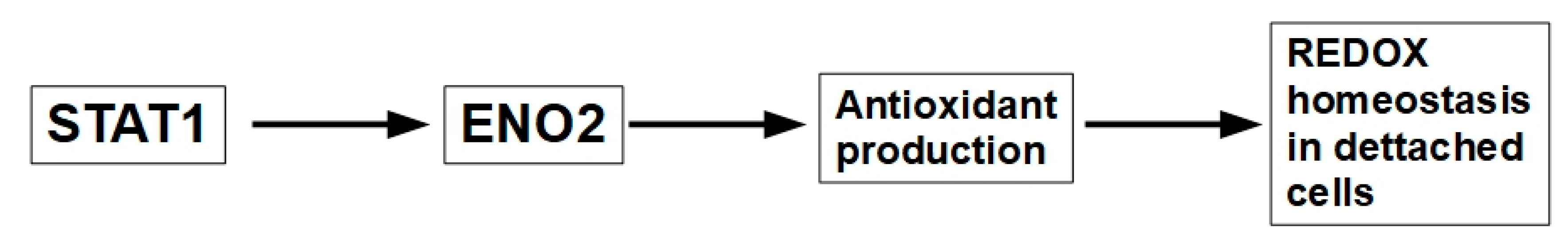

11.1.3. Metabolic Reprogramming

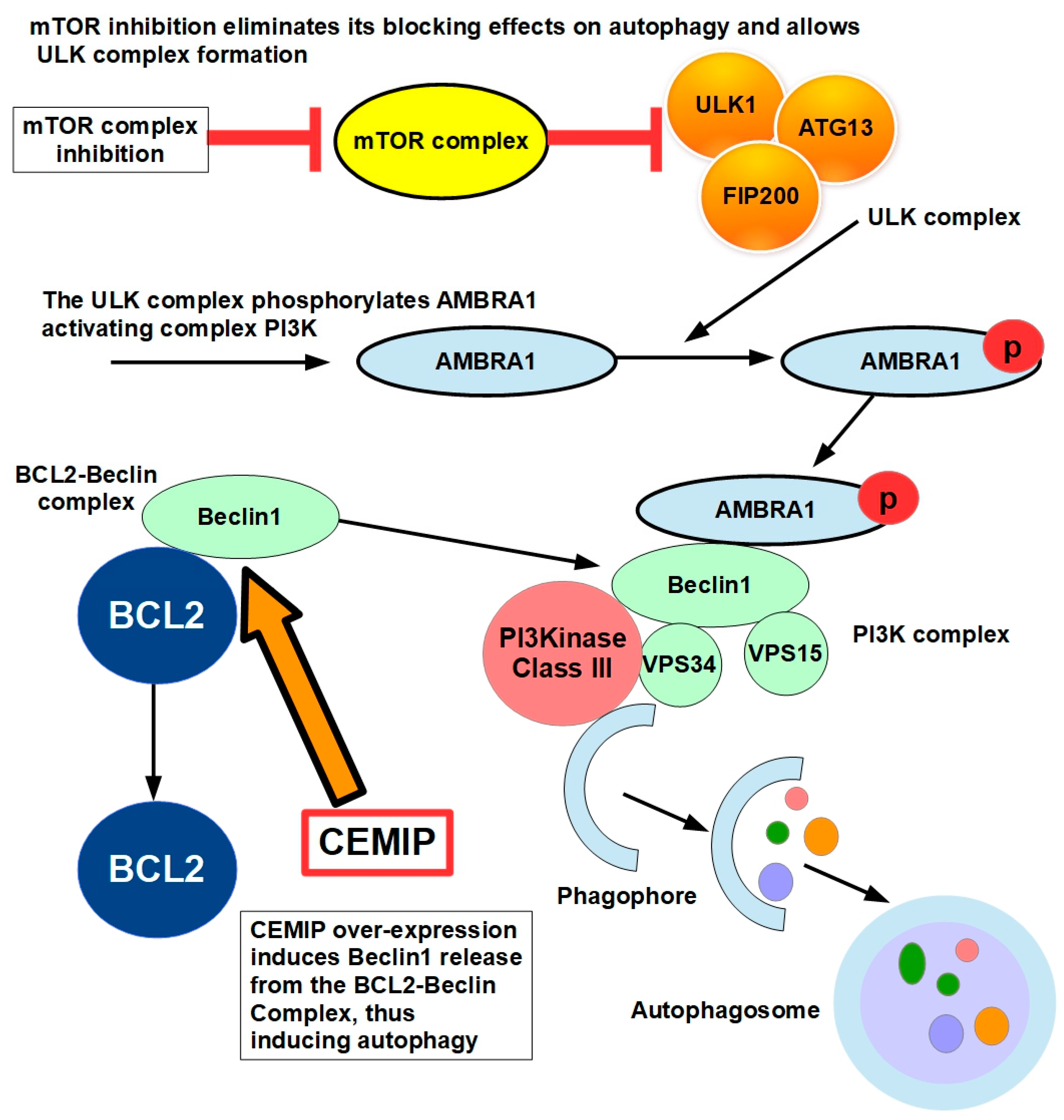

11.1.4. Autophagy

11.1.5. Cytoskeleton Reorganization

- actin remodeling that supports anchorage-independent growth and facilitates migration through tissues;

- microtubule stabilization that maintains intracellular transport and polarity in detached cells and promotes the formation of survival-promoting structures like giant unilamellar vacuoles which buffer mechanical stress.

- during epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) intermediate filaments such as vimentin are up-regulated contributing to structural integrity and resistance to mechanical stress;

- activation of survival pathways such as the Hippo pathway, particularly YAP/TAZ transcription factors, which promote cell survival and proliferation in detached conditions. Cell detachment activates the Hippo pathway kinases Lats1/2 and leads to YAP phosphorylation and inhibition. This detachment-induced YAP inactivation is essential for anoikis in non-malignant cells, whereas in cancer cells the deregulation of the Hippo pathway inhibits anoikis. Furthermore, knockdown of YAP and TAZ restores anoikis [184].

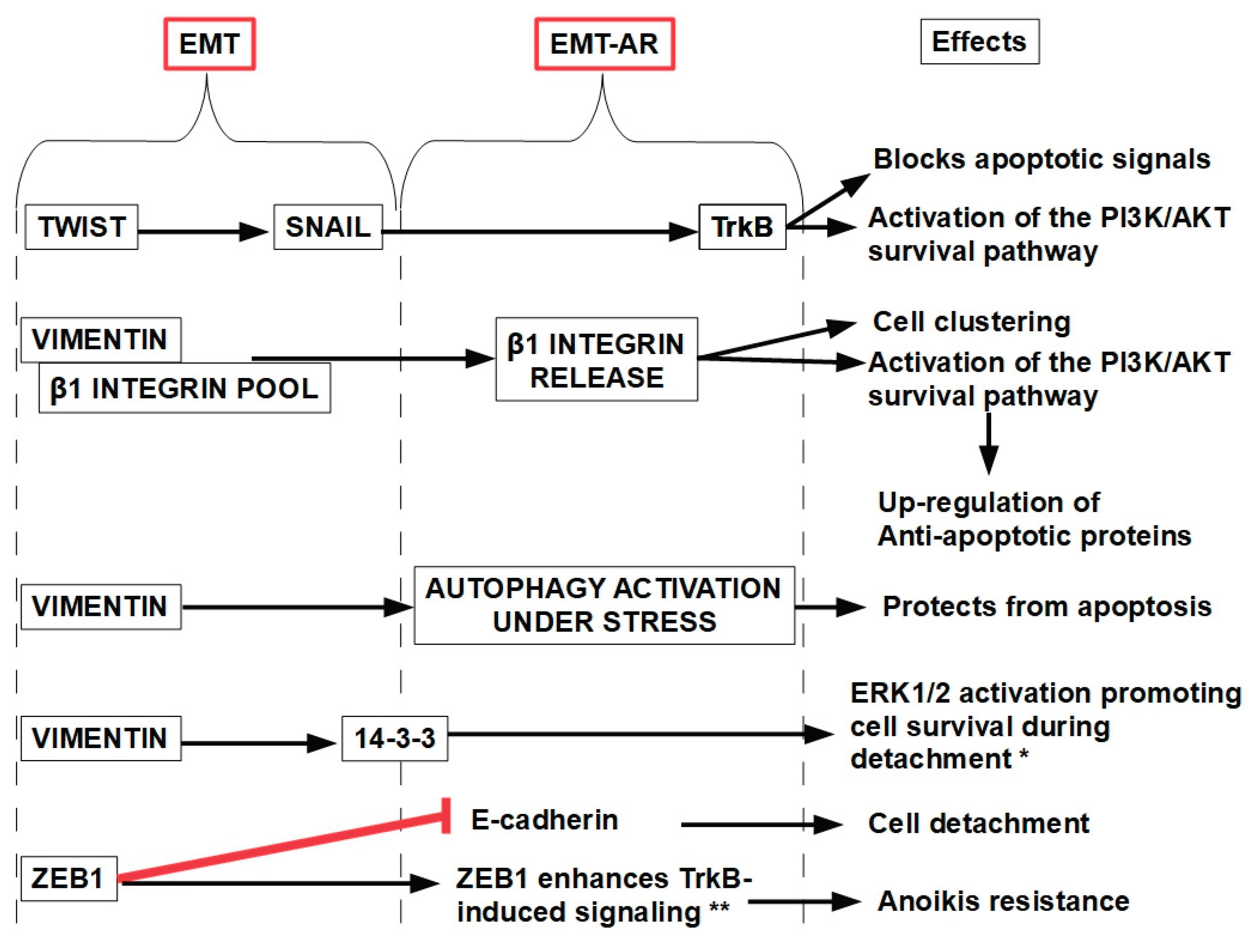

11.1.6. Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (EMT)

11.2. Other Drivers of Anoikis Resistance

11.2.1. Extracellular Acidity

11.2.2. V-ATPase Pump up-Regulation

11.2.3. Nitric Oxide (NO)

11.2.4. Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Growth Factor Receptors

11.2.5. EWS/FLI Oncogenic Protein

11.2.6. Oncoviruses and Anoikis Resistance

11.2.7. Mir141-Sp1 Axis

11.2.8. NHE1 (Sodium Hydrogen Exchanger 1)

11.2.9. FER Kinase (Feline Sarcoma Related Kinase)

11.2.10. Epigenetic Factors

11.2.11. Loss of E cadherin

12. Targeting Anoikis Resistance

12.1. V-ATPase Pump Inhibitors

12.2. Microtubule Destabilizing Agents

12.3. Anoikis Resistance in Pancreatic Cancer

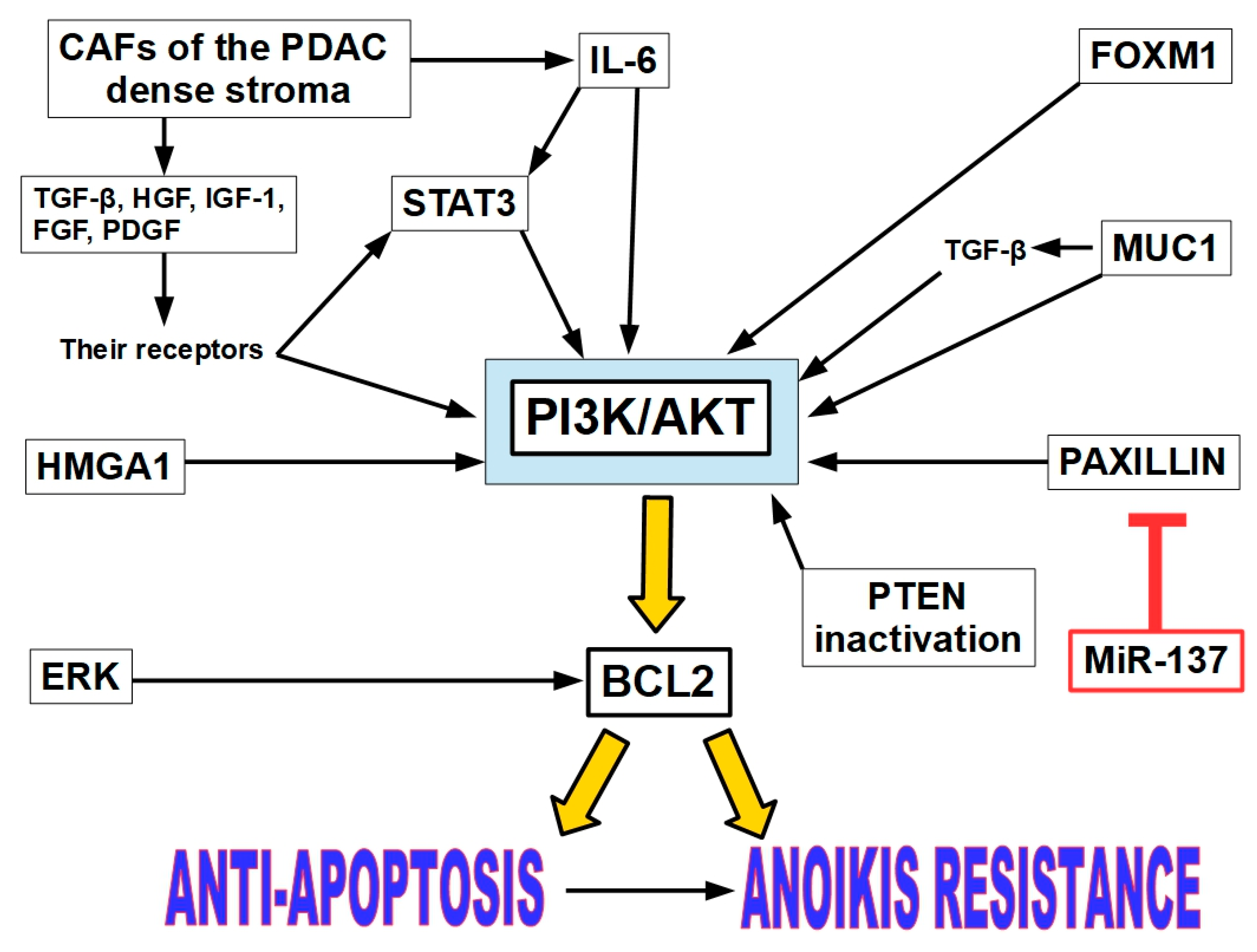

12.3.1. The PI3K/AKT Pathway Activation

Growth Factors and Cytokines Produced by CAFs

STAT3 Activation

MUC1 (mucin 1)

HMGA1

PAXILLIN

FOXM1 (Forkhead Box M1)Regulation

12.3.2. ERK/BCL-2 Pathway

12.3.3. STAT3 as Independent Driver of AR

12.3.4. Genetic Signature of Anoikis Resistance in PDAC

12.4. Targeting Signaling Pathways

12.4.1. Curcumol

12.4.2. Fucoxanthinol

12.4.3. Tunicamycin

12.4.4. Thapsigargin

12.4.5. Dasatinib

12.4.6. Celecoxib

12.4.7. Gefitinib

12.4.8. MEK Inhibitors

12.4.9. Disulfiram

12.4.10. Metformin

12.5. Integrin Inhibitors

12.5.1. Cilengitide

12.5.2. JSM6427

12.5.3. ILKAS

12.5.4. TDI4161

12.6. FAK Inhibitors

12.6.1. Doxycycline

12.6.2. Defactinib

12.7. Many Over-the-Counter Drugs and Nutraceuticals Have Been Shown to Counteract AR. Among Them Are:

12.7.1. Alpha-Mangostin

12.7.2. Aspirin

12.7.3. Berberine [315]

12.7.4. Apigenin

12.8. Targeting Integrin-EGFR Interaction

Doxazosin

12.9. Digoxin and Its Derivatives

12.10. Targeting STAT3

12.10.1. N4

12.10.2. WB436B

12.10.3. C188-9 (TTI-101)

12.10.4. OPB-111077

12.10.5. Stattic

12.10.6. YY002

12.10.7. Ibuprofen

12.10.8. Other Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

12.10.9. Targeting Sp1 Transcription Factor

13. Discussion

- (1)

- CDH1 (E-cadherin gene), EPCAM, and occludin down-regulation thus facilitating detachment.

- (2)

- Up-regulating VIM (vimentin gene, supporting cytoskeleton reorganization), CDH2 (N-cadherin that replaces E-cadherin), SNAI1 (Snail, that represses E-cadherin), TWIST1/2 (promote mesenchymal gene expression and stemness), and ZEB1(increases migratory abilities).

- Activates survival pathways: Sp1 up-regulates components of the PI3K/Akt, MAPK, and JAK/STAT pathways, which suppress apoptosis triggered by ECM detachment [373].

- Supports anchorage-independent growth: By maintaining survival signals, Sp1 enables cancer cells to thrive in suspension, a key step in metastasis.

- Sp1 can increase intracellular pH: Intracellular alkalinity is a handicap for the apoptotic process. Sp1 can alkalinize the cell by increasing proton export through the promotion of NHE1, NHE2, and NHE3 [376].

- Sp1represses epithelial markers: such as E-cadherin, weakening cell-cell adhesion.

- Activates mesenchymal genes: It promotes expression of vimentin, fibronectin, and N-cadherin, facilitating cytoskeletal remodeling and migration. Sp1 directly regulates the transcription of the vimentin gene by binding to its promoter [377].

- Cooperates with EMT transcription factors: Sp1 interacts with Snail, ZEB1, and Twist, amplifying EMT signaling and enhancing resistance to anoikis [378].

13.1. GENES

- MUC1: A big transmembrane glycoprotein, is usually found over-expressed in epithelial cancers [384] and particularly in pancreatic cancer. It disrupts cell adhesion and promotes survival signaling, helping cells evade anoikis. MUC1 glycosylation stimulates apoptosis and chemotherapy resistance to drugs such as bortezomib, trastuzumab and tamoxifen among others [385,386]. It also promotes multidrug resistance genes. Under stressful conditions, MUC1 is cleaved into two molecules, MUC1-N and MUC1-C which create inward pro-survival signals. The role of MUC1 in cancer goes well beyond anoikis resistance but will not be discussed here (for a review see Chen et al. [387], Lan et al. [388], and Qing et al. [389].

- KL (Klotho): The KL gene was identified in 1997 as an anti-aging gene and was initially believed to be a tumor suppressor gene/protein [390]. It is now evident that KL is a controversial gene/protein. Most articles describe KL as a tumor suppressor [391,392] but it also shows pro-tumoral effects that “increases cellular migration, anchorage-independent growth, and anoikis resistance in hepatoma cells” [393,394].

- MNX1 (motor neuron and pancreas homeobox 1): Is a pro-tumoral transcription factor linked to oncogenic transformation and anoikis resistance through metabolic and proliferative pathways. MNX1 was found to play an important role in developing anoikis resistance in glioblastoma. MNX1 was up-regulated in highly malignant glioma cell lines. MNX1 allowed malignant cells to bypass anoikis while reducing fibronectin adhesion [395]. MNX1- induced anoikis resistance was mediated by the activation of tyrosine kinase receptor B (TrkB) which is a downstream effector. It also promotes proliferation by up-regulating cyclin E [396], and CCDC34 (Coiled-coil domain-containing 34) [397]. In addition to glioblastoma, MNX1 was identified as an anoikis resistance gene in many tumors such as renal cell carcinoma [398], colon cancer [399], and acute myeloid leukemia [400].

- MMP3 and TIMP1 have been recognized as anoikis resistance genes in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma [401].

- ADCY10 (Adenylate Cyclase 10): Is involved in cAMP signaling, which can modulate survival pathways under stress. It has been identified as an AR gene signature in lung adenocarcinoma [404].

- TrkB (tropomyosin receptor kinase B) is a key suppressor of anoikis, enabling cancer cells to survive detachment and promoting metastasis. TrkB is a receptor tyrosine kinase that binds brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). It plays a critical role in neuronal survival and development but is hijacked by cancer cells to evade anoikis. TrkB activation blocks apoptotic signals triggered by loss of cell adhesion, allowing cells to survive detachment [405]. It also activates PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK signaling cascades promoting proliferation and survival [406], and it promotes epithelial mesenchymal transition increasing growth and metastatic potential [407]. TrkB activity is increased in tumors such as neuroblastoma, breast, lung, pancreatic, gastric, colorectal, ovarian and cervical cancers [408,409,410,411]. TrkB inhibitors have been developed:

- Experimental selective TrkB Inhibitors

13.2. PATHWAYS

- PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK signaling: These pathways are frequently activated in anoikis-resistant cells, promoting survival and proliferation.

- Metabolic reprogramming: Cancer cells adapt their metabolism (e.g., increased glycolysis) to survive without matrix attachment.

- EMT (Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition): EMT-related genes are often up-regulated, enhancing motility and resistance to cell death.

13.3. The Anoikis Resistance Environment

14. Conclusions

Declarations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sakamoto, S.; Kyprianou, N. Targeting anoikis resistance in prostate cancer metastasis. Molecular aspects of medicine 2010, 31, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Short, S.M.; Talbott, G.A.; Juliano, R.L. Integrin-mediated signaling events in human endothelial cells. Molecular biology of the cell 1998, 9, 1969–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giverso, C.; Jankowiak, G.; Preziosi, L.; Schmeiser, C. The influence of nucleus mechanics in modelling adhesion-independent cell migration in structured and confined environments. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology 2023, 85, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joussaume, A.; Karayan-Tapon, L.; Benzakour, O.; Dkhissi, F. A comparative study of anoikis resistance assays for tumor cells. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research 2020, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.; Fatima, K.; Malik, F. Understanding the cell survival mechanism of anoikis-resistant cancer cells during different steps of metastasis. Clinical & experimental metastasis 2022, 39, 715–726. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.C.; Watt, F.M. Regulation of development and differentiation by the extracellular matrix. Development 1993, 117, 1183–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.; Goldstein, D.; Crowe, P.; Yang, J.L. Uncovering a key to the process of metastasis in human cancers: a review of critical regulators of anoikis. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology 2013, 139, 1795–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoker, M.; O'Neill, C.; Berryman, S.; Waxman, V. Anchorage and growth regulation in normal and virus-transformed cells. International Journal of Cancer 1968, 3, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, S.M.; Francis, H. Disruption of epithelial cell-matrix interactions induces apoptosis. The Journal of cell biology 1994, 124, 619–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarugi, P.; Giannoni, E. Anoikis: a necessary death program for anchorage-dependent cells. Biochemical pharmacology 2008, 76, 1352–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strater, J.; Wedding, U.; Barth, T.F.; Koretz, K.; Elsing, C.; Moller, P. Rapid onset of apoptosis in vitro follows disruption of beta 1-integrin/matrix interactions in human colonic crypt cells. Gastroenterology 1996, 110, 1776–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.C.; Avivar-Valderas, A.; Sosa, M.S.; Girnius, N.; Farias, E.F.; Davis, R.J.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A. p38α signaling induces anoikis and lumen formation during mammary morphogenesis. Science signaling 2011, 4, ra34–ra34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strange, R.; Metcalfe, T.; Thackray, L.; Dang, M. Apoptosis in normal and neoplastic mammary gland development. Microscopy research and technique 2001, 52, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachon, P.H. Integrin signaling, cell survival, and anoikis: distinctions, differences, and differentiation. Journal of signal transduction 2011, 2011, 738137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, H.; Kobayashi, Y.; Sakai, E.; Shibata, M.; Kato, Y. Cell adhesion is a prerequisite for osteoclast survival. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2000, 270, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore; Anoikis, A. Cell Death Differ 2005, 12 Suppl 2, 1473–1477. [CrossRef]

- Mitra, S.K.; Hanson, D.A.; Schlaepfer, D.D. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2005, 6, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, Q.; Xuan, Z.; Zheng, Z.; Du, Y.; Sui, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, M.; et al. Mechanisms Involved in Focal Adhesion Signaling Regulating Tumor Anoikis Resistance. Cancer Science 2025, 116, 2640–2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, S.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Hao, X.; Hang, Q. Roles of integrins in gastrointestinal cancer metastasis. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences 2021, 8, 708779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.R.; Chay, C.H.; Pienta, K.J. The role of αvβ3 in prostate cancer progression. Neoplasia 2002, 4, 191–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sloan, E.K.; Pouliot, N.; Stanley, K.L.; Chia, J.; Moseley, J.M.; Hards, D.K.; Anderson, R.L. Tumor-specific expression of αvβ3 integrin promotes spontaneous metastasis of breast cancer to bone. Breast Cancer Research 2006, 8, R20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierke, C.T. The integrin alphav beta3 increases cellular stiffness and cytoskeletal remodeling dynamics to facilitate cancer cell invasion. New Journal of Physics 2013, 15, 015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Yan, D.; Liu, Y.; Huang, P.; Cui, H. The roles of integrin α5β1 in human cancer. OncoTargets and therapy 2020, 13329–13344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, R.K. Regulation of apoptosis by integrin receptors. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology 1997, 19, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Juliano, R.L. α5β1 integrin protects intestinal epithelial cells from apoptosis through a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and protein kinase B–dependent pathway. Molecular biology of the cell 2000, 11, 1973–1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiniotis, A.; Kyprianou, N. Significance of talin in cancer progression and metastasis. International review of cell and molecular biology 2011, 289, 117–147. [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood, D.A.; Yan, B.; de Pereda, J.M.; Alvarez, B.G.; Fujioka, Y.; Liddington, R.C.; Ginsberg, M.H. The phosphotyrosine binding-like domain of talin activates integrins. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 21749–21758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, M.; Legate, K.R.; Zent, R.; Fässler, R. The tail of integrins, talin, and kindlins. Science 2009, 324, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, M.D.; Hildebrand, J.D.; Shannon, J.D.; Fox, J.W.; Vines, R.R.; Parsons, J.T. Autophosphorylation of the Focal Adhesion Kinase, ppl25FAK, Directs SH2-Dependent Binding of pp60 src. Molecular and cellular biology 1994, 14, 1680–1688. [Google Scholar]

- Tapial Martínez, P.; López Navajas, P.; Lietha, D. FAK structure and regulation by membrane interactions and force in focal adhesions. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, J.D.; Ruest, P.J.; Fry, D.W.; Hanks, S.K. Induced focal adhesion kinase (FAK) expression in FAK-null cells enhances cell spreading and migration requiring both auto-and activation loop phosphorylation sites and inhibits adhesion-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of Pyk2. Molecular and cellular biology 1999, 19, 4806–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avizienyte, E.; Frame, M.C. Src and FAK signalling controls adhesion fate and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Current opinion in cell biology 2005, 17, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K. Signal transduction mechanisms of focal adhesions: Src and FAK-mediated cell response. Frontiers in Bioscience-Landmark 2024, 29, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.C.; Cary, L.A.; Jamieson, J.S.; Cooper, J.A.; Turner, C.E. Src and FAK kinases cooperate to phosphorylate paxillin kinase linker, stimulate its focal adhesion localization, and regulate cell spreading and protrusiveness. Molecular biology of the cell 2005, 16, 4316–4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancotti, F.G.; Ruoslahti, E. Integrin signaling. science 1999, 285, 1028–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, B.; Delaney, M.K.; Du, X. Inside-out, outside-in, and inside–outside-in: G protein signaling in integrin-mediated cell adhesion, spreading, and retraction. Current opinion in cell biology 2012, 24, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sampson, C.; Liu, C.; Piao, H.L.; Liu, H.X. Integrin signaling in cancer: bidirectional mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, A.E.; Kozlova, N.I.; Morozevich, G.E. Integrins: structure and signaling. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2003, 68, 1284–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoslahti, E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annual review of cell and. [CrossRef]

- developmental biology 1996, 12, 697–715.

- Akiyama, S.K. Integrins in cell adhesion and signaling. Human cell 1996, 9, 181–186. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, B.S.; Kessler, H.; Kossatz, S.; Reuning, U. RGD-binding integrins revisited: how recently discovered functions and novel synthetic ligands (re-) shape an ever-evolving field. Cancers 2021, 13, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wewer, U.M.; Taraboletti, G.; Sobel, M.E.; Albrechtsen, R.; Liotta, L.A. Role of laminin receptor in tumor cell migration. Cancer research 1987, 47, 5691–5698. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Lo, W.-C.; Majumder, P.; Roy, D.; Ghorai, M.; Shaikh, N.K.; Kant, N.; Shekhawat, M.S.; Gadekar, V.S.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Multiple roles for basement membrane proteins in cancer progression and EMT. European journal of cell biology 2022, 101, 151220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogg, N.; Patzak, I.; Willenbrock, F. The insider's guide to leukocyte integrin signalling and function. Nature Reviews Immunology 2011, 11, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitinger, B. Transmembrane collagen receptors. Annual review of cell and developmental biology 2011, 27, 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanko, J.; Mai, A.; Jacquemet, G.; Schauer, K.; Kaukonen, R.; Saari, M.; Goud, B.; Ivaska, J. Integrin endosomal signalling suppresses anoikis. Nature cell biology 2015, 17, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maubant, S.; Saint-Dizier, D.; Boutillon, M.; Perron-Sierra, F.; Casara, P.J.; Hickman, J.A.; Tucker, G.C.; Van Obberghen-Schilling, E. Blockade of αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrins by RGD mimetics induces anoikis and not integrin-mediated death in human endothelial cells. Blood 2006, 108, 3035–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hynes, R.O. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. cell 2002, 110, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welf, E.S.; Naik, U.P.; Ogunnaike, B.A. A spatial model for integrin clustering as a result of feedback between integrin activation and integrin binding. Biophysical journal 2012, 103, 1379–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changede, R.; Sheetz, M. Integrin and cadherin clusters: A robust way to organize adhesions for cell mechanics. BioEssays 2017, 39, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kechagia, J.Z.; Ivaska, J.; Roca-Cusachs, P. Integrins as biomechanical sensors of the microenvironment. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2019, 20, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, M.; Farhood, B.; Mortezaee, K. Extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness and degradation as cancer drivers. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2019, 120, 2782–2790. [Google Scholar]

- Wullkopf, L.; West, A.K. V.; Leijnse, N.; Cox, T.R.; Madsen, C.D.; Oddershede, L.B.; Erler, J.T. Cancer cells’ ability to mechanically adjust to extracellular matrix stiffness correlates with their invasive potential. Molecular biology of the cell 2018, 29, 2378–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkretsi, V.; Stylianopoulos, T. Cell adhesion and matrix stiffness: coordinating cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Frontiers in oncology 2018, 8, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K. Integrin and Its Associated Proteins as a Mediator for Mechano-Signal Transduction. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanks, S.K.; Ryzhova, L.; Shin, N.Y.; Brábek, J. Focal adhesion kinase signaling activities and their implications in the control of cell survival and motility. Front Biosci 2003, 8, d982–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierke, C.T.; Fischer, T.; Puder, S.; Kunschmann, T.; Soetje, B.; Ziegler, W.H. Focal adhesion kinase activity is required for actomyosin contractility-based invasion of cells into dense 3D matrices. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 42780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuang, H.H.; Zhen, Y.Y.; Tsai, Y.C.; Chuang, C.H.; Hsiao, M.; Huang, M.S.; Yang, C.J. FAK in cancer: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomar, A.; Schlaepfer, D.D. Focal adhesion kinase: switching between GAPs and GEFs in the regulation of cell motility. Current opinion in cell biology 2009, 21, 676–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genna, A.; Lapetina, S.; Lukic, N.; Twafra, S.; Meirson, T.; Sharma, V.P.; Condeelis, J.S.; Gil-Henn, H. Pyk2 and FAK differentially regulate invadopodia formation and function in breast cancer cells. Journal of Cell Biology 2018, 217, 375–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousson, A.; Legrand, M.; Steffan, T.; Vauchelles, R.; Carl, P.; Gies, J.-P.; Lehmann, M.; Zuber, G.; De Mey, J.; Dujardin, D.; et al. Inhibiting FAK–paxillin interaction reduces migration and invadopodia-mediated matrix degradation in metastatic melanoma cells. Cancers 2021, 13, 1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuefeng, X.; Hou, M.-X.; Yang, Z.-W.; Agudamu, A.; Wang, F.; Su, X.-L.; Li, X.; Shi, L.; Terigele, T.; Bao, L.-L.; et al. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition and metastasis of colon cancer cells induced by the FAK pathway in cancer-associated fibroblasts. Journal of International Medical Research 2020, 48, 0300060520931242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilghman, R.W.; Parsons, J.T. Focal adhesion kinase as a regulator of cell tension in the progression of cancer. In Seminars in cancer biology; Academic Press, February 2008; Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Sawai, H.; Okada, Y.; Funahashi, H.; Matsuo, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Takeyama, H.; Manabe, T. Activation of focal adhesion kinase enhances the adhesion and invasion of pancreatic cancer cells via extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1/2 signaling pathway activation. Molecular cancer 2005, 4, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duxbury, M.S.; Ito, H.; Zinner, M.J.; Ashley, S.W.; Whang, E.E. Focal adhesion kinase gene silencing promotes anoikis and suppresses metastasis of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Surgery 2004, 135, 555–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carelli, S.; Zadra, G.; Vaira, V.; Falleni, M.; Bottiglieri, L.; Nosotti, M.; Di Giulio, A.M.; Gorio, A.; Bosari, S. Up-regulation of focal adhesion kinase in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung cancer 2006, 53, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocak, S.; Chen, H.; Callison, C.; Gonzalez, A.L.; Massion, P.P. Expression of focal adhesion kinase in small-cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 2012, 118, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sood, A.K.; Coffin, J.E.; Schneider, G.B.; Fletcher, M.S.; DeYoung, B.R.; Gruman, L.M.; Gershenson, D.M.; Schaller, M.D.; Hendrix, M.J. Biological significance of focal adhesion kinase in ovarian cancer: role in migration and invasion. The American journal of pathology 2004, 165, 1087–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, B.L.; Yoon, J.; Kim, J.; Kim, M.A.; Yang, H.K.; Kim, W.H. Focal adhesion kinase (FAK) gene amplification and its clinical implications in gastric cancer. Human pathology 2010, 41, 1664–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lark, A.L.; Livasy, C.A.; Calvo, B.; Caskey, L.; Moore, D.T.; Yang, X.; Cance, W.G. Overexpression of focal adhesion kinase in primary colorectal carcinomas and colorectal liver metastases: immunohistochemistry and real-time PCR analyses. Clinical Cancer Research 2003, 9, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Role of focal adhesion kinase in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and its therapeutic prospect. OncoTargets and therapy 2020, 10207–10220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigiracciolo, D.C.; Cirillo, F.; Talia, M.; Muglia, L.; Gutkind, J.S.; Maggiolini, M.; Lappano, R. Focal adhesion kinase fine tunes multifaced signals toward breast cancer progression. Cancers 2021, 13, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yom, C.K.; Noh, D.Y.; Kim, W.H.; Kim, H.S. Clinical significance of high focal adhesion kinase gene copy number and overexpression in invasive breast cancer. Breast cancer research and treatment 2011, 128, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šelemetjev, S.; Bartolome, A.; Išić Denčić, T.; Đorić, I.; Paunović, I.; Tatić, S.; Cvejić, D. Overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor and its downstream effector, focal adhesion kinase, correlates with papillary thyroid carcinoma progression. International journal of experimental pathology 2018, 99, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignjatović, V.B.; Janković Miljuš, J.R.; Rončević, J.V.; Tatić, S.B.; Išić Denčić, T.M.; Đorić, I.Đ.; Šelemetjev, S.A. Focal adhesion kinase splicing and protein activation in papillary thyroid carcinoma progression. Histochemistry and Cell Biology 2022, 157, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.T.; Fleming, J.B.; Lopez-Guzman, C.; Nwariaku, F. Focal adhesions and associated proteins in medullary thyroid carcinoma cells. Journal of Surgical Research 2003, 111, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Koshikawa, K.; Nomoto, S.; Okochi, O.; Kaneko, T.; Inoue, S.; Yatabe, Y.; Takeda, S.; Nakao, A. Focal adhesion kinase is overexpressed in hepatocellular carcinoma and can be served as an independent prognostic factor. Journal of hepatology 2004, 41, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.P.; Willey, C.D.; Anderson, J.C.; Welaya, K.; Chen, D.; Mehta, A.; Ghatalia, P.; Madan, A.; Naik, G.; Sudarshan, S.; et al. Kinomic profiling identifies focal adhesion kinase 1 as a therapeutic target in advanced clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 29220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, L.; Sun, X.; You, Y.; Liu, N.; Fu, Z. Expression of focal adhesion kinase and phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase in human gliomas is associated with unfavorable overall survival. Translational Research 2010, 156, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.-J.; LaFortune, T.; Honda, T.; Ohmori, O.; Hatakeyama, S.; Meyer, T.; Jackson, D.; de Groot, J.; Yung, W.A. Inhibition of both focal adhesion kinase and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor kinase suppresses glioma proliferation in vitro and in vivo. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2007, 6, 1357–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahana, O.; Micksche, M.; Witz, I.P.; Yron, I. The focal adhesion kinase (P125FAK) is constitutively active in human malignant melanoma. Oncogene 2002, 21, 3969–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kircher, D.A.; Trombetti, K.A.; Silvis, M.R.; Parkman, G.L.; Fischer, G.M.; Angel, S.N.; Stehn, C.M.; Strain, S.C.; Grossmann, A.H.; Duffy, K.L.; et al. AKT1E17K activates focal adhesion kinase and promotes melanoma brain metastasis. Molecular Cancer Research 2019, 17, 1787–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.H.; Wang, S.Q.; Shang, H.L.; Lv, H.F.; Chen, B.B.; Gao, S.G.; Chen, X.B. Roles and inhibitors of FAK in cancer: current advances and future directions. Front Pharmacol 2024, 15, 1274209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, C.D.; Anyiwe, K.; Schimmer, A.D. Anoikis resistance and tumor metastasis. Cancer letters 2008, 272, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paoli, P.; Giannoni, E.; Chiarugi, P. Anoikis molecular pathways and its role in cancer progression. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research 2013, 1833, 3481–3498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofaria, N.M.; Srivastava, S.K. STAT3 induces anoikis resistance, promotes cell invasion and metastatic potential in pancreatic cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36, 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadamillas, M.C.; Cerezo, A.; Del Pozo, M.A. Overcoming anoikis–pathways to anchorage-independent growth in cancer. Journal of cell science 2011, 124, 3189–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brakebusch, C.; Bouvard, D.; Stanchi, F.; Sakai, T.; Fässler, R. Integrins in invasive growth. The Journal of clinical investigation 2002, 109, 999–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagaprashantha, L.D.; Vatsyayan, R.; Lelsani, P.C.R.; Awasthi, S.; Singhal, S.S. The sensors and regulators of cell–matrix surveillance in anoikis resistance of tumors. International Journal of Cancer 2011, 128, 743–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedhar, S.; Williams, B.; Hannigan, G. Integrin-linked kinase (ILK): a regulator of integrin and growth-factor signalling. Trends in cell biology 1999, 9, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska, A.; Mazur, A.J. Integrin-linked kinase (ILK): the known vs. the unknown and perspectives. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2022, 79, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukuda, K.; Gupta, S.; Chen, K.; Wu, C.; Qin, J. The pseudoactive site of ILK is essential for its binding to α-Parvin and localization to focal adhesions. Molecular cell 2009, 36, 819–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attwell, S.; Roskelley, C.; Dedhar, S. The integrin-linked kinase (ILK) suppresses anoikis. Oncogene 2000, 19, 3811–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, D.S.; Tripodi, M.C.; Blanchette, J.O.; Langer, S.J.; Leinwand, L.A.; Anseth, K.S. Integrin-linked kinase production prevents anoikis in human mesenchymal stem cells. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A: An Official Journal of The Society for Biomaterials, The Japanese Society for Biomaterials, and The Australian Society for Biomaterials and the Korean Society for Biomaterials 2007, 81, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stehelin, D.; Varmus, H.E.; Bishop, J.M.; Vogt, P.K. DNA related to the transforming gene (s) of avian sarcoma viruses is present in normal avian DNA. Nature 1976, 260, 170–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downloaded from https://pdb101.rcsb.org/motm/43 Accessed February 2024.

- Abram, C.L.; Courtneidge, S.A. Src family tyrosine kinases and growth factor signaling. Experimental cell research 2000, 254, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roskoski, R., Jr. Src protein-tyrosine kinase structure, mechanism, and small molecule inhibitors. Pharmacological research 2015, 94, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westhoff, M.A.; Serrels, B.; Fincham, V.J.; Frame, M.C.; Carragher, N.O. SRC-mediated phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase couples actin and adhesion dynamics to survival signaling. Molecular and cellular biology 2004, 24, 8113–8133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.; Pellet-Many, C.; Zachary, I.C.; Evans, I.M.; Frankel, P. p130Cas: a key signalling node in health and disease. Cellular signalling 2013, 25, 766–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harte, M.T.; Hildebrand, J.D.; Burnham, M.R.; Bouton, A.H.; Parsons, J.T. p130Cas, a substrate associated with v-Src and v-Crk, localizes to focal adhesions and binds to focal adhesion kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1996, 271, 13649–13655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defilippi, P.; Di Stefano, P.; Cabodi, S. p130Cas: a versatile scaffold in signaling networks. Trends in cell biology 2006, 16, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kook, S.; Shim, S.R.; Choi, S.J.; Ahnn, J.; Kim, J.I.; Eom, S.H.; Jung, Y.K.; Paik, S.G.; Song, W.K. Caspase-mediated cleavage of p130cas in etoposide-induced apoptotic Rat-1 cells. Molecular biology of the cell 2000, 11, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojaniemi, M.; Vuori, K. Epidermal growth factor modulates tyrosine phosphorylation of p130Cas: involvement of phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase and actin cytoskeleton. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1997, 272, 25993–25998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Colomé, A.M.; Lee-Rivera, I.; Benavides-Hidalgo, R.; López, E. Paxillin: a crossroad in pathological cell migration. Journal of hematology & oncology 2017, 10, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Panera, N.; Crudele, A.; Romito, I.; Gnani, D.; Alisi, A. Focal adhesion kinase: insight into molecular roles and functions in hepatocellular carcinoma. International journal of molecular sciences 2017, 18, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indovina, P.; Forte, I.M.; Pentimalli, F.; Giordano, A. Targeting SRC family kinases in mesothelioma: Time to upgrade. Cancers 2020, 12, 1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giancotti, F.G. Complexity and specificity of integrin signalling. Nature cell biology 2000, 2, E13–E14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddei, M.L.; Giannoni, E.; Fiaschi, T.; Chiarugi, P. Anoikis: an emerging hallmark in health and diseases. The Journal of pathology 2012, 226, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupack, D.G.; Cheresh, D.A. Get a ligand, get a life: integrins, signaling and cell survival. Journal of cell science 2002, 115, 3729–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, V.; Demers, M.; Thibodeau, S.; Laquerre, V.; Fujita, N.; Tsuruo, T.; Beaulieu, J.; Gauthier, R.; Vézina, A.; Villeneuve, L.; et al. Fak/Src signaling in human intestinal epithelial cell survival and anoikis: differentiation state-specific uncoupling with the PI3-K/Akt-1 and MEK/Erk pathways. Journal of cellular physiology 2007, 212, 717–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Layseca, P.; Streuli, C.H. Signalling pathways linking integrins with cell cycle progression. Matrix Biology 2014, 34, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.H.; Li, J.; Jaumouillé, V.; Hao, Y.; Coppola, J.; Yan, J.; Waterman, C.M.; Springer, T.A.; Ha, T. Single-molecule characterization of subtype-specific β1 integrin mechanics. Nature communications 2022, 13, 7471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khwaja, A.; Lehmann, K.; Marte, B.M.; Downward, J. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase induces scattering and tubulogenesis in epithelial cells through a novel pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1998, 273, 18793–18801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stracke, M.L.; Soroush, M.; Liotta, L.A.; Schiffmann, E. Cytoskeletal agents inhibit motility and adherence of human tumor cells. Kidney international 1993, 43, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death & Differentiation 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazi, A. Targeting the extrinsic apoptotic pathway in cancer: lessons learned and future directions. The Journal of clinical investigation 2015, 125, 487–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derouet, M.; Wu, X.; May, L.; Yoo, B.H.; Sasazuki, T.; Shirasawa, S.; Rake, J.; Rosen, K.V. Acquisition of anoikis resistance promotes the emergence of oncogenic K-ras mutations in colorectal cancer cells and stimulates their tumorigenicity in vivo. Neoplasia 2007, 9, 536–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Livas, T.; Kyprianou, N. Anoikis and EMT: lethal" liaisons" during cancer progression. Critical Reviews™ in Oncogenesis 2016, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.N.; Koo, K.H.; Sung, J.Y.; Yun, U.J.; Kim, H. Anoikis resistance: an essential prerequisite for tumor metastasis. International journal of cell biology 2012, 2012, 306879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luey, B.C.; May, F.E. Insulin-like growth factors are essential to prevent anoikis in oestrogen-responsive breast cancer cells: importance of the type I IGF receptor and PI3-kinase/Akt pathway. Molecular cancer 2016, 15, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.B.; Sugimoto, K.; Harris, R.C. Juxtacrine activation of epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor by membrane-anchored heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor protects epithelial cells from anoikis while maintaining an epithelial phenotype. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2007, 282, 32890–32901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Sung, J.Y.; Park, E.-K.; Kho, S.; Koo, K.H.; Park, S.-Y.; Goh, S.-H.; Jeon, Y.K.; Oh, S.; Park, B.-K.; et al. Regulation of anoikis resistance by NADPH oxidase 4 and epidermal growth factor receptor. British journal of cancer 2017, 116, 370–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinis, B.; Reiss, K.; Baserga, R. Insulin-like growth factor-I-mediated survival from Anoikis: Role of cell aggregation and focal adhesion kinase. Journal of cellular physiology 1998, 176, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeshakin, F.O.; Adeshakin, A.O.; Afolabi, L.O.; Yan, D.; Zhang, G.; Wan, X. Mechanisms for modulating anoikis resistance in cancer and the relevance of metabolic reprogramming. Frontiers in Oncology 2021, 11, 626577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okayama, H. Cell cycle control by anchorage signaling. Cellular Signalling 2012, 24, 1599–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ou, Y.; Zou, L.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Q.; Qin, Y.; Du, X.; Li, W.; Yuan, Z.; et al. Anoikis resistance––protagonists of breast cancer cells survive and metastasize after ECM detachment. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith Jr, J.E.; Fazeli, B.; Schwartz, M.A. The extracellular matrix as a cell survival factor. Molecular biology of the cell 1993, 4, 953–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, V.; Frisch, S.M.; Juliano, R.L. Expression of the integrin α5 subunit in HT29 colon carcinoma cells suppresses apoptosis triggered by serum deprivation. Experimental cell research 1996, 224, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, P.C.; Montgomery, A.M.; Rosenfeld, M.; Reisfeld, R.A.; Hu, T.; Klier, G.; Cheresh, D.A. Integrin αvβ3 antagonists promote tumor regression by inducing apoptosis of angiogenic blood vessels. Cell 1994, 79, 1157–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Y.; Yi, J.; Zhang, W.; Chen, D.; Ao, J.; Xiao, Z.-X.; Yi, Y. Integrin β1-mediated cell–cell adhesion augments metformin-induced anoikis. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhl, M.; Sahin, E.; Johannsen, M.; Somasundaram, R.; Manski, D.; Riecken, E.O.; Schuppan, D. Soluble collagen VI drives serum-starved fibroblasts through S phase and prevents apoptosis via down-regulation of Bax. Journal of Biological Chemistry 1999, 274, 34361–34368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoudjit, F.; Vuori, K. Matrix attachment regulates Fas-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells: a role for c-flip and implications for anoikis. The Journal of cell biology 2001, 152, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupack, D.G.; Puente, X.S.; Boutsaboualoy, S.; Storgard, C.M.; Cheresh, D.A. Apoptosis of adherent cells by recruitment of caspase-8 to unligated integrins. Journal of Cell Biology 2001, 155, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laguinge, L.M.; Samara, R.N.; Wang, W.; El-Deiry, W.S.; Corner, G.; Augenlicht, L.; Jessup, J.M. DR5 receptor mediates anoikis in human colorectal carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Research 2008, 68, 909–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, H.L.; Li, J.; Kogan, S.; Languino, L.R. Integrins in prostate cancer progression. Endocrine-related cancer 2008, 15, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franke, T.F.; Hornik, C.P.; Segev, L.; Shostak, G.A.; Sugimoto, C. PI3K/Akt and apoptosis: size matters. Oncogene 2003, 22, 8983–8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D.; Okada, H.; Ruland, J.; Liu, L.; Stambolic, V.; Mak, T.W.; Ingram, A.J. Akt is activated in response to an apoptotic signal. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2001, 276, 30461–30466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrid, L.V.; Wang, C.Y.; Guttridge, D.C.; Schottelius, A.J.; Baldwin Jr, A.S.; Mayo, M.W. Akt suppresses apoptosis by stimulating the transactivation potential of the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB. Molecular and cellular biology 2000, 20, 1626–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sousa Mesquita, A.P.; de Araújo Lopes, S.; Pernambuco Filho, P.C.A.; Nader, H.B.; Lopes, C.C. Acquisition of anoikis resistance promotes alterations in the Ras/ERK and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways and matrix remodeling in endothelial cells. Apoptosis 2017, 22, 1116–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, M.; Zhao, H.; Han, Z.C. Signalling mechanisms of anoikis. Histology and histopathology 19, 973–983.

- Horowitz, J.C.; Rogers, D.S.; Sharma, V.; Vittal, R.; White, E.S.; Cui, Z.; Thannickal, V.J. Combinatorial activation of FAK and AKT by transforming growth factor-β1 confers an anoikis-resistant phenotype to myofibroblasts. Cellular signalling 2007, 19, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Meng, X.; Jin, Y.; Bai, J.; Zhao, Y.; Cui, X.; Chen, F.; Fu, S. Inhibitory role of focal adhesion kinase on anoikis in the lung cancer cell A549. Cell biology international 2008, 32, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.H.; Shih, H.C.; Hsieh, P.W.; Chang, F.R.; Wu, Y.C.; Wu, C.C. HPW-RX40 restores anoikis sensitivity of human breast cancer cells by inhibiting integrin/FAK signaling. Toxicology and applied pharmacology 2015, 289, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentijn, A.J.; Gilmore, A.P. Translocation of full-length Bid to mitochondria during anoikis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2004, 279, 32848–32857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chota, A.; George, B.P.; Abrahamse, H. Interactions of multidomain pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins in cancer cell death. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistritto, G.; Trisciuoglio, D.; Ceci, C.; Garufi, A.; D’Orazi, G. Apoptosis as anticancer mechanism: function and dysfunction of its modulators and targeted therapeutic strategies. Aging (albany NY) 2016, 8, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsujimoto, Y. Cell death regulation by the Bcl-2 protein family in the mitochondria. Journal of cellular physiology 2003, 195, 158–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, S.M.; Vuori, K.; Kelaita, D.; Sicks, S. A role for Jun-N-terminal kinase in anoikis; suppression by bcl-2 and crmA. The Journal of cell biology 1996, 135, 1377–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, K.; Rak, J.; Leung, T.; Dean, N.M.; Kerbel, R.S.; Filmus, J. Activated ras Prevents Downregulation of Bcl-XL Triggered by Detachment from the Extracellular MatrixA Mechanism of ras-Induced Resistance to Anoikis in Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Journal of Cell Biology 2000, 149, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coll, M.L.; Rosen, K.; Ladeda, V.; Filmus, J. Increased Bcl-xL expression mediates v-Src-induced resistance to anoikis in intestinal epithelial cells. Oncogene 2002, 21, 2908–2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, N.T.; Yamaguchi, H.; Lee, F.Y.; Bhalla, K.N.; Wang, H.G. Anoikis, initiated by Mcl-1 degradation and Bim induction, is deregulated during oncogenesis. Cancer research 2007, 67, 10744–10752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irmler, M.; Thome, M.; Hahne, M.; Schneider, P.; Hofmann, K.; Steiner, V.; Bodmer, J.-L.; Schröter, M.; Burns, K.; Mattmann, C.; et al. Inhibition of death receptor signals by cellular FLIP. Nature 1997, 388, 190–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippo, M.R.; Moretti, S.; Vescovi, S.; Tomasetti, M.; Orecchia, S.; Amici, G.; Catalano, A.; Procopio, A. FLIP overexpression inhibits death receptor-induced apoptosis in malignant mesothelial cells. Oncogene 2004, 23, 7753–7760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolcet, X.; Llobet, D.; Pallares, J.; Rue, M.; Comella, J.X.; Matias-Guiu, X. FLIP is frequently expressed in endometrial carcinoma and has a role in resistance to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Laboratory investigation 2005, 85, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safa, A.R. c-FLIP, a master anti-apoptotic regulator. Experimental oncology 2012, 34, 176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mathas, S.; Lietz, A.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Hummel, F.; Wiesner, B.; Janz, M.; Jundt, F.; Hirsch, B.; Jöhrens-Leder, K.; Vornlocher, H.-P.; et al. c-FLIP mediates resistance of Hodgkin/Reed-Sternberg cells to death receptor–induced apoptosis. The Journal of experimental medicine 2004, 199, 1041–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawji, I.A.; Simpson, C.D.; Hurren, R.; Gronda, M.; Williams, M.A.; Filmus, J.; Jonkman, J.; Da Costa, R.S.; Wilson, B.C.; Thomas, M.P.; et al. Critical Role for Fas-Associated Death Domain–Like Interleukin-1–Converting Enzyme–Like Inhibitory Protein in Anoikis Resistance and Distant Tumor Formation. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 2007, 99, 811–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, A.M.; Reisfeld, R.A.; Cheresh, D.A. Integrin alpha v beta 3 rescues melanoma cells from apoptosis in three-dimensional dermal collagen. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1994, 91, 8856–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, L.; Francolini, M.; Marthyn, P.; Zhang, J.; Carroll, R.S.; Nikas, D.C.; Strasser, J.F.; Villani, R.; Cheresh, D.A.; Black, P.M. αvβ3 and αvβ5 integrin expression in glioma periphery. Neurosurgery 2001, 49, 380–390. [Google Scholar]

- Felding-Habermann, B.; O'Toole, T.E.; Smith, J.W.; Fransvea, E.; Ruggeri, Z.M.; Ginsberg, M.H.; Hughes, P.E.; Pampori, N.; Shattil, S.J.; Saven, A.; et al. Integrin activation controls metastasis in human breast cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2001, 98, 1853–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinschek, R.; Hingerl, J.; Benge, A.; Zafiu, C.; Schüren, E.; Ehmoser, E.K.; Lössner, D.; Reuning, U. Constitutive activation of integrin αvβ3 contributes to anoikis resistance of ovarian cancer cells. Molecular Oncology 2021, 15, 503–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, R.C.; Bellovin, D.I.; Brown, C.; Maynard, E.; Wu, B.; Kawakatsu, H.; Sheppard, D.; Oettgen, P.; Mercurio, A.M. Transcriptional activation of integrin β6 during the epithelial-mesenchymal transition defines a novel prognostic indicator of aggressive colon carcinoma. The Journal of clinical investigation 2005, 115, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.; Watt, F.M.; Speight, P.M. Changes in the expression of αv integrins in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Journal of oral pathology & medicine 1997, 26, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia-Expósito, A.; Gómez-Lamarca, M.J.; Widmann, T.J.; Martín-Bermudo, M.D. Integrins cooperate with the EGFR/Ras pathway to preserve epithelia survival and architecture in development and oncogenesis. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2022, 10, 892691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braunholz, D.; Saki, M.; Niehr, F.; Öztürk, M.; Puértolas, B.B.; Konschak, R.; Budach, V.; Tinhofer, I. Spheroid culture of head and neck cancer cells reveals an important role of EGFR signalling in anchorage independent survival. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0163149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jost, M.; Huggett, T.M.; Kari, C.; Rodeck, U. Matrix-independent survival of human keratinocytes through an EGF receptor/MAPK-kinase-dependent pathway. Molecular biology of the cell 2001, 12, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-Montero, C.M.; Wygant, J.N.; McIntyre, B.W. PI3-K/Akt-mediated anoikis resistance of human osteosarcoma cells requires Src activation. European Journal of Cancer 2006, 42, 1491–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, Z.; Dake, C.; Tanaka, K.; Shuixiang, H. EGFL7 as a novel therapeutic candidate regulates cell invasion and anoikis in colorectal cancer through PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. International Journal of Clinical Oncology 2021, 26, 1099–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; He, J. Metabolic reprogramming and signaling adaptations in anoikis resistance: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2025, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppicelli, S.; Kersikla, T.; Menegazzi, G.; Andreucci, E.; Ruzzolini, J.; Nediani, C.; Bianchini, F.; Calorini, L. The critical role of glutamine and fatty acids in the metabolic reprogramming of anoikis-resistant melanoma cells. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 15, 1422281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Tian, Z.; Chueh, P.J.; Chen, S.; Morré, D.M.; Morré, D.J. Alternative splicing as the basis for specific localization of tNOX, a unique hydroquinone (NADH) oxidase, to the cancer cell surface. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 12337–12346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morré, DJ; Morré, D.M. Cancer Therapeutic Applications of ENOX2 Proteins. ECTO-NOX Proteins: Growth, Cancer, and Aging, 345-417.

- Shiraishi, T.; Verdone, J.E.; Huang, J.; Kahlert, U.D.; Hernandez, J.R.; Torga, G.; Zarif, J.C.; Epstein, T.; Gatenby, R.; McCartney, A.; et al. Glycolysis is the primary bioenergetic pathway for cell motility and cytoskeletal remodeling in human prostate and breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 2014, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, J.A.; Hagel, K.R.; Hawk, M.A.; Schafer, Z.T. Metabolism during ECM detachment: achilles heel of cancer cells? Trends in cancer 2017, 3, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Ji, X.; Wang, Y. ENO2 promotes anoikis resistance in anaplastic thyroid cancer by maintaining redox homeostasis. Gland Surgery 2024, 13, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-J.; Yang, W.; Gong, M.; He, Y.; Xu, D.; Chen, J.-X.; Chen, W.-J.; Li, W.-Y.; Wang, Y.-Q.; Dong, K.-Q.; et al. ENO2 affects the EMT process of renal cell carcinoma and participates in the regulation of the immune microenvironment. Oncology Reports 2022, 49, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, Z.; Yan, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Z.; Ma, Z. Integration of autophagy and anoikis resistance in solid tumors. The Anatomical Record 2013, 296, 1501–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.L.; David, J.; Cook-Spaeth, D.; Casey, S.; Cohen, D.; Selvendiran, K.; Bekaii-Saab, T.; Hays, J.L. Autophagy induction results in enhanced anoikis resistance in models of peritoneal disease. Molecular Cancer Research 2017, 15, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulia, S.; Chandra, P.; Das, A. The prognosis of cancer depends on the interplay of autophagy, apoptosis, and anoikis within the tumor microenvironment. Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics 2023, 81, 621–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Liu, B.; Li, X.; Lu, D.; Yang, L.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.; Cheng, L.; Lv, F.; Zhang, P.; et al. ATF4/CEMIP/PKCα promotes anoikis resistance by enhancing protective autophagy in prostate cancer cells. Cell death & disease 2022, 13, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Palabiyik, A.A. The role of Bcl-2 in controlling the transition between autophagy and apoptosis. Molecular Medicine Reports 2025, 32, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brokatzky, D.; Mostowy, S. Rearranging to resist cell death. eLife 2024, 13, e104942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, C.Y.; Yu, J.; Guan, K.L. Cell detachment activates the Hippo pathway via cytoskeleton reorganization to induce anoikis. Genes & development 2012, 26, 54–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, S.; Zhu, D.; Li, H.; Miao, X.; Gu, M.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, W.; Shen, R.; et al. The crosstalk between anoikis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition and their synergistic roles in predicting prognosis in colon adenocarcinoma. Frontiers in Oncology 2023, 13, 1184215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frisch, S.M.; Schaller, M.; Cieply, B. Mechanisms that link the oncogenic epithelial–mesenchymal transition to suppression of anoikis. Journal of cell science 2013, 126, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltai, T.; Fliegel, L.; Reshkin, S.J., Baltazar, F., Cardone, R.A., Alfarouk, K.O., Afonso, J. pH deregulation as the eleventh hallmark of cancer. Book. Publisher: Elsevier.

- Wang, S.; Lv, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ling, J.; Wang, H.; Gu, D.; Wang, C.; Qin, W.; Zheng, X.; Jin, H. Acidic extracellular pH induces autophagy to promote anoikis resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via downregulation of miR-3663-3p. Journal of Cancer 2021, 12, 3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peppicelli, S.; Ruzzolini, J.; Bianchini, F.; Andreucci, E.; Nediani, C.; Laurenzana, A.; Margheri, F.; Fibbi, G.; Calorini, L. Anoikis Resistance as a Further Trait of Acidic-Adapted Melanoma Cells. Journal of Oncology 2019, 2019, 8340926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeshakin, F.O.; Adeshakin, A.O.; Liu, Z.; Lu, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, P.; Yan, D.; Zhang, G.; Wan, X. Upregulation of V-ATPase by STAT3 activation promotes anoikis resistance and tumor metastasis. Journal of Cancer 2021, 12, 4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanvorachote, P.; Nimmannit, U.; Lu, Y.; Talbott, S.; Jiang, B.H.; Rojanasakul, Y. Nitric oxide regulates lung carcinoma cell anoikis through inhibition of ubiquitin-proteasomal degradation of caveolin-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2009, 284, 28476–28484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Miao, J.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, E.; Shi, L.; Ai, S.; Wang, F.; Kang, X.; Chen, H.; Lu, X.; et al. NADPH oxidase 4 regulates anoikis resistance of gastric cancer cells through the generation of reactive oxygen species and the induction of EGFR. Cell death & disease 2018, 9, 948. [Google Scholar]

- Grünewald, T.G.; Cidre-Aranaz, F.; Surdez, D.; Tomazou, E.M.; de Álava, E.; Kovar, H.; Dirksen, U. Ewing sarcoma. Nature reviews Disease primers 2018, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hughes, C.S.; Delaidelli, A.; Huang, Y.Z.; Shyp, T.; Yang, X.; Sorensen, P.H. Abstract PR002: Identification of metabolic adaptation mechanisms that drive anoikis suppression and metastasis in Ewing sarcoma. Cancer Research 2023, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, Z.S.; Shojaeian, A.; Nahand, J.S.; Bayat, M.; Taghizadieh, M.; Rostamian, M.; Babaei, F.; Moghoofei, M. Oncoviruses: induction of cancer development and metastasis by increasing anoikis resistance. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakavandi, E.; Shahbahrami, R.; Goudarzi, H.; Eslami, G.; Faghihloo, E. Anoikis resistance and oncoviruses. Journal of cellular biochemistry 2018, 119, 2484–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, C.S.L.; Yung, M.M.H.; Hui, L.M.N.; Leung, L.L.; Liang, R.; Chen, K.; Liu, S.S.; Qin, Y.; Leung, T.H.Y.; Lee, K.-F.; et al. MicroRNA-141 enhances anoikis resistance in metastatic progression of ovarian cancer through targeting KLF12/Sp1/survivin axis. Molecular cancer 2017, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, S.F. The Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 in stress-induced signal transduction: implications for cell proliferation and cell death. Pflügers Archiv 2006, 452, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.J.; Lyons, J.C.; Ohtsubo, T.; Song, C.W. Acidic environment causes apoptosis by increasing caspase activity. British journal of cancer 1999, 80, 1892–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlieb, R.A.; Nordberg, J.; Skowronski, E.; Babior, B.M. Apoptosis induced in Jurkat cells by several agents is preceded by intracellular acidification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1996, 93, 654–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuyama, S.; Llopis, J.; Deveraux, Q.L.; Tsien, R.Y.; Reed, J.C. Changes in intramitochondrial and cytosolic pH: early events that modulate caspase activation during apoptosis. Nature cell biology 2000, 2, 318–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segal, M.S.; Beem, E. Effect of pH, ionic charge, and osmolality on cytochrome c-mediated caspase-3 activity. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2001, 281, C1196–C1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slepkov, E.; Fliegel, L. Structure and function of the NHE1 isoform of the Na+/H+ exchanger. Biochemistry and cell biology 2002, 80, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Lou, J.; Jin, Z.; Yang, X.; Shan, W.; Du, Q.; Liao, Q.; Xu, J.; Xie, R. Advances in research on the regulatory mechanism of NHE1 in tumors. Oncology Letters 2021, 21, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pawson, T.; Letwin, K.; Lee, T.; Hao, Q.L.; Heisterkamp, N.; Groffen, J. The FER gene is evolutionarily conserved and encodes a widely expressed member of the FPS/FES protein-tyrosine kinase family. Molecular and cellular biology 1989, 9, 5722–5725. [Google Scholar]

- AIvanova, I.; Vermeulen, J.F.; Ercan, C.; Houthuijzen, J.M.; ASaig, F.; Vlug, E.J.; van der Wall, E.; van Diest, P.J.; Vooijs, M.; Derksen, P.W.B. FER kinase promotes breast cancer metastasis by regulating α6-and β1-integrin-dependent cell adhesion and anoikis resistance. Oncogene 2013, 32, 5582–5592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Truesdell, P.; Meens, J.; Kadish, C.; Yang, X.; Boag, A.H.; Craig, A.W. Fer protein-tyrosine kinase promotes lung adenocarcinoma cell invasion and tumor metastasis. Molecular Cancer Research 2013, 11, 952–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubeidi, A.; Rocha, J.; Zouanat, F.Z.; Hamel, L.; Scarlata, E.; Aprikian, A.G.; Chevalier, S. The Fer tyrosine kinase cooperates with interleukin-6 to activate signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and promote human prostate cancer cell growth. Molecular Cancer Research 2009, 7, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Zhang, S.; Gao, Y.; Greer, P.A.; Tonks, N.K. HGF-independent regulation of MET and GAB1 by nonreceptor tyrosine kinase FER potentiates metastasis in ovarian cancer. Genes & development 2016, 30, 1542–1557. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Chen, L.; Hou, L.; Zhao, X.; et al. FER-mediated phosphorylation and PIK3R2 recruitment on IRS4 promotes AKT activation and tumorigenesis in ovarian cancer cells. Elife 2022, 11, e76183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaw, P.; Bhowmik, A.D.; Pillai, M.S.G.; Robbins, N.; Dwivedi, S.K.D.; Rao, G. Anoikis resistance in cancer: mechanisms, therapeutic strategies, potential targets, and models for enhanced Understanding. Cancer Letters 2025, 624, 217750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derksen, P.W.; Liu, X.; Saridin, F.; van der Gulden, H.; Zevenhoven, J.; Evers, B.; van Beijnum, J.R.; Griffioen, A.W.; Vink, J.; Krimpenfort, P.; et al. Somatic inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 in mice leads to metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma through induction of anoikis resistance and angiogenesis. Cancer cell 2006, 10, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Fleishman, J.S.; Chen, J.; Tang, H.; Chen, Z.-S.; Chen, W.; Ding, M. Targeting anoikis resistance as a strategy for cancer therapy. Drug Resistance Updates 2024, 101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schempp, C.M.; von Schwarzenberg, K.; Schreiner, L.; Kubisch, R.; Müller, R.; Wagner, E.; Vollmar, A.M. V-ATPase inhibition regulates anoikis resistance and metastasis of cancer cells. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2014, 13, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, B.; Schwenk, R.; Bräutigam, J.; Müller, R.; Menche, D.; Bischoff, I.; Fürst, R. The vacuolar-type ATPase inhibitor archazolid increases tumor cell adhesion to endothelial cells by accumulating extracellular collagen. PLoS one 2018, 13, e0203053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, V.; Licon-Munoz, Y.; Trujillo, K.; Bisoffi, M.; Parra, K.J. Inhibitors of vacuolar ATPase proton pumps inhibit human prostate cancer cell invasion and prostate-specific antigen expression and secretion. International journal of cancer 2013, 132, E1–E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotter, K.; Capecci, J.; Sennoune, S.; Huss, M.; Maier, M.; Martinez-Zaguilan, R.; Forgac, M. Activity of plasma membrane V-ATPases is critical for the invasion of MDA-MB231 breast cancer cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2015, 290, 3680–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, T.; Tajima, H.; Yachie, A.; Yokoyama, K.; Elnemr, A.; Fushida, S.; Kitagawa, H.; Kayahara, M.; Nishimura, G.; Miwa, K.; et al. Activated lansoprazole inhibits cancer cell adhesion to extracellular matrix components. International journal of oncology 1999, 15, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschesnes, R.G.; Patenaude, A.; Rousseau, J.L.C.; Fortin, J.S.; Ricard, C.; Côté, M.-F.; Huot, J.; C-Gaudreault, R.; Petitclerc, E. Microtubule-destabilizing agents induce focal adhesion structure disorganization and anoikis in cancer cells. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2007, 320, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momin, S.; Nagaraju, G.P. PIK3-AKT and Its Role in Pancreatic Cancer. In Role of Tyrosine Kinases in Gastrointestinal Malignancies; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2018; pp. 57–61. [Google Scholar]

- Stanciu, S.; Ionita-Radu, F.; Stefani, C.; Miricescu, D.; Stanescu-Spinu, I.-I.; Greabu, M.; Totan, A.R.; Jinga, M. Targeting PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer: from molecular to clinical aspects. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 10132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaki, M.; Oshimura, M.A.; Ito, H. PI3K-Akt pathway: its functions and alterations in human cancer. Apoptosis 2004, 9, 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pungsrinont, T.; Kallenbach, J.; Baniahmad, A. Role of PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway as a pro-survival signaling and resistance-mediating mechanism to therapy of prostate cancer. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 11088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, W.; Hu, J.; Lu, C.; Liu, Y. PI3K/AKT pathway as a key link modulates the multidrug resistance of cancers. Cell death & disease 2020, 11, 797. [Google Scholar]

- Rascio, F.; Spadaccino, F.; Rocchetti, M.T.; Castellano, G.; Stallone, G.; Netti, G.S.; Ranieri, E. The pathogenic role of PI3K/AKT pathway in cancer onset and drug resistance: an updated review. Cancers 2021, 13, 3949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehra, S.; Deshpande, N.; Nagathihalli, N. Targeting PI3K pathway in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: rationale and progress. Cancers 2021, 13, 4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoukian, P.; Bijlsma, M.; Van Laarhoven, H. The cellular origins of cancer-associated fibroblasts and their opposing contributions to pancreatic cancer growth. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2021, 9, 743907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierie, B.; Moses, H.L. Tumour microenvironment: TGFbeta: the molecular Jekyll and Hyde of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 506–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, V.; Reni, M.; Ychou, M.; Richel, D.J.; Macarulla, T.; Ducreux, M. Tumour-stroma interactions in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: rationale and current evidence for new therapeutic strategies. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2014, 40, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorchs, L.; Kaipe, H. Interactions between cancer-associated fibroblasts and T cells in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment and the role of chemokines. Cancers 2021, 13, 2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, A.; Song, J.; Thakur, N.; Itoh, S.; Marcusson, A.; Bergh, A.; Heldin, C.-H.; Landström, M. TGF-β promotes PI3K-AKT signaling and prostate cancer cell migration through the TRAF6-mediated ubiquitylation of p85α. Science signaling 2017, 10, eaal4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, J.; Landström, M. TGFβ activates PI3K-AKT signaling via TRAF6. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 99205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornitz, D.M.; Itoh, N. The fibroblast growth factor signaling pathway. In Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Developmental Biology; 2015; Volume 4, pp. 215–266. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Lian, Y.; Xie, K.; Cai, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, Y. Ropivacaine suppresses tumor biological characteristics of human hepatocellular carcinoma via inhibiting IGF-1R/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling axis. Bioengineered 2021, 12, 9162–9173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Bajraszewski, N.; Wu, E.; Wang, H.; Moseman, A.P.; Dabora, S.L.; Griffin, J.D.; Kwiatkowski, D.J. PDGFRs are critical for PI3K/Akt activation and negatively regulated by mTOR. The Journal of clinical investigation 2007, 117, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fofaria, N.M.; Srivastava, S.K. Inhibition of STAT-3 by piperlongumine induces anoikis, prevents tumor formation in pancreatic cancer in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Research 2014, 74, 1233–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegeye, M.M.; Lindkvist, M.; Fälker, K.; Kumawat, A.K.; Paramel, G.; Grenegård, M.; Sirsjö, A.; Ljungberg, L.U.U. Activation of the JAK/STAT3 and PI3K/AKT pathways are crucial for IL-6 trans-signaling-mediated pro-inflammatory response in human vascular endothelial cells. Cell Communication and Signaling 2018, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Zhang, H.; Wen, Z.; Gu, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, T.; Jia, C.; Lu, Z.; Chen, J. Retinoic acid inhibits pancreatic cancer cell migration and EMT through the downregulation of IL-6 in cancer associated fibroblast cells. Cancer letters 2014, 345, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Kim, J.Y.; Oh, E.; Lee, N.; Cho, Y.; Seo, J.H. Salinomycin promotes anoikis and decreases the CD44+/CD24-stem-like population via inhibition of STAT3 activation in MDA-MB-231 cells. PloS one 2015, 10, e0141919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, H.; Duan, C.; Liu, D.; Qian, L.; Yang, Z.; Guo, L.; Song, L.; Yu, M.; Hu, M.; et al. Deficiency of Erbin induces resistance of cervical cancer cells to anoikis in a STAT3-dependent manner. Oncogenesis 2013, 2, e52–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palollathil, A.; Dagamajalu, S.; Ahmed, M.; Vijayakumar, M.; Prasad, T.S. K.; Raju, R. The network map of mucin 1 mediated signaling in cancer progression and immune modulation. Discover Oncology 2025, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, M.; Sanders, A.; De, C.; Zhou, R.; Lala, P.; Shwartz, S.; Mitra, B.; Brouwer, C.; Mukherjee, P. Targeting tumor-associated MUC1 overcomes anoikis-resistance in pancreatic cancer. Translational Research 2023, 253, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, M.; Grover, P.; Sanders, A.J.; Zhou, R.; Ahmad, M.; Shwartz, S.; Lala, P.; Nath, S.; Yazdanifar, M.; Brouwer, C.; et al. Overexpression of MUC1 induces non-canonical TGF-β signaling in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 2022, 10, 821875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liau, S.S.; Jazag, A.; Ito, K.; Whang, E.E. Overexpression of HMGA1 promotes anoikis resistance and constitutive Akt activation in pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. British journal of cancer 2007, 96, 993–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Pan, T.-H.; Xu, S.; Jia, L.-T.; Zhu, L.-L.; Mao, J.-S.; Zhu, Y.-L.; Cai, J.-T. The virus-induced protein APOBEC3G inhibits anoikis by activation of Akt kinase in pancreatic cancer cells. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 12230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; He, Z.; Zhu, C.; Chen, S.; Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Bi, N.; Yu, C.; Sun, C. MiR-137 promotes anoikis through modulating the AKT signaling pathways in Pancreatic Cancer. J Cancer 2020, 11, 6277–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernesti, A.; Heydel, B.; Blümke, J.; Gutschner, T.; Hämmerle, M. FOXM1 regulates platelet-induced anoikis resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. bioRxiv 2024, 2024–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, D.; Pan, X.; Chu, Y.; Yin, J. FOXM1 transcriptional regulation of RacGAP1 activates the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway to promote the proliferation, migration, and invasion of cervical cancer cells. International Journal of Clinical Oncology 2024, 29, 333–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutano, V.; Chia, M.L.; Wigmore, E.M.; Hopcroft, L.; Williamson, S.C.; Christie, A.L.; Willis, B.; Kerr, J.; Ashforth, J.; Fox, R.; et al. The interplay between FOXO3 and FOXM1 influences sensitivity to AKT inhibition in PIK3CA and PIK3CA/PTEN altered estrogen receptor positive breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer 2025, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, J.M.; Mortenson, M.M.; Bowles, T.L.; Virudachalam, S.; Bold, R.J. ERK/BCL-2 pathway in the resistance of pancreatic cancer to anoikis. Journal of Surgical Research 2009, 152, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, S.J.; Stuart, K.; Gilley, R.; Sale, M.J. Control of cell death and mitochondrial fission by ERK 1/2 MAP kinase signalling. The FEBS journal 2017, 284, 4177–4195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Palmfeldt, J.; Lin, L.; Colaço, A.; Clemmensen, K.K.B.; Huang, J.; Xu, F.; Liu, X.; Maeda, K.; Luo, Y.; et al. STAT3 associates with vacuolar H+-ATPase and regulates cytosolic and lysosomal pH. Cell Research 2018, 28, 996–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.W.; Wang, S.W.; Ghishan, F.K.; Kiela, P.R.; Tang, M.J. Cell confluency-induced Stat3 activation regulates NHE3 expression by recruiting Sp1 and Sp3 to the proximal NHE3 promoter region during epithelial dome formation. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology 2009, 296, C13–C24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Luan, S.; Yao, Y.; Qin, T.; Xu, X.; Shen, Z.; Yao, R.; Yue, L. NHE1 mediates 5-Fu resistance in gastric cancer via STAT3 signaling pathway. OncoTargets and therapy 2020, 8521–8532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossmannova, K.; Belvoncikova, P.; Puzderova, B.; Simko, V.; Csaderova, L.; Pastorek, J.; Barathova, M. Carbonic anhydrase IX downregulation linked to disruption of HIF-1, NFκB and STAT3 pathways as a new mechanism of ibuprofen anti-cancer effect. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0323635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Yang, G.; Jiang, T.; Zhu, G.; Li, H.; Qiu, Z. The effects and mechanisms of blockage of STAT3 signaling pathway on IL-6 inducing EMT in human pancreatic cancer cells in vitro. Neoplasma 2011, 58, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Hu, Z.; Yang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Xie, L.; Chen, C.; Guo, Y.; Bai, Y. STAT3 inhibition enhances gemcitabine sensitivity in pancreatic cancer by suppressing EMT, immune escape and inducing oxidative stress damage. International immunopharmacology 2023, 123, 110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Huang, C. Regulation of EMT by STAT3 in gastrointestinal cancer. International Journal of Oncology 2017, 50, 753–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Amico, S.; Kirillov, V.; Petrenko, O.; Reich, N.C. STAT3 is a genetic modifier of TGF-beta induced EMT in KRAS mutant pancreatic cancer. Elife 2024, 13, RP92559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinarello, A.; Betto, R.M.; Diamante, L.; Tesoriere, A.; Ghirardo, R.; Cioccarelli, C.; Argenton, F. STAT3 and HIF1α cooperatively mediate the transcriptional and physiological responses to hypoxia. Cell death discovery 2023, 9, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grillo, M.; Palmer, C.; Holmes, N.; Sang, F.; Larner, A.C.; Bhosale, R.; Shaw, P.E. Stat3 oxidation-dependent regulation of gene expression impacts on developmental processes and involves cooperation with Hif-1α. Plos one 2020, 15, e0244255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, R.; Özen, I.; Barbariga, M.; Gaceb, A.; Roth, M.; Paul, G. STAT3 precedes HIF1α transcriptional responses to oxygen and oxygen and glucose deprivation in human brain pericytes. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0194146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.L.; Cassone, M.; Otvos, L., Jr.; Vogiatzi, P. HIF-1α and STAT3 client proteins interacting with the cancer chaperone Hsp90: Therapeutic considerations. Cancer biology & therapy 2008, 7, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, G.; Ma, Y. Anoikis-related gene signature for prognostication of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a multi-omics exploration and verification study. Cancers 2023, 15, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vankelecom, H.; Van Eijsden, R.; Govaere, O.; Topal, B. Molecular markers associated with outcome and metastasis in human pancreatic cancer. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2012, 31, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lv, X.; Guo, X.; Dong, Y.; Peng, P.; Huang, F.; Wang, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. Feedback activation of STAT3 limits the response to PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors in PTEN-deficient cancer cells. Oncogenesis 2021, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Wang, R.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Niu, L.; Guo, M.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Tang, X. Curcumol: a review of its pharmacology, pharmacokinetics, drug delivery systems, structure–activity relationships, and potential applications. Inflammopharmacology 2024, 32, 1659–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-L.; Huang, C.-W.; Ko, C.-J.; Fang, S.-Y.; Ou-Yang, F.; Pan, M.-R.; Luo, C.-W.; Hou, M.-F. Curcumol suppresses triple-negative breast cancer metastasis by attenuating anoikis resistance via inhibition of skp2-mediated transcriptional addiction. Anticancer Research 2020, 40, 5529–5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Li, A.; Liao, G.; Yang, F.; Yang, J.; Chen, X.; Jiang, X. Curcumol triggers apoptosis of p53 mutant triple-negative human breast cancer MDA-MB 231 cells via activation of p73 and PUMA. Oncology letters 2017, 14, 1080–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Fan, D.; Xu, Y.; Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, X.; Lu, J.; Zhang, C.; Han, J.; et al. Curcumol enhances the sensitivity of doxorubicin in triple-negative breast cancer via regulating the miR-181b-2-3p-ABCC3 axis. Biochemical Pharmacology 2020, 174, 113795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Xu, W.; Ding, J.; Li, L.; You, X.; Wu, Y.; He, Q. Curcumol inhibits the malignant progression of prostate cancer and regulates the PDK1/AKT/mTOR pathway by targeting miR-9. Oncology Reports 2021, 46, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Tao, Y.; Li, X.; Qin, J.; Bai, Z.; Chi, B.; Yan, W.; Chen, X. Curcumol inhibits colorectal cancer proliferation by targeting miR-21 and modulated PTEN/PI3K/Akt pathways. Life sciences 2019, 221, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terasaki, M.; Maeda, H.; Miyashita, K.; Mutoh, M. Induction of anoikis in human colorectal cancer cells by fucoxanthinol. Nutrition and Cancer 2017, 69, 1043–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terasaki, M.; Inoue, T.; Murase, W.; Kubota, A.; Kojima, H.; Kojoma, M.; Ohta, T.; Maeda, H.; Miyashita, K.; Mutoh, M.; et al. Fucoxanthinol induces apoptosis in a pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia cell line. Cancer Genomics & Proteomics 2021, 18, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, M.; Varalakshmi, K.N. Apoptosis induction in cancer cell lines by the carotenoid Fucoxanthinol from Pseudomonas stutzeri JGI 52. Indian journal of pharmacology 2018, 50, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Konishi, I.; Hosokawa, M.; Sashima, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Miyashita, K. Halocynthiaxanthin and fucoxanthinol isolated from Halocynthia roretzi induce apoptosis in human leukemia, breast and colon cancer cells. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Toxicology & Pharmacology 2006, 142(1-2), 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.H.; Wang, Y.; Lee, S.J.; Jin, M.H.; Sun, H.N.; Kwon, T. Regulation of anoikis by extrinsic death receptor pathways. Cell Communication and Signaling 2023, 21, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondar, V.M.; McConkey, D.J. Anoikis is regulated by BCL-2-independent pathways in human prostate carcinoma cells. The Prostate 2002, 51, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Wu, J.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, K.; Tian, D.; Liu, J.; Liao, J. HRC promotes anoikis resistance and metastasis by suppressing endoplasmic reticulum stress in hepatocellular carcinoma. International Journal of Medical Sciences 2021, 18, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eguchi, R.; Fujita, Y.; Tabata, C.; Ogawa, H.; Wakabayashi, I.; Nakano, T.; Fujimori, Y. Inhibition of Src family kinases overcomes anoikis resistance induced by spheroid formation and facilitates cisplatin-induced apoptosis in human mesothelioma cells. Oncology Reports 2015, 34, 2305–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.J.; He, Y.F.; Han, X.H.; Hu, B. Dasatinib suppresses invasion and induces apoptosis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. International journal of clinical and experimental pathology 2015, 8, 7818. [Google Scholar]