1. Introduction

Human female reproductive aging is basically caused by ovarian aging (OA) because uterine function, except for specific pathologies, remains unchanged even in postmenopausal women, as witnessed by virtually age-independent high live birth rates after transfer of embryos resulting from oocytes donated by young women [

1]. OA, marked by decreased fertility related to impaired oocyte quantity and quality, is a physiological process. However, in the context of the current trend of delaying motherhood because of different societal constraints, together with the fact that it may occur prematurely in the women’s life [

2], OA is at the origin of serious emotional discomfort in women who wish to procreate. Beyond the fertility issues, several studies reported adverse effects of ovarian aging on different fertility-unrelated functions of the female body, entailing higher risk for almost every chronic age-related general health issue, such as osteoporosis, neurodegeneration, and cardiovascular diseases [

3], vasomotor symptoms (e.g., hotflashes and night sweats), and increased risk of diabetes and high blood pressure [

4,

5]. Thus, ovarian aging, along with a longer life expectance of women as compared to men, could be one of the underlying drivers of the so-called mortality–morbidity paradox, meaning that women usually live longer but less comfortably as men do [

6]. This situation calls for an urgent action to improve the current status of counteracting OA, both as to fertility preservation and general health and wellbeing improvement of the affected women [

7].

Many studies addressed different aspects of OA in search of more effective preventive and therapeutic methods. However, much still remains to be done in both of these directions. Clearly, OA has a strong genetic and epigenetic background, reviewed previously [

2,

8,

9,

10], which is specific for each woman so that any preventive and therapeutic action needs to be patient-tailored in the sense of modern precision medicine. This study briefly resumes the basic characteristics of OA in women, exhaustively reviewed recently [

2,

6,

11,

12,

13], with a particular attention to updating on ultimate research findings, not included in the previous reviews, and those that may become clues to forthcoming therapeutic action. Experimental animal data are mentioned only marginally when useful for the understanding the context of human clinical studies.

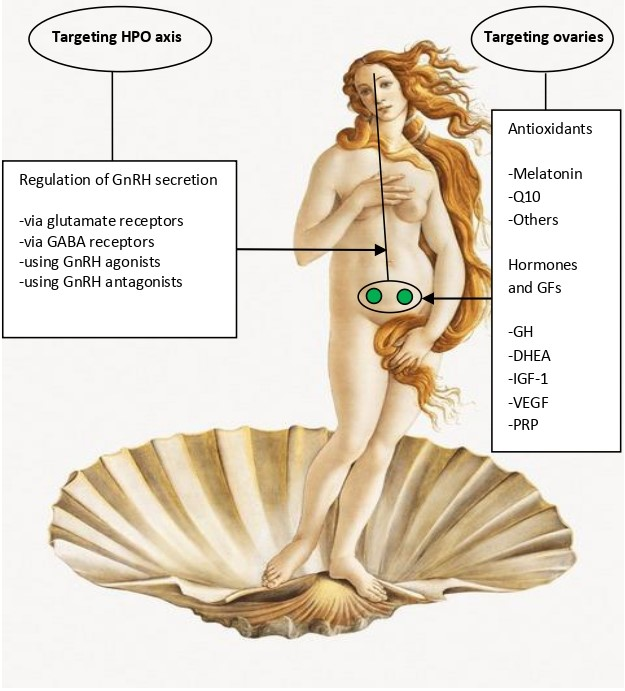

2. Basic Mechanisms of OA as Possible Therapeutic Targets

OA is characterized by two simultaneously occurring phenomena: disruption of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis and the loss of ovarian follicle and oocyte quantity and quality (reviewed in Wang et al. [

11]). Even though some earlier studies, performed in rodents, suggested that OA is primarily triggered by the disturbance of the HPO axis and ovarian damage is its consequence [

14,

15], this view is currently not generally accepted, and it is admitted that the HPO dysfunction may be the consequence rather than the cause of ovarian failure. Yet, the correct answer to this dilemma is of essential importance for the choice of optimal strategies to be used in OA therapy. In the absence of the definite knowledge of the primary OA trigger, current therapies are targeted on both the HPO axis and the function of ovarian cells (Table1). These two strategies are further explained below (subsections 2.1. and 2.2).

2.1. Targeting the HPO Axis

Similar to rodents, HPO axis was also shown to be altered in perimenopausal women. As compared to healthy young women, most aged women approaching the menopause failed to generate an LH surge in response to estradiol challenge [

16]. Moreover, a gradual increase in gonadotropin secretion was observed to start as early as at the age of 27-28 years and to be accelerated dramatically after 49, concerning mainly FSH rather than LH [

17]. The changes in gonadotropin secretion precede any detectable menstruation or ovulation failure and appear to result from an altered secretion pattern of gonadotropin-releasing hormone GnRH [

18,

19].

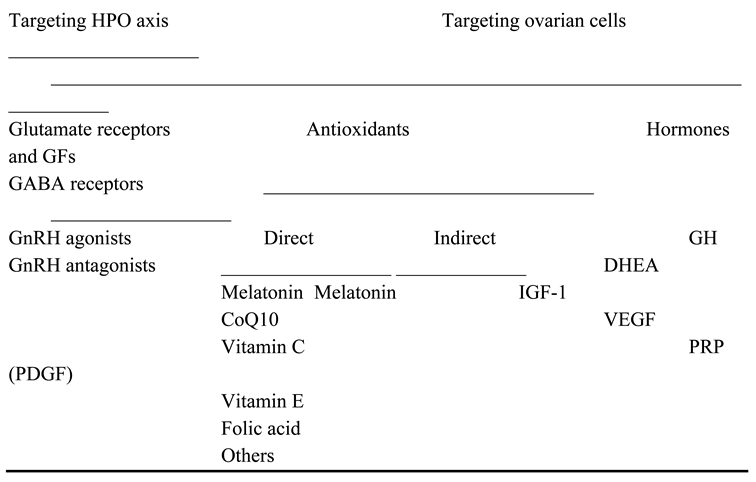

Table 1.

Summary table of the existing strategies to counteract ovarian aging. Abbreviations: HPO: hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis; GFs: growth factors; GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid; GnRH: gonadotropin-releasing hormone; GH: growth hormone, DHEA: dehydroepiandrosterone; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor 1; CoQ10: coenzyme Q10; VEGF: vascular epidermal growth factor; PRP: platelet-rich plasma; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor.

Table 1.

Summary table of the existing strategies to counteract ovarian aging. Abbreviations: HPO: hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis; GFs: growth factors; GABA: gamma-aminobutyric acid; GnRH: gonadotropin-releasing hormone; GH: growth hormone, DHEA: dehydroepiandrosterone; IGF-1: insulin-like growth factor 1; CoQ10: coenzyme Q10; VEGF: vascular epidermal growth factor; PRP: platelet-rich plasma; PDGF: platelet-derived growth factor.

Despite the absence of knowledge of the exact mechanism of the above neuendocrine changes, circumstantial evidence suggests that they may be somehow related with abnormal neurotransmitter secretion in the central neural system and points to glutamate as a potential responsible. In fact, the vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGLUT2), a protein that packages the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate into synaptic vesicles to be released at synapses, has been localized by immunocytochemistry to the GnRH-secreting neurons in the preoptic region of the rat brain [

20,

21]. A decline in glutamate release from the preoptic area in aged female rats correlates with the reduced GnRH secretion, postpones LH surge [

15] and is accompanied by an attenuation of the expression of glutamate receptors in GnRH-secreting neurons [

22].

In addition to glutamate, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and its GABAA receptor also play an important role in the regulation of GnRH neural secretory activity in rats [

23], entering into an intricate interplay with the glutamate receptors [

24].

Both the glutamate- and GABA-driven signalling in GnRH neurons have been considered as potential targets of therapeutic action. In the rat model, researchers succeeded in restoring normal LH surge by combined treatment with a GABA antagonist and a glutamate agonist, suggesting that a normal GnRH neural output can be reached by balancing the effects of excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in the GnRH-secreting neurons [

25].

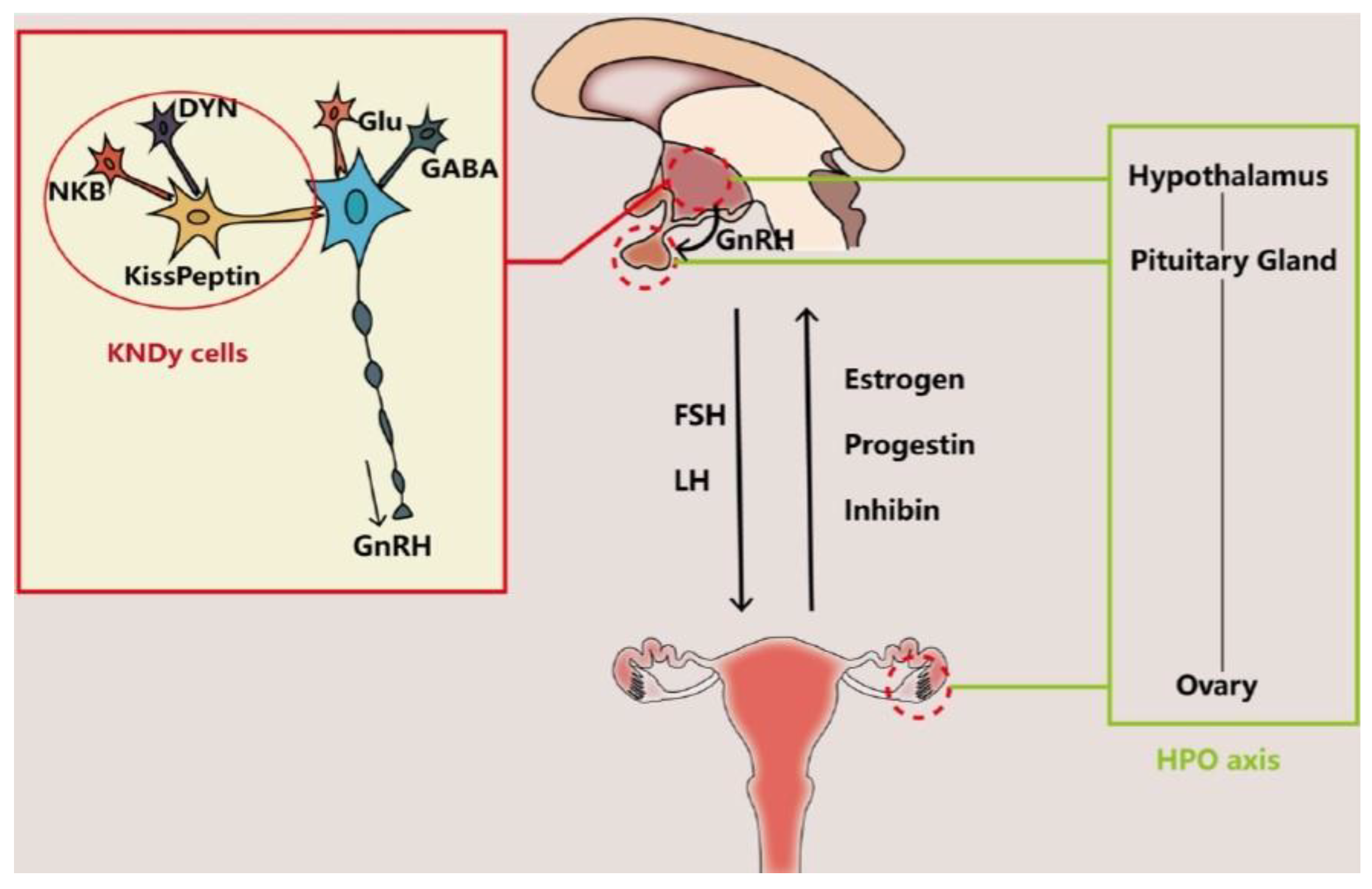

Other neurotransmitters supposed to be involved in controlling the secretory activity of GnRH neurons include the peptides kisspeptin (K) [

26], neurokinin B (N) [

27], and dynorphin (Dy) [

28]. These three peptides colocalize in the so-called KNDy cells, a group of neurons of the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus that co-express K, N and Dy, are conserved across a range of species from rodents to humans, and their interaction is believed to regulate both the hypothalamic GnRH secretion and OA [

28,

29]. There is sufficient evidence indicating that gene expression of these three peptides is altered in postmenopausal women and female monkeys, which is likely to cause an imbalance of excitatory and inhibitory input to GnRH neurons and thus cause neuroendocrine disorder involved in OA [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Whereas the role of the HPO axis (

Figure 1) alterations may be the primary trigger of OA, it is also possible that it is a mere consequence of the decline in follicle numbers, leading to reduced ovarian hormone (mainly estradiol and inhibin) output and thus decreasing the negative feedback on pituitary FSH secretion (

Figure 1) resulting in its elevated serum FSH levels and exacerbating ovarian follicle depletion [

34,

35].

2.2. Targeting the HPO-Independent Ovarian Decay

As compared to the relative scarcity of data on HPO axis, the HPO-independent ovarian decay has received much more attention across the latest decades, resulting in a variety of treatment strategies being clinically available nowadays. The depletion of ovarian follicles, resulting in hypoestrogenism with all its negative health consequences, and the decrease in the quality of the remaining oocytes are the two principal consequences of OA [

2,

6,

12,

35]. However, in order to search for clinically effective prevention and treatment strategies, we have to ask how the different types of cells present in the ovary contribute to this process. The ovary is composed of multiple cell types including oocytes, granulosa cells (GC), theca cells, stromal cells, immune cells and smooth muscle cells. The relative contribution of each of these cell types to the overall picture of OA has been greatly facilitated since 2009, when single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) was first used to analyze the transcriptome of mouse oocytes and embryos [

36]. Since then, scRNA-seq has been increasingly used to analyze individual types of cells in normal and aging ovaries (reviewed in Liang et al. [

37]). By using this approach, a cascade of events, in which immune cell infiltration with stromal cell fibrosis worsens the ovarian microenvironment and GC apoptosis accelerates fertility loss leading to reduced oocyte quality, was mapped and the single-cell transcriptomic level [

38,

39,

40].

It has long been known that oxidative stress, caused by accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), is intimately involved in the process of OA. ROS are by-products of normal cell (mitochondrial) metabolism, required for normal cell function, but their excessive accumulation within cells can have serious negative consequences, namely follicle atresia and diminished oocyte quality [

41]. This situation can result from an age-related decline of ROS scavenging, an enhanced ROS production promoted by different lifestyle and environmental factors (see section 4) or a combination of both. As to the former, it was demonstrated that older women exhibit lower superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels in GC, causing decreased antioxidant efficacy with OA [

41]. In addition to ROS, advanced glycosylation end-products (AGEs), formed by reactive carbonyl species and free amino groups gained from a series of nonenzymatic reactions [

42,

43], also contribute to OA [

35].

As to the oxidative and mitochondrial stress caused by excessive ROS, an accumulation of the effects of negative lifestyle factors (see section 3) is to be blamed for. In order to compensate for this age-related condition, antioxidant and mitochondria-protective treatments, such as vitamins C, D and E, melatonin and others, have been used for decades to slow down ovarian aging [

44]

(see section 3 for the latest updates). Oocytes, as ones of the most long-living cells of the organism, are particularly exposed to oxidative stress. The shortcoming of mitochondrial function due to oxidative stress leads to a damage of the proper mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), further increasing the problem, and subsequently to that of other cell components, mainly those of the microtubules and chromosome cohesive elements, leading to improper chromosome and chromatid separation during the first and the second meiotis division and the resulting oocyte aneuploidy [

45]

.

3. Update on Existing Clinical Strategies Evaluated in Women

From the practical viewpoint, the prevention and treatment of OA has to be directed to a variety of “unhealthy” conditions contributing to this pathology, including lifestyle, diet, environmental factors, and associated pathologies with their specific treatments. It also important to make clear whether the intended strategy is aimed at fertility preservation or limited to the alleviation of the adverse effects of OA on the patient’s general health and well-being. The current clinical strategies are explained below and include antioxidant and mitochondrial therapies (subsection 3.1), the use of GnRH agonists and antagonists (subsection 3.2.), hormones and growth factors (subsection 3.3.), and some more invasive treatments (subsection 3.4.).

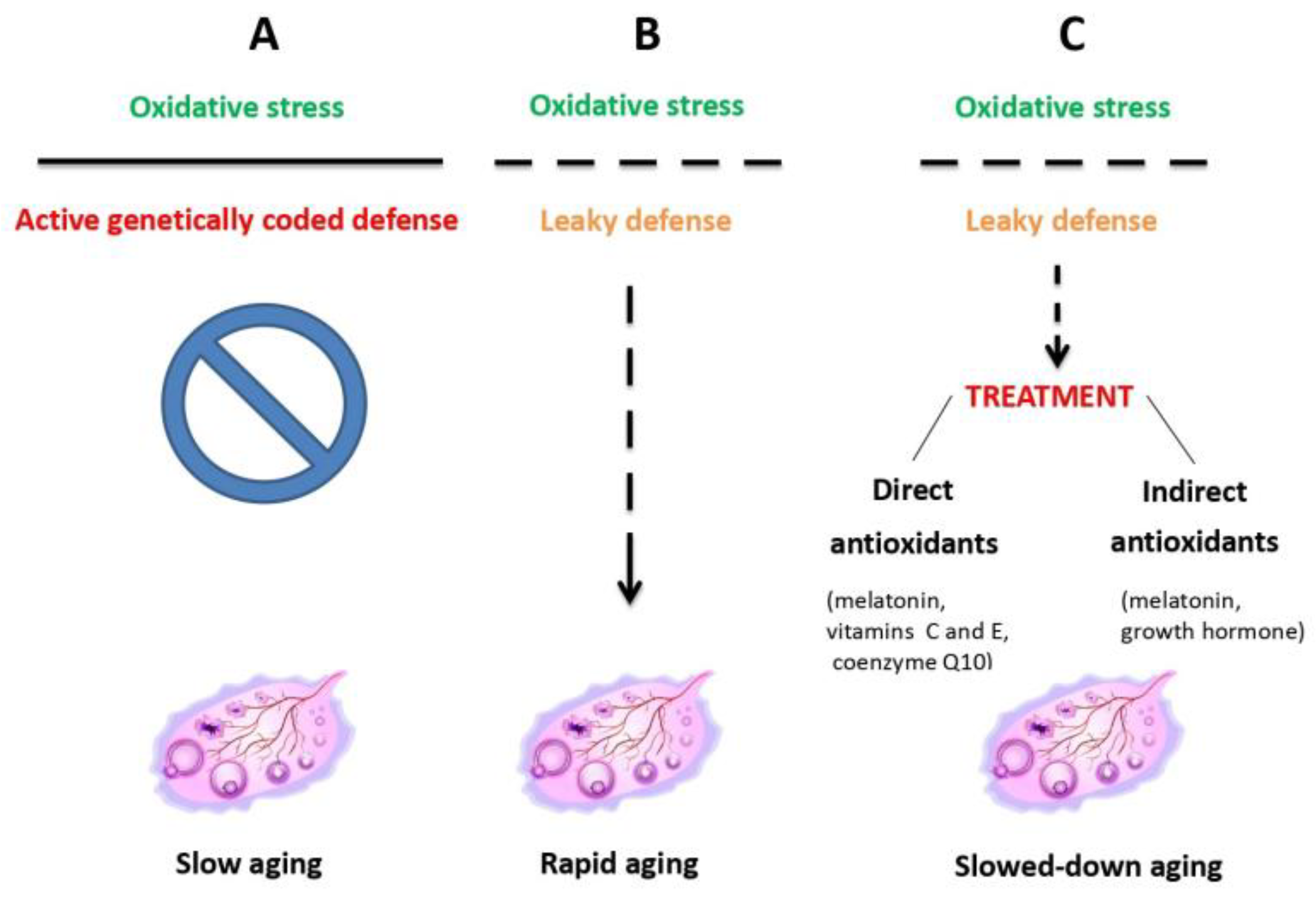

3.1. Antioxidant and Mitochondrial Therapies

In general, antioxidant and mitochondrial therapies (

Figure 2), aimed to slow down OA, have proved to be both the most effective and best tolerated ones [

46]. They were shown to reduce oxidative stress caused by lifestyle factors, such as smoking, unhealthy diet, drug abuse or high alcohol consumption [

47]

. Among a variety of antioxidants available [

35,

44,

45,

46,

48], a special position is reserved to melatonin. In fact, a synthesis of recent data from both animal experimental and human clinical studies (reviewed in Tesarik and Mendoza Tesarik [

49], teaches us that not only is melatonin a powerful antioxidant, acting both through its action as a hormone and a direct ROS scavenger, but it also assumes additional actions in benefit of ovarian health, namely anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory ones (

Figure 3). In fact, disequilibration between individual elements of the immune system, mainly lymphocytes and macrophages, in addition to being involved in other gynecological pathologies, accelerate OA through a chronic, low-grade inflammatory state. At doses of 4-6 mg per day melatonin is thus advisable both for delaying the onset of OA and for the treatment of women that already suffer from it [

48,

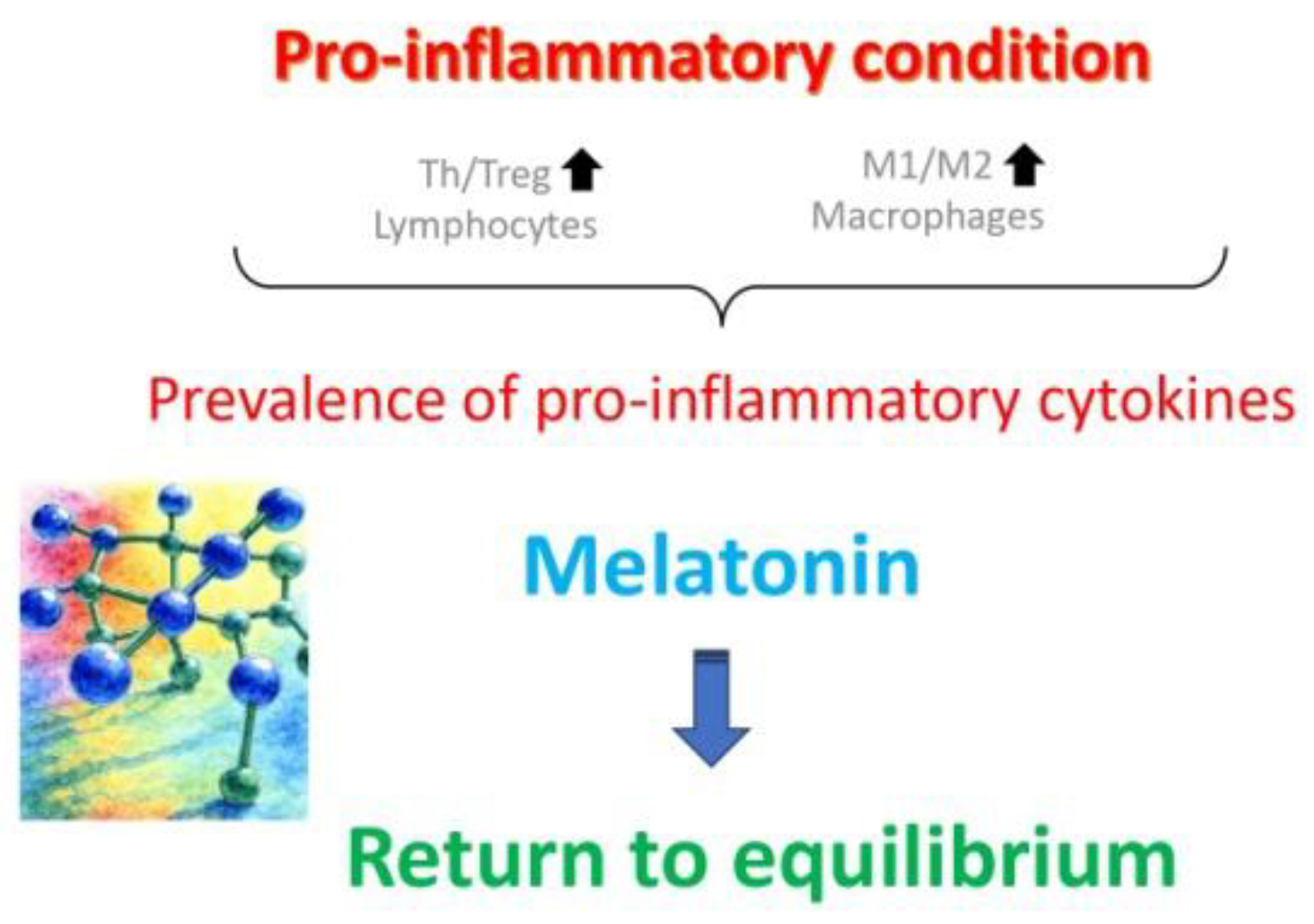

49].

3.2. GnRH Agonists and Antagonists

Other noninvasive recently validated treatment approaches include pharmacological inhibition of follicle recruitment, hormonal and growth factor modulation, and the use of advanced mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants. Briefly, GnRH agonists and antagonists were used to inhibit follicular recruitement during anticancer chemotherapy, aiming at the protection of the ovarian follicular pool against the adverse effects of anticancer drugs. After early encouraging data obtained in male patients [

50] and in an experimental system using female monkeys [

51], this strategy was applied to female cancer patients, too. However, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses suggested that this approach may be controversial and the outcomes may differ among different cancer types and anticancer drugs used [

52,

53,

54,

55]. Further research into this subject, focusing on the individual clinical context, dosage optimization and timing, is warranted.

3.3. Hormones and Growth Factors

Hormonal and growth factor modulation was also reported to give encouraging results in some patients facing OA. In fact, dehydoepiandrosterone (DHEA) supplementation led to improved serum ovarian reserve markers, such as inhibin B and antimullerian hormone (AMH), antral follicle count evaluated by vaginal ultrasound scan, and in vitro fertilization outcomes [

56]. Other recent (2023-2025) small randomized clinical trials have also highlighted the possibilities of using insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to improve antral follicle counts (reviewed in Hirano et al. [

57], and further extensive clinical validation was suggested to develop combination-based therapies (DHEA + IGF-1 + VEGF) by creating personalized formulas adapted to each individual biomarker profile, in terms of modern precision medicine. By the way, as early as in 2005 growth hormone (GH), supposedly acting, at least partially, through IGF-1, was shown to improve IVF outcomes in women aged >40 years when administered during ovarian stimulation [

58], and subsequent studies basically confirmed these findings and suggested the underlying mechanisms of GH action [

59,

60]. New formulations of GH delivery systems, based on novel biomaterials (see setion 4.1.), were shown to improve the bioavailability of GH and may lead to innovative therapeutic strategies for preventing and treating ovarian dysfunction [

61]. Nonetheless, all these treatments still have some limitations. In particular, while the short-term beneficial effects on oocyte quality were demonstrated, further studies are needed to confirm their long-term effects in humans, including the absence of negative consequences for offspring health.

3.4. More Invasive Treatments

In addition to the above non-invasive treatments, other more invasive treatments are also currently in use. Intra-ovarian injection of platelet-rich plasma (PRP), prepared from the patient’s own blood, showed promising results in promoting activation of dormant primordial follicles, believed to be due to an action of platelet-derived growth factors [

62]. Fertility preservation, through either oocyte recovery and freezing or ovarian tissue cryopreservation in view of subsequent autotransplanation, represent other available options [

63]. In addition to be used for restoring fertility, ovarian tissue cryopreservation and autotransplantation may also be considered for endocrine function restoration [

64]. Mitochodrial donation, carried out by pronuclear transfer, has been shown recently to be effective (8 live births out of 22 attempts) in women with pathogenic mtDNA variants [

65]. Other advanced strategies, tested in experimental animal models, are described below (section 4).

4. Outlook

Recently, a number of new therapeutic strategies for OA, though still not ready for clinical application, have emerged. There is a lot of new experimental data, obtained by experimental studies, mainly performed in rodents, that can lead to the development of clinically available solutions for slowing down natural or premature OA in the near future. New developments in OA treatment strategies are based on the knowledge of molecular players governing this process and the understanding of how they can be efficiently targeted by specific therapeutic approaches. Particular attention was paid to biomedicine strategies, such as biomaterials, nanoparticles, extracellular vesicles and “intelligent” advanced drug carriers capable of sensing natural physiological processes so as to achieve controlled drug release for patient-tailored ovarian microenvironment reprogramming, tissue repair, and immune and metabolic regulation (reviewed in Liang et al. [

66]). This section deals with the potential use of new biomaterials (subsection 4.1.), metal-based biomedicines (subsection 4.2.), and natural biomedicines (subsection (4.3.). Perpectives and precautions in view of the future clinical strategies are resumed in subsection 4.4.

4.1. Biomaterials

Research into new biomaterials in regenerative medicine, including those recreating the three-dimensional environment for in-vitro cultured cells, has been aimed at creating a microenvironment favouring cell interactions, promoting good passive and active targeting and allowing for high drug loading capacity and controlled drug release, while still displaying good stability and biodegrability Two types of biomaterials have been investigated in animal models of OA, natural ones and synthetic ones, each one showing its own advantages and disadvantages [

67]. Briefly, natural biomaterials, derived from biological sources like humans, plants, animals, and microorganisms, are valued for being biocompatible and biodegradable and can be categorized based on their composition as protein-based and polysaccharide-based ones.

In the context of OA prevention and therapy, recent research highlights several types of natural biomaterials, including stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles, human amniotic cell-derived, follicular fluid-derived and menstrual blood stromal cell-derived exosomes, decellularized extracellular matrix, collagen, hyaluronic acid, fibrin, and alginate. All of them have been evaluated, and showed promising results in animal models. Likewise, synthetic (polyethyleneglycol, supramolecular hydrogels) were tested in animal models of OA eith promising results (reviewed in Wu et al. [

67]).

4.2. Metal-Based Biomedicines

Nanoparticles (NPs) based on cerium dioxide and silver have attracted widespread attention due to their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory action, likewise silver and magnesium oxide NPS which, in addition, were shown to alleviate hormone imbalances occurring during OA. In turn, zinc oxide NPs not only exhibited antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects but were also shown to be particularly useful in the context of OA associated with diabetes, by enhancing insulin sensitivity and regulating glucose metabolism (reviewed in Wu et al. [

67]).

4.3. Natural Biomedicines

Knowledge derived from ancestral natural medicine formulas has recently been re-evaluated in animal models of OA. As a matter of example, celastrol, a compound extracted from the Chinese plant

Triprerygium wilfordii, was shown to promote ovarian follicle development in mice and pigs by regulating granulosa cell proliferation and apoptosis [

68]. A 2-month treatment of mice with low molecular weight Chitosan, a natural fibrous polysaccharide derived from chitin, led to delayed OA, and this effect was apparently mediated by enhanced macrophage phagocytosis and improved ovarian tissue homeostasis [

69]. Another study has demonstrated that collagen extracted from the sturgeon swim bladder can counteract OA in mice exposed to cyclophosphamide through a variedy of mechanisms, including antioxidant effects, the activation of the PI3K/Akt and Bcl-2/Bax pathways, and the inhibition of the mitogen-ativated protein kinase pathway, thereby reducing apoptosis [

70].

4.4. Perspectives and Precautions

Based on the analysis of the mechanisms causing ovarian cellular senescence, including the accumulation of advanced glycation end products, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, DNA damage, telomere shortening, and exposure to chemotherapy in six distinct cell types (oocytes, granulosa cells, theca cells, immune cells, ovarian surface epithelium, and endothelial cells) led to the suggestion of potential ovarian senotherapeutics for the treatment of OA [

71]. They count with the use of personalized (adapted to the current condition of each individual) mixtures of specific agents, targeting the key factors involved in the senescence of different cell types of the ovary (see above) and include desatinib, quercetin, rapamycin, metformin, resveratrol, melatonin, and coenzyme Q10 [

71]. New vehicles of GH administration, facilitating its bioavalability, are also under investigation (see section 3). Yet it has to be stresses that all these therapies are currently at the pre-clinical stage, and their application in humans will need more studies as to their short- and long-term safety.

The employment of new biomaterials and biomedicines, though showing promising results in animal experiments, awaits further validation before clinical application with regard to the efficacy and safety in humans. Above all, taking into account the basic principal of “first do not harm”, a fundamental ethical principle in medicine, the eventual clinical use of these therapies should pass a thorough review of their potential effects on both the short-term and long-term offspring health.

Last but not least, in view of the current trend towards repeating in vitro fertilization/ovarian stimulation cycles has aroused concern about possible long-term adverse effects on ovarian reserve (the stock of oocytes in the ovaries). This issue was addressed by a recent review [

72]. The data presented suggest that repeated ovarian stimulation can induce changes in the immune response and increase oxidative stress in the ovarian microenvironment, leading to an accelerated loss of ovarian reserve. This risk further stresses the interest in the use of melatonin (see subsection 3.1.) before, during and after ovarian stimulation (see subsection 3.1.).

5. Conclusions

OA is a gradual process whereby several elements of the HPO axis become progressively deteriorated, leading to disturbances in the activity of different types of ovarian cells, dysregulation of the menstrual cycle, decreased oocyte quantity and quality and impaired ovarian endocrine functions. While the oocyte issues compromise fertility, the endocrine ones go far below reproduction, increase propensity to certain chronic diseases and negatively affect the general health status and wellbeing. Physiologically, some processes involved in OA start at ages of 25-30 and accelerate significantly between 35 and 40, ultimately leading to a complete menopause after 50 years of age. However, OA may start prematurely in some women and easily go undetected until the possibilities of preventive and therapeutic interventions get diminished. Therefore, subtle signs of premature OA should be looked for, especially in women with a genetic background that predisposes them to this pathology. If the ovaries still can be expected to contain sufficient healthy cells, fertility and endocrine function preservation, through ovarian tissue cryopreservation for later autotrasplantation, may be envisaged.

Preventive and therapeutic actions against OA include those targeting the HPO axis and those acting directly the ovary. Suppression of ovarian follicular development, either acting at the receptor level in hypothalamic GnRH-secreting neurons or directly by using GnRH agonists and antagonists, was largely successful in animal experiments, and some of these treatments are being currently introduced into clinical practice. Direct action at the ovary has an even longer tradition and is based on the oral intake of melatonin and other antioxidants or makes use of hormones and GFs (GH, DHEA, IGF-1, VEGF). In the outlook, the most recent finding point to the development of precision medicine approaches based on personalized combinations of different agents, adapted to each individual patient’s condition.

Author Contributions

J.T. wrote the first draft, R.M.T. prepared the figures, and both J.T. and R.M.T. revised the final draft and finalized the submission. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no external funding for this article.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Legro, R.S.; Wong, I.L.; Paulson, R.J.; Lobo, R.A.; Sauer, M.V. Recipient’s age does not adversely affect pregnancy outcome after oocyte donation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995, 172, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J. Endocrinology of primary ovarian insufficiency: Diagnostic and therapeutic clues. Endocrines 2025, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbels Bupp, M.R. Sex, the aging immune system, and chronic disease. Cell Immunol. 2015, 294, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmuilowicz, E.D.; Manson, J.E.; Rossouw, J.E.; Howard, B.V.; Margolis, K.L.; Greep, N.C.; Brzyski, R.G.; Stefanick, M.L.; O’Sullivan, M.J.; Wu, C.; Allison, M.; Grobbee, D.E.; Johnson, K.C.; Ockene, J.K.; Rodriguez, B.L.; Sarto, G.E.; Vitolins, M.Z.; Seely, E.W. Vasomotor symptoms and cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women. Menopause 2011, 18, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, K.E.; Katon, J.G.; LeBlanc, E.S.; Woods, N.F.; Bastian, L.A.; Reiber, G.E.; Weitlauf, J.C.; Nelson, K.M.; LaCroix, A.Z. Vasomotor symptom characteristics: are they risk factors for incident diabetes? Menopause 2018, 25, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benayoun, B.A.; Kochersberger, A.; Garrison, J.L. Studying ovarian aging and its health impacts: modern tools and approaches. Genes Dev. 2025, 39(15-16), 975–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Editorial. Recognizing the importance of ovarian aging research. Nat Aging 2022, 2, 1071–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelosi, E.; Forabosco, A.; Schlessinger, D. Genetics of the ovarian reserve. Front Genet. 2015, 6, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Migale, R.; Neumann, M.; Mitter, R.; Rafiee, M.R.; Wood, S.; Olsen, J.; Lovell-Badge, R. FOXL2 interaction with different binding partners regulates the dynamics of ovarian development. Sci Adv. 2024, 10, eadl0788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, S.; Rossetti, R.; Moleri, S.; Munari, E.V.; Frixou, M.; Bonomi, M.; Persani, L. Primary ovarian insufficiency: update on clinical and genetic findings. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1464803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Xiang, W. Mechanisms of ovarian aging in women: a review. J Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochynska, S.; Garcia-Perez, M.A.; Tarin, J.J.; Szeliga, A.; Meczekalski, B.; Cano, A. The final phases of ovarian aging: A tale of diverging functional trajectories. J Clin Med. 2025, 14, 5834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, M.; Onodera, T.; Takasaki, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Ichinose, T.; Nishida, H.; Hiraike, H.; Nagasaka, K. Ovarian aging: Pathophysiology and recent developments in maintaining ovarian reserve. Front Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1619516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.T.; Huang, H.H. Aging of hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian function in the rat. Fertil Steril. 1972, 23, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal-Perry, G.; Nejat, E.; Dicken, C. The neuroendocrine physiology of female reproductive aging: An update. Maturitas 2010, 67, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Goldsmith, L.T.; Weiss, G. Age-related changes in the regulation of luteinizing hormone secretion by estrogen in women. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2002, 227, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed Ebbiary, N.A.; Lenton, E.A.; Cooke, I.D. Hypothalamic-pituitary ageing: progressive increase in FSH and LH concentrations throughout the reproductive life in regularly menstruating women. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 1994, 41, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.R., Jr.; Porter, J.C. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone and thyrotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus of women: effects of age and reproductive status. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984, 58, 488–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenton, E.A.; Sexton, L.; Lee, S.; Cooke, I.D. Progressive changes in LH and FSH and LH: FSH ratio in women throughout reproductive life. Maturitas 1988, 10, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabovszky, E.; Turi, G.F.; Kalló, I.; Liposits, Z. Expression of vesicular glutamate transporter-2 in gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons of the adult male rat. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 4018–4021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W; Sun, Z; Mendenhall, JM; Walker, DM; Riha, PD; Bezner, KS; Gore, AC. Expression of Vesicular Glutamate Transporter 2 (vGluT2) on Large Dense-Core Vesicles within GnRH Neuroterminals of Aging Female Rats. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0129633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Mahesh, V.B.; Zamorano, P.L.; Brann, D.W. Decreased gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurosecretory response to glutamate agonists in middle-aged female rats on proestrus afternoon: a possible role in reproductive aging? Endocrinology 1996, 137, 2334–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.; Shannon, E.M.; Fritschy, J.M.; Ojeda, SR. Several GABAA receptor subunits are expressed in LHRH neurons of juvenile female rats. Brain Res. 1998, 780 780(2), 218–229 218-29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moenter, S.M.; DeFazio, R.A. Endogenous gamma-aminobutyric acid can excite gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 5374–5379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal-Perry, G.S.; Zeevalk, G.D.; Shu; Etgen, A.M. Restoration of the luteinizing hormone surge in middle-aged female rats by altering the balance of GABA and glutamate transmission in the medial preoptic area. Biol Reprod. 2008, 79, 878–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seminara, S.B.; Messager, S.; Chatzidaki, E.E.; Thresher, R.R.; Acierno, J.S., Jr.; Shagoury, J.K.; Bo-Abbas, Y.; Kuohung, W.; Schwinof, K.M.; Hendrick, A.G.; Zahn, D.; Dixon, J.; Kaiser, U.B.; Slaugenhaupt, S.A.; Gusella, J.F.; O’Rahilly, S.; Carlton, M.B.; Crowley, W.F., Jr.; Aparicio, S.A.; Colledge, WH. The GPR54 gene as a regulator of puberty. N Engl J Med. 2003, 349, 1614–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloglu, A.K.; Reimann, F.; Guclu, M.; Yalin, A.S.; Kotan, L.D.; Porter, K.M.; Serin, A.; Mungan, N.O.; Cook, J.R.; Imamoglu, S.; Akalin, N.S.; Yuksel, B.; O’Rahilly, S.; Semple, R..K. TAC3 and TACR3 mutations in familial hypogonadotropic hypogonadism reveal a key role for Neurokinin B in the central control of reproduction. Nat Genet. 2009, 41, 354–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, M.N.; Coolen, L.M.; Goodman, R.L. Minireview: kisspeptin/neurokinin B/dynorphin (KNDy) cells of the arcuate nucleus: a central node in the control of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 3479–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbison, A.E. The gonadotropin-releasing hormone pulse generator. Endocrinology 2018, 159, 3723–3736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rance, N.E.; Young, W.S., 3rd. Hypertrophy and increased gene expression of neurons containing neurokinin-B and substance-P messenger ribonucleic acids in the hypothalami of postmenopausal women. Endocrinology 1991, 128, 2239–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rometo, A.M.; Krajewski, S.J.; Voytko, M.L.; Rance, N.E. Hypertrophy and increased kisspeptin gene expression in the hypothalamic infundibular nucleus of postmenopausal women and ovariectomized monkeys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007, 92, 2744–2750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rometo, A.M.; Rance, N.E. Changes in prodynorphin gene expression and neuronal morphology in the hypothalamus of postmenopausal women. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008, 20, 1376–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eghlidi, D.H.; Haley, G.E.; Noriega, N.C.; Kohama, S.G.; Urbanski, H.F. Influence of age and 17beta-estradiol on kisspeptin, neurokinin B, and prodynorphin gene expression in the arcuate-median eminence of female rhesus macaques. Endocrinology 2010, 151, 3783–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, W.H.; Kelsey, T.W. Human ovarian reserve from conception to the menopause. PLoS One 2010, 5, e8772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Xiang, W. Mechanisms of ovarian aging in women: a review. J Ovarian Res. 2023, 16, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, F.; Barbacioru, C.; Wang, Y.; Nordman, E.; Lee, C.; Xu, N.; Wang, X.; Bodeau, J.; Tuch, B.B.; Siddiqui, A.; Lao, K.; Surani, M.A. mRNA-Seq whole-transcriptome analysis of a single cell. Nat Methods 2009, 6, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Gai, S.; Na, X.; Hu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zi, D.; Na, Z.; Gao, W.; Bi, F.; Li, D. Ovarian aging at single-cell resolution: Current paradigms and perspectives. Ageing Res Rev. 2025, 110, 102807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Song, M.; Liu, Z.; Min, Z.; Hu, H.; Jing, Y.; He, X.; Sun, L.; Ma, L.; Esteban, C.R.; Chan, P.; Qiao, J.; Zhou, Q.; Izpisua Belmonte, J.C.; Qu, J.; Tang, F.; Liu, G.H. Single-cell transcriptomic atlas of primate ovarian aging. Cell. 2020, 180, 585–600.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isola, J.V.V.; Ocañas, S.R.; Hubbart, C.R.; Ko, S.; Mondal, S.A.; Hense, J.D.; Carter, H.N.C.; Schneider, A.; Kovats, S.; Alberola-Ila, J.; Freeman, W.M.; Stout, M.B. A single-cell atlas of the aging mouse ovary. Nat Aging 2024, 4, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rooda, I.; Méar, L.; Hassan, J.; Damdimopoulou, P. The adult ovary at single cell resolution: an expert review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2025, 232, S95.e1–S95.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, M.; Onodera, T.; Takasaki, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Ichinose, T.; Nishida, H.; Hiraike, H.; Nagasaka, K. Ovarian aging: pathophysiology and recent developments in maintaining ovarian reserve. Front Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1619516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucala, R.; Cerami, A. Advanced glycosylation: chemistry, biology, and implications for diabetes and aging. Adv Pharmacol. 1992, 23, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papachroni, K.K.; Piperi, C.; Levidou, G.; Korkolopoulou, P.; Pawelczyk, L.; Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Papavassiliou, A.G. Lysyl oxidase interacts with AGE signalling to modulate collagen synthesis in polycystic ovarian tissue. J Cell Mol Med. 2010, 14, 2460–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Varela, C.; Labarta, E. Clinical application of antioxidants to improve human oocyte mitochondrial function: a review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Tang, J.; Wang, L.; Tan, F.; Song, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, F. Oxidative stress in oocyte aging and female reproduction. J Cell Physiol. 2021, 236, 7966–7983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Galán-Lázaro, M.; Mendoza-Tesarik, R. Ovarian aging: Molecular mechanisms and medical management. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, C.; Wyse, B.A.; Fuchs Weizman, N.; Kuznyetsova, I.; Madjunkova, S.; Librach, C.L. Cannabis impacts female fertility as evidenced by an in vitro investigation and a case-control study. Nat Commun. 2025, 16, 8185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesarik, J. Towards personalized antioxidant use in female infertility: Need for more molecular and clinical studies. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Mendoza Tesarik, R. Melatonin in the treatment of female infertility: Update on biological and clinical findings. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glode, L.M.; Robinson, J.; Gould, S.F. Protection from cyclophosphamide-induced testicular damage with an analogue of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Lancet 1981, 1, 1132–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataya, K.; Rao, L.V.; Lawrence, E.; Kimmel, R. Luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonist inhibits cyclophosphamide-induced ovarian follicular depletion in rhesus monkeys. Biol Reprod. 1995, 52, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgindy, E.; Sibai, H.; Abdelghani, A.; Mostafa, M. Protecting ovaries during chemotherapy through gonad suppression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2015, 126, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambertini, M.; Horicks, F.; Del Mastro, L.; Partridge, A.H.; Demeestere, I. Ovarian protection with gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists during chemotherapy in cancer patients: From biological evidence to clinical application. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019, 72, 65–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumenfeld, Z. Fertility preservation using GnRH agonists: Rationale, possible mechanisms, and explanation of controversy. Clin Med Insights Reprod Health 2019, 13, 1179558119870163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Xue, L.; Tang, W.; Xiong, J.; Chen, D.; Dai, Y.; Wu, C.; Wei, S.; Dai, J.; Wu, M.; Wang, S. Ovarian microenvironment: challenges and opportunities in protecting against chemotherapy-associated ovarian damage. Hum Reprod Update 2024, 30, 614–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, N.; Uygur, D.; Inal, H.; Gorkem, U.; Cicek, N.; Mollamahmutoglu, L. Dehydroepiandrosterone supplementation improves predictive markers for diminished ovarian reserve: serum AMH, inhibin B and antral follicle count. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013, 169, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirano, M.; Onodera, T.; Takasaki, K.; Takahashi, Y.; Ichinose, T.; Nishida, H.; Hiraike, H.; Nagasaka, K. Ovarian aging: pathophysiology and recent developments in maintaining ovarian reserve. Front. Endocrinol. 2025, 16, 1619516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesarik, J.; Hazout, A.; Mendoza, C. Improvement of delivery and live birth rates after ICSI in women aged >40 years by ovarian co-stimulation with growth hormone. Hum Reprod. 2005, 20, 2536–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Yovich, J.L.; Menezo, Y. Editorial: Growth hormone in fertility and infertility: Physiology, pathology, diagnosis and treatment. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 621722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tesarik, J. Editorial: Growth hormone in fertility and infertility: Physiology, pathology, diagnosis and treatment, volume II. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2024, 15, 1446734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Luo, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, S. Novel perspectives on growth hormone regulation of ovarian function: mechanisms, formulations, and therapeutic applications. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2025, 16, 1576333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghpour, S.; Maleki, F.; Hajizadeh-Sharafabad, F.; Ghasemnejad-Berenji, H. Evaluation of intraovarian injection of platelet-rich plasma for enhanced ovarian function and reproductive success in women with POI and POR: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Med Res. 2025, 30, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimizadeh, Z.; Saltanatpour, Z.; Tarafdari, A.; Rezaeinejad, M.; Hamidieh, A.A. Ovarian tissue cryopreservation: a narrative review on cryopreservation and transplantation techniques, and the clinical outcomes. Ther Adv Reprod Health 2025, 19, 26334941251340517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khattak, H.; Malhas, R.; Craciunas, L.; Afifi, Y.; Amorim, C.A.; Fishel, S.; Silber, S.; Gook, D.; Demeestere, I.; Bystrova, O.; Lisyanskaya, A.; Manikhas, G.; Lotz, L.; Dittrich, R.; Colmorn, L.B.; Macklon, K.T.; Hjorth, I.M.D.; Kristensen, S.G.; Gallos, I.; Coomarasamy, A. Fresh and cryopreserved ovarian tissue transplantation for preserving reproductive and endocrine function: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2022, 28, 400-416. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmac003. Erratum in: Hum Reprod Update. 2022, 28, 455. https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmac015.

- McFarland, R.; Hyslop, L.A.; Feeney, C.; Pillai, R.N.; Blakely, E.L.; Moody, E.; Prior, M.; Devlin, A.; Taylor, R.W.; Herbert, M.; Choudhary, M.; Stewart, J.A.; Turnbull, DM. Mitochondrial donation in a reproductive care pathway for mtDNA disease. N Engl J Med. 2025, 393, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, D.; Liang, H.; Yao, Y.; Xia, X.; Yu, H.; Jiang, M.; Yang, Y.; Gao, M.; Liao, L.; Fan, J. The cutting-edge progress of novel biomedicines in ovulatory dysfunction therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B 2025, 15, 5145–5166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, M.; Guo, Y.; Wei, S.; Xue, L.; Tang, W.; Chen, D.; Xiong, J.; Huang, Y.; Fu, F.; Wu, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Li, Y.; Wang, W.; Dai, J.; Wang, S. Biomaterials and advanced technologies for the evaluation and treatment of ovarian aging. J Nanobiotechnology 2022, 20, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Lv, M.; Wang, T.; Wang, P.; Yuan, X.; Gao, F.; Ma, B. Celastrol modulates IRS1 expression to alleviate ovarian aging and to enhance follicular development. Cell Biol Toxicol. 2025, 41, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Liu, N.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Wu, H.H.; Xie, F.; Wang, W.J.; Li, M.Q. Chitosan alleviates ovarian aging by enhancing macrophage phagocyte-mediated tissue homeostasis. Immun Ageing 2024, 21, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, T.; Hu, J.; Zhang, W.; Shen, M.; Yu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Xie, J. Collagen (peptide) extracted from sturgeon swim bladder: Physicochemical characterization and protective effects on cyclophosphamide-induced premature ovarian failure in mice. Food Chem. 2025, 466, 142217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wang, K.; Feng, Y.; Tsui, K.H.; Singh, K.K.; Stout, M.B.; Wang, S.; Wu, M. Exploration of the mechanism and therapy of ovarian aging by targeting cellular senescence. Life Med. 2025, 4, lnaf004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, O.G.M.; Santos, S.A.A.R.; Damasceno, M.B.M.V.; Joventino, L.B.; Schneider, A.; Masternak, M.M.; Campos, A.R.; Cavalcante, M.B. Impact of repeated ovarian hyperstimulation on the reproductive function. J Reprod Immunol. 2024, 164, 104277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).