1. Introduction

Plastic pollution has become a major environmental problem. To date, particulate plastics (often referred to as micro- or nanoplastics) has been the central research topic of plastic pollution and only recently concerns over plastic additives have also been expressed [

1,

2]. Plastic is a chemically diverse material, a blend of polymer(s) and additives, which total number mounts up to 16 000 [

3]. Additives have the potential to migrate from the plastic matrix [

4] and play a significant role in toxicity of plastics [

5,

6,

7]. Not only additives but also the breakdown products such as nanoparticles and oligomers may also play a role in toxicity of a plastic material [

8]. However, compared to microplastics, the risks related to leaching of additives from plastic materials and their consecutive uptake via water by biota are poorly studied [

9,

10,

11] primarily addressing potential hazard to human health [

12]. Significant knowledge gaps and challenges complicate environmental hazard assessment of plastic materials [

13] as most of the available ecotoxicological data on plastic additives regard pure chemicals. At the same time, consumer products contain multitude of undisclosed additives [

14]. Even if the information on additives was available, knowledge on chemical composition of plastics alone would not be sufficient for predicting the environmental hazard of plastic goods [

15] due to limited knowledge on their mixture effects and bioavailability in the leachates [

5,

9,

16]. Biological effects of plastics additives depend on their ability to migrate from plastic, persist in the environment and interact with other compounds and contaminants. Therefore, currently only experimental toxicity data can be relevant basis for environmental hazard prediction of plastics. Foamed plastics have wide applicability from (food) packaging to construction but at the end of life are mostly landfilled. Foamed plastics are lightweight, easily transported in the environment, and have been shown to constitute about 12% of beached plastic litter [

17].

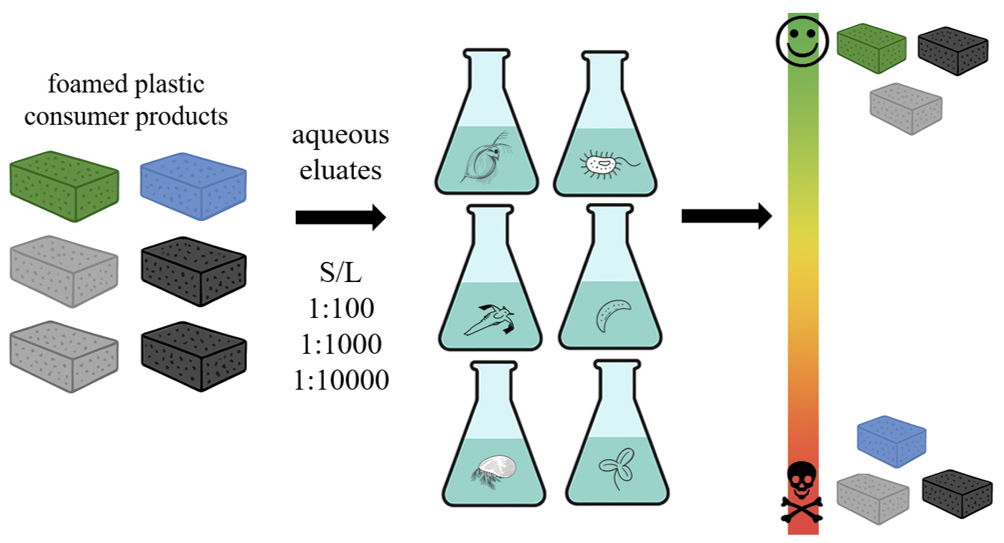

The aim of the current study was to i) evaluate the potential hazard of randomly selected foamed plastic consumer goods to aquatic biota and ii) propose a sensitive battery of aquatic bioassays for ecotoxicity screening of eluates of foamed plastic. In the study, no specific plastic additive (group) was targeted as the eluates typically contain a mixture of chemicals with different toxic potential.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Foamed Plastic Consumer Goods

In the current study, aquatic toxicity of six foamed plastic consumer products (

Table 1) was studied. Five randomly selected consumer products were purchased from local retailers and one material originated from laboratory consumable packaging. We focused on homogenous foams (

Figure S1) in order to minimize potential additional mixture effects due to e.g. adhesives and paints on the surface of product. All the tested items are commonly used, not recyclable and therefore end up in general mixed waste. Brand names are undisclosed, instead we provide general description of the product application. Among the tested materials, there were both ‘open cells’ and ‘closed cell’ polymeric foams (

Table 1)

2.2. Preparation of Eluates

Before the leaching procedure, foams were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water, dried at room temperature and cut into ~0.5 x 0.5 cm pieces. Leaching was performed according European standard EN 14735:2005 [

18] except the recommended solid-to-liquid ratio (S/L) 1:10 was not applicable because of the very high volume/weight ratio (

Figure S3) of the foams. Three eluates (solutions recovered from leaching procedures) of S/L 1:100, 1:1000 and 1:10000 were prepared just before conducting the toxicity testing. The eluates were prepared in the same test media (leachant) that was used for the toxicity assays. Upon 24 h shaking at 22 C°, the eluates were passed 0.4 mm filter before toxicity evaluation. In all the eluates, pH was within the valid range (6.6 - 8.5) for toxicity exposure. The conductivity of the eluates was marginally higher (less than 10%) than that of the test media used as the leachant.

2.3. Ecotoxicity Evaluation

Eight different exposure settings (

Table 2) using 6 aquatic species from different food-web level: marine bacteria

Vibrio fischeri, duckweed

Lemna minor, microalgae

Raphidocelis subcapitata, freshwater microcrustaceans pelagic

Daphnia magna (water flea) and

Thamnocephalus platyurus (fairy shrimp) and benthic

Heterocypris incongruens were chosen for this study. All the tests were performed two-three times in several (n >2) technical parallels.

In the 30-min bioluminescence inhibition assay with bacteria

V. fischeri, the bacteria were suspended and the samples were tested in 2% NaCl solution. Reconstituted

V. fischeri reagent (Aboatox, Turku, Finland) was used and bacterial bioluminescence measured by automated tube-luminometer 1251 (ThermoLabsystems, Finland), operated by Multiuse software (BioOrbit, Finland) according to modified Flash-assay protocol [

19]. Inhibition of bacterial bioluminescence was calculated as a percentage of the unaffected control (2% NaCl). The 72 h algae

P. subcapitata growth inhibition test was performed according to OECD 201 [

20]. Algae were grown in the OECD medium and their biomass was determined using chlorophyll fluorescence. Growth inhibition was calculated as the ratio of the sample's biomass to the biomass of the negative control. The 7-day growth inhibition assay with duckweed

L. minor was performed in artificial freshwater by OECD 221 [

21]. Dry biomass of the plants was measured at the end of exposure. Inhibition of the growth rate was calculated as follows:

where:

- INH%: inhibition (%) of specific growth rate

- Mc: mean value in the control group

- Mt: mean value in the treatment group

For microcrustacean (

T. platyurus, H. incongruens,

D. magna) assays, dormant eggs (MicroBioTests Inc., Belgium) were used to hatch the test organisms. Two types of artificial freshwater (moderately hard synthetic freshwater [

22] for

H. incongruens and

T. platyurus; ISO medium [

23] for

D. magna) and natural freshwater were used as the media for leaching and toxicity exposures. Natural water (

Table S1) was collected from Lake Ülemiste (used for Tallinn water supply), passed 0.45 µm cellulose nitrate filter (Sartorius) and stored at 4 C° in the dark. In

T. platyurus assay [

24], organisms were exposed as <24 h larvae and mortality was assessed upon 24 h exposure. In

H. incongruens assay [

25], organisms were exposed as <4 h larvae and growth inhibition (relative to control) and mortality were assessed upon 6-day exposure. Acute 48 h

D. magna assay was performed according OECD 202 but in addition, prolonged 96 h exposure was applied. In the 96 h format, after 48 h exposure, organisms were fed once with

P. subcapitata at 0.1 mg C/

Daphnia/day. The long-term impact of eluates on

D. magna survival and reproduction was evaluated in 21-day exposure [

26], conducted in natural freshwater.

2.4. Data Analysis

All the toxicity (EC

50) values (confidence interval CI 95%) were calculated from dose-response curves generated with the log-normal distribution model of the REGTOX software EV7.1.2 for Microsoft Excel™ [

27]. To determine statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) between the EC

50 values, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Tukey post-hoc test was performed in Microsoft Excel v2010.

3. Results and Discussion

Potential hazard of eluates of foamed plastic goods was evaluated using organisms from different trophic levels: producers/autotrophs (duckweed

L. minor and microalgae

R. s

ubcapitata), heterotrophs (freshwater microcrustaceans

T. platyurus, D. magna and

H. incongruens) and decomposers bacteria

V. fischeri. In real-life conditions, differently sized plastic particles enter aquatic ecosystems along with additives, leached from plastic goods [

28], and their mixture effects pose a potential hazard to the biota [

29]. To enhance environmental relevance of hazard evaluation but account for the small size of particle-ingesting test organisms, only larger (> 0.4 mm) fractions were removed from the eluates, i.e. mixture effects of the leached plastic additives and particles (

Figure S4) were evaluated in the study. From the filtrate of KP-3 eluate (

Figure S4) it was evident that heterogenous particulate matter (potentially originating also from fillers) was present in the eluate. Both artificial and natural freshwater may be used in aquatic crustacean assays [

23,

25,

26]. Here, the same medium was used both for eluate preparation as well as for toxicity exposures. It is a common knowledge that chemical composition of the leachant may affect not only the leaching process but also bioavailability of the compounds. In our previous studies, modulating effects of natural freshwater, compared to AFW on the toxicity of both inorganic [

30,

31] and organic [

32] compounds were demonstrated by the same acute bioassays as in the current study. Though here, for the eluates (S/L 1:100, 1:1000, 1:10000), no statistical difference between acute toxicity results from artificial vs natural freshwater exposures was detected neither for

D. magna nor

H. incongruens. Luo et al. [

33] has demonstrated similar plastics leachate profiles in lake water and in tap water. Thus, for higher environmental relevance, the 21-day bioassays with

D. magna (

Table 2) were performed only in natural freshwater.

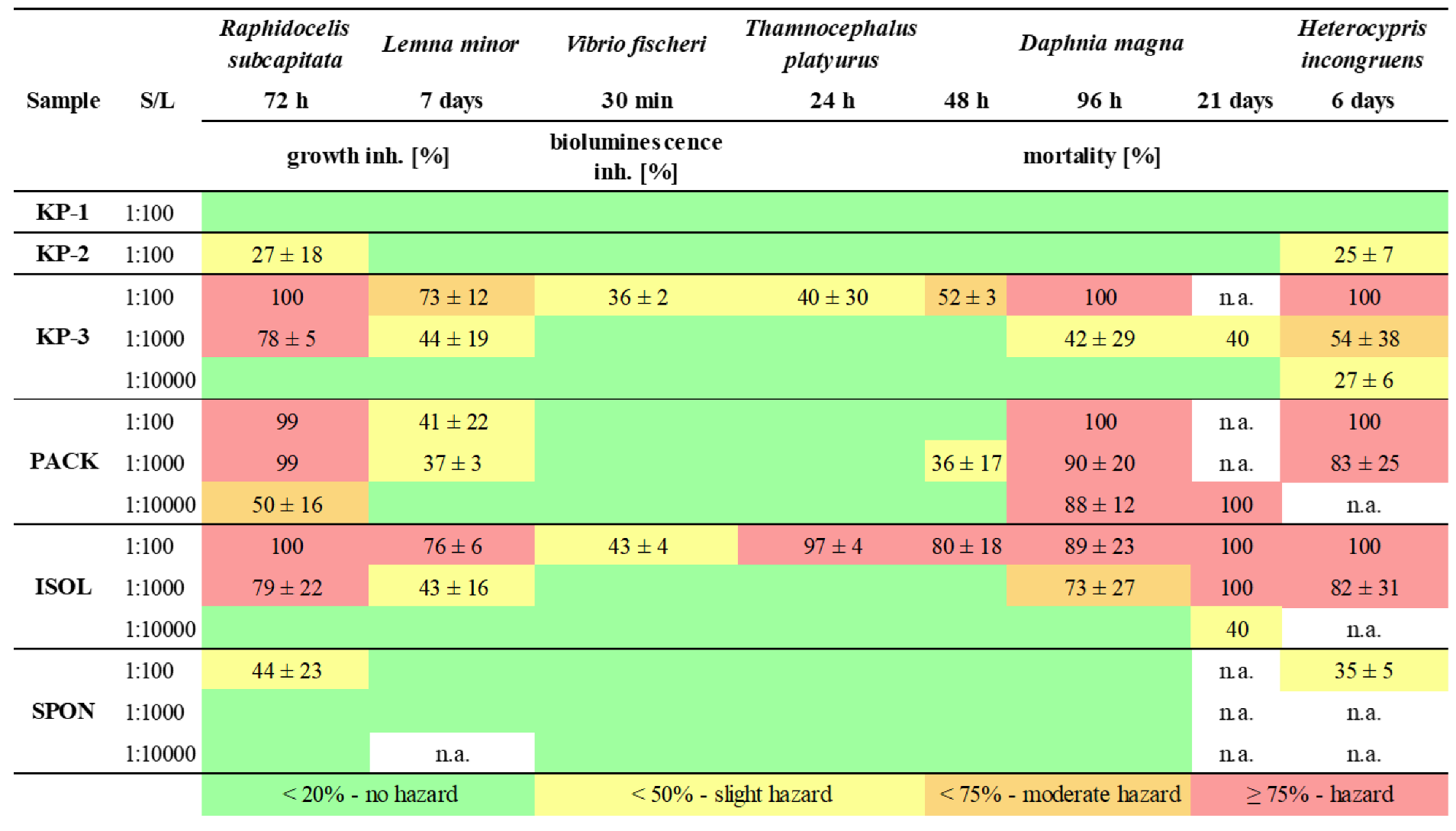

3.1. Toxicity of Eluates to Aquatic Biota

Results of the toxicity evaluation showed that eluates of all the foamed plastic products affected aquatic species but their toxicity potential differed (

Table 3). The most concentrated eluates (S/L 1:100) of the two kneeling pads (KP-1 and KP-2) and dish sponge (SPON) showed slight toxicity to some test species. Eluates of kneeling pad KP-3, packaging foam (PACK) and isolation foam (ISOL) showed high hazard to the aquatic ecosystem. The most toxic eluate was of packaging foam (PACK) which showed (very) high toxicity even at S/L 1:10000. The kneeling pad (KP-3) and isolation foam (ISOL) were also inducing high hazard to some test species (microalga

P. subcapitata, microcrustaceans

D. magna and

H. incongruens) in S/L 1:1000 eluates.

Sensitivity to eluate toxicity depended on test species as well as exposure durations. Acute exposures with marine bacteria

V. fischeri (30 min), pelagic microcrustaceans

T. platyurus (24 h) and

D. magna (48 h) showed the lowest sensitivity (

Table 3). Varying acute exposure durations in

D. magna immobilization assay influenced the results significantly: upon standard 48 h [

23] many non-hazardous eluates induced high hazard upon 96 h exposure (

Table 3). Our results agreed with literature where toxicity of plastic eluates [

34] and nanomaterials [

35] for

D. magna was recorded only upon extended exposure (from 48 h to 96 h). It is important to note that in the current study, the exposed daphnids were fed after 48 h to minimise likelihood of increased sensitivity due to starvation. Our results showed that standard 48 h exposure may lead to underestimation of the risks associated with plastics in aquatic ecosystems.

The 6-day bioassay with ostracod

H. incongruens was more sensitive than the acute tests. Since H. incongruens is a benthic microcrustacean, comparable sensitivity to 96-h

D. magna assay may be explained by enhanced contact with settled fractions. However, accumulation of (micro)particles (

Figure S4) in the gut was visible in all the crustacean assays (

Figure S5). Across the assays, the 6-day H. incongruens and the 96-h D. magna assays were the most sensitive ones along with the 72 h microalga R. subcapitata assay. The microalgal growth inhibition was in very good correlation (R

2 = 0.76) with 7-day L. minor growth inhibition but was more sensitive (

Table 3) and resource-effective (

Table 2). Importantly, the three most sensitive assays yielded comparable results to those of the 21-day chronic D. magna assay [

26] that gives the most relevant data for environmental safety evaluation of plastics but is too resource-consuming to be used in the screening phase.

3.2. Uncertainties in the Environmental Hazard Assessment of Plastics Eluates

Currently, a variety of leaching procedures are used to prepare plastics eluates making it difficult to compare toxicity data across publications. The most crucial parameter is solid-to-liquid ratio (S/L) used in the leaching process. Generally, the toxicity of eluates is assessed by exposing the test organism to a dilution series of the initial eluate prepared at a single S/L ratio and toxicity (e.g., EC

50) values are expressed as a percentage of the undiluted initial eluate. At the same time, different S/L ratios 1:2 – 1:100 [

9,

36,

37,

38,

39] are used for preparation of the initial eluate. Although, higher S/L ratio has been proposed a reliable proxy for eluate aqueous toxicity [

40] however higher S/L ratio eluates may induce lower toxicity than lower ratio eluates due to saturation of leached compounds [

32,

41]. This was also shown in the current study for the most toxic samples (e.g. PACK) in case of which 10-fold dilutions of the eluate induced comparable toxicity (

Table 3). Leaching duration [

42], the leachant as well as the plastic particle size all affect potential toxicity of plastic eluates [

40]. In some cases, leachant is other than the medium used in toxicity exposures [

43].

From our perspective, applying S/L ratio of ≤1:100 and use of leachants other than the exposure medium for eluate preparation is not in line with the aims of relevant environmental risk assessment. Filtration (e.g. 0.45 µm) of the eluate prior to toxicity evaluation significantly increases both the duration and cost of the evaluation, especially for e.g. long-term toxicity tests that require large volumes of eluate.

4. Conclusions

This toxicity screening study raised concerns about environmental safety of commercially available plastic products intended for widespread consumer use. If frequently used products such as kneeling pads pose high hazard to aquatic biota, risks to human health cannot be excluded. By using aqueous eluates of foamed plastics, it was demonstrated that acute toxicity assays—such as the 30 min assay with

Vibrio fischeri [

19], the 24 h assay with

Thamnocephalus platyurus [

24], and the 48 h assay with

Daphnia magna [

23] may underestimate environmental hazards induced by these materials. However, extending the duration of

D. magna assay from 48 h to 96 h increased its sensitivity significantly. Across the ecotoxicity evaluation panel of six aquatic species and eight exposure settings, we recommend the 72 h

Raphidocelis subcapitata assay, the 96 h

D. magna assay and the 6-day

Heterocypris incongruens assay for screening the environmental safety of foamed plastics eluates. The study highlights the need for stronger regulation of additives in plastics and environmental hazard assessment of this complex material by harmonizing/standardizing methods for leachate preparation and ecotoxicity testing.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: Surface of the analysed foamed plastic materials., Figure S2: ATR-FTIR (PerkinElmer Spectrum Spotlight 400) spectra of the foamed plastics, analysed in SpectrumIMAGE software., Figure S3: Volume of the foamed plastic materials (kneeling pads) (green is KP-1 and black is KP-2) used for preparing eluate of SLR 1:100 (10 g per 1 L)., Figure S4: Filtrate of the eluate of the blue kneeling pad (KP-3)., Figure S5: Accumulation of the plastic particles in Daphnia magna upon 21-day exposure to KP-3 (blue kneeling pad) eluate (S/L 1:1000)., Table S1: The main physico-chemical parameters of natural freshwater from Lake Ülemiste (Tallinn, Estonia) used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.B. M.H.; Methodology, I.B, V.A.; Formal Analysis, I.B., V.A.; Investigation, I.B., A.L., V.A.; Data Curation, I.B., V.A.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, I.B., M.H.; Writing – Review & Editing, I.B., A.L., A.K., V.A., M.H.; Visualization, I.B., A.L.; Project Administration, A.K., M.H.; Funding Acquisition, A.K., M.H.

Funding

This research was funded by Estonian Research Council grants number PRG1427 and PRG2595 and project NAMUR+ core facility (TT13).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Imbi Kurvet is acknowledged for conducting Vibrio fischeri toxicity assays and Elise Triipan is acknowledged for analyses of microplastics in the filtrates of the eluates. During preparation of this manuscript, the authors used OpenAI application ChatGPT-5.1 and Microsoft 365 Copilot 2025 for creating (upon description) elements for graphical abstract. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- United Nations Environment Programme and Secretariat of the Basel, Rotterdam and Stockholm Conventions. Chemicals in plastics: A technical report. 2023.

- Brander, S.M.; Senathirajah, K.; Fernandez, M.O.; Weis, J.S.; Kumar, E.; Jahnke, A.; Hartmann, N.B.; Alava, J.J.; Farrelly, T.; Almroth, B.C.; Groh, K.J.; Syberg, K.; Buerkert, J.S.; Abeynayaka, A.; Booth, A.M.; Cousin, X.; Herzke, D.; Monclús, L.; Morales-Caselles, C.; Bonisoli-Alquati, A.; Al-jaibachi, R.; Wagner, M. The time for ambitious action is now: Science-based recommendations for plastic chemicals to inform an effective global plastic treaty. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 949, 174881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, M.; Monclús, L.; Arp, H.P.H.; Groh, K.J.; Løseth, M.E.; Muncke, J.; Wang, Z.; Wolf, R.; Zimmermann, L. State of the science on plastic chemicals - Identifying and addressing chemicals and polymers of concern. Zenodo 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Dehaut, A.; Paul-Pont, I.; Lacroix, C.; Jezequel, R.; Soudant, P.; Duflos, G. Occurrence and effects of plastic additives on marine environments and organisms: a review. Chemosphere 2017, 182, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, L.; Göttlich, S.; Oehlmann, J.; Wagner, M.; Völker, C. What are the drivers of microplastic toxicity? Comparing the toxicity of plastic chemicals and particles to Daphnia magna. Environ Pollut. 2020, 267, 115392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beiras, R.; Verdejo, E.; Campoy-Lopez, P.; Vidal-Linan, L. Aquatic toxicity of chemically defined microplastics can be explained by functional additives. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 406, 124338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermabessiere, L.; Best, C.; Zaidi, S.; McIlwraith, H.K.; Jeffries, K.M.; Rochman, C.M. Understanding the contribution of plastic additive in microplastic toxicity from consumer products using fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2025, 32, 14258–14271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, B.D.; Medvedev, A.V.; Makarov, S.S.; Nelson, R.K.; Reddy, C.M.; Hahn, M.E. Moldable plastics (polycaprolactone) can be acutely toxic to developing zebrafish and activate nuclear receptors in mammalian cells. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 5237–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolupo, M.; Sørensen, L.; Jayasena, K.D.R.; Booth, A.M.; Fabbri, E. Chemical composition and ecotoxicity of plastic and car tire rubber leachates to aquatic organisms. Water Res. 2020, 169, 115270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesinger, H.; Wang, Z.; Hellweg, S. Deep dive into plastic monomers, additives, and processing aids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 9339–9351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iftikhar, A.; Qaiser, Z.; Sarfraz, W.; Ejaz, U.; Aqeel, M.; Rizvi, Z.F.; Khalid, N. Understanding the leaching of plastic additives and subsequent risks to ecosystems. Water Emerg. Contam. Nanoplastics 2024, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Liu, Y.; Lyu, H.; He, Y.; Sun, H.; Tang, J.; Xing, B. Plastic takeaway food containers may cause human intestinal damage in routine life usage: Microplastics formation and cytotoxic effect. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 475, 134866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrick, A.; Champeau, O.; Chatel, A.; Manier, N.; Northcott, G.; Tremblay, L.A. Plastic additives: challenges in ecotox hazard assessment. Peer.J. 2021, 9, 11300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, 1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akoueson, F.; Paul-Pont, I.; Tallec, K.; Huvet, A.; Doyen, P.; Dehaut, A.; Duflos, G. Additives in polypropylene and polylactic acid food packaging: Chemical analysis and bioassays provide complementary tools for risk assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 857, 159318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, L.; Bartosova, Z.; Braun, K.; Oehlmann, J.; Völker, C.; Wagner, M. Plastic products leach chemicals that induce in vitro toxicity under realistic use conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 11814–11823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feld, L.; da Silva, V.H.; Strand, J. Characterization of foamed plastic litter on Danish reference beaches – Pollution assessment and multivariate exploratory analysis. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2022, 180, 113774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

European standard EN 14735:2005; Characterization of waste—preparation of waste samples for ecotoxicity tests. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2005.

-

ISO 21338:2010; Water Quality—Kinetic determination of the inhibitory effects of sediment, other solids and coloured samples on the light emission of Vibrio fischeri (Kinetic luminescent bacteria test). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- OECD 201. Guidelines for the testing of chemicals. Freshwater alga and cyanobacteria, growth inhibition test; Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development: Paris, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- OECD 221. Lemna sp. growth inhibition test. Guideline for the testing of chemicals; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- US EPA. Standard methods for examination of water and wastewater. 2005. Available online: http://www.standardmethods.org/store (accessed on 6 February 2020).

- OECD 202. Daphnia sp. acute immobilisation test. Guideline for the testing of chemicals; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

-

ISO 14380; Water Quality—Determination of the acute toxicity to Thamnocephalus platyurus (Crustacea, Anostraca). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

-

ISO 14371; Water Quality—Determination of fresh water sediment toxicity to Heterocypris incongruens (Crustacea, Ostracoda). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- OECD 211. Daphnia magna reproduction test. Guideline for the testing of chemicals; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development: Paris, France, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vindimian, E. REGTOX EV7.1.2.xls MS-Excel Macro Software. 2001. Available online: http://www.normalesup.org/~vindimian/download.html (accessed on 14 June 2023).

- Ekvall, M.T.; Gimskog, I.; Hua, J.; Kelpsiene, E.; Lundqvist, M.; Cedervall, T. Size fractionation of high-density polyethylene breakdown nanoplastics reveals different toxic response in Daphnia magna. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, B. M.; Jantunen, L.M.; Rochman, C. M. Polyurethane microplastics and associated tris(chloropropyl)phosphate additives both affect development in larval fathead minnow Pimephales promelas. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2025, 44, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinova, I.; Ivask, A.; Heinlaan, M.; Mortimer, M.; Kahru, A. Ecotoxicity of nanoparticles of CuO and ZnO in natural water. Environ. Pollut. 2010, 158, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinova, I.; Niskanen, J.; Kajankari, P.; Kanarbik, L.; Käkinen, A.; Tenhu, H.; Penttinen, O.-P.; Kahru, A. Toxicity of two types of silver nanoparticles to aquatic crustaceans Daphnia magna and Thamnocephalus platyurus. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2013, 20, 3456–3463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinova, I.; Kanarbik, L.; Sihtmäe, M.; Kahru, A. Toxicity of water accommodated fractions of Estonian shale fuel oils to aquatic organisms. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2016, 70, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Xiang, Y.; He, D.; Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, S.; Pan, X. Leaching behavior of fluorescent additives from microplastics and the toxicity of leachate to Chlorella vulgaris. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 678, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, J.; Lundqvist, M.; Naidu, S.; Ekvall, M.T.; Cedervall, T. Environmental risks of breakdown nanoplastics from synthetic football fields. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 347, 123652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, J.; Sakka, Y.; Bertrand, C.; Köser, J.; Filser, J. Adaptation of the Daphnia sp. acute toxicity test: miniaturization and prolongation for the testing of nanomaterials. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 2201–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, O.; Kalbe, U.; Richter, E.; Egeler, P.; Römbke, J.; Berger, W. New approach to the ecotoxicological risk assessment of artificial outdoor sporting grounds. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 175, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, J.; Vojtová, L.; Bednařík, K.; Kučerík, J.; Vávrová, M.; Jančář, J. Development of novel environmental friendly polyurethane foams. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2010, 8, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtová, L.; Vávrová, M.; Bebnařík, K.; Šucman, E.; David, J.; Jančář, J. Preparation and ecotoxicity assessment of new biodegradable polyurethane foams. J. Environ. Sci. Health., Part A 2007, 42, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wik, A.; Dave, G. Acute toxicity of leachates of tire wear material to Daphnia magna variability and toxic components. Chemosphere 2006, 64, 1777–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Huang, G.; Han, D. Ecotoxicity of plastic leachates on aquatic plants: Multi-factor multi-effect meta-analysis. Water Res. 2025, 268, Part A, 122577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokstad, J.; Daling, P.; Buffagni, M.; Johnsen, S. Chemical and ecotoxicological characterisation of oil–water systems. Spill. Sci. Technol. Bull. 1999, 5, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusot, M.; Gardon, T.; Richmond, T.; Jezequel, R.; Barbier, E.; Gaertner-Mazouni, N. Chemical toxicity of leachates from synthetic and natural-based spat collectors on the embryo-larval development of the pearl oyster, Pinctada margaritifera. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, J.; Jiao, M.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, W.; Li, W.; Xu, P.; Wan, B. Mechanistic insight into the adverse outcome of tire wear and road particle leachate exposure in zebrafish (Danio rerio) larvae. Environ. Int. 2023, 178, 108053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Foamed plastic consumer products.

Table 1.

Foamed plastic consumer products.

| |

Consumer product |

Type of foam |

Flexibility |

Polymer1 |

| KP-1 |

kneeling pad |

closed cell |

rigid |

PE |

| KP-2 |

kneeling pad |

closed cell |

rigid |

PE |

| KP-3 |

kneeling pad |

closed cell |

slightly flexible |

PE |

| PACK |

packaging foam |

open cell |

flexible |

mixture |

| SPON |

dish sponge |

open cell |

flexible |

PUR |

| ISOL |

isolation foam |

closed cell |

flexible |

mixture (incl PUR, EVA) * |

Table 2.

Test organisms and exposure settings of the toxicity assays.

Table 2.

Test organisms and exposure settings of the toxicity assays.

| Test species |

Test conditions |

Toxicity endpoint |

Standard |

| |

Duration |

°C |

Illumination |

|

|

Bacteria

Vibrio fischeri

|

30 min |

20 °C |

continuous |

bioluminescence inhibition |

ISO 21338 |

Microalgae

Raphidocelis subcapitata1

|

72 h |

25 °C |

continuous |

growth inhibition |

OECD 201 |

Duckweed

Lemna minor

|

7 days |

25±1 °C |

continuous |

growth inhibition |

OECD 221 |

Crustaceans

Thamnocephalus platyurus

|

24 h |

25±1 °C |

in dark |

mortality |

ISO 14380 |

Crustaceans

Heterocypris incongruens

|

6 days |

25±1 °C |

in dark |

mortality, growth inhibition |

ISO 14371 |

Crustaceans

Daphnia magna

|

48 h |

21±1 °C |

in dark |

immobilization |

OECD 202 |

| Daphnia magna |

96 h |

21±1 °C |

16h/8h light/dark |

immobilization |

OECD 202* |

| Daphnia magna |

21 days |

21±1 °C |

16h/8h light/dark |

mortality, reproduction |

OECD 211 |

Table 3.

Toxicity of the eluates of foamed plastic consumer products to test organisms.

Table 3.

Toxicity of the eluates of foamed plastic consumer products to test organisms.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).