Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Context and Rationale

1.2. Literature Gap

1.3. Research Objectives

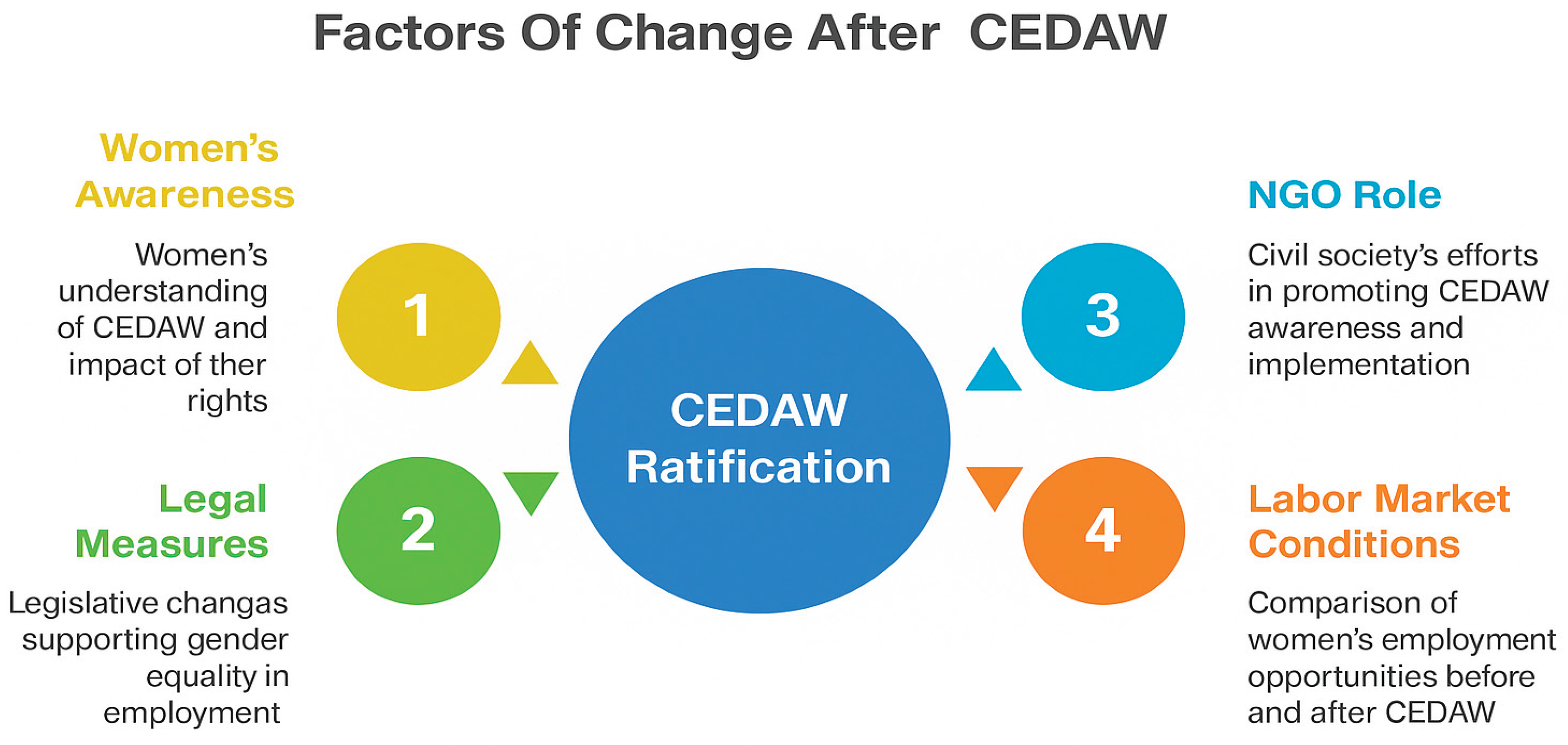

- Examining the impact of CEDAW ratification on government action regarding women’s employment by comparing labour-market conditions for women before and after ratification, focusing on formal employment opportunities.

- Evaluating the legal and legislative measures adopted since 2014 to harmonise Palestinian labour laws with CEDAW, and determining how far enacted reforms align with Article 11 obligations.

- Assessing women’s awareness of CEDAW, especially Article 11, and its moderating effect on the link between ratification and government action.

- Analysing the role of NGOs and civil society organisations in promoting CEDAW implementation.

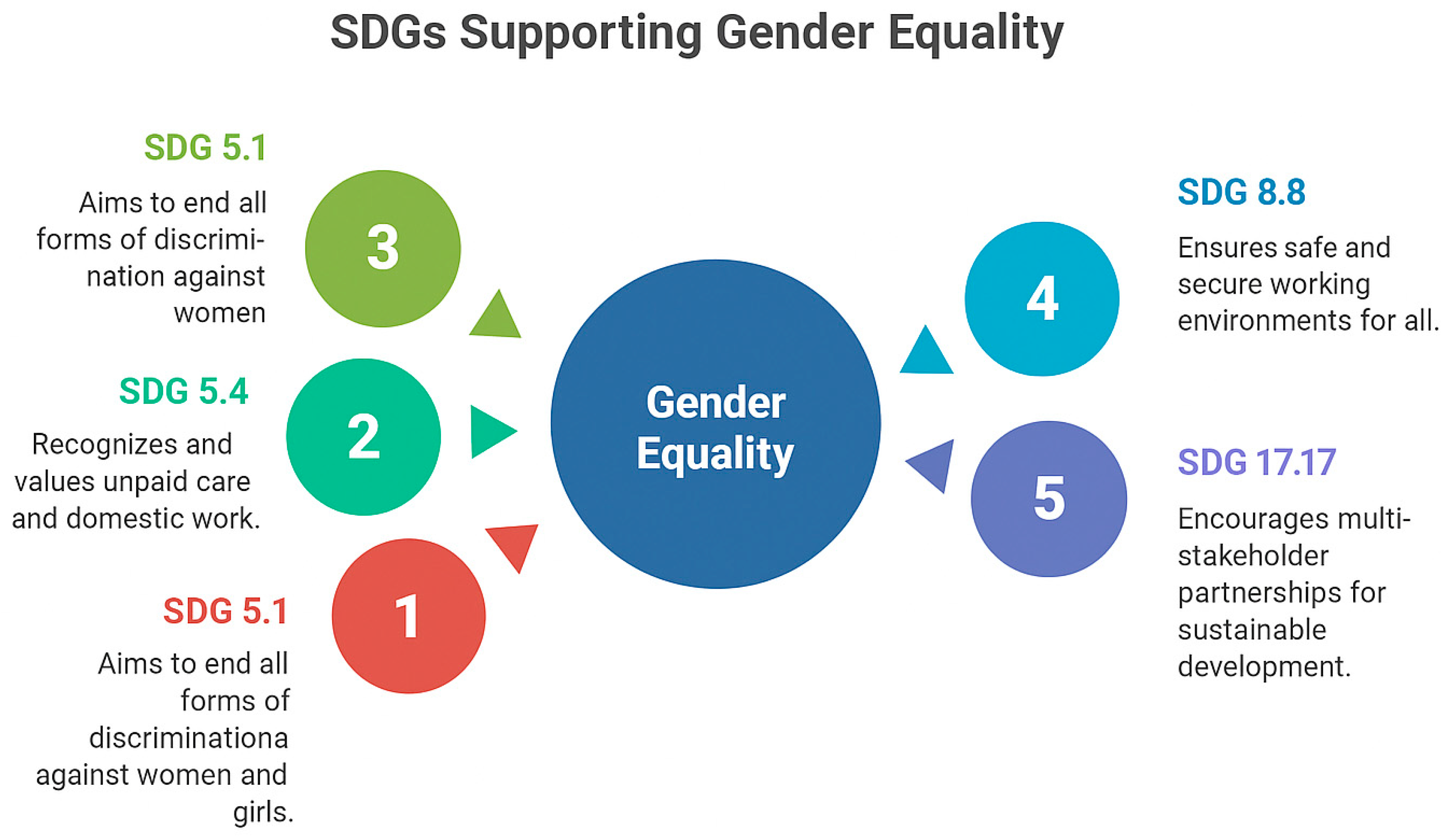

1.4. Link to the Sustainable Development Goals

1.5. Research Questions

- To what extent have legal and legislative measures in Palestine changed since the ratification of CEDAW to support gender equality in employment, and how do these reforms align with Article 11 of the Convention?

- How does women’s awareness of CEDAW influence their participation in the labour market and their advocacy for employment rights?

- What role do NGOs and civil society organizations play in promoting awareness and supporting the implementation of CEDAW in the Palestinian labour market context?

- How can the findings inform policy interventions to enhance women’s participation and ensure compliance with CEDAW commitments?

1.6. Literature Review

1.7. International Comparison and Sustainability Linkages

1.8. Implications for Palestine and Sustainable Labour Policy

1.9. Conceptual Framework: Factors of Change After CEDAW Ratification

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Quantitative Component

2.3. Qualitative Component

- (i).

- eight key-informant interviews (a. three senior government officials, and b. five civil-society/union leaders),

- (ii).

- 529 open-ended survey narratives submitted by working women as a part of the survey questionnaire,

- (iii).

- paired State and shadow reports on CEDAW implementation (2016-2024), and

- (iv).

- a legal-alignment matrix that compares Palestinian labour statutes with Article 11 obligations.

2.3.1. Hybrid Thematic Design and Analytic Workflow

2.3.2. Core Qualitative Themes (Derived from the Hybrid Thematic Analysis)

- Legislative Adaptation & Reform: tracks the extent, pace, and content of post-2014 legal amendments, highlighting partial alignment and persistent legislative gaps.

- Institutional Roles: maps the division of labour among government ministries, trade unions, NGOs, and international agencies in advancing or stalling CEDAW implementation.

- Barriers to Compliance: captures socio-cultural, workplace, and legal-administrative obstacles (patriarchal norms, weak inspections, wage-gap incentives, childcare deficits).

- CEDAW Impact on Participation: collates perceptions of whether ratification has changed women’s access to, retention in, and progression within the labour market.

- Private-Sector Role & Commitment: examines employer attitudes, cost concerns, and defensive hiring practices that shape Article 11 compliance outside the public sector.

- Awareness of Article 11: distinguishes symbolic recognition of CEDAW from substantive knowledge of specific employment rights and enforcement channels.

- Advocacy & Mobilisation: documents civil-society strategies (shadow reports, campaigns, coalitions) and the counter-pressures they face from conservative backlash.

- 8.

- Cross-cutting/Policy Recommendations: aggregates practical reform proposals voiced by interviewees and the day-to-day realities that motivate those proposals.

- 9.

- Social & Economic Impacts of Women’s Employment: reflects narratives linking women’s paid work to household resilience, poverty reduction, and community wellbeing.

- 10.

- National Strategy to Eliminate Discrimination: captures calls for a unified, cross-sector plan that embeds CEDAW principles in all labour-related legislation.

- 11.

- Real-Life Personal Experience: first-person accounts of unequal pay, harassment, promotion ceilings, and childcare hurdles, grounding abstract themes in lived reality.

- 12.

- Misunderstanding of CEDAW: records instances of the Convention being framed as a foreign or anti-religious agenda, fuelling resistance and misinformation.

2.4. Integration Strategy

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Limitations

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Findings

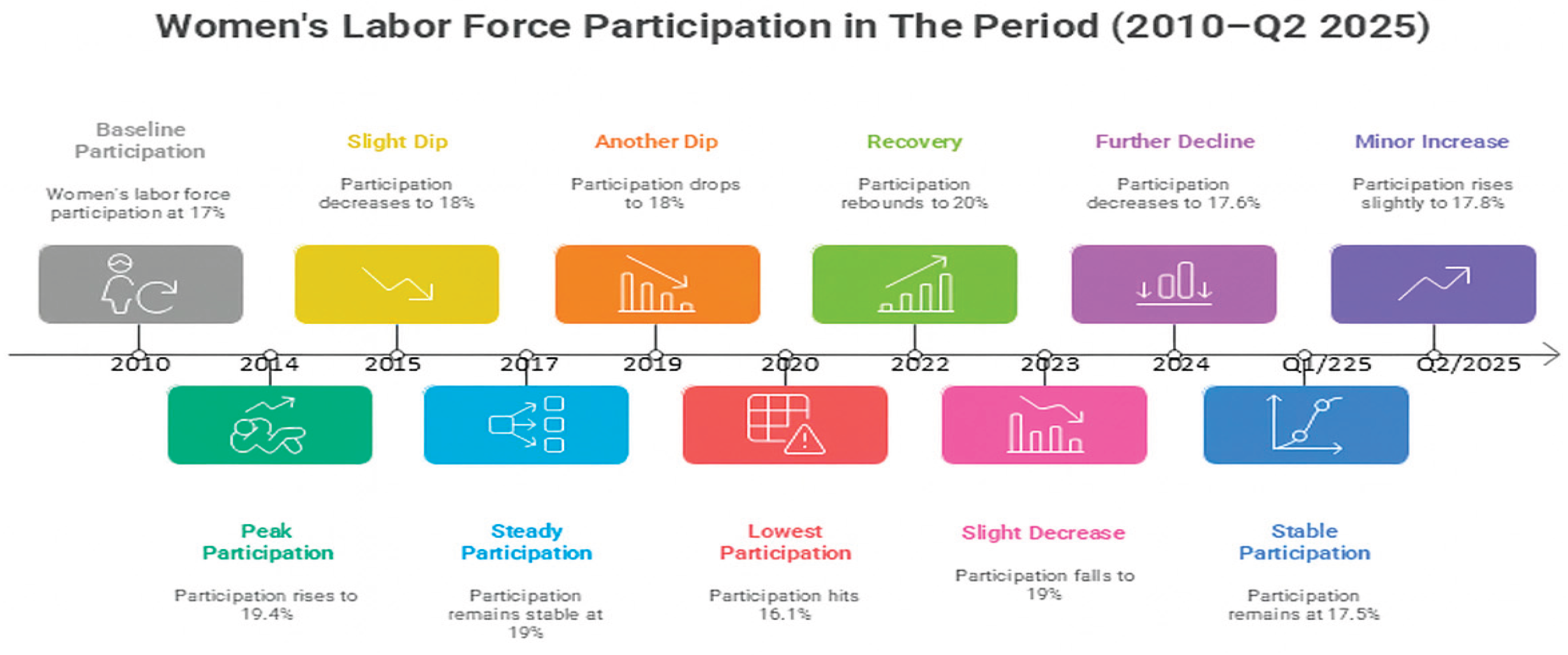

- First bullet; Female labour force participation (2010–mid-2025).

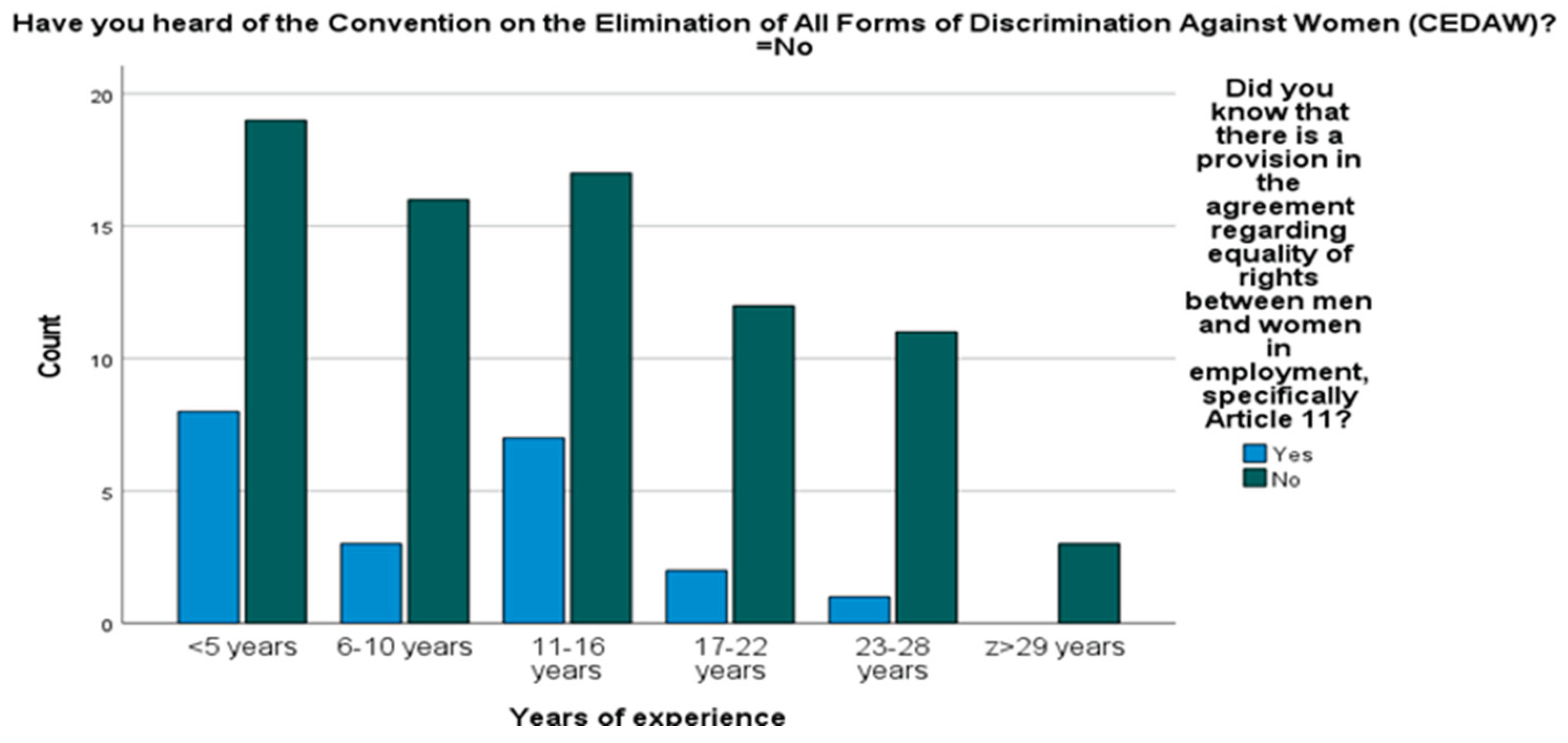

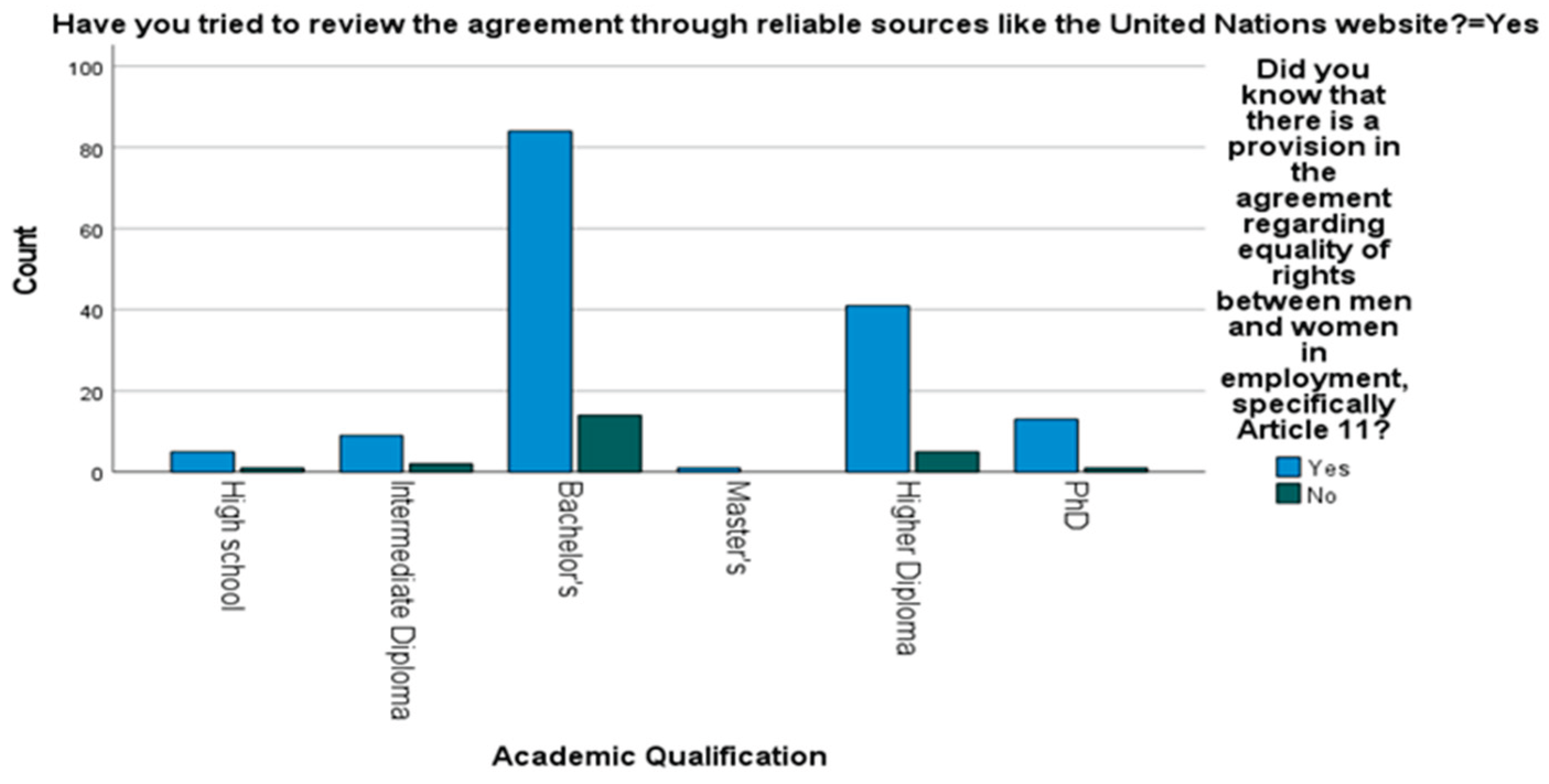

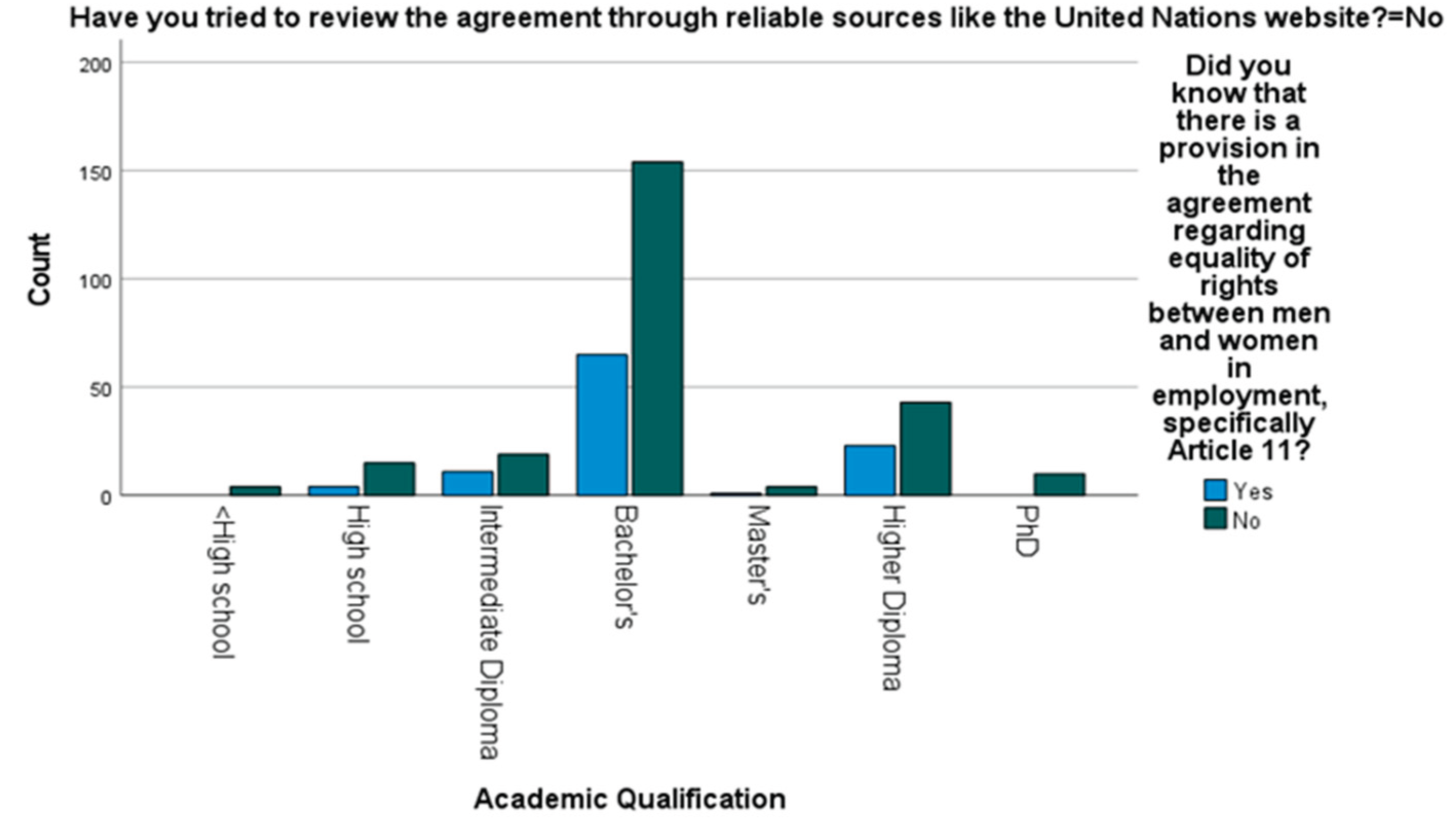

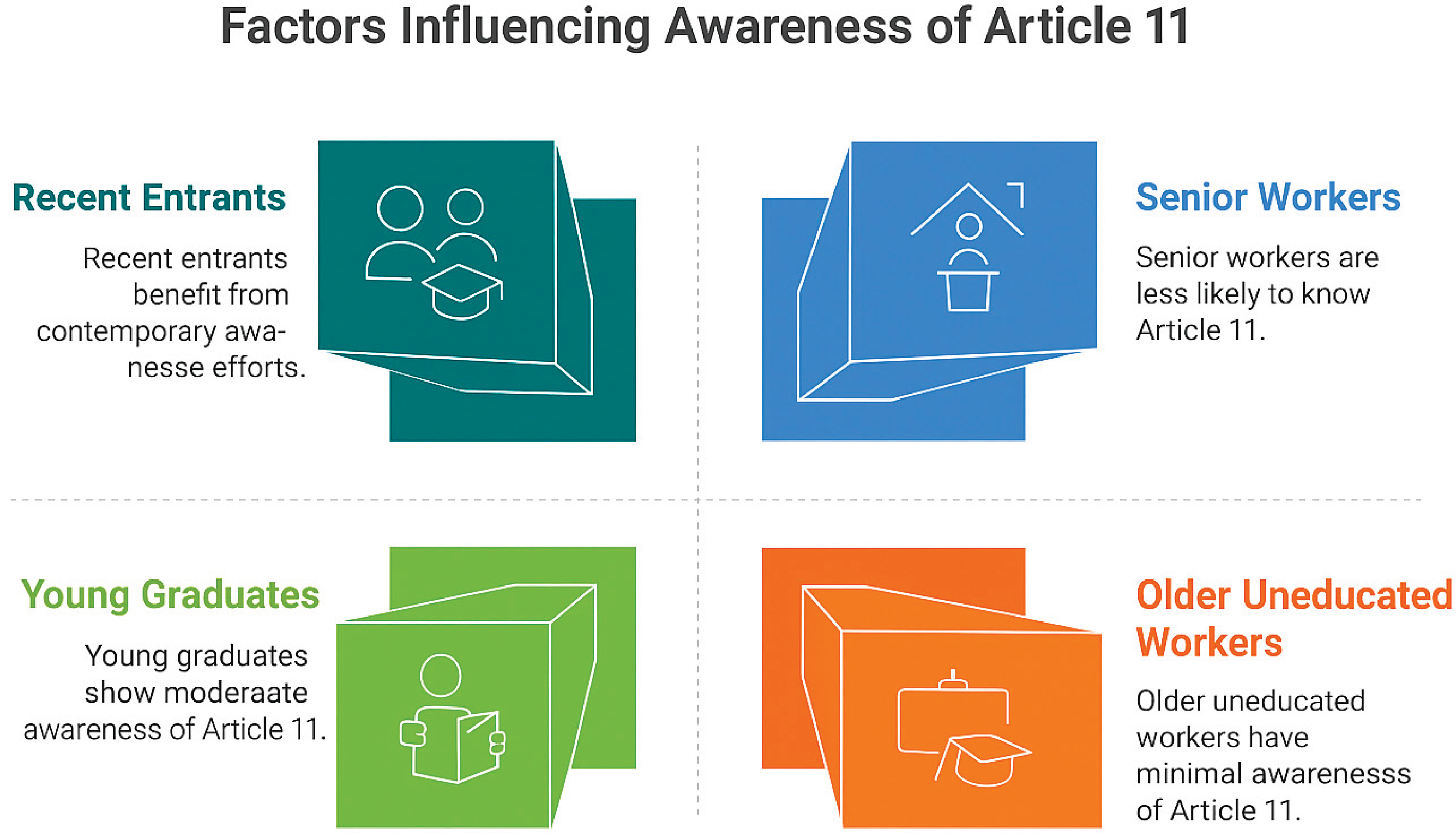

- Second bullet; Awareness and knowledge of CEDAW Article 11 (N = 529).

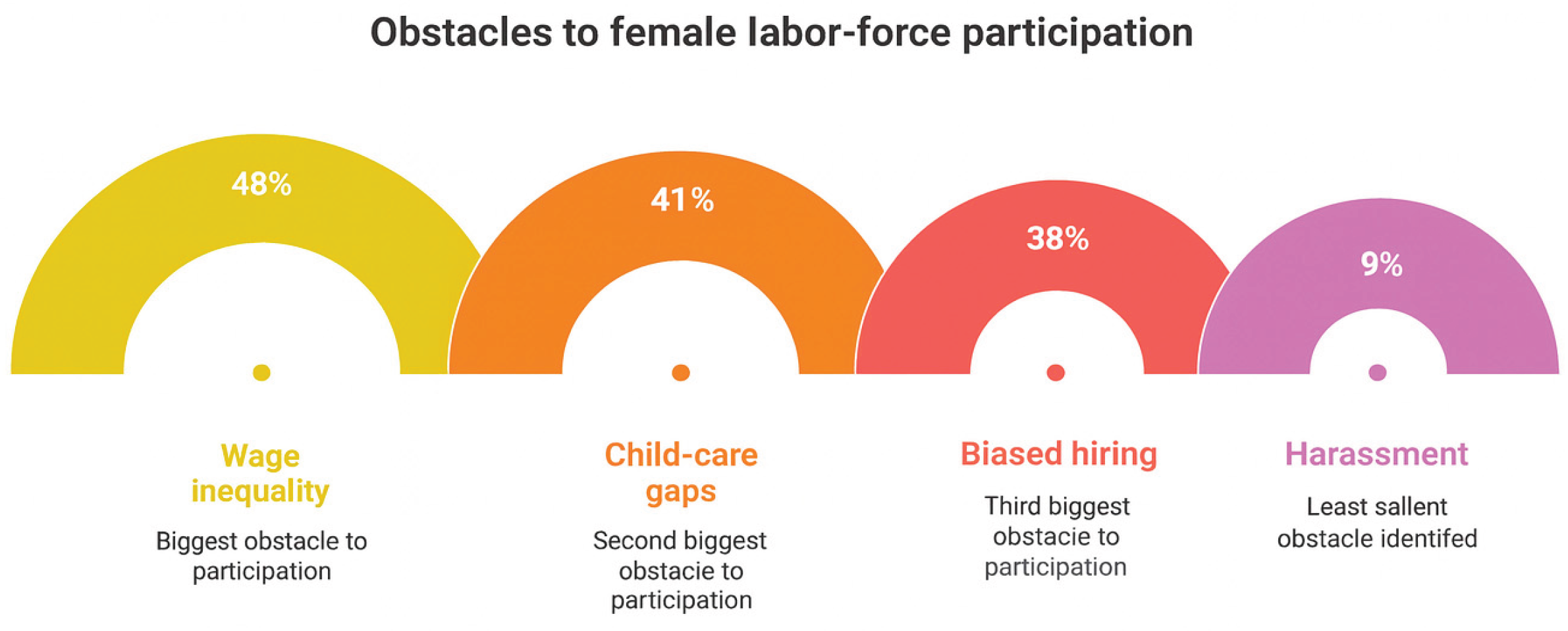

- Third bullet; Perceived labour market barriers.

- Fourth bullet; Age gradients in awareness.

- Fifth bullet; Experience and education.

- Sixth bullet; Shifts in Article 11 Awareness.

- Seventh bullet; Sectoral law coverage differences.

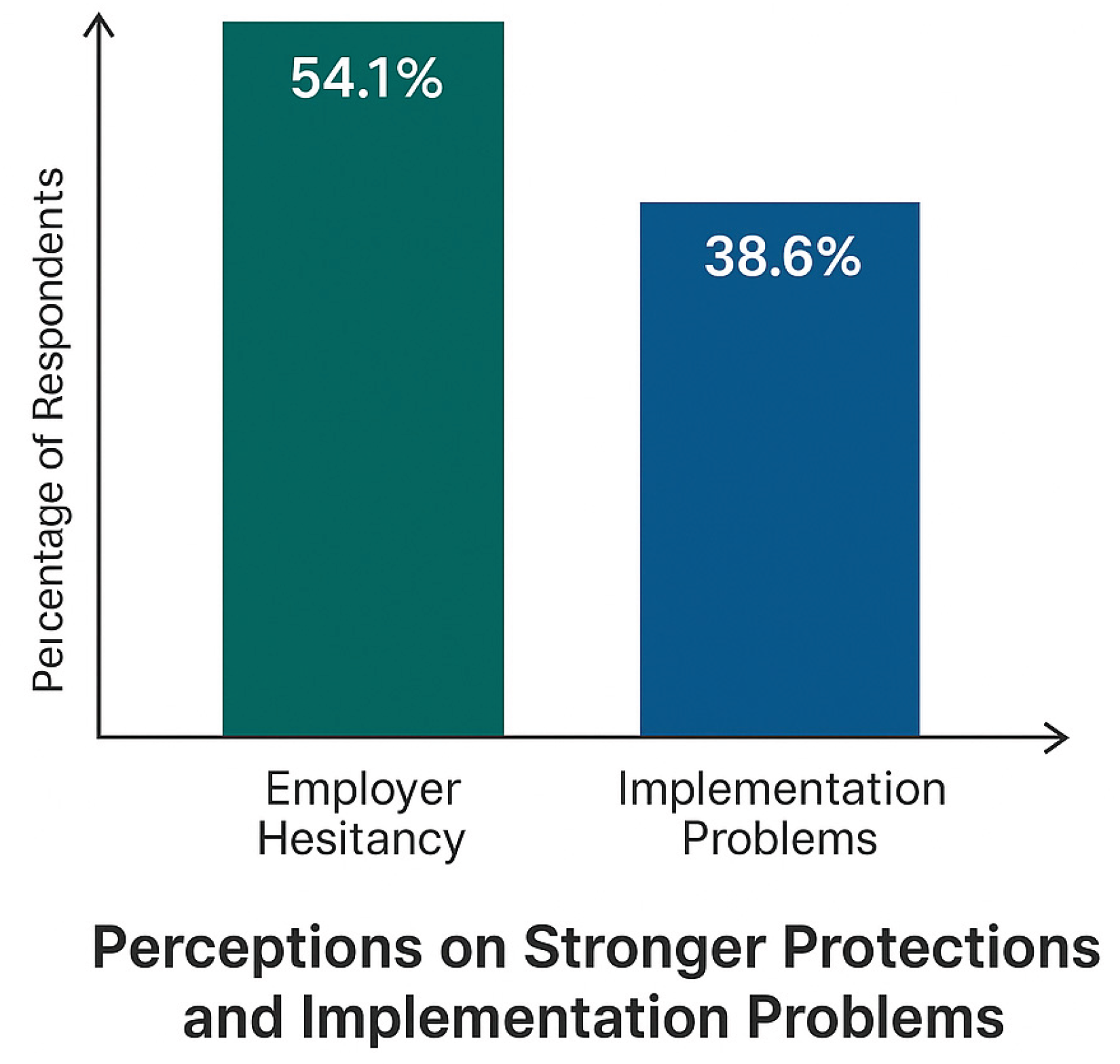

- Eighth bullet; Perceived employer response and implementation challenges.

- Ninth bullet; Knowledge confidence link.

3.2. Qualitative Findings

- First question; To what extent have legal and legislative measures in Palestine changed since the ratification of CEDAW to support gender equality in employment, and how do these reforms align with Article 11 of the Convention?

- Second question; How does women’s awareness of CEDAW influence their participation in the labour market and their advocacy for employment rights?

- Third question; Role of NGOs/civil society in promoting awareness and implementation

- Fourth Question; How can the findings inform policy interventions to enhance women’s participation and ensure compliance with CEDAW commitments?

- The principles of equality and discrimination must be codified into the existing laws.

- 2.

- Strengthening enforcement architecture.

- 3.

- Strengthening coordination and the principle of accountability within institutions.

- 4.

- Private sector involvement is crucial.

- 5.

- Addressing sociocultural resistance.

- Integrative Summary

3.3. Mixed Methods Integration (Quantitative ↔ Qualitative)

| New Research Question | Key Quantitative Evidence | Matched Qualitative Evidence (Summarised) | Integrated Interpretation (What This Means) |

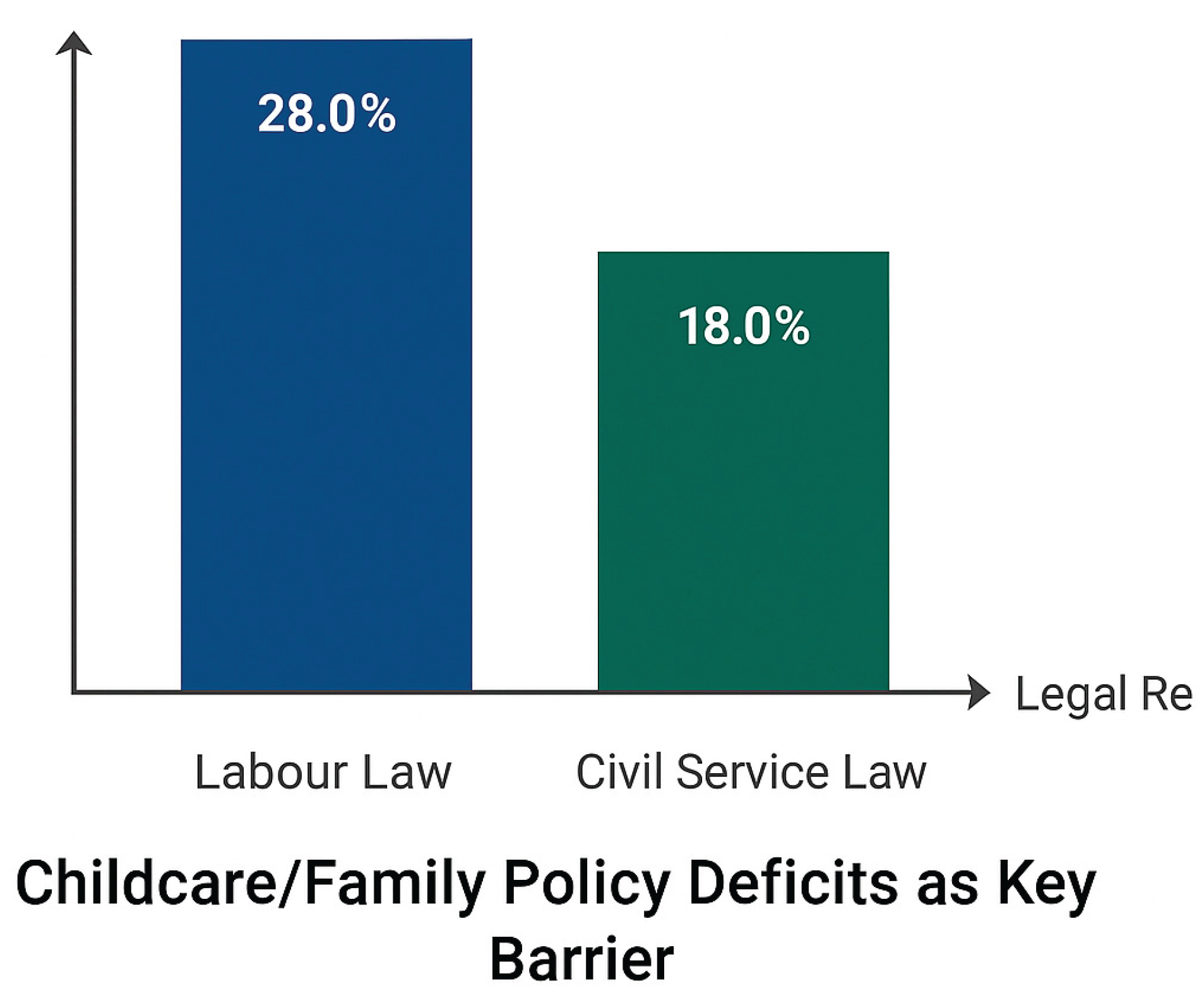

| RQ1. To what extent have legal and legislative measures in Palestine changed since the ratification of CEDAW to support gender equality in employment, and how do these reforms align with Article 11? | • Female LFP stagnant (16–20%) 2010–2025. • Weak perceptions of legal amendment (r ≈ .20–.22). • Childcare barrier is higher under Labour Law (28% vs 18%). • Knowledge not differing by legal regime (χ² ≈ 0.31). |

Implementation perceived as symbolic; no comprehensive amendments enacted; definitions of discrimination and harassment absent; enforcement under-resourced; public sector offers stable pay but promotion ceilings; private sector marked by wage gaps and job insecurity. | Normative change without structural lift. Ratification improved discourse and partial alignment “on paper,” but weak enforcement, fragmented governance, and informal labour practices prevent CEDAW Article 11 from translating into measurable participation gains. |

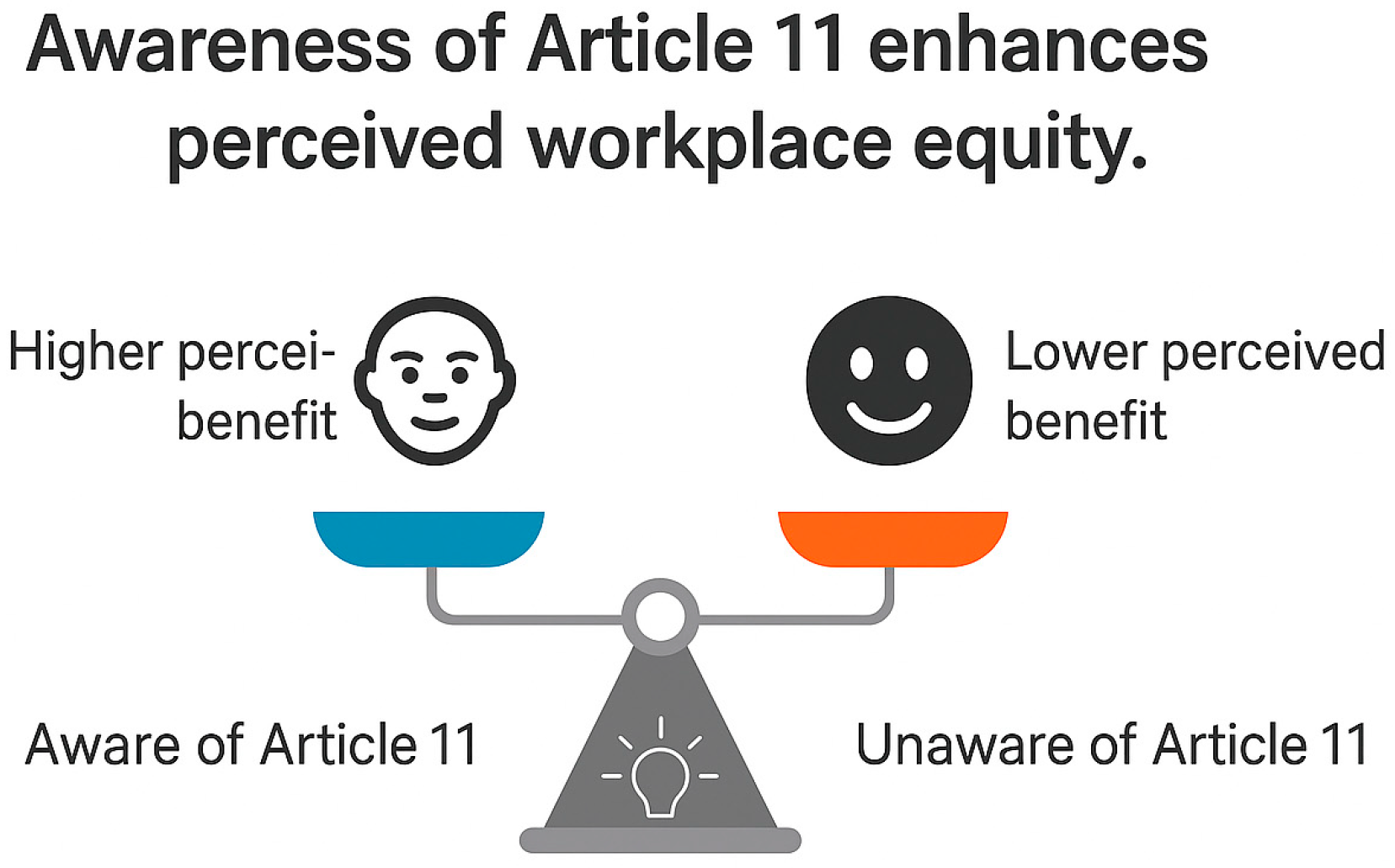

| RQ2. How does women’s awareness of CEDAW influence their participation in the labour market and advocacy for employment rights? | • Self-learning strongly predicts knowledge of Article 11 (r = .54, p < .001). • Knowledge linked to higher perceived usefulness (p = .036). • Older women hear of CEDAW more; younger women seek reliable sources. |

Awareness largely self-directed and uneven; official outreach is sporadic and focused on political rights more than employment; misinformation is widespread; digital media is used inconsistently by ministries and CSOs. | Awareness is necessary but insufficient. Genuine understanding arises from self-initiated learning rather than institutional education; inconsistent messaging and limited focus on labour rights restrict awareness from driving behavioural or advocacy outcomes. |

| RQ3. What role do NGOs and civil society organisations play in promoting awareness and supporting the implementation of CEDAW in the Palestinian labour market context? | • ~17% of respondents report CSO contact. • CSO contact correlates with deeper knowledge (r ≈ .20–.30). |

CSOs submit shadow reports and conduct advocacy and training; unions and NGOs act as intermediaries between international frameworks and local practice; cooperation with government remains ad hoc and leadership-dependent. | Active but under-institutionalised. Civil society sustains visibility of Article 11 and expands women’s knowledge base, yet limited partnership mechanisms and state dominance in rule-making constrain systematic policy uptake. |

| RQ4. How can the findings inform policy interventions to enhance women’s participation and ensure compliance with CEDAW commitments? | — (Derived from integrated mixed-methods synthesis) | Data convergence points to four priorities: legal codification of equality principles; stronger enforcement and inspection capacity; improved institutional coordination; and incentive-based support for employers. Sociocultural barriers require parallel awareness strategies. | Bridging ratification and implementation demands a dual approach: completing the legal architecture and operationalising enforcement and social-norm change. Only through combined legal, institutional, and societal measures can Article 11 commitments evolve from symbolic to substantive equality. |

4. Discussion

- Cultural: Patriarchal norms and religious framing undermine women’s claims (n≈19 in “patriarchal norms” sub-node), reinforcing bias in hiring/promotion and fuelling public scepticism toward CEDAW. This is what Hattab and Abu al-Rub presented when looking at these barriers through the lens of social norms; they reflect the continuity of normative restrictions that are repeated through patriarchal power structures and weak legal codification [8].

- Workplace: Child-care access (n=13), sexual harassment (n=9), wage gap (n=6), and low-level occupations recur, matching survey rankings: wage inequality 48%, child-care 41%, biased hiring/promotion 38%, harassment 9%.

- Legal/policy: High-salience nodes for Gaps/Legal Vacuum (n=54) and Enforcement Mechanisms (n=25) point to missing anchors (no discrimination definition; uneven maternity provisions; few executive regulations) and weak inspection/labour-court pathways.

- Economic/structural: Economic constraints (n=7) and occupation-related constraints (n=14) shape opportunity sets and enforcement reach, amplifying employers’ cost-centred calculus around maternity and compliance.

5. Conclusions

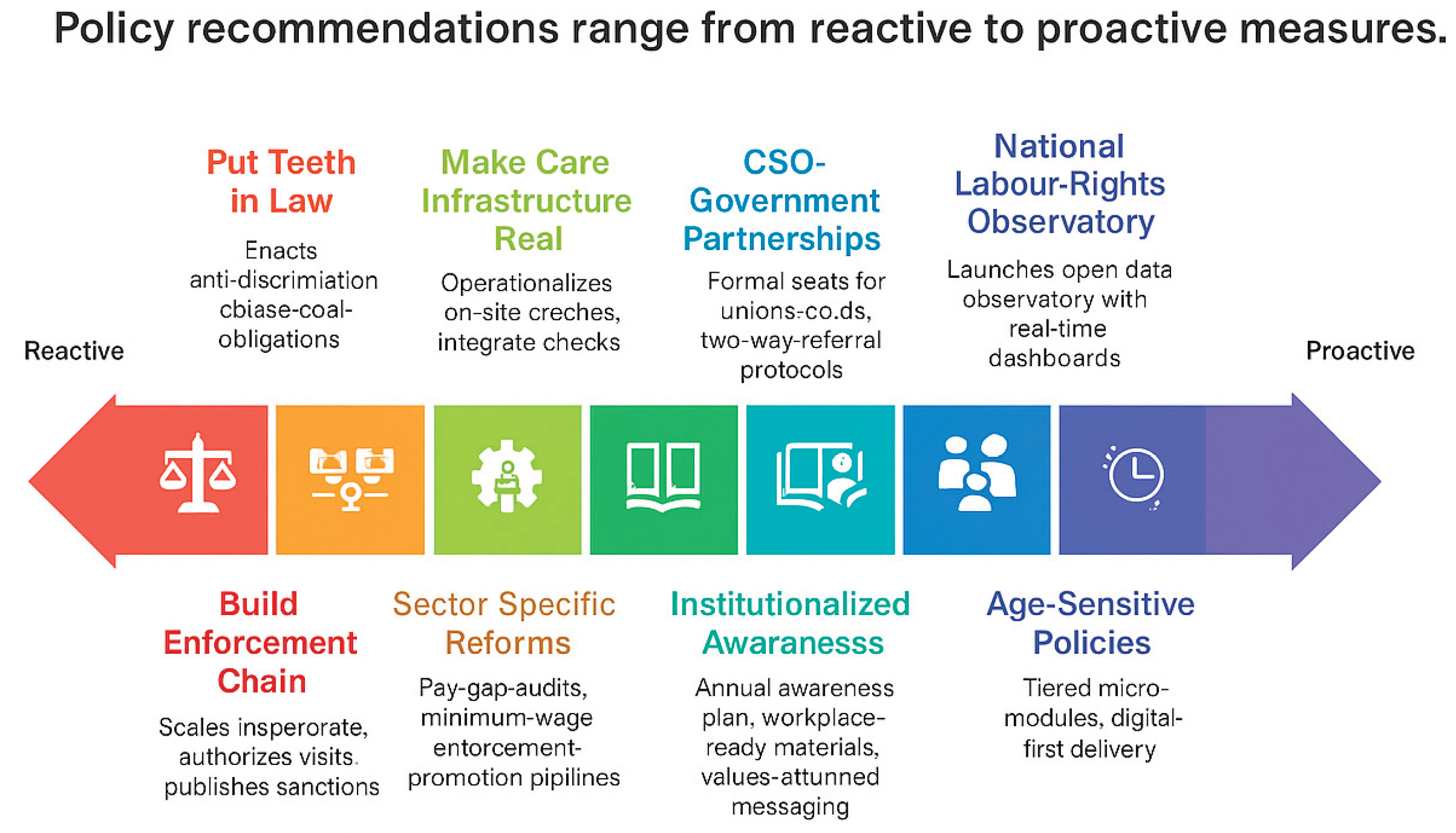

6. Policy Recommendations / Operationalizing CEDAW Article 11 in Palestine

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CEDAW | Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women |

| CSO(s) | Civil Society Organisation(s) |

| DWRC | Democracy & Workers’ Rights Center |

| HJC | High Judicial Council |

| HR | Human Resources |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| KPI(s) | Key Performance Indicator(s) |

| MoF | Ministry of Finance (State of Palestine) |

| MoJ | Ministry of Justice |

| MoL | Ministry of Labour |

| MoNE | Ministry of National Economy |

| MoSA | Ministry of Social Affairs (now MoSD in some documents) |

| MoWA | Ministry of Women’s Affairs |

| NGO(s) | Non-Governmental Organisation(s) |

| PCBS | Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics |

| PGFTU | General Federation of Palestinian Trade Unions |

| PLC | Palestinian Legislative Council |

| RWDS | Rural Women Development Society |

| SDG(s) | Sustainable Development Goal(s) |

| SHAMS | Human Rights and Democracy Media Center SHAMS |

| UN | United Nations |

| UN Women | United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women |

References

- UN. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1979. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-elimination-all-forms-discrimination-against-women.

- PCBS, Labor Force Survey: (July-September, 2023), Third Quarter, 2023, Ramallah, West Bank: PCBS, 2023. http://www.pcbs.gov.ps/.

- Gahagan, C. The Right to Work: How a Human Rights Treaty Reduces the Informal. Florida State University, Department of Political Science: Tallahassee, FL, USA, 2023.

- Word Bank, "Women, Business and the Law," World Bank, Washington, DC, USA, 2024. https://wbl.worldbank.org.

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.]. Available: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda.

- Comstock, L.A. Signing CEDAW and Women's Rights: Human Rights Treaty Signature and Legal Mobilization; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; p. 49. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, L.M. The Effects of the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) on Mobilization: Analysis of Mobilization as a Compliance Mechanism. Master's Thesis, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA, 2023.

- Hattab, A.; Abualrob, A. Under the veil: Women's economic and marriage. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 110. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Persistent Gender Gaps at Work Make it Necessary to Adopt Transformative Measures. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/resource/news/ilo-persistent-gender-gaps-work-make-it-necessary-adopt-transformative (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Gevrek, D.; Middleton, K. Globalization and women's and girls' health in 192 UN-member countries. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2016, 43, 692–721. [CrossRef]

- Rueda, V.C. Women Migrant Workers' Labour Market Situation in West Africa; ILO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. https://researchrepository.ilo.org.

- Sinha, S. Gender Based Inequities in the World of Work: Insights from Latin America, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia. In Inequality, Democracy and Development under Neoliberalism and Beyond; Seventh South-South Institute: Bangkok, Thailand, 2014; pp. 109–126. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35171358.pdf#page=109.

- Pruitt, L.R. Migration, Development, and the Promise of CEDAW for Rural Women. Michigan Journal of International Law 2009, 30, 1052–2867. Available online: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol30/iss3/7.

- UN Women. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Available online: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/cedaw.htm (accessed on 26 March 2025).

- Prigge, K.; Thyen, K. Rural Women's Economic Empowerment in the Maghreb: A Materialist Critique. Middle East Crit. 2025, 34, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Muktadir, M.G. SPSS: An imperative quantitative data analysis tool for social science research. Int. J. Res. Innov. Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 300–302.

- The Practice of Qualitative Data Analysis: Research Examples Using MAXQDA, Gizzi, M.C.; Rädiker, S. (Eds.) The Practice of Qualitative Data Analysis: Research Examples Using MAXQDA; MAXQDA Press: Berlin, Germany, 2024.

| no. | Data Source Group | Participants/unit counts | Purpose in analysis |

| i.a | Government KIIs | 3 senior officials (Women’s Affairs, Labour, Justice) | Capture the State’s view on post-CEDAW reforms and enforcement mechanisms. |

| i.b | Civil-society/unions KIIs | 5 leaders from NGOs & trade unions (General Union of Palestinian Women, Rural Women Society, SHAMS, Trade Union, Democracy and Workers' Rights Center) | Document advocacy strategies, monitoring roles, and field-level barriers. |

| ii | Working-women voices | 529 open answers embedded in the online survey (treated as short narrative “mini-interviews”) | Provide grass-roots perceptions that triangulate KII findings. |

| iii | Desk-review (CEDAW monitoring) | Annual state vs. shadow reports 2016-2024 | Identify areas of agreement/contradiction in official vs. NGO assessments. |

| iv | Desk-review (legal alignment) | Side-by-side matrix of Labour & Civil-Service laws vs. Article 11 obligations | Map legislative gaps without disclosing numerical scores. |

| NO | RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE POLICY LEVEL | |

| 1 | Description | Put teeth in the law (define, align, publish) |

| Rationale (from results) | No statutory definition of discrimination; uneven maternity/childcare rules; draft reforms not gazetted, leaving Article 11 largely declaratory. Actions. |

|

| Actions. | Adopt a unified gender anti-discrimination framework across labour laws and finalise and gazette the 17 bylaws with enforceable, time-bound regulations. | |

| KPIs (12–18 mo). | Discrimination definition enacted; # of executive regulations gazetted; % ministries issuing compliance circulars. | |

| Lead actors. | MoL, MoJ, Presidency/PLC; support from CSO. | |

| 2 | Description | Build an enforcement chain that works |

| Rationale (from results) | Inspection is understaffed; courts are slow; penalties are rare, so compliance is patchy. | |

| Actions. | Scale inspectorate, authorise unannounced visits, publish a sanctions schedule; pilot fast-track labour benches/courts. | |

| KPIs (12–18 mo). | Inspections per 1,000 establishments; % unannounced visits; median case duration; sanction collection rate. | |

| Lead actors. | MoL (Inspection & occupational safety and health (OSH) ), High Judicial Council, Attorney General. | |

| 3 | Description | Sector-specific reforms (private vs public) |

| Rationale (from results) | Private sector: wage gaps, childcare deficits, precarious contracts; Public sector: standardised pay but promotion ceilings. | |

| Actions. | Private sector: enforce pay-gap audits, wage compliance, anti-harassment rules, and SME maternity support; Public sector: ensure transparent, gender-balanced promotion pathways. | |

| KPIs (12–18 mo). | % firms completing pay-gap audits; minimum-wage compliance rate; women’s share in Grade-A /leadership posts. | |

| Lead actors. | MoL, Pay-Equity Committee, employers’ associations; CSOs (public sector). | |

| 4 | Description | Make care infrastructure real |

| Rationale (from results) | Childcare obligations are not enforceable; women under the Labour Law report higher childcare barriers than under the Civil Service Law. | |

| Actions. | Operationalise on-site crèches or pooled funds/allowances, phased by firm size/sector; integrate checks into inspection. | |

| KPIs (12–18 mo). | % employers providing childcare/allowances; inspection coverage of family-friendly provisions. | |

| Lead actors. | MoL, MoSA, MoF; municipalities for permitting / monitoring. | |

| 5 | Description | Institutionalised awareness (workplace-based; misinformation-proof) |

| Rationale (from results) | Awareness is broad but shallow; outreach is not continuous; misinformation persists; content often skews to non-labour topics. | |

| Actions. | Develop a joint awareness plan with workplace-ready Article 11 materials, using value-aligned messaging and trusted messengers, and embed brief modules in onboarding, promotion, and grievance processes. | |

| KPIs (12–18 mo). | ≥ 60% consulted a reliable source or had direct CSO contact; rise in perceived usefulness of Article 11. | |

| Lead actors. | MoWA, MoL, CSO coalitions; media units. | |

| 6 | Description | CSO–government partnerships (formalise the quartet) |

| Rationale (from results) | CSOs/unions sustain visibility (shadow reports, clinics), yet the partnership is under-institutionalised; the government did not publicly defend CEDAW during the backlash. | |

| Actions. | Provide unions/CSOs with formal seats on drafting and monitoring committees with quarterly reviews, and establish two-way referral protocols between hotlines/legal clinics and inspectorate/courts with ≤30-day feedback. | |

| KPIs (12–18 mo). | # joint policy notes adopted; % complaints resolved ≤ 90 days; public trust measures. | |

| Lead actors. | MoL, MoWA, CSO coalitions, unions (with ILO support). | |

| 7 | Description | Age-sensitive policies |

| Rationale (from results) | Older cohorts are more likely to have heard of CEDAW; younger cohorts are more likely to consult reliable sources and recognize Article 11 as an actionable channel gap. | |

| Actions. | Tiered, in-work micro-modules for 18–28 / 29–50 / 51+; digital-first delivery leveraging MoWA’s intensive social-media use. | |

| KPIs (12–18 mo). | ≥ 60% reliable-source consultation; increased Article 11 knowledge across age groups. | |

| Lead actors. | MoL, MoWA, HR units; unions/CSOs | |

| 8 | Description | Create a National Labour-Rights Observatory |

| Rationale (from results) | No national observatory tracks outcomes (wage gaps, harassment, case times), hindering accountability and learning. | |

| Actions. | Launch an open-data observatory (MoL + PCBS + universities/CSOs) with real-time dashboards on equal pay, harassment, childcare compliance, inspections, and case durations. | |

| KPIs (12–18 mo). | Public dashboards online; quarterly updates; # legislative/inspection actions triggered by observatory evidence. | |

| Lead actors. | PCBS & MoL; co-leads by universities, CSOs. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).