Submitted:

05 December 2025

Posted:

08 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Adenosine A1 Receptors (A1Rs) in Epilepsy

3. A2A Receptors (A2ARs) in Epilepsy

4. A3 Receptors (A3ARs) in Epilepsy

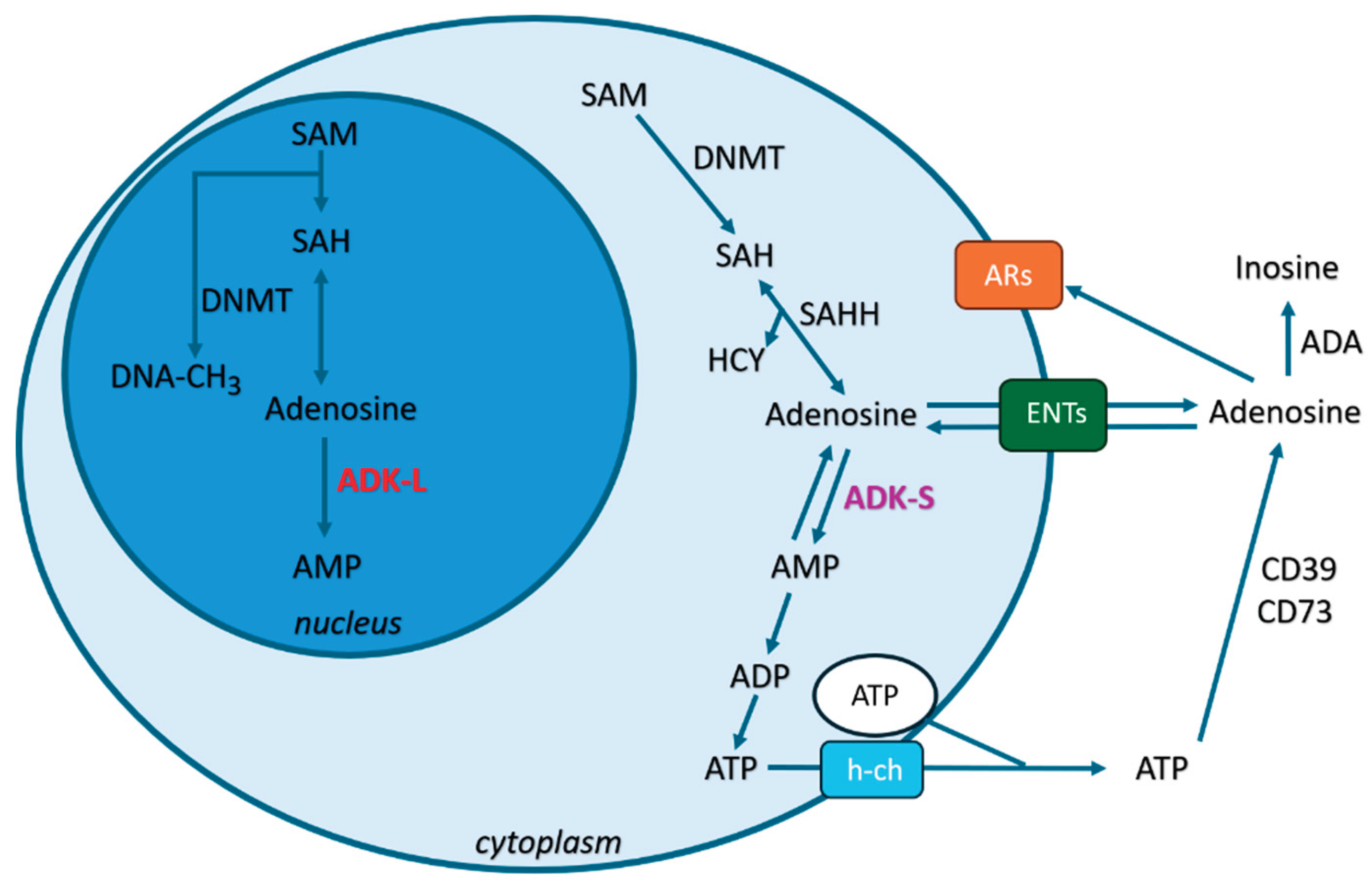

5. ADK-S in Epilepsy: Modulating Extracellular/Synaptic Adenosine Levels and Inhibiting Seizures in an Adenosine Receptor-Dependent Way

6. ADK-L in Epilepsy: Modulating Adenosine Receptor-Independent Epigenetic Mechanisms

7. Future Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GAT-1 | GABA transporter type 1 |

| ADK | adenosine kinase |

| ADK-S | short isoform of adenosine kinase |

| ADK-L | long isoform of adenosine kinase |

| ASMs | antiseizure medications |

| GABA | gamma-aminobutyric acid |

| ADA | adenosine deaminase |

| ENTs | equilibrative nucleoside transporters |

| A1Rs | A1 receptors |

| A2ARs | A2A receptors |

| A2BRs | A2B receptors |

| A3Rs | A3 receptors |

| GPCR | G protein-coupled receptor |

| DBS | deep brain stimulation |

| SRSs | spontaneous recurrent seizures |

| GLT-1 | glutamate transporter-1 |

| SAM | S-adenosylmethionine |

| 5-mC | 5-methylcytosine |

| SAH | S-adenosylhomocysteine |

| SAHH | SAH hydrolase |

| HCY | homocysteine |

| TLE | temporal lobe epilepsy |

| DNMTs | DNA methyltransferases |

| 5-ITU | 5-iodotubercidin |

| VNS | vagus nerve stimulation |

| SNPs | single nucleotide polymorphisms |

| h-ch | hemichannels |

References

- Kwan, P.; Schachter, S.C.; Brodie, M.J. Drug-resistant epilepsy. N Engl J Med 2011, 365, 919–926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Brodie, M.J.; Liew, D.; Kwan, P. Treatment Outcomes in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Epilepsy Treated With Established and New Antiepileptic Drugs: A 30-Year Longitudinal Cohort Study. JAMA Neurol 2018, 75, 279–286. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Fan, Y.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, B.; Lu, C. In vivo delivery of a XIAP (BIR3-RING) fusion protein containing the protein transduction domain protects against neuronal death induced by seizures. Exp Neurol 2006, 197, 301–308. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Lu, C.; Xia, Z.; Xiao, B.; Luo, Y. Inhibition of caspase-8 attenuates neuronal death induced by limbic seizures in a cytochrome c-dependent and Smac/DIABLO-independent way. Brain Res 2006, 1098, 204–211. [Google Scholar]

- Aronica, E.; Zurolo, E.; Iyer, A.; de Groot, M.; Anink, J.; Carbonell, C.; van Vliet, E.A.; Baayen, J.C.; Boison, D.; Gorter, J.A. Upregulation of adenosine kinase in astrocytes in experimental and human temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T. Epilepsy and Associated Comorbidities. In Neuropsychiatry (Lond); 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, P.; Kaminski, R.M.; Koepp, M.; Loscher, W. New epilepsy therapies in development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2024, 23, 682–708. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terman, S.W.; Kirkpatrick, L.; Akiyama, L.F.; Baajour, W.; Atilgan, D.; Dorotan, M.K.C.; Choi, H.W.; French, J.A. Current state of the epilepsy drug and device pipeline. Epilepsia 2024, 65, 833–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vezzani, A.; Ravizza, T.; Bedner, P.; Aronica, E.; Steinhauser, C.; Boison, D. Astrocytes in the initiation and progression of epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol 2022, 18, 707–722. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, Z.; Gao, R.; Wang, R.; Li, T. Proteome-Wide Mendelian Randomization Reveals Novel Protein Targets for Epilepsy. Curr Neuropharmacol 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Boison, D. Adenosine dysfunction in epilepsy. Glia 2012, 60, 1234–1243. [Google Scholar]

- Boison, D.; Steinhauser, C. Epilepsy and astrocyte energy metabolism. Glia 2018, 66, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boison, D. Adenosine kinase: exploitation for therapeutic gain. Pharmacol Rev 2013, 65, 906–943. [Google Scholar]

- Boison, D. The adenosine kinase hypothesis of epileptogenesis. Prog Neurobiol 2008, 84, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Lytle, N.; Lan, J.Q.; Sandau, U.S.; Boison, D. Local disruption of glial adenosine homeostasis in mice associates with focal electrographic seizures: a first step in epileptogenesis? Glia 2012, 60, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Ren, G.; Lusardi, T.; Wilz, A.; Lan, J.Q.; Iwasato, T.; Itohara, S.; Simon, R.P.; Boison, D. Adenosine kinase is a target for the prediction and prevention of epileptogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest 2008, 118, 571–582. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, G.; Gao, Q.; Guan, Y.; Zhai, F.; Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Yao, K.; Qi, X.; Li, T. Upregulation of adenosine kinase in Rasmussen encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2013, 72, 1000–1008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Luan, G.; Gao, Q.; Zhai, F.; Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Li, T. Adenosine kinase expression in cortical dysplasia with balloon cells: analysis of developmental lineage of cell types. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2015, 74, 132–147. [Google Scholar]

- Luan, G.; Wang, X.; Gao, Q.; Guan, Y.; Wang, J.; Deng, J.; Zhai, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, T. Upregulation of Neuronal Adenosine A1 Receptor in Human Rasmussen Encephalitis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2017, 76, 720–731. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Gao, Q.; Tang, C.; Deng, J.; Xiong, Z.; Kong, X.; Guan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Boison, D.; Luan, G.; Li, T. Aberrant adenosine signaling in patients with focal cortical dysplasia. Mol Neurobiol 2023, 60, 4396–4417. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Wang, J.; Xiong, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, C.; Zhang, J.; Guan, Y.; Chen, F.; Yao, K.; Teng, P.; Zhou, J.; Zhai, F.; Boison, D.; Luan, G.; Li, T. Ectopic expression of neuronal adenosine kinase, a biomarker in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy without hippocampal sclerosis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2023, 49, e12926. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Tang, C.; Guan, Y.; Chen, F.; Gao, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhai, F.; Boison, D.; Luan, G.; Li, T. Genetic variations of adenosine kinase as predictable biomarkers of efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation in patients with pharmacoresistant epilepsy. J Neurosurg 2022, 136, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Xie, P.; Liu, S.; Huang, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Deng, J.; Tang, C.; Xu, K.; Zhang, B.; He, B.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Guan, Y.; Luan, G.; Li, T.; Zhai, F. Deep brain stimulation suppresses epileptic seizures in rats via inhibition of adenosine kinase and activation of adenosine A1 receptors. CNS Neurosci Ther 2023, 29, 2597–2607. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Li, T. Adenosine Dysfunction in Epilepsy and Associated Comorbidities. Curr Drug Targets 2022, 23, 344–357. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; He, X.; Li, T. Adenosine Kinase, a Common Pathologic Biomarker for Human Pharmacoresistant Epilepsy. Neuropsychiatry 2018, 08. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, X.A.; Singh, B.; Park, J.; Gupta, R.S. Subcellular localization of adenosine kinase in mammalian cells: The long isoform of AdK is localized in the nucleus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2009, 388, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Peter-Okaka, U.; Boison, D. Adenosine Kinase: An Epigenetic Modulator and Drug Target. J Inherit Metab Dis 2025, 48, e70033. [Google Scholar]

- Murugan, M.; Fedele, D.; Millner, D.; Alharfoush, E.; Vegunta, G.; Boison, D. Adenosine kinase: An epigenetic modulator in development and disease. Neurochem Int 2021, 147, 105054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murugan, M.; Boison, D. Adenosine Kinase: Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Isoforms. In Jasper's Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, 2024; p. 555-568 555-68. [Google Scholar]

- Boison, D. Adenosinergic signaling in epilepsy. Neuropharmacology 2016, 104, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boison, D.; Chen, J.F.; Fredholm, B.B. Adenosine signaling and function in glial cells. Cell Death Differ 2010, 17, 1071–1082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fredholm, B.B.; Chen, J.F.; Cunha, R.A.; Svenningsson, P.; Vaugeois, J.M. Adenosine and brain function. Int Rev Neurobiol 2005, 63, 191–270. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, M.; Augusto, E.; Agostinho, P.; Cunha, R.A.; Chen, J.F. Antagonistic interaction between adenosine A2A receptors and Na+/K+-ATPase-alpha2 controlling glutamate uptake in astrocytes. J Neurosci 2013, 33, 18492–18502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Ribeiro-Rodrigues, L.; Ruffolo, G.; Alfano, V.; Domingos, C.; Rei, N.; Tosh, D.K.; Rombo, D.M.; Morais, T.P.; Valente, C.A.; Xapelli, S.; Bordadagua, B.; Rainha-Campos, A.; Bentes, C.; Aronica, E.; Diogenes, M.J.; Vaz, S.H.; Ribeiro, J.A.; Palma, E.; Jacobson, K.A.; Sebastiao, A.M. Selective modulation of epileptic tissue by an adenosine A(3) receptor-activating drug. Br J Pharmacol 2024, 181, 5041–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Chen, F.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Q.; Guan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Zhai, F.; Boison, D.; Luan, G.; Li, T. Upregulation of adenosine A2A receptor and downregulation of GLT1 is associated with neuronal cell death in Rasmussen's encephalitis. Brain Pathol 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Steinbeck, J.A.; Lusardi, T.; Koch, P.; Lan, J.Q.; Wilz, A.; Segschneider, M.; Simon, R.P.; Brustle, O.; Boison, D. Suppression of kindling epileptogenesis by adenosine releasing stem cell-derived brain implants. Brain 2007, 130 Pt 5, 1276–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masino, S.A.; Li, T.; Theofilas, P.; Sandau, U.S.; Ruskin, D.N.; Fredholm, B.B.; Geiger, J.D.; Aronica, E.; Boison, D. A ketogenic diet suppresses seizures in mice through adenosine A(1) receptors. J Clin Invest 2011, 121, 2679–2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z.; Deng, J.; Xie, P.; Tang, C.; Wang, J.; Deng, Q.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Guo, M.; Wang, X.; Guan, Y.; Luan, G.; Zhou, J.; Li, T. Deep Brain Stimulation Inhibits Epileptic Seizures via Increase of Adenosine Release and Inhibition of ENT1, CD39, and CD73 Expression. Mol Neurobiol 2025, 62, 1800–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilz, A.; Pritchard, E.M.; Li, T.; Lan, J.Q.; Kaplan, D.L.; Boison, D. Silk polymer-based adenosine release: therapeutic potential for epilepsy. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 3609–3616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams-Karnesky, R.L.; Sandau, U.S.; Lusardi, T.A.; Lytle, N.K.; Farrell, J.M.; Pritchard, E.M.; Kaplan, D.L.; Boison, D. Epigenetic changes induced by adenosine augmentation therapy prevent epileptogenesis. J Clin Invest 2013, 123, 3552–3563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, T. Role of Adenosine Kinase Inhibitor in Adenosine Augmentation Therapy for Epilepsy: A potential novel drug for epilepsy. Curr Drug Targets 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Xie, P.; Liu, S.; Luan, G.; Li, T. Epilepsy and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): The Underlying Mechanisms and Therapy Targets Related to Adenosine. Curr Neuropharmacol 2023, 21, 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, F.; He, X.; Luan, G.; Li, T. Role of DNA Methylation and Adenosine in Ketogenic Diet for Pharmacoresistant Epilepsy: Focus on Epileptogenesis and Associated Comorbidities. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 119. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boison, D. Adenosine augmentation therapies (AATs) for epilepsy: prospect of cell and gene therapies. Epilepsy Res 2009, 85, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredholm, B.B.; IJzerman, A.P.; Jacobson, K.A.; Linden, J.; Muller, C.E. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors-an update. Pharmacol Rev 2011, 63, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Reppert, S.M.; Weaver, D.R.; Stehle, J.H.; Rivkees, S.A. Molecular cloning and characterization of a rat A1-adenosine receptor that is widely expressed in brain and spinal cord. Mol Endocrinol 1991, 5, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardas, J. Neuroprotective role of adenosine in the CNS. Pol J Pharmacol 2002, 54, 313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Fedele, D.E.; Li, T.; Lan, J.Q.; Fredholm, B.B.; Boison, D. Adenosine A1 receptors are crucial in keeping an epileptic focus localized. Exp Neurol 2006, 200, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glass, M.; Faull, R.L.; Bullock, J.Y.; Jansen, K.; Mee, E.W.; Walker, E.B.; Synek, B.J.; Dragunow, M. Loss of A1 adenosine receptors in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res 1996, 710, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaft, Z.J.; Hollnagel, J.O.; Salar, S.; Caliskan, G.; Schulz, S.B.; Schneider, U.C.; Horn, P.; Koch, A.; Holtkamp, M.; Gabriel, S.; Gerevich, Z.; Heinemann, U. Adenosine A1 receptor-mediated suppression of carbamazepine-resistant seizure-like events in human neocortical slices. Epilepsia 2016, 57, 746–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A.K.; Miller, M.A.; Scanlon, J.; Ren, D.; Kochanek, P.M.; Conley, Y.P. Adenosine A1 receptor gene variants associated with post-traumatic seizures after severe TBI. Epilepsy Res 2010, 90, 259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Hack, S.P.; Christie, M.J. Adaptations in adenosine signaling in drug dependence: therapeutic implications. Crit Rev Neurobiol 2003, 15, 235–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.V.; Kaster, M.P.; Tome, A.R.; Agostinho, P.M.; Cunha, R.A. Adenosine receptors and brain diseases: neuroprotection and neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta 2011, 1808, 1380–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, J.; Jakova, E.; Cayabyab, F.S. Adenosine A1 and A2A Receptors in the Brain: Current Research and Their Role in Neurodegeneration. Molecules 2017, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros-Barbosa, A.R.; Ferreirinha, F.; Oliveira, A.; Mendes, M.; Lobo, M.G.; Santos, A.; Rangel, R.; Pelletier, J.; Sevigny, J.; Cordeiro, J.M.; Correia-de-Sa, P. Adenosine A(2A) receptor and ecto-5'-nucleotidase/CD73 are upregulated in hippocampal astrocytes of human patients with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (MTLE). Purinergic Signal 2016, 12, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Takahashi, K.; Schulte, D.; Stouffer, N.; Lin, Y.; Lin, C.L. Increased glial glutamate transporter EAAT2 expression reduces epileptogenic processes following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Neurobiol Dis 2012, 47, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, M.; Augusto, E.; Santos-Rodrigues, A.D.; Schwarzschild, M.A.; Chen, J.F.; Cunha, R.A.; Agostinho, P. Adenosine A2A receptors modulate glutamate uptake in cultured astrocytes and gliosomes. Glia 2012, 60, 702–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canas, P.M.; Porciuncula, L.O.; Simoes, A.P.; Augusto, E.; Silva, H.B.; Machado, N.J.; Goncalves, N.; Alfaro, T.M.; Goncalves, F.Q.; Araujo, I.M.; Real, J.I.; Coelho, J.E.; Andrade, G.M.; Almeida, R.D.; Chen, J.F.; Kofalvi, A.; Agostinho, P.; Cunha, R.A. Neuronal Adenosine A2A Receptors Are Critical Mediators of Neurodegeneration Triggered by Convulsions. eNeuro 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Yacoubi, M.; Ledent, C.; Parmentier, M.; Daoust, M.; Costentin, J.; Vaugeois, J. Absence of the adenosine A(2A) receptor or its chronic blockade decrease ethanol withdrawal-induced seizures in mice. Neuropharmacology 2001, 40, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Alimonte, I.; D'Auro, M.; Citraro, R.; Biagioni, F.; Jiang, S.; Nargi, E.; Buccella, S.; Di Iorio, P.; Giuliani, P.; Ballerini, P.; Caciagli, F.; Russo, E.; De Sarro, G.; Ciccarelli, R. Altered distribution and function of A2A adenosine receptors in the brain of WAG/Rij rats with genetic absence epilepsy, before and after appearance of the disease. Eur J Neurosci 2009, 30, 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alves, M.; Gerbatin, R.; Kalmeijer, R.; Fedele, D.; Engel, T.; Boison, D. Adenosine A(2A) receptor and glial glutamate transporter GLT-1 are synergistic targets to reduce brain hyperexcitability after traumatic brain injury in mice. Neuropharmacology 2025, 278, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tescarollo, F.C.; Rombo, D.M.; DeLiberto, L.K.; Fedele, D.E.; Alharfoush, E.; Tome, A.R.; Cunha, R.A.; Sebastiao, A.M.; Boison, D. Role of Adenosine in Epilepsy and Seizures. J Caffeine Adenosine Res 2020, 10, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, L.V.; Rebola, N.; Pinheiro, P.C.; Richardson, P.J.; Oliveira, C.R.; Cunha, R.A. Adenosine A3 receptors are located in neurons of the rat hippocampus. Neuroreport 2003, 14, 1645–1648. [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund, O.; Shang, M.; Tonazzini, I.; Dare, E.; Fredholm, B.B. Adenosine A1 and A3 receptors protect astrocytes from hypoxic damage. Eur J Pharmacol 2008, 596, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hammarberg, C.; Schulte, G.; Fredholm, B.B. Evidence for functional adenosine A3 receptors in microglia cells. J Neurochem 2003, 86, 1051–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Tosh, D.K.; Paoletta, S.; Deflorian, F.; Phan, K.; Moss, S.M.; Gao, Z.G.; Jiang, X.; Jacobson, K.A. Structural sweet spot for A1 adenosine receptor activation by truncated (N)-methanocarba nucleosides: receptor docking and potent anticonvulsant activity. J Med Chem 2012, 55, 8075–8090. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Spanoghe, J.; Larsen, L.E.; Craey, E.; Manzella, S.; Van Dycke, A.; Boon, P.; Raedt, R. The Signaling Pathways Involved in the Anticonvulsive Effects of the Adenosine A(1) Receptor. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Boison, D. Adenosine and seizure termination: endogenous mechanisms. Epilepsy Curr 2013, 13, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, O.; Casper, K.B.; Kubera, C.; Zhang, J.; Revilla-Sanchez, R.; Sul, J.Y.; Takano, H.; Moss, S.J.; McCarthy, K.; Haydon, P.G. Astrocytic purinergic signaling coordinates synaptic networks. Science 2005, 310, 113–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Kang, N.; Lovatt, D.; Torres, A.; Zhao, Z.; Lin, J.; Nedergaard, M. Connexin 43 hemichannels are permeable to ATP. J Neurosci 2008, 28, 4702–4711. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2000, 362, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Young, J.D.; Yao, S.Y.; Baldwin, J.M.; Cass, C.E.; Baldwin, S.A. The human concentrative and equilibrative nucleoside transporter families, SLC28 and SLC29. Mol Aspects Med 2013, 34, 529–547. [Google Scholar]

- Headrick, J.P.; Willis, R.J. 5'-Nucleotidase activity and adenosine formation in stimulated, hypoxic and underperfused rat heart. Biochem J 1989, 261, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, H.G.; Deussen, A.; Wuppermann, H.; Schrader, J. The transmethylation pathway as a source for adenosine in the isolated guinea-pig heart. Biochem J 1988, 252, 489–494. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, D.R.; Cornatzer, W.E.; Duerre, J.A. Relationship between tissue levels of S-adenosylmethionine, S-adenylhomocysteine, and transmethylation reactions. Can J Biochem 1979, 57, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Boison, D.; Scheurer, L.; Zumsteg, V.; Rulicke, T.; Litynski, P.; Fowler, B.; Brandner, S.; Mohler, H. Neonatal hepatic steatosis by disruption of the adenosine kinase gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002, 99, 6985–6990. [Google Scholar]

- Kobow, K.; Kaspi, A.; Harikrishnan, K.N.; Kiese, K.; Ziemann, M.; Khurana, I.; Fritzsche, I.; Hauke, J.; Hahnen, E.; Coras, R.; Muhlebner, A.; El-Osta, A.; Blumcke, I. Deep sequencing reveals increased DNA methylation in chronic rat epilepsy. Acta Neuropathol 2013, 126, 741–756. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Delaney, S.F.; Bryan, K.; Das, S.; McKiernan, R.C.; Bray, I.M.; Reynolds, J.P.; Gwinn, R.; Stallings, R.L.; Henshall, D.C. Differential DNA methylation profiles of coding and non-coding genes define hippocampal sclerosis in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain 2015, 138 Pt 3, 616–631. [Google Scholar]

- Kobow, K.; Ziemann, M.; Kaipananickal, H.; Khurana, I.; Muhlebner, A.; Feucht, M.; Hainfellner, J.A.; Czech, T.; Aronica, E.; Pieper, T.; Holthausen, H.; Kudernatsch, M.; Hamer, H.; Kasper, B.S.; Rossler, K.; Conti, V.; Guerrini, R.; Coras, R.; Blumcke, I.; El-Osta, A.; Kaspi, A. Genomic DNA methylation distinguishes subtypes of human focal cortical dysplasia. Epilepsia 2019, 60, 1091–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Z.; Zhang, J.; Deng, Q.; Wang, M.; Li, T. Vagus Nerve Stimulation Inhibits DNA and RNA Methylation in a Rat Model of Pilocarpine-Induced Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. CNS Neurosci Ther 2025, 31, e70484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- During, M.J.; Spencer, D.D. Adenosine: a potential mediator of seizure arrest and postictal refractoriness. Ann Neurol 1992, 32, 618–624. [Google Scholar]

- Theofilas, P.; Brar, S.; Stewart, K.A.; Shen, H.Y.; Sandau, U.S.; Poulsen, D.; Boison, D. Adenosine kinase as a target for therapeutic antisense strategies in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2011, 52, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, G.; Wang, X.; Chen, F.; Gao, Q.; Zhou, J.; Guan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhai, F.; Chen, Y.; Li, T. Overexpression of Adenosine Kinase in Patients with Epilepsy Associated With Sturge-Weber Syndrome. Neuropsychiatry 2018, 08. [Google Scholar]

- de Groot, M.; Iyer, A.; Zurolo, E.; Anink, J.; Heimans, J.J.; Boison, D.; Reijneveld, J.C.; Aronica, E. Overexpression of ADK in human astrocytic tumors and peritumoral tissue is related to tumor-associated epilepsy. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Gimenes, C.; Motta Pollo, M.L.; Diaz, E.; Hargreaves, E.L.; Boison, D.; Covolan, L. Deep brain stimulation of the anterior thalamus attenuates PTZ kindling with concomitant reduction of adenosine kinase expression in rats. Brain Stimul 2022, 15, 892–901. [Google Scholar]

- Miranda, M.F.; Hamani, C.; de Almeida, A.C.; Amorim, B.O.; Macedo, C.E.; Fernandes, M.J.; Nobrega, J.N.; Aarao, M.C.; Madureira, A.P.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Andersen, M.L.; Tufik, S.; Mello, L.E.; Covolan, L. Role of adenosine in the antiepileptic effects of deep brain stimulation. Front Cell Neurosci 2014, 8, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.A.; Mehler, M.F. Epigenetic mechanisms underlying human epileptic disorders and the process of epileptogenesis. Neurobiol Dis 2010, 39, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Younus, I.; Reddy, D.S. Epigenetic interventions for epileptogenesis: A new frontier for curing epilepsy. Pharmacol Ther 2017, 177, 108–122. [Google Scholar]

- Kobow, K.; Blumcke, I. The emerging role of DNA methylation in epileptogenesis. Epilepsia 2012, 53 (Suppl. 9), 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahba, A.E.; Fedele, D.; Gebril, H.; AlHarfoush, E.; Toti, K.S.; Jacobson, K.A.; Boison, D. Adenosine Kinase Expression Determines DNA Methylation in Cancer Cell Lines. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci 2021, 4, 680–686. [Google Scholar]

- Toti, K.S.; Osborne, D.; Ciancetta, A.; Boison, D.; Jacobson, K.A. South (S)- and North (N)-Methanocarba-7-Deazaadenosine Analogues as Inhibitors of Human Adenosine Kinase. J Med Chem 2016, 59, 6860–6877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, T.A.; Akula, K.K.; Coffman, S.Q.; Ruskin, D.N.; Masino, S.A.; Boison, D. Ketogenic diet prevents epileptogenesis and disease progression in adult mice and rats. Neuropharmacology 2015, 99, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; He, X.; Luan, G.; Li, T. Role of DNA Methylation and Adenosine in Ketogenic Diet for Pharmacoresistant Epilepsy: Focus on Epileptogenesis and Associated Comorbidities. Front Neurol 2019, 10, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Taub, K.S.; Kessler, S.K.; Bergqvist, A.G. Risk of seizure recurrence after achieving initial seizure freedom on the ketogenic diet. Epilepsia 2014, 55, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeler, N.E.; Ridout, D.; Neal, E.G.; Becirovic, M.; Whiteley, V.J.; Meskell, R.; Lightfoot, K.; Mills, N.; Ives, T.; Bara, V.; Cameron, E.; Thomas, P.; Wilford, E.; Fox, R.; Fabe, J.; Leong, J.Y.; Tan-Smith, C. Maintenance of response to ketogenic diet therapy for drug-resistant epilepsy post diet discontinuation: A multi-centre case note review. Seizure 2024, 121, 78–84. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, R.E.; Rodgers, S.D.; Bassani, L.; Morsi, A.; Geller, E.B.; Carlson, C.; Devinsky, O.; Doyle, W.K. Vagus nerve stimulation for children with treatment-resistant epilepsy: a consecutive series of 141 cases. J Neurosurg Pediatr 2011, 7, 491–500. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, L.; Jaafar, F.; Kapoor, A.; Abdelmoity, L.; Madkoor, A.; Kaufman, C.; Abdelmoity, A. Transforming pediatric epilepsy care: Real-world insights from a leading single-center study on vagus nerve treatment outcomes. Epilepsia 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Guardiola, A.; Martinez, A.; Valdes-Cruz, A.; Magdaleno-Madrigal, V.M.; Martinez, D.; Fernandez-Mas, R. Vagus nerve prolonged stimulation in cats: effects on epileptogenesis (amygdala electrical kindling): behavioral and electrographic changes. Epilepsia 1999, 40, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekar, L.; Libionka, W.; Tian, G.F.; Xu, Q.; Torres, A.; Wang, X.; Lovatt, D.; Williams, E.; Takano, T.; Schnermann, J.; Bakos, R.; Nedergaard, M. Adenosine is crucial for deep brain stimulation-mediated attenuation of tremor. Nat Med 2008, 14, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).