1. Introduction

Stroke remains a major global health challenge, representing the second leading cause of death worldwide [

1,

2]. In 2019, it accounted for approximately 11.6% of all deaths. Ischemic stroke, which results from a temporary or permanent interruption of blood flow to the brain, is the most common type, responsible for about 62.4% of all stroke cases [

3]. This condition often leads to significant neurological damage, contributing to long-term disability and placing a substantial burden on healthcare systems and economies [

4]. Although the primary therapeutic goal of ischemic stroke management is rapid restoration of the cerebral blood flow through thrombolytics, recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA) is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug for acute ischemic stroke [

5]. Notably, rt-PA has limited success not only due to its narrow therapeutic window when it must be administered < 4.5 h from stroke onset but also because it is not recommended for patients older than 80 years with comorbidities [

6,

7]. Accordingly, further investigation into the pathways involved in stroke-induced neurodegeneration could lead to the development of neuroprotective drugs as adjunctive therapy with rt-PA.

Recently, neuroprotection has been introduced as an alternative pharmacological approach for the treatment of stroke, which helps to extend the therapeutic window thereby reducing neuronal loss and cognitive dysfunction [

8]. However, most neuroprotective agents, including glutamate antagonists, antioxidants, immunosuppressants, sodium channel blockers and calcium channel blockers have failed in clinical trials, showing little or no significant improvement [

9,

10] despite demonstrating efficacy as neuroprotective agents in animal stroke models [

11,

12].

Glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter that mediates synaptic transmission and many physiological processes, including long-term potentiation (LTP), through its action on two classes of glutamate receptors: G-protein coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) and ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) including N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionate receptors (AMPARs), and kainate receptors (KAR) [

13]. Glutamate receptors are implicated in numerous neurodegenerative neurological conditions, including stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, epilepsy and anxiety [

14]. However, excessive release of glutamate during ischemia or hypoxic conditions mediates a phenomenon known as glutamate excitotoxicity [

15] linked to neurodegeneration in stroke [

16,

17] and other neurological diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease [

18] and Parkinson’s disease [

19]. Ischemic stroke results in a rapid increase of extracellular glutamate in brain reaching toxic concentrations of 100 µM-10 mM and 30-50 µM in ischemic core and ischemic penumbra, respectively [

16,

17,

20]. Numerous studies from animal stroke models have shown neuroprotection achieved by administration of AMPAR antagonists, such as NBQX [

21], YM872 [

22] and talampanel (GYKI-53405) [

23]; however, these compounds have failed in clinical trials due to poor water solubility, low bioavailability or nephrotoxicity [

24,

25].

Ischemia also causes extracellular adenosine elevation of up to 100-fold as a result of extracellular ATP breakdown by extracellular nucleotidases and adenosine extrusion through equilibrative nucleoside transporters of ischemic cells [

26,

27]. Traditionally, the inhibitory adenosine A1 receptors (A1Rs) are believed to be neuroprotective by preventing excitotoxicity via inhibition of presynaptic glutamate release and reduction of postsynaptic membrane excitability [

28,

29,

30]. In contrast, the excitatory adenosine A2A receptors (A2ARs) increase the excitotoxicity and neuronal death as A2AR stimulation enhances glutamatergic synaptic transmission [

28,

31]. However, the neuroprotective effect of A1R is short-lived because of the chronic A1R stimulation and subsequent A1R desensitization accompanying the elevated extracellular adenosine [

28]. More recently we demonstrated that chronic A1R stimulation by daily intraperitoneal injections of an A1R-selective agonist caused neurodegeneration in the hippocampus and substantia nigra, brain regions where A1R and A2AR are highly expressed [

32]. We also previously reported that ischemic stroke, induced by focal cortical pial vessel disruption (PVD) representing a small vessel stroke model, dramatically reduced A1R surface expression but upregulated A2AR surface expression [

29]. Thus, studies in our lab focused on exploring the neuroprotective targets in cerebral ischemia through neuromodulation of adenosine signaling and glutamate excitotoxicity either through antagonism of A2AR or AMPAR. Moreover, the ischemic lesion caused clathrin-mediated internalization of both GluA1 and GluA2 subunits of AMPARs through A1R- dependent mechanism [

29]. Recently, we showed that prolonged A1R stimulation during hypoxic/reperfusion injury model caused upregulation of calcium-permeable AMPARs, synaptic potentiation and hippocampal neuronal damage resulting from signaling crosstalk between A1R and A2AR [

31]; thus, blocking AMPARs can be a potential target to prevent cerebral ischemia-induced neurodegeneration. More recently, we demonstrated that istradefylline, a selective adenosine A2AR antagonist approved by the FDA as an adjunctive treatment for Parkinson’s disease, effectively prevented hippocampal neuronal cell death and attenuated astrocyte- and microglia-mediated neuroinflammation following cerebral ischemia in rats. Moreover, istradefylline ameliorated cognitive impairment and motor deficits in a small-vessel ischemic stroke model [

33]. The present study aimed to investigate the hypothesis that antagonism of AMPA receptors would mitigate neurodegeneration after cerebral ischemia.

Apart from the crucial role of AMPARs in synaptic plasticity and synaptic transmission, the AMPA receptors of microglia and macrophages contribute to the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines upon activation [

34,

35]. Moreover, AMPA receptors are expressed in inflammatory/immune cells, where they have a role in proliferation, cell adhesion, chemotaxis, and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and nitric oxide from inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [

36,

37]. In this study, we explored the role of AMPA receptor antagonist in attenuating the elevated pro-inflammatory factors and restoring the levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines following cerebral ischemia.

Perampanel (Fycompa®), a non-competitive AMPAR antagonist, has been approved by FDA for anti-seizure treatment [

38,

39,

40,

41]. We have recently shown that perampanel exhibited neuroprotection and prevented the adenosine-induced synaptic potentiation observed after normoxic reperfusion following a 20 min hypoxic insult [

31]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the clinically approved anti-epileptic perampanel may show efficacy as a neuroprotective agent in an in vivo cerebral ischemia stroke model. Results of the current study suggest that perampanel could be repurposed as a neuroprotective therapy to attenuate the cognitive, mood, and motor dysfunction, prevent LTP deficits, and reduce neurodegeneration in our preclinical ischemic/non-reperfusion stroke model.

2. Materials and Methods

Animal Subjects

This work was approved by the University of Saskatchewan’s Animal Research Ethics Board and complied with the Canadian Council on Animal Care guidelines for humane animal use (Approved Animal Use Protocol Number: 20070090). All experimental design, analysis and reported number of research animals used also adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animal use to ensure all efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used in this study [

42]. Male Sprague-Dawley rats at 20-30 days old (Charles River Canada, Montreal, Canada) were used in all studies. After arrival, the animals were kept for at least 1 week for handling before being used in any procedure. Rats were housed two per cage in standard polypropylene cages in a temperature controlled (21 °C) colony room on a 12/12-h light/dark cycle. Experimental procedures were carried out during the light phase. Rats were randomly divided into three groups (n=15 in each group) based on surgery described below and received treatments. The first group represented the control group (

Sham), while both the other two groups were subjected to PVD surgery (group 2: PVD/vehicle control referred to in graphs as

PVD and treatment group 3: PVD/ Perampanel referred to as

PER). The experimental design, surgical procedures, and behavioral assessments used in this study were conducted as previously described in our recent publication [

33], with minor modifications where indicated.

Hippocampal Slice Preparation

On the fourth day after PVD surgery, male Sprague Dawley rats from 3 groups (Sham, PVD + DMSO, and PVD + Perampanel) were anaesthetized with halothane and rapidly decapitated, with the brains immediately excised and submerged in oxygenated, ice-cold high-sucrose dissection medium containing the following: 87 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO

3, 25 mM glucose, 75 mM sucrose, 2.5 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH

2PO

4, 7.0 mM MgCl

2, and 500 μM CaCl

2 [

43]. Hippocampal slices from both ipsilateral and contralateral side of lesion, were taken at 400 μm thickness using a vibrating tissue slicer (VTS1200S, Vibram Instruments, Germany), and slicing was performed in the same ice-cold oxygenated dissection medium as above. Slices were maintained for at least 1h at room temperature before doing any experiments in oxygenated artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing the following: 126 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM KCl, 2.0 mM MgCl

2, 1.25 mM NaH

2PO

4, 26 mM NaHCO

3, 10 mM glucose, 2.0 mM CaCl

2 [

43]. Oxygenation was accomplished by continually bubbling the solution with 95% O

2/5% CO

2.

Drug Treatments

Rats subjected to PVD surgery are injected intraperitoneally with perampanel 3mg/kg or vehicle control, 1 hr after the surgery for 3 consecutive days. Perampanel was freshly dissolved in a solvent mixture of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma, St. Louis, MO): polyethylene glycol 300 (PEG 300, Sigma, St. Louis, MO): distilled water (1:1:1; v/v/v). The PVD-treated rats with vehicle control are injected with the same solvent mixture without perampanel.

Chemically Induced Long Term Potentiation (cLTP)

Hippocampal slices were submerged in an electrophysiology recording chamber with constant perfusion of oxygenated aCSF (3ml/min). Field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were evoked by orthodromic stimulation of the Schaffer collateral pathway using a bipolar tungsten stimulating electrode (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). A pulled glass recording microelectrode filled with aCSF (resistance 1-3MΩ) was placed in CA1 stratum radiatum, which recorded fEPSPs induced by Schaffer collateral stimulation. fEPSPs were evoked for 0.1ms every 30s throughout each experiment. The fEPSP signals were amplified 1000 times with an AC amplifier, band-pass filtered at 0.1-100Hz, digitized at 10kHz using a Digidata 1440A digitizer (Axon Instruments), and saved to a computer as a Clampex 9.0 (Axon Instruments) file. The collected fEPSP data were analyzed using Clampfit 9.0 (Axon Instruments). Chemically induced long term potentiation experiment consists of three stages; 10 min baseline recording followed by 10 min cLTP and 1 h washout. Baseline recordings were set to approximately 60% of maximal fEPSP values and stable baseline was established for 10 min to ensure stable baseline before inducing cLTP. Following 10 min baseline, cLTP was induced for 10 min during which slices were perfused with Forskolin (50 µM, Tocris) and Rolipram (0.1 µM, Tocris) that are dissolved in oxygenated -Mg2+ free aCSF. Following cLTP induction, a 1 h washout period in regular (Mg2+-containing) aCSF was recorded. The fEPSP slopes were normalized to the mean of the last 10 sweeps (5 min) of the final 10 sweeps (5 min) of the baseline recording period (100%). The mean normalized fEPSP slope was plotted as a function of time with error bars representing the standard error of the mean (SEM). Sample traces are the average of 10 sweeps from a representative recording from each treatment group. All histograms show the mean normalized percent fEPSP of baseline ± SEM. Statistical significance was assessed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey-Kramer post-hoc test.

Biochemistry and Western Blotting

To isolate cell surface proteins, slices were treated with NHS-SS-Biotin (1mg/ml, Thermo Scientific) for 1h at 4°C. The biotin reaction was quenched with glycine buffer containing 192mM Glycine and 25mM Tris (pH 8.3). Slices were then transferred to homogenization tubes and homogenized in lysis buffer (pH 8.0) containing 50mM Tris, 150mM NaCl, 1mM EDTA, 1mM NaF; and the following protease inhibitors: 1 mM PMSF, 10 µg/mL aprotinin, 10 µg/mL pepstatin A, 10 µg/mL leupeptin, 2 mM Na3VO4, 20 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 3 mM benzamidine hydrochloride, and 4 mM glycerol 2-phosphate with 1% NP-40 detergent. A Bradford Assay was performed with DC Protein assay dye (Bio-Rad) to determine protein concentration in the lysates, and 500 μg of protein lysate diluted in lysis buffer was loaded into Streptavidin agarose beads (Thermo Scientific) and rotated overnight at 4°C. The beads were then washed 4-6 times the next day with lysis buffer containing same reagents as above except 0.1% NP-40. The proteins were eluted by adding 50 µl of 2X Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad) and boiling the samples at 95 °C for 5 min. Whole cell lysate samples of 50 µg were eluted in 20µl of the same Laemmli buffer and boiled for 5min. Samples were loaded into 8 % SDS-PAGE gels and run for 20 min at 80 V then voltage increased to 160 V and running continued for 1h. Proteins were transferred from gels to 0.2 µm PVDF blotting membrane (GE healthcare life sciences, 2.5 h, 0.3 mA at 4°C). Membranes were incubated with 5% fat-free milk for 1 h at room temperature to block nonspecific background then treated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C as follows: GluA1 (rabbit mAb, Millipore), GluA2 (mouse mAb, Millipore), Iba-1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA, cat # GT10312; 1:500 dilution), GFAP (Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA, cat # 16825-1-AP; 1:5000), nNOS (Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA, cat # 07-571-I; 1:1000), and iNOS (Abcam, Cambridge, UK, Cat # ab3523; 1:1000). Membranes were then probed with the corresponding HRP-conjugated secondary antibody and then ECL was performed (Biorad). The membranes were reprobed with antibodies against β-actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA, cat # sc-47778; 1:5000) or GAPDH (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, cat # sc-32233; 1:1000) to ensure loading consistency. Analysis was performed using Fiji (NIH, public domain) and data were expressed as the percentage of the intensity of target protein to that of corresponding to the loading control.

Propidium Iodide Staining

Propidium iodide (PI) is a fluorescent intercalating agent that is used effectively as marker for cell death and evaluation of cell viability since PI cannot cross cell membrane of intact healthy cells while only enters and labels cells with disrupted plasma membranes and produces strong red fluorescence when excited by green light. Propidium iodide staining, and subsequent confocal imaging of rat hippocampal slices were used to examine the effect of perampanel administration on cell survival after ischemic stroke induced by PVD surgery. The methods used were adapted from previous literature [

30,

31,

44,

45]. Following equilibration of hippocampal slices for 1h after slicing as described above, slices were incubated in fresh oxygenated aCSF at room temperature for 2h. Then, 5μg/ml propidium iodide (Sigma) was added to the aCSF and slices were incubated for 1 hr. Following the incubation period, slices were rinsed thoroughly in aCSF and then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4

°C overnight. The following day, slices were washed 3 x 15min in 1X PBS and then mounted on glass microscope slides (VWR) and sealed using Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen). After the addition of PI, all subsequent procedures were performed in the dark to prevent photobleaching.

Hippocampal slices were imaged using a Zeiss LSM700 laser scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Germany) using green light (543 nm) to induce PI fluorescence. The whole hippocampus was imaged in pieces using a 10X objective lens, and images of CA1 pyramidal neurons were obtained using the Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 63X/1.6 oil objective lens (Carl Zeiss). CA1 images were acquired as Z-stack images of 200μm depth into the hippocampal slice with each Z-stack image taken at 2μm. Two Z-stack images were taken along CA1 for each slice and were averaged using densitometry analysis. Data was collected using Zeiss Zen 2009 version 5.5 software (Carl Zeiss) and was analyzed using ImageJ. Z-stack images closest to the outer top and bottom of the hippocampal slices were not analyzed, as the neuronal damage in those areas was enhanced by the slicing procedure. The inner-most 20μm (~100μm into the slice) segments were combined as maximum intensity projections and intensities were compared between treatment groups using densitometry analysis. Collected densitometry data was normalized to representative hippocampal slice from sham group. Data was graphed as a percentage of sham value and analyzed for significance against this control value (100%). Full hippocampal images were assembled as montages of the entire hippocampal slice using Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

FluoroJade-C Staining

FluoroJade-C (FJC) is a polyanionic fluorescein derivative that can be used as a sensitive and selective marker to degenerating neurons. Consequently, we used FJC to quantify level of neurodegeneration in hippocampus after inducing ischemic stroke. On the fourth day after PVD surgery, rat brains were obtained and sectioned as described previously [

46]. In brief, anesthetized rats were intracardially perfused with 4% PFA in PBS for 30 min. After perfusion, brains were removed and fixed with 4% PFA in PBS overnight. Brains were then stored in 30% sucrose (w/v) in 0.1 M PBS for an additional 3 days to ensure cryoprotection before slicing. The brains were then frozen in liquid nitrogen in Tissue-Tek OCT mounting medium, and 40 µm coronal sections of hippocampus were cut with cryostat.

To visualize degenerative neurons, brain sections were mounted on gelatin-coated slides, air-dried on slide warmer at 45°C for 20 min., and subjected to FJC staining. The slides were first immersed in a solution containing 1% NaOH in 80% ethanol for 5 min followed by 2 min rinses in 70% ethanol, then in distilled water. Brain slices were then incubated in 0.06% freshly prepared potassium permanganate solution for 10 min. Following a 2 min rinse in distilled water, slides were transferred to the 0.0001% FJC staining solution and stained for 10 min on mechanical shaker to ensure uniform staining of slices. The proper dilution was accomplished by first making a 0.01% stock solution of FJC dye (Millipore) in distilled water and then adding 1 ml of the stock solution to 99 ml of 0.1% acetic acid. The working diluted solution of FJC was used within 2 h of preparation, while the stock solution was stored at -20 °C and used within three months [

46]. Slides were washed three times each for 1 min in distilled water and then air-dried on a slide warmer at 50°C for 30 min. Then, slides were rinsed in xylene, and coverslips were mounted using Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen). Digital images were obtained with Zeiss LSM 700 (Carl Zeiss) using a 10X objective for the hippocampal montages and 63X/1.4 oil-immersion objective lens for the magnified regions of the hippocampal pyramidal body layers. Two Z-stack images of CA1 region (taken at 1μm interval) were averaged using similar densitometry analysis performed with the PI analysis above. Collected densitometry data was normalized to representative hippocampal slice from sham group. Data was graphed as a percentage of sham value and analyzed for significance against this control value (100%). Full hippocampal images were assembled as montages of the entire hippocampal slice using Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

Pial Vessel Disruption as a Model of Small-Vessel Stroke

Disruption of class II size vessels on the surface of the cortex (pia), known as pial vessel disruption (PVD), has been shown to induce a small focal cortical lesion, which within 3 weeks forms a lacuna-like fluid-filled cyst surrounded by a barrier rich with reactive astrocytes [

46,

47,

48]. PVD stroke model induces an approximately 1mm

3 permanent, non-reperfusion lesion which is confined to the cortex and does not extend into the underlying corpus callosum [

47,

49]. PVD surgery which is described briefly below, has been modified by our lab and extensively studied as a small vessel in vivo animal stroke model since it has several advantages over other stroke models [

29,

46]. For instance, this PVD model is a non-perfusion small-vessel stroke model that produces permanent damage to Class II size vessels, and the cortical lesion volumes of approximately 1mm

3 can be reliably reproduced and closely resemble a lacunar infarction [

47,

49]. On the contrary, most of the focal or global animal stroke models used by other groups are ischemic/reperfusion models that involve transient occlusion of large vessels, such as middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) model [

50,

51] and the cerebral ischemic damage often encompasses large volumes of brain regions.

PVD surgery is described briefly as below; male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing approximately 250 g received 2% isoflurane for induction of anesthesia and then hair of the skull was shaved. Rats were kept immobile by transferring to a stereotaxic frame with a temperature-controlled heating pad connected to a rectal thermoprobe to monitor and maintain the body temperature throughout the surgery at 37 °C. Anesthesia was maintained by 2% isoflurane delivered through stereotaxic frame throughout the surgery and then rats were subcutaneously injected Buprenorphine (0.035 mg/kg) for pain management. A craniotomy was performed with a 5-mm-diameter trephine positioned on the right and rostral side of the bregma adjacent to the coronal and sagittal sutures. Cool sterile saline was applied intermittently to prevent overheating from the high-speed drilling. After removal of the dura and exposing the cortical surface and the overlying pial vessels, medium-sized (class II) pial vessels were disrupted by fine-tipped forceps. The piece of bone was placed back, and the scalp was then closed with a wound clip. Sham animals received the same treatment with dura removal but no vessel disruption. Animals were kept in a cage separately under a warm lamp during the recovery from anesthesia and thereafter, the animals were returned to their cages. As illustrated in our recent publication [

33], rats were euthanized at the fourth day after surgery for postmortem analysis either by intracardiac perfusion (for FJC staining/confocal imaging studies) or by deep anesthesia using halothane followed by decapitation for slicing hippocampus for electrophysiology studies or biotinylation as described above.

Y-Maze

Rats were transported to the behavior room at least 1 hr before starting any behavior tasks to allow acclimatization. Y-maze apparatus consists of three arms that are joined by a triangle-shaped center to form a “Y” shape. Each arm has a rectangular base that is 45 x 12 cm, and all areas of the maze are surrounded by 35 cm tall walls. The task consisted of two trials separated by a 90 min interval. In the first trial (acquisition), one of the three arms was blocked (novel arm), then rats were placed in the maze facing the end of a randomly chosen arm (start arm). The trial was 15 minutes long during which rats were free to explore the start arm and the old arm, but not the novel arm of the maze. After the first trial, rats were placed back in their cages for a 90-minute break. In the second trial (retrieval), rats were placed in the maze for 5 minutes and free to explore all arms including the novel arm that was blocked in the first trial. For both trials, there were visual spatial cues on the walls outside the maze for rats to easily view throughout their exploration periods. A video camera was used to record both trials. The video-tracking software, EthoVisionXT (Noldus) was used in a single blinded way to automatically score time spent in each arm in seconds (s). These scores were determined for the second 5-minute retrieval trial. Time spent in each of the three arms were calculated as a percentage of the total trial time.

Open Field Test

The open-field test apparatus is a 56 x 56 cm square-shaped field surrounded 57 cm tall walls. The bright light that shines directly above the maze causes the 280 x 280 cm center square to be the brightest and most exposed area of the field. Rats were initially placed in this center square and free to explore the entirety of the field for 15 minutes. A video camera was used to record their behavior. Since rodents have the tendency to explore mainly the peripheral areas when placed in open field, a phenomenon called thigmotaxis, thus open field test has been used as a validated behavioral test to assess the degree of anxiety that is directly related to the level of thigmotaxis exhibited by the rats in the open field [

52,

53]. EthoVisionXT (Noldus) was used to automatically score the following: center square entries and center square duration (s). Furthermore, heat maps for both Y maze and Open field tasks were obtained by EthoVisionXT (Noldus).

Forced Swim Test (FST)

The forced swim test (FST) is a behavioral test that measures depressive symptoms such as despair and learned helplessness. When rodents are first placed in water, they are expected to swim as vigorously as possible to escape this stressful situation [

54]. However, as time passes, the animal reaches a point of helplessness and despair, which is reflected by immobility [

54]. The FST was used to assess depressive-like behavior of rats following PVD surgery and evaluate the potential of perampanel to restore their mobility. The FST apparatus is a 30 x 30 x 60 cm rectangle-shaped acrylic glass container that is two-thirds filled with water of 25°C [

54]. Rats were placed in the container for 10 minutes, during which their behavior was recorded by a video camera. The FST was the last of behavioral tests conducted on the third experimental day to prevent its stressor from affecting the other conducted behavioral tests.

The video files were uploaded to EthoVisionXT (Noldus), which automatically scored for two activity statuses throughout the test. The highly active and inactive statuses were separated by threshold of 0.15% of the total activity, then percentage of time spent immobile of the 10 minutes trial and the latency of immobility were calculated. Rats were scored also for both success and vigor as a function of continuous movement of 4 limbs and swimming with head above water, respectively [

55]. Criteria for success scores were as follows: 3, continuous movement of all four limbs; 2.5, occasional floating; 2, floating more than swimming; 1.5, occasional swimming using all four limbs; 1, occasional swimming using only hind limbs; 0, no use of limbs. Criteria for vigor scores were as follows: 3, entire head above water; 2.5, ears but not eyes are usually below water; 2, eyes but not nose are usually below water; 1.5, entire head below water for three seconds; 1, entire head below water for periods ≥ six seconds; 0, animal on the bottom of the tank for periods of ten seconds or longer. Trials were stopped and excluded if rats spent more than 20 seconds swimming at the bottom of the tank. A sum of scores for the last three minutes of the test was used to evaluate the immobility of rats undergoing different treatments. The treatment groups were double blinded during the experiment and analysis.

Rotarod

The rotarod test was performed according to the method of Deacon [

56] to assess for motor coordination and post-stroke motor deficits, with slight modification. The four chambered rotarod (Powermax II, 1.8° Step motor, Economex enclosure model) from Columbus Instruments, Ohio, USA, was used for the experiment. Rats were placed in the behavioral room 30 min prior to experimentation, for habituation. Rats were pre-trained in the rotarod for 2 days before induction (two trials each day) and then tested 72 h following PVD surgery. Rats were placed on the rod, one in each chamber facing away from the direction of rotation and then the rotation was started with an accelerated rate of 5 rpm/sec. The latency time of falling from the rod was recorded. The test was repeated three times and the mean value for each animal was calculated. The maximum time and speed of the rotation were set as 120 s and 50 rpm, respectively. The apparatus was cleaned with 70% alcohol between each trial and the observer who scored the experiment was blinded to the treatment groups.

Structural Modeling and Docking

Sequence alignment of rat GluA1 and GluA2 was generated using multiple sequence comparison by log expectation (MUSCLE) using rat

Gria1 (GluA1) (Uniprot ID P19490) and

Gria2 (GluA2) (Uniprot ID P19491) sequences. The structure of rat GluA1 was modelled in 3D using

de novo protein trRosetta-constrained energy-minimization protocol [

57] and the chemical structure of perampanel was obtained from PubChem (CID: 9924495). The molecular docking study was carried out using autodock vina module implemented in PyRx tool. The 3D model of

Gria1 was constructed with modeller [

58] using

Gria2 as template (PDB: 5L1F). The obtained models were energy minimized and quality was assessed as described in [

59]. Interaction between

Gria1-Perampanel (PER) was predicted using similarities of superposed protein using 5L1F structure. Visualization of

Gria1/

Gria2-PER models was obtained with PyMOL software (

http://pymol.org/).

Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay (EILSA)

To detect the expression of pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, rats (N=6 from each group) were euthanized after three days post -PVD, and the hippocampal tissue lysates were prepared as described above. The concentrations of IL-4, TNF-α, and TGF-β were calculated using ELISA kits of rat anti-rabbit of each cytokine (Thermofisher Scientific, Canada). Samples were prediluted (1:10) based on an initial trial to find the appropriate dilution factor that validates the standard curve of the purchased ELISA kits. All samples were run in duplicates.

Statistical Analysis

All graphs were constructed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad) where values were expressed as mean ± SEM for all treatment groups. Statistical significance was assessed using a one-way ANOVA test and a Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test with 95% confidence interval using GraphPad InStat version 6.0 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA). The reported N values are obtained from independent experiments from brains of different animals. Probability values (P) of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Behavioral analysis was performed independently in a single blinded manner using EthoVisionXT (Noldus) software. Rotarod and FST vigor and success scores were obtained manually in a single blinded manner. For electrophysiological cLTP recordings, the order of recordings from ipsilateral vs. contralateral hippocampal slices were randomly chosen so that the length of time of slice preincubation was not a confounding variable.

4. Discussion

Elevation of extracellular glutamate following ischemic injury has been recognized as one of the major mechanisms mediating stroke-induced neurodegeneration and cognitive dysfunction. Previously, glutamate excitotoxicity was believed to be mainly mediated by NMDARs and this has been validated in preclinical trials by the observed neuroprotective effects of NMDAR antagonists, including Selfotel, Eliprodil, and Aptiganel [

70]. However, clinical studies of NMDAR antagonists for stroke therapy have thus far been disappointing owing to lack of clinical efficacy or serious psychomimetic adverse effects such as hallucinations and cognitive dysfunction [

71]. The present study explored the potential neuroprotective effects of perampanel, a clinically approved non-competitive AMPAR antagonist in our non-reperfusion ischemic stroke model. We demonstrated that intraperitoneal administration of perampanel 1 h post-stroke attenuated hippocampal neurodegeneration and improved stroke-induced behavioral deficits, which are consistent with the perampanel-induced improvements in synaptic plasticity and adaptations in surface-expressed AMPARs that promote neuroprotection.

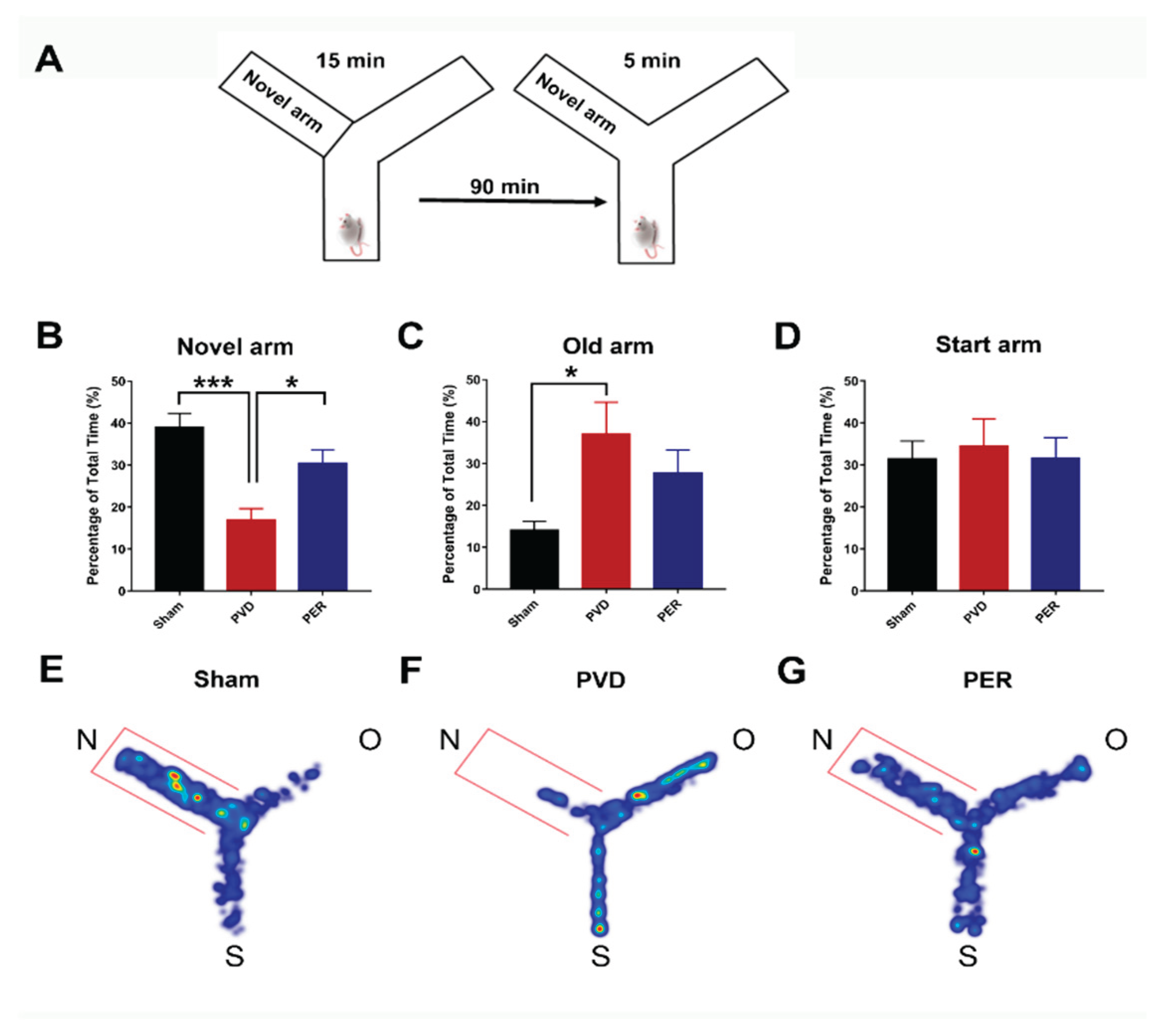

Post-stroke cognitive dysfunction is one of the major disability complications in stroke patients after recovery from ischemic attack [

72]. Numerous studies have shown impairment of hippocampal-dependent spatial memory with ischemic/reperfusion animal stroke model such as middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) [

73,

74,

75]. Our results using the non-reperfusion pial vessel disruption (PVD) ischemic stroke model showed that administration of perampanel shortly after the onset of focal cortical ischemia significantly attenuated the hippocampal-dependent spatial memory deficits. In agreement with our results, other AMPAR antagonists such as GYKI-52466 and NBQX had been successful in prevention of deficits in cognitive function in ischemic/reperfusion stroke models including bilateral carotid occlusion [

76] and four vessel occlusion [

77]. However, the non-competitive AMPAR blocker GYKI-52466 did not attenuate impairment in hippocampal-dependent spatial memory if administration was delayed after the induction of cerebral ischemia [

77]. In contrast, the present study and previous findings by others [

78,

79] similarly showed that perampanel had an extended therapeutic window and prevented the cognitive deficits even if administration was delayed after induction of ischemia/reperfusion. Results from our molecular docking analysis showed that the conserved amino acid residues, which were previously reported by others [

69] to be involved in perampanel and GluA2 interactions, may also mediate binding between perampanel and GluA1. Specifically, hydrogen bonding existed between perampanel and S512 and P516 of GluA1 pre-M1 region as well as N787 of the GluA1 M4 region. Yelshanskaya and colleagues [

69] found perampanel forming hydrogen bonding at the equivalent site N791 in GluA2 M4 domain as well as additional hydrogen bonds with S516 in pre-M1 segment and Y616 in the M3 domain. Additional hydrophobic interactions were found between perampanel and GluA1 and GluA2 pre-M1, M3 and M4 segments and before the pre-M1 sequence. These structural results are consistent with perampanel acting as a non-competitive antagonist that did not interfere with the ligand-binding domain. Moreover, we recently reported that perampanel, but not other calcium-permeable AMPAR antagonists (e.g., philanthotoxin-74, IEM 1460), significantly inhibited hippocampal neuronal cell death and post-hypoxia synaptic potentiation if administered either 5 min after hypoxia administration or after 45 min of normoxic washout following a 20-min hypoxia [

31]. In addition, our present results from in vivo focal cortical non-reperfusion ischemic stroke model provided evidence that perampanel can also prevent impaired learning and memory associated with permanent ischemia. Previous reports also showed that perampanel effectively attenuated cognitive deficits in animal models of traumatic brain injury (TBI) [

80] and status epilepticus (SE) [

81], suggesting that this non-competitive AMPAR antagonist has broad spectrum of neuroprotection against cognitive deficits caused by other neurological disorders.

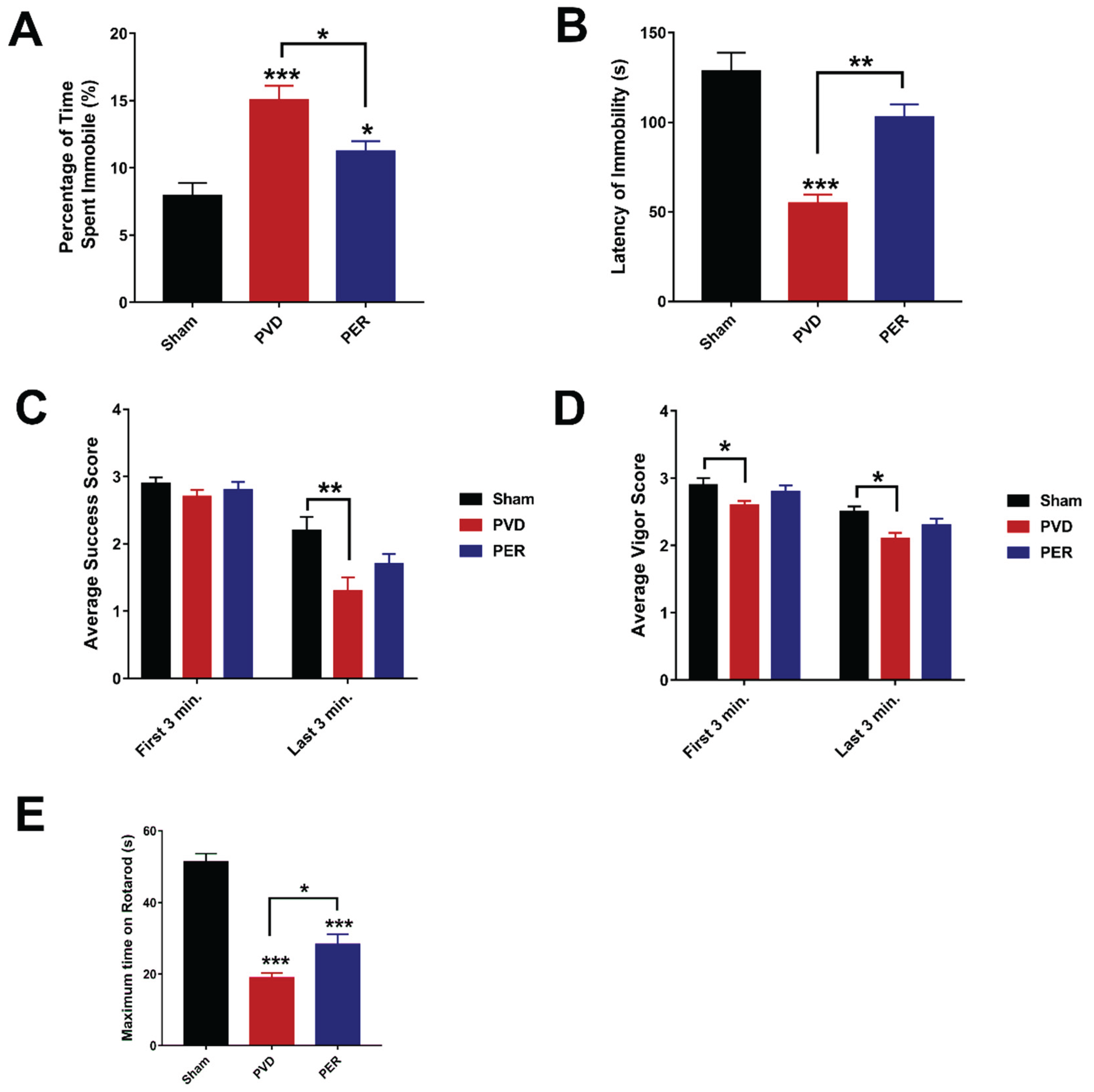

Motor deficits and mood dysfunction also represent major complications following stroke [

65]. Our results showed that the focal cortical ischemia caused severe motor deficits, similar to those previously reported in MCAO model [

82], and that perampanel administration shortly after the onset of cerebral ischemia significantly improved motor activity by ≈ 40% in the rotarod task. Similarly, the anti-seizure medication valproic acid also improved motor activity of rats following MCAO [

83]. Since perampanel was previously shown to cause dose-dependent motor deficits in rats at higher doses (e.g., 9.14 mg/kg) [

84], therefore, our studies used a lower dose of perampanel (i.e., 3 mg/kg) to minimize any perampanel-induced motor deficit at higher doses. Using 3mg/kg perampanel, we also showed that perampanel was effective in attenuating ischemia-induced anxiety-like and depressive-like behaviors in rats 72 hr following the PVD surgery. Our observation of the decreased thigmotaxis behavior with perampanel treatment in PVD-treated rats suggests that blocking AMPARs by perampanel can help ameliorate post-stroke anxiety that is often associated with stroke patients after recovery [

66]. Similarly, the observed PVD-induced anxiety-like behavior has also been reported previously in other stroke models in mice [

85]. This post-stroke anxiety-like behavior observed with PVD-treated rats might be induced by elevated extracellular adenosine and glutamate following ischemic stroke [

17,

26]. We have previously reported that prolonged A1R activation during hypoxia results in clathrin-mediated internalization of GluA1 AMPARs which accompanies the reduced levels of pGluA1-S831 and pGluA1-S845 in rat hippocampus [

45]. Our present result showing PVD-induced reduction in pGluA1-S831 and a previous report by others showing the reduction in pGluA1-S845 in dorsal hippocampus after treatments with anxiolytic drugs [

86], indicate an important role of GluA1 phosphorylation in anxiety-related behaviors. Moreover, our findings of decreased anxiety-like behavior in perampanel-treated rats in our PVD stroke model are in agreement with a previous study showing that other non-competitive AMPAR antagonists such as GYKI-52466 can profoundly block anxiety-like behavior in rodents [

87]. Interestingly, our results showed that not only anxiety, but also depressive-like behavior was markedly attenuated by perampanel. The observed increase in latency time of immobility and the lower time spent immobile in perampanel-treated PVD rats confirm the observed improvement in motor activity in the rotarod task. In addition, the observed improvements in success and vigor scores in the FST suggest that perampanel can inhibit the depressive-like behavior following cerebral ischemia. Thus, the preserved motor activity with the administration of perampanel may account for, in part, the observed improvement in performance in FST. In contrast, a previous study showed that the anti-depressant action of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and Tricyclic Antidepressants (TCAs) was enhanced by AMPAR potentiators; however, antagonizing AMPAR did not influence their action [

88]. Nevertheless, further studies in preclinical stroke models are needed to explore the effect of short-term and long-term use of perampanel on anxiety and depressive behavior following cerebral ischemia. Since perampanel attenuated all the behavioral deficits described above, further studies are also needed to investigate whether perampanel exhibits neuroprotective effects in other brain regions that control mood and motor function.

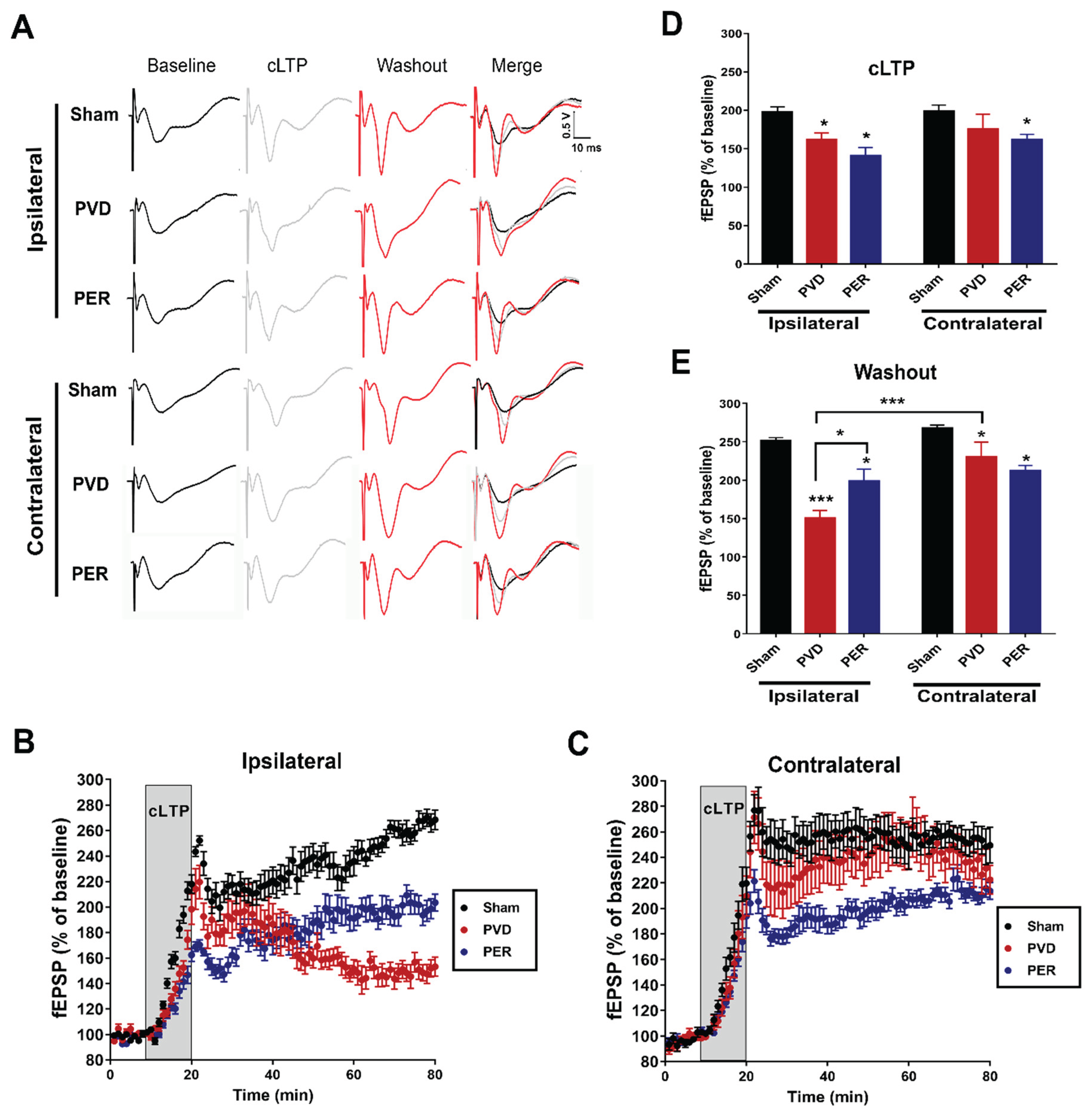

Consistent with our observation of perampanel-induced improvement in cognitive function after focal cortical ischemia, the present study also demonstrated that perampanel administered after cerebral ischemia significantly improved LTP maintenance in ipsilateral hippocampus; however, perampanel did not improve deficits in LTP induction. Moreover, while LTP induction and maintenance were moderately reduced in contralateral hippocampus compared to the ipsilateral side, perampanel did not appear to improve these PVD-induced LTP deficits. In contrast, other studies using different animal stroke models have reported similar levels of LTP deficits in hippocampus from both brain hemispheres [

89,

90], but the effects of perampanel on LTP deficits in these stroke models have not yet been reported. Therefore, our study provides evidence that perampanel exhibits a neuroprotective effect in our ischemic/non-reperfusion stroke model by preventing LTP deficits and preserving synaptic plasticity of hippocampal neurons in ipsilateral side of the hippocampus. However, further studies are needed to investigate whether these neuroprotective effects of perampanel and improvements in synaptic plasticity persist in the long term (

i.e., weeks to months after cessation of perampanel treatments). Adenosine signaling and AMPAR trafficking can play a very important role in stroke-mediated LTP deficits, as we previously reported that LTP deficit in aged rats was mediated by A1R-dependent mechanism involving clathrin-mediated endocytosis of GluA1 and GluA2 AMPAR subunits [

62].

Despite the ability of perampanel to block AMPARs and prevent LTP deficits and behavioral abnormalities in animal models of cerebral ischemia, TBI and SE as described above, the cellular mechanisms by which perampanel mediated these neuroprotective effects are not yet well elucidated. Thus, we investigated the changes in surface levels of GluA1 and GluA2 AMPAR subunits, since changes in GluA2 surface levels would affect calcium permeability of AMPARs [

91]. We found that focal cortical ischemia mediated reduction in surface levels of both GluA1 and GluA2 subunits 72 hrs post-PVD, indicating decreased functionality of AMPARs resulting in impaired learning and LTP deficits. Consistent with these in vivo findings, we also previously reported that hypoxia caused downregulation of GluA1 and GluA2 surface expression which involved clathrin-mediated AMPAR internalization [

29,

45]. In the present study, we showed that perampanel treatment partially restored the surface levels of GluA2 in both ipsilateral and contralateral side of hippocampus, which is expected to lead to the expression of more calcium-impermeable AMPARs and, hence, decreased neuronal damage as shown in this study. In contrast, perampanel did not attenuate the downregulation of surface-expressed GluA1 subunits of AMPARs ipsilaterally, but instead enhanced the GluA1 surface downregulation. Similarly, perampanel was previously shown to enhance GluA1 internalization following SE [

92]. This also suggests that perampanel may promote less expression of calcium-permeable AMPARs in ipsilateral side of ischemic lesion, which is expected to lead to less calcium excitotoxicity and subsequently to reduced neurodegeneration. Consistent with this, we observed that perampanel promoted neuroprotection in both the ipsilateral and contralateral sides of hippocampus, suggesting that perampanel may have other effect on GluA1 and GluA2 AMPAR trafficking that promotes increased neuronal activity and neuroprotection. It is noteworthy that the restored ratio of p-GluA1-S831 and p-GluA1-S845 may reflect the observed improvement in cognitive and anxiety-like behaviors after perampanel treatment in addition to the elevated maintenance of LTP, since the phosphorylated S831 and S845 residues of GluA1 subunits are known to play a crucial role in LTP and synaptic plasticity [

93]. Specifically, since perampanel has been shown in normal and rat model of SE to alter the upstream regulators of GluA1 phosphorylation at S831 and S845, including the protein kinases such as Ca2+/CaM-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII), protein kinase C (PKC), cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA3), and protein kinase A (PKA) [

92], therefore, further research is needed to reveal the potential of perampanel as a modulator of these protein kinases during cerebral ischemia.

Tissue necrosis and cell apoptosis, mediated by glutamate excitotoxicity, are commonly observed after focal cerebral ischemia and hypoxia in well-established animal stroke models as well as in patients with cerebral infarction [

24]. A previous study from our lab showed that focal ischemic lesion caused by PVD resulted in hippocampal cell death in the ipsilateral side of the hippocampus 48 hr following the surgery [

29]. Our current study suggests the potential of perampanel as an effective neuroprotective agent. Notably, the observed improvement in cognitive deficits following focal ischemia in perampanel-treated rats can be explained by the markedly attenuated hippocampal cell death and neurodegeneration as observed with the decreased PI and FJC staining in both ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal brain slices. Moreover, we showed recently that perampanel prevented hippocampal cell death by inhibiting the AMPAR-mediated adenosine-induced post-hypoxia synaptic potentiation following 20 min of hypoxia [

31]. This form of hypoxia-induced synaptic potentiation was dependent on the activities of both A1Rs and A2ARs, which promoted the expression of more calcium-permeable AMPARs that likely contributed to the perampanel-sensitive neuronal damage and neurodegeneration observed in the current study. Likewise, perampanel showed similar neuroprotective properties in global ischemic stroke models, SE and TBI [

78,

79,

80,

81]. These results suggest that perampanel possesses a neuroprotective potential and can significantly attenuate post-stroke behavioral deficits even when drug administration was delayed 1 hr following onset of cerebral ischemia.

Furthermore, we have examined the potential role of perampanel in suppressing the neuroinflammation induced by glutamate excitotoxicity. Several studies showed the complex role of microglia in neuronal damage mediated by ischemic injury [

94,

95,

96]. Microglial activation is usually classified into two categories of M1 (classical) and M2 (alternate) which lead to promotion or attenuation of inflammation, respectively [

97]. For instance, increased density of M1-activated microglia is associated with elevation of pro-inflammatory mediators including TNF-α and NO. In contrast, M2-phenotypes suppress inflammatory response by secretion of anti-inflammatory mediators such as TGF-β1 and IL-4 [

94,

95,

96,

97]. Previous reports from animal stroke models showed that TNF-α potentiates glutamate-induced neuronal damage following cerebral ischemia [

98,

99,

100]. Consistent with these studies, we found that the elevated levels of TNF- α, iNOS and nNOS post-PVD were attenuated by perampanel treatment, suggesting that blocking AMPARs with perampanel attenuates the release of pro-inflammatory mediators from M1-phenotype microglia or activated astrocytes in cerebral ischemia [

101]. Furthermore, our results showed that perampanel attenuated the elevation of glial markers GFAP and Iba-1. Whether AMPARs expressed on microglia or astrocyte surface membranes contribute to cytokine release in our PVD stroke model remains to be established. In contrast to the pro-inflammatory cytokines, our ELISA results showed that perampanel administration following focal ischemia restored the levels of the anti-inflammatory markers TGF-β1 and IL-4. Likewise, perampanel showed similar results in animal models of global ischemic stroke [

78,

79] and traumatic brain injury [

80]. The oxidative stress accompanying the changes in these pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators was also seen in clinical studies from stroke patients. It will be important in future studies to investigate the neuroprotective role of perampanel in suppressing neuroinflammation in the brains of stroke patients [

102,

103,

104]. Therefore, the repurposing of perampanel for stroke therapy and for other neurodegenerative disorders could significantly attenuate the chronic glutamate toxicity and functional deficits in progressive neurodegenerative conditions.

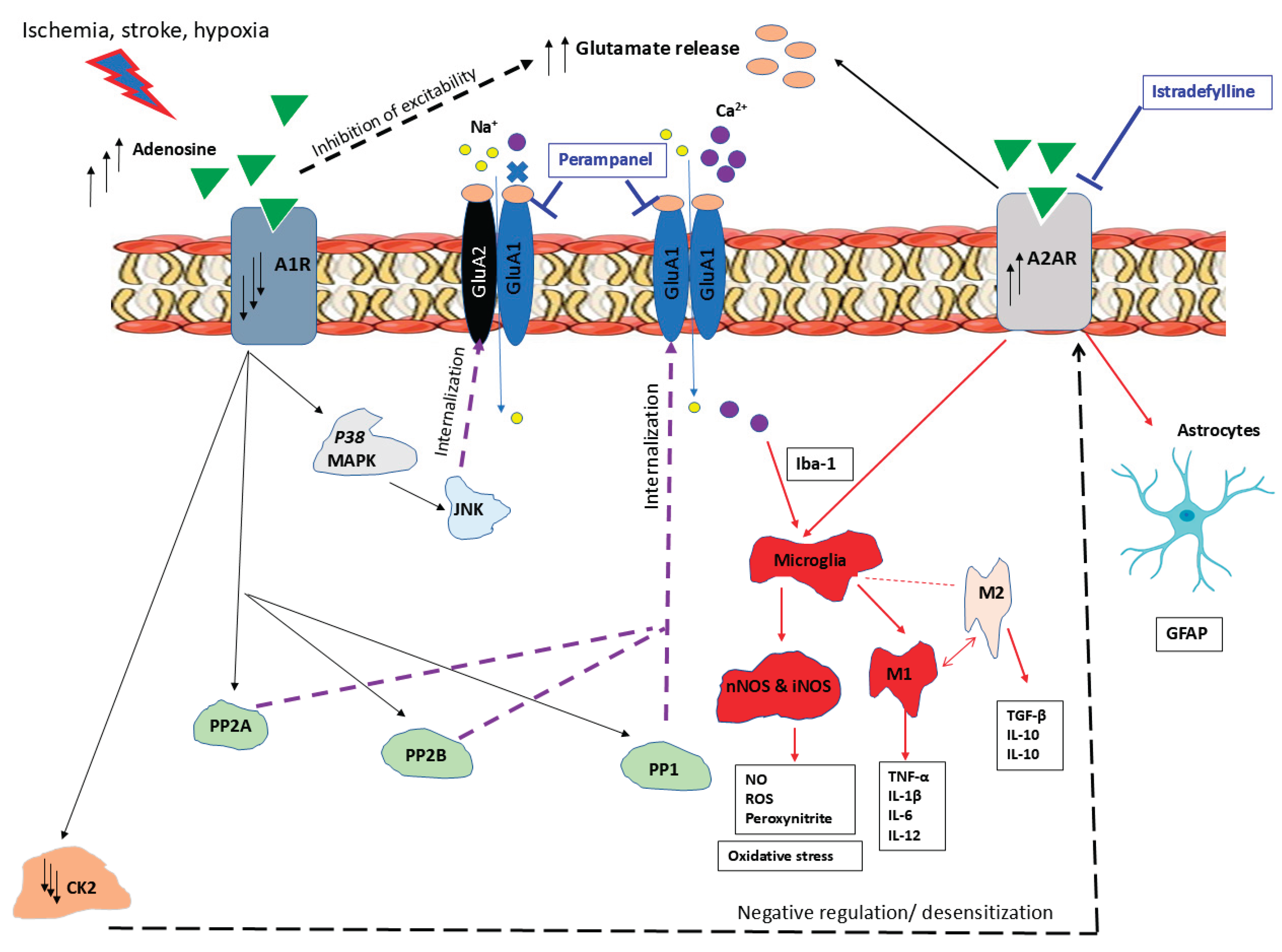

Interestingly, the findings of the present study demonstrate that AMPA receptor antagonism with perampanel produced neuroprotective effects comparable to those previously observed with istradefylline, a selective A2AR antagonist, as reported in our recent publication [

33]. Both pharmacological interventions effectively attenuated neuronal cell death and neuroinflammation following cerebral ischemia, as well as improved cognitive and motor outcomes in rodent models. This suggests that targeting excitotoxicity through AMPA receptor blockade and modulating neuroinflammatory pathways via A2AR receptor antagonism may represent complementary or converging strategies for mitigating ischemic brain injury (see

Figure 11). These findings provide further support for the therapeutic potential of glutamatergic and purinergic receptor modulation in the context of ischemic stroke. Therefore, future studies are needed to determine whether a combinatorial therapy involving the AMPAR antagonist perampanel and the A2AR blocker istradefylline proves more efficacious than monotherapy to reduce neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration and behavioral deficits in cerebral ischemia. A key limitation of this study is that it remains unclear whether the neuroprotective effects of perampanel are mediated directly through AMPAR antagonism or indirectly via interactions with adenosine signaling pathways.

Figure 1.

Perampanel restored cognitive function as shown by increased duration spent in the novel arm compared to PVD-vehicle treated rats. The PVD group displayed the lowest time exploring the novel arm and the highest percentage of time spent in the old arm compared to the other treatment groups. Arm durations were calculated as a percentage of the 5-minute second retrieval trial. (A) Cartoon figure represents Y-maze task. (B, C and D) Bar graphs represent percentage of time spent in novel, old and start arms, respectively. (E, F and G) Representative heat maps of the 5 minutes second trial acquired from Ethovision for sham, PVD + vehicle control and PVD+ perampanel 3 mg/kg, respectively (N= novel arm, O= old arm and S= start arm of the maze). N values=11 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p<0.05, ***= p<0.001.

Figure 1.

Perampanel restored cognitive function as shown by increased duration spent in the novel arm compared to PVD-vehicle treated rats. The PVD group displayed the lowest time exploring the novel arm and the highest percentage of time spent in the old arm compared to the other treatment groups. Arm durations were calculated as a percentage of the 5-minute second retrieval trial. (A) Cartoon figure represents Y-maze task. (B, C and D) Bar graphs represent percentage of time spent in novel, old and start arms, respectively. (E, F and G) Representative heat maps of the 5 minutes second trial acquired from Ethovision for sham, PVD + vehicle control and PVD+ perampanel 3 mg/kg, respectively (N= novel arm, O= old arm and S= start arm of the maze). N values=11 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p<0.05, ***= p<0.001.

Figure 2.

Administration of perampanel inhibited deficits in maintaining cLTP in ipsilateral side of hippocampus 72 h following PVD. Hippocampal slices of both ipsilateral and contralateral side from perampanel and vehicle treated groups were perfused with 50 µM Forskolin and 0.1 µM Rolipram in Mg 2+ - free aCSF for 10 min to induce LTP, followed by 60 min washout to demonstrate the ability to maintain cLTP. A Representative fEPSP traces showing average sample traces of the last 10 sweeps (final 5 minutes) of the baseline recording (in black color), 10 min cLTP (in grey color), and then last 5 min of the 60 min washout period (in red color), and merge of the three traces together from left to right (baseline + cLTP + Washout). Treatment groups from top to bottom are as following: ipsilateral sham, PVD + vehicle and PVD + Perampanel then contralateral sham, PVD + vehicle and PVD + Perampanel. (B, C) Time course plots of the average fEPSP slopes which were normalized to the baseline value (100%) of each recording from ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal slices, respectively. Sham, PVD + vehicle control and PVD + perampanel are presented in black, red and blue colors, respectively. (D and E) Summary bar graphs showing the mean normalized fEPSP slope percentage of the final 5 minutes (10 sweeps) of the 10 min cLTP and 60 min washout periods, respectively. Groups are compared to corresponding sham hippocampal slices for significance. N = 6 slices for each treatment group, from different rats. Graphed values show mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p < 0.05, *** = p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Administration of perampanel inhibited deficits in maintaining cLTP in ipsilateral side of hippocampus 72 h following PVD. Hippocampal slices of both ipsilateral and contralateral side from perampanel and vehicle treated groups were perfused with 50 µM Forskolin and 0.1 µM Rolipram in Mg 2+ - free aCSF for 10 min to induce LTP, followed by 60 min washout to demonstrate the ability to maintain cLTP. A Representative fEPSP traces showing average sample traces of the last 10 sweeps (final 5 minutes) of the baseline recording (in black color), 10 min cLTP (in grey color), and then last 5 min of the 60 min washout period (in red color), and merge of the three traces together from left to right (baseline + cLTP + Washout). Treatment groups from top to bottom are as following: ipsilateral sham, PVD + vehicle and PVD + Perampanel then contralateral sham, PVD + vehicle and PVD + Perampanel. (B, C) Time course plots of the average fEPSP slopes which were normalized to the baseline value (100%) of each recording from ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal slices, respectively. Sham, PVD + vehicle control and PVD + perampanel are presented in black, red and blue colors, respectively. (D and E) Summary bar graphs showing the mean normalized fEPSP slope percentage of the final 5 minutes (10 sweeps) of the 10 min cLTP and 60 min washout periods, respectively. Groups are compared to corresponding sham hippocampal slices for significance. N = 6 slices for each treatment group, from different rats. Graphed values show mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p < 0.05, *** = p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Administration of perampanel improved depressive-like behavior and motor deficits following PVD. Depressive-like behavior was assessed using forced swim test. Rats were placed in a water tank for 10 minutes, and time spent immobile was calculated as a percentage of the total trial time. Latency to immobility was plotted as times in seconds. (A) The PVD-perampanel treated group improved the immobility and showed 50 % reduction in time spent immobile compared to the vehicle-control group. (B) Perampanel treatment showed 100% improvement in latency time of immobility. (C and D) Average success and vigor scores were measured as mentioned in the methods section. In addition, we used rotarod test to assess motor deficits 3 days post-PVD. Administration of perampanel attenuated motor deficits caused by PVD ischemic lesion. Rats were pre-trained on the rotarod for 2 days before induction (two trials each day) and then tested 72 h following PVD surgery. E The bar chart shows the average maximum time spent on the rotarod before falling. Perampanel-treated rats showed significant improvement in the overall motor activity; however, PVD-vehicle control group spent the least time on the rotarod. N=12 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: * = p<0.05, ** = p< 0.01 and ***= p< 0.001.

Figure 3.

Administration of perampanel improved depressive-like behavior and motor deficits following PVD. Depressive-like behavior was assessed using forced swim test. Rats were placed in a water tank for 10 minutes, and time spent immobile was calculated as a percentage of the total trial time. Latency to immobility was plotted as times in seconds. (A) The PVD-perampanel treated group improved the immobility and showed 50 % reduction in time spent immobile compared to the vehicle-control group. (B) Perampanel treatment showed 100% improvement in latency time of immobility. (C and D) Average success and vigor scores were measured as mentioned in the methods section. In addition, we used rotarod test to assess motor deficits 3 days post-PVD. Administration of perampanel attenuated motor deficits caused by PVD ischemic lesion. Rats were pre-trained on the rotarod for 2 days before induction (two trials each day) and then tested 72 h following PVD surgery. E The bar chart shows the average maximum time spent on the rotarod before falling. Perampanel-treated rats showed significant improvement in the overall motor activity; however, PVD-vehicle control group spent the least time on the rotarod. N=12 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: * = p<0.05, ** = p< 0.01 and ***= p< 0.001.

Figure 4.

Perampanel attenuated anxiety-like behavior post-PVD. Perampanel increased center square entries while not significantly restoring center square duration in rats subjected to focal cortical ischemia; however, PVD-vehicle control treated group exhibited the lowest time and minimal entries to center square. (A) schematic representation illustrating open field task. (B) Center square durations were calculated as a percentage of the 15-minute trial. (C) Number of entries to center square during the task. (D, E and F) Representative heat maps from each treatment group were acquired on EthoVision. N=12 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p<0.05.

Figure 4.

Perampanel attenuated anxiety-like behavior post-PVD. Perampanel increased center square entries while not significantly restoring center square duration in rats subjected to focal cortical ischemia; however, PVD-vehicle control treated group exhibited the lowest time and minimal entries to center square. (A) schematic representation illustrating open field task. (B) Center square durations were calculated as a percentage of the 15-minute trial. (C) Number of entries to center square during the task. (D, E and F) Representative heat maps from each treatment group were acquired on EthoVision. N=12 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p<0.05.

Figure 5.

Effect of perampanel on surface levels of GluA1 and GluA2 in both sides of hippocampus 72 hr post-PVD. Focal ischemia resulted in significant decrease in surface levels of both GluA1 and GluA2 on both sides of the hippocampus and perampanel did not prevent these effects. Total levels of GluA1 and GluA2 were normalized to the corresponding expression of β-actin and ratios of surface levels/total protein were calculated and expressed as percentage of sham. (A) Representative images of Western blots of surface GluA1 and GluA2 from both ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal tissue lysate. (B, C, D and E) Bar charts showing the quantification of surface GluA1, pGluA1-S831, pGluA1-S845 and surface GluA2, respectively, in both ipsilateral and contralateral sides. Sham (black), PVD-vehicle control (red) and PVD-perampanel treated group (blue). Focal cortical ischemia caused significant decrease in surface expression of GluA1 and GluA2 AMPAR subunits and reduced the ratio of phosphorylated S831 and S845 of GluA1. Perampanel treatment partially restored the levels of GluA1 AMPAR subunits in contralateral hippocampus and increased the pGluA1-S831 and pGluA1-S845 from both ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampus. N = 4 from different rats for each treatment group. Graphed values show mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, ***= p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Effect of perampanel on surface levels of GluA1 and GluA2 in both sides of hippocampus 72 hr post-PVD. Focal ischemia resulted in significant decrease in surface levels of both GluA1 and GluA2 on both sides of the hippocampus and perampanel did not prevent these effects. Total levels of GluA1 and GluA2 were normalized to the corresponding expression of β-actin and ratios of surface levels/total protein were calculated and expressed as percentage of sham. (A) Representative images of Western blots of surface GluA1 and GluA2 from both ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampal tissue lysate. (B, C, D and E) Bar charts showing the quantification of surface GluA1, pGluA1-S831, pGluA1-S845 and surface GluA2, respectively, in both ipsilateral and contralateral sides. Sham (black), PVD-vehicle control (red) and PVD-perampanel treated group (blue). Focal cortical ischemia caused significant decrease in surface expression of GluA1 and GluA2 AMPAR subunits and reduced the ratio of phosphorylated S831 and S845 of GluA1. Perampanel treatment partially restored the levels of GluA1 AMPAR subunits in contralateral hippocampus and increased the pGluA1-S831 and pGluA1-S845 from both ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampus. N = 4 from different rats for each treatment group. Graphed values show mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, ***= p < 0.001.

Figure 6.

Rat Gria1 (GluA1) and Gria2 (GluA2) amino acid sequence alignment. Alignment was generated using multiple sequence comparison by log expectation (MUSCLE) using rat Gria1 (GluA1) (Uniprot ID P19490) and Gria2 (GluA2) (Uniprot ID P19491) sequences. Red stars denote amino acid residues that interact with perampanel as revealed from molecular docking analysis (see Figure 7). Amino acid numbers on the right refer to the amino acids of mature protein (excluding the signal sequence). Perampanel binds to a region before transmembrane domain M1 (pre-M1), M1, M3, and M4 regions. Perampanel does not bind to the re-entrant loop M2 domain, the extracellular amino terminal domain (ATD) and ligand binding domain (LBD), or the cytoplasmic domain containing the S831 (PKC site) and S845 (PKA site).

Figure 6.

Rat Gria1 (GluA1) and Gria2 (GluA2) amino acid sequence alignment. Alignment was generated using multiple sequence comparison by log expectation (MUSCLE) using rat Gria1 (GluA1) (Uniprot ID P19490) and Gria2 (GluA2) (Uniprot ID P19491) sequences. Red stars denote amino acid residues that interact with perampanel as revealed from molecular docking analysis (see Figure 7). Amino acid numbers on the right refer to the amino acids of mature protein (excluding the signal sequence). Perampanel binds to a region before transmembrane domain M1 (pre-M1), M1, M3, and M4 regions. Perampanel does not bind to the re-entrant loop M2 domain, the extracellular amino terminal domain (ATD) and ligand binding domain (LBD), or the cytoplasmic domain containing the S831 (PKC site) and S845 (PKA site).

Figure 7.

Structure of Gria1 (GluA1) and Gria2 (GluA2) interacting with perampanel (PER). (A) GluA1 structure viewed parallel to the membrane. Each subunit is in different color. The inner and outer sides of the membrane are indicated by parallel bars.

(B and C) Perampanel presented in yellow. Close-up views of the binding site in GluA1-PER

(B) and GluA2-PER

(C) structures [

69] (see text for detail). Hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with perampanel are described in text. ATD, amino terminal domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; TMD, transmembrane domain.

Figure 7.

Structure of Gria1 (GluA1) and Gria2 (GluA2) interacting with perampanel (PER). (A) GluA1 structure viewed parallel to the membrane. Each subunit is in different color. The inner and outer sides of the membrane are indicated by parallel bars.

(B and C) Perampanel presented in yellow. Close-up views of the binding site in GluA1-PER

(B) and GluA2-PER

(C) structures [

69] (see text for detail). Hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions with perampanel are described in text. ATD, amino terminal domain; LBD, ligand-binding domain; TMD, transmembrane domain.

Figure 8.

Effect of perampanel on PVD-increased cell death. Administration of perampanel decreased cell death in both ipsilateral and contralateral sides of hippocampus. Hippocampal slices were stained with propidium iodide (PI), a fluorescent marker for cell death. (A) Full montage of hippocampus showing PI fluorescence obtained with 10 X. Increased PI fluorescence indicates increased cell death. (B) 63X of the representative boxed regions in A showing CA1-area of hippocampus stained with PI. Scale bars: 1 mm (whole hippocampus, in A) and 10 µm (CA1, in B). (C) Summary bar graph showing relative PI intensity of the CA1 images in sham, PVD + vehicle control, and PVD + perampanel groups. Perampanel treatment significantly attenuated cell death in both ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampus. Levels of hippocampal neuronal damage were lower in contralateral compared to ipsilateral side of PVD lesion. N=5 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p<0.05, **= p<0.01, ***= p<0.001, NS= non-significant.

Figure 8.

Effect of perampanel on PVD-increased cell death. Administration of perampanel decreased cell death in both ipsilateral and contralateral sides of hippocampus. Hippocampal slices were stained with propidium iodide (PI), a fluorescent marker for cell death. (A) Full montage of hippocampus showing PI fluorescence obtained with 10 X. Increased PI fluorescence indicates increased cell death. (B) 63X of the representative boxed regions in A showing CA1-area of hippocampus stained with PI. Scale bars: 1 mm (whole hippocampus, in A) and 10 µm (CA1, in B). (C) Summary bar graph showing relative PI intensity of the CA1 images in sham, PVD + vehicle control, and PVD + perampanel groups. Perampanel treatment significantly attenuated cell death in both ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampus. Levels of hippocampal neuronal damage were lower in contralateral compared to ipsilateral side of PVD lesion. N=5 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: *= p<0.05, **= p<0.01, ***= p<0.001, NS= non-significant.

Figure 9.

Effect of perampanel on ischemia-induced neurodegeneration. Administration of perampanel attenuated neurodegeneration in hippocampus following PVD. Coronal hippocampal slices were stained with FluoroJade-C (FJC), a specific fluorescent marker for degenerating neurons. (A) Full montage of hippocampus fluorescently stained with FJC obtained with 10 X objective lens. Full montage images of sham and PVD were adopted from our recent publication [

33]. (B) 63 X magnification of the representative regions of interest in A (white boxed regions) showing CA1-area of ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampus. Scale bars: 1 mm (whole hippocampus, in A) and 40 µm (CA1, in B). (C) Summary bar graphs of relative FJC intensity of the CA1 images shown in B. N=5 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: **= p<0.01, ***= p<0.001.

Figure 9.

Effect of perampanel on ischemia-induced neurodegeneration. Administration of perampanel attenuated neurodegeneration in hippocampus following PVD. Coronal hippocampal slices were stained with FluoroJade-C (FJC), a specific fluorescent marker for degenerating neurons. (A) Full montage of hippocampus fluorescently stained with FJC obtained with 10 X objective lens. Full montage images of sham and PVD were adopted from our recent publication [

33]. (B) 63 X magnification of the representative regions of interest in A (white boxed regions) showing CA1-area of ipsilateral and contralateral hippocampus. Scale bars: 1 mm (whole hippocampus, in A) and 40 µm (CA1, in B). (C) Summary bar graphs of relative FJC intensity of the CA1 images shown in B. N=5 for each treatment group. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. Significance values: **= p<0.01, ***= p<0.001.

Figure 10.

Perampanel oppositely regulates the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators in the hippocampus post-PVD. Perampanel treatment inhibited the PVD-induced elevation of TNF-α, nNOS and iNOS but recovered the levels of TGF-β1 and IL-4 to near baseline (sham) levels. (A-C). The total concentration of TGF-β1, IL-4, and TNF-α, respectively in ipsilateral hippocampal lysates measured with ELISA kits. Administration of perampanel prevented the increase in nNOS, iNOS, GFAP and Iba-1 following PVD. (D). Representative Western blot images of total ipsilateral hippocampal tissue lysates. (E-H). Bar chart showing relative nNOS, iNOS, GFAP and Iba-1 expression, respectively (% of sham). All tissue lysates were prepared 72 hr following PVD surgery. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. N=6 in each group (independent samples). Significance values: *= p<0.05, **= p<0.01, ***= p<0.001.

Figure 10.

Perampanel oppositely regulates the pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators in the hippocampus post-PVD. Perampanel treatment inhibited the PVD-induced elevation of TNF-α, nNOS and iNOS but recovered the levels of TGF-β1 and IL-4 to near baseline (sham) levels. (A-C). The total concentration of TGF-β1, IL-4, and TNF-α, respectively in ipsilateral hippocampal lysates measured with ELISA kits. Administration of perampanel prevented the increase in nNOS, iNOS, GFAP and Iba-1 following PVD. (D). Representative Western blot images of total ipsilateral hippocampal tissue lysates. (E-H). Bar chart showing relative nNOS, iNOS, GFAP and Iba-1 expression, respectively (% of sham). All tissue lysates were prepared 72 hr following PVD surgery. Values are shown as mean ± SEM. N=6 in each group (independent samples). Significance values: *= p<0.05, **= p<0.01, ***= p<0.001.

Figure 11.

A summary of identified underlying downstream signalling of adenosine A1/A2A receptor cross talk and regulation of GluA2-lacking AMPA receptors following cerebral ischemia. A1R stimulation leads to clathrin-mediated endocytosis of GluA1 and GluA2 AMPARs via activation of p38 MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), protein phosphatases PP2A, PP2B and PP1 [

94,

95,

96,

97]. Chronic A1R stimulation in ex vivo hypoxia/normoxia ischemia model or pial vessel disruption (PVD)-induced focal cortical stroke model leads to desensitization of A1R and upregulation of A2AR via CK2 [

94,

95,

96,

97]. Inhibition of A2AR with istradefylline in PVD-induced stroke model prevents neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation and attenuates behavioral abnormalities [

94,

95,

96,

97]. Similarly, inhibition of AMPARs with perampanel in PVD-induced stroke model prevents neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation and significantly reduces LTP and behavioral deficits (this study). Whether combined perampanel and istradefylline treatments produces greater neuroprotection and improved behavioral outcomes in stroke model warrants further investigation.

Figure 11.

A summary of identified underlying downstream signalling of adenosine A1/A2A receptor cross talk and regulation of GluA2-lacking AMPA receptors following cerebral ischemia. A1R stimulation leads to clathrin-mediated endocytosis of GluA1 and GluA2 AMPARs via activation of p38 MAPK, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), protein phosphatases PP2A, PP2B and PP1 [

94,

95,

96,

97]. Chronic A1R stimulation in ex vivo hypoxia/normoxia ischemia model or pial vessel disruption (PVD)-induced focal cortical stroke model leads to desensitization of A1R and upregulation of A2AR via CK2 [

94,

95,

96,

97]. Inhibition of A2AR with istradefylline in PVD-induced stroke model prevents neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation and attenuates behavioral abnormalities [

94,

95,

96,

97]. Similarly, inhibition of AMPARs with perampanel in PVD-induced stroke model prevents neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation and significantly reduces LTP and behavioral deficits (this study). Whether combined perampanel and istradefylline treatments produces greater neuroprotection and improved behavioral outcomes in stroke model warrants further investigation.