1. Introduction

As a partial differential equation (PDE) [

1,

2], the telegraph equation is used as a model for the dynamics of electric potential and electric current on a lossy transmission line [

3,

4,

5]. From broader perspectives, telegraph-like equations describe diverse phenomena in nature, biology, and industrial devices, for instance: [i] dispersion in turbulent flows [

6], [ii] flows through hollow tubes [

7,

8], [iii] structural dynamics [

9,

10,

11,

12], [iv] vibration of a string, say, of a guitar [

13,

14,

15,

16], [v] signal transmission through biological neurons [

17,

18,

19], [vi] population dynamics [

20], [vi] heat conduction with Fourier-Cattaneo or Maxwell-Cattaneo law containing slight wave propagations [

21,

22], [vii] quantum electrodynamics [

23], to name a few.

From theoretical perspectives, telegraph-like equations harbor several key features of temporal transients, reaction or leakage, diffusion, propagating waves [

24,

25], sources and sinks. A variety of analytical and semi-analytical solutions to telegraph-like equations have so far been developed [

21,

26,

27]. Many numerical solutions to telegraph-like equations have been published as well [

14,

15,

28]. Especially, our dimensional analysis of telegraph equations uncovered hitherto neglected mechanisms [

17].

Meanwhile, let us turn our attention to our on-going research project. Here, we are assigned to help perform efficient underfill encapsulation for electronics industry.

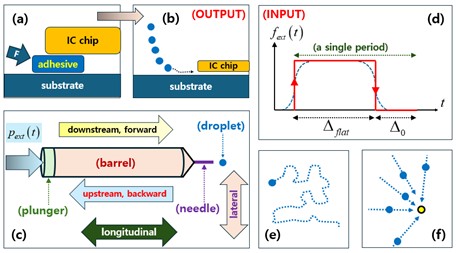

Figure 1(a,b) depict typical underfill encapsulation situations [

29,

30]. The goal is to provide adhesive solutions underneath an integrated circuit (IC) chip that is to be bonded to the underlying substrate. The overlapping arrow from

Figure 1(a,b) indicates a decreasing feature size of an IC chip.

In older days, a bulk of adhesive fluid could have been pushed into the wide gap by an external force marked by ‘F’ on

Figure 1(a). Conventional jetting of rather long liquid mass as illustrated on

Figure 1(a) may be still employed for relatively coarse three-dimensional (3-D) printing [

31]. When a miniature 3-D printer is employed for filling, say, very tiny holes, continuous liquid flow cannot fill in those holes because of large flow resistance per volume.

In recent days with ever-increasing miniaturization, the gap between IC chips and a substrate is so narrow that epoxy jetting or forced injection as shown on

Figure 1(a) cannot accomplish adequate underfill encapsulation. Therefore, only sufficiently tiny droplets of adhesive solution are sucked into those thin gaps thanks to favorable capillary pulling force as shown on

Figure 1(b) [

29,

30,

32].

Concerning the modern-day underfill encapsulation illustrated on

Figure 1(b), our task is to measure and control at real time the droplet dynamics of droplet dispensers so that certain specified volumes of droplets are ejected on demand [

30,

33,

34].

Our experimental data let us believe that the dynamics at hand encompasses both fluid flows and structural deformation of a droplet dispenser on equal footing. Interactions between these two branches of mechanics are quite complicated so that we cannot analytically solve the relevant dynamics with high precision. Detailed numerical simulations are now available in literature on the whole or partial processes of droplet dispensing [

7,

30,

35]. Although those details help us to understand what is going on, they cannot be utilized for real-time control of droplet dispensing [

30].

Therefore, we decided to seek a simpler physical model for droplet dispensing. After several trials, we have learned that a telegraph-like equation and its solution could provide us with necessary clues as to the real-time controllability of a whole dispenser. Especially, the electric-circuit interpretation of the solutions to telegraph-like equations could help us to construct proper real-time measurement and/or control circuits [

31,

33,

36].

In this connection, vibration control is an enabling technique not only in transportation vehicles and structural dynamics but also in manufacturing of semiconductor and precision machines [

37]. In this respect, one of the goals of this study is to lay foundations on analytical tools that arise from telegraph-like equations. Such analytical tools could be utilized to enhance the functionalities of pertinent real-time control devices based on electric circuits that emulate telegraph equations [

38].

Once those control devices are conFigured, we are trying to implement modern algorithms for physics-informed neural network (PINN) and/or physical AI (artificial intelligence) [

32,

39,

40]. That is why we are frequently referring in this study to fundamental concepts underlying biological neuroscience [

25,

41]. We hope that this study contributes ultimately to realizing neuromorphic circuits [

42].

Figure 1(c) illustrates a process of a single immunization shot administered through a medical syringe. Here, the driving force is exerted by hand pressure as given on

Figure 1(c,d) [

7,

31,

43]. For a proper injection shot, a nurse may have been trained, say, for a couple of months. Our droplet dispenser requires a certain total volume of droplets to be dropped over the chip area, after which the droplet dispenser is moved to another location over a substrate as shown by the trajectory on

Figure 1(e). The whole encapsulation process is desired to be real-time automated. Consequently, our droplet dispensers are much harder to control than a single immunization injector shown on

Figure 1(c).

Especially, the dynamics of droplet breakup and ejection should be adequately examined by taking into consideration capillarity, wetting, surface tension, and gravity [

7,

15,

24,

30,

35,

44,

45].

Table 1 makes comparison among several fluid-ejection devices.

Here in this study, we will consider the fundamental aspects of the frequency dispersion relations of telegraph equations over infinite one-dimensional (1-D) domain [

46]. Some of the characteristics found for telegraph equations are well-known. Notwithstanding, we focus on deriving those features not only from theorists’ perspectives but also from the perspective of practicing engineers.

Along this line of reasoning, section 2 provides reasons for why we examine telegraph equations from fresh look.

Section 3 repeats the derivations of 1-D telegraph-like equations along with some reduced forms.

Section 4 reexamines a 3-D telegraph equation for comparison to 1-D equations.

Section 5 provides solutions to the well-known dispersion relation for the leaky telegraph equation. In addition, new findings including crossovers are offered for the dispersion relation of a leak-free telegraph equation.

Section 6 handles the response functions for typical circuit configurations, thus showing features of low-pass filters.

Section 7 offers some relevant discussions, followed by conclusions in section 8. Appendices are provided at the end to make this manuscript self-contained.

2. Motivation for this Study

As depicted on

Figure 1(c), a droplet dispenser consists roughly of a plunger, a barrel, and a (contracting) nozzle [

7]. An external forcing, say, compressed-air pressure is acting on the outside face of a plunger as illustrated on the left portion of

Figure 1(c). Notice that the compressed-air excitation is just one of widely employed methods of periodically driving droplet dispensers [

33,

39,

47]. As depicted on

Figure 1(b), a droplet dispenser is employed for generating a stream of droplets of epoxy solution (being an electric insulator). This succession of droplets is dropped down on an electronic chip undergoing encapsulation process [

30].

Let us denote the excitation by

with

being time. An idealized form of

is displayed on

Figure 1(d), where a single period out of repeated train of excitations is indicated by four segments of red lines [

48]. As an initial stage, the infinitesimally short step-up event corresponds to pressurization. During the upper flat period

, a main event of droplet ejection takes place. Afterwards, an infinitely short step-down event is enforced during which the ejection of a droplet is initiated and then terminated [

31]. During the dormant or rest period

, the droplet dispenser is moved to another position over a substrate as illustrated on

Figure 1(e). Such a four-step process is repeated as designed. In our experimental runs,

and

, respectively.

Meanwhile, let us consider side conditions that consist of initial conditions (ICs) and boundary conditions (BCs) [

1,

2,

19]. The damped vibration of a string of finite longitudinal length requires specifying certain valid boundary conditions (BCs). In addition, proper initial conditions are required for analytic solutions to telegraph equations [

4,

22,

28,

49,

50]. Such Cauchy problems (PDEs and side conditions) for telegraph equations over finite 1-D domain will be handled in a separate publication.

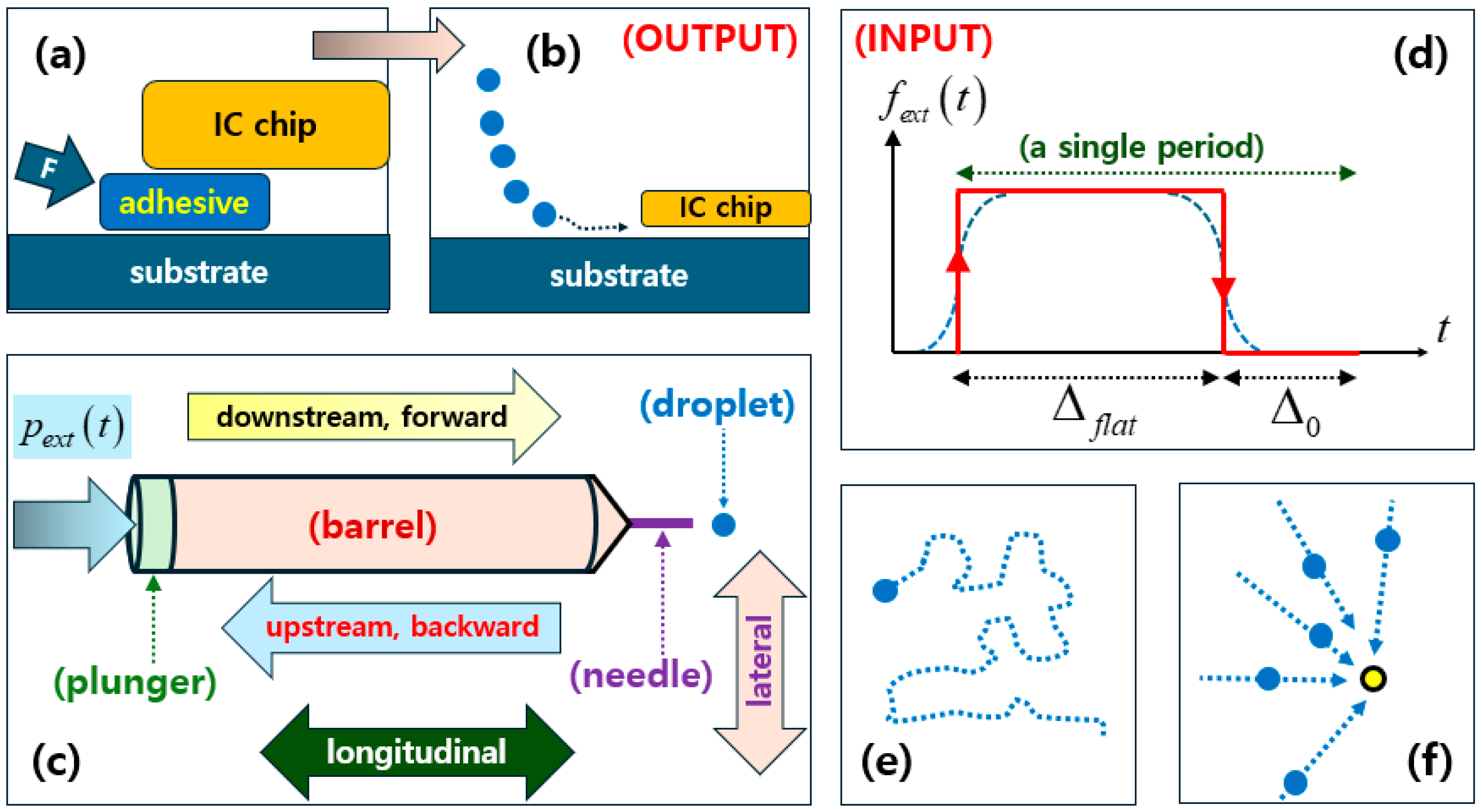

In the meantime,

Figure 2(a) illustrates a string of finite length

, where a string in a quiescent state is just the horizontal green line along the longitudinal

-direction (indicated by the horizontal double-headed arrow).

We will consider henceforth an infinite 1-D domain

, although a finite length

is introduced on

Figure 2 for an illustrative purpose. Over time

, this string could undergo lateral deformation

in the lateral direction (indicated by the vertical double-headed arrow) perpendicular to the

-direction. For instance,

and

indicate such lateral displacements at distinct times

and

on

Figure 2(a). Both ends of the string are held fixed solely for illustrative purposes [

14,

15].

Let us copy the telegraph equation presented in [

15] with slight alterations in notation as follows.

Here,

is an internal damping and

is Young’s modulus. In addition, the string parameters

are the longitudinal tension, the mass per unit length, and the radius of a circular cross section of a string, respectively [

16].

The first term on the left-hand side (LHS) of equation (1) signifies temporal decay. The wave equation made of two nearby terms

on both sides of equality sign helps to determine the sound velocity

of a string. This wave equation gives rise to propagating solutions consisting of a pair of functions

for suitably differentiable forms of

[

2,

14,

19,

25,

27]. The last fourth-order term proportional to

on the RHS stands for flexural (or bending) stiffness due to finite-sized cross section [

7,

10,

11,

12,

14,

24]. If this flexure term is neglected, equation (1) is reduced to the following.

Transient damping of a solid string of a finite radius could occur due to surrounding viscous incompressible fluid [

13,

22]. Here, one-way influence of a surrounding fluid flow on a string is assumed. Viscous drag by fluid on a solid gives rise to the first-order temporal-derivative term

appearing in the above simpler telegraph equation. Furthermore, two-way fluid-structure interactions are handled in [

8], where nonlinearities are hardly avoided. Such fluid-structure interactions play a crucial role also in underfill encapsulation [

30], where thermal mismatches become often problematic.

Meanwhile, the influence of solid-tube deformation on the flow inside a tube is exploited for nondestructive ultrasonic measurement. Collapsible tube deformations that are dramatically larger than our minute deformations have been measured by ultrasonic techniques, where flows are maintained by applied pressure gradient as on

Figure 1(c),

Figure 2(b),

Figure 2(c) and

Figure 2(d) [

51].

Pressure waves propagating through incompressible inviscid fluid inside a cylindrical elastic tube have been examined from diverse perspectives [

8]. In this connection, let us turn to

Figure 2(b–d), each of which displays a circular hollow tube of finite radius.

In terms of Cartesian

-coordinates as on

Figure 2(a), any radial direction on the

-plane is called a lateral direction. In the cylindrical

-coordinate as on

Figure 2(b–d), the axial direction is pointing in the

-coordinate, while the radial direction is pointing in the

-coordinate. Inside each hollow tube lies a volume of fluid. The displacement components

are provided along with their corresponding coordinates

. In addition, the usual circumferential (azimuthal or angular) symmetry is assumed so that

and the

-dependences are suppressed.

Figure 2(b–d) correspond to distinct states of fluid flows and longitudinal pressure gradients as marked on each subfigure and summarized on

Table 2. These pressure gradients result from the compressed-air excitation as depicted on

Figure 1(c,d).

It is difficult in general to find analytical solutions to the fluid flow through a circular hollow tube of finite longitudinal length [

4]. In this connection, recall that the solution to the unsteady Poiseuille flow has been constructed solely over a circular tube of infinite longitudinal length [

52]. This fact makes all practical problems involved in droplet dispensers extremely difficult. Meanwhile, the momentum loss due to the shear stress between the inner wall of a cylindrical tube and internally flowing fluid can be considered as kind of leakage from the viewpoint of flowing fluid.

With both ends assumed fixed, no-flow case on

Figure 2(b) exhibits a displacement profile that is symmetric across the central lateral plane. If downstream flow is set up as on

Figure 2(c) thanks to favorable pressure gradient

, the lateral displacements on the downstream half are greater on average than those on the upstream half. If upstream flow is set up as on

Figure 2(d) due to unfavorable pressure gradient

, the lateral displacements on the downstream half are smaller on average than those on the upstream half.

If temporal delay is neglected for simplicity,

corresponds roughly to pressurization period, while

corresponds roughly to depressurization period. Such periodic cycles consisting of pressurization and depressurization are executed by a pneumatic device for a droplet dispenser that is set up in our laboratory [

33,

34].

During unsteady transient processes as in our situations, Darcy-Weissbach law (the average longitudinal pressure gradient being proportional to the average fluid velocity squared) breaks down [

51], thereby rendering extremely unpredictable the fluid flows inside a tube.

On

Figure 2(c), we have illustrated the lateral displacements at two distinct locations, namely,

and

as indicated by the thick vertical lines and marked with 1Q (the first quadrant) and 3Q (the third quarter). To this end, we employed a modern nanoscopic optical displacement sensor, thereby measuring displacements on the order of sub-micrometer. In addition, the difference

turns out to be temporally periodic as a response to periodic compress-air excitation.

Let us examine more closely the displacement fields of a circular tube as depicted on

Figure 2(b–d). Also shown on

Figure 2(b) are the radius

(not a coordinate) of a tube and the tube thickness

(not time). Suppose that

such that the tube is relatively thin in comparison to its radius. Although the tube thickness is still accounted for, the displacement fields can be taken as being

-independent. In this situation, the governing PDEs are the elastodynamic Navier equations [

9,

12].

In the thin-tube limit

, Navier equations can be reduced to thin-plate equations for the two displacement components

, which depend only on

[

10]. Such thin-plate equations play a crucial role in handling not only structural dynamics but also semiconductor thin films [

50]. In our droplet dispensers, we expect

so that we illustrate only

on

Figure 2(b–d). With these approximations,

being of our primary concern stands for a bending mode, whereas

stands for a pressure (‘p’ for short) mode. In comparison, a shear (‘s’ for short) mode is missing since we assumed

[

10]. Alternatively,

is called an ‘out-of-plane displacement’, whereas

is called an ‘in-plane displacement’.

Let us give a rough description of the reduced Navier thin-plate equations. Most importantly, these thin-plate equations possess the features of temporal transient, wave phenomenon, diffusion, leakage, and external source, namely, all features exhibited by the telegraph equation presented in equation (1). However, these reduced Navier equations contain partial differentials

in addition to those partial differentials shown in equation (1). In other words, these reduced Navier equations are second order in time whilst they are fourth order in space in great distinction to the generix telegraph equations [

7,

24].

Quite importantly, the first-order derivative

arises from the one-way fluid flows as depicted on

Figure 2(c,d) during unsteady states. This presence of

popping up in the reduced Navier equations lets the problem at hand be asymmetrical across the central lateral plane as illustrated by the spatial profile of the lateral displacement

on

Figure 2(c,d) [

10].

However, both establishing proper BCs and finding associated analytical solutions to the thin-plate equations turn out to be significantly complicated. This is why we decided to examine a simpler telegraph equation in this study to explore the afore-mentioned compound effects. In this sense, we are seeking a ‘computationally minimal model’ for droplet dispensers [

39].

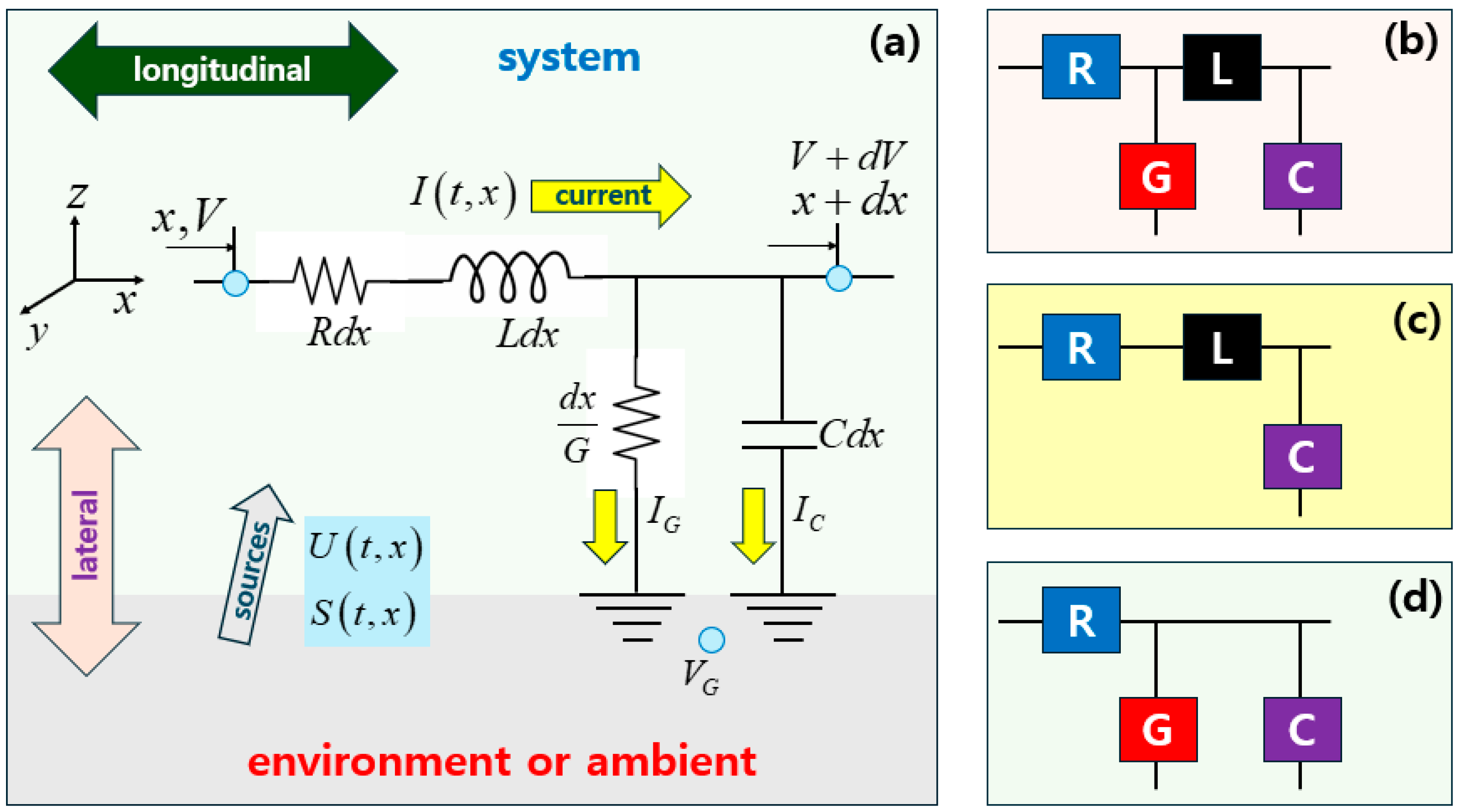

3. Derivation of One-Dimensional (1-D) Telegraph Equation

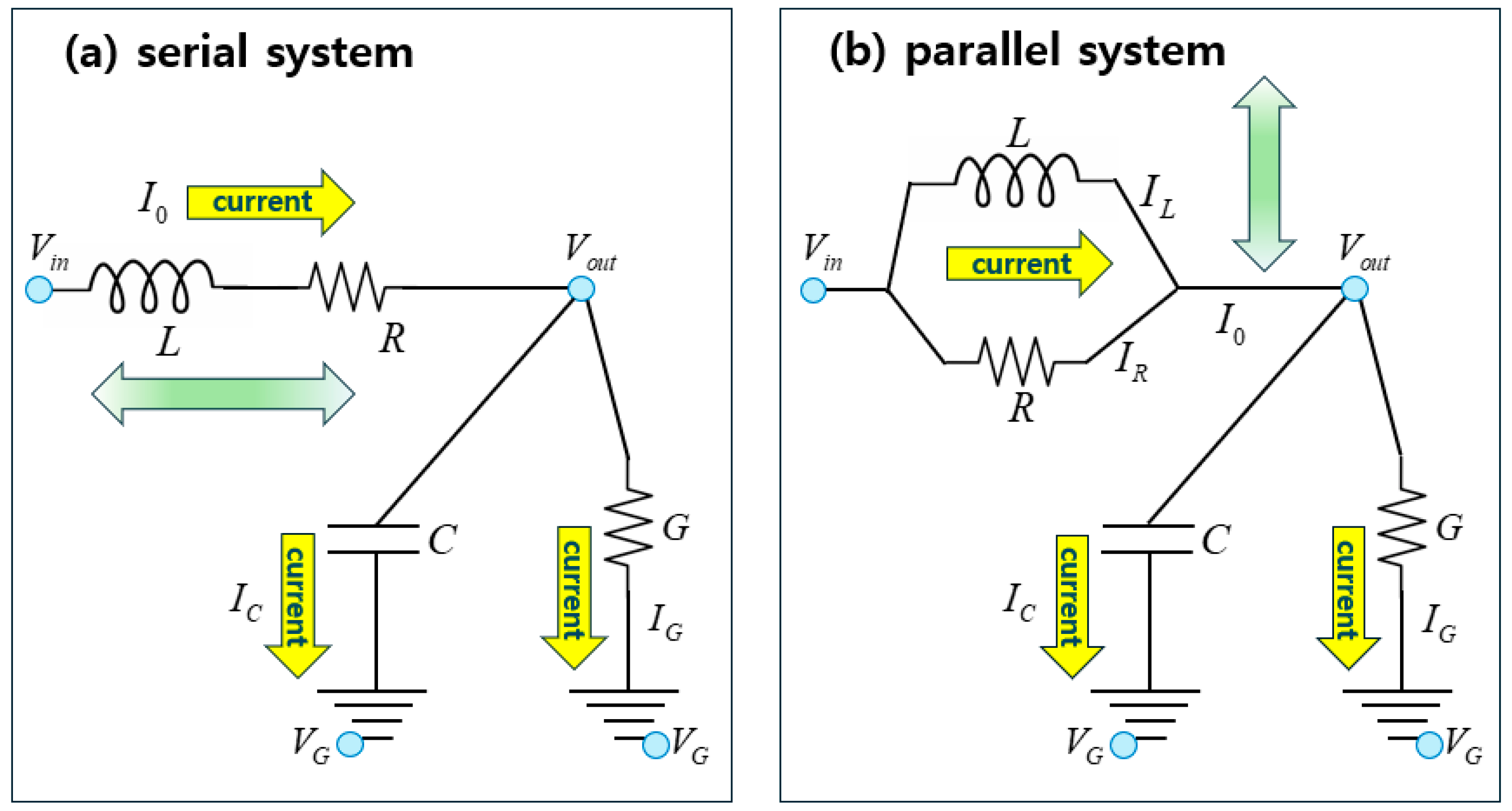

We are taking conventional steps to derive a telegraph equation with the help of the electric circuit displayed on

Figure 3(a) [

31].

Figure 3(a) exhibits an electric circuit employed to derive a telegraph (a.k.a. telegrapher) equation [

26]. Let us explain how this electric circuit is constructed in terms of electric potential

and electric current

from a generic perspective. From a narrower perspective of biological neurons, we can deal with the transmembrane potential and ionic current, respectively [

38,

39]. We assume that

flow from left to right.

Figure 3(a) shows an elemental domain over

, where

is the 1-D coordinate pointing to the right.

On

Figure 3(a), there are four electric components: [i] a resistor of resistance

, [ii] an inductor of (self-) inductance

[

3], [iii] a capacitor of capacitance

, and [iv] an electric shunt conductor of the (leak) conductance

(or the inverse of shunt resistance) [

38,

53]. They are also listed on

Table 3 for summary.

Both and are longitudinally arranged, while and are laterally extended. An electric substrate can be considered as an environment, whereas the four-element circuit can be taken as a system. In case with usual electric chips, the conductance is considered as an unwanted leakage from a system to an environment. In fact, the encapsulation of electronic chips on a substrate serves two purposes: [i] a mechanical bonding, and [ii] an electronic insulation with selectively local electric conductions.

In this sense, our droplet dispensers need to properly establish encapsulation of electric chips onto a substrate as indicated by the trajectory of a dispenser on

Figure 1(e). The electric conductance

would be the resistance between those chips and a substrate.

Conductance plays also a key role in the analysis of neuronal signal transmission [

25,

41]. In terms of a biological neuron, an axon is directed along the longitudinal

-direction, whereas a system normally implies the inside of an axon. The conductance

accounts for the ions undergoing Ohmic processes through the transmembrane channels that connect laterally the inside of an axon and the environment consisting of extracellular space (ECS) [

18,

48]. While an axon can be considered as a system, the ECS can be taken as an environment. Meanwhile, the notion of ‘environment’ began to appear in [

38].

From another viewpoint, a biological substrate can serve as an environment [

45]. The system-environment interaction (SEI) is enabled by the transmembrane ion channels that laterally straddle the membranes of an axon. The inside of an axon is normally modeled as a cylindrical tube, the radius of which is normally much greater than the typical radius of ion channels. In practice, the membranes separating the inside of an axon from the ECS can be considered as porous walls.

In this respect, waves propagating through cortical circuits in-vitro experiments are believed to arise from synaptic interactions and the intrinsic behavior of local neuronal circuitry. This fact gives another credence to the validity of SEIs considered in this study [

19].

The system consists of the resistor-inductor pair with

, while the environment is everything other than the system as illustrated on

Figure 3(a). Meanwhile, the capacitor-conductor pair with

serves as bridges between the system and the environment, which is called in this study a ‘system-environment interaction (SEI)’. On

Figure 3(a), both

of the system elements are serially connected, whereas both

of the SEI elements are arranged in parallel to each other.

Let us employ the symbol

for a physical quantity ‘

’. Because resistance

and conductance

are of inverse dimensions of each other, their product

is dimensionless [

17]. In

Appendix A, we have proved that the following three products are of the following dimensions, where ‘

’ is ‘second’ as a temporal unit.

It is worth stressing that the properties employed in this study are total values, which specify the off-the-shelf commodities available in stores selling electric components. In neuroscience, where the condition is mostly met, is called a ‘membrane time constant’ according to the dimension in equation (3).

For comparison with the data in literature, we define the per-unit-length properties

as follows.

Throughout this study,

is a certain constant length [

20,

25]. See

Appendix A for numerical data of

.

Meanwhile,

Figure 2(a) shows

as the string length measured in the

-direction. In general,

. The length

is missing in almost all open literature available these days [

20,

26]. We find notwithstanding that the introduction of

is necessary for setting up dimensionally correct formulas [

17].

The electric potential

undergoes reductions by

due to a system resistor and by

due to a system inductor. Meanwhile, the electric charge

stored on the capacitor is given by

. Therefore, the electric current through the capacitor is given by

as the time-rate of charge. Likewise, for the (leak) conductance

(or the inverse of shunt resistance [

38,

53], the electric current is given by

[

40]. It is crucial to notice that both leakage current components are directed from the system out to the environment. That is, we encounter two components

of leakage (or escape) currents.

Resultantly, both

and

are governed by the first-order differentials over the length increment

[

25].

Here, we have added external distributed sources for potential

and for current

that are directed from the environment into the system [

48,

53]. For instance,

is imposed by a patch electrode in neuroscience [

39].

Combining both relationships in equation (5) leads to the following pair of second-order PDEs [

1,

2,

26].

Here on the LHSs, the first terms

stand for dissipation, while the second terms

imply acceleration terms. On the right-hand sides (RHSs), the first terms

signify diffusion, whereas the second terms

refer to either leakage or forward reaction.

Such leakage is supposed to take place in the lateral direction as marked by the vertical double-headed arrow on

Figure 1(c),

Figure 2(a) and

Figure 3(a). Since equation (6) contains diffusion only the longitudinal

-direction, any lateral diffusion is not accounted for unlike the case in [

27]. It is natural that the terms on each relation in equation (6) are of the same dimension. Meanwhile,

is called a ‘membrane resistance’ especially for the term

appearing in equation (6) [

25].

When

in equation (6) is interpreted to be a flow velocity as on

Figure 2(b–d), the potential source

can be taken to be proportional to the pressure

, while

is proportional to a pressure gradient

. In this situation, the pressure

at the entrance to the syringe of a droplet dispenser would be the excitation function

depicted on

Figure 1(c). In this study, the current source can be set to zero, i.e.,

.

Let us define a ‘full leaky RLGC circuit’, where a circuit with

is differentiated from other circuits. A proper reference time

for a full leaky RLGC circuit can be established in two ways when comparing two pairs of terms in the generic telegraph equation (6) as follows.

Here, superscript ‘

’ and ‘

’ signify the orders of the participating differentials, respectively.

Therefore, the strength of the leakage term

can measured, in one way, by the above delay (or decay) time

in equation (7) [

4,

7,

19,

38,

53,

54]. The dimensionalities listed in equation (3) can be employed to verify that the delay times

carry indeed the dimension of time as shown in equation (7). Besides,

corresponds to

in equation (2].

Decay and delay are biologically plausible [

38,

48,

55]. The numerator

of

consists of two terms, where each term is a product of a system parameter and a SEI parameter. Even the denominator

of

is another product of the two.

For the desired reference time

, we can reconcile the two distinct reference times

in equation (7) by taking their geometric average in the following manner.

This process of logically deriving a reference time

has not been explicitly attempted elsewhere as far as we know. Since

as a dimension,

in agreement with the last formula in equation (3).

When source terms vanish, namely,

, equation (6) is reduced to the following source-free ‘generic telegraph equations‘ [

20,

23].

Here, the two source-free equations are decoupled. Therefore, we will henceforth treat the first relation for the electric potential

for convenience. The arrangement corresponding to equation (9) is schematically illustrated on

Figure 3(b).

Equation (9) can be considered as either [i] diffusion equations contaminated by propagating waves [

19], or [ii] wave equations contaminated by attenuation or damping [

22,

28]. Equation (9] is alternatively called a ‘propagative diffusion equation’ from the first viewpoint, whereas it is alternatively called a ‘damped wave equation’ from the second perspective [

5].

Equation (9) can be alternatively cast into the following more familiar form when divided by

[

26,

27].

Here, the conventional pair

together with the signal velocity

are defined. This equation is essentially identical to the simplified telegraph equation (2) valid for string vibration, except for the leakage term

on the RHS of equation (10).

As summarized on

Table 3, the ratios

is a property of a system, whereas

is a property of an SEI. Although these two ratios

have already been identified in [

26], their associations with a system and an SEI have never been properly entertained. Besides, both

and

belong to reactance.

Therefore, the product

on the RHS of the last term

in equation (10) is another manifestation of relative attenuation. In fact,

corresponds to losses due to displacement-dependent lateral force for string vibration, but not due to externally applied lateral load for string vibration [

37].

To cope with the pair

more systematically, let us examine their ratio

and the subsequent linear combination

as follows.

Let us find the range of

defined in equation (11) in the following manner.

Resultantly,

for

. Typical values of

are evaluated for exemplary data in

Appendix A [

20].

By means of the parameters defined in equations (11) along with the properties in equation (12), we thus find that the condition

is equivalent to the following alternatives.

Here,

have been introduced in equation (10). Therefore,

is equivalent to the equality

, which is called the condition for ‘distortion-less propagation (but still not attenuation-less)‘ by [

5].

Consequently, the condition

of distortion-less propagation does not hold true in the special data of [

56], which is experimentally measured for polyethylene insulated cable. A way of reaching the condition

is to increase

, which can be realized from the perspectives provided in

Appendix B.

In this connection, let us take the following ratio between the two reference times

and

presented respectively in equations (7) and (8).

Here,

is defined in equation (11).

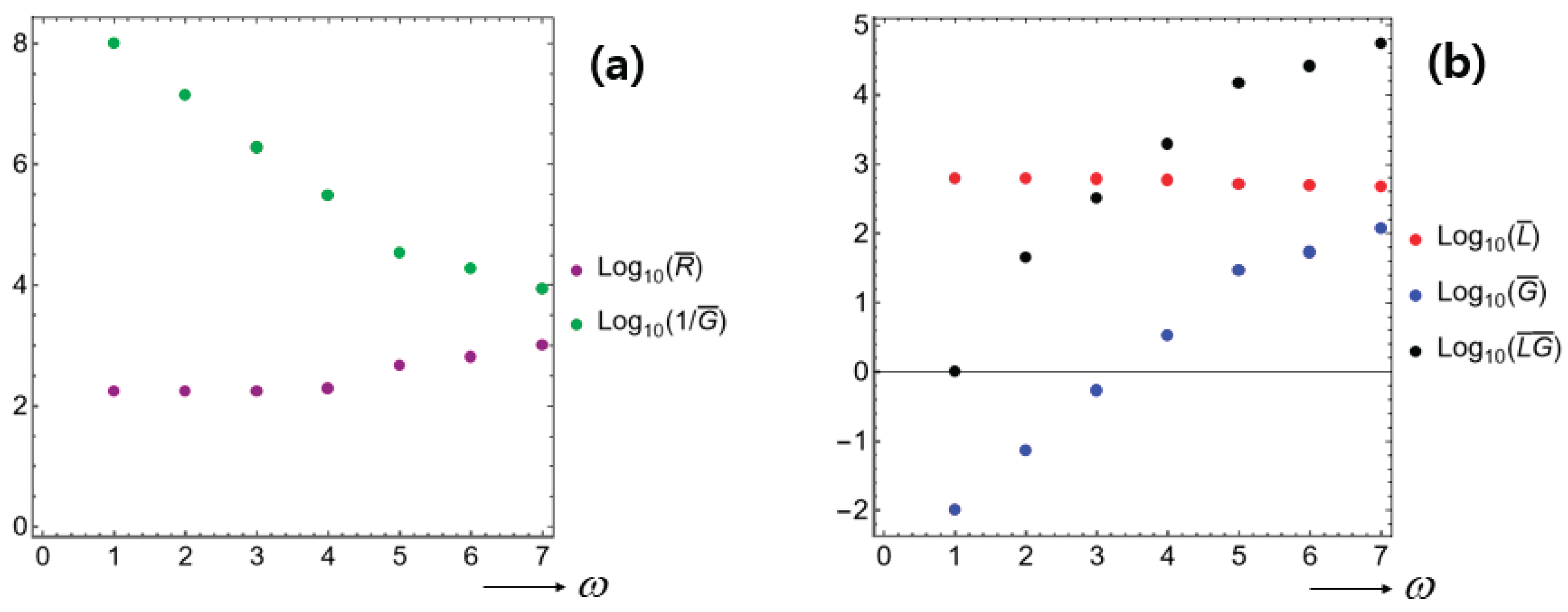

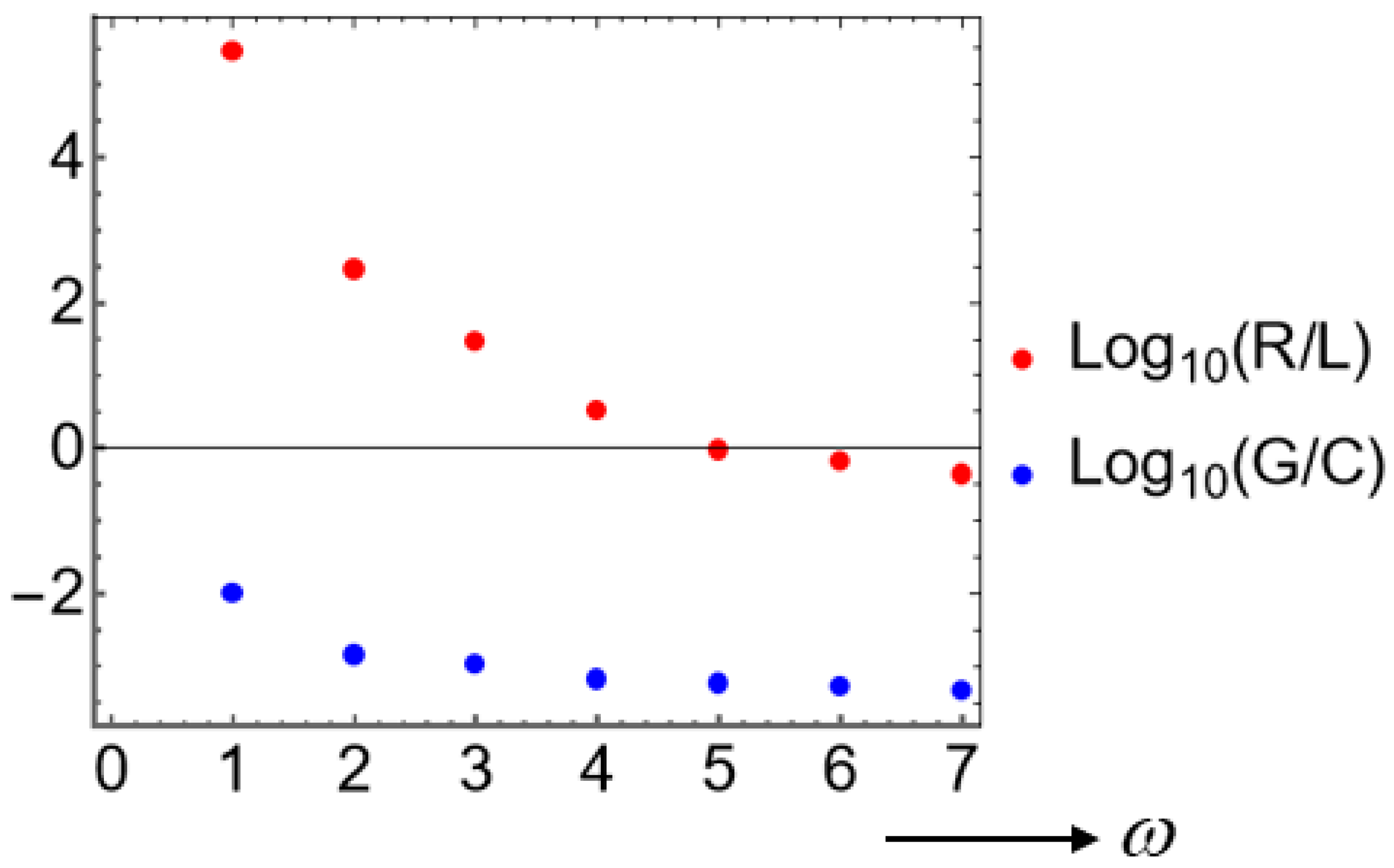

In this respect, let us compare the magnitude of

. To this end, we have drawn

Figure 4 based on the data of [

56], which are per-unit-length properties

introduced in equations (4) and (5). Hence,

and

. We find here that

approximately by two orders of magnitude.

Comparing equations (2) and (10), we ascertain the following correspondences.

In the spirit of introducing

in equations (4) and (5), the signal velocity

is employed throughout this study, where

in view of

in equation (3). In comparison, the formula

widely employed in most of open literature employs the per-unit-length properties

and

in terms of our notation [

26]. See

Appendix A, which employs the per-unit-length properties of [

20] for exemplary numerical evaluations.

It is crucial to notice in equation (15) that the tension

is directed along the length of a string, while

is the mass per unit longitudinal length [

12]. Let us interpret the correspondence

appearing in equation (15). The mass (inertia) per unit length carries the correspondence

, where the capacitance

per unit area

is understood as sort of electric inertance. The remaining correspondence

signifies the dynamical nature of both inductance

and string tension

.

Table 4 lists several relations reducible from equation (6).

As another easiest reduced case, consider the circuit with both internal-loss-free (

) and leak-free (

) properties. This wholly loss-free case is expected to cause no attenuation. In this case, the source-free generic telegraph equation (9) is further reduced to the following wave equation [

2,

12,

55].

We call this PDE the ‘canonical wave equation’ [

1,

2]. Additionally, it is super-important to keep a non-zero capacitance

and non-zero inductance

in this case. Here, we have introduced a reference ‘LC time’

, where the subscript ‘

’ implies that

. With reference to equations (15) and (16) for

,

according to equation (3).

Consider the following equation.

According to the four-element electric circuit depicted on

Figure 3(a), equation (17) is at most hypothetical, since

assumed for equation (17) requires that

in equation (6). However,

is impossible to achieve since

.

Although this hypothetical equation (17) is not reducible from equation (9) by taking any proper combinations of the parameters

, it shed light on further meaning of

. As listed on

Table 3,

is the product of the two relative losses that represent respectively a system and a SEI.

Equation (17) is a simple harmonic equation described by, say, Hook’s law. Here,

serves as an inertance (viz., effective mass) [

37], while

serves as an effective spring constant [

12]. In this perspective,

acts as a restoring force. Although the role of capacitance

as an inertance is well-known, the role of

as another inertance is less well-known.

The remaining special reduced case is the leak-free RLC circuit with

(but not with

), whereby the source-free generic telegraph equation (9) is reduced to the following [

4,

13,

22,

49].

Let us call this equation a ‘leak-free diffusion-wave equation’, since it exhibits both diffusion and wave phenomena. Notice that there is still a loss due to the non-zero system loss, namely,

. The absence of a leakage term

in equation (18) corresponds to missing forward-reaction, if equation (18) is interpreted as a reaction-diffusion equation [

38]. The arrangement corresponding to equation (18) is schematically illustrated on

Figure 3(c).

Meanwhile, according to

Figure 4,

for a certain material. Therefore, the leak-free RLC circuit with

is indeed an interesting limit case, identification of which is our own contribution.

Equation (18) has been derived by the analysis of two-dimensional (2-D) geometry in [

3]. In addition to the longitudinal refence length

, let

be the lateral reference length. It is assumed in [

3] that

and

under the approximation

. Resultantly,

, thereby getting in conformity with the expected dimension of

on the RHS in equation (18).

In this connection, both equations (9) and (18) are 1-D hyperbolic-parabolic second-order equations [

1,

2,

26], where wave propagations are implied by the adjective ‘hyperbolic’ and diffusion is implied by the adjective ‘parabolic’. The wave nature of the telegraph-like equations is what we are going to expand on in this study.

Let us reduce equation (6) into the following rotation-free (induction-free) leaky circuit with

[

17].

Hence, a wave-propagation feature is absent since

, whence the signal velocity

in equations (15) and (16) gets undefined. The PDEs in equation (19) are reaction-diffusion (a.k.a. diffusion-leak) equations, which are thus alternatively known as a ‘cable equation’ [

25]. Notice in equation (19) that the second-order time derivatives

and

are absent. The arrangement corresponding to equation (19) is schematically illustrated on

Figure 3(d).

The fact that the rotation-free leaky circuit with

is apparently free of propagating waves as in equation (19) is suggestive of the fact that a non-zero inductance (

) is instrumental to supporting propagating waves [

18,

46]. As another example, dual propagation velocities (of different magnitudes but of the same sign) could prevail without attenuation in case with soliton flows involving surface tension [

24].

In neuroscience, magnetic effects are normally neglected so that

[

48], albeit they are non-negligible in rare situations. Consider in equation (19) a special case that

but

for neuronal signal transmission. Furthermore, let us assume that

with

being a (spatially localized) delta function [

19]. When the temporal portion is modeled by

, where

is what is shown on

Figure 1(d). The resulting solution

sought over a semi-infinite 1-D domain

looks almost like what is presented in [

48]. Notwithstanding, these solutions in [

48] do not account for the termination stage involving drop ejection process [

19].

A multi-variable extension of equation (19) with proper forms of excitations

is well-known as a ‘leaky integrate-and-fire (LIF)’ model in neuroscience, where terms

are leakage terms [

19,

25,

36,

38,

39,

41,

42,

53,

54,

57]. In case with the LIF model, the current source

consists of either the sum or the integral from many other nearby neurons as depicted on

Figure 1(f) showing convergent trajectories [

19,

25]. Here lies the connection between the subjects of droplet dispersers handled in our study and multi-layered neural network.

A heavily investigated form of equation (19) is its source-free diffusion-leak (reaction-diffusion) equation with

as given below for an electric potential.

This special form of telegraph equation has also been extensively investigated as equation (19). This is also known as a ‘leaky heat equation’ [

5], for which a heat-transfer aspect of the product

is described in

Appendix C [

58].

We can define from equation (20) the ‘RC time’ by comparing the two terms and . The dimension from equation (3).

4. Derivation of Three-Dimensional (3-D) Telegraph Equation

As the last issue of the PDE, the telegraph equation (10) can be extended into 3-D space as follows in terms of conventional notation.

Here,

introduced in equations (15) and (16). In addition, the

-coordinate is along the longitudinal direction as marked by the horizontal double-headed arrow on

Figure 1(c),

Figure 2(a) and

Figure 3(a). Therefore, the

-plane is a lateral plane, being perpendicular to the longitudinal

-axis. Besides, any radial direction on the

-plane is a lateral direction. For equation (21) and the following relevant treatment, we closely follow [

27].

Let us introduce below several parameters.

Here,

form a complementary pair of characteristic curves, which stands for propagating waves [

2]. Besides,

is a real constant.

The solution to equation (21) assumes the following Ansatz of product form [

57].

We are looking for a solution in the following special form.

This special form is satisfied for the parameters defined in equation (22), which help eliminate the term proportional

in equation (24) as intentionally indicated by

. This missing

-term is indicative of leakage, the elimination of which corresponds to introducing an integrating factor for a differential equation as in [

48].

Equation (24) is now handled with a method of separation of variables, thereby resulting in the following equation [

2,

52].

This special form is satisfied for the parameters defined in equation (22).

Equation (25) can be solved to provide a solution, whence the solution to

can be further constructed according to equation (23).

Here,

is yet another pair of constants.

Meanwhile, is the Airy function. Since Airy function is either sinusoidally attenuating or uniformly attenuating with increasing magnitude of its argument, the solution in equation (26) properly account for the spatially evanescent waves in the lateral direction as . In this connection, notice in equation (24) that the sum represents the diffusion on the lateral -plane.

Of course, there are both forward waves implied by

and backward waves implied by

in the solution presented in equation (26) [

19,

46]. Since equation (21) is symmetric in

, we can easily come up with another equation involving

instead of

in equation (24) by replacing

with

in equation (21).

Both equations (20] and (25) are diffusion equations, where the longitudinal characteristic variable in equation (25) is time-like. As regards equation (9), we have already pointed out that telegraph equations harbor both features of diffusion and wave propagation.

A Cauchy problem for the diffusion-leak equation (19) has been solved with an appropriate set of side conditions early in 1946 by [

48]. Although that diffusion-leak equation does not explicitly contain wave-propagation terms, the resulting solution in [

48] contains implicit wave-propagation factors. Notwithstanding, the associated characteristic curves in [

44] are not of the form

but of nonlinear form in

.

Notice furthermore that

in equation (23) serves as sort of envelope function, which takes a slightly different form in [

48] as well. In addition, it is worth recognizing that

in equation (26) shows itself up not only in linear form but also in squared form.

Meanwhile, diffusion in equation (26) is manifested mostly by the Airy functions. In comparison, wave propagation is manifested by the two characteristic curves of , that appears not only in the Airy functions but also in the exponential function.

For a 1-D problem, equation (24) becomes

, thus giving rise to a trivial solution

for equation (23). For this 1-D problem, the solution in equation (26) is reduced to the following.

In comparison, the simplest wave equation

in equation (16) admits a generic solution in the form of D'Alembert formula

[

1,

2]. Here,

are certain differentiable functions, while

are certain constants depending on appropriate side conditions [

4]. Consequently, the amplitude ratio between the forward waves with

and the backward waves with

will depend on the appropriate side conditions at hand [

19].

5. Derivation and Analysis of Dispersion Relations

We mean by resonance the source-free conditions

, for which the generic telegraph equation (9) is employed. Moreover, the wave amplitude on resonance is undetermined [

46,

57]. In this situation, in equation (9) are decoupled so that let us consider henceforth only

.

Consider the Ansatz

for propagating waves over the infinite domain

. Here,

denotes an imaginary unit such that

. In addition,

and

are temporal frequency and spatial wave number, respectively [

46,

63]. As an aside,

is called an ‘eikonal’ [

63]. For example, small lateral displacements of a hollow tube in dynamic states as mentioned in section 2 guarantee the applicability of the above Ansatz

[

8,

10].

There are two kinds of approaches to handling the propagation factor

[

12]: [i] the spatially attenuated and temporally periodic (SATP) approach [

10,

20,

22,

46], and [ii] the temporally attenuated and spatially per

iodic (TASP) approach [

11,

20,

63]. In brief,

Here,

and

denote the real and complex spaces, respectively. Besides, the subscripts ‘

’ and ‘

’ denote the real and imaginary parts, respectively.

From our detailed study, the overall characteristics of the SATP approach turn out to be quite different from those of the TASP approach. The relevant algebra for the SATP approach is largely more complicated than that for the TASP approach [

22].

With the TASP approach, we let

be complex while keeping

real, viz.,

and

. With this TASP approach, problems valid over a finite 1-D domain such as on

Figure 2 are easier to handle. One reason is that BCs at both ends are easier to specify [

10,

13] so that relevant boundary-value problems (BVPs) are easier to handle with the TASP approach.

With the TASP approach fully adopted, we have found many interesting phenomena. Among others, we rediscovered the well-known dual (double) attenuation rates for non-propagating stationary waves in addition to propagating waves [

10,

24,

46,

57,

60]. Notwithstanding, finite-domain 1-D problems will be examined in a forthcoming publication, since the analysis is rather tricky. It is because several key findings such as cutoffs and crossovers would depend on the types of applicable side conditions.

In comparison, one of the advantages of the SATP approach in comparison to the TASP approach is the fact that temporally imposed functions such as displayed on

Figure 1(d) can be easily resolved by way of, say, Fourier transform in

with respect to

.

Let us focus more on the SATP approach, for which we let

be complex while keeping

real [

10,

49].

Here, the inequality

leads to the restriction that

. Furthermore, notice that

is the longitudinal wave number (a.k.a. propagation constant) directed along the longitudinal direction as marked by the horizontal double-headed arrow on

Figure 1(c),

Figure 2(a) and

Figure 3(a).

With

, we are looking for the existence of traveling waves [

57]. Meanwhile, let us examine the propagation factor

in more detail. On one hand, suppose that

, whereby

implies waves propagating into the positive

-direction. Wave stability requires that

as it progresses in view of the spatial-attenuation factor

[

11,

13,

20,

22,

57,

63].

On the other hand, suppose the opposite case that

, whereby

implies waves propagating into the negative

-direction. This negative propagation should carry

. In brief, we should have

in any case. The cases

and

are henceforth defined to correspond respectively to forward (propagating) waves and backward (propagating) waves. This way of interpreting the two cases

and

was exactly what has been adopted in [

48].

Let us summarize below these two waves.

Telegraph-like equations and their solutions offer far-reaching applications in both mechanics and electric circuits. Suppose that the reaction-diffusion (or diffusion-leak) equation (18) is slightly modified by the addition of wave-propagation features exhibited by telegraph-like equations. Such slight addition would give rise to both forward and backward wave propagations as classified in equation (30) [

25]. Here lies a possibility of arousing slight backpropagation in the characteristics exhibited by the conventional diffusion-leak equations [

42].

Meanwhile, with this SATP approach, we could discover spatially evanescent modes if they are circumstantially admissible as discussed in the preceding section 4 [

10]. In the sequel publication, our focus will be laid on how strong forward waves are in comparison to backward waves [

19].

When the Ansatz

in equation (29) is substituted into the source-free generic telegraph equation (9) [

10], the following dispersion relation

is obtained in two equivalent forms [

22,

46].

The arrangement corresponding to equation (31) is schematically illustrated on

Figure 3(b).

It takes us by surprise that the generation of double (dual) attenuation peaks is hinged upon the resonance coupling between longitudinal and transverse (viz., lateral) resonators in the context of metamaterials consisting of simultaneous mass and stiffness [

46]. In this regard, it is shown in [

46] that the dual (double) attenuation rates carry two distinct contributions: [i] one rate stemming solely from system parameters that act in the longitudinal direction, and [ii] the other rate stemming from SEI parameters that account for both longitudinal and lateral dynamics.

It is rather disappointing to us that such a distinction made between a system and an SEI has not been explicitly recognized in [

46].

Likewise, the dispersion relation

in equation (31) exhibits a perfect symmetry between

and

so that the longitudinal system dynamics (represented by

) lies in interaction with the lateral SEI (represented by

). Moreover, in the interpretation by Hooke’s law in equation (17), the product

(

from a system and

from an SEI) serves as a mass and the other product

(

from a system and

from an SEI) acts as stiffness. See

Table 3 for a summary in this respect.

At this juncture, let us introduce the following set of reference quantities

and corresponding dimensionless parameters under the assumption of

for a full leaky RLGC circuit.

Here,

are dimensionless time and 1-D coordinate, respectively, while

are dimensionless frequency and wave number, respectively.

As the most easily conceivable reduced case [

19], the full leaky RLGC circuit with

as illustrated on

Figure 3(a) becomes a leak-free RLC circuit if

and

for which equation (18) holds true [

49]. Let us examine the dispersion relation for this leak-free RLC circuit by setting

in the generic equation (31) as follows.

This circuit with

corresponds to an ideal perfect insulator, for which the shunt resistance

becomes infinite [

49]. Part of the reason why we examine this leak-free RLC circuit is the property

as displayed on

Figure 4. The arrangement corresponding to equation (33) is schematically illustrated on

Figure 3(c).

As we did in equation (32), let us introduce a new pair

of references and corresponding dimensionless parameters under the assumption of

and

for a leak-free RLC circuit.

Here, the tilde ‘~’ is employed as an overbar. Hence,

are dimensionless time and 1-D coordinate, respectively, while

are dimensionless frequency and wave number, respectively.

It is appropriate to examine the special ratio

previously introduced in equation (34) in the following way.

Here,

is the RC time previously defined in equation (20). Moreover, the reference-time ratio

appearing in equations (34) and (35) complements the previously introduced ratio

in equation (14).

Here, the reference time

is identifiable also from equation (18) as another ratio

in [

22]. Besides,

is alternatively called ‘an inverse of bandwidth’. In addition,

has been identified in the context of interelectrode electric potential [

49]. From mechanics viewpoint,

is linked to viscous air resistance exerted on a vibrating string as illustrated on

Figure 2(a).

In the meantime, the signal velocity

employed in the simple wave equation (16) is linked to the following parameters respectively for the full leaky RLGC circuit and the leak-free RLC circuit.

Here, reference times and reference lengths are read respectively from equations (32) and (34).

Meanwhile, equations (31) and (33) are reduced to the following dimensionless forms respectively of

and

Here, the parameter

has already been defined in equation (11) with attendant properties in equation (12).

We have started with the four parameters

in the PDE (9), which are readily reduced to two parameters

in the PDE (10) [

20]. We have identified in equation (37) that

depends solely on a single parameter

. Even better is the fact that

is parameter-free.

Meanwhile, we resort to the following generic solution to

for a generic

[

49].

When this formula is applied to equation (37), we obtain the following pair of solutions

and

[

49].

Notice here that

, while

according to equation (29). Hence, the condition

in equation (30) is satisfied. According to the generic formula in (38), the other solution

is acceptable as well since

. Therefore, we will stick to the solutions presented in equation (39) to fix the idea. Likewise,

with

.

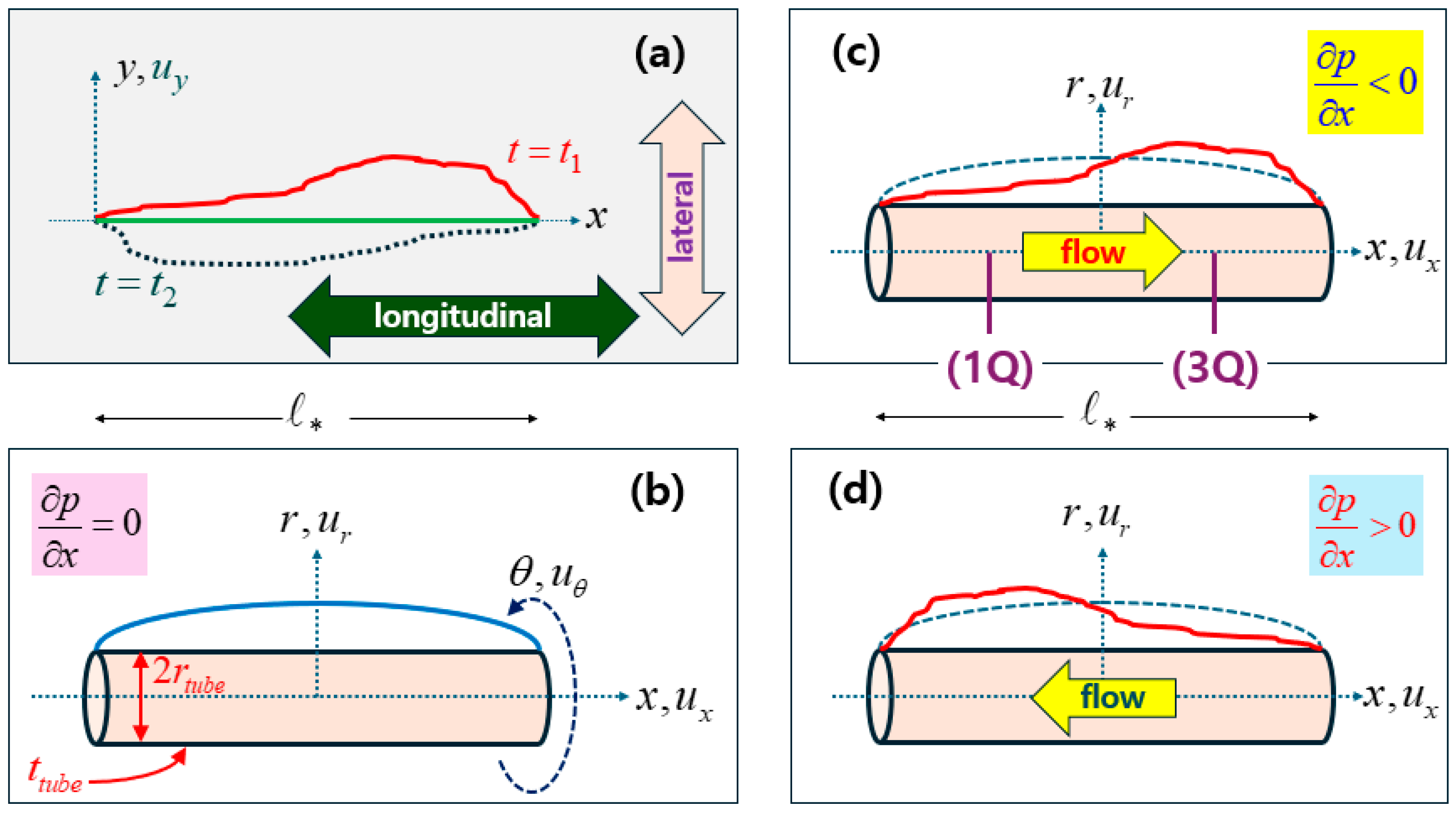

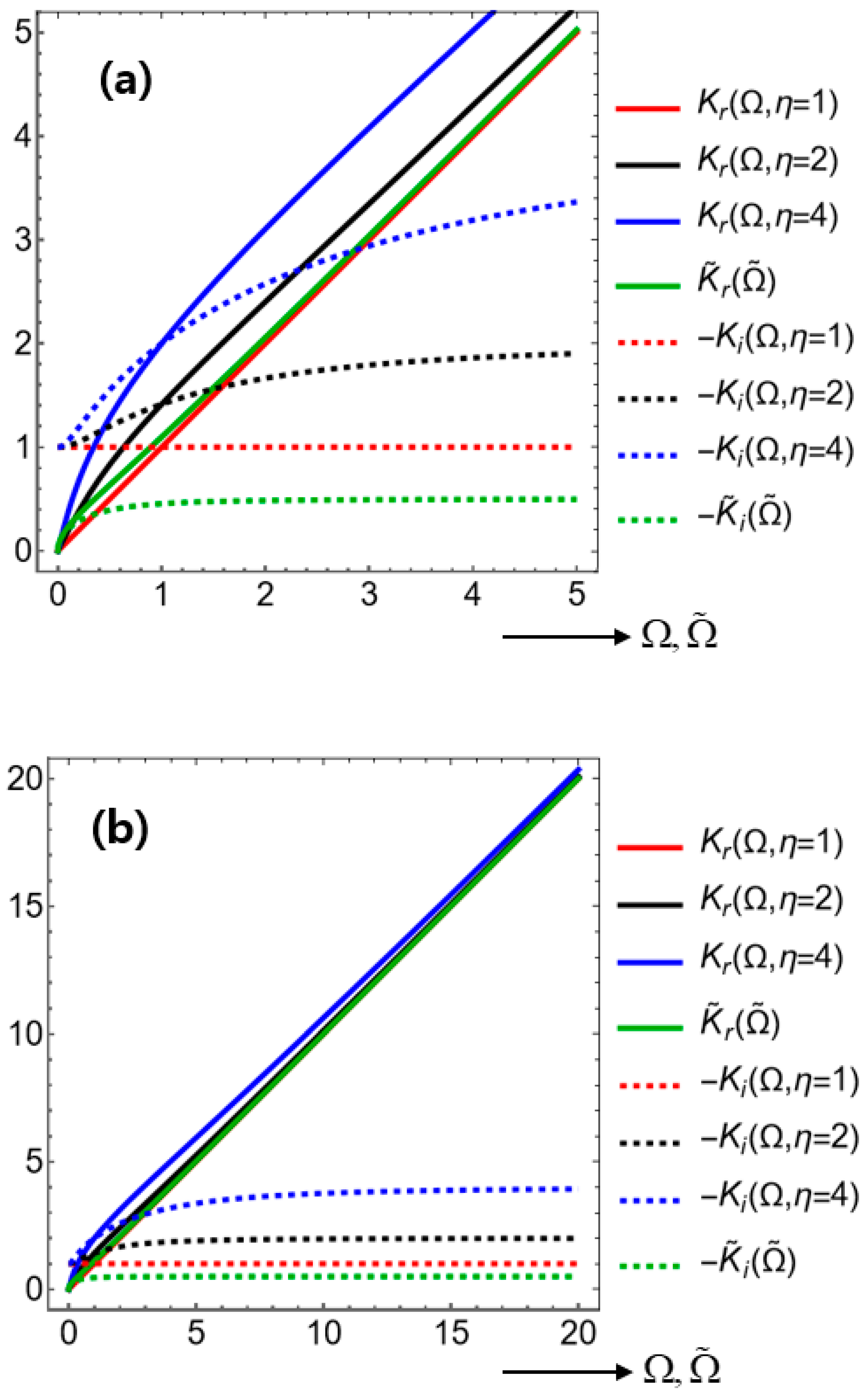

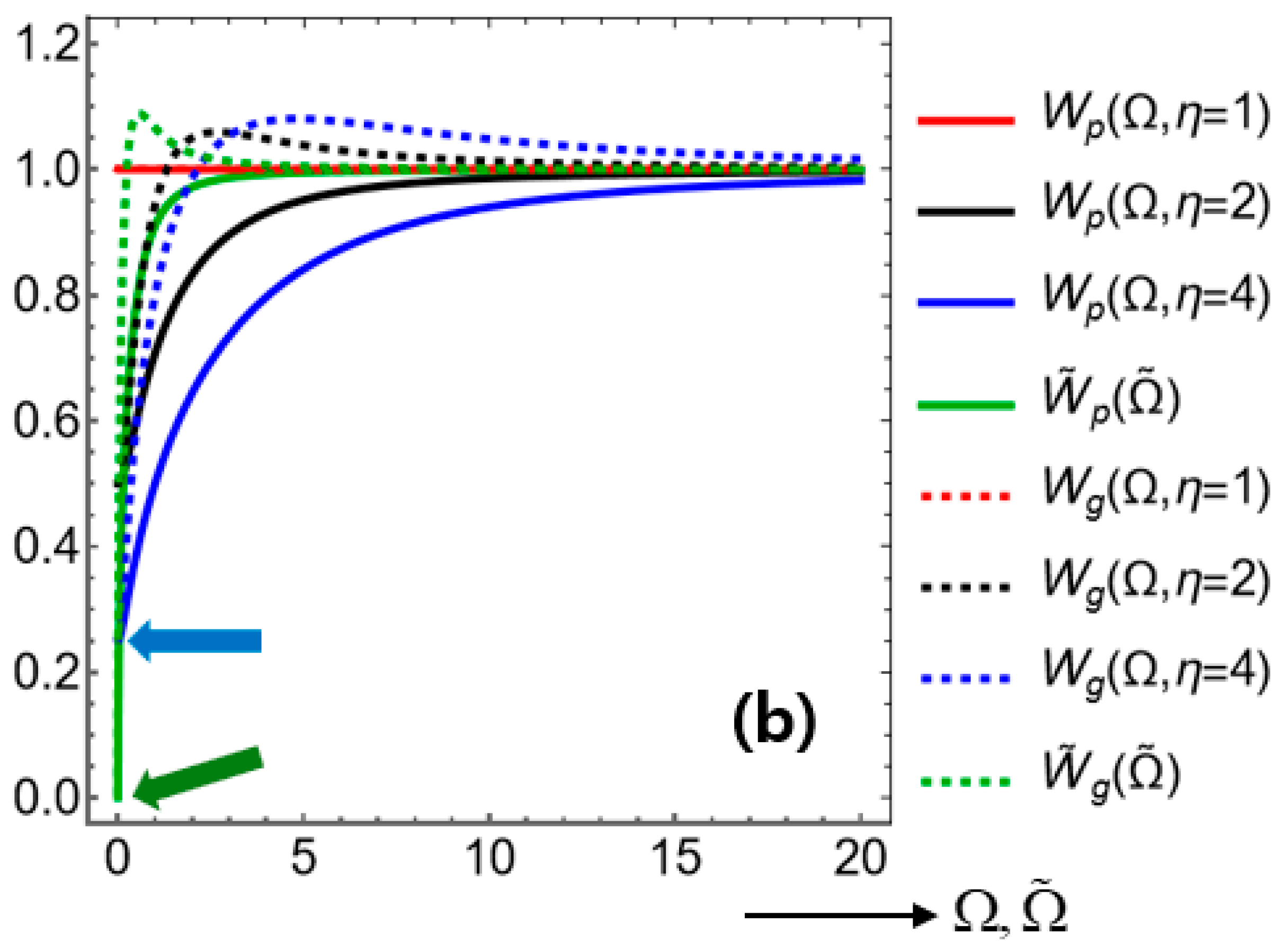

Figure 5(a) displays two kinds of curves on the same display panel: [i]

and

in case of the full leaky RLGC circuit, and [ii]

and

in case of the leak-free RLC circuit. In addition, solid curves are drawn for the wave number or propagation constants

and

, while dashed curves are drawn for the attenuation rates

and

.

Figure 5(a) is a zoomed-out version of

Figure 5(a).

On one hand, let us examine the real parts and on solid curves. Both and are increasing with respective increasing frequencies. Meanwhile, notice from equation (12) that . In this connection, does not appear to be obtainable either from the limit or from the limit of . It is because the curve of lies between the curve of and .

On the other hand, let us examine the imaginary parts

and

on dashed curves. Once again,

does not appear to be obtainable either from the

limit or from the

limit of

. One aspect of these discrepancies is the following small-frequency limits as seen from equation (39).

Therefore, only is non-zero for any over , while other small-frequency limits vanish. These small-frequency limits and for any values of can be alternatively called ‘stationarity limits’ instead. These stationarity limits exhibit a significant phenomenon, since stands for non-propagating stationary state, which still undergoes spatial attenuation due to .

Recall that

in the limit

as shown in equation (40) by the SATP approach. We have carried out a separate analysis via the TASP approach (to be separately published) to find that

in the limit

is also achieved. Notwithstanding, we learn from the TASP approach a new phenomenon that there is a certain finite low-

zone

where

. The TASP approach also revealed bifurcation phenomena for attenuation rates as well [

19,

57]. Such a finite forbidden wave-number zone cannot be seen via the current SATP approach. However, the significantly distinct behaviors between

and

in equation (40) are the symptom of the existence of such forbidden zones.

For the full leaky RLGC circuit, the following limits hold true for

from the equation (39).

Therefore,

is a straight line, while

is a constant horizontal line as displayed by the red curves on

Figure 5.

In brief, the curves of

and

exhibit rather distinct features in comparison to those of

and

. Especially, stationary non-propagating states do not appear to exist for the leak-free RLC circuit. The reason may be ascribed to the absence of dissipative SEIs for the leak-free RLC circuit with

, namely,

and

[

57].

This absence of stationary non-propagating states leads us to ask a self-question: “When an electric circuit is sufficiently insulated from an environment and hence an electric grounding is almost perfect, would then electric waves almost be always propagative rather than stationary?”. If this question were affirmatively answered, we might conjecture that ACs (alternating currents) will be better propagative through telegraph transmission lines than DCs (direct currents).

With reference to

Figure 3(a),

Table 5 makes comparison of several dispersion relations and corresponding key characteristics for the full leaky RLGC circuit with

and other reduced circuits. Notice the reference length

is undetermined. With a certain reference time

, the ratio

becomes a reference velocity.

In the meantime, the phase velocities

and the group velocities

are evaluated from equation (39) respectively via the following formulas [

20,

24,

46,

49,

63].

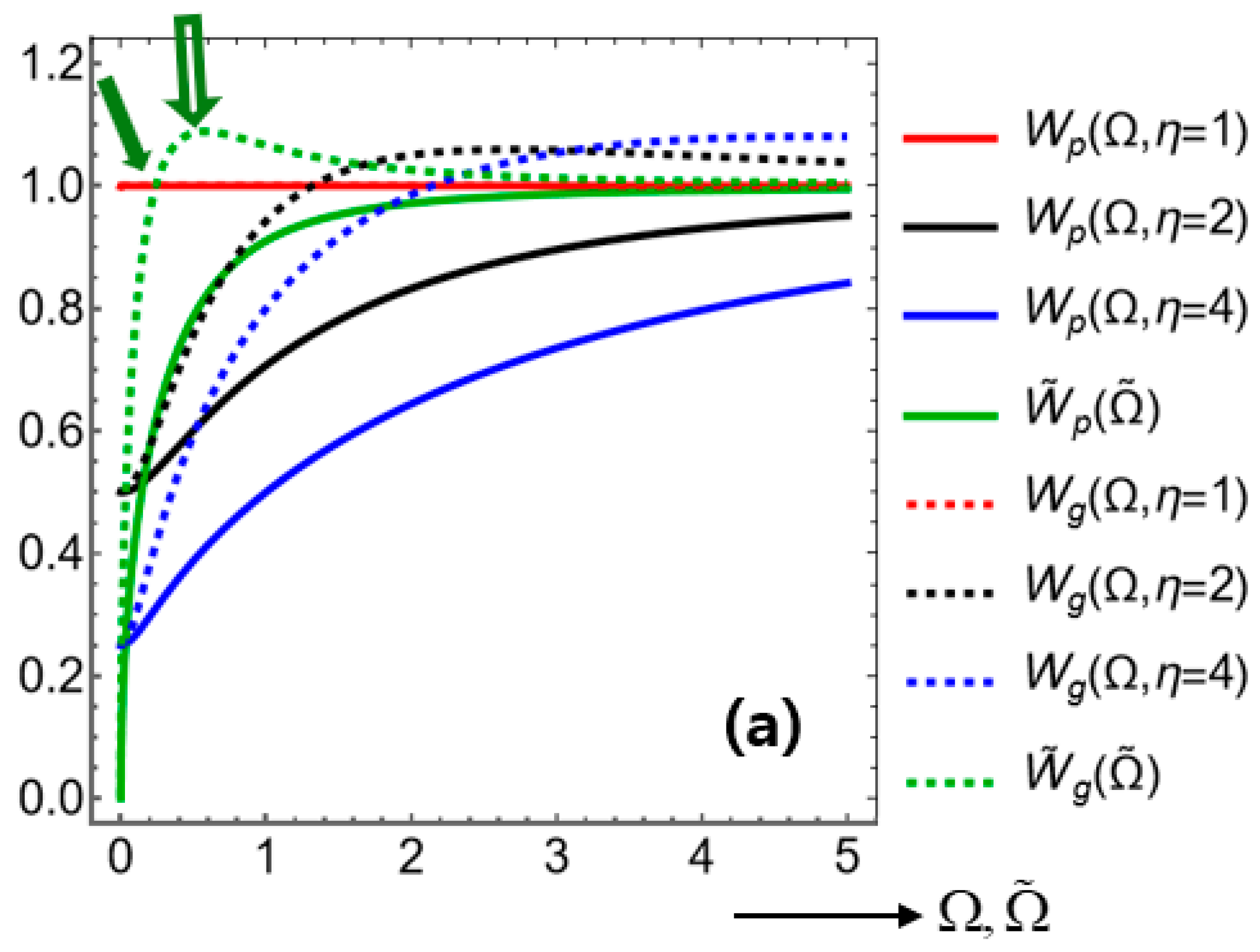

Figure 6(a) displays two kinds of curves on the same display panel: [i]

and

for the full leaky RLGC circuit, and [ii]

and

for the leak-free RLC circuit. Here,

and

are phase velocities displayed on solid curves, while

and

are group velocities shown on dashed curves.

Overall, all solid curves increase uniformly with increasing frequencies, while all dashed curves exhibit local maxima at certain frequencies. For instance, a local maximum is pointed to by the green blank arrow on

Figure 6(a) for

. Such a maximum feature in the group velocity is not uncommon [

49].

The curve of indicates a luminal phase velocity. All other phase velocities stay subluminal. In case with phase velocities, the inequality holds true over most of higher frequency zones except near zero frequency. However, such comparison between is not to be trusted due to distinct reference quantities listed in equations (32) and (34).

Each curve of group velocity exhibits a single crossover across the horizontal luminal line, e.g., as indicated by the green filled arrow on

Figure 6(a) for

. In other words,

(subluminal) over

, while

(superluminal) over

. Here,

is a certain constant. Likewise,

(subluminal) over

, whereas

(superluminal) over

. The critical frequency

appears to increase with increasing

[

19]. Besides,

also displays a local maximum with respect to

as clearly seen on

Figure 6(b).

We can easily evaluate the zero-frequency limits of the phase and group velocities as follows based on equation (42).

We can confirm these limits easily on

Figure 6(b). For instance,

as indicated by the horizontal solid blue arrow on

Figure 6(b). Also indicated by the green arrow near the coordinate origin is the limit

. In addition, we have anomalous dispersion, namely,

for

and

for all cases.

Meanwhile, consider the rotation-free leaky circuit with

and

as presented in equation (20). This circuit is devoid of wave propagation, since it is just a diffusion-leak equation. Therefore, the Ansatz

is not applicable. Yet, let us continue to perform the following analysis of dispersion relation to see what kinds of difference exist between diffusion and wave propagation.

Here,

on the RHS is linear in

, while

’s on the RHSs of both equations (31) and (33) are quadratic in

. This difference will lead to quite distinct behaviors of the respective dispersion relations. The arrangement corresponding to equation (44) is schematically illustrated on

Figure 3(d).

Furthermore, let us handle the rotation-free (induction-free) leaky circuit with

and

as presented in equations (20) and (44) to prepare the following.

Here, we have introduced a ‘caret’ notation for this circuit. Additionally, we have introduced additional reference quantities

. As discussed for

Figure 4,

, while

is dimensionless as discussed in

Appendix A.

We have examined in equation (36) whether the reference velocities and are equal to the well-known signal velocity . Therefore, making such comparisons with the help of in equation (45) turns out futile, because is undefined with . Therefore, conventional discussion in terms of subluminal, luminal, and superluminal states will become unfounded.

However, we can go on to find the dimensionless dispersion relation as follows based on equations (44) and (45).

Here, we have applied the square-root formula in equation (38), to explicitly find

and

as we have done in equation (39).

Based on equation (46), let us find the following pair of phase and group velocities as in equation (42).

Hence, we can easily come up with the following limit behaviors.

Here, the limit

requires a bit of care in its derivation.

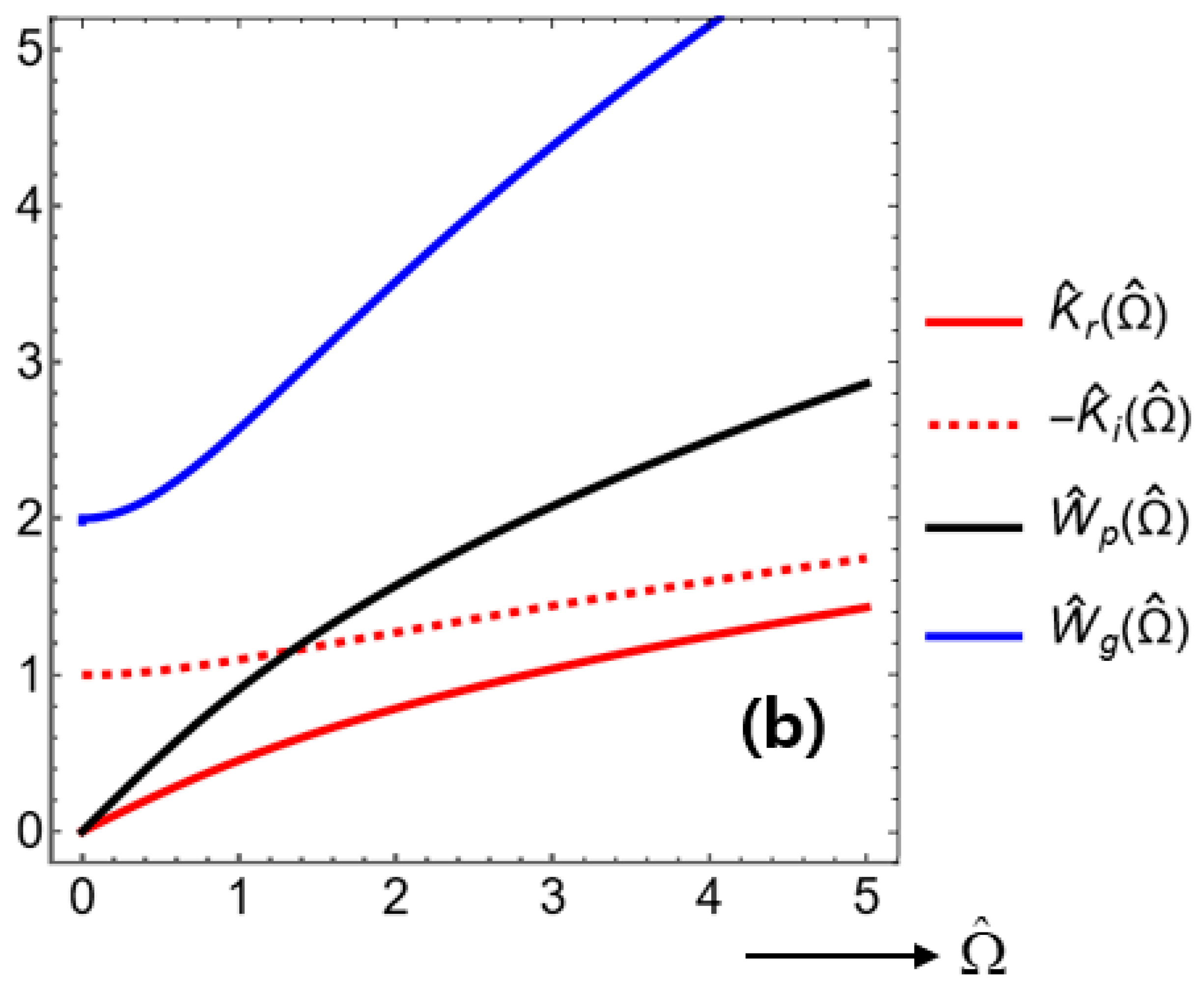

Figure 7 displays the dispersion characteristics

against the dimensionless frequency

. All members of

increase uniformly with increasing

without limits.

Notice that equation (20) is a diffusion-leak equation, thereby being endowed with no wave propagation. Therefore, both going without bounds as is indicative of infinite propagation velocity of signals especially for high frequencies. Such infinite propagation velocities are in conformance with, say, thermal heating being sensed instantly everywhere no matter how those senses are infinitesimally small. It is because governing equation for temperature is analogous to equation (20).

In mathematical languages, activities of parabolic PDEs carry infinite signal velocity. In comparison, hyperbolic PDEs such as in equations (9) and (18) are accompanied by finite propagation velocities as examined not only in equation (42) but also on

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 [

1,

2].

Such infinite propagation velocities are also in agreement with the finite group velocity in equation (48) at a stationary state. It is because a group velocity is sort of energy-transmission velocity, by which wave energy is steadily supplied for all temporally neighboring transient states of non-zero frequencies. The non-zero finite attenuation rate in equation (48) at a steady state also agrees with such energy transfer in low frequencies beginning with zero frequency.

A further reduction of the case with

is that

for the rotation-free and leak-free circuit. For this circuit, equation (31) is reduced to provide the following.

Here, we have introduced yet another set of notations

with inverted arc.

Moreover, a new reference time

is defined. This time

is deducible from equation (33) such that it been conventionally called an ‘RC (membrane) time’ in the context of neuroscience [

38,

39] and diffusive memristors [

43]. This nomenclature is made in comparison to the LC time

inequation (16), which is also easily deducible from equation (33) on dimensional ground.

Furthermore, we have pointed out that the absence of in equation (49) leads to a different signal velocity as for the rotation-free laky circuit discussed in equation (45).

We can easily find the solution to

in equation (49) as follow by way of the generic formula in equation (38).

Here, the solution

led easily to the corresponding phase and group velocities given above. Resultantly, both phase and group velocities are constant with respect to the non-dimensional scheme provided in equation (49).

Starting with equation (31), we process for the internal-loss-free and leak-free circuit with

and

to obtain the following.

These results are simpler than those in equations (49) and (50). The linear dispersion relation

is what we have discussed in equation (16) for the canonical wave equation.

In this case, we end up with the ratio

, thus being the signal velocity introduced in equation (16). Resultantly, both phase and group velocities are luminal for all frequencies.

6. Response Functions of Single Four-Element Electric Circuits

Let us consider another leaky circuit consisting of four discrete electric elements

with

.

Figure 8 illustrates two distinct circuit arrangements, which are variants of the full leaky RLGC circuit displayed on

Figure 3(a). Both arrangements in

Figure 8 share the same pairs of SEI components, namely, a capacitor with

and a conductor with

that are connected in parallel to each other. This

subcircuit is then linked to a system consisting of an inductor with

and a resistor with

. The difference is that

and

within a system are connected in series with each other on

Figure 8(a), while they are arranged in parallel to each other on

Figure 8(b).

See equation (4) for the relationships between dimensional and dimensionless parameters. While the per-unit-length properties

are appropriate for the continuous electric circuit on

Figure 3(a), the total properties

are certainly appropriate for the discrete electric circuit on

Figure 8.

For each configuration, our goal is to find the (frequency) response function

, being the ratio of the output electric potential

against the input electric potential

. Here,

is a common ground potential, being held constant [

38]. For simplicity, we neglect any spatial dependences unlike the case with

Figure 3(a) so that only temporal dynamics will be considered. We thus do not need a reference length

here.

In addition, notice that the two SEI elements

carry electric currents

, respectively. According to Kirchhoff’s circuit law of conservation of electric currents, we have

. Hence, the following pair of relations hold true [

38].

Here, we have applied the Ansatz

for temporal periodicity of dynamics.

Let us make analysis of the serial system shown on

Figure 8(a) as in equation (53).

Combining

in equation (53) and

in equation (54) leads to the following response function.

Let us turn to the parallel system displayed on

Figure 8(b) as follows by way of

, being different from equation (54).

Combining

in equation (53) and

in equation (56) leads to the following response function for the parallel system.

Meanwhile, let us invert

in equation (11) as follows.

Therefore,

is doubly valued in

. Hence, it will be better to employ

whenever both of

show up in the forthcoming formulas.

Let us make dimensionless both complex response functions

(for serial system) and

(for parallel system), respectively in equations (55) and (57) as follows [

19].

Here, we have employed the following intermediate relationships based on the various parameters presented in equations (11) and (32).

Notice again that the product

is dimensionless as provided in equation (3). This way of comparing serial and parallel circuits is crucial to properly assessing the performances of electrical devices useful in practice [

62].

Normally, what we need are the following magnitudes.

Large-

limits are easily found below.

Hence, the serial system exhibits an inversely linear behavior with respect to

, while the parallel system exhibits an inversely quadratic behavior with respect to

.

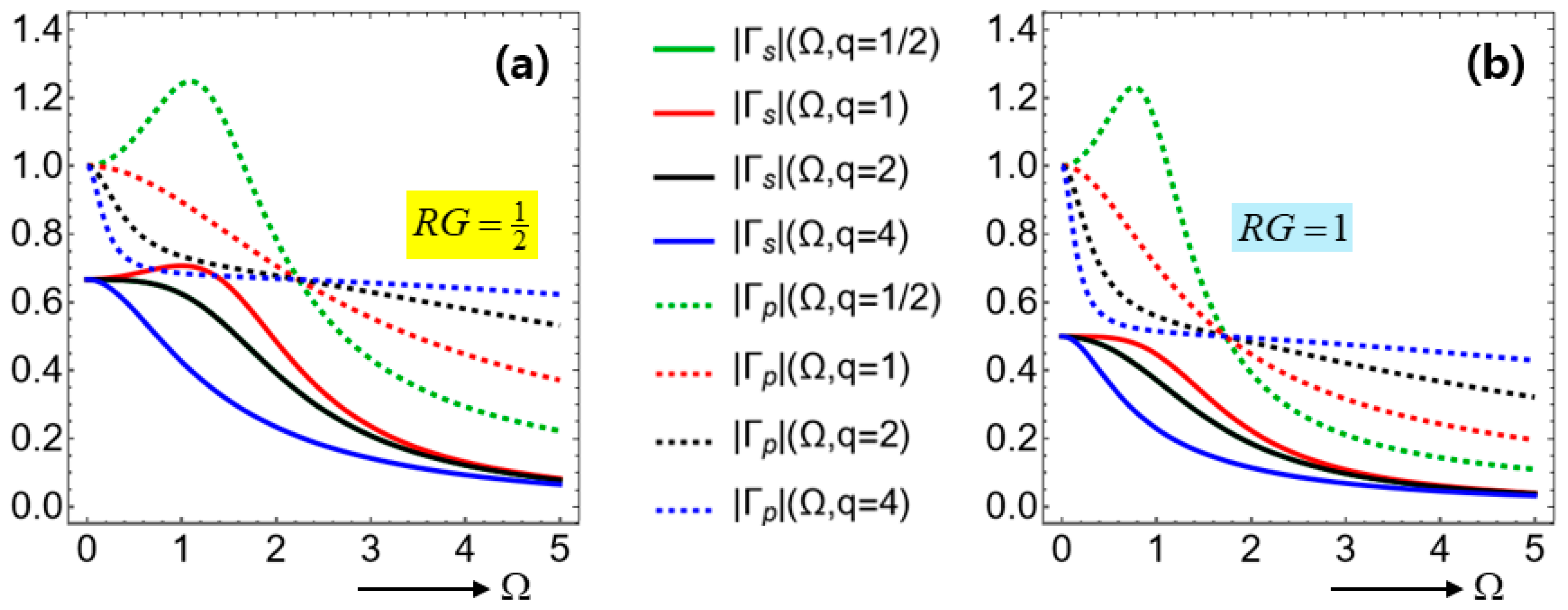

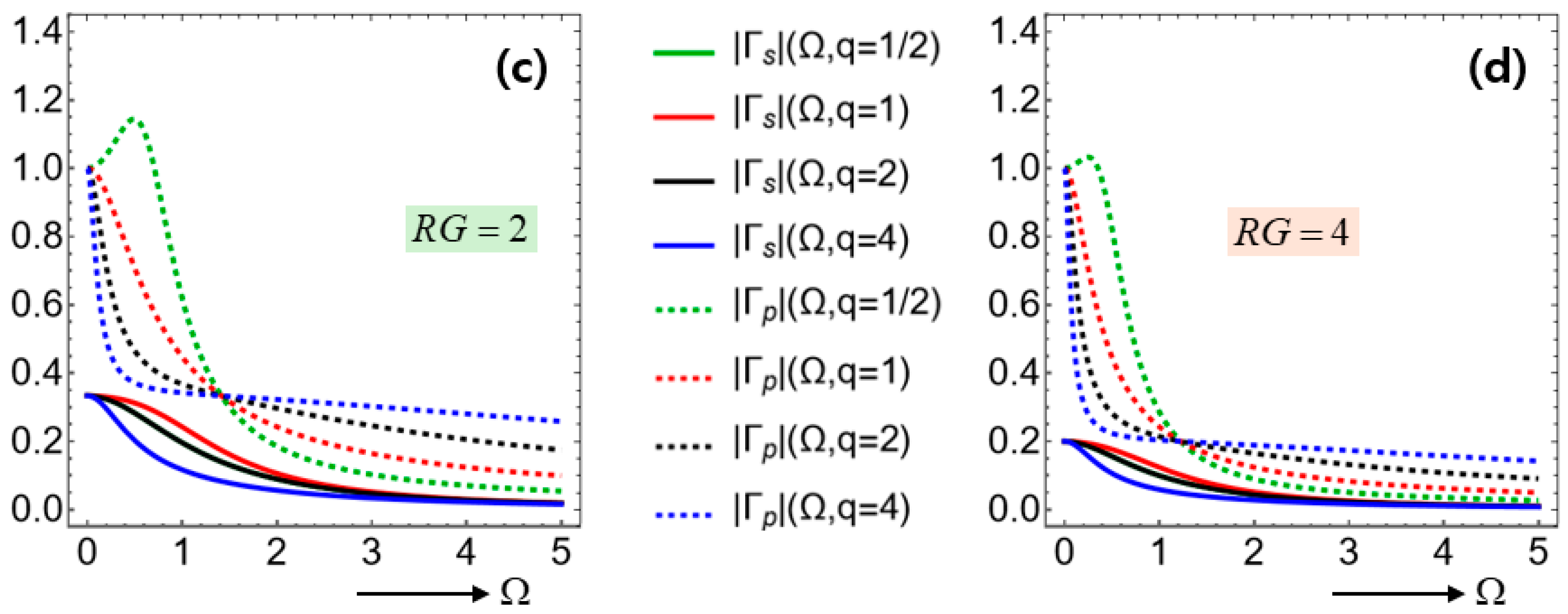

Figure 9 shows the magnitudes of response functions

plotted against the dimensionless frequency

for varying values of

. For a given value of

, each subfigure displays that

over all range of

. In words, a parallel system undergoes a less potential drop than a serial system while the SEIs remain the same.

Most of the response functions exhibit maxima at zero frequencies (namely, static states), thus standing for low-pass filters [

10]. One exception is the dotted green curves for

with

, where a maximum takes place at a non-zero finite

. Other curves of red, black, and blue colors exhibit uniform decreases with increasing

. Besides, the curves of

are identical with those of

thanks to the factor

appearing in equation (61).

The four subfigures of

Figure 9 show that the high-frequency components are especially damped with increasing

as also observed by [

38] in their numerical solution with a LIF model. Leakages help a system under consideration to become robust (namely, stable) against perturbations although leaks are incurred [

57].

In this regard, consider a temporally periodic function where each cycle consists of two step changes and a flat period in between, followed by a dormant period as displayed on

Figure 1(d). Suppose further that such temporal discontinuities are resolved into various frequency components according to Fourier decomposition [

62]. In view of Gibbs’ phenomenon for such a decomposition, there appear unwanted high-frequency components that get stronger across discontinuities [

31]. The low-pass (temporal) filter as shown on

Figure 9 dampens faster-oscillating components by greater amount than slower oscillating components [

25].

In this respect, the large-

behaviors in equation (62) are also visible on

Figure 9, where stronger temporal attenuations with increasing

are exhibited for a serial system in comparison to a parallel system. Such a low-pass filter capability would have been associated with non-zero values of the inductance

. This reasoning is based on the dispersion features displayed on

Figure 7 obtained for the rotation-free leaky circuit with

and

, where ever-increasing relation

is shown up to infinitely high frequencies.

The discontinuous step-up and step-down processes illustrated by the red lines on

Figure 1(d) model an idealistic situation. Instead, we suppose in practical situations that continuous ramp-up and ramp-down processes indicated by the blue dotted curves on

Figure 1(d) are more likely to take place [

33,

40,

50,

51,

62]. For that kind of temporally continuous forcing, the portion of the high-frequency response will be of less nuisance. A disadvantage is that the entire analysis would require numerical solutions for such continuous forcing functions.

It is seen from

Figure 9 that a parallel system is more efficient than a serial system in acting as a low-pass filter. In this respect, it is well-known that a central processing unit (CPU) works mostly via serial processing, while a graphical processing unit (GPU) functions via parallel processing. We are then faced with our own question as to whether a GPU serves as a generically better low-pass filter than a CPU. This question remains to be answered in our future publications.

In this respect, let us consider the serial system displayed on

Figure 8(a), where the two elements

are repeated in a serial manner as indicated by the horizontal double-headed green arrow. To find the pertinent response function, we need to modify the system given in equations (53), (54), and (55) in the following manner.

Here, the superscript ‘

’ indicates a repetition number.

We find that in equation (63) is obtainable by making substitutions and into in equation (55), thereby satisfying the usual recipe for serial extension.

Likewise, let us consider the parallel system displayed on

Figure 8(b), where the two elements

are repeated in a parallel manner as indicated by the vertical double-headed green arrow. To find the pertinent response function, we need just to modify the system given in equations (56) and (57) in the following manner.

Therefore,

in equation (64) is obtainable by making substitutions

and

into

in equation (57), thereby conforming to the usual recipe for parallel juxtaposition.

According to the ways that

and

are defined respectively in equation (11) and (32), both

and

remain unaltered even under the serial extension and the parallel juxtaposition. Consequently, the dimensionless forms in equations (63) and (64) are easily modified to the following.

Hence, we get to the following large-

limits.

Here, and are what have already been presented in equation (62), which corresponds to with a single pair of .

Notice that the response functions and have been derived by neglecting all spatial variations, while keeping only temporal variations. Notwithstanding, the error incurred by the serial extension for gets more serious due to, say, the temporal delay presented in equation (7). In comparison, the error incurred by the parallel juxtaposition for would become minimal thanks to the same longitudinal extension. Therefore, becomes less reliable as is increased, while stays relatively reliable even with creasing .

Equations (65) and (66) tell that

is uniformly decreasing with increasing

. In comparison,

appears to be rather fuzzy with varying

. Therefore,

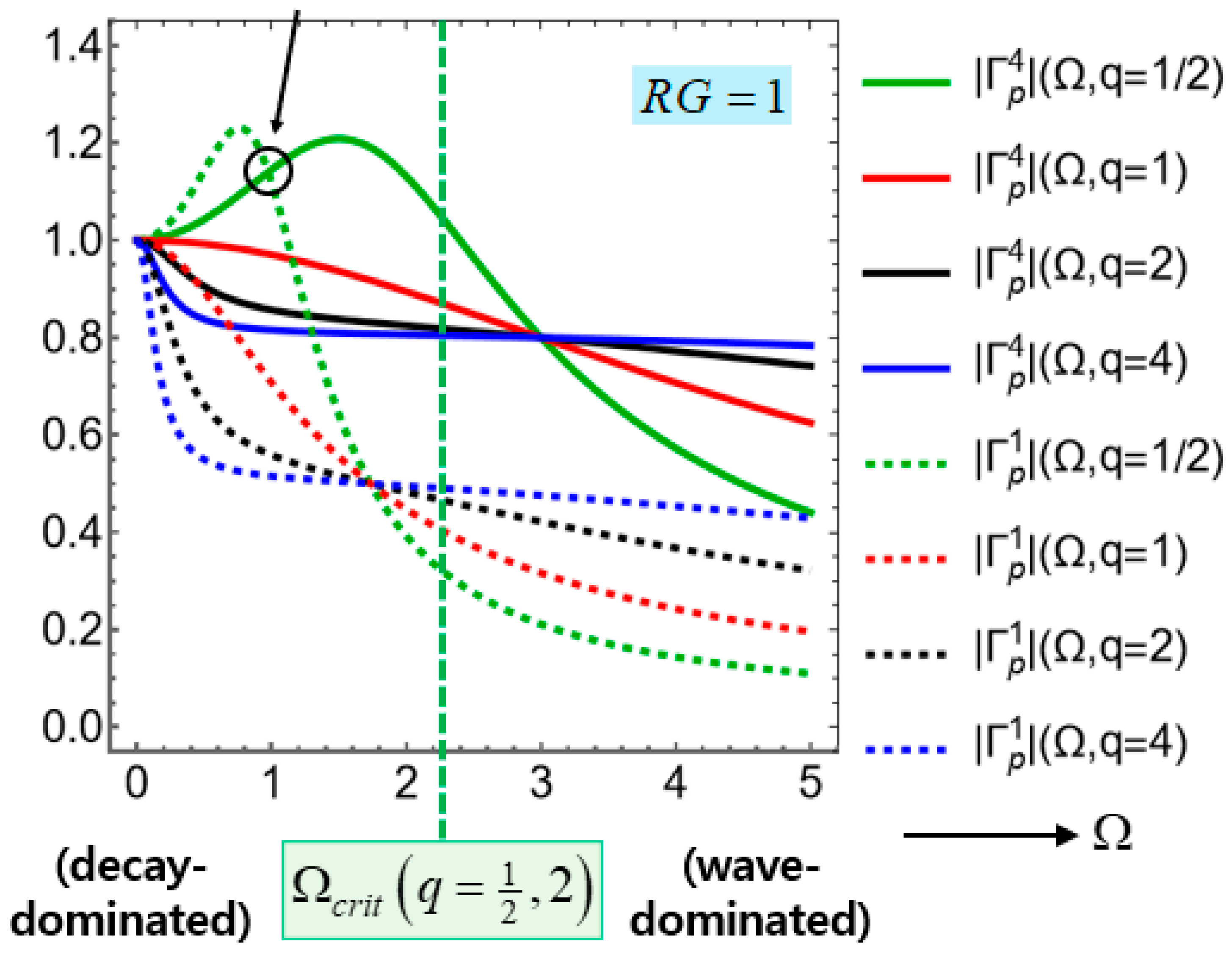

Figure 10 displays

with two values of

. We learn from

Figure 10 that

if

. In comparison,

and

undergo a crossover with varying

if

as seen by the pair of green curves, which is marked by a black blank circle and pointed to by a black solid downward arrow on

Figure 10.

We have examined the balance between

and

in equation (7) in coming up with

. Let us find below the condition that these two terms are equal in magnitudes in terms of the frequency

defined in equation (32).

Here, we have utilized

and

, which have been introduced in equation (32). Therefore,

The critical frequency is evaluated below for example.

Let us take

for both of which

. This dividing critical frequency is indicated on

Figure 10 by the green vertical dotted line.

Figure 10 marks the left region

by ‘decay-dominated’, while it marks the right region

by ‘wave-dominated’. In brief, low-pass filters favor decay-dominated temporal dynamics.