1. Introduction

Consider a continuous random variable

Y with probability density function (PDF)

. The mean of

Y is

which is the expected value under

. That is,

is the weighted average of all possible values the random variable

Y can take, where the weights are determined by the PDF

. It is often interpreted as the center of mass of the distribution.

The variance of

Y is

which quantifies the spread or dispersion of

Y about its mean.

In information theory, Shannon entropy measures the uncertainty represented by a probability distribution. The continuous (i.e., differential) entropy is defined as [

1]

Recently, Huang [

2] introduced informity theory, in which, informity measures the certainty represented by a probability distribution and acts as the complementary dual of entropy [

3]. The continuous informity is defined as [

2]

In many practical applications, a PDF describes a system comprising a signal component and a noise component. The mean naturally quantifies signal strength (or systematic effect), whereas variance , entropy , and informity each characterize different aspects of noise or uncertainty. Apparently, these measures quantifying the signal and noise separately. Although these quantities separately capture signal and noise, they do not account for their interaction, which is often critical when assessing the overall performance or informational power of a system.

This paper introduces a new measure termed inforpower that explicitly incorporates the interplay between signal and noise, thereby providing a more comprehensive quantification of a distribution’s informational power. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 formally defines inforpower;

Section 3 interprets its meaning and properties;

Section 4 presents inforpower for ten well-known continuous distributions;

Section 5 develops an inforpower-based metric and illustrates its use in practical applications;

Section 6 offers discussion and conclusions.

2. Definition and Basic Properties of Inforpower

From an information-theoretic perspective known as the information-weight interpretation of probability [

4], a realized value

y of a random variable represents information (a score or signal), while the probability

P represents the information weight or the probability density

represents the information density, attached to that value. Thus, in continuous distributions,

quantifies the certainty or noise level associated with the signal

y. The product

therefore captures the effective information: the original signal (or score) weighted (and potentially diluted) by the degree of certainty in the distribution.

Definition 1 (Effective Information)

Let

Z be the random variable representing effective information

For any realized value y, the corresponding effective information is .

Definition 2 (Inforpower)

Let

denote inforpower of a continuous probability distribution. It is defined as the expected value of the effective information

Z

Thus, inforpower is the first moment of the density-weighted signal. The following theorems reveal important structural properties of inforpower.

Theorem 1. If

is symmetric about its location parameter

a, then,

where

is the continuous informity.

Theorem 2. If is supported on [0, ∞) with no explicit location parameter (i.e., location fixed at zero) and belongs to a scale family, then is scale-invariant.

Proof of Theorems 1 and 2. Consider a generalized location-scale family of probability distributions with PDF

where

a is the location parameter,

b is the scale parameter, and

c is the shape parameter.

Make the change of variable

, then

. Substituting yields

Case 1 (Symmetric distributions, proving Theorem 1): When the distribution is symmetric about

a, the standardized density

(or simply

if no shape parameter is present) is symmetric about zero. Consequently,

is even, and

is odd, so

This establishes Theorem 1.

Case 2 (Nonnegative support, no location shift, proving Theorem 2): When the support is

and the location is fixed at

a = 0 (common for many positive distributions such as exponential, gamma, lognormal, Pareto, etc.), the term involving

a/b vanishes. Then,

which depends only on the shape parameter

c and is independent of the scale parameter

b. If the distribution has no shape parameter (e.g., standard exponential distribution),

is an absolute constant. This proves scale invariance and establishes Theorem 2. ∎

3. Interpretation of Inforpower

3.1. Inforpower as a Measure of Informational Power

Inforpower

is the expected value of the effective information

. Therefore, it quantifies the informational power (effective signal or performance) of the system described by the distribution

. To illustrate this, consider the normal distribution

. Its inforpower is

Here

represents the signal strength and

represents the noise level. Therefore,

is the classical signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), a standard performance metric in signal processing, detection theory, and measurement science. Thus, inforpower is proportional to SNR and directly measures the degree to which the original signal is preserved after being degraded by noise. In this sense,

serves as a natural and distribution-based indicator of a system’s informational power.

3.2. Inforpower as the Standardized Center of Information Energy

Inforpower admits an elegant energy-based reinterpretation. Rewrite

as

Define the normalized function

The function

is a valid probability density function, called the information-energy density function. This naming is consistent with Onicescu [

5], who named the quantity

as the information energy.

In physical analogy, on one hand,

behaves like mass density (amplitude),

is the differential mass element, and the ordinary mean

is the center of mass. On the other hand,

behaves like energy density (energy ∝ amplitude²), and

is the differential information-energy element. Thus, the expected value of

Y under

is the center of information energy

Consequently, inforpower can be expressed as the product of informity and information-energy center

Dimensional analysis confirms the following consistency:

has dimension [

y]

-1,

has dimension [

y], and their product

is dimensionless, which matches its interpretation as a pure performance index. Thus, inforpower

is the standardized center of information energy. This dual view (the SNR interpretation in

Section 3.1 and the energy-center interpretation here) reinforces

as a powerful, unified measure of informational power or performance of the system.

For symmetric distributions, (the ordinary mean). For skewed distributions, however, deviates from , typically shifting toward the higher-density regions that contribute disproportionately to the energy. Because high-density regions reflect greater certainty, can be interpreted as the effective signal strength, i.e., the location where the signal is most reliably concentrated under the energy perspective.

The concept of information-energy center extends naturally to discrete distributions; details are provided in the Appendix.

4. Inforpower for Ten Well-Known Continuous Distributions

Table 1 presents the probability density function (PDF), informity

, inforpower

, ordinary mean (center of mass)

, and center of information energy

for ten widely used continuous distributions. The first four (normal, Laplace, logistic, and Cauchy) have support on (-∞, ∞). The next five (exponential, Gamma, Rayleigh, Weibull, and lognormal) have support on [0, ∞). The Pareto distribution has support

, where

> 0 is the minimum possible value.

As

Table 1 shows, for the symmetric normal, Laplace, and logistic distributions,

. For the symmetric Cauchy distribution (location parameter

),

. These results confirm Theorem 1: when the distribution is symmetric about its location parameter

a, inforpower reduces to

.

For the remaining six distributions, which are asymmetric and supported on [0, ∞) or , the expressions for contain no scale parameter. Specifically, for the exponential and Rayleigh distributions (one-parameter families with fixed shape), is a numerical constant; for the Gamma, Weibull, lognormal, and Pareto distributions, depends solely on the shape parameter and is invariant to scale parameter. These observations fully confirm Theorem 2.

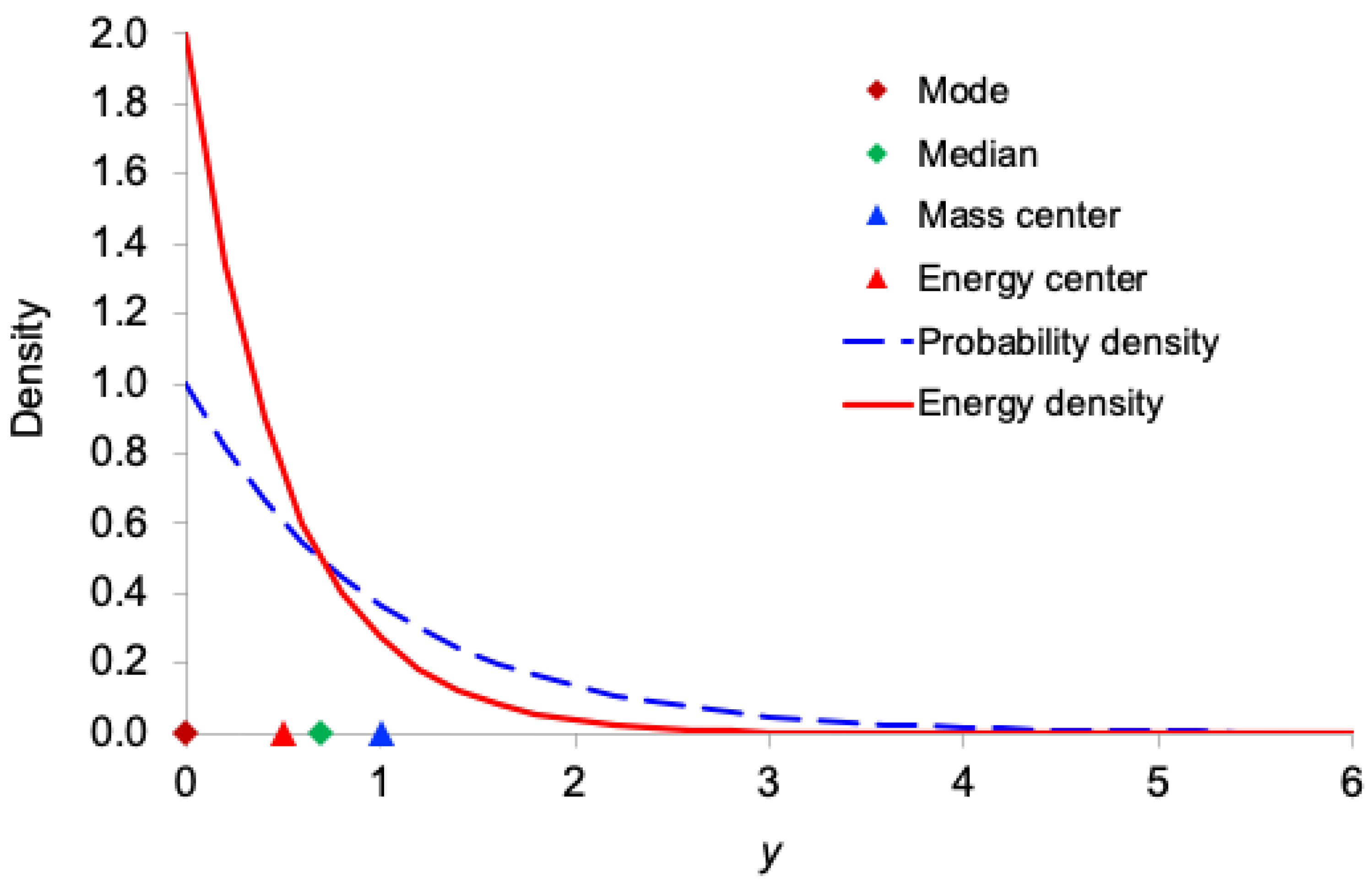

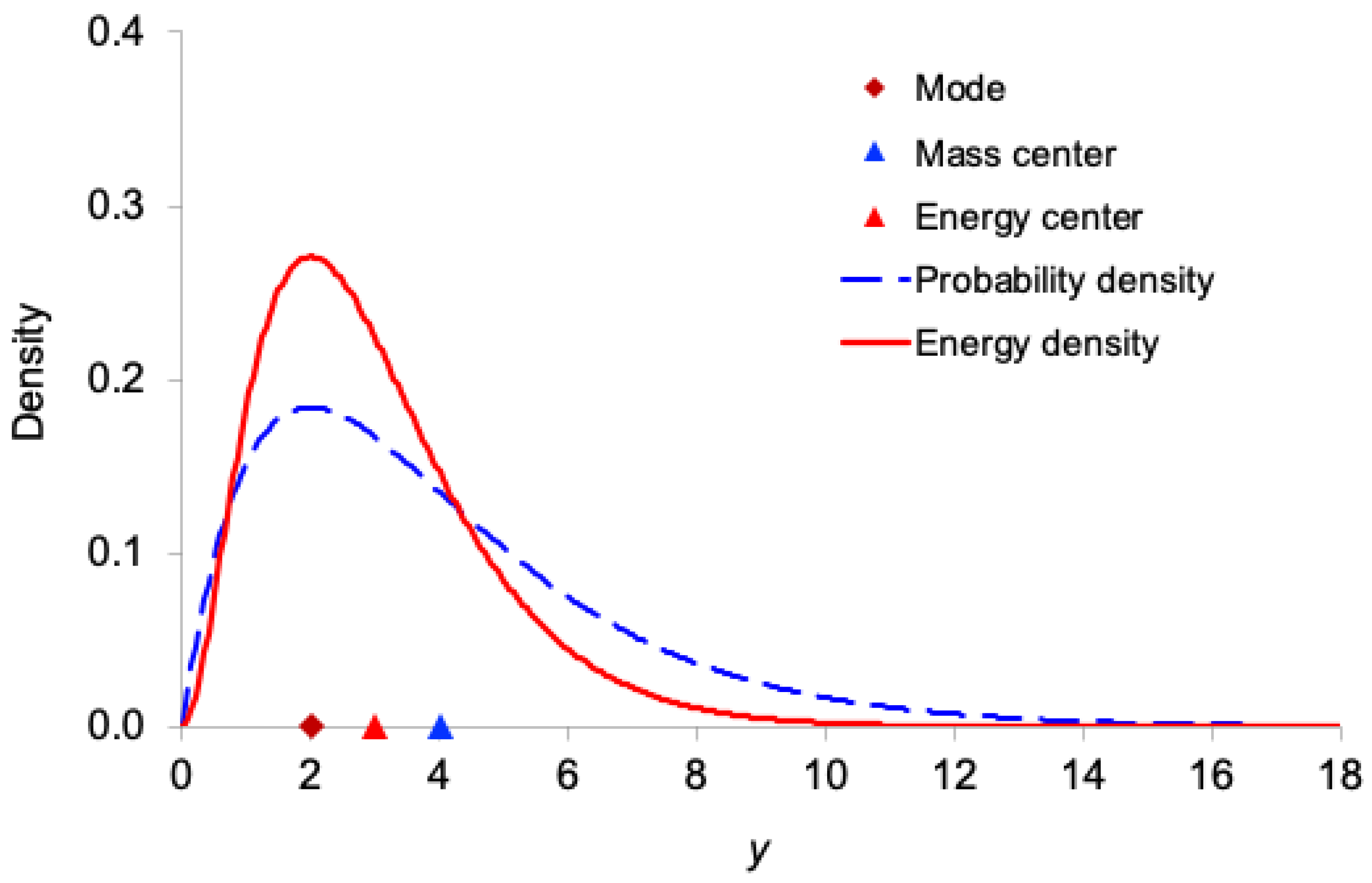

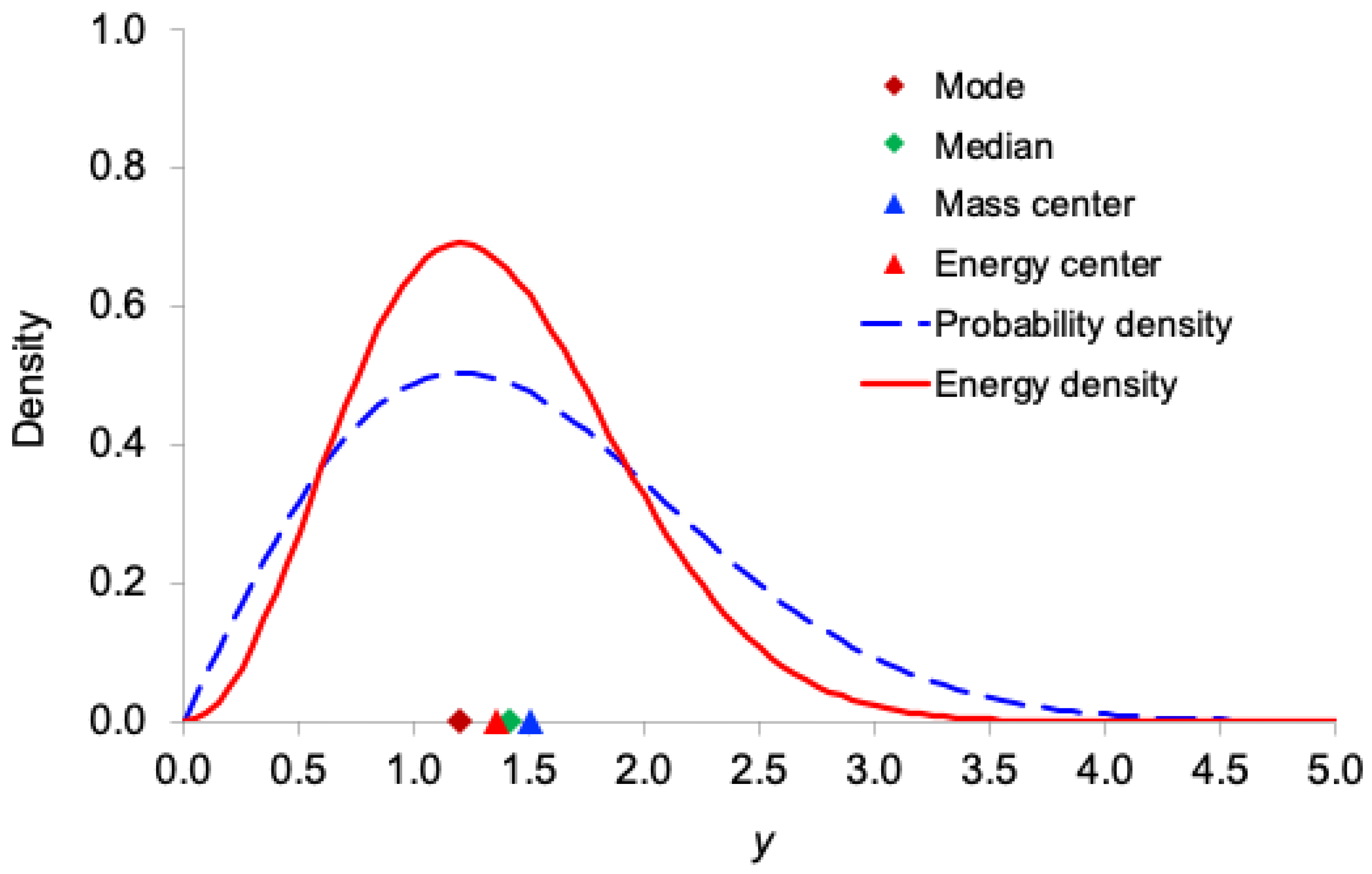

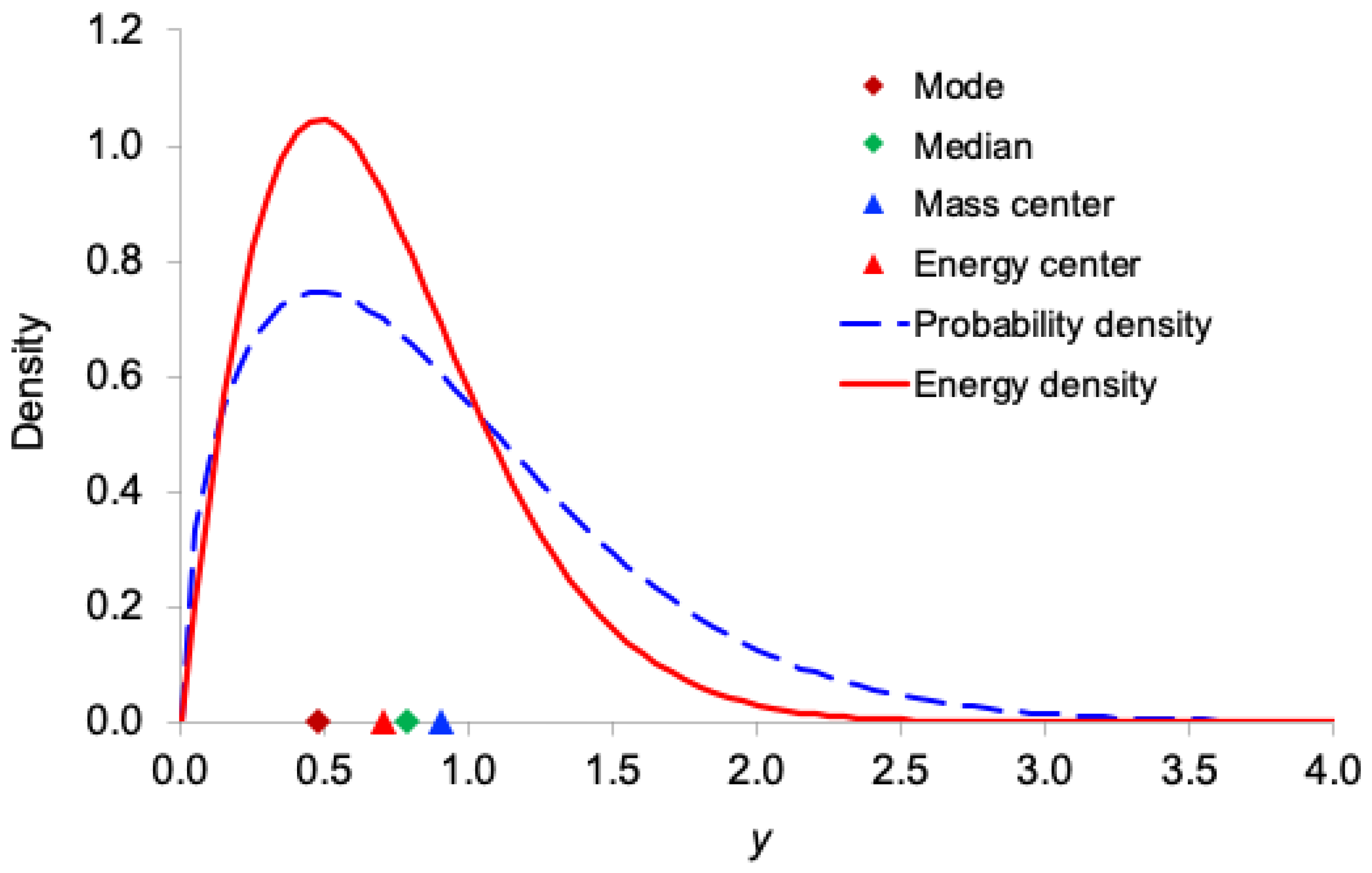

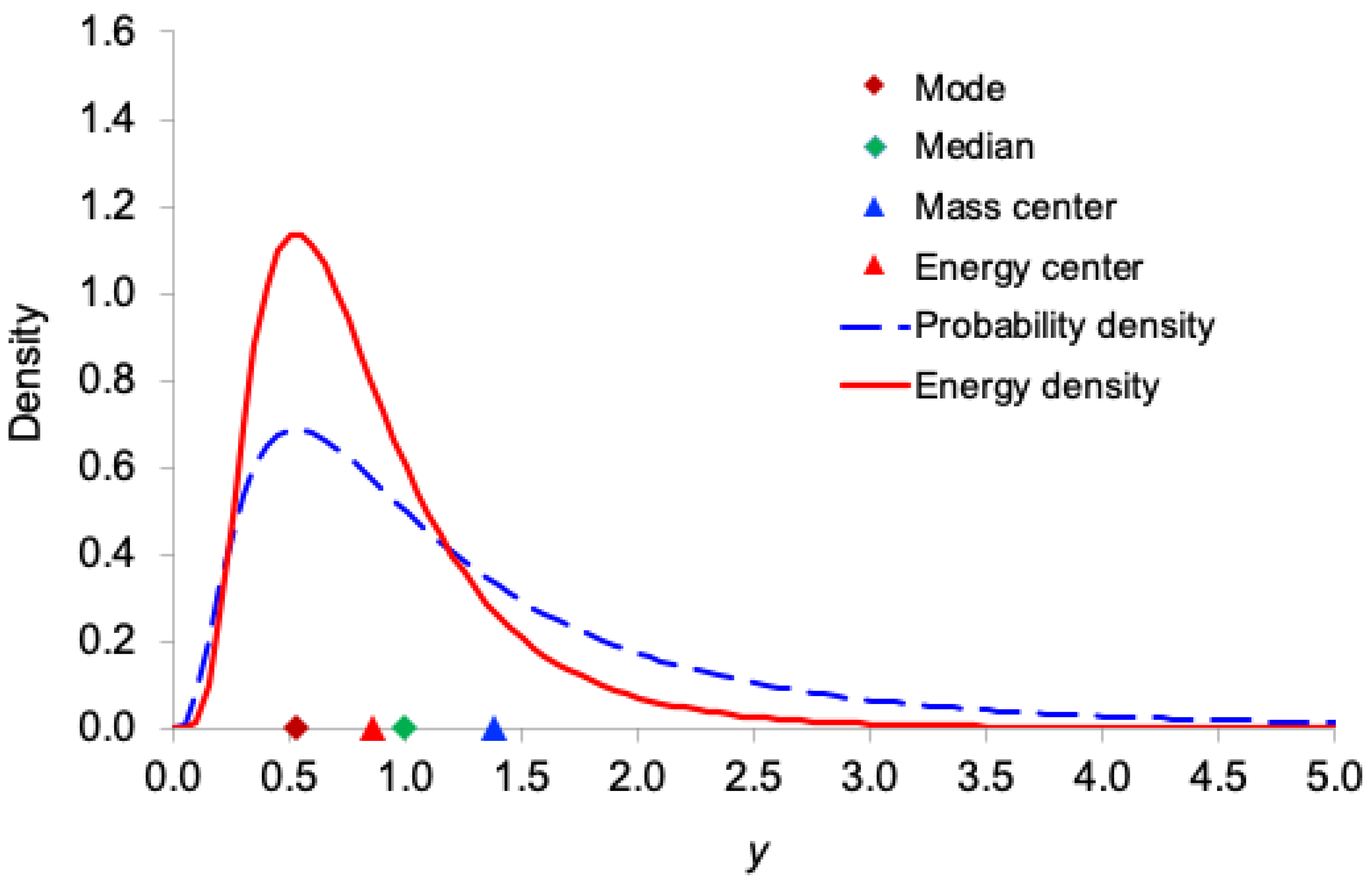

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 display, for the exponential, Gamma, Rayleigh, Weibull, and lognormal distributions respectively, both the probability density function

and the corresponding information-energy density function

. The figures also mark the mode, median, ordinary mean

(center of mass), and energy center

.

As expected, the information-energy density function is visibly sharper and more concentrated around regions of high probability density than itself, because squaring the density amplifies peaks and suppresses tails.

In all five right-skewed distributions, the locations satisfy the following consistent ordering:

mode < (energy center) < median < (mass center)

This systematic shift demonstrates that the center of information energy lies closer to the region of highest certainty (the mode) than does the ordinary mean. This provides further intuitive support for interpreting as the effective, certainty-weighted signal location and as a robust measure of the system’s informational power.

5. The Inforpower Metric and Application Examples

Inforpower provides a metric to compare and select probability distributions that model the same data.

Proposition. Given a dataset and

M candidate distributions

(

k = 1, …,

M) from the same family (i.e., sharing the same support), the preferred model is the one that maximizes inforpower

where

is the inforpower of the

k-th candidate distribution. We refer to this Proposition as the maximum inforpower criterion.

Example 1: Synthetic Weibull distribution data [

6]

A sample of

n = 200 observations was generated from a Weibull distribution with true parameters

and

. Xie [

6] fitted exponential, Weibull, Gamma, and normal distributions and compared them using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Pearson’s Q-statistic. Huang [2, 7] compared these candidate distributions using the maximum informity criterion and the minimum entropy criterion, respectively. The normal distribution was excluded from our analysis because its support differs from the other three (positive-support) candidates. The estimated parameters are as follows [

6]: exponential distribution:

, Weibull distribution:

and

, Gamma distribution:

and

.

Table 2 reports the performance of each distribution under five criteria.

As shown in

Table 2, the Weibull distribution ranks first under the AIC, minimum entropy, and maximum inforpower criteria, confirming that the true generating distribution is correctly identified by the inforpower metric. Although the Q-statistic and maximum informity criteria favor the Gamma distribution, Xie [

6] noted that ΔAIC = 4.7 between the Weibull and Gamma distributions is small and that the AIC “selects a good model which is not necessarily the true model.” Overall, the five criteria yield highly consistent conclusions.

Example 2: Annual maximum streamflow of the Tana River, Kenya (1941–2016)

Langat et al. [

8] analyzed the historical flow data collected from the Tana River (one of the longest rivers in Kenya) between 1941 and 2016. One of their goals was to find the best statistical distribution to model annual maximum streamflow. They considered six candidate distributions and used the Akaike information criterion (AIC) for selection. We focused on the following three best-performing candidates they identified: the Gamma (Pearson Type III), lognormal, and Weibull distributions.

Table 3 shows the estimated parameters and AIC values, and our analysis results for the entropy, informity, and inforpower metrics.

As shown in

Table 3, among these three distributions, the lognormal distribution is the best according to the all four goodness-of-fit metrics (minimum AIC, minimum entropy, maximum informity, and maximum inforpower). The Gamma distribution is the second best, while the Weibull is the worst.

Table 4 shows the percentage differences in metrics between the Weibull and lognormal distributions, computed as (Weibull – Lognormal)/Lognormal × 100%.

Although the AIC and entropy metric detect only tiny differences (0.157% and 0.369%), the informity and inforpower metrics reveal substantially larger separations (–6.730% and –1.968%, respectively). This demonstrates that inforpower (and informity) can be considerably more sensitive than the traditional information criteria when distinguishing competing heavy-tailed distributions in hydrological and other positive-skewed applications.

These examples illustrate that the maximum inforpower criterion is intuitive, easy to compute, and either agrees with or usefully complements established model-selection tools such as the AIC, minimum entropy criterion, and maximum informity criterion.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

A distinctive and desirable feature of inforpower

is its sensitivity to location shifts. Adding a constant

a to the random variable

changes

, reflecting an actual change in signal strength or systematic effect. In contrast, variance, differential entropy

, and informity

are all translation-invariant. For example, in the normal distribution

, the entropy

and informity

depend only on

σ, not on the location

μ. While translation invariance is useful when one wishes to measure pure spread or uncertainty, it is considered as a drawback in applications where it is necessary to take into account the values of the random variable along with their probabilities (or densities) [

9].

Attempts to remedy the translation-invariance problem in related quantities have appeared in the literature. Belis and Guiasu [

10] introduced weighted entropy:

More recently, several authors [9, 11, 12] defined extropy for continuous distributions as

and proposed a weighted extropy (restricted to nonnegative random variables)

Although weighted extropy is formally −½ times informity, the two measures arise from fundamentally different conceptual foundations. Extropy was originally motivated as a “complementary dual” of entropy, a claim that has been critiqued on both theoretical and interpretative grounds [

4]. Consequently, weighted extropy inherits these conceptual difficulties, whereas inforpower—defined directly as the expected effective information

—possesses clear probabilistic, informational, and physical interpretations (

Section 3 and

Section 4) without requiring an intermediate appeal to extropy.

Inforpower

and the information-energy center

are both robust statistics. They exist even when ordinary moments fail: for the Cauchy distribution, the mean and variance are undefined, but

and

remain well-defined, and

equals the location parameter times

. For right-skewed distributions on [0, ∞), empirical evidence (

Section 4) consistently places the energy center in the order: mode <

< median < mean, highlighting

as an effective signal strength that lies closer to the region of highest probability density.

Computation of

and

requires an explicit PDF. In empirical studies, this is not a significant limitation: simply fit candidate distributions to the observed data (using maximum likelihood estimation or other estimation methods), and then evaluate

on the fitted models. The maximum inforpower criterion (

Section 5) thereby provides a simple model-selection rule that complements or even outperforms traditional tools (such as AIC) in applications where signal magnitude, peak sharpness, and tail behavior matter (e.g., hydrology, finance, reliability engineering, and extreme-value analysis).

For symmetric location-scale families (normal, Laplace, logistic, Student’s t, etc.), . When comparing distributions with the same estimated location , the maximum inforpower criterion collapses to the maximum informity criterion. In all other cases, especially positive-support and skewed data, it offers additional discrimination power, as demonstrated by the Tana River streamflow example.

In summary, inforpower constitutes a principled, robust, and effective measure of informational power that naturally integrates signal strength and noise level. The maximum inforpower criterion is easy to implement and provides a valuable new tool for distribution selection and performance assessment. Future research should explore its behavior in multivariate settings, its sampling properties, and its applications to machine learning, finance, and information fusion.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest and that no funding was received for conducting this study.

Appendix. Information-Energy Center for Discrete Distributions

Definition 3. For a discrete random variable

X with probability mass function (PMF)

, the center of information energy is defined as

where

is the discrete informity [

2], and

is called the information energy function given by

Therefore, the center of information energy for a discrete distribution is the expected value of X under .

Example 3: Binomial distribution

Consider the binomial distribution

. Its probability mass function (PMF) is given by

where

p is the success probability,

n is the number of trials,

, and

The discrete informity of the binomial distribution is given by

The information energy function is given by

Then, the center of information energy is given by

When , the distribution is symmetric, . When , the distribution is slightly right-skewed, is slightly greater than . When , the distribution is slightly left-skewed, is slightly smaller than .

References

- Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communications. The Bell System Technical Journal, 1948, 27, 379-423, 623-656.

- Huang, H. The theory of informity: a novel probability framework. Bulletin of Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Physics and Mathematics, 2015, 80(1), 53-59. [CrossRef]

- Hening Huang. Extropy’s Limitations as a Complementary Dual of Entropy and the Role of Informity. Qeios. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H. Information-Weight Interpretation of Probability: A Novel Information-Theoretic Perspective. Preprints. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Onicescu, O. Théorie de l’information énergie informationelle. Comptes Rendus De L’Academie Des Sci. Ser. AB 1966, 263, 841–842.

- Xie, G. Further developments of two point process models for fine-scale time series. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, 2011, Massey University, Wellington.

- Huang, H. A minimum entropy criterion for distribution selection for measurement uncertainty analysis. Measurement Science and Technology, 2024, 35, 035014. DOI: 10.1088/1361-6501/ad1476.

- Langat, P. K., Kumar, L., & Koech, R. Identification of the Most Suitable Probability Distribution Models for Maximum, Minimum, and Mean Streamflow. Water, 2019, 11(4), 734. [CrossRef]

- Sathar, E.I.A., & Nair, R.D. On dynamic weighted extropy. J. Comput. Appl. Math., 2021, 393, 113507.

- Belis, M. and 12. su, S. A quantitative-qualitative measure of information in cybernetic systems (Corresp.). IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 1968, 14(4), 593-594. [CrossRef]

- Lad, F., Sanfilippo, G., & Agrò, G. Extropy: Complementary Dual of Entropy. Statistical Science, 30(1), 2015, 40–58. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, N., Buono, F., & Longobardi, M. On weighted extropies. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods, 2020, 51(18), 6250–6267. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).