Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

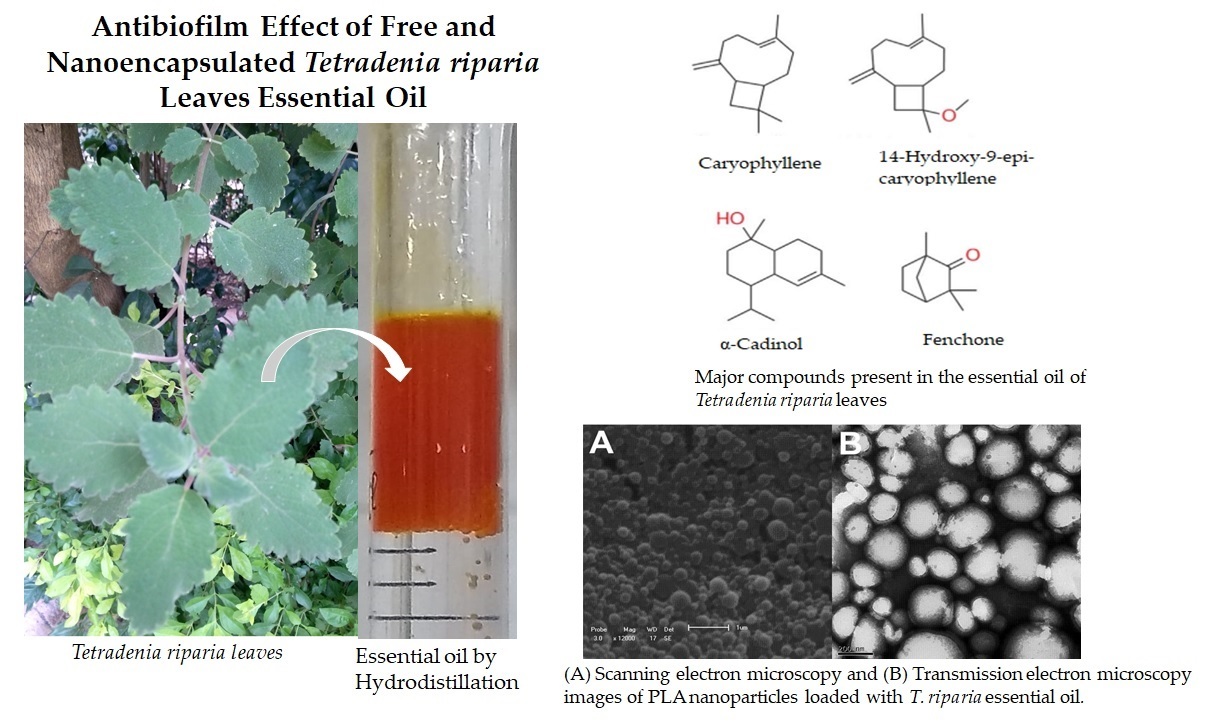

2.1. Plant Material, Botanical Identification, and Extraction of Essential Oils

2.2. Chemical Identification of Essential Oils

2.3. Nanoparticle Preparation

2.4. Nanoparticle Characterization

2.5. Thermal Analysis

2.6. Encapsulation Efficiency

2.7. In Vitro Release Profile

2.8. Stability Assays

2.9. Strains and Growth Conditions

2.10. Microdilution Assay

2.11. Antibiofilm Activity

2.12. Cytotoxicity Assay

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Composition of Tetradenia riparia Leaf Essential Oil

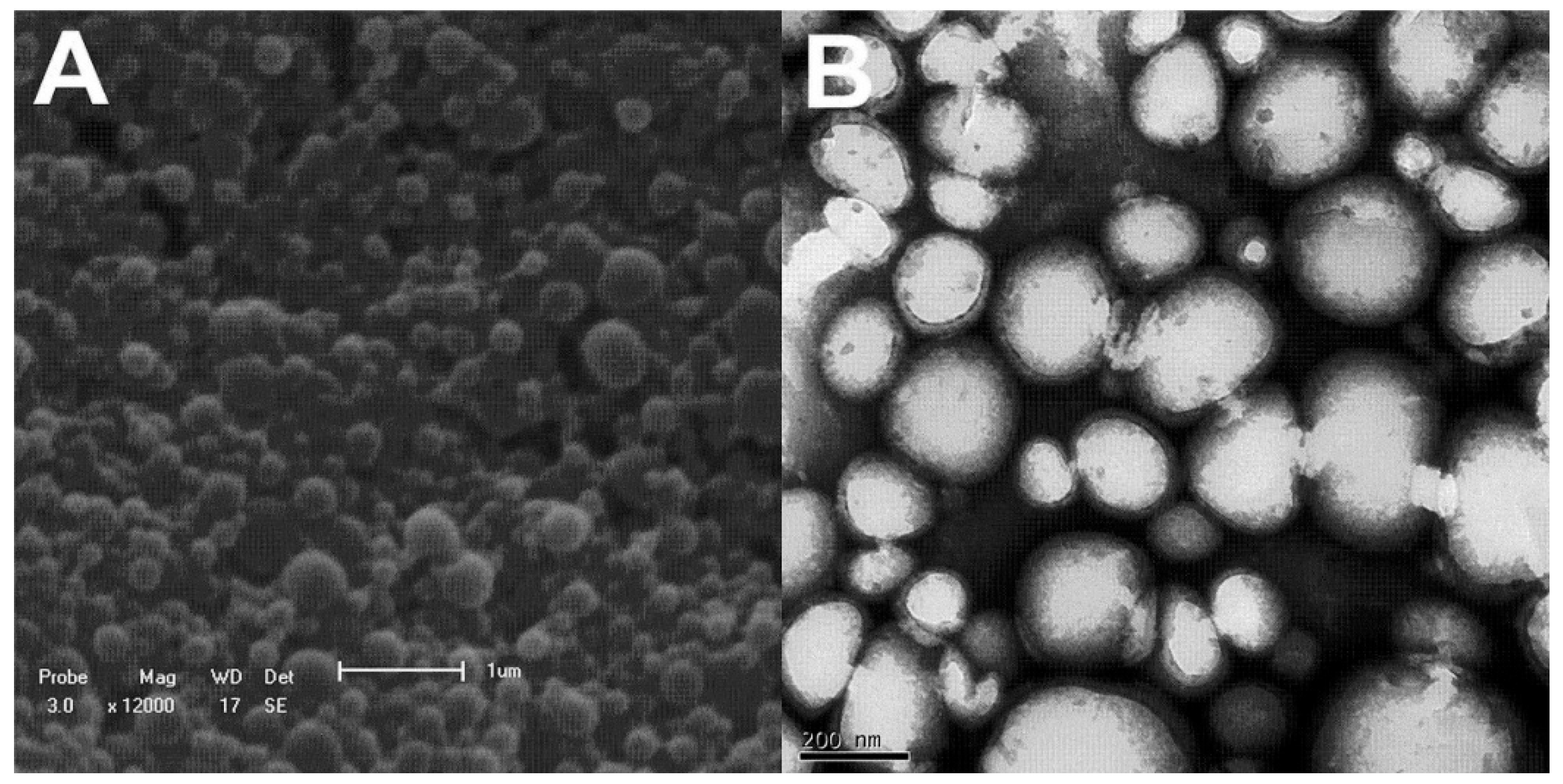

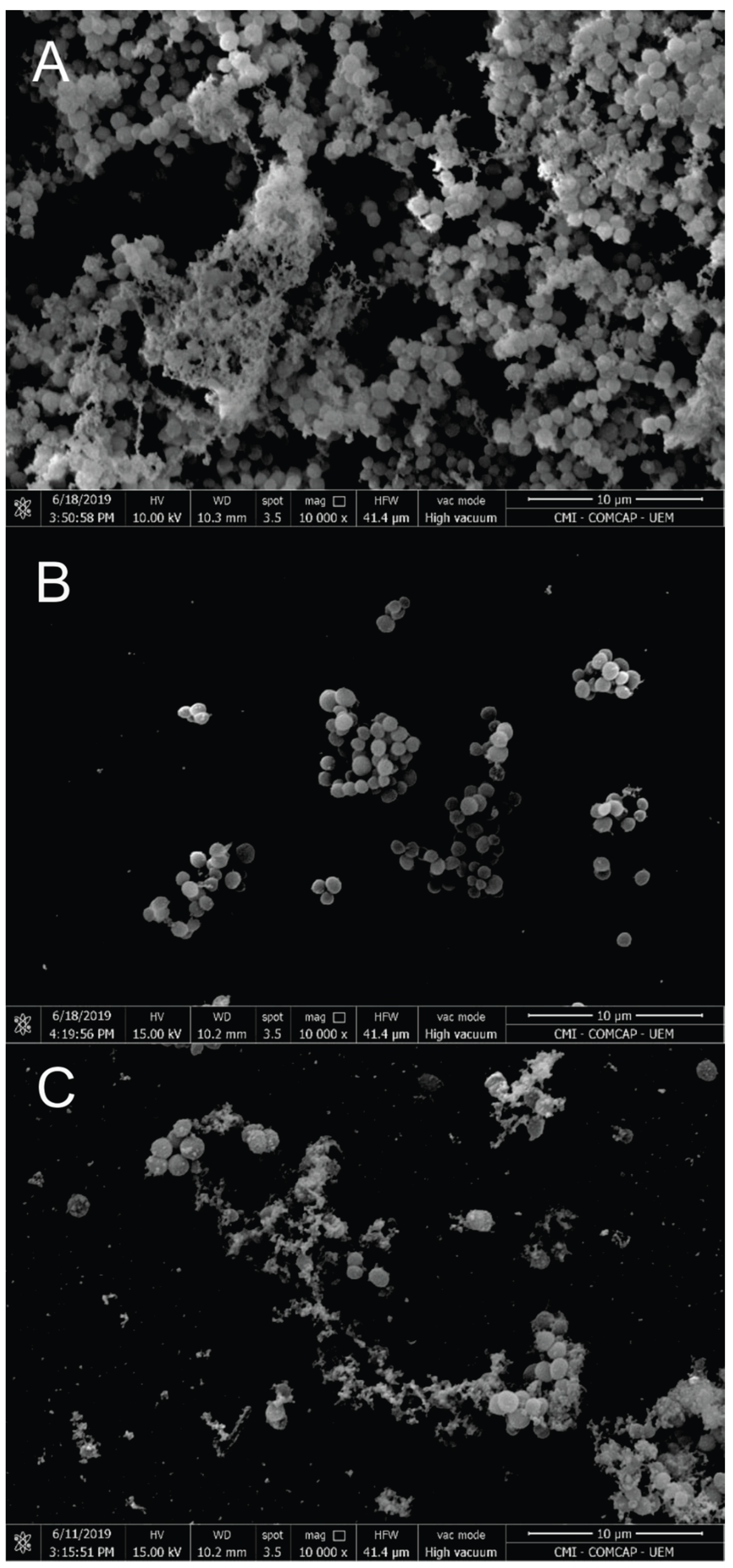

3.2. Nanoparticle Characterization

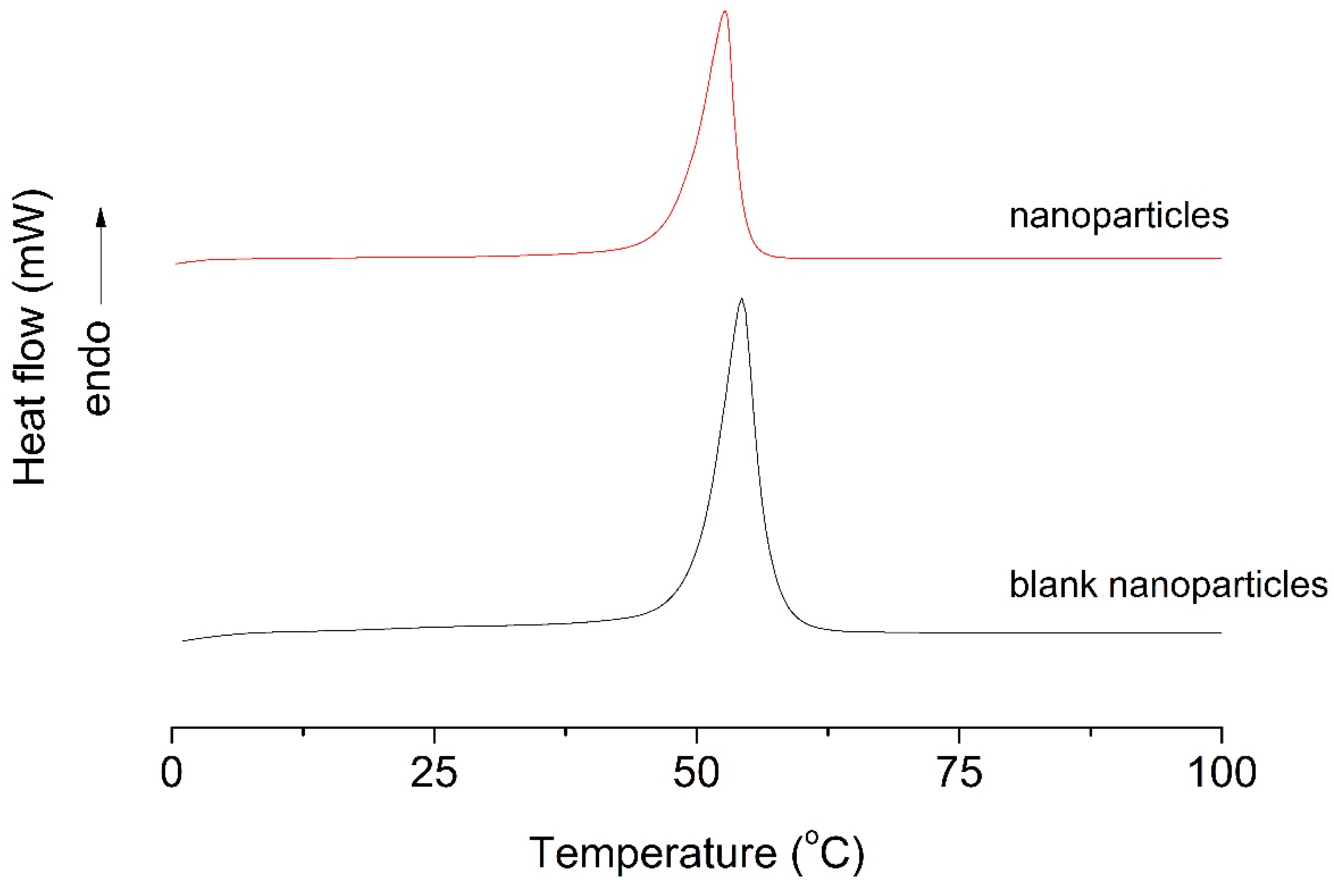

3.3. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

3.4. Encapsulation Efficiency

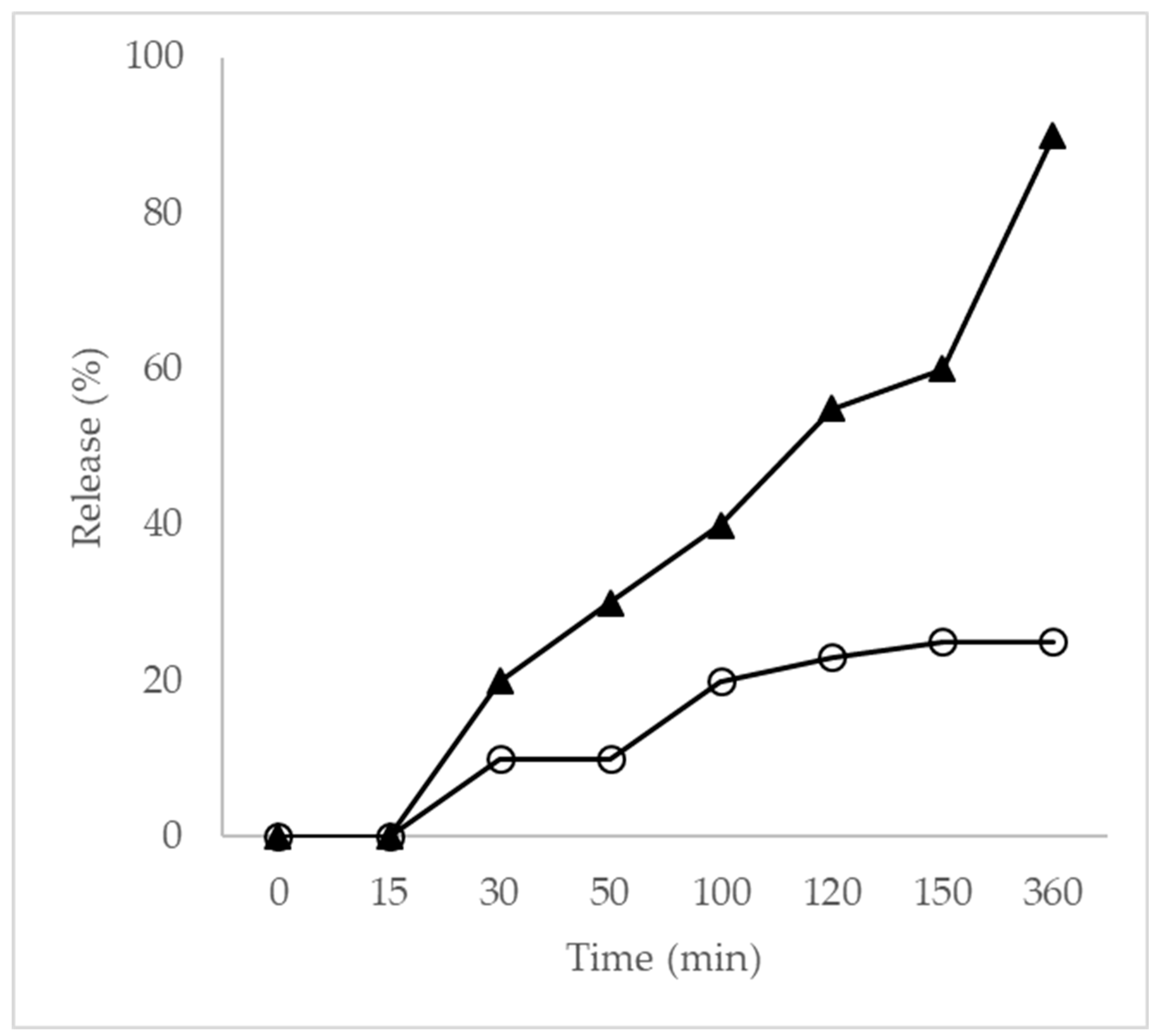

3.5. In Vitro Release

3.6. Antibacterial Activity

3.7. Cytotoxicity Assay

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EO | Essential oils |

| NP | Nanoparticles |

| PLA | Poly (L-lactide) |

| DLS | Dynamic light scattering |

| SEM | Scanning electron microscopy. |

| TEM | Transmission electron microscopy |

| DSC | Differential scanning calorimetry |

| MHA | Mueller Hinton Agar |

| MHB | Mueller Hinton Broth |

| CFU | Colony forming unit |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| MBC | Minimum bactericidal concentration |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| TSB | Tryptic soy broth |

| MTT | Dimethylthiazol-2-yl-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide |

| DMSO | Dimethyl sulfoxide |

| BIC50 | 50% biofilm inhibitory concentration |

| OD | Optical density |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| IC50 | 50% inhibitory concentrations |

References

- Goldmann, O.; Medina, E. Staphylococcus aureus strategies to evade the host acquired immune responde. Int. J. Med. Microb. 2018, 308, 625–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, M.; Crulhas, B.P.; Alves, F.C.B.; Pereira, A.F.M.; Andrade, B.F.M.T.; Barbosa, LN.; Furlanetto, A.; Lyra, L.P.S.; Rall, V.L.M.; Fernandes Júnior, A. Antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities of cinnamaldehyde against S. epidermidis. Microb. Pathog. 2019, 126, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forier, K.; Raemdonck, K.; De Smedt, S.C.; Demeester, J.; Coenye, T.; Braeckmans, K. Lipid and polymer nanoparticles for drug delivery to bacterial biofilms. J. Control. Release 2014, 190, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, V.B.; Morais, S.M.; Fontenelle, R.O.S.; Queiroz, V.A.; Vila-Nova, N.S.; Pereira, C.M.C.; Brito, E.S.; Neto, M.A.; Brito, E.H.S.; Cavalcante, C.S.P.; Castelo-Branco, D.S.C.M.; Rocha, M.F.G. 2012. Antifungal activity, toxicity and chemical composition of the essential oil of Coriandrum sativum L. fruits. Molecules 2012, 17, 8439–8448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raut, J.S.; Karuppayil, S.M. A status review on the medicinal properties of essential oil. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 250–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalian, A.; Shams-Ghahfarokhi, M.; Jaimand, K.; Pashootan, N.; Amani, A.; Razzaghi-Abyyaneh, M. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of Matricaria recutita flower essential oil against medically important dermatophytes and soil-borne pathogens. J. Mycol. Med. 2012, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- São-Pedro, A.; Espirito-Santo, I.; Silva, V.C. Albuquereque, E. The use of nanotechnology as an approach for essential oil-based formulations with antimicrobial activity. Microbial Pathogens (A. Mendez-Vilas. Ed.). 2013 1, 1364-1374. [CrossRef]

- Gairola, S.; Yougasphree Naidoo, Y.; Bhatt, A.; Nicholas, A. An investigation of the foliar trichomes of Tetradenia riparia (Hochst.) Codd [Lamiaceae]: An important medicinal plant of Southern Africa. Flora 2009, 204, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazim, Z.C.; Rodrigues, F.; Amorim, A.C.L.; Rezende, C.M.; Sokovic, C.M.; Tesevic, V.; Vuchovic, I. , Krstic, G., Cortez, L.E.R.; Colauto, N.B.; Linde, G.A.; Cortez, D.A.G. New natural diterpene-type abietane from Tetradenia riparia essential oil with cytotoxic and antioxidant activities. Molecules 2014, 19, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazim, Z.C.; Amorim, A.C.; Hovell, A.M.; Rezende, C.M.; Nascimento, A.; Ferreira, G.A.; Cortez, D.A.G. Seasonal variation, chemical composition, analgesic and antimicrobial activities of the essential oil from leaves of Tetradenia riparia (Hochst.) Codd in Southern Brazil. Molecules 2010, 15, 5509–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, P.F.; Alves, J.M.; Damasceno, J.L.; Oliveira, R.A.M.; Dias, H.J.; Crotti, A.E.M.; Tavares, D.C. Cytotoxicity screening of essential oils in cancer cell lines. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 2015, 25, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njau, E.A.; Alcorn, J.; Buza, J.; Chirino-Trejo, M.; Ndakidemi, P. Antimicrobial activity of Tetradenia riparia (Hochst.) Lamiaceae, a medicinal plant from Tanzania. Eur. J. Med. Plants 2014, 4, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, E.F.; Paula, H.C.B.; Paula, R.C.M. Alginate/cashew gum nanoparticles for essential oil encapsulation. Coll Surf B 2014, 113, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazim, Z.C.; Demarchi, I.G.; Lonardoni, M.V.C.; Amorim, A.C.L.; Hovell, A.M.C.; Rezende, C.M.; Ferreira, C.M.; Lima, E.L.; Cosmo, F.A.; Cortez, D.A.G. Acaricidal activity of the essential oil from Tetradenia riparia (Lamiaceae) on the cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) mocroplus (Acari: Ixodidae). Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 29, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barwall, I.; Sood, A.; Sharma, M.; Singh, B.; Yadav, S.C. 2013. Development of stevioside Pluronic F-68 copolymer based PLA-nanoparticles as an antidiabetic nanomedicine. Coll Surf B 2013, 101, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, G. P. Estabilidade de Medicamentos Sintéticos: Visão Geral da nova Diretriz da Anvisa. 2020.

- Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility test for bacteria that grow aerobically. Approved standard, 9th ed. M07-A9, CLSI, 2012, Wayne, PA.

- Schillaci, D.; Arizza, V.; Dayton, T.; Camarda, L.; Stefano, V.D. In vitro anti-biofilm activity of Boswellia spp. oleogum resin essential oils. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 47, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tangarife-Castaño, V.; Roa-Linares, V.; Betancur-Galvis, L.A.; Garcia, D.C. , Stashenko, E.; Mesa-Arango, A.C. Antifungal activity of Verbenaceae and Labitae families essential oils. Pharmacologyonline 2011, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smadja, J.; Rondeau, P.; Sing, A.S.C. Volatile constituents of five Citrus petitgrain essential oils from Reunion. Flavour Fragr. J. 2005, 20, 399–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlovic, M.; Kovacevic, N.; Tzakou, O.; Couladis, M. Essential oil composition of Anthemis triumfetti (L.) DC. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R.A.; Navarro, T.; de Lorenzo, C. HS-SPME analysis of the volatile compounds from spices as a source of flavour in 'Campo Real' table olive preparations. Flavour Fragr. J. 2007, 22, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrakis, P.V.; Roussis, V.; Papadimitriou, D.; Vagias, C.; Tsitsimpikou, C. The effect of terpenoid extracts from 15 pine species on the feeding behavioural sequence of the late instars of the pine processionary caterpillar Thaumetopoea pityocampa. Behav. Processes. 2005, 69, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.X.; Liang, Y.Z.; Fang, H.Z.; Li, X.-N. Temperature-programmed retention indices for gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy analysis of plant essential oils. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005, 1096, 76-85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranauskiene, R.; Venskutonis, P.R.; Viskelis, P.; Dambrauskiene, E. Influence of nitrogen fertilizers on the yield and composition of thyme (Thymus vulgaris). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 7751–7758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.X.; Li, X.N.; Liang, Y.Z.; Fang, H.Z.; Huang, L.F.; Guo, F.Q. Comparative analysis of chemical components of essential oils from different samples of Rhododendron with the help of chemometrics methods. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2006, 82, 218-228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazzit, M.; Baaliouamer, A.; Faleiro, M.L.; Miguel, M.G. Composition of the Essential Oils of Thymus and Origanum Species from Algeria and Their Antioxidant and Antimicrobial Activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 6314–6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukic, J.; Petrovic, S.; Pavlovic, M.; Couladis, M.; Tzakou, O.; Niketic, M. Composition of essential oil of Stachys alpina L. ssp dinarica Murb. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siani, A.C.; Garrido, I.S.; Monteiro, S.S.; Carvalho, E.S.; Ramos, M.F.S. Protium icicariba as a source of volatile essences. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2004, 32, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siani, A.C.; Ramos, M.F.S.; Menezes-de-Lima, O., Jr.; Ribeiro-dos Santos, R.; Fernandez-Ferreira, E.; Soares, R.O.A.; Rosas, E.C.; Susunaga, G.S.; Guimarães, A.C.; Zoghbi, M.G.B.; Henriques, M.G.M.O. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory-related activity of essential oils from the leaves and resin of species of Protium. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1999, 66, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chorianopoulos, N.; Evergets, E.; Mallouchos, A.; Kalpoutzakis, E.; Nychas, G.J.; Haroutounian, S.A. Characterization of the essential oil volatiles of Satureja thymbra and Satureja parnassica: Influence of harvesting time and antimicrobial activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 3139–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyerstahl, P.; Marschall, H.; Splittgerber, U.; Wolf, D.; Surburg, H. Constituents of Haitian vetiver oil. Flavour Fragr. J. 2000, 15, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonzo, G.; Bosco, S.F.D.; Palazzolo, E.; Saiano, F.; Tusa, N. Citrus somatic hybrid leaf essential oil. Flavour Fragr. J. 2000, 15, 258–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussis, V.; Tsoukatou, M.; Petrakis, P.V.; Chinou, I.B.; Skoula, M.; Harborne, J.B. Volatile Constituents of Four Helichrysum Species Growing in Greece. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2000, 28, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monsef-Esfahani, H.R.; Miri, A.; Amini, M.; Amanzadeh, Y.; Hadjiakhoondi, A.; Hajiaghaee, R.; Ajani, Y. Seasonal variations in the chemical composition, antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of Teucrium persicum Boiss. essential oils. Res. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 5, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujisic, L.; Vuckovic, I.; Tesevic, V.; Dokovic, D.; Ristic, M.S.; Janackovic, P.; Milosavljevic, S. Comparative examination of the essential oils of Anthemis ruthenica and A. arvensis wild-growing in Serbia. Flavour Fragr. J. 2006, 21, 458–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini, G.; Tebano, M.; Cioni, P.L.; Bagci, Y.; Dural, H.; Ertugrul, K.; Uysal, T.; Savran, A. A multivariate statistical approach to Centaurea classification using essential oil composition data of some species from Turkey. Pl. Syst. Evol. 2006, 261, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, J.D.S.; Rodrigues, S.A.; Sakumoto, K.; Inumaro, R.S.; González-Maldonado, P.; Mendez-Scolari, E.; Gazim, Z.C. Antioxidant activity, antiproliferative activity, antiviral activity, NO production inhibition, and chemical composition of essential oils and crude extracts of leaves, flower buds, and stems of Tetradenia riparia. Pharmaceuticals. 2024, 17, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Al-Khalifa, A. R.; Aouf, A.; Boukhebti, H.; Farouk, A. Effect of nanoencapsulation on volatile constituents, and antioxidant and anticancer activities of Algerian Origanum glandulosum Desf. essential oil. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10(1), 2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng-Lian Y, Zue-Gang L, Zhu F. Structural characterization of nanoparticles loaded with garlic essential oil and their insecticidal activity against Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Agric. Food Chem 2009, 10156, 10162-57. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Shi, Z.; Neoh, K.G.; Kang, E.T. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Eugenol and Carvacrol-grafted chitosan nanoparticles. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2009, 104, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffazick, S. R. , Guterres, S. S., Freitas, L. L., Pohlmann, A. R., 2003. Caracterização e estabilidade físico-química de sistemas poliméricos nanoparticulados para administração de fármacos. Quím. Nova, 2003, 26, 726–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, A.; Deepagan, V.G.; Divya Rani, V.V.; Deepthy Menon, S.V.N.; Jayakumar, R. Preparation, characterization, in vitro drug release and biological studies of curcumin loaded dextran sulphate-chitosan nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 1158–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, M.C.T.; Figueira, G.M.; Sartoratto, A.; Rehder, V.L.G.; Delamarmelina, C. . Anti-Candida activity of Brazilian medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2005, 97, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, J.; Jin, W.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, X.; Liu, L. Antibacterial and anti-biofilm activities of peppermint essential oil against S. aureus. LWT – Food Science and Technology, 2019, 101, 639-645.

- Kwiecinski, J.; Eick, S.; Wojcik, K. Effects of tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) oil on in biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents, 2009, 33, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reichiling, J.; Schnitzler, P.; Sushke, U.; Saller, R. Essential oils of aromatic plants with antibacterial, antifungal, antiviral and cytotoxic properties – an overview. Forsch. Komplementmed. 2009, 16, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifi, I.; Dzoyem, J.P.; Quinten, M.; Yousfi, M.; Mcgaw, L.J.; Eloff, J.N. Antimycobacterial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities of essential oil of gall of Pistacia atlantica desf. from Algeria. Afr. J. Tradit. Complement Altern. Med. 2015, 12, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayarathna, S.; Sasudharan, S. Cytotoxicity of methanol extracts of Elaeis guineensis on MCF-7 and VERO cell lines. Asian Pac. J. of Trop. Biomed. 2012, 2, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilia, A.R.; Guccione, C.; Isacchi, B.; Righeschi, C.; Firenzuolo, F.; Bergonzi, C. Essential oils loaded in nanosystem: A developing strategy for a successful therapeutic approach. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2014, 6, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Peak | R.T. (min) | Compounds | Relative area % | RI Calc. | RI Lit. | Literature |

| 1 | 3.6 | α-pinene | 1.25 | 906 | 910 | 20 |

| 2 | 4.4 | Camphene | 0.97 | 951 | 952 | 21 |

| 3 | 5.5 | Fenchone | 27.19 | 1091 | 1092 | 22 |

| 4 | 6 | Fenchol | 0.41 | 1116 | 1117 | 23 |

| 5 | 6.7 | Camphor | 1.02 | 1148 | 1149 | 24 |

| 6 | 7.2 | endo-Borneol | 0.19 | 1168 | 1168 | 25 |

| 7 | 7.8 | Terpinen-4-ol | 0.13 | 1180 | 1181 | 26 |

| 8 | 11.7 | alfa-copaene | 0.18 | 1375 | 1376 | 27 |

| 9 | 12.8 | β-elemene | 0.18 | 1390 | 1390 | 28 |

| 10 | 13.3 | α-gurjunene | 0.18 | 1408 | 1408 | 27 |

| 11 | 14.2 | Caryophyllene | 8.4 | 1418 | 1418 | 29 |

| 12 | 14.6 | γ-Elemene | 1.88 | 1427 | 1425 | 30 |

| 13 | 15.3 | γ-muurolene | 0.88 | 1475 | 1475 | 31 |

| 14 | 16.4 | 6-epi-shyobunol | 1.08 | 1522 | 1522 | 32 |

| 15 | 17.1 | Germacrene D-4-ol | 1.06 | 1574 | 1574 | 28 |

| 16 | 17.8 | (-)-Spathulenol | 0.12 | 1576 | 1576 | 33 |

| 17 | 18.6 | Caryophyllene oxide | 1.02 | 1581 | 1581 | 34 |

| 18 | 19.4 | Ledol | 0.18 | 1605 | 1607 | 35 |

| 19 | 20.7 | δ-cadinol | 1.63 | 1649 | 1649 | 36 |

| 20 | 21.2 | α-cadinol | 16.12 | 1668 | 1674 | 37 |

| 21 | 21.9 | 14-hydroxy-9-epi-caryophyllene | 13.09 | 1690 | 1674 | 34 |

| 22 | 29.2 | 9β,13β-Epoxi-7-abietene | 11.5 | 1883 | 1888 | 38 |

| 23 | 31.1 | Abietadiene | 0.98 | 2081 | 2085 | 38 |

| 24 | 33.6 | 6,7-dehydroroyleanone | 8.73 | 2094 | 2094 | 38 |

| Total identified | 98.37 | |||||

| Hydrocarbon monoterpenes | 2.22 | |||||

| Oxygenated monoterpenes | 28.94 | |||||

| Hydrocarbon sesquiterpenes | 11.7 | |||||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes | 34.3 | |||||

| Diterpenes hydrocarbons | 0.98 | |||||

| Diterpenes oxygenated | 20.23 |

| Experimental condition | Tm °C | ΔHm (J/g) |

| Blank NP | 54.29 | 429.63 |

| NP | 52.71 | 115.83 |

| Microorganism | EO (µg/mL) | NP (µg/mL) | VANCO (µg/mL) | ||||||

| S. aureus | MIC | MBC | BIC50 | MIC | MBC | BIC50 | MIC | MBC | BIC50 |

| 125 | 250 | 310 | 250 | 250 | 330 | 0.4 | - | 9.5 | |

| Drug | IC50 (µg/mL) |

| EO | <125 |

| NP | 533.96 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).