1. Introduction

Tissue engineering is an interdisciplinary field of medicine. To restore damaged tissues or organs, not only a cell source but also an extracellular matrix to support the cells is necessary. Modern regenerative medicine requires a variety of materials used as a scaffold for regenerating cells and biological dressings. Amniotic membrane is one of such materials. Biologically active substances contained in all layers of the amniotic membrane activate regenerative processes, promote cell proliferation, and accelerate cell migration [

1,

2]. When selecting an amniotic membrane as a scaffold for cell culture the most important qualities are its transparency, adhesive properties, and biodegradability [

3]. All of these properties are characteristic of the allogeneic amniotic membrane, making it the “gold standard” among the variety of biological scaffolds available [

4].

Native amniotic membrane is practically not used nowadays. For preserving allogeneic amniotic membrane there exist numerous methods, including cryopreservation, storage in various preservation media at temperatures between +4 °C and +8 °C, and lyophilization [

5,

6,

7]. Continuous advances in preservation technology lead to the development of new biomaterials based on allogeneic amniotic membrane that are easier to use and have a longer shelf life.

The amniotic membrane and the biological scaffold made from it are transparent and bioresorbable, allowing for monitoring of the pathological focus. At the same time, the biomaterial used for therapeutic intervention reacts with tissue in a specific way. In particular, the therapeutic effect of the biopolymer does not result in the formation of new vessels either on the surface or within the cornea, but it does activate proliferation and form a specific epithelial layer [

8,

9]. In contrast, in the process of skin and bone regeneration stimulating angiogenesis is important [

10].

Native amniotic membrane contains a range of biologically active substances, which are preserved to some extent during preservation [

11,

12,

13]. But taking into account the fact that native biomaterial is currently not used due to the risk of infecting recipients, but at the same time many researchers consider the amniotic membrane to be a “magic silk garment,” preserved biomaterial is used in regenerative medicine, either with preserved cellular structures or with impaired vitality [

14,

15].

The most common cryopreservation technique makes it possible to preserve both the cellular structures and the anatomical integrity of the amniotic membrane, thus retaining biologically active substances. Researchers believe that cryopreserved amniotic membrane prevents the formation of new vessels in the implantation area [

16,

17].

However, some researchers prefer to use decellularized lyophilized biomaterials. In this case there arise questions regarding the preservation of biologically active properties [

18,

19,

20].

Bearing in mind the Samara Tissue Bank’s experience in developing methods for lyophilization and decellularization of biological tissues, we have also worked out a method for processing and preserving amniotic membranes. Our method is based on physical decellularization methods and a special freeze-drying regimen [

21].

The aim of present research was to investigate the preservation of biologically active substances and morphologically evaluate their effectiveness in decellularized lyophilized amniotic membranes.

2. Materials and Methods

The study involved human amniotic membranes received by the tissue bank from a donor. The amniotic membrane was mechanically separated from the chorion and washed to remove blood clots in saline (0.9% NaCl, pH 5–7.5) for at least 30 minutes. Then the donor biomaterial fragments were divided into two groups. During pre-treatment, the first group of biomaterial fragments is placed in a 10% glycerol solution for 20 minutes, followed by 15 minutes of ultrasound at a frequency of 35±10% kHz. After that the fragments are placed in a chamber for 15 minutes under vacuum with a residual pressure of 1–2 Pa. Being removed from the chamber, the biomaterial is washed again in a 0.9% NaCl solution, frozen at -20 °C to -60 °C, lyophilized, hermetically sealed, and sterilized using radiation method (gamma rays or fast electrons).

The second group of biomaterial fragments, without prior glycerol impregnation, was also exposed to low-frequency ultrasound, placed in a vacuum chamber, and, after repeated washing and freezing, lyophilized. The lyophilized biomaterial was packaged in sealed bags and sterilized using radiation.

Proteomic analysis of three fragments from each group of lyophilized amniotic membrane was performed at the Federal Research Center “Fundamentals of Biotechnology” of the Russian Academy of Sciences. High-performance liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry was performed on an Impact II high-resolution quadrupole-TOF mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonik, Germany) equipped with an Apollo II electrospray ionization source (Bruker Daltonik, Germany). Elute ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography (Bruker Daltonik, Germany) was used on a Waters Acquity HSS reversed-phase column (Waters, Ireland). Spectral processing and protein identification were performed using BioPharma Compass 3.1.1 (Bruker Daltonik, Germany) and Mascot 2.8.1 (Matrix Science, UK) software packages.

The biologically active properties of the polymeric material were studied in an animal model. The research was carried out on 28 Wistar rats of both sexes, divided into two groups. When performing surgical interventions on animals, as well as their maintenance in the vivarium of the Research Institute of BioTech, Samara State Medical University, Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, we were guided by the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and other Scientific Purposes (ETS No. 123, Strasbourg, March 18, 1986); the “Principles of Good Laboratory Practice” of the Russian Federation National Standard GOST No. 33044-2014, introduced on August 1, 2015; and the “Sanitary and Epidemiological Requirements for the Design, Equipment, and Maintenance of Experimental Biological Clinics (Vivariums)” (SP 2.2.1.3218-14).

The following animal selection criteria were used: age 5-6 months, absence of disease. Before the experiment, the animals were kept in an isolation ward for 14 days and treated for ecto- and endoparasites. The rats were maintained under a balanced lighting regimen, with free access to water and standard laboratory chow. All animals underwent surgery between September and December 2023. All surgical interventions were performed under intramuscular anesthesia with a mixture of the anesthetics “Zoletil 100” (Virbac C.A., France) at a dosage of 0.5 mg/100 g of body weight and “Solutionis rometarum 20 mg/ml” (Bioveta, Czech Republic) at a dosage of 0.6 mg/100 g of body weight. The onset of surgical anesthesia was assessed by the presence of ciliary, corneal, and pedal reflexes. The experiment was performed in compliance with aseptic and antiseptic rules. After hair removal, the surgical field was treated with an antiseptic and isolated with sterile napkins. Scalpel was used to make a 1-1.5 cm long skin incision in the withers area. Blunt dissection was used to create a pocket into which a 2 × 2 cm fragment of lyophilized amniotic membrane was placed. The wound was tightly sutured. The animal was placed in a carrier with heating pads. After the surgery the rat’s condition was checked every 10 minutes. After the animal assumed a natural body and head position, it was transferred from the surgical unit to the permanent holding room. Physical examination in the cage was performed daily, and all abnormalities were recorded in the examination log. At the end of the experiment, the animal was sacrificed by intracardiac injection of an overdose of anesthetic. The excised tissue fragment from the implantation area was placed in fixative fluid (10% buffered formalin) at room temperature for 24-48 hours. After that histological preparations were made using standard techniques and stained with hematoxylin and eosin; hematoxylin and picrofuchsin.

The analysis of histological preparations was carried out using a visualization system based on an Olympus BX41 research microscope, a ProgRes CF color digital camera and a stationary computer, with the Morphology 5.2 software. This experiment was performed with the permission of the Bioethics Committee of Samara State Medical University (Extract from Protocol No. 206 dated March 18, 2020).

3. Results

The method of preserving amniotic membranes at our tissue bank, using freeze-drying with preliminary decellularization using physical stimulation, allows to store preserved biomaterial for 3 years at room temperature. Decellularization and freeze-drying, however, lead to structural changes and even possible denaturation of the proteins that provide biological activity of the native amniotic membrane [

22,

23,

24]. However, our previously performed Raman spectroscopy demonstrated the preservation of amides, polysaccharides, and other protein compounds. Comparative analysis of the Raman spectra revealed minimal differences between the spectra of native amniotic membrane and that of the biopolymer lyophilized without glycerol treatment, and significant differences with the spectra of the amniotic membrane treated with glycerol before lyophilization. The revealed changes in Raman spectroscopy concerned the degree of spectral intensity [

20].

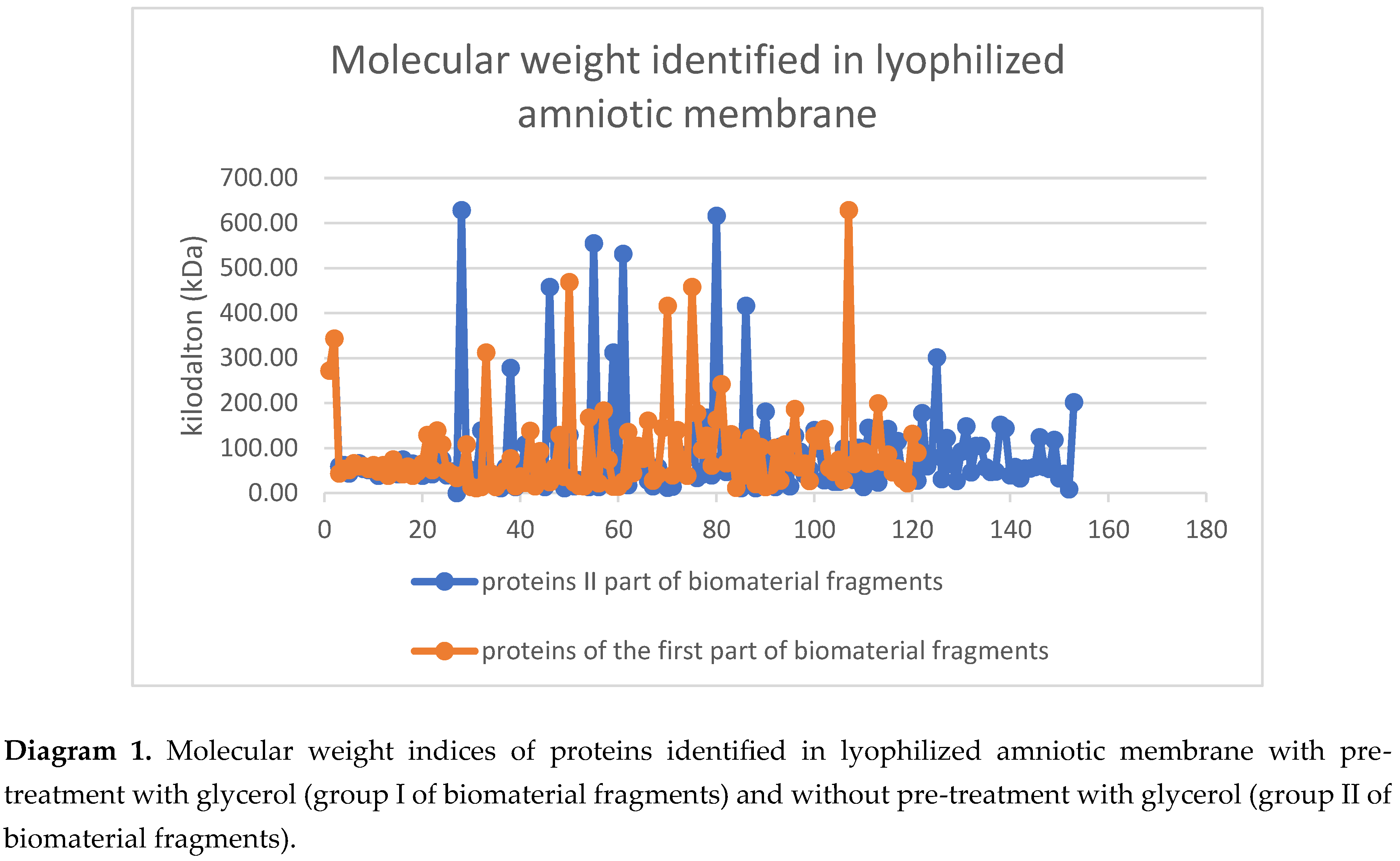

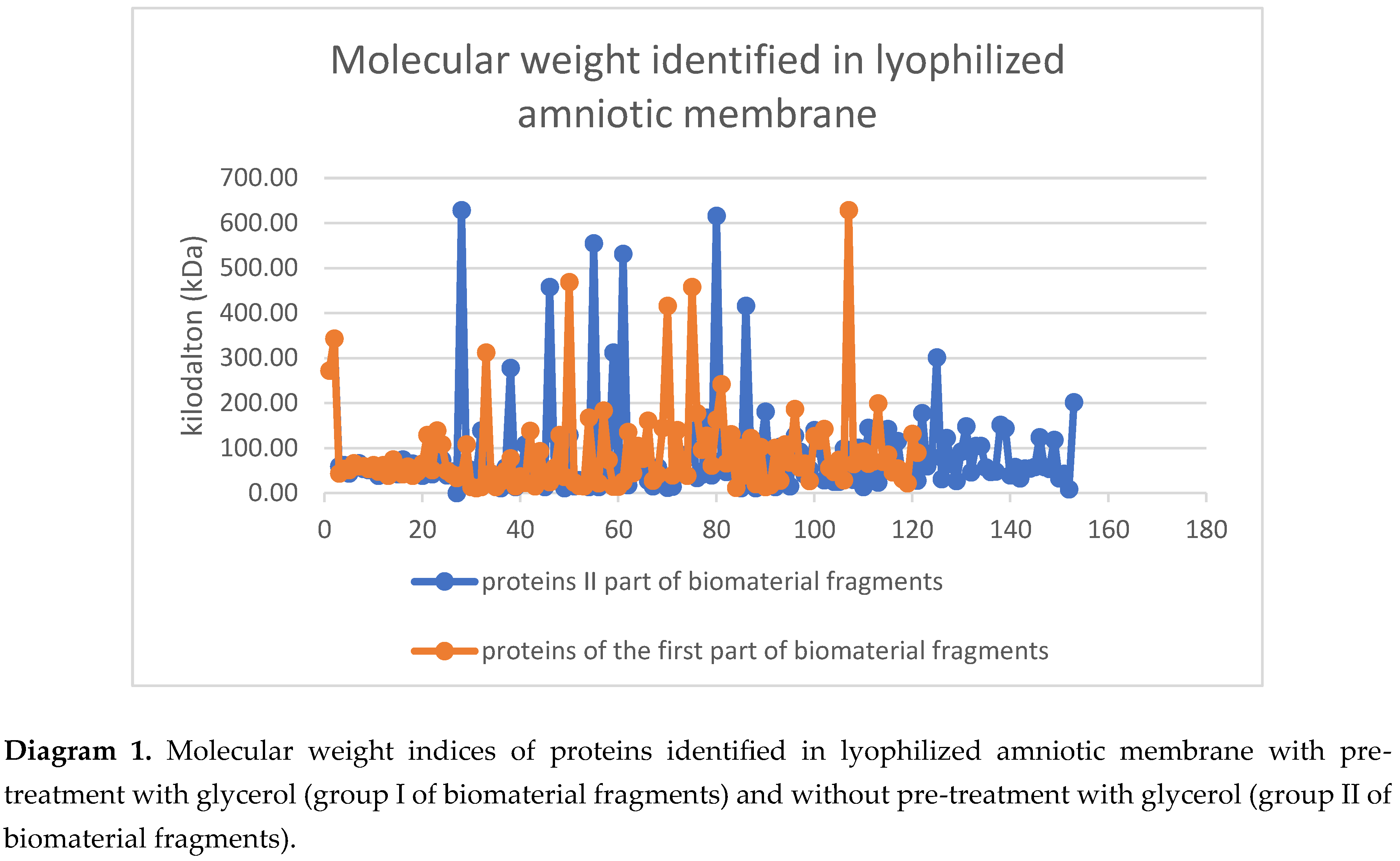

Comparative study of lyophilized amniotic membrane treated with glycerol (group I biomaterial fragments) and without treatment (group II biomaterial fragments) made it possible to identify different numbers of proteins. A total of 153 proteins with molecular weights ranging from 8.4 kDa to 628.7 kDa were identified with high reliability in human amniotic membranes not treated with glycerol prior to lyophilization. In contrast, 121 proteins with molecular weights ranging from 11.4 kDa to 628.7 kDa were identified in amniotic membranes treated with glycerol prior to lyophilization.

The wide range of molecular weights of the proteins present is explained by the diversity of protein compounds detected in the biomaterial fragments. A slight disparity in the dispersion of molecular weights between Group I and Group II biomaterial fragments is noted. This demonstrates once again that the protein compositions of the glycerol-treated and untreated samples differ significantly. In Group I, 88 protein structures were not identified among those present in Group II. Accordingly, 28 proteins present in fragments soaked in glycerol prior to lyophilization are not found in the lyophilized amniotic membrane samples not treated with glycerol.

Considering that both groups of biomaterial were subjected to physical stress resulting in the destruction of cellular structures and differ only in that Group I was treated with glycerol, it is likely that all proteins present in the nuclei, cytoplasm, or integrated into the cell membrane ended up in the extracellular matrix [

20,

25]. The lower number of identified proteins in the structure of lyophilized amniotic membrane samples treated with glycerol is explained by the stabilizing function of glycerol, which, when interacting with proteins, forms three-dimensional structures and changes the characteristics of protein compounds [

25,

26]. These processes are also likely to explain the difference in molecular weight values between Group I and Group II of the biomaterial fragments (Tables 1 and 2).

The significant difference in proteomic composition identified in these groups is likely to be responsible for the differences in the biological properties of the decellularized lyophilized amniotic membrane.

We studied the biological properties of biopolymers treated with different methods using a classical experiment by implanting biomaterial fragments into a pocket formed in the withers of two groups of animals. Daily physical examination of the experimental animals in the post-operation period revealed no significant changes in their physical condition. One animal developed suppuration and postoperative wound dehiscence. When tissue was being collected from this animal, the implanted biomaterial could not be detected macroscopically, and histological examination was not performed. The animals were sacrificed on the 12th post-operation day, and the excised tissue fragments containing the implanted biopolymer were subjected to morphological examination.

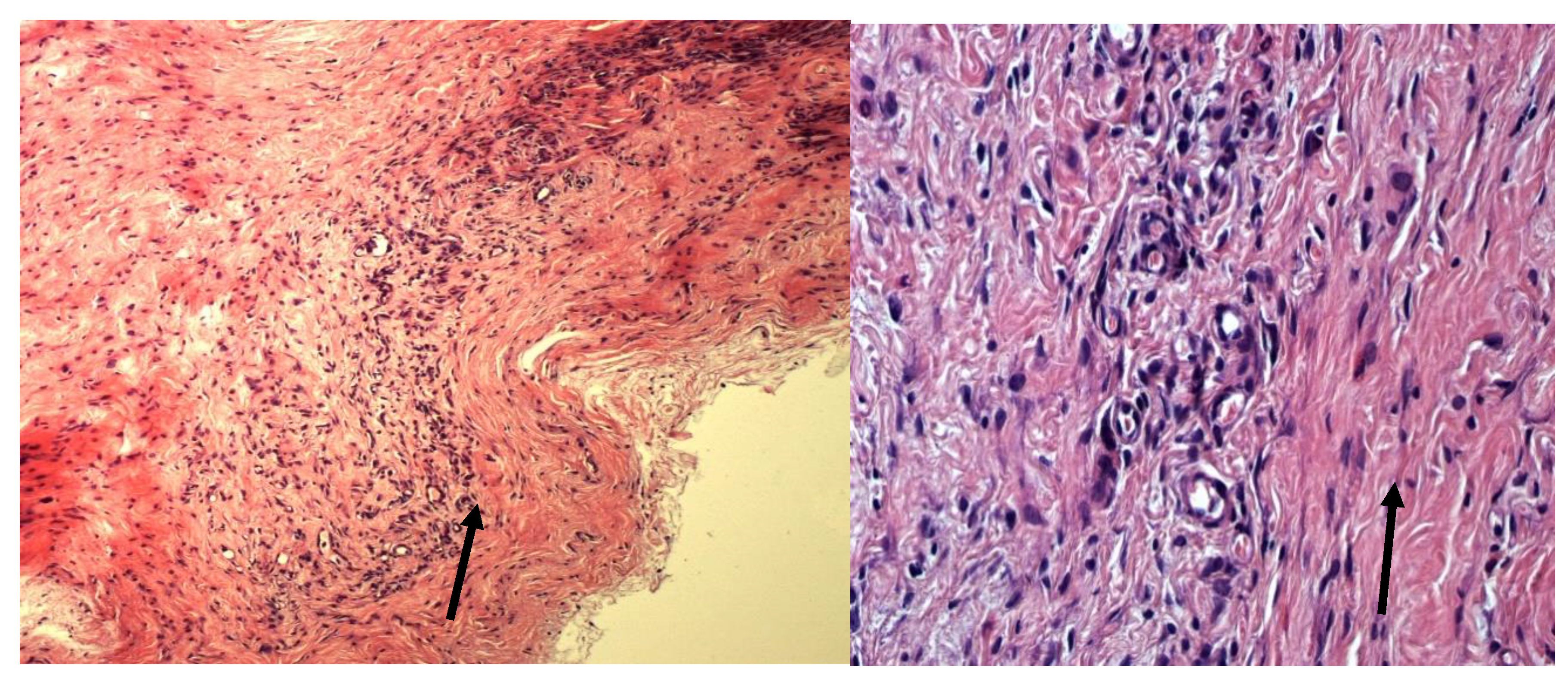

As a result of histological examination, we obtained convincing evidence of the different effects on the tissue around the implanted fragments of lyophilized amniotic membrane treated with glycerin (Group I) (

Figure 1) and amniotic membrane fragments not treated with glycerin prior to lyophilization (Group II).

Lyophilized amniotic membrane on tissue slides from animals in Group I (the biomaterial was treated with glycerin before lyophilization) is clearly visible, its fibrous structure is preserved, and slight edema is noted. The surrounding tissues are slightly edematous and infiltrated with sporadic mast cells, macrophages, and fibroblasts. Isolated blood-filled vessels are present (

Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Histological preparation of the implantation zone of a fragment of lyophilized amniotic membrane treated with glycerin. Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification A—100x. B—400x. The arrow indicates the preserved amniotic membrane.

Figure 1.

Histological preparation of the implantation zone of a fragment of lyophilized amniotic membrane treated with glycerin. Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification A—100x. B—400x. The arrow indicates the preserved amniotic membrane.

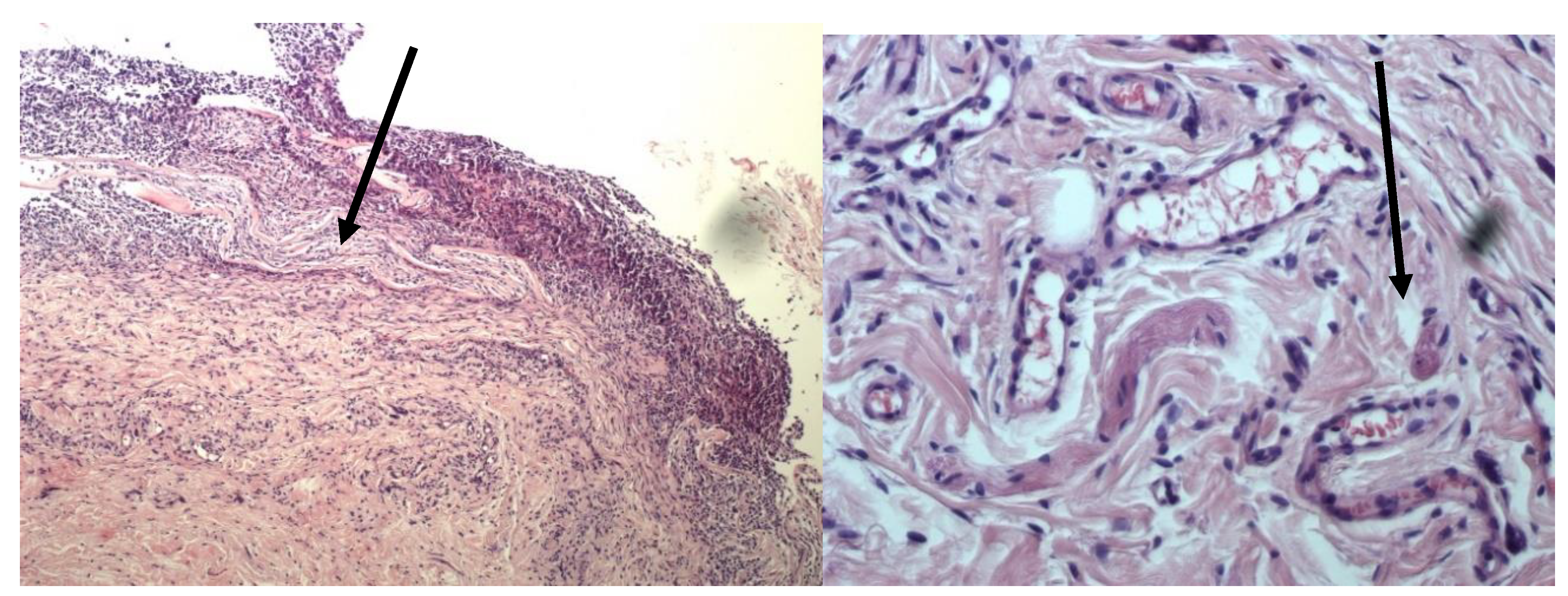

Figure 2.

Histological preparation of the implantation zone of a fragment of lyophilized amniotic membrane without glycerol treatment. Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification A—100x. B—400x. The arrow indicates the amniotic membrane being replaced.

Figure 2.

Histological preparation of the implantation zone of a fragment of lyophilized amniotic membrane without glycerol treatment. Stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Magnification A—100x. B—400x. The arrow indicates the amniotic membrane being replaced.

Group II specimens (biomaterial not treated with glycerin before lyophilization) demonstrate more pronounced lysis and replacement of lyophilized amniotic membrane, as well as macrophage infiltration. The surrounding tissues are infiltrated with a large number of mast cells. Numerous newly formed vessels are also observed.

4. Discussion

A distinctive feature of the biomaterial pre-processing technology at the tissue bank of the Research Institute of Biotechnology, Samara State Medical University, is the use of physical methods. The main difference between the processing of the two groups of amniotic membrane fragments obtained from the same donor was the treatment of group I fragments with glycerin. Glycerin is often used for preserving amniotic membrane [

6,

7,

17,

22]. At the same time, many researchers point to the ability of amniotic membrane to inhibit neoangiogenesis [

8,

9].

The variations we identified in the proteome composition of the fragments studied revealed significant differences. In Group I biomaterial fragments, 80 protein structures, present in Group II, were not identified. Accordingly, lyophilized amniotic membrane samples not treated with glycerol lack 47 proteins identified in fragments soaked in glycerol prior to lyophilization (Tables 1 and 2).

The majority of identified proteins in Group I biomaterial fragments were classified as intracellular—70 proteins (57.8%), while 51 proteins (42.2%) were classified as extracellular. The majority of identified proteins in Group II biomaterial fragments (not soaked in glycerol prior to lyophilization) were intracellular—97 proteins (63.4%), while the proportion of extracellular proteins was 56 proteins (36.6%). Taking into account the fact that both groups of biomaterial were subjected to physical impact, which resulted in the destruction of cellular structures, it is likely that proteins present in the nuclei, cytoplasm or were integrated into the cell membrane ended up in the extracellular matrix [

11,

14,

15]. The smaller number of identified proteins in the structure of lyophilized amniotic membrane samples treated with glycerol is explained by the stabilizing function of glycerol, which, interacting with proteins, forms three-dimensional structures, changes the characteristics of protein compounds and prevents them from interacting with other substances [

11,

25,

26]. The results of the morphological study showed a more pronounced reaction to the biopolymer without the use of glycerol in its preparation. In particular, in the micropreparations of the 1st study group, there is significantly less infiltration by mast cells and no newly formed vessels are observed. Whereas on the micropreparations where the biopolymer not impregnated with glycerin was implanted, there was significant infiltration of mast cells and numerous newly formed vessels.

Protein analysis revealed that in the glycerol-impregnated biopolymer fragments there are 13 proteins directly regulating angiogenesis. According to data from the open-source PANTHER and neXtProt resources, six proteins are inducers, and seven proteins inhibit angiogenesis [

27,

28] (Tables 3 and 4).

Fragments of lyophilized amniotic membrane not treated with glycerol also revealed 13 proteins involved in the regulation of angiogenesis, eight of which are inducers, and five are inhibitors.

Both groups I and II samples contain similar proteins, including angiogenesis mediators—Annexin A1, 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta, Annexin A2 (ANXA2), Tenascin-X, and Transforming growth factor-beta-induced protein βig-h3 (Beta βig-h3)—and angiogenesis inhibitors—Thrombospondin-1; Collagen alpha-2(IV) chain; Fibronectin; and Decorin.

At the same time, only lyophilized amniotic membrane pre-treated with glycerol contains Collagen alpha-1(IV) chain (COL4A1), which is also an angiogenesis inhibitor. Collagen chains α1(IV) and α2(IV) are present in the basement membranes of all tissues and are an important component in cell adhesion and differentiation. The interaction of these proteins is crucial for many biological processes including migration, survival, and angiogenesis [

15,

16,

17,

19,

29,

30,

31,

32].

As far back as the end of the 18th century, Hunter presented angiogenesis as a complex multi-stage process comprising four stages: proteolytic destruction of the vascular basement membrane and intercellular matrix, migration and attachment of endothelial cells, their proliferation, and, finally, the formation of tubular structures [

29,

30]. While analyzing proteins identified in lyophilized amniotic membrane, we found proteins potentially involved in all stages of angiogenesis.

The groups of proteins modulating the angiogenic process of lyophilized amniotic membrane pre-treated with glycerol and without treatment with glycerol, identified from the entire proteomic package, differ significantly. As we found, group I fragments contains more proteins inhibiting angiogenesis, while group II fragments contains fewer proteins. A higher concentration of angiogenesis-activating proteins was detected in lyophilized amniotic membrane fragments not treated with glycerol.

5. Conclusions

Our study demonstrates more pronounced biological properties of the biopolymer not treated with glycerol prior to preservation, that reveal themselves in significant mast cell infiltration and neoangiogenesis.

Consequenly, for specific application of the biopolymer it is important to consider which preparation and preservation method is used.

Author Contributions

Evgeny S. Milyudin—E.S.M. writing—original draft preparation, review preparation, editing, revision, Alexander V. Kolsanov—Conceptualization, project administration, construction of experiments methodology, processing and interpreting the received results of the study. Ksenia E. Kuchuk—Production of lyophilized amniotic membrane biomaterial, interpreting the received experimental results, K.E.K.; Joseph V. Novikov—Construction of experiments methodology processing of the obtained experimental data; formal analysis. Larisa T. Volova—writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee (extract 18.03.2020 no.206 of the meeting of the Committee on Bioethics of Samara State Medical University).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions eg privacy and ethical.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Meller D, Pires RT, Mack RJ, Figueiredo F, Heiligenhaus A, Park WC, Prabhasawat P, John T, McLeod SD, Steuhl KP, Tseng SC. Amniotic membrane transplantation for acute chemical or thermal burns. Ophthalmology. 2000 May;107(5):980-9; discussion 990. PMID: 10811094. [CrossRef]

- Niknejad H, Peirovi H, Jorjani M, Ahmadiani A, Ghanavi J, Seifalian AM. Properties of the amniotic membrane for potential use in tissue engineering. Eur Cells Mater. 2008;15:88–99.

- Tsai R., Li L., Chan J. Reconstruction of damaged corneas by transplantation of autologous limbal epithelial cells. N. Engl. J. Med; 2000.

- Nakamura T, Inatomi T, Sotozono C, et al. Ocular surface reconstruction using stem cell and tissue engineering. Progress in retinal and eye research 2016; 51: 187–207.

- Koizumi N., Fullwood N., Bairaktaris G., et al. Cultivasion of corneal epithelial cells on intact and denuded human amniotic membrane. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2000; 41.

- Adds P. J., Hunt C. J., Dart J. K. G. Amniotic membrane grafts, “fresh” or frozen? A clinical and in vitro comparison//Br J Ophthalmol 2001;85:905-907.

- Milyudin E.S. Technology of preservation of amniotic membrane by drying over silica gel//Technologies of living systems 2006. Vol.—3. No. -3. -P.44-50.

- Kim JC, Tseng SC. The effects on inhibition of corneal neovascularization after human amniotic membrane transplantation in severely damaged rabbit corneas. Korean J Ophthalmol. 1995 Jun;9(1):32-46. PMID: 7674551. [CrossRef]

- Shao C, Sima J, Zhang SX, Jin J, Reinach P, Wang Z, Ma JX. Suppression of corneal neovascularization by PEDF release from human amniotic membranes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004 Jun;45(6):1758-62. PMID: 15161837. [CrossRef]

- Liu J, Yang L, Liu K and Gao F (2023) Hydrogel scaffolds in bone regeneration: Their promising roles in angiogenesis. Front. Pharmacol. 14:1050954. [CrossRef]

- Hodde, J. P. Vascular endothelial growth factor in porcine-derived extracellular matrix/J. P. Hodde, R. D. Record, H. A. Liang, S. F. Badylak//Endothelium.—2001.—№ 8 (1).—P. 10–15.

- Gilbert, T. W. Decellularization of tissues and organs/T. W. Gilbert, T. L. Sellaro, S. F. Badylak//Biomaterials.—2006.—№ 27 (19). – P. 3532–3537.

- Niknejad H, Peirovi H, Jorjani M, Ahmadiani A, Ghanavi J, Seifalian AM. Properties of the amniotic membrane for potential use in tissue engineering. Eur Cell Mater. 2008 Apr 29;15:88-99. PMID: 18446690. [CrossRef]

- Portmann-Lanz CB, Ochsenbein-Kölble N, Marquardt K, Lüthi U, Zisch A, Zimmermann R. Manufacture of a cell-free amnion matrix scaffold that supports amnion cell outgrowth in vitro. Placenta. 2007 Jan;28(1):6-13. Epub 2006 Mar 3. PMID: 16516964. [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Torres JR, Martínez-González SB, Lozano-Luján AD, Martínez-Vázquez MC, Velasco-Elizondo P, Garza-Veloz I, et al. Biological properties and surgical applications of the human amniotic membrane. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. (2023) 10:1–20. [CrossRef]

- Koizumi NJ, Inatomi TJ, Sotozono CJ, Fullwood NJ, Quantock AJ, Kinoshita S. Growth factor mRNA and protein in preserved human amniotic membrane. Curr Eye Res. 2000 Mar;20(3):173-7. PMID: 10694891.

- Roy I, Gupta MN. Freeze-drying of proteins: some emerging concerns. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. 2004 Apr;39(Pt 2):165-77. PMID: 15032737. [CrossRef]

- López-Valladares MJ, Touriño R, Vieites B, Gude F, Silva MT, Couceiro J. Effects of lyophilization on human amniotic membrane. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009 Jun;87(4):396-403. Epub 2008 Oct 15. PMID: 18937812. [CrossRef]

- Hopkinson A, McIntosh RS, Shanmuganathan V, Tighe PJ, Dua HS. Proteomic analysis of amniotic membrane prepared for human transplantation: characterization of proteins and clinical implications. J Proteome Res. 2006 Sep;5(9):2226-35. PMID: 16944934. [CrossRef]

- Milyudin, E.; Volova, L.T.; Kuchuk, K.E.; Timchenko, E.V.; Timchenko, P.E. Amniotic Membrane Biopolymer for Regenerative Medicine. Polymers 2023, 15, 1213. [CrossRef]

- Volova L.T., Milyudin E.S., Kuchuk K.E. Method for preparing allogeneic amniotic membrane for reconstructive medicine. Russian Federation Patent No. 2835347.

- Andri K. Riau, Roger W. Beuerman, Laurence S. Lim, Jodhbir S. Mehta Preservation, sterilization and de-epithelialization of human amniotic membrane for use in ocular surface reconstruction Biomaterials, Volume 31, Issue 2,2010,Pages 216-225,ISSN 0142-9612. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0142961209009648). [CrossRef]

- Ingraldi, A.L.; Audet, R.G.; Tabor, A.J. The Preparation and Clinical Efficacy of Amnion-Derived Membranes: A Review. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 531. [CrossRef]

- Redl, H., Wolbank, S., & Hennerbichler, S. (2009). Impact of human amniotic membrane preparation on release of angiogenic factors. J Tissue Eng Regen Med 2009; 3: 651–654. [CrossRef]

- Bukhdruker S, Varaksa T, Orekhov P, Grabovec I, Marin E, Kapranov I, Kovalev K, Astashkin R, Kaluzhskiy L, Ivanov A, Mishin A, Rogachev A, Gordeliy V, Gilep A, Strushkevich N, Borshchevskiy V. Structural insights into the effects of glycerol on ligand binding to cytochrome P450. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol. 2023 Jan 1;79(Pt 1):66-77. Epub 2023 Jan 1. PMID: 36601808. [CrossRef]

- Zahn-Zabal M, Michel PA, Gateau A, Nikitin F, Schaeffer M, Audot E, Gaudet P, Duek Roggli P, Teixeira D, Rech de Laval V, Samarasinghe K, Bairoch A, Lane L. The neXtProt knowledgebase in 2020: data, tools and usability improvements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020 Jan 8;48 (D1):D328-D334.

- 27. The UniProt Consortium UniProt: the Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023 Nucleic Acids Res. 51:D523–D531 (2023).

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology knowledgebase in 2023. Genetics. 2023 May 4;224 (1):iyad031. [CrossRef]

- Zhang F, Zhang L, Zhang B, Wei X, Yang Y, Qi RZ, Ying G, Zhang N, Niu R. Anxa2 plays a critical role in enhanced invasiveness of the multidrug resistant human breast cancer cells. J Proteome Res. 2009 Nov;8(11):5041-7. PMID: 19764771. [CrossRef]

- Sharma MR, Koltowski L, Ownbey RT, Tuszynski GP, Sharma MC. Angiogenesis-associated protein annexin II in breast cancer: selective expression in invasive breast cancer and contribution to tumor invasion and progression. Exp Mol Pathol. 2006 Oct;81(2):146-56. Epub 2006 Apr 27. PMID: 16643892. [CrossRef]

- Sharma M, Ownbey RT, Sharma MC. Breast cancer cell surface annexin II induces cell migration and neoangiogenesis via tPA dependent plasmin generation. Exp Mol Pathol. 2010 Apr;88(2):278-86. Epub 2010 Jan 15. PMID: 20079732. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Guo B, Zhang Y, Cao J, Chen T. Silencing of the annexin II gene down-regulates the levels of S100A10, c-Myc, and plasmin and inhibits breast cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Saudi Med J. 2010 Apr;31(4):374-81. PMID: 20383413.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).