Submitted:

04 December 2025

Posted:

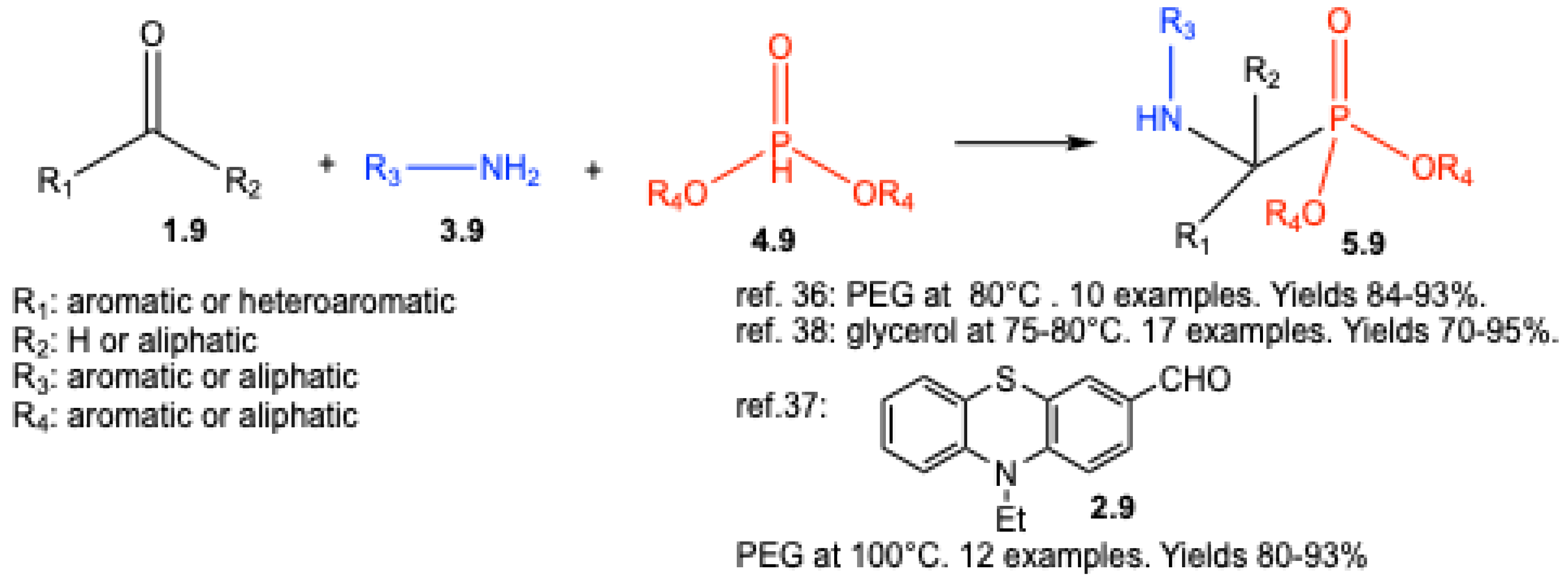

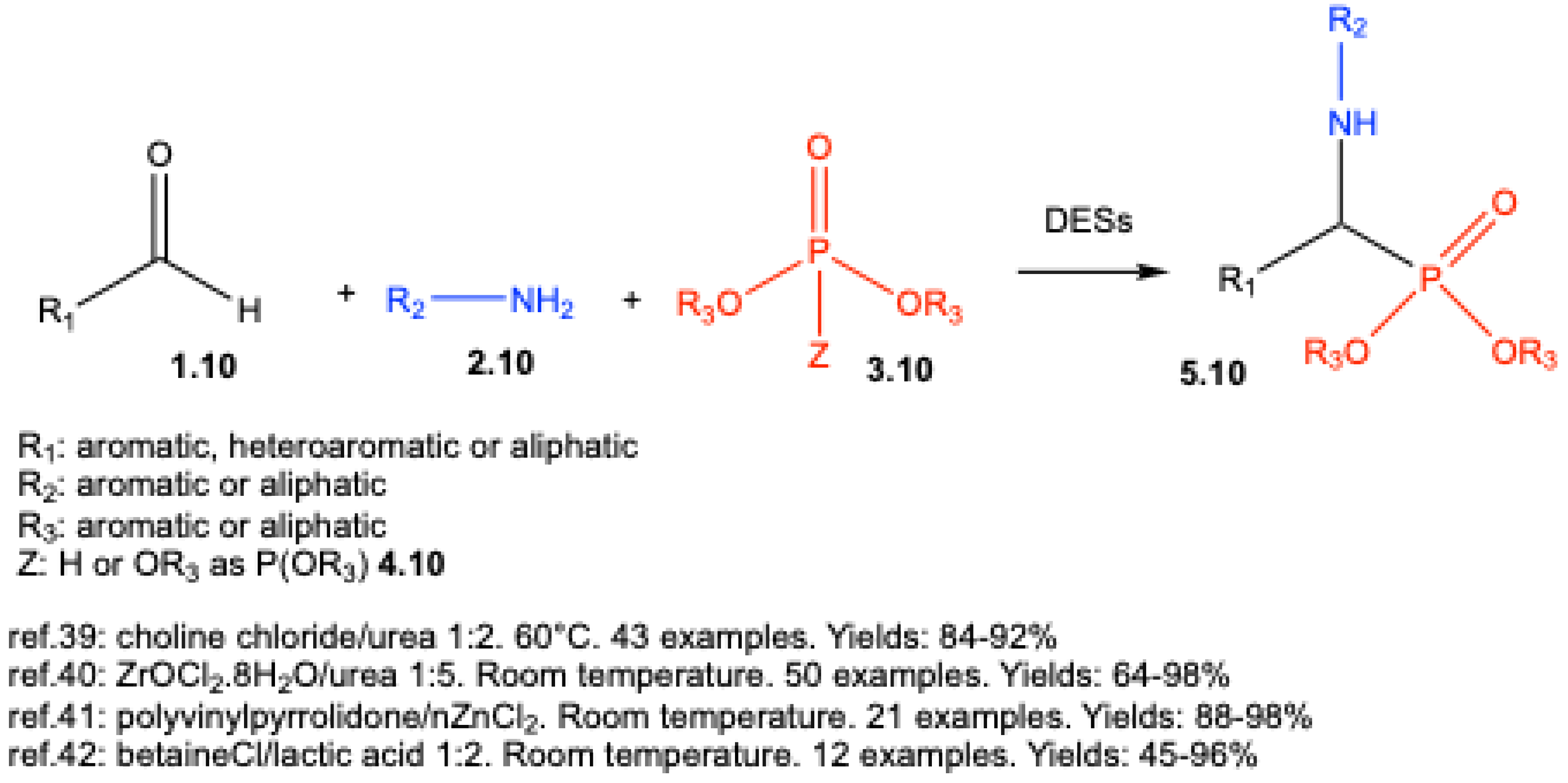

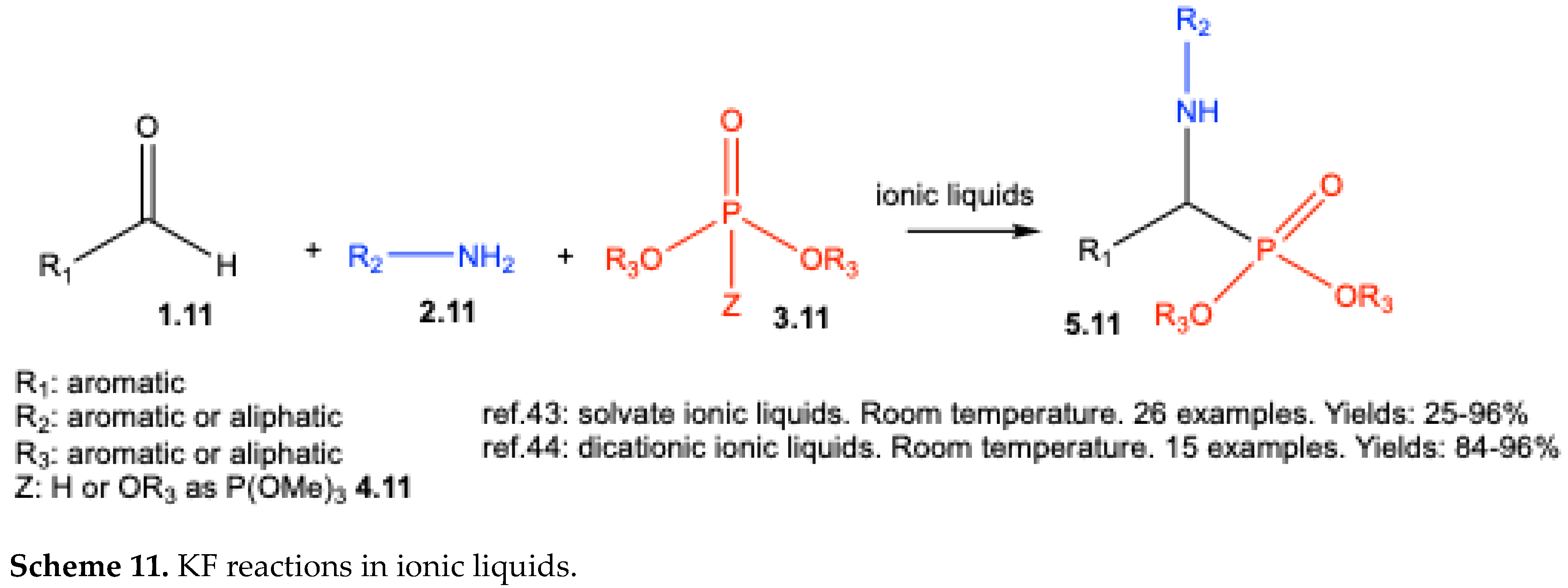

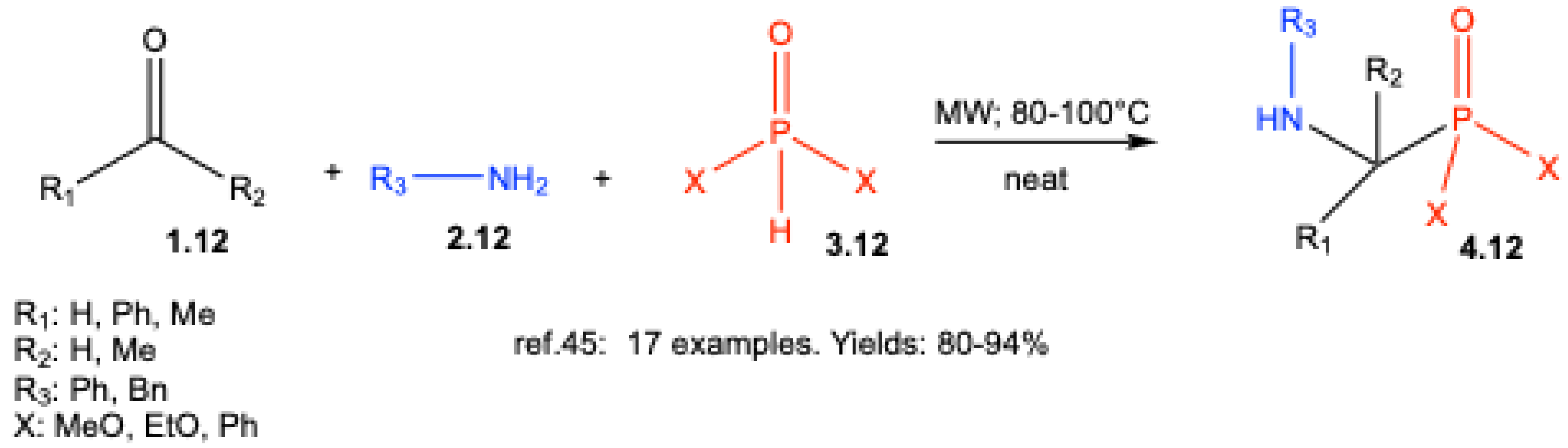

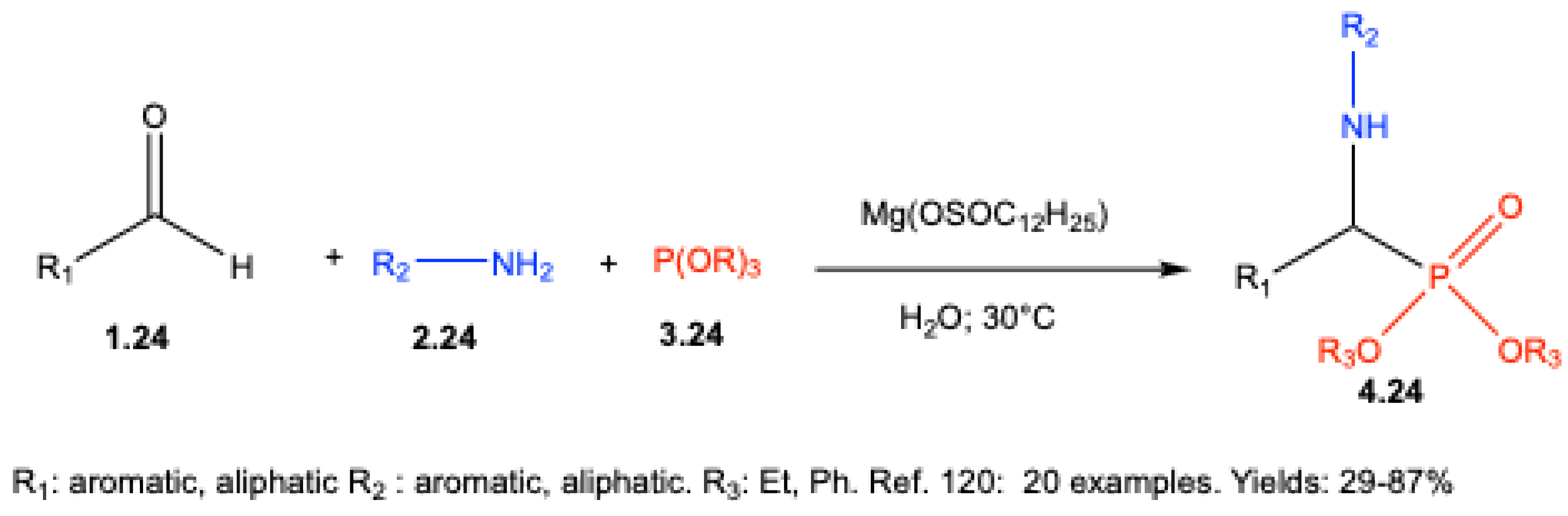

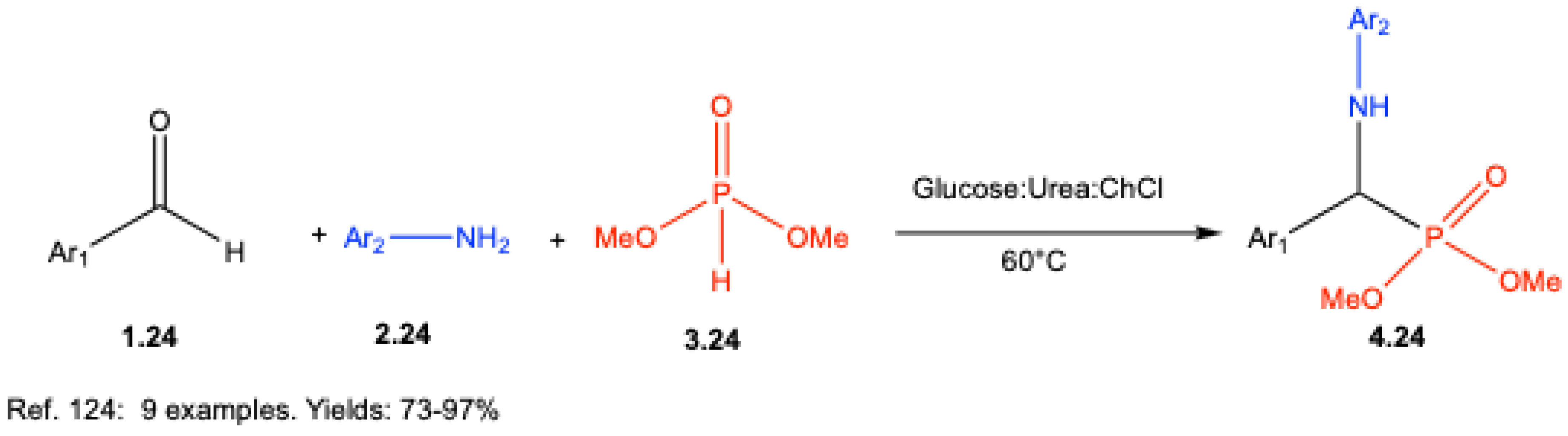

05 December 2025

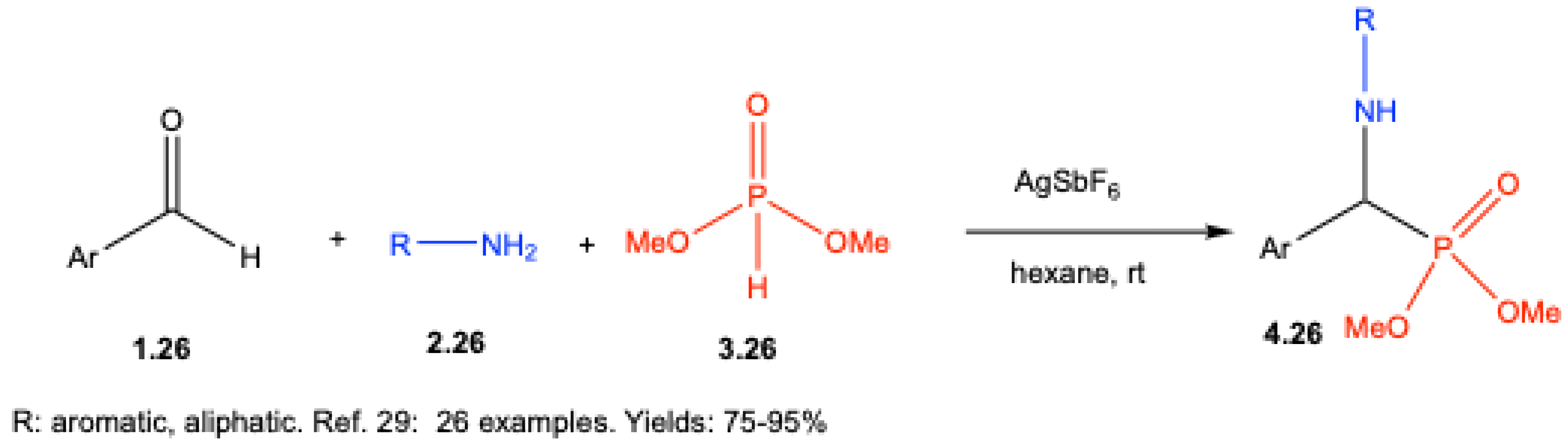

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

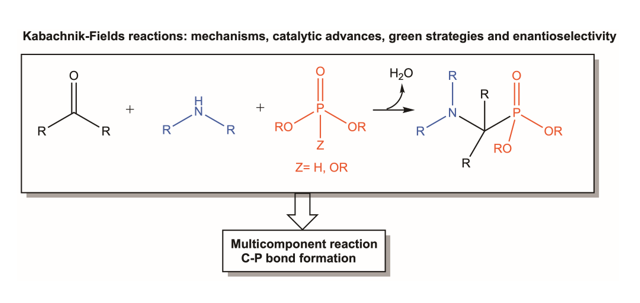

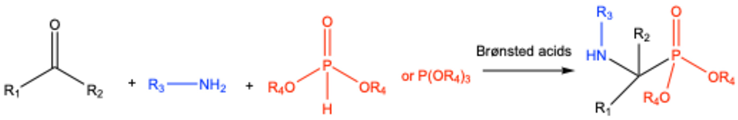

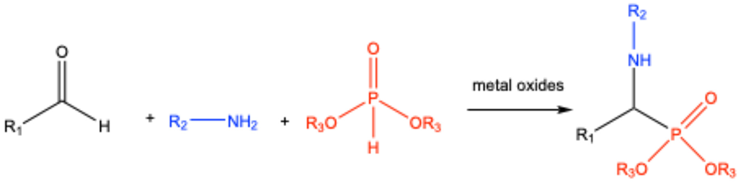

1. Introduction

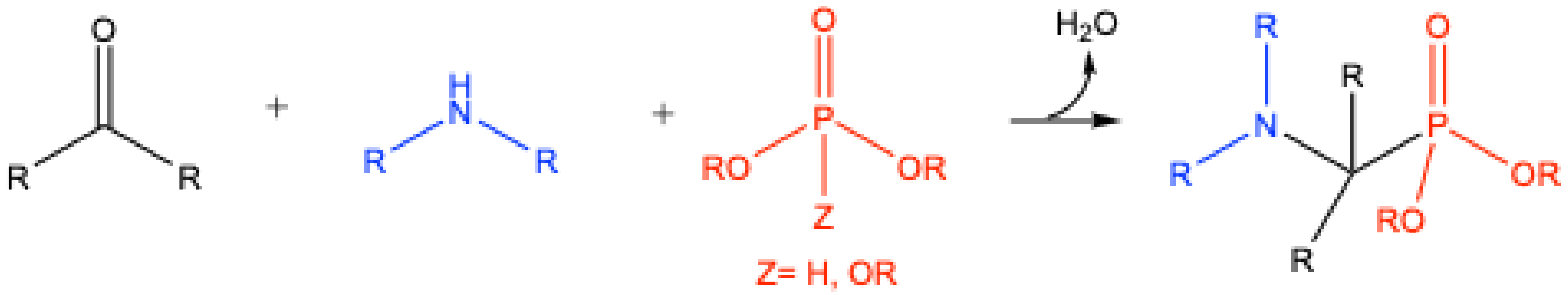

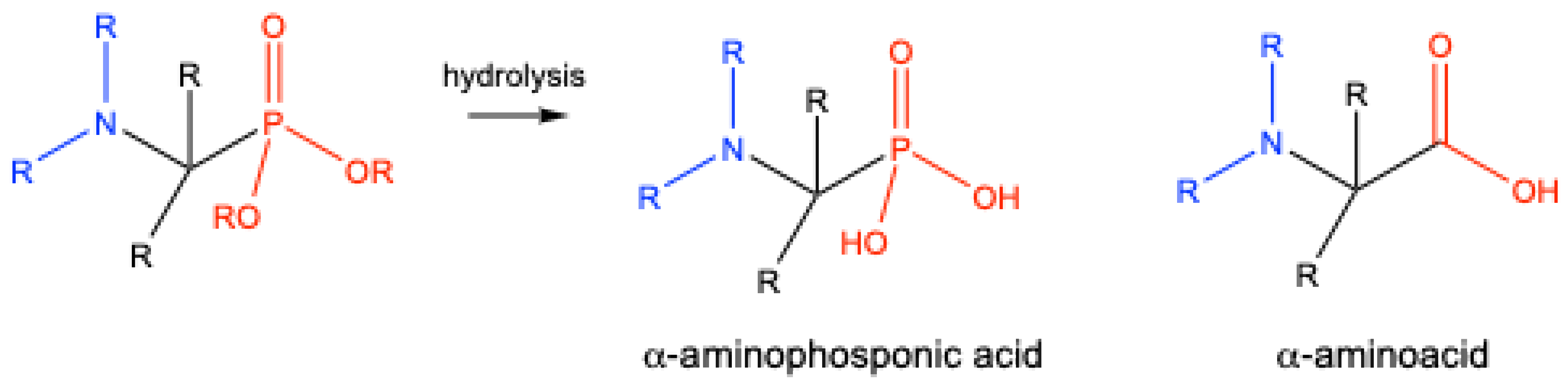

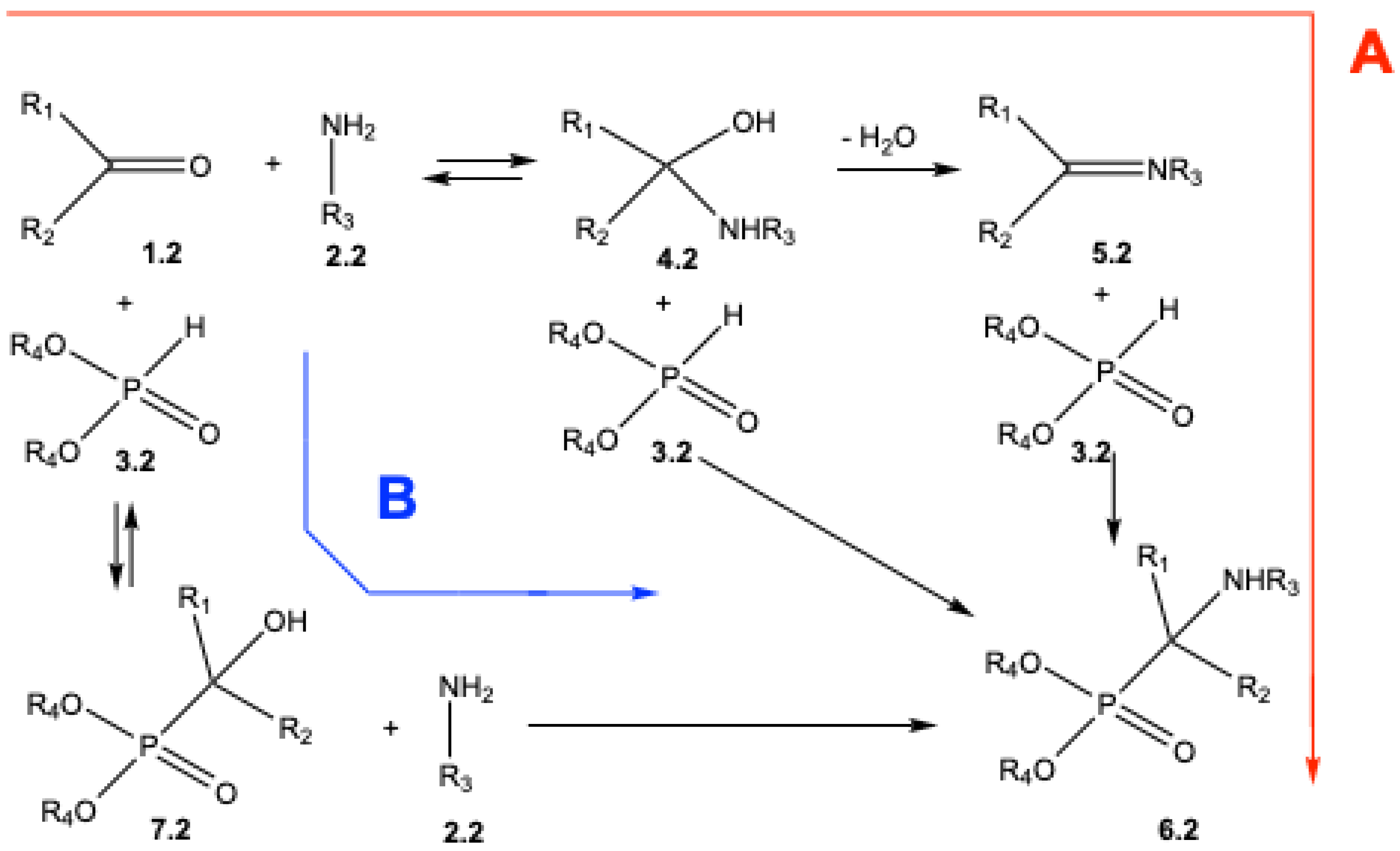

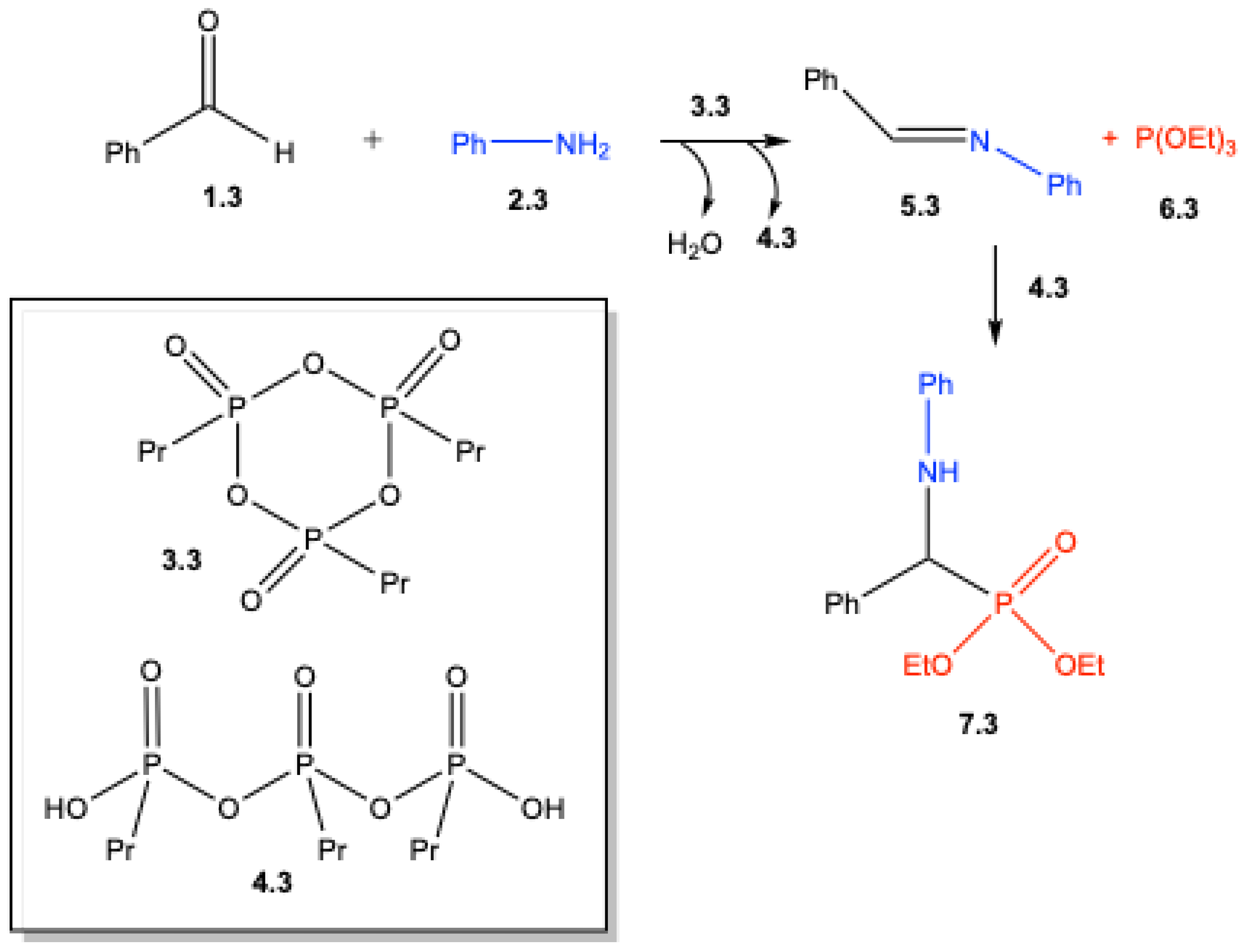

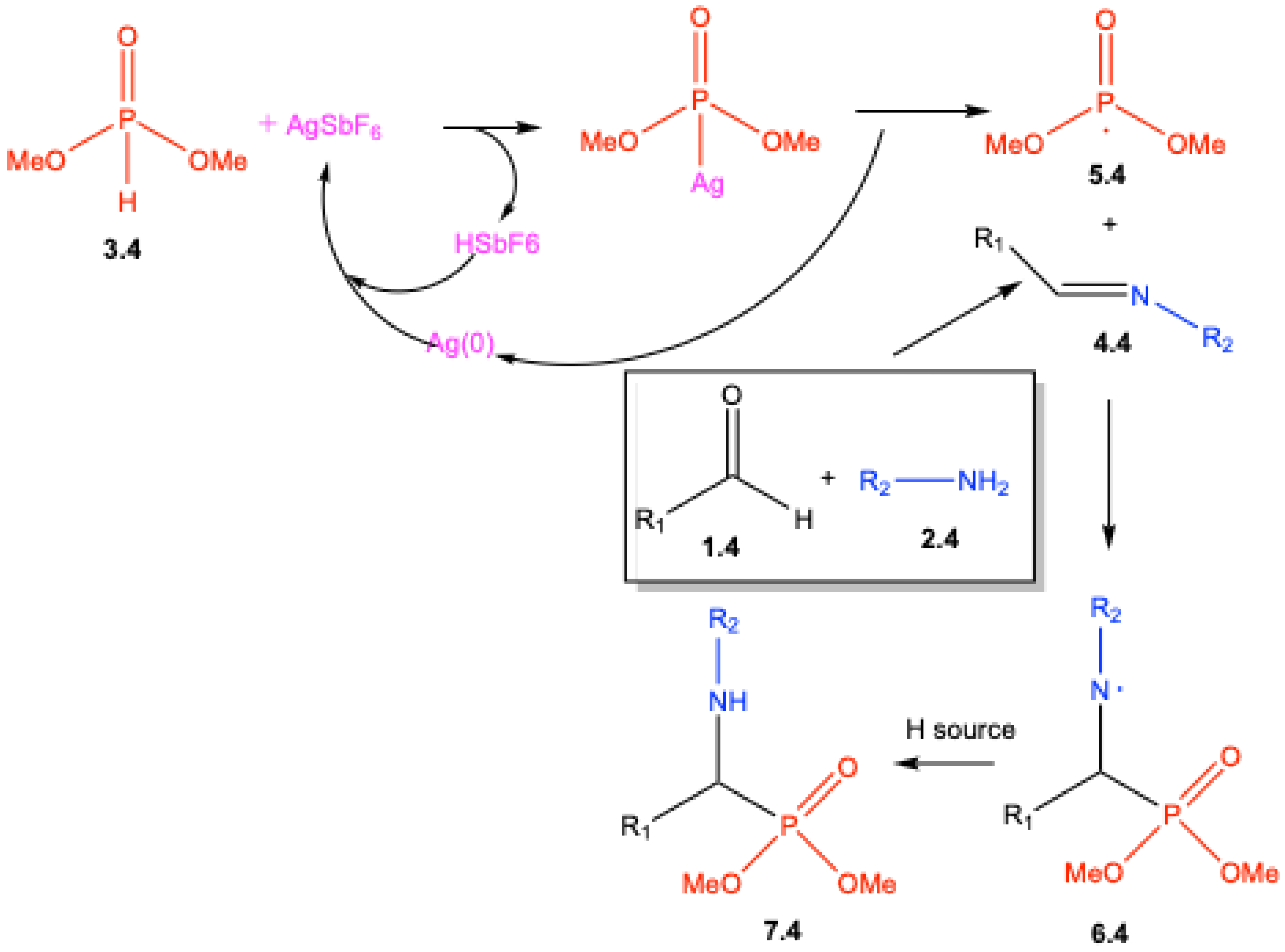

2. Mechanistic Studies

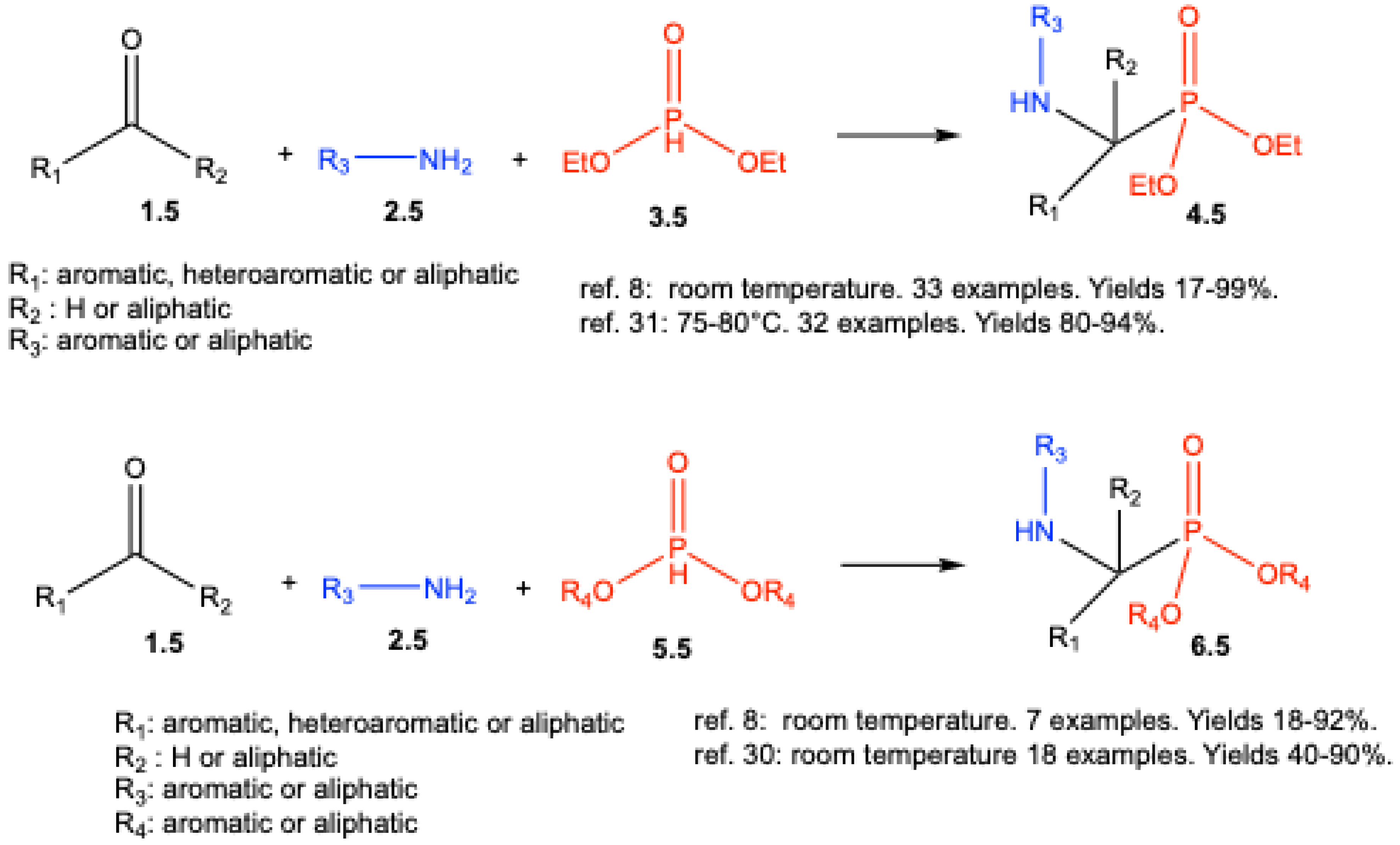

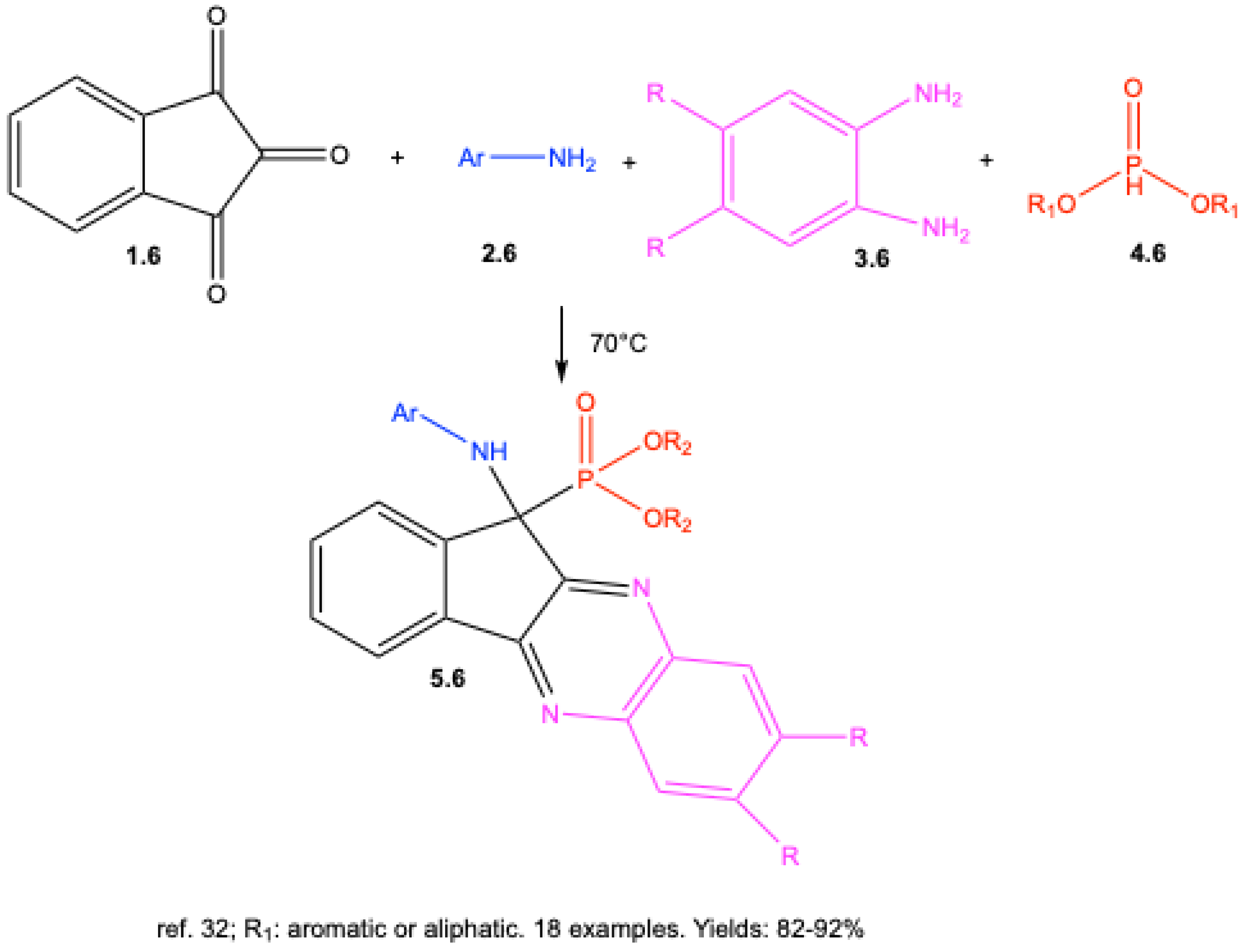

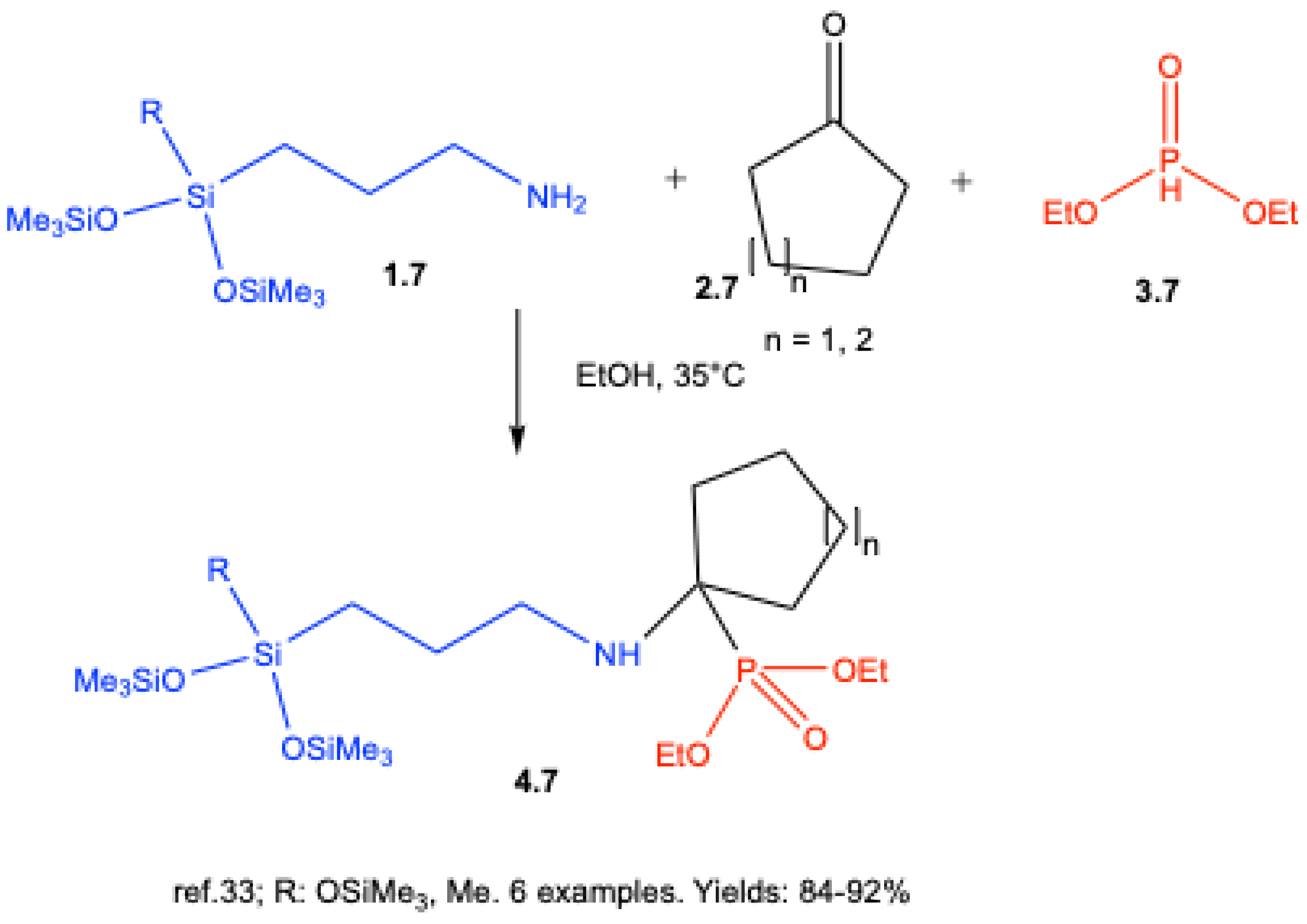

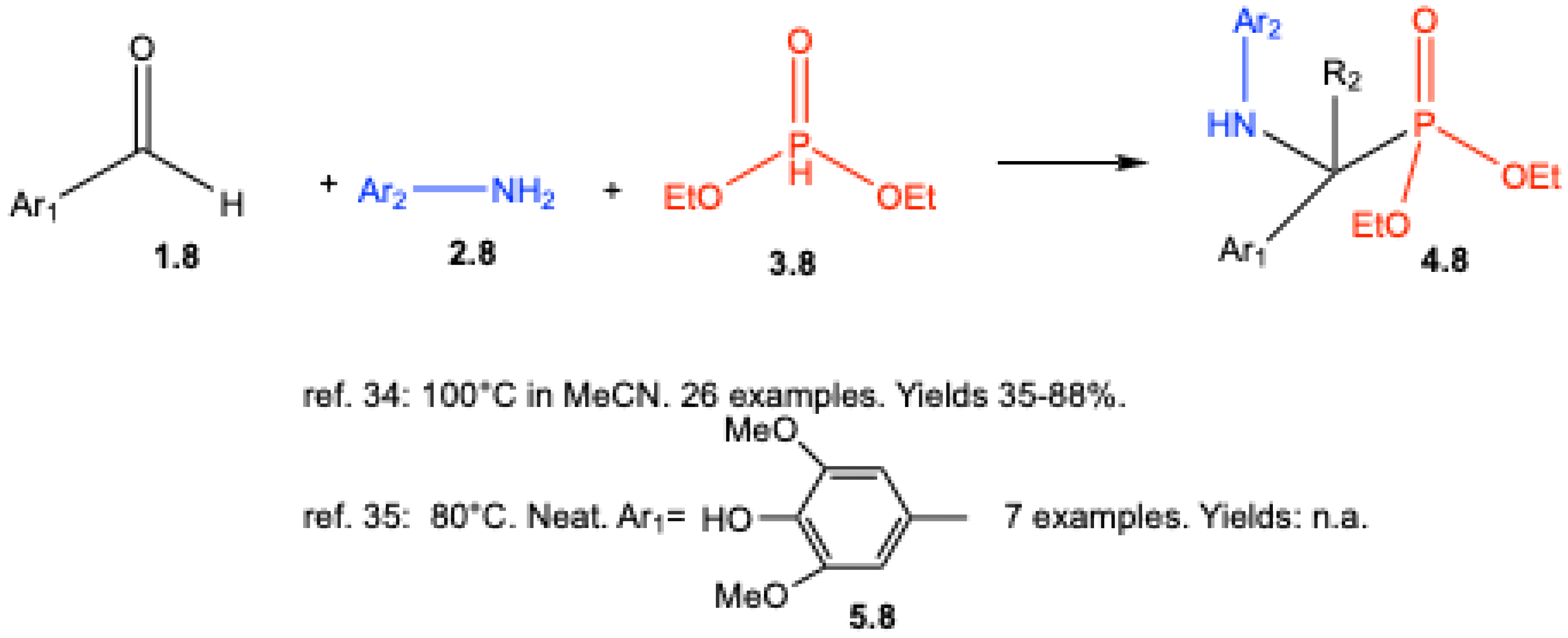

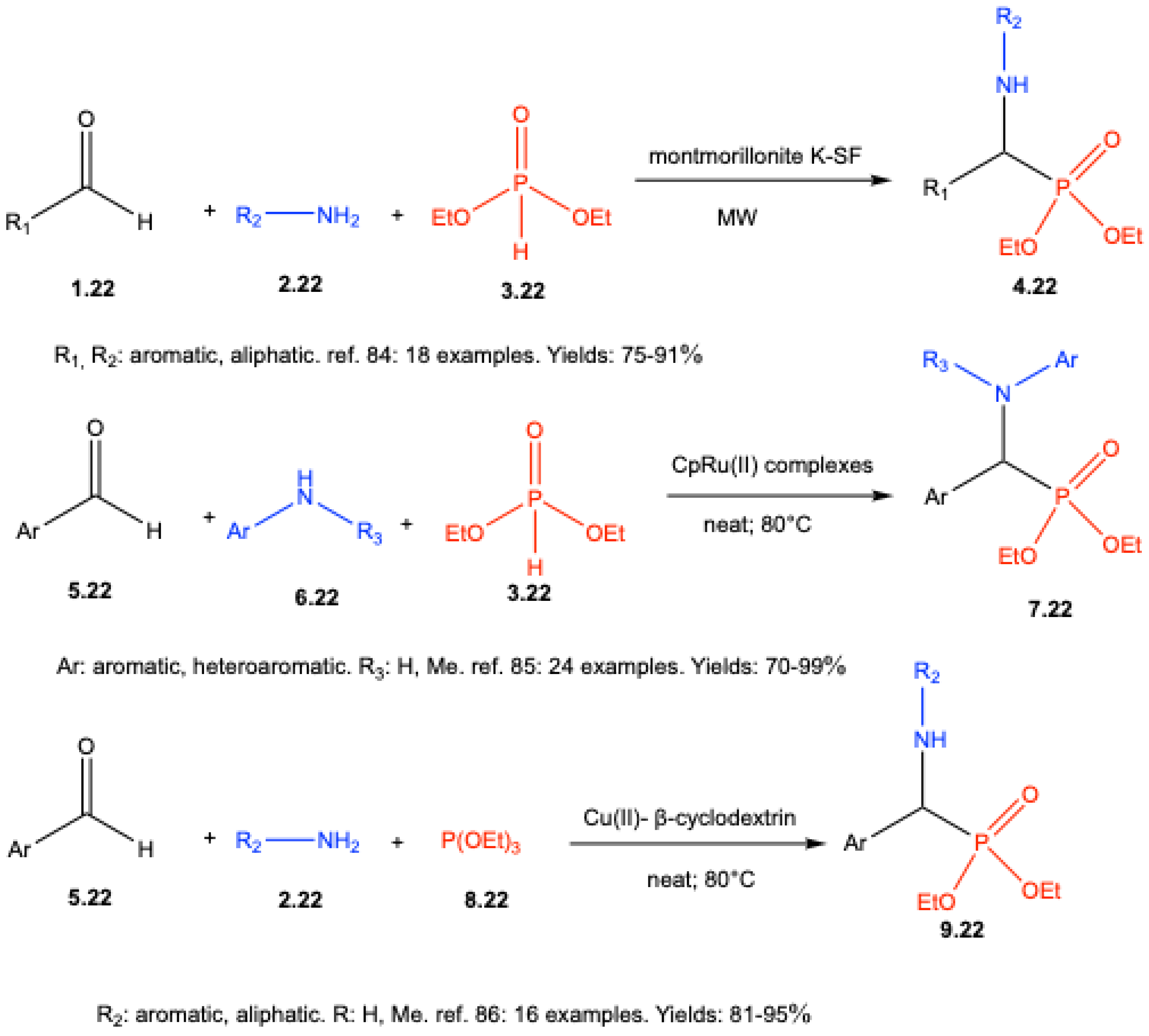

3. Catalyst-Free Kabachnik–Fields Reactions

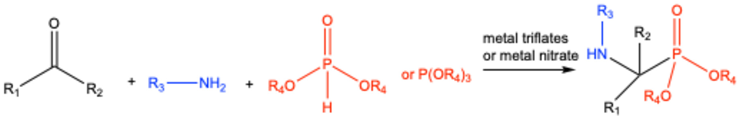

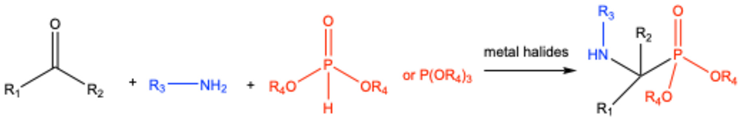

4. Lewis Acid-Catalyzed Kabachnik–Fields Reactions

| ||||||

| Entry |

Aldehydes or Ketones |

Amines | Phosphites | Catalyst | Yields | Ref. |

| 1 | Aromatic | Aniline | Diethyl Triethyl |

Lanthanides triflates | 23 examples: 18-99% |

[78] |

| 2 | Aromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Trimethyl | Cu(OTf)2 | 11 examples: 57-97% |

[79] |

| 3 | Aromatic Aliphatic Cyclohexanone |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Diethyl | In(OTf)3 | 21 examples: 16-99% |

[80] |

| 4 | Aromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic, Aliphatic | Dimethyl Diethyl |

Zn(OTf)2 | 20 examples: 72-93% |

[81] |

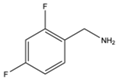

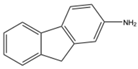

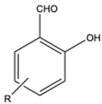

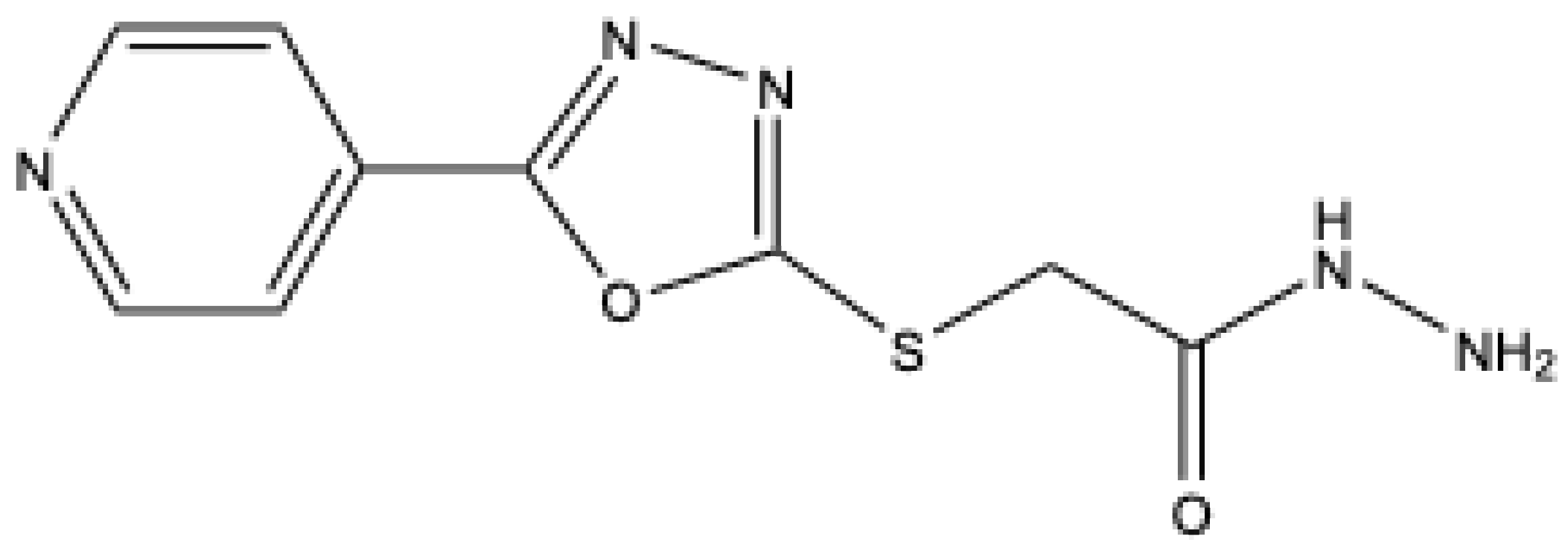

| 5 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic |

Figure 2 | Diethyl | Fe(OTf)3 | 13 examples: 65-73% |

[82] |

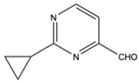

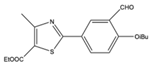

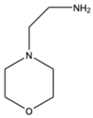

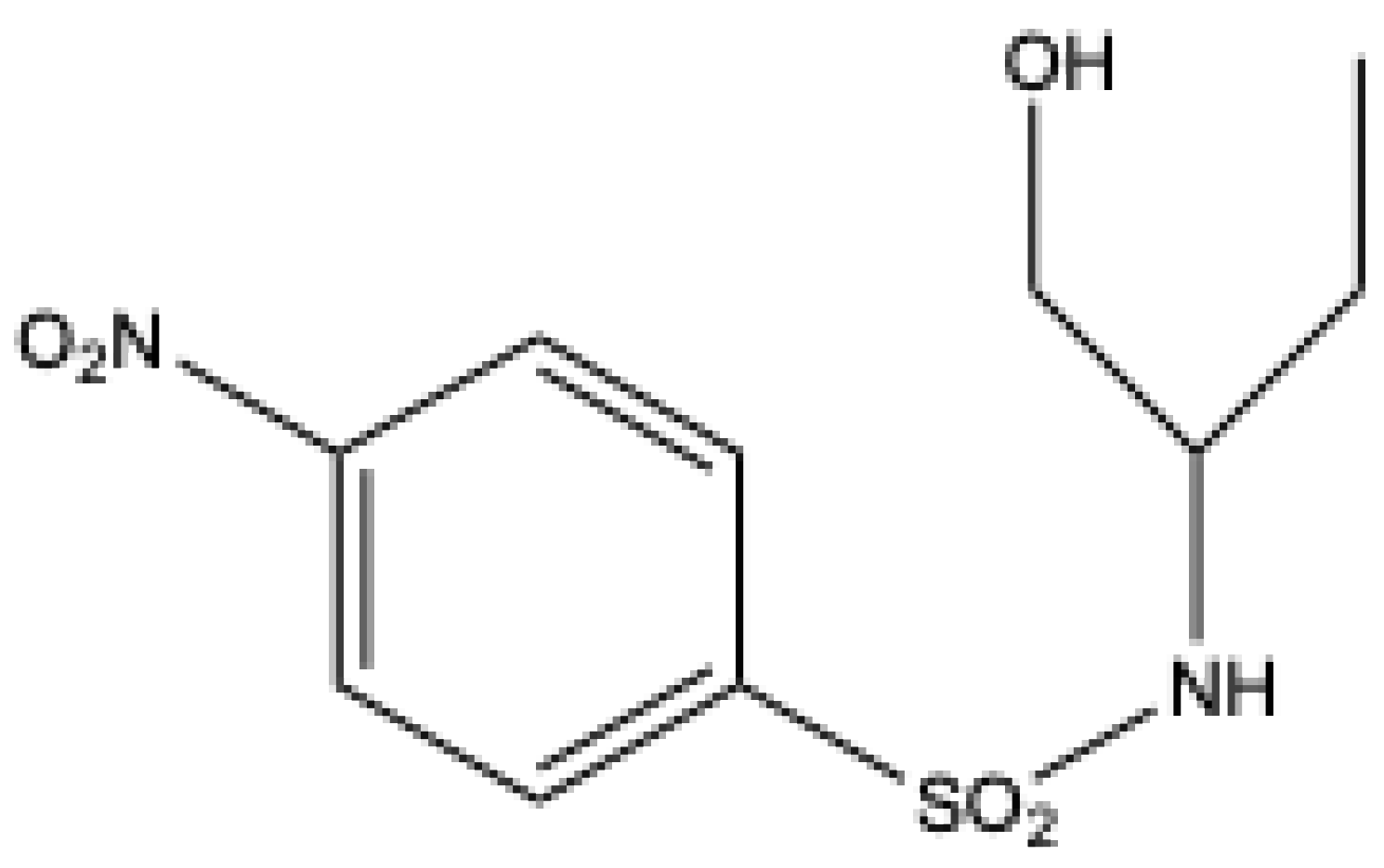

| 6 | Aromatic | Heteroaromatic | Diethyl Diphenyl |

Figure 3 | 18 examples: 86-97% |

[28] |

| 7 | Aromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic | Diethyl | Bi(NO3)3.5H2O | 18 examples: 80-95% |

[83] |

5. Brønsted Acid-Catalyzed Kabachnik–Fields Reactions

| ||||||

| Entry |

Aldehydes or Ketones |

Amines | Phosphites | Catalyst | Yields | Ref. |

| 1 | Aromatic | NH4OH | Diethyl |  |

9 examples: 53-81% |

[87] |

| 2 | HCHO | Aromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

|

8 examples: 51-95% |

[88] |

| 3 | HCHO | 2-Aminopyridine or 2-Phenylethan-1-amine |

Didecyl or Decyl phenyl |

|

2 examples: 94% |

[89] |

| 4 | HCHO | aminoacetaldehyde dimethylacetal | Dihexyl |  |

1 example: 91% |

[90] |

| 5 | HCHO | aminoaaldehyde dimethylacetals | Aliphatic |  |

8 examples: Yields n.a. |

[91] |

| 6 | Salicylaldehydes | Aromatic | Triphenyl |  |

12 examples: 82-94% |

[9] |

| 7 | Aromatic |  |

Diethyl | MeSO3H | 7 examples: 75-92% |

[92] |

| 8 | Aromatic | Aromatic Aliphatic |

Diethyl | Sulfamic acid |

17 examples: 81-100% |

[93] |

| 9 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic |

p-Anisidine | Diethyl | CF3COOH | 9 examples: 87-95% |

[94] |

| 10 | Aromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic | Trimethyl | Me2S+Br Br- | 14 examples: 87-95% |

[95] |

| 11 | Aromatic | Aromatic | Triethyl | Tartaric acid | 12 examples: 65-89% |

[96] |

| 12 | Aromatic Aliphatic Cyclic Ketones Aliphatic Ketones |

Benzylamine | Dimethyl | Phenyl boronic acid |

22 examples: 28-93% |

[97] |

| 13 | Aromatic Aliphatic Aliphatic Ketones |

Benzylamine | Dimethyl | Phenyl phosphonic acid |

20 examples: 47-98% |

[98] |

| 14 | Aromatic | Aromatic | Diethyl | Citric acid Malic acid Tartaric acid Oxalic acid |

84 examples: 54-95% |

[99] |

| 15 |  |

Aromatic Heteroaromatic |

Aliphatic Diphenyl |

H₃PMo₁₂O₄₀ | 14 examples: 89-96% |

[100] |

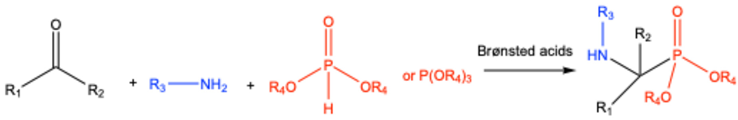

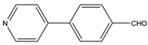

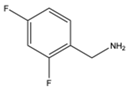

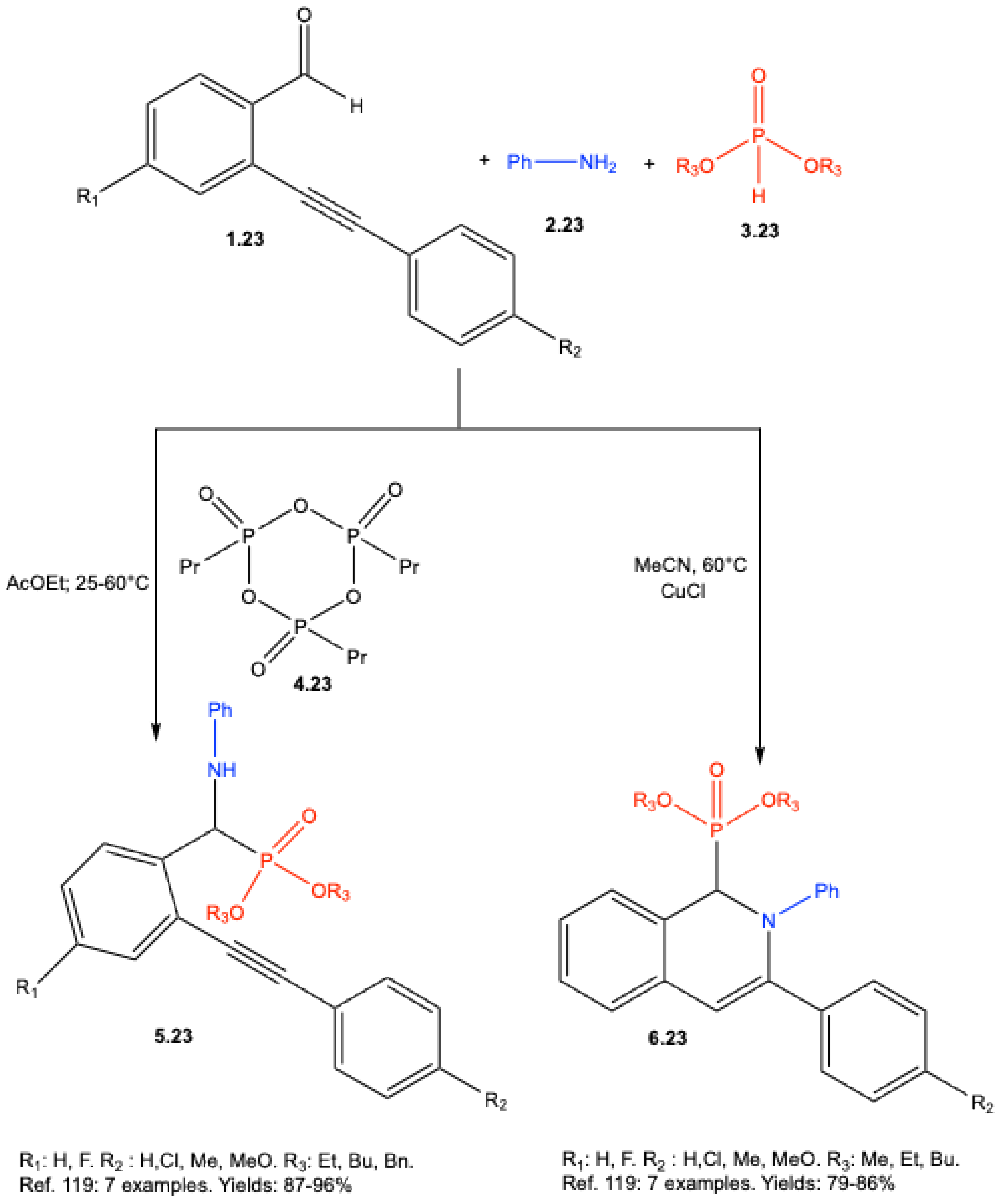

| 16 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic | Diethyl | Figure 4 | 26 examples: 87-96% |

[101] |

| ||||||

| Entry |

Aldehydes or Ketones |

Amines | Phosphites | Catalyst | Yields | Ref. |

| 1 | Aromatic | Aromatic | Diethyl | Sulfated polyborate | 20 examples: 90-98% |

[102] |

| 2 | Aromatic | Aniline | Dimethyl Diethyl |

Silica sulfuric acid | 11 examples: 80-95% |

[103] |

| 3 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic |

Aromatic | Diethyl | Xanthan sulfuric acid |

32 examples: 88-95% |

[104] |

| 4 | Aromatic Aliphatic Cyclohexanone |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Triethyl | Phosphoric acid on γ-Fe2O3@SiO2 |

16 example: 82-95% |

[105] |

| 5 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic Cyclohexanone |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Methyl | DHAA-Fe3O4 | 10 examples: 75-95% |

[106] |

| 6 | Aromatic Aliphatic |

|

Diethyl | polystyrene-supported

|

18 examples: Yields: n.a |

[107] |

| 7 |  |

Aromatic | Diethyl | β-cyclodextrin-supported sulfonic acid | 10 examples: 91-96% |

[108] |

| 8 |  |

Aromatic Heteroaromatic |

Triethyl | polyethylene glycol sulfonic acid | 10 examples: 82-96% |

[109] |

| 9 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic Acetophenone |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Dialkyl | H-beta zeolite | 15 examples: 76-93% |

[110] |

| 10 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Diethyl | Humic acid | 25 examples: 78-93% |

[111] |

| 11 |  |

Aromatic | Triethyl | N-TiO2 | 11 examples: 71-95% |

[112] |

| 12 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic Cyclohexanone Acetophenone |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Diethyl | TiO2 | 36 examples: 50-98% |

[113] |

6. Other Catalysts for Kabachnik–Fields Reactions

| ||||||

| Entry | Aldehydes | Amines | Phosphites | Catalyst | Yields | Ref. |

| 1 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic |

Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic |

Diethyl | Nano CeO2 | 16 examples: 67-99% |

[114] |

| 2 |  |

|

Dimethyl | Nano Gd2O3 | 10 examples: Yields: n.a |

[115] |

| 3 | Aromatic | 2-aminophenol | Dimethyl | Nano CuO-Au | 10 examples: 87-96% |

[116] |

| 4 | Aromatic |  |

Diethyl | TiO2-ZnO | 12 examples: 91-95% |

[117] |

| 5 | Aromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic Heteroaromatic |

Diethyl | Nb2O5 | 43 examples: 40-97% |

[118] |

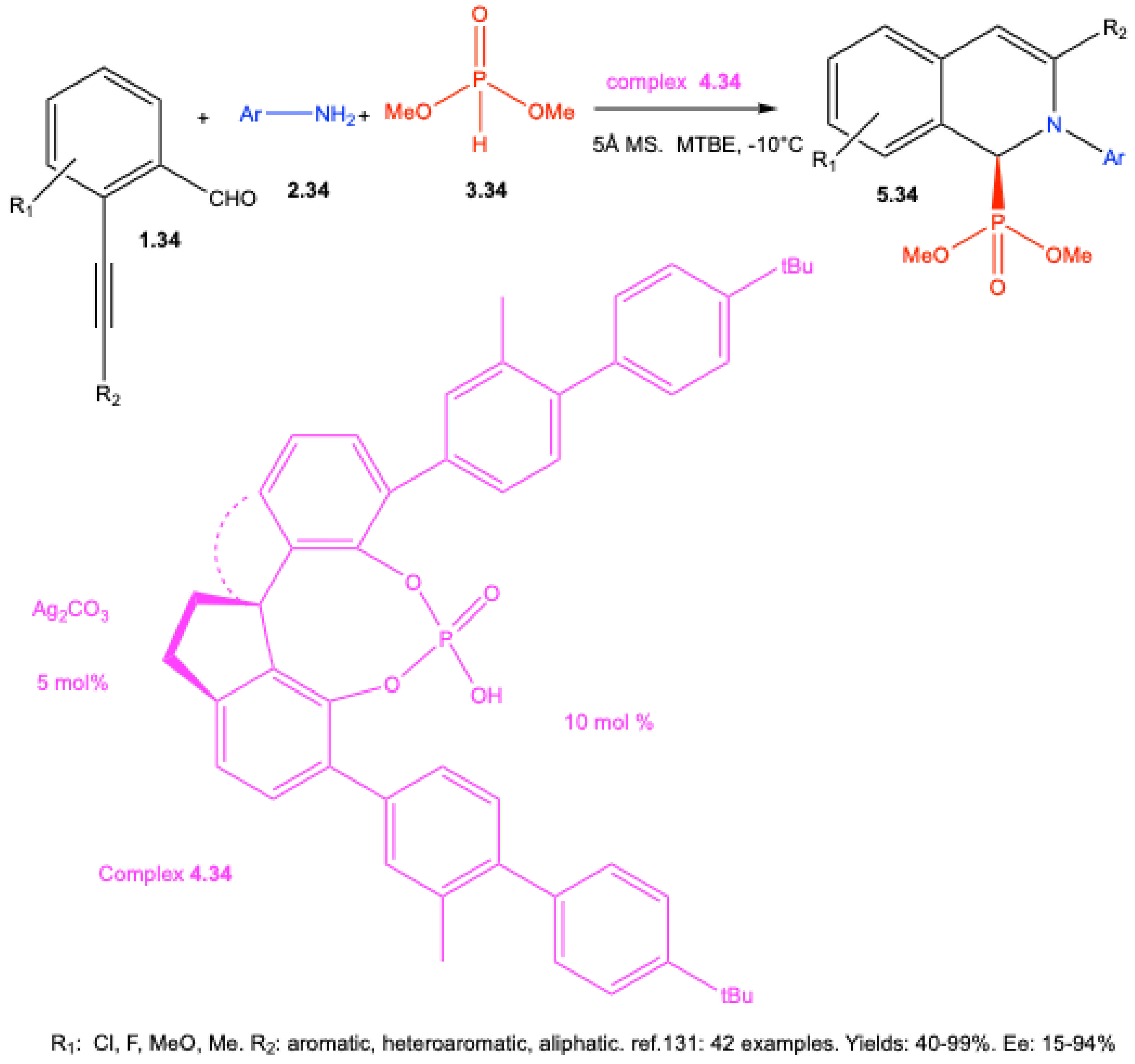

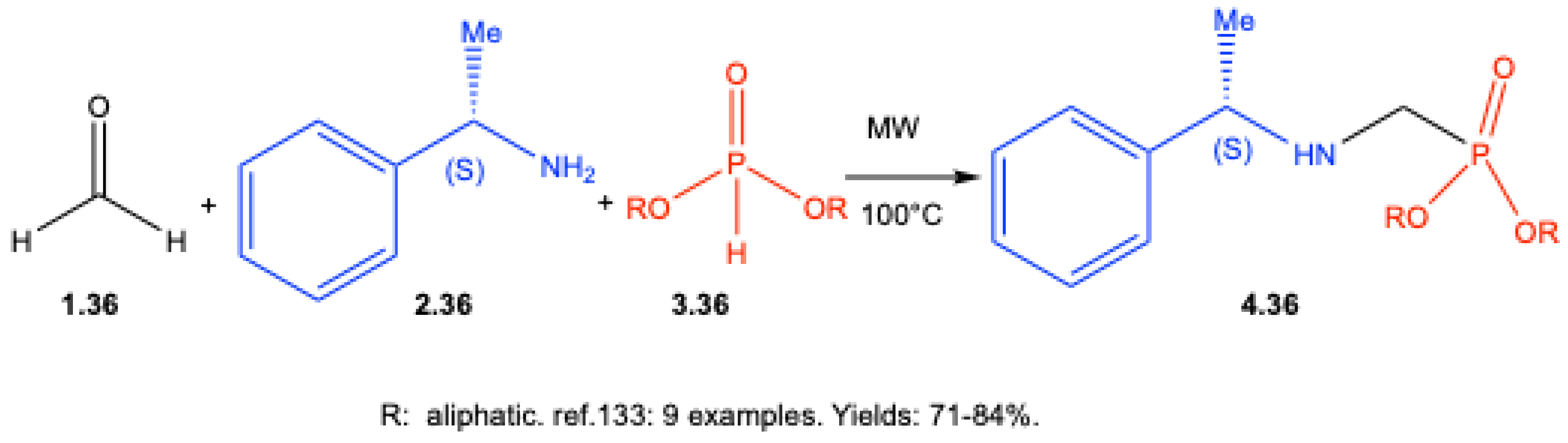

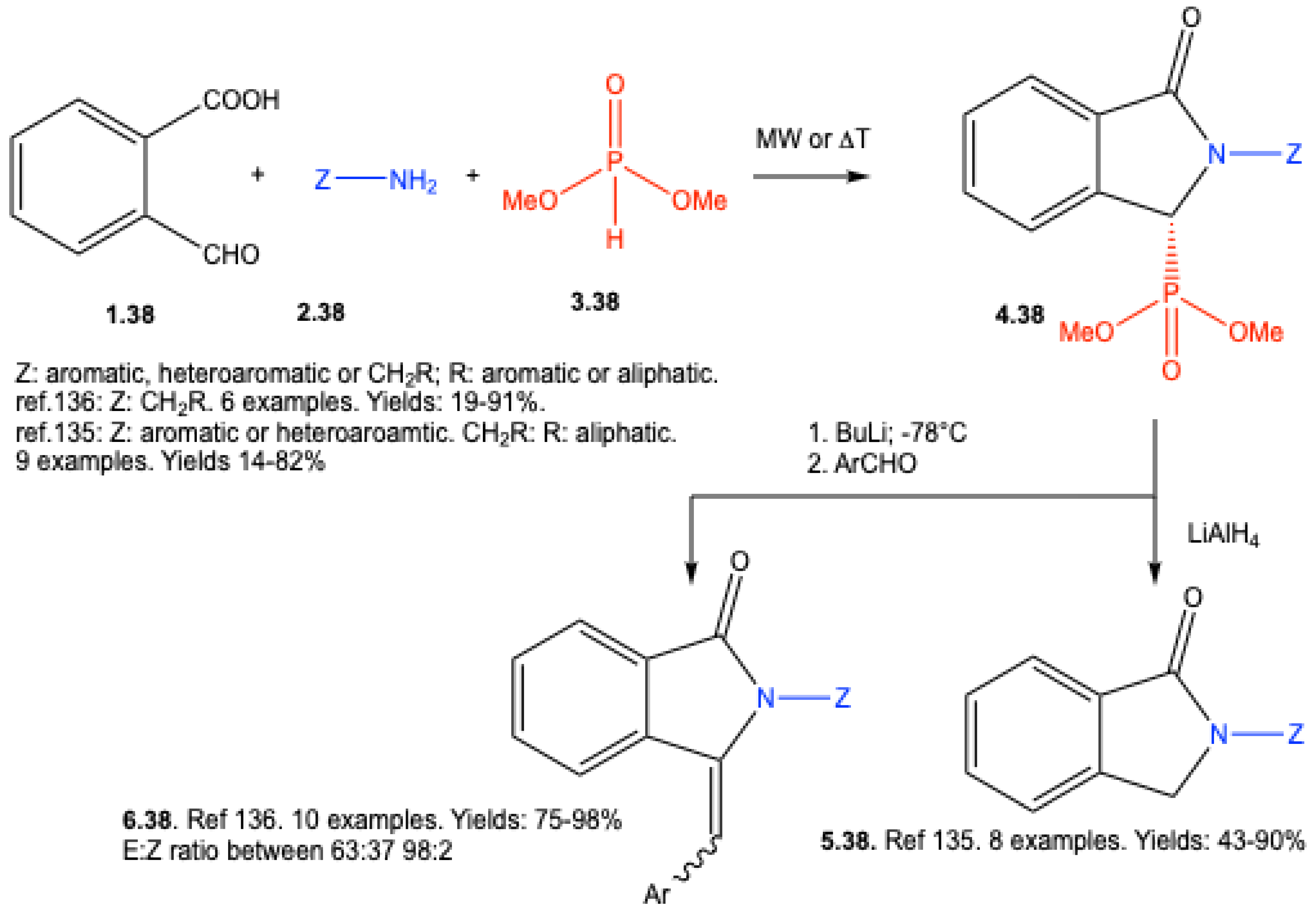

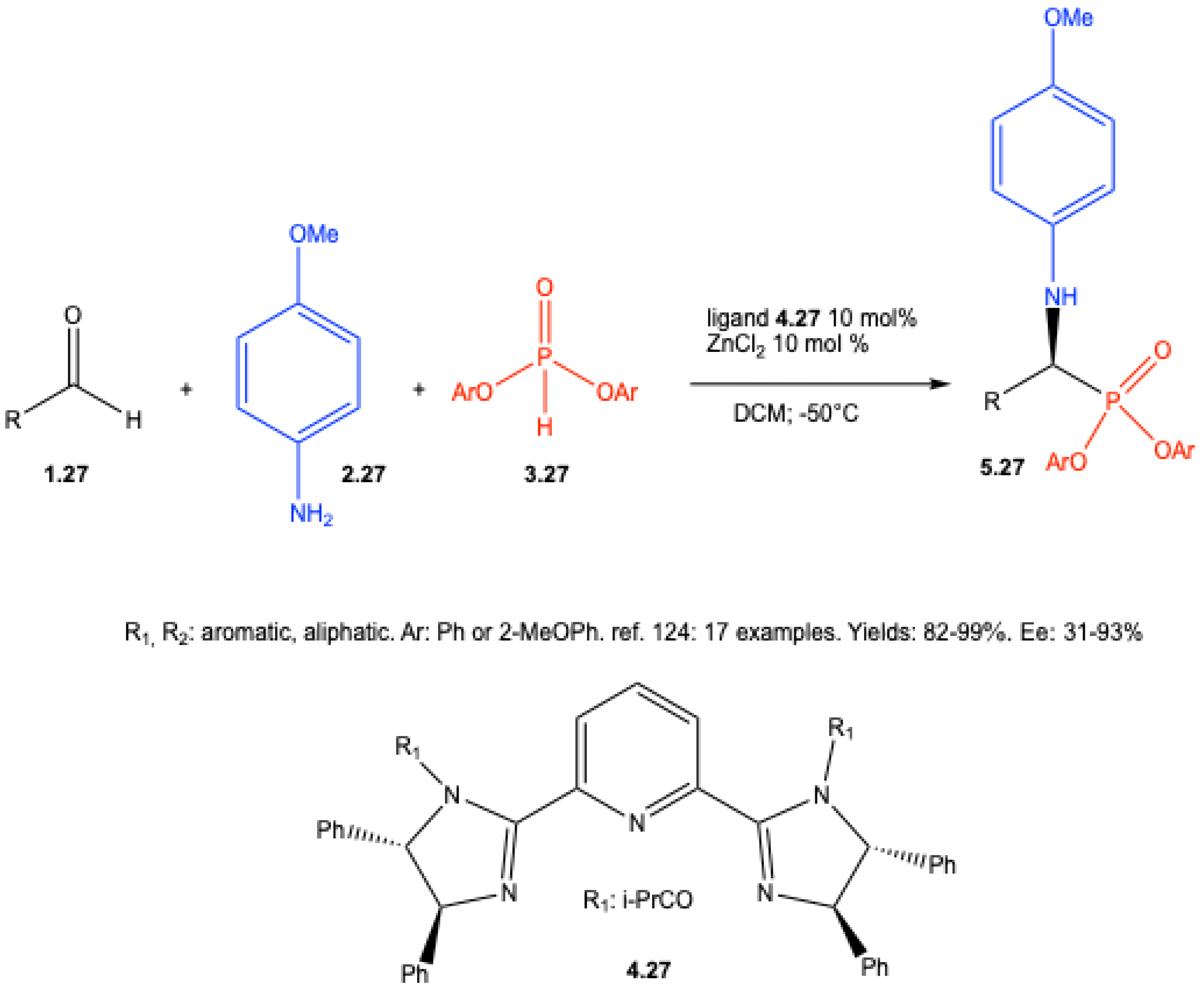

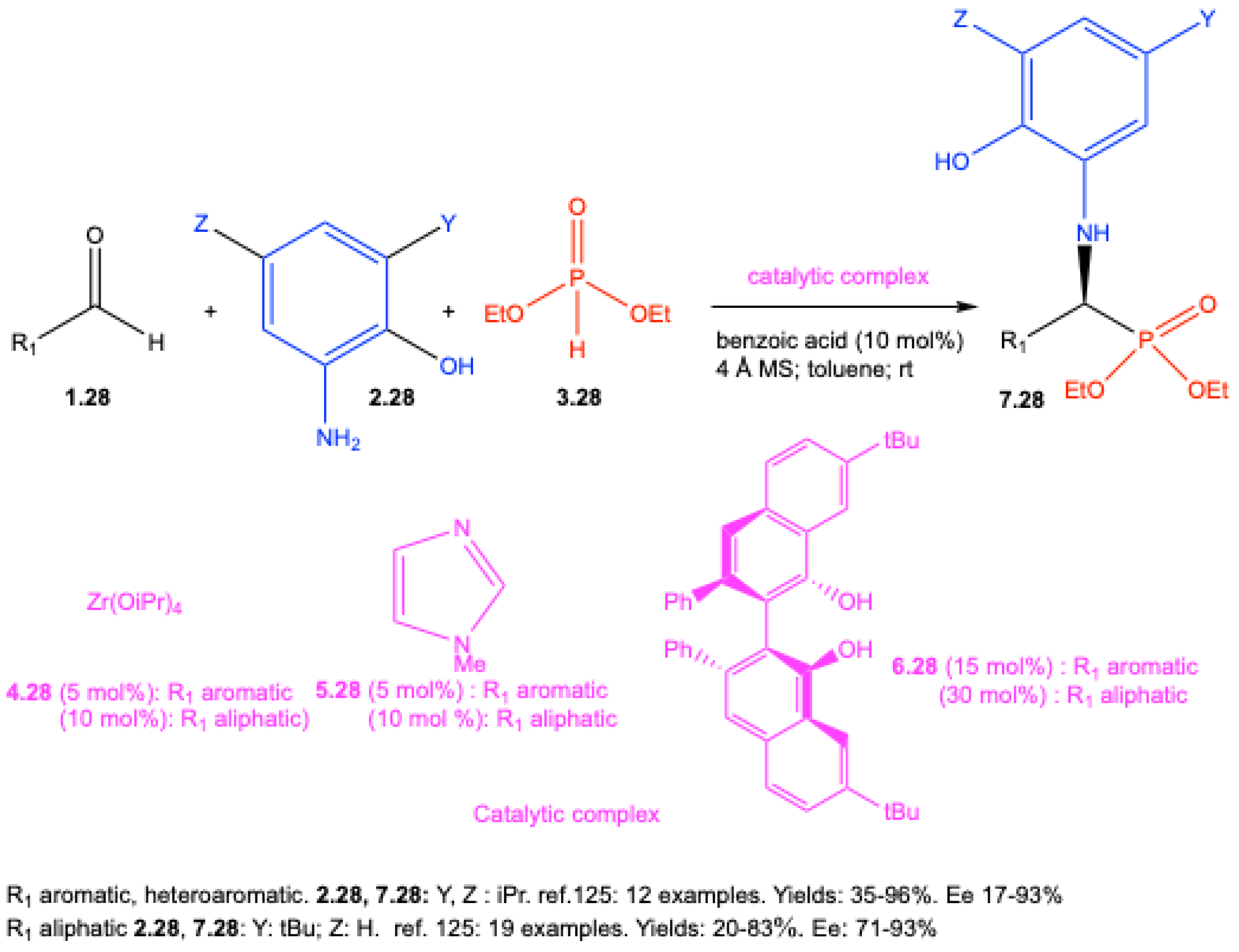

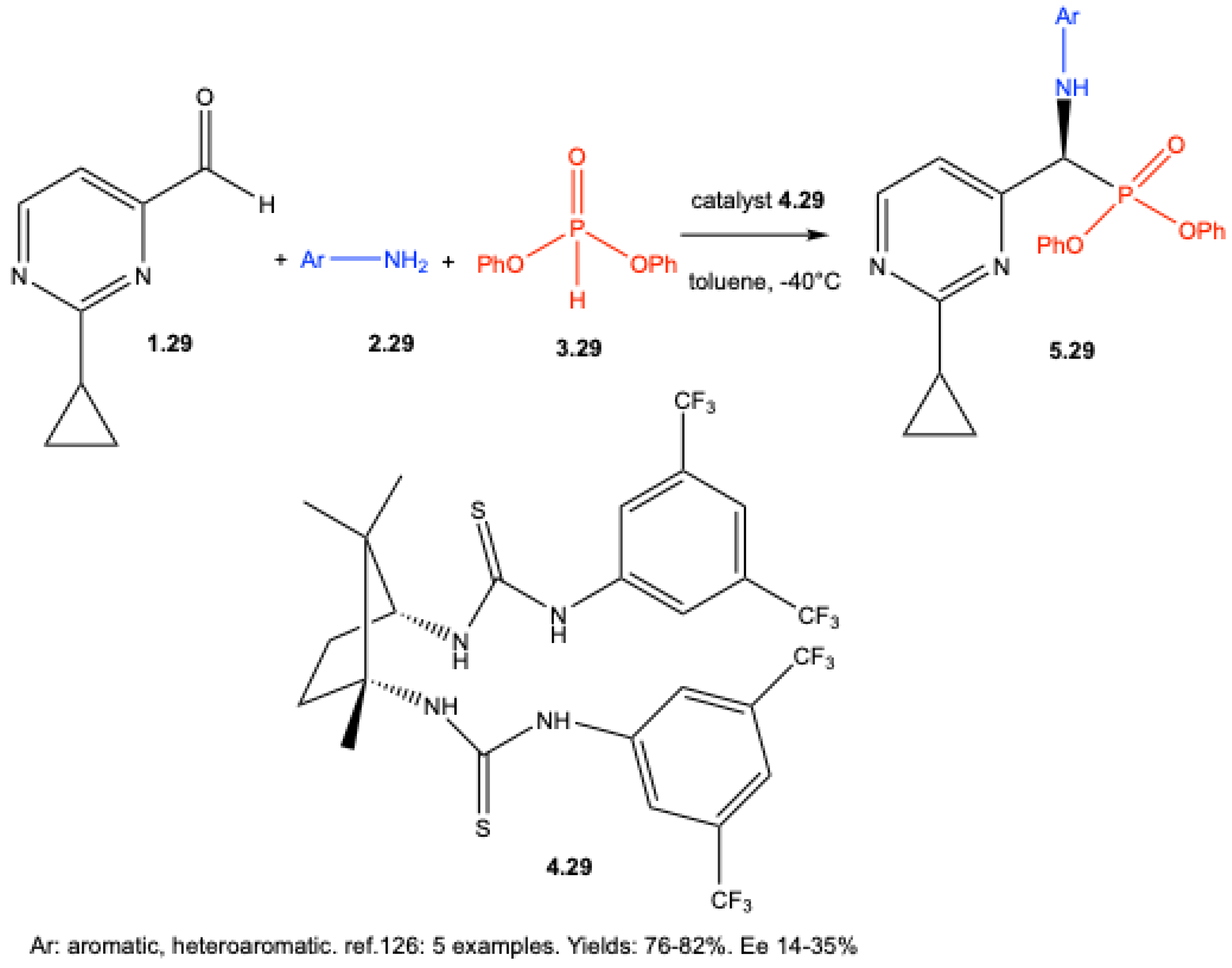

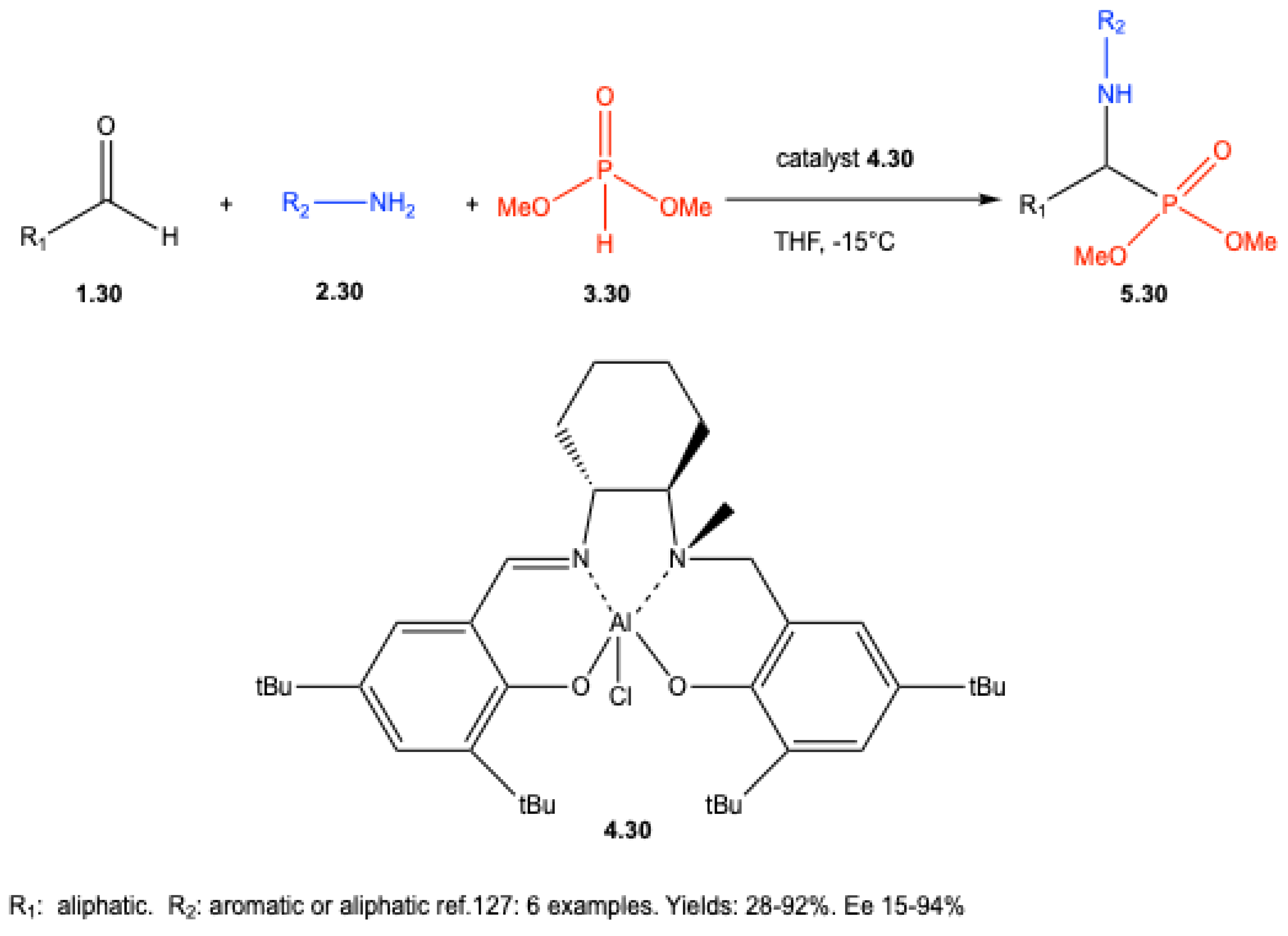

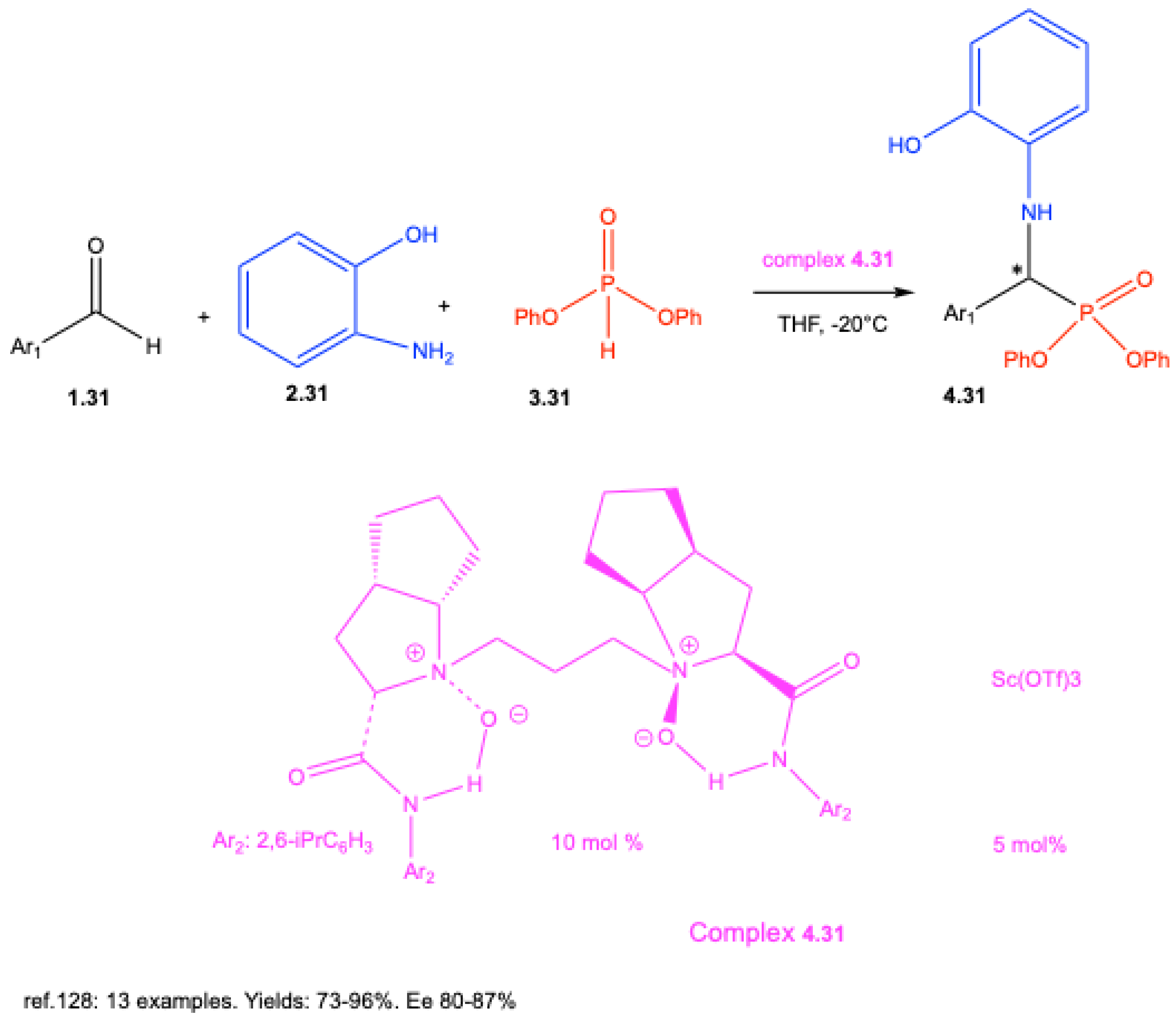

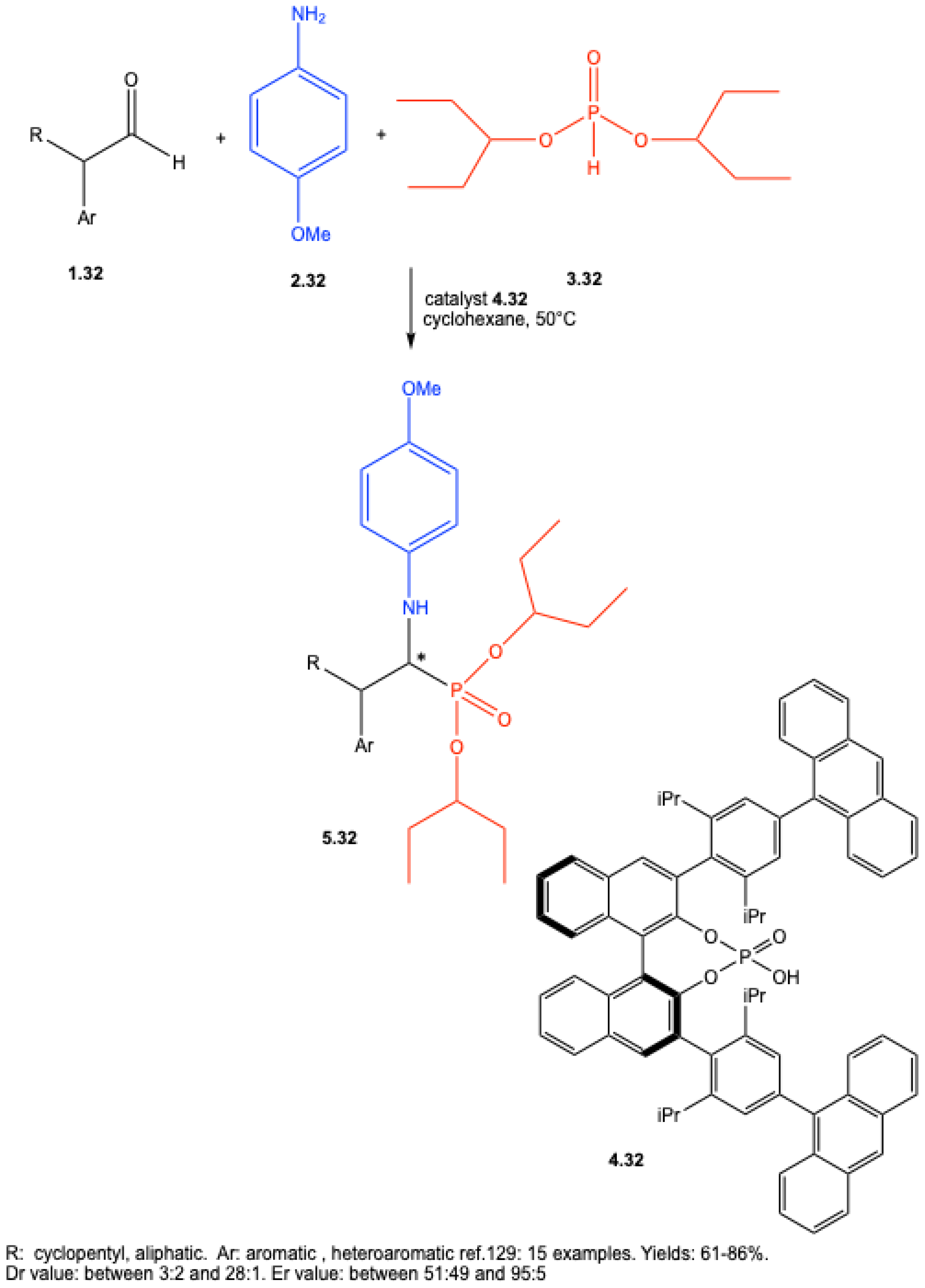

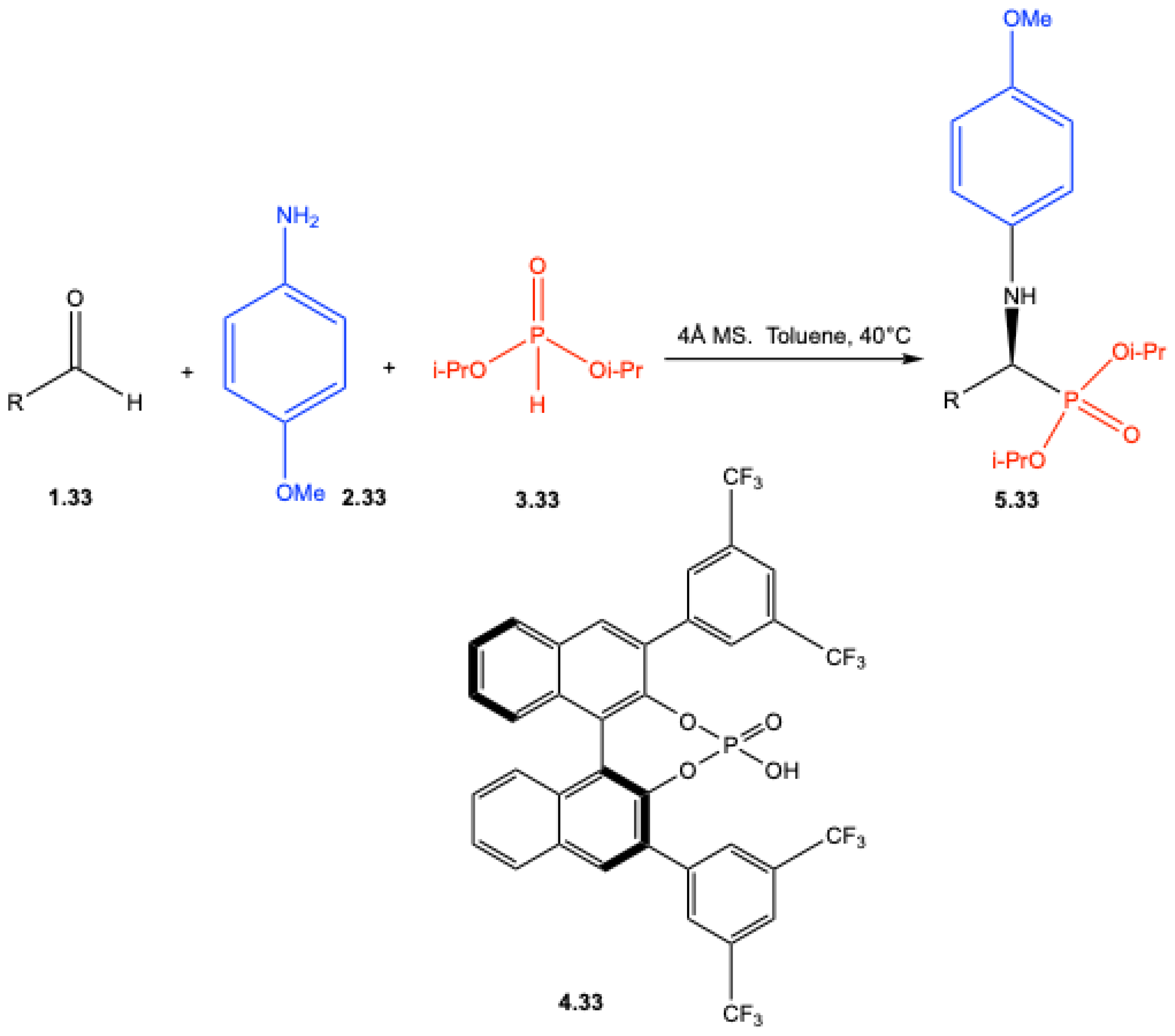

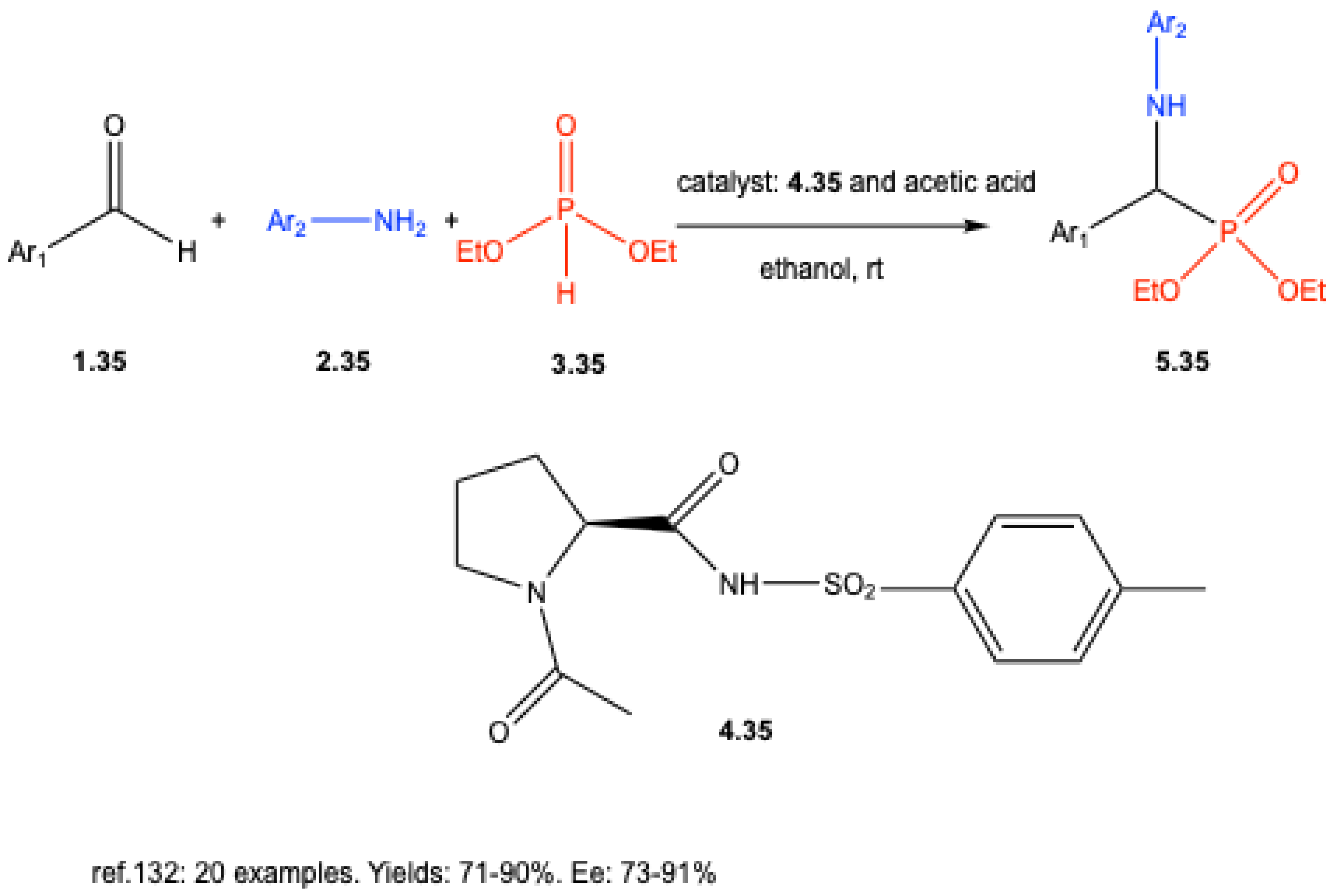

7. Enantioselective Kabachnik–Fields Reactions

7.1. Lewis Acid–Catalyzed Reactions

7.2. Brønsted Acid–Catalyzed Reactions

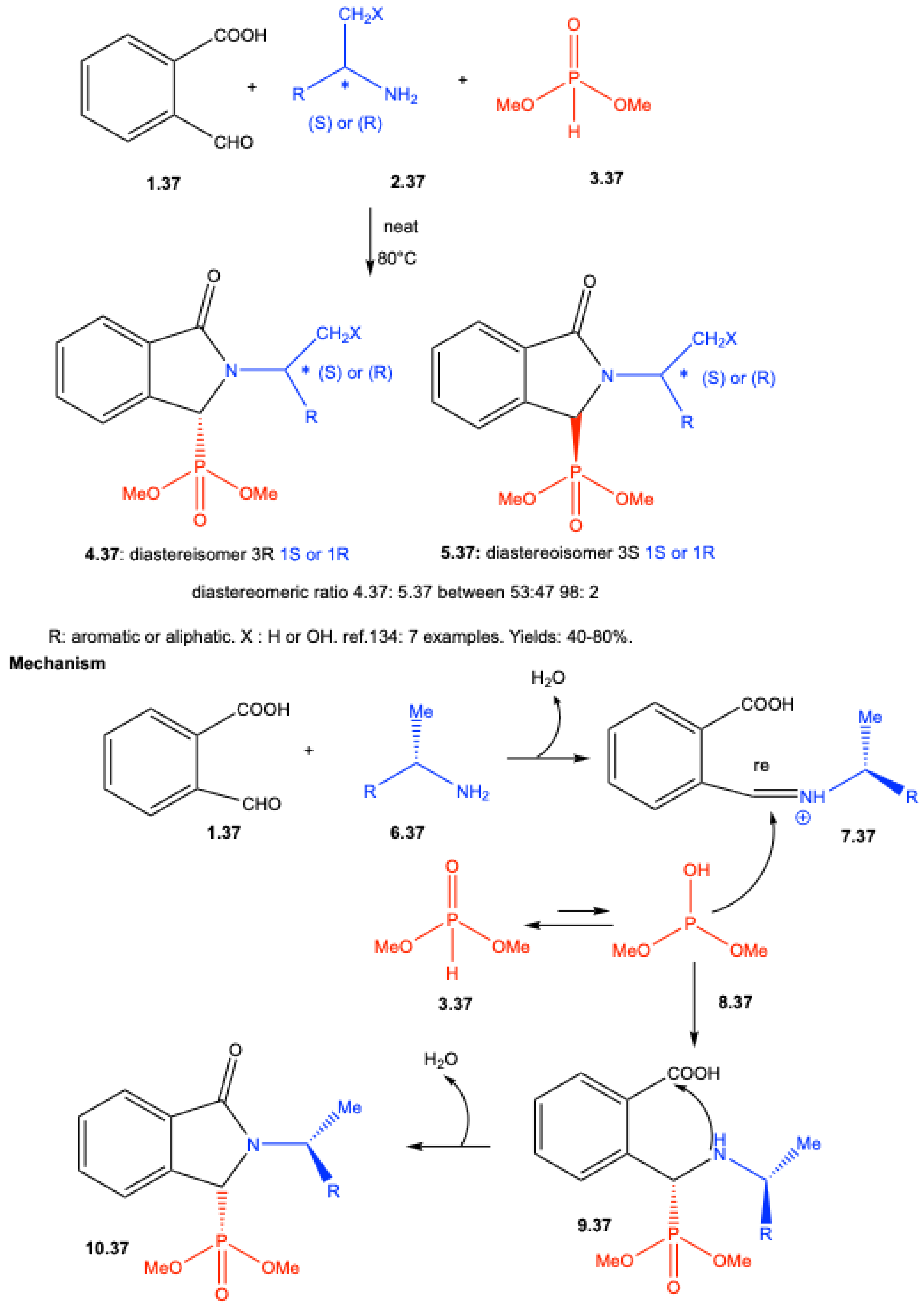

7.3. Enantioselective Synthesis Without Chiral Catalysts

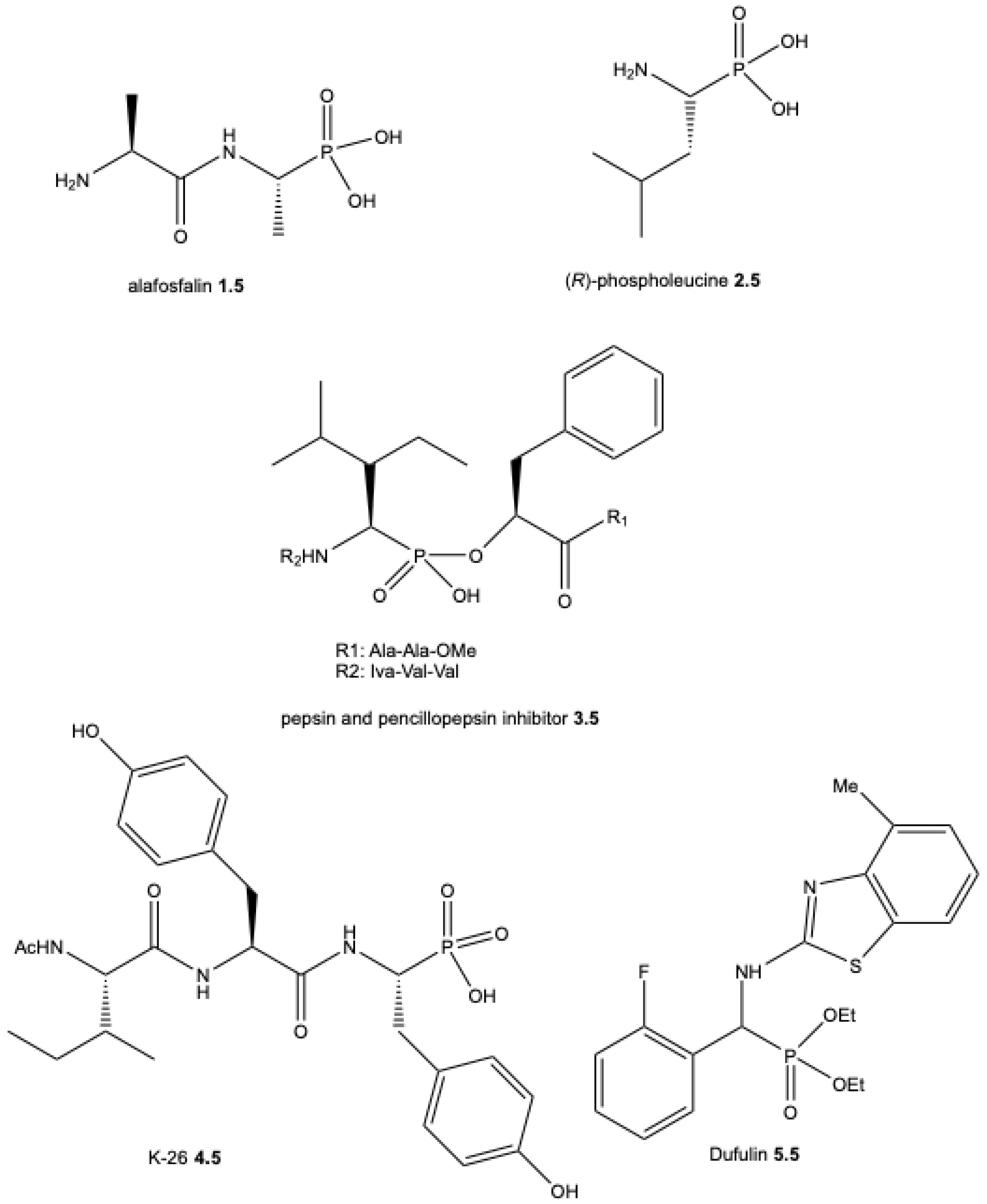

8. Derivatives of α-Aminophosphonates

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kabachnik, M. I.; Medved, T. Y. New synthesis of aminophosphonic acids. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1952, 83, 689–692. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fields, E.K., The synthesis of esters of substituted amino phosphonic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1952, 74, 1528–1531. [CrossRef]

- Zefirov, N. S.; Matveeva, E. D. Catalytic Kabachnik-Fields reaction: new horizons for old reaction. Arkivoc 2008, (i), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keglevich, G.; Bálint, E. The Kabachnik–Fields Reaction: Mechanism and Synthetic Use. Molecules 2012, 17, 12821–12835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, P.; Keglevich, G. Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates and Related Derivatives; The Last Decade of the Kabachnik–Fields Reaction. Molecules 2021, 26, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, R.; He, X.; Zhu, C.; Tao, L. Recent Developments in Functional Polymers via the Kabachnik–Fields Reaction: The State of the Art. Molecules 2024, 29, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasov, R. A; Galkin, V. I. The Kabachnik-Fields reaction: synthetic potential and the problem of the mechanism. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1998, 67, 857–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gábor, D.; Pollák, P.; Volk, B.; Dancsó, A.; Simig, G.; Milen, M. Catalyst- and Solvent-Free Room Temperature Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates: Green Accomplishment of the Kabachnik–Fields Reaction. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202301460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Liu, R.; Wan, D. Convenient One-Pot Synthesis of α-Amino Phosphonates in Water Using p-Toluenesulfonic Acid as Catalyst for the Kabachnik–Fields Reaction. Heteroat. Chem. 2013, 24, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, E.; Tripolszky, A.; Jablonkai, E.; Karaghiosoff, K.; Czugler, M.; Mucsi, Z.; Kollár, L.; Pongrácz, P.; Keglevich, G. Synthesis and use of α-aminophosphine oxides and N,N-bis(phosphinoylmethyl)amines—A study on the related ring platinum complexes. J. Organomet. Chem. 2016, 801, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pudovik, A. N. Addition of dialkyl phosphites to imines. New method of synthesis of esters of amino phosphonic acids. Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 1952, 83, 865–868, [Chem. Abstr. 1953, 47, 4300.]. [Google Scholar]

- Galkin, V. I.; Zvereva, E. R.; Sobanov, A. A.; Galkina, I. V.; Cherkasov, R. A. A study on the Kabachnik-Fields reaction of benzaldehyde, cyclohexylamine and dialkyl phosphites. Zh Obshch. Khim 1993, 63, 2225–2227. [Google Scholar]

- Dimukhametov, M. N.; Bayandina, E. V.; Davydova, E. Y.; Gubaidullin, A. T.; Litvinov, I. A.; Alfonsov, V. A. Mendel. Comm. 2003, 3, 150–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, E. D.; Zefirov, N. S. On the Mechanism of the Kabachnik–Fields Reaction: Does a Mechanism of Nucleophilic Amination of α-Hydroxyphosphonates Exist? Dokl. Chem. 2008, 420, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keglevich, G.; Kiss, N. Z.; Menyhard, D. K.; Fehervari, A.; Csontos, I. A Study on the Kabachnik–Fields Reaction of Benzaldehyde, Cyclohexylamine, and Dialkyl Phosphites. Heteroat. Chem. 2012, 23, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keglevich, G.; Fehervari, A.; Csontos, I. A Study on the Kabachnik–Fields Reaction of Benzaldehyde, Propylamine, and Diethyl Phosphite by In Situ Fourier Transform IR Spectroscopy. Heteroat. Chem. 2011, 22, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, X.; Chen, Z.; Xu, Y.; Lv, K.; Zhang, I.; Liu, T. Molecular synthesis mechanism of α-aminophosphonate using DES: Ring-tension-controlled reactivity. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2025, 578, 122549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, R. Phosphorus Addition at sp² Carbon. Org. React. 2004, 175–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabachnik, M. I.; Medved, T. Y. New method for the synthesis of 1-aminoalkylphosphonic acids Communication 1. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2 1953, 769–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galkina, I. V.; Sobanov, A. A.; Galkin, V. I.; Cherkasov, R. A. Kinetics and mechanism of the Kabachnik–Fields reaction: IV. Salicyaldehyde in the Kabachnik–Fields reaction. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 1998, 68, 1398–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Gancarz, R.; Gancarz, I. Failure of Aminophosphonate Synthesis Due to Facile Hydroxyphosphonate–Phosphate Rearrangement. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993, 34, 145–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancarz, R.; Gancarz, I.; Walkowjak, U. On the reversibility of hydroxyphosphonate formation in the in the Kabachnik-Fields reaction. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 1995, 104, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancarz, R. Unexpeced products in the Kabachnik-Fields synthesis of aminophosphonates. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 1993, 83, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gancarz, R. Nucleophilic Addition to Carbonyl Compounds. Competition between Hard (Amine) and Soft (Phosphite) Nucleophile. Tetrahedron 1995, 51, 10627–10632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S.; Chakraborti, A. K. An Extremely Efficient Three-Component Reaction of Aldehydes/Ketones, Amines, and Phosphites (Kabachnik-Fields Reaction) for the Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates Catalyzed by Magnesium Perchlorate. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 1263–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

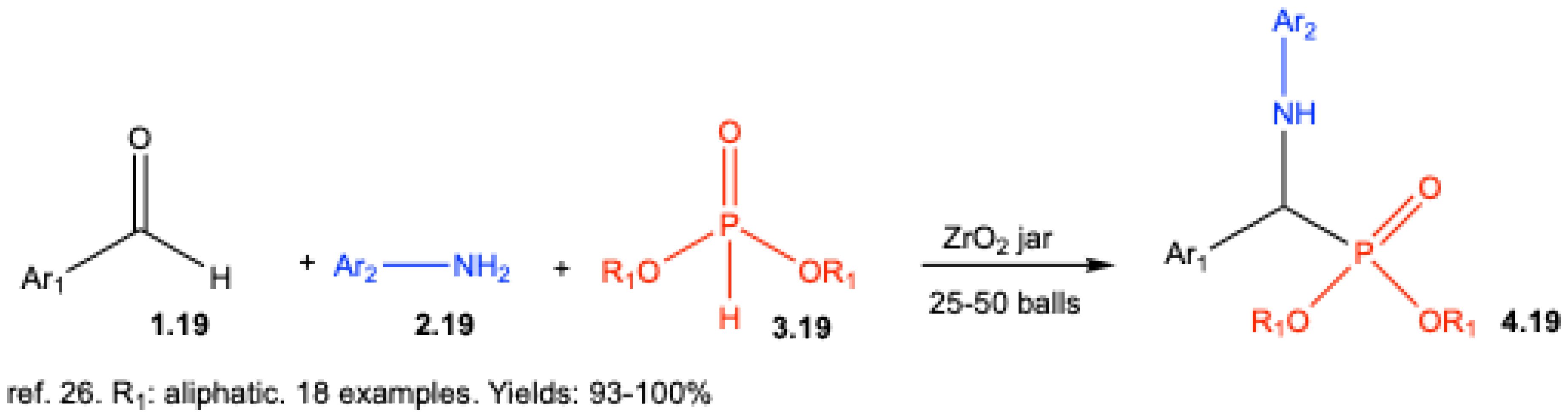

- Fiore, C.; Sovic, I.; Lukin, S.; Halasz, I.; Martina, K.; Delogu, F.; Ricci, P. C.; Porcheddu, A.; Shemchuk, O.; Braga, D.; Pirat, J.-L.; Virieux, D.; Colacino, E. Kabachnik−Fields Reaction by Mechanochemistry: New Horizons from Old Methods. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 18889−18902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milen, M.; Ábrányi-Balogh, P.; Dancsó, A.; Frigyes, D.; Pongó, L.; Keglevich, G. T3P®-promoted Kabachnik–Fields reaction: An efficient synthesis of α-aminophosphonates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 5430–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

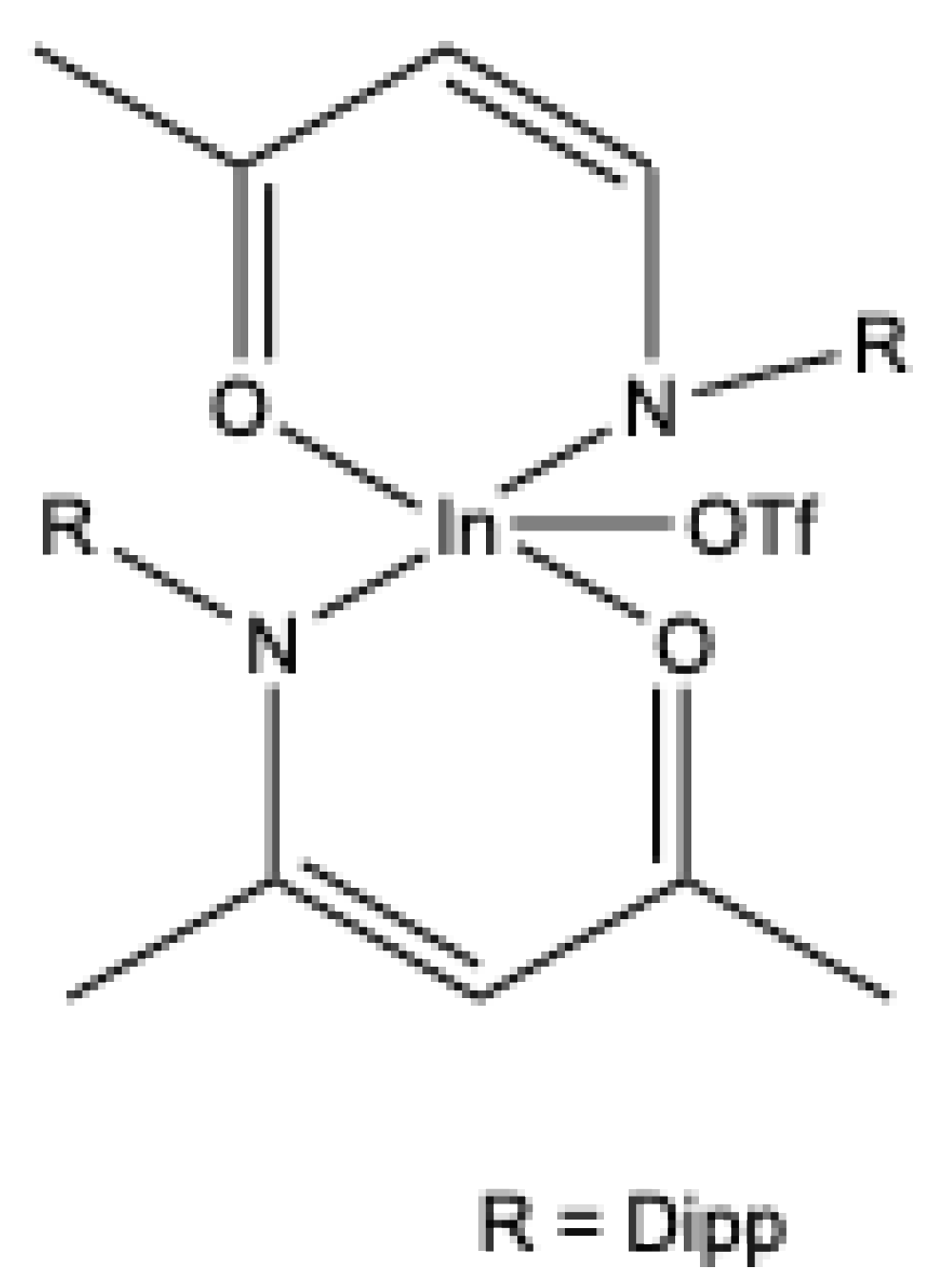

- Das, S.; Rawal, P.; Bhattacharjee, J.; Devadkar, A.; Pal, K.; Gupta, P.; Panda, T. K. Indium promoted C(sp3)–P bond formation by the Domino A3-coupling method – a combined experimental and computational study. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 1142–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V. K.; Tiwari, C. S.; Rit, A. Silver-Catalyzed One-Pot Three-Component Synthesis of α- Aminonitriles and Biologically Relevant α-Amino-phosphonates. Chem. Asian J. 2022, 17, e202200703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboudin, B.; Faghih, S.; Alavi, S.; Naimi-Jamal, M. R.; Fattahi, A. An Efficient One-Pot Synthesis of 1-Aminophosphonates. Synthesis 2023, 55, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranu, B. C.; Hajra, A. A simple and green procedure for the synthesis of a-aminophosphonate by a one-pot three-component condensation of carbonyl compound, amine and diethyl phosphite without solvent and catalyst. Green Chem. 2002, 4, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, Z.; Naeimi, H.; Ghahremanzadeh, R. Highly efficient one-pot four-component Kabachnik–Fields synthesis of novel α-amino phosphonates under solvent-free and catalyst-free conditions. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 99148–99152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, J.; Lu, H. A novel route for the synthesis of phosphonate-containing siloxanes by the catalyst-free Kabachnik—Fields reaction. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2024, 73, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliya, S.; Kuperkar, K.; Ashalu, K. C.; Naveen, T. Catalyst-Free Three-Component Synthesis of α-Amino Phosphonates. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2024, 13, e202300572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, Y.; Gong, Z.; Tang, P.; Tang, W. One-pot synthesis and fluorescent property of novel syringaldehyde α-aminophosphonate derivatives. Phosphorus, Sulfur Silicon Relat.Elem 2023, 198, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampath, C.; Harika, P.; Revaprasadu, N. Design, green synthesis, anti-microbial, and anti-oxidant activities of novel α- aminophosphonates via Kabachnik-Fields reaction. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2016, 191, 1081–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.A.; Lee, K.D. A Simple and Catalyst-Free One-Pot Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates in Polyethylene Glycol. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2012, 187, 899–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, K.; Karimi, M.; Heydari, A. A catalyst-free synthesis of α-aminophosphonates in glycerol. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 7236–7239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, S.; Narvariya, R.; Sunar, S. L.; Paul, I.; Jain, A.; Panda, T. K. Synthesis of α-aminophosphorous derivatives using a deep eutectic solvent (DES) in a dual role. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 8266–8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaibuna, S.; Sreekumar, K. Experimental Investigation on the Correlation between the Physicochemical Properties and Catalytic Activity of Six DESs in the Kabachnik-Fields Reaction. ChemistrySelect 2020, 5, 13454–13460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghayegh, M. S.; Azizi, N.; Shahabi, S. S.; Gu, Y. Pvp-based deep eutectic solvent polymer: Sustainable Brønsted-Lewis acidic catalyst in the synthesis of α-aminophosphonate and bisindole. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 387, 122677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaim, A. Y.; Cheraiet, Z.; Guezane-Lakoud, S.; Zadem, A.; Boukhari, A. Natural deep eutectic solvents [BetaineCl][Lactic acid] as efficient and sustainable catalyst for one-pot synthesis of α-aminophosphonates. J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2025, 102, 101593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyckens, D.J.; Henderson, L.C. Synthesis of α-aminophosphonates using solvate ionic liquids. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 27900–27904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, N.; Yang, J.; Ni, C. Dicationicionic liquids as recyclable catalysts for one-pot solvent-free synthesis of α-aminophosphonates. Heteroat. Chem. 2010, 22, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

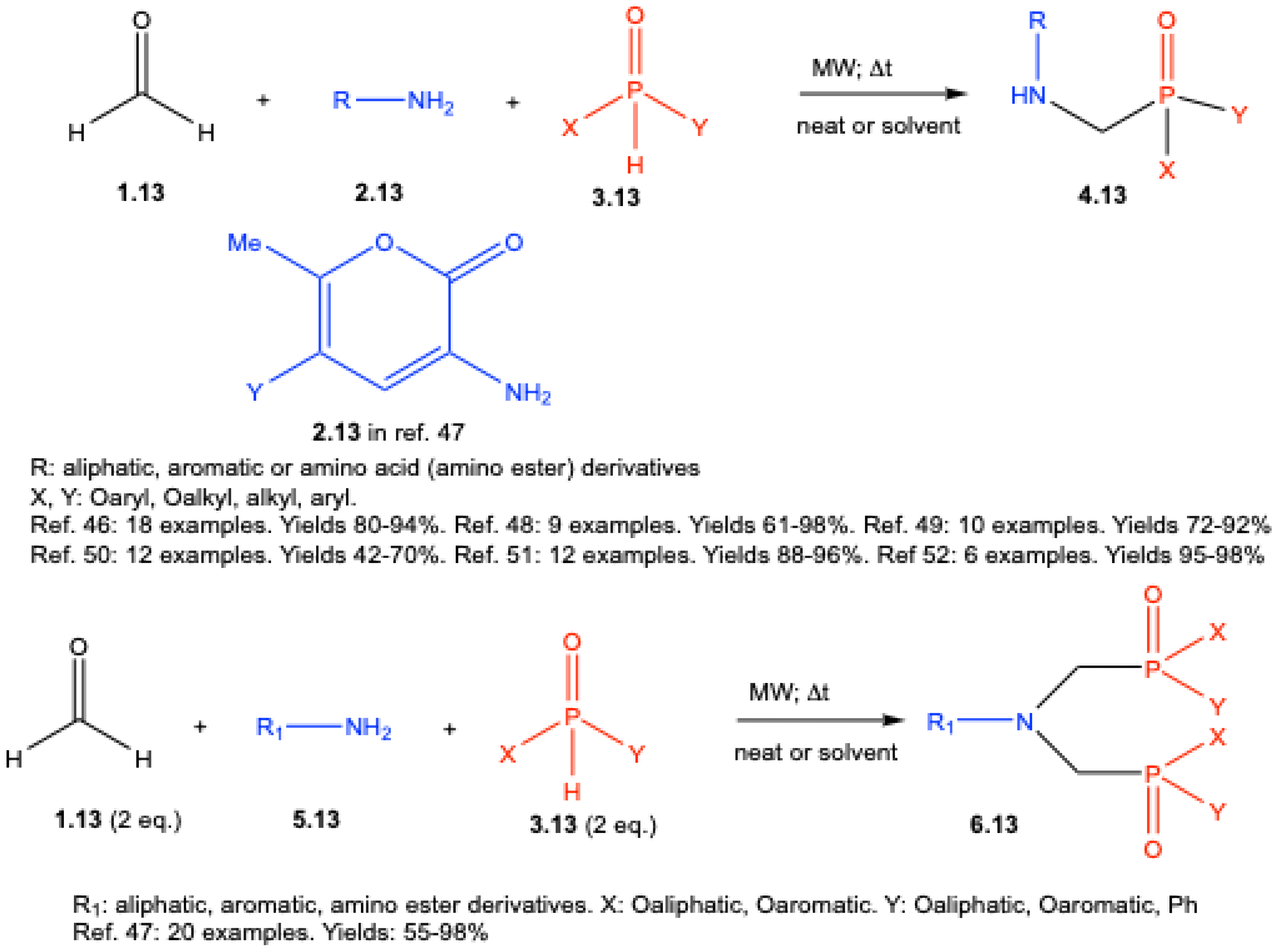

- Keglevich, G.; Szekrenyi, A. Eco-Friendly Accomplishment of the Extended Kabachnik–Fields Reaction; a Solvent- and Catalyst-Free Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates and α-Aminophosphine Oxides. Lett. Org. Chem. 2008, 5, 616–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keglevich, G.; Szekrényi, A.; Kovács, R.; Grün, A. Microwave Irradiation as a Useful Tool in Organophosphorus Syntheses. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2009, 184, 1648–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, E.; Takács, J.; Drahos, L.; Juranovic, A.; Kocevar, M.; Keglevich, G. α-Aminophosphonates and α-Aminophosphine Oxides by the Microwave-Assisted Kabachnik-Fields Reactions of 3-Amino-6-methyl-2H-pyran-2-ones. Heteroat. Chem. 2013, 24, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, E.; Fazekas, E.; Tripolszky, A.; Kangyal, R.; Milen, M.; Keglevich, G. Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonate Derivatives by Microwave-Assisted Kabachnik–Fields Reaction. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2015, 190, 655–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajti, Á.; Balint, E.; Keglevich, G. Synthesis of Ethyl Octyl α-Aminophosphonate Derivatives. Curr. Org. Synth. 2016, 13, 638–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, E.; Tóth, R.E.; Keglevich, G. Synthesis of alkyl α-aminomethyl-phenylphosphinates and N,N-bis(alkoxyphenylphosphinylmethyl)amines by the microwave-assisted Kabachnik-Fields reaction. Heteroat. Chem. 2016, 27, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajti, Á.; Szatmári, E.; Perdih, F.; Keglevich, G.; Bálint, E. Microwave-Assisted Kabachnik-Fields Reaction with Amino Alcohols as the Amine Component. Molecules 2019, 24, 1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, E.; Tripolszky, A.; Hegedus, L.; Keglevich, G. Microwave-assisted synthesis of N,N-bis(phosphinoylmethyl)amines and N,N,N-tris(phosphinoylmethyl)amines bearing different substituents on the phosphorus atoms. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

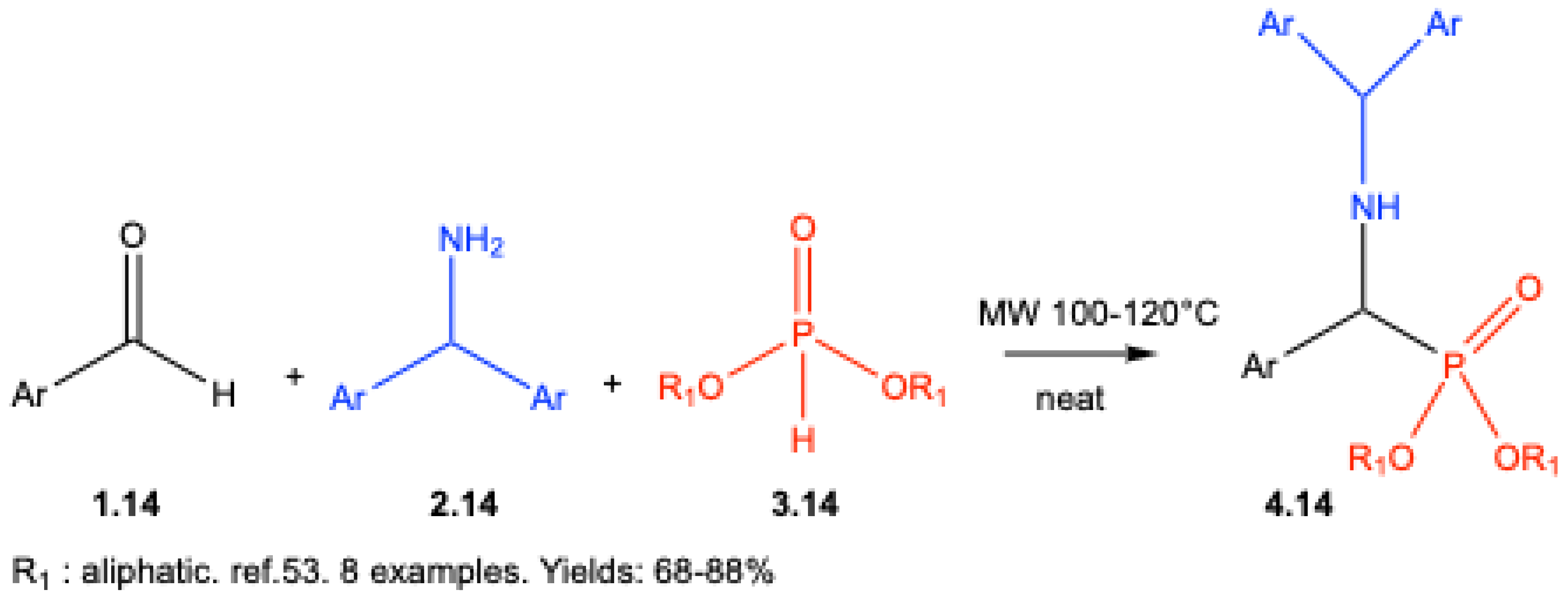

- Hudson, H.R.; Tajti, Á.; Bálint, E.; Czugler, M.; Karaghiosoff, K.; Keglevich, G. Microwave-assisted synthesis of α- aminophosphonates with sterically demanding α-aryl substituents. Synth. Commun. 2020, 50, 1446–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

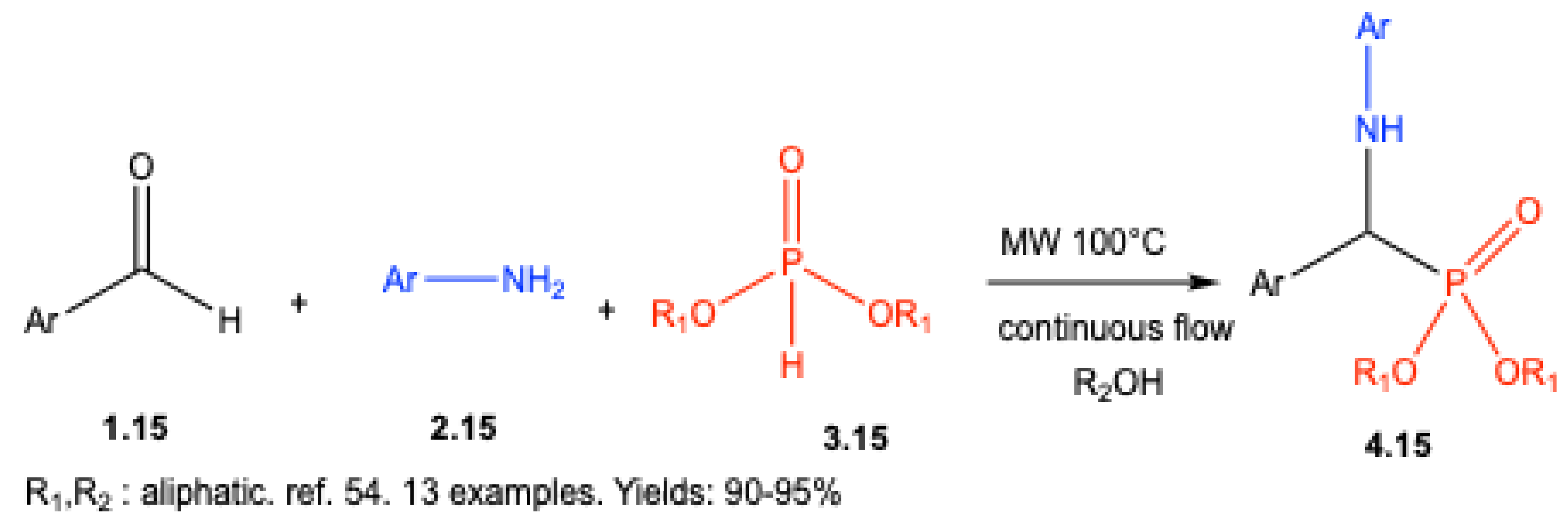

- Bálint, E.; Tajti, A.; Ladányi-Pára, L.; Tóth, N.; Mátravölgyi, B.; Keglevich, G. Continuous flow synthesis of α-aryl-α-aminophosphonates. Pure Appl. Chem. 2019, 91, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

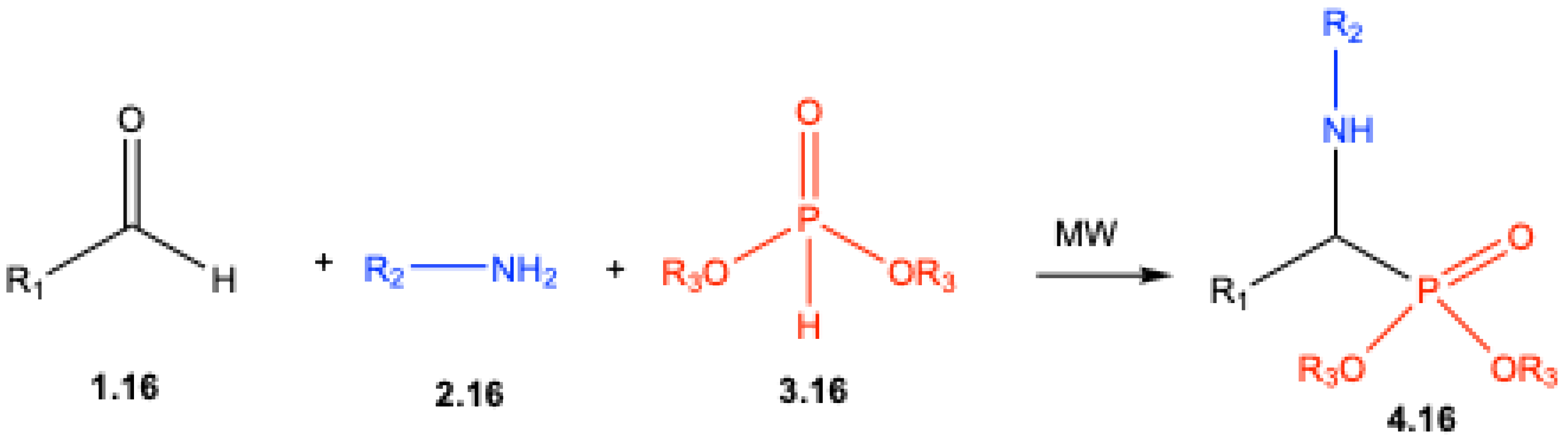

- Mu, X.; Lei, M.; Zou, J.; Zhang, W. Microwave-Assisted Solvent-Free and Catalyst-Free Kabachnik—Fields Reactions for α-Amino Phosphonates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2006, 47, 1125–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Campos, Z.; Elizondo-Zertuche, M.; Hernández-Núñez, E.; Hernández-Fernández, E.; Robledo-Leal, E.; López-Cortina, S. T. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Aminophosphonic Derivatives and Their Antifungal Evaluation against Lomentospora prolificans. Molecules 2023, 28, 3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

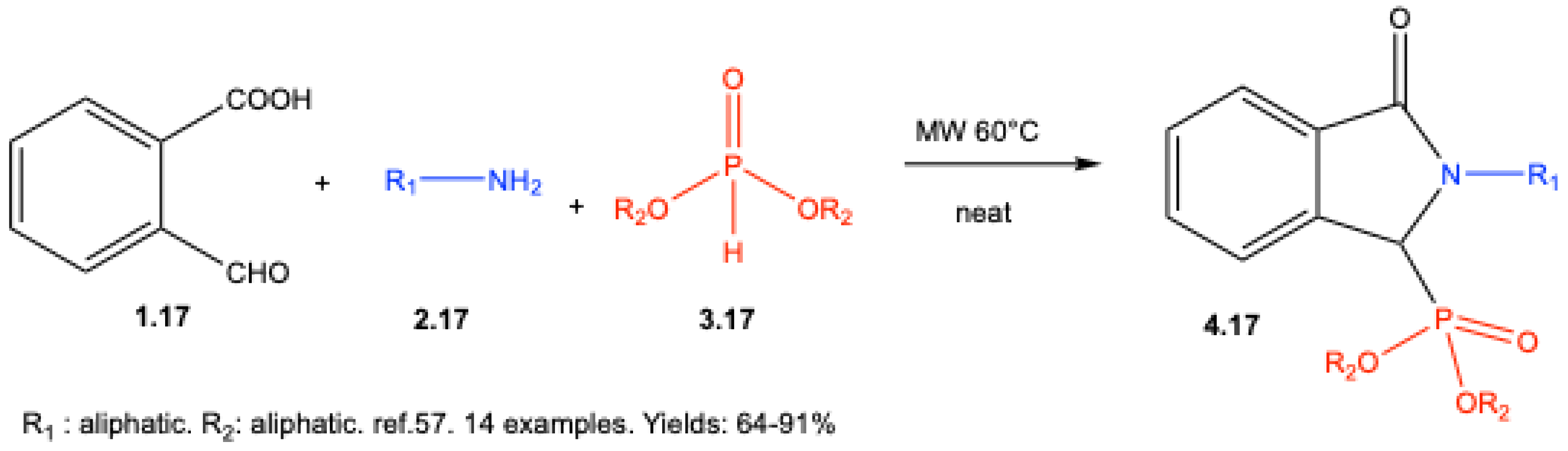

- Tajti, Á.; Tóth, N.; Rávai, B.; Csontos, I.; Szabó, P. T.; Bálint, E. Study on the Microwave-Assisted Batch and Continuous Flow Synthesis of N-Alkyl-Isoindolin-1-One-3-Phosphonates by a Special Kabachnik–Fields Condensation. Molecules 2020, 25, 3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

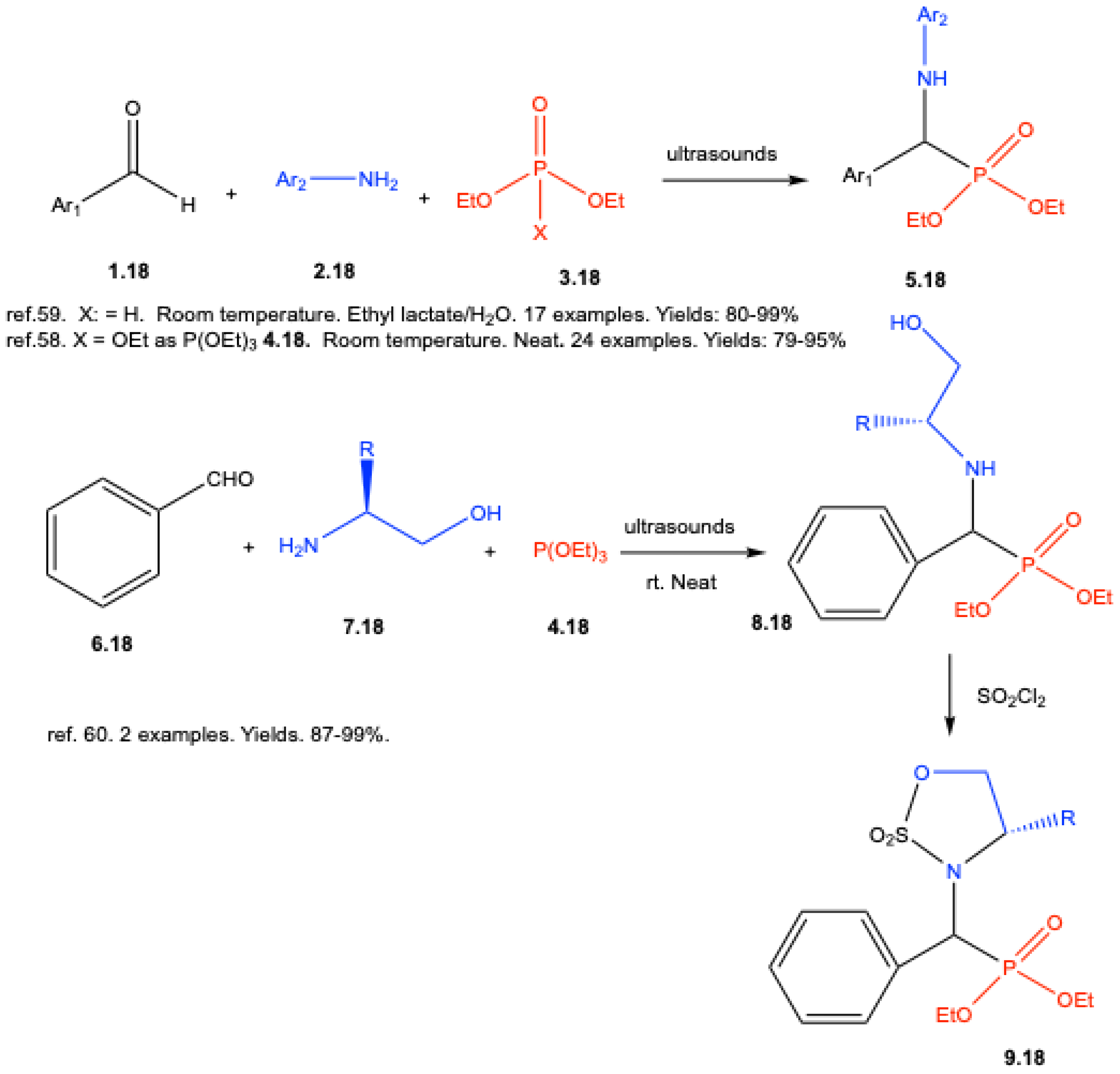

- Gao, G.; Chen, M. N.; Mo, L.- P.; Zhang, Z.- H. Catalyst free one-pot synthesis of α-aminophosphonates in aqueous ethyl lactate. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2018, 194, 528–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dar, B.; Singh, A.; Sahu, A.; Patidar, P.; Chakraborty, A.; Sharma, M.; Singh, B. Catalyst and solvent-free,ultrasound promoted rapid protocol for the one-pot synthesis of α-aminophosphonates at room temperature. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5497–5502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K’tir, H.; Amira, A.; Benzaid, C.; Aouf, Z.; Benharoun, S.; Chemam, Y.; Zerrouki, R.; Aouf, N. E. Synthesis, bioinformatics and biological evaluation of novel α-aminophosphonates as antibacterial agents: DFT, molecular docking and ADME/T studies. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1250, 131635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

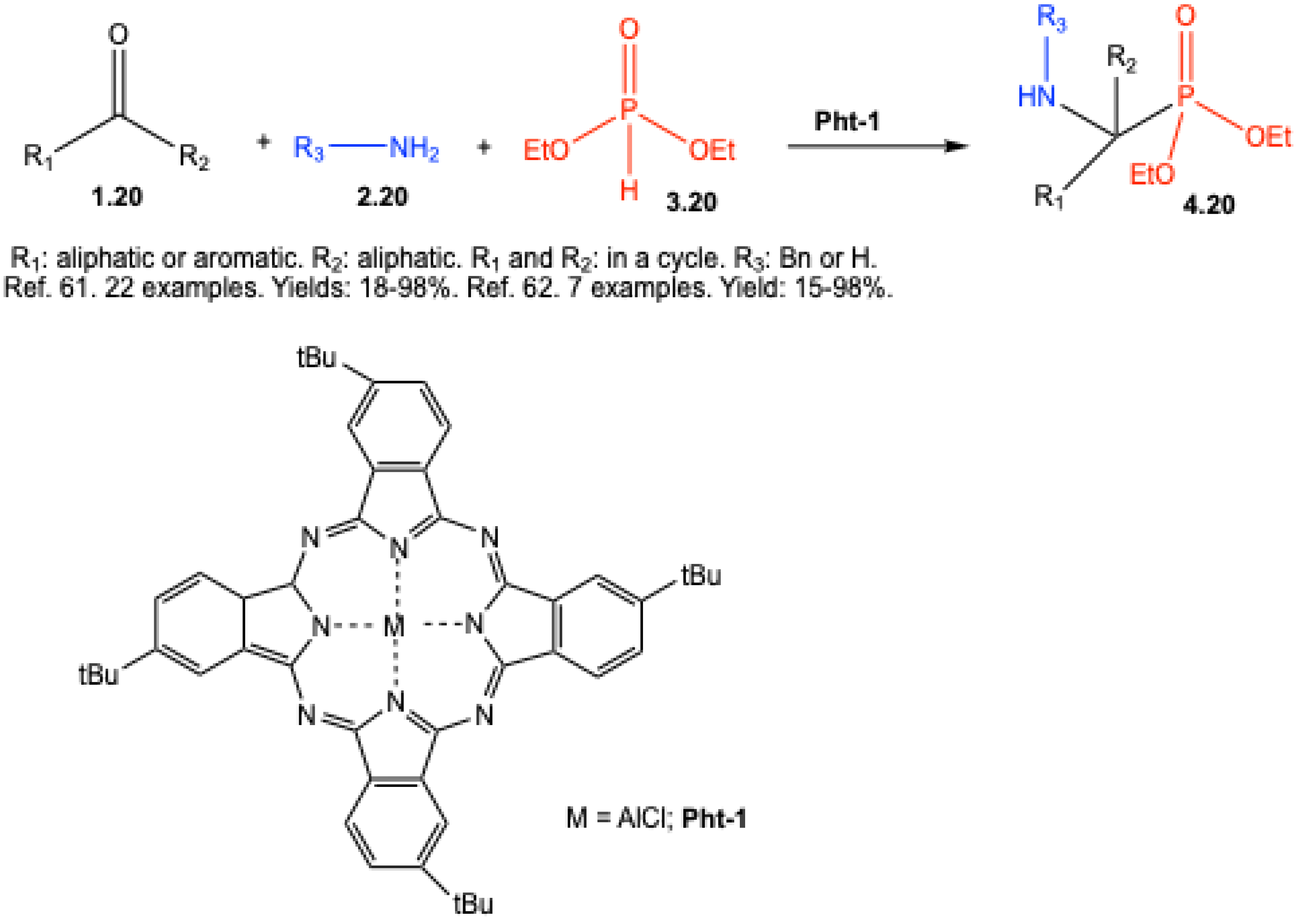

- Matveeva, E. D.; Podrugina, T. A.; Tishkovskaya, E. V.; Tomilova, L. G.; Zefirov, N. S. A Novel Catalytic Three-Component Synthesis (Kabachnick-Fields Reaction) of α-Aminophosphonates from Ketones. Synlett 2003, 2321–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuvalov, M. V.; Maklakova, S. Y.; Rudakova, E. V.; Kovaleva, N. V.; Makhaeva, G.F.; Podrugina, T.A. New Possibilities of the Kabachnik–Fields and Pudovik Reactions in the Phthalocyanine-Catalyzed Syntheses of α-Aminophosphonic and α- Aminophosphinic Acid Derivatives. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2018, 88, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

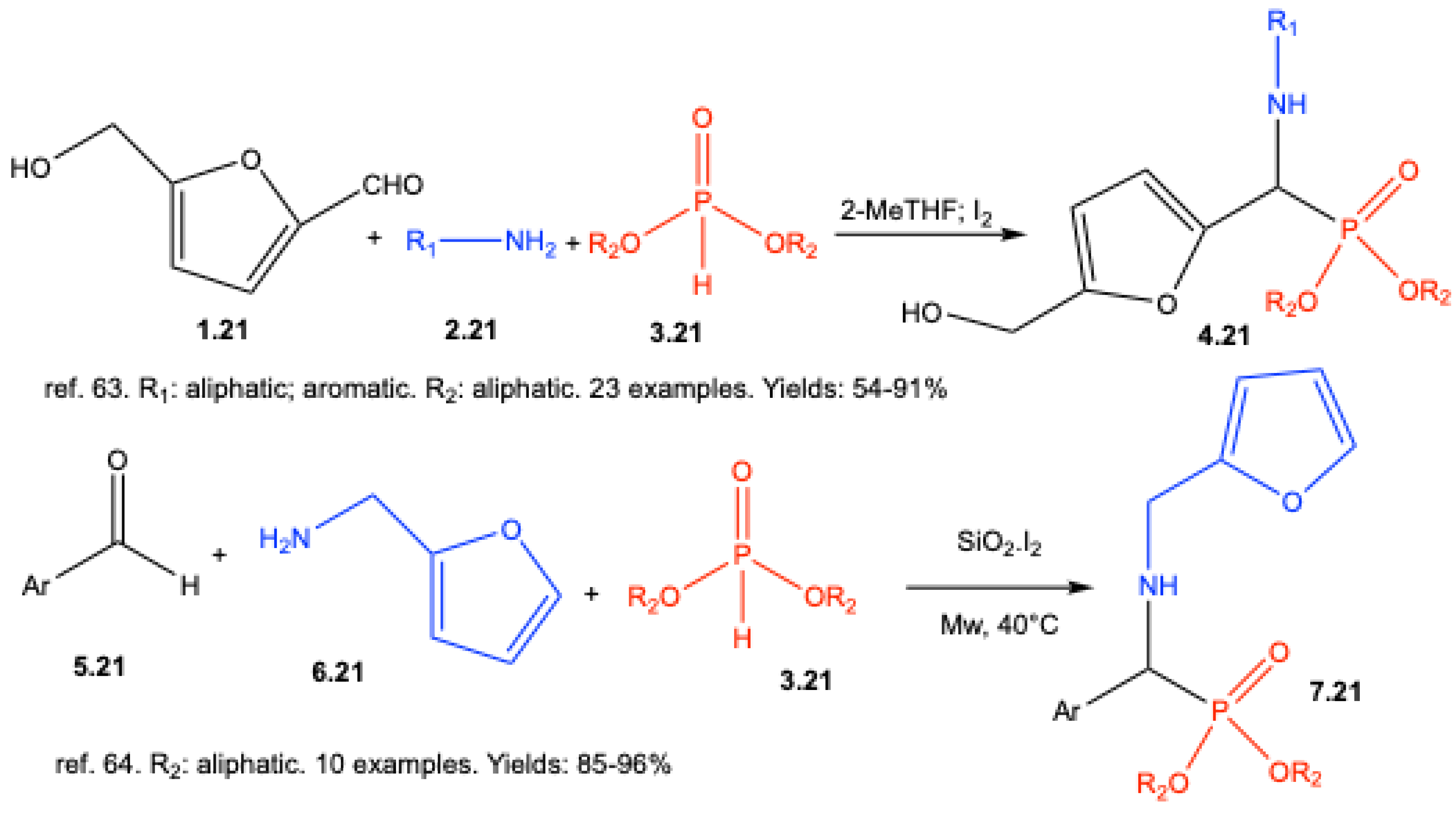

- Fan, W.; Queneau, Y.; Popowycz, F. The synthesis of HMF-based α-amino phosphonates via one-pot Kabachnik–Fields reaction. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 31496–31501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadiveedhi, M. R.; Nuthalapati, P.; Gundluru, M.; Yanamula, M. R.; Kallimakula, S. V.; Pasupuleti, V. R.; Avula, V. K. R.; Vallela, S.; Zyryanov, G. V.; Balam, S. K.; Cirandur, S. R. Green Synthesis, Antioxidant, and Plant Growth Regulatory Activities of Novel α-Furfuryl-2-alkylaminophosphonates. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 2934–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, A. A.; Nazarpour, M.; Abdollahi-Alibeik, M. CeCl3·7H2O-Catalyzed One-Pot Kabachnik–Fields Reaction: A Green Protocol for Three-Component Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates. Heteroat. Chem. 2010, 21, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, Z.; Firouzabadi, H.; Iranpoor, N.; Ghaderi, A.; Jafari, M. R.; Jafari, A. A.; Zare, H. R. Design and one-pot synthesis of α-aminophosphonates and bis(α-aminophosphonates) by iron(III) chloride and cytotoxic activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 4266–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manjula, A.; Rao; B. Neelakantan, P. One-pot synthesis of α-aminophosphonates: an inexpensive approach. Synth. Comm. 2003, 33, 2963–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambica, S.; Kumar, S. C.; Taneja, M. S.; Hundal, K.; Kapoor, K. One-pot synthesis of a-aminophosphonates catalyzed by antimony trichloride adsorbed on alumina Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 2208–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, S.; Prakash, S. J.; Jagadeshwar, V.; Narsihmulu, Ch. Three component coupling catalyzed by TaCl5–SiO2: synthesis of α-amino phosphonates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 5561–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z. P.; Li, J. P. Bismuth(III) Chloride–Catalyzed Three-Component Coupling: Synthesis of α-Amino Phosphonates. Synth. Commun. 2005, 35, 2501–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, S.; Chakraborti, A. K. Zirconium(IV) compounds as efficient catalysts for synthesis of α-aminophosphonates. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 6029–6032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, N.; Rajabi, F.; Saidi, M. R. A mild and highly efficient protocol for the one-pot synthesis of primary α-amino phosphonates under solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004, 45, 9233–9236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.-T.; Gao, J.-W.; Zhang, Z.-H. NbCl5: An efficient catalyst for one-pot synthesis of α-aminophosphonates under solvent-free conditions. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2010, 25, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-C.; Gong, S.-S.; Zeng, D.-Y.; You, Y.-H.; Sun, Q. Highly efficient synthesis of α-aminophosphonates catalyzed by hafnium(IV) chloride. Tetrahedron Lett. 2016, 57, 1782–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, A. S. V.; Sivaramakrishna, A. Facile InCl3-catalyzed room temperature synthesis and electrochemical behavior of ferrocene appended (R,S)-α-aminophosphonates. J. Mol. Struct. 2024, 1311, 138361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, M.; Eshghi, H.; Sabbaghzadeh, R. LaCl3⋅7H2O as an Effective Catalyst for the Synthesis of α- Aminophosphonates under Solvent-Free Conditions and Docking Simulation of Ligand Bond Complexes of Cyclin- Dependent Kinase 2. Polycycl. Aromat. Comp. 2022, 42, 5882–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basha, S. K. T.; Kalla, R. M. N.; · Varalakshmi, M.; Sudhamani, H.; Appa, R. M.; Hong, S. C.; Raju, C. N. Heterogeneous catalyst SiO2–LaCl3·7H2O: characterization and microwave-assisted green synthesis of α-aminophosphonates and their antimicrobial activity. Mol. Divers. 2022, 26, 2703–2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-G.; Park, J. H.; Kang, J.; Lee, J. K. Lanthanide triflate-catalyzed three component synthesis of α-amino phosphonates in ionic liquids. A catalyst reactivity and reusability study. Chem. Commun. 2001, 1698–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paraskar, A. S.; Sudalai, A. A novel Cu(OTf)2 mediated three component high yield synthesis of α-aminophosphonates. ARKIVOC 2006, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, R.; Maiti, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Maiti, D. K. (OTf)3 catalysed simple one-pot synthesis of α -amino phosphonates. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2004, 210(1–2), 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essid, I.; Touil, S. Efficient and Green One-Pot Multi-Component Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates Catalyzed by Zinc Triflate. Curr. Org. Synth. 2017, 14, 272–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewies, E. F.; El-Hussieny, M.; El-Sayed, N. F.; Fouad, M. A. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel α-aminophosphonate oxadiazoles via optimized iron triflate catalyzed reaction as apoptotic inducers. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 180, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. K.; Kaur, T. An Efficient One-Pot Synthesis of α-Amino Phosphonates Catalyzed by Bismuth Nitrate Pentahydrate. Synlett 2007, 745–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, J. S.; Reddy, B. V. S.; Madan, Ch. Montmorillonite Clay-Catalyzed One-Pot Synthesis of a-Amino Phosphonates. Synlett 2001, 1131–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrita, I. R.; Sousa, S. C.; Florindo, P. R.; Fernandes, A. C. Direct Aminophosphonylation of aldehydes catalyzed by cyclopentadienyl ruthenium(II) complexes. Tetrahedron 2018, 74, 1817–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keri, R.; Patil, M.; Brahmkhatri, V. P.; Budagumpi, S.; Adimule, V. Copper (II)-β-Cyclodextrin Promoted Kabachnik-Fields Reaction: An Efficient, One-Pot Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates. Top. Catal. 2025, 68, 1243–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboudin, B.; Moradi, K. A simple and convenient procedure for the synthesis of 1-aminophosphonates from aromatic aldehydes. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 2989–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasov, R. A.; Garifzyanov, A. R.; Koshkin, S. A. Synthesis of α-Aminophosphine Oxides with Chiral Phosphorus and Carbon Atoms. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2011, 186, 782–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkasov, R. A.; Garifzyanov, A. R.; Koshkin, S. A. Synthesis of optically active α-aminophosphine oxides and enantioselective membrane transport of acids with their participation. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2011, 81, 773–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagapova, L. I.; Burilov, A. R.; Voronina, J. K.; Syakaev, V. V.; Sharafutdinova, D. R.; Amirova, L. R.; Pudovik, M.A.; Garifzyanov, A. R.; Sinyashin, O. G. Phosphorylated Aminoacetal in the Synthesis of New Acyclic, Cyclic, and Heterocyclic Polyphenol Structures. Heteroat. Chem. 2014, 25, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagapova, L. I.; Burilov, A. R.; Amirova, L. R.; Voronina, J. K.; Garifzyanov, A. R.; Abdrachmanova, N. F.; Pudovik, M. A. New aminophosphonates (aminophosphine oxides) containing acetal groups in reactions with polyatomic phenols. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2016, 191, 1527–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, N.; Venkatanarayana, N.; Sharathbabu, H.; Ravendra Babu, K. Synthesis of novel α-aminophosphonates by methanesulfonic acid catalyzed Kabachnik–Fields reaction. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2021, 196, 1018–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitragotri, S. D.; Pore, S. D.; Desai, U. V.; Wadgaonkar, P. P. Sulfamic acid: An efficient and cost-effective solid acid catalyst for the synthesis of a-aminophosphonates at ambient temperature. Catal. Commun. 2008, 9, 1822–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, T.; Sanada, M.; Fuchibe, K. Brønsted Acid-Mediated Synthesis of α-Amino Phosphonates under Solvent-Free Conditions. Synlett 2003, 1463–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrimoti, S.; Bommena, V. R. (Bromodimethyl)sulfonium bromide: an inexpensive reagent for the solvent-free, one-pot synthesis of a-aminophosphonates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005, 46, 1209–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, N.; Kasana, V. K. Tartaric Acid–Catalyzed Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates Under Solvent-Free Conditions. Synth Commun. 2011, 41, 2800–2804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, M.; Tibhe, G.; Bedolla-Medrano, M.; Cativiela, C. Phenylboronic Acid as Efficient and Eco-Friendly Catalyst for the One-Pot, Three-Component Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates under Solvent-Free Conditions. Synlett 2012, 23, 1931–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, M.; Bedolla-Medrano, M.; Hernández-Fernández, E. Phenylphosphonic Acid as Efficient and Recyclable Catalyst in the Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates under Solvent-Free Conditions. Synlett 2014, 25, 1145–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellal, A.; Chafaa, S.; Touafri, L. An eco-friendly procedure for the efficient synthesis of diethyl α-aminophosphonates in aqueous media using natural acids as a catalyst. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 2366–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P.S.; Reddy, P.V.G.; Reddy, S.M. Phosphomolybdic acid promoted Kabachnik–Fields reaction: An efficient one-pot synthesis of α-aminophosphonates from 2-cyclopropylpyrimidine-4-carbaldehyde. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 3336–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaydeokara, S.; Yadava, V. G.; Bandivadekarb, P. V.; Chaturbhujb, G.; Chavan, V. L. N-(1-hydroxybutan-2-yl)-4-nitrobenzene sulfonamide: A novel organocatalyst for an effective one-pot synthesis of α-amino phosphonates. Results Chem. 2025, 16, 102295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatri, C. K.; Satalkar, V. B.; Chaturbhuj, G. U. Sulfated polyborate catalyzed Kabachnik-Fields reaction: An efficient and eco- friendly protocol for synthesis of α-amino phosphonates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 694–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoodlou, M. T.; Khorassani, S. M. H.; Hazeri, N.; Rostamizadeh, M.; Sajadikhah, S. S.; Shahkarami, Z.; Maleki, N. An Efficient Synthesis of α-Amino Phosphonates Using Silica Sulfuric Acid As a Heterogeneous Catalyst. Heteroat. Chem. 2009, 20, 316–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Hou, J.; Dou, J.; Lu, J.; Hou, Y.; Xue, T.; Zhang, Z. Xanthan sulfuric acid as an efficient biodegradable and recyclable catalyst for the one-pot synthesis of α-amino phosphonatesJ. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2010, 57, 1315–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, S.; Falatoonia, Z. M.; Honarmand, M. Synthesis of phosphoric acid supported on magnetic core–shell nanoparticles: a novel recyclable heterogeneous catalyst for Kabachnik– Fields reaction in water. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 15797–15805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, D.; Cheraghi, S.; Mahdudi, S.; Akbari, J.; Heydari, A. Dehydroascorbic acid (DHAA) capped magnetite nanoparticles as an efficient magnetic organocatalyst for the one-pot synthesis of α-aminonitriles and α-aminophosphonates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2013, 54, 6403–6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangireddy, C. S. R.; Chinthaparthi, R. R.; Mudumala, V.R.; Mamilla, M.; Arigala, U. R. S. An Efficient Green Synthesis of a New Class of α-Aminophosphonates under Microwave Irradiation Conditions in the Presence of PS/ PTSA. Heteroat. Chem. 2014, 25, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

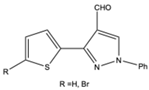

- Gundluru, M.; Badavath, V. N.; Shaik, H. Y.; Sudileti, M.; Nemallapudi, B. R.; Gundala, S.; Zyryanov, G. V.; Cirandur, S. R. Design, synthesis, cytotoxic evaluation and molecular docking studies of novel thiazolyl α-aminophosphonates. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2021, 47, 1139–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C. B.; Kumar, K. S.; Kumar, M. A.; Reddy, M. V. N.; Krishna, B. S.; Naveen, M.; Arunasree, M.; Raju, C. N. PEG-SO3H catalyzed synthesis and cytotoxicity of α-aminophosphonates. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 47, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tillu, V.; Dumbre, D.; Wakharkar, R.; Choudhary, V. One-pot three-component Kabachnik–Fields synthesis of α-aminophosphonates using H-beta zeolite catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, K.; Mitra, B.; Ghosh, P. Humic Acid: A Green-Catalyst-Mediated Solvent-Free Synthesis of Functionalized Diethyl(Phenyl(phenylamino)methyl)phosphonate. ChemistrySelect 2023, 8, e202301255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunde, S. P.; Kanade, K. G.; Karale, B. K.; Akolkar, H. N.; Arbuj, S. S.; Randhavane, P. V.; Shinde, S. T.; Shaikha, M. H.; Kulkarni, A. K. Nanostructured N doped TiO2 efficient stable catalyst for Kabachnik–Fields reaction under microwave irradiation. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 26997–27005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvari, M. H. TiO2 as a new and reusable catalyst for one-pot three-component syntheses of α-aminophosphonates in solvent-free conditions. Tetrahedron 2008, 64, 5459–5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agawane, S. M.; Nagarkar, J. M. Nanoceria catalyzed synthesis of α-aminophosphonates under ultrasonication. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 3499–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K. M. K.; Santhisudha, S.; Mohan, G.; Peddanna, K.; Rao, C. A.; Reddy, C. S. Nano Gd2O3 catalyzed synthesis and anti-oxidant activity of new α-aminophosphonates. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2016, 191, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, P.; Santhisudha, S.; Reddy, G. R.; Subbarao, Y.; Peddanna, K.; Apparao, C.; Reddy, C.S. Nano-Cuo–Au-catalyzed solvent-free synthesis of α-aminophosphonates and evaluation of their antioxidant and α-glucosidase enzyme inhibition activities. Synth. Commun. 2018, 48, 1148–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummadi, R. R.; Ratnakaram, V. R.; Devineni, S. R.; Subramanyam, C.; Pavuluri, C. M. Eco-friendly TiO2–ZnO nano-catalysts: synthesis, catalytic performance in synthesis of α-amino/ hydroxyphosphonates and their ADME, docking and antimicrobial studies. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2025, 51, 3767–3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahani, A.; Rao, R. S.; Vadakkayl, A.; Santhosh, M.; Mummoorthi, M.; Karthick, M.; Ramanathan, C. R. Niobium pentoxide, a recyclable heterogeneous solid surface catalyst for the synthesis of α-amino phosphonates. J. Chem. Sci. 2021, 133, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovics-Tóth, N.; Szabó, K. E.; Bálint, E. Study of the Three-Component Reactions of 2-Alkynylbenzaldehydes, Aniline, and Dialkyl Phosphites—The Significance of the Catalyst System. Materials 2021, 14, 6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, K.; Egami, T. Facile synthesis of α-amino phosphonates in water by Kabachnik-Fields reaction using magnesium dodecylsulfate. Heteroat. Chem. 2011, 22, 358–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anupama, B.; Andria, A. A.; Jisha, M. T.; Anila, R. C.; Letcy, V. T. Glucose-Urea-Choline chloride: a versatile catalyst and solvent for the Kabachnik-Fields’ reaction. J. Mol. Liq. 2025, 434, 128079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, P. R.; Keglevich, G. The Last Decade of Optically Active α-Aminophosphonates. Molecules 2023, 28, 6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mucha, A.; Kafarski, P.; Berlicki, L. Remarkable Potential of the r-Aminophosphonate/Phosphinate Structural Motif in Medicinal Chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 5955–5980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, M.; Nakamura, S.; Shibata, N. Direct Enantioselective Three-Component Kabachnik–Fields Reaction Catalyzed by Chiral Bis(Imidazoline)-Zinc(II) Catalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2011, 353, 3285–3289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zheng, L.; Chakraborty, D.; Borhan, B.; Wulff, W. D. Zirconium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Kabachnik–Fields Reactions of Aromatic and Aliphatic Aldehydes. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 12333–12345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, P. S.; Reddy, M. V. K.; Reddy, P. V. G. Camphor-Derived Thioureas: Synthesis and Application in Asymmetric Kabachnik–Fields Reaction. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 943–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, B.; Egami, H.; Katsuki, T. Synthesis of an Optically Active Al(Salalen) Complex and Its Application to Catalytic Hydrophosphonylation of Aldehydes and Aldimines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1978–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Shang, D.; Zhang, Q.; Lin, L.; Liu, X.; Feng, X. Enantioselective Three-Component Kabachnik-Fields Reaction Catalyzed by Chiral Scandium(III)-N,N′-Dioxide Complexes. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 1401–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Goddard, R.; Buth, G.; List, B. Direct Catalytic Asymmetric Three-Component Kabachnik–Fields Reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 5079–5081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Cui, S.; Meng, W.; Zhang, G.; Nie, J.; Ma, J. Asymmetric Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates by Means of Direct Organocatalytic Three-Component Hydrophosphonylation. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2010, 55, 1729–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Huang, J.; Liao, N.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Peng, Y. Catalytic Asymmetric Three-Component Reaction of 2-Alkynylbenzaldehydes, Amines, and Dimethylphosphonate. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 6932−6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorat, P. B.; Goswami, S. V.; Magar, R. L.; Patil, B. R.; Bhusare, S. R. An Efficient Organocatalysis: A One-Pot Highly Enantioselective Synthesis of α-Aminophosphonates. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 24, 5509–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bálint, E.; Tajti, Á.; Kalocsai, D.; Mátravölgyi, B.; Karaghiosoff, K.; Czugler, M.; Keglevich, G. Synthesis and utilization of optically active α-aminophosphonate derivatives by Kabachnik-Fields reaction. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 5659–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viveros-Ceballos, J. L.; Cativiela, C.; Ordóñez, M. One-pot three-component highly diastereoselective synthesis of isoindolin-1- one-3-phosphonates under solvent and catalyst free-conditions. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 2011, 22, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez, M.; Tibhe, G.; Zamudio-Medina, A.; Viveros-Ceballos, J. An Easy Approach for the Synthesis of N-Substituted Isoindolin-1-ones. Synthesis 2012, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Gonzalez, M. A.; Zamudio-Medina, A.; Ordóñez, M. Practical and highstereoselective synthesis of 3-(arylmethylene)isoindolin- 1-ones from 2-formylbenzoic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2012, 53, 5756–5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||||

| Entry |

Aldehydes or Ketones |

Amines | Phosphites | Catalyst | Yields | Ref. |

| 1 | Aromatic Cyclohexanone |

Aromatic | Diethyl | CeCl3.7H2O | 21 examples: 87-95% |

[65] |

| 2 | Aromatic | Aromatic | Diethyl | FeCl3 | 9 examples: 87-95% |

[66] |

| 3 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic |

Trimethyl | AlCl3 or ZrCl4 | 11 examples: 66.87% |

[67] |

| 4 | Aromatic | Aromatic, Heteroaromatic, Aliphatic | Dimethyl Diethyl |

SbCl3 on SiO2 | 26 examples: 49-92% |

[68] |

| 5 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic Acetophenone |

Aromatic | Diethyl | TaCl5 on SiO2 | 18 examples: 81-94% |

[69] |

| 6 | Aromatic Aliphatic Cyclic ketones |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Dimethyl Diethyl |

BiCl3 | 18 examples: 70-95% |

[70] |

| 7 | Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic Cyclohexanone |

Aromatic Heteroaromatic Aliphatic |

Dimethyl Diethyl |

ZrOCl2·8H2O | 56 examples: 70-96% |

[71] |

| 8 | Aromatic | (Me3Si)2NH | Trimethyl Triethyl |

LiClO4 | 9 examples: 82-92% |

[72] |

| 9 | Aromatic | Aromatic | Diethyl | NbCl5 | 19 examples: 87-95% |

[73] |

| 10 | Aromatic Aliphatic |

Aromatic Aliphatic |

Dimethyl Diethyl Trimethyl Triethyl |

HfCl4 | 23 examples: 82-98% |

[74] |

| 11 | Ferrocene 2-carboxaldehyde | Aromatic | Diethyl Diphenyl |

InCl3 | 8 examples: 88-95% |

[75] |

| 12 | Aromatic | Aromatic | Dimethyl | LaCl3·7H2O | 10 examples: 60-96% |

[76] |

| 13 | Aromatic | Derivatives of benzothiazole or thiadiazole |

Diethyl | LaCl3·7H2O on SiO2 | 32 examples: 87-97% |

[77] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).