Introduction

It is estimated that between 300 and 350 million tons of plastic are produced yearly where a significant proportion find their way in most aquatic environments worldwide [

1,

2]. They are also found in nearly all natural compartments (water, sediments, air) and biota. These materials degrade by both abiotic and biotic processes including the formation of biofilms composed of microbial communities so-called the plastisphere. This follows by the formation of smaller and smaller size micro (mm-µm) and nanoparticles (1-1000 nm). During the breakdown of plastic particles, the number of particles increases exponentially. For example, a 1 mm diameter particle contains 10

9 1 µm diameter particles and 10

15 10 nm diameter particles based simply on the volume of sphere. Both micro and nanoplastics could threaten organisms as they mistakenly consider them as food source especially by filter feeders, such as bivalves [

3,

4]. While MPs remain in the gut and cause mechanical damage, plastic nanoparticles (PNPs) share the potential to enter cells and disrupt cellular organization, DNA integrity and redox status of cells [

5]. Due to these properties, both micro and PNPs threaten organisms that feed on suspended particles such as bivalves [

6]. Mussels thrive in many aquatic environments (lakes and rivers) rich in nutrients near urban and agriculture sectors and their decline have been noticed [

7].

Once internalized in cells, PNPs stimulate the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) through disruption of antioxidant levels and antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase and peroxidase leading to poor growth and decreased survival [

8]. ROS are eliminated by a suite a well-known antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase and peroxidase. Peroxidases eliminate H

2O

2 by the oxidation of a reducing endogenous or exogenous compound (ascorbate, glutathione, vitamin E). When H

2O

2 is not quickly removed they could, in turn, damage biological molecules such as lipids, proteins and nucleic acids [

9]. The consequences of theses oxidative damage are unsaturated lipid oxidation ((lipid peroxidation), protein oxidation leading to denaturation and aggregation (amyloidosis) and oxidized DNA (8-oxoguanosine) contributing to poor health, growth and reproduction on the long-term. In zebra mussels, the effects on survival were low, dropping to 86% when exposed to 60 mg/L of 100 nm diameter green, fluorescent nano-polystyrene spheres (PsNPs) for 96h [

5]. Filtration rates were also reduced at 60 mg/L but oxidative stress (lipid peroxidation) and DNA damage was observed at a threshold concentration of 28 mg/L and <20 mg/L respectively. Moreover, the hydrophobic nature of PNPs surface brings about interaction with lipids and hydrophobic (membrane bound) proteins. Lipid mobilization in cells were previously shown by PNPs and involved the activity of esterase for lipid (fatty acid) anabolism. Moreover, microbial communities and biofilms growing on ester-based plastics (PET, polyesters, polyurethanes) were shown to display high esterase activity [

10,

11]. Hence, increased esterase activity by PNPs could be associated to both lipid metabolism and biodegradation/biotransformation to favor elimination from cells [

12]. PNPs were previously found to increase protein aggregation leading to insoluble plaques often observed in aged tissues and degeneration pathologies [

13,

14]. Understanding how organisms cope towards plastic materials in their environment is warranted to understand their impacts and contributes to reducing plastic pollution to ensure a sustainable future.

The objective of this study was therefore to investigate the lethal and sublethal toxicitiy of 2 plastic polymers polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and a ester based plasticizer dibutylphthalate (DBP) to freshwater quagga mussels. The levels of plastic-like materials and DBP were determined in soft tissues following a 96 h period at 15oC. Survival and sublethal effects were determined in mussels by a suite of biomarkers for oxidative stress, protein aggregation and lipid energy reserves. An attempt was made to relate the observed changes in respect to mussel survival.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plastic Particles and Dibutylphthalate

This work focused on two of the most found plastics in the environment: PET and PVC along with polystyrene, polypropylene and polyethylene. PET particles with a mean diameter of 2.2 µm were purchased as powder from Nanochemazone (Alberta, Canada). A working stock solution of 0.1 g/mL was prepared in MilliQ water in a fume hood as recommended for the safe handling of powders. The stability of the solution was examined by measuring UV absorbance (260 nm) of the suspension at 1 min and 1 h following dissolution. No evidence of precipitation/coagulation was observed. PVC with an average molecular weight of 233 000 daltons (estimated length of 580 nm) was purchased in solution at 1.4 g/mL density from Sigma-Aldrich (Ontario, Canada). DBP was purchased as liquid from Sigma-Aldrich (Ontario, Canada). A stock solution was prepared in ethanol at 10 g/mL and diluted to 500 µg/L, which was below the reported solubility of DBP in water (circa 6 mg/L). No appearance of precipitation and turbidity was observed and confirmed by UV (260 nm) of the suspension after 1h. Preliminary experiments revealed that the 100 µg/L exposure concentration was stable after 1 h (95-98% recovery) based on UV absorbance (254 nm) following filtration on 0.45 µm pore cellulose acetate membrane (

Table 1S).

2.2. Exposure of Quagga Mussels to Plastic Materials

Quaggas (

Dreissena burgensis) mussels were found attached on the pillars of wharf on the south shore of the Saint-Lawrence River (Longueil, Qc, Canada). They were delicately removed by a knife and transported back to the laboratory at 4

oC (

Figure 1S). They were separated from their abyssal treads with a scalpel and stand for one month in UV-charcoal treated tap water (pH 7.8, conductivity 280 µS x cm

-1) under constant aeration at 15

oC. They were fed with commercial coral reef algal suspension three times a week. For the exposure experiment, 16 mussels of similar size range (1.5-2.5 cm shell length) were placed in 4L Pyrex glass beakers in aquarium water and exposed to increasing concentrations of PET and PVC nanoparticles: 0, 5, 50 and 100 µg/L for 96h at 15

oC under constant aeration at 98-99% oxygen saturation. The aquarium water was dechlorinated and UV treated tap water of the City of Montréal (pH 7.8, conductivity 280 uScm-1, dissolved organic carbon 0.5-1 mg/L and ammonia < 0.1 mg/L). Mussels were also exposed to the plasticizer DBP at the same concentration. The exposure concentrations were expressed as nomical concentration in mg/L.

2.3. Post-Exposure Handling and Tissue Preparations

At the end of exposure period, mussels were allowed to stand in aquarium water for 3 h at room temperature to allow removal of unattached plastic materials. The mussels’ weight and shell length were determined and placed on ice to remove the soft tissues (weighted). The condition factor (CF; g mussels/shell length in mm) and soft tissue index (SFTI; g soft tissues/g mussels) were then determined. The soft tissues from each mussels were then homogenized in 4 volumes of 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Hepes-NaOH, 1 mM EDTA, 1 µg/mL apoprotinin, pH 8 buffer using a Teflon pestle tissue grinder (5 passes at 4oC). The homogenate was centrifuged at 100 × g for 5 min at 2 °C to remove large debris or tissue aggregates. The supernatant was collected and stored at −85 °C until analysis.

2.4. Extraction and Tissue Analysis of Plastic Nanoparticles and Dibutylphthalate

A 300 µL volume of the homogenates was extracted in 1 volume of saturated NaCl (5 M) and one volume of acetonitrile (ACN), mixed for 10 min, and centrifuged at 150 ×

g for 5 min to separate the ACN phase. The levels of plastics were determined using the Nile red solvatochromic methodology as previously described [

15]. Briefly, 50 µL of the homogenate fraction was mixed with 150 µL of Nile Red (10 µM in phosphate buffered saline-PBS) and analyzed for fluorescence between 520-700 nm at 485 nm excitation. The first derivative of fluorescence was calculated. A fluorescent characteristic peak was observed at 610-620 nm for plastic materials. Standard solution of polystyrene nanoparticles was used for calibration (20 nm diameter, Thermofisher Inc, USA). The determination of DBP in tissues was determined using arginine-coated nAu sensor as previously described [

16]. First, citrate-coated 10 nm nAu nanoparticles at 25 mg/mL were purchased from Nanocomposix (USA) and centrifuged at 20 000 x g for 10 min at 4

oC to remove excess citrate from the pelleted nAu. The pellet was resuspended in 0.01% arginine for 3 h at room temperature. Another centrifugation step (similar speed) to remove excess and unbound arginine was done. The assay consisted in mixing 150 µL of arginine-nAu with 10 µL of the acetonitrile fraction, and 10 µL of HCl 0.1 M. The absorbance was then measured between 500-750 nm to determine changes between dissociated nAu (A 530 nm) and aggregated nAu (A 620 nm), which was increased for the latter in the presence of DBP.

2.5. Biomarker Analysis

The remaining homogenate was used for the determination of esterase, lipids, peroxidase and protein aggregation. The homogenate was centrifuged at 500 x g for 5 min at 2

oC to remove large aggregates or tissue debris. The activity of peroxidase was determined using dichlorofluorescein (DCF) fluorometric reagent. Briefly, 20 µL of the supernatant was mixed with 0.1% H202 and 10 µM DCF in PBS for 20 min at 22

oC. Fluorescent readings at 485 nm excitation and 520 nm emission were taken each 2 min using a microplate reader for 20 min in dark 96-well microplates (Synergy IV, Biotek Instrument, CA. USA). The data was expressed as the increase in relative fluorescent unit (RFU) /min/g soft tissues (wet weight). Esterase activity was determined using p-nitrophenyl acetate (PNPA) as the substrate. Briefly, 50 µM of PNPA was mixed with 50 µL of homogenate and completed to 200 µL in PBS in clear microplates. The appearance of p-nitrophenolate ion was measured at 412 nm at each 5 min for 30 min using a microplate reader described above. The data was expressed as absorbance increase/min/g soft tissues. Protein aggregations (amyloids) were determined using thioflavine T fluorescent methodology [

17]. A 50 μL sample of the homogenate supernatant was added to 150 μL of 100 μM thioflavine T in PBS for 10 min. Fluorescence was measured at 400 nm excitation and 485 nm emission in dark microplates using the Synergy-4 fluorometer. Data were expressed as relative fluorescence units (RFU)/ g soft tissues. The levels of aldehydes were determined using the microplate 4-aminofluorescein assay [

18]. Briefly, 20 μL of supernatant was mixed to 180 μL of 4-aminofluorescein (10 µM in PBS) and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. Fluorescence (excitation 485 nm, emission 530 nm) was measured in dark microplate reader as described above. The data were expressed as RFU/ g soft tissues. Finally, lipid levels were determined using the commercial lipid assay using Nile red as previously described [

19]. Calibration was achieved with standard solutions of olive oil. The data was expressed as µg lipids/g soft tissues.

2.6. Data Analysis

A number of 8 mussels per beaker was used for biomarker analyses and the experiments were repeated 3 times. The data were expressed as the mean with standard error. The data were log-transformed and subjected to analysis of variance followed by the Least Square difference test to find changes from controls. Correlation analysis was performed using the Pearson-moment procedure for hierarchical tree analysis. All statistical tests were performed using the StatSoft software package (version 13). A threshold level of significance of α = 0.05 was used.

3. Results

During the exposure experiments, exposure to the plastics particles did not produce significant changes in survival (

Table 1). In the PET exposure group, a marginal decrease in survival was detected at 5 and 50 µg/L (3 mortality out of the 3x8 mussels) but with no clear dose-response. However, survival decreased to 12% for DBP at the 50 µg/L exposure concentration and all mussels died at the 100 µg/L exposure group. The reported changes in the 50 µg/L DBP group were performed in the surviving mussels (4 mussels from the 3 beakers of 8 mussels) i.e., in lethal conditions. The levels of PET, PVC, and DBP were determined in soft tissues using the Nile Red and nAu sensor methodologies (

Table 1;

Figure 2SA). In mussels exposed to PVC, significant levels of plastics were detected at the highest concentrations (50 and 100 µg/L) reaching 9 ug/g tissues. A tentative bioavailability factor of 90 (9 mg/kg/0.1 mg/kg) was obtained for this plastic. For PET, significant increases in plastics were detected at 50 and 100 µg/L reaching 4 µg/g tissues. A provisionary bioavailability factor of 40 (4 mg/kg/0.1 mg/kg) was obtained for this PNPs. Fish survival was significantly correlated with plastic levels (r=-0.4; p<0.05). For DBP, the levels of DBP in tissues were increased to 79 µg/g giving a bioavailability potential of 1580 (

Table 1,

Figure 2SB). Based on the relationship the octanol coefficient and bioconcentration potential: log (Bioconc factor) =0.542 log (Kow) + 0.124 [

20], we obtained an equivalent logKow of 3.37 (95% CI: 2.9-4.4), 2.72 (95% CI:2.1-3.1), and 5.6 (95% CI: 4.5-6.5) for PVC, PET and DBP respectively. This suggests that the polarity of these plastics is higher than DBP. It was noteworthy that DBP levels were detected in the plastic exposure groups (PET and PVC) at concentrations between 12-47 µg/g tissues indicating the presence of DBP in these plastic polymers.

The health status of mussels was determined by measuring a suite of biomarkers at the different levels of biological organization (

Table 2 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The condition factor (CF) was generally lower in the exposure group with a significant decrease at 5, 50 and 5 µg/L for PET, PVC and DBP respectively (

Table 2). The decrease in soft tissues index (SFTI) was only apparent in mussel exposed to a lethal concentration of 50 µg/L DBP. The levels of lipids were also determined in soft tissues. The results revealed that lipids levels were generally increased by exposure to these plastics materials where the increases were higher in the PET exposure group compared to PVC and DBP groups. The levels of esterase were also measured given the presence of ester-based plastics such as PET and the plasticizer DBP as biotransformation means to hydrolyse these compounds for elimination. The data revealed that esterase activity was readily induced in mussels exposed to DBP. A marginal decrease in esterase in the PET exposure group was also observed. Moreover, esterase activity was significantly correlated DBP levels (r=0.5; p<0.05) but not with plastic levels albeit marginally (r=0.35; p=0.08). Esterase activity was not correlated with lipid levels since catabolic enzymes (lipase) are esterases could mobilize lipids in tissues. The activity of peroxidase and protein carbonyls were also determined in mussel tissues (

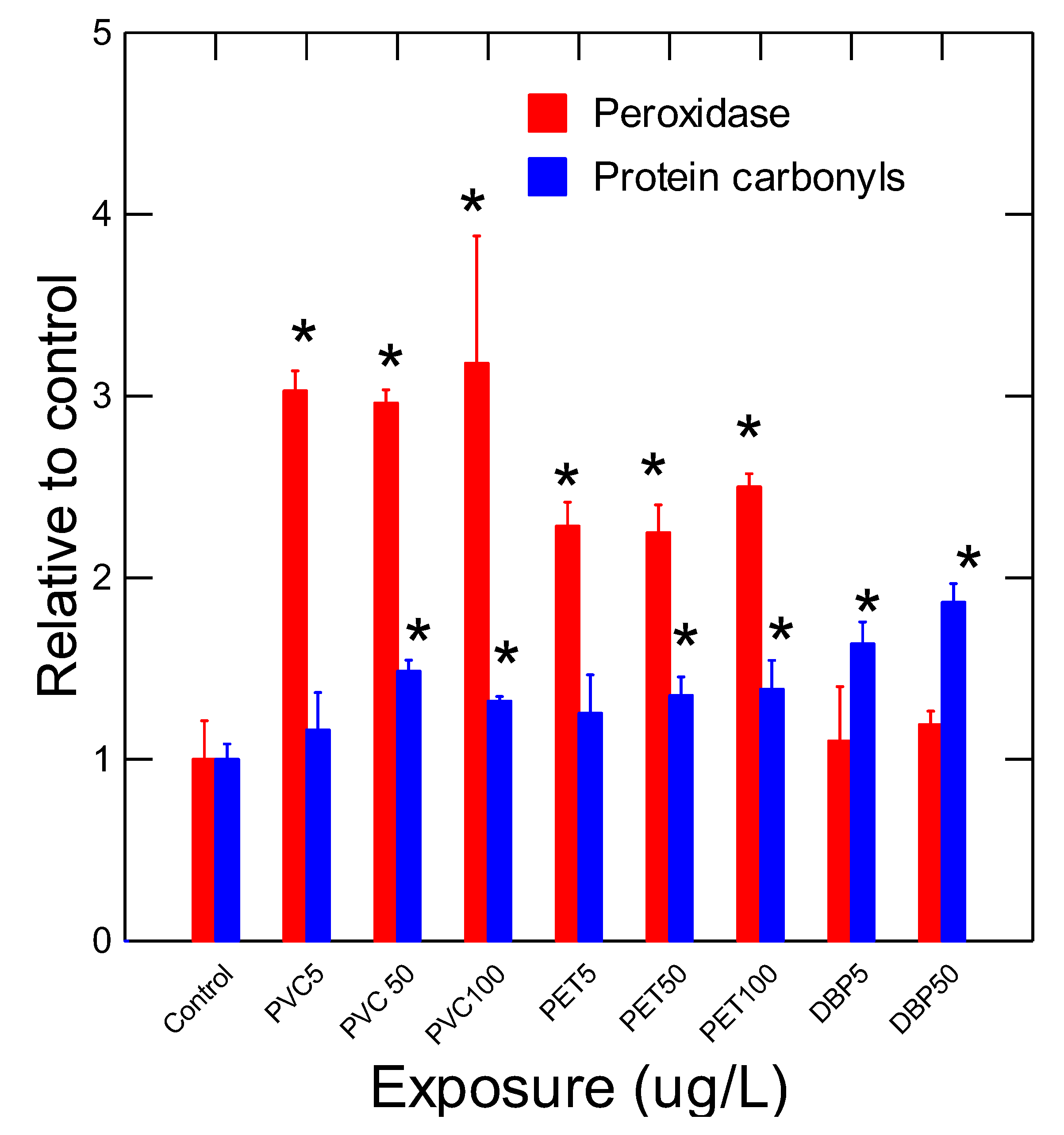

Figure 2). Peroxidase activity was significantly increased at 5 µg/L concentration for PVC and PET plastics. Exposure to DBP did not significantly increase peroxidase activity in mussels. Peroxidase was significantly correlated with survival (r=0.41), CF (r=-0.43) and esterase activity (r=-0.45). This suggests that low plastic biotransformation (esterase) is associated to increased peroxidase involved in the elimination of oxygen radicals. The levels of protein aggregation (amyloids) were also determined in soft tissues (

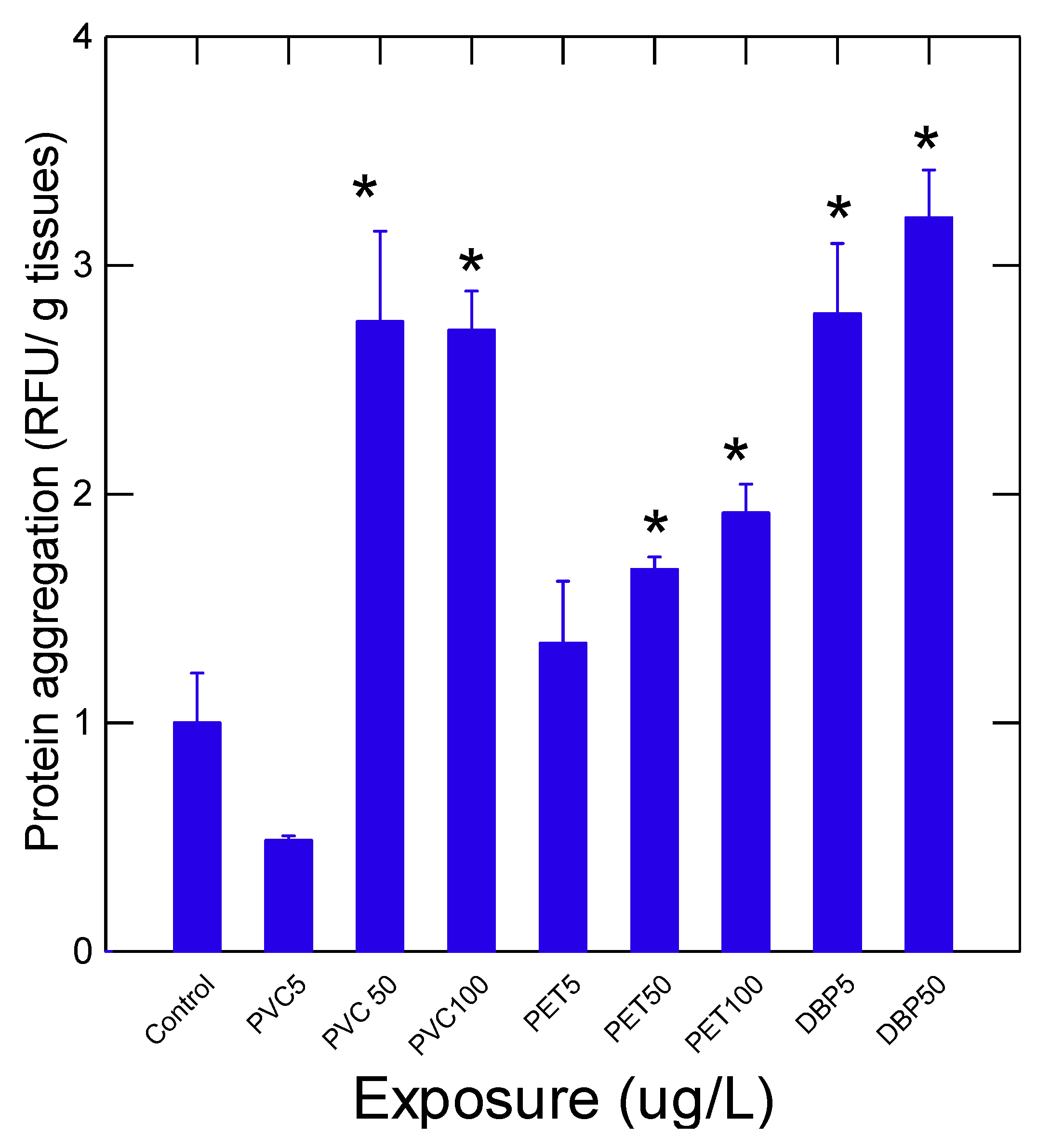

Figure 2). Protein aggregation was significantly induced by 50 ug/L PVC and PET. For DBP, protein aggregation was induced at 5 and 50 ug/L. Correlation analysis revealed that protein aggregation was significantly correlated with survival (r=-0.47), plastic tissue levels (r=0.63), DBP (r=0.49), carbonyls (r=0.65) and esterase activity (r=0.47).

Oxidative stress was determined by measuring peroxidase activity and the levels of protein carbonyls in soft tissues of mussels. The data RFU/min/g tissues and RFU/g tissues for peroxidase and protein carbonyls respectively and normalized to controls for easy visualization. Tata represents the mean with the standard error. The star * symbol indicates significance (p<0.05) relative to solvent controls.

The levels of protein aggregation (amyloids) were determined using the Thioflavine T probe in soft tissues homogenates. The data represents the mean with the standard error. The star * symbol indicates significance (p<0.05) relative to solvent controls.

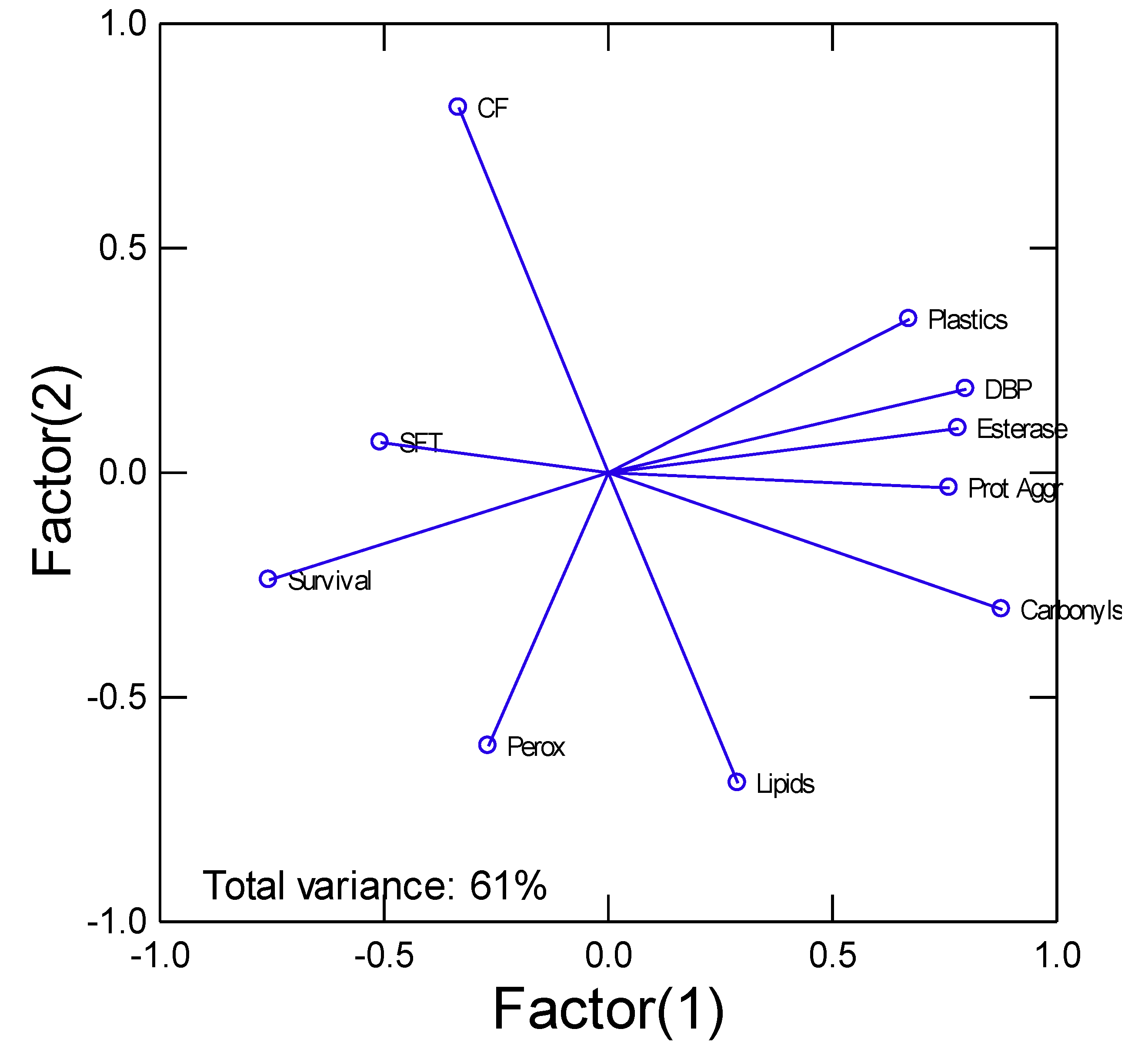

In the attempt to gain a global understanding, cluster analysis was performed (Figure 3). The analysis revealed that tissue plastic and DBP levels were closely related to protein aggregation, carbonyls and esterase activity. These were negatively related to survival where low survival was involved in higher levels of biomarkers mentioned above.

The biomarker data of exposure (plastics and DBP levels) and effects ( peroxidase, lipids, carbonyls, protein aggregation, CF, SFT and survival) were analysed by principal component analysis. The total explained variance was 61%. The most important biomarkers (factorial weights>0.7) were survival, CF, carbonyls, protein aggregation (amyloids), esterase, DBP and plastics. DBP (dibutylphthalate), Prot Aggr (protein aggregation/amyloids), Perox (peroxidase), CF (condition factor), SFT (soft tissues weight/mussel weight)

Figure 3.

Cluster analysis of biomarker data.

Figure 3.

Cluster analysis of biomarker data.

4. Discussion

In this study, the levels of plastics were determined using the fluorescent Nile red dye, which is known to react to miscellaneous types plastic polymers including PET and PVC [

21,

22]. However, the measured levels of plastic materials should be taken as a relative amount expressed as equivalent amounts of polystyrene nanoparticles standard (20nm diameter). The plastic levels determined with the Nile red methodology were consistent with the occurrence of DBP in tissues, which is in keeping with the previous observation of DBP levels and plastic contamination in the aquatic environment [

23]. Indeed, following the measurement of microplastics and DBP in rivers, a positive correlation was observed between microplastics and DBP concentrations. Although not applicable here, UV irradiation from sunlight was the main factor for DBP leaching from polyethylene microplastics. It appears that leaching of DBP from plastic materials could be significant in tissues. Indeed, based on the bioavailability data of PVC/PET and DBP, the estimatged logKow of DBP was at 5.6 (95% CI: 4.3-6.9), which was in lower range of the reported and computed logKow of 4.5-4.7 [

24] (Dibutyl Phthalate | C16H22O4 | CID 3026 - PubChem). DBP is thus considered highly bioavailable in both fish and invertebrates displaying similar toxicity distribution range between fish (0.48-121 mg/L and invertebrates (0.46-377 mg/L). The lower bioavailability of PET particles compared to smaller PVC polymers (circa 580 nm length) and DBP could be explained by its size, i.e. 2 µm diameter and form [

25]. In general, the pervasiveness of plastic materials in tissues is size dependent and contribute to its bioavailability. Surface modifications during weathering are also at play and involves their capacity to vector other contaminants in addition to plasticizers (DBP) [

26], a common property ascribed to nanomaterials [

27].

The increased activity of esterase by the ester DBP could be considered a biotransformation pathway leading to degradation and elimination of polar carboxylic compounds (phthalates). Similarly, bacteria biofilms (by inference in the host’s microbiome) forming on plastic compounds abound in

Pseudomonas sp. rich in esterase activity [

10]. The negative correlation between esterase and peroxidase activities suggests that oxidative stress is occurring during biodegradation as evidenced by higher esterase activity. This could explain why protein aggregation and carbonyls were increased and correlated with each other. This corroborates DBP’s ability to induce lipid peroxidation in other organism such as shrimps and mussels [

28,

29]. Plastic-based compounds could directly influence esterase activity of serum albumin [

30]. Serum albumin possesses esterase-like activity, which plays key role in metabolizing xenobiotics, was used as test surrogate to examine the effects of plastic nanoparticles. The study revealed that polystyrene nanoparticles produced conformational changes in albumin leading to esterase inhibition, which was inversely related to the size of the plastic materials. Esterase activity was inhibited by the nanoparticles as seen with PET microparticle in the present study. However, esterase activity was enhanced with smaller size polymers (PVC) producing more protein aggregation. Although PVC is not an ester, the presence of DBP embedded in PVC could contribute to esterase activity. This was supported by covariance analysis with exposure concentration of each plastic-related compound as the mean effect and DBP levels as covariable. The analysis showed no significant increase in esterase activity with PVC once the effect of DBP removed. Small plastic nanoparticles (25 nm diameter) were also shown to induce the accumulation of α-Synuclein aggregates (a marker of Parkinson’s disease) in both

C. elegans and human cells [

31] corroborating the observed presence of protein aggregates by small PVC polymers and hydrophobic DBP compared to larger PET particles in the present study. In caged mussels at sites under rainfall street runoffs and municipal effluent dispersion plume, protein aggregates and lipid peroxidation were elevated at plastic contaminated sites (rainfall overflows) and were significantly correlated with the reported levels of nanoplastics in tissues [

12]. Hence the toxicity of plastic materials will depend on the size distribution (breakdown products), presence of plastic additives (DBP) and their respective concentrations [

32]. They also find that the main driver of toxicity was an increase in oxygen species, lipid peroxidation (damage to cell membranes) and increased esterase activity. Esterase activity was significantly increased at 1 mg/L in algae after 72 h exposure. This highlights the complexity of plastic toxicity in aquatic environments.

In conclusion, this study show that PVC and PET materials in the 500-2000 nm range where bioavailable to freshwater quagga mussels at levels much lower than the apolar DBP, a component of plastic polymers. DBP was also found in mussels exposed to plastics and lead to decreased survival at DBP concentration of 70 ug/g tissues. DBP tissue levels also contributed to protein aggregation in addition to esterase activity as revealed by principal component analysis. Exposure of mussels to these compounds disrupted esterase activity leading to peroxidase changes and protein aggregation, a marker of amyloid formation leading to tissue degeneration. Because plastic materials come with its low molecular with components such as DBP and other apolar compounds, the observed toxicity responses with depend on the cumulative effects of these components. This study revealed that DBP could contribute to plastic toxicity associated with form and size although PVC and PET concentrations did not decrease survival. However, PVC and PET were able to influence stress biomarkers at concentrations of 5 µg/L corresponding to tissue levels of plastic in quagga mussels that could be found in biofilms and mussels in polluted urban environments [

12].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

References

- Avio, C.G. , Gorbi, S., Regoli, F., 2017. Plastics and microplastics in the oceans: from emerging pollutants to emerged threat. Mar. Environ. Res. 128, 2–11. [CrossRef]

- Plastic Europe, 2024. Fact sheet, Global and European plastics production and economic indicators. PE_TheFacts_25_digital-1pager-scrollable.

- Krikech, I. , Conti, G.O., Pulvirenti, E., Rapisarda, P., Castrogiovanni, M., Maisano, M., Ga¨el Le Pennec, D., Leermakers, M., Ferrante, M., Cappello, T., Ezziyyani, M., 2023. Microplastics (≤ 10 μm) bioaccumulation in marine sponges along the Moroccan Mediterranean coast: insights into species-specific distribution and potential bioindication. Environ. Res. 235, 116608. [CrossRef]

- Alberghini, L. , Truant, A., Santonicola, S., Colavita, G., Giaccone, V., 2022. Microplastics in fish and fishery products and risks for human health: a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 20, 789. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds A, Cody E, Giltrap M, Chambers G 2024. Toxicological and Biomarker Assessment of Freshwater Zebra Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) Exposed to Nano-Polystyrene. Toxics 12, 774. [CrossRef]

- Huffman Ringwood, A. , 2021. Bivalves as biological sieves: bioreactivity pathways of microplastics and nanoplastics. Biol. Bull. 241 (2), 185–195. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien RSM, DiRenzo GV, Roy AH, Carmignani J, Quinones RM, Rogers JB, Swartz BI. 2025. Catchment prioritization for freshwater mussel conservation in the Northeastern United States based on distribution modelling. PLoS One 20, e0324387.

- Geremia, E. , Muscari Tomajoli, M.T., Murano, C., Petito, A., Fasciolo, G., 2023. The impact of micro- and nanoplastics on aquatic organisms: mechanisms of oxidative stress and implications for human health. A review. Environments 10, 161. [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, G. , Capriello, T., Venditti, P., Fasciolo, G., La Pietra, A., Trifuoggi, M., Giarra, A., Agnisola, C., Ferrandino, I., 2023. Aluminum induces a stress response in zebrafish gills by influencing metabolic parameters, morphology, and redox homeostasis. Comp Biochem Phys. 271C, 109633. [CrossRef]

- Park WJ, Hwangbo M, Chu KH 2023. Plastisphere and microorganisms involved in polyurethane biodegradation. STOTEN 886, 163932.

- Gagné, F. , Roubeau-Dumont E. 2024. Relathionships Between Nanoplastic Contamination and Biochemical Properties of Biofilms in the Saint-Lawrence River. J Environ Toxicol Res 1, 9.

- Gagné F, Roubeau-Dumont E, André C, Auclair J 2023. Micro and Nanoplastic Contamination and Its Effects on Freshwater Mussels Caged in an Urban Area. J Xenobiot 13, 761-774. [CrossRef]

- Baroni A, Moulton C, Cristina M, Sansone L, Belli M, Tasciotti E. 2025. Nano- and Microplastics in the Brain: An Emerging Threat to Neural Health. Nanomaterials (Basel) 15, 1361.

- Bashirova N, Schölzel F, Hornig D, Scheidt HA, Krueger M, Salvan G, Huster D, Matysik J, Alia A. 2025. The Effect of Polyethylene Terephthalate Nanoplastics on Amyloid-beta Peptide Fibrillation. Molecules 30, 1432.

- Gagné F, Auclair J, Quinn B. 2019. Detection of polystyrene nanoplastics in biological samples based on the solvatochromic properties of Nile red: application in Hydra attenuata exposed to nanoplastics. Environ Sci Poll Res 26, 33524-33531.

- Yan, Y, Y. Qu, R. Du, and W. Zhou, Gao and R. Lu 2021. Colorimetric Assay Based on Arginine Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles for the Detection of Dibutyl Phthalate in Baijiu Samples.” Anal. Methods 13, 5179.

- Cabaleiro-Lago, C. Quinlan-Pluck, F. Lynch, I. Dawson, K.A. Linse, S. 2010. Dual effect of amino modified polystyrene nanoparticles on amyloid β protein fibrillation. ACS Chem. Neurosci.1, 279–287.

- Xing, Y. , Wang, S., Mao, X., Zhao, X., Wei, D 2020. An easy and efficient fluorescent method for detecting aldehydes and its application in biotransformation. J. Fluorescence 21, 587–594.

- Greenspan, P. , Mayer, E.P., Fowler, S.D. 1985. Nile red: A selective fluorescent stain for intracellular lipid droplets. J. Cell Biol. 100, 965–973.

- Neely, W.B. , Branson D.R., Blau G.E. 1974. Partition coefficient to measure bioconcentration potential of organic chemicals in fish. Environ. Science Techn. 8,1113-1115.

- Chatterjee S, Krolis E, Molenaar R, Claessens M. M.A.E., Blum C 2023. Nile red staining for nanoplastic quantification: overcoming the challenge of false positive counts due to fluorescent aggregates. Environ Chall 13, 100744.

- Prasad S, Bennett A, Triantafyllou M 2024. Characterization of nile red-stained microplastics through fluorescence spectroscopy. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 12, 1403. [CrossRef]

- Wang D, Jiang S.Y., Fan C., Fu L, Ruan H 2023. Occurrence and correlation of microplastics and dibutyl phthalate in rivers from Pearl River Delta, China. Marine Poll Bull 197, 115759.

- Mathieu-Denoncourt, J. , Langlois V.S., Wallace S.J., de Solla S.R. 2016. Influence of lipophilicity on the toxicity of bisphenol A and phthalates to aquatic organisms. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 97, 4–10.

- Piccardo M, Provenza F, Grazioli E, Cavallo A, Terlizzi A, Renzi M. 2020 PET microplastics toxicity on marine key species is influenced by pH, particle size and food variations Science of the Total Environment 715, 136947.

- Al-Emran M, Nayem MJ. 2025, Vector effects of microplastics on organic pollutants: sorption-desorption and bioaccumulation kinetics. Chemosphere 388, 144698.

- Gagné, F. , Gagnon C, Blaise C. 2007. Aquatic nanotoxicology: a review. Cur Top Toxicol 4, 51-64.

- Mensah PK, Griffin NJ, Mgaba N, Akwetey MFA, Odume ON 2025. Toxicity of commonly used plasticizers to the freshwater organisms Tilapia sparrmanii (Fish) and Caridina nilotica (Shrimp): lethal and sublethal effects. [CrossRef]

- Qin J-F, Chen H-G., Cai W-G., Yang T, Jia X-P. 2011. Effects of di-n-butyl phthalate on the antioxidant enzyme activities and lipid peroxidation level of Perna viridis. The J. Appl. Ecol. 22,1878-1884.

- Rajendran D, Chandrasekaran N 2023. Unveiling the modification of esterase-like activity of serum albumin by nanoplastics and their cocontaminants. ACS Omega 8, 43719-43731. [CrossRef]

- Jeong A, Park SJ, Lee EJ, Kim KW 2024. Nanoplastics exacerbate Parkinson’s disease symptoms in C. elegans and human cells. J Hazard Mater 465:133289. [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Castillo L, Blázquez-Blázquez E, Cerrada ML, Amariei G, Rosal R. 2025. Aquatic toxicity of UV-irradiated commercial polypropylene plastic particles and associated chemicals. J Hazard Mater. 494, 138645.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).