Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

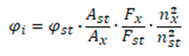

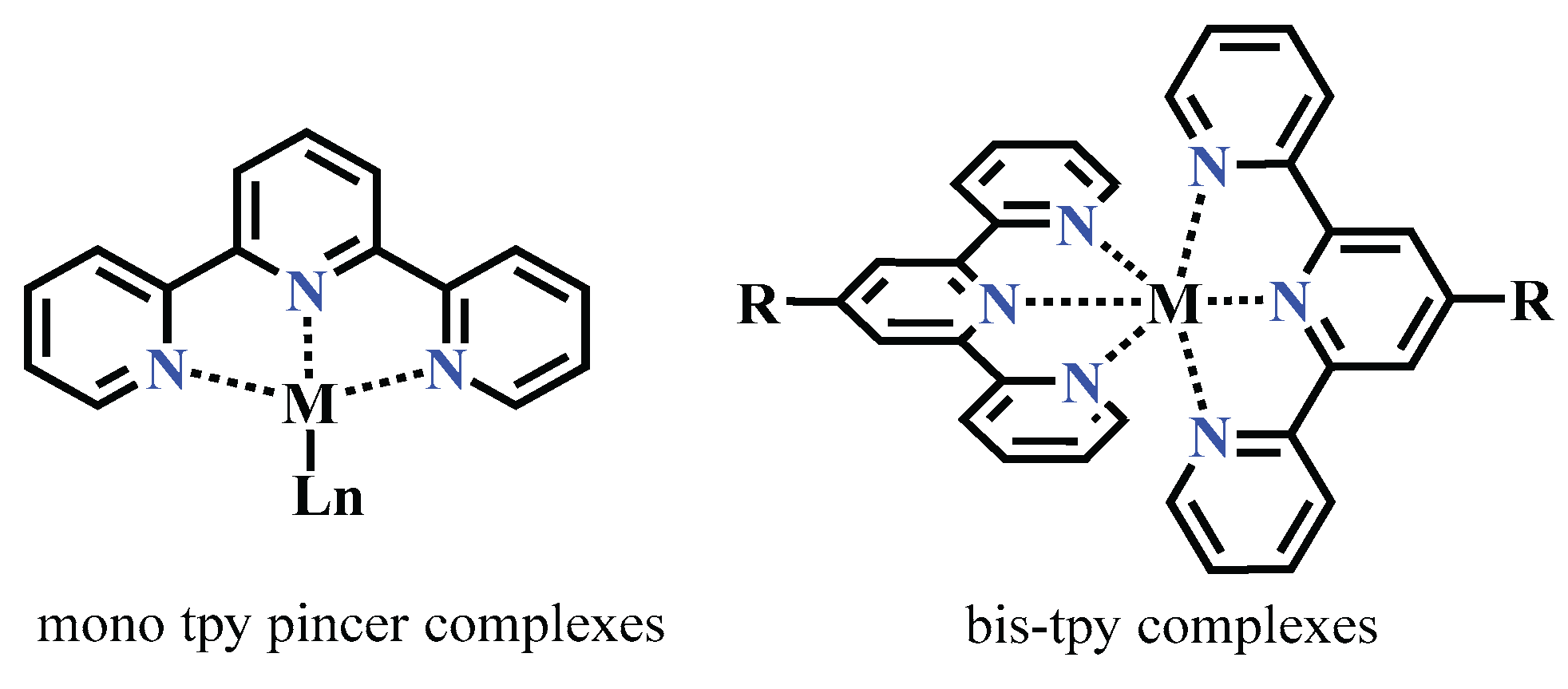

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material and Instrumentation

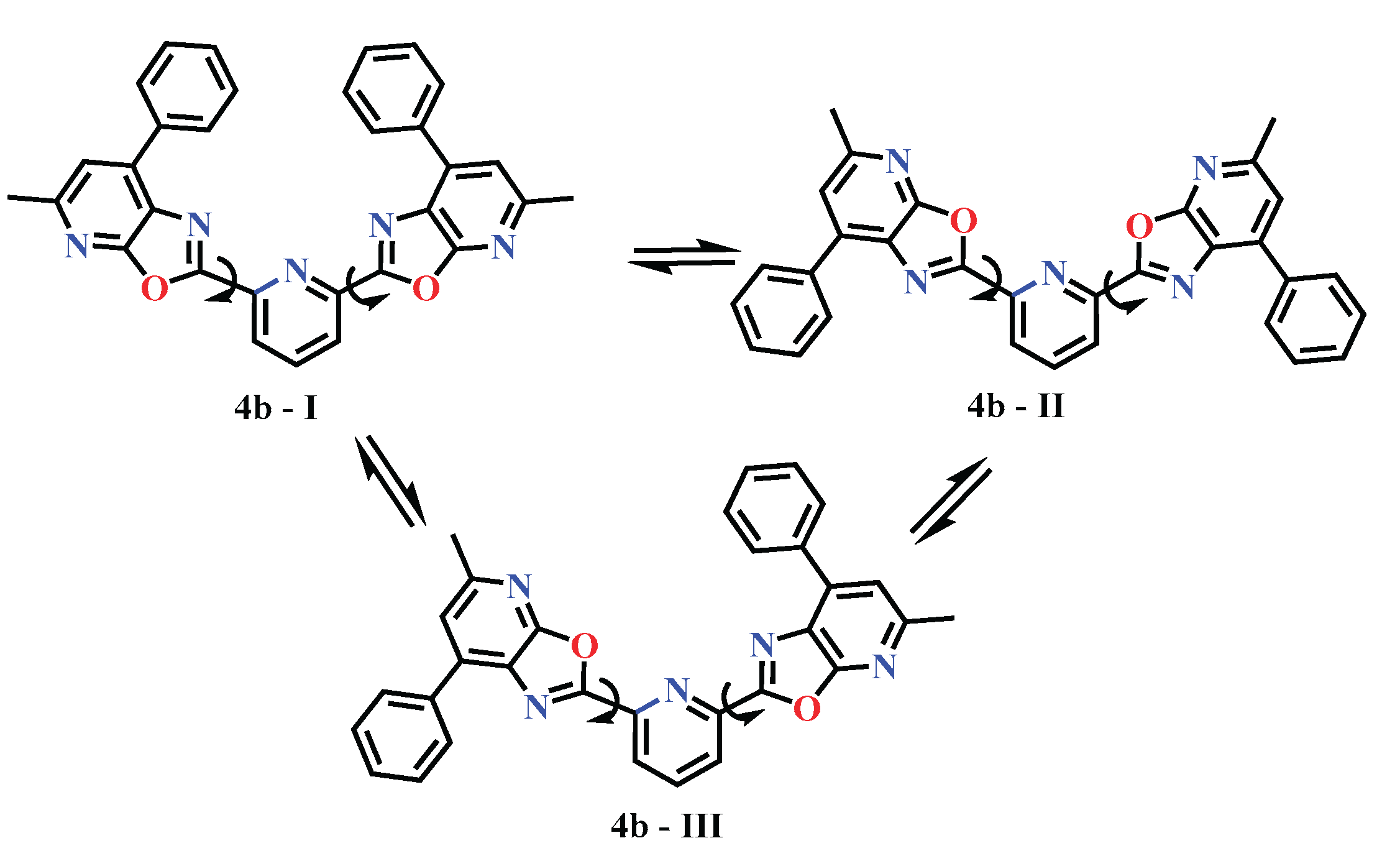

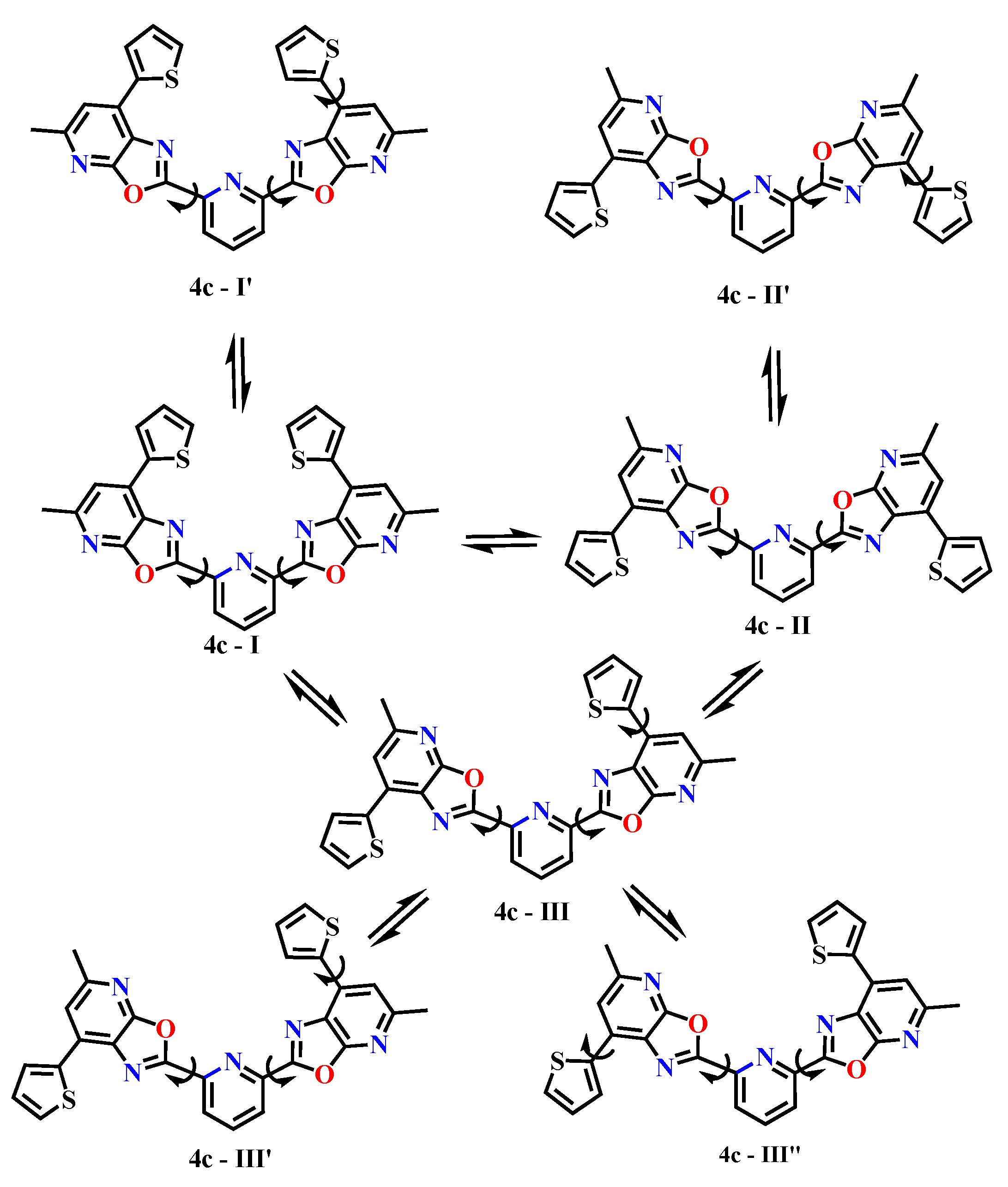

2.3. Conformational Analysis and Electronic Structure of the New 2,6-Bis(oxazolo[5,4-b]pyridin-2-yl)pyridines

2.4. DFT-Based Simulation of Electronic Absorption and Luminescence Properties

3. Results and Discussion

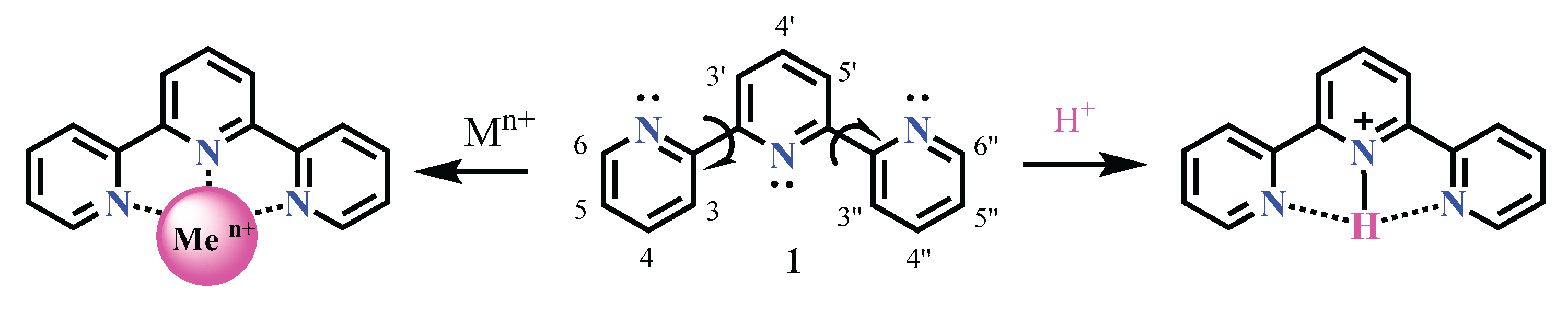

3.1. Chemistry

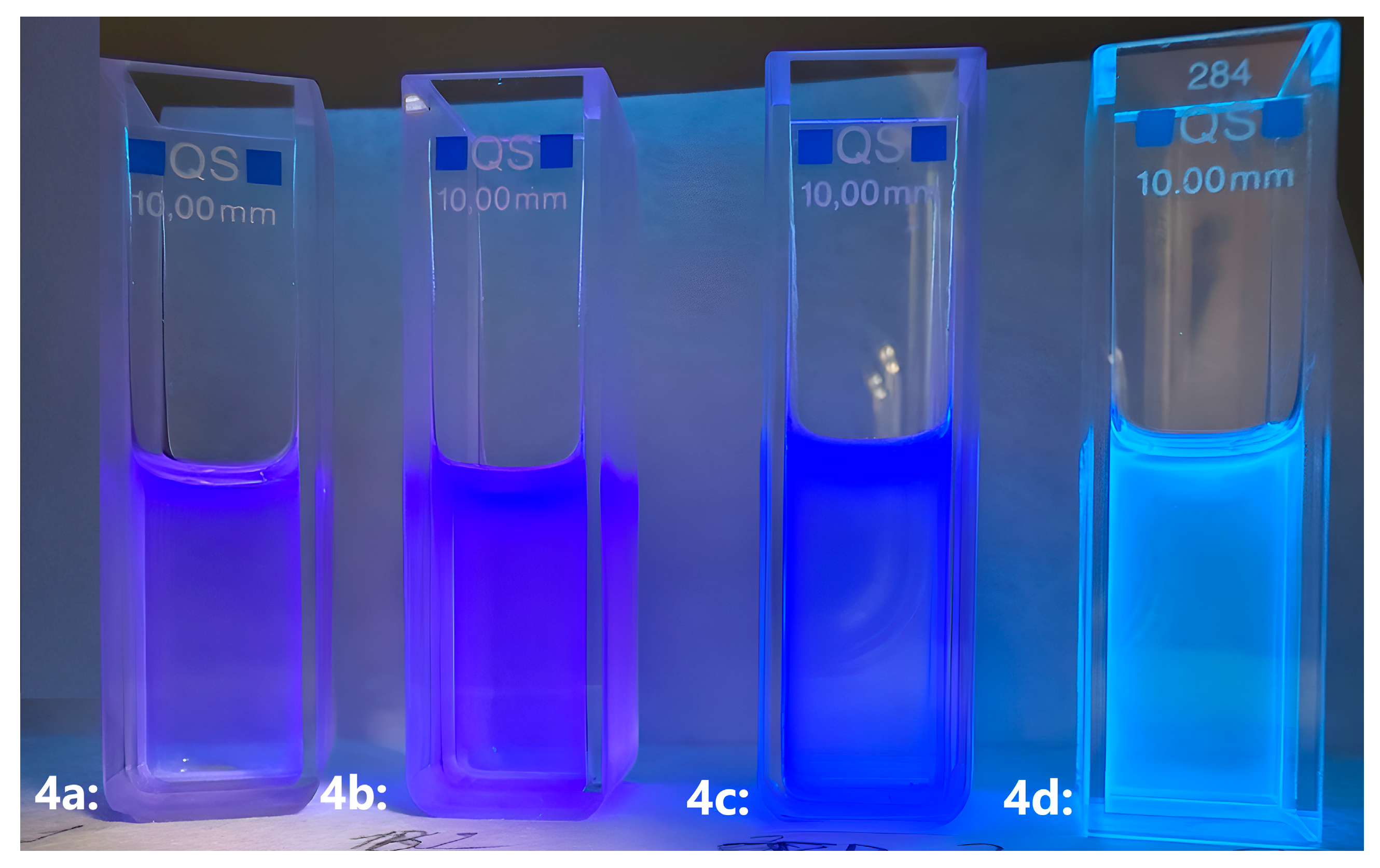

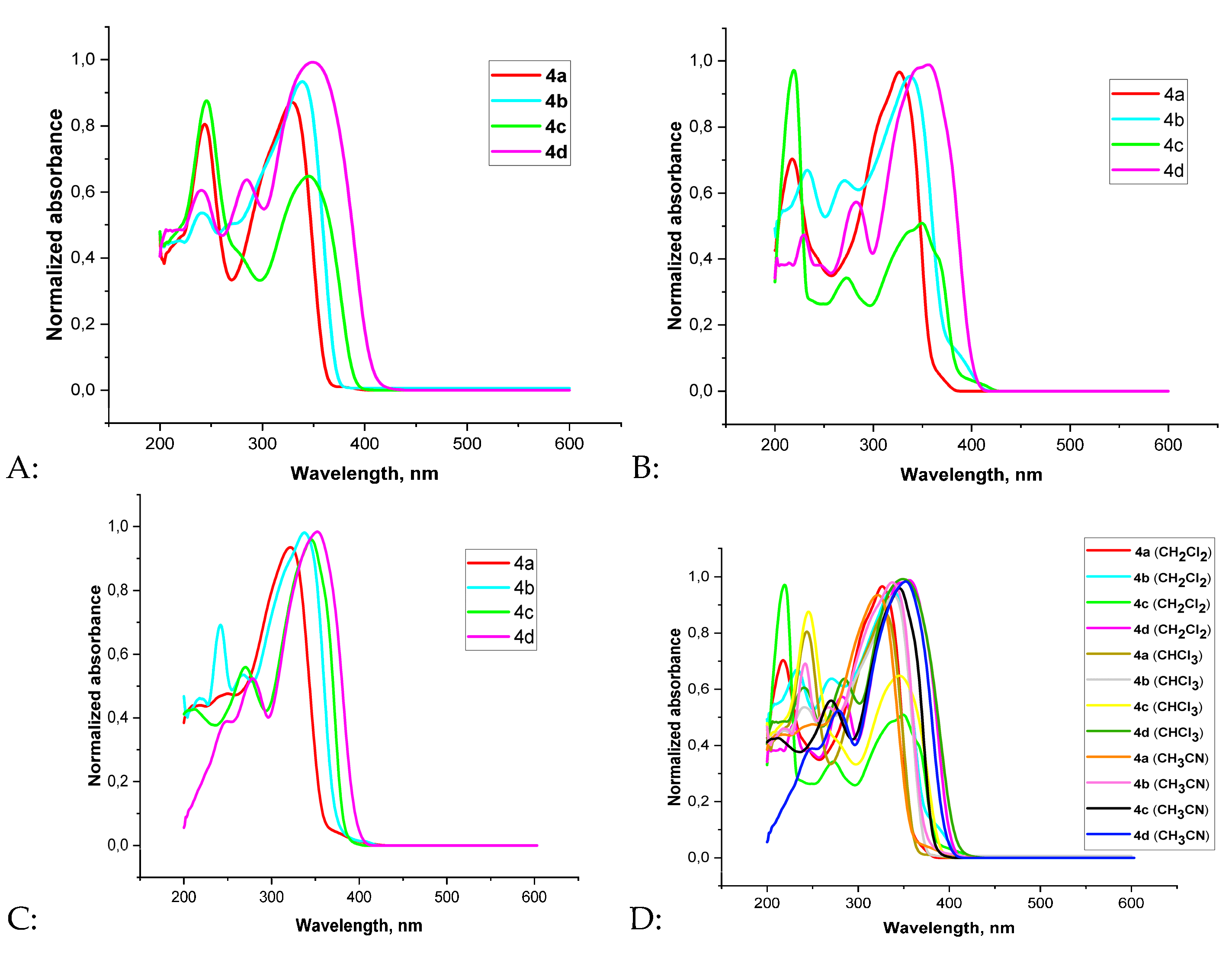

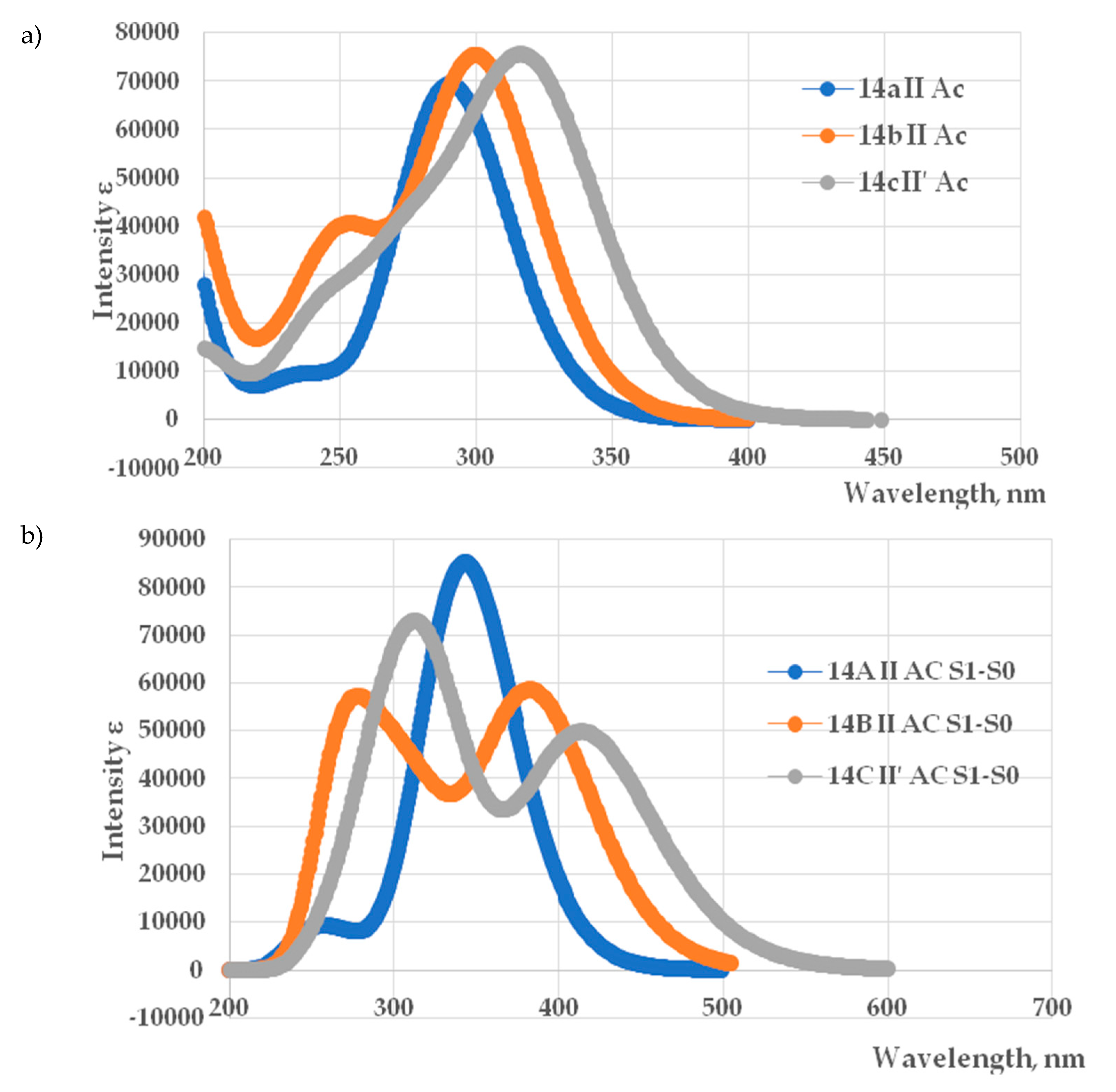

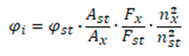

3.2. Photophysical Properties of Compounds

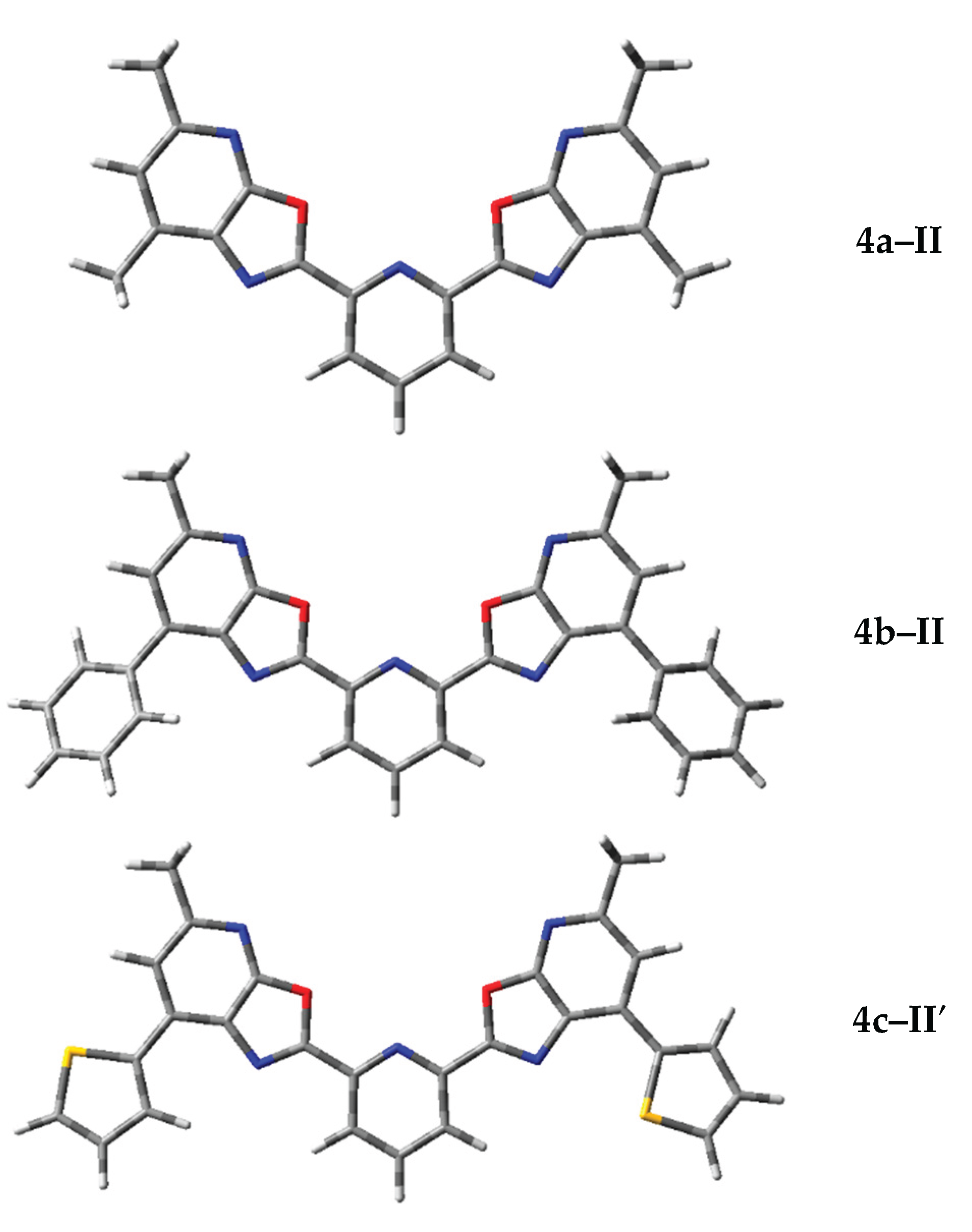

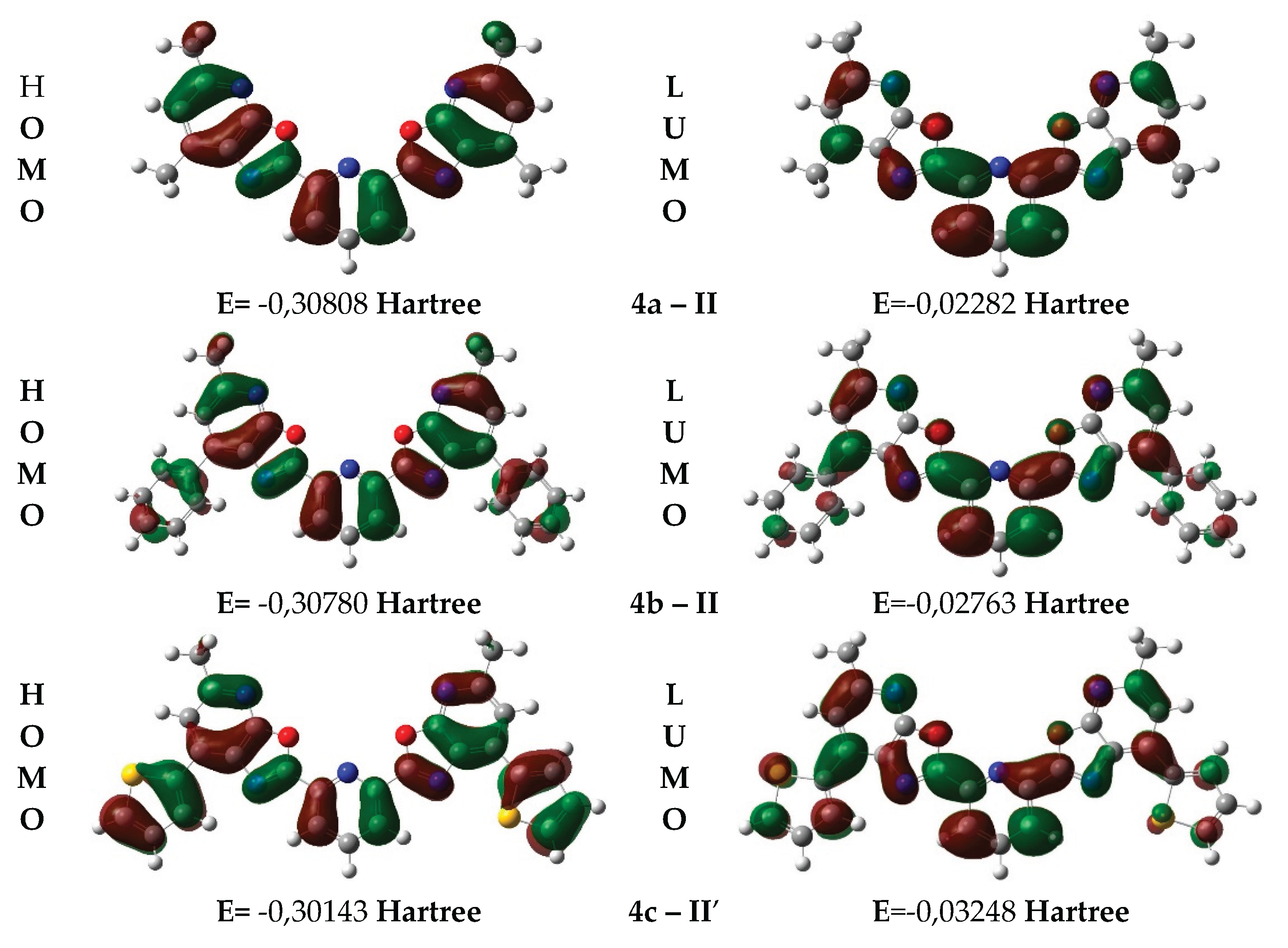

3.3. Conformational Analysis and Electronic Structure of the New 2,6-bis(oxazolo[5,4-b]pyridin-2-yl)pyridines

3.4. DFT-Based Simulation of Electronic Absorption and Luminescence Properties

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lavis, L.D.; Raines, R.T. Bright Ideas for Chemical Biology. ACS Chem. Biol. 2008, 3, 142.

- Que, E.L.; Domaille, D.W.; Chang, C.J. Metals in Neurobiology: Probing Their Chemistry and Biology with Molecular Imaging. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1517.

- Gonçalves, M.S.T. Fluorescent Labeling of Biomolecules with Organic Probes. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 190.

- Urano, Y.; Asanuma, D.; Hama, Y.; Koyama, Y.; Barrett, T.; Kamiya, M.; Nagano, T.; Watanabe, T.; Hasegawa, A.; Choyke, P.L. Selective Molecular Imaging of Viable Cancer Cells with pH-Activatable Fluorescence Probes. Nat. Med. 2008, 15, 104.

- Schäferling, M. The Art of Fluorescence Imaging with Chemical Sensors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3532.

- Köhler, A.; Wilson, J.S.; Friend, R.H. Fluorescence and Phosphorescence in Organic Materials. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2002, 4, 453.

- O’Regan, B.; Grätzel, M. A Low-Cost, High-Efficiency Solar Cell Based on Dye-Sensitized Colloidal TiO2 Films. Nature 1991, 353, 737.

- Hagfeldt, A.; Boschloo, G.; Sun, L.; Kloo, L.; Pettersson, H. Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 6595.

- Hartwig, J.F. Organotransition Metal Chemistry: From Bonding to Catalysis, University Science Books: Sausalito, CA, USA, 2010; 1128 pp.

- Liu, Z.; Sadler, P.J. Organoiridium complexes: anticancer agents and catalysts. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1174.

- Luca, O.R.; Crabtree, R.H. Redox-active ligands in catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 1440.

- Peris, E.; Crabtree, R.H. Recent homogeneous catalytic applications of chelate and pincer N-heterocyclic carbenes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004, 248, 2239.

- Vougioukalakis, G.C.; Grubbs, R.H. Ruthenium-based heterocyclic carbene-coordinated olefin metathesis catalysts. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1746.

- Chi, Y.; Chou, P.T. Transition-metal phosphors with cyclometalating ligands: fundamentals and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 638.

- Deiters, A.; Martin, S.F. Synthesis of oxygen-and nitrogen-containing heterocycles by ring-closing metathesis. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 2199.

- Fache, F.; Schulz, E.; Tommasino, M.L.; Lemaire, M. Nitrogen-containing ligands for asymmetric homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2000, 100, 2159.

- Wei, C.; He, Y.; Shi, X.; Song, Z. Terpyridine-metal complexes: Applications in catalysis and supramolecular chemistry. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 385, 1.

- Chelucci, G.; Thummel, R.P. Chiral 2,2‘-bipyridines, 1,10-phenanthrolines, and 2,2‘:6‘,2‘‘-terpyridines: Syntheses and applications in asymmetric homogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 3129.

- Winter, A.; Newkome, G.R.; Schubert U.S., Catalytic applications of terpyridines and their transition metal complexes. ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 1384.

- Shabunina, O.V.; Starnovskaya, E.S.; Shaitz, Ya.K.; Kopchuk, D.S.; Sadieva, L.K.; Kim, G.A.; Taniya, O.S.; Nikonov, I.L.; Santra, S.; Zyryanov, G.V.; Charushin, V.N. Asymmetrically substituted 5,5′′-diaryl-2,2′:6′,2′′-terpyridines as efficient fluorescence “turn-on” probes for Zn2+ in food/cosmetic samples and human urine. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 408, 113101.

- Armspach, D.; Constable, E.C.; Housecroft, C.E.; Neuburger, M.; Zehnder, M. Carbaborane-functionalised 2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine ligands for metallosupramolecular chemistry: Syntheses, complex formation, and the crystal and molecular structures of 4′-(ortho-carboranyl)-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine and 4′-(ortho-carboranylpropoxy)-2,2′:6′,2″-terpyridine. J. Organomet. Chem. 1998, 550, 193.

- Constable, E.C. 2,2′:6′,2″-Terpyridines: From chemical obscurity to common supramolecular motifs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007, 36, 246.

- Garcia-Dominguez, A.; Mueller, S.; Nevado, C.; Nickel-catalyzed intermolecular carbosulfonylation of alkynes via sulfonyl radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 9949.

- Hie, L.; Baker, E.L.; Anthony, S.M.; Desrosiers, J.N.; Senanayake, C.; Garg, N.K. Nickel-catalyzed esterification of aliphatic amides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15129.

- Huihui, K.M.M.; Shrestha, R.; Weixs, D.J. Nickel-catalyzed reductive conjugate addition of primary alkyl bromides to enones to form silyl enol ethers. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 340.

- Joshi-Pangu, A.; Ganesh, M.; Biscoe, M.R. Nickel-catalyzed Negishi cross-coupling reactions of secondary alkylzinc halides and aryl iodides. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1218.

- Kamata, K.; Suzuki, A.; Nakai, Y.; Nakazawa, H. Catalytic hydrosilylation of alkenes by iron complexes containing terpyridine derivatives as ancillary ligands. Organometallics 2012, 31, 3825.

- Tondreau, A.M.; Atienza, C.C.H.; Darmon, J.M.; Milsmann, C.; Hoyt, H.M.; Weller, K.J.; Nye, S.A.; Lewis, K.M.; Boyer, J.; Delis, J.G.P.; Lobkovsky, E.; Chirik, P.J. Synthesis, electronic structure, and alkene hydrosilylation activity of terpyridine and bis(imino)pyridine iron dialkyl complexes. Organometallics 2012, 31, 4886.

- Duong, H.A.; Wu, W.Q.; Teo, Y.Y. Cobalt-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of arylboronic esters and aryl halides. Organometallics 2017, 36, 4363.

- Kurahashi, T.; Matsubara, S. Nickel-catalyzed reactions directed toward the formation of heterocycles. Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1703.

- Kolesnichenko, I.V.; Anslyn, E.V. Practical applications of supramolecular chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 2385.

- Hwang, S.H.; Moorefield, C.N.; Fronczek, F.R.; Lukoyanova, O.; Echegoyen, L.; Newkome, G.R. Construction of triangular metallomacrocycles:[M 3 (1,2-bis(2,2′∶ 6′,2″-terpyridin-4-yl-ethynyl)benzene)3][M= Ru (ii), Fe (ii), 2Ru (ii) Fe (ii)]. Chem. Commun. 2005, 713.

- Sarkar, R.; Guo, K.; Moorefield, C.N.; Saunders, M.J.; Wesdemiotis, C.; Newkome, G.R. One-Step Multicomponent Self-Assembly of a First-Generation Sierpiński Triangle: From Fractal Design to Chemical Reality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 12182.

- Kulakov I.V.; Matsukevich M.V.; Shulgau Z.T.; Sergazy S.; Seilkhanov T.M.; Puzari A.; Fisyuk A.S. Synthesis and antiradical activity of 4-aryl(hetaryl)-substituted 3-aminopyridin-2(1H)-ones. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2015, 51, 991.

- Mohamed, A. A.; Nassr, A. A.; Sadeek, S. A.; Rashid, N. G.; Abd El-Hamid, S. M. First Report on Several NO-Donor Sets and Bidentate Schiff Base and Its Metal Complexes: Characterization and Antimicrobial Investigation. Compounds 2023, 3 (3), 376–389.

- Moiseev, R. V.; Morrison, P. W. J.; Steele, F.; Khutoryanskiy, V. V. Penetration Enhancers in Ocular Drug Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11 (7), 321.

- Shatsauskas, A.L.; Abramov, A.A.; Chernenko, S.A.; Kostyuchenko, A.S.; Fisyuk, A.S. Synthesis and Photophysical Properties of 3-Amino-4-arylpyridin-2 (1Н)-ones. Synthesis 2020, 52, 227.

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10 (44), 6615.

- Krishnan, R.; Binkley, J. S.; Seeger, R.; Pople, J. A. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980, 72 (1), 650–654.

- Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G. A.; Nakatsuji, H.; Li, X.; Caricato, M.; Marenich, A. V.; Bloino, J.; Janesko, B. G.; Gomperts, R.; Mennucci, B.; Hratchian, H. P.; Ortiz, J. V.; Izmaylov, A. F.; Sonnenberg, J. L.; Williams-Young, D.; Ding, F.; Lipparini, F.; Egidi, F.; Goings, J.; Peng, B.; Petrone, A.; Henderson, T.; Ranasinghe, D.; Zakrzewski, V. G.; Gao, J.; Rega, N.; Zheng, G.; Liang, W.; Hada, M.; Ehara, M.; Toyota, K.; Fukuda, R.; Hasegawa, J.; Ishida, M.; Nakajima, T.; Honda, Y.; Kitao, O.; Nakai, H.; Vreven, T.; Throssell, K.; Montgomery, J. A., Jr.; Peralta, J. E.; Ogliaro, F.; Bearpark, M. J.; Heyd, J. J.; Brothers, E. N.; Kudin, K. N.; Staroverov, V. N.; Keith, T. A.; Kobayashi, R.; Normand, J.; Raghavachari, K.; Rendell, A. P.; Burant, J. C.; Iyengar, S. S.; Tomasi, J.; Cossi, M.; Millam, J. M.; Klene, M.; Adamo, C.; Cammi, R.; Ochterski, J. W.; Martin, R. L.; Morokuma, K.; Farkas, O.; Foresman, J. B.; Fox, D. J. Gaussian 16, Revision A.03; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford CT, 2016.

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.; Millam, J. GaussView, Version 6; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, 2016. Available online: http://gaussian.com.

- Huber, R. G.; Margreiter, M. A.; Fuchs, J. E.; von Grafenstein, S.; Tautermann, C. S.; Liedl, K. R.; Fox, T. Heteroaromatic π-Stacking Energy Landscapes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2014, 54 (5), 1371–1379.

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M. Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102 (11), 1995–2001.

- Hehre, W. J.; Radom, L.; Schleyer, P. v. R.; Pople, J. A. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory; Wiley: New York, 1986; pp 235–240.

- Young, D. C. Computational Chemistry: A Practical Guide for Applying Techniques to Real-World Problems; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 2001; pp 104–110.

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M. Quantum Calculation of Molecular Energies and Energy Gradients in Solution by a Conductor Solvent Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102 (11), 1995–2001.

- Rakhimzhanova, A. S.; Muzaparov, R. A.; Pustolaikina, I. A.; Kurmanova, A. F.; Nikolskiy, S. N.; Kapishnikova, D. D.; Stalinskaya, A. L.; Kulakov, I. V. Series of Novel Integrastatins Analogues: In Silico Study of Physicochemical and Bioactivity Parameters. Eurasian J. Chem. 2024, 29 (4 (116)), 44–60.

- Stratmann, R. E.; Scuseria, G. E.; Frisch, M. J. An efficient implementation of time-dependent density-functional theory for the calculation of excitation energies of large molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1998, 109 (19), 8218–8224.

- Shatsauskas, A.L.; Shatalin, Y.V.; Shubina, V.S.; Chernenko, S.A.; Kostyuchenko, A.S.; Fisyuk, A.S.5-Ethyl-5,6-dihydrobenzo[c][1,7]naphthyridin-4(3H)-ones – A new class of fluorescent dyes. Dyes and Pigments 2022, 204, 110388.

- Shatsauskas, A.; Shatalin, Yu.; Shubina, V.; Zablodtskii, Yu.; Chernenko, S.; Samsonenko, A.; Kostyuchenko, A.; Fisyuk, A. Synthesis and application of new 3-amino-2-pyridone based luminescent dyes for ELISA. Dyes and Pigments 2021, 187, 109072.

- Åberg, V.; Sellstedt, M.; Hedenström, M.; Pinkner, J. S.; Hultgren, S. Design, synthesis and evaluation of peptidomimetics based on substituted bicyclic 2-pyridones—Targeting virulence of uropathogenic E. coli. J. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 7563.

- Verissimo, E.; Berry, N.; Gibbons, P.; Cristiano, M. L. S.; Rosenthal, P. J.; Gut, J.; Ward, S. A.; O’Neill, P. M. Design and synthesis of novel 2-pyridone peptidomimetic falcipain 2/3 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 4210.

- Zhu, S.; Hudson, T.H.; Kyle, D.E.; Lin, A.J. Synthesis and in vitro studies of novel pyrimidinyl peptidomimetics as potential antimalarial therapeutic agents. J. Med. Chem., 2002, 45, 3491.

- Palamarchuk, I.V.; Shulgau, Z.T.; Kharitonova, M.A.; Kulakov, I.V. Synthesis and neurotropic activity of new 3-(arylmethyl)aminopyridine-2(1H)-one. Chem. Pap. 2021, 75, 4729.

- Kulakov, I.V.; Shatsauskas, A.L.; Matsukevich, M.V.; Palamarchuk, I.V.; Seilkhanov, T.M.; Gatilov, Yu.V.; Fisyuk, A.S. A New Approach to the Synthesis of Benzo[c][1,7] naphthyridin-4(3H)-ones. Synthesis 2017, 49, 3700.

- Kulakov, I.V.; Matsukevich, M.V.; Levin, M.L.; Palamarchuk, I.V.; Seilkhanov, T.M.; Fisyuk, A.S. Synthesis of the First Representatives of Thieno[3,2-c][1,7]naphthyridine Derivatives Based on 3-Amino-6-methyl-4-(2-thienyl)pyridin-2(1H)-one. Synlett 2018, 29, 1741.

- Palamarchuk, I.V.; Matsukevich, M.V.; Kulakov, I.V.; Seilkhanov, T.M.; Fisyuk, A.S. Synthesis of N-substituted 2-aminomethyl-5-methyl-7-phenyloxazolo[5,4-b]pyridines. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2019, 55, 788.

- Shatsauskas, A.L.; Abramov, A.A.; Saibulina, E.R.; Palamarchuk, I.V.; Kulakov, I.V.; Fisyuk, A.S. Synthesis of 3-amino-6-methyl-4-phenylpyridin-2(1H)-one and its derivatives. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2017, 53, 186.

- Palamarchuk, I.V.; Kulakov, I.V. A New Method for Obtaining Carboxylic Derivatives of Oxazolo[5,4-b]pyridine Based on 3-Aminopyridine-2(1H)-ones. Eurasian J. Chem. 2024, 29, 32.

- Laurent, A. D.; Jacquemin, D. TD-DFT Benchmarks: A Review. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2013, 113 (17), 2019–2039.

- Casida, M. E. Time-Dependent Density-Functional Theory for Molecules and Molecular Solids. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM 2009, 914 (1–3), 3–18.

| Compound | UV–Vis | ||||||||

| λabsmax, [nm] | ε, [l/cm*mol] | ||||||||

| CHCl3 | CH2Cl2 | CH3CN | CHCl3 | CH2Cl2 | CH3CN | ||||

| 4а | 329 | 327 | 323 | 4200 | 3750 | 4950 | |||

| 4b | 338 | 337 | 336 | 5100 | 5000 | 7500 | |||

| 4c | 351 | 350 | 347 | 5000 | 4500 | 11150 | |||

| 4d | 343 | 357 | 354 | 4700 | 4100 | 4450 | |||

| Compound | Photoluminescence | ||||||||

| λemmax [nm] | Stokes shift, [nm] | Quantum yield (Φfl)а | |||||||

| CHCl3 | CH2Cl2 | CH3CN | CHCl3 | CH2Cl2 | CH3CN | CHCl3 | CH2Cl2 | CH3CN | |

| 4а | 358; 372 | 357, 372 | 368 | 43 | 45 | 45 | 0.50 | 0.84 | 0.71 |

| 4b | 368; 386 | 367; 384 | 365; 382 | 48 | 47 | 46 | 0.63 | 0.63 | 0.44 |

| 4c | 391; 414 | 415 | 431 | 63 | 65 | 84 | 0.40 | 0.38 | 0.32 |

| 4d | 444 | 454 | 474 | 105 | 97 | 120 | 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.74 |

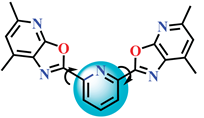

| No | Structural formula | IUPAC name |

| 4а |  |

2,6-bis(5,7-dimethyloxazolo[5,4-b]pyridin-2-yl)pyridine |

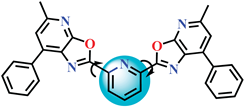

| 4b |  |

2,6-bis(5-methyl-7-phenyloxazolo[5,4-b]pyridin-2-yl)pyridine |

| 4c |  |

2,6-bis(5-methyl-7-(thiophen-2-yl)oxazolo[5,4-b]pyridin-2-yl)pyridine |

| No |

Confor- mation |

Etotal, Hartree | G, Hartree | ||||

| vacuum | CH2Cl2 | CH3CN | vacuum | CH2Cl2 | CH3CN | ||

| Compound 4a | |||||||

| 1. | 4а - I | -1234.601128 | -1234.619395 | -1234.621546 | -1234.312490 | -1234.329376 | -1234.331575 |

| 2. | 4а - II | -1234.605119 | -1234.621583 | -1234.623556 | -1234.313758 | -1234.330327 | -1234.332393 |

| 3. | 4а - III | -1234.603304 | -1234.620573 | -1234.622619 | -1234.313169 | -1234.329507 | -1234.331598 |

| Compound 4b | |||||||

| 4. | 4b - I | -1618.025748 | -1618.047279 | -1618.049795 | -1617.631494 | -1617.656502 | -1617.658902 |

| 5. | 4b - II | -1618.029901 | -1618.048890 | -1618.051111 | -1617.638304 | -1617.657294 | -1617.659742 |

| 6. | 4b - III | -1618.028236 | -1618.047834 | -1618.050160 | -1617.637415 | -1617.656927 | -1617.659101 |

| Compound 4c | |||||||

| 7. | 4c - I | -2259.571275 | -2259.592992 | -2259.595664 | -2259.248044 | -2259.269901 | -2259.269709 |

| 8. | 4c - I’ | -2259.572917 | -2259.592245 | -2259.596036 | -2259.247327 | -2259.269201 | -2259.273103 |

| 9. | 4c – II | -2259.575259 | -2259.594544 | -2259.596348 | -2259.251650 | -2259.271053 | -2259.272130 |

| 10. | 4c - II’ | -2259.576532 | -2259.595037 | -2259.597195 | -2259.253505 | -2259.271921 | -2259.274708 |

| 11. | 4c - III | -2259.573293 | -2259.593485 | -2259.595891 | -2259.250371 | -2259.270751 | -2259.273289 |

| 12. | 4c - III’ | -2259.575792 | -2259.594097 | -2259.596231 | -2259.252692 | -2259.271836 | -2259.274293 |

| 13. | 4c - III’’ | -2259.574576 | -2259.593995 | -2259.596304 | -2259.252483 | -2259.271385 | -2259.274164 |

| Conformation | E(HOMO), Hartree | E(LUMO), Hartree | ДE (LUMO–HOMO), Hartree | ДE (LUMO–HOMO), eV |

| 4a–II | –0.3080 | -0.02282 | 0.28526 | 7.76 |

| 4b–II | -0.30780 | -0.02763 | 0.28017 | 7.63 |

| 4c–II′ | -0.30143 | -0.03248 | 0.26895 | 7.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).