Submitted:

03 December 2025

Posted:

05 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Fe3O4 Nanoparticles

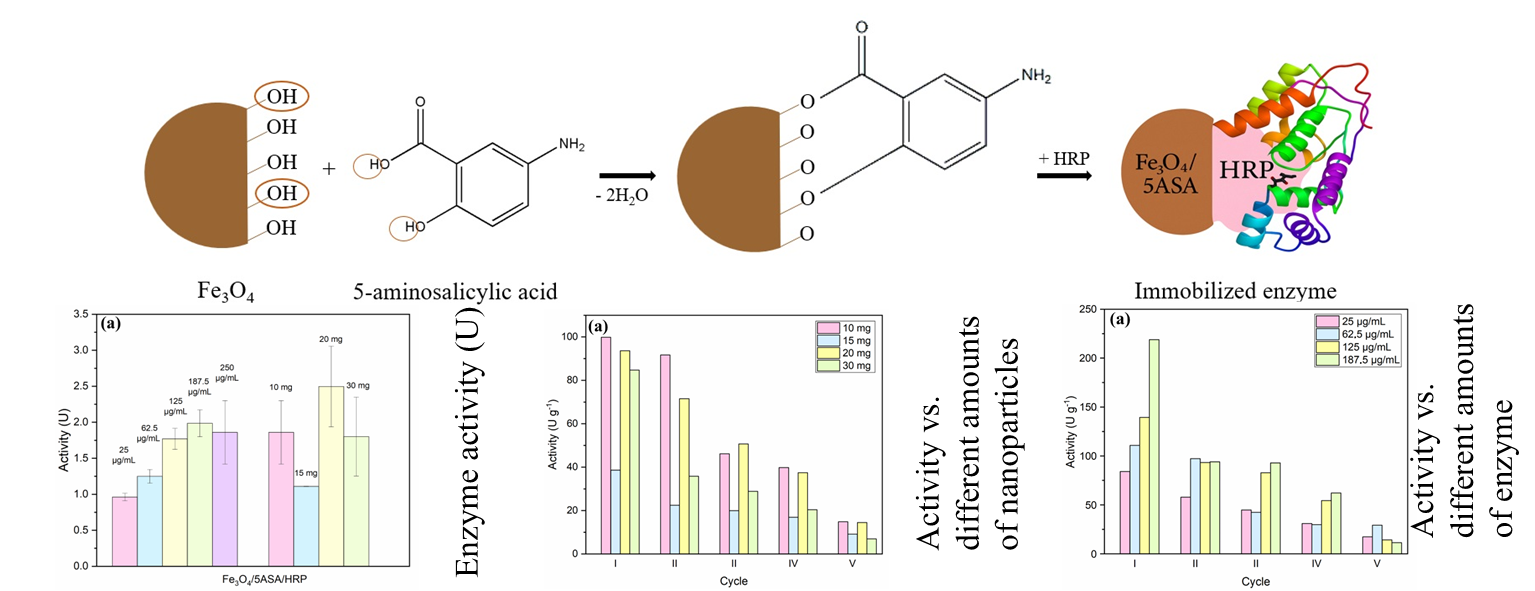

2.2. Immobilization of HRP to Fe3O4/5ASA and Fe3O4/CA Nanocomposite Materials

2.3. Activity of HRP Immobilized to Fe3O4/5ASA and Fe3O4/CA Nanocomposite Materials

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis of Magnetic Nanoparticles

3.2. Preparation of Fe3O4 with 5-Aminosalicylic and Caffeic Acid

3.3. Nanoparticle Activation and HRP Immobilization

3.4. Determination of Protein Concentration Using the Bradford Method

3.5. Determination of Enzyme Activity

3.6. Characterization of Fe3O4 Nanomaterials

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lazić, V.; Nedeljković, J.M. Photocatalytic Reactions over TiO2-Based Interfacial Charge Transfer Complexes. Catalysts 2024, 14, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, J.; Kato, S.; Hanaya, M.J. Interfacial Charge-Transfer Transitions between ZnO Nanoparticles and Aliphatic Thiols. J. Phys. Chem. C 2023, 127, 15300–15306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, J.-I.; Kato, S.; Hanaya, M. Substituent effects on interfacial charge-transfer transitions in a TiO2-phenol complex. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2023, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, V.; Nedeljković, J.M. Nanomaterials Synthesis: Design, Fabrication and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 419–449. [Google Scholar]

- Sredojević, D.; Stavrić, S.; Lazić, V.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Nedeljković, J.M. Interfacial charge transfer complex formation between silver nanoparticles and aromatic amino acids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 16493–16500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smičiklas, I.; Papan, J.; Lazić, V.; Lončarević, D.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Nedeljković, J.M. Functionalized biogenic hydroxyapatite with 5-aminosalicylic acid – Sorbent for efficient separation of Pb2+ and Cu2+ ions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 3759–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, V.; Mihajlovski, K.; Mraković, A.; Illés, E.; Stoiljković, M.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Nedeljković, J.M. Antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles supported by magnetite. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 4018–4024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, V.; Smičiklas, I.; Marković, J.; Lončarević, D.; Dostanić, J.; Ahrenkiel, S.P.; Nedeljković, J.M. Antibacterial ability of supported silver nanoparticles by functionalized hydroxyapatite with 5-aminosalicylic acid. Vacuum 2018, 148, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikšić, V.; Pirković, A.; Spremo-Potparević, B.; Živković, L.; Topalović, D.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Lazić, V. Bioactivity Assessment of Functionalized TiO2 Powder with Dihydroquercetin. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarubica, A.; Sredojević, D.; Ljupković, R.; Randjelović, M.; Murafa, N.; Stoiljković, M.; Lazić, V.; Nedeljković, J.M. Photocatalytic ability of visible-light-responsive hybrid ZrO2 particles. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2023, 7, 2279–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sredojević, D.; Lazić, V.; Pirković, A.; Periša, J.; Murafa, N.; Spremo-Potparević, B.; Živković, L.; Topalović, D.; Zarubica, A.; Krivokuća, M.J.; et al. Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles Supported by Surface-Modified Zirconium Dioxide with Dihydroquercetin. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljković, M.G.; Lazić, V.; Banjanac, K.; Davidović, S.Z.; Bezbradica, D.I.; Marinković, A.D.; Sredojević, D.; Nedeljković, J.M.; Branković, S.I.D. Immobilization of dextransucrase on functionalized TiO2 supports. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 114, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieriková, Z.; Šimunková, M.; Brezová, V.; Sredojević, D.; Lazić, V.; Lončarević, D.; Nedeljković, J.M. Interfacial charge transfer complex between TiO2 and non-aromatic ligand squaric acid. Opt. Mater. 2022, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Mageed, H.M. Frontiers in nanoparticles redefining enzyme immobilization: A review addressing challenges, innovations, and unlocking sustainable future potentials. Micro Nano Syst. Lett. 2025, 13, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Luo, P.; Han, J.; Chen, T.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Liu, Q. Horseradish peroxidase immobilized on the magnetic composite microspheres for high catalytic ability and operational stability. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2019, 122, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulaal, W.H.; Almulaiky, Y.Q.; El-Shishtawy, R.M. Encapsulation of HRP Enzyme onto a Magnetic Fe3O4 Np–PMMA Film via Casting with Sustainable Biocatalytic Activity. Catalysts 2020, 10, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Zhai, Q.; Hu, M.; Li, S.; Jiang, Y. Hierarchically porous magnetic Fe 3 O 4/Fe-MOF used as an effective platform for enzyme immobilization: A kinetic and thermodynamic study of structure–activity. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2021, 11, 2446–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Q.; Tang, H. Immobilization of horseradish peroxidase on NH2-modified magnetic Fe3O4/SiO2 particles and its application in removal of 2, 4-dichlorophenol. Molecules 2014, 19, 15768–15782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.A.; Al-Harbi, M.H.; Almulaiky, Y.Q.; Ibrahim, I.H.; El-Shishtawy, R.M. Immobilization of horseradish peroxidase on Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 27, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Sheng, J.; Si, G.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Gu, N. Spy chemistry enables stable protein immobilization on iron oxide nanoparticles with enhanced magnetic properties. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 161, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladole, M.R.; Mevada, J.S.; Pandit, A.B. Ultrasonic hyperactivation of cellulase immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonović, M.; Jugović, B.; Žuža, M.; Đorđević, V.; Milašinović, N.; Bugarski, B.; Knežević-Jugović, Z. Immobilization of Horseradish Peroxidase on Magnetite-Alginate Beads to Enable Effective Strong Binding and Enzyme Recycling during Anthraquinone Dyes’ Degradation. Polymers 2022, 14, 2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gama Cavalcante, A.L.; Dari, D.N.; Izaias da Silva Aires, F.; Carlos de Castro, E.; Moreira dos Santos, K.; Sousa dos Santos, J.C. Advancements in enzyme immobilization on magnetic nanomaterials: Toward sustainable industrial applications. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 17946–17988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro-Hinojosa, C.; Del Sol-Fernández, S.; Moreno-Antolín, E.; Martín-Gracia, B.; Ovejero, J.G.; de la Fuente, J.M.; Grazú, V.; Fratila, R.M.; Moros, M. A Simple and Versatile Strategy for Oriented Immobilization of His-Tagged Proteins on Magnetic Nanoparticles. Bioconjugate Chem. 2023, 34, 2275–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almulaiky, Y.Q.; Alkabli, J.; El-Shishtawy, R.M. Improving enzyme immobilization: A new carrier-based magnetic polymer for enhanced covalent binding of laccase enzyme. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, B.; Beeran, A.E.; Jayaram, P.S.; Prakash, P.; Jayasree, R.S.; Thomas, S.; Chakrapani, B.; Anantharaman, M.R.; Bushiri, M.J. Radio frequency plasma assisted surface modification of Fe3O4 nanoparticles using polyaniline/polypyrrole for bioimaging and magnetic hyperthermia applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2021, 32, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, J.; Xing, M.; Beatty, J.; Elkins, J.; Seda, T.; Mishra, S.R.; Liu, J.P. Enhancing the magnetic and inductive heating properties of Fe3O4 nanoparticles via morphology control. Nanotechnology 2020, 31, 275706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heryanto, H.; Tahir, D. The correlations between structural and optical properties of magnetite nanoparticles synthesised from natural iron sand. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 16820–16827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaki, S.H.; Malek, T.J.; Chaudhary, M.D.; Tailor, J.P.; Deshpande, M.P. Magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesis by wet chemical reduction and their characterization. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaki, S.H.; Malek, T.J.; Chaudhary, M.D.; Tailor, J.P.; Deshpande, M.P. Magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesis by wet chemical reduction and their characterization. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 035009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes-Neto, J.G.; Silva, T.R.F.; Ribeiro, F.O.S.; Silva, D.A.; Soares, M.F.R.; Soares-Sobrinho, J.L. Reconstitution as an alternative method for 5-aminosalicylic acid intercalation in layered double hydroxide for drug delivery. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2021, 147, 3141–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vertuccio, L.; Guadagno, L.; D’angelo, A.; Viola, V.; Raimondo, M.; Catauro, M. Sol-Gel Synthesis of Caffeic Acid Entrapped in Silica/Polyethylene Glycol Based Organic-Inorganic Hybrids: Drug Delivery and Biological Properties. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Sheng, J.; Si, G.; Li, Y.; Shen, Y.; Gu, N. Spy chemistry enables stable protein immobilization on iron oxide nanoparticles with enhanced magnetic properties. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 161, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehm, F.B.H.; Chen, S.; Rehm, B.H.A. Bioengineering toward direct production of immobilized enzymes: A paradigm shift in biocatalyst design. Bioengineered 2017, 9, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-C.; Do, J.-S.; Gu, Y. Immobilization of HRP in Mesoporous Silica and Its Application for the Construction of Polyaniline Modified Hydrogen Peroxide Biosensor. Sensors 2009, 9, 4635–4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, L.; Zhang, M.; Guo, W.; Cai, Z.; Wang, D.; Yang, W.; Chen, Y. Enhanced Activity of Immobilized Horseradish Peroxidase by Carbon Nanospheres for Phenols Removal. CLEAN – Soil, Air, Water 2016, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, B.; Akbulut, M.; Ulusal, F.; Ulu, A.; Özdemir, N.; Ateş, B. Horseradish Peroxidase Immobilized onto Mesoporous Magnetic Hybrid Nanoflowers for Enzymatic Decolorization of Textile Dyes: A Highly Robust Bioreactor and Boosted Enzyme Stability. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 24558–24573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Zhou, Z.; Wang, Y.; Han, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Ni, L. Immobilization of horseradish peroxidase on multi-armed magnetic graphene oxide composite: Improvement of loading amount and catalytic activity. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2019, 57, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salah, H.A.; Elsayed, A.M.; Abdel-Aty, A.M.; Khater, G.A.; El-Kheshen, A.A.; Farag, M.M.; Mohamed, S.A. Biochemical properties of immobilized horseradish peroxidase on ceramic and its application in removal of azo dye. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Nahass, M.N.; El-Keiy, M.M.; Ali, E.M. Immobilization of horseradish peroxidase into cubic mesoporous silicate, SBA-16 with high activity and enhanced stability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 116, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).