1. Introduction

Traditional Systems Engineering (SE) relies on a document-centric approach in which engineering knowledge is captured and exchanged through text documents, spreadsheets, and informal communication channels. While document-centric approaches may work for small and simple systems, they become less effective as system size and complexity increase, often resulting in fragmented information, inconsistencies, and difficulties in maintaining traceability across multiple disciplines. [

1]

In parallel, the nature of engineered systems has evolved significantly. Modern products are increasingly developed as Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS), which tightly integrate software, electronics, and mechanical components into interconnected systems [

2]. The development process of CPS is characterized by a rapidly growing functional scope, distributed development teams, and stricter requirements. These characteristics increase system complexity and place high demands on coordination and information management.

Model-based Systems Engineering (MBSE) has emerged as a response to these challenges. In contrast to document-centric SE, MBSE establishes centralized system models as the authoritative sources of information [

3]. Literature highlights several potential advantages of MBSE, including improved traceability, automated consistency checks, and enhanced collaboration across disciplines [

3]. However, although many studies report perceived benefits of MBSE, only a small fraction have empirically measured these improvements [

4].

Additionally, the adoption of MBSE faces challenges during both its introduction and operational use. In the introduction phase, barriers include the high initial modeling effort, steep learning curves, and limited management commitment. In the operational use phase, challenges arise from managing model complexity and retrieving relevant information from large and continuously growing system models. [

5,

6]

Advances in Artificial Intelligence (AI), particularly in Generative AI such as Large Language Models (LLMs), offer promising opportunities to enhance human interaction with system models through natural language. This potential is further amplified by the introduction of the System Modeling Language V2 (SysMLv2), the successor to the widely adopted system modeling language SysML. A key advantage of SysMLv2 lies in its support for textual representation, which enables LLMs to directly generate SysMLv2 code. Recent research explored the potential of LLMs to support the adoption of MBSE. However, our investigation shows that research primarily focuses on the introduction phase by AI-supported model generation, requirements analysis, and automated consistency checking [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Far less attention has been paid to the operational use phase and facilitating the use of information stored in MBSE models. Addressing this gap is crucial to realizing the full potential of MBSE.

This study aims to develop a methodology that enables AI systems to access and leverage information stored in MBSE system models. The methodology is implemented in an LLM-based multi-agent system that employs a Graph-Retrieval-Augmented-Generation (GraphRAG) strategy. To demonstrate the feasibility of this approach, a chatbot is developed to answer content-related questions about the underlying system architecture.

The study is structured as follows: After introducing in Chapter 1, Chapter 2 shows the state of the art in Generative AI in MBSE, particularly the state of the art in information retrieval in system architectures. Chapter 3 introduces the LLM-based multi-agent-system. Chapter 4 shows the results demonstrated on a system architecture of a battery electric vehicle and a question and answer set of 100 questions. The study concludes with a discussion and outlook.

2. State of the Art

In this state-of-the-art, we discuss the benefits and adoption challenges of MBSE, review current research on the use of Generative AI in the context of MBSE, and highlight the need for research on enabling both human stakeholders and AI applications to access and leverage information stored in MBSE system models.

2.1. Model-Based Systems Engineering

The International Council of Systems Engineering (INCOSE) defines Model-based Systems Engineering as “a formalized application of modeling to support system requirements, design, analysis, verification and validation activities beginning in the conceptual design phase and continuing throughout development and later lifecycle phases” [

11].

MBSE consists of three key pillars: a modeling language, a modeling methodology, and a supporting tool. Traditionally, the modeling language SysML has been primarily graphical, requiring dedicated modeling tools with graphical editors to create and manipulate system models. The latest version, SysMLv2, introduces textual notation alongside the graphical representation. This textual notation enables models to be developed within standard integrated development environments (e.g., Visual Studio Code) [

12]. This reduces the dependency on specialized modeling tools and increases flexibility in model creation, as engineers can now choose between graphical, textual, or hybrid approaches. Most MBSE methodologies follow the Requirements–Functional–Logical–Physical (RFLP) paradigm, which is aligned with the left side of the V-Model—a widely established framework for structuring engineering processes starting at stakeholder requirements and breaking them down to physical components [

13].

The research community outlines several perceived benefits of MBSE. These perceived benefits include better communication, increased traceability, better complexity management, improved consistency and increased capacity for reuse i.e., reusability of models [

4] (p 60). However, Salado et al. investigated that only a small proportion (2 out of 360 or 0.6%) of scientific papers (journals and conference proceedings) actually measured the benefits of MBSE [

4] (p 65).

Moreover, MBSE faces some adoption challenges. In 2015 Bonnet et al. identified the following obstacles in a workshop dedicated to operational deployment of MBSE: cultural resistance, lack of management commitment, tooling challenges, restrictive IT policies and limited support, a steep learning curve, and difficulties in measuring [Return on Invest] ROI. [

14] (pp 511–512). Similar adoption challenges were identified by Bayer T. et al. in 2021 [

15] (p 10).

In 2018 Chami et al. summarize that the main challenges in MBSE adoption stem from human and technological factors such as awareness, resistance to change, and lack of clear resources—requiring early executive sponsorship and upfront investment. While some challenges emerge later, like complexity management, they should be anticipated from the start, though this is rarely done in practice. Ultimately, organizations must prioritize challenges by importance, timing, and dependencies. [

5]

In 2024 Call et al. concluded that perceived mental effort, limited access to modeling tools, and poor compatibility with existing SE practices significantly hinder MBSE adoption, underscoring the need to lower entry barriers and better align MBSE with established approaches. [

16] (p 473)

2.2. Generative Artificial Intelligence in MBSE

To enhance the accessibility of MBSE, ongoing research explores the application of generative artificial intelligence in the domain of MBSE.

Dumitrescu et al. introduce a maturity model for AI-based assistance systems in Model-Based Systems Engineering following the prominent SAE-Levels of automated driving. Level 0 means that no Generative AI is used in the development process. Level 1 includes generic AI capabilities to support general tasks. The release of ChatGPT by OpenAI in 2022 has effectively made Level 1 accessible to everybody. Level 2 refers to dedicated engineering copilots that can automate specific development tasks. From level 0 to level 5 the degree of AI-assistance grows gradually. Level 5 is described as AI assistants that can perform planning, execution and development tasks fully independently. Human stakeholders are proactively informed and alerted to decision needs. Additionally, the study mentions two AI-assistants: One to support MBSE workshops and another one to assist in modelling [

7].

Longshore et al. introduced SysEngBench, a domain-specific multiple choice benchmark that evaluates LLMs on systems engineering questions across 10 topics reflecting the core processes of systems engineering. [

17]

Another study examined the use of LLMs to automatically establish a trace between system model artefacts and requirements that are managed in different IT-systems [

8]. Some studies demonstrated feasibility to use LLMs for modelling system models in the textual notation of SysMLv2 [

9,

18]. Ghanawi et al. investigated the creation of SysML models from medical documents [

10].

Most of these efforts primarily target the creation phase of system models, aiming to reduce entry barriers, while the usage phase of MBSE models remains largely overlooked [

7,

8,

9,

10,

17,

18,

19]. This result is supported by Poulsen et al.’s investigation, which concluded that current research seems to focus on early SE activities, including modeling and analysis, such as requirements elicitation [

20].

As MBSE seeks to establish a consistent connection between engineering artefacts across the entire product lifecycle, it is crucial that heterogeneous stakeholder groups from different disciplinary backgrounds can access and utilize this information. A major challenge in this context is that domain experts without MBSE training have limited MBSE expertise, making it difficult for them to understand the models and efficiently find the required information.

2.2. Chatbots and Retrieval-Augmented-Generation

Given the difficulty that non-MBSE-trained domain experts face when interacting with system models, tools that simplify access to model information are essential. One promising solution is the use of chatbots. Chatbots are increasingly applied across domains such as education, e-commerce, healthcare, and entertainment due to their ability to provide scalable, on-demand assistance independent of expert availability [

21].

Transferring this concept to MBSE offers the potential to create interactive assistants capable of answering user queries about the system of interest. To achieve this, large language models that power the chatbot must be able to retrieve relevant information from system models.

With LLMs this capability is enabled through Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) [

22], a rapidly evolving research area. RAG extends LLMs with external knowledge sources by retrieving semantically relevant records and incorporating them into the prompt for response generation. Conventional approaches use vector databases and embedding-based similarity search. This approach works well for fact-based queries answerable with a small subset of documents. However, they struggle with sensemaking queries – questions that require reasoning over global patterns or relationships across an entire dataset. [

23]

To address this limitation, Edge et al. have introduced GraphRAG. GraphRAG uses graph-based structuring of text corpora. Entities and relationships are extracted from text to construct a knowledge graph, which is partitioned into hierarchical communities. LLMs generate bottom-up summaries within this hierarchy that are recursively aggregated into global representations and answer generation [

23]. Since then, various approaches and refinements of this approach have been developed. For more detailed information to GraphRAG and a benchmark of various approaches refer to [

24,

25].

The explicit representation of entities and their relationships in graph databases aligns naturally with the structure of MBSE system models, which are comparable to node–relationship constructs. This makes GraphRAG particularly promising for this use case.

Current SysMLv2 implementations, however, rely on a relational database with more than 8000 tables for model storage. While these ensure the preservation of complete syntactic information necessary for model exchange and tool interoperability, it introduces significant overhead when extracting semantically relevant content. As a result, system navigation and information retrieval remain cumbersome, limiting the practical integration of MBSE with LLM-based assistants. Tewari et al. present an approach that transfers Model-Based Systems Engineering (MBSE) models from SysML into a graph database to enable system analysis, such as determining which components fail during electrical shorts or finding alternative operational routes when conditions aren’t met [

26]. However, a key drawback of this methodology is that engineers must learn to write queries for the database to perform these analyses, which may limit adoption despite the powerful analytical capabilities the approach offers.

2.3. Research Need

MBSE system models are curated sets of structured engineering data and knowledge and are highly valuable assets in system development. However, many stakeholders lack familiarity with modeling approaches, specialized modeling tools, or the modeling language itself, limiting their ability to read, interpret, and utilize this valuable information beyond the domain of systems engineers. Thus, there is a need to explore how this information can be made accessible to diverse stakeholders.

Large Language Models (LLMs) offer promising potential to address this challenge, as they enable natural language interaction and can effectively navigate complex data structures through techniques such as Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation (GraphRAG). Knowledge graphs provide a suitable representation for storing and querying the structured information contained in MBSE system models.

This paper addresses this challenge by proposing an LLM-based multi-agent system with an individualized GraphRAG strategy for retrieving system model information. We demonstrate the benefit of this approach with a chatbot that answers questions about underlying system models. This enables both stakeholders and AI systems to access MBSE data, laying the groundwork for future MBSE-enhanced AI applications in the engineering domain.

To achieve this objective, the following research questions are investigated:

- 1.

How can MBSE system models that follow an RFLP modeling approach be transferred into a knowledge graph?

- 2.

How can a retrieval strategy be designed that leverages the metamodel of the system model?

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first approach of its kind that enables AI systems to effectively use information from MBSE system models.

3. Materials and Methods

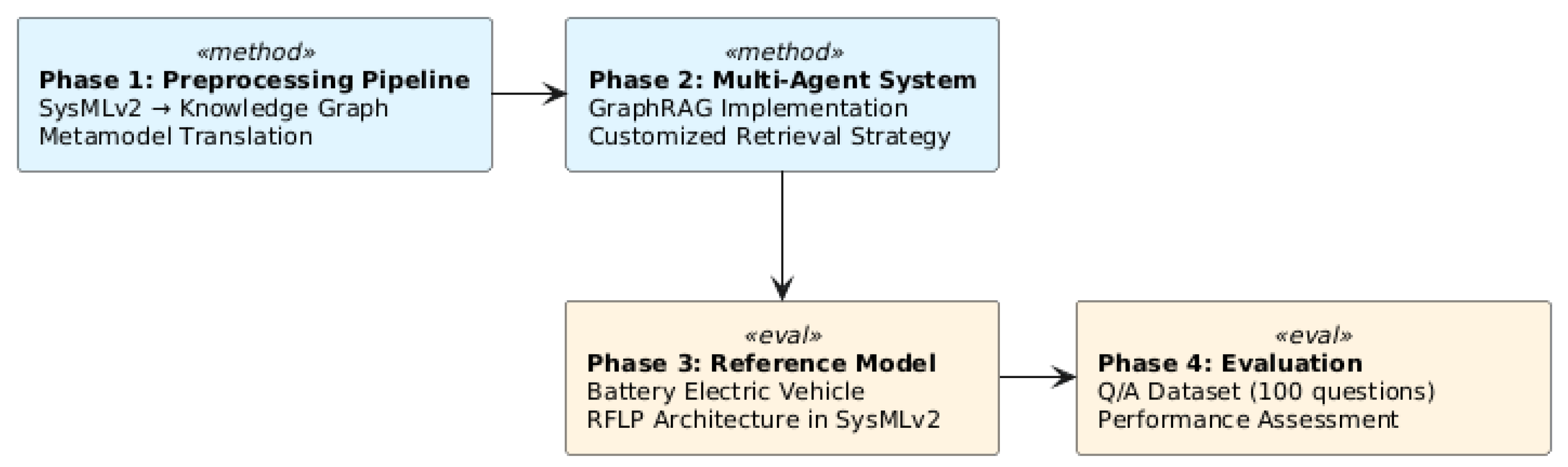

The proposed methodology is organized into four phases. In the first phase, a preprocessing pipeline is developed that converts system models from the textual notation of SysMLv2 into a knowledge graph. This involves translating the metamodel into a corresponding graph schema. Building on this knowledge graph, the second phase implements a hierarchical multi-agent system that leverages GraphRAG with a customized retrieval strategy to answer user queries. In the third phase, to demonstrate and evaluate the approach, a reference architecture of a battery electric vehicle is developed using SysMLv2 textual notation. The model covers all four levels of abstraction in the RFLP methodology, ensuring full traceability from requirements to functional decomposition and logical and physical implementation. Finally, the fourth phase evaluates the approach using a Q/A dataset comprising 100 questions, to assess its performance and reliability.

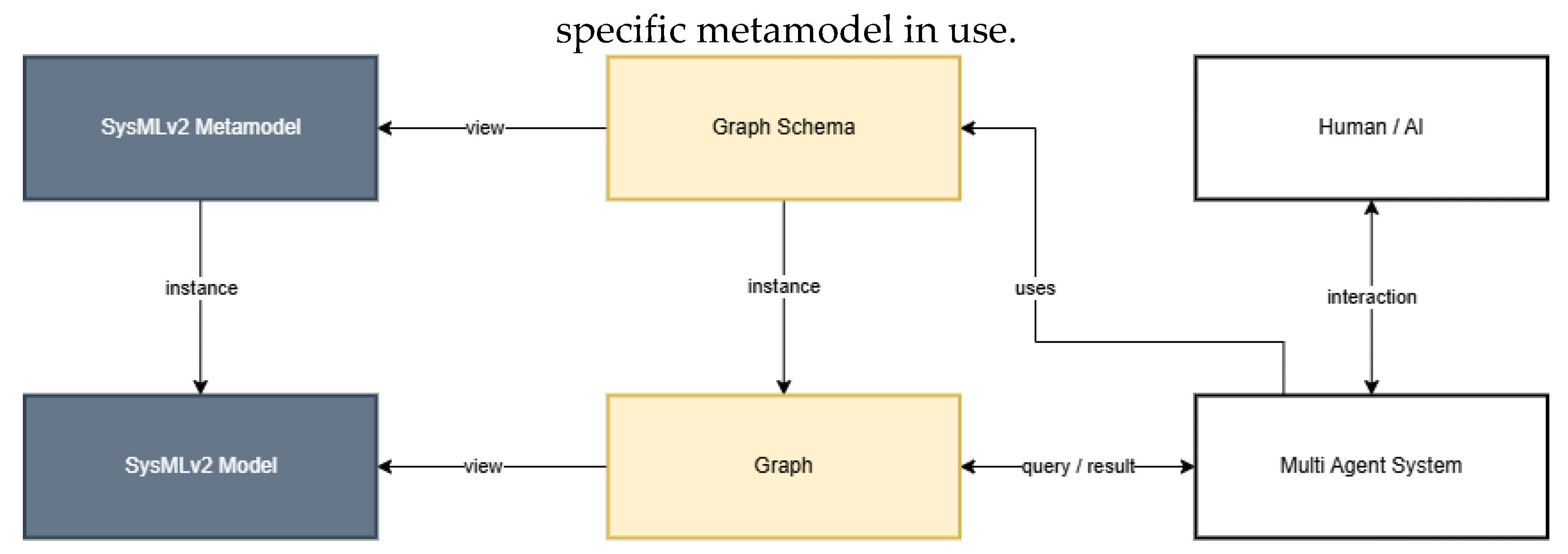

Figure 1 shows the preprocessing and user interaction part of our methodology.

3.1. Preprocessing Pipeline

A key distinction between classical GraphRAG applications and the proposed MBSE use case lies in the nature of the underlying data. Traditional GraphRAG implementations typically operate on unstructured or semi-structured sources such as text corpora like scientific articles, where the graph structure must first be inferred through entity extraction and relation identification. In contrast, MBSE system models already provide inherently structured data created by human experts, consisting of explicitly defined entities and relationships. This eliminates the need for entity extraction and entity-linking steps, allowing the graph representation to directly reflect the system architecture.

The overarching methodology is designed to be adaptable to any SysMLv2 model by developing a customized parser for the specific metamodel structure. However, the parser implementation developed for this work is specifically tailored to the RFLP (Requirements, Functions, Logical, Physical) abstraction framework and the particular SysMLv2 textual notation syntax used in this modeling approach. The parser cannot be directly applied to other SysMLv2 modeling methodologies without adaptation, as different metamodels may define different entity types, relationships, and syntactic structures.

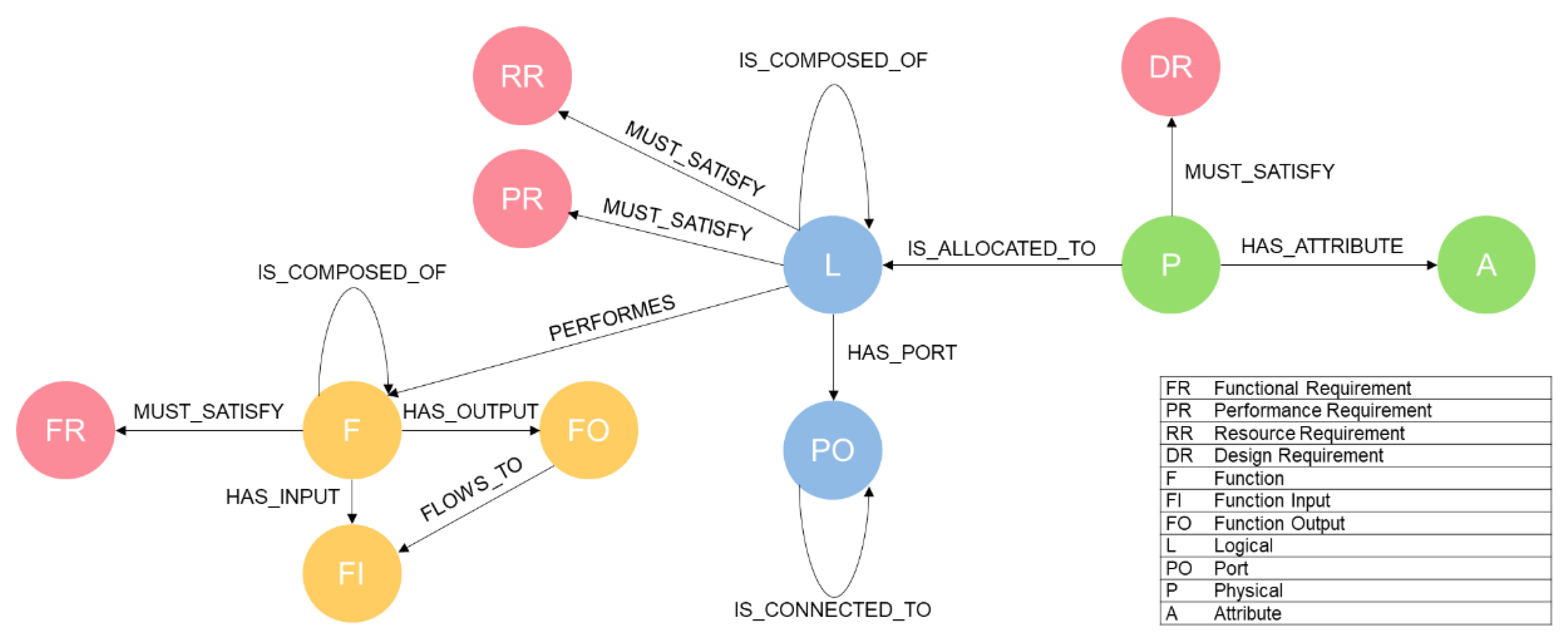

The first step of the preprocessing pipeline involves constructing a graph schema grounded in the chosen modeling methodology. This is achieved by mapping elements from the SysMLv2 textual notation to corresponding nodes and relationships in the graph. The metamodel defines the syntactic structure of the SysMLv2 notation and specifies which entity types and relationships are permissible within the system model.

In the second step, a custom Python-based parser is developed to process the SysMLv2 textual notation. The parser uses regular expressions and patterns matching to identify and extract entity definitions and their usages from the SysMLv2 code. It generates intermediate data structures in Python that represent the system model’s entities (requirements, functions, logical elements, physical elements, ports) and their relationships (satisfies, performs, is_composed_of, flows_to, is_connected_to, is_allocated_to). These intermediate structures are then converted into Cypher, the query language of the Neo4j graph database, to populate it. Cypher enables efficient querying and traversal of graph structures through pattern-matching syntax. To minimize graph complexity, only nodes representing instances of SysMLv2 entities are created, while entity definitions are omitted from the graph representation.

The parser distinguishes between entity definitions and entity usages in the SysMLv2 code. Definitions specify the structure and properties of reusable entity types (e.g., requirement definitions, function definitions), while usages instantiate these definitions with specific names and parameters. The parser extracts key information from both definitions and usages, such as descriptions (from documentation comments), parameters (inputs/outputs for functions, attributes for physical elements), and relationships (satisfied requirements, hierarchical decompositions, interface connections).

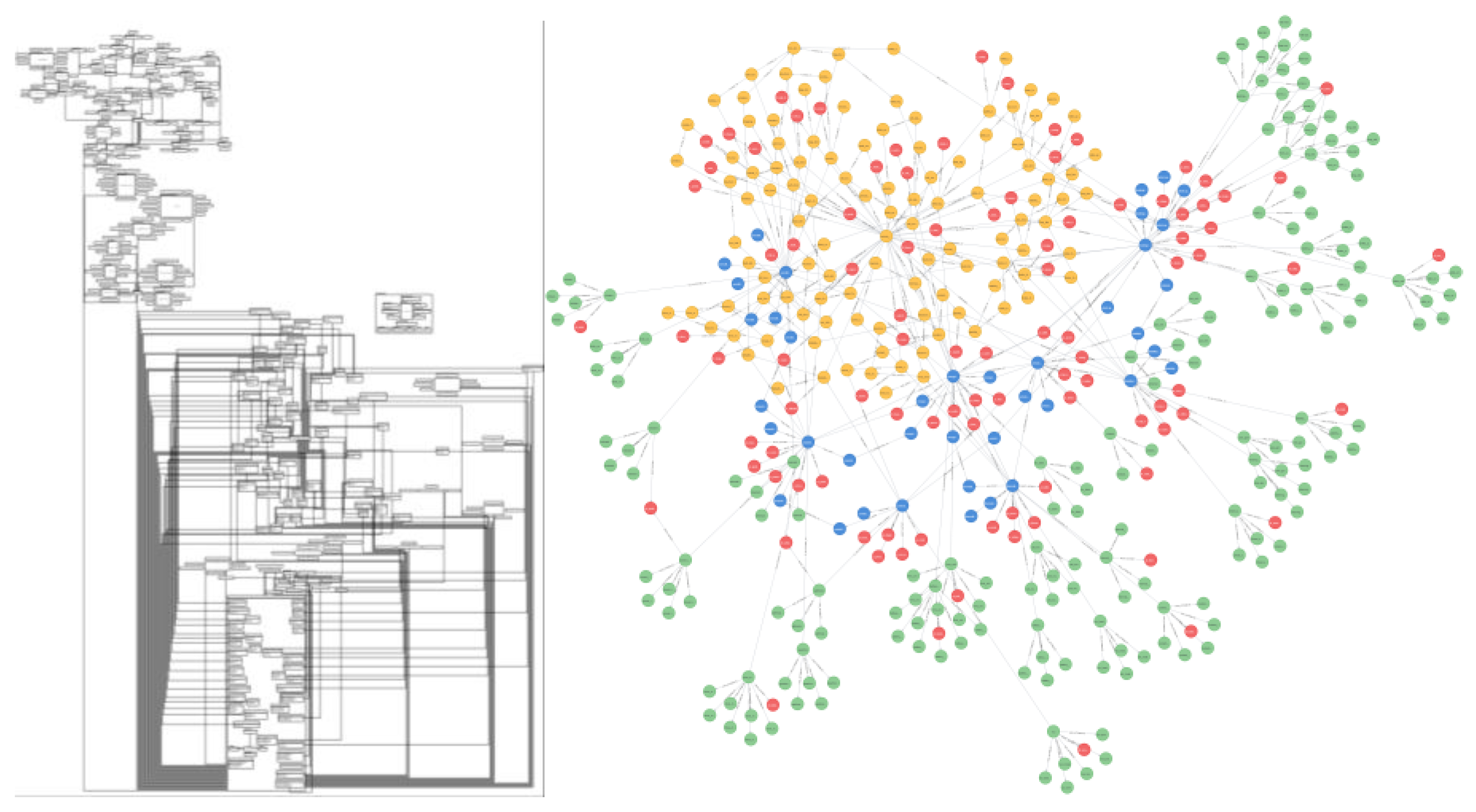

Figure 2 illustrates the resulting graph schema for the RFLP modeling approach. At the requirement level (indicated in red), the system model comprises functional requirements (FR), performance requirements (PR), resource requirements (RR), and design requirements (DR). At the functional layer (yellow), functions (F) are defined, each associated with function inputs (FI) and function outputs (FO). Function inputs and function outputs are linked via the flows_to relationship, while functions themselves can be hierarchically decomposed through the is_composed_of relationship. Additionally, functions are linked to functional requirements using the must_satisfy relationship.

The logical layer, indicated in blue, consists of logical elements (L) and ports (PO). Logical elements can be hierarchically decomposed via is_composed_of and perform functions as represented by the performs relationship. Logical elements are also connected to performance and resource requirements through the must_satisfy relationship. Ports are interconnected via the is_connected_to relationship, enabling the exchange of material, energy, or information between logical elements.

At the physical layer (green), physical elements (P) are associated with attributes (A) through the has_attribute relationship, and are required to satisfy design requirements via the must_satisfy relationship.

This preprocessing methodology transforms the system model from SysMLv2 code into a fully connected knowledge graph that preserves the semantics and traceability across the RFLP abstraction levels.

3.2. Multi-Agent System and Retrieval Strategy

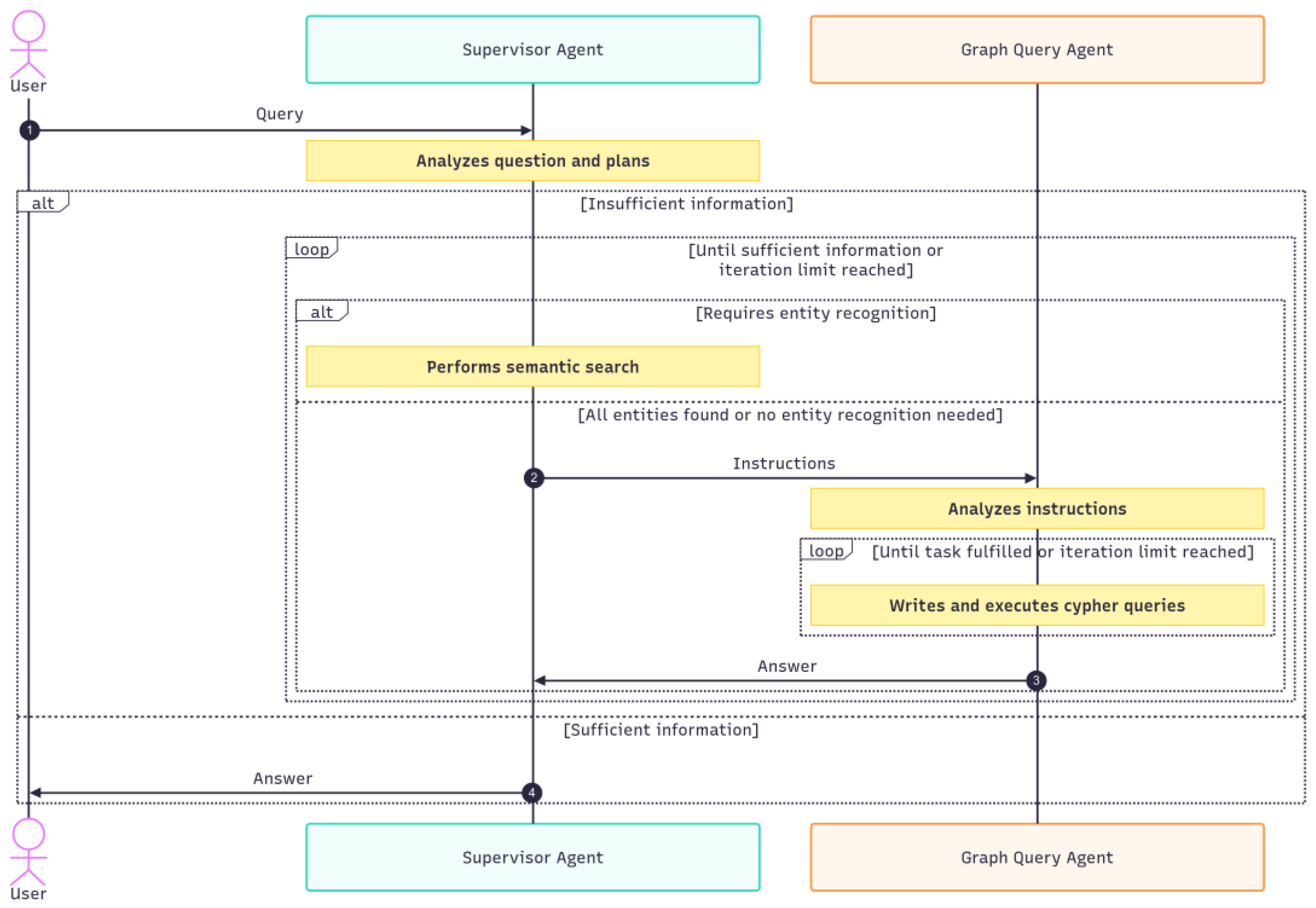

The chatbot and its retrieval strategy are implemented through two cooperating agents, referred to as the Supervisor Agent (SA) and the Graph Query Agent (GQA). The SA is responsible for managing the interaction with the user, maintaining the chat history, interpreting the user’s intent, decomposing queries into subtasks, planning the retrieval process, and reacting to intermediate or final results. To support this process, the supervisor employs a semantic search tool that relies on cosine similarity to identify semantically relevant nodes within the knowledge graph. Cosine similarity is a metric that measures the similarity between two vectors by calculating the cosine of the angle between them, with values close to 1 indicating high similarity and values close to 0 indicating low similarity. The search is performed on vector embeddings of the concatenation of every node’s name and description in the knowledge graph. Vector embeddings are high-dimensional numerical representations of text that capture semantic meaning, enabling mathematical comparison of textual content. The search input to this tool can be various natural language forms, ranging from single words to complete sentences.

Figure 3 shows the process that guides the supervisor’s actions. This process is defined in the system prompt. It begins with identifying the type of question posed by the user. The classification comprises two categories. The first category includes questions that require the identification of one or more specific entities, where a name or description of the entity is provided, such as identifying the design requirements for the e-motor. In this case, the semantic search is used to resolve the precise name and type of the node. This eliminates the need for a user to know the exact name of an element when asking a question. The second category encompasses questions that do not target specific entities but request more general information, such as listing all physical components of a system.

In both categories, the supervisor delegates the final retrieval step to the Graph Query Agent, ensuring that all retrieved information is traceable through a structured query. This allows every step of the query process to be mapped directly to the corresponding database result. When invoking the GQA, the supervisor provides an instruction that describes the intended query. This instruction is supplemented by a static prompt containing few-shot examples of valid Cypher queries aligned with the graph schema, which serves as guidance for query formulation.

The GQA processes the supervisor’s instructions and iteratively generates Cypher queries until the retrieval task is successfully completed. The results are then returned to the supervisor, who evaluates whether the retrieved information is sufficient to answer the user’s request. Both agents operate according to the Reason-Act (ReAct) pattern, reasoning over the intent and observations before taking the corresponding action [

27].

3.3. Reference Model: Battery Electric Vehicle Architecture

To demonstrate and evaluate the proposed methodology, a reference architecture of a battery electric vehicle (BEV) was developed using SysMLv2 textual notation. Creating a comprehensive system model manually would be prohibitively time-consuming; therefore, the LLM Claude Sonnet 3.7 and the LLM-powered search engine Perplexity were employed to accelerate the model generation process. Perplexity was used to collect information on the requirements, functions, logical and physical components of a battery electric vehicle. Independently, the author defined a metamodel specifying the SysMLv2 syntax to follow. Claude was then provided with this metamodel along with the RFLP information gathered by Perplexity and prompted to generate a SysMLv2 model of the battery electric vehicle in accordance with the metamodel guidelines. The resulting model was subsequently manually verified for syntactic correctness. It is important to note that the use of AI-assisted generation is not a prerequisite of the methodology; the preprocessing pipeline and multi-agent system work with any valid SysMLv2 model following the syntax of the metamodel.

The completed system architecture shown in

Figure 4 comprises 97 requirements, 37 functions, 9 logical components, and 34 physical components. The resulting knowledge graph contains 427 nodes and 505 relationships, representing a fully connected, multi-layered system model.

Requirements Architecture

The requirements architecture establishes four distinct categories. Functional requirements (37 total) define capabilities that the system must provide, including user authentication, real-time diagnostics, regenerative braking, and advanced driver assistance features. Performance requirements (28 total) specify quantitative measures such as driving range (400 km minimum), acceleration performance (0-100 km/h in <8s), and system response times. Resource requirements (16 total) constrain system utilization including energy consumption (<16 kWh/100km), power draw limits for subsystems, and environmental operating conditions. Design requirements (16 total) establish physical constraints including mass limits (motor <80 kg), dimensional envelopes, and integration constraints.

Functional Architecture

The functional architecture decomposes vehicle operations hierarchically under a top-level system coordination function. Functions span different domains: overall vehicle operations (authentication, diagnostics, connectivity), propulsion control (power delivery, drive modes, regenerative braking), energy management (cell monitoring, state estimation, thermal control), thermal regulation (active cooling, HVAC integration), vehicle dynamics (stability monitoring, intervention control), braking systems (dual-mode control, ABS/EBD), and driver assistance (object detection, lane keeping, emergency braking). Each function defines specific input/output flows using domain-specific signal types including data signals, control commands, and various energy forms like electrical, mechanical and thermal energy.

Logical Architecture

The logical architecture is divided into interconnected subsystems that each satisfy performance and resource requirements. Additionally, logical elements perform functions. The logical element “OverallVehicleLogical” serves as the top-level coordinator, integrating specialized logical elements:

“ConnectivityLogical” for user interfaces and connectivity

“PropulsionSystemLogical” for motor control and power conversion

“EnergyStorageLogical” for battery management and cell monitoring

“ThermalManagementLogical” for cooling and heating control

“VehicleControlLogical” for vehicle control

“StabilityControlLogical” for dynamics monitoring and intervention

“BrakingSystemLogical” for dual-mode braking and energy recovery and

“ADASSystemLogical” for sensor fusion and automated functions

Interfaces are used to exchange material, energy or information between logical elements using ports (31 total).

Physical Architecture

The physical architecture realizes logical components through distinct hardware elements spanning electronic control units, sensors, actuators, and mechanical components. Among others they include a permanent magnet synchronous motor with attributes like a peak power of 150 kW and a maximum torque of 350 Nm, a 100 kWh NMC811 battery pack, an ASIL-D compliant battery management unit, automotive-grade processors (Infineon AURIX TC397 for vehicle control, NVIDIA Orin for ADAS processing), and comprehensive sensor suites including cameras, radar, lidar, and inertial measurement units.

3.4. Question and Answer Dataset

To evaluate the proposed approach, a question–answer dataset was created. The dataset is structured into four categories (s.

Table 1). Questions are divided according to the number of relationships that must be traversed within the knowledge graph to gather all required information. A zero-to-one-hop question requires information that can be obtained either from a single node or from two nodes directly connected by a single relationship. In contrast, multi-hop questions demand the traversal of two or more relationships to retrieve the correct answer. By design, zero-to-one-hop questions are expected to be less complex and thus easier to resolve than multi-hop questions. The final dataset comprises 100 questions in total: 100 answerable questions, evenly split into 50 zero-to-one-hop and 50 multi-hop questions.

4. Results

This study presents a methodology that enables AI based interaction with MBSE system models created in SysMLv2. Figure 1 illustrates the final architecture. The architecture is composed of the SysMLv2 layer, a graph layer and the multi agent system.

The SysMLv2 metamodel defines the structural and semantic rules for system modeling. A SysMLv2 model is instantiated from this metamodel. To enable graph-based processing, the metamodel is transformed into a graph schema, which can be interpreted as a view on the metamodel. The SysMLv2 model is subsequently transformed into a graph structure that conforms to this graph schema, thereby representing a view on the SysMLv2 model.

The graph schema is used to instruct the agents of the multiagent system through their prompts. By querying the graph, the system retrieves relevant information and generates responses to questions about the system. Users and other AI systems interact with the multiagent system through natural language, which processes their requests by accessing the structured graph representation.

The methodology is designed to be adaptable to different SysMLv2 modeling approaches,

requiring only the definition of an appropriate graph schema and parser implementation for the

Figure 1.

Architecture for an LLM-based multi-agent-system using a GraphRAG retrieval strategy to access system model information

Figure 1.

Architecture for an LLM-based multi-agent-system using a GraphRAG retrieval strategy to access system model information

4.1 Evaluation

To evaluate this approach, the methodology was applied to a battery electric vehicle reference architecture and tested with a question-answer dataset. The following section presents the evaluation results.

We evaluated the performance of four large language models, namely Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free [

28], Gemini-2.0-flash-lite, Gemini-2.0-flash, and Gemini-2.5-flash-preview-04-17 [

29]. We have selected these LLMs due to their open-source availability. In all experimental settings, the same model was employed simultaneously as the Supervisor Agent and as the Graph Query Agent, ensuring that performance differences can be attributed directly to the model rather than to heterogeneous agent configurations. The evaluation considered the previously introduced categories of questions, which distinguish between zero-to-one-hop and multi-hop reasoning.

The results are presented in

Table 2. For zero-to-one-hop questions, all models achieved high accuracy, with Gemini-2.5-flash-preview-04-17 performing best at 96%. In contrast, multi-hop questions proved more challenging. Here, performance varied substantially, ranging from 50% for Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free to 90% for Gemini-2.5-flash-preview-04-17. The evaluation of related questions demonstrated particularly strong results for Gemini-2.5-flash-preview-04-17, which achieved 100% accuracy, meaning it clearly stated in all cases that the information is not present in the knowledge graph.

When averaging across the answerable categories, Gemini-2.5-flash-preview-04-17 outperformed the other models with 93% accuracy, followed by Gemini-2.0-flash and Gemini-2.0-flash-lite at 88% and 76%, respectively. Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free reached 75% on average, indicating lower robustness across question types. Overall, the evaluation confirms that Gemini 2.5 Flash consistently achieved superior retrieval performance across both simple and complex query types.

Table 3 presents the average response times of the evaluated LLMs across the three question categories. The Gemini series was accessed via Google AI Studio API, while the LLaMA-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo model was accessed through Together.ai API. The differences in the average response time between the Gemini and Llama Model are potentially caused by the API. Across all models, response times remained within a range that can be considered fast and suitable for interactive Q/A tasks. Among the configurations, Gemini 2.0 Flash Lite yielded the lowest average response time (6.15 s), while LLaMA-3.3 showed the longest latency (40.02 s). Although these differences exist, the primary finding is that the multi-agent system is able to generate answers in an acceptable response time across all evaluated settings. This underlines the feasibility of deploying such systems in an industrial use case.

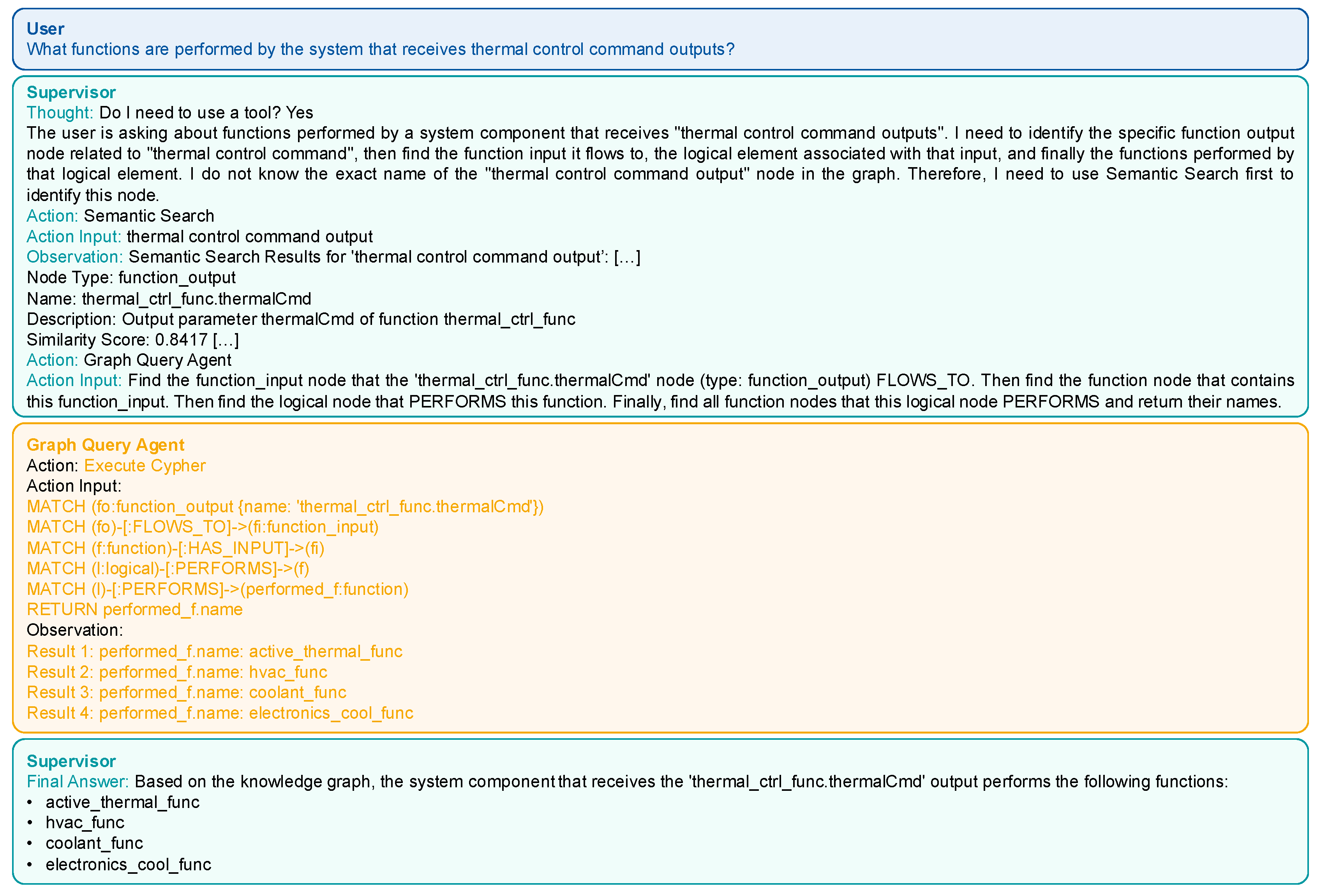

In the following we present an example of an answering process to a multi-hop question:

Figure 6 describes how the multi-agent system collaboratively answers the user’s technical question. The user asks which functions are performed by the system that receives thermal control command outputs. The Supervisor Agent first reasons about the task, deciding it needs to locate the relevant function output in the knowledge graph. Since the exact node name of the function output is unclear, it invokes a Semantic Search Agent, which returns several candidate nodes related to thermal control. The most relevant match is identified as thermal_ctrl_func.thermalCmd. Next, the Supervisor hands the query to a Graph Query Agent, which traces the graph structure. It follows the output node to the corresponding input node, identifies the function receiving this input, and then determines the logical element responsible for performing it. Finally, the agent collects all functions associated with this logical element. The result shows that the system receiving the thermal control command output performs the following functions: active_thermal_func, hvac_func, coolant_func, and electronics_cool_func.

In summary, the process illustrates how the different specialized agents coordinate to interpret the user’s natural language question, traverse the knowledge graph, and deliver an accurate, structured answer.

Together with the overall result we could demonstrate that the proposed multi-agent architecture can achieve both high accuracy and good response times. This confirms that the developed methodology and the tailored retrieval strategy provide a promising foundation for enabling AI-systems to access information in MBSE system models and thus improving accessibility to diverse stakeholders. The following discussion builds on these findings, outlines the limitations, and highlights perspectives for further refinement of the approach.

5. Discussion

This section examines the evaluation results and discusses factors that influence the performance and applicability of the proposed approach.

5.1. Influence of Language Model Selection

The evaluation revealed substantial performance differences between the tested LLMs, particularly in multi-hop reasoning tasks. Gemini 2.5 Flash achieved 90% accuracy on multi-hop questions, while Llama-3.3-70B reached only 50%. This 40-percentage-point gap suggests that model size and training strongly influence the ability to maintain reasoning consistency across multiple retrieval steps. The superior performance of Gemini 2.5 Flash may be attributed to better instruction following capabilities and more robust reasoning patterns. Furthermore, the system prompt and few-shot examples were not specifically optimized for each model, potentially disadvantaging some configurations. A more controlled comparison would require model-specific prompt engineering.

5.2. Response Time Considerations

The observed response times varied considerably, ranging from 6.15s (Gemini 2.0 Flash Lite) to 40.02s (Llama-3.3-70B). While all times remain within acceptable ranges for interactive use, these differences are influenced by multiple factors beyond model inference speed. API latency, network conditions, and server load contribute to the measured times, making direct performance comparisons between models difficult. The multi-agent architecture itself introduces overhead through multiple LLM calls per query. Optimizing the agent interaction pattern, such as minimizing unnecessary reasoning steps could improve response times across all configurations.

5.3. Impact of Model Characteristics on Accuracy

The choice of the reference system model influences evaluation outcomes in several ways. The battery electric vehicle architecture contains 427 nodes and 505 relationships, representing a moderately complex system. Larger industrial models with thousands of nodes and dense interconnections may challenge the retrieval strategy differently. The complexity of the graph probably has an impact on both the precision of semantic searches and the difficulty of formulating queries. The more nodes there are, the more likely it is that there will be an ambiguous match. Additionally, longer path traversals require more sophisticated Cypher queries.

The RFLP modeling approach provides a relatively clean hierarchical structure with well-defined relationship types. Models with more heterogeneous relationship semantics or less consistent naming conventions might degrade performance. Additionally, the question dataset was manually crafted to align with the model’s content and structure. Real-world user queries may be more ambiguous, use domain-specific terminology, or reference information not explicitly modeled, which would likely reduce accuracy below the reported 93%.

5.4. Integration into MBSE Development Practice

For practical adoption, the proposed approach must be seamlessly integrated into existing MBSE workflows. Currently, the methodology requires exporting SysMLv2 models and processing them through a custom parser, which introduces friction. Native support for graph database export in MBSE tools would streamline this process. The approach could serve multiple roles in systems engineering practice. During requirements engineering, stakeholders could query requirement satisfaction across system levels without navigating complex model diagrams. During design reviews, engineers could quickly identify which physical components realize specific functions or verify traceability from requirements to implementation. For documentation, the system could automatically generate stakeholder-specific views of the architecture by querying relevant subgraphs. However, these use cases require user studies to validate that non-expert stakeholders can effectively interact with the system and trust its responses.

5.5. Limitations and Scope

Several limitations constrain the generalizability of these findings. The custom parser implementation is specific to the RFLP metamodel and SysMLv2 textual notation used in this study. While the methodology is designed to be adaptable, applying it to other modeling approaches requires developing new parsers aligned with different metamodel structures. The evaluation was conducted on a synthetic architecture that, while reasonably complex, does not capture the full heterogeneity and scale of industrial system models. Real-world models often contain incomplete or inconsistent information, which was not reflected in the controlled reference model.

Furthermore, the absence of user studies limits conclusions about usability and stakeholder acceptance. High accuracy on predefined questions does not guarantee that the system meets the actual information needs of systems engineers, project managers, or other stakeholders in practice. The lack of comparable approaches and standardized benchmarks for question-answering over MBSE models also hinders cross-study validation. The development of community-driven evaluation datasets, similar to efforts in other domains, would support more rigorous comparative analysis across different methodologies.

6. Summary and Outlook

This work presents a methodology for enabling AI-based natural language interaction with MBSE system models through knowledge graph representation and multi-agent retrieval. The approach addresses the challenge of making MBSE system models accessible to both AI systems and stakeholders without specialized modeling expertise. The methodology comprises a preprocessing pipeline that transforms SysMLv2 models into knowledge graphs based on a derived graph schema, and a hierarchical multi-agent system that leverages a customized retrieval strategy. Evaluation on a battery electric vehicle reference architecture with 100 questions demonstrated that the best performing configuration (Gemini 2.5 Flash) achieved 93% accuracy with response times suitable for interactive use. The results indicate that AI systems can effectively retrieve structured information from MBSE system models, supporting the hypothesis that graph-based representations enable robust question answering capabilities across different levels of query complexity.

Several directions for future work emerge from this study. First, evaluating the approach on larger scale industrial MBSE system models is necessary to assess scalability and identify performance bottlenecks. Ongoing research in collaboration with automotive industry partners is examining these aspects. Second, testing different context engineering approaches and alternative architectures for the agent system could improve performance and efficiency. This includes experimenting with different prompt structures, few-shot example selections, and agent coordination patterns to optimize both accuracy and response time. Third, an investigation of the advantages and disadvantages of alternative graph representations, such as the Resource Description Framework, with respect to accuracy, response time, and interoperability should be conducted. Finally, establishing standardized benchmarks for question answering over MBSE system models would enable systematic comparison of different retrieval strategies and support community-driven improvements. Such benchmarks could include diverse MBSE system models and query complexities. The development of native graph database support in MBSE tools represents a particularly promising direction, as it would eliminate the need for external preprocessing and enable real-time synchronization between model edits and graph representation. This would result in MBSE models becoming knowledge sources that can be queried directly. This fundamental change would impact how stakeholders interact with system architectures throughout the development lifecycle.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.Q.; methodology, V.Q; software, V.Q.; validation, V.Q.; formal analysis, V.Q.; investigation, V.Q.; resources, V.Q.; data curation, V.Q.; writing—original draft preparation, V.Q.; writing—review and editing, V.Q., G.J., G.H. and S.D.; visualization, V.Q.; supervision, S.D. and G.H.; project administration, S.D.; funding acquisition, S.D.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been conducted in the context of the publicly funded research procect „KIMBA – Künstliche Intelligenz für Systemmodellbildung und Anforderungen” by the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Energy with the grant number FKZ: 19S24001I. The APC was funded by RWTH Aachen University Open Access Publication Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Perplexity and Claude for the purposes of creating an artificial MBSE system architecture in SysMLv2. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SE |

Systems Engineering |

| MBSE |

Mode-based Systems Engineering |

| AI |

Artificial Intelligence |

| GenAI |

Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| RAG |

Retrieval Augmented Generation |

| GraphRAG |

Graph Retrieval Augmented Generation |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

References

- Salado, A. Introduction to Systems Engineering in the 21st Century: Volume 1. Systems Engineering Series; Cuadernos de Isdefe, 2024, ISBN 978-84-695-7816-2.

- Griffor, E.R.; Greer, C.; Wollman, D.A.; Burns, M.J. Framework for cyber-physical systems: volume 1, overview, Gaithersburg, MD, 2017.

- Madni, A.M.; Sievers, M. Model-based systems engineering: Motivation, current status, and research opportunities. Systems Engineering 2018, 21, 172–190. [CrossRef]

- Henderson, K.; Salado, A. Value and benefits of model-based systems engineering (MBSE): Evidence from the literature. Systems Engineering 2021, 24, 51–66. [CrossRef]

- Chami, M.; Bruel, J.-M. A Survey on MBSE Adoption Challenges. Proceedings of INCOSE EMEASEC 2018 2018, 2018, 1–15.

- Förster, F.; Koldewey, C.; Bernijazov, R.; Dumitrescu, R.; Bursac, N. Navigating viewpoints in MBSE: challenges, potential and pathways for stakeholder participation in industry. Proc. Des. Soc. 2025, 5, 2531–2540. [CrossRef]

- Bernijazov, R.; Dumitrescu, R.; Hanke, F.; Heißen, O. von; Kaiser, L.; Tissen, D. AI-Augmented Model-Based Systems Engineering. Zeitschrift für wirtschaftlichen Fabrikbetrieb 2025, 120, 96–100. [CrossRef]

- Bonner, M.; Zeller, M.; Schulz, G.; Savu, A. LLM-based Approach to Automatically Establish Traceability between Requirements and MBSE. INCOSE International Symp 2024, 34, 2542–2560. [CrossRef]

- DeHart, J.K. Leveraging Large Language Models for Direct Interaction with SysML v2. INCOSE International Symp 2024, 34, 2168–2185. [CrossRef]

- Ghanawi, I.; Chami, M.W.; Chami, M.; Coric, M.; Abdoun, N. Integrating AI with MBSE for Data Extraction from Medical Standards. INCOSE International Symp 2024, 34, 1354–1366. [CrossRef]

- INCOSE. MBSE-Initiative. Available online: https://www.incose.org/communities/working-groups-initiatives/mbse-initiative (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- OMG. SysML v2: The Next Generation Systems Modeling Language. Available online: https://www.omg.org/sysml/sysmlv2/ (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Estefan, J.A.; others. Survey of model-based systems engineering (MBSE) methodologies. Incose MBSE Focus Group 2007, 25, 1–12.

- Bonnet, S.; Voirin, J.-L.; Normand, V.; Exertier, D. Implementing the MBSE Cultural Change: Organization, Coaching and Lessons Learned. INCOSE International Symp 2015, 25, 508–523. [CrossRef]

- Bayer, T.; Day, J.; Dodd, E.; Jones-Wilson, L.; Rivera, A.; Shougarian, N.; Susca, S.; Wagner, D. Europa Clipper: MBSE Proving Ground. In 2021 IEEE Aerospace Conference (50100). 2021 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 06–13 Mar. 2021; IEEE, 2021; pp 1–19, ISBN 978-1-7281-7436-5.

- Call, D.R.; Herber, D.R.; Conrad, S.A. The Effects of the Assessed Perceptions of MBSE on Adoption. INCOSE International Symp 2024, 34, 462–478. [CrossRef]

- Bell, R.; Longshore, R.; Madachy, R. Introducing SysEngBench: A Novel Benchmark for Assessing Large Language Models in Systems Engineering; Acquisition Research Program, 2024. Available online: https://dair.nps.edu/handle/123456789/5135.

- Johns, B.; Carroll, K.; Medina, C.; Lewark, R.; Walliser, J. AI Systems Modeling Enhancer (AI-SME): Initial Investigations into a ChatGPT-enabled MBSE Modeling Assistant. INCOSE International Symp 2024, 34, 1149–1168. [CrossRef]

- Chami, M.; Zoghbi, C.; Bruel, J.-M. A First Step towards AI for MBSE: Generating a Part of SysML Models from Text Using AI. INCOSE Artificial Intelligence: 2019 Conference Proceedings. 1st Edition; pp 123–136.

- Poulsen, V.V.; Guertler, M.; Eisenbart, B.; Sick, N. Advancing systems engineering with artificial intelligence: a review on the future potential challenges and pathways. Proceedings of the Design Society 2025, 5, 359–368. [CrossRef]

- Caldarini, G.; Jaf, S.; McGarry, K. A Literature Survey of Recent Advances in Chatbots. Information 2022, 13, 41. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Knowledge-Intensive NLP Tasks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; H. Larochelle, M. Ranzato, R. Hadsell, M.F. Balcan, H. Lin, Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc, 2020; pp 1–16.

- Edge, D.; Trinh, H.; Cheng, N.; Bradley, J.; Chao, A.; Mody, A.; Truitt, S.; Metropolitansky, D.; Ness, R.O.; Larson, J. From Local to Global: A Graph RAG Approach to Query-Focused Summarization, 2024. Available online: http://arxiv.org/pdf/2404.16130v2.

- Xiang, Z.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, S.; Hong, Z.; Huang, X.; Su, J. When to use Graphs in RAG: A Comprehensive Analysis for Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation, 2025. Available online: http://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.05690v1.

- Peng, B.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Bo, X.; Shi, H.; Hong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, S. Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation: A Survey, 2024. Available online: http://arxiv.org/pdf/2408.08921v2.

- Tewari, A.; Dixit, S.; Sahni, N.; Bordas, S.P. Machine learning approaches to identify and design low thermal conductivity oxides for thermoelectric applications. DCE 2020, 1. [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhao, J.; Yu, D.; Du, N.; Shafran, I.; Narasimhan, K.; Cao, Y. ReAct: Synergizing Reasoning and Acting in Language Models, 2022.

- together.ai. Llama 3.3 70B API. Available online: https://www.together.ai/models/llama-3-3-70b (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Google. Googel AI Studio. Available online: https://aistudio.google.com/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).