Introduction

Orbital blowout fracture (OBF) is a relatively common type of maxillofacial fracture resulting from blunt trauma to the orbit. Like all other elements of the facial skeleton, the resistance of the bony orbits to trauma is provided mainly by the maxillofacial buttresses. The facial skeleton components that form the walls of the paranasal sinuses participate directly or indirectly in this buttress system. Thus, the highly complex paranasal skeleton, which varies considerably in size and shape among individuals, plays a role in maintaining the integrity of the facial bones [

1,

2]. There are publications in the literature demonstrating the relationship between frontal sinus dimensions and the incidence of anterior table frontal sinus fractures, and between maxillary sinus volume and the incidence of zygomatic fractures [

3,

5]. However, to our knowledge, no study investigating the relationship between ethmoid sinus volume (ESV) and the incidence of any facial fracture has been published to date.

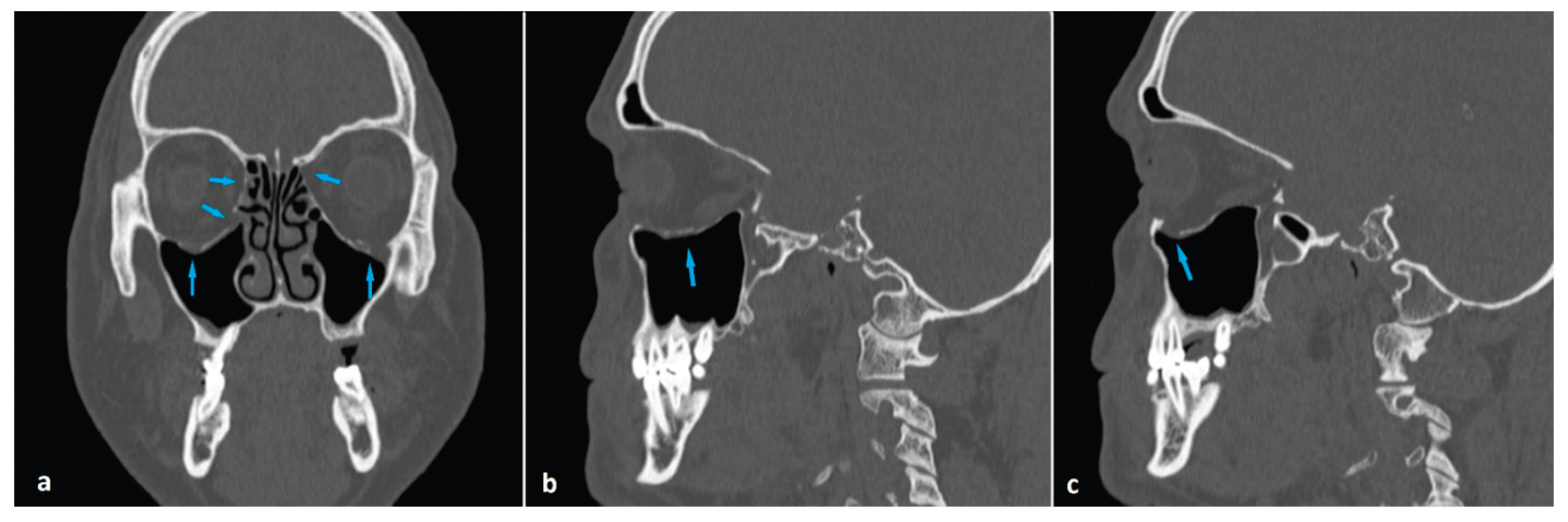

The ethmoid sinus is a unique structure in that it contains multiple air chambers, unlike the other paranasal sinuses, which usually consist of a single air compartment. This special air space, located between the nasal and oral cavities, consists of multiple air cells formed by thin bones and separated from each other by the basal lamella of the middle turbinate [

6] (

Figure 1). Removal of ethmoidal septa during endoscopic sinus surgery has been shown to cause a change in the biomechanics of the orbit, leading to an increased risk of OBF, which is more pronounced in the medial wall than in the orbital floor [

7,

8]. We hypothesized that in a large ethmoid sinus, aligning the air cell walls relatively farther apart would reduce their buttressing effect for the orbital walls. The purpose of this study was to investigate whether increased ESV constitutes a risk factor for the occurrence of OBF following craniofacial trauma. Besides, we aimed to explore whether there is a relationship between ESV and OBF patterns.

Material and Methods

2.1. Study Sample and Design

Our study was initiated after receiving approval from the Ethics Approval Committee of the University of Health Sciences, Ankara Etlik City Hospital (Approval date and number: 16 Aug 2023, 2023-484) and conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Due to the retrospective design of the study, informed consent was not obtained. The radiological records of patients who were admitted to the Emergency Department following head trauma and underwent craniofacial computed tomography (CT) examination between October 1, 2022, and September 1, 2023, were retrospectively evaluated. The case group consisted of subjects with one or more OBF in one or both orbits. The control group included subjects without any facial fractures. The inclusion criterion for both groups was being over 15 years of age. The exclusion criteria for both groups were skull fracture and intracranial injury.

The predictor variable of the study was ESV, and the main outcome variable was the incidence of OBF. So we compared the case and control groups in terms of mean ESV. Sex was one of the two covariates of the study, and we compared case and control groups in terms of mean ESV separately for both women and men. The other covariate was the fracture location. The case group was divided into subgroups as follows: medial wall fractures, orbital floor fractures, and the fractures in both the medial wall and orbital floor (

Figure 2). The mean ESV value of each subgroup was compared with that of the control group.

2.2. CT Protocol and Volumetric Measurements with 3D Slicer

Imaging was performed by a 128-slice CT scanner (Revolution EVO, GE Healthcare System), using the following imaging parameters: 120 kV, 220 mAs, slice thickness= 0.625 mm, FOV= 18-24 cm. Reconstructions in three orthogonal planes with bone and soft tissue algorithms were used in the diagnosis of fractures. Fracture diagnosis and localization were determined separately by two radiologists experienced in the field of emergency radiology. In cases of conflicting diagnoses, the two radiologists evaluated the case together and reached a consensus.

We obtained subjects' CT images from our hospital's Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) and saved them in Digital Imaging and Communications Medicine (DICOM) format. DICOM data were then transferred to a personal computer. 3D Slicer (

https://www.slicer.org/, version 5.3.1), a fully automated open-source software, was used for analysis (accessed on 5 Sep 2025) [

9]. Images were displayed in the axial, coronal, and sagittal planes using the 3D Slicer application, and segmentation was performed (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). The following steps were followed to select images suitable for segmentation and perform volumetric measurements.

1. The "Segment Editor" option was selected from the integrated tools in the "Modules" tab of the 3D Slicer screen.

2. New segmentation tabs were added with the "Add" toolbar.

3. In the first segment, the optimal spacing was set with the "Threshold" tool to encompass the anatomical boundaries of the ethmoid sinus (Threshold = -1500/-799 HU).

4. The raw images of the structures were displayed in three dimensions with the "Apply" command in the "View in 3D" tab.

5. The anatomical boundaries of the ethmoid sinus structures we wanted to study were examined, and any unsuitable areas were adjusted with the "Paint," "Erase," and "Scissors" tools.

6. A report showing the volume measurements of the structures was automatically obtained from the “Quantification” tab in the “Modules” table of the program.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

Considering the effect size of 0.706 reported in medial wall measures and a Type I error rate of 0.05, the achieved statistical power of the study was calculated to be 0.99. G*Power was used to calculate the power of the study.

Age and ESV were compared between case and control groups according to the distributional characteristics of the variables. Since the age variable did not meet the assumptions of normality, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for group comparisons, and descriptive statistics were presented as median and interquartile range. For ESV, which showed a normal distribution, group comparisons were performed using the independent samples t-test, and descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The chi-square test was used to assess the relationship between categorical variables. Frequencies and percentages were used to summarize categorical data. A Type I error level of 0.05 was adopted for all statistical tests. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Released 2011, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study sample are demonstrated in

Table 1. The case group consisted of 108 subjects, and the control group consisted of 122 subjects. In the case group, there were 32 (31%) females and 76 (69%) males with a median age of 41.5 years (range: min 16, max 92). The control group consisted of 38 (31%) females and 84 (69%) males with a median age of 38 years (range: min 18, max 96). While both groups were predominantly male, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups in terms of sex distribution (p= 0.803). No statistically significant difference between case and control groups in terms of median age (p= 0.463) was noted.

In the examination of 108 subjects in the case group, two (1.8%) subjects had OBF in both orbits. So we identified a total of 110 OBFs: 38 (34%) in the right orbit and 72 (66%) in the left orbit. Of all the fractures, 75 (68.2%) were located in the orbital floor, 18 (16.4%) in the medial wall, and 17 (15.4%) in both the medial wall and orbital floor. Of the two subjects with bilateral OBF, one had fractures in the medial walls, and the other had fractures in both the medial walls and orbital floors.

Comparison of the case and control groups in terms of mean ESV is shown in

Table 2. The mean ESV in the case group (3.91 ± 1.39 cm

3) was significantly higher than that in the control group (2.82 ± 0.94 cm

3) (p<0.001). Similarly, the mean ESV values in both males and females were significantly higher in the case group than in the control group (p<0.001). Subgroup analyses showed that the mean ESV values of both the cases with medial wall fracture and those with orbital floor fracture were significantly higher than the mean ESV of the control group (p: 0.024 and 0.012, respectively). The association was more pronounced in the cases with orbital wall fractures compared to those with medial wall fractures. However, there was no statistically significant difference between the control group and the cases with medial wall and orbital floor fracture in terms of mean ESV (p= 0.562) (

Table 3).

Discussion

We retrospectively investigated the relationship between ESV and the incidence of OBF after craniofacial trauma. Making volumetric measurements of the ethmoid sinuses of subjects with and without OBF, we demonstrated that mean ESV was significantly higher in subjects with OBF compared with those without OBF (p<0.001). This association was more pronounced in cases with orbital floor fracture (p= 0.012) compared to those with medial wall fracture (p= 0.024). However, no significant difference between the control group and the cases with medial wall and orbital floor fracture in terms of mean ESV was noted (p= 0.562). We found that OBF was more frequent in males (69%), and the most common fracture site was the orbital floor (68.2%). We detected bilateral OBFs in two (1.8%) subjects.

OBFs are isolated orbital wall fractures in which the orbital rim integrity is preserved. If not treated in time by the appropriate method, they can cause permanent functional and cosmetic disorders [

10,

11,

12]. They occur as a result of a traumatic impact on the globe transmitted to the orbital walls. Assaults and falls have been reported as the two most common causes of OBFs [

13,

14]. They are most frequently located in the orbital floor, followed by the medial wall [

15,

16]. They occur more frequently in men than in women [

16,

17]. In accordance with the previous data, OBFs were more frequent in males (69%) and mostly located in the orbital floor (68.2%) in our study sample.

There are reports in the literature indicating that OBF, although rare, can occur bilaterally. Bilateral OBF has been reported to occur most commonly in older adults and as a result of exposure to high-energy trauma. The medial orbital wall has been shown to be more frequently affected in bilateral cases [

15,

18,

19]. In our sample, there were two (1.8%) subjects with bilateral OBF. Both were male and above the median age of the case population. One had fractures in the medial walls, and the other had fractures in both the medial walls and the orbital floors (

Figure 5).

Like other maxillofacial fractures, OBFs occur when a traumatic force beyond the resistance of the maxillofacial buttress system impinges on the face. The maxillofacial buttress system is mainly made up of four pairs of thick bony struts extending in vertical and horizontal planes and constitutes a unifying and protective structure that provides resistance of the facial skeleton against trauma. The medial orbital wall and the orbital floor are mainly supported by the medial vertical and upper transverse maxillary buttresses, respectively. Paranasal sinus walls align in continuity with this buttress system [

10,

11]. Previous data on ethmoid sinus biomechanics suggest that the uncinate process and ethmoid air cells serve as a buttress for the medial orbital wall, maintaining its integrity against trauma. This assumption explains why OBFs occur more frequently in the orbital floor, even though the medial orbital wall is thinner [

7,

8,

20,

21]. The ethmoid sinus typically consists of 7 smaller anterior and 4 larger posterior cells.

6 As ethmoid sinus volume increases, the surface area of the sinus and the distance between the ethmoid septae will increase. This configurational change can be expected to reduce the stabilizing effect of the ethmoidal septae on the orbital wall. Our results support the hypothesis that increasing ESV reduces orbital wall resistance and increases the risk of OBF.

In their retrospective study, Buller et al. focused on the stabilizing effect of the maxillary sinus on the zygomaticomaxillary complex. By comparing maxillary sinus dimensions in cases with and without zygomatic bone fractures, they found that the incidence of fracture was significantly higher in patients with greater sinus height and volume [

5]. Two recently published studies on frontal fractures, which made similar assumptions about the relationship between paranasal sinus volume and fracture frequency, yielded similar results to the study on zygomatic fractures. They demonstrated a significant association between frontal sinus size and frontal fracture size and type [

3,

4]. The ethmoid sinus differs from other sinuses in terms of its central configuration and unique morphology. Because of its critical contact with the orbits, we addressed the effect of ESV on the resistance of the orbital wall to trauma in our study.

Unlike the cases with medial wall fractures and those with orbital floor fractures, we found no significant difference in mean ESV between cases with medial wall and orbital floor fractures and the control group. This finding implies that there is a difference between the mechanism of formation of the fracture pattern involving both the medial wall and orbital floor and the mechanism of the other two fracture patterns. This difference may be related to the cause of the trauma or the level of trauma energy transferred to the bone tissue. The momentum vector may also be another variable affecting the fracture configuration.

The main limitation of our study is that we did not evaluate the relationship between ESV and certain OBF characteristics, such as the degree of comminution, presence or absence of infraorbital canal injury, whether the fracture was accompanied by herniation, and presence or absence of rectus muscle injury. Another limitation of this study is that the cause and mechanism of trauma to the orbit were not addressed. Further comprehensive studies addressing the cause and the energy level of trauma are needed to draw accurate conclusions regarding the effect of ESV on the OBF pattern.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the relationship between ESV and the incidence of any facial fracture. The results of this study demonstrated a significant association between ESV and the incidence of OBF after craniofacial trauma. We found that a large ethmoid sinus not only increases the risk of OBF but also affects the fracture pattern. Based on the results obtained in this study, we identified a large ethmoid sinus as a predictive risk factor for OBF.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Ö.; Methodology, M.Ö. and H.S.; Software, H.S.; Validation, M.Ö., E.Ö. and R.P.K.; Formal Analysis, S.Y.; Investigation, M.Ö.; Resources, M.Ö.; Data Curation, M.Ö. and H.S.; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, M.Ö.; Writing – Review & Editing, M.Ö.; Visualization, M.Ö. and H.S.; Supervision, M.Ö.; Project Administration, M.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Health Sciences, Ankara Etlik City Hospital (Approval date and number: 16 Aug 2023, 2023-484).

Informed consent statement

The requirement to obtain informed consent for participation was waived due to the retrospective design of the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

References

- Winegar BA, Murillo H, Tantiwongkosi B. Spectrum of critical imaging findings in complex facial skeletal trauma. Radiographics. 2013 Jan-Feb;33(1):3-19. PMID: 23322824. [CrossRef]

- Reinoso PC, Robalino JJ, Santiago MG. Biomechanics of midface trauma: A review of concepts. Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol. 2021 July;33(4):389-393. [CrossRef]

- Buller J, Maus V, Grandoch A, Kreppel M, Zirk M, Zöller JE. Frontal Sinus Morphology: A Reliable Factor for Classification of Frontal Bone Fractures? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2018 Oct;76(10): 2168.e1-2168.e7. Epub 2018 Jun 22. PMID: 30009786. [CrossRef]

- Buller J, Kreppel M, Maus V, Zirk M, Zöller JE. Risk of frontal sinus anterior table fractures after craniofacial trauma and the role of anatomic variations in frontal sinus size: A retrospective case-control study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2019 Apr;47(4):611-615. Epub 2019 Jan 18. PMID: 30718214. [CrossRef]

- Buller J, Bömelburg C, Kruse T, Zirk M. Does maxillary sinus size affect the risk for zygomatic complex fractures? Clin Anat. 2023 May;36(4):564-569. Epub 2023 Jan 20. PMID: 36461725. [CrossRef]

- A IS, Rivas-Rodriguez F, Capizzano AA. Imaging Anatomy of the Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2025 Sep 13: S1042-3699(25)00056-1. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40947313. [CrossRef]

- Ramesh S, Bokman C, Mustak H, Lo C, Goldberg R, Rootman D. Medial Buttressing in Orbital Blowout Fractures. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018 Sep/Oct;34(5):456-459. PMID: 29334542. [CrossRef]

- Sowerby LJ, Harris MS, Joshi R, Johnson M, Jenkyn T, Moore CC. Does endoscopic sinus surgery alter the biomechanics of the orbit? J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020 Jun 26;49(1):44. PMID: 32586389; PMCID: PMC7318533. [CrossRef]

- Fedorov A, Beichel R, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Finet J, Fillion-Robin JC, Pujol S, Bauer C, Jennings D, Fennessy F, Sonka M, Buatti J, Aylward S, Miller JV, Pieper S, Kikinis R. 3D Slicer as an image computing platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn Reson Imaging. 2012 Nov;30(9):1323-41. Epub 2012 Jul 6. PMID: 22770690; PMCID: PMC3466397. [CrossRef]

- Felding UNA. Blowout fractures - clinic, imaging and applied anatomy of the orbit. Dan Med J. 2018 Mar;65(3): B5459. PMID: 29510812.

- Ahmad F, Kirkpatrick NA, Lyne J, Urdang M, Waterhouse N. Buckling and hydraulic mechanisms in orbital blowout fractures: fact or fiction? J Craniofac Surg. 2006 May;17(3):438-41. PMID: 16770178. [CrossRef]

- Shin JW, Lim JS, Yoo G, Byeon JH. An analysis of pure blowout fractures and associated ocular symptoms. J Craniofac Surg. 2013 May;24(3):703-7. PMID: 23714863. [CrossRef]

- Gómez Roselló E, Quiles Granado AM, Artajona Garcia M, Juanpere Martí S, Laguillo Sala G, Beltrán Mármol B, Pedraza Gutiérrez S. Facial fractures: classification and highlights for a useful report. Insights Imaging. 2020 Mar 19;11(1):49. PMID: 32193796; PMCID: PMC7082488. [CrossRef]

- Lorencin M, Orihovac Ž, Žaja R, Begović I. Orbital blowout fractures: A retrospective study with literature review. Acta Clin Croat. 2023 Nov;62(3):519-526. PMID: 39310679; PMCID: PMC11414006. [CrossRef]

- Valencia MR, Miyazaki H, Ito M, Nishimura K, Kakizaki H, Takahashi Y. Radiological findings of orbital blowout fractures: a review. Orbit. 2021 Apr;40(2):98-109. Epub 2020 Mar 26. PMID: 32212885. [CrossRef]

- Shere JL, Boole JR, Holtel MR, Amoroso PJ. An analysis of 3599 midfacial and 1141 orbital blowout fractures among 4426 United States Army Soldiers, 1980-2000. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004 Feb;130(2):164-70. PMID: 14990911. [CrossRef]

- Hwang K, You S, Sohn I. Analysis of orbital bone fractures. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20(4):1218-23. [CrossRef]

- Roh JH, Jung JW, Chi M. A clinical analysis of bilateral orbital fracture. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(2):388–392. [CrossRef]

- Almousa R, Amrith S, Mani AH, Liang S, Sundar G. Radiological signs of periorbital trauma – the Singapore experience. Orbit. 2010;29(6):307–312. [CrossRef]

- Jank S, Schuchter B, Emshoff R, Strobl H, Koehler J, Nicasi A, Norer B, Baldissera I. Clinical signs of orbital wall fractures as a function of anatomic location. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003 Aug;96(2):149-53. PMID: 12931086. [CrossRef]

- Schaller A, Huempfner-Hierl H, Hemprich A, Hierl T. Biomechanical mechanisms of orbital wall fractures - a transient finite element analysis. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013 Dec;41(8):710-7. Epub 2012 Mar 13. PMID: 22417768. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).