Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

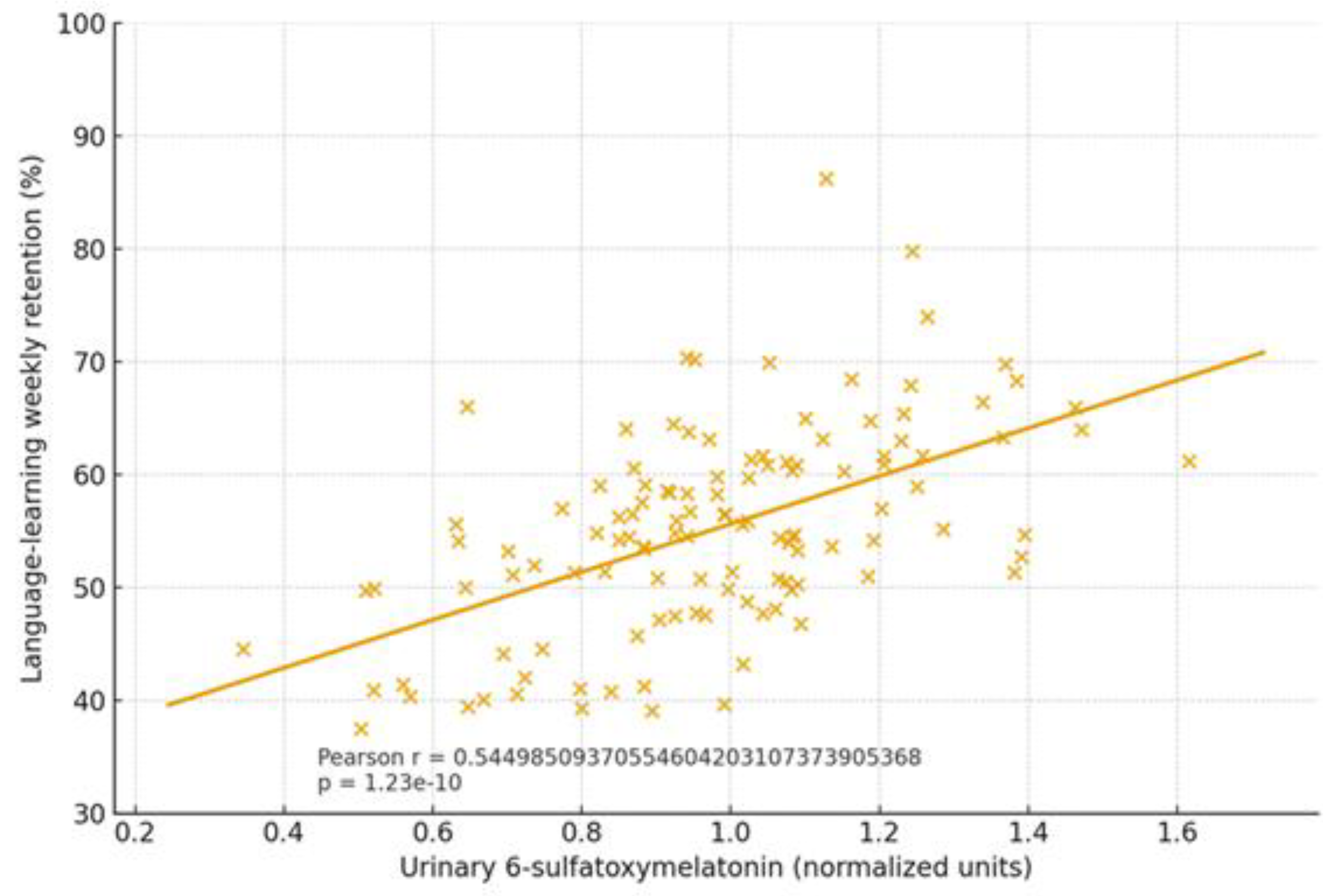

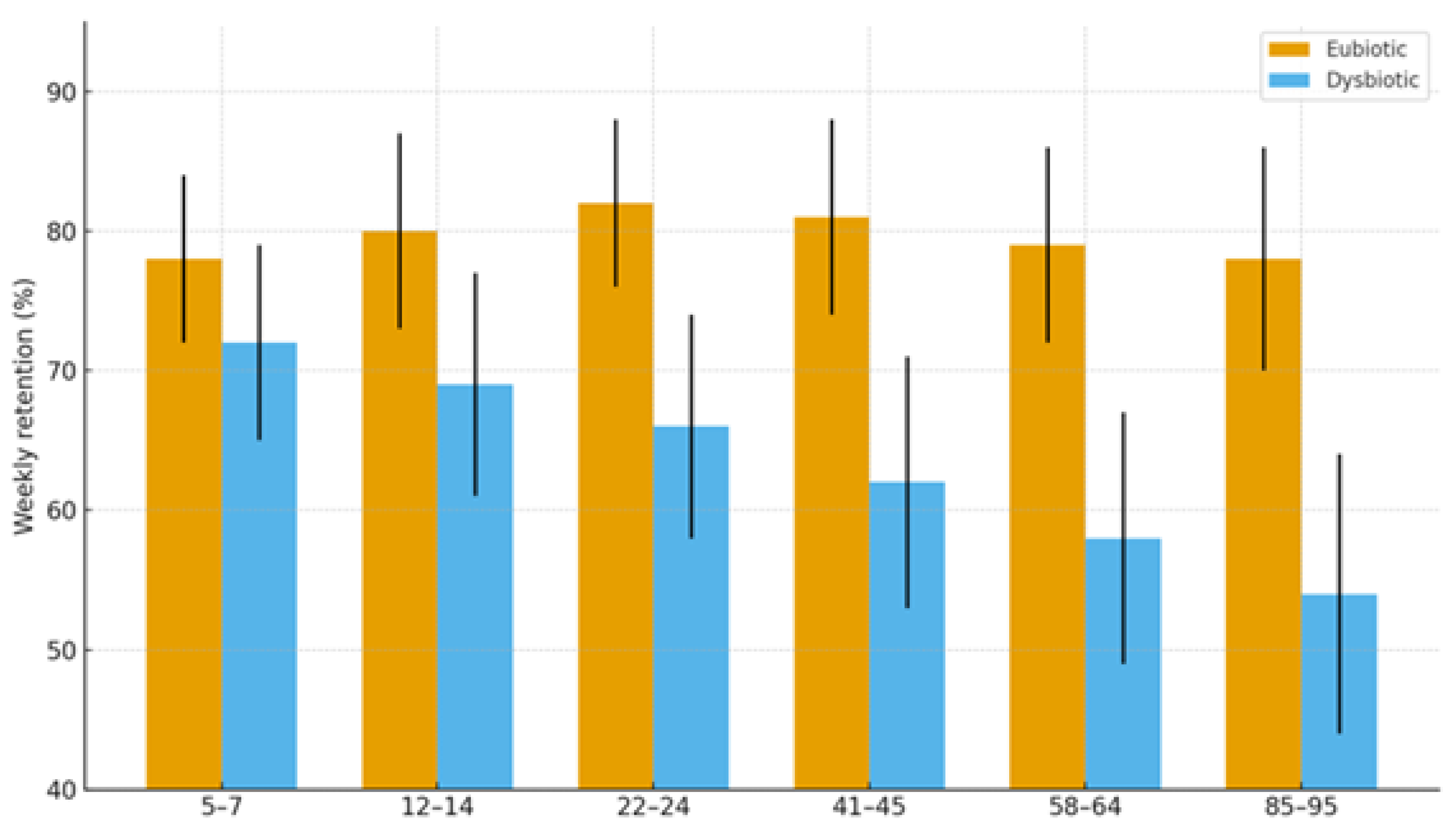

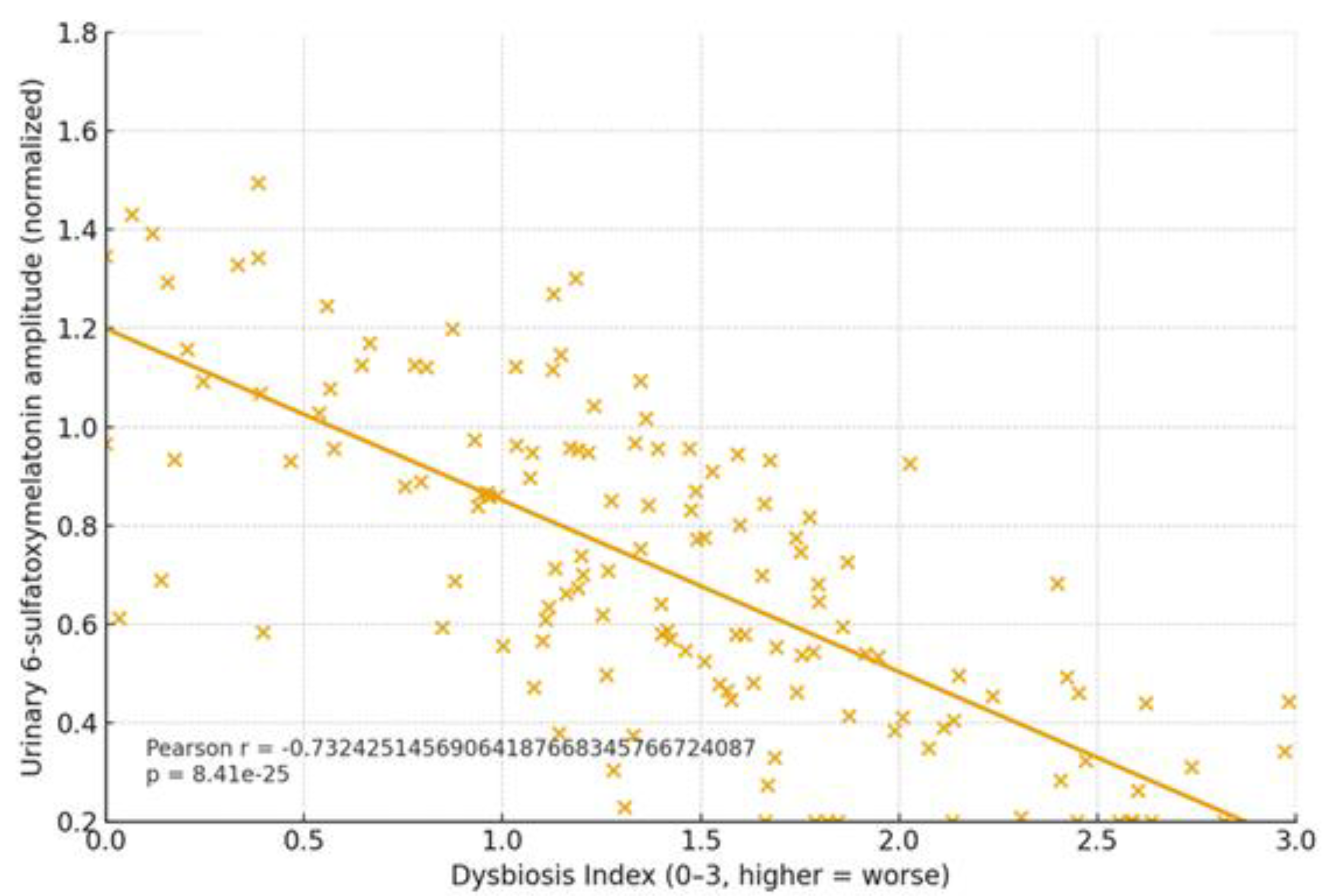

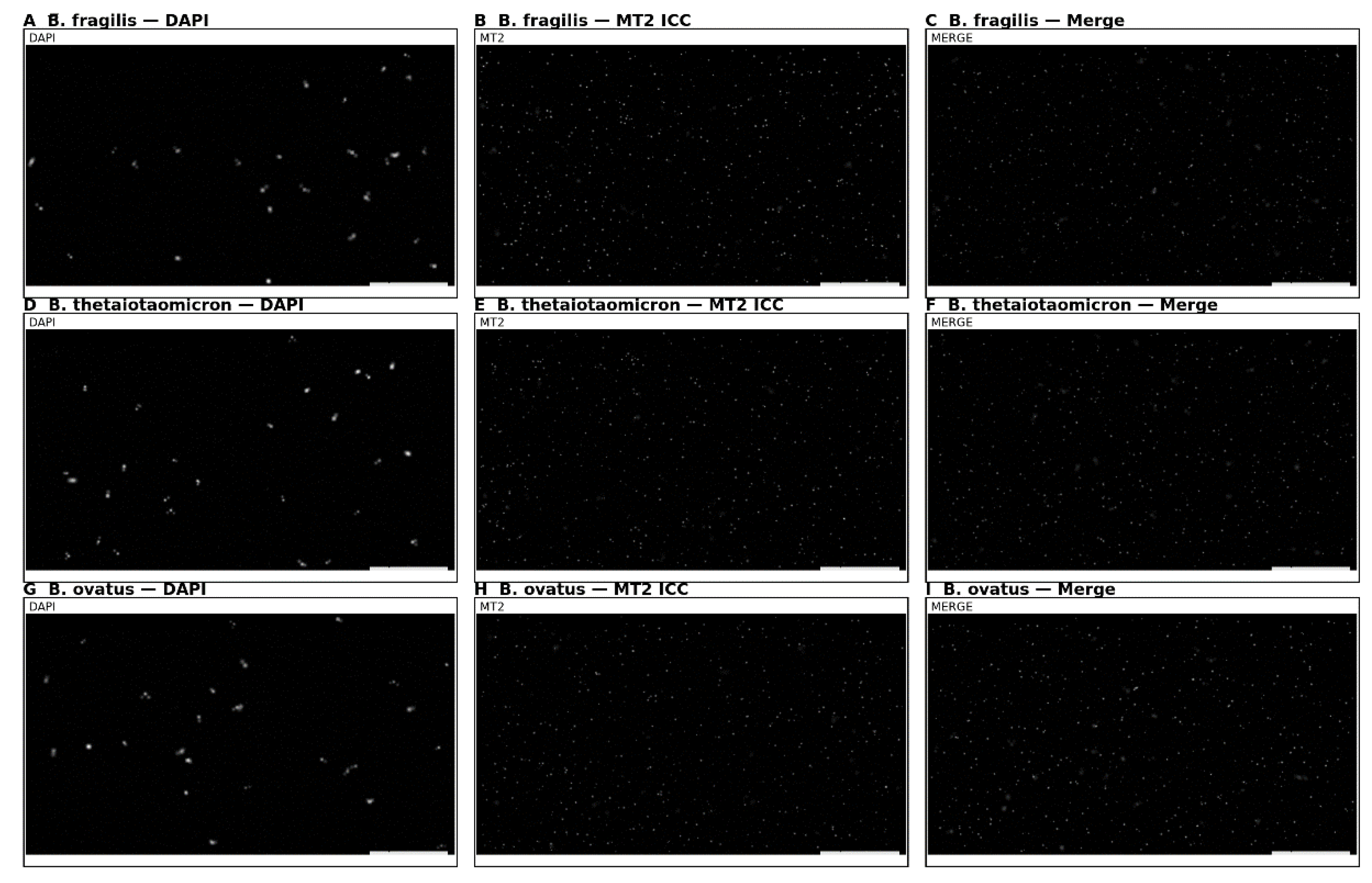

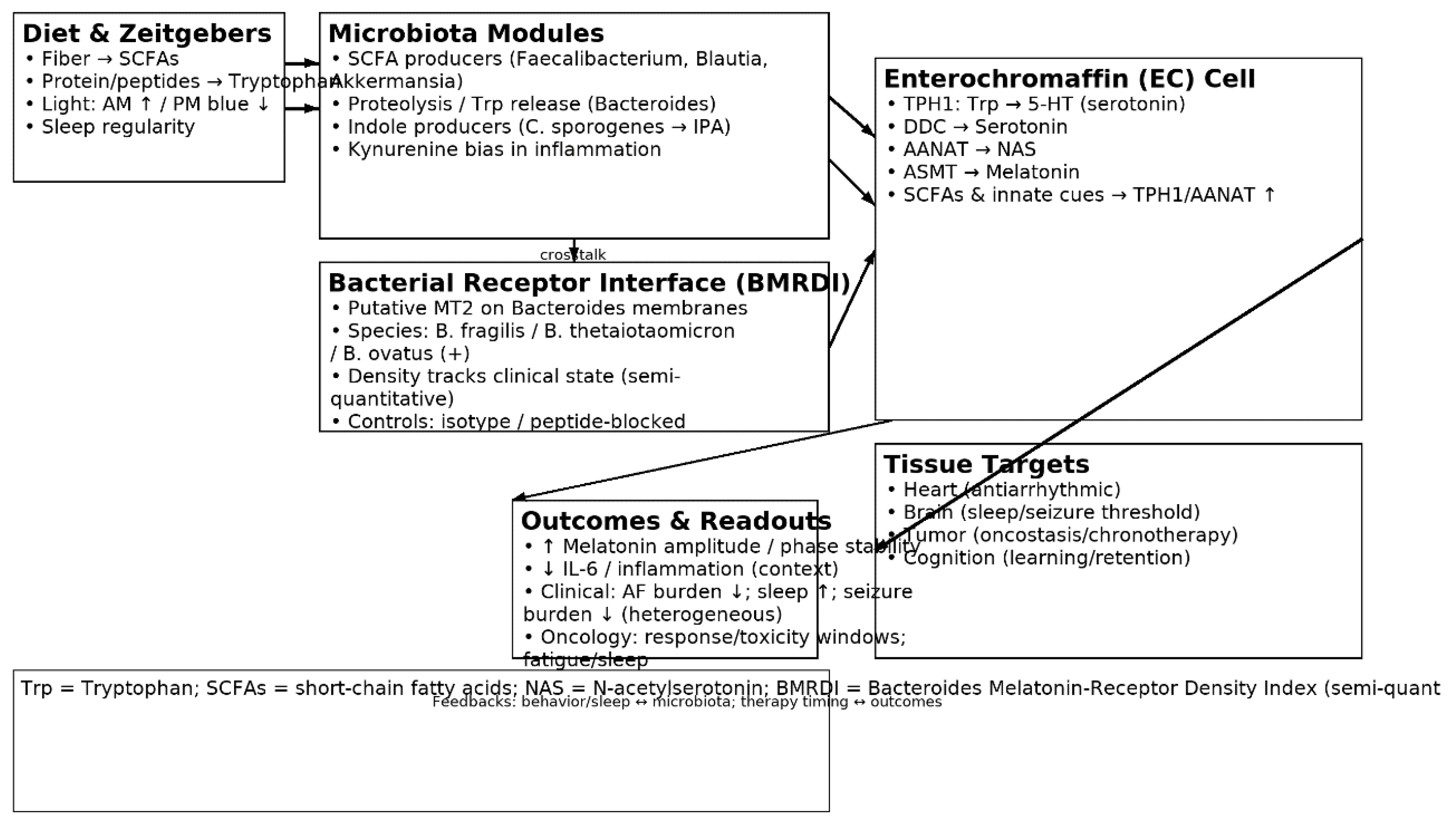

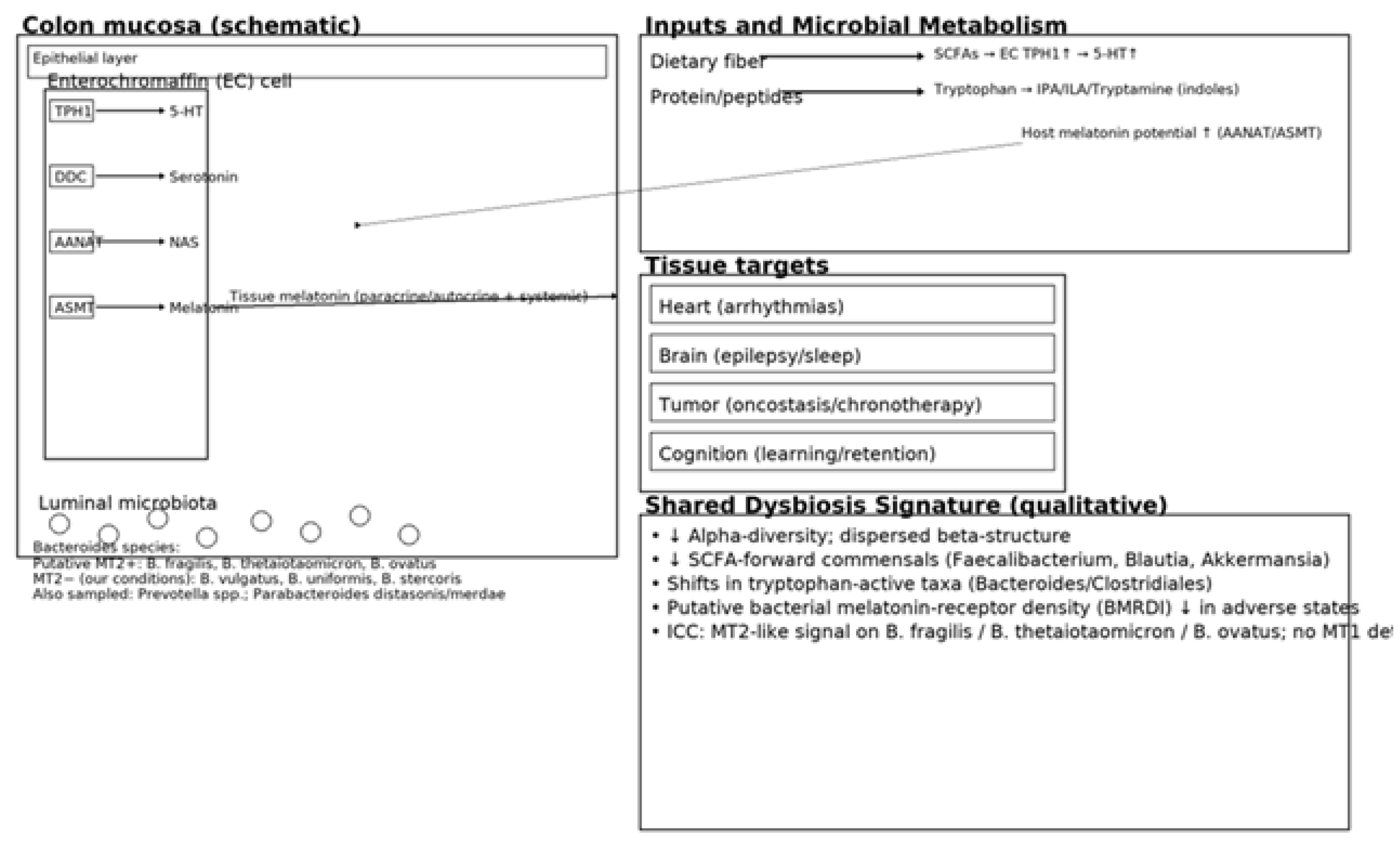

Background: Melatonin, an indolic neuromodulator with oncostatic and anti-inflammatory properties, is produced at extrapineal sites—most notably in the gut. Its canonical actions are mediated by high-affinity GPCRs (MT1/MT2) and by the melatonin-binding enzyme NQO2 (historically “MT3”). A growing body of work highlights a bidirectional interaction between the gut microbiota and host melatonin. Methods: We integrate two lines of work: (i) three clinical cohorts—cardiac arrhythmias (n = 111; 46–75 y), epilepsy (n = 77; 20–59 y), and stage III–IV solid cancers (25–79 y)—profiled with stool 16S rRNA sequencing, SCFA measurements, and circulating melatonin/urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin; and (ii) an age-spanning cognitive cohort with melatonin phenotyping, microbiome analyses, and exploratory immune/metabolite readouts, including a novel observation of melatonin binding on bacterial membranes. Results: Across all three disease cohorts we observed moderate-to-severe dysbiosis with reduced alpha-diversity and shifted beta-structure. The core dysbiosis implicated tryptophan-active taxa (Bacteroides/Clostridiales proteolysis and indolic conversions) and depletion of SCFA-forward commensals (e.g., Faecalibacterium, Blautia, Akkermansia, several Lactobacillus/Bifidobacterium spp.). Synthesized literature indicates that typical human gut commensals rarely secrete measurable melatonin in vitro; rather, their metabolites (SCFAs, lactate, tryptophan derivatives) regulate host enterochromaffin serotonin/melatonin production. In arrhythmia models, dysbiosis, bile-acid remodeling, and autonomic/inflammatory tone align with melatonin-sensitive antiarrhythmic effects. Epilepsy exhibits circadian seizure patterns and tryptophan-metabolite signatures, with modest and heterogeneous responses to add-on melatonin. Cancer cohorts show broader dysbiosis consistent with melatonin’s oncostatic actions. In the cognitive cohort, the absence of dysbiosis tracked with preserved learning across ages; exploratory immunohistochemistry suggested melatonin-binding sites on bacterial membranes in ~15–17% of samples. Conclusions: A unifying microbiota–tryptophan–melatonin axis plausibly integrates circadian, electrophysiologic, and immune–oncologic phenotypes. Practical levers include fiber-rich diets (to drive SCFAs), light hygiene, and time-aware therapy, with indication-specific use of melatonin.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Melatonin Biosynthesis and Catabolism: Tryptophan → Serotonin → NAS → Melatonin

| Enzyme | Full name | Step | Primary tissue | Key regulation | Clinical relevance | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPH1 | Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 | Trp → 5-HTP | EC cells (gut) | ↑ by SCFAs/MyD88 | Gatekeeper for serotonin | [5],[6],[7] |

| DDC | Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase | 5-HTP → Serotonin | EC/widespread | Substrate-driven | Serotonin conversion | [1],[2] |

| AANAT | Arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase | Serotonin → NAS | Pineal & gut | Often rate-limiting; ↑ innate cues | Flux into melatonin | [7],[9] |

| ASMT | Acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase | NAS → Melatonin | Pineal & gut | Substrate-dependent | Final step | [1],[2] |

| Receptor/Site | Class | Signaling | Distribution (selected) | Implications | Refs |

| MT1 (MTNR1A) | GPCR (Gi/o) | ↓cAMP; MAPK/ERK; PLC/Ca²⁺; PI3K/Akt | Neuro/endocrine/cardiovascular | Sleep/circadian; neuromodulation | [10],[11] |

| MT2 (MTNR1B) | GPCR (Gi/o; cGMP links) | ↓cAMP; cGMP; MAPK; PI3K/Akt | Vasculature; LV; retina; brain | Cardioprotection; chronobiology | [16],[18] |

| NQO2 (“MT3”) | Quinone reductase 2 (binding site) | Redox enzyme; melatonin-binding | Widely expressed | Non-GPCR interactions | [14],[15] |

1.2. Receptors and Signaling: MT1/MT2 and NQO2 (“MT3”)

1.3. The Microbiota–Tryptophan–Melatonin Axis

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Focus: Three Target Pathologies + Cognitive Trajectories

2.1.1. Cardiac Arrhythmias

2.1.2. Epilepsy

2.1.3. Malignant Proliferation (Stage III–IV)

2.1.4. Cognitive Trajectories (Companion Cohort; Age-Spanning)

2.2. Results

3. Discussion

3.1. Interpretation: An Integrative Biological Model

3.2. Practical Implications

3.3. Limitations

4. Materials and Methods (Unified, “Classically Accepted” Frame)

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

References

- Acuña-Castroviejo D, et al. Extrapineal melatonin: sources, regulation, and potential functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71(16):2997–3025. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Chen CQ, et al. Distribution, function and physiological role of melatonin in the lower gut. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17(34):3888–3898. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann P, et al. Microbial melatonin metabolism in the human intestine as a determinant of host melatonin levels. npj Biofilms Microbiomes. 2024;10:60. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Kennaway DJ. The mammalian gastro-intestinal tract is NOT a major extra-pineal source of melatonin. J Pineal Res. 2023;75(4):e12906. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Reigstad CS, et al. Gut microbes promote colonic serotonin production through an effect of short-chain fatty acids on enterochromaffin cells. FASEB J. 2015;29(4):1395–1403. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Bellono NW, et al. Enterochromaffin cells are gut chemosensors that couple to sensory neural pathways. Cell. 2017;170(1):185–198.e16. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Liu B, et al. Gut microbiota regulates host melatonin production through epithelial cell MyD88. Gut Microbes. 2024;16(1):2313769. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Iesanu MI, et al. Melatonin–Microbiome two-sided interaction in dysbiosis-associated conditions. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11(11):2244. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Xie X, et al. Melatonin biosynthesis pathways in nature and its biological functions. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2022;119:1–14. **PMID:**35087957. PubMed.

- Liu J, et al. MT1 and MT2 melatonin receptors: a therapeutic perspective. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;56:361–383.

- Okamoto HH, et al. Melatonin receptor structure and signaling. J Pineal Res. 2024;76(3):e12952. [CrossRef]

- Zheng J, et al. Intestinal melatonin levels and gut microbiota homeostasis are independent of the pineal gland in pigs. Front Microbiol. 2024;15:1352586. [CrossRef]

- Kennaway DJ, et al. 6-Sulfatoxymelatonin as a circadian biomarker: synthesis, metabolism, and measurement. J Pineal Res. (overviewed in Ref. 4).

- Mailliet F, et al. Organs from NQO2-deleted mice lack MT3 melatonin binding. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:277–287.

- Boutin JA. Melatonin: facts, extrapolations and clinical trials—MT3 equals NQO2. Biomolecules. 2023;13:943.

- Ekmekcioglu C, et al. The melatonin receptor subtype MT2 is present in the human cardiovascular system. J Pineal Res. 2003;35(1):40–44. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- García-Iglesias A; Segovia-Roldán M, et al. Cardioprotection by melatonin in ischemia–reperfusion. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:764.

- Lecacheur M, et al. Circadian rhythms in cardiovascular (dys)function. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2024;21:607–626. Nature. [CrossRef]

- Jiao J, et al. Melatonin-producing endophytic bacteria from grapevine roots. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1387. [CrossRef]

- Kwon EH, et al. Novel melatonin-producing Bacillus safensis EH143. J Pineal Res. 2024;76:e12957.

- Gamalero E, et al. How melatonin affects plant growth and associated microbiota. Biology. 2025;14:371. [CrossRef]

- Gibson SAW, Macfarlane GT. Studies on the proteolytic activity of Bacteroides fragilis. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134(1):19–27. microbiologyresearch.org+1. [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni BS, et al. Characterization of a secreted aminopeptidase of M28 family from B. fragilis (BfAP). BBA-Gen. 2024;1868:130598. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Du L, et al. Indole-3-propionic acid, a functional metabolite of Clostridium sporogenes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(22):12435. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Krause FF, et al. C. sporogenes-derived metabolites protect against colonic inflammation. Gut Microbes. 2024;16(1):2412669. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Wang Z, et al. The gut microbiota-derived metabolite IPA regulates energy balance. Clin Transl Med. 2024;14:e70053. Wiley Online Library+1. [CrossRef]

- Jiang J, et al. The gut metabolite IPA activates ERK1 to ameliorate neurobehavioral deficits. Microbiome. 2024;12:155. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Sinha AK, et al. Dietary fibre directs microbial tryptophan metabolism. Nat Microbiol. 2024;9:1410–1422. [CrossRef]

- Jensen BT, et al. Beat-to-beat QT dynamics in healthy subjects. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2004;9(1):3–11. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Al-Kaisey AM, et al. Gut microbiota and atrial fibrillation: pathogenesis, mechanisms and therapies. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2023;12:e14. PubMed. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, et al. The gut microbiota–bile acid–arrhythmia axis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1330826.

- Dai H, et al. Mendelian randomization analysis of gut microbiota and AF. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22:204.

- Slabeva K, et al. Timing mechanisms for circadian seizures. Clocks & Sleep. 2024;6:40. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Yang W, et al. Microbiota–gut–brain axis in epilepsy. Transl Neurosci. 2024; (review).

- Tang T, et al. Circadian rhythm and epilepsy. Front Neurol. 2024;15:1398178.

- Maghbooli M, et al. Melatonin add-on in generalized epilepsy (clinical trial). 2022.

- Routy B, et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy. Science. 2018;359(6371):91–97. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Gopalakrishnan V, et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma. Science. 2018;359(6371):97–103. PubMed+1. [CrossRef]

- Garrett WS. The gut microbiota and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23:321–345.

- Reiter RJ, et al. Melatonin as an oncostatic agent: mechanisms and chronotherapy. Cancers (Basel). 2017;9(1):14.

- Ethics.

- Approved by IRB #CN-2021-11 and #TX-UT-2021-08; all patients provided written informed consent.

| Taxon/Module | Mechanistic role | Shift in dysbiosis | Markers | Clinical links | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacteroides fragilis (proteolysis) | Liberates Trp from peptides → indoles | Variable; often ↓ function | M28 aminopeptidase; Trp ↑ | EC serotonin/melatonin; immune | [22],[23] |

| Clostridium sporogenes (IPA) | Trp → IPA (indole-3-propionic acid) | ↓ in dysbiosis | IPA | Barrier/immune tuning | [24],[25] |

| Faecalibacterium (butyrate) | SCFAs ↑ TPH1; barrier integrity | ↓ | Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory; rhythm support | [5],[28] |

| Blautia (SCFA) | SCFA pool; BA crosstalk | ↓ | Acetate/Butyrate | Sleep/metabolic links | [8] |

| Akkermansia (mucin) | Mucus remodeling; SCFA/bile acid interplay | ↓ (context) | Acetate/propionate | Barrier; immunotherapy links | [37],[39] |

| Lactobacillus spp. | Organic acids; Trp crosstalk | ↓ (heterogeneous) | Lactate; GABA; Trp derivatives | Sleep/circadian; seizures (context) | [6],[8] |

| Bifidobacterium spp. | Trp/indole correlations; SCFAs | ↓ | Acetate; folate | Melatonin signaling; cognition | [23] |

| SCFA module | ↑EC TPH1 → ↑5-HT → ↑melatonin | ↓ | Acetate/propionate/butyrate | Antiarrhythmic/sleep/oncostatic support | [5],[8] |

| Indole module | Indolic signaling (IPA/ILA/tryptamine) | ↓ IPA/ILA | IPA/ILA/tryptamine | Barrier/neuroimmune | [24],[25],[27] |

| Kynurenine module | Trp diversion → kynurenines | ↑ (inflammation) | Kynurenine; QA/3-HK | Neuroinflammation; tumor milieu | [34],[39] |

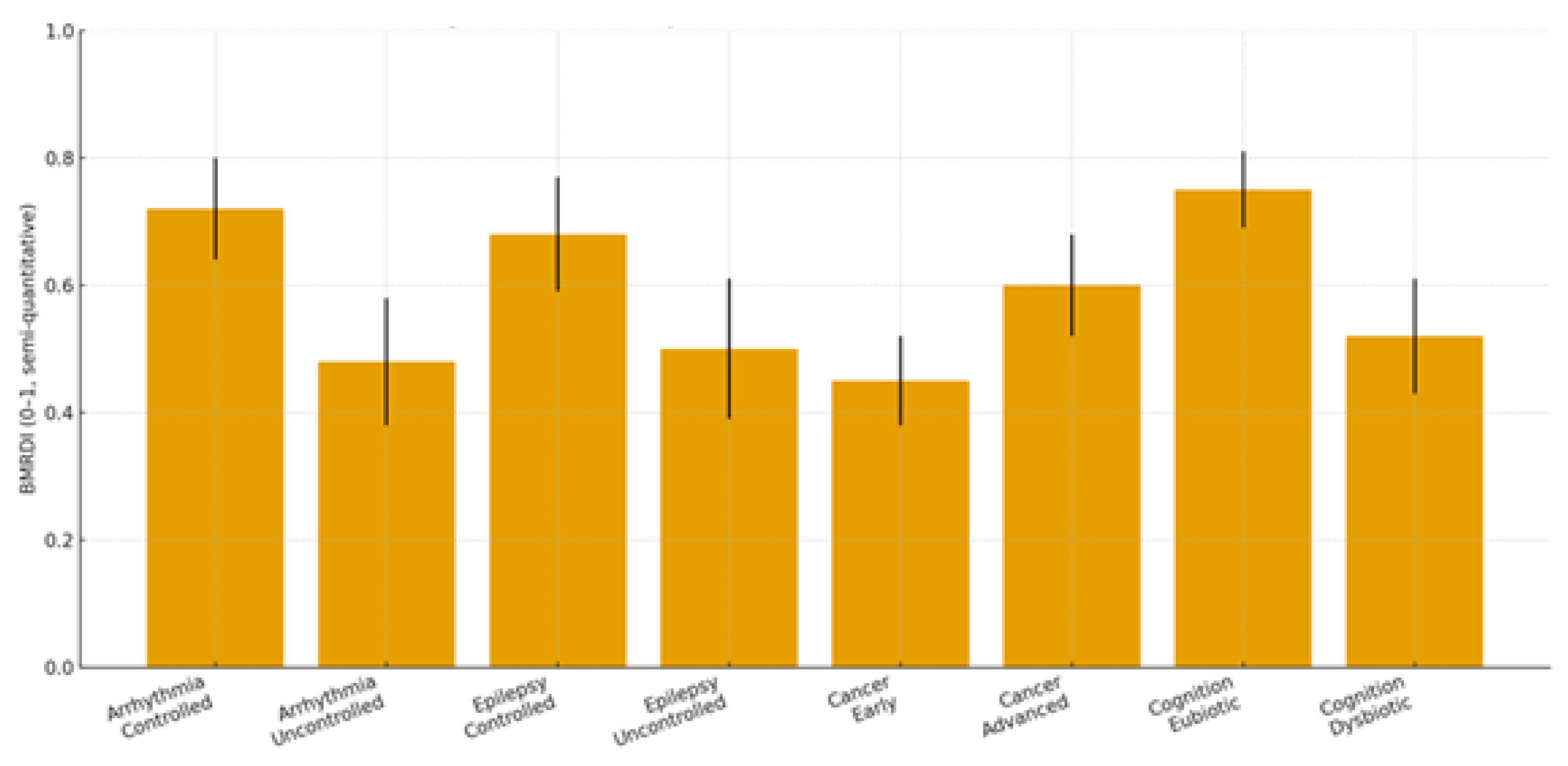

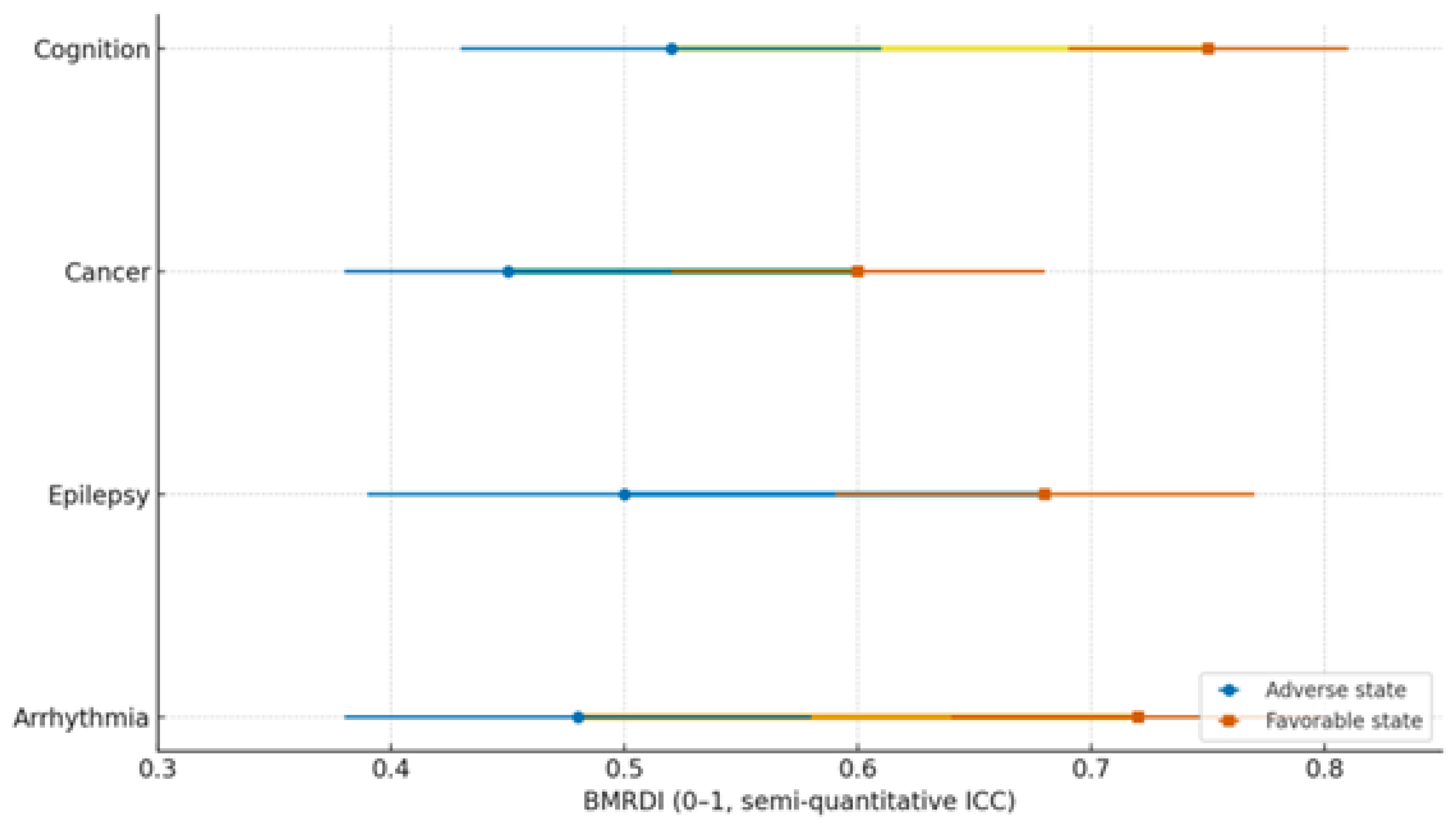

| Condition | Dysbiosis signature | Trp/SCFA/Indole markers | Melatonin readouts | Primary endpoints | Proposed BMRDI behavior | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrhythmias | ↓α-div.; ↓SCFAs; BA remodeling | ↓Butyrate; ↓IPA | ↓6-sulfatoxymelatonin amplitude; phase variability | AF burden/class; HRV; QT dynamics | BMRDI higher in controlled; lower uncontrolled | [30],[31],[18],[5] |

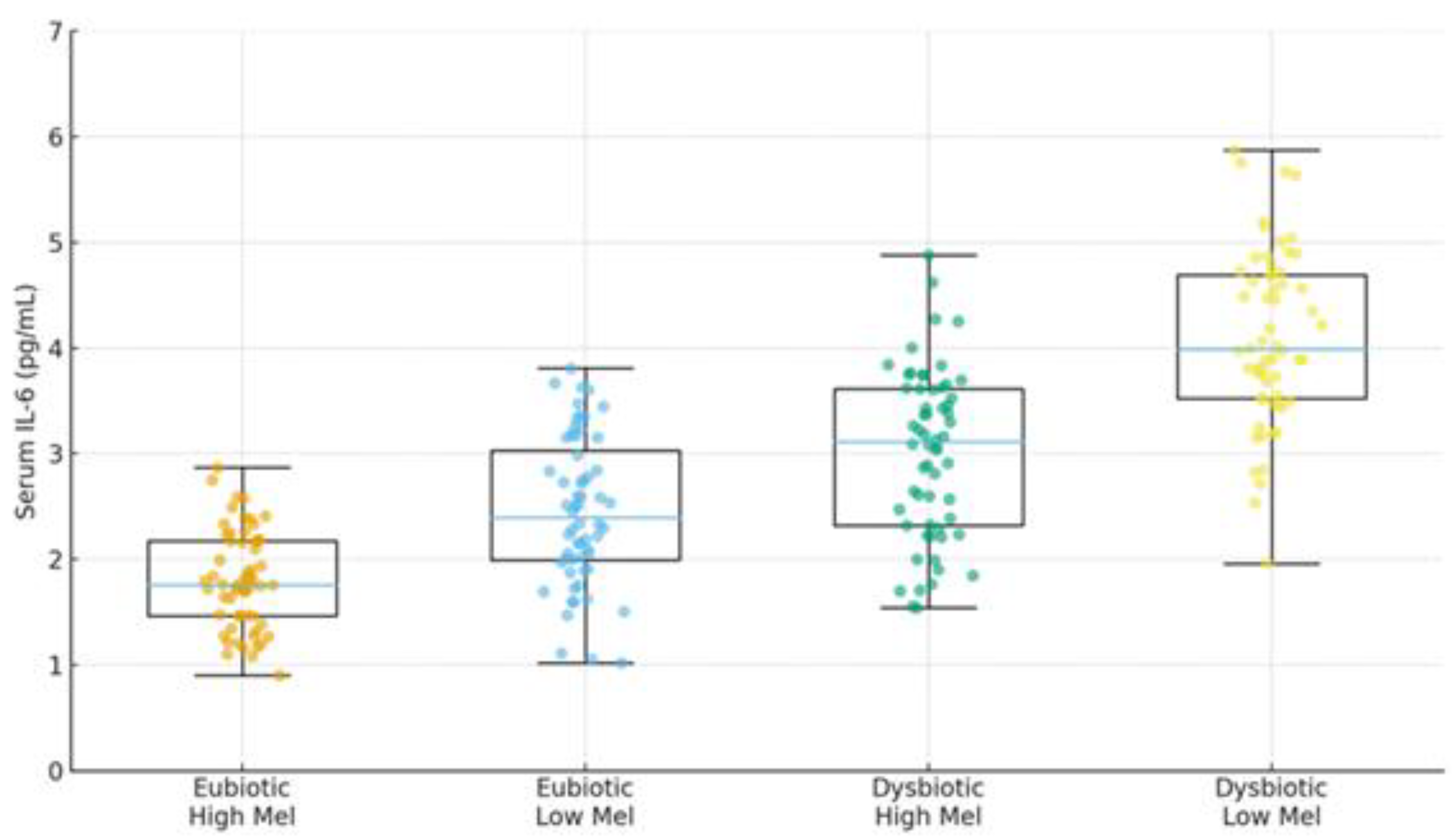

| Epilepsy | ↓SCFAs; Trp shifts; ↑kynurenine bias | ↓IPA/ILA; variable tryptamine | ↓amplitude; irregular timing; melatonin add-on → sleep ↑ (p<0.005) | Seizure frequency; nocturnal clustering; sleep | BMRDI higher with seizure control | [33],[35],[34],[6] |

| Cancer (III–IV) | Profound ↓α-div.; SCFA deficits; Trp/indole depletion | ↓IPA; ↓butyrate; BA/immune remodeling | ↓baseline or fragmented; oncostatic/chronotherapy roles | Response/toxicity; IL-6; fatigue/sleep | Descriptively higher in advanced vs early | [37],[39],[40] |

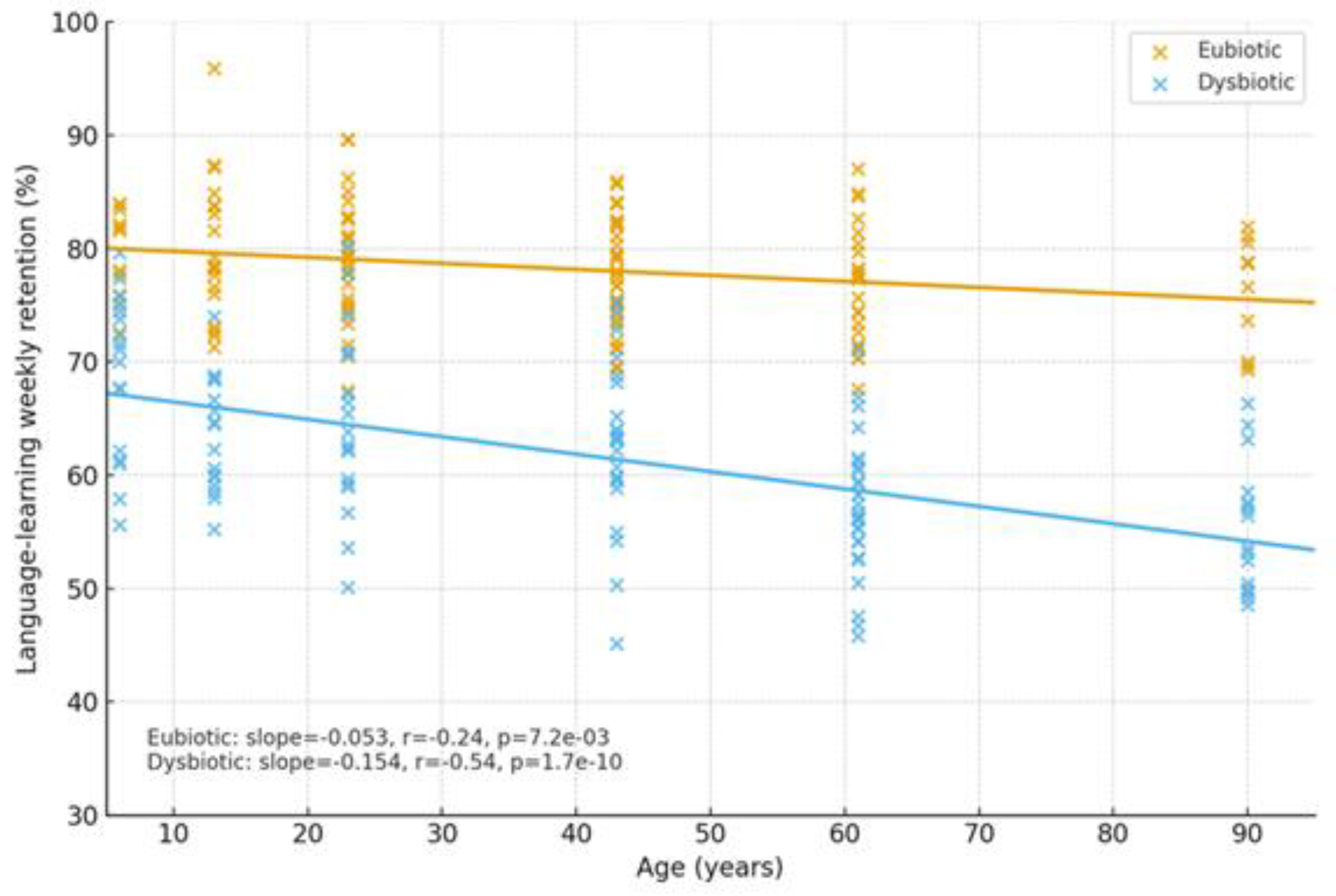

| Cognition | Dysbiosis ↔ age-related decline; eubiosis preserves | SCFA tone; Trp→melatonin support | Normal rhythms in eubiosis; irregular in dysbiosis | Language retention; attention | Higher in eubiotic learners | [41],[5] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).