Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

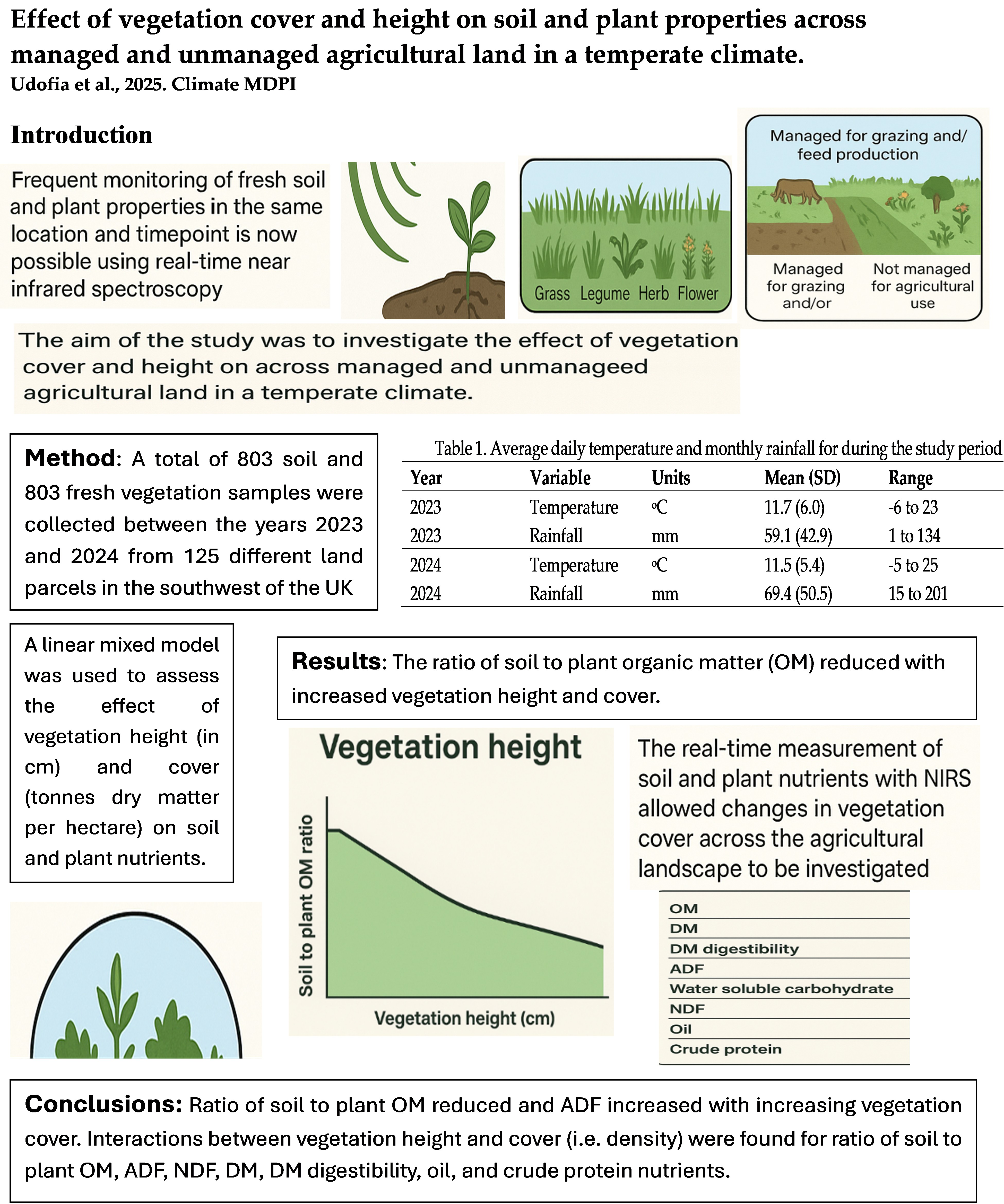

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Field Data

2.2. Samples and Field Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of Vegetation Cover and Height on Plant Nutrients

3.2. Effect of Vegetation Cover and Height on Soil Nutrients

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NIRS | Near infrared spectroscopy |

| Uk | United Kingdom |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| OM | Organic matter |

| N | Total nitrogen |

| DM | Dry matter |

| ADF | Acid detergent fibre |

| NDF | Neutral detergent fibre |

| DMD | Dry matter digestibility |

| FW | Fresh Weight |

References

- Udofia, S.O.U.; Williams, L.K.; Wills, A.P.; Bell, M.J. Importance of Vegetation Cover in Organic Systems. In Advances in Organic Farming; GB: CABI, 2025; pp. 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornara, D.A.; Tilman, D. Plant functional composition influences rates of soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation. J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Van der Putten, W.H. Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nat. 2014, 515, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neina, D. The role of soil pH in plant nutrition and soil biota activity: A review. Soil syst. 2019, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Six, J.; Bossuyt, H.; Degryze, S.; Denef, K. A history of research on the link between (micro) aggregates, soil biota, and soil organic matter dynamics. Soil Till Res. 2004, 79, 7–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentsch, N.; Kaiser, M.; Mikutta, R.; et al. Cover crops improve soil structure and change organic carbon distribution in macroaggregate fractions. Soil 2024, 10, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisec, T.; Šibanc, N.; Lojen, S.; Vidrih, T. Sustainable grassland-management systems affect soil physicochemical properties and forage nutritional quality. Plants 2024, 13, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; Reich, P.B.; Knops, J.M.H. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability in a decade-long grassland experiment. Nat. 2001, 441, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crosse, S.; O’Donovan, M.; Delaby, L.; Boland, T.M. Quantifying the effect of sward characteristics on the nutritive value of grass herbage. Grass Forage Sci. 2015, 70, 364–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.J.; Mereu, L.; Davis, J. The use of mobile near-infrared spectroscopy for real-time pasture management. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 2, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinermann, S.; Rathmann, J.; Lüker-Jans, N.; Schmidtlein, S. Grassland yield estimations – potentials and limitations of remote sensing. BG 2025, 22, 4969–4983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzluebbers, A.J. Soil organic matter stratification ratio as an indicator of soil quality. Soil Till Res. 2002, 66, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, R.J.; Higgs, E.; Harris, J.A. Novel ecosystems: implications for conservation and restoration. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2008, 24, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH). Less intensively managed grasslands have higher plant diversity and better soil health. UKCEH website, 2022. Available online: https://www.ceh.ac.uk/press/less-intensively-managed-grasslands-havehigher-plant-diversity-and-better-soil-health.

- Jerrentrup, J.S.; Wrage-Mönnig, N.; Röver, K.U.; Isselstein, J. Grazing with different livestock species affects the plant and insect diversity of species-rich grasslands. Agr Ecosyst Environ 2020, 287, 106679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibon, A. Managing grassland for production, the environment and the landscape. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2005, 96, 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batello, C.; Mannetje, L.; Martinez, A.; Suttie, J. Plant genetic resources of forage crops, pasture and rangelands. Thematic background study. FAO report 2008, 5-7. Available online: https://www.fao.org/fileadmin/templates/agphome/documents/PGR/SoW2/thematicstudy_forage.pdf.

- Wilkins, P.W.; Humphreys, M.O. Progress in breeding perennial forage grasses for temperate agriculture. J. Agric. Sci. 2003, 140, 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrage, N.; Strodthoff, J.; Cuchillo, H.M.; Isselstein, J.; Kayser, M. Phytodiversity of temperate permanent grasslands: ecosystem services for agriculture and livestock management for diversity conservation. Biodivers. Conserv. 2011, 20, 3317–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.J.; J Huggett, Z.; Slinger, K.R.; Roos, F. Effect of pasture cover and height on nutrient concentrations in diverse swards in the UK. Grassl Sci. 2021, 67, 267–272. [CrossRef]

- Mainetti, A.; Ravetto Enri, S.; Pittarello, M.; Lombardi, G.; Lonati, M. Main ecological and environmental factors affecting forage yield and quality in Alpine summer pastures (NW-Italy, Gran Paradiso National Park). Grass Forage Sci. 2023, 78, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Gunina, A.; Cheng, H.; Liu, L.; Wang, B.; Dou, Y. .; Chang, S.X. Unlocking mechanisms for soil organic matter accumulation: carbon use efficiency and microbial necromass as the keys. Glob Chang Biol. 2025, 31, e70033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y. Vegetation structure regulates soil nutrient dynamics in grassland ecosystems under changing climates. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 61, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil carbon sequestration impacts on global climate change and food security. Sci. 2004, 304, 1623–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousk, J.; Bååth, E.; Brookes, P.C.; Lauber, C.L.; Lozupone, C.; Caporaso, J.G. ..; Fierer, N. Soil bacterial and fungal communities across a pH gradient in an arable soil. ISME J. 2010, 4, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wardle, D.A.; Bardgett, R.D.; Klironomos, J.N.; Setala, H.; Van Der Putten, W.H.; Wall, D.H. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Sci. 2004, 304, 1629–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, P.; Bentley, L.; Danks, P.; Emmett, B.; Garbutt, A.; Heming, S. .; Wickenden, A. The effects of land use on soil carbon stocks in the UK. BG 2024, 21, 4301–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.J.; Shepherd, K.D.; Walsh, M.G.; Mays, M.D.; Reinsch, T.G. Global soil characterization with VNIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Geoderma 2018, 144, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitousek, P.M.; Menge, D.N.L.; Reed, S.C.; Cleveland, C.C. Biological nitrogen fixation: rates, patterns and ecological controls in terrestrial ecosystems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B, Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 1215–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Zou, M.; Chen, J.; Hou, F. Grazing management of cultivated grassland with different weed proportions optimizes soil nutrient status and improves forage yield and nutritional quality. Field Crops Res. 2025, 331, 110018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Variable | Units | Mean (SD) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | Temperature | oC | 11.7 (6.0) | -6 to 23 |

| 2023 | Rainfall | mm | 59.1 (42.9) | 1 to 134 |

| 2024 | Temperature | oC | 11.5 (5.4) | -5 to 25 |

| 2024 | Rainfall | mm | 69.4 (50.5) | 15 to 201 |

| Variable | Units | Mean (SD) | Range | Coefficient of variation (%) |

| Vegetation properties | ||||

| Height | cm | 8.7 (6.1) | 1.0–24.6 | 71 |

| Fresh weight cover | t FW/ha | 10.4 (9.4) | 0.7–54.6 | 90 |

| Dry matter | g/kg | |||

| Dry matter cover | t DM/ha | 2.8 (3.1) | 0.2–17.2 | 110 |

| Fresh density | t FW/ha/cm | 13.8 (10.9) | 0.9–51.7 | 79 |

| Dry density | t DM/ha/cm | 4.1 (3.6) | 0.2–13.6 | 87 |

| Crude protein | g/kg DM | 194.3(64.8) | 10.0-320.1 | 33 |

| Acid detergent fibre | g/kg DM | 259.9(33.1) | 152.0-350.7 | 13 |

| Neutral detergent fibre | g/kg DM | 479.1(136.1) | 305.2-990.0 | 28 |

| Water soluble carbohydrates | g/kg DM | 90.1(41.8) | 0.0-166.1 | 46 |

| Ash | g/kg DM | 91.7(14.9) | 20.2-123.5 | 16 |

| Dry matter digestibility | g/kg DM | 717.0(61.6) | 514.7-811.3 | 9 |

| Oil | g/kg DM | 18.8(4.8) | 3.5-25.5 | 26 |

| Soil properties | ||||

| Organic matter | g/kg | 29.5 (13.5) | 11–125 | 46 |

| Organic matter | t /ha | 61.2 (25.3) | 14.5-254.4 | 41 |

| Total nitrogen | g/kg | 2.8 (1.1) | 1.2–9.2 | 40 |

| Total nitrogen | t/ha | 5.2 (1.4) | 2.4 - 9.9 | 27 |

| Clay | % | 21.3 (5.8) | 7.0–38 | 27 |

| Moisture | % | 23.5 (6.7) | 0.4–52.5 | 28 |

| pH | 6.9 (0.3) | 5.9-7.8 | 5 | |

| Bulk density | g/cm3 | 0.73 (0.1) | 0.4-0.9 | 19 |

| Organic carbon: nitrogen1 | 10.6 (1.1) | 5.5–17.0 | 10 | |

| Organic matter: clay | 0.15 (0.1) | 0.03–1.04 | 66 | |

| Soil organic matter: plant organic matter | 52.9 (68.4) | 4.4-548.2 | 129 | |

| Effect | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Units | Height (cm) | Cover (t DM/ha) | Height × cover | Height (cm) | Cover (t DM/ha) | Height × cover |

| Dry matter | g/kg | -12.5 (3.1) | -13.2 (6.4) | 3.0 (0.5) | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.001 |

| Crude protein | g/kg DM | 1.4 (1.3) | 2.0 (2.6) | -0.8 (0.2) | 0.270 | 0.440 | <0.001 |

| Acid detergent fibre | g/kg DM | 3.9 (0.6) | 3.2 (1.3) | -0.5 (0.1) | <0.001 | <0.05 | <0.001 |

| Neutral detergent fibre | g/kg DM | -5.0 (2.3) | -5.1 (4.7) | 1.9 (0.3) | <0.05 | 0.282 | <0.001 |

| Water soluble carbohydrates | g/kg DM | 2.9 (0.8) | -2.8 (1.6) | -0.3 (0.1) | <0.001 | 0.080 | <0.05 |

| Ash | g/kg DM | -0.1 (0.4) | -0.04 (0.7) | -0.1 (0.1) | 0.769 | 0.958 | 0.334 |

| Dry matter digestibility | g/kg DM | 3.1 (1.1) | 1.3 (2.3) | -0.6 (0.2) | <0.01 | 0.555 | <0.001 |

| Oil | g/kg DM | 0.3 (0.1) | -0.1 (0.2) | -0.1 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.788 | <0.001 |

| Effect | P value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Units | Height (cm) | Cover (t DM/ha) | Height × cover | Height (cm) | Cover (t DM/ha) | Height × cover |

| Organic matter | g/kg | -0.4 (0.4) | 1.3 (0.8) | -0.1 (0.1) | 0.373 | 0.122 | 0.238 |

| Organic matter | t/ha | -0.7 (0.7) | 3.1 (1.5) | -0.2 (0.1) | 0.357 | <0.05 | 0.145 |

| Total nitrogen | g/kg | -0.03 (0.02) | 0.1 (0.04) | -0.003 (0.003) | 0.219 | 0.200 | 0.334 |

| Total nitrogen | t/ha | -0.05 (0.04) | 0.1 (0.1) | -0.01 (0.01) | 0.214 | 0.09 | 0.234 |

| Clay | % | -0.03 (0.1) | -0.1 (0.2) | -0.01 (0.01) | 0.741 | 0.763 | 0.692 |

| Moisture | % | -0.04 (0.2) | -0.01 (0.3) | -0.01 (0.02) | 0.824 | 0.975 | 0.692 |

| Bulk density | g/cm3 | 0.0001 (0.003) | -0.002 (0.01) | 0.00004 (0.0001) | 0.926 | 0.710 | 0.933 |

| pH | 0.0001 (0.01) | -0.03 (0.01) | 0.002 (0.001) | 0.957 | <0.05 | 0.051 | |

| Organic carbon to nitrogen ratio | 0.03 (0.02) | 0.06 (0.04) | -0.003 (0.002) | 0.137 | 0.084 | 0.294 | |

| Organic matter to clay ratio | -0.002 (0.002) | 0.003 (0.004) | 0.0001 (0.0001) | 0.194 | 0.383 | 0.446 | |

| Soil to plant organic matter ratio | -10.3 (1.3) | -19.6 (2.5) | 1.1 (0.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).