Submitted:

02 December 2025

Posted:

03 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

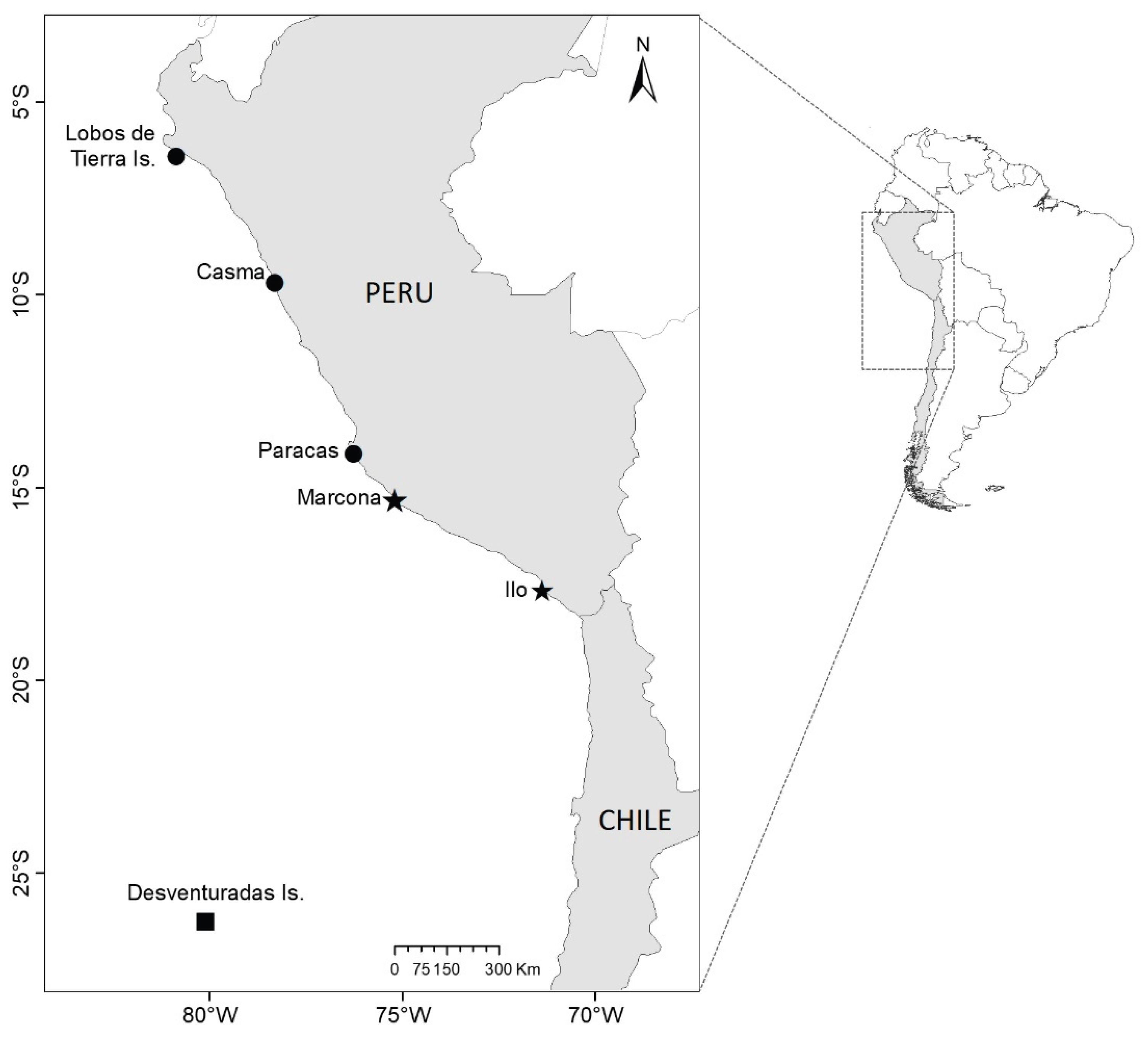

2.1. Sampling Sites and Collection

2.2. Phylogenetic Analyses

2.3. DNA-Based Species Delimitation Method with GMYC

3. Results

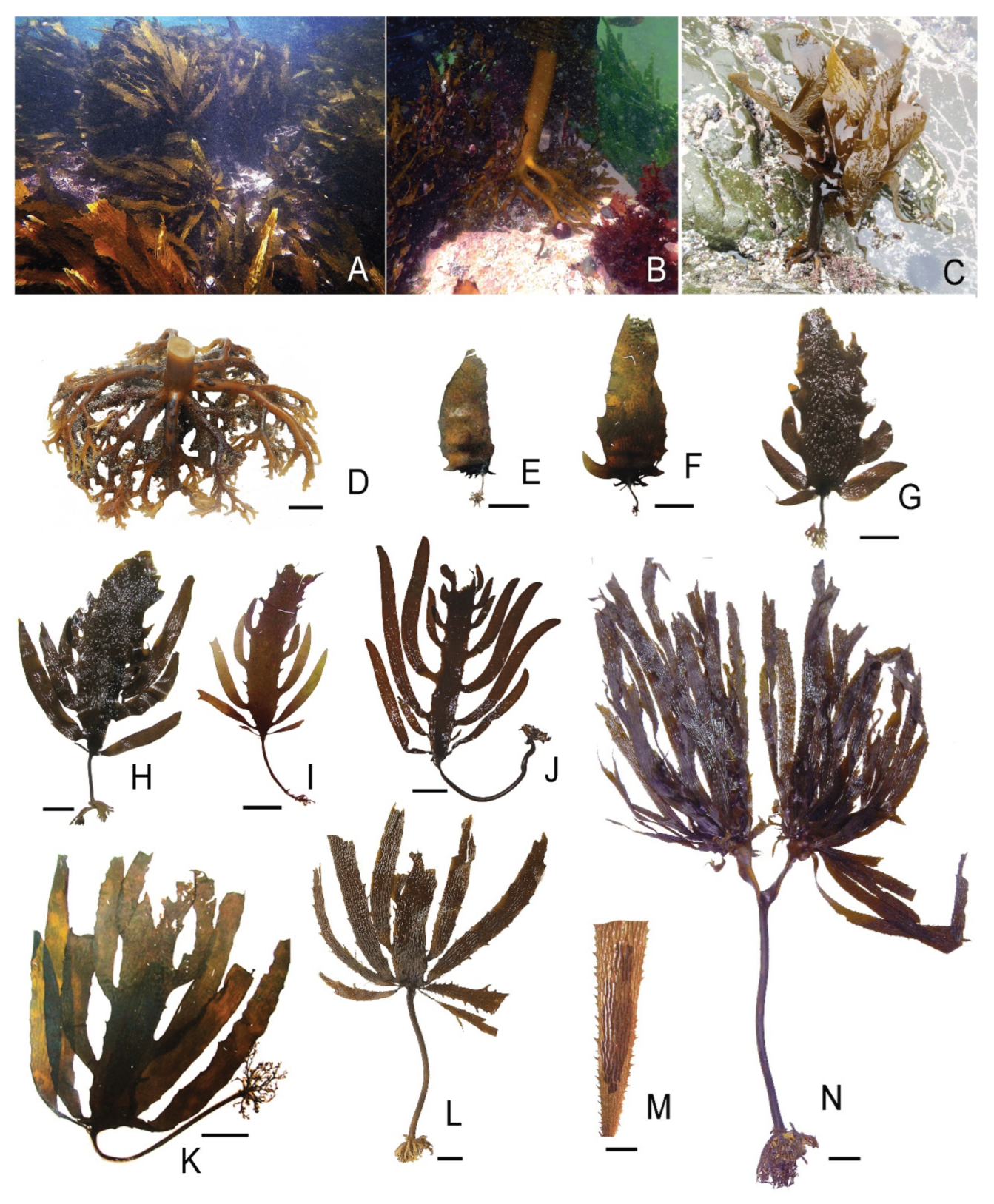

3.1. Morphological Observations

3.1.1. Eisenia cokeri

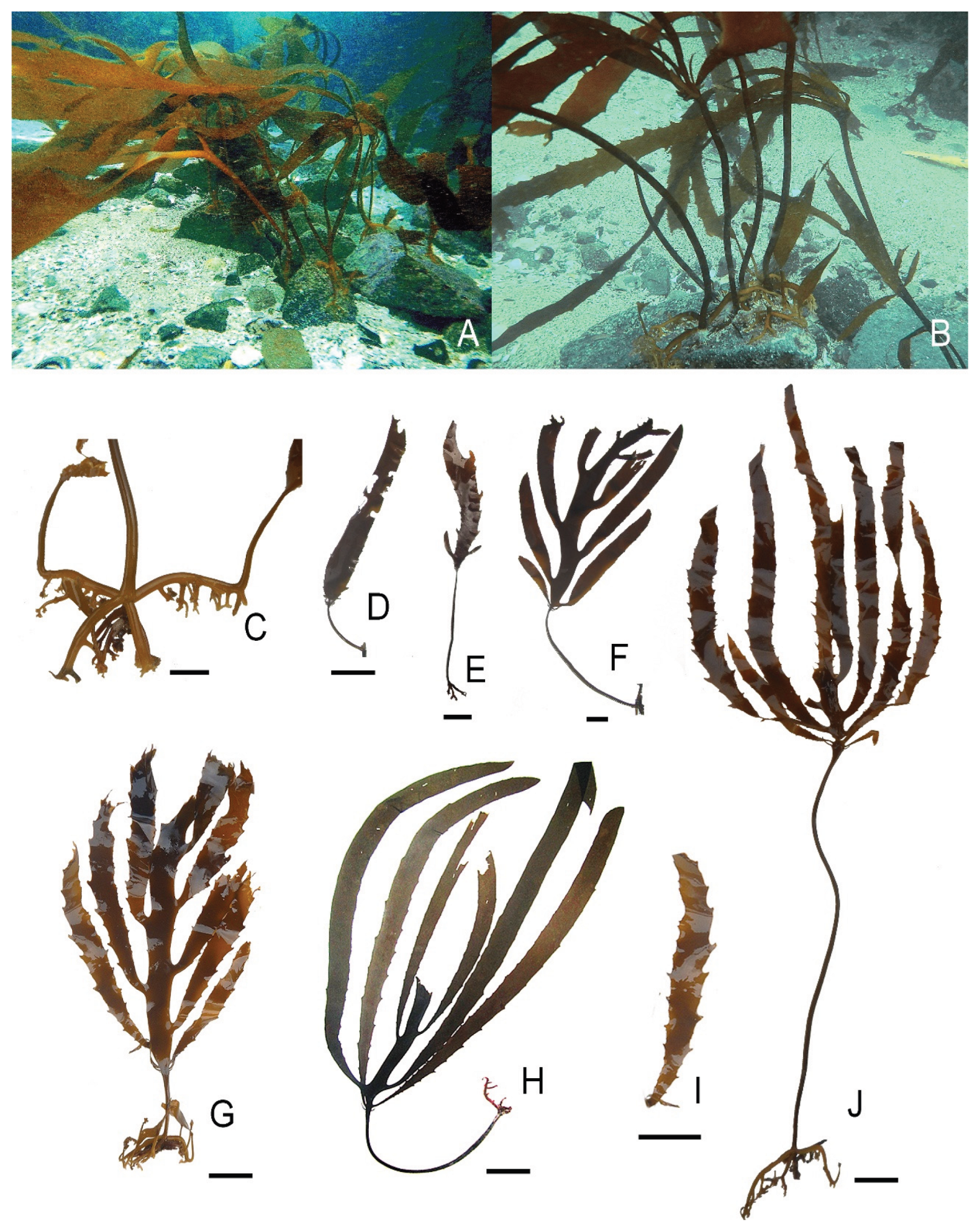

3.1.2. Eisenia gracilis

3.1.2. Eisenia from Desventuradas Islands

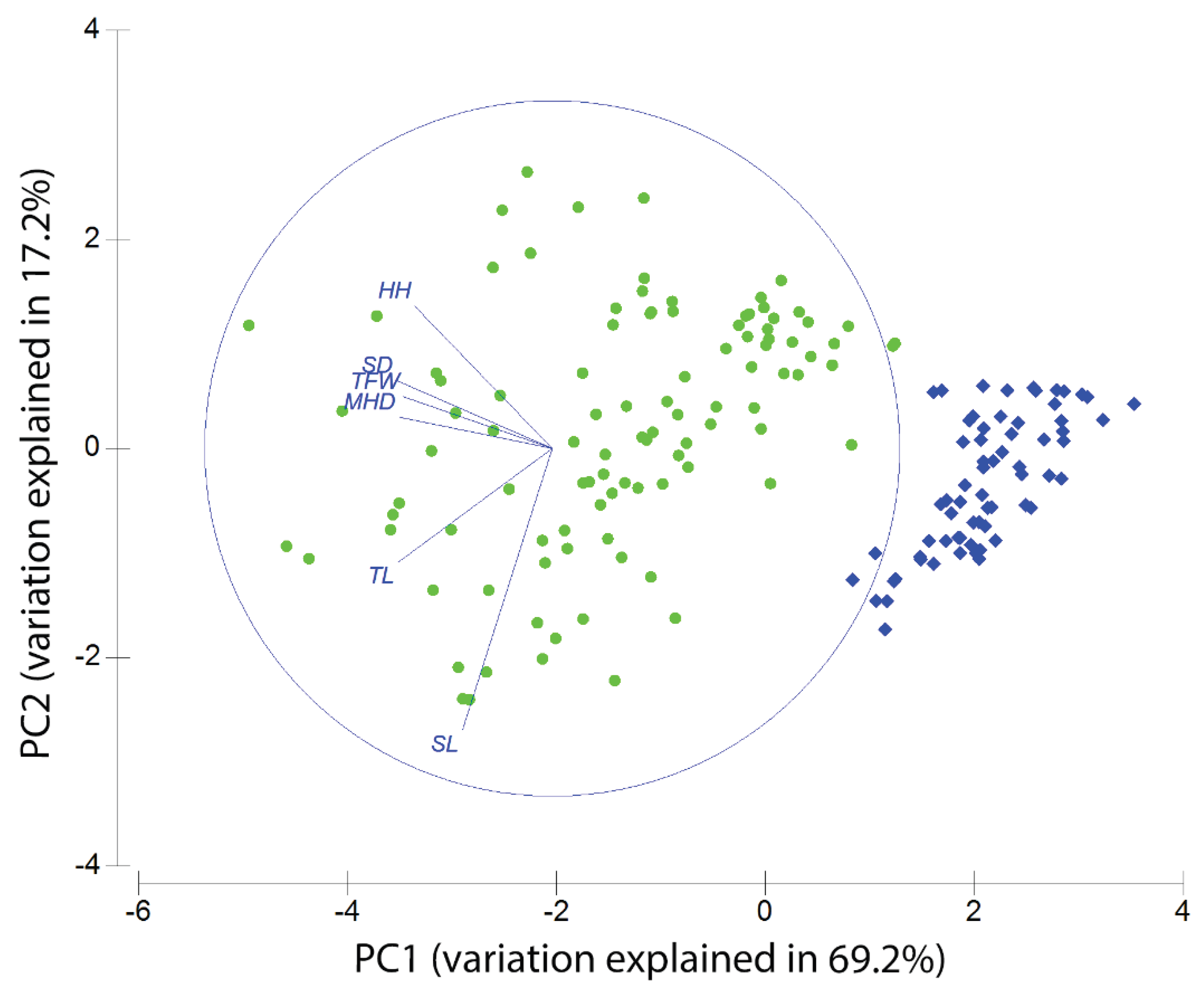

3.2. Morphometric Analysis

3.3. Delimitation of Species by GMYC Analyses

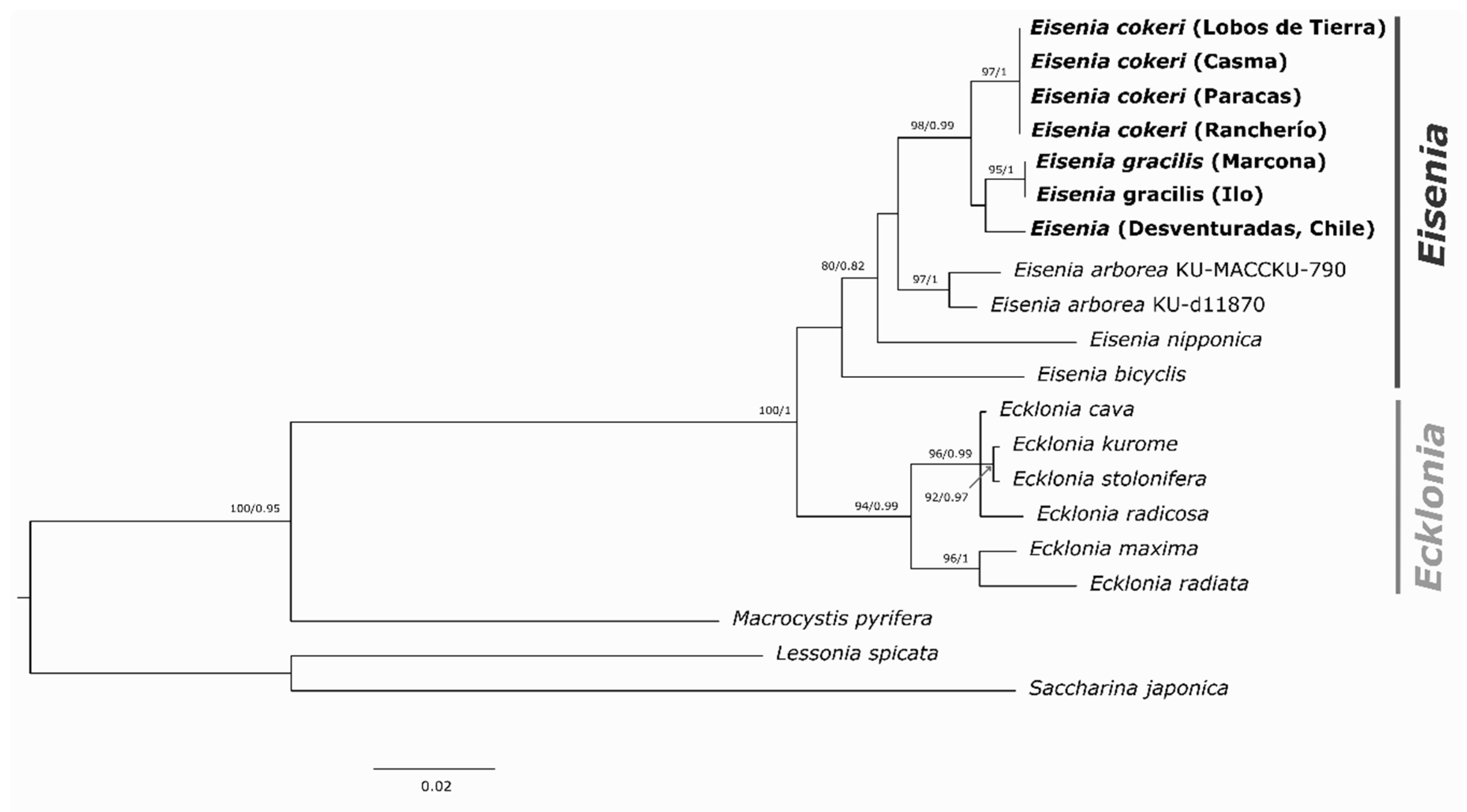

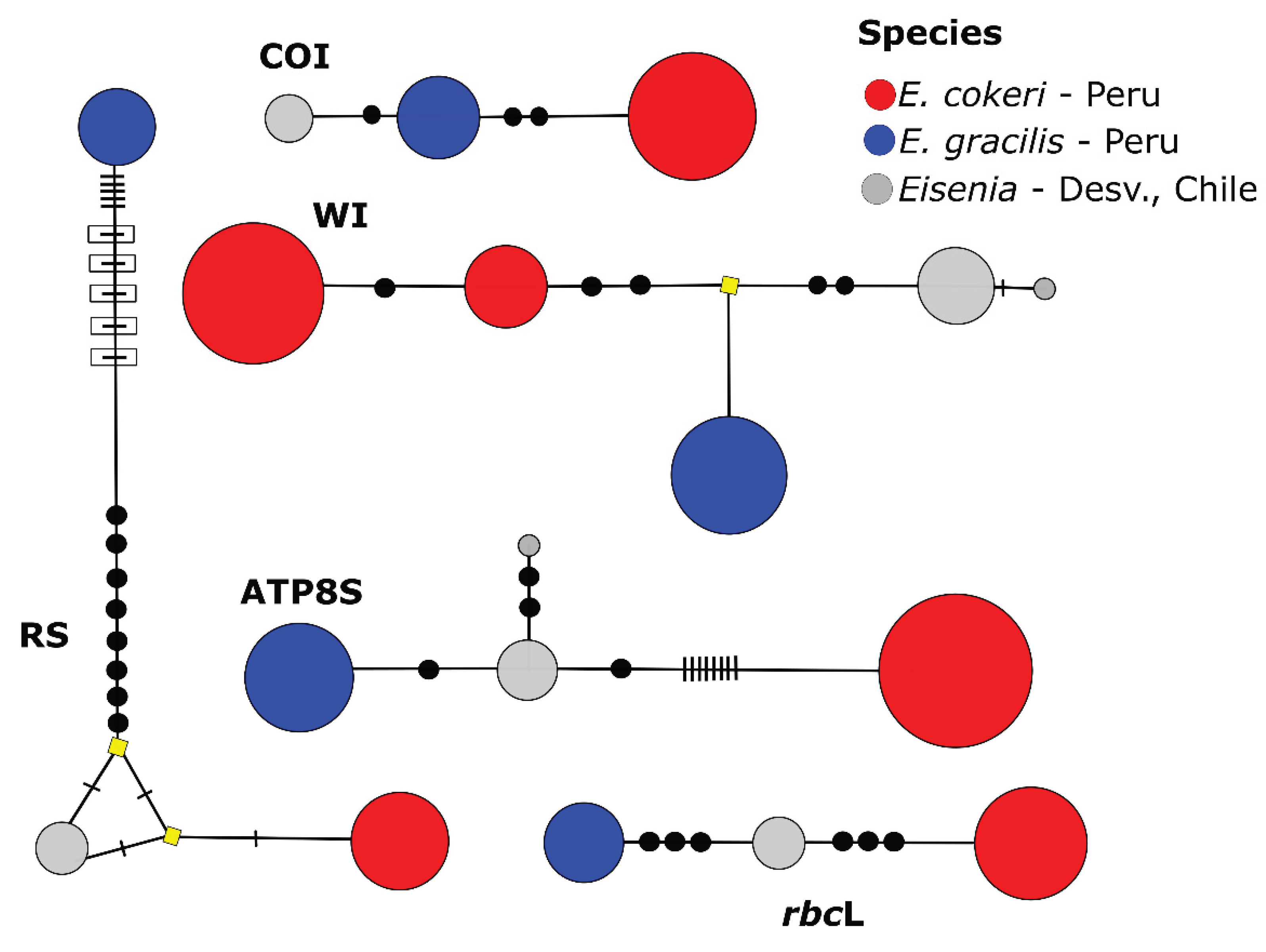

3.4. Phylogenetic Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Morphological Phylogenetic Position of Eisenia within Laminariales

4.2. Resolving the E. cokeri–E. arborea Ambiguity

4.3. How Many Species Are in the Southeast Pacific? Evidence from Molecular Delimitation

4.4. Morphological and Morphometric Distinctiveness

4.5. Spatial and Ecological Segregation

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krumhansl, K.A.; Okamoto, D.K.; Rassweiler, A.; Novak, M.; Bolton, J.J.; Cavanaugh, K.C.; Connell, S.D.; Johnson, C.R.; Konar, B.; Ling, S.D.; et al. Global Patterns of Kelp Forest Change over the Past Half-Century. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016, 113, 13785–13790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernberg, T.; Krumhansl, K.; Filbee-Dexter, K.; Pedersen, M.F. Chapter 3 - Status and Trends for the World’s Kelp Forests. In World Seas: an Environmental Evaluation (Second Edition); Sheppard, C., Ed.; Academic Press, 2019; pp. 57–78. ISBN 978-0-12-805052-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dayton, P.K. The Structure and Regulation of Some South American Kelp Communities. Ecological Monographs 1985, 55, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, C.E.; Mayes, C.; Druehl, L.D.; Saunders, G.W. A Multi-Gene Molecular Investigation of the Kelp (Laminariales, Phaeophyceae) Supports Substantial Taxonomic Re-Organization. Journal of Phycology 2006, 42, 493–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanza, V.; Buschmann, A.H. The Ecological Importance of Macrocystis Pyrifera (Phaeophyta) Forests towards a Sustainable Management and Exploitation of Chilean Coastal Benthic Co-Management Areas. International Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development 2013, 12, 341–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal, P.; Gamarra Salazar, A.; Moore, P.J.; Pérez-Matus, A. Different Kelp Species Support Unique Macroinvertebrate Assemblages, Suggesting the Potential Community-Wide Impacts of Kelp Harvesting along the Humboldt Current System. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems 2022, 32, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steneck, R.S.; Graham, M.H.; Bourque, B.J.; Corbett, D.; Erlandson, J.M.; Estes, J.A.; Tegner, M.J. Kelp Forest Ecosystems: Biodiversity, Stability, Resilience and Future. Environmental Conservation 2002, 29, 436–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bringloe, T.T.; Starko, S.; Wade, R.M.; Vieira, C.; Kawai, H.; De Clerck, O.; Cock, J.M.; Coelho, S.M.; Destombe, C.; Valero, M.; et al. Phylogeny and Evolution of the Brown Algae. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2020, 39, 281–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, G.W.; Druehl, L.D. Revision of the Kelp Family Alariaceae and the Taxonomic Affinities of Lessoniopsis Reinke (Laminariales, Phaeophyta). Hydrobiologia 1993, 260, 689–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.S.; Boo, S.M. Phylogeny of Alariaceae (Phaeophyta) with Special Reference to Undaria Based on Sequences of the RuBisCo Spacer Region. In Proceedings of the Sixteenth International Seaweed Symposium; Kain, J.M., Brown, M.T., Lahaye, M., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1999; pp. 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Boo, S.M.; Bhattacharya, D. Phylogeny of Alariaceae, Laminariaceae, and Lessoniaceae (Phaeophyceae) Based on Plastid-Encoded RuBisCo Spacer and Nuclear-Encoded ITS Sequence Comparisons. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2001, 21, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothman, M.D.; Mattio, L.; Wernberg, T.; Anderson, R.J.; Uwai, S.; Mohring, M.B.; Bolton, J.J. A Molecular Investigation of the Genus Ecklonia (Phaeophyceae, Laminariales) with Special Focus on the Southern Hemisphere. J Phycol 2015, 51, 236–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, H.; Akita, S.; Hashimoto, K.; Hanyuda, T. A Multigene Molecular Phylogeny of Eisenia Reveals Evidence for a New Species, Eisenia Nipponica (Laminariales), from Japan. European Journal of Phycology 2020, 55, 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, M.A. The Marine Algae of Peru. Memoirs of the Torrey Botanical Club 1914, 15, 1–185. [Google Scholar]

- Etcheverry, D.H. Algas Marinas de Las Islas Oceánicas Chilenas. Revista de Biología Marina. Revista de Biología Marina 1960, 10, 83–132. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, Y.E.; Acleto, C.; Foldvik, N. The Seaweeds of Peru; Beihefte zur Nova Hedwigia, 1964; Vol. 13, ISBN 978-3-7682-5413-7. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, P.C.; Chacana, M.E. Marine Algae from Islas San Félix y San Ambrosio (Chilean Oceanic Islands). Cryptogamie, Algologie 2005, 26, 103–118. [Google Scholar]

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. World-Wide Electronic Publication, National University of Ireland, Galway. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Buglass, S.; Kawai, H.; Hanyuda, T.; Harvey, E.; Donner, S.; De la Rosa, J.; Keith, I.; Bermúdez, J.R.; Altamirano, M. Novel Mesophotic Kelp Forests in the Galápagos Archipelago. Mar Biol 2022, 169, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uribe, R.A.; Smale, D.A.; Morales, R.; Aleman, S.; Atoche-Suclupe, D.; Burrows, M.T.; Earp, H.S.; Hinostroza, J.D.; King, N.G.; Perea, A.; et al. Spatiotemporal Variability in the Structure and Diversity of Understory Faunal Assemblages Associated with the Kelp Eisenia Cokeri (Laminariales) in Peru. Mar Biol 2024, 171, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acleto, C. Algas marinas del Perú de importancia económica. Serie de Divulgación, 1st ed.; Museo de Historia Natural - UNMSM: Lima, Peru, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Atoche-Suclupe, D.; Alemán, S.; Perea, Á.; Uribe, R. Variabilidad espacio temporal de la estructura poblacional, morfología y morfometría de Eisenia cokeri M.A. Howe, 1914 (Phaeophycea: Laminariales) en el nor-centro de Perú. Inf Inst Mar Perú 2021, 48, 414–429. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, M.H.; Kinlan, B.P.; Druehl, L.D.; Garske, L.E.; Banks, S. Deep-Water Kelp Refugia as Potential Hotspots of Tropical Marine Diversity and Productivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 16576–16580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuta, S.; Guillén, O. Oceanografía de las aguas costeras del Perú. Boletin Instituto del Mar del Perú 1970, 2, 157–324. [Google Scholar]

- Tarazona, J.; Arntz, W. The Peruvian Coastal Upwelling System. In Coastal Marine Ecosystems of Latin America; Seeliger, U., Kjerfve, B., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2001; pp. 229–244. ISBN 978-3-662-04482-7. [Google Scholar]

- Hollenberg, G.J. Culture Studies of Marine Algae. I. Eisenia Arborea. American Journal of Botany 1939, 26, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses, I.; Hoffmann, A.J. Contribution to the Marine Algal Flora of San Felix Island, Desventuradas Archipelago, Chile; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, K.R.; Gorley, R.N. Getting Started with PRIMER V7; PRIMER-E: Plymouth Marine Laboratory: Plymouth, United Kingdom, 2015; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Voisin, M.; Engel, C.R.; Viard, F. Differential Shuffling of Native Genetic Diversity across Introduced Regions in a Brown Alga: Aquaculture vs. Maritime Traffic Effects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2005, 102, 5432–5437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macaya, E.C.; Zuccarello, G.C. Genetic Structure of the Giant Kelp Macrocystis Pyrifera along the Southeastern Pacific. Marine Ecology Progress Series 2010, 420, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, C. Chromas; Version 1.41; School of Biomolecular and Biomedical Science; Griffith University: Brisbane, Queensland, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, T.A. BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic acids symposium series 1999, 41, 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Tellier, F.; Meynard, A.P.; Correa, J.A.; Faugeron, S.; Valero, M. Phylogeographic Analyses of the 30°S South-East Pacific Biogeographic Transition Zone Establish the Occurrence of a Sharp Genetic Discontinuity in the Kelp Lessonia Nigrescens: Vicariance or Parapatry? Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 2009, 53, 679–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Taboada, G.L.; Doallo, R.; Posada, D. jModelTest 2: More Models, New Heuristics and Parallel Computing. Nat Methods 2012, 9, 772–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Schmidt, H.A.; Von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. IQ-TREE: A Fast and Effective Stochastic Algorithm for Estimating Maximum-Likelihood Phylogenies. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2015, 32, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huelsenbeck, J.P.; Ronquist, F. MRBAYES: Bayesian Inference of Phylogenetic Trees. Bioinformatics 2001, 17, 754–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A Software for Comprehensive Analysis of DNA Polymorphism Data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandelt, H.J.; Forster, P.; Röhl, A. Median-Joining Networks for Inferring Intraspecific Phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 1999, 16, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crandall, K.A.; Templeton, A.R. Empirical Tests of Some Predictions from Coalescent Theory with Applications to Intraspecific Phylogeny Reconstruction. Genetics 1993, 134, 959–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, A.J.; Suchard, M.A.; Xie, D.; Rambaut, A. Bayesian Phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol 2012, 29, 1969–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, T.; Barraclough, T.G. Delimiting Species Using Single-Locus Data and the Generalized Mixed Yule Coalescent Approach: A Revised Method and Evaluation on Simulated Data Sets. Syst Biol 2013, 62, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2025.

- Friedlander, A.M.; Ballesteros, E.; Caselle, J.E.; Gaymer, C.F.; Palma, A.T.; Petit, I.; Varas, E.; Muñoz Wilson, A.; Sala, E. Marine Biodiversity in Juan Fernández and Desventuradas Islands, Chile: Global Endemism Hotspots. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0145059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mols-Mortensen, A.; Neefus, C.D.; Nielsen, R.; Gunnarsson, K.; Egilsdóttir, S.; Pedersen, P.Mø.; Brodie, J. New Insights into the Biodiversity and Generic Relationships of Foliose Bangiales (Rhodophyta) in Iceland and the Faroe Islands. European Journal of Phycology 2012, 47, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carstens, B.C.; Pelletier, T.A.; Reid, N.M.; Satler, J.D. How to Fail at Species Delimitation. Molecular Ecology 2013, 22, 4369–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, M.V.; Puillandre, N.; Castelin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Holford, M. A Good Compromise: Rapid and Robust Species Proxies for Inventorying Biodiversity Hotspots Using the Terebridae (Gastropoda: Conoidea). PLOS ONE 2014, 9, e102160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujisawa, T.; Barraclough, T.G. Delimiting Species Using Single-Locus Data and the Generalized Mixed Yule Coalescent Approach: A Revised Method and Evaluation on Simulated Data Sets. Syst Biol 2013, 62, 707–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshino, H.; Yamaji, F.; Ohsawa, T.A. Genetic Structure and Dispersal Patterns in Limnoria Nagatai (Limnoriidae, Isopoda) Dwelling in Non-Buoyant Kelps, Eisenia Bicyclis and E. Arborea, in Japan. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0198451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Provan, J.; Glendinning, K.; Kelly, R.; Maggs, C.A. Levels and Patterns of Population Genetic Diversity in the Red Seaweed Chondrus Crispus (Florideophyceae): A Direct Comparison of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms and Microsatellites. Biol J Linn Soc 2013, 108, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, C.; Faugeron, S.; Buschmann, A.H. Assessment of Genetic and Phenotypic Diversity of the Giant Kelp, Macrocystis Pyrifera, to Support Breeding Programs. Algal Research 2018, 30, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evankow, A.; Christie, H.; Hancke, K.; Brysting, A.K.; Junge, C.; Fredriksen, S.; Thaulow, J. Genetic Heterogeneity of Two Bioeconomically Important Kelp Species along the Norwegian Coast. Conserv Genet 2019, 20, 615–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pequeño, G.; Lamilla, J. The Littoral Fish Assemblage of the Desventuradas Islands (Chile) Has Zoogeographical Affinities with the Western Pacific. Global Ecology and Biogeography 2000, 9, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retamal, M.A.; Moyano, H.I. Zoogeography of Chilean Marine and Freshwater Decapod Crustaceans. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research 2010, 38, 302–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbruggen, H.; De Clerck, O.; Cocquyt, E.; Kooistra, W.H.C.F.; Coppejans, E. Morphometric Taxonomy of Siphonous Green Algae: A Methodological Study Within the Genus Halimeda (Bryopsidales). Journal of Phycology 2005, 41, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanolla, M.; Carmona, R.; De la Rosa, J.; Salvador, N.; Sherwood, A.R.; Andreakis, N.; Altamirano, M. Morphological Differentiation of Cryptic Lineages within the Invasive Genus Asparagopsis (Bonnemaisoniales, Rhodophyta). Phycologia 2014, 53, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K.E.; Moore, P.J.; King, N.G.; Smale, D.A. Examining the Influence of Regional-Scale Variability in Temperature and Light Availability on the Depth Distribution of Subtidal Kelp Forests. Limnology and Oceanography 2022, 67, 314–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witman, J.D. Subtidal Coexistence: Storms, Grazing, Mutualism, and the Zonation of Kelps and Mussels. Ecological Monographs 1987, 57, 167–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species (Area) |

Locality | Accession Number | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP8S | COI | WI | RS | rbcL | ||

| E. cokeri (Peru) | Lobos de Tierra Island, Lambayeque, coll. P. Carbajal & Iván Gómez, 06°25'30.4" S, 80°51'58.9" W |

OR361924 | OR361839 | OR362016 | OR362119 | OR361884 |

| OR361925 | OR361840 | OR362017 | OR362120 | OR361885 | ||

| OR361926 | OR361841 | OR362018 | OR362121 | OR361886 | ||

| OR361927 | OR361842 | OR362019 | OR362122 | OR361887 | ||

| OR361928 | OR361843 | OR362020 | OR362123 | OR361888 | ||

| OR361929 | OR361844 | OR362021 | OR362124 | OR361889 | ||

| OR361930 | OR362022 | |||||

| OR361931 | OR362023 | |||||

| OR361932 | OR362024 | |||||

| OR361933 | OR362025 | |||||

| OR361934 | OR362026 | |||||

| OR361935 | OR362027 | |||||

| OR361936 | OR362028 | |||||

| OR361937 | OR362029 | |||||

| OR361938 | OR362030 | |||||

| E. cokeri (Peru) | Casma, Ancash, coll. D. Hinostroza, 09°42'22.8" S, 78°17'49.8" W |

OR361939 | OR361845 | OR362031 | OR362125 | OR361890 |

| OR361940 | OR361846 | OR362032 | OR362126 | OR361891 | ||

| OR361941 | OR361847 | OR362033 | OR362127 | OR361892 | ||

| OR361942 | OR361848 | OR362034 | OR362128 | OR361893 | ||

| OR361943 | OR361849 | OR362035 | OR362129 | OR361894 | ||

| OR361944 | OR362036 | |||||

| OR361945 | OR362037 | |||||

| OR361946 | OR362038 | |||||

| OR361947 | OR362039 | |||||

| OR361948 | OR362040 | |||||

| OR361949 | OR362041 | |||||

| OR361950 | OR362042 | |||||

| OR361951 | OR362043 | |||||

| OR361952 | OR362044 | |||||

| OR361953 | ||||||

| E. cokeri (Peru) | El Ancla, Paracas, Ica, coll. P. Carbajal, 14°09'10.5" S, 76°14'52.9" W |

OR361954 | OR361850 | OR362045 | OR362130 | OR361895 |

| OR361955 | OR361851 | OR362046 | OR362131 | OR361896 | ||

| OR361956 | OR361852 | OR362047 | OR362132 | OR361897 | ||

| OR361957 | OR361853 | OR362048 | OR362133 | OR361898 | ||

| OR361958 | OR361854 | OR362049 | OR362134 | OR361899 | ||

| OR361959 | OR362050 | |||||

| OR361960 | OR362051 | |||||

| OR361961 | OR362052 | |||||

| OR361962 | OR362053 | |||||

| OR361963 | OR362054 | |||||

| OR361964 | OR362055 | |||||

| OR361965 | OR362056 | |||||

| OR361966 | OR362057 | |||||

| OR361967 | OR362058 | |||||

| OR361968 | OR362059 | |||||

| E. cokeri (Peru) | Rancherío, Laguna Grande, Ica, coll. P. Carbajal, 14°15'10.5" S, 76°25'52.9" W |

OR361969 | OR361855 | OR362060 | OR362135 | OR361900 |

| OR361970 | OR361856 | OR362061 | OR362136 | OR361901 | ||

| OR361971 | OR361857 | OR362062 | OR362137 | OR361902 | ||

| OR361972 | OR361858 | OR362063 | OR362138 | OR361903 | ||

| OR361973 | OR361859 | OR362064 | OR362139 | OR361904 | ||

| OR361974 | OR361860 | OR362065 | ||||

| OR361975 | OR361861 | OR362066 | ||||

| OR361862 | OR362067 | |||||

| OR361863 | OR362068 | |||||

| OR361864 | OR362069 | |||||

| OR362070 | ||||||

| OR362071 | ||||||

| OR362072 | ||||||

| OR362073 | ||||||

| OR362074 | ||||||

| Eisenia (Desventuradas Is.) | San Ambrosio Island, Desventuradas Island, coll. P. Manríquez Ángulo, 26°20'12.8" S, 79°53'31.4" W |

OR361976 | OR361865 | OR362075 | OR362140 | OR361905 |

| OR361977 | OR361866 | OR362076 | OR362141 | OR361906 | ||

| OR361978 | OR361867 | OR362077 | OR362142 | OR361907 | ||

| OR361979 | OR361868 | OR362078 | OR362143 | OR361908 | ||

| OR361980 | OR361869 | OR362079 | OR362144 | OR361909 | ||

| OR361981 | OR361870 | OR362080 | OR362145 | OR361910 | ||

| OR361982 | OR362081 | |||||

| OR361983 | OR362082 | |||||

| OR361984 | OR362083 | |||||

| OR361985 | OR362084 | |||||

| OR361986 | OR362085 | |||||

| OR361987 | OR362086 | |||||

| OR361988 | OR362087 | |||||

| OR361989 | OR362088 | |||||

| E. gracilis (Peru) | Tres Hermanas, Marcona, Ica, coll. P. Carbajal, 15°26'29.1" S, 75°04'32.5" W |

OR361990 | OR361871 | OR362089 | OR362146 | OR361911 |

| OR361991 | OR361872 | OR362090 | OR362147 | OR361912 | ||

| OR361992 | OR361873 | OR362091 | OR362148 | OR361913 | ||

| OR361993 | OR361874 | OR362092 | OR362149 | OR361914 | ||

| OR361994 | OR361875 | OR362093 | OR362150 | OR361915 | ||

| OR361995 | OR361876 | OR362094 | OR362151 | OR361916 | ||

| OR361996 | OR361877 | OR362095 | OR362152 | OR361917 | ||

| OR361997 | OR361878 | OR362096 | OR362153 | OR361918 | ||

| OR361998 | OR362097 | |||||

| OR361999 | OR362098 | |||||

| OR362000 | OR362099 | |||||

| OR362001 | OR362100 | |||||

| OR362101 | ||||||

| OR362102 | ||||||

| OR362103 | ||||||

| E. gracilis (Peru) | Leonas, Ilo, Moquegua, coll. P. Carbajal, 17°40'39.3" S, 71°22'15.9" W |

OR362002 | OR361879 | OR362104 | OR362154 | OR361919 |

| OR362003 | OR361880 | OR362105 | OR362155 | OR361920 | ||

| OR362004 | OR361881 | OR362106 | OR362156 | OR361921 | ||

| OR362005 | OR361882 | OR362107 | OR362157 | OR361922 | ||

| OR362006 | OR361883 | OR362108 | OR362158 | OR361923 | ||

| OR362007 | OR362109 | |||||

| OR362008 | OR362110 | |||||

| OR362009 | OR362111 | |||||

| OR362010 | OR362112 | |||||

| OR362011 | OR362113 | |||||

| OR362012 | OR362114 | |||||

| OR362013 | OR362115 | |||||

| OR362014 | OR362116 | |||||

| OR362015 | OR362117 | |||||

| OR362118 | ||||||

| Variable | E. cokeri | E. gracilis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum holdfast diameter (cm) |

Mean | 18,8 | 7,1 |

| DE | 4,0 | 2,8 | |

| Min | 11,0 | 2,0 | |

| Max | 33,5 | 13,0 | |

| Holdfast height (cm) | Mean | 7,4 | 2,7 |

| DE | 2,7 | 1,0 | |

| Min | 3,0 | 1,0 | |

| Max | 16,0 | 6,0 | |

| Stipe length (cm) | Mean | 32,5 | 24,8 |

| DE | 20,9 | 13,2 | |

| Min | 4,4 | 6,0 | |

| Max | 84,5 | 52,0 | |

| Stipe diameter (cm) | Mean | 1,4 | 0,5 |

| DE | 0,3 | 0,1 | |

| Min | 0,9 | 0,3 | |

| Max | 2,3 | 0,8 | |

| Total length (cm) | Mean | 132,4 | 70,4 |

| DE | 41,6 | 21,9 | |

| Min | 1,3 | 24,0 | |

| Max | 220,0 | 114,0 | |

| Total fresh weight (g) | Mean | 815 | 25 |

| DE | 536 | 16 | |

| Min | 80 | 5 | |

| Max | 2780 | 90 |

| Laminariales | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP8S | WI | COI | RS | rbcL | |

| Likelihood of null model | 538 | 815 | 569 | 1651 | 667 |

| Maximum likelihood of GMYC model | 543 | 815 | 597 | 1678 | 668 |

| Likelihood ratio | 11** | 0.14 n.s | 6*** | 574*** | 15*** |

| Number of ML clusters (95% CI) | 10 (8–12) | 13 (6–21) | 9 (8–10) | 12 (11–13) | 14 (12-16) |

| Number of Eisenia species in SEP | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Species/Area | Locality | Genomic compartment | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial | Chloroplast | ||||||

| ATP8S | COI | WI | RS | rbcL | |||

| E. cokeri (Peru) | Lobos de Tierra I. | 15 | 6 | 15 | 6 | 6 | |

| Casma | 15 | 5 | 14 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Paracas | 15 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Rancherío | 7 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Eisenia (Desventuradas Is.) | Desventuradas Is. | 14 | 6 | 14 | 6 | 6 | |

| E. gracilis (Peru) | Marcona | 12 | 8 | 15 | 8 | 8 | |

| Ilo | 14 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 5 | ||

| Total number of specimens | 85 | 34 | 88 | 35 | 35 | ||

| Marker | ATP8S | COI | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group |

E. cokeri (Peru) |

E. gracilis (Peru) |

E. cokeri + E. gracilis (Peru) |

Eisenia (Desv.) |

Total Eisenia |

E. cokeri (Peru) |

E. gracilis (Peru) |

E. cokeri + E. gracilis (Peru) |

Eisenia (Desv.) |

Total Eisenia |

|

| bp | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 162 | 602 | 602 | 602 | 602 | 602 | |

| N | 45 | 26 | 71 | 14 | 85 | 16 | 13 | 29 | 6 | 34 | |

| Nhap | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| Nhpriv | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | |

| S | 0 | 0 | 9 | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| Ssubst | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | |

| Sindels | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nindels | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| H | 0 | 0 | 0.471 | 0.143 | 0.610 | 0 | 0 | 0.512 | 0 | 0.629 | |

| H (SD) | 0 | 0 | 0.032 | 0.119 | 0.033 | 0 | 0 | 0.031 | 0 | 0.042 | |

| π | 0 | 0 | 0.006 | 0.176 | 0.006 | 0 | 0 | 0.002 | 0 | 0.003 | |

| π (SD) | 0 | 0 | 4E-04 | 0.001 | 4E-04 | 0 | 0 | 1E-04 | 0 | 3E-04 | |

| Π | 0 | 0 | 0.942 | 0.286 | 0.981 | 0 | 0 | 1.025 | 0 | 1.544 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).