Submitted:

26 November 2025

Posted:

04 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Geological Setting

3. Materials and Methods

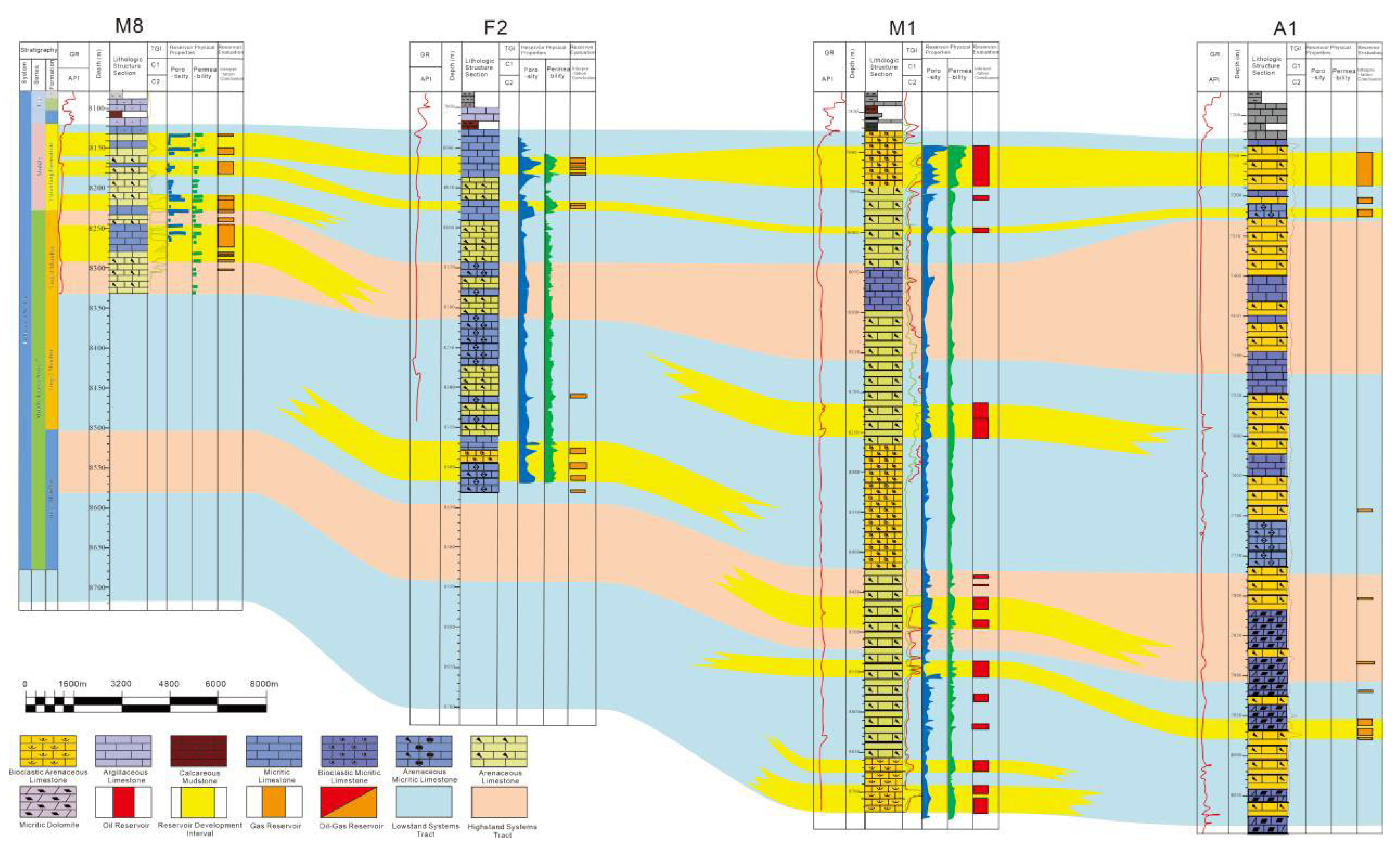

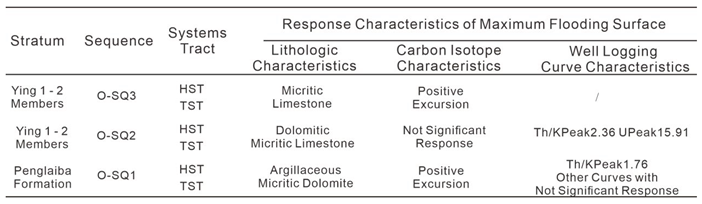

4. Division of Third-Order Sequence Stratigraphy

4.1. Characteristics of Third-Order Sequence Boundaries in Well A1 of the Fuman Area

4.2. Characteristics of Third-Order Sequence Boundaries in the Kalpin-Bachu Area

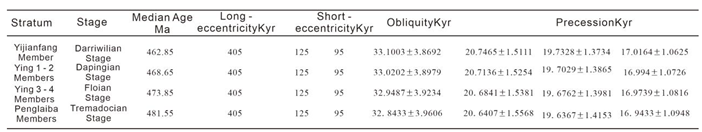

5. Fourth-Order Sequence Stratigraphic Division

5.1. Cyclostratigraphic Analysis

5.2. Sea-Level Simulation Based on the Sedimentary Noise Model

5.3. Characteristics of Fourth-Order Sequence Boundaries in Field Outcrops and Their Corresponding Relationship with the Fuman Area

6. Discussion

6.1. Sequence Division Scheme of the Fuman Area

6.2. Coupling Relationship Between Sequence Stratigraphic Division and Reservoir Development

7. Conclusions

References

- YANG Haijun, DENG Xingliang, ZHANG Yintao, et al. Great discovery and its significance of exploration for Ordovician ultra-deep fault-controlled carbonate reservoirs of Well Manshen 1 in Tarim Basin. China Petroleum Exploration, 2020, 25(3): 13-23. [CrossRef]

- WANG Qinghua, YANG Haijun, ZHANG Yintao, et al. Great discovery and its significance in the Ordovician of Well Fudong 1 in Fuman Oilfield, Tarim Basin. China Petroleum Exploration, 2023, 28(1): 47-58. [CrossRef]

- ABELS H A, AZIZ H A, KRIJGSMAN W, et al. Long-period eccentricity control on sedimentary sequences in the continental Madrid Basin (middle Miocene, Spain). Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2010, 289(1-2): 220-231. [CrossRef]

- BOULILA S, GALBRUN B, MILLER K G, et al. On the origin of Cenozoic and Mesozoic “third-order” eustatic sequences. Earth-Science Reviews, 2011, 109(3-4): 94-112. [CrossRef]

- MEI Mingxiang. From vertical stacking pattern of cycles to discerning and division of sequences: The third advance in sequence stratigraphy. Journal of Palaeogeography, 2011, 13(1): 37-54.

- SHI Juye, JIN Zhijun, LIU Quanyou, et al. Quantitative classification of high-frequency sequences in fine-grained lacustrine sedimentary rocks based on Milankovitch theory. Oil & Gas Geology, 2019, 40(6): 1205-1214. [CrossRef]

- LI Mingsong, HINNOV L A, HUANG C, et al. Sedimentary noise and sea levels linked to land–ocean water exchange and obliquity forcing. Nature Communications, 2018, 9: 1004. [CrossRef]

- JIA Chengzao. Structural features and oil-gas accumulation rules in Tarim Basin. Xinjiang Petroleum Geology, 1999, 20(3): 177-183. [CrossRef]

- SONG Xingguo, CHEN Shi, XIE Zhou, et al. Strike-slip faults and hydrocarbon accumulation in the eastern part of Fuman Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Oil & Gas Geology, 2023, 44(2): 335-349. [CrossRef]

- YANG Haijun, CAI Zhenzhong, LI Yong, et al. Organic geochemical characteristics of source rocks and significance for oil-gas exploration of the Tumuxiuke Formation in Fuman Area, Tarim Basin. Bulletin of Geological Science and Technology, 2023.

- YANG Haijun, HAN Jianfa, CHEN Lixin, et al. Characteristics and patterns of complex hydrocarbon accumulation in the Lower Paleozoic carbonate rocks of the Tazhong Palaeouplift. Oil & Gas Geology, 2007, 28(6): 784-790.

- FENG Zengzhao, BAO Zhidong, WU Maobing, et al. Lithofacies palaeogeography of the Ordovician in Tarim Area. Journal of Palaeogeography, 2007, 9(5): 447-460. [CrossRef]

- WU Guanghui, LI Qiming, XIAO Zhongyao, et al. Evolution characteristics and oil-gas exploration of palaeouplifts in Tarim Basin. Geotectonica et Metallogenia, 2009, 33(1): 124-130.

- ZHENG Herong, TIAN Jingchun, HU Zongquan, et al. Lithofacies palaeogeographic evolution and sedimentary model of the Ordovician in the Tarim Basin. Oil & Gas Geology, 2022, 43(4): 733-745. [CrossRef]

- TIAN Jun, YANG Haijun, ZHU Yongfeng, et al. Geological conditions for hydrocarbon accumulation and key technologies for exploration and development in Fuman Oilfield, Tarim Basin. Acta Petrolei Sinica, 2021, 42(8): 971-985. [CrossRef]

- WU Guanghui, DENG Wei, HUANG Shaoying, et al. Tectonic-paleogeographic evolution of Tarim Basin. Chinese Journal of Geology, 2023, 58(2): 305-321. [CrossRef]

- YANG Xiaofa, LIN Changsong, YANG Haijun, et al. Application of natural gamma ray spectrometry in sequence stratigraphic analysis of Late Ordovician carbonate rocks in the central Tarim Basin. Oil Geophysical Prospecting, 2010, 45(3): 384-39.

- DAI Dajing, TANG Zhengsong, CHEN Xintang, et al. Geochemical characteristics of uranium and its logging response in oil and gas exploration. Natural Gas Industry, 1995, 15(5): 21-24, 99-100. [CrossRef]

- ZHAO Zongju. Indicators of global sea-level change and research methods of marine tectonic sequences: A case study of the Ordovician in Tarim Basin. Acta Petrolei Sinica, 2015, 36(3): 262-273.

- LI Hongjiao, ZHANG Tingshan, ZHANG Xi, et al. Effects of sea-level change modulated by astronomical orbital cycles on organic reef development: A case study of the Late Permian Changxing Period in northeastern Sichuan. Fault-Block Oil & Gas Field, 2023, 30(1): 52-59.

- LU Tenghui, ZHANG Xi, ZHANG Tingshan, et al. Influence of the Luzhou Palaeouplift on the development of the Upper Triassic Xujiahe Formation in the southeastern Sichuan Basin, China. Journal of Stratigraphy, 2023, 47(2): 176-190.

- ZHANG Xi, ZHANG Tingshan, ZHAO Xiaoming, et al. Effects of astronomical orbital cycles and volcanic activity on organic carbon accumulation during the Late Ordovician-Early Silurian in the Upper Yangtze Area, South China. Petroleum Exploration and Development, 2021, 48(4): 732-744. [CrossRef]

- FANG Qiang, WU Huaichun, WANG Xunlian, et al. An astronomically forced cooling event during the Middle Ordovician. Global and Planetary Change, 2019, 173: 96-108. [CrossRef]

- WANG Meng, LI Mingsong, KEMP D B, et al. Sedimentary noise modeling of lake-level change in the Late Triassic Newark Basin of North America. Global and Planetary Change, 2022, 208: 103706. [CrossRef]

- ZHANG Tan, LI Yifan, FAN Tailiang, et al. Orbitally-paced climate change in the early Cambrian and its implications for the history of the Solar System. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2022, 583: 117420. [CrossRef]

- LI Mingsong, HINNOV L, KUMP L. Acycle: Time-series analysis software for paleoclimate research and education. Computers & Geosciences, 2019, 127: 12-22. [CrossRef]

- THOMSON D J. Spectrum estimation and harmonic analysis. Proceedings of the IEEE, 1982, 70(9): 1055-1096. [CrossRef]

- LI Mingsong, KUMP L R, HINNOV L A, et al. Tracking variable sedimentation rates and astronomical forcing in Phanerozoic paleoclimate proxy series with evolutionary correlation coefficients and hypothesis testing. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2018, 501: 165-179. [CrossRef]

- ERIKSSON P G, CATUNEANU O, NELSON D R, et al. Controls on Precambrian sea level change and sedimentary cyclicity. Sedimentary Geology, 2005, 176(1-2): 43-65. [CrossRef]

- DU Yang. Diagenesis in the Ordovician carbonate sequence stratigraphic framework of the Tarim Basin [D]. Beijing: China University of Geosciences (Beijing), 2018. [CrossRef]

- HUANG Chunju. The current status of cyclostratigraphy and astrochronology in the Mesozoic. Earth Science Frontiers, 2014, 21(2): 48-66.

- WALTHAM D. Milankovitch Period Uncertainties and Their Impact On Cyclostratigraphy. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 2015, 85(8): 990-998. [CrossRef]

- FAN Tailiang, YU Bingsong, GAO Zhiqian. Characteristics of carbonate sequence stratigraphy and its control on oil and gas in Tarim Basin. Geoscience, 2007, 21(1): 57-65.

- YU Bingsong, CHEN Jianqiang, LIN Changsong. Sequence stratigraphic framework and its control on the development of Ordovician carbonate reservoirs in Tarim Basin. Oil & Gas Geology, 2005, 26(3): 305-309, 316.

- SHI Pingzhou, LI Ting, ZHU Yongfeng, et al. Geochemical characteristics and environmental implications of fracture-cave fillings: A case study of the Middle Ordovician Yijianfang Formation in Fuman Area, Tarim Basin. Science Technology and Engineering, 2023, 23(11): 4527-4535. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).