1. Introduction

The study of multi-quark states has always been one of the best approaches to understanding low-energy quantum chromodynamics (QCD), as multi-quark states can provide more information compared to traditional hadronic structures (mesons and baryons ), especially regarding the color structure within multi-quark configurations. Among these multi-quark structures, the study of tetraquark states has been one of the most important topics in hadron physics. To date, the most frequently observed exotic hadrons experimentally are those with a tetraquark structure, particularly tetraquark states containing charm quarks. Various interpretations of the charm-containing tetraquark states have been discussed, and many other possible charm-containing tetraquark states have also been proposed in the literature.

It is noteworthy that, since the reporting of the

[

1] in 2003, many experimental groups have successively reported a large number of exotic hadrons with tetraquark structures. However, these tetraquark states are actually correlated in some way. For instance, the

, with quantum numbers

and quark composition

, was initially reported. Subsequently, the

[

2], with the same quark composition as the

but with quantum numbers

, and the

[

3], which shares the same quantum numbers

as the

but has a different quark composition (

), were reported. Recently, the LHCb collaboration reported a new state, the

, with quantum numbers

and a quark composition of

. While considerable theoretical work has been done on this state, its companion states,

and

, have largely been overlooked in the research.

Currently, theoretical studies on the

tetraquark system are relatively scarce, with most of the research focusing on the

state, as detailed in the literature [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. For example, in Ref. [

4], the authors, based on heavy-quark symmetry and evaluating finite-mass corrections, predicted that the mass of the

should be 179 MeV above threshold. However, this result contradicts the findings in Ref. [

5], where the authors systematically studied

(

and

) tetraquark states with the color-magnetic interaction, taking into account color mixing effects. They found a bound state for the

with a binding energy of 84 MeV. In Ref. [

6], the authors presented the results of a lattice calculation of

states, performed on three dynamical

highly improved staggered quark ensembles at lattice spacings of approximately 0.12, 0.09, and 0.06 fm. They ultimately obtained a shallow bound state for the

. In Ref. [

7], the authors argued that the D-wave component contributes to the formation of a bound state for

. After the observation of the

, the authors in Ref. [

8] utilized the experimental information on the binding energy of

to predict a bound state for the

.

In this study, we apply the constituent quark model, which incorporates SU(3) symmetry, to systematically explore the

system with quantum numbers

and

. To better describe the dynamics between quarks, we employ the high-precision few-body system calculation method, the Gaussian Expansion Method (GEM). In our analysis, we consider two distinct spatial configurations: meson-meson and diquark-antidiquark, along with all possible color and spin configurations. In principle, a single spatial configuration, along with all possible spatial excitations (S-, P-, D-... waves), is sufficient to describe the wave function of the

system. However, considering all possible spatial excitations is computationally challenging. A more efficient approach is to consider the meson-meson and diquark-antidiquark mixing effects, which simplifies the calculations. However, this approach introduces many spurious energy levels. To eliminate these unstable energy levels and accurately identify stable structures (resonant and bound states), we employ the Real-Scaling Method (RSM) [

13]in our work.

The structure of this paper is as follows. After the introduction, Sec. II provides a brief description of the quark model, the construction of wave functions, and an overview of the RSM. Our numerical results and related discussions are presented in Sec. III. Finally, a summary is given in Sec. IV.

2. Model Setup

Among the various phenomenological models used to study particle properties, the quark model has always been one of the most successful models, as it has successfully explained and predicted a large number of experimental data. In the quark model[

9,

10,

11,

12], its Hamiltonian includes (Eq.

1) the mass term

, the kinetic term

, and the potential term

. Since we adopt the chiral quark model, the potential term can be further divided into the confinement potential

, the one-gluon exchange potential

, and the meson exchange potentials

and

, as shown in (Eq.

2). These terms correspond to the three fundamental properties of QCD: quark confinement, asymptotic freedom, and chiral symmetry breaking.

Since this paper focuses on the

and

systems, for the

case, the system is in an S-wave, and thus the Hamiltonian only needs to consider central forces. In contrast, for the

case, the system includes P-waves, so the Hamiltonian also includes spin-orbit coupling interactions. Therefore, our confinement potential includes both the central force term

and the spin-orbit coupling term

. Similarly, the one-gluon exchange potential includes

and

, and the meson exchange potential is divided into

,

, and

. Here,

represents pseudoscalar meson exchange, while

and

correspond to scalar meson exchange. This distinction arises because in the

system,

and

form an SU(3) symmetric pair, and in order to more accurately study the interaction between

and

, we introduce scalar meson exchange.

represents the SU(2) Pauli matrices;

represents the SU(3) color and flavor Gell-Mann matrices, respectively;

denotes the strong coupling constant of one-gluon exchange.

represents the masses of the Goldstone bosons,

denotes the corresponding cut-offs, and

is the Goldstone-quark coupling constant. The quark tensor operator is given by

Finally,

is the standard Yukawa function, defined as

while

and

are related functions, given by

respectively. After fitting the

-family mesons ( as shown in

Table 1 ), all the model parameters are determined, which are collected into

Table 2.

Now, we turn to the construction of the wave function for the tetraquark structures. The wave function of the system consists of four parts: orbital, spin, flavor, and color. The wave function for each part is constructed in two steps. First, we construct the wave functions for the two

clusters separately, and then we couple the two cluster wave functions to form the complete four-body wave function. The first part is the orbital wave function. For the spatial wave function of the

system, we consider two possible configurations: the diquark structure and the molecular structure. The primary distinction between their spatial wave functions lies in the arrangement of the constituent quarks. In the molecular structure, the four-quark spatial wave function is encoded as

-

, while in the diquark structure, it is encoded as

-

. In this study, for the

structure, both the first and second clusters in the spatial part are in S-wave, while in the

structure, the second cluster is in P-wave. We then couple this spatial wave function with the relative motion wave function to determine the total orbital wave function. The expressions for the total wave functions are:

The wave function for relative motion,

, is constructed using the Gaussian expansion method (GEM). Its functional form is a linear combination of Gaussian basis functions,

Herein,

represents the normalization factor, calculated as

The coefficients

are the variational parameters determined by the system. The Gaussian exponents

are selected to cover a range of scales geometrically, following the relation,

In this study,

,

, and

represent the relative motion wave functions of the first cluster, the second cluster, and the relative motion between the two clusters, respectively. Since we adopt the Real-Scaling Method (RSM)[

13], this approach allows us to simultaneously obtain both bound states and resonant states. Specifically, it involves systematically scaling the width of Gaussian functions between the two groups using a scaling factor, denoted by

. This is achieved by multiplying all range parameters by

, resulting in a transformation of

. As

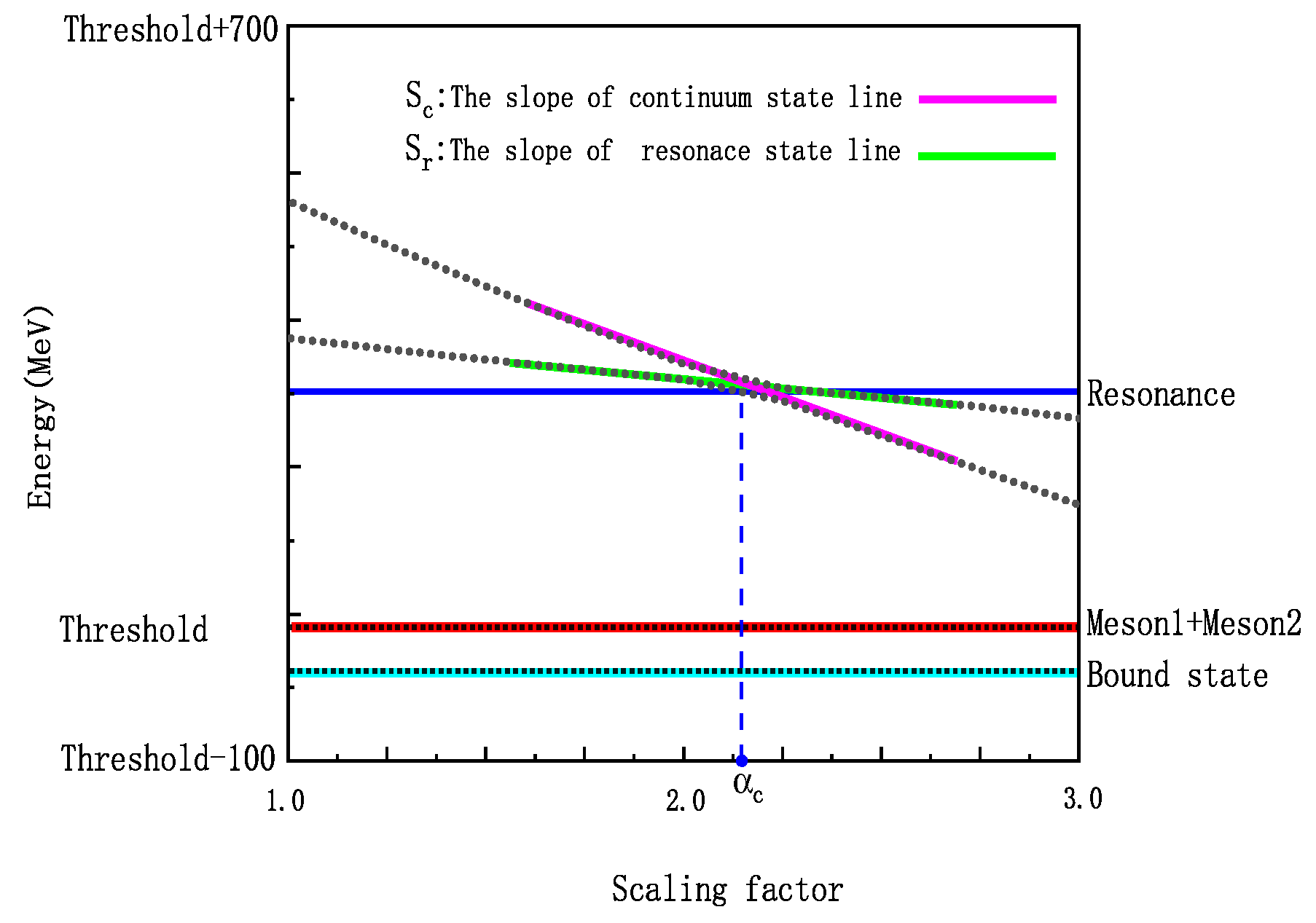

increases, the width of the Gaussian functions expands, leading to variations in the system’s intrinsic energy. If a stable structure is present, it remains unaffected by changes in the Gaussian function widths. As shown in

Figure 1, when the line representing the resonance state intersects with the line representing the continuum, strong coupling occurs between these two states, and the lines form a non-crossing structure. This structure corresponds to a resonant state in our calculations, and its decay width can be computed using the formula

Since the bound state corresponds to the lowest energy of the system, with no associated decay threshold, it is represented as a horizontal line in our calculations.

Next, we need to construct the flavor wave function. Since we consider two possible structures for the

system: the molecular state structure

-

and the diquark structure

-

, and since isospin quantum number

I is a good quantum number, we fix its third component,

, to be

. Consequently, for the flavor wave functions, we have two forms:

For the spins of the quark and antiquark, they are indistinguishable, regardless of whether the system is in a diquark or molecular structure. Therefore, the spin wave functions for the sub-clusters are given below

where

and

represent the third component of quark spin, taking values of

and

, respectively. By coupling the spin wave functions of the two sub-clusters with Clebsch-Gordan coefficients, the total spin wave function can be written as

In the

system studied in this paper, its color structure is crucial, as mentioned in Ref. [

5]. QCD requires that multi-quark states must be color-neutral. Therefore, for their molecular state structures, there are two possible configurations:

and

. For the diquark-antidiquark structure, the two possible configurations are

and

.

The total wave function of the

system is the internal product of color, spin, flavor, and spatial wave functions. The total wave function

can be expanded as follows:

where

is the antisymmetrization operator. In the

system,

. Finally, by applying the Rayleigh-Ritz variational principle to the Schrodinger equation, we obtain the eigenvalues and eigenfunctions:

4. Summary

In the framework of the chiral quark model, we performed bound-state and resonance-state calculations for the system.

Based on our bound-state calculation results, in the system, although no individual channel is a bound state, after complete channel coupling, we obtained a deep bound state with a binding energy of 3965 MeV, which is consistent with most theoretical studies. In the system, we did not obtain a bound state.

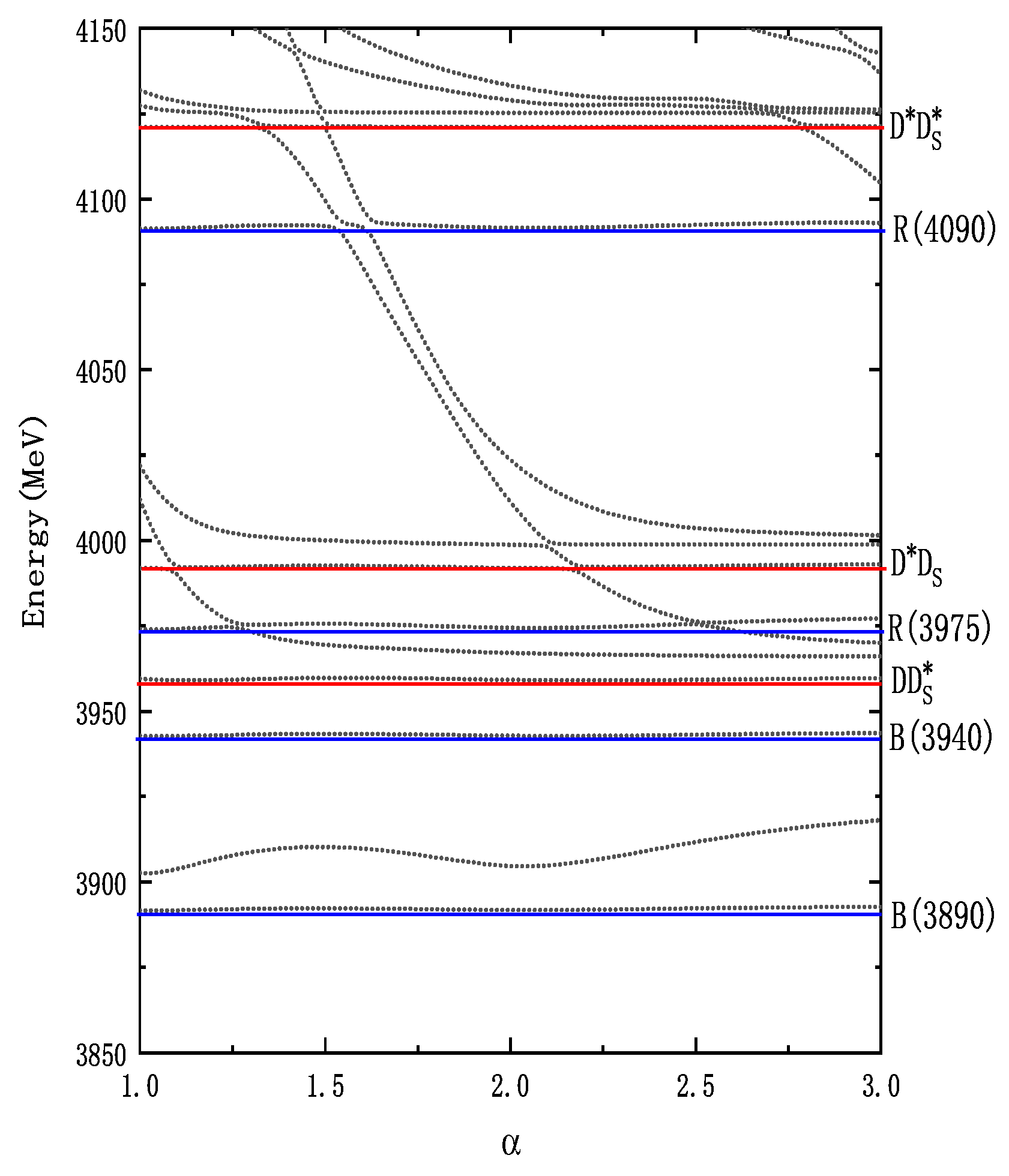

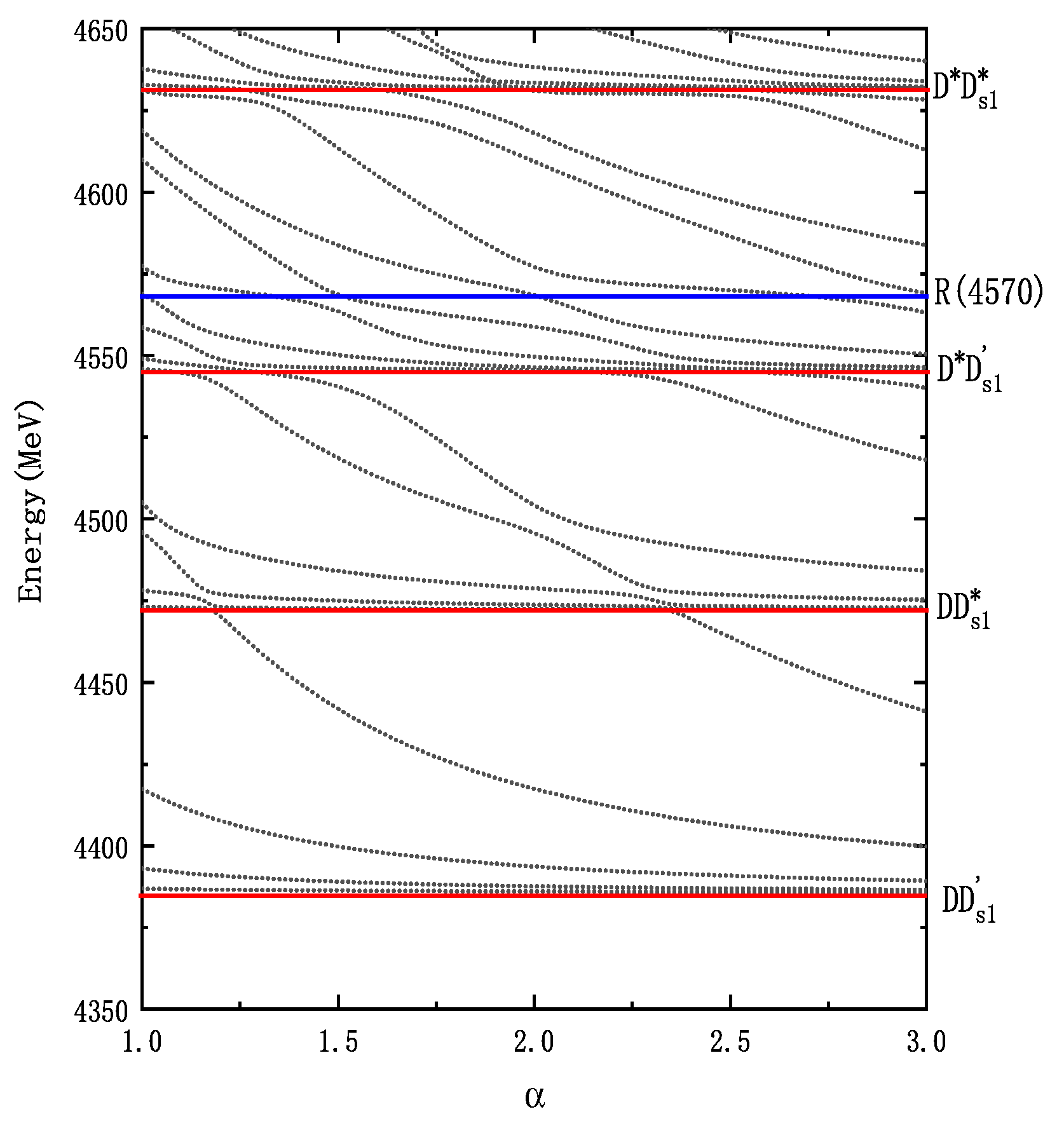

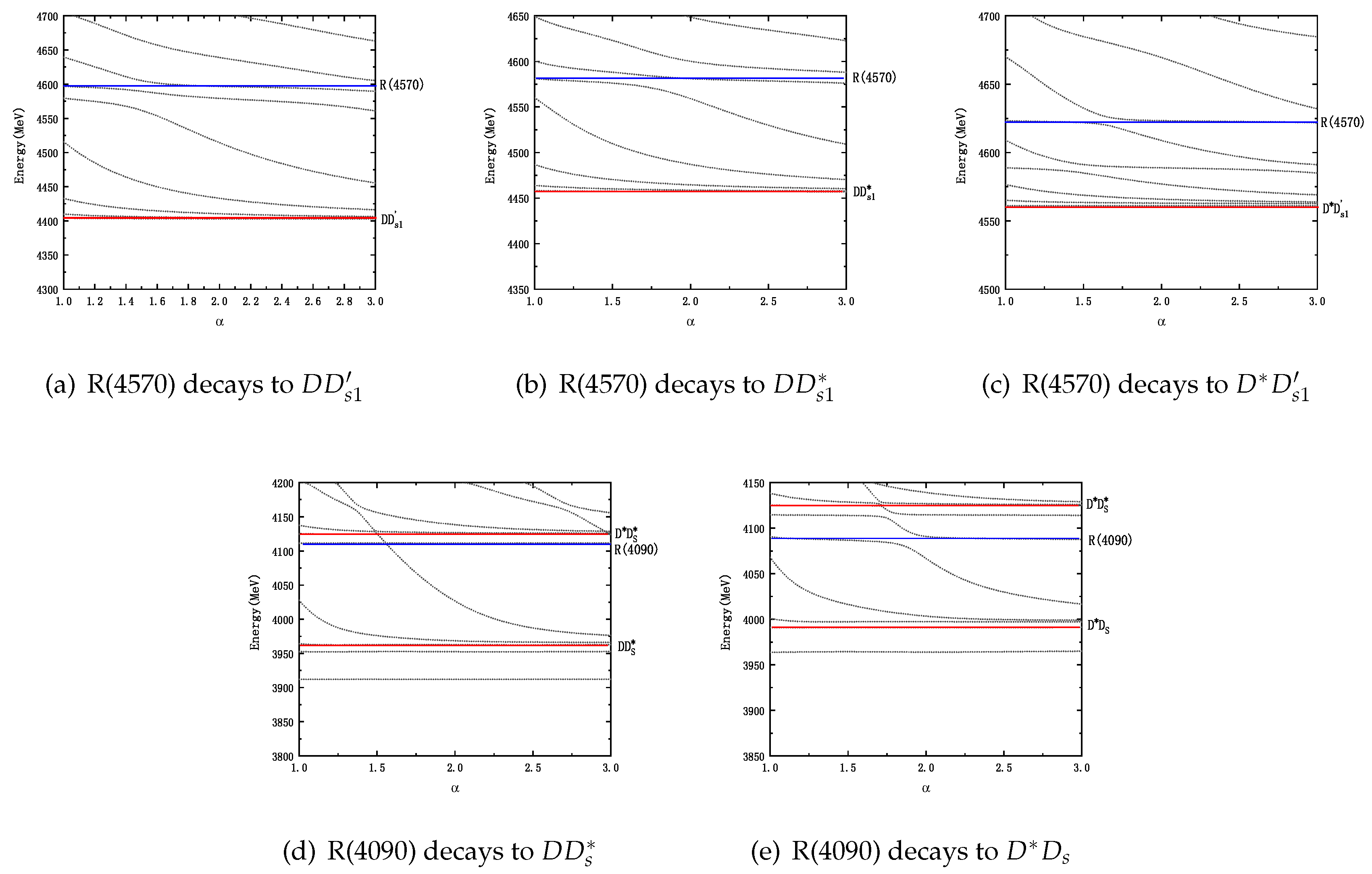

The resonance-state calculations yielded significant results. In the system, we found two bound states, B(3890) and B(3940), with the primary components being and , respectively, as well as two resonance states, R(3975) and R(4090), with the primary components being and , respectively. Notably, R(4090) contains a significant diquark component. Therefore, B(3890), B(3940), and R(3975) exhibit a clear molecular structure with root-mean-square distances of 1-2 fm. The system contains only one resonance state, R(4575), which is primarily composed of a diquark structure, and thus its quark distance is within 1 fm.

In conclusion, we identified five stable structures in the system: two bound states, B(3890) and B(3940), and three resonance states, R(3975), R(4090), and R(4575). Their main decay channels are , , and , , respectively. We strongly suggest that experimental groups search for these structures, especially in the system.